1. Introduction

The almost exponential growth in the number of electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) in use in Europe may be a cause for celebration (reduction in linear pollution from exhaust emissions), but it may also raise concerns about what will happen to the lithium-ion (LIB) batteries from end-of-life EV/PHEVs. On the other hand, there are more and more PV installations where it would be highly desirable to store energy from RES on a daily or multi-day basis, and the new ready-made BESS kits based on LIB batteries available on the market are probably too expensive to do this effectively (which the author will attempt to prove in this article). The benefits of reuse of batteries from BEVs can be divided into several categories. The first category concerns EV/PHEV vehicles that are so damaged that they cannot be returned to road use (as well as cars scrapped for technical reasons, including loss of market value as assessed by the insurer), but still have traction batteries in very good condition (let's call them Grade A). A separate issue is related to BEVs that are so old that they naturally end up being scrapped after 15-20 years of use from the date of sale (Grade C). And there’s also a category of LIB’s of vehicles that are several years old, whose batteries are already significantly worn out (Grade B). The usefulness of LIB class B batteries is difficult to determine, although their theoretical capacity (in kWh) is still significantly higher than that of new BESS, ‘home battery kits’ designed for photovoltaics, that can be purchased in a similar price range. Grade A and B batteries still have (theoretically) significant energy storage capacity and can and should be reused within the circular economy. In Europe, Directive [

1] has been introduced in this regard, which makes many demands – unfortunately, few of them are being implemented in practice by car manufacturers. Previous research conducted by the author with a group of scientists the Lukasiewicz Network[

2], indicated the possibility of solving the technical problems of restoring almost full efficiency of such batteries (grade B or C) by replacing parts of the cells, provided that such cells are available. However, another publication pointed to the problem of providing a warranty for such solutions [

4]. On the other hand, many sources [

3,

4,

5] indicate that the rapidly growing number of BEV/PHEV vehicles in Europe may pose a problem in terms of the disposal and safe management as well as recycling of this type of LIB battery. According to analyses carried out in Sweden [

6], which is important for Poland, as most Swedish manufacturers produce batteries for their EVs in Poland (NorthVolt) and declare “that they will strive to recover more than half of the raw materials for new batteries from BEV batteries by 2030”. But what about BEV manufactured outside of Europe? The BEV battery market therefore seems to be much better organised than the BESS recycling market, which is currently facing serious problems (Far Eastern suppliers are not interested in re-importing used batteries for recycling). Nevertheless, the significant supply of used batteries from BEVs across Europe on the one hand, and the high prices of new BESS sets for domestic use on the other, have already created a market for retrofitting these batteries in many European countries. This, in turn, has already created a market in Europe for ICT work involving the re-engineering of battery transmission from BEVs to PV inverters, which are developing very rapidly not only commercially but also on a crowd-funding basis (7). This has already led to a situation where the market for used battery packs from end-of-life vehicles has emerged as a separate and quite significant movement in Europe, involving many small companies and giving a second life to many thousands of EV/PHEV batteries.

A very important element of a realistic assessment of the potential for storing RES energy in batteries, in virtually any LIB-based BESS (both BESS and BEV), is the correct assessment of battery degradation over time. As some studies (8) indicate, the real assessment of LIB service life may vary by as much as 37% (from 15 to 9.7 years of use) if the system is not properly secured (e.g. power limitations to and from LIB, SOC management, temperature control). Contrary to appearances, the author's experience shows that batteries that have been in use for several years, provided that the above elements have been monitored, are less susceptible to damage than any LIB batteries in their first year of use. Also very important feature of BESS based on various LIB batteries is their charging and discharging efficiency, which can successfully maintain a round-trip efficiency of 80% [

8]. For used EV LIB batteries, an empirically confirmed value of 75-76.5% has been adopted (

Table 3), which is very favourable for storing energy from RES (2,4). The safety of BESS will probably become a key issue when the first explosions of LIB-based BESS batteries occur. Observing the BEV market, this is a legitimate concern. The easiest solution would be to recommend the use of LIB battery chemistry with the lowest susceptibility to thermal runaway (e.g. LFP chemistry), but in practice it is already clear that manufacturers of BESS energy storage systems are primarily guided by economics rather than safety of use. In their current solutions, they prefer to introduce many functional limitations to BESS usage rather than change the LIB chemistry in order to prevent the thermal runaway. The issue of thermal runaway in BEV’s and BESS is described in detail in [

9]. The basic principles of LIB’s thermal runaway prevention in this kind of batteries include preventing overheating (easier to achieve in domestic conditions than in a vehicle), protecting the casing from punctures (as above) and proper el. use (not exceeding charging voltages and currents). Concerns about the safety of such solutions have so far proved unfounded, as the author's own research shows that batteries from the automotive market are much better protected against both atmospheric influences (they are designed for outdoor use, unlike most domestic BESS) and, moreover, due to their large size (and weight), they are kept outside residential buildings, which increases their overall safety of use. The way, the BEV internal BMS is designed also means that they are usually automatically disconnected from the associated inverter much faster (any suspicious activity, including opening the housing) than in the case of stationary BESS. The author has examined some of these features in publication [

10]. Finally, the mass production of LIBs has already led to a situation where batteries manufactured in gigafactories for the automotive market set quality standards for the entire electricity storage market, almost always ranking among the most durable and efficient solutions. It is simply a shame to scrap (or recycle) these types of batteries today, as their utility (and market) value is significant. However, publication [

9] rightly points out that there is a lack of uniform testing and certification methods for both BEV and BESS batteries. As mentioned in its Directives eg. [

1], the EU even demands that in Europe

"Requirements for the end-of-life stage are necessary to address the environmental impact of batteries and, in particular, to support the creation of markets for battery recycling and for secondary raw materials from waste batteries”. The newer version of this directive [

1] even suggests the introduction of new EU rules which, anticipating that

“batteries for electric vehicles, as these batteries represent the market segment with the highest expected growth in the coming years’, should ‘establish specific sustainability requirements for rechargeable batteries with a capacity greater than 2 kWh...” As a result, the author hopes that calls for greater attention to be paid to what happens to LIB batteries, both in vehicles (safety tests and certificates) and as a result of their “withdrawal” from use, will only help to increase the safety of LIBs used in BEVs as BESSs in the future. Therefore, leaving aside for a moment the business models that would have to be developed for this type of product (e.g. issues of warranty or liability for the safety of using such a BESS based on batteries from BEVs), the author focused in this study on testing their usability for nZEB buildings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Author Posed Three Research Questions

Question 1. Will every used battery removed from a functioning EV be suitable for use as a BESS in a residential building, and what will its performance parameters be compared to a commercially available new BESS of similar capacity?

Question 2. What will be the total costs of converting a BEV battery to a usable BES set ? What will be the real payback time ? How will NPV be sensitive to the market valuation of electricity from RES?

Question 3: Are there any other factors, such as safety of use or environmental impact, when comparing these two solutions?

