Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sensitivity and Selectivity of LAMP Detection

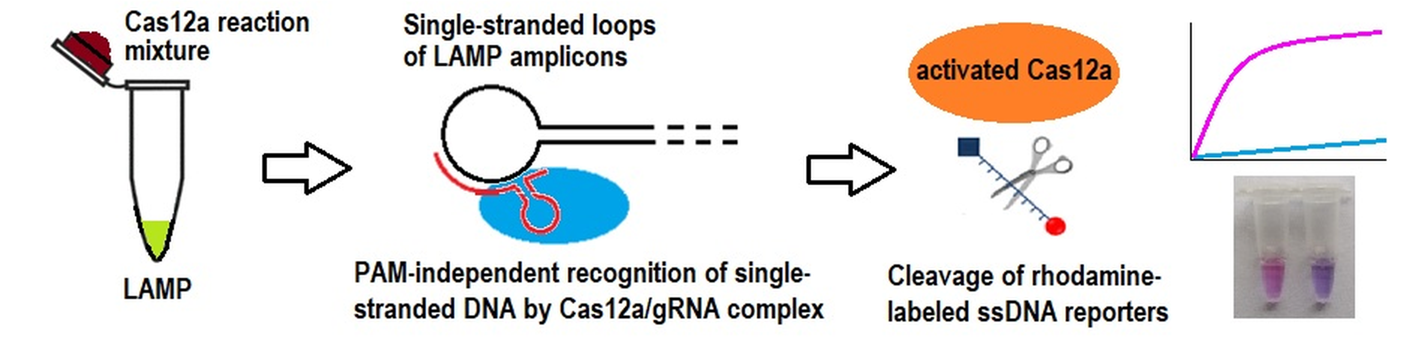

