1. Introduction

In conventional vector control systems designed for permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSM), speed and position sensors typically play an essential role. In a vast majority of industrial settings, mechanical sensors like photoelectric encoders or resolvers are employed to precisely detect the motor’s speed and pole position. Nevertheless, practical applications have revealed several drawbacks. The installation and replacement procedures of these sensors are often cumbersome, and the associated maintenance and utilization costs are considerably high. Such issues pose significant challenges in fulfilling the demands for simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and reliability in speed control systems, ultimately leading to a substantial increase in the overall system cost. Consequently, research on sensor-less control strategies for PMSM has garnered substantial attention from scholars both at home and abroad [

1,

2,

3].

Common PMSM sensor-less control strategies are as follows: (1) The application of the model reference adaptive method [

4,

5] strictly depends on the establishment of an accurate reference model. In case of an inaccurate reference model, the speed observation will be seriously distorted. This distortion directly undermines the system’s speed identification and deteriorates the control effect of the speed control system; (2) The extended Kalman filter (EKF) [

6,

7] demonstrates effective noise suppression and high estimation accuracy in nonlinear systems. However, its performance significantly degrades under motor parameter variations due to inherent linearization errors. The computational complexity arising from Jacobian matrix calculations and covariance propagation further limits its real-time applicability in high-dimensional systems. These characteristics constrain EKF’s practical deployment in scenarios requiring rapid parameter adaptation or strict timing constraints; (3) The flux observer-based speed estimation method [

8,

9] exhibits inherent limitations due to the absence of dedicated error compensation mechanisms, rendering it particularly susceptible to motor parameter variations (e.g., rotor resistance drift or inductance changes). This deficiency leads to significant estimation errors under dynamic operating conditions, thereby compromising system robustness and resulting in inferior anti-interference capabilities when subjected to parameter uncertainties or external disturbances. The lack of adaptive compensation for flux estimation discrepancies further exacerbates performance degradation in high-precision applications requiring rapid parameter adaptation; (4) The neural network-based observers face prominent real-time applicability challenges due to their inherent architectural limitations [

10,

11]. Specifically, the multi-layered network structure necessitates intricate forward propagation calculations, where the cumulative computation of weight matrix multiplications and activation function operations grows exponentially with the number of neurons and hidden layers. Meanwhile, the gradient-based update mechanisms, which are essential for model adaptation, require iterative backpropagation processes (including the computation of error gradients across all network layers and the adjustment of numerous parameters) to minimize estimation errors. These combined factors introduce prohibitive computational delays that frequently exceed the millisecond-scale latency requirements critical for time-sensitive applications such as high-speed motor control or real-time robotics, where even microsecond-level delays can lead to system instability or performance degradation.

In the realm of PMSM modeling, the inherent nonlinearity of its mathematical framework necessitates that the stability of observer design be prioritized as a fundamental challenge. Owing to the combined effects of motor parameter variations, load fluctuations, external disturbances, and measurement noise sensitivity, the system’s speed and position estimation algorithms must exhibit a requisite level of adaptivity to maintain robustness across diverse operating conditions. The Lyapunov-based adaptive observer design not only rigorously guarantees global asymptotic convergence of observation errors theoretically but also dynamically tracks motor parameter variations (e.g., stator resistance, flux amplitude) in real-time to suppress parameter drift, while effectively compensating for load torque fluctuations and measurement noise, thereby significantly enhancing robust estimation accuracy across diverse operating conditions [

12,

13]. Through rigorous theoretical analysis and comprehensive system simulations, this study demonstrates that the proposed Multi-dimensional Taylor Network (MTN) can serve as a viable alternative to conventional neural networks, offering superior capabilities in dynamic system modeling and control [

14,

15,

16]. Fundamentally, MTN is inherently a polynomial-type nonlinear auto-regressive moving average model, composed of a multitude of linear and nonlinear terms that can extend to infinity—this enables it to robustly represent state dynamics in a general sense, particularly for unstable systems, and provides an explicit description of system behavior. Specifically, the MTN surpasses traditional approaches by enabling more precise and resilient representations of complex nonlinear dynamics. Additionally, its simple structure and fast computing speed render it feasible for real-time control, as illustrated in

Table 1. Notably, the PID controller is a special case of the MTN controller, with its parameters serving as viable initial values for the latter, thereby enhancing the overall performance of observer-based estimation and control schemes for PMSM systems.

To conclude, this study addresses the state estimation challenge in PMSM systems by integrating the excellent approximation capability and adaptive characteristics of MTN. A nonlinear observer design approach for MTN-based PMSM systems is proposed, which systematically leverages MTN’s dynamic adaptive mechanisms to develop online adaptive learning rules suitable for complex nonlinear systems—thereby forming an observer architecture that balances approximation accuracy and robustness. Theoretically, through the construction of Lyapunov functions and rigorous mathematical derivation, the global asymptotic stability of the proposed observer in closed-loop systems and its effective state estimation capability for PMSM systems are proven. The findings demonstrate that this design framework, which merges intelligent network theory with control theory, provides a novel technical pathway to address model uncertainties and parameter time-variation issues in nonlinear system observer design.

2. PMSM State Space Model

To enable observer design, this section presents the transformation of the PMSM mathematical model from the coordinate system to the coordinate system. This conversion is achieved through a systematic coordinate transformation framework, which decouples the stator current components and enhances the observability of the system states. By leveraging the orthogonal properties of the coordinate system, the dynamic equations are recast into a canonical form suitable for advanced estimation techniques. The mathematical derivation involves constructing a transformation matrix that maps the original -frame variables to the -frame domain, ensuring the preservation of electromagnetic torque and flux linkages during the coordinate transformation. This methodological approach not only simplifies the observer design process but also provides a rigorous foundation for analyzing the stability and performance of the closed-loop control system.

