I. Introduction

As the world transitions to more sustainable energy sources, solar photovoltaic (PV) is a key driver in meeting the increasing demand for electricity. Photovoltaic energy is considered one of the main supporting technologies to address climate change globally and to achieve carbon neutrality due to its broad distribution, low carbon emissions, and low development and operational costs [

1]. Furthermore, in the context of national policies such as the "Belt and Road" initiative and new energy base planning, the strategic importance of solar energy continues to grow. Within this context, being able to accurately identify areas with adequate sunlight resources and potential for development has formed the basis for optimizing energy layout globally, balancing and dispatching the load on power grids, and investment decision-making for new energy developers.

Accurate identification and assessment of regions with high PV potential is an important prerequisite for enhancing PV deployment efficiency, optimizing grid dispatch, and ensuring energy security [

2]. While the assessment of regional PV potential involves solar irradiation resources, it also has to consider, more comprehensively, and in multiple dimensions, other variables such as temperature, terrain slope, land cover type, access cost and environmental protection to effectively provide the quantified potential of PV.

Assessment methodologies traditionally rely on quantitative GIS related methods or energy based models where the physical fundamental solar radiation and energy balance or production can be interpreted for readers. However, these traditional assessment methodologies are often limited by their ability to model complex nonlinear relationships in the face of large scale and multi-source of heterogeneous datasets [

3]. In addition, the traditional assessment methodologies ignore the interaction coupling of the topography, meteorology and utilization mode components of PV when applied within an assessment across multiple scales of climate regions which only exacerbates prediction bias which adversely effects the accuracy of their use in policy implementation and investment [

4].

Conventional photovoltaic (PV) potential evaluation is predominantly dependent on physical models and regression approaches. Although these approaches are driven by meteorological factors, such as irradiation or temperature, the consideration of the interactions within disparate geographic environments and land use types is nearly impossible and their non-linearity and heterogeneity generally result in poor prediction accuracy. For example, the classical PVGIS model or the HelioClim modeling framework focuses primarily on the irradiation transfer and energy conversion mechanism of a single factor, disregarding the geographical constraints of the albedo effect and atmospheric consequence of an altitude change and the land feasibility [

5]. Our understanding of the linear regression or stepwise regression can identify predictors to use, early-stage modeling, but ultimately suffers under conditions of high-dimensional features or collinearity of input variables leading to misjudgment of actual operation.

III. Methodologies

A. Multi-Factor Deep Residual Network

In order to accurately model the multi-factor characteristics of PV potential areas, we first construct a multi-branch input coding module to process topographical, meteorological and land use data from different modalities. Each factor is mapped as an independent high-dimensional eigentensor to preserve its heterogeneity and independent distribution characteristics, as shown in Equation 1:

In the above equation, denotes the -th input factor (e.g., solar radiation, temperature, etc.) and its dimension is . The encoding function is a sub-network of convolutional layers, BatchNorm, and ReLU with a parameter of . The output represents the embedded representation of the factor in the feature space.

The multi-branch input coding module receives a total of N external factors (terrain DEM, elevation slope, vegetation index NDVI, annual average solar radiation, etc.). Each factor is fed separately into a lightweight convolutional encoder to ensure that heterogeneous data is handled exclusively for feature fidelity and noise suppression at an early stage. The encoder architecture is consistent: both use two layers of Conv (3×3, C/4) → BN → ReLU → Conv (3×3, C/2) → BN → ReLU; The size of the convolution kernel is unified with the number of layers, which can control the variables and avoid the interference of structural differences on the subsequent fusion effect.

In order to uniformly process all factors in the subsequent network, we stitch all the encoded features into a multimodal joint eigentens, such as Equation 2, in the channel dimension:

Among them, Represents the splicing operation in the direction of the channel, is the number of factors, . The result of the splicing is a joint semantic representation of different factors in the whole region, providing a structured input for the residual fusion layer.

