Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Measures

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Clearance

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dietary Motives and Lifestyle Preferences

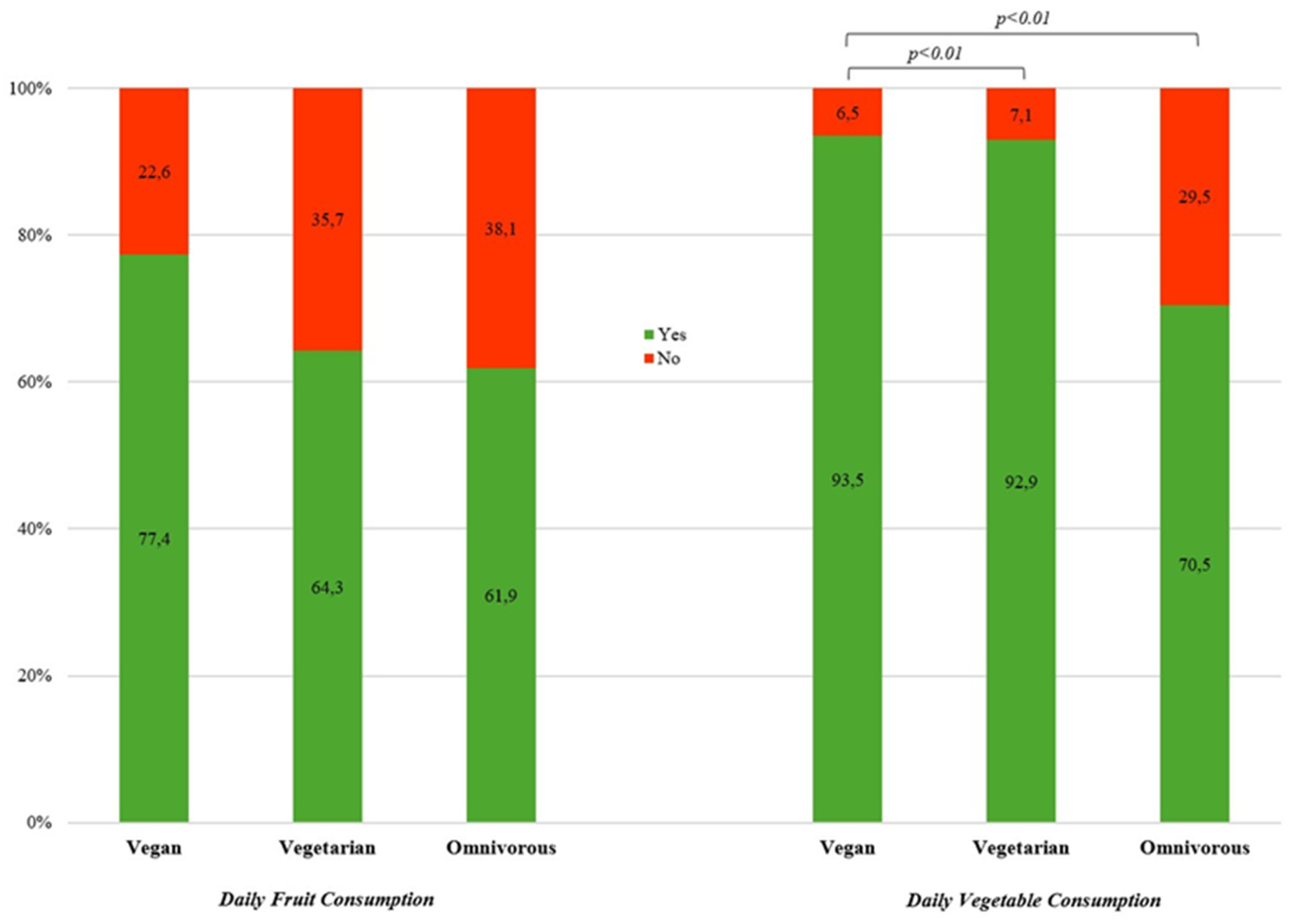

3.2. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption

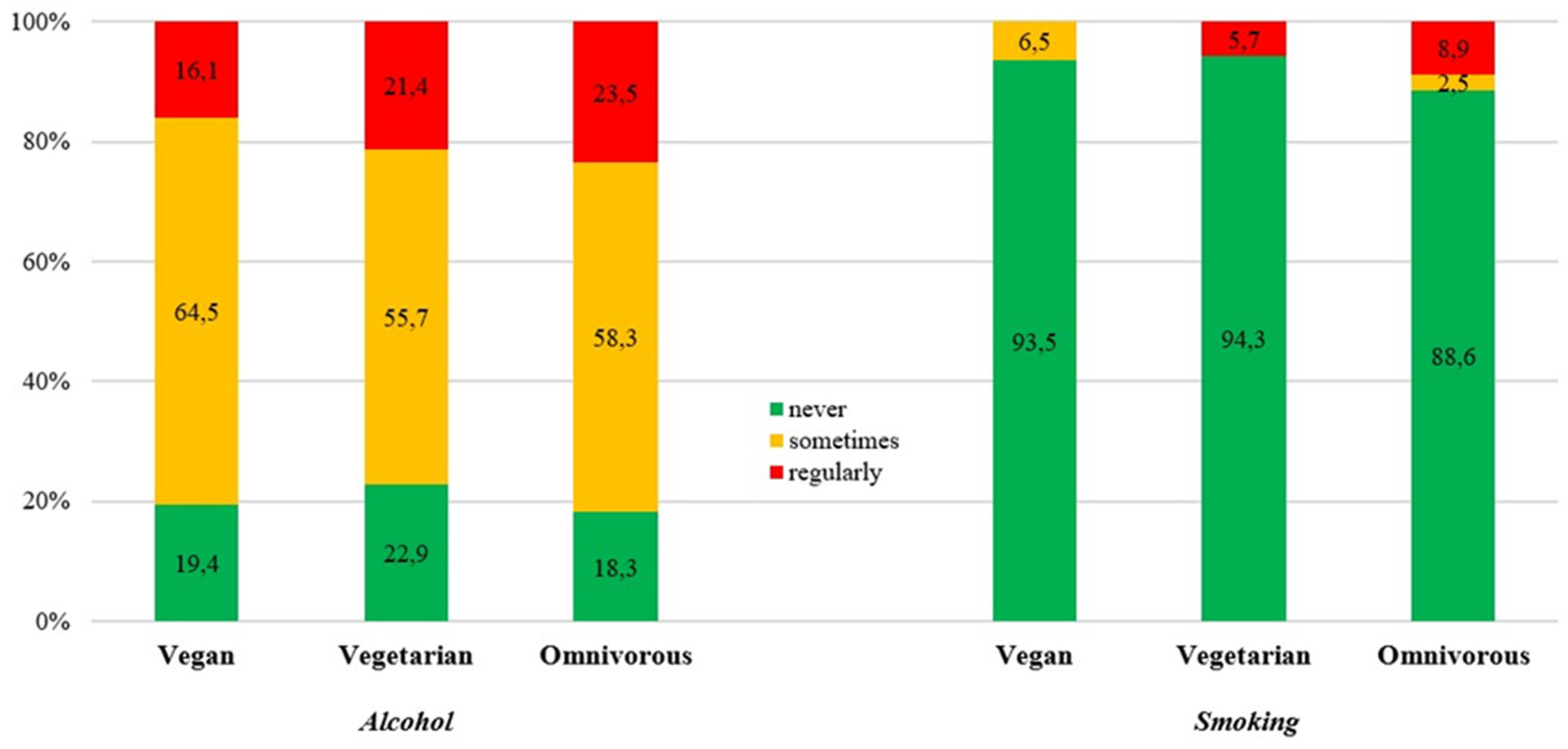

3.3. Fluids, Alcohol, and Nicotine Consumption

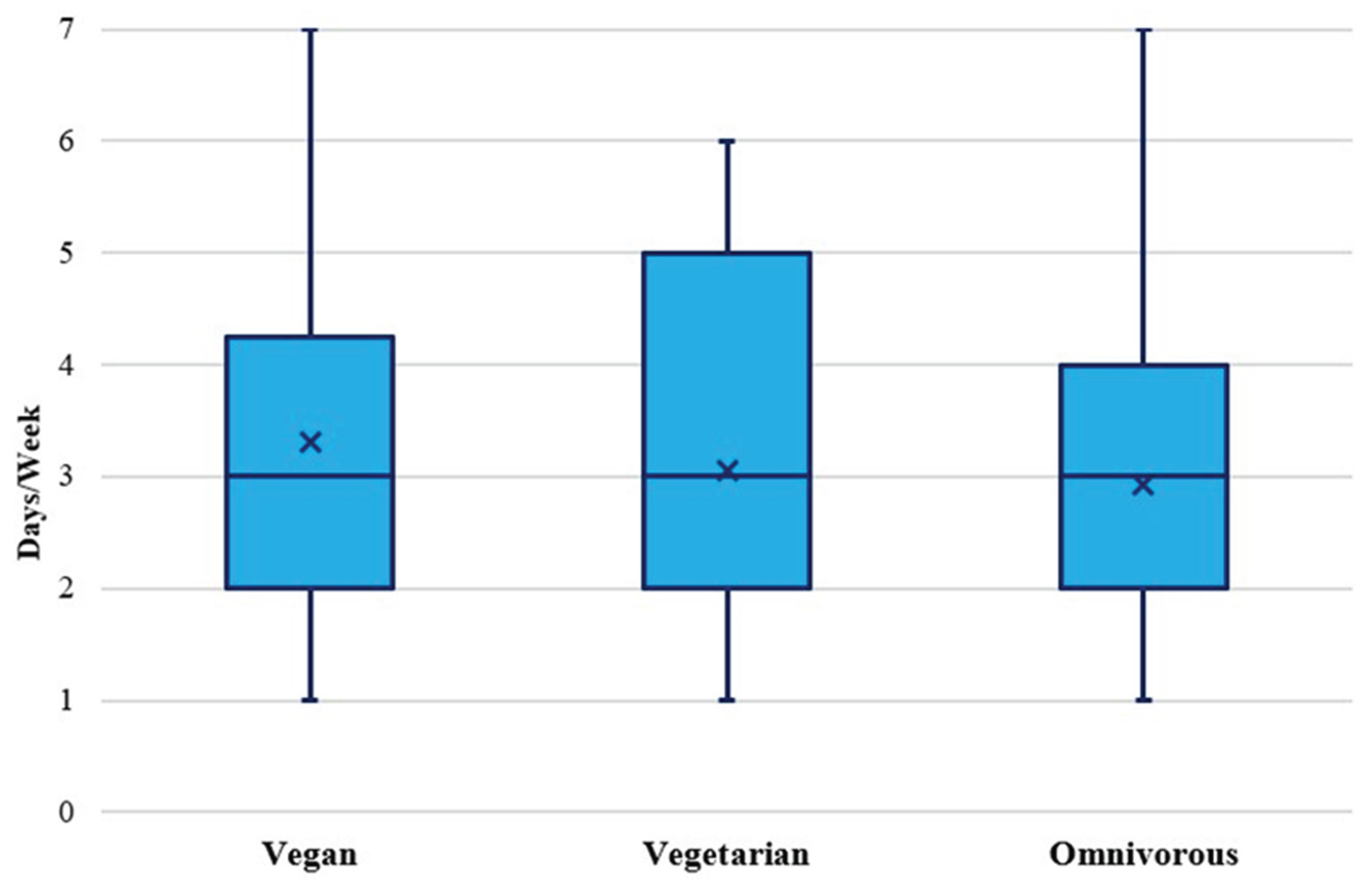

3.4. PA, Sports & Exercise Participation

|

TOTAL (N=1,350) |

Leisure Time Sports 88.7% (n=1,197) |

Club Sports 29.2% (n=394) |

||||

| Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | |

| 83.9% (n=26) |

88.6% (n=62) |

88.9% (n=1,110) |

29.0% (n=9) |

22.9% (n=16) |

29.5% (n=369) |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 57.1 (n=4) | 80.0 (n=8) | 91.8 (n=360) | 28.6 (n=2) | 30.0 (n=3) | 39.5 (n=155) |

| Female | 91.7 (n=22) | 90.0 (n=54) | 87.5 (n=750) | 29.2 (n=7) | 21.7 (n=13) | 25.0 (n=214) |

| Teaching Level | ||||||

| Middle School | 90.0 (n=9) | 86.7 (n=26) | 89.7 (n=373) | 40.0 (n=4) | 20.0 (n=6) | 31.0 (n=129) |

| High School | 76.9 (n=10) | 85.2 (n=23) | 88.6 (n=523) | 15.4 (n=2) | 25.9 (n=7) | 26.8 (n=158) |

|

Middle & High School Pooled |

87.5 (n=7) | 100 (n=13) | 88.1 (n=214) | 37.5 (n=3) | 23.1 (n=3) | 33.7 (n=82) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 82.4 (n=14) | 88.2 (n=30) | 89.1 (n=408) | 23.5 (n=4) | 23.5 (n=8) | 25.8 (n=118) |

| Rural | 85.7 (n=12) | 88.9 (n=32) | 88.7 (n=702) | 35.7 (n=5) | 22.2 (n=8) | 31.7 (n=251) |

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Full Time | 79.2 (n=19) | 95.9 (n=47) | 89.8 (n=879) | 33.3 (n=8) | 24.5 (n=12) | 31.1 (n=304) |