The relationship between the

coordinate system and the

coordinate system is shown in Equation (1), where

and

are the

,

axis stator currents respectively;

is the rotor position.

The dynamic model of PMSM in the

coordinate system can be expressed by Equation (2), where

and

are the

,

shaft stator voltages respectively.

Set

,

,

as Equations (3)-(5) respectively, and perform coordinate transformation to express the system in state-space form, thereby obtaining Equation (6), where

,

are the known constant matrices which is observable with respect to

; the system inputs

,

and outputs

can be measured directly.

Using

to represent each variable, if

is observable, the velocity

and the position angle

can be expressed by Equation (7). So, the measurement of

and

can be transferred to the observation of

.

3. MTN Observer Design

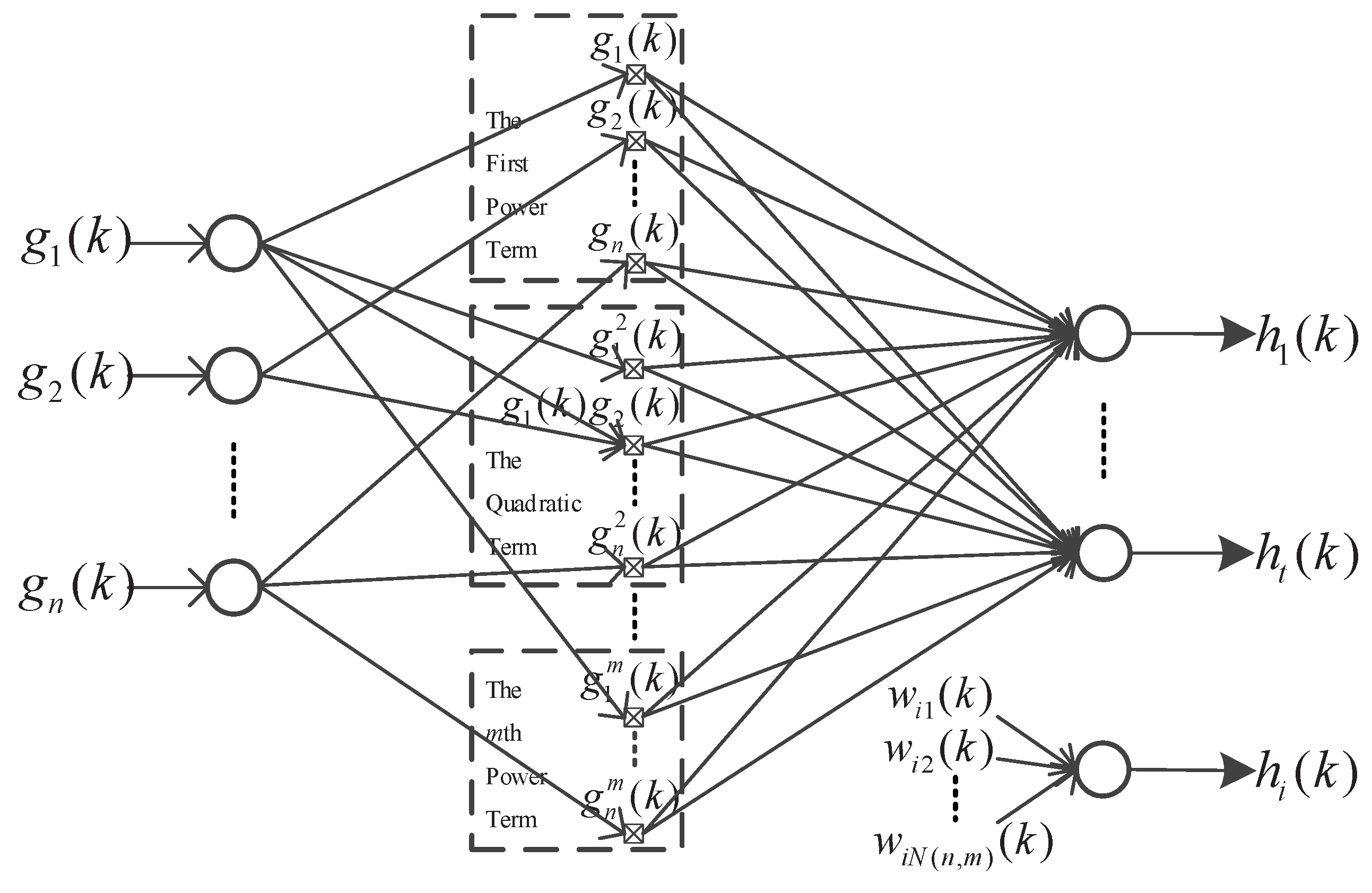

The MTN model is suitable for modeling general nonlinear systems with unknown mechanisms, as shown in

Figure 1. Based on the multiple-input multiple-output MTN model, the dynamical equations of the

n-dimensional nonlinear system can be described as shown in Equation (8), where

represents a nonlinear function described by the MTN model, with the basic idea of approximating a complex function by a simple one;

is the

p-th weight before each item;

is the total number of the expansion; and

is the power of

in the

p-th product term.

As shown in

Figure 1, the MTN model uses a forward single intermediate layer structure, if

is large enough, it can approximate arbitrary models with small accuracy [

17]. To highlight the enhanced real-time performance brought about by the MTN’s simple structure,

Table 1 compares the computational complexity of MTN and multi-layer perceptual neural network (MLPNN) in a single iteration [

18]. Furthermore, when

and

, the PID controller is a special form of the MTN. Therefore, the classical PID controller in the current loop can be directly replaced by an MTN controller with only first-order terms [

19].

