Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

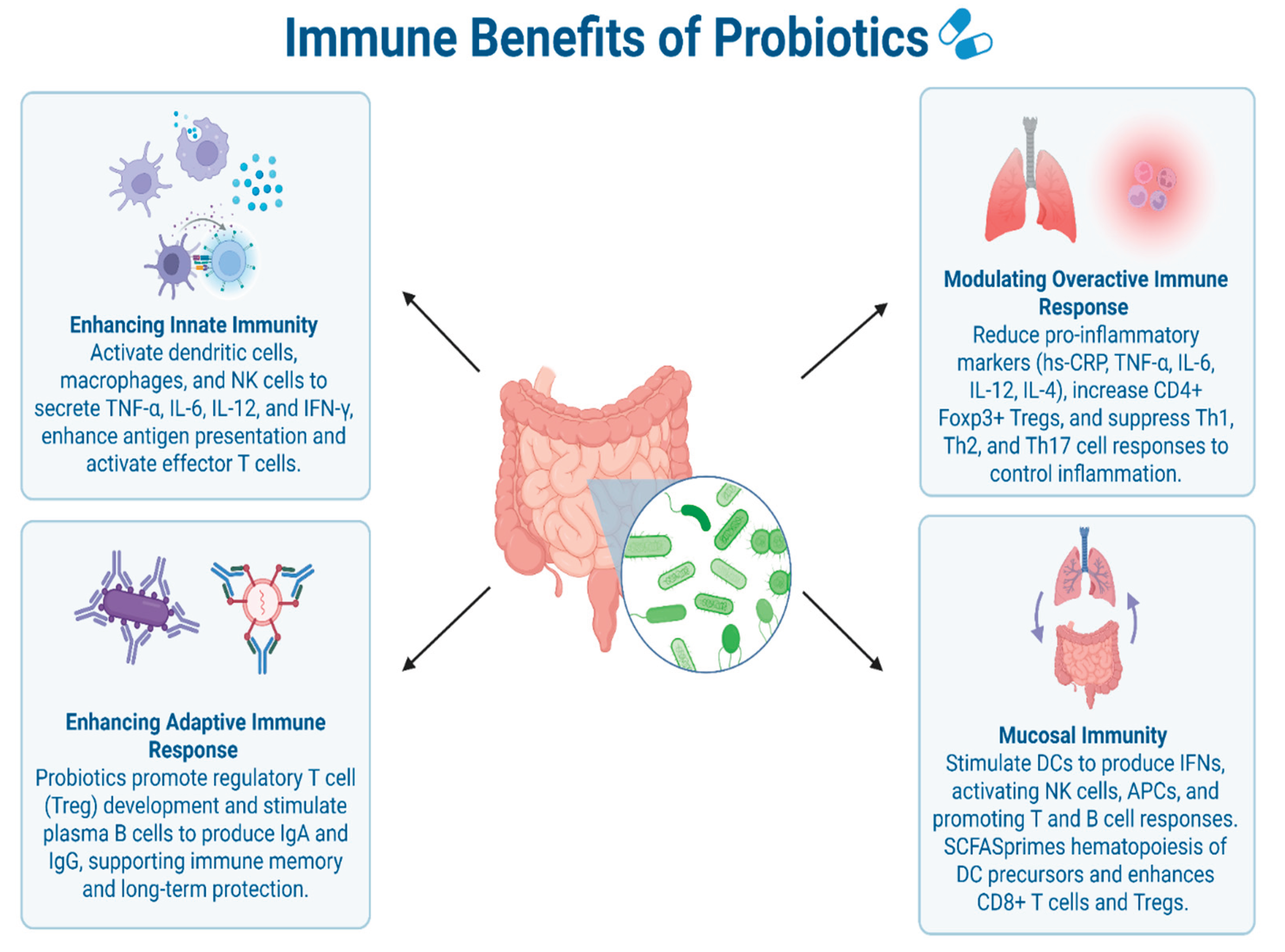

2. Effects of Probiotics on Immune Response

2.1. Enhancing Innate Immune Response

2.2. Enhancing Adaptive Immune Response

2.3. Modulating Inflammatory Cytokines and Overactive Immune Responses

2.4. Mucosal Immunity Modulation

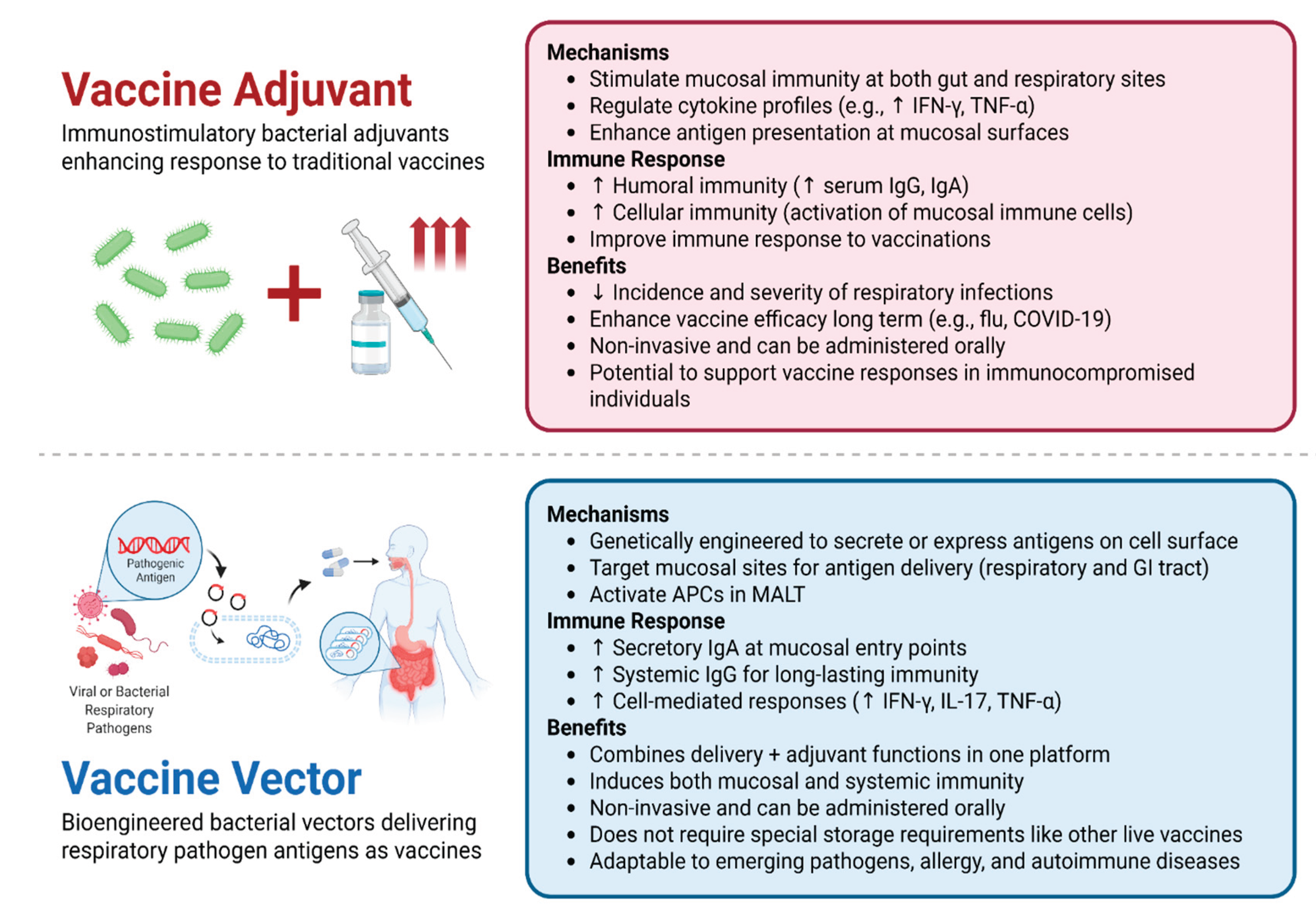

3. Probiotic Use in Vaccine Research

3.1. Probiotics as Vaccine Adjuvants

3.2. Probiotics as Vaccine Vectors and Potential Candidates

4. Current Status of Human Clinical Trials

5. Discussion

- Identify and characterize immunologically active strains, with a focus on their antigen-presenting and immune-modulatory mechanisms.

- Optimize delivery platforms and dosing strategies across different age groups and health conditions.

- Evaluate long-term immune memory and durability, including booster responses and cross-protection.

- Establish standardized global safety benchmarks, accounting for geographic and ethnic variations in microbiota composition.

- Integrate probiotic-based vaccine approaches into existing immunization programs, particularly in resource-limited settings and for diseases with mucosal entry routes.