For question 1, the basic question regarding the economics of using BESS is what is the appropriate battery capacity (Emax) for a household and what will be the cost of acquisition and use? Also how easy or how difficult it will be to convert BEV battery to useful BESS ? Opinions are divided on this issue, and it all boils down to the question of what energy storage is supposed to be used for. If we assume (which is in the interest of the professional energy sector, not prosumers) that the main goal would be to reduce peak energy demand during the day, then, quoting the authors [

5], they have shown that storing 2 kWh in each household allows the peak demand of a residential area to be reduced by half on the distribution network. But this is a problem - and it is in the interest of the DSO, not the prosumer. Looking at the problem from the other side - that is, the prosumer’s - the author's own research (not yet published) indicates that Emax (maximum energy available from BESS) should be at least equal to the energy demand of a household from “one solar day to the next” (in summer, this can be assumed to be from dusk to morning/noon the following day), taking into account the actual availability of effective energy from BESS. Further research has shown that in the case of feeding a significant amount of energy back into the grid (PV oversizing), the Emax capacity should be selected so as to meet all electricity needs from the end of one solar day to the beginning of the next – in practice, even several dozen kWh. For the purposes of this article, Emin= 8 kWh was assumed, which is considered a reasonable minimum in the Polish PV industry for a household preparing DHW from electricity. And this capacity is significantly less than the smallest battery pack in a BEV, so there is great potential. For countries located further north in Europe [such as Sweden], 12 kWh is recommended (8). Question 2 Question 2 proposes the use of more precise (not SPBT, as it is not suitable as too ‘simple’ parameter) methods for assessing the degree of usability of such LIB-based storage systems over time.

The proper calculation must be a calculation that takes into account the cost of money, the level of actual use of LIB and the degree of degradation of the battery from BEV eg. NPV).

Question 3 - comes down to analysing the safety of using BESS in residential buildings (which is a separate, major issue requiring urgent legal regulation) and analysing the environmental impact of LIB battery residues from used vehicles. It is obvious that extending the ‘lifespan’ of batteries from BEVs by several or even a dozen years will prolong the problem, but will not solve it. Nevertheless, as can be seen in various areas of modern life, the ‘delay dividend’ can be a beneficial, locally effective factor in solving large-scale problems.

2.2. In the First Stage of the Experiment, a “plug-and-play BESS set” Was Purchased (Emax=22kWh) Consisting of 7 LIB Modules and a BMS Control Module Manufactured by Pylontech (BESS_1), Described in Detail in Table 1. Next, a Complete BEV battery Was Purchased, Removed from a Car Scrapped in 2012, with a Nominal Capacity of 24 kWh, and named DIY EVB_1

The BESS_1 kit turned out to be plug-and-play; when connected to the Goodwe inverter, it immediately started working and storing energy in one of the three available modes. With the second kit, we encountered a few problems. Firstly, a ‘CAN bridge’ had to be added to translate the signals from the BEV battery BMS into codes that could be understood by the PV controller, but this will be described later. After assembling it with the Goodwe ET10 kW PV Inverter, it turned out that this battery (see Photo 1) was practically unsuitable for comparative tests, as its available capacity was significantly lower and it also showed a loss of power. As a result of literature research and tests carried out by the author on dismantled cells (Fig. 2), it turned out that batteries of this type, based on hybrid chemistry (LiMn₂O₄ + NMC), proved to be an unstable solution on the automotive market and their production was discontinued in 2016. The DIY EVB_1 LIB battery showed signs of typical permanent damage for this model (in 4 modules), making it practically impossible to conduct tests because the battery heated up and was unable to store the amount of energy comparable to the new BESS_1. Following earlier work, where the replacement of individual cells gave good results [

2,

4,

10], the author replaced 4 modules of DIY EVB_1 battery, but still did not achieve comparable charging results for the entire set. In this case, it was decided to purchase a newer version of the battery (made year 2016) from the same manufacturer with a nominal capacity of 24 kWh, already built on the basis of new NMC chemistry, which, as measured, already proved to have 95% of the nominal capacity of 24 kWh available (i.e. approx. 22 kWh), and was named DIY EVB_2. As a result, the internal design differs significantly (although the external dimensions of the battery remain almost identical and the weight is similar, see

Table 1). Compared to BESS_1, which has software limitations on the use of its capacity (approx. 10% of its nominal capacity must remain in the battery, hence Emax=22kWh), two batteries were obtained which did not differ (significantly) in terms of available capacity, but differed (significantly) in terms of purchase price and home installation options (

Table 1). In the case of the first BESS_1, a model was chosen that can work with some five types of PV inverters, including the GoodWeET10kW used, practically on a plug-and-play basis. Connecting the DIY EVB_2 kit to the second GoodWeET10kW inverter required, as mentioned, the installation of a special interface, called a CAN bridge, which would safely translate the battery's BES commands and the PV inverter's commands in both directions. In this case, the author made the interface using LillyGO T-CAN 485 ESP interface hardware, using documentation available in the internet [

7]. This resulted in a universal CAN bridge interface that allows for connecting many different types of BEVs in the future (in particular DIY EVB_ 1 and 2, which have identical protocols) with hybrid solar inverters (like eg. GoodWe ET series). The test bed was almost identical to this used in [

11], but using different LIB, PV Inverter, and interface

2.3. The Purchase Costs of Individual Sets Are Shown in Table 1, But at This Stage It Can Already Be Concluded That Despite Almost Identical Purchase and Connection Costs to PV Inverters (GoodWe ET Series), the Set and DIY EVB_2 Should not Be Compared Because Their Usefulness Is Fundamentally Different (DIY EVB_1 negligible). As a Result, NPV and Sensitivity to Market Electricity Prices Were Simulated, as Described in the Discussion Section. The Answer to the Third Research Question Is Described in the Last Section of the Article, Entitled Conclusions

Figure 1.

Used battery 6 module set DIY EV 24_1), some cells are swallowed (left corner), before module replacement.

Figure 1.

Used battery 6 module set DIY EV 24_1), some cells are swallowed (left corner), before module replacement.

Figure 2.

Replacement cell module (not original).

Figure 2.

Replacement cell module (not original).

Figure 3.

BESS-NEW Pylontech H1 (Pylontech 24 kWh H1 set).

Figure 3.

BESS-NEW Pylontech H1 (Pylontech 24 kWh H1 set).

Figure 4.

Pylontech 24 kWh H1 module.

Figure 4.

Pylontech 24 kWh H1 module.

Table 2.

Description of 3 battery set tested in the research.

Table 2.

Description of 3 battery set tested in the research.

| |

BESS 1 |

Nominal

Capacity (kWh)

|

Initial Cost (Euro) |

Set Description |

| 1. |

BESS-NEW Pylontech H1 |

24,8 |

8000-12000 1 |

Set of BES module, rack, 7 battery modules, cables

|

2. |

DIY EV 24_1 |

24 |

2500 2

|

Set of EV battery incl. BMS, modules replacement,

CAN BYD HVM emulator, cables |

3. |

DIY EV 24_1 |

24 |

2500 |

Set of EV battery incl. BMS,, CAN BYD HVM emulator, cables |

Table 3.

Description of NPV values adopted for scenarios 1,2 in the research.

Table 3.