| Part Time | 100 (n=7) | 71.4 (n=15) | 85.6 (n=231) | 14.3 (n=1) | 19.0 (n=4) | 24.1 (n=65) |

4. Discussion

4.1. Diet Type Prevalences, Motivations, and Sociodemographics

4.2. Fruit & Vegetable Consumption

4.3. Fluid Intake, Alcohol, and Nicotine Consumption

4.4. PA, Sports & Exercise Levels, Interests, and Motivations

4.5. Study Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

| Health |

Taste/ Preference |

Animal Welfare | Environment Protection | Tradition | Food Quality | Family |

Sports Performance |

Social Aspects |

No specific reason/ Other |

||

|

TOTAL SAMPLE |

Overview | 46.4 | 22.6 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 9.6 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 6.4 |

| Omnivorous | 46.9 | 23.8 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 10.2 | 7.4 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 6.8 | |

| Vegetarian | 37.1 | 10.0 | 40.0 | 5.7 | NA | 2.9 | 1.4 | NA | 1.4 | 1.4 | |

| Vegan | 48.4 | 3.2 | 29.0 | 12.9 | 3.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.2 | |

| MALE | Omnivorous | 45.9 | 25.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 10.5 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 9.2 |

| Vegetarian | 30.0 | NA | 50.0 | 10.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10.0 | |

| Vegan | 28.6 | NA | 57.1 | 14.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FEMALE | Omnivorous | 47.4 | 22.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 10.2 | 8.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 5.7 |

| Vegetarian | 38.3 | 11.7 | 38.3 | 5.0 | NA | 3.3 | 1.7 | NA | 1.7 | NA | |

| Vegan | 54.2 | 4.2 | 20.8 | 12.5 | 4.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.2 | |