In

Table 1,

represents the number of nodes in

-th layer of the MLPNN

, where

.

and

represent the number of nodes in the input and output layers of MLPNN and MTN, respectively, while

is the activation function of the neural nodes.

According to Equation (6), the MTN observer can be designed as Equation (9), where

is the constant gain matrix that makes the matrix

asymptotically stable.

,

and

are the observations of

,

and

, respectively.

Suppose there exists a vector function

such that

satisfies Equation (10) and also adheres to the Lyapunov Equation (11), where

and

are both positive definite matrices.

According to the MTN’s approximation property, the continuous vector function

in Equation (10) can be approximated by MTN. Assuming that the ideal weight of MTN is

and the approximation error vector is

, Equation (12) can be obtained, where

.

Let both and the approximation error be bounded, thus and .

Let the network estimate of

be

and its function estimation error be

, denoted as

,

. It can be known from the properties of

that

is bounded, and assuming

,

, the observer can be designed as Equation (13), while the dynamic equation of the estimation error

can be obtained as Equation (14). In Equation (14),

,

,

and

are the errors of the actual and observed values, respectively.

4. Stability Analysis of MTN Observer

This section will demonstrate the stability of the MTN network observer from a theoretical perspective. Combined with the Lyapunov stability theory, the learning rule of the MTN network weights can be designed as Equation (15). In Equation (15),

is the positive constant representing the regulation of convergence speed and

is the derived correction parameter formulated for the design.

Let the Lyapunov function be defined as

When , .

Combined with the theory of Lyapunov stability, both the state estimation error and the estimation error of MTN network weights are uniformly ultimately bounded.

5. MTN-Observer-Based Inverse Control Design

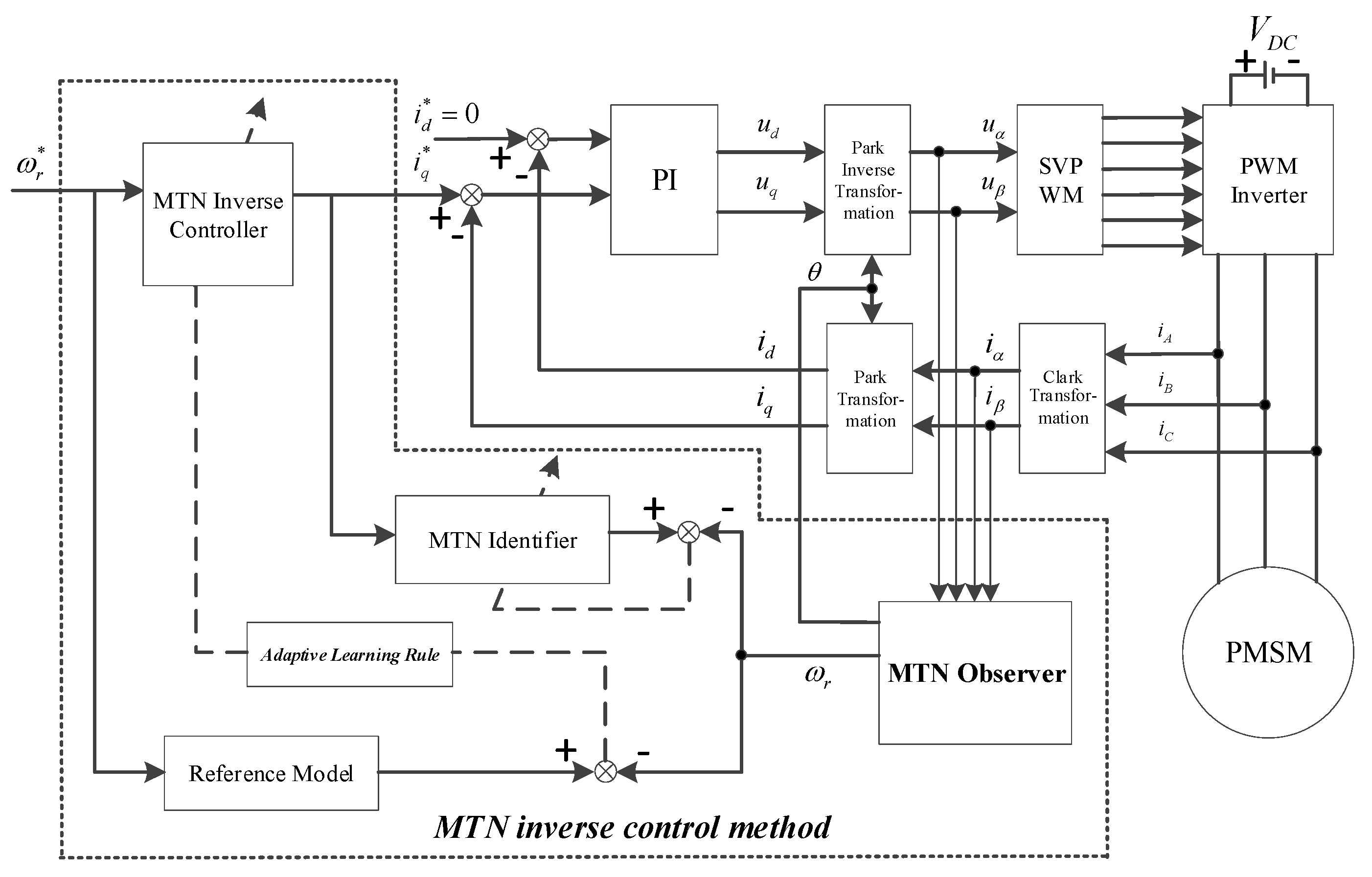

The overall scheme of MTN inverse control is shown in the dashed box within

Figure 2. Based on the full consideration of the PMSM particularity, this scheme designs a “special structure” which consists of three MTNs. One is the model identifier, which establishes the nonlinear time-varying dynamic model and provides the sensitivity information of the plant to the inverse controller; the other two are respectively adaptive inverse controller and adaptive nonlinear observer.

