1. Introduction

Climate change global issues lead governments and researchers to develop new technologies to reduce the carbon fingerprint, reduce the use of fossil fuels and turn the global economy from linear to circular and sustainable [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In the food industry and food technology sector, these trends promote the development of new technologies/processes to reduce food waste and utilize food by-products [

1,

5,

10,

11,

12]. Thus, food technology in the era of bioeconomy and sustainability try to reduce food waste, recovers biopolymers and bioactive compounds from food and agricultural by products and reuse them in the development of biobased packaging, biobased food additives and the development of functional foods [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Valorization of industrial by-products is a key factor for building a circular economy and creating a sustainable production [

13,

14]. Recently, attention has been given to the generation of large quantities of spent grain from brewing and distilling processes. Researchers have given emphasis in the development of different valorization processes for added value use of brewer’s spent grain (BSG) beyond its traditional use in animal feed (70%), for biogas production (10%), and disposition in landfills (20%) [

13,

14]. BSG is a brewing industry by-product that makes up 85 percent of brewing waste [

15]. The annual production of wet BSG stands at approximately 8 million tons in Europe and 40 million tons worldwide [

13,

14]. BSG is a lignocellulosic biomass rich in proteins, lipids, minerals, and vitamins. The wet BSG contains up to 80% moisture while in the dried BSG moisture has decreased to 5–8%. Dried BSG also contains 14–30% crude protein, 3–10% lipids, 0.4–2.17% starch, and 50–70% total fiber which is nutrient added value. Fiber, a crucial nutrient with significant health benefits, contains ~ 16% cellulose, ~ 28% hemicellulose, ~7% lignin and various monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides as well as micronutrients such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and polyphenols [

15]. Thus, BSG as a large volume and nutrient dense by-product has great potential to be used in the context of sustainable food transition [

15,

16].

Although BSG has been already used for animal feed, biogas production, and disposition in landfills its use in development of biodegradable food packaging it is limited. BSG has great potential as a raw material for the development of sustainable packaging because of the ability of its proteins to interact with the polypeptide chains and because cellulose, which has been utilized in food packaging, is one of the major components of BSG. BSG exhibited enhanced antioxidant potential, which make it a byproduct for the development of antioxidant active packaging materials [

17,

18,

19,

20]. To use BSG in the development of a packaging materials, plasticizers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or glycerol are added [

15] to reduce its brittleness and increase its ductility. BSG has been used in the development into a six-pack beer carrier paperboard alternative [

15]. BSG also has been added in polyurethane to enhance its thermal stability and has been blended with chitosan to enhance its antibacterial activity [

12,

21]. Nanocomposite films with UV-barrier, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties and enhanced thermal and mechanical properties based on nanocellulose (NFC) and BSG arabinoxylans were prepared [

22]. BSG protein based active films have been developed by using PEG or glycerol as plasticizers [

23]. The water-barrier properties, the solubility, the optical properties, the antioxidant (reducing power, ABTS

•+ and lipidic radical scavenging) properties, and the antimicrobial properties of obtained films were studied [

23]. Recently, BSG based composite films have been developed by employing poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) and glycerol as binder materials, along with hexa-methoxy-methyl-melamine (HMMM) as a water-repelling agent [

24]. The study results that films with a practical BSG content varying from 20 to 40 %wt. exhibited a balance between moisture absorption and mechanical strength [

24]. The addition of glycerol enhanced ductility and toughness of the films, while the addition of HMMM enhanced their water resistance [

24].

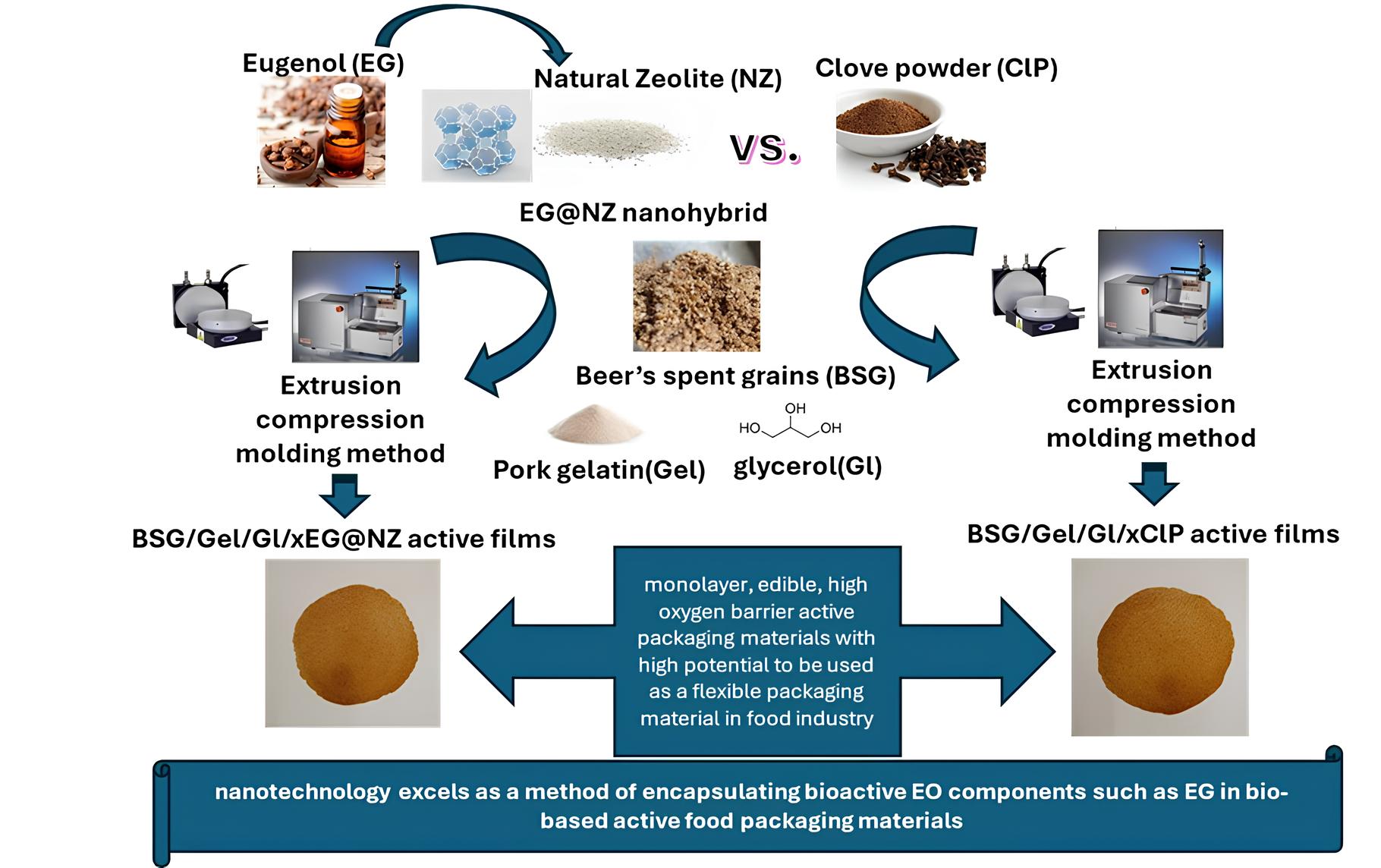

In this paper a nanohybrid made by natural zeolite (NZ) modified with eugenol (EG) essential oil (EO) and pure clove powder (ClP) are used as both reinforcement and active agents for a BSG/gelatin (Gel)/Glycerol (Gl) composite film. It is well known that EO derivatives such as EG are bio-based antioxidant/antibacterial compounds which could potentially replace chemical additives used as antioxidant/antibacterial agent in food preservation [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. It is also known that adsorption of such EOs on natural nanocarriers such as nanoclays, natural zeolites, silicates and activated carbons ensures the slow loss of their activity, and give rise to their control release in the food [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. EG which can be extracted from clove powder has been previously widely used in active food packaging and meat preservation [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Clove powder (ClP)which contains physically encapsulated EG it is well known for its antioxidant/antibacterial activity and has also been previously studied in meat preservation [

40,

41].

Specific innovative points of current study are: (i) the preparation via an extrusion molding compression method and the tensile properties, oxygen barrier properties, antioxidant activities, antibacterial activities and toxicity/genotoxicity characterization of such BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ (where x=5,10 and 15 %wt.) and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP (where x=5,10 and 15 %wt.) active films is for first time reported, and (ii) to the best of our knowledge a comparison study between EG@NZ nanohybrid and clove powder as both reinforcement and antioxidant/antibacterial agents in BSG/Gel/Gl based active packaging films is for first time reported too.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Gelatin type A used (CAS 9000-70-8) was purchased from Thermo Scientific Chemicals (Thermo Fisher Scientific. 168 Third Avenue. Waltham, MA USA 02451). Eugenol, 2-Methoxy-4-(2-propenyl) phenol, 4-Allyl-2-methoxyphenol, 4-Allylguaiacol (CAS 97-53-0), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (CAS 1898-66-4, caffeic acid (CAS 331-39-5), 2-Thiobarbituric acid reagent for sorbic acid (CAS 504-17-6), Absolute ethanol (C

2H

6O) (CAS 64-17-5), sodium carbonate (Na

2CO

3) (CAS 497-19-8), and Folin Ciocalteü (47641) were purchased from Sigma-Aüldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Ethanol ROTIPURAN® ≥99,8 %, p.a. (CAS 64-17-5) was purchased from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). Gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydrobenzoic acid) 99% isolated from Rhus chinensis Mill. (JNK Tech. Co., Republic of Korea). All the other reagents and solvents used were of analytical grade. Natural Zeolite powder 100 gr with Product Code: 102.057.004 was purchased from Health Trade (Patras, Greece). Dried brewer's spent grain was gifted from KYKAO handcrafted brew (Platani 26504, Patra, Greece

https://kykao.gr/). Clove powder was purchased for the local Super Market.