| MIDDLE SCHOOL | Omnivorous | 50.0 | 21.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 11.3 | 7.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | NA | 5.6 |

| Vegetarian | 30.0 | 13.3 | 43.3 | 6.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.3 | 3.3 | |

| Vegan | 40.0 | 10.0 | 30.0 | 10.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10.0 | |

| HIGH SCHOOL | Omnivorous | 46.3 | 23.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 10.9 | 8.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 7.8 |

| Vegetarian | 55.6 | 7.4 | 25.9 | 7.4 | NA | 3.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 53.8 | NA | 23.1 | 15.4 | 7.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| MIDDLE & HIGH SCHOOL POOLED | Omnivorous | 43.2 | 28.4 | 2.5 | NA | 7.8 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 0.8 | NA | 6.5 |

| Vegetarian | 15.4 | 7.7 | 61.5 | NA | NA | 7.7 | 7.7 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 50.0 | NA | 37.5 | 12.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| URBAN | Omnivorous | 44.5 | 25.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 8.7 |

| Vegetarian | 38.2 | 5.9 | 38.2 | 5.9 | NA | 5.9 | 2.9 | NA | NA | 2.9 | |

| Vegan | 58.8 | NA | 29.4 | 5.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5.9 | |

| RURAL | Omnivorous | 48.3 | 23.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 11.4 | 7.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | NA | 5.7 |

| Vegetarian | 36.1 | 13.9 | 41.7 | 5.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.8 | NA | |

| Vegan | 35.7 | 7.1 | 28.6 | 21.4 | 7.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FULL TIME | Omnivorous | 48.1 | 24.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 10.2 | 6.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 6.7 |

| Vegetarian | 36.7 | 10.2 | 38.8 | 6.1 | NA | 2.0 | 2.0 | NA | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Vegan | 37.5 | 4.2 | 37.5 | 12.5 | 4.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.2 | |

| PART TIME | Omnivorous | 42.6 | 22.2 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 1.9 | 0.7 | NA | 7.0 |

| Vegetarian | 38.1 | 9.5 | 42.9 | 4.8 | NA | 4.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 85.7 | NA | NA | 14.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

Sport Engagement |

Sport Lifestyle |

Eating Meat | Vegetarian Diet | Vegetarian Lifestyle | Vegan Diet |

Vegan Lifestyle |

Alcohol | Smoking | ||

|

TOTAL SAMPLE |

Overview | 70.7 | 10.9 | 4.1 | 7.4 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.7 |

| Omnivorous | 73.7 | 11.4 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.7 | |

| Vegetarian | 31.4 | 5.7 | NA | 51.4 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 1.4 | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 41.9 | 3.2 | NA | 3.2 | 3.2 | 35.5 | 9.7 | NA | 3.2 | |

| MALE | Omnivorous | 79.1 | 10.5 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 1.3 | NA | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.8 |

| Vegetarian | 30.0 | NA | NA | 50.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 71.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14.3 | 14.3 | NA | NA | |

| FEMALE | Omnivorous | 71.2 | 11.8 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 0.7 |

| Vegetarian | 31.7 | 6.7 | NA | 51.7 | 6.7 | 3.3 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 33.3 | 4.2 | NA | 4.2 | 4.2 | 41.7 | 8.3 | NA | 4.2 | |

| MIDDLE SCHOOL | Omnivorous | 73.3 | 13.5 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 2.2 | NA | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Vegetarian | 23.3 | NA | NA | 60.0 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 30.0 | NA | NA | NA | 10.0 | 40.0 | 20.0 | NA | NA | |

| HIGH SCHOOL | Omnivorous | 74.7 | 10.0 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 2.2 | 02 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.7 |

| Vegetarian | 40.7 | 14.8 | NA | 33.3 | 3.7 | 7.4 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 38.5 | 7.7 | NA | 7.7 | NA | 30.8 | 7.7 | NA | 7.7 | |

| MIDDLE & HIGH SCHOOL POOLED | Omnivorous | 71.6 | 11.1 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 2.5 | NA | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.4 |

| Vegetarian | 30.8 | NA | NA | 69.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 62.5 | NA | NA | NA | 37.5 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| URBAN | Omnivorous | 73.6 | 10.5 | 3.9 | 6.6 | 2.0 | NA | 0.4 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| Vegetarian | 32.4 | 8.8 | NA | 55.9 | NA | 2.9 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 47.1 | NA | NA | 5.9 | 5.9 | 29.4 | 11.8 | NA | NA | |

| RURAL | Omnivorous | 73.7 | 11.9 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| Vegetarian | 30.6 | 2.8 | NA | 47.2 | 11.1 | 5.6 | 2.8 | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 35.7 | 7.1 | NA | NA | NA | 42.9 | 7.1 | NA | 7.1 | |

| FULL TIME | Omnivorous | 73.4 | 12.0 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 2.2 | NA | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| Vegetarian | 28.6 | 8.2 | NA | 51.0 | 8.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 41.7 | NA | NA | NA | 4.2 | 37.5 | 12.5 | NA | 4.2 | |

| PART TIME | Omnivorous | 74.4 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 0.4 |

| Vegetarian | 38.1 | NA | NA | 52.4 | 9.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vegan | 42.9 | 14.3 | NA | 14.3 | NA | 28.6 | NA | NA | NA |

References

- Harrap C (2024). 2024 Olympics Set To Double Its Plant-Based Food Offering. The Paris 2024 Summer Olympics will be more plant-based than ever. Plant Based News, 20. 2. 2024: https://plantbasednews.org/culture/events/olympics-double-plant-based-food/ (10.10. 2024).

- Irish Farmers Journal (2024). Paris Olympics going 60% meat-free, online 8. 5. 2024: https://www.farmersjournal.ie/news/dealer/paris-olympics-going-60-meat-free-816267 (10.10.2024).

- Rowlands S (2024). Exclusive: More than 60% of food at the Olympic Games will be vegan for first time ever. Mirror online, 23. 3. 2024: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/more-60-food-olympic-games-32426179#google_vignette (10. 10. 2024).

- Schattauer G (2024) UEFA-Pläne für Deutschland. Vegane Kost, Unisex-Toiletten, Meldestelle – so „woke“ wird die Fußball-EM 2024. Focus online, 23.6.2024: https://www.focus.de/sport/uefa-plaene-fuer-deutschland-fussball-em-2024-welche-woken-regeln-die-uefa-geplant-hat_id_199488249.html (10.10.2024).

- Epp M (2024a) Unisex-Toiletten, alkoholfreie Getränke, vegane Speisen: UEFA plant Zusatz-Angebote bei der EM 2024. Frankfurter Rundschau online: 12.4.2024: https://www.fr.de/sport/fussball/em-2024-uefa-nachhaltigkeit-umwelt-lahm-strategiepapier-vegan-92411292.html (10.10.2024).

- Epp M (2024b) Vegane Speisen, Unisex-Toiletten: EM 2024 soll neue Maßstäbe setzen. Tz online, 12.4.2024: https://www.tz.de/sport/fussball/em-2024-uefa-nachhaltigkeit-umwelt-lahm-strategiepapier-vegan-92411293.html (10.10.2024).

- Knauth S (2024) Fußball-EM 2024: Fußball zwischen Bier, Bratwurst und etwas Veganem. News.de, 7.6.2024: https://www.news.de/sport/857813651/fussball-zwischen-bier-bratwurst-und-etwas-veganem-fussball-em-2024-news-der-dpa-aktuell-zu-em-kabarett-und-fussball/1/ (10.10.2024).

- World Health Organization (2021). Plant-based diets and their impact on health, sustainability and the environment: a review of the evidence: WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021. Document number: WHO/EURO:2021-4007-43766-61591.