The main ideas of the scheme are listed as below:

In the adaptive system identification phase, the (online or offline) input-output data of time-varying object is used to train model identifier. And aiming at PMSM time-varying characteristics, the MTN identifier adopts the variable forgetting factor recursive least squares (VFF-RLS) algorithm [

19] to improve the identification ability, such as system recognition, convergence rate and the performance of learning algorithm.

In the adaptive inverse modeling phase, the error is used to train adaptive inverse controller by BPTM algorithm [

17]. Many people simply ignore this sensitivity and use the direct control approach, whereas others use the simple method of sign changes in the plant response as the sensitivity. However, in this paper, the MTN identifier is utilized to obtain the sensitivity, and along with the MTN inverse controller the weight adjustment becomes smoother than the case without the sensitivity information.

In addition, it should be noted that design of the off-line MTN inverse controller (off-line inverse modeling) is the leading stage of online adaptive controller design. This is mainly to address the problem of initial instability in adaptive control. Off-line experiments require a large number of training samples so as to enable the adaptive controller to cover the entire work range. Design of the off-line MTN inverse controller is implemented using the direct method [

14] as shown in

Figure 3, that is, the inverse model of the object is established directly by using its input-output data. To be specific, the output of the object is taken as the input of MTN so as to make the output of MTN approximate the object input. Its principle is very simple, but its training is not under the goal direction, so this structure can only be carried out offline.

In the adaptive nonlinear observer phase, the proposed method is detailed in

Section 3 and will not be repeated here for brevity.

6. Example Analysis

This section employs the MTN adaptive observer to enhance the PMSM speed regulation system, with benchmark analysis conducted to validate the effectiveness of the designed nonlinear observer.

Figure 2 illustrates the upgraded simulation system, where the speed loop control implements an MTN inverse control scheme while the current loop adopts a classical PI controller. The speed is set to 100

. The PMSM parameters are listed in

Table 2, which are consistent with those in [

20].