2.2. Preparation of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

For the preparation of EG@NZ nanohybrid used in development of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films the recently reported vacuum-assisted adsorption process was followed [

38]. For the preparation of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films as well as BSG/Gel/Gl film via with the extrusion method, a twin-screw mini lab extruder (Haake Mini Lab II, Thermo Scientific, ANTISEL, S.A., Athens, Greece) was operated. For all prepared films twin-extruder conditions were: 110

oC, 250 rounds per minute (rpm) and 5 min operation time. The amounts of BSG, Gel, Gl, H

2O, EG@NZ nanohybrid, and ClP used as well as twin extruder operating condition with sample code names are listed in

Table 1. The collected after the extrusion process pellets were transformed into films via the compression molding method. Films with an average diameter of 10 cm and an average thickness of 0.2 mm were obtained by heat pressing the pellets at 110 °C with 1 tone (tn) pressure for 2 min by using a thermostatιψ hydraulic press (Specac Atlas™ Series Heated Platens, Specac, Orpinghton, UK).

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

All obtained BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films were characterized with X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) measurements by using the instrumentation and following the methodology and experimental settings given in detail in supplementary material file.

2.4. Charactrization of Packaging Properties of BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

Tensile and oxygen barrier properties of all obtained films were determined according to ASTM D638 and ASTM D 3985 methods correspondigly by using the instumentation and following the methodology and experimental settings described in supplamentary material. Total phenic content (TPC), and in Vitro Antioxidant Activity according to 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, of all obtained films were determned according to the methodology described in detail in supplamentary material file.

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity of BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP Active Films

Standard and isolated strains of the following two bacteria, including one Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC25923)) and one Gram-negative (Escherichia coli (RM03) bacteria were used in screening the antimicrobial activity. The antimicrobial activity of the food film samples was determined using the disk diffusion method according to EUCAST guidelines. Bacteria from Frozen glycerol stock cultures were grown aerobically at 37 °C in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (CLSI, 2018). Before each experimental procedure, cultures were transferred to liquid medium and incubated for 24 h. Broth cultures were then adjusted to a specific optical density (OD) at 600 nm (OD600) using a pre-established calibration curve unique to each microorganism to achieve a cell density of 108 colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL). OD measurements were performed using a Q5000 micro-volume UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Quawell Technology CA, USA).

2.5.1. Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test

Aseptically, 100 mg sample of each food film sample was weighed and directly applied as a defined circular deposit onto the surface of Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates which had been previously inoculated with the respective test microorganism (108 CFU ml-1). The inoculated MHA plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. After the incubation, the diameter of the zone of inhibition was calculated using a calibrated ruler. The test was performed in triplicate for each test microorganism and each food film concentration.

2.6. Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Effects of Films in Human Lymphocytes

2.6.1. Ethics Statement and Approval

The experimental use of human lymphocytes was conducted in accordance with international bioethical criteria, following approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Patras (Ref. No 11584/March 06, 2018).

2.6.2. Whole Blood Collection and Cell Culture Preparation

Whole blood samples were collected in heparinized vectors from 2 healthy and non-smoking male donors (20 and 25 years old), previously declared that they were not exposed to radiation, drug treatment or any viral infection in the recent past.

2.6.3. CBMN Assay

The cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of films (at concentrations ranged from 50 to 500 μg mL

− 1) in human lymphocytes was assessed using the Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus (CBMN) assay with cytochalasin-B [

42].

For each of the two donors, a 0.5 mL whole blood aliquot was introduced into 6.5 mL of Ham’s F-10 medium, supplemented with 1.5 mL fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.3 mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA) to stimulate lymphocyte proliferation. Twenty-four hours after initiating the cultures, the films were added to the 8.8 mL culture volume to achieve final concentrations of 50, 100 and 500 μg mL−1. Concurrently, separate cultures were treated solely with mitomycin C (MMC, 0.5 μg mL−1) to serve as a positive control, following established methods (OECD Test Guideline 487, 2023). At 44 hours of incubation, cytochalasin-B (Cyt-B) was added to a final concentration of 6 μg mL− 1 to arrest cytokinesis in dividing cells. The cultures were maintained for a total of 72 h from initiation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Subsequently, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature. The resulting cell pellets were subjected to a 3 min mild hypotonic treatment at room temperature using a 3:1 solution of Ham’s medium and Milli-Q H2O. Fixation was then performed four times with a freshly prepared 5:1 methanol/acetic acid mixture, each for 10 minutes.

Cell monolayers, prepared on microscope slides, were stained with 10% Giemsa solution and subsequently mounted using DPX. Slides were then scored for the presence of one or more micronuclei within binucleated cells. For each experimental condition, a minimum of 2000 binucleated (BN) cells exhibiting intact cytoplasm were evaluated (1000 cells per donor culture, N=2). Micronucleus (MN) frequency was subsequently expressed in parts per thousand (‰) [

43]. Cytotoxicity was evaluated by determining the Cytokinesis Block Proliferation Index (CBPI), Replicative Index (RI), and percentage of Cytostasis (%Cyt). These indices were derived from scoring a minimum of 1000 cells per treatment condition (500 cells from each donor culture), applying established formulas as outlined in [

42]. CBPI is given by the equation:

where M1, M2, M3 and M4 correspond to the numbers of cells with one, two, three, and four nuclei and N is the total number of cells [

44].

2.7. Fresh Minced Pork Packaging Preservation Test with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP Active Films

Fresh minced pork was given by the Ayfantis local meat processing company. Twelve BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and twelve BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films with ~11 cm diameter and ~0.15 mm thickness was prepared and used for wrapping fresh minced pork. Two films were used to aseptically wrap ~40–50 g of minced pork. The wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films was then placed inside the Ayfantis company’s commercial wrapping paper, without the inner film Ayfantis. 40–50 g of minced pork was aseptically wrapped in the commercial packaging paper of the Ayfantis company and labeled as control sample. For all tested packaging systems, samples for the 2nd, 4th, and 6th, day of storage were prepared and stored at 4 ± 1 °C.

During the 6 days of storage the determination of the Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) values, the heme iron content, and the total Viable Count (TVC), of minced pork were carried out by following the methodology described in detail in supplementary material file.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All obtained data from tensile properties measurements, along with, antioxidant activity, antibacterial activity, toxicity, total viable count, TBARS and heme iron content were subjected to statistical analysis. For the statistical analysis the Krüskal-Wallis non-parametric method was applied to indicate the significance of difference between the properties’ mean values. Assuming a significance level of p < 0.05, all measurements were conducted using three separate samples. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software (v. 28.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Detailed statistical analysis results also included in supplementary material file.

3. Results

3.1. XRD Analysis

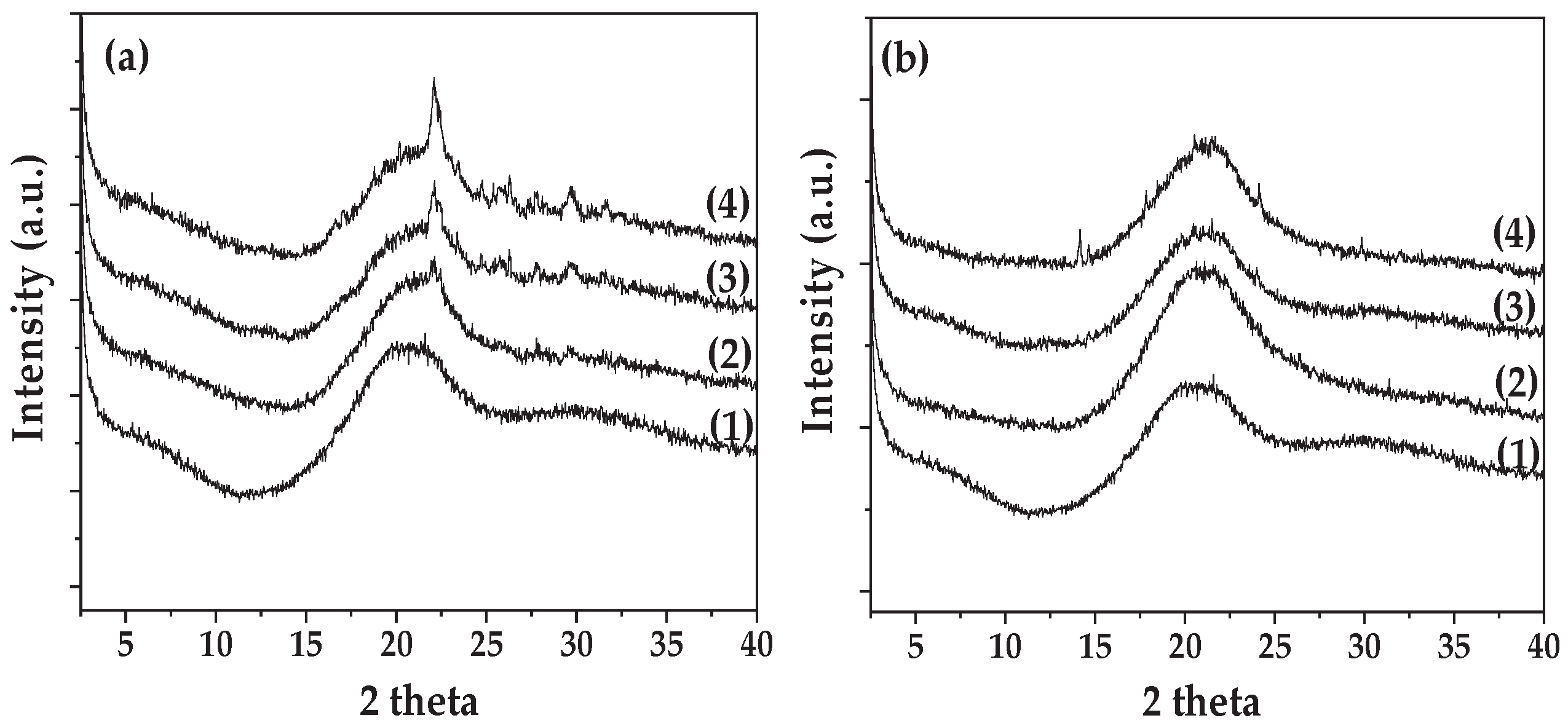

In

Figure 1 the XRD plots of all the BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ (

Figure 1(a)) and the BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP (

Figure 1(b)) films are presented.

