Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

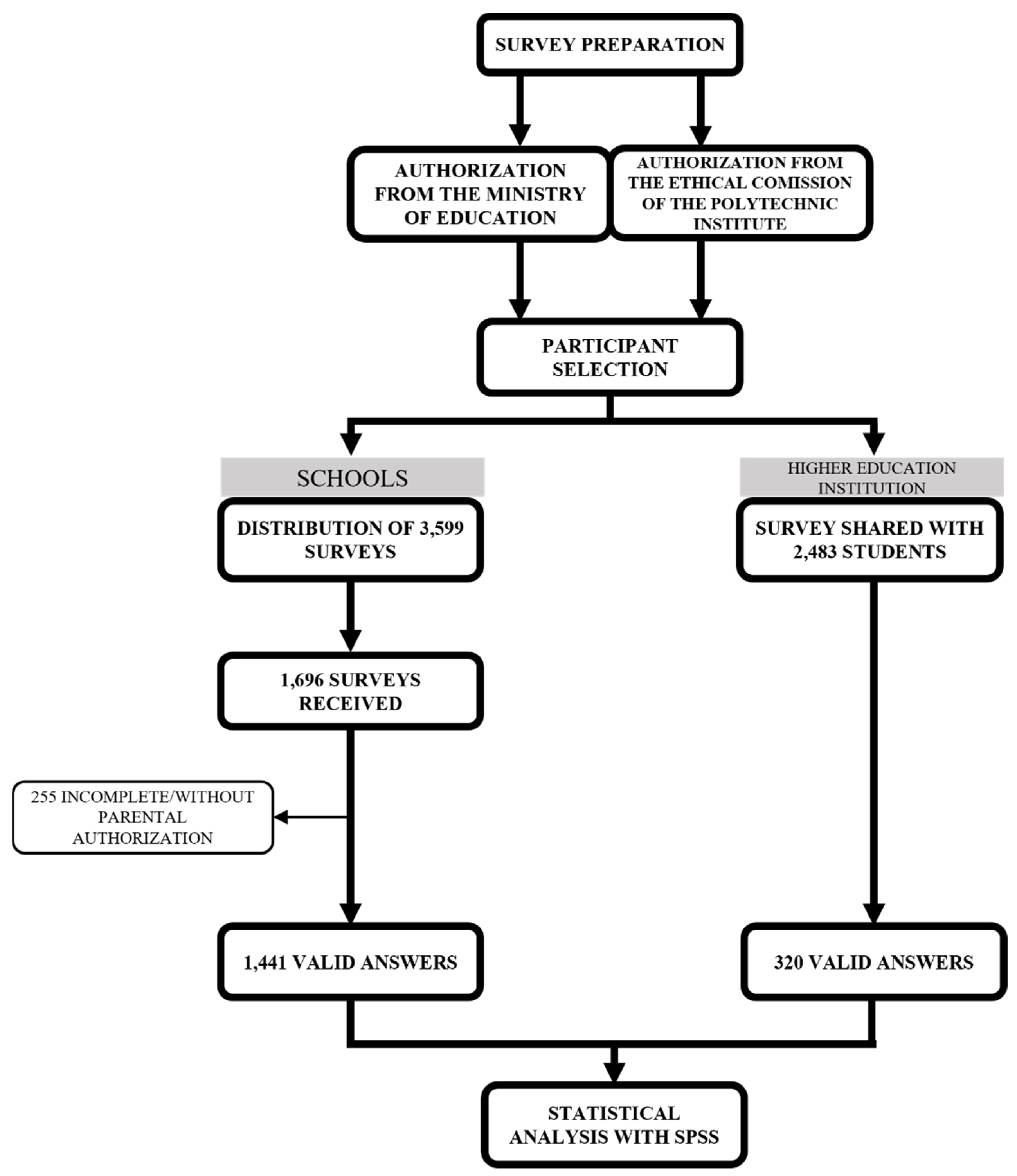

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Demographic Data

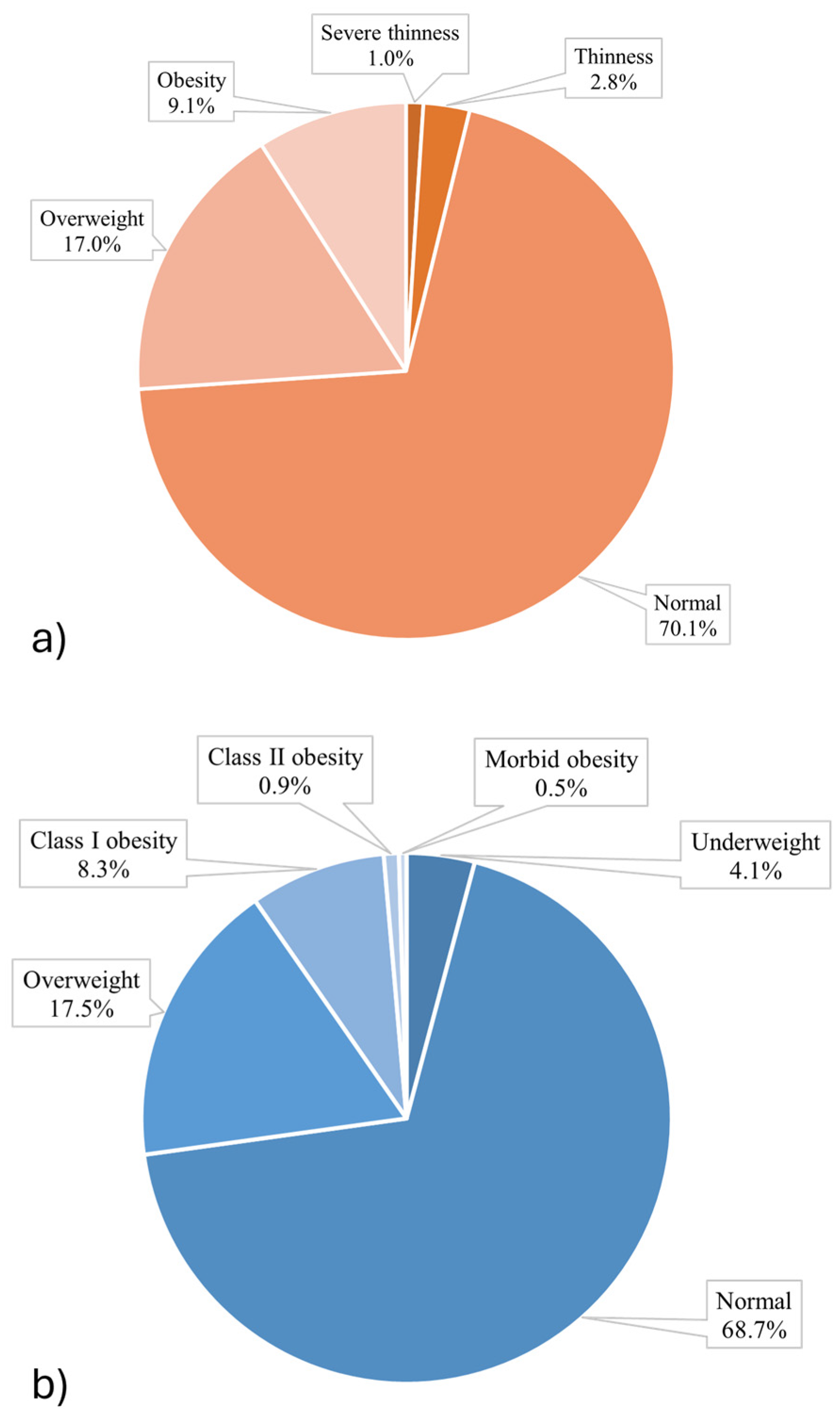

3.2. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Students

3.3. Weight Status According To Sociodemographic Characteristics And Life Habits Of The Students

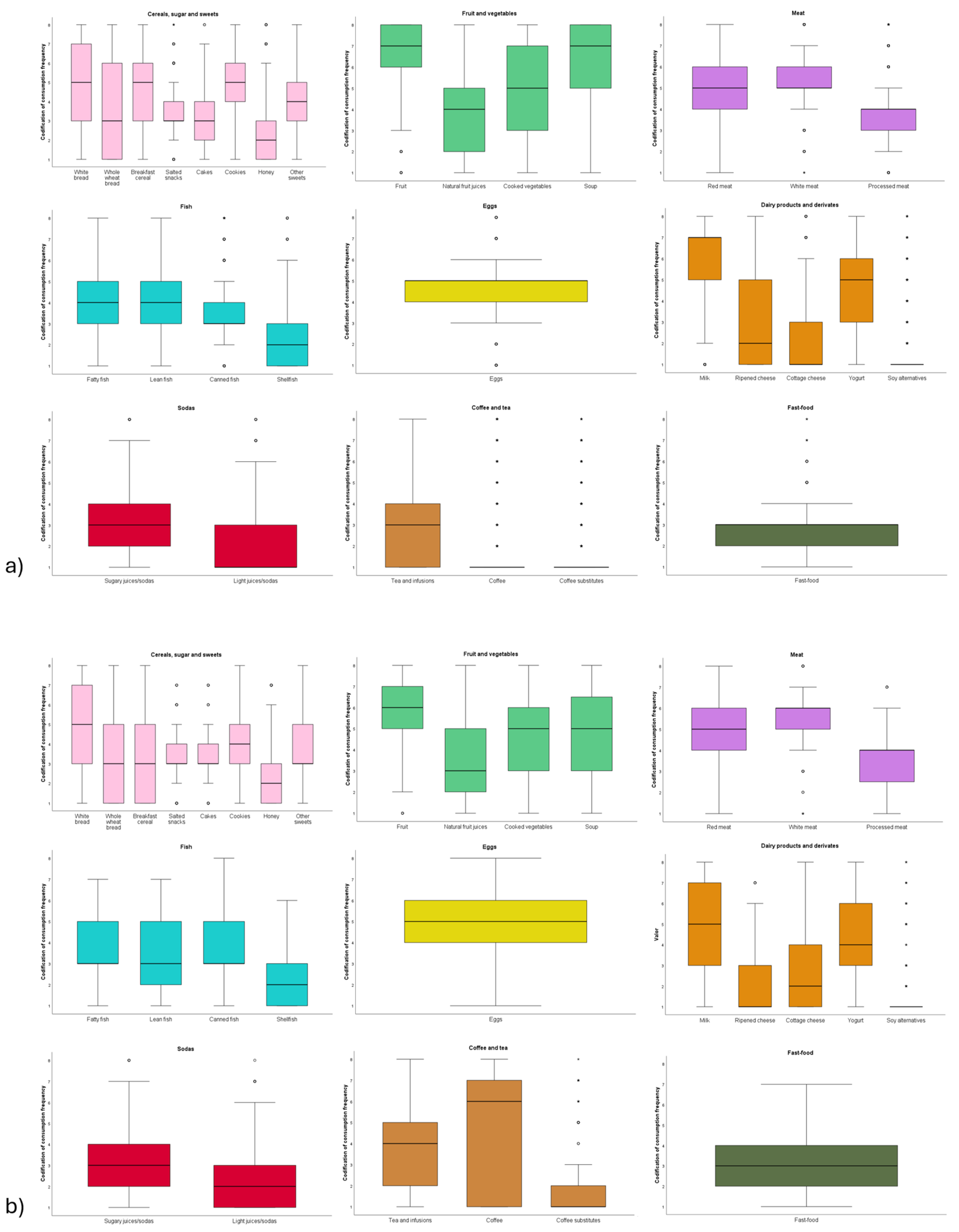

3.4. Food Habits of the Student Community

3.5. Disease Incidence In The Student Community

3.6. Logistic Regression Model

4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Story, M.; Nanney, M.S.; Schwartz, M.B. Schools and Obesity Prevention: Creating School Environments and Policies to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Milbank Q 2009, 87, 71–100. [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Global Obesity: Trends, Risk Factors and Policy Implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2013, 9, 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The Global Obesity Pandemic: Shaped by Global Drivers and Local Environments. The Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of School-Based Interventions with Health Education to Reduce Body Mass Index in Adolescents Aged 10 to 19 Years. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2021, 18.

- World Health Organization Obesity and Overweight Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Hruby, A.; Hu, F.B. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 673–689. [CrossRef]