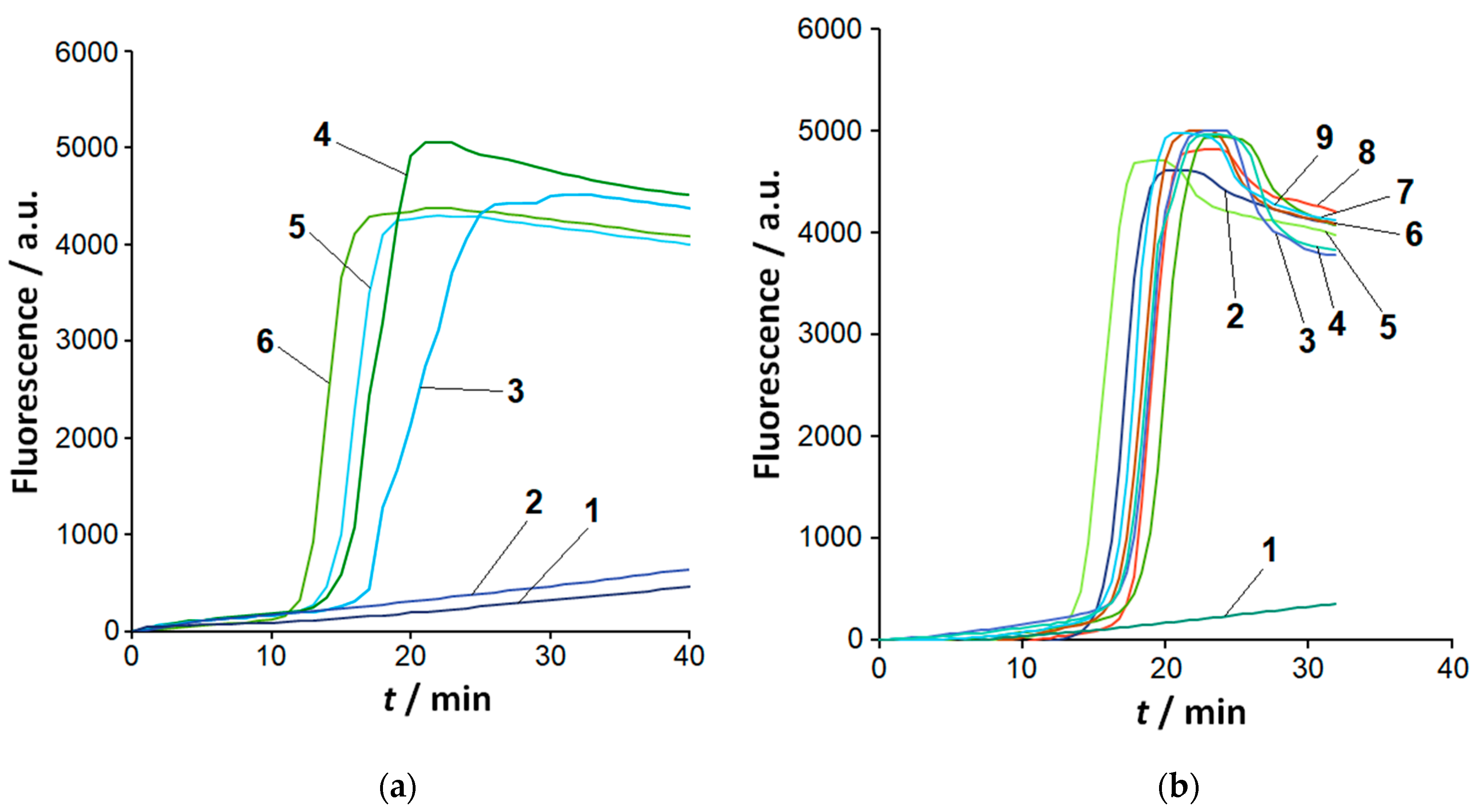

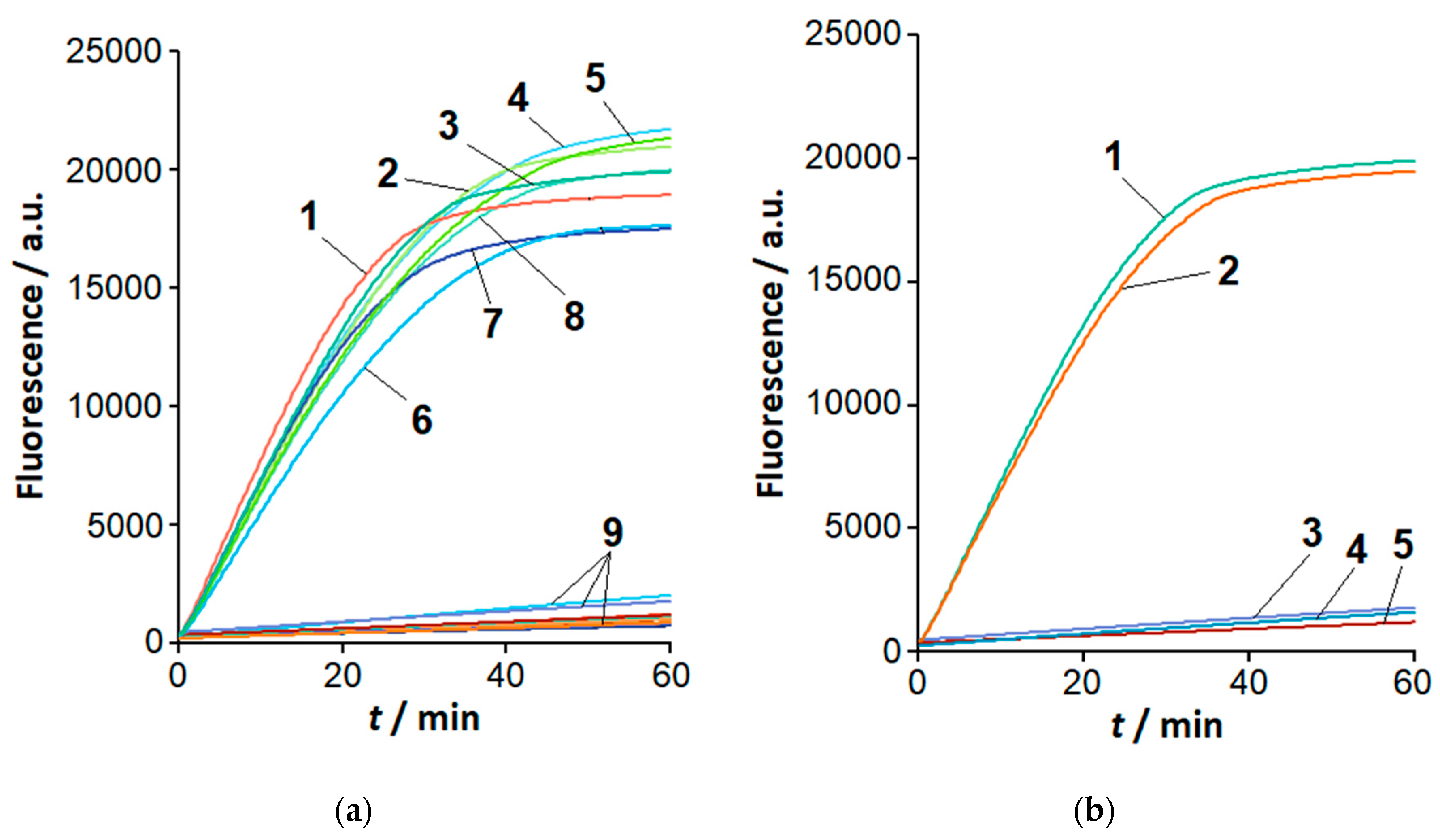