Description of NPV values adopted for scenarios 1,2 in the research.

| |

Parameter |

NPV1 |

NPV2 |

Set Description |

| 1. |

Daily Energy Used |

8kWh |

8kWh |

24 hours energy stored and used from BESS |

2. |

Efficiency (η) |

0,765 |

0,765 |

Charging (0,95) – discharging (0,8) efficiency |

3. |

Annual degradation (d) |

4% |

4% |

Estimated battery capacity degradation (capacity)

|

4. |

Annual maintenance (M) |

100 € |

100 € |

Annual cost of maintenance (test and care) |

5. |

Discount Rate (r) |

5.35% |

5.35% |

Current discount rate in Poland |

6. |

Lifetime (N) |

7 |

7 |

Based on new BESS guarantee time and expected life time of BEV BESS |

7. |

Initial Cost (€) |

2,5k€ |

8-12k€ |

Calculation of DIY BESS based on used BEV battery compared to new BESS |

3. Results

From a technical point of view, it must be concluded that the DIY EV 24_1 kit was a poor solution. After replacing four modules of BEV LIB, after conducting numerous charging and discharging cycles to balance the entire battery, final tests - the result was that the DIY EV 24_1 battery could be charged to 75% (initially to about 60%). However, the biggest problem was the uncertainty of its future performance as a BESS, as the tests indicated an SOH of approx. 70-80% and significant unevenness in the resistance of individual cells (using methodology described in [

2]), determined using the methodology developed in [

2] using EIS. In this case, there is no rationally justified reason why this battery will be able to operate for another 6-7 years without the need to replace further battery modules. Therefore, there is no technical justification for recommending such a solution for the future. At this point, however, it should be noted that it is not generally valid that EV batteries with a specific date are no longer suitable for regeneration. As part of the aforementioned research project [

3], it was possible to regenerate even older PSA hybrid car batteries to an SOH of 85%, but in that case, due to the significantly lower capacity of the hybrid car battery (e.g. 1 kWh), this was possible. From a technical point of view, only the

DIY EV 24_2 and

BESS_1 versions can be considered in this experiment, as they were selected so that their available capacities are similar and their variable costs are similar in the assumed analysis period. In the case of maintenance, periodic inspections are required for safety reasons – either by an authorised service centre or by the company that supplies the DIY BESS. As part of the monitoring, it is assumed that this type of BESS should be remotely managed by the supplier (in Polish conditions, this is estimated at approximately €200 per year). The only significant differences are their purchase cost (

Table 1) and possible location –

DIY EV 24_2 under a roof outside the building and

BESS_1 inside the building

.

3.1. The Results Obtained During the Calculations are of an Economic Rather than Technical Nature, as it can Be Technically Assumed That both Structures Will Have Similar Performance Characteristics During the Period Under Consideration (7 years)

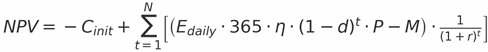

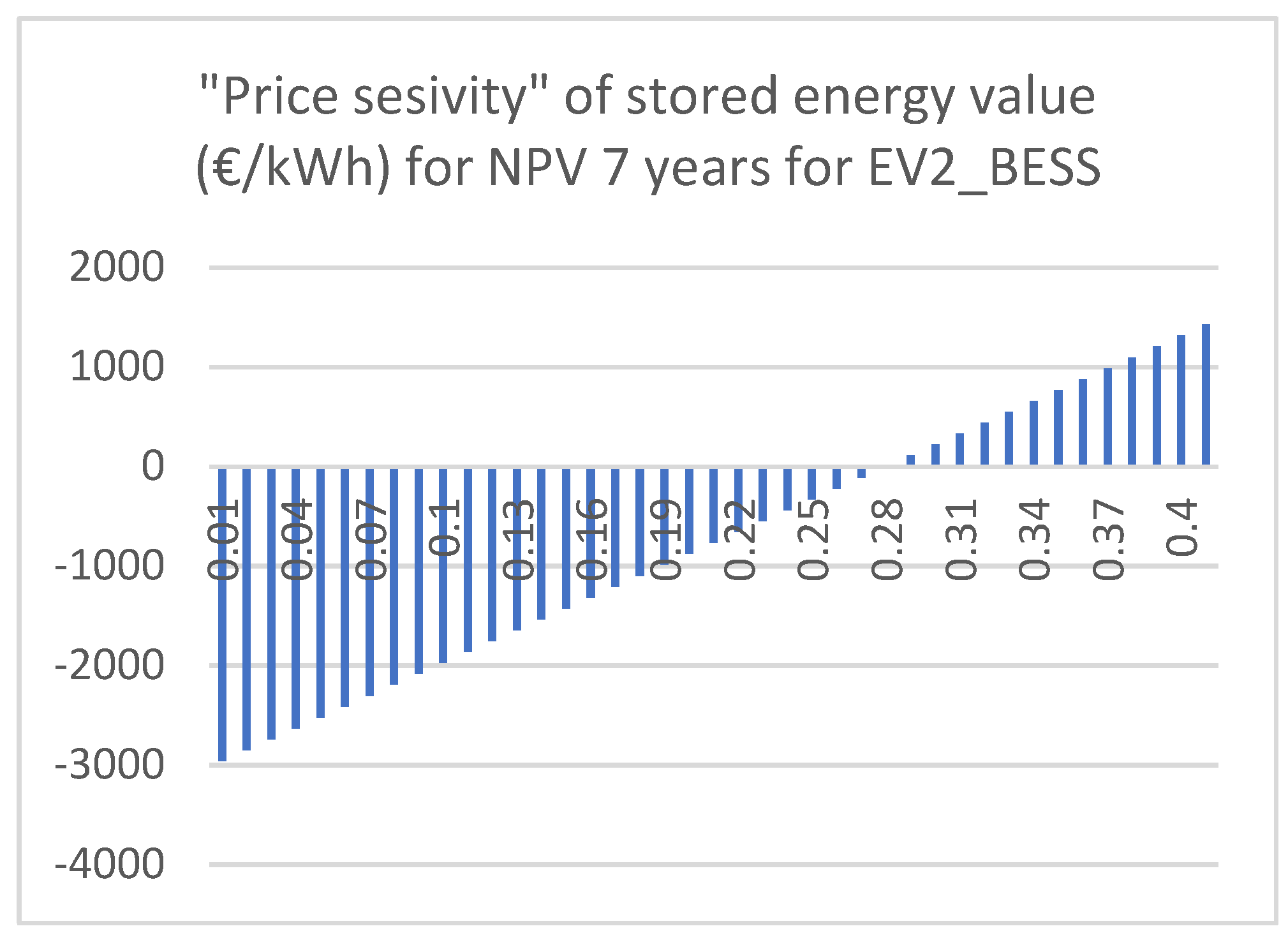

Net Present Value calculations for investments in BESS_1 or DIY EV 24_2A typical NPV formula modified by the annual degradation factor and the price difference P should be used:

Where:

Cinit= Initil cost of BESS ( 2,500 €)

Edaily = Daily energy consumed by household (8 kWh)

η – Efficiency ( 0,765)

d – degradation annually (4%)

r- discount rate (in Poland 5,35%),

N – lifetime (expected BESS lifetime, let’s consider 5,7,9,11 Years), t - year

P – tariff difference (“avoided cost”* in € per kWh)

M – Cost o Maintenance (yearly in €)

The factor ‘P’ in formula [

1] requires clarification and expansion. If „P” is equal to the current energy purchase tariff from the sales operator, then the standard NPV will indicate after what time, when charging energy from PV during the day and using it after sunset, the investment (Cinit) in BESS (with assumed efficiency, purchase and maintenance costs and degradation) will pay for itself. A comparison with the expected lifetime of the set will answer whether, by purchasing such a set for the price of Cinit, we will obtain some funds (additional NPV value) after period N or whether we will lose them (negative NPV values) for a given purchase price.