- Guh, D.P.; Zhang, W.; Bansback, N.; Amarsi, Z.; Birmingham, C.L.; Anis, A.H. The Incidence of Co-Morbidities Related to Obesity and Overweight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 88. [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [CrossRef]

- Vollset, S.E.; Ababneh, H.S.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasian, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd Al Magied, A.H.A.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abdelkader, A.; et al. Burden of Disease Scenarios for 204 Countries and Territories, 2022–2050: A Forecasting Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 2024, 403, 2204–2256. [CrossRef]

- Hannon, T.S.; Rao, G.; Arslanian, S.A. Childhood Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 473–480. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.B.; Hashim, M.J.; King, J.K.; Govender, R.D.; Mustafa, H.; Al Kaabi, J. Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes – Global Burden of Disease and Forecasted Trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2019, 10, 107. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, M.; Huang, H.; Peng, K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Peng, X.; et al. Obesity Increases Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with HFmrEF. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Marquina, C.; Talic, S.; Vargas-Torres, S.; Petrova, M.; Abushanab, D.; Owen, A.; Lybrand, S.; Thomson, D.; Liew, D.; Zomer, E.; et al. Future Burden of Cardiovascular Disease in Australia: Impact on Health and Economic Outcomes between 2020 and 2029. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022, 29, 1212–1219. [CrossRef]

- Mohebi, R.; Chen, C.; Ibrahim, N.E.; McCarthy, C.P.; Gaggin, H.K.; Singer, D.E.; Hyle, E.P.; Wasfy, J.H.; Januzzi, J.L. Cardiovascular Disease Projections in the United States Based on the 2020 Census Estimates. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 80, 565–578. [CrossRef]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Planning for Tomorrow: Global Cancer Incidence and the Role of Prevention 2020–2070. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 663–672. [CrossRef]

- Batsis, J.A.; Zbehlik, A.J.; Barre, L.K.; Bynum, J.P.W.; Pidgeon, D.; Bartels, S.J. Impact of Obesity on Disability, Function, and Physical Activity: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Scand J Rheumatol 2015, 44, 495–502. [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. Obesity Stigma: Important Considerations for Public Health. Am J Public Health 2010, 100, 1019–1028. [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Portugal: Country Health Profile 2023, State of Health in the EU; Brussels, 2023.

- Rito, A.; Mendes, S.; Figueira, I.; Faria, M. do C.; Carvalho, R.; Santos, T.; Cardoso, S.; Feliciano, E.; Silvério, R.; Sofia Sancho, T.; et al. Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: COSI Portugal 2022; 2023.