Subsequently, we introduce a hierarchical residual fusion structure on the basis of ResNet to fully capture the deep interaction and maintain gradient stability. Each residual block not only performs homogeneous feature enhancement, but also fuses coupling information between multiple factors, as shown in Equation 3:

The above formula defines the rules for updating the residuals at level represents the residual path composed of convolution dimensionality reduction, convolution extraction, and RelU nonlinear activation. is the dynamic gating coefficient, which is used to balance the output of the current layer with the residual direct connection path.

This gating parameter is learned adaptively by the following formula, as shown in Equation 4:

where

is a Sigmoid function and

represents averaging all spatial positions to form a channel attention vector.

is the gated linear transformation weight, which is used to determine whether the current layer feature has sufficient representation power to "open" the residual path.

B. Global-Local Attention Mechanisms

In order to further improve the model's perception of spatial context and temporal dynamic features, we designed a global-local attention mechanism in the final stage to dynamically reweight the importance of spatial position. First, the global context representation of the entire graph is calculated, which is used to guide local attention, as shown in Equation 5:

where

is the output of the last layer of residual blocks, and

is the number of channels. The average pooling operation extracts the overall semantic distribution of the image as a global reference vector.

Then, the attention calculation is performed on the features on each spatial position

, and its local features and global context information are fused, as shown in Equation 6:

where

denotes the vector splicing operation,

are the weight matrices used to learn spatial-semantic relations, and

is the Sigmoid activation function that generates the attention mask

.

Finally, the local features are multiplied by the corresponding attention weights to obtain a spatially weighted representation, as shown in Equation 7:

where the

represents element-by-element multiplication operation, which realizes the feature enhancement of significant regions and the suppression of secondary regions, and optimizes the spatial distribution accuracy of the predicted representation.