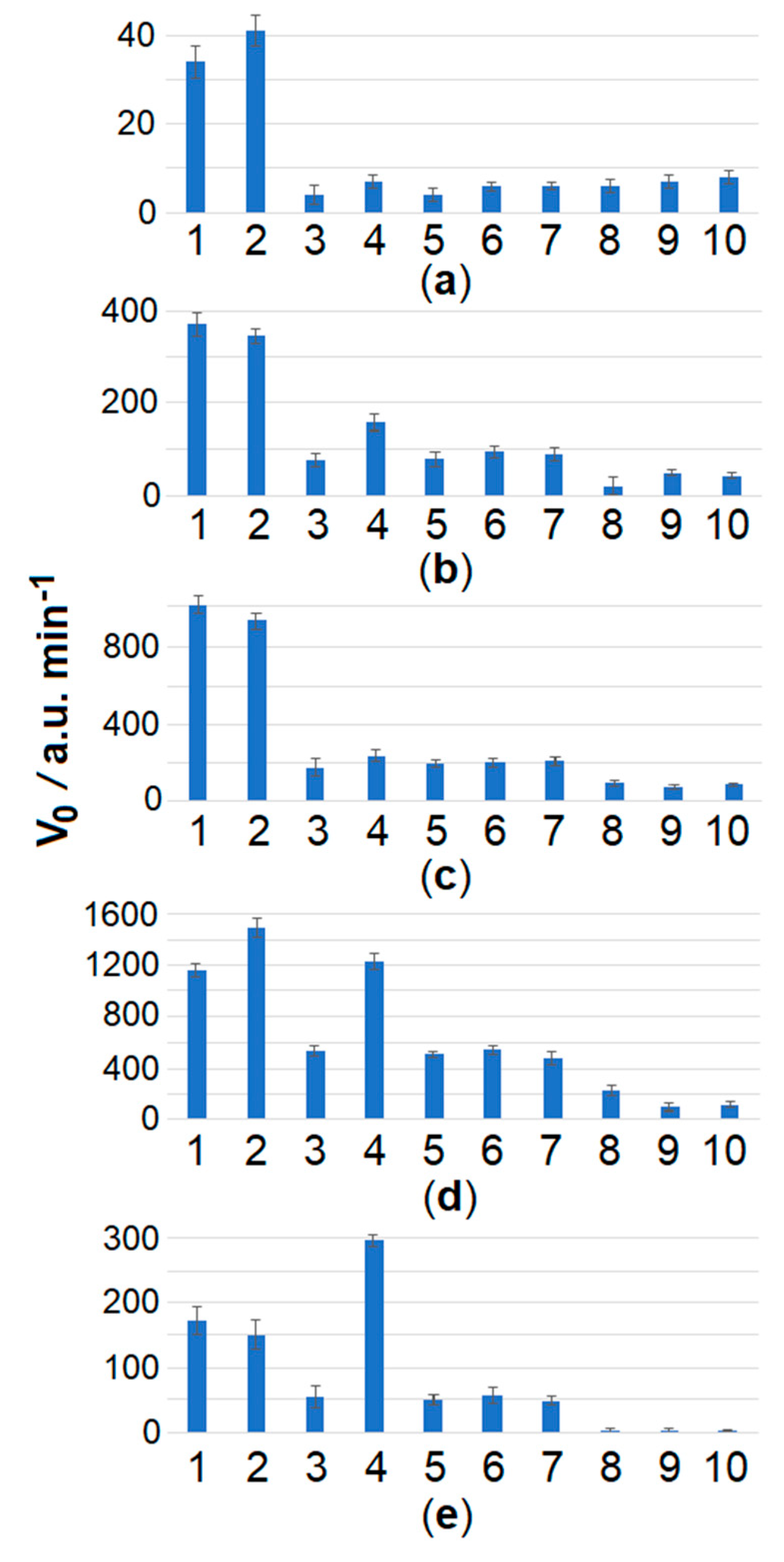

2.2. The Loop-Targeted Cas12a Analysis of LAMP Products

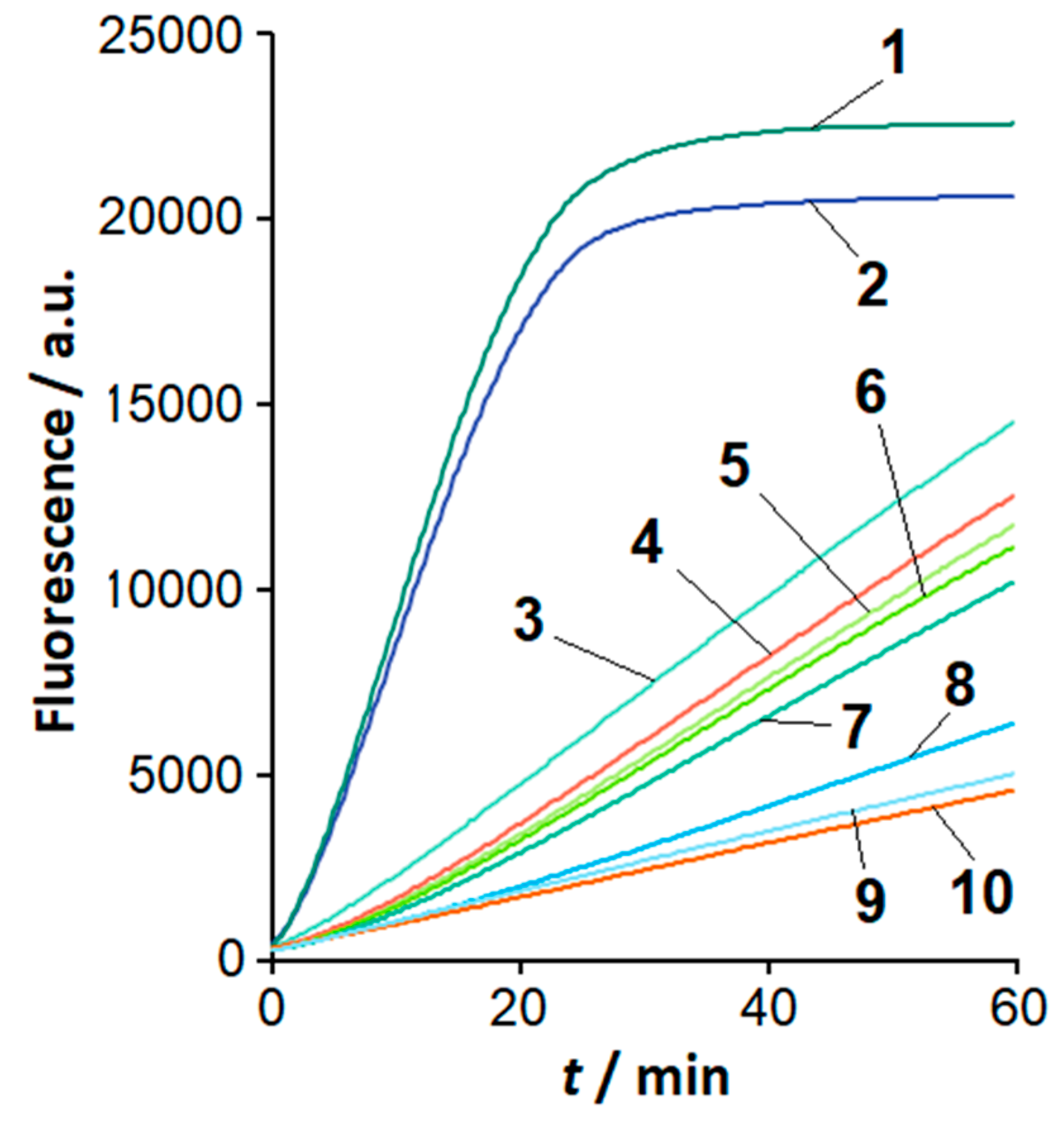