References

- Kazemifard, N.; Dehkohneh, A.; Baradaran Ghavami, S. Probiotics and Probiotic-Based Vaccines: A Novel Approach for Improving Vaccine Efficacy. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 940454, . [CrossRef]

- Muthukutty, P.; MacDonald, J.; Yoo, S.Y. Combating Emerging Respiratory Viruses: Lessons and Future Antiviral Strategies. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1220, . [CrossRef]

- Md Khairi, L.N.H.; Fahrni, M.L.; Lazzarino, A.I. The Race for Global Equitable Access to COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1306, . [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wu, L.; Huntington, N.D.; Zhang, X. Crosstalk Between Gut Microbiota and Innate Immunity and Its Implication in Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, . [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, M.; Gaur, S. Probiotics as Multifaceted Oral Vaccines against Colon Cancer: A Review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, . [CrossRef]

- Hagan, T.; Cortese, M.; Rouphael, N.; Boudreau, C.; Linde, C.; Maddur, M.S.; Das, J.; Wang, H.; Guthmiller, J.; Zheng, N.-Y.; et al. Antibiotics-Driven Gut Microbiome Perturbation Alters Immunity to Vaccines in Humans. Cell 2019, 178, 1313-1328.e13, . [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-J.; Wu, E. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Immune Homeostasis and Autoimmunity. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 4–14, . [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Aqib, A.I.; Fatima, M.; Muneer, S.; Zaheer, T.; Peng, S.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Li, K. Deciphering the Potential of Probiotics in Vaccines. Vaccines 2024, 12, 711, . [CrossRef]

- Taghinezhad-S, S.; Mohseni, A.H.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Casolaro, V.; Cortes-Perez, N.G.; Keyvani, H.; Simal-Gandara, J. Probiotic-Based Vaccines May Provide Effective Protection against COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Disease. Vaccines 2021, 9, 466, . [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.-T.; Shih, P.-C.; Liu, S.-J.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yeh, T.-L. Effect of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Immune Response to Influenza Vaccination in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1175, . [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mok, C.K.; Zhao, S.; Li, A.; Ching, J.Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, S.; Chan, D.L.S.; et al. Gut Microbiota Composition Is Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Immunogenicity and Adverse Events. 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.S.M. Interaction between Gut Microbiota and COVID-19 and Its Vaccines. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 5801–5806, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, C. Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune System by Probiotics, Pre-Biotics, and Post-Biotics. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, . [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Chen, C.; Patil, S.; Dong, S. Unveiling the Therapeutic Symphony of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Postbiotics in Gut-Immune Harmony. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Moon, A.; Huang, J.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, H.-J. Antiviral Effects and Underlying Mechanisms of Probiotics as Promising Antivirals. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 928050, . [CrossRef]

- Jounai, K.; Ikado, K.; Sugimura, T.; Ano, Y.; Braun, J.; Fujiwara, D. Spherical Lactic Acid Bacteria Activate Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Immunomodulatory Function via TLR9-Dependent Crosstalk with Myeloid Dendritic Cells. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e32588, . [CrossRef]

- Kanauchi, O.; Low, Z.X.; Jounai, K.; Tsuji, R.; AbuBakar, S. Overview of Anti-Viral Effects of Probiotics via Immune Cells in Pre-, Mid- and Post-SARS-CoV2 Era. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1280680, . [CrossRef]

- Paineau, D.; Carcano, D.; Leyer, G.; Darquy, S.; Alyanakian, M.-A.; Simoneau, G.; Bergmann, J.-F.; Brassart, D.; Bornet, F.; Ouwehand, A.C. Effects of Seven Potential Probiotic Strains on Specific Immune Responses in Healthy Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 53, 107–113, . [CrossRef]

- Milajerdi, A.; Mousavi, S.M.; Sadeghi, A.; Salari-Moghaddam, A.; Parohan, M.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. The Effect of Probiotics on Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 633–649, . [CrossRef]

- Mazziotta, C.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F.; Torreggiani, E.; Rotondo, J.C. Probiotics Mechanism of Action on Immune Cells and Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Cells 2023, 12, 184, . [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.-K.; Lee, C.-G.; So, J.-S.; Chae, C.-S.; Hwang, J.-S.; Sahoo, A.; Nam, J.H.; Rhee, J.H.; Hwang, K.-C.; Im, S.-H. Generation of Regulatory Dendritic Cells and CD4+Foxp3+ T Cells by Probiotics Administration Suppresses Immune Disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 2159–2164, . [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.T.; Marsland, B.J. Microbes, Metabolites, and the Gut–Lung Axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 843–850, . [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.S.; Ricci, M.F.; Vieira, A.T. Gut Microbiota Modulation as a Potential Target for the Treatment of Lung Infections. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Limaye, A.; Liu, J.-R.; Wu, T.-N. Potential Probiotics for Regulation of the Gut-Lung Axis to Prevent or Alleviate Influenza in Vulnerable Populations. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2023, 13, 161–169, . [CrossRef]