- National Hearth, L. and B.I. Assessing Your Weight and Health Risk. 2024.

- Flegal, K.M.; Kit, B.K.; Orpana, H.; Graubard, B.I. Association of All-Cause Mortality With Overweight and Obesity Using Standard Body Mass Index Categories. JAMA 2013, 309, 71. [CrossRef]

- IAN-AF Questionário de Propensão Alimentar - QPA1; 2017.

- Keys, A.; Fidanza, F.; Karvonen, M.J.; Kimura, N.; Taylor, H.L. Indices of Relative Weight and Obesity. Int J Epidemiol 2014, 43, 655–665. [CrossRef]

- de Onis, M. Development of a WHO Growth Reference for School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007, 85, 660–667. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Body Mass Index-for-Age (BMI-for-Age) Available online: https://www.who.int/toolkits/child-growth-standards/standards/body-mass-index-for-age-bmi-for-age (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- World Health Organization A Healthy Lifestyle - WHO Recommendations Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- World Health Organization WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566046/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI).

- Ilić, M.; Pang, H.; Vlaški, T.; Grujičić, M.; Novaković, B. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Overweight and Obesity among Medical Students from the Western Balkans (South-East Europe Region). BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 29. [CrossRef]

- WHO European REGIONAL OBESITY REPORT 2022; 2022; ISBN 9789289057738.

- Ługowska, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. The Impact of Physical Activity at School on Children’s Body Mass during 2 Years of Observation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Cleven, L.; Krell-Roesch, J.; Nigg, C.R.; Woll, A. The Association between Physical Activity with Incident Obesity, Coronary Heart Disease, Diabetes and Hypertension in Adults: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies Published after 2012. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 726. [CrossRef]

- Koolhaas, C.M.; Dhana, K.; Schoufour, J.D.; Ikram, M.A.; Kavousi, M.; Franco, O.H. Impact of Physical Activity on the Association of Overweight and Obesity with Cardiovascular Disease: The Rotterdam Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017, 24, 934–941. [CrossRef]

- El-Koofy, N.M.; Anwar, G.M.; El-Raziky, M.S.; El-Hennawy, A.M.; El-Mougy, F.M.; El-Karaksy, H.; Hassanin, F.M.; Helmy, H.M. The Association of Metabolic Syndrome, Insulin Resistance and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Overweight/Obese Children. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology 2012, 18, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Rajindrajith, S.; Devanarayana, N.M.; Benninga, M.A. Obesity and Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases in Children. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014, 20, 414–416. [CrossRef]

- Vila, G. Mental Disorders in Obese Children and Adolescents. Psychosom Med 2004, 66, 387–394. [CrossRef]

- Propst, M.; Colvin, C.; Griffin, R.L.; Sunil, B.; Harmon, C.M.; Yannam, G.; Johnson, J.E.; Smith, C.B.; Lucas, A.P.; Diaz, B.T.; et al. Diabetes and Prediabetes Are Significantly Higher in Morbidly Obese Children Compared With Obese Children. Endocrine Practice 2015, 21, 1046–1053. [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.Y.; Hetti Pathirannahalage, D.M.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Austin, S.B.; Le, L. Global Prevalence of Adolescent Use of Nonprescription Weight-Loss Products: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, E2350940. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Louis, G.; Williams, N.J.; Sarpong, D.; Pandey, A.; Youngstedt, S.; Zizi, F.; Ogedegbe, G. Associations between Inadequate Sleep and Obesity in the US Adult Population: Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey (1977–2009). BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 290. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yu, T.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Yu, J. Poor Sleep Quality and Overweight/Obesity in Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Public Health 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Dare, S.; Mackay, D.F.; Pell, J.P. Relationship between Smoking and Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study of 499,504 Middle-Aged Adults in the UK General Population. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0123579. [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.M.; Wadden, T.A.; Ashare, R.L.; Loughead, J.; Schmidt, H.D. Tobacco Smoking, Eating Behaviors, and Body Weight: A Review. Curr Addict Rep 2019, 6, 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Traversy, G.; Chaput, J.-P. Alcohol Consumption and Obesity: An Update. Curr Obes Rep 2015, 4, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- AlKalbani, S.R.; Murrin, C. The Association between Alcohol Intake and Obesity in a Sample of the Irish Adult Population, a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2075. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Cardel, M.; T Donahoo, W. Social and Environmental Factors Influencing Obesity Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278977/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Zhu, X.; Haegele, J.A.; Liu, H.; Yu, F. Academic Stress, Physical Activity, Sleep, and Mental Health among Chinese Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Giacco, R.; Della Pepa, G.; Luongo, D.; Riccardi, G. Whole Grain Intake in Relation to Body Weight: From Epidemiological Evidence to Clinical Trials. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2011, 21, 901–908.