As it is observed in

Figure 1 the XRD plot of pure BSG/Gel/Gl film (see plot line (1) in both

Figure 1(a) and 1(b)) shows a broad peak at around 20

o 2theta corresponding to an amorphous crystal phase. The addition of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP do not affect the amorpous crystal phase of pure BSG/Gel/Gl suggesting a good dispersion of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP in the BSG/Gel/Gl matrix. In the case of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films small inflection peaks between 20-30

o 2theta assigned to NZ crysal phase suggesting the presence of NZ in the BSG/Gel/Gl matrix [

45,

46].

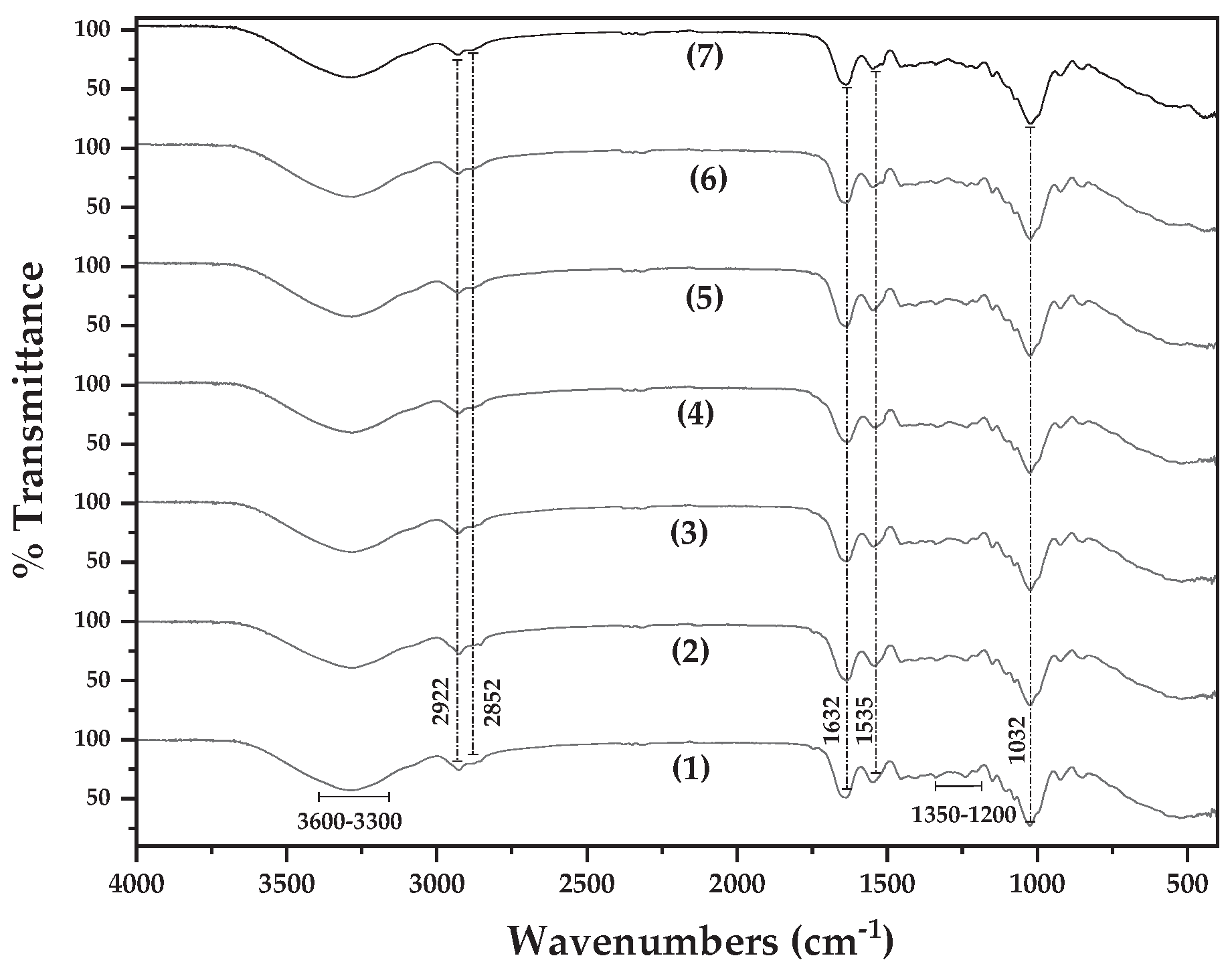

3.2. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy

In

Figure 2 the recorded FTIR-ATR plots of EG@NZ nanohybrid (plot line (1)) and pure ClP are presented for comparsion.

The FTIR-ATR plot line (1) corresponds to EG@NZ nanohybrid and it is a mix of EG and NZ bands [

47]. The bands correspond to NZ are as follows: The bands at 3619, 3465 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the O–H stretching bonding vibrations, while the band at 1650 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the O–H bending bonding vibration. The band at 1090 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the Si–O stretching bonding vibration, and the band at 468 cm⁻¹ to the Si–O bending bonding vibration of NZ [

48].

The bands correspond to EG molecules adsorbed in NZ are as follow: The broad band in the region of 3300–3550 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the stretching bonding vibrations of EG’s hydroxyl groups [

49]. The peaks at 3000 and 3040 cm⁻¹ correspond to the stretching bonding vibrations of the CH=CH–H groups of EG. The absorption bands in the range of 650–1000 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the bending vibrations of the CH=CH–H groups of EG [

47,

49,

50]. The peaks at 2870 and 2960 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching bonding vibrations of methyl (CH₃) groups of EG, correspondigly. The peaks at 1370 and 1450 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric bending bonding vibrations of EG’s CH₃ groups [

49]. Finally, the peaks at 1514, 1608, and 1637 cm⁻¹ are assigned to stretching bonding vibrations of the aromatic C=C group of EG [

47,

49,

50].

In the FTIR-ATR plot line (2) of pure ClP many of the characteristic peaks assigned to EG and denoted also in FTIR plot line (2) of EG@NZ nanohybrid are recorded indicating the presence of EG molecules physically encapsulated in the pure ClP. More specifically, the broad peak around 3400 cm⁻¹ indicates the presence of hydroxyl (-OH) groups, likely from EG and other phenolic compounds [

51]. The peaks at around 2920 cm⁻¹ and 2852 cm⁻¹ represent the stretching vibrations of C-H bonds in methyl (CH

3) and methylene (CH

2) groups, commonly found in aromatic and aliphatic compounds likely from EG [

52]. The peaks at around 1600 cm⁻¹ and 1500 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the aromatic C=C bonds, characteristic of EG and other phenylpropanoids [

51]. The peaks around 1260 cm⁻¹ and 1030 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the C-O stretching vibrations, likely from alcohols, ethers, and esters [

52]. Finally, the plot region below 1000 cm⁻¹ at provides a unique "fingerprint" for the ClP, allowing for differentiation from other substances. The specific peak positions and intensities in this region are highly dependent on the overall chemical composition and structure of the sample [

51,

52,

53].

In

Figure 3 the FTIR-ATR plot of pure BSG/Gel/Gl film (line (1)) as well as the FTIR plots of all BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films (lines (2), (3), and (4)) and all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ active films (lines (5), (6), and (7)) are preseted for comparison.

In all obtained films FTIR-ATR plots the following peaks are observed: The peak between 800 and 600 cm

−1 are assigned to the out-of-plane N-H bonding (amide V) of the protein of BSG [

54]. The peak at 1032 cm⁻¹ observed in all spectra is assigned to the streching bonding vibration of O–H groups of Gl [

55]. The peaks at 1535 cm⁻¹ and 1632 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the N–H bending bonding vibrations of amide II and the C=O stretching bonding vibrations of amide I group of Gel correspondigly. The peak at 1535 cm⁻¹ is assigned also to C–N stretching vibrations of Gel [

56,

57,

58]. The peaks in the range of 1350–1200 cm

−1 is a combination of N-H bending and C-H stretching bonding vibration of amide III group of protein of BSG. The peaks at 2926 cm⁻¹ and 2852 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the saturated C–H stretching bonding vibrations, of both Gel and Gl. The broad peak between 3300 and 3600 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the O–H group stretching bonding vibrations [

54,

56,

57,

58]. Thus in all obtained films FTIR plots the presence of BSG, Gel, and Gl is suggested. No additional peaks correspond to pure ClP and EG@NZ nanohybrid are obtained implying a good dispersion of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP in the BSG/Gel/Gl matrix in line with XRD results.