- Poore J, Nemecek T (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360,987-992(2018). [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, P., Clark, M., Cobiac, L. et al. (2023). Vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters in the UK show discrepant environmental impacts. Nat Food 4, 565–574 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Springmann M (2024). A multicriteria analysis of meat and milk alternatives from nutritional, health, environmental, and cost perspectives, PNAS, 121 (50) e2319010121. [CrossRef]

- Petter O (2020) Veganism is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce our environmental impact, study finds. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/veganism-environmental-impact-planet-reduced-plant-based-diet-humans-study-a8378631.html#:~:text=Lead%20author%20Joseph%20Poore%20said,land%20use%20and%20water%20use.%22 (14.10.2024).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2022). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Technical Summary, page 117/505. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2023). CLIMATE CHANGE 2023 Synthesis Report, page 29/42. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (23.3.2024).

- Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better--improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1221–8. [CrossRef]

- GoInvo. Determinants of Health, 2017-2018. https://www.goinvo.com/vision/determinants-of-health/ (Accessed May 20, 2023).

- World Health Organization (2/2/2025). Noncommunicable diseases: Risk factors and conditions, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/ncd-risk-factors.

- Marques, A., Peralta, M., Martins, J., Loureiro, V., Almanzar, P. C., and Matos, M. G. de (2019). Few European Adults are Living a Healthy Lifestyle. American journal of health promotion : AJHP. 33(3): 391–398.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2/5/2025). GBD Results, https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- World Health Organization (2/2/2025). Non communicable diseases, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- World Health Organization (2018). Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles, Austria. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/country-profiles/ncds/aut_en.pdf?sfvrsn=cd1153b_40&download=true.

- Statistik Austria. (19/3/2025). Todesursachen. https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/gestorbene/todesursachen.

- World Obesity Federation Global Obesity Observatory (2/5/2025). World Obesity Day Atlases | Obesity Atlas 2023. https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=19.

- Warburton, D. E. R., Nicol, C. W., and Bredin, S. S. D. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 174(6): 801–809.

- Hansford HJ, Wewege MA, Cashin AG, Hagstrom AD, Clifford BK, McAuley JH, Jones MD. If exercise is medicine, why don't we know the dose? An overview of systematic reviews assessing reporting quality of exercise interventions in health and disease. British journal of sports medicine. 2022;56:692–700. [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N. D., Cohen, J., Jenkins, D. J. A., Turner-McGrievy, G., Gloede, L., Green, A., and Ferdowsian, H. (2009). A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 89(5): 1588S-1596S.

- Esselstyn, C. B., Gendy, G., Doyle, J., Golubic, M., and Roizen, M. F. (2014). A way to reverse CAD? The Journal of family practice. 63(7): 356-364b.

- Orlich, M. J., and Fraser, G. E. (2014). Vegetarian diets in the Adventist Health Study 2: a review of initial published findings. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 100 Suppl 1(1): 353S-8S.

- Landry, M. J., Ward, C. P., Cunanan, K. M., Durand, L. R., Perelman, D., Robinson, J. L., Hennings, T., Koh, L., Dant, C., Zeitlin, A., Ebel, E. R., Sonnenburg, E. D., Sonnenburg, J. L., and Gardner, C. D. (2023). Cardiometabolic Effects of Omnivorous vs Vegan Diets in Identical Twins: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open. 6(11): e2344457.

- Michael Benjamin Arndt, Yohannes Habtegiorgis Abate, Mohsen Abbasi-Kangevari, Samar Abd ElHafeez, Michael Abdelmasseh, Sherief Abd-Elsalam, et al. Global, regional, and national progress towards the 2030 global nutrition targets and forecasts to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2025;404:2543–83. [CrossRef]

- Leitzmann, C., Keller, M. (2020). Vegetarische und vegane Ernährung. 4., völlig überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. UTB.

- Raghupathi, V., Raghupathi, W (2020). The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Arch Public Health 78, 20 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zajacova A, Lawrence EM (2018). The Relationship Between Education and Health: Reducing Disparities Through a Contextual Approach. Annual Review of Public Health, Vol. 39: 273-289.

- WHO Regional Office Europe (2015). Health 2020: Education and health through the life-course. Sector brief on Education, July 2015. Copenhagen, Denmark. Document number: WHO/EURO:2015-6161-45926-66190.

- Suhrcke M, de Paz Nieves C; WHO Regional Office Europe (2011). The impact of health and health behaviours on educational outcomes in high-income countries: a review of the evidence. Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Eide E, Showalter M (2011) Estimating the relation between health and education: What do we know and what do we need to know? Economics of Education Review, Volume 30, Issue 5, 2011: 778-791.

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (2024). Learning for life: The higher the level of education, the lower the risk of dying. https://www.healthdata.org/news-events/newsroom/news-releases/learning-life-higher-level-education-lower-risk-dying.

- Hurrelmann K (2016). Zehn Thesen zur Lehrer- und Schülergesundheit; p. 7. In: Forum Schulstiftung (2016). Forum Schulstiftung, 64. Schwerpunkt: Die Gesunde Lehr-Kraft. Zeitschrift für die katholischen freien Schulen der Erzdiözese Freiburg. 26. Jahrgang; pp. 82. ISSN 1611342x.

- Cutler DM & Lleras-Muney A (2012). Education and Health: Insights from International Comparisons. Working Paper 17738. NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH. [CrossRef]

- Groot W, Maassen van den Brink H (2007). The health effects of education. Economics of Education Review 26 (2007): 186-200.

- Ross, C. E., & Wu, C. (1995). The Links Between Education and Health. American Sociological Review, 60(5), 719–745. [CrossRef]

- Grundsatzerlass. Erlass des Bundensministeriums fuer Unterricht und kulturelle Angelegenheiten GZ 27.909/115-V/3/96 vom 4. Maerz 1997. Rundschreiben Nr. 7/1997 Herausgegeben vom BMUK, Abt. V/3, Freyung 1, A-1014 Wien.

- Health promoting schools. 4/15/2025. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-promoting-schools#tab=tab_1. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- Schools for Health in Europe | European School Education Platform. 4/14/2025. https://school-education.ec.europa.eu/en/discover/resources/schools-health-europe. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- He, L., Zhai, Y., Engelgau, M., Li, W., Qian, H., Si, X., Gao, X., Sereny, M., Liang, J., Zhu, X., and Shi, X. (2014). Association of children's eating behaviors with parental education, and teachers' health awareness, attitudes and behaviors: a national school-based survey in China. European journal of public health. 24(6): 880–887.

- Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes (01/09/2024). Lehrplan der Allgemeinbildenden Höheren Schule, https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/NormDokument.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10008568&Artikel=&Paragraf=&Anlage=1&Uebergangsrecht=.

- Dadaczynski, K., Jensen, B.B., Viig, N.G., Sormunen, M., von Seelen, J., Kuchma, V. and Vilaça, T. (2020), "Health, well-being and education: Building a sustainable future. The Moscow statement on Health Promoting Schools", Health Education, Vol. 120 No. 1, pp. 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Scheuch, K., Seibt, R., Rehm, U., Riedel, R. & Melzer, W. (2010). Lehrer. In: S. Letzel & D. Nowak (Hrsg.), Handbuch der Arbeitsmedizin. Fulda: Fuldaer Verlagsanstalt.

- Johannsen, U. (2007). Die gesundheitsfördernde Schule. Gesundheitsförderung durch Organisations- und Schulentwicklung. Saarbrücken. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

- Wilf-Miron, R., Kittany, R., Saban, M., and Kagan, I. (2022). Teachers' characteristics predict students' guidance for healthy lifestyle: a cross-sectional study in Arab-speaking schools. BMC Public Health. 22(1): 1420.