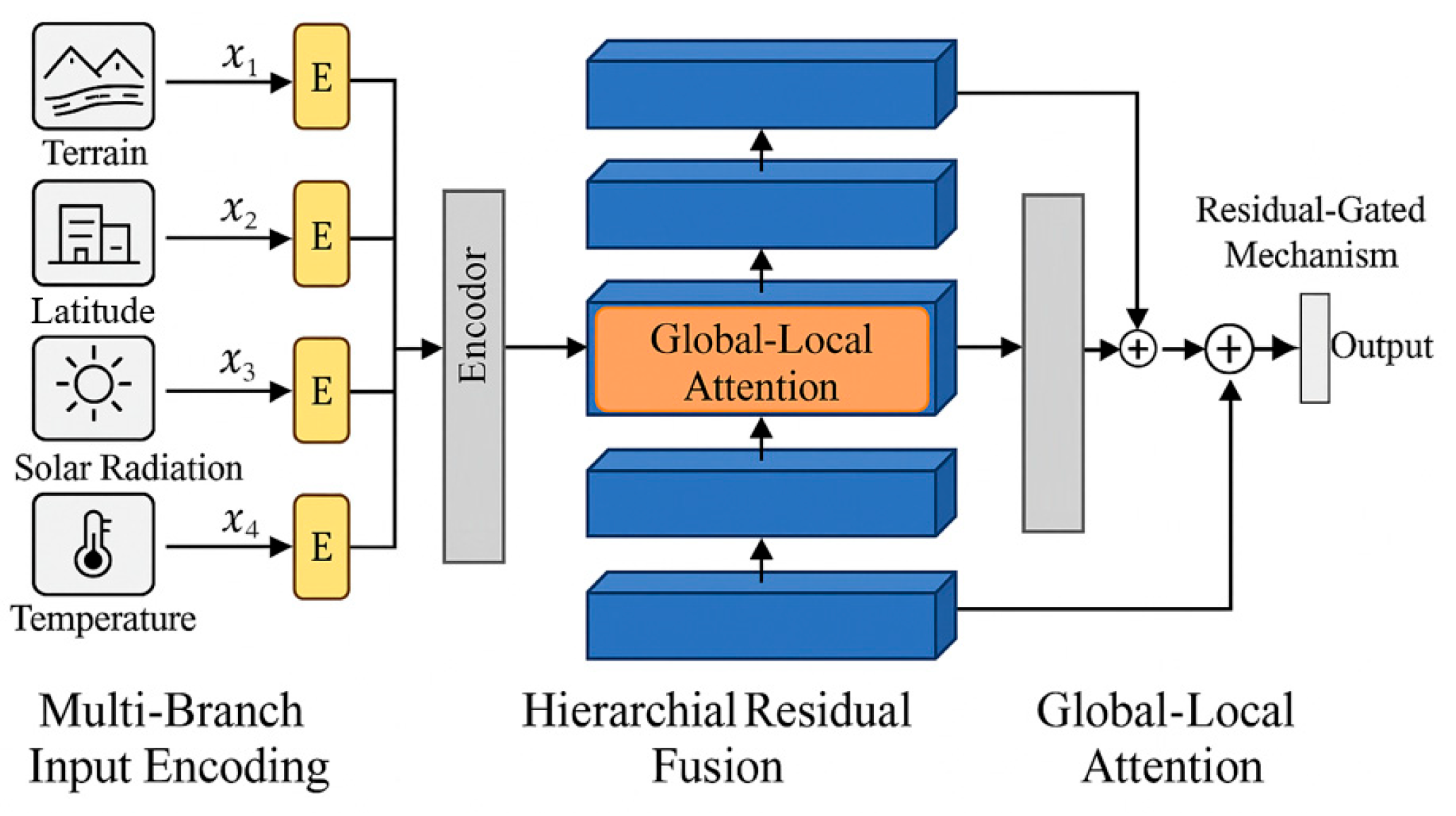

The overall structure of the framework for precise photovoltaic ability prediction is shown in

Figure 1. The framework introduces a multi-branch input encoding module, where heterogeneous environmental and geospatial features (e.g., terrain, latitude, solar radiation, temperature) are operated on individually using a set of encoders through multi-branch parallelism.

The encoded environmental-geospatial features are fused through a hierarchical residual fusion block to allow for deep cross-factor interactions in influence prediction. A global-local attention mechanism is also structure into the residual fusion block to dynamically reweight the spatial-temporal information. The residual method through a gating mechanism integrates the shortcut outputs and transformed output to give the final prediction output, in addition to stabilizing the gradients of the network, the fused modules enhances adaptive representational learning throughout iterations of the model.

IV. Experiments

A. Experimental Setup

To accurate prediction of photovoltaic potential areas… the National Solar Radiation Database (NSRDB) was employed as the experimental basis. The database provides high-resolution meteorological and solar radiation data throughout the U.S. and parts of the world with spatial resolution of 4 km × 4 km from 1998 to present. In this experiment, data from the year 2022 of different climatic and topographic regions in southwest China were used and included the key factors including terrain elevation, total solar radiation (GHI), temperature, latitude and longitude, etc. All input factors were normalized and unified into the same spatial grid by bilinear interpolation.

The initial value selection follows the principle of "approximate identity mapping". If the network is too dependent on the reinforcement branch at the beginning, the backbone gradient will be weakened. If the enhancement branch is completely suppressed, it will not be able to reflect multi-factor information. So let's make b₀ = logit(0.9) ≈ 2.20, which corresponds to g₀ ≈ 0.9. We set up four comparison models, which represent different modeling ideas of traditional methods, standard deep learning models, and mainstream residual structures:

Random Forest Regression (RF) is an ensemble learning technique that enhances regression performance by generating multiple decision trees and averaging their predictions with weights for aggregation.

The Standard Deep Neural Network (DNN) is a feedforward fully connected neural network that contains 4 hidden layers, with each layer having 256 neurons, utilizing the ReLU activation function with the Dropout regularization method.

Image Feature Datum (ResNet-18) framework is a traditional residual convolutional neural network structure used in image recognition tasks; under constraints of no special attention mechanism or multimodal structure, ResNet-18 can extract hierarchical information to a degree, but it does have limitations for heterogeneous fusion.

The CNN-LSTM hybrid model considers both the characteristics of CNN for spatial feature extraction and the characteristics of LSTM for temporal modeling. The processing is completed with first the spatial features are processed with a two-layer convolution module, and then through a one-layer LSTM structure to model the distribution characteristics between the regions.