If we extend this line of thinking and P is the difference between the current purchase price of energy and the marginal cost of energy from PV (which in the case of 100% sponsored roof-top PV installations can be assumed to be zero), the result will be similar. Of course, if the PV system was purchased specifically for the purpose of increasing energy self-consumption as an alternative to grid energy, its cost should be added to Cinit, and its other costs should be included in the calculation (in the case of the 2015 test PV installation, its purchase cost was fully amortised and an approximation can be assumed the cost of the PV installation does not affect the economics of the BESS. However, if in another country there is a possibility of price arbitrage for prosumers, and they can purchase energy at zero prices during one day and resell it to the grid at maximum prices during that day, then the value of P will determine the value of the energy difference obtained. In Poland, if such a possibility arose, the value of the ‘storage’ energy between periods of negative prices (until noon) and evening price peaks would be (without additional costs) approximately 250 Euro per 1 MWh (approximately 0.25 E per 1 kWh), and the latest sensitivity analysis in Fig. 9 was performed for these values.

Where:

Pd – tariff difference (in € per kWh)

Cepp – Current energy purchase price ie. the total cost (in € per kWh) delivered to household

Cerv - Current energy returned to grid (value ) – ie. Value (in € per kWh) injected to grid by household. Eg

Pd = 0,23 – 0,032 = 0,198 € per kWh (in Poland)