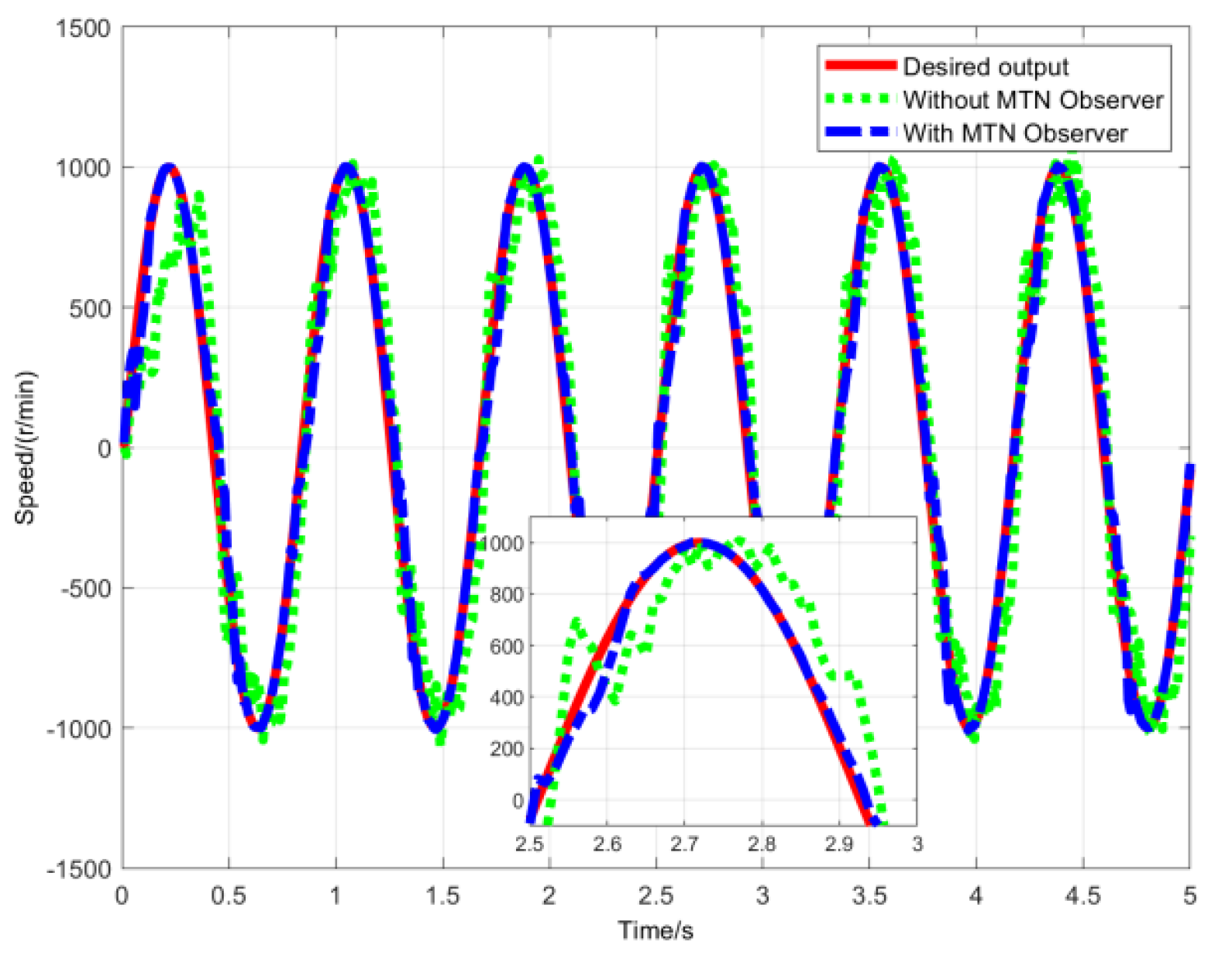

Figure 4 compares the speed responses during sinusoidal signal tracking for two control methods. The results demonstrate that the MTN-observer-based inverse control enables the PMSM speed servo system to achieve rapid yet stable tracking with better adaptability to load changes compared to the non-observer method. Additionally, steady-state operation shows virtually no static error, confirming precise speed control.