- Amrouche, T.; Chikindas, M.L.; Amrouche, T.; Chikindas, M.L. Probiotics for Immunomodulation in Prevention against Respiratory Viral Infections with Special Emphasis on COVID-19. AIMS Microbiol. 2022, 8, 338–356, . [CrossRef]

- Song, J.A.; Kim, H.J.; Hong, S.K.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.W.; Song, C.S.; Kim, K.T.; Choi, I.S.; Lee, J.B.; Park, S.Y. Oral Intake of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus M21 Enhances the Survival Rate of Mice Lethally Infected with Influenza Virus. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2016, 49, 16–23, . [CrossRef]

- Fonollá, J.; Gracián, C.; Maldonado-Lobón, J.A.; Romero, C.; Bédmar, A.; Carrillo, J.C.; Martín-Castro, C.; Cabrera, A.L.; García-Curiel, J.M.; Rodríguez, C.; et al. Effects of Lactobacillus Coryniformis K8 CECT5711 on the Immune Response to Influenza Vaccination and the Assessment of Common Respiratory Symptoms in Elderly Subjects: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 83–90, . [CrossRef]

- Sandionigi, A.; De Giani, A.; Tursi, F.; Michelotti, A.; Cestone, E.; Giardina, S.; Zampolli, J.; Di Gennaro, P. Effectiveness of Multistrain Probiotic Formulation on Common Infectious Disease Symptoms and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Flu-Vaccinated Healthy Elderly Subjects. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 3860896, . [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, B.R.; Hao, Q. Probiotics for Preventing Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections - Zhao, Y - 2022 | Cochrane Library.

- Forsgård, R.A.; Rode ,Julia; Lobenius-Palmér ,Karin; Kamm ,Annalena; Patil ,Snehal; Tacken ,Mirriam G. J.; Lentjes ,Marleen A. H.; Axelsson ,Jakob; Grompone ,Gianfranco; Montgomery ,Scott; et al. Limosilactobacillus Reuteri DSM 17938 Supplementation and SARS-CoV-2 Specific Antibody Response in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Triple-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2229938, . [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, G.; Borrazzo, C.; Pinacchio, C.; Santinelli, L.; Innocenti, G.P.; Cavallari, E.N.; Celani, L.; Marazzato, M.; Alessandri, F.; Ruberto, F.; et al. Oral Bacteriotherapy in Patients With COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, . [CrossRef]

- Levit, R.; Cortes-Perez, N.G.; Leblanc, A. de M. de; Loiseau, J.; Aucouturier, A.; Langella, P.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Use of Genetically Modified Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria as Live Delivery Vectors for Human and Animal Health. Gut Microbes 2022.

- Mezhenskaya, D.; Isakova-Sivak, I.; Gupalova, T.; Bormotova, E.; Kuleshevich, E.; Kramskaya, T.; Leontieva, G.; Rudenko, L.; Suvorov, A. A Live Probiotic Vaccine Prototype Based on Conserved Influenza a Virus Antigens Protect Mice against Lethal Influenza Virus Infection. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1515, . [CrossRef]

- Temprana, C.F.; Argüelles, M.H.; Gutierrez, N.M.; Barril, P.A.; Esteban, L.E.; Silvestre, D.; Mandile, M.G.; Glikmann, G.; Castello, A.A. Rotavirus VP6 Protein Mucosally Delivered by Cell Wall-Derived Particles from Lactococcus Lactis Induces Protection against Infection in a Murine Model. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0203700, . [CrossRef]

- Nakao, R.; Kobayashi, H.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Kawahara, K.; Hirayama, S.; Ramstedt, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Kataoka, M.; Akeda, Y.; Ohnishi, M. A Highly Immunogenic Vaccine Platform against Encapsulated Pathogens Using Chimeric Probiotic Escherichia Coli Membrane Vesicles. Npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 1–17, . [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, M.; Hao, J.; Han, J.; Fu, T.; Bai, J.; Tian, M.; Jin, N.; Zhu, G.; Li, C. Mucosal IgA Response Elicited by Intranasal Immunization of Lactobacillus Plantarum Expressing Surface-Displayed RBD Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 409–416, . [CrossRef]

- Xuan, B.; Park, J.; Yoo, J.H.; Kim, E.B. Oral Immunization of Mice with Cell Extracts from Recombinant Lactococcus Lactis Expressing SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 167, . [CrossRef]

- de Castro, C.P.; Souza, B.M.; Mancha-Agresti, P.; Pereira, V.B.; Zurita-Turk, M.; Preisser, T.M.; da Cunha, V.P.; dos Santos, J.S.C.; Leclercq, S.Y.; Azevedo, V.; et al. Lactococcus Lactis FNBPA+ (pValac:E6ag85a) Induces Cellular and Humoral Immune Responses After Oral Immunization of Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 676172, . [CrossRef]