- Askari, G.; Heidari-Beni, M.; Broujeni, M.B.; Ebneshahidi, A.; Amini, M.; Ghisvand, R.; Iraj, B. Effect of Whole Wheat Bread and White Bread Consumption on Pre-Diabetes Patient. Pak J Med Sci 2013, 29, 275–279. [CrossRef]

- WHO Technical Report Series Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization, Ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2003; Vol. 916; ISBN 924120916X.

- Shi, W.; Huang, X.; Schooling, C.M.; Zhao, J. V Red Meat Consumption, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 2626–2635. [CrossRef]

- Vanessa Candeias; Emília Nunes; Cecília Morais; Manuela Cabral; Pedro Ribeiro da Silva Princípios Para Uma Alimentação Saudável: Ministério Da Saúde. 2005.

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Mante Angua, K.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat and Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2021, 36, 937–951. [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington DC: AICR, 2007; ISBN 978-0-9722522-2-5.

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition Iron and Health; Stationery Office: London, 2010; ISBN 9780117069923.

- Lyall, K.; Westlake, M.; Musci, R.J.; Gachigi, K.; Barrett, E.S.; Bastain, T.M.; Bush, N.R.; Buss, C.; Camargo, C.A.; Croen, L.A.; et al. Association of Maternal Fish Consumption and ω-3 Supplement Use during Pregnancy with Child Autism-Related Outcomes: Results from a Cohort Consortium Analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2024, 120, 583–592. [CrossRef]

- Witte, A.V.; Kerti, L.; Hermannstädter, H.M.; Fiebach, J.B.; Schreiber, S.J.; Schuchardt, J.P.; Hahn, A.; Flöel, A. Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids Improve Brain Function and Structure in Older Adults. Cerebral Cortex 2014, 24, 3059–3068. [CrossRef]

- European Commission Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Recommendations for Eggs Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/food-based-dietary-guidelines-europe-table-10_en (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- European Commission Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Recommendations for Milk and Dairy Products Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/food-based-dietary-guidelines-europe-table-7_en (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- World Health Organization Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children; Genova, 2015.

- Branum, A.M.; Rossen, L.M.; Schoendorf, K.C. Trends in Caffeine Intake among US Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 386–393. [CrossRef]

- Poti, J.M.; Duffey, K.J.; Popkin, B.M. The Association of Fast Food Consumption with Poor Dietary Outcomes and Obesity among Children: Is It the Fast Food or the Remainder of the Diet? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014, 99, 162–171. [CrossRef]

- Paeratakul, S.; Ferdinand, D.P.; Champagne, C.M.; Ryan, D.H.; Bray, G.A. Fast-Food Consumption among US Adults and Children: Dietary and Nutrient Intake Profile. J Am Diet Assoc 2003, 103, 1332–1338. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, R.S.; Wilkinson Enns, C.; Goldman, J.D. US Adolescents and MyPyramid: Associations between Fast-Food Consumption and Lower Likelihood of Meeting Recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc 2009, 109, 226–235. [CrossRef]

- Jekanowski, M.D.; Binkley, J.K.; Eales, J. Convenience, Accessibility, and the Demand for Fast Food; 2001; Vol. 26.

- Peixoto, J.M. Characterization of Caffeine Consumption in the Portuguese Population and Its Relationship with Psychological Well-Being, Universidade Católica: Porto, 2020.

- Ikram, M.; Park, T.J.; Ali, T.; Kim, M.O. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects of Caffeine against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: Insight into the Role of Nrf-2 and A2AR Signaling. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–21.

- Jin, M.-J.; Yoon, C.-H.; Ko, H.-J.; Kim, H.-M.; Kim, A.-S.; Moon, H.-N.; Jung, S.-P. The Relationship of Caffeine Intake with Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Sleep in Korean Adolescents. Korean J Fam Med 2016, 37, 111. [CrossRef]

- Tohill, B.C.; oint FAO/WHO Workshop on Fruit and Vegetables for Health Dietary Intake of Fruit and Vegetables and Management of Body Weight; Kobe, 2005.

- Henn, M.; Glenn, A.J.; Willett, W.C.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Changes in Coffee Intake, Added Sugar and Long-Term Weight Gain - Results from Three Large Prospective US Cohort Studies. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2023, 118, 1164–1171. [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, I.; Bodilly, L.; Kaplan, J. The Impact of Obesity on Critical Illnesses. Shock 2021, 56, 691–700.

- Edwards-Salmon, S.E.; Padmanabhan, S.L.; Kuruvilla, M.; Levy, J.M. Increasing Prevalence of Allergic Disease and Its Impact on Current Practice. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2022, 10, 278–284.