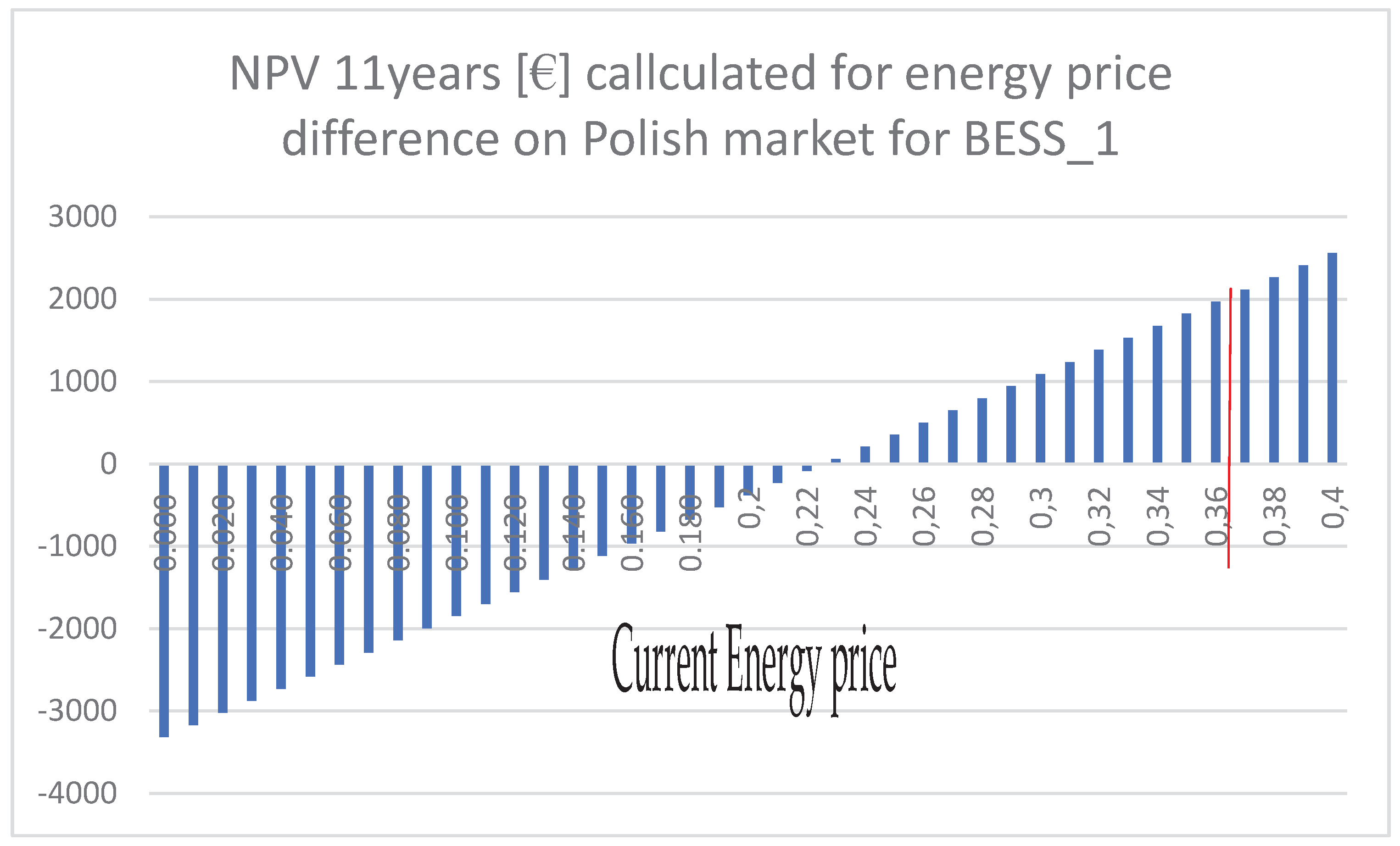

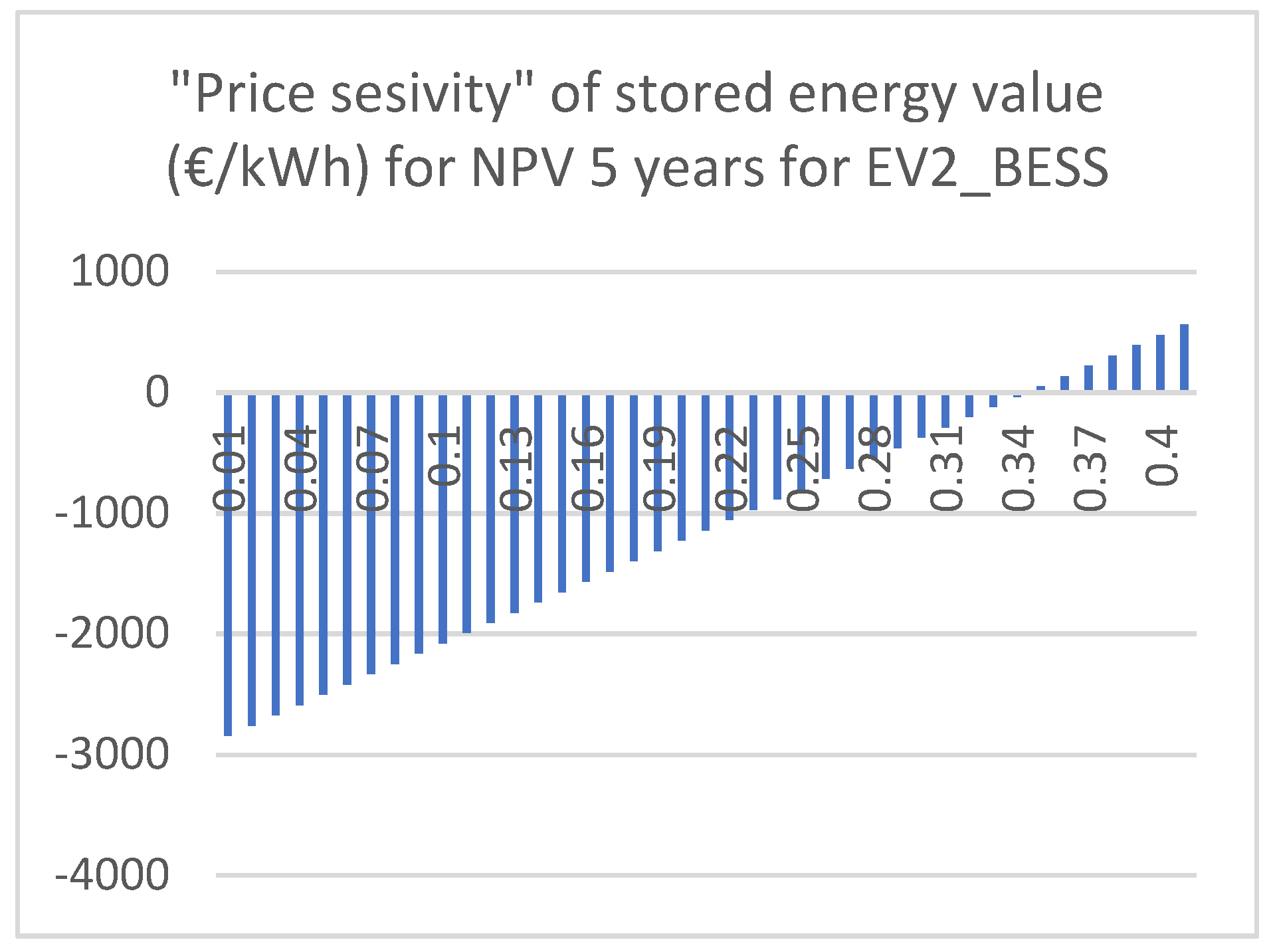

3.2. Price Sensitivity Simulation Results

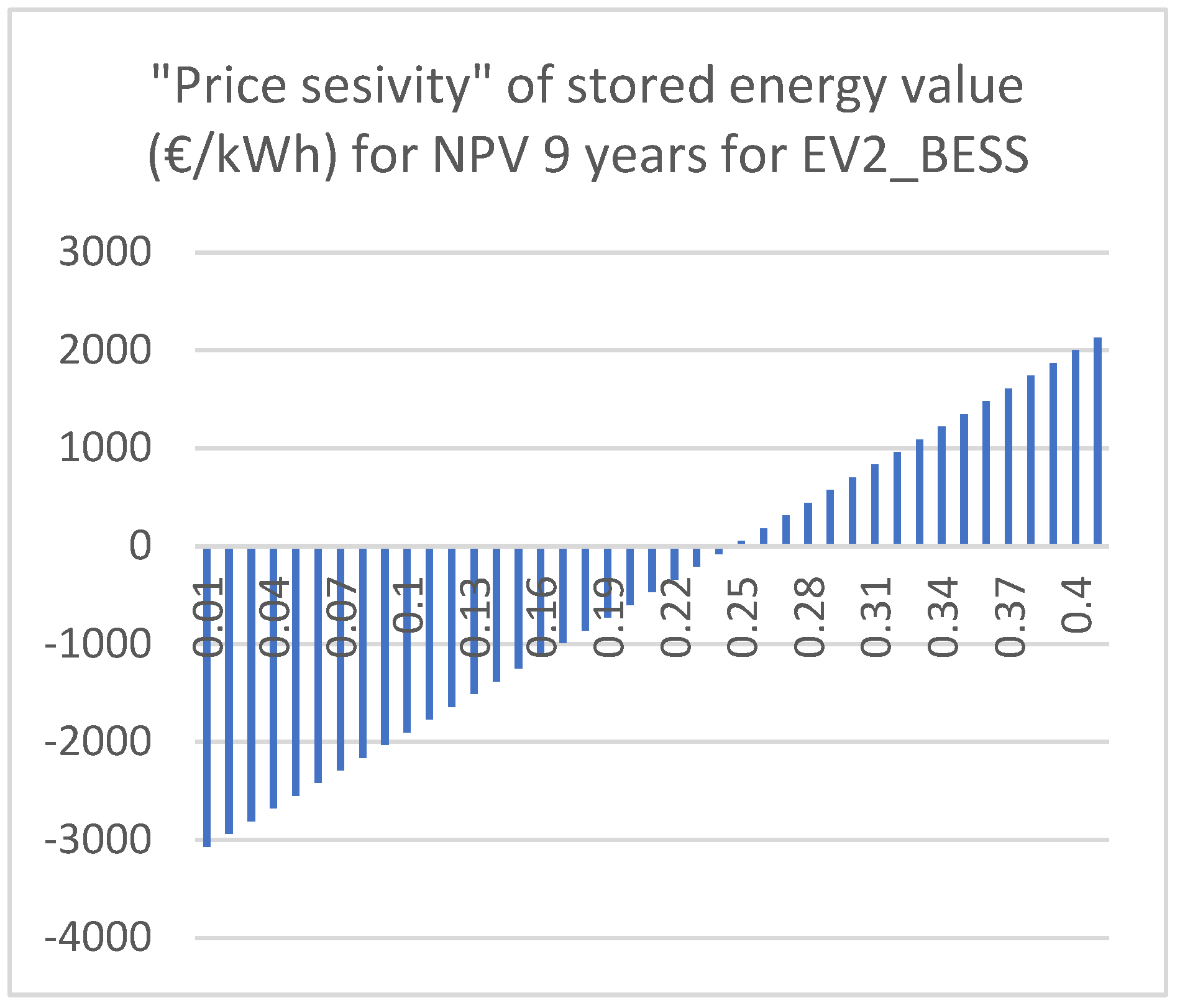

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the results of calculations for the

DIY EV 24_2 set for service lifespans of 5 and 7 years, respectively. They show that the grid energy price of €0.34/kWh for 5 years and €0.28 for 7 years would NOT justify such an investment. It is worth noting that the current purchase price of energy from the sales operator [price P for formula (1)] is 0.23 €/kWh. As a result, it can be concluded that BESS devices with the parameters described in

Table 1 will not bring any added value if their service life is shorter than 7 years.