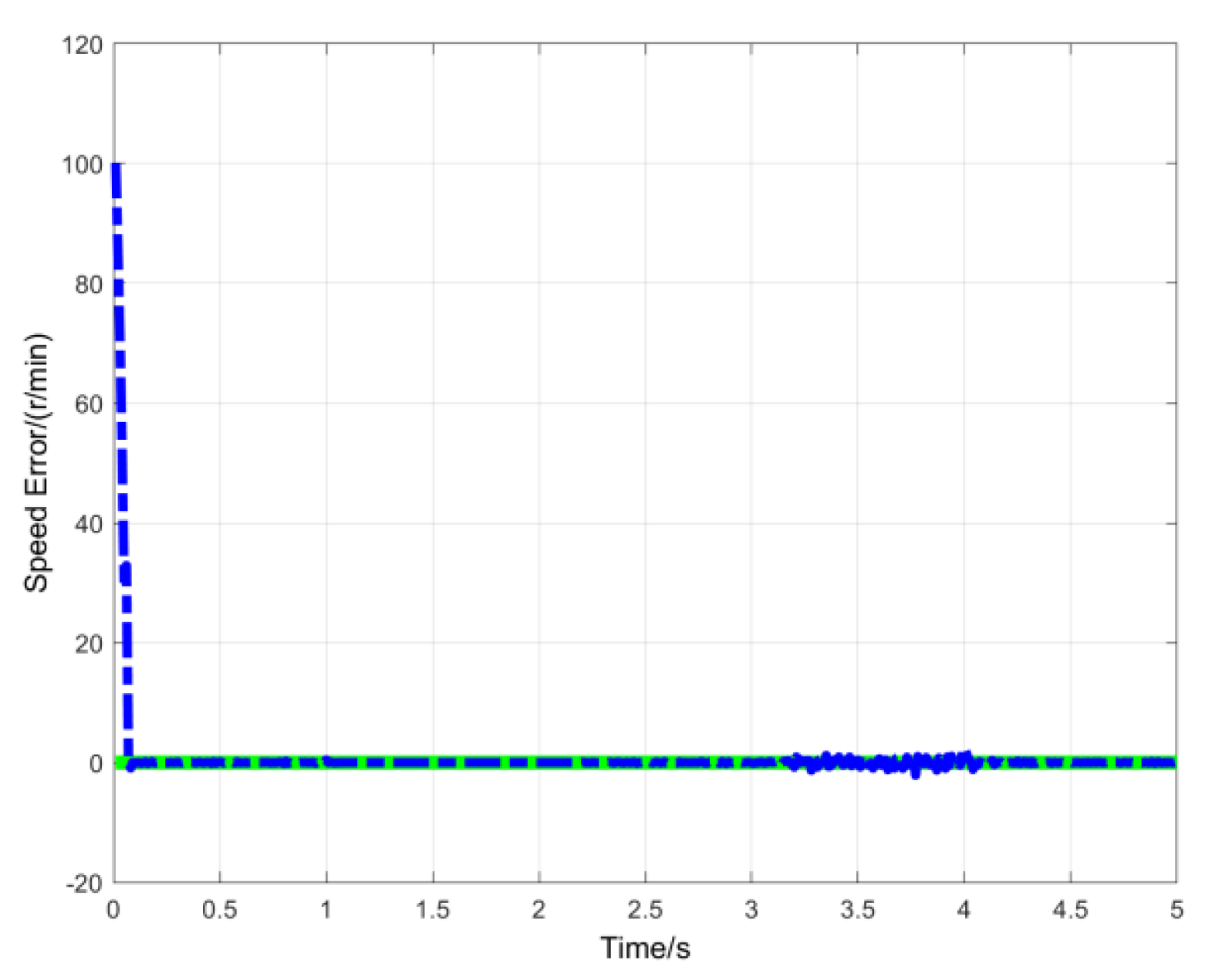

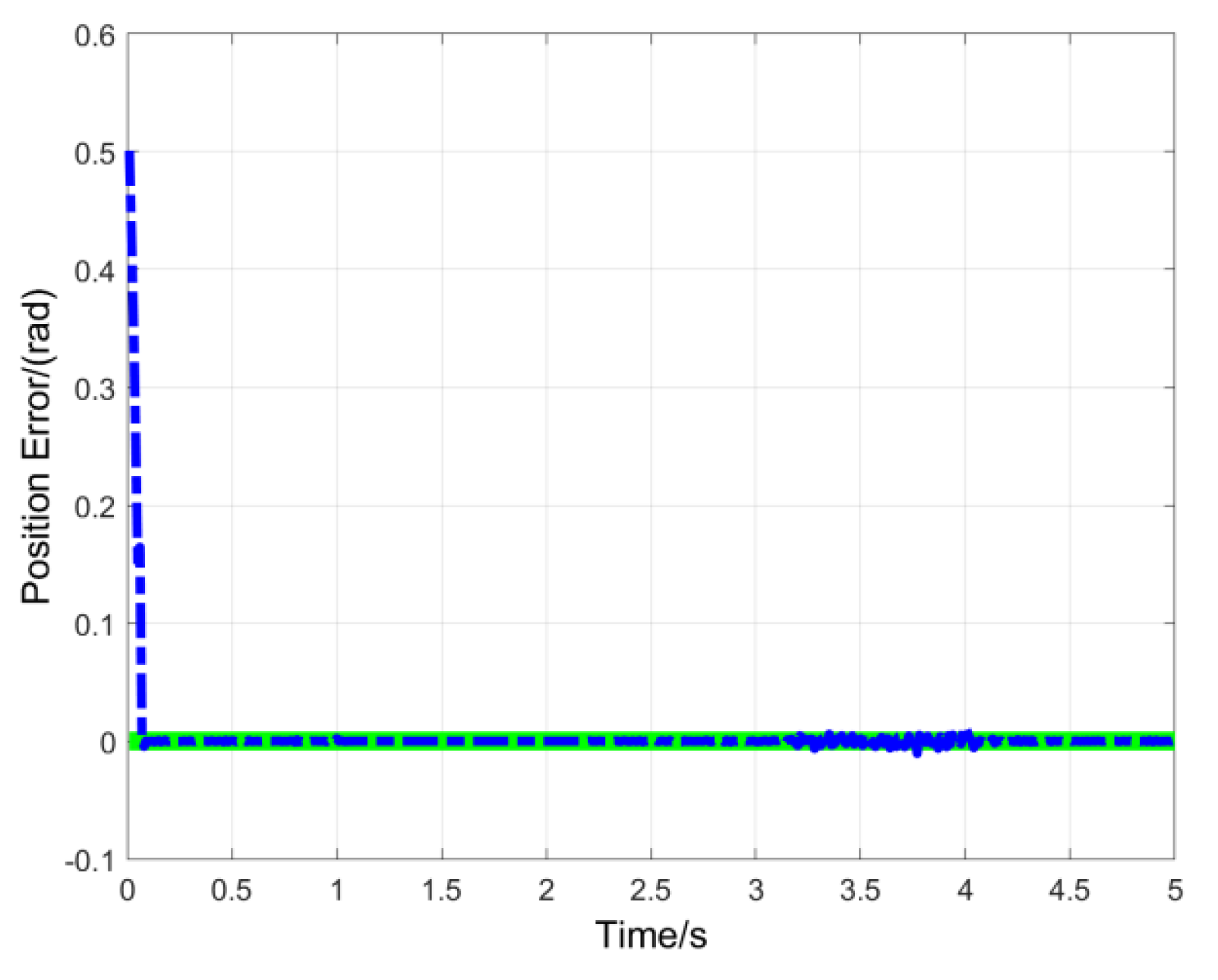

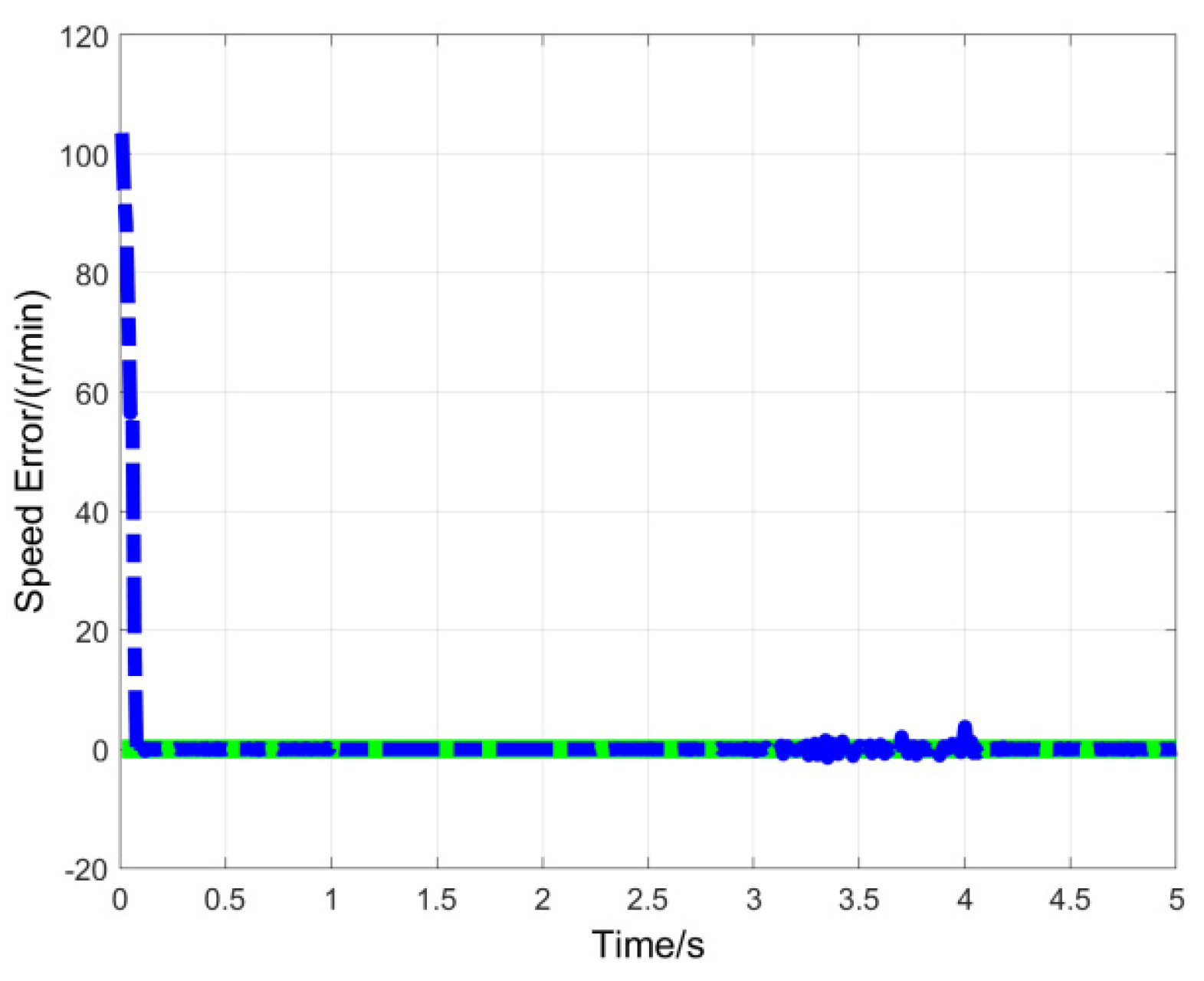

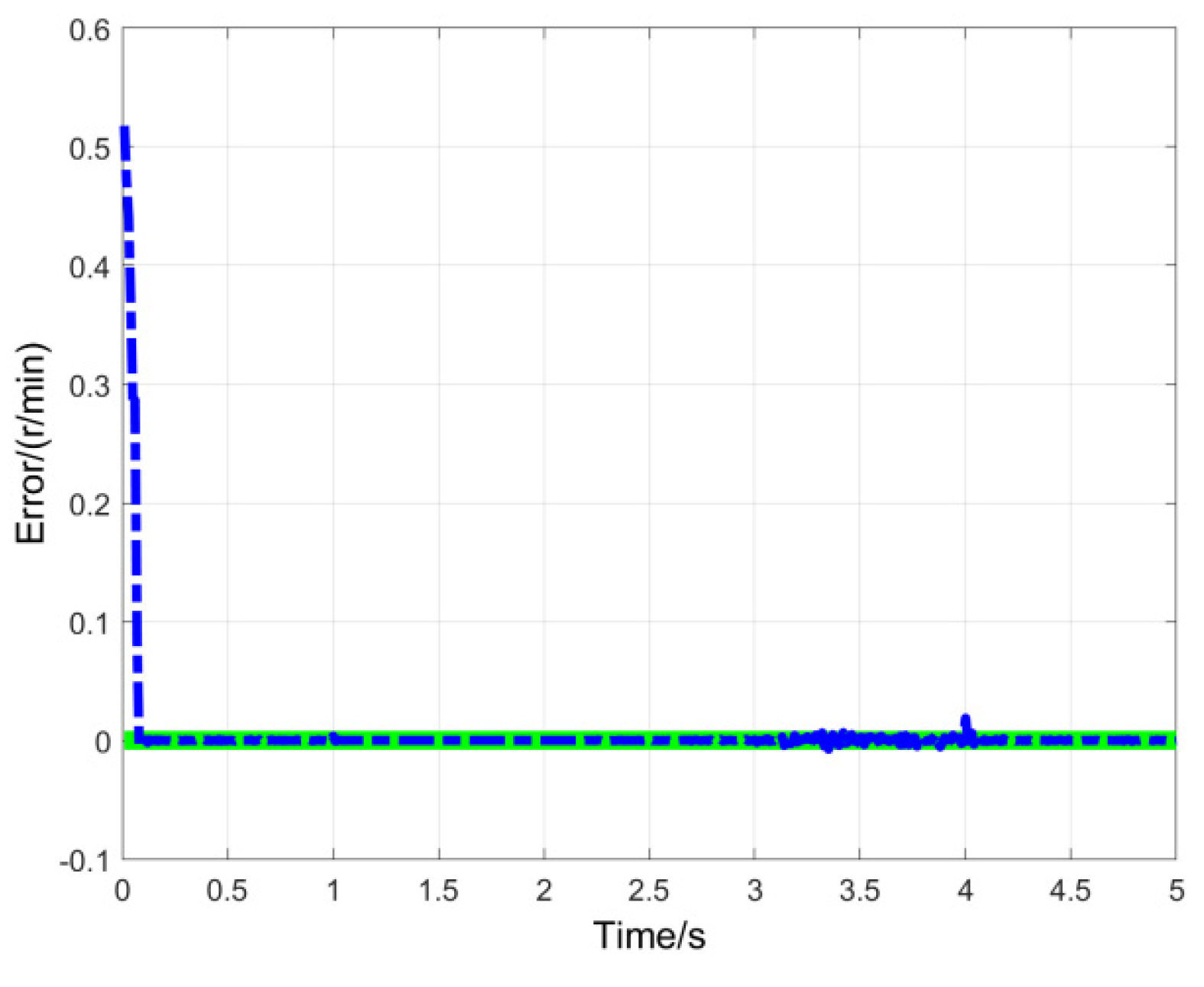

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 presents the observer estimation results for the PMSM speed control system under preset parameters. After modifying the parameters with a tenfold increase in

, the observer estimation results are demonstrated in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The system simulation results confirm that the proposed MTN observer achieves high-fidelity parameter estimation in the PMSM system, rapidly converging to the true values after a brief transient state while exhibiting strong robustness against motor parameter variations and external disturbances.