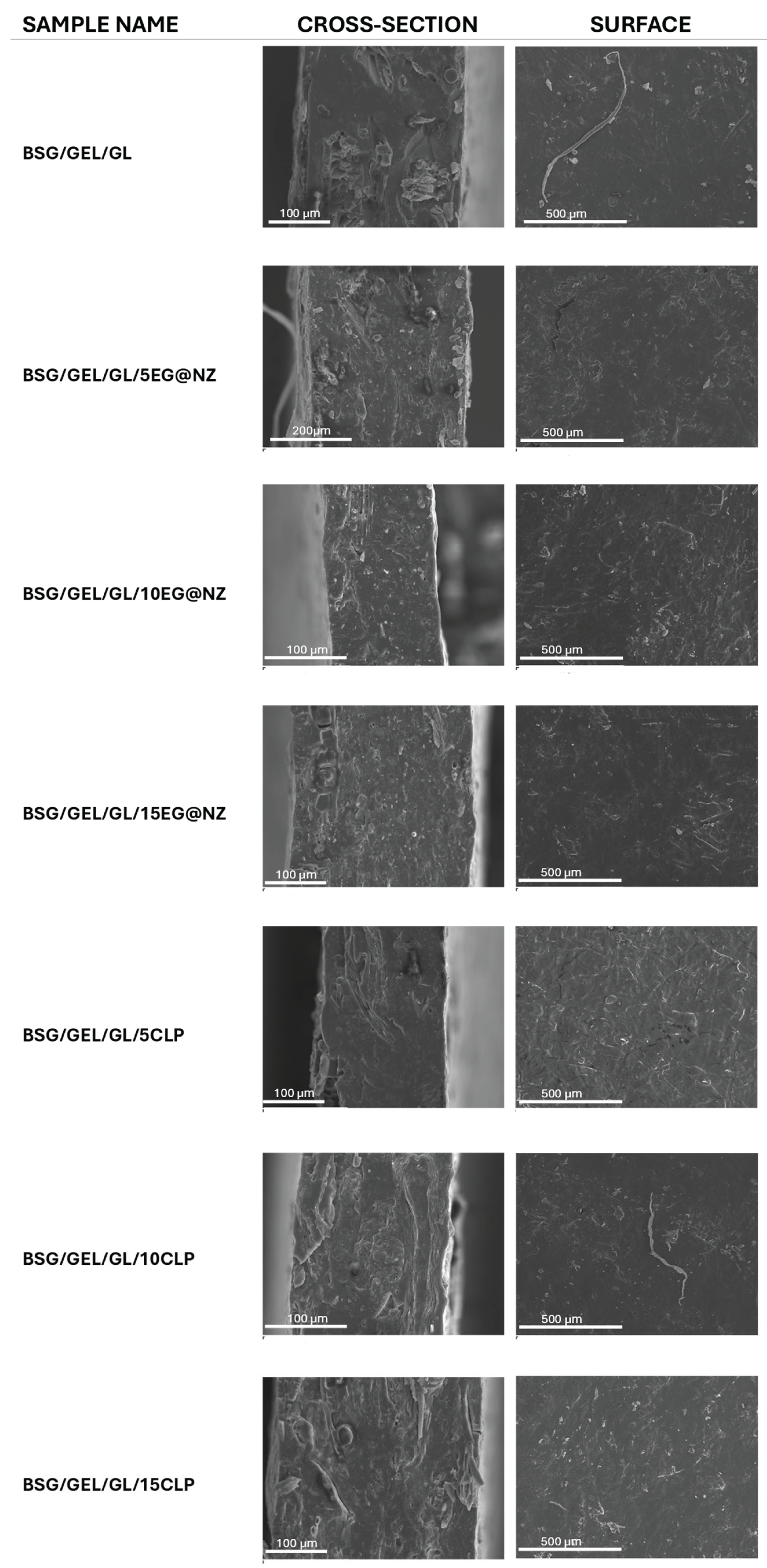

3.3. SEM Analysis

The cross-section morphology as well as the surface topography of all prepared samples was tested via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and the results are illustrated in

Figure 4.

Both cross-section and surface images confirm the production of rather uniform films with a homogeneous dispersion of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP in the BSG/Gel/Gl matrix, as expected by the twin-extrusion procedure followed. In the case of the BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films a uniform dispersion of the EG@NZ nanohybrid is observed in the cross-section images, with only a few agglomerations. Smooth surface topography is observed in all cases, suggesting no deterioration of the quality of the composite films in comparison to the BSG/Gel/Gl matrix.

3.4. Tensile Properties of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

In

Table 2 there are listed the calculated mean values of Elastic Modulus (E), ultimate strength (σ

uts), and %elongation at break (%ε) for comparison.

As it obtained from listed in

Table 2 mean values of Elastic Modulus (E), ultimate strength (σ

uts), and %elongation at break (%ε) for all tested films both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP react as reinforcement agents in BSG/Gel/Gl based films. As the content of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP increases obtained E and

σuts values increase and %ε values decrease. In detail for BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ films the ultimate strength increases up to 88.5%, 173.3%, and 207.7% in comparison to pure BSG/Gel/Gl film, while for BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP, BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films increases up to 213.6%, 210.5% and 211.5% in comparison to pure BSG/Gel/Gl film. This means that in the case of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films increase is e effected by the EG@NZ nanohybrid content and in the case of BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films is not effected vy the ClP content. Simultaneously, for both of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and of BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP the % elongation at break values decrease up to 40-50% in comparison to pure BSG/Gel/Gl film. This means that addition of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP do not dramatically decrease ductility which crusial for the packaging application of such films [

59,

60]. Overall, tensile properties results presented here emplies that both EG@NZ nanohybrid and pure ClP act as reinforcement agents in BSG/Gel/Gl by keeping dactility of obtained films. Tensile properties results are in agreement with SEM images morphology results presented hereabove shown a uniform dispersion of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and pure ClP in the BSG/Gel/Gl matrix.

3.5. Oxygen Barrier Properties of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

In

Table 3 are listed the observed oxygen transmission rate (OTR) values as well as the calculated oxygen permeability Pe

O2 mean values of all tested BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films for comparison.

As it is obtained in

Table 3 pure BSG/Gel/Gl has a high OTR value of 8301.2 ml.m

-2.day

-1 which corresponds to a 2.59x0.19.10

-7 cm

2.s

-1 of oxygen permeability. In the case of all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films zero O.T.R. and PeO

2 values are observed. This means that BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films are impermeable to oxygen. In the case of BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films, film with 5wt. ClP content is impermeable to oxygen while 10, 15 %wt. ClP content films exhibited 5.87.10

-10, and 5.17.10

-10 mean Pe

O2 correspondigly. In other words all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films and of BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP film are oxygen impermeable while of BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP and of BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films are high oxygen barrier films. High and or zero oxygen barrier results for BSG based films are for the first time reported here. The oxygen barrier results presented here are in line with previous reports claim that protein based films such as gelatin based exhibit high oxygen barrier [

61,

62]. The zero and or high oxygen results presented here are also in line with recent reports validating the use of extrusion molding and compression process method for the preparation of such films [

55,

63,

64].

3.6. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

Calculated mean TPC values for all tested films are listed in

Table 4 for comparison. As it is obtained all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films exhibited much higher TPC values than the BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP ones. Moreover for both BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films recorded TPC values effected by the content of EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP dispersed in BSG/Gel/Gl matrix correspondigly. Thus, the higher of EG@NZ and ClP content the higher of recorded TPC values. The highest TPC value of 291.77± 12.81 mgGAE/L is observed for BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film and it is equal to this reported recently by Vieira et al which prepared films with BSG and cassava starch and poly(vinyl alcohol) and obtained a TPC value of 263.23 ± 10.97 mg GAE/L [

20].

3.7. Antioxidant Activity of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

EC

60 values of all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films as well as pure BSG/Gel/Gl film are listed in

Table 4. All experimental data and the obtained linear plots used for the calculation of EC

60 values of all tested films are shown in supplementary file. EC

60 values are recommended for films with high antioxidant activity [

65]. As it is obtained in

Table 4 pure BSG/Gel/Gl film exhibited a significant antioxidant activity up to 69.6 mg/L. Antioxidant capacity of BSG is well known due to its content of various phenolic compounds [

18,

19,

20,

23]. The addition of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and ClP enhances evenmore the atnioxidant capacity of obtained BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films. Thus, all obtained films could be characterized as films with high antioxidant capcity. Overall, BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films exhibited higher antioxidant activity than BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films and films with 10%wt. content of EG@NZ and ClP are the most active ones. The higher antioxidant activity values recorded for BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films against BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP ones is in accordance with the higher TPC values recorded for BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ films against BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP ones.

3.8. Antibacterial Activity of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films

The antibacterial activity results of all obtained films against the Gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) are presented in

Table 5. S. aureus showed sensitivity to BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films, presenting halos of 25, 45 and 25 mm, respectively. In the case of E. coli, antibacterial activity was observed only for the BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ films, which produced inhibition zones of 20 mm and 30 mm, respectively. No antibacterial effect was observed for the unmodified BSG/Gel/Gl film against either bacterial strain under the test conditions, indicating that the incorporation of EG@NZ and ClP components was essential for imparting antibacterial activity. A comparative analysis indicates that films containing EG@NZ exhibited superior antibacterial activity, particularly at higher concentrations (15%), against both bacterial strains. This result is in agreemnt with previous reports suggest the antibacterial activity of EG when it is incorporated in packaging films [

66,

67,

68]. Herein it is reported for the first time the excel of nanoencapsulated EG of EG@NZ based films than physical encapsulated EG in ClP based films. In particular, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ demonstrated the most potent effect, with the largest inhibition zones against both S. aureus and E. coli. This suggests a concentration-dependent enhancement of antimicrobial properties due to the increased availability of EG. The stronger activity against S. aureus compared to E. coli may be likely due to structural differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The outer membrane in E. coli can act as a barrier, making it more resistant.

3.7. Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Effects of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP Films in Human Lymphocytes

Table 6 presents the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity results for the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films, as well as for the unmodified BSG/Gel/Gl control film.

The micronucleus frequency (‰MN), a well-established biomarker for assessing genotoxic effects in human lymphocytes, was evaluated for selected film formulations. These two modified formulations were specifically chosen for testing, as they represent the highest loadings of EG@NZ and ClP, respectively, and thus provide the most stringent conditions for evaluating potential toxicological effects.