- Sultész, M.; Horváth, A.; Molnár, D.; Katona, G.; Mezei, G.; Hirschberg, A.; Gálffy, G. Prevalence of Allergic Rhinitis, Related Comorbidities and Risk Factors in Schoolchildren. Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology 2020, 16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, J.; Peng, S.; Xie, L. Prenatal and Early-Life Exposure to Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Allergic Rhinitis in Children: A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS One 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Kowal, M.; Woronkowicz, A.; Kryst, Ł.; Sobiecki, J.; Pilecki, M.W. Sex Differences in Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity, and in Extent of Overweight Index, in Children and Adolescents (3-18 Years) from Kraków, Poland in 1983, 2000 and 2010. Public Health Nutr 2016, 19, 1035–1046. [CrossRef]

- Rodd, C.; Sharma, A.K. Recent Trends in the Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Canadian Children. CMAJ 2016, 188, E313–E320. [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Tombeau Cost, K.; Fuller, A.; Birken, C.S.; Anderson, L.N. Sex and Gender Differences in Childhood Obesity: Contributing to the Research Agenda. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 2020, 3, 387–390. [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, D.; Fridolfsson, J.; Börjesson, M. Measurement of Physical Activity in Clinical Practice Using Accelerometers. J Intern Med 2019, 286, 137–153. [CrossRef]

| BMI | Weight classification | |

| < 18.5 | Underweight | |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | Normal weight | |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | Overweight | |

| 30.0 – 34.9 | Obesity class I | Obese |

| 35.0 – 39.9 | Obesity class II | |

| ≥ 40 | Obesity class III (morbid) | |

| Male BMI classification(n=670) | Female BMI classification(n=875) | ||||||||||

| Underweight/Normal weight | Overweight/Obesity | P-value | Underweight/Normal weight | Overweight/Obesity | P-Value | ||||||

| n | % (CI) | n | % (CI) | n | % (CI) | n | % (CI) | ||||

| Age in years | 6 - 12 | 299 | 66.6(62.1-70.8) | 150 | 33.4(29.2-37.9) | 0.050 | 387 | 72.6(68.7-76.3) | 146 | 27.4(23.7-31.3) | <0.001 |

| 13 - 19 | 164 | 74.2(68.2-79.6) | 57 | 25.8(20.4-31.8) | 292 | 85.4(81.3-88.8) | 50 | 14.6(11.2-18.7) | |||

| Frequency of weekly physical activity | Low | 188 | 65.7(60.1-71.1) | 98 | 34.3(28.9-39.9) | 0.031 | 368 | 73.7(69.8-77.5) | 131 | 26.3(22.5-30.2) | 0.002 |

| Moderate | 157 | 67.7(61.5-73.4) | 75 | 32.3(26.6-38.5) | 222 | 80.7(75.8-85.1) | 53 | 19.3(14.9-24.2) | |||

| Heavy | 118 | 77.6(70.5-83.7) | 34 | 22.4(16.3-29.5) | 89 | 88.1(80.8-93.3) | 12 | 11.9(6.7-19.2) | |||

| Hours of sleep per day | < 6 | 10 | 55.6(33.2-76.3) | 8 | 44.4(23.7-66.8) | 0.207 | 36 | 75.0(61.5-85.5) | 12 | 25.0(14.5-38.5) | 0.721 |

| ≥ 6 | 453 | 69.5(65.9-72.9) | 199 | 30.5(27.17-34.1) | 643 | 77.8(74.8-80.5) | 184 | 22.2(19.5-25.2) | |||

| Hours spent sitting down, daily during the week | < 6 | 150 | 70.1(63.7-75.9) | 64 | 29.9(24.1-36.3) | 0.721 | 181 | 73.3(67.5-78.5) | 66 | 26.7(21.5-32.5) | 0.059 |

| ≥ 6 | 313 | 68,6(64.3-72.8) | 143 | 31.4(27.2-35.7) | 498 | 79.3(76.0-82.3) | 130 | 20.7(17.7-24.0) | |||

| Hours spent sitting down, daily during the weekend | < 6 | 322 | 70.5(66.2-74.5) | 135 | 29.5(25.5-33.8) | 0.282 | 461 | 78.1(74.5-81.2) | 130 | 22.0(18-8-25.5) | 0.729 |

| ≥ 6 | 141 | 66.2(59.7-72.3) | 72 | 33.8(27.7-40.3) | 218 | 76.8(71.6-81.4) | 66 | 23.2(18.6-28.4) | |||

| Number of daily meals | ≤ 3 | 50 | 64.9(53.9-74.9) | 27 | 35.1(25.1-46.1) | 0.432 | 95 | 81.2(73.4-87.5) | 22 | 18.8(12.5-26.6) | 0.343 |

| > 3 | 413 | 69.6(65.9-73.2) | 180 | 30.4(26.8-34.1) | 584 | 77.0(74.0-79.9) | 174 | 23.0(20.1-26.0) | |||

| Diagnosed with disease(s) | Yes | 148 | 63.8(57.5-69.8) | 84 | 36.2(30.2-42.5) | 0.035 | 229 | 78.2(73.2-82.6) | 64 | 21.8(17.4-26.8) | 0.797 |

| No | 315 | 71.9(67.5-76.0) | 123 | 28.1(24.0-32.4) | 450 | 77.3(73.8-80.6) | 132 | 22.7(19.4-26.2) | |||

| Medication | Yes | 66 | 70.2(60.5-78.7) | 28 | 29.8(21.3-39.5) | 0.904 | 90 | 79.6(71.5-86.3) | 23 | 20.4(13.7-28.5) | 0.630 |

