Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

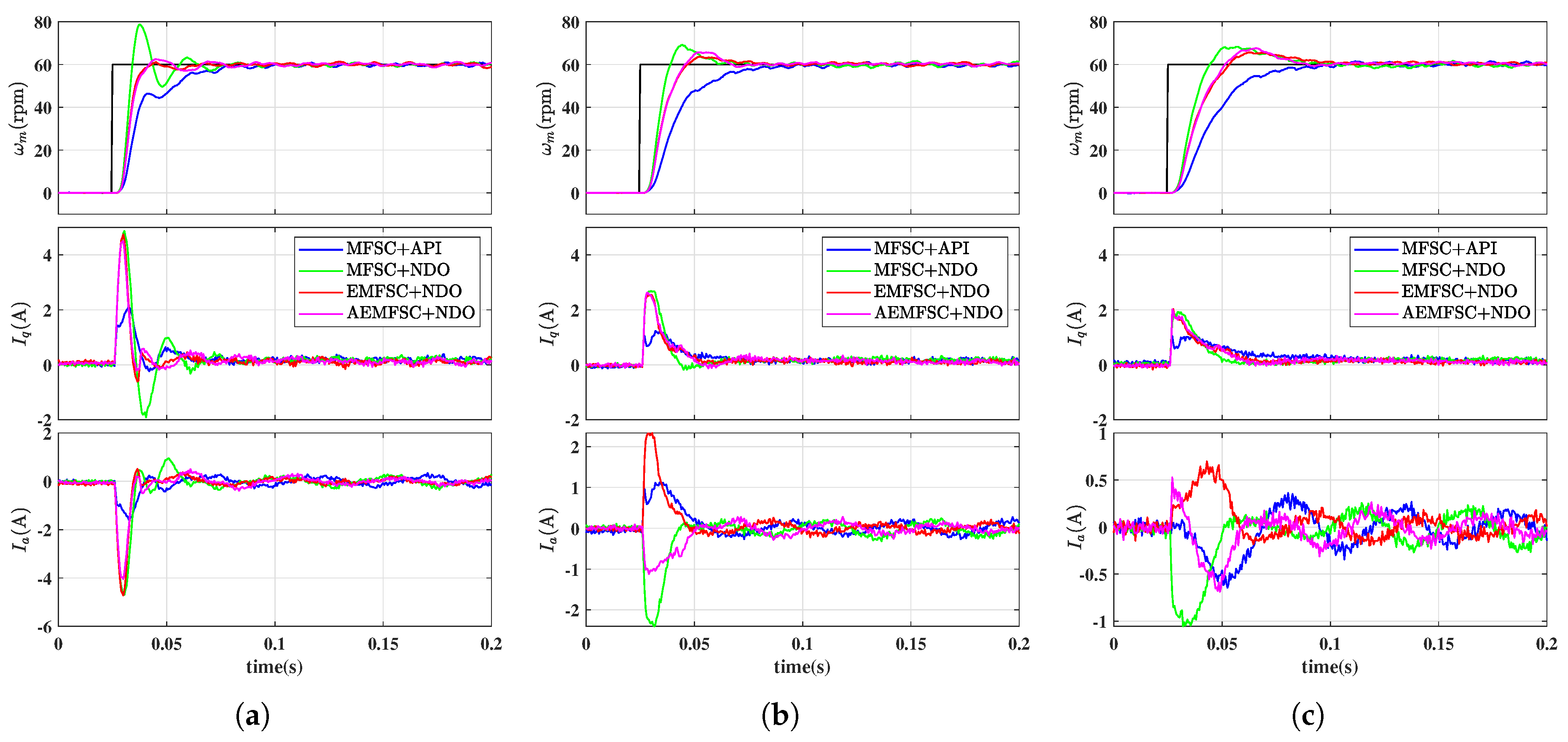

- Compared to conventional lumped disturbance estimation methods, the incorporation of NDO eliminated steady-state errors caused by load torque variations. The integration of PD control law into the generalized model-free controller effectively reduced speed overshoot, while the dead-zone method mitigated control signal oscillations induced by sensor noise.