The analysis aimed to determine whether the incorporation of bioactive components at maximum concentrations could induce cytotoxic or genotoxic responses in human lymphocytes. The results serve to assess the safety profile of the developed active films for potential applications in food contact materials or biomedical packaging.

As shown in

Table 6, the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films, along with the pure BSG/Gel/Gl film, exhibited lower micronucleus frequencies (‰MN, genotoxicity index) and cytostasis percentages (% Cytostasis, cytotoxicity index) compared to the mitomycin C (MMC) positive control at all tested concentrations (50, 100, and 500 μg/mL). These results indicate that none of the film formulations induced significant genotoxic or cytotoxic effects relative to the established positive control.

In more setail, the ‰MN values of all films were equal to or lower than those observed in the control group, indicating no significant increase in micronuclei frequency at any of the tested concentrations. This suggests that none of the formulations exerted genotoxic effects under the conditions examined. These findings support the genetic safety of the developed materials, consistent with international guidelines for genotoxicity testing [

42,

69]. In terms of cytotoxicity, both BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP and BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ films exhibited slightly elevated %cytostasis values compared to the pure BSG/Gel/Gl film. However, these values remained well within the acceptable range as defined by OECD 487 guidelines [

43,

70]. The observed mild cytotoxic effects were only present at the highest concentrations tested and did not exceed regulatory thresholds. Importantly, no associated genotoxicity was observed, indicating that the inclusion of ClP or EG@NZ does not compromise genomic integrity. Notably, the lowest ‰MN and %cytostasis values were recorded for the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film. This result suggests that nanoencapsulation of EG (the principal bioactive compound in ClP) in nanozeolite effectively reduces both genotoxicity and cytotoxicity compared to its direct incorporation via clove powder. These findings align with recent studies reporting that nanoencapsulation of EG in carriers such as montmorillonite nanoclay and nanozeolite reduces the cytotoxic profile of active packaging films based on pork gelatin matrices [

47,

55].

3.8. Packaging Preservation Test-Minced Pork Wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP Active Films

3.8.1. TVC

The calculated TVC mean values of minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films as well as with commercial paper (control) as a function of the storage time are listed in

Table 7 for comparison.

As it is obtained in

Table 7 both BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films succeed to maintain lower TVC growth rates of fresh minced pork than the control sample during the six days of storage. In advance minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film exhibited lower TVC growth rate than minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active film. This result is in line with the highest antibacterial activity recorded hereabove against Gram-negative

E. coli and Gram-positive

S. aureus for BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film. As it is listed in

Table 7 minced pork wrapped with the commercial paper (control sample) exceeds the TVC limit of acceptance (7 logCFU/g) after the 4

th day of storage [

71]. On the contrary, minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film exhibited TVC value lower than 7 logCFU/g since the 6

th day of storage, while minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active film exhibited TVC value a little bit higher from 7 logCFU/g in the 6

th day of storage. In other words, it could be stated that BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film succeed to extend the shelf-life of minced pork from microbiological point of view for approximately two days and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active film succeed to extend the shelf-life of minced pork from microbiological point of view for approximately one day.

3.8.2. Lipid Oxidation

The calculated TBA mean values of minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films as well as with commercial paper (control) as a function of the storage time are listed in

Table 8 for comparison.

As it is obtained from the listed in

Table 8 mean TBARS values both BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films prevent minced pork lipid oxidation during the six days of storage in comparison to minced pork wrapped in commercial aper film. Additionally, minced pork wrapped in the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film recorded the lowest TBARS increment rate implying the highest lipid oxidation protection of wrapped minced pork. Thus, on the 6

th day of storage, minced pork wrapped in the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film had a TBARS value ~20% lower than that for minced pork meat wrapped in commercial film. This result is in accordance with the zero oxygen barrier of such active film and its enhanced antioxidant activity.

3.8.3. Heme Iron Content

The calculated heme iron content mean values of minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films as well as with commercial paper (control) as a function of the storage time are listed in

Table 8 for comparison.

As it is obtained from the listed in

Table 8 mean heme iron content values both BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films succeeded in keeping wrapped minced pork with higher heme iron contents during the six days of storage in comparison to the minced pork wrapped in commercial paper (control sample). In other words, both BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films succeeded to preserve fresh minced pork in a higher nutritional value during the six days of storage. Overall, the highest heme iron content values during the six days of storage were obtained for minced pork wrapped in the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film. This result supports the lowest TBARS values obtained for the minced pork wrapped with the same BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film. So, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ prevents minced pork from lipid oxidation and keeps it with the highest nutritional value.

TVC, TBARS and heme iron content results presented hereabove for the preservation of fresh minced pork wrapped with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP are supported by several previous report were EG and ClP have been used for the preservation of fresh meat [

41,

72,

73,

74,

75]. By inhibiting microbial growth and lipid oxidation, EG can help to maintain the color, texture, and overall quality of fresh meat during storage [

72,

73,

76]. In advance previous reports indicate that ClP can be effective in extending the shelf life of various meat products, including chicken and beef [

41,

74,

75].

4. Discussion

In the current study BSG volarized to edible active packaging films via the extrusion-compression molding method. Gel and Gl was used as reinforcement and plasticizer correspondingly to obtain an edible BSG/Gel/Gl matrix. This pure BSG/Gel/Gl matrix was farther reinforced and activated by adding EG@NZ nanohybrid and pure ClP at 5, 10, and 15 %wt. To the best of our knowledge the obtained BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films were for the first time developed and characterized here. The physicochemical characterization of obtained BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films took place via XRD analysis, FTIR-ATR spectroscopy and SEM images analysis (surface and cross section), in line with XRD and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy, shown that both EG@NZ nanohybrid and pure ClP were homogeneously dispersed in BSG/Gel/Gl matrix. This effective dispersion of both EG@NZ nanohybrid and pure ClP in BSG/Gel/Gl matrix depicted in the enhancement of ultimate strength of all obtained of obtained BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films. Simultaneously, % elongation at break of all obtained films did not dramatically reduce which means that all films kept their ductility and are suitable for flexible packaging applications. In advance, both BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films shown high oxygen barrier properties. For all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ active films zero OTR values were recorded while zero OTR value was recorded for BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP active film and low OTR values were recorded for both BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP, and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films. This means that EG@NZ based active films excel than ClP based active films in oxygen barrier properties. Zero and/or high oxygen barrier results presented here are for the first time reported. To the best of our knowledge there is no previous report with BSG based films studying the oxygen barrier of such films. Cunha et al reported the preparation, characterization, and film blowing of polyhydroxybutyrate-valerate (PHBV)/beer spent grain fibers (BSGF) composites and found that the addition of BSGF increases the permeability of PHBV films to O

2, CO

2, and water vapor. Permeability to CO

2 and O

2 increases tenfold when incorporating 5 %wt. BSGF [

77]. Zero and/or high oxygen barrier results presented validating the use of Gel protein as reinforcement and high barrier agent and are the use of extrusion compression molding process used for the preparation of films [

47,

55].

Both BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films exhibited high TPC contents, high antioxidant activity according to calculated EC60 values with DPPH assay method, and significant antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli food pathogens. In advance BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ active films exhibited much higher TPC, EC60 values and antibacterial activity against activity against S. aureus and E. coli food pathogens than BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP active films. More specifically BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film exhibited ~93% higher TPC value and ~90% lower EC60 value than pure BSG/Gel/Gl film while BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active film exhibited ~90% higher TPC value and ~88% lower EC60 value than pure BSG/Gel/Gl film. In addition, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ active film exhibited a 45 mm, and 30 mm inhibition zone against S. Aureus and E. Coli respectively while BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP a 25 mm inhibition zone against S. Aureus and antibacterial activity only under contact area of film against E. Coli. At the same time for both BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active films %cytostasis values remained well within the acceptable range as defined by OECD 487 guidelines, and no associated genotoxicity was observed. The lowest ‰MN and %cytostasis values were recorded for the BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film. Overall, the results of TPC content, EC60 values, antibacterial activity tests against S. Aureus and E. Coli and ‰MN and %cytostasis values suggest that nanoencapsulation of EG (the principal bioactive compound in ClP) in NZ increases antioxidant and antibacterial activity and effectively reduces both genotoxicity and cytotoxicity compared to its direct incorporation via clove powder. Thus, this is for the first time reported that nanoencapsulation of bioactive molecules such as EG in NZ excels than physical encapsulation of such bioactive molecules. Overall, this study concludes in BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film as a novel edible, monolayer, zero oxygen barrier active packaging material which could potentially be applied for flexible packaging of meat products.