| No | 397 | 68.9(65.1-72.6) | 179 | 31.1(27.4-34.9) | 589 | 77.3(74.2-80.2) | 173 | 22.7(19.8-25.8) | |||

| Dietary supplementation | Yes | 45 | 58.4(47.3-69.0) | 32 | 41.6(31.0-52.7) | 0.036 | 66 | 77.6(68.1-85.5) | 19 | 22.4(14.5-32.0) | 1.000 |

| No | 418 | 70.5(66.7-74.1) | 175 | 29.5(25.9-33.3) | 613 | 77.6(74.6-80.4) | 177 | 22.4(19.6-25.4) | |||

| Male BMI classification(n=76) | Female BMI classification(n=141) | ||||||||||

| Underweight/Normal weight | Overweight/Obesity | P-value | Underweight/Normal weight | Overweight/Obesity | P-Value | ||||||

| n | % (C.I.) | n | % (C.I.) | n | % (C.I.) | n | % (C.I.) | ||||

| Age in years | 20 - 39 | 49 | 70.0(58.6-79.8) | 21 | 30.0(20.2-41.4) | 0.087 | 101 | 75.9(68.2-82.6) | 32 | 24.1(17.4-31.8) | 1.000 |

| 40 - 58 | 2 | 33.3(7.70-71.4) | 4 | 66.7(28.6-92.3) | 6 | 75.0(40.8-94.4) | 2 | 25.0(5.6-59.2) | |||

| Frequency of weekly physical activity | Low | 29 | 64.4(49.9-77.2) | 16 | 35.6(22.8-50.1) | 0.647 | 68 | 74.7(65.1-82.8) | 23 | 25.3(17.2-34.9) | 0.894 |

| Moderate | 13 | 76.5(53.3-91.5) | 4 | 23.5(8.5-46.7) | 20 | 76.9(58.5-89.7) | 6 | 23.1(10.3-41.5) | |||

| Heavy | 9 | 64.3(38.5-84.9) | 5 | 35.7(15.1-61.5) | 19 | 79.2(60.2-91.6) | 5 | 20.8(8.4-39.8) | |||

| Hours of sleep per day | < 6 | 11 | 64.7(41.1-83.7) | 6 | 35.3(16.3-58.9) | 1.000 | 19 | 82.6(63.8-93.8) | 4 | 17.4(6.2-36.2) | 0.595 |

| ≥ 6 | 40 | 67.8(55.2-78.6) | 19 | 32.2(21.4-44.8) | 88 | 74.6(66.2-81.8) | 30 | 25.4(18.2-33.8) | |||

| Hours spent sitting down, daily, during the week | < 6 | 24 | 68.6(52.2-82.0) | 11 | 31.4(18.0-47.8) | 1.000 | 42 | 77.8(65.4-87.2) | 12 | 22.2(18.2-34.6) | 0.840 |

| ≥ 6 | 27 | 65.9(50.7-78.9) | 14 | 34.1(21.1-49.3) | 65 | 74.7(64.9-82.9) | 22 | 25.3(17.1-35.1) | |||

| Hours spent sitting down, daily, during the weekend | < 6 | 36 | 67.9(54.7-79.3) | 17 | 32.1(20.7-45.3) | 1.000 | 65 | 77.4(67.6-85.3) | 19 | 22.6(14.7-32.4) | 0.690 |

| ≥ 6 | 15 | 65.2(44.9-82.0) | 8 | 34.8(18.0-55.1) | 42 | 73.7(61.3-83.7) | 15 | 26.3(16.3-38.7) | |||

| Number of daily meals | ≤ 3 | 24 | 68.6(52.2-82.0) | 11 | 31.4(18.0-47.8) | 1.000 | 35 | 67.3(53.9-78.9) | 17 | 32.7(21.1-46.1) | 0.102 |

| > 3 | 27 | 65.9(50.7-78.9) | 14 | 34.1(21.1-49.3) | 72 | 80.9(71.8-88.0) | 17 | 19.1(12.0-28.2) | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 13 | 76.5(53.3-91.5) | 4 | 23.5(8.5-46.7) | 0.398 | 14 | 51.9(33.6-69.7) | 13 | 48.1(30.3-66.4) | 0.002 |

| No | 38 | 64.4(51.7-75.7) | 21 | 35.6(24.3-48.3) | 93 | 81.6(73.7-87.9) | 21 | 18.4(12.1-26.3) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 17 | 53.1(36.2-69.5) | 15 | 46.9(30.5-63.8) | 0.047 | 15 | 65.2(44.9-82.0) | 8 | 34.8(18.0-55.1) | 0.194 |

| No | 34 | 77.3(63.4-87.7) | 10 | 22.7(12.3-36.6) | 92 | 78.0(69.9-84.7) | 26 | 22.0(15.3-30.1) | |||