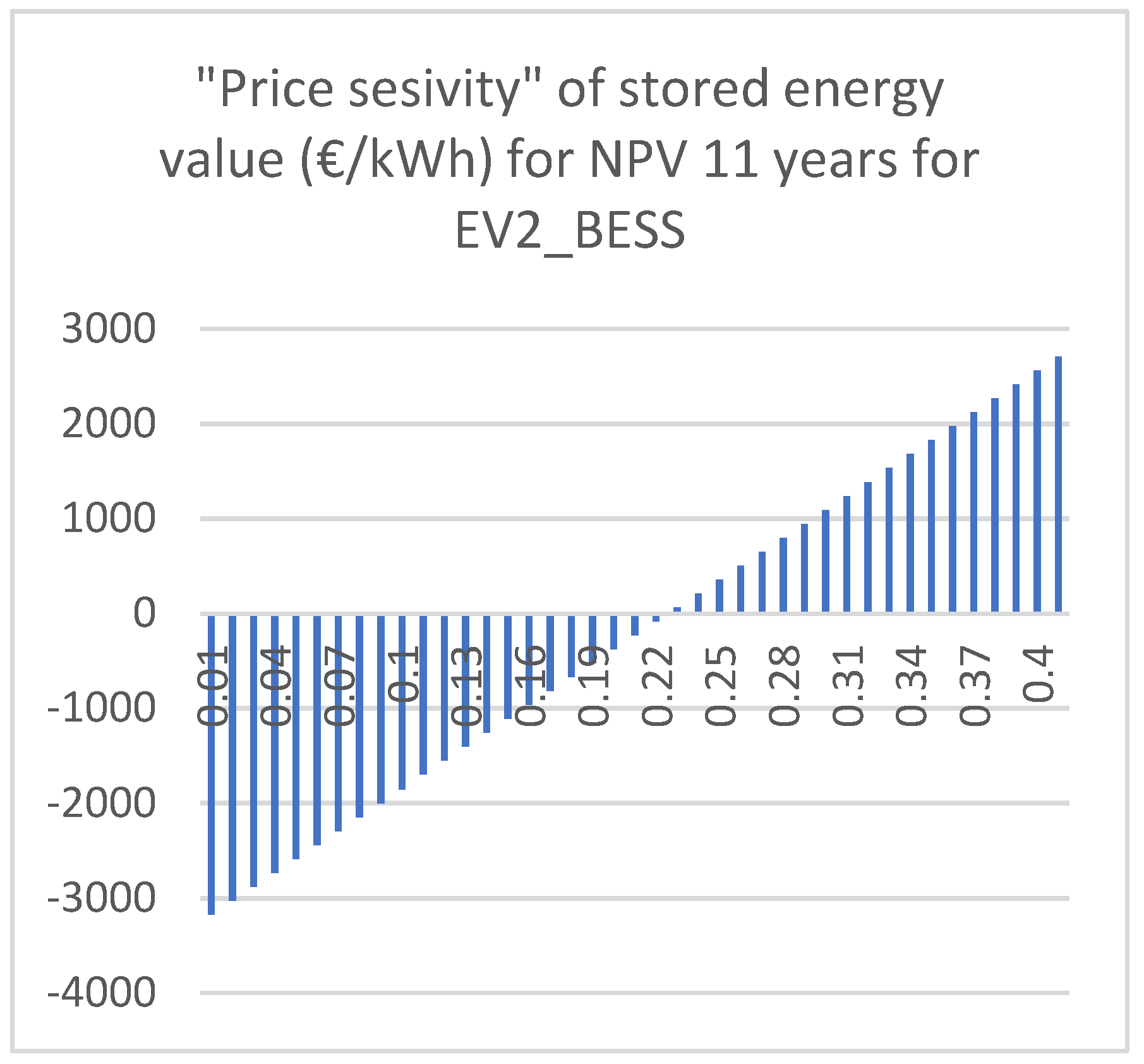

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the results of calculations for the

DIY EV 24_2 set for service lifespans of 9 and 11 years, respectively. They show that a grid energy price of €0.25/kWh for 9 years and €0.22 for 11 years would justify such an investment. It is worth recalling that the current purchase price of energy from the DSO from the grid [price P for formula (1)] is €0.23/kWh and is likely to increase in 9-11 years. As a result, it can be concluded that with current energy prices in Poland, only BESS devices based on used batteries from BEVs, with the parameters described in

Table 1, which will operate for at least 9 years, will constitute a justified investment. Otherwise (i.e. if they lose the ability to deliver at least 8 kWh per day or their operating costs increase by more than €200 per year), they will be a bad investment, as their cost will exceed the expected revenue.