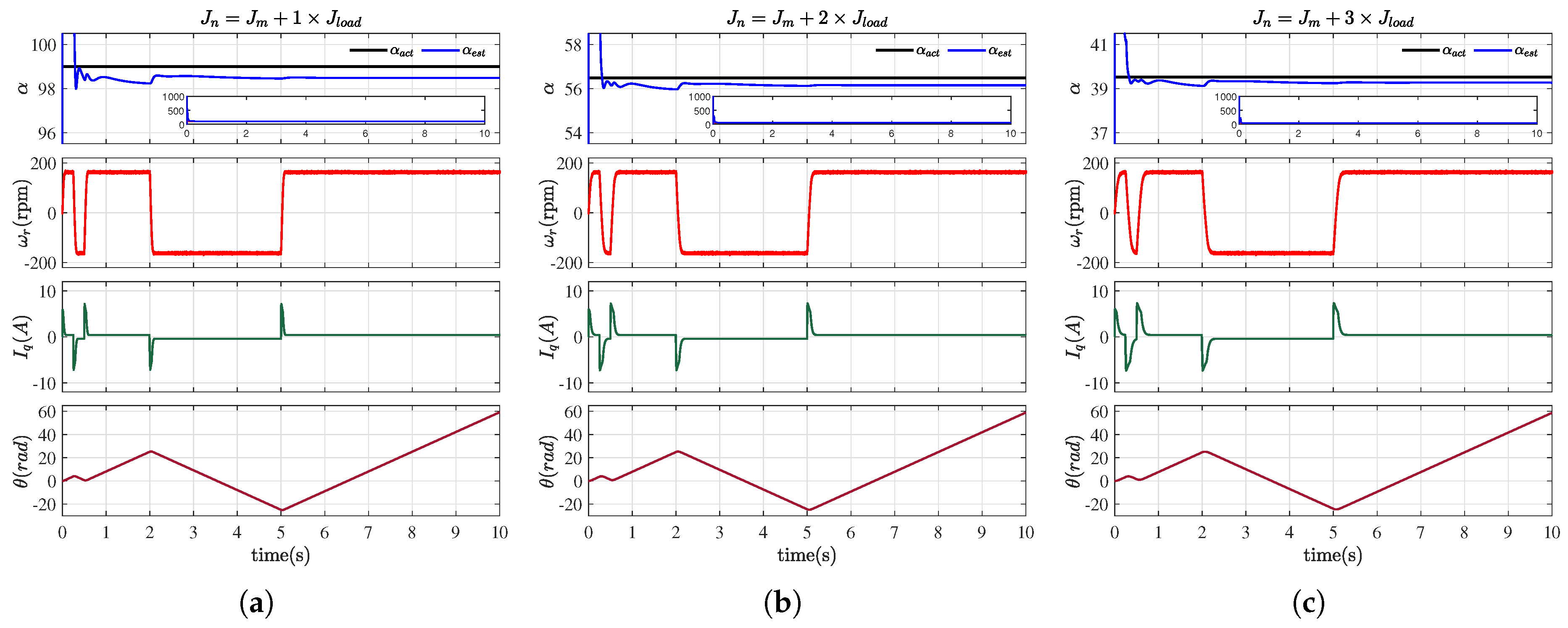

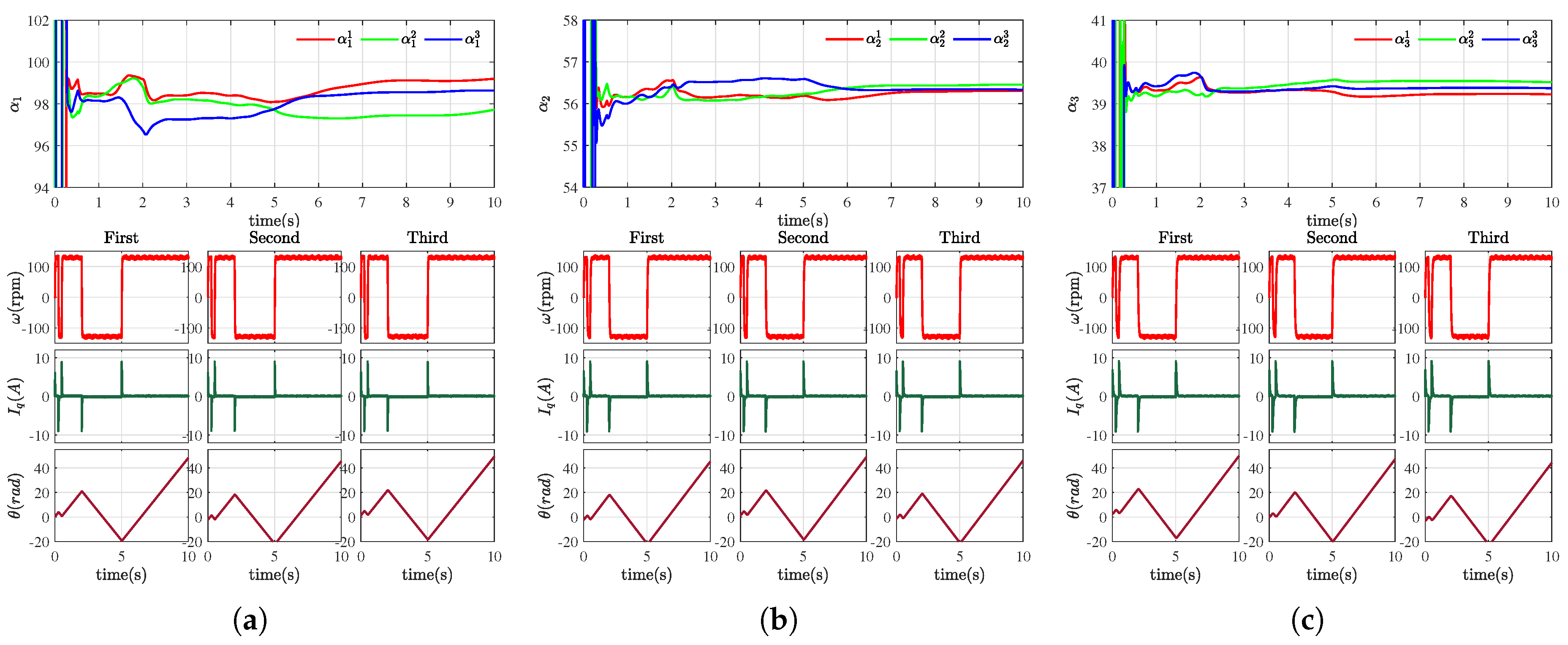

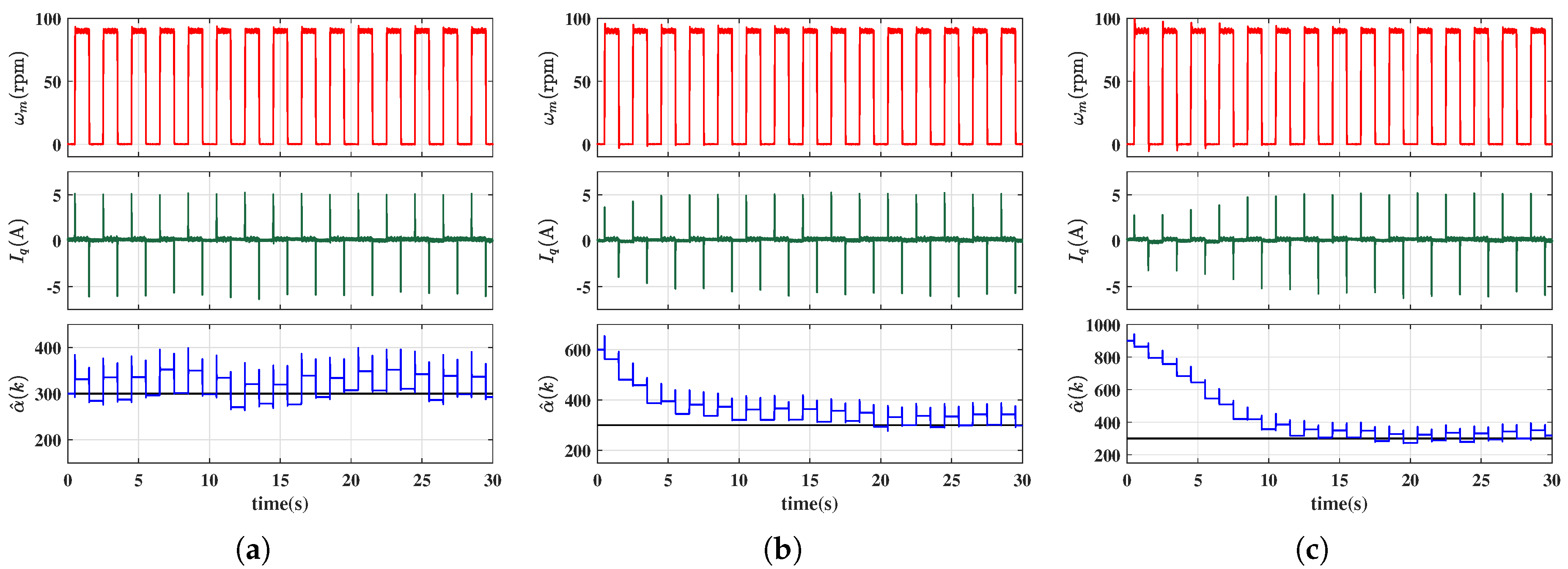

- The proposed online adaptive estimation law ensured rapid convergence to the true value, significantly improving speed tracking accuracy.

- The algebraic framework-based linear parameter identification method enabled high-precision estimation of the true value, eliminating arbitrariness in initial value selection and enhancing transient performance during startup phases.