- Nieskens B, Rupprecht S, and Erbring S. Was hält Lehrkräfte gesund? Ergebnisse der Gesundheitsforschung für Lehrkräfte und Schulen. In Handbuch Lehrergesundheit Impulse für die Entwicklung Guter Gesunder Schulen; Eine Veröffentlichung der DAK-Gesundheit und der Unfallkasse Nordrhein-Westfalen; Carl Link (Wolters Kuiwer): Köln, Germany (2012). p. 31–96.

- Bundesministerium für Bildung (BMB) (2025). Unterrichtsprinzipien. https://www.bmb.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulpraxis/prinz.html and https://www.bmb.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulpraxis/prinz/gesundheitsfoerderung.html (22.4.2025).

- Felder-Puig, R.; Ramelow, D.; Maier, G.; Teutsch, F. Ergebnisse der WieNGS Lehrer/Innen-Befragung 2017; Institut für Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention: Wien, Austria, 2017.

- Steen, R. Lehrer/innen stark machen!—Nachdenken über Gesundheit in der Schule. Ein Beitrag aus Sicht der Gesundheitsförderung. Make Teachers Stronger!—Considerations on Health in Schools. A Contribution from the Viewpoint of Health Promotion. Gesundheitswesen 2011, 73, 112–116.

- Teutsch, F.; Hofmann, F.; Felder-Puig, R. Kontext und Praxis schulischer Gesundheitsförderung. In Ergebnisse der Österreichischen Schulleiter/Innenbefragung 2014; LBIHPR Forschungsbericht; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG): Wien, Austria, 2015.

- Hofmann, F.; Griebler, R.; Ramelow, D.; Unterweger, K.; Griebler, U.; Felder-Puig, R.; Dür, W. Gesundheit und Gesundheitsverhalten von Österreichs Lehrer/Innen: Ergebnisse der Lehrer/Innenbefragung 2010; LBIHPR Forschungsbericht; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG): Wien, Austria, 2012.

- Hofmann, F.; Felder-Puig, R. HBSC Factsheet Nr. 05/2013. In Gesundheitszustand und—Verhalten Österreichischer Lehrkräfte: Ergebnisse der Lehrer/Innen-Gesundheitsbefragung 2010; LBIHPR Forschungsbericht; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG): Wien, Austria, 2013.

- Gesundheitsförderung in der Schule. 2015. https://www.sozialversicherung.at/cdscontent/?contentid=10007.844051&portal=svportal. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- Bono ML, Hart P (2024). Wiener Gesundheitsförderung. Abschlussbericht der Evaluation des „Wiener Netzwerks Gesundheitsfördernde Schulen“ (WieNGS) im Jahr 2023; pp. 45. (3.4.2025).

- Lillich, M. und Breil, C. (2024). Gesundheitsbefragung von österreichischen Schulleitungen und Pädagog:innen: Handlungsbericht; pp. 23. Wien: Institut für Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention. (3.4.2025).

- Felder-Puig R, Grieber R (2021). Studienergebnisse zur Gesundheit von Lehrkräften aus Österreich und Deutschland; pp 36-46. In: NCoC (National Center of Competence) für Psychosoziale Gesundheitsförderung an der Pädagogischen Hochschule Oberösterreich (Hrsg.) (2021).

- Gesundsein und Gesund bleiben im Schulalltag Wissenswertes und Praktisches zur Lehrer*innengesundheit. Handreichung für gute, gesundheitsfördernde Schulen; pp. 217. https://ph-ooe.at/fileadmin/Daten_PHOOE/Zentren/Persoenlichkeitsbildung/publikationen/HEPI_Publikation_Lehrerinnnengesundheit_ONLINE_2.5.pdf (3.4.2025).

- Felder-Puig R, Griebler R (2021): Studienergebnisse zur Gesundheit von Lehrkräften aus Österreich und Deutschland. In: Gesundsein und Gesundbleiben im Schulalltag. Wissenswertes und Praktisches zur Lehrer*innengesundheit. Handreichung für gute, gesundheitsfördernde Schulen. NCoC (National Center of Competence) für Psychosoziale Gesundheitsförderung an der Pädagogischen Hochschule Oberösterreich, Linz, pp. 36-56.

- Schmich J, Itzlinger-Bruneforth U (Hrsg.) (2019). TALIS 2018 (Band 1). Rahmenbedingungen des schulischen Lehrens und Lernens aus Sicht von Lehrkräften und Schulleitungen im internationalen Vergleich; pp. 148. Graz: Leykam. . ISBN 978-3-7011-8139-1.

- Schmich J, Opriessnig S (Hrsg.) (2020). TALIS 2018 (Band 2). Rahmenbedingungen des schulischen Lehrens und Lernens aus Sicht von Lehrkräften und Schulleitungen im internationalen Vergleich; pp. 120. Salzburg, 2020.

- Scheuch K, Haufe E, Seibt R: Teachers’ health. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015; 112: 347–56. [CrossRef]

- Scheuch K, Pardula T, Prodehl G, Winkler C, Seibt R (2016). Betriebsärztliche Betreuung von Lehrkräften. Ausgewählte Ergebnisse aus Sachsen. Präv Gesundheitsf, 2016; 11:147–153. [CrossRef]

- Schaarschmidt, U. (2005). Halbtagsjobber? Psychische Gesundheit im Lehrerberuf Analyse eines veränderungsbedürftigen Zustandes. Weinheim, Basel, Berlin: Beltz. 172 S.

- Melina, V., Craig, W., and Levin, S. (2016). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 116(12): 1970–1980.

- Raj S, Guest NS, Landry MJ, Mangels AR, Pawlak R, Rozga M. Vegetarian dietary patterns for adults: a position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Journal fo the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2025;S2212-2672(25)00042-5.

- FMCG Gurus (2/5/2025). FMCG Gurus - Understanding the Growing Increase of Plant Based Diets - Global 2020 - FMCG Gurus, https://fmcggurus.com/reports/fmcg-gurus-understanding-the-growing-increase-of-plant-based-diets-global-2020/.

- Paslakis, G., Richardson, C., Nöhre, M., Brähler, E., Holzapfel, C., Hilbert, A., and Zwaan, M. de (2020). Prevalence and psychopathology of vegetarians and vegans - Results from a representative survey in Germany. Scientific reports. 10(1): 6840.

- Smart Protein Report (2023). Evolving appetites: an in-depth look at European attitudes towards plant-based eating. https://smartproteinproject.eu/european-attitudes-towards-plant-based-eating/ (23.1.2025).

- Vegane Gesellschaft Östereich (VGÖ) (2024). Österreich als Spitzenreiter beim Anteil von vegan und fleischlos lebenden Menschen. https://www.vegan.at/zahlen (23.1.2025).

- Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (2014). Fleischatlas 2014 - Daten und Fakten über Tiere als Nahrungsmittel. https://www.boell.de/de/2014/01/07/fleischatlas-2014 (23.1.2025).

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (2021). Deutschland, wie es isst – Der BMEL-Ernährungsreport 2021. https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/_Ernaehrung/ernaehrungsreport-2021.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=7 (23.1.2025).

- Leitzmann, C, Keller, M. Charakteristika vegetarischer Ernährungs- und Lebensformen. In Vegetarische und Vegane Ernährung, 4th ed.; Vollständig überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage; UTB, Bd 1868; Verlag Eugen Ulmer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020; pp. 25–31. (In German).

- Ramelow, D et al. (2017): Ergebnisse der WieNGS-Lehrer*innen-Befragung 2012. Ludwig Boltzmann Institut - HPR, Wien.