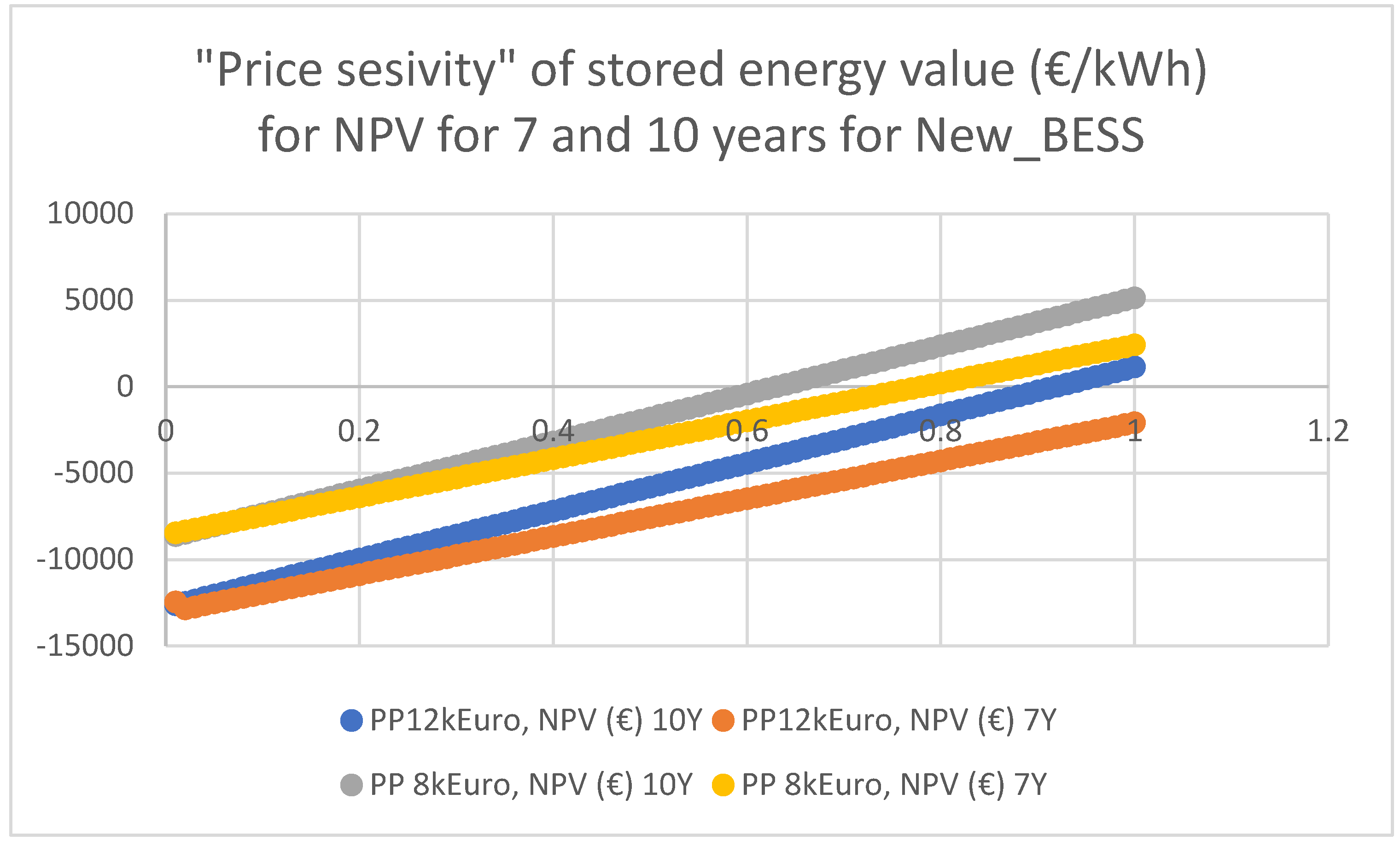

The graphs in

Figure 10 show the results of calculations for the

Bess_1 set for service lifespans of 5 and 7 years, respectively. They show that a grid energy price of €0.34/kWh for 5 years and €0.28 for 7 years would NOT justify such an investment. It is worth recalling that the current purchase price of energy from the grid trading company [price P for formula (1)] is €0.23/kWh.

with Cinit =8000€ and Cinit =10.000€

Similar to DIY EV24_2, an NPV sensitivity analysis was performed for the new BESS device – Pylontech H1 24 kWh at the current market energy price of 0.23 €/kWh. Depending on the method of purchase and delivery, its price (Cinit) in Poland ranges from €12,000, which does not allow for amortisation before the price reaches €1/kWh. At a purchase price of up to €8,000 (yellow graphs: €0.8/kWh with 7-year amortisation and grey graphs: €0.6/kWh with 10-year amortisation). The study was repeated until the current energy price in Poland was reached in the next section 3.3.

Figure 11.

Pylontech 24 kWh H1 module for price difference “Pd”.

Figure 11.

Pylontech 24 kWh H1 module for price difference “Pd”.

4. Discussion

The results obtained should give pause for thought regarding the profitability of investing in BESS, both as a stand-alone home device and as a BESS based on batteries from BEVs.

4.1 Firstly, it should be noted that the two LIB chemistry technologies used by the car manufacturer divide potential applications into ‘old batteries’ (such as DIY EVB_1) and ‘new batteries’ (DIY EVB_2), which, although they come from the same car model (from different years of production), differ fundamentally. As tests have shown, ‘old batteries’ are widely available today and their price is very attractive. However, due to the unstable chemical composition of the cells, they should not be used for home BESS, as they cannot be practically regenerated (no new spare parts are available). The modules available for this battery come from used batteries, so they can only slightly improve the performance of this type of battery. On the other hand, the type B battery is ideal for use in BESS, as confirmed by the experiment described above. The degradation of this battery at a rate of 4% per year will probably allow it to be used for about 12-18 years, and the NPV level of 11 years assumed in the calculations can be considered safe and economically justified. The above data is also confirmed by battery tests in vehicles that are still in use, as confirmed by service points for these cars in Poland. This part of the study leads to the first general observation that the automotive market itself is learning how to optimally select battery compositions for vehicles, and that the assumption that a battery from car XY can be used may prove to be very wrong, as suppliers are reluctant to share their R&D progress and do not want to facilitate a ‘second life outside their vehicles’ for batteries.

4.2 The second key issue concerns the adopted model for pricing energy from storage and its impact on the profitability of purchasing batteries from BEVs as BESS. Literature sources discuss various solutions for the optimal model of cooperation with DSOs, and the energy storage process can be either very profitable or completely unprofitable from the point of view of the prosumer and their personal investment economics. This is shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and 10-11. by conducting an NPV sensitivity analysis in relation to energy pricing. With an average investment in BES of around 2,500 to even 12,000 EUR for 24 kWh BESS and prices below 0.23 EUR/kWh, from the prosumer's point of view, there is no justification for this. Most experts in Poland agree that investing in a small (5-10 kWh) prosumer BESS is a very good gift for the DSO, but there is no practical business justification for the prosumer – and it is the DSO that should be interested in giving it to the prosumer for free, not the other way around.

4.2 The third key factor in the discussion on the benefits of batteries from BEVs as BESS should be the warranty period and its scope in the case of BESS. For new BESS, there are several ‘warranty schemes’ on the market that are not compatible with each other. The most common is a time warranty (e.g. 7 years for Pylontech 24kWh), which guarantees a minimum performance of 70% of capacity (but without guaranteeing the power level). Another is a cycle count warranty (e.g. 5,000), and yet another is the most convincing warranty of energy quantity (e.g. 16.5 MWh) to be obtained from the storage system before it undergoes significant 30-40% degradation. Only the latter (if complied with) can be used for reliable economic calculations. In the case of used EV batteries used as BESS, there can of course be no guarantee, which is why only the remaining life can be estimated. These estimates can be based on market research on the degree of battery wear of individual car models in different years based on market offers. The author used this method, being aware that this result should be verified and is only an assumption at this stage of the experiment. Using this method, the author concludes that older batteries in some EV models are not suitable for further use at all, as they were designed for the duration of the car's warranty (e.g. 6 years) and today are nothing more than scrap that is difficult to dispose of.

4.3 Final calculation for energy prices on the Polish market. The lack of reliable calculations of the profitability of purchasing new or used BESS on the Polish market results in purchasing decisions by prosumers. Companies selling new BESS often do not take into account the basic limitations of LIB battery technology, as well as the real energy prices on a given market. In Poland, the current price of surplus energy from new PV installations sold to the grid (old installations use the net-metering system) is 0.032 €/kWh, while the cost of purchasing energy from the grid is 0.23 €/kWh (difference=0,198€). With the parameters specified in

Table 3, even assuming a very optimistic scenario of 11 years of use of a BESS made of BEV batteries with a nominal capacity of 25 kWh, with an average use of only 8kWh per day, the NPV sensitivity analysis with respect to price shows that even the purchase of a BESS for EUR 2,500 has no chance of paying for itself during the battery's lifetime, as shown in Fig. 10. A positive NPV would be obtained if, according to formula (2), the operator's energy repurchase price were EUR 0.22 instead of the current EUR 0.032. The current difference (0.198 €) creates added value when energy is fed back into the grid, because even a BESS at ¼ of the purchase price of a new one would have no chance of recouping the investment during its expected lifetime, as can be seen directly from the analysis in Fig. 10-11.

5. Conclusions

1. Battery packs from BEV, with the addition of small interfaces, can be an interesting price alternative to BESS kits available on the market as ‘ready-made’ solutions. They can offer significantly higher capacities at a lower purchase price, offering a much shorter payback time than ready-made home BESS kits.

2. The popularity of BEVs and the statistical withdrawal of vehicles from circulation is a natural source of supply for batteries (as with any used parts that still have some useful value) to the secondary market, which encourages independent companies to create a market for their repair and introduction into the circular economy, as specifically recommended in EU Directive 2023/1542 [

3].

3. Due to the dynamic progress in the solutions used in automotive batteries, even traction batteries from the same type of car but with different years of manufacture can be either a very useful or completely useless source of BESS for domestic applications, depending on the chemistry used in their production. However, for marketing reasons, this data is not published by car manufacturers.