B. Experimental Analysis

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) measures the difference between the predicted value and the true value of the model, which has a strong sensitivity to the large value of the prediction error, and can reflect the robustness of the model to the abnormal region.

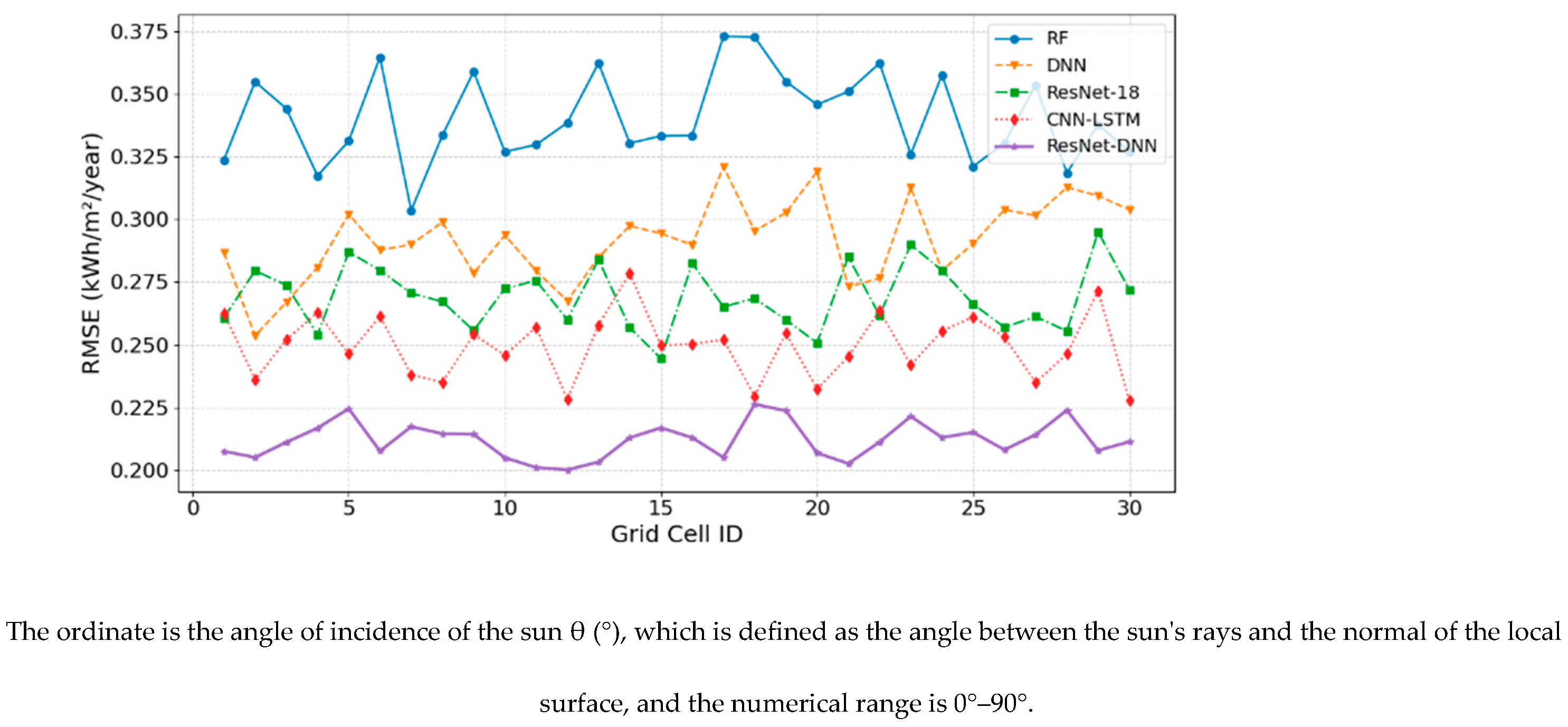

Based on evaluation of the

Figure 2 results of the 30 grids, the RMSE of ResNet-DNN is consistently at the 0.20–0.23 kWh/m²/year interval which is lowest among the CNN-LSTM, ResNet-18, DNN and RF whilst being superbly stable with little variation in RMSE result residuals. The success of ResNet-DNN is attributable to the collective benefits of multi-branched co-position coding and hierarchical residual fusion alongside global-local attention coding, whereas the baseline models suffer from no cross-position co-text semantic coding or local spatial coding for data support. The outcome suggests that ResNet-DNN has the best overall performance prediciting real PV potential.