5. Conclusions

This study by following circular economy and sustainability trends presents the successful for the first time development and characterization of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ (where x=5,10 and 15 %wt.) and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP (where x=5,10 and 15 %wt.) active films via extrusion molding compression method. Simultaneously, a comparison study between EG@NZ nanohybrid and clove powder as both reinforcement and antioxidant/antibacterial agents in BSG/Gel/Gl based active packaging films is for first time reported too. Overall, this study concludes in: (i) the successful development of such BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films as promising monolayer edible, high oxygen barrier active packaging materials with high potential to be used as a flexible packaging material in food industry, and (ii) the advantage of nanotechnology as a method of encapsulating bioactive ΕO components such as ΕΓ in bio-based active food packaging materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1. Gallic acid obtained calibration curve and linear equation; Figure S2. Linear plots used for the calculation of average values of EC

60; Table S1. Experimental data used for the calculation of obtained average EC

60 values; Table S2: Statistical Analysis of Tensile properties of BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films; Table S3: Statistical Analysis of the Oxygen Barrier properties of pure BSG/Gel/Gl film as well as all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films; Table S4: Statistical Analysis of the Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of pure BSG/Gel/Gl film as well as all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films; Table S5: Statistical Analysis for the In Vitro Antioxidant Activity Determination of pure BSG/Gel/Gl film as well as all BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films; Table S6: Statistical Analysis of the Total Viable Count (TVC) of minced pork wrapped with commercial packaging (control sample), BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ films and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP film. Table S7: Statistical Analysis of Lipid Oxidation with Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances of minced pork wrapped with commercial packaging (control sample), BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ films and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP film; Table S8: Statistical Analysis of Heme Iron Content Measurements of minced meat wrapped with commercial packaging (control sample), BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ films and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP film; Table S9: Statistical Analysis of Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films in Human Lymphocytes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—C.E.S. and A.E.G.; data curation—Z.N., A.K.; A.A.L., A.T.; A.V.; P.S.; K.Z.; M.D.; G.B.; C.P.; A.E.G. and C.E.S.; formal analysis—Z.N.; A.K.; A.A.L.; A.V.; M.D.; P.S.; C.P.; and A.E.G.,; investigation—Z.N.; A.K., A.A.L., and A.E.G.; methodology—A.K., A.A.L., T.A., P.S.; M.D.; P.K.; and A.E.G.; project administration—C.E.S., and A.E.G.; resources—A.K., A.A.L., N.C.; and A.E.G.; software—Z.N., A.A.L., Z.K.; P.K.; G.B.; and A.E.G.; supervision—C.E.S., and A.E.G.; validation—A.K., A.A.L., T.A., A.V.; Z.K.; M.D.; P.S.; G.B.; and A.E.G..; visualization—A.K., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; writing, original draft—A.A. L.; and A.E.G.; writing, review and editing—A.A.L., P.S.; P.K.; K.Z.; C.P.; C.E.S., and A.E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their acknowledgements to Dr. Katerina Govatsi (Laboratory of Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis, University of Patras) for her assistance with electron microscopy images (SEM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cooney, R.; de Sousa, D.B.; Fernández-Ríos, A.; Mellett, S.; Rowan, N.; Morse, A.P.; Hayes, M.; Laso, J.; Regueiro, L.; Wan, A.HL.; et al. A Circular Economy Framework for Seafood Waste Valorisation to Meet Challenges and Opportunities for Intensive Production and Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, B.; Sessa, M.R.; Sica, D.; Malandrino, O. Towards Circular Economy in the Agri-Food Sector. A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Acero, F.J.; Amil-Ruiz, F.; Durán-Peña, M.J.; Carrasco, R.; Fajardo, C.; Guarnizo, P.; Fuentes-Almagro, C.; Vallejo, R.A. Valorisation of the Microalgae Nannochloropsis Gaditana Biomass by Proteomic Approach in the Context of Circular Economy. J. Proteomics 2019, 193, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillard, V.; Gaucel, S.; Fornaciari, C.; Angellier-Coussy, H.; Buche, P.; Gontard, N. The Next Generation of Sustainable Food Packaging to Preserve Our Environment in a Circular Economy Context. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamam, M.; Chinnici, G.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Pecorino, B.; Maesano, G.; D’Amico, M. Circular Economy Models in Agro-Food Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branca, G.; Lipper, L.; McCarthy, N.; Jolejole, M.C. Food Security, Climate Change, and Sustainable Land Management. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for Mitigation of Climate Change: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2069–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabric, A.J. The Climate Change Crisis: A Review of Its Causes and Possible Responses. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, F.; Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Food Waste Generation and Industrial Uses: A Review. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Kassaveti, A. Fish Industry Waste: Treatments, Environmental Impacts, Current and Potential Uses. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Ombra, M.N.; d’Acierno, A.; Coppola, R. Recovery of Biomolecules of High Benefit from Food Waste. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 22, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.J. Sustainability in the Food Industry; John Wiley & Sons, 2011; ISBN 978-1-119-94926-8.

- Okino Delgado, C.H.; Fleuri, L.F. Orange and Mango By-Products: Agro-Industrial Waste as Source of Bioactive Compounds and Botanical versus Commercial Description—A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2016, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umego, E.C.; and Barry-Ryan, C. Review of the Valorization Initiatives of Brewing and Distilling By-Products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 8231–8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquet, P.-L.; Villain-Gambier, M.; Trébouet, D. By-Product Valorization as a Means for the Brewing Industry to Move toward a Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Pontonio, E.; Krona, A.; Jacob, S.; Pinto, D.; Rinaldi, F.; Verardo, V.; Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Bioprocessing of Brewers’ Spent Grain Enhances Its Antioxidant Activity: Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Bioactive Peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludka, F.R.; Klosowski, A.B.; Camargo, G.A.; Justo, A.S.; Andrade, E.A.; Beltrame, F.L.; Olivato, J.B. Brewers’ Spent Grain Extract as Antioxidants in Starch-Based Active Biopolymers. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.M.; Morais, S.; Carvalho, D.O.; Barros, A.A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Guido, Luís. F. Brewer’s Spent Grain from Different Types of Malt: Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity and Identification of the Major Phenolic Compounds. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.J.A.; Ludka, F.R.; Diniz, K.M.; Klosowski, A.B.; Olivato, J.B. Biodegradable Active Packaging Based on an Antioxidant Extract from Brewer’s Spent Grains: Development and Potential of Application. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 2413–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formela, K.; Hejna, A.; Zedler, Ł.; Przybysz, M.; Ryl, J.; Saeb, M.R.; Piszczyk, Ł. Structural, Thermal and Physico-Mechanical Properties of Polyurethane/Brewers’ Spent Grain Composite Foams Modified with Ground Tire Rubber. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 108, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreirinha, C.; Vilela, C.; Silva, N.H.C.S.; Pinto, R.J.B.; Almeida, A.; Rocha, M.A.M.; Coelho, E.; Coimbra, M.A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Freire, C.S.R. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Films Based on Brewers Spent Grain Arabinoxylans, Nanocellulose and Feruloylated Compounds for Active Packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 108, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proaño, J.L.; Salgado, P.R.; Cian, R.E.; Mauri, A.N.; Drago, S.R. Physical, Structural and Antioxidant Properties of Brewer’s Spent Grain Protein Films. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 5458–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Mirkin, S.; Park, H.E. Biodegradable Composite Film of Brewers’ Spent Grain and Poly(Vinyl Alcohol). Processes 2023, 11, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Rehman, A.; Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Ansi, W.; Wei, M.; Yanyu, Z.; Phyo, H.M.; Galeboe, O.; Yao, W. Application of Essential Oils as Preservatives in Food Systems: Challenges and Future Prospectives – a Review. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1209–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angane, M.; Swift, S.; Huang, K.; Butts, C.A.; Quek, S.Y. Essential Oils and Their Major Components: An Updated Review on Antimicrobial Activities, Mechanism of Action and Their Potential Application in the Food Industry. Foods 2022, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpena, M.; Nuñez-Estevez, B.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A. Essential Oils and Their Application on Active Packaging Systems: A Review. Resources 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Davis, A.; White, S.; Kassama, L.S.; Coleman, S.; Shaw, A.; Mendonca, A.; Cooper, B.; Thomas-Popo, E.; Gordon, K.; London, L. A Review of Regulatory Standards and Advances in Essential Oils as Antimicrobials in Foods. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.A.; Siengchin, S.; Parameswaranpillai, J. Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents in Biopolymer-Based Food Packaging - A Comprehensive Review. Food Biosci. 2020, 38, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.H.; Trigueiro, P.; Souza, J.S.N.; de Carvalho, M.S.; Osajima, J.A.; da Silva-Filho, E.C.; Fonseca, M.G. Montmorillonite with Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents, Packaging, Repellents, and Insecticides: An Overview. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saucedo-Zuñiga, J.N.; Sánchez-Valdes, S.; Ramírez-Vargas, E.; Guillen, L.; Ramos-deValle, L.F.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.; Uribe-Calderón, J.A.; Valera-Zaragoza, M.; Lozano-Ramírez, T.; Rodríguez-González, J.A.; et al. Controlled Release of Essential Oils Using Laminar Nanoclay and Porous Halloysite / Essential Oil Composites in a Multilayer Film Reservoir. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 316, 110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.C.; Valencia, G.A.; López Córdoba, A.; Ortega-Toro, R.; Ahmed, S.; Gutiérrez, T.J. Zeolites for Food Applications: A Review. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Leontiou, A.A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Development of Carvacrol@natural Zeolite Nanohybrid and Poly-Lactide Acid / Triethyl Citrate / Carvacrol@natural Zeolite Self-Healable Active Packaging Films for Minced Pork Shelf-Life Extension 2024.

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Leontiou, A.A.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Moschovas, D.; Andritsos, N.D.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Novel Carvacrol@activated Carbon Nanohybrid for Innovative Poly(Lactide Acid)/Triethyl Citrate Based Sustainable Active Packaging Films. Polymers 2025, 17, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Baikousi, M.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karageorgou, I.; Iordanidis, G.; Emmanouil-Konstantinos, C.; Leontiou, A.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Kehayias, G.; et al. Low-Density Polyethylene-Based Novel Active Packaging Film for Food Shelf-Life Extension via Thyme-Oil Control Release from SBA-15 Nanocarrier. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ge, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y. Eugenol Embedded Zein and Poly(Lactic Acid) Film as Active Food Packaging: Formation, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Effects. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navikaite-Snipaitiene, V.; Ivanauskas, L.; Jakstas, V.; Rüegg, N.; Rutkaite, R.; Wolfram, E.; Yildirim, S. Development of Antioxidant Food Packaging Materials Containing Eugenol for Extending Display Life of Fresh Beef. Meat Sci. 2018, 145, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kechagias, A.; Salmas, C.E.; Chalmpes, N.; Leontiou, A.A.; Karakassides, M.A.; Giannelis, E.P.; Giannakas, A.E. Laponite vs. Montmorillonite as Eugenol Nanocarriers for Low Density Polyethylene Active Packaging Films. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barboza, J.N.; da Silva Maia Bezerra Filho, C.; Silva, R.O.; Medeiros, J.V.R.; de Sousa, D.P. An Overview on the Anti-Inflammatory Potential and Antioxidant Profile of Eugenol. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3957262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Sahoo, J.; Chatli, K.M.; Biswas, A.K. Effect of Clove Powder and Modified Atmosphere Packaging on the Oxidative and Sensory Quality of Chicken Meat Caruncles During Ambient Storage (35±20C) Conditions. J. Meat Sci. 2014, 10, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mh, T. Effect of Clove Powder and Garlic Paste on Quality and Safety of Raw Chicken Meat at Refrigerated Storage. 2018, 1. 1.