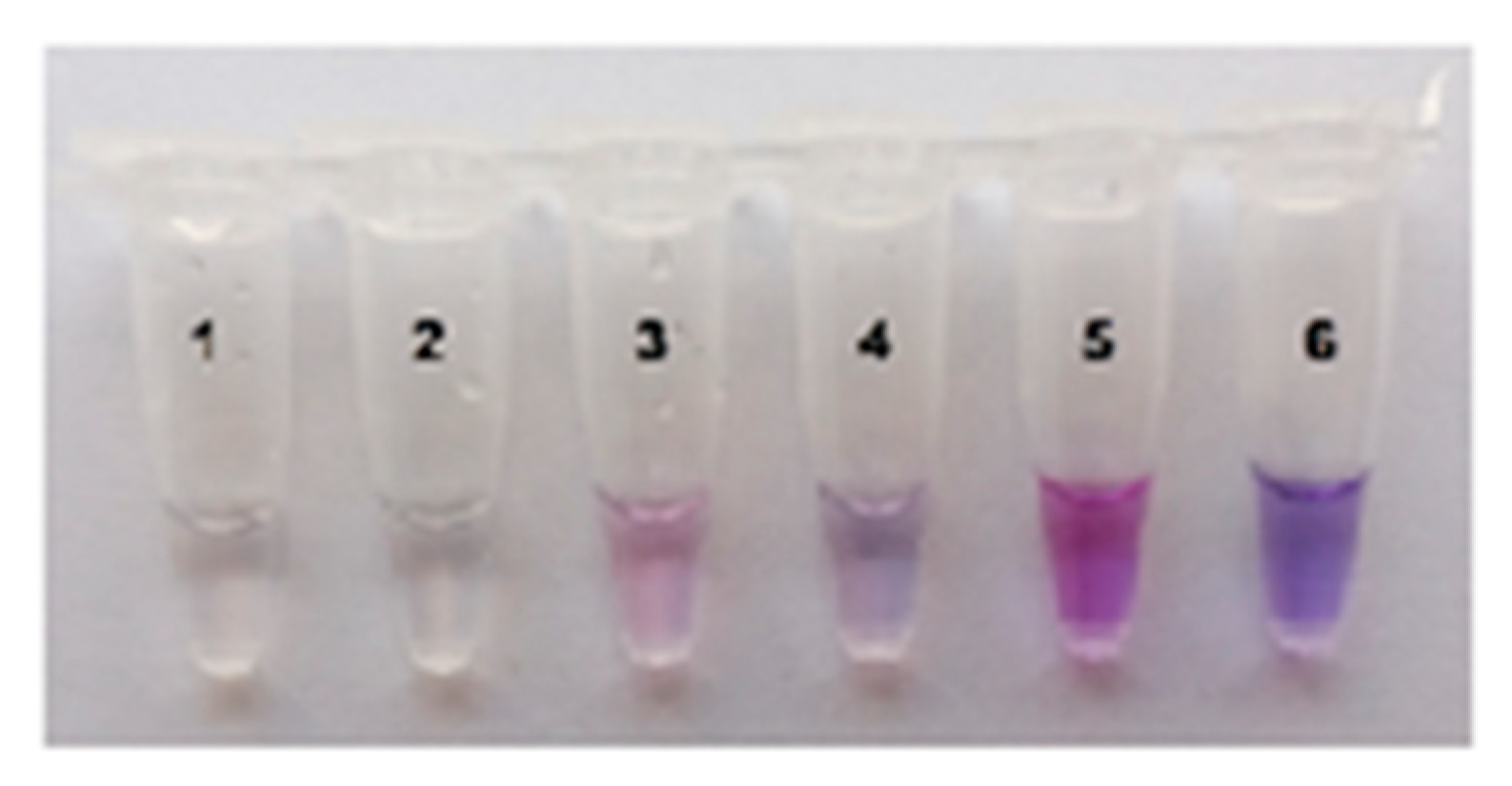

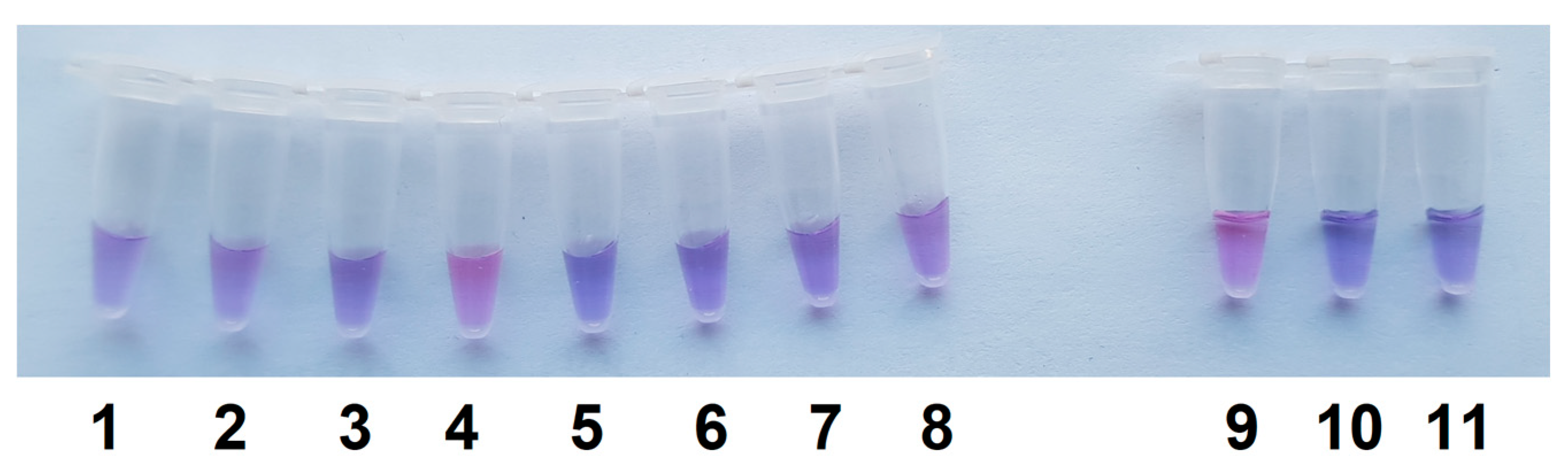

2.3. Visual Detection of C. sepedonicus in a Single Reaction Tube

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Bacteria Culturing and DNA Isolation