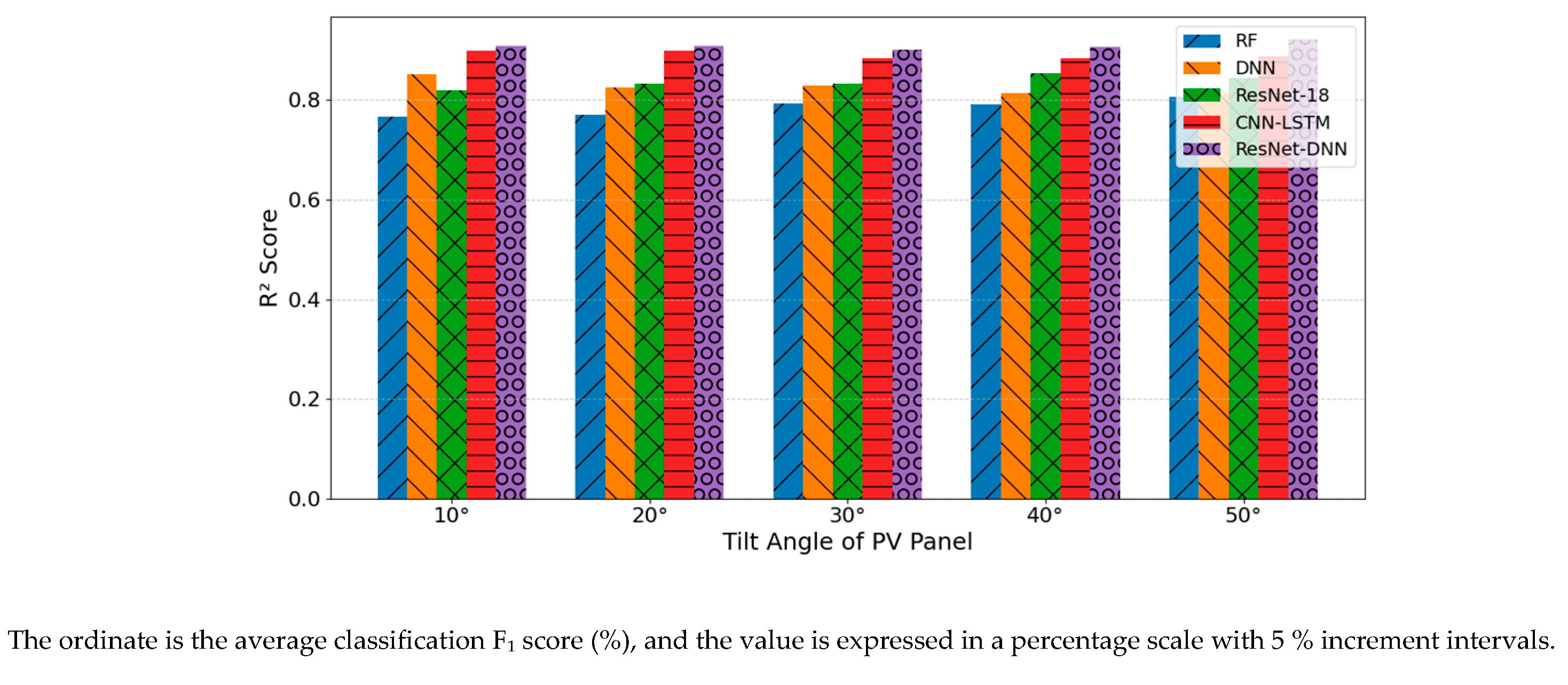

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the goodness-of-fit for each model exhibited a slight increase as the inclination angle elevated from 10° to 50°; however, ResNet-DNN continuously held the lead—the R² value consistently registered above 0.90 for the entire range of inclination. The second model was CNN-LSTM (≈0.87), which was followed by ResNet-18 and DNN, respectively, and the one with the lowest goodness-of-fit was RF. It is also noteworthy that ResNet-DNN had the lowest fluctuation of R² values (≈0.90-0.92), indicating it has superior robustness and generalization ability to adapt to the critical physical parameter of inclination. On the other hand, traditional DNN and RF showed noticeably lower fit with the high inclinations, which indicate insufficient adjustment to spatial-geometric conditions.