- Test, No. 487: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test Available online:. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-487-in-vitro-mammalian-cell-micronucleus-test_9789264264861-en.html (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Fenech, M.; Chang, W.P.; Kirsch-Volders, M.; Holland, N.; Bonassi, S.; Zeiger, E. HUMN Project: Detailed Description of the Scoring Criteria for the Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus Assay Using Isolated Human Lymphocyte Cultures. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2003, 534, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surrallés, J.; Xamena, N.; Creus, A.; Catalán, J.; Norppa, H.; Marcos, R. Induction of Micronuclei by Five Pyrethroid Insecticides in Whole-Blood and Isolated Human Lymphocyte Cultures. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. 1995, 341, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmas, C.Ε.; Kollia, E.; Avdylaj, L.; Kopsacheili, A.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Katerinopoulou, K.; Kehayias, G.; Karakassides, A.; et al. Thymol@Natural Zeolite Nanohybrids for Chitosan/Poly-Vinyl-Alcohol Based Hydrogels Applied As Active Pads for Strawberries Preservation 2023.

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Moschovas, D.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Georgopoulos, S.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Aktypis, A.; Proestos, C.; Karakassides, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. The Increase of Soft Cheese Shelf-Life Packaged with Edible Films Based on Novel Hybrid Nanostructures. Gels 2022, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kechagias, A.; Leontiou, A.A.; Oliinychenko, Y.K.; Stratakos, A.Ch.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Katerinopoulou, K.; Baikousi, M.; Andritsos, N.D.; Proestos, C.; Chalmpes, N.; et al. Eugenol@Natural-Zelolite vs Citral@Natural-Zeolite Nanohybrids for Gelatine-Based Edible-Active Packaging Films 2025.

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Leontiou, A.A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Shelf Life of Minced Pork in Vacuum-Adsorbed Carvacrol@Natural Zeolite Nanohybrids and Poly-Lactic Acid/Triethyl Citrate/Carvacrol@Natural Zeolite Self-Healable Active Packaging Films. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhoot, G.; Auras, R.; Rubino, M.; Dolan, K.; Soto-Valdez, H. Determination of Eugenol Diffusion through LLDPE Using FTIR-ATR Flow Cell and HPLC Techniques. Polymer 2009, 50, 1470–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmpes, N.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Talande, S.; Bakandritsos, A.; Moschovas, D.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Karakassides, M.A.; Gournis, D. Nanocarbon from Rocket Fuel Waste: The Case of Furfuryl Alcohol-Fuming Nitric Acid Hypergolic Pair. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthipan, P.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Devanesan, S.; Rajasekar, A. Evaluation of Syzygium Aromaticum Aqueous Extract as an Eco-Friendly Inhibitor for Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion of Carbon Steel in Oil Reservoir Environment. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibazar, S.P.; Fateh, S.; Daneshmandi, S. Clove (Syzygium Aromaticum) Ingredients Affect Lymphocyte Subtypes Expansion and Cytokine Profile Responses: An in Vitro Evaluation. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Członka, S.; Strąkowska, A.; Strzelec, K.; Kairytė, A.; Kremensas, A. Bio-Based Polyurethane Composite Foams with Improved Mechanical, Thermal, and Antibacterial Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroti, G.K.; Saini, C.S. Development of Edible Films from Protein of Brewer’s Spent Grain: Effect of pH and Protein Concentration on Physical, Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Films. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, A.; Leontiou, A.A.; Oliinychenko, Y.K.; Stratakos, A.C.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Proestos, C.; Giannelis, E.P.; Chalmpes, N.; Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E. Eugenol@Montmorillonite vs. Citral@Montmorillonite Nanohybrids for Gelatin-Based Extruded, Edible, High Oxygen Barrier, Active Packaging Films. Polymers 2025, 17, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karydis-Messinis, A.; Moschovas, D.; Markou, M.; Gkantzou, E.; Vasileiadis, A.; Tsirka, K.; Gioti, C.; Vasilopoulos, K.C.; Bagli, E.; Murphy, C.; et al. Development, Physicochemical Characterization and in Vitro Evaluation of Chitosan-Fish Gelatin-Glycerol Hydrogel Membranes for Wound Treatment Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 6, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momtaz, M.; Momtaz, E.; Mehrgardi, M.A.; Momtaz, F.; Narimani, T.; Poursina, F. Preparation and Characterization of Gelatin/Chitosan Nanocomposite Reinforced by NiO Nanoparticles as an Active Food Packaging. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.D.; Flores, S.K.; Marangoni, A.G.; Gerschenson, L.N.; Rojas, A.M. Development of a High Methoxyl Pectin Edible Film for Retention of l -(+)-Ascorbic Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6844–6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, M.I.; Ghaffar,Tayabba; Najeeb,Jawayria; Hussain,Zaib; Khalid,Rida; and Zahid, H. Potential Perspectives of Biodegradable Plastics for Food Packaging Application-Review of Properties and Recent Developments. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuorwel, K.K.; Cran, M.J.; Orbell, J.D.; Buddhadasa, S.; Bigger, S.W. Review of Mechanical Properties, Migration, and Potential Applications in Active Food Packaging Systems Containing Nanoclays and Nanosilver. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddigam, K.R.; Chee, B.S.; Guilloud, E.; Venkatesh, C.; Koninckx, H.; Windey, K.; Fournet, M.B.; Hedenqvist, M.; Svagan, A.J. High Oxygen Barrier Packaging Materials from Protein-Rich Single-Celled Organisms 2025.

- Chang, Y.; Joo, E.; Song, H.; Choi, I.; Yoon, C.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Han, J. Development of Protein-Based High-Oxygen Barrier Films Using an Industrial Manufacturing Facility. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, M.K.; Steele, R.J.; Kelly, M.; Olivier, S.A.; Chapman, B. Packaging under Pressure: Effects of High Pressure, High Temperature Processing on the Barrier Properties of Commonly Available Packaging Materials. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciannamea, E.M.; Stefani, P.M.; Ruseckaite, R.A. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Compression Molded and Solution Casting Soybean Protein Concentrate Based Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, I.K.; Karabagias, V.K.; Badeka, A.V. In Search of the EC60: The Case Study of Bee Pollen, Quercus Ilex Honey, and Saffron. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 2451–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewska, A.; Majewska-Smolarek, K. Eugenol-Based Polymeric Materials—Antibacterial Activity and Applications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanla-Ead, N.; Jangchud, A.; Chonhenchob, V.; Suppakul, P. Antimicrobial Activity of Cinnamaldehyde and Eugenol and Their Activity after Incorporation into Cellulose-Based Packaging Films. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2012, 25, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.; Neera; Mallesha; Ramana, K. V. Synergized Antimicrobial Activity of Eugenol Incorporated Polyhydroxybutyrate Films Against Food Spoilage Microorganisms in Conjunction with Pediocin. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 170, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids and Materials in Contact with Food (AFC) Related to Use of Formaldehyde as a Preservative during the Manufacture and Preparation of Food Additives | EFSA Available online:. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/415 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Fenech, M. Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus Cytome Assay Evolution into a More Comprehensive Method to Measure Chromosomal Instability. Genes 2020, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y. Rapid Detection of Total Viable Count (TVC) in Pork Meat by Hyperspectral Imaging. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Ding, W. Eugenol Nanocapsules Embedded with Gelatin-Chitosan for Chilled Pork Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.-G.; Shen, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhang, X.-X.; Thakur, K.; Khan, M.R.; Wei, Z.-J. Preparation and Characterization of Eugenol Incorporated Pullulan-Gelatin Based Edible Film of Pickering Emulsion and Its Application in Chilled Beef Preservation. Molecules 2023, 28, 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Sahoo, J.; Chatli, M.K.; Biswas, A.K. Shelf Life Evaluation of Raw Chicken Meat Emulsion Incorporated with Clove Powder, Ginger and Garlic Paste as Natural Preservatives at Refrigerated Storage (4±1°C).

- Kumudavally, K.V.; Tabassum, A.; Radhakrishna, K.; Bawa, A.S. Effect of Ethanolic Extract of Clove on the Keeping Quality of Fresh Mutton during Storage at Ambient Temperature (25 ± 2 °C). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilen, M.V.; Uzun, P.; Yıldız, H.; Fındık, B.T. Evaluation of the Effect of Active Essential Oil Components Added to Pickled-Based Marinade on Beef Stored under Vacuum Packaging: Insight into Physicochemical and Microbiological Quality. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 418, 110733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, M.; Berthet, M.-A.; Pereira, R.; Covas, J.A.; Vicente, A.A.; Hilliou, L. Development of Polyhydroxyalkanoate/Beer Spent Grain Fibers Composites for Film Blowing Applications. Polym. Compos. 2015, 36, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) XRD plots of (1) BSG/Gel/Gl film, (2) BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ film, (3) BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ film, and (4) BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film, (b) (1) BSG/Gel/Gl film, (2) BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP film, (3) BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP film, and (4) BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP film.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD plots of (1) BSG/Gel/Gl film, (2) BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ film, (3) BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ film, and (4) BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ film, (b) (1) BSG/Gel/Gl film, (2) BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP film, (3) BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP film, and (4) BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP film.