4.3. LAMP Procedure

4.4. Real-Time Cas12a Cleavage Assay

4.5. A Single Test Tube Assay

4.6. Statistical Treatment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; Jin, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y. Advances in the application of molecular diagnostic techniques for the detection of infectious disease pathogens (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Abd El Wahed, A. Point-Of-Care or Point-Of-Need Diagnostic Tests: Time to Change Outbreak Investigation and Pathogen Detection. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, V.R.; Carson, M.S.; Lao, A.; Maran, K.; Yang, E.J.; Kamei, D.T. Point-of-Need Diagnostics for Foodborne Pathogen Screening. SLAS Technol. 2021, 26, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Park, S.; Kim, B.N.; Kwon, O.S.; Rho, W.-Y.; Jun, B.-H. Emerging ultrafast nucleic acid amplification technologies for next-generation molecular diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, H.; Han, X.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y. Advancements and applications of loop-mediated isothermal amplification technology: A comprehensive overview. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1406632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notomi, T.; Okayama, H.; Masubuchi, H.; Yonekawa, T.; Watanabe, K.; Amino, N.; Hase, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 63e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atceken, N.; Yigci, D.; Ozdalgic, B.; Tasoglu, S. CRISPR-Cas-Integrated LAMP. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Zhou, C.; Gao, B.; Liu, F.; Ma, L.; Guo, F. Engineering CRISPR/Cas12-based biosensors: Recent advances and future perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 191, 118296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmeleva, S.A.; Ptitsyn, K.G.; Kurbatov, L.K.; Timoshenko, O.S.; Suprun, E.V.; Radko, S.P.; Lisitsa, A.V. Biosensing platforms for DNA diagnostics based on CRISPR/Cas nucleases: Towards the detection of nucleic acids at the level of single molecules in non-laboratory settings. Biomed. Khim. 2024, 70, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Goswami, H.N.; Whyms, C.T.; Sridhara, S.; Li, H. Structural principles of CRISPR-Cas enzymes used in nucleic acid detection. J. Struct. Biol. 2022, 214, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Zheng, J.; Liu, C.; Ye, W.; Song, S.; Bai, T.; Song, C.; Wang, M.; Shi, J.; Wan, R.; Zhang, K.; Hao, P.; Feng, J.; Zheng, X. The engineered CRISPR-Mb2Cas12a variant enables sensitive and fast nucleic acid-based pathogens diagnostics in the field. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.; Guo, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Weng, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, B. Fast and visual detection of nucleic acids using a one-step RPA-CRISPR detection (ORCD) system unrestricted by the PAM. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1248, 340938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, L. PAM-free loop-mediated isothermal amplification coupled with CRISPR/Cas12a cleavage (Cas-PfLAMP) for rapid detection of rice pathogens. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 204, 114076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptitsyn, K.G.; Khmeleva, S.A.; Kurbatov, L.K.; Timoshenko, O.S.; Suprun, E.V.; Radko, S.P.; Lisitsa, A.V. Lamp Primer Designing Software: The Overview. Biomed. Chem. Res. Meth. 2024, 7, e00226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, K.; Hase, T.; Notomi, T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes 2002, 16, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenlaub, R.; Gartemann, K.-H.; Burger, A. Clavibacter michiganensis, a group of gram-positive phytopathogenic bacteria. In Plant-Associated Bacteria; GnanamanickamS.S.Springer International Publishing: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 385–421. ISBN 978-1-4020-4536-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobhal, S.; Larrea-Sarmiento, A.; Alvarez, A.M.; Arif, M. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for specific detection of all known subspecies of Clavibacter michiganensis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambong, J.T. Comparative genomics of Clavibacter michiganensis subspecies, pathogens of important agricultural crops. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Nagamine, K.; Tomita, N.; Notomi, T. Detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction by turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 289, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarts, D.C. Making the cut(s): How Cas12a cleaves target and non-target DNA. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Xie, L.; Yang, T.; Huo, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Zeng, Z. Naked-eye on-site detection platform for Pasteurella multocida based on the CRISPR-Cas12a system coupled with recombinase polymerase amplification. Talanta 2023, 255, 124220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Kancharla, N.; Javalkote, V.S.; Dasgupta, S.; Brutnell, T.P. CRISPR-Cas12a (Cpf1): A Versatile Tool in the Plant Genome Editing Tool Box for Agricultural Advancement. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 584151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moehling, T.J.; Choi, G.; Dugan, L.C.; Salit, M.; Meagher, R.J. LAMP Diagnostics at the Point-of-Care: Emerging Trends and Perspectives for the Developer Community. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 21, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.; Montoya, G. CRISPR-Cas12a: Functional overview and applications. Biomed. J. 2020, 43, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarts, D.C.; van der Oost, J.; Jinek, M. Structural Basis for Guide RNA Processing and Seed-Dependent DNA Targeting by CRISPR-Cas12a. Mol. Cell. 2017, 66, 221–233.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohkendl, I.; Saifuddin, F.A.; Rybarski, J.R.; Finkelstein, I.J.; Russell, R. Kinetic Basis for DNA Target Specificity of CRISPR-Cas12a. Mol. Cell. 2018, 71, 816–824.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranova, S.V.; Zhdanova, P.V.; Pestryakov, P.E.; Chernonosov, A.A.; Koval, V.V. Key thermodynamic characteristics of Cas9 and Cas12a endonucleases’ cleavage of a DNA substrate containing a nucleotide mismatch in the region complementary to RNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 768, 151892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q.; Yao, P.; Jiang, J.; Gong, L.; Dong, Y.; Tu, B.; Wang, R.; Tang, H.; Yao, F.; Wang, F. Iterative crRNA design and a PAM-free strategy enabled an ultra-specific RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a detection platform. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Smith, B.M.; Jain, P.K. Enhancement of trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a with engineered crRNA enables amplified nucleic acid detection. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rananaware, S.R.; Vesco, E.K.; Shoemaker, G.M.; Anekar, S.S.; Sandoval, L.S.W.; Meister, K.S.; Macaluso, N.C.; Nguyen, L.T.; Jain, P.K. Programmable RNA detection with CRISPR-Cas12a. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleuzzaman, M. Limit of Blank (LOB), Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantification (LOQ). Org. Med. Chem. Int. J. 2018, 7, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrik, K.-H. Detection of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus in Potato Tubers by Multiplex PCR with Coamplification of Host DNA. Eur. J. Plant Pathology 2000, 106, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmestad, N.C.; Mallik, I.; Pasche, J.S.; Anderson, N.R.; Kinzer, K. A Real-Time PCR Assay for the Detection of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus Based on the Cellulase A Gene Sequence. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.S.; Park, D.H.; Namgung, M.; Ahn, T.-Y.; Park, D.S. Validation and Application of a Real-time PCR Protocol for the Specific Detection and Quantification of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus in Potato. Plant Pathol. J. 2015, 31, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagcan, H.; Turgut Kara, N. Detection of Potato ring rot Pathogen Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus by Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beckhoven, J.R.C.M.; Stead, D.E.; van der Wolf, J.M. Detection of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus by AmpliDet RNA, a new technology based on real time monitoring of NASBA amplicons with a molecular beacon. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khmeleva, S.A.; Kurbatov, L.K.; Ptitsyn, K.G.; Timoshenko, O.S.; Morozova, D.D.; Suprun, E.V.; Radko, S.P.; Lisitsa, A.V. Detection of Potato Pathogen Clavibacter sepedonicus by CRISPR/Cas13a Analysis of NASBA Amplicons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suprun, E.V.; Ptitsyn, K.G.; Khmeleva, S.A.; Kurbatov, L.K.; Shershov, V.E.; Kuznetsova, V.E.; Chudinov, A.V.; Radko, S.P.; Lisitsa, A.V. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification with tyrosine modified 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate: Detection of potato pathogen Clavibacter sepedonicus by direct voltammetry of LAMPlicons. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatov, L.K.; Radko, S.P.; Khmeleva, S.A.; Ptitsyn, K.G.; Timoshenko, O.S.; Lisitsa, A.V. Application of DETECTR for Selective Detection of Bacterial Phytopathogen Dickeya solani Using Recombinant CRISPR-Nuclease Cas12a Obtained by Single-Stage Chromatographic Purification. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2024, 60, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loop designation | Species* | Loop sequence (5' → 3') |