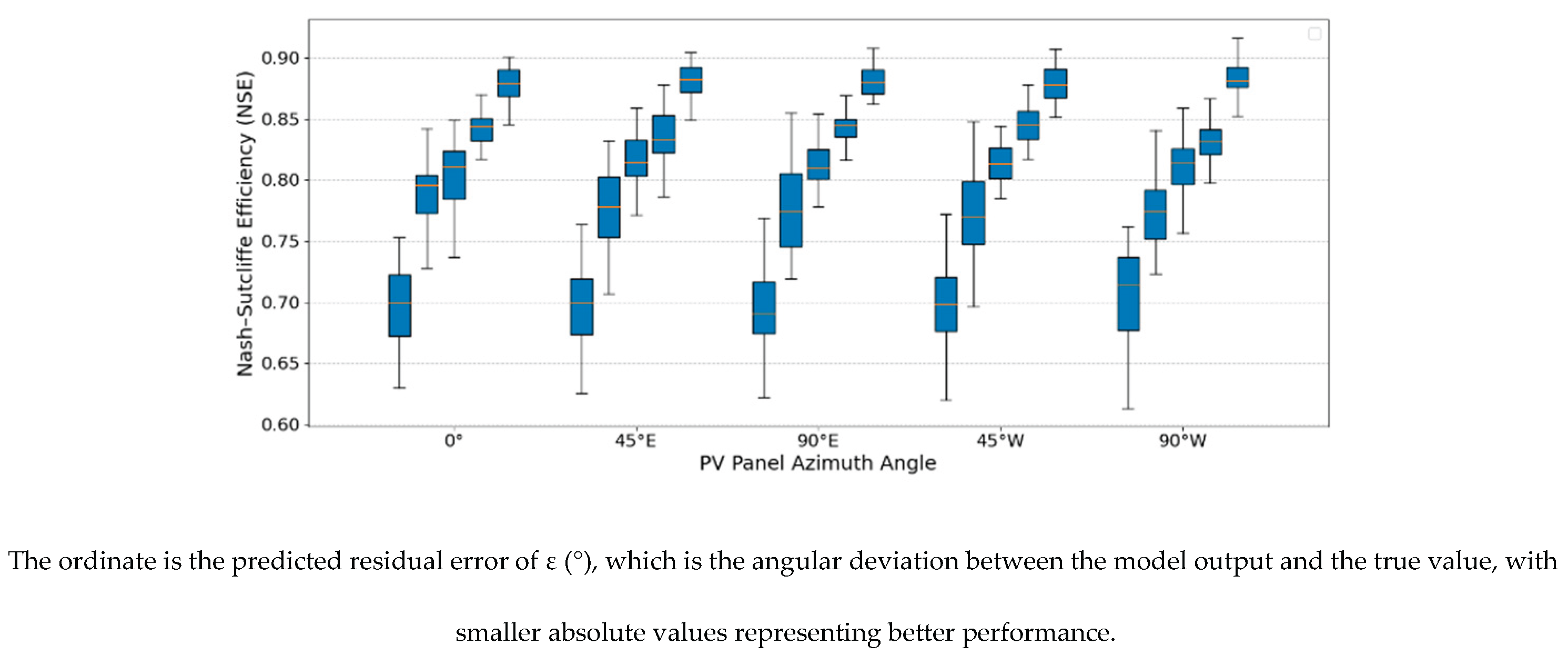

The median NSE of ResNet-DNN demonstrated, as shown in

Figure 4, the best performance (median near to 0.90), and demonstrated the narrowest box span among the five azimuths (0°, 45°E, 90°E, 45°W, 90°W) . CNN-LSTM was not far behind (median ≈ 0.85), ResNet-18 and DNN were mid-tier, while traditional RF demonstrated the least performance and the least consistency overall. These results suggest that using multi-branch factor modeling and residual-attention fusion can downplay the effects of illumination deviations from the azimuth angle, thus fostering more robustness of a model; models that do not use the deep fusion mechanisms or do not explicitly identify spatial geometry seemed to tend to more unwanted fluctuation in their performance.