- Ruby, M. B., and Heine, S. J. (2011). Meat, morals, and masculinity. Appetite. 56(2): 447–450.

- Ashkan Afshin, Patrick John Sur, Kairsten A. Fay, Leslie Cornaby, Giannina Ferrara, Joseph S Salama, et al (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 393(10184): 1958–1972.

- Murphy, S. P., and Allen, L. H. (2003). Nutritional importance of animal source foods. The Journal of nutrition. 133(11 Suppl 2): 3932S-3935S.

- Orlich, M. J., Singh, P. N., Sabaté, J., Jaceldo-Siegl, K., Fan, J., Knutsen, S., Beeson, W. L., and Fraser, G. E. (2013). Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA internal medicine. 173(13): 1230–1238.

- Kelly C, Clennin MN, Barela BA, Wagner A. Practice-Based Evidence Supporting Healthy Eating and Active Living Policy and Environmental Changes. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(2):166-172. [CrossRef]

- Koehler K, Drenowatz C. Integrated Role of Nutrition and Physical Activity for Lifelong Health. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1437. Published 2019 Jun 26. [CrossRef]

- Houghtaling B, Balis L, Pradhananga N, Cater M, Holston D. Healthy eating and active living policy, systems, and environmental changes in rural Louisiana: a contextual inquiry to inform implementation strategies. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2023;20:132. [CrossRef]

- World Obesity Federation Global Obesity Observatory. Austria. 4/15/2025. https://data.worldobesity.org/country/austria-11/. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- Statistik Austria. Overweight and obesity. 11/16/2023. https://www.statistik.at/en/statistics/population-and-society/health/health-determinants/overweight-and-obesity. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- Statistik Austria. Physical activity. 12/19/2024. https://www.statistik.at/en/statistics/population-and-society/health/health-determinants/physical-activity. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- Schalit J. Physical inactivity costs estimated at €80bn per year. 6/18/2015. https://www.euractiv.com/section/sports/news/physical-inactivity-costs-estimated-at-80bn-per-year/. Accessed 15 Apr 2025.

- Key TJ, Papier K, Tong TYN. Plant-based diets and long-term health: findings from the EPIC-Oxford study. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2022;81:190–8. [CrossRef]

- Phillips R, Lemon F, Beeson W, Kzuma J (1978) Coronary heart disease mortality among seventh–day adventists with differing dietary habits: A preliminary report. Am J Clin Nutr 31: 191-198.

- Scientific Publications About Adventists | Adventist Health Study. https://adventisthealthstudy.org/researchers/scientific-publications/scientific-publications-about-adventists (accessed Feb 28, 2025).

- Adventist Health Study-1 Publication Database | Adventist Health Study. https://adventisthealthstudy.org/researchers/scientific-publications/adventist-health-study-1-publication-database (accessed Feb 28, 2025).

- Adventist Health Study-2 Publication Database | Adventist Health Study. https://adventisthealthstudy.org/researchers/scientific-publications/adventist-health-study-2-publication-database (accessed Feb 28, 2025).

- Dwaraka VB et al. (2023). Unveiling the Epigenetic Impact of Vegan vs. Omnivorous Diets on Aging: Insights from the Twins Nutrition Study (TwiNS). medRxiv 2023.12.26.23300543; [CrossRef]

- Ravi AK et al. (2025). Suboptimal dietary patterns are associated with accelerated biological aging in young adulthood: A study with twins. Clinical Nutrition, Volume 45 (2025): 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Jennings A et al. (2021) Increased habitual flavonoid intake predicts attenuation of cognitive ageing in twins. BMC Med 19, 185 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tong TYN, Papier K, Key TJ. Meat, vegetables and health - interpreting the evidence. Nat Med. 2022 Oct;28(10):2001-2002. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., Moore, L. V., Park, S., Harris, D. M., and Blanck, H. M. (2022). Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations - United States, 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 71(1): 1–9.

- AGES. Österreichische Ernährungsempfehlungen. (2025). https://www.ages.at/mensch/ernaehrung-lebensmittel/ernaehrungsempfehlungen/oesterreichische-ernaehrungsempfehlungen. (22.04.2025).

- Gesundheit.gv.at (2024). Ernährungsempfehlungen: Gemüse, Obst und Hülsenfrüchte.https://www.gesundheit.gv.at/leben/ernaehrung/info/oesterreichische-ernaehrungspyramide/ernaehrungspyramide-obst-gemuese1.html (18.4.2025).

- Cheung, P. (2020). Teachers as role models for physical activity: Are preschool children more active when their teachers are active? European Physical Education Review. 26(1): 101–110.

- Okan O, Bauer U, Levin-Zamir D, Pinheiro P, and Sorensen K. International Handbook of Health Literacy. Research, Practice and Policy Across the Lifespan. Bristol: Policy Press (2019). [CrossRef]

- EAT Lancet Commission (4/7/2021). The Planetary Health Diet - EAT, https://eatforum.org/eat-lancet-commission/the-planetary-health-diet-and-you/.

- Murray, CJL, Aravkin, AY, Zheng, P ∙ et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 Lancet. 2020; 396:1223-1249.

- Kennedy, Joe et al. Estimated effects of reductions in processed meat consumption and unprocessed red meat consumption on occurrences of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, colorectal cancer, and mortality in the USA: a microsimulation study. The Lancet Planetary Health, Volume 8, Issue 7, e441 - e451.

- Yan D, Liu K, Li F, Shi D, Wei L, Zhang J, Su X, Wang Z. Global burden of ischemic heart disease associated with high red and processed meat consumption: an analysis of 204 countries and territories between 1990 and 2019. BMC Public Health. 2023 Nov 17;23(1):2267. [CrossRef]

- Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, Ghissassi FE, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, et al. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Dec 1;16(16):1599–600.

- WHO (2015) IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat. Press release N°240. https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr240_E.pdf (28.2.2025).

- WHO (2015) Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/cancer-carcinogenicity-of-the-consumption-of-red-meat-and-processed-meat (28.2.2025).

- Li, Chunxiao et al. (2024). Meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: an individual-participant federated meta-analysis of 1·97 million adults with 100 000 incident cases from 31 cohorts in 20 countries. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, Volume 12, Issue 9, 619 – 630.

- Zhou, Xiao-Dong et al. (2024) Burden of disease attributable to high body mass index: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. eClinicalMedicine, Volume 76, 102848.

- Bellavia A, Stilling F, Wolk A (2016) High red meat intake and all-cause cardiovascular and cancer mortality: Is the risk modified by fruit and vegetable intake? Am J Clin Nutr 104: 1137-1143.

- Goldfarb G and Sela Y. The Ideal Diet for Humans to Sustainably Feed the Growing Population – Review, Meta-Analyses, and Policies for Change. F1000Research 2023, 10:1135. [CrossRef]

- Greger M. Plant-Based Nutrition to Slow the Aging Process. ijdrp. 2023;6(1):4 pp. [CrossRef]

- Alexy U. Diet and growth of vegetarian and vegan children. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health 2023;6:e000697. [CrossRef]

- Jakše, B.; Fras, Z.; Fidler Mis, N. Vegan Diets for Children: A Narrative Review of Position Papers Published by Relevant Associations. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4715. [CrossRef]

- Athanasian CE, Lazarevic B, Kriegel ER, Milanaik RL. Alternative diets among adolescents: facts or fads? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021 Apr 1;33(2):252-259. [CrossRef]

- Kiely ME. Risks and benefits of vegan and vegetarian diets in children. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2021;80(2):159-164. [CrossRef]

- Rudloff S, Bührer C, Jochum F, Kauth T, Kersting M, Körner A, Koletzko B, Mihatsch W, Prell C, Reinehr T, Zimmer KP. Vegetarian diets in childhood and adolescence : Position paper of the nutrition committee, German Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ). Mol Cell Pediatr. 2019 Nov 12;6(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Patelakis, E., Lage-Barbosa, C., Haftenberger, M., et al. (2019) Prevalence of Vegetarian Diet among Children and Adolescents in Germany. Results from EsKiMo II. Ernaehrungs Umschau, 66, 85-91.