|---|---|---|

| Loop B | All | GGCGTCTCGCTCCTGAGCCTCCTGCTCGGGCAGCTCGTCTTCA |

| Loop F | Cs | GACTTGCGCACGTTCTCCACGATGATGCGCG |

| Ct | GACTTCCGCACGTGCTCGACGATGATGCGCG | |

| Cm | GGACTTCCGCACGTTCTCGACGATGATGCGCG | |

| Cn | GACTTCCGCACGTTCTCGACGATGATGCGCG | |

| Ci | GACTTCCGCACGTTCTCGACGATGATGCGCG | |

| Cp | GGACTTCCGCACGTTCTCGACGATGATGCGCG |

| Name | Sequence (5' → 3') |

|---|---|

| gRNA-B | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUCAGGAGGCUCAGGAGCGAGA |

| gRNA-F-14 | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUGGAGAACGUGCGCA |

| gRNA-F-16 | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUGUGGAGAACGUGCGCA |

| gRNA-F-18 | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUUCGUGGAGAACGUGCGCA |

| gRNA-F-20 | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUCAUCGUGGAGAACGUGCGCA |

| gRNA-F-22 | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUAUCAUCGUGGAGAACGUGCGCA |

| gRNA-F-24 | GGGAAUUUCUACUGUUGUAGAUGCAUCAUCGUGGAGAACGUGCGCA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).