- Symvivo Corporation A Phase 1, Randomized, Observer-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of the bacTRL-Spike Oral Candidate Vaccine for the Prevention of COVID-19 in Healthy Adults; clinicaltrials.gov, 2022;

- Sung, J.C.-C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, K.-C.; Choi, M.-C.; Ma, C.H.-Y.; Lin, J.; He, E.I.C.; Leung, D.Y.-M.; Sze, E.T.-P.; Hamied, Y.K.; et al. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Receptor Binding Domain on Recombinant B. Subtilis on Spore Surface: A Potential COVID-19 Oral Vaccine Candidate. Vaccines 2021, 10, 2, . [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.C.-C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, K.-C.; Choi, M.-C.; Ma, C.H.-Y.; Lin, J.; He, E.I.C.; Leung, D.Y.-M.; Sze, E.T.-P.; Hamied, Y.K.; et al. Retraction: Sung et al. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Receptor Binding Domain on Recombinant B. Subtilis on Spore Surface: A Potential COVID-19 Oral Vaccine Candidate. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1852, . [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.Gov Glossary Terms | ClinicalTrials.Gov Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study-basics/glossary (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Search for: Respiratory Disease, Other Terms: Probiotic Vaccine | List Results | ClinicalTrials.Gov Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Respiratory%20Disease&term=Probiotic%20vaccine (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Peroni, D.G.; Morelli, L. Probiotics as Adjuvants in Vaccine Strategy: Is There More Room for Improvement? Vaccines 2021, 9, 811, . [CrossRef]

- Akatsu, H. Exploring the Effect of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Postbiotics in Strengthening Immune Activity in the Elderly. Vaccines 2021, 9, 136, . [CrossRef]

- Church, J.A.; Rukobo, S.; Govha, M.; Lee, B.; Carmolli, M.P.; Chasekwa, B.; Ntozini, R.; Mutasa, K.; McNeal, M.M.; Majo, F.D.; et al. The Impact of Improved Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene on Oral Rotavirus Vaccine Immunogenicity in Zimbabwean Infants: Substudy of a Cluster-Randomized Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 2074–2081, . [CrossRef]

- Jiang, V.; Jiang, B.; Tate, J.; Parashar, U.D.; Patel, M.M. Performance of Rotavirus Vaccines in Developed and Developing Countries. Hum. Vaccin. 2010, 6, 532–542, . [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.M. Immunogenicity and Efficacy of Oral Vaccines in Developing Countries: Lessons from a Live Cholera Vaccine. BMC Biol. 2010, 8, 129, . [CrossRef]

| # | Respiratory Disease | Probiotic Use (vaccine adjuvant/ live vaccine) | Bacterial Strain | Phase | NCT # |

| 1 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Multistrain Probiotic (unspecified) | N/A | NCT06103994 |

| 2 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Probiotic supplement (unspecified) | N/A | NCT05690373 |

| 3 | COVID-19 | vaccine adjuvant | 2-strain probiotic blend (unspecified) | N/A | NCT05195151 |

| 4 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum + P. acidilactici | N/A | NCT05157425 |

| 5 | COVID-19 | vaccine adjuvant | Bifidobacteria blend 3 strains (unpecified) | N/A | NCT04884776 |

| 6 | COVID-19 | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus | N/A | NCT04756466 |

| 7 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus acidophilus + Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Phase 4 | NCT03695432 |

| 8 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant |

Lactobacillus coryniformis |

Phase 2 | NCT03167593 |

| 9 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus paracasei | N/A | NCT02909842 |

| 10 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus Gasseri + Bifidobacterium Longum + Bifidobacterium Bifidum | N/A | NCT01652066 |

| 11 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | Phase 1 | NCT01545349 |

| 12 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | Phase 1 | NCT01368029 |

| 13 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Enterococcus faecium + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Phase 1 | NCT01304771 |

| 14 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Bifidobacterium longum | N/A | NCT01066377 |

| 15 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus casei Shirota | Phase 4 | NCT00849277 |

| 16 | Influenza | vaccine adjuvant | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Phase 1 | NCT00620412 |

| 17 | Influenza and COVID-19 | vaccine adjuvant | Saccharomyces cerevisiae blend | N/A | NCT04798677 |

| 18 | COVID-19 | Live vector vaccine | Bifidobacterium longum | Phase I | NCT04334980 |

| 19* | COVID-19 | Live vector vaccine | Bacillus subtilis | N/A | NCT05057923 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).