Figure 2.

FTIR-ATR plots of (1) EG@NZ nanohybrid and (2) pure ClP.

Figure 2.

FTIR-ATR plots of (1) EG@NZ nanohybrid and (2) pure ClP.

Figure 3.

FTIR-ATR plots of (1) pure BSG/Gel/Gl film, (2) BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP active film, (3) BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP active film, (4) BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active film, (5) BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ active film, (6) BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ active film, and (7) BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ active film.

Figure 3.

FTIR-ATR plots of (1) pure BSG/Gel/Gl film, (2) BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP active film, (3) BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP active film, (4) BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP active film, (5) BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ active film, (6) BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ active film, and (7) BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ active film.

Figure 4.

Representative SEM images of the cryo-cut cross-section (left column) and of the surface (right column) of all prepared films. The magnification level was set at 300x (BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP, BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP) and 400x (BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP) for the cross-section images and at 100x for the surface images.

Figure 4.

Representative SEM images of the cryo-cut cross-section (left column) and of the surface (right column) of all prepared films. The magnification level was set at 300x (BSG/Gel/Gl, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP, BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP) and 400x (BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ, BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP) for the cross-section images and at 100x for the surface images.

Table 1.

Sample names of the films weighed masses of their composites (BSG, Gel, Gl, H2O, EG@NZ and ClP) and twin extruder operating conditions (temperature, rotating speed and operating time). .

Table 1.

Sample names of the films weighed masses of their composites (BSG, Gel, Gl, H2O, EG@NZ and ClP) and twin extruder operating conditions (temperature, rotating speed and operating time). .

| Sample Name |

BSG

(g) |

Gel

(g) |

Gl

(g) |

H2O

(g) |

EG@NZ

(g) |

ClP

(g) |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

- |

- |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

0.347 |

- |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

0.733 |

- |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

1.160 |

- |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

- |

0.347 |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

- |

0.733 |

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1.6 |

- |

1.160 |

|

Table 2.

Obtained mean values of Elastic Modulus (E), ultimate strength (σuts), and %elongation at break (%ε) for all tested films.

Table 2.

Obtained mean values of Elastic Modulus (E), ultimate strength (σuts), and %elongation at break (%ε) for all tested films.

| |

Elastic Modulus E(MPa)

average± stdev |

σuts (MPa)

average± stdev |

Elongation at break - %ε

average± stdev |

| BSG/Gel/Gl |

17.57±5.62 d

|

1.83±0.29 c

|

27.25±8.12 a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ |

43.97±7.76 cd

|

3.80±0.96 bc

|

17.71±3.17 bc

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ |

52.56±7.75 bc

|

5.07±0.52 ab

|

16.51±1.32 bc

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

77.01±13.76 a

|

5.82±0.47 a

|

14.28±1.50 c

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP |

59.77±7.45 abc

|

5.74±0.70 a

|

23.08±2.63 a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP |

71.17±12.60 a

|

5.55±0.72 a

|

17.77±1.59 b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

70.29±15.92 ab

|

5.54±0.59 a

|

15.84±2.57 bc

|

Table 3.

Oxygen transmission rate (OTR) mean values, as well as the calculated oxygen permeability PeO2 mean values of all tested films.

Table 3.

Oxygen transmission rate (OTR) mean values, as well as the calculated oxygen permeability PeO2 mean values of all tested films.

| Sample name |

average thickness (mm) |

O.T.R.

(ml.m-2.day-1) |

PeO2

(cm2.s-1) |

| BSG/Gel/Gl |

0.27±0.01 a

|

8301.2±450.3 a

|

2.59±0.19.10-7 a |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ |

0.25±0.02 a

|

0 b

|

0 b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ |

0.27±0.01 a

|

0 b

|

0 b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

0.25±0.02 a

|

0 b

|

0 b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP |

0.27±0.02 a

|

0 b

|

0 b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP |

0.25±0.02 a

|

22.8±1.5 a

|

5.87.10-10±0.42.10-10 a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

0.25±0.01 a

|

16.8±1.1 a,b

|

5.17.10-10±0.32.10-10 a,b

|

Table 4.

EC60 antioxidant activity values and total phenolic content of all tested films.

Table 4.

EC60 antioxidant activity values and total phenolic content of all tested films.

| Sample name |

EC60

mg/ml |

TPC1

(mg GAE / L) |

| BSG/Gel/Gl |

23.46 ± 3.13 a

|

17.28 ± 0.86 c

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ |

2.80 ± 0.55 b,c

|

95.28 ± 4.76 bc

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ |

1.83 ± 0.68 c

|

256.15 ± 14.59 ab

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

2.70 ± 0.40 b,c

|

291.77 ± 12.81 a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP |

5.02 ± 0.25 a,b

|

67.28 ± 3.36 bc

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP |

2.50 ± 0.26 c

|

135.07 ± 6.75 abc

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

3.00 ± 0.12 a,b,c

|

184.28 ± 9.21 ab

|

Table 5.

Comparison of antimicrobial activities from BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films on diffrent bacteria strains.

Table 5.

Comparison of antimicrobial activities from BSG/Gel/Gl/xEG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/xClP films on diffrent bacteria strains.

| Samples |

ZOI (mm) |

| |

S. aureus |

E. coli |

| BSG/Gel/Gl |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5EG@NZ |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ |

25 |

20 |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

45 |

30 |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/5ClP |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

25 |

N.D. |

| ZOI: Zone of Inhibition; N.D.: Not Detected |

Table 6.

Percentages of MN, BNMN, Cytostasis, and CBPI in Human lymphocytes treated with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films .

Table 6.

Percentages of MN, BNMN, Cytostasis, and CBPI in Human lymphocytes treated with BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films .

| Concentrations (μg/mL) |

BN |

MN±S.E. (‰) |

CBPI±S.E |

Cytostasis (%) |

| Control |

1000 |

2 ± 0

|

1.65 ± 0.03

|

0 |

| MMC (0.05) |

1000 |

13 ± 2.8

|

1.48 ± 0.02

|

25.6 ± 2

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl |

| 50 |

1000 |

1 ± 0 A,a

|

1.64 ± 0.01 A,a

|

2.3 ± 2 A,a

|

| 100 |

1000 |

1 ± 0 A,a

|

1.63 ± 0.00 AB,a

|

3.1 ± 0 A,a

|

| 500 |

1000 |

2 ± 0 A,ab

|

1.54 ± 0.01 B,ab

|

17.6 ± 1 A,ab

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

|

|

|

|

| 50 |

1000 |

2 ± 0 AB,a

|

1.57 ± 0.01 A,a

|

12.4 ± 2 B,a

|

| 100 |

1000 |

1 ± 0 B,a

|

1.55 ± 0.01 AB,a

|

15.3 ± 1 AB,a

|

| 500 |

1000 |

3 ± 0 A,a

|

1.51 ± 0.01 B,b

|

22.1 ± 2 A,a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

|

|

|

|

| 50 |

1000 |

1.5 ± 0.7 A,a

|

1.65 ± 0.03 A,a

|

0.00 ± 5 A,a

|

| 100 |

1000 |

2 A,a

|

1.63 ± 0.02 A,a

|

3.5 ± 3 A,a

|

| 500 |

1000 |

1.5 ± 0.7 A,b

|

1.55 ± 0.01 A,a

|

15.6 ± 2 A,b

|

Table 7.

TVC values of minced pork wrapped with the CONTROL, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films with respect to storage time.

Table 7.

TVC values of minced pork wrapped with the CONTROL, BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ, and BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP films with respect to storage time.

| sample |

0th day |

2nd day |

4th day |

6th day |

| TVC (mg/kg) |

|---|

| CONTROL |

4.30±0.05 C,a

|

5.7±0.04 BC,a

|

6.92±0.06 AB,a

|

8.18±0.05 A,a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

3.55±0.04 C,b

|

4.70±0.04 BC,b

|

5.71±0.05 AB,b

|

6.67±0.10 A,b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

3.74±0.04 C,ab

|

4.959±0.04 BC,ab

|

6.01±0.05 AB,ab

|

7.18±0.05 A,ab

|

Table 8.

TBA and heme iron content mean values of minced pork wrapped with the CONTROL, BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ,, and BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP films with respect to storage time.

Table 8.

TBA and heme iron content mean values of minced pork wrapped with the CONTROL, BSG/Gel/Gl/10EG@NZ,, and BSG/Gel/Gl/10ClP films with respect to storage time.

| sample |

0th day |

2nd day |

4th day |

6th day |

| TBARS (mg/kg) |

|---|

| CONTROL |

0.46±0.01 C,a

|

0.59±0.02 BC,a

|

0.75±0.02 AB,a

|

0.81±0.02 A,a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

0.46±0.01 B,a

|

0.47±0.02 B,b

|

0.60±0.02 AB,b

|

0.65±0.02 A,b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

0.46±0.01 C,a

|

0.53±0.02 BC,ab

|

0.68±0.02 AB,ab

|

0.73±0.02 A,ab

|

| sample |

0th day |

2nd day |

4th day |

6th day |

| Heme iron (μg/g) |

| CONTROL |

7.67±±0.16 A,a

|

6.26±0.21 AB,b

|

5.55±0.15 BC,b

|

4.20±0.25 C,b

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15EG@NZ |

7.67±±0.16 A,a

|

7.51±0.25 AB,a

|

6.67±0.18 ABC,a

|

5.04±0.30 C,a

|

| BSG/Gel/Gl/15ClP |

7.67±±0.16 A,a

|

6.89±0.23 AB,ab

|

6.11±0.17 BC,ab

|

4.62±0.28 C,ab

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).