| Opioids consumption | Yes | 3 | 75.0(28.4-97.2) | 1 | 25.0(2.8-71.6) | 1.000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| No | 48 | 66.7(55.3-76.7) | 24 | 33.3(23.3-44.7) | 107 | 75.9(68.3-82.4) | 34 | 24.1(17.6-31.7) | |||

| Diagnosed with disease(s) | Yes | 23 | 65.7(49.2-79.7) | 12 | 34.3(20.3-50.8) | 1.000 | 65 | 75.6(65.8-83.7) | 21 | 24.4(16.3-34.2) | 1.000 |

| No | 28 | 68.3(53.2-80.9) | 13 | 31.7(19.1-46.8) | 42 | 76.4(64.6-86.1) | 13 | 23.6(13.9-36.0) | |||

| Medication | Yes | 4 | 50.0(19.9-80.1) | 4 | 50.0(19.9-80.1) | 0.427 | 35 | 71.4(57.8-82.6) | 14 | 28.6(17.4-42.2) | 0.411 |

| No | 47 | 69.1(57.5-79.1) | 21 | 30.9(20.9-42.5) | 72 | 78.3(69.0-85.7) | 20 | 21.7(14.3-31.0) | |||

| Dietary supplementation | Yes | 10 | 76.9(50.3-93.0) | 3 | 23.1(7.0-49.7) | 0.526 | 23 | 79.3(62.2-90.9) | 6 | 20.7(9.1-37.8) | 0.808 |

| No | 41 | 65.1(52.8-76.0) | 22 | 34.9(24.0-47.2) | 84 | 75.0(66.4-82.3) | 28 | 25.0(17.7-33.6) | |||

| Memory enhancement supplementation | Yes | 5 | 38.5(16.5-65.0) | 8 | 61.5(35.0-83.5) | 0.024 | 16 | 61.5(42.4-78.2) | 10 | 38.5(21.8-57.6) | 0.075 |

| No | 46 | 73.0(61.2-82.8) | 17 | 27.0(17.2-38.8) | 91 | 79.1(71.0-85.8) | 24 | 20.9(14.2-29.0) | |||

| Children | Adults | ||||

| Number of students | Percentage | Number of students | Percentage | ||

| Diagnosed with diseases(s) | Yes | 525 | 34.0% | 121 | 55.8% |

| No | 1020 | 66.0% | 96 | 44.2% | |

| Diagnosis | Allergic diseases | 279 | 18.1% | 71 | 32.7% |

| Pulmonary diseases | 126 | 8.2% | 24 | 11.1% | |

| Skin diseases | 122 | 7.9% | 22 | 10.1% | |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 52 | 3.4% | 17 | 7.8% | |

| Mental diseases | 37 | 2.4% | 20 | 9.2% | |

| Heart diseases | 29 | 1.9% | 6 | 2.8% | |

| Blood diseases | 26 | 1.7% | 5 | 2.3% | |

| Kidney diseases | 23 | 1.5% | 8 | 3.7% | |

| Bone diseases | 21 | 1.4% | 5 | 2.3% | |

| Metabolic diseases | 15 | 1.0% | 7 | 3.2% | |

| Hypertension | 11 | 0.7% | 11 | 5.1% | |

| Type 1 Diabetes | 5 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.5% | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 5 | 0.3% | 3 | 1.4% | |

| Cancer | 1 | 0.1% | 1 | 0.5% | |

| Stroke | 1 | 0.1% | 2 | 0.9% | |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 9.5% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Children | |||||||||

| Step 5 | Age | -0.137 | 0.026 | 27.127 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.872 | 0.829 | 0.918 |

| Time of sleep per day | -0.561 | 0.144 | 15.071 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.571 | 0.430 | 0.758 | |

| Hours spent sitting down, daily, during the weekend | 0.288 | 0.090 | 10.369 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.334 | 1.119 | 1.590 | |

| Cookies | -0.168 | 0.050 | 11.264 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.845 | 0.767 | 0.933 | |

| Sex* | -0.576 | 0.160 | 12.907 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.562 | 0.410 | 0.770 | |

| Constant | 2.704 | 0.736 | 13.489 | 1 | <0.001 | 14.934 | |||

| Adults | |||||||||

| Step 6 | Cookies | 0.307 | 0.128 | 5.703 | 1 | 0.017 | 1.359 | 1.057 | 1.748 |

| Soy alternatives | -0.840 | 0.329 | 6.534 | 1 | 0.011 | 0.432 | 0.227 | 0.822 | |

| Light sodas | 0.329 | 0.136 | 5.850 | 1 | 0.016 | 1.390 | 1.064 | 1.815 | |

| Tea and infusions | 0.307 | 0.115 | 7.094 | 1 | 0.008 | 1.359 | 1.084 | 1.702 | |

| Coffee | 0.258 | 0.082 | 9.867 | 1 | 0.002 | 1.295 | 1.102 | 1.521 | |

| Coffee substitutes | -0.320 | 0.131 | 5.981 | 1 | 0.014 | 0.726 | 0.562 | 0.938 | |

| Constant | -3.894 | 0.991 | 15.443 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.020 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).