4. Serious advantages of BEV battery packs over domestic BESS include:

their significantly wider operating temperature range, which means that even without the use of heating or cooling systems, they can be very attractive as BESS located outside residential buildings (safety considerations) their sealed construction, resistance to environmental factors and flame-retardant housing

b. Their significantly higher capacity in relation to the domestic BESS sets on offer

c. Their several times lower purchase price, especially in relation to 1 EUR/1 kWh

d. An important technical advantage is the fact that BEV batteries have been designed to operate with significantly higher currents in vehicles, so operating in a building power supply regime with a power of only a few kW is completely unburdensome for them, and thus batteries with very poor performance in cars can perform very well when used as BESS, and their service life may be longer in the home than in a vehicle

e. Compared to BESS, two major drawbacks can be identified: the lack of a manufacturer's warranty, and unfavourable dimensions and significant weight.

f. An important technical advantage is the fact that BEV batteries are designed to operate with much higher currents in vehicles, so operating in a building power supply regime with a power of only a few kW is completely unburdensome for them, and thus batteries with very poor performance in cars can perform very well when used as BESS, and their service life may be longer at home than in a vehicle.

g. The lack of plug-and-play capability and the need to use a CAN bridge (or other interfaces) is not considered a drawback by the author, as their description is widely (and freely) available online from BEV battery specialists.

6. The attractiveness of BESS in a given market is related to the current price of electricity – both that purchased from the professional energy sector and that from RES fed into the grid by prosumers. The research conducted has shown that if the price of energy on a given market is too low, professional, ready-made BESS kits will simply be too expensive in relation to the value of the stored energy, and as a result, the energy storage market will not develop. Calculations indicate that if prosumer energy arbitrage could be introduced on a widespread basis in a given country, the payback period for all BESS could be practically guaranteed by massive prosumer operations on the energy market, cutting negative prices and shifting supply to the period of maximum demand in the evening for a fee.

Acknowledgments

Author deliberately does not specify the exact models of cars from which BEV batteries suitable for further use could be obtained, in particular the models from which the EV1 and EV2 batteries were obtained, although for specialists in this field, their source is obvious from the photos provided. The reason for this is concern about the potential legal consequences (claims) that this article could cause in the event of dissatisfied owners of these car models, who could conclude from this text that the BEV manufacturer has released (in year 2012) an EV battery model that was in definite need of improvement.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EV/ BEV |

Electric vehicle |

| BESS |

Battery Energy Storage System |

RES

SOH |

Renewable Energy Sources |

LIB

PHEV

EIS |

State of Health – parameter describing battery wear out level

Lithium- Ion battery

Plug-in Electriv Vehicle, a Vehicle with ICE enegine and electric engine, with set of batteires to be used for tracking

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

|

Appendix A

Answers to the Research questions

Q1 = 1. Will every used battery removed from a functioning EV be suitable for use as a BESS in a residential building, and what will its performance parameters be compared to a commercially available new BESS?

In light of the experiments conducted, the first research question can be answered with a resounding YES – it is possible and both technically and economically feasible. However, it is not easy to implement and, until specialist companies offering such retrofitting services are established, it may be difficult to carry out for people who do not deal with batteries and ICT solutins (like CAN interface) on a daily basis.

Q2 2. What will be the costs of converting a BEV battery to a BESS battery? And what will be the real payback period (not SPBT). How will NPV be sensitive to the market valuation of electricity from RES?

The total cost of a BESS based on batteries from a BEV can be 3-4 times lower than purchasing a new BESS, but it can provide a storage system with significantly better parameters (e.g. capacity) and offering a faster return on investment - even taking into account current electricity prices in some countries. NPV strongly dempend on real value of stored electricity.

Q3: Are there any other factors, such as safety of use or environmental impact, when comparing these two solutions?

There are other factors, such as safety and environmental impact, which will work in favour of BESS solutions based on BEVs. In terms of safety, the fact that BESS must be located outside the home, perhaps in a separate fire zone, may increase the safety of such storage facilities. From an environmental point of view, the reuse of batteries from BEVs, (which could potentially pose a threat to the environment), is an idea worth considering, and at least EU directives already strongly recommend member states to work in this directin.

References

- Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 July 2023 concerning batteries and waste batteries, amending Directive 2008/98/EC and Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and repealing Directive 2006/66/EC https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R1542.

- Piotr Maćków, Piotr Guzdek, Wojciech Grzesiak , “Some procedures for recycling partly used traction batteries from electric vehicles“ (org. “Wybrane procedury procesu recyklingu częściowo wyeksploatowanych baterii trakcyjnych pojazdów elektrycznych” ) February 2022 PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY 1(2):142-145, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Sangwongwanich, A., Zurmühlen , S., Angenendt, G., Yang, Y., Séra, D., Sauer, D. U., & Blåbjerg, F. (2018). Reliability Assessment of PV Inverters with Battery Systems Considering PV Self-Consumption and Battery Sizing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE 2018) (pp. 7284-7291). IEEE Press. IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition Vol. 2018.

- Rafał Krzystof, Jacek A. Biskupski, Patryk Chaja, Marcin Kuźmński „Budowa hybrydowych magazynów energii - aspekty techniczne i bezpieczeństwo”. [CrossRef]

- Pietro Elia Campana, Luca Cioccolanti, Baptiste François, Jakub Jurasz, Yang Zhang, Maria Varini, Bengt String, Jinyue Yan “ Li-ion batteries for peak shaving, price arbitrage, and photovoltaic self-consumption in commercial buildings: A Monte Carlo Analysis”, Energy Conversion and Management 234 (2021) 113889.

- Sahar Safarian “Environmental and energy impacts of battery electric and conventional vehicles: A study in Sweden under recycling scenarios”, Fuel Communication Vol. 14, March 2023, 100083.

- Daniel Oster, “The Leaf LIB battery as BESS research” a crowfunding for CAN bridge research. https://github.com/dalathegreat/Battery-Emulator , Access 2024.03.10.

- Assia Chadly, Elie Azar, Maher Maalouf, Ahmad Mayyas “Techno-economic analysis of energy storage systems using reversible fuel cells and rechargeable batteries in green buildings”, Energy, Volume 247 2022, 123466.

- Yuqing Chen, Yuqiong Kang , Yun Zhao et all “A review of lithium-ion battery safety concerns: The issues, strategies, and testing standards”.

- Piotr Maćków, Piotr Guzdek, Jacek A. Biskupski, Wojciech Grzesiak “Innovative energy storage facilties integrated with monitoring and surveillance functions. Selected issues”. Oryg .Title: “ Innowacyjne magazyny energii wyposażone w funkcję monitorowania i nadzoru. Wybrane zagadnienia. Journal „Przeglad Elektrotechniczny”, 9/1, 2022.

- Reschiglian, Tommaso; Sevdari, Kristian; Marinelli, Mattia “Repurposing Second Life EV Battery for Stationary Energy Storage Applications” Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C.D.; Author 3, E.F. Title of Presentation. In Proceedings of the “Proceedings of 2024 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE), Denmark. [CrossRef]

- Andrew J. Pimm a, Tim T. Cockerilla, Peter G. Taylor ”The potential for peak shaving on low voltage distribution networks using electricity storage” Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 16, April 2018, Pages 231-242 . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).