2. Conventional Model-Free Speed Control Based on Ultra-local Model

2.1. Mathematical Model of SMPMSM Direct Drive System

2.2. Principle of Conventional ULM-Based Model-Free Control

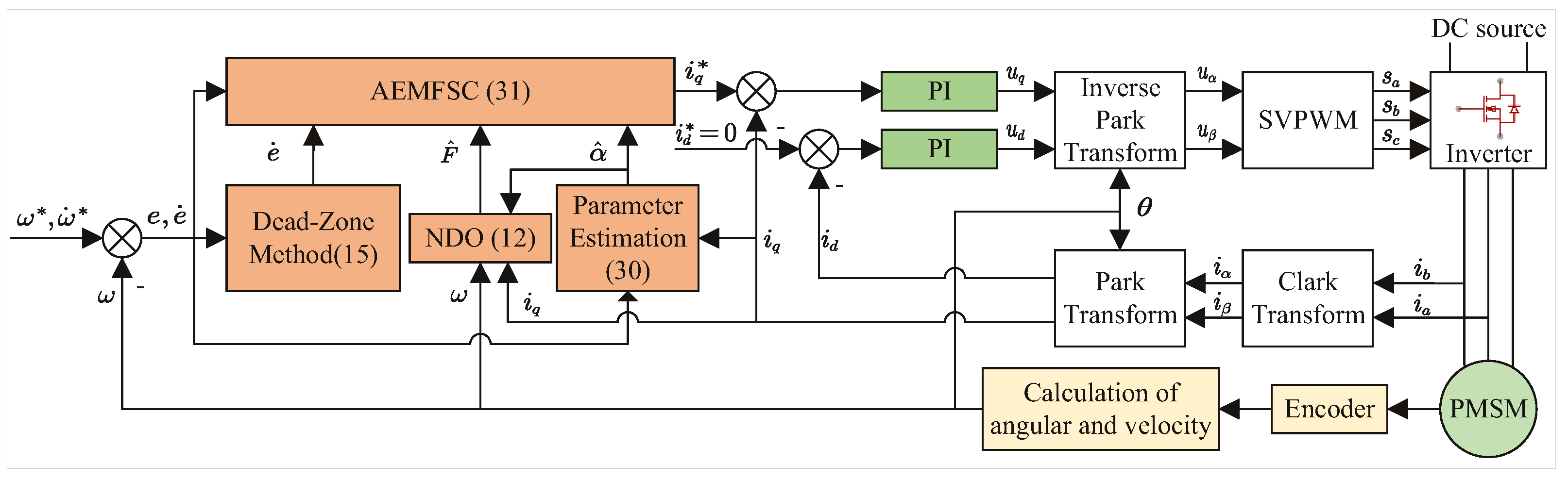

3. Principle of the Proposed AEMFSC-NDO

3.1. Enhanced Model-Free Speed Control via Nonlinear Disturbance Observer

3.2. Adaptive Enhanced Model-Free Speed Controller Design

3.3. Initial Value Estimation Method for the Input Gain