The average training duration of the baseline ResNet-18 is about 1.05 ± 0.02 min/epoch; The complete model with multi-branch + HFAM + LDML took 1.20–1.30 min/epoch, with a relative increase of 14–24 % depending on the number of factor branches (N = 3–5).

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, a multi-factor ResNet-DNN is introduced based on actual NSRDB data that deeply couples information such as the topography, irradiation, and temperature with the help of a multi-branch coding, hierarchical residual fusion, and global-local attention. The experimental results show that ResNet-DNN is better than RF, DNN, ResNet-18, and CNN-LSTM in RMSE, R², NSE, and other indicators, and maintains the lowest error and the best robustness under different inclination angles and azimuths. In the future, we will include more global remote sensing and aerosol observations to achieve cross-regional migration; introduce time series transformers and uncertainty quantification to deal with extreme weather; and coupling the model with economic-grid constraints to develop a real-time PV site selection and O&M decision-making system.

References

- Zhai, C., He, X., Cao, Z., Abdou-Tankari, M., Wang, Y., & Zhang, M. (2025). Photovoltaic power forecasting based on VMD-SSA-Transformer: Multidimensional analysis of dataset length, weather mutation and forecast accuracy. Energy, 324, 135971. [CrossRef]

- Khelifi, R., Guermoui, M., Rabehi, A., Taallah, A., Zoukel, A., Ghoneim, S. S., ... & Zaitsev, I. (2023). Short-Term PV Power Forecasting Using a Hybrid TVF-EMD-ELM Strategy. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems, 2023(1), 6413716.

- Cui, Y., Liu, M., Li, W., Lian, J., Yao, Y., Gao, X., ... & Yin, J. (2024). An exploratory framework to identify dust on photovoltaic panels in offshore floating solar power stations. Energy, 307, 132559. [CrossRef]

- Jouane, Y., Abouelaziz, I., Saddik, I., & Oussous, O. (2025). Lightweight deep learning for photovoltaic energy prediction: Optimizing decarbonization in winter houses. Solar Energy, 297, 113567. [CrossRef]

- Cui, W., Peng, X., Yang, J., Yuan, H., & Lai, L. L. (2023). Evaluation of rooftop photovoltaic power generation potential based on deep learning and high-definition map image. Energies, 16(18), 6563. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Wang, Q., Han, Y., Ma, Y., Zhao, H., Nowak, A., & Li, J. (2021). Deep learning for ultra-fast and high precision screening of energy materials. Energy Storage Materials, 39, 45-53. [CrossRef]

- Aktouf, L., Shivanna, Y., & Dhimish, M. (2024). High-Precision defect detection in solar cells using YOLOv10 deep learning model. In Solar, Vol. 4, No. 4, 639-659. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Zhang, C., Yu, Z., Zhang, H., & Jiang, H. (2023). Deep Learning Method for Evaluating Photovoltaic Potential of Rural Land Use Types. Sustainability, 15(14), 10798. [CrossRef]

- Guermoui, M., Bouchouicha, K., Bailek, N., & Boland, J. W. (2021). Forecasting intra-hour variance of photovoltaic power using a new integrated model. Energy Conversion and Management, 245, 114569. [CrossRef]

- Min, H., Hong, S., Song, J., Son, B., Noh, B., & Moon, J. (2024). SolarFlux predictor: a novel deep learning approach for photovoltaic power forecasting in South Korea. Electronics, 13(11), 2071. [CrossRef]

- Elmessery, W. M., Habib, A., Shams, M. Y., Abd El-Hafeez, T., El-Messery, T. M., Elsayed, S., ... & Elwakeel, A. E. (2024). Deep regression analysis for enhanced thermal control in photovoltaic energy systems. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 30600. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).