- Metoudi M, Bauer A, Haffner T, Kassam S. A cross-sectional survey exploring knowledge, beliefs and barriers to whole food plant-based diets amongst registered dietitians in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 2025;38:e13386.

- Land schafft Leben (2024). Umfrage: 82 % der Schüler*innen ist gesundes Schulessen wichtig. OTS, 15. Mai 2024. https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20240515_OTS0100/umfrage-82-der-schuelerinnen-ist-gesundes-schulessen-wichtig (18.4.2025).

- PULS 24 (2024). Wunsch nach mehr gesundem Essen an Österreichs Schulen. Chronik, 15. Mai 2024. https://www.puls24.at/news/chronik/wunsch-nach-mehr-gesundem-essen-an-oesterreichs-schulen/328255 (18.4.2025).

- Bundesministerium für Bildung (BMB) (2025). Unterrichtsprinzipien. https://www.bmb.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulpraxis/prinz.html and https://www.bmb.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulpraxis/prinz/gesundheitsfoerderung.html (22.4.2025).

- Troppe I, Tanous DR, Wirnitzer KC (2024) Bewegung & Sport im Lead der schulischen Gesundheitsförderung – Ein systematischer Review der Primarstufen-Curricula in der D-A-CH Region im Kontext des Pflichtfächerkanons. Bewegung & Sport – Die Fachzeitschrift für den Unterricht in Schulen, Kindergärten und Vereinen, Themenheft 02/2024 „Gesund sein, glücklich sein“, Seite 7-12.

- Motevalli M, Stanford FC, Apflauer G, Wirnitzer KC (2025) Integrating lifestyle behaviors in school education: A proactive approach to preventive medicine. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2025, 102999. [CrossRef]

- Motevalli M, Apflauer G, Wirnitzer KC (2024). Ist der Sportunterricht „fit for the future“? – Eine Perspektive zur Notwendigkeit, den Bewegungs- und Sportunterricht aufzuwerten, zu modernisieren und transformieren. In: Gross et al. (Hrsg.) Transfer Forschung <-> Schule. Heft 10. Nachhaltig gesund – bewegen, essen, kompetenzorientiert lernen: 162-172. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt: https://www.klinkhardt.de/verlagsprogramm/2683.html.

- Armstrong, L. E., and Johnson, E. C. (2018). Water Intake, Water Balance, and the Elusive Daily Water Requirement. Nutrients. 10(12).

- Montenegro-Bethancourt, G., Johner, S. A., and Remer, T. (2013). Contribution of fruit and vegetable intake to hydration status in schoolchildren. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 98(4): 1103–1112.

- Orlich, M. J., Jaceldo-Siegl, K., Sabaté, J., Fan, J., Singh, P. N., and Fraser, G. E. (2014). Patterns of food consumption among vegetarians and non-vegetarians. British Journal of Nutrition. 112(10): 1644–1653.

- Alewaeters, K., Clarys, P., Hebbelinck, M., Deriemaeker, P., and Clarys, J. P. (2005). Cross-sectional analysis of BMI and some lifestyle variables in Flemish vegetarians compared with non-vegetarians. Ergonomics. 48(11-14): 1433–1444.

- Fu, J., Hofker, M., and Wijmenga, C. (2015). Apple or pear: size and shape matter. Cell Metabolism. 21(4): 507–508.

- Buchmann, M., Jordan, S., Loer, A.-K. M., Finger, J. D., and Domanska, O. M. (2023). Motivational readiness for physical activity and health literacy: results of a cross-sectional survey of the adult population in Germany. BMC Public Health. 23(1): 331.

- Rothland, M.; Klusmann, U. Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. In Enzyklopädie Erziehungswissenschaft Online (EEO); Rahm, S., Nerowski, C., Eds.; Fachgebiet Schulpädagogik; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2012.

- Barber M, Mourshed M. How the world’s best-performing school systems come out on top. McKinsey & Company. 9/1/2007.

- Agirbasli M, Tanrikulu AM, Berenson GS. Metabolic Syndrome: Bridging the Gap from Childhood to Adulthood. Cardiovasc Ther. 2016 Feb;34(1):30-6. [CrossRef]

- Delaney L, Smith JP. Childhood health: trends and consequences over the life course. Future Child. 2012 Spring;22(1):43-63. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. (2025). https://sdgs.un.org/goals. (22.04.2025).

- UNESCO. Cross-cutting competencies. (2025). https://www.unsdglearn.org/unesco-cross-cutting-and-specialized-sdg-competencies/. (22.04.2025).

- UNESCO (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: learning objectives, pp. 66. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (18.4.2025).

- Wong, L.S.; Gibson, A.-M.; Farooq, A.; Reilly, J.J. Interventions to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in elementary school physical education lessons: Systematic review. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 836–845.

- Hofmann, F et al. (2012): Gesundheit und Gesundheitsverhalten von Österreichs Lehrer*innen. Ergebnisse der Lehrer*innenbefragung 2010. Ludwig Boltzmann Institut - HPR, Wien.

- Schaarschmidt, Uwe/ Fischer, Andreas W. (2003): AVEM – Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster. Handanweisung. Swets & Zeitlinger, Frankfurt. 2. Auflage.

- Schuch S (2024). Gesundheit von Lehrpersonen - alle Schulstufen.; pp 60. GIVE-Servicestelle für Gesundheitsförderung an Österreichs Schulen https://www.give.or.at/material/lehrerinnen-gesundheit/ (3.4.2025).

- FRICK, Jürg (2015): Gesund bleiben im Lehrberuf. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber, Hogrefe AG, ISBN 978-3-456-85474-8.

- BANGERT, Carsten (2005): Mit aktivem Selbstmanagement zu mehr Gesundheit und Zufriedenheit im Lehrberuf. In: Tagungsband Lehrergesundheit. Praxisrelevante Modelle zur nachhaltigen Gesundheitsförderung von Lehrern auf dem Prüfstand. Dortmund, Berlin, Dresden: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin (Hrsg.), S. 57–74. www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/Publikationen/Schriftenreihe/Tagungsberichte/Tb141.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (3.4.2025).

- Grieben C & Froböse I (2016). Was hält Lehrkräfte gesund? – Was bewirkt Bewegung? pp. 40-45. In: Forum Schulstiftung (2016). Forum Schulstiftung, 64. Schwerpunkt: Die Gesunde Lehr-Kraft. Zeitschrift für die katholischen freien Schulen der Erzdiözese Freiburg. 26. Jahrgang; pp. 82. ISSN 1611342x.

- Wang, X., and Cheng, Z. (2020). Cross-Sectional Studies: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Recommendations. Chest. 158(1S): S65-S71.

- Bärebring, L.; Palmqvist, M.; Winkvist, A.; Augustin, H. Gender differences in perceived food healthiness and food avoidance in a Swedish population-based survey: A cross sectional study. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 140.