4. Simulation and Experimet Results

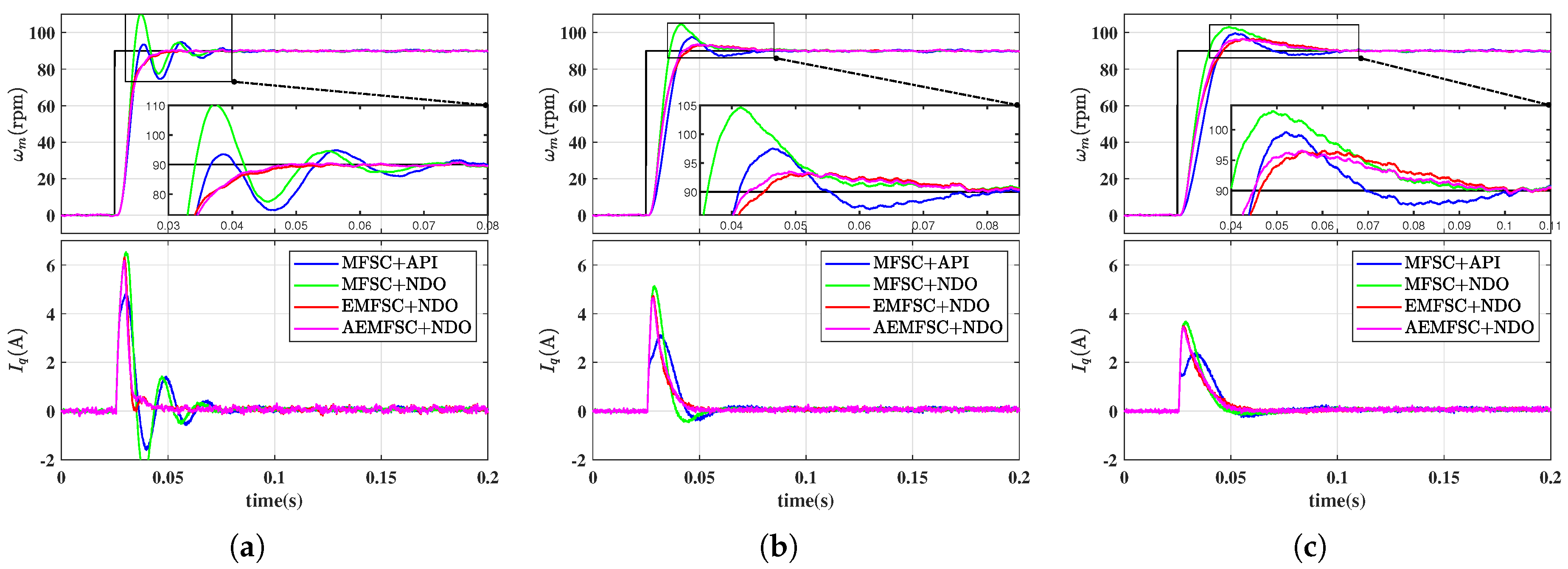

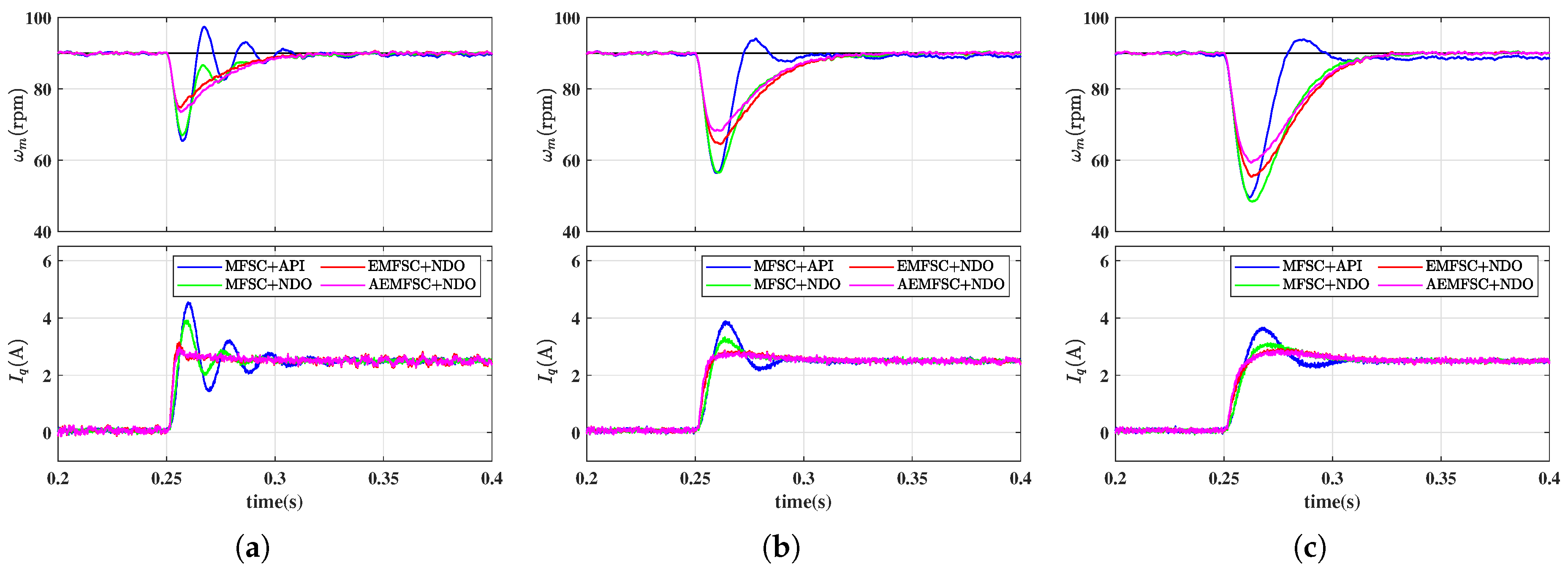

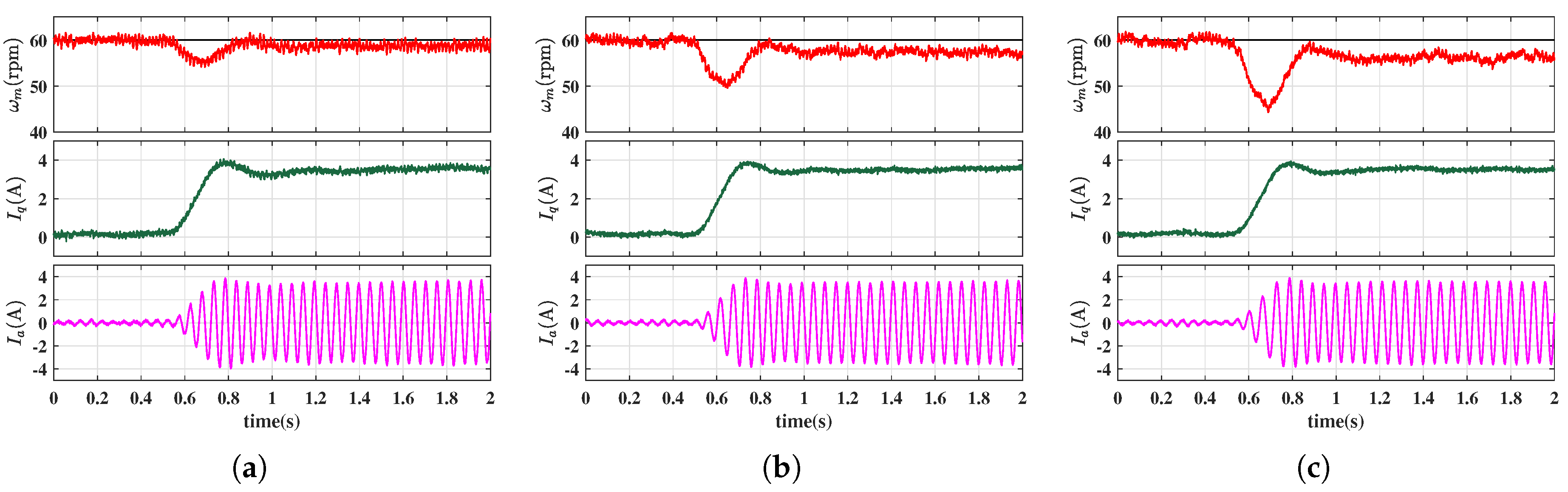

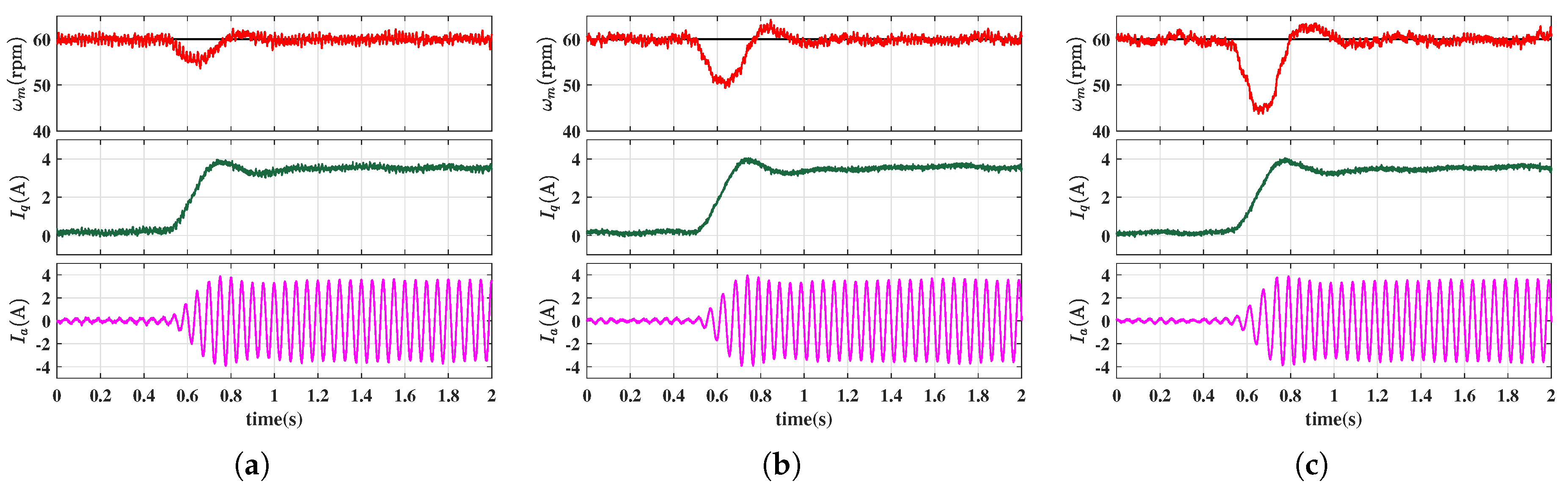

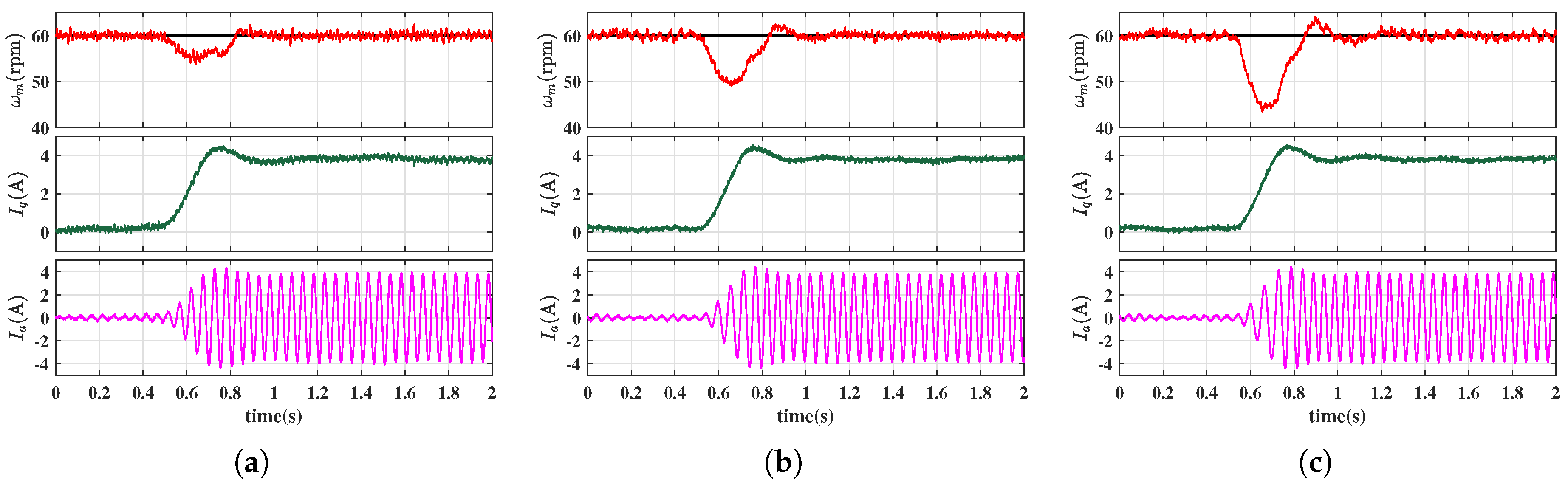

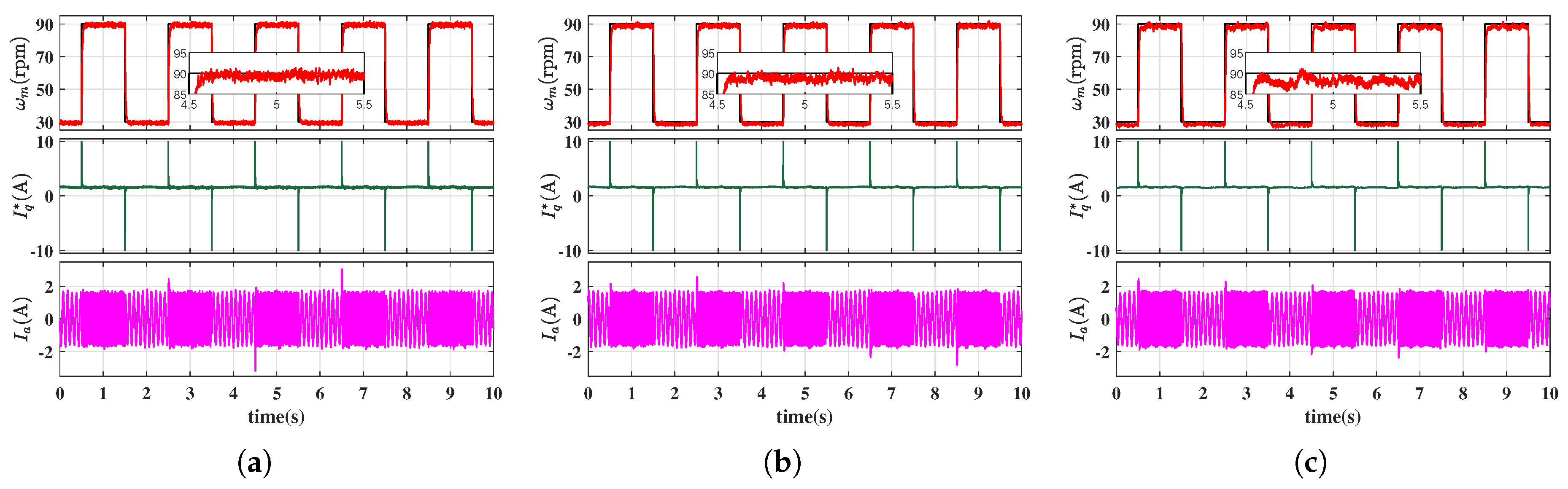

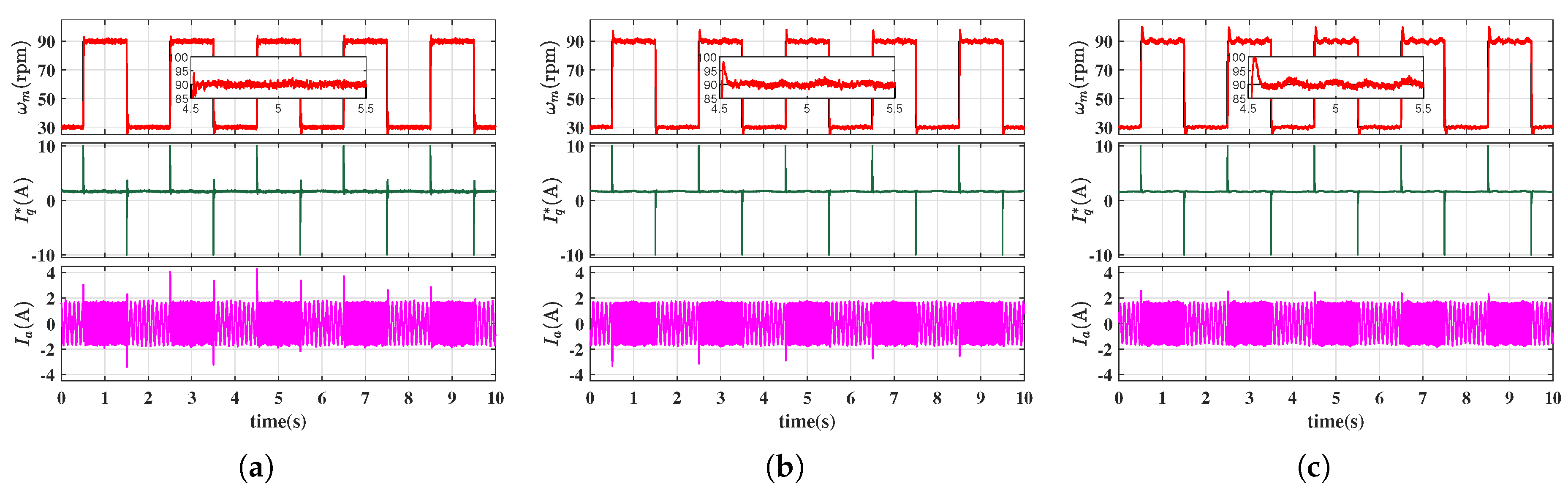

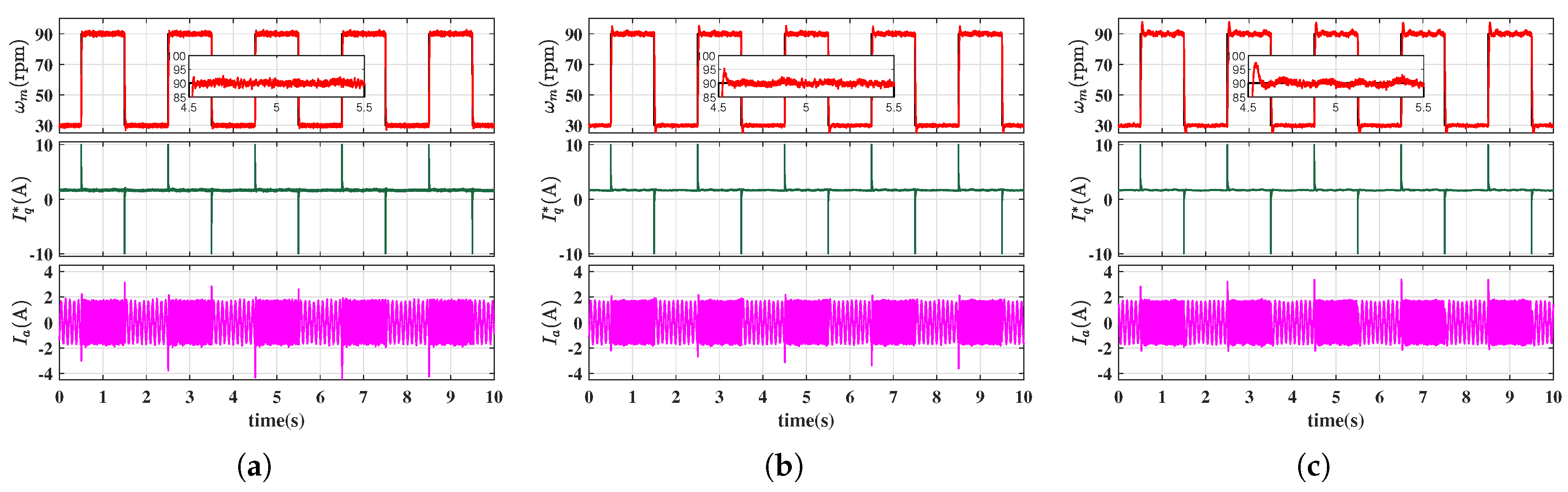

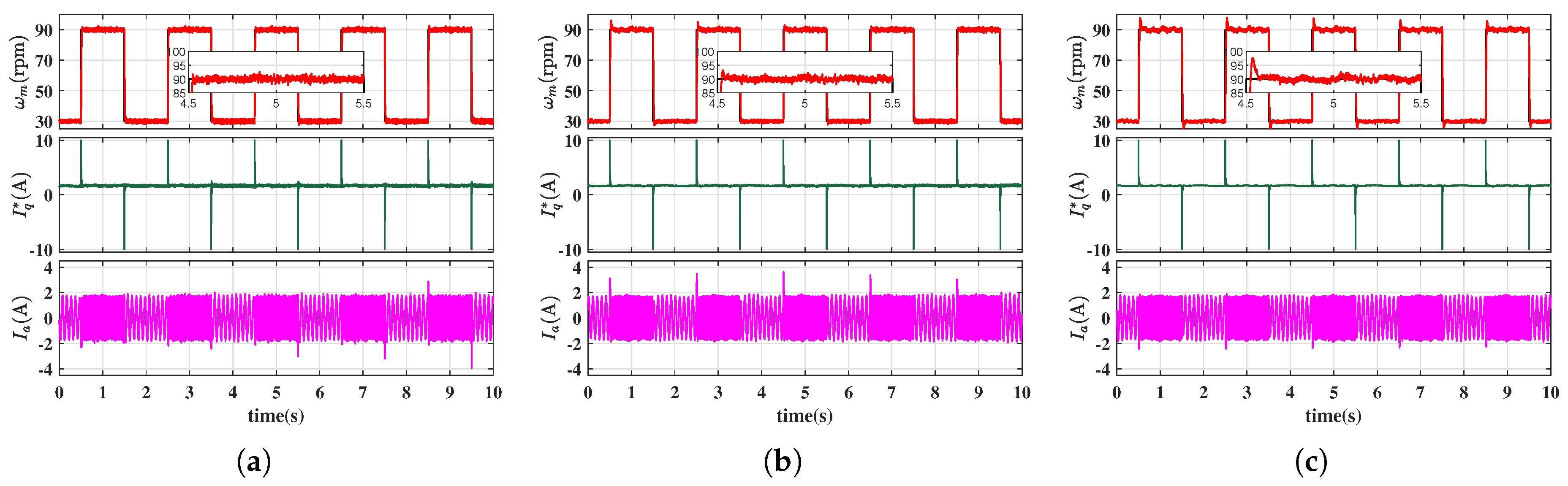

4.1. Simulation Results

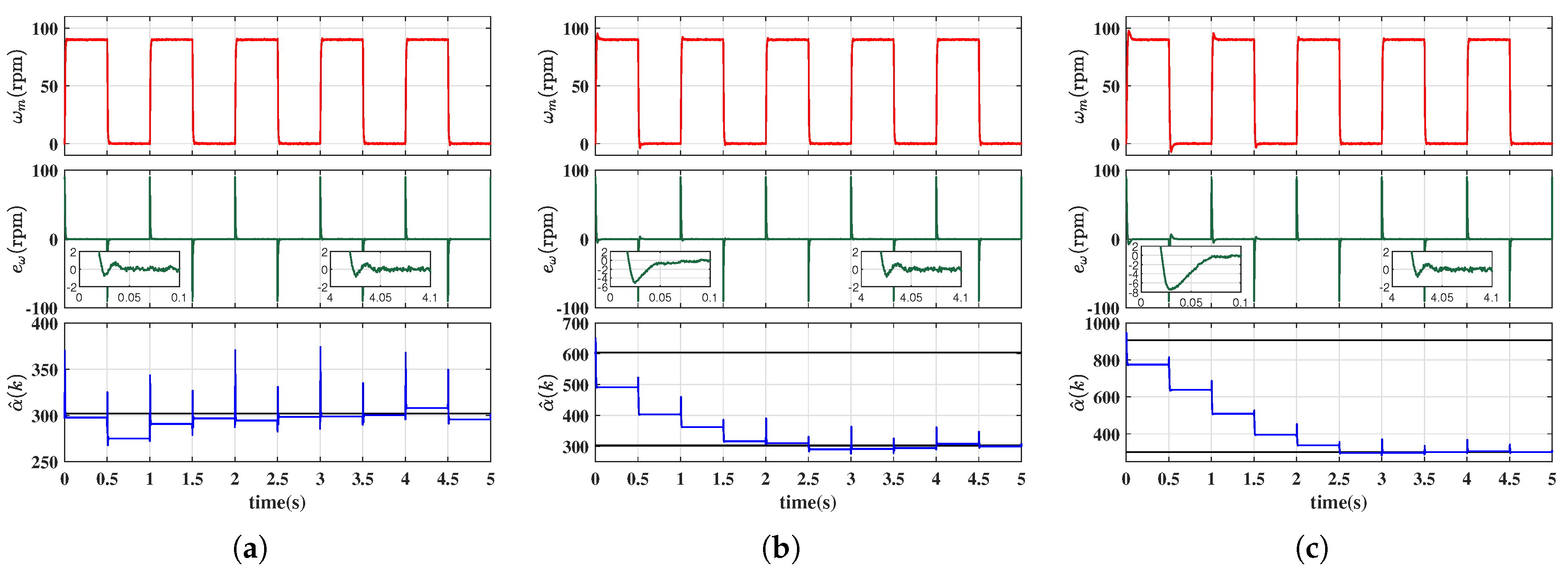