7. Conclusions

For the PMSM speed control system, a novel MTN-based nonlinear observer method is proposed. By integrating the Lyapunov stability theory, an online learning rule for MTN weights is designed, with the convergence stability of the MTN-based state observer rigorously proven. Quantitative simulation results demonstrate that the MTN observer achieves high estimation accuracy, exhibits strong robustness rejection and delivers satisfactory computational efficiency in real-time implementations.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province under Grant 252102211073, the Research and Practice Project on Higher Education Teaching Reform of Henan Province under Grant 2024SJGLX0557, the College Youth Backbone Teacher Fund of Henan Province under Grant 2023GGJS182, the College Model Course and Teaching Team of Henan Province under Grant Jiao-Gao [2023] 431, the Special Research Project on Smart Teaching in Undergraduate Universities of Henan Province under Grant Jiao-Gao [2023] 334, the Open Project of Henan Key Laboratory of Cable Advanced Materials and Intelligent Manufacturing under Grant CAMIM202505.

References

- Zhang, L.; Deng, S.S.; Zhu, X.Y.; Xiang, Z.X. New Flux Intensifying Technique for Five-Phase Fault-Tolerant Interior Permanent Magnet Motors Under Multiple Sensorless Operation. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2024, 71(11): 13801‐13811. [CrossRef]

- Teymoori, V.; Kamper, M.; Wang, R.J.; Kennel, R. Sensorless Control of Dual Three-Phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines-A Review. Energies, 2023, 16(3): 1326‐1346. [CrossRef]

- Minchala-Ávila, C.; Arévalo, P.; Ochoa-Correa, D. A Systematic Review of Model Predictive Control for Robust and Efficient Energy Management in Electric Vehicle Integration and V2G Applications. Modelling, 2025, 6(1): 20. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.X.; Wang, D.Z. A Hybrid Filtering Stage-Based Rotor Position Estimation Method of PMSM with Adaptive Parameter. Sensors, 2021, 21(14): 4667‐4684. [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.L.; Liu, J.L.; Mai, Z.Q.; Xiao, F.; Li, S. Optimization of Sensorless Control Performance for a Low-Switching Frequency Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive System. Journal of Electrical Engineering and Technology, 2024, 19(4): 2323‐2336. [CrossRef]

- Zwerger, T.; Mercorelli, P. Backward Extended Kalman Filter to Estimate and Adaptively Control a PMSM in Saturation Conditions. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Industrial Electronics, 2023, 5(2): 462‐474. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Garcia-Hernandez, R.; Jurado, F. Modeling, Simulation, and Control of a Rotary Inverted Pendulum: A Reinforcement Learning-based Control Approach. Modelling, 2024, 5(4): 1824‐1852. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Zhang, Y.C. Performance Improvement of Nonlinear Flux Observer for Sensorless Control of PMSM. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2023, 70(12): 12014‐12023. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Song, W.Z.; Yang, Y.; Wheeler, P. A Polar-Coordinate-Multisignal-Flux-Observer-Based PMSM Non-PLL Sensorless Control. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 2023, 38(9): 10579‐10583. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z.; Naqvi, S.A.Z.; Khan, Y.A.; Hamayun, M.T.; Ljaz, S. Design and Experimental Validation of an Adaptive Multi-Layer Neural Network Observer-Based Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control for Quadrotor System. Aerospace, 2024, 11(10): 788‐810. [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.D.; Ma, T.N.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Z.X. Design and Implementation of an Adaptive Neural Network Observer–based Backstepping Sliding Mode Controller for Robot Manipulators. Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, 2024, 46(6): 1093‐1104. [CrossRef]

- Boumegouas, M.K.B.; Ilten, E.; Kouzi, K.; Demirtas, M.; M’hamed, B. ;. Application of a Novel Synergetic Observer for PMSM in Electrical Vehicle. Electrical Engineering, 2024, 106(5): 5507‐5521. [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Chen, H.X.; Zhang, M.M.; Wu, M.Y. Prediction Error Compensation Method of FCSMPC for Converter based on Neural Network. Journal of Power Electronics, 2024, 24(12): 2022‐2035. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, H.S. Multidimensional Taylor Network Adaptive Control for MIMO Time-varying Uncertain Nonlinear Systems with Noises. International journal of robust and nonlinear control, 2020, 30(1):397‐420. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.M.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, N.Y.; Yu, J.J.; Xu, L. Data-driven Nonlinear Near-optimal Regulation based on Multi-dimensional Taylor Network Dynamic Programming, IEEE Access, 2020, 8(1): 36476-36484. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L.; Yan, H.S.; Zhang, C. Recursive d-step-ahead Predictive Control of MIMO Nonlinear Systems with Input Time-delay via Multi-dimensional Taylor Network Extended from PID, Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, 2024, 46(6): 1038-1057. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.S.; Zhang, C. Inverse Control of Single-Input/Single-Output Nonlinear Time-varying Systems with Noise Disturbances by Multi-dimensional Taylor Network, Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, 2020, 42(13): 2450-2464. [CrossRef]

- Patra, J.C.; Kot, A.C. Nonlinear Dynamic System Identification using Chebyshev Functional Link Artificial Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics, 2002, 32(4): 505‐511. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, H.S. Identification and Adaptive Multi-dimensional Taylor Network Control of Single-input Single-output Non-linear Uncertain Time-varying Systems with Noise Disturbances. IET Control Theory and Applications, 2019, 13(6): 841‐853.

- Zhang, C.; Yan, H.S. Inverse Control of Multi-dimensional Taylor Network for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor, COMPEL-The international journal for computation and mathematics in electrical and electronic engineering, 2017, 36(6): 1676-1689.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).