- Ek, S. Gender differences in health information behaviour: A Finnish population-based survey. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 736–745.

| TOTAL | Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | |

| N=1,350 | 2.3% (n=31) | 5.2% (n=70) | 92.5% (n=1,249) | |

| Age ± SD (years) | 45.8 ± 11.4 | 43.6 ± 10.5 | 46.0 ± 11.4 | 45.8 ± 11.4 |

| Sex 1,2 | Males 30.3% (n=409) |

1.7% (n=7) | 2.4% (n=10) | 95.8% (n=392) |

| Females 69.7% (n=941) |

2.6% (n=24) | 6.4% (n=60) | 91.1% (n=857) | |

| Height (cm) | 171.2 ± 8.3 | 172.1 ± 11.6 | 169.5 ± 7.0 | 171.3 ± 8.3 |

| Body Weight (kg) 3 | 71.3 ± 14.6 | 68.2 ± 21.3 | 66.5 ± 10.9 | 71.6 ± 14.5 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.2 ± 4.0 | 22.7 ± 4.3 | 23.1 ± 3.1 | 24.3 ± 4.0 |

| Underweight4,5 | 2.6% (n=35) | 12.9% (n=2) | 1.4% (n=3) | 2.4% (n=30) |

| Normal weight | 63.0% (n=851) | 61.3% (n=21) | 72.9% (n=86) | 62.4% (n=744) |

| Overweight | 25.6% (n=345) | 16.1% (n=5) | 21.4% (n=20) | 26.0% (n=320) |

| Obese | 8.8% (n=119) | 9.7% (n=3) | 4.3% (n=6) | 9.0% (n=110) |

| Teaching Level | Middle School 33.8% (n=456) |

2.2% (n=10) | 6.6% (n=30) |

91.2% (n=416) |

| High School 46.7% (n=630) |

2.1% (n=13) | 4.3% (n=411) | 93.7% (n=590) | |

| Middle & High School Pooled 19.6% (n=264) |

3.0% (n=8) | 4.9% (n=13) | 92.0% (n=243) | |

| Employment Status | Full Time 77.9% (n=1,052) |

2.3% (n=24) | 4.7% (n=49) | 93.1% (n=979) |

| Part Time 22.1% (n=298) |

2.3% (n=7) | 7.0% (n=21) | 90.6% (n=270) | |

| Residence | Urban 37.7% (n=509) |

3.3% (n=17) | 6.7% (n=34) | 90.0% (n=458) |

| Rural 62.3% (n=841) |

1.7% (n=14) | 4.3% (n=36) | 94.1% (n=791) |

| TOTAL | Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | ||

| N=1,350 | 2.3% (n=31) | 5.2% (n=70) | 92.5% (n=1,249) | ||

| Dietary Motives | Health Animal welfare |

46.4% (n=627) | 48.4% (n=15) | 37.1% (n=26) | 46.9% (n=586) |

| 4% (n=54) | 29% (n=9) | 40% (n=28) | 1.4% (n=17) | ||

| Taste/Preference | 22.3% (n=305) | 3.2% (n=1) | 10% (n=7) | 23.8% (n=297) | |

| Environment protection | 1.6% (n=22) | 12.9% (n=4) | 5.7% (n=4) | 1.1% (n=14) | |

| Other | 6.4% (n=87) | 3.2% (n=1) | 1.4% (n=1) | 6.8% (n=85) | |

| Lifestyle Preferences | PA & Exercise | 70.8% (n=956) | 41.9% (n=13) | 31.4% (n=22) | 73.7% (n=921) |

| Sports lifestyle | 10.9% (n=147) | 3.2% (n=1) | 5.7% (n=4) | 11.4% (n=142) | |

| Vegetarian diet | 7.3% (n=99) | 3.2% (n=1) | 51.4% (n=36) | 5% (n=62) | |

| Vegetarian lifestyle | 2.4% (n=32) | 3.2% (n=1) | 5.7% (n=4) | 2.2% (n=27) | |

| Vegan diet | 1.1% (n=15) | 35.5% (n=11) | 4.3% (n=3) | 0.1% (n=1) | |

| Vegan lifestyle | 0.8% (n=11) | 9.7% (n=3) | 1.4% (n=1) | 0.6% (n=7) | |

| Alcohol | 5.9% (n=80) | 3.2% (n=1) | 4.3% (n=3) | 6.1% (n=76) | |

| Smoking | 1.3% (n=18) | 3.2% (n=1) | NA | 1.4% (n=17) |

|

TOTAL (N=1,350) |

Daily Fruit Intake 62.4% (n=842) |

Daily Vegetable Intake 72.2% (n=975) |

||||

| Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | |

| 77.4 (n=24) |

64.3 (n=45) |

61.9 (n=773) |

93.5 (n=29) |

92.9 (n=65) |

70.5 (n=881) |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 71.4 | 50.0 | 55.1 | 100 | 90.0 | 61.0 |

| Female | 79.2 | 66.7 | 65.0 | 91.7 | 93.3 | 74.9 |

| Teaching Level | ||||||

| Middle School | 80.0 (n=8) | 70.0 (n=21) | 63.0 (n=262) | 90.0 (n=9) | 93.3 (n=28) | 69.2 (n=288) |

| High School | 76.9 (n=10) | 66.7 (n=18) | 61.4 (n=362) | 92.3 (n=12) | 96.3 (n=26) | 70.3 (n=415) |

|

Middle & High School Pooled |

75.0 (n=6) | 53.8 (n=7) | 61.3 (n=149) | 100 (n=8) | 84.6 (n=11) | 73.3 (n=178) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 76.5 (n=13) | 58.8 (n=20) | 61.1 (n=280) | 100 (n=17) | 91.2 (n=31) | 73.6 (n=337) |

| Rural | 78.6 (n=11) | 69.4 (n=25) | 62.3 (n=493) | 85.7 (n=12) | 94.4 (n=34) | 68.8 (n=544) |

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Full Time | 70.8 (n=17) | 63.3 (n=31) | 59.7 (n=584) | 91.7 (n=22) | 93.9 (n=46) | 68.5 (n=671) |

| Part Time | 100 (n=7) | 66.7 (n=14) | 70.0 (n=189) | 100 (n=7) | 90.5 (n=19) | 77.8 (n=210) |

|

TOTAL (N=1,350) |

Alcohol 81.5% (n=1,100) |

Smoking 11.0% (n=149) |

||||

| Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivorous | |

| 77.4 (n=25) |

64.3 (n=54) |

61.9 (n=1,021) |

93.5 (n=2) |

92.9 (n=4) |

70.5 (n=142) |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 85.7 | 80.0 | 86.7 | 14.3 | 20.0 | 12.5 |

| Female | 79.2 | 76.7 | 79.5 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 10.9 |

| Teaching Level | ||||||

| Middle School | 80.0 (n=8) | 76.7 (n=23) | 78.6 (n=327) | N/A | 6.7 (n=2) | 13.5 (n=56) |

| High School | 76.9 (n=10) | 81.5 (n=22) | 85.4 (n=504) | 7.7 (n=1) | 7.4 (n=2) | 11.5 (n=68) |

|

Middle & High School Pooled |

87.5 (n=7) | 69.2 (n=9) | 78.2 (n=190) | 12.5 (n=1) | N/A | 7.4 (n=18) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 70.6 (n=12) | 85.3 (n=29) | 84.3 (n=386) | 11.8 (n=2) | 2.9 (n=1) | 12.2 (n=56) |

| Rural | 92.9 (n=13) | 69.4 (n=25) | 80.3 (n=635) | N/A | 8.3 (n=3) | 10.9 (n=86) |

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Full Time | 83.3 (n=20) | 77.6 (n=38) | 82.7 (n=810) | 8.3 (n=2) | 4.1 (n=2) | 11.8 (n=116) |

| Part Time | 71.4 (n=5) | 76.2 (n=16) | 78.1 (n=211) | N/A | 9.5 (n=2) | 9.6 (n=26) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).