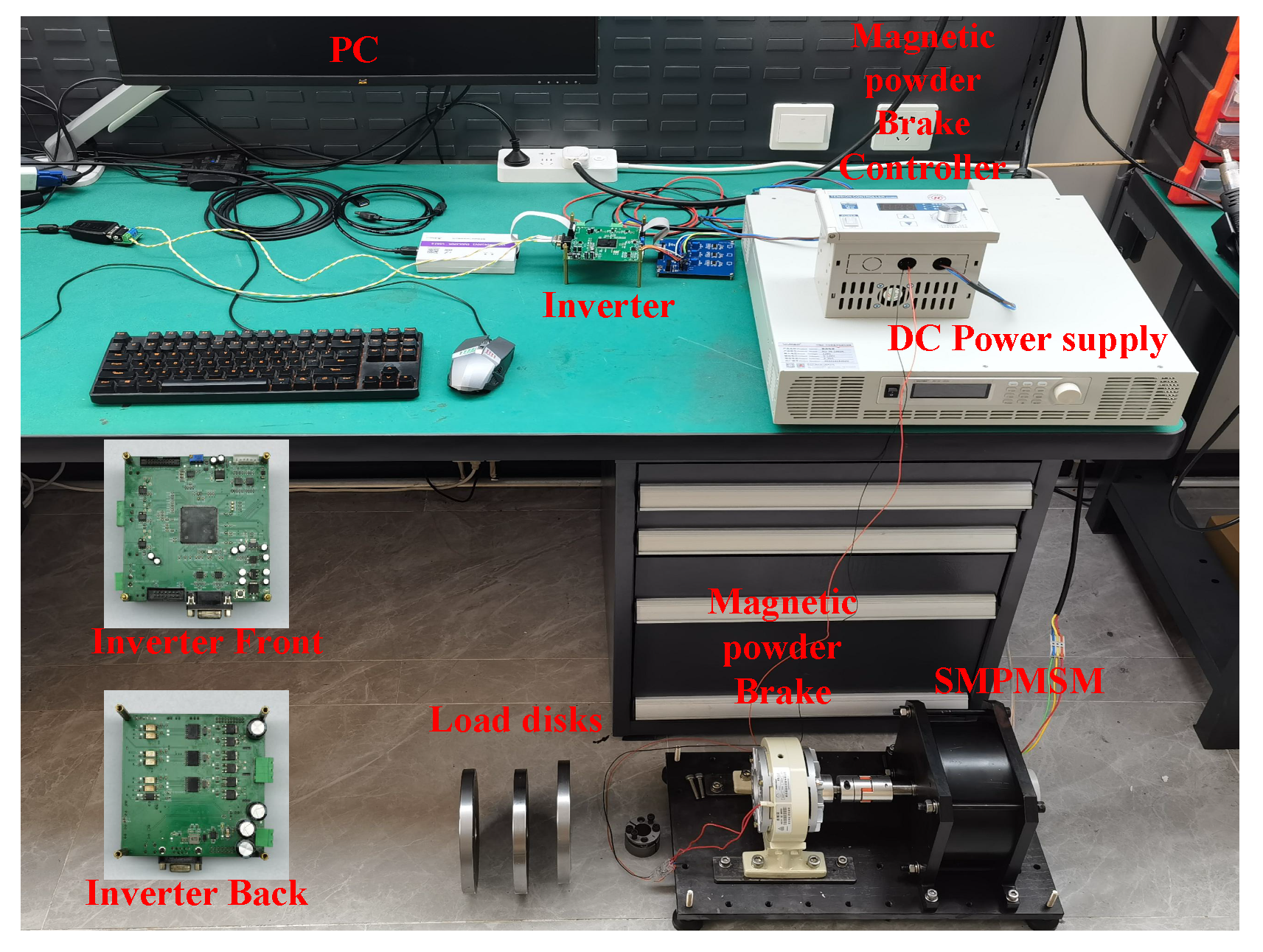

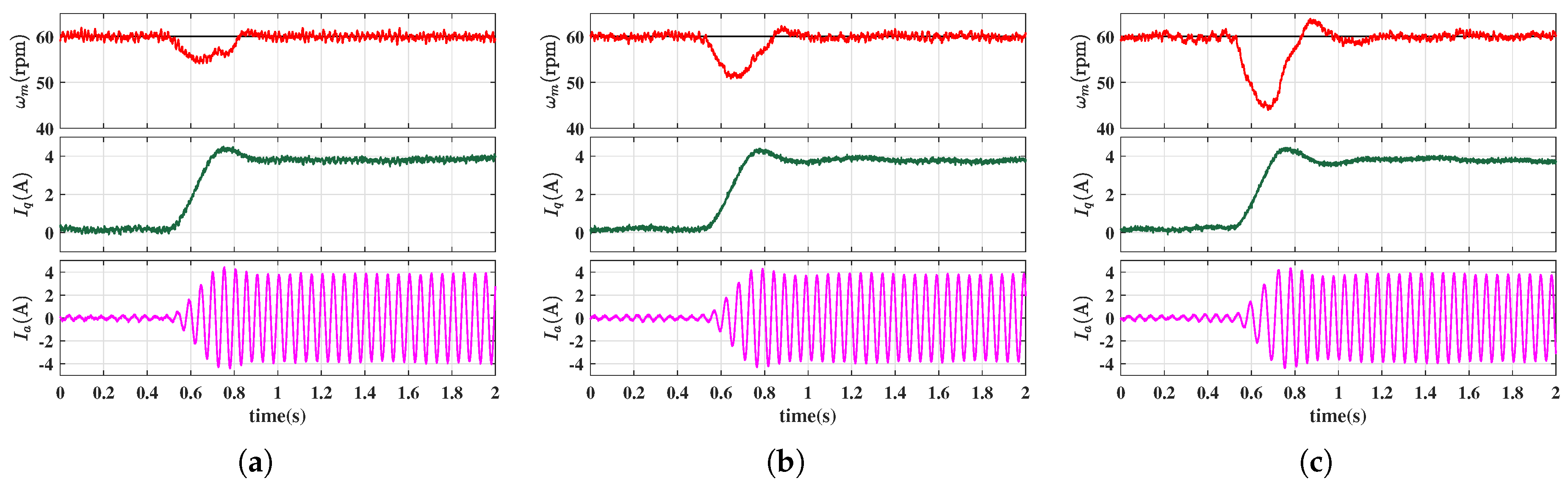

4.2. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aimeng, W.; Heming, L.; Pengwei, S.; Yi, W.; Shuting, W. Dsp-Based Field Oriented Control of PMSM Using SVPWM in Radar Servo System. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Electric Machines and Drives, 2005., 2005, pp. 486–489.

- Apte, A.; Thakar, U.; Joshi, V. Disturbance Observer Based Speed Control of PMSM Using Fractional Order PI Controller. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2019, 6, 316–326.

- Sarsembayev, B.; Suleimenov, K.; Do, T.D. High Order Disturbance Observer Based PI-PI Control System With Tracking Anti-Windup Technique for Improvement of Transient Performance of PMSM. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 66323–66334.

- Li, Y.; Ping, Z.; Huang, Y.; Lu, J.G. An Internal Model Approach for Speed Tracking Control of PMSM Driven Electric Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Control & Automation (ICCA), 2020, pp. 1416–1421.

- Ding, S.; Hou, Q.; Wang, H. Disturbance-Observer-Based Second-Order Sliding Mode Controller for Speed Control of PMSM Drives. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2023, 38, 100–110.

- Choi, H.H.; Leu, V.Q.; Choi, Y.S.; Jung, J.W. Adaptive Speed Controller Design for a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IET Electric Power Applications 2011.

- Choi, H.H.; Yun, H.M.; Kim, Y. Implementation of Evolutionary Fuzzy PID Speed Controller for PM Synchronous Motor. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2015, 11, 540–547.

- Ahmed, A.A.; Koh, B.K.; Lee, Y.I. A Comparison of Finite Control Set and Continuous Control Set Model Predictive Control Schemes for Speed Control of Induction Motors. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 14, 1334–1346.

- Wang, B.; Shao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Dong, Q.; Yun, Z.; Xu, D. High-Order Terminal Sliding-Mode Observer for Chattering Suppression and Finite-Time Convergence in Sensorless SPMSM Drives. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2021, 36, 11910–11920.

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Cheung, N.C.; Pan, J. Enhanced Sliding Mode Control for PMSM Speed Drive Systems Using a Novel Adaptive Sliding Mode Reaching Law Based on Exponential Function. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2024, 71, 11978–11988.

- Sastry, S.; Bodson, M. Adaptive Control: Stability, Convergence and Robustness; Courier Corporation, 2011.

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Nie, B.; Liu, Y.; He, X. Adaptive Control of PMSM Servo System for Steering-by-Wire System With Disturbances Observation. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2022, 8, 2015–2028.

- Chen, W.H.; Yang, J.; Guo, L.; Li, S. Disturbance-Observer-Based Control and Related Methods—An Overview. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2016, 63, 1083–1095.

- Ohishi, K.; Nakao, M.; Ohnishi, K.; Miyachi, K. Microprocessor-Controlled DC Motor for Load-Insensitive Position Servo System. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 1987, IE-34, 44–49.

- Yan, Y.; Yang, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Yu, H. Non-Linear-Disturbance-Observer-Enhanced MPC for Motion Control Systems with Multiple Disturbances. IET Control Theory & Applications 2020, 14, 63–72.

- Dai, C.; Guo, T.; Yang, J.; Li, S. A Disturbance Observer-Based Current-Constrained Controller for Speed Regulation of PMSM Systems Subject to Unmatched Disturbances. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 68, 767–775.

- Han, J. From PID to Active Disturbance Rejection Control. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2009, 56, 900–906.

- Zhiqiang Gao. Scaling and Bandwidth-Parameterization Based Controller Tuning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2003 American Control Conference, 2003., Denver, CO, USA, 2003; Vol. 6, pp. 4989–4996.

- Qu, L.; Qiao, W.; Qu, L. An Extended-State-Observer-Based Sliding-Mode Speed Control for Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics 2021, 9, 1605–1613.

- El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Amin, M.M.; Soliman, A.S.; Mohammed, O.A. Optimal Adaptive Ultra-Local Model-Free Control Based-Extended State Observer for PMSM Driven Single-Axis Servo Mechanism System. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 60, 7728–7745.

- Fliess, M.; Join, C. Model-Free Control. International Journal of Control 2013, 86, 2228–2252.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Yao, H. Model-Free Control of Surface Mounted PMSM Drive System. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Taipei, Taiwan, 2016; pp. 175–180.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Mao, J.; Huang, J. Model Free Deadbeat Predictive Speed Control of Surface-Mounted Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive System. Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology 2019, 14, 265–274.

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, J.; Huang, L. Model-Free Predictive Current Control of PMSM Drives Based on Extended State Observer Using Ultralocal Model. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 68, 993–1003.

- Yuan, X.; Zuo, Y.; Fan, Y.; Lee, C.H.T. Model-Free Predictive Current Control of SPMSM Drives Using Extended State Observer. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2022, 69, 6540–6550.

- Wu, X.; Zou, P.; Huang, S.; Yang, M.; Wu, T.; Huang, S.; Cui, H. Model-Free Predictive Current Control of SPMSM Based on Enhanced Extended State Observer. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2024, 71, 3461–3471.

- Fliess, M.; Join, C. An Alternative to Proportional-integral and Proportional-integral-derivative Regulators: Intelligent Proportional-derivative Regulators. International Journal of Robust and Nonlinear Control 2022, 32, 9512–9524.

- Doublet, M.; Join, C.; Hamelin, F. Model-Free Control for Unknown Delayed Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd Conference on Control and Fault-Tolerant Systems (SysTol), 2016, pp. 630–635.

- Safaei, A.; Mahyuddin, M.N. Adaptive Model-Free Control Based on an Ultra-Local Model With Model-Free Parameter Estimations for a Generic SISO System. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 4266–4275.

- Fliess, M.; Sira-Ramírez, H. Closed-Loop Parametric Identification for Continuous-time Linear Systems via New Algebraic Techniques. In Identification of Continuous-time Models from Sampled Data; Springer London: London, 2008; pp. 363–391.

- Chen, W.H.; Ballance, D.; Gawthrop, P.; O’Reilly, J. A Nonlinear Disturbance Observer for Robotic Manipulators. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2000, 47, 932–938.

- Fliess, M.; Sira–Ramírez, H. An Algebraic Framework for Linear Identification. ESAIM: Control, Optimisation and Calculus of Variations 2003, 9, 151–168.

| Parameter description | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| DC-bus voltage | 34 V | |

| Rated voltage | 24 V | |

| No-Load Speed | N | 150 rpm |

| Peak locked torque | 10 N·m | |

| Peak locked current | 8 A | |

| Pole pairs | 20 | |

| Stator resistance | 1.8 | |

| Stator inductance | 6 mH | |

| Motor inertia | 0.00412 kg·m2 | |

| Permanent magnet flux | 0.05498 Wb |

| Controller | Speed overshoot(rpm) | Settling time(s) | ||||

| MFSC-API | 1.00 | 1.21 | 1.63 | 0.0710 | 0.0855 | 0.0895 |

| MFSC-NDO | 18.84 | 9.17 | 8.30 | 0.0485 | 0.0430 | 0.0630 |

| EMFSC-NDO | 1.43 | 3.64 | 5.72 | 0.0340 | 0.0520 | 0.0765 |

| AEMFSC-NDO | 2.52 | 5.74 | 7.62 | 0.0405 | 0.0455 | 0.0585 |

| Controller | Speed drop(rpm) | Settling time(s) | ||||

| MFSC-API | 5.89 | 10.41 | 15.66 | – | – | – |

| MFSC-NDO | 6.42 | 10.69 | 16.31 | 0.372 | 0.397 | 0.453 |

| EMFSC-NDO | 6.21 | 10.92 | 16.57 | 0.345 | 0.379 | 0.416 |

| AEMFSC-NDO | 5.90 | 9.20 | 16.02 | 0.3355 | 0.3675 | 0.4045 |

| Controller | Speed RMSE(rpm) | 30rpm IAE | 90rpm IAE | ||||||

| MFSC-API | 5.773 | 6.390 | 6.939 | 2.640 | 4.760 | 6.581 | 2.962 | 4.607 | 6.936 |

| MFSC-NDO | 4.784 | 5.185 | 5.548 | 1.629 | 1.700 | 1.795 | 2.215 | 2.341 | 2.881 |

| EMFSC-NDO | 4.772 | 5.018 | 5.525 | 1.608 | 1.645 | 1.669 | 2.203 | 2.345 | 2.516 |

| AEMFSC-NDO | 4.786 | 4.991 | 5.518 | 1.679 | 1.694 | 1.724 | 2.224 | 2.304 | 2.380 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).