Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Context

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis and Processing Procedures

2.5. Ethical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characterization

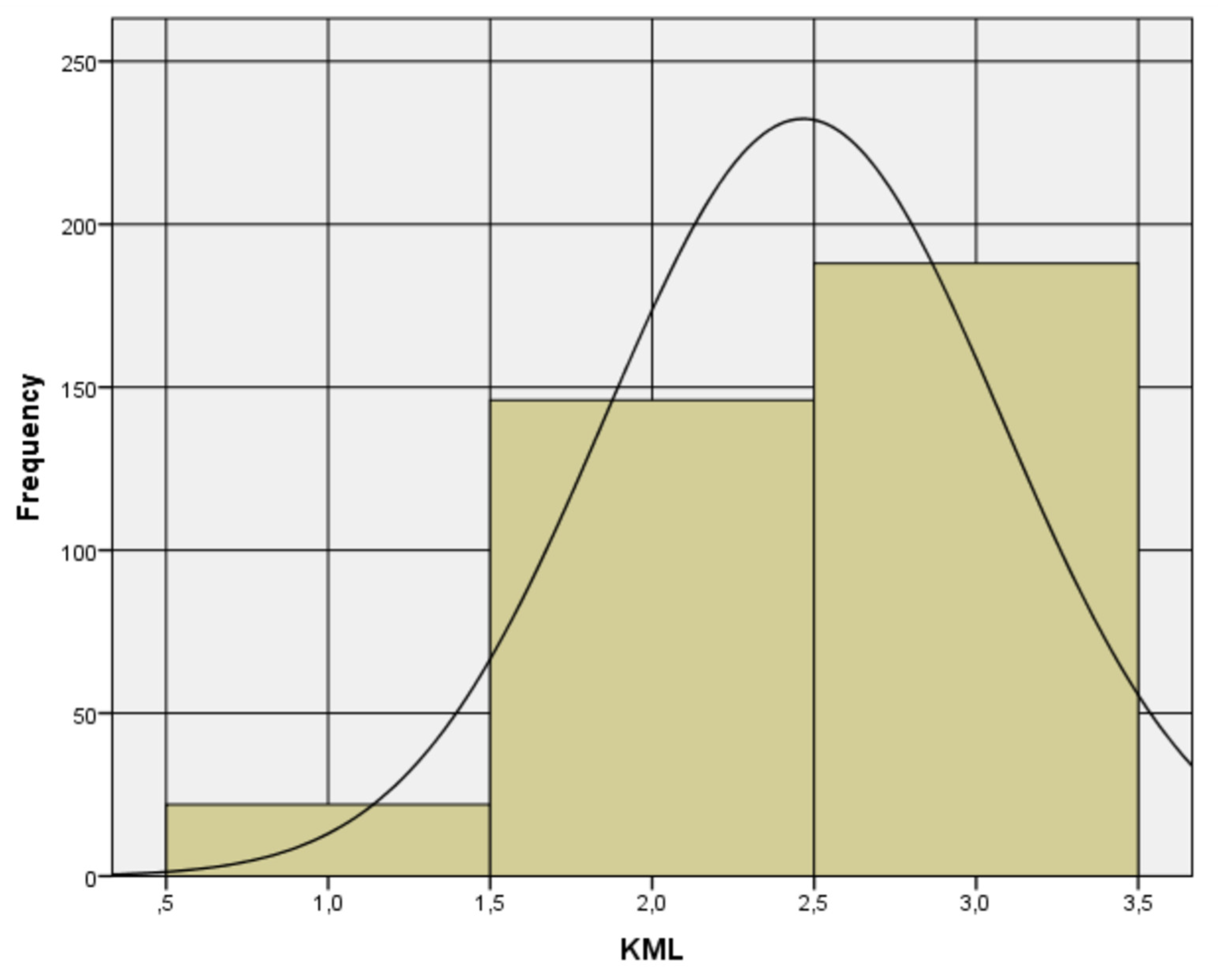

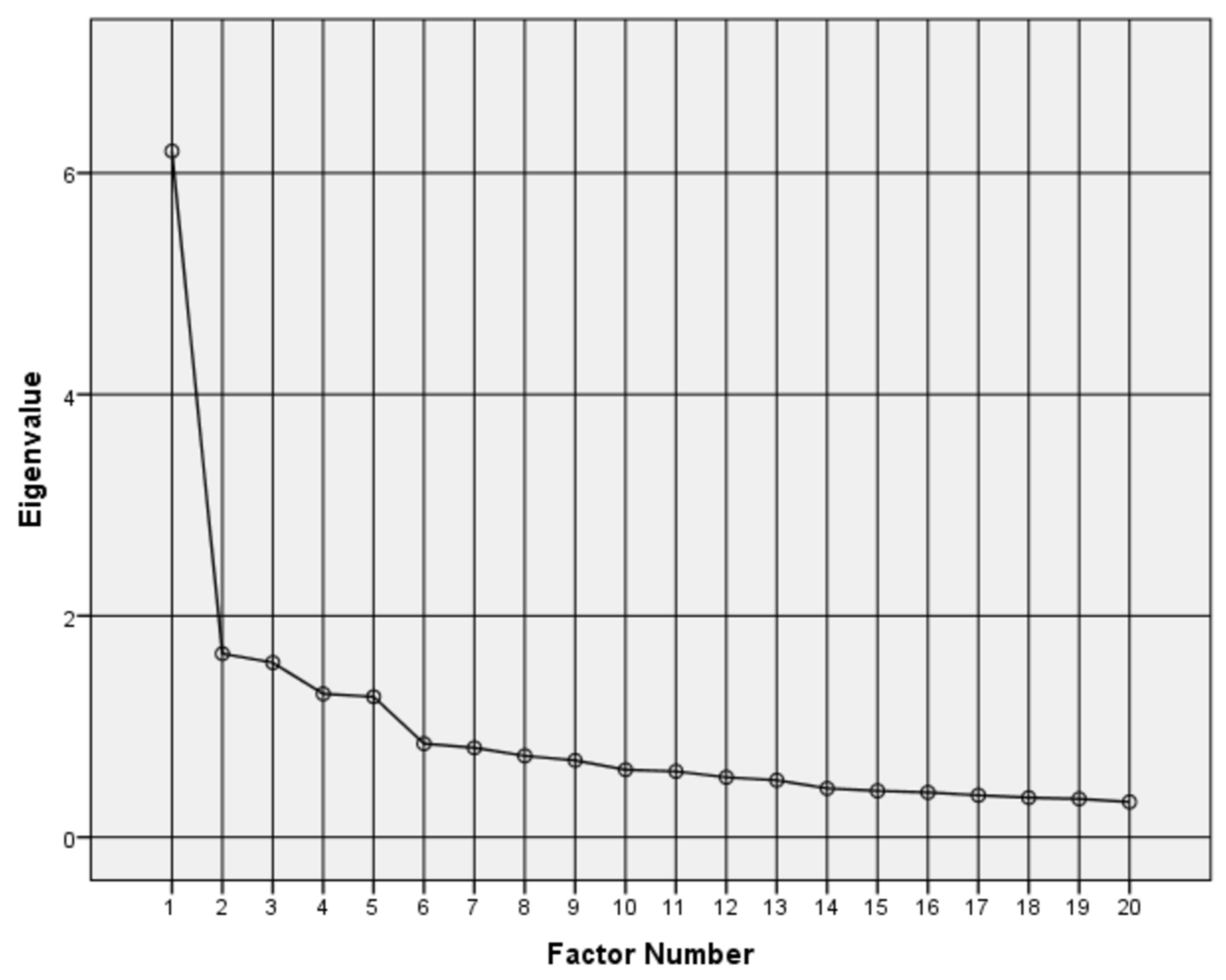

3.2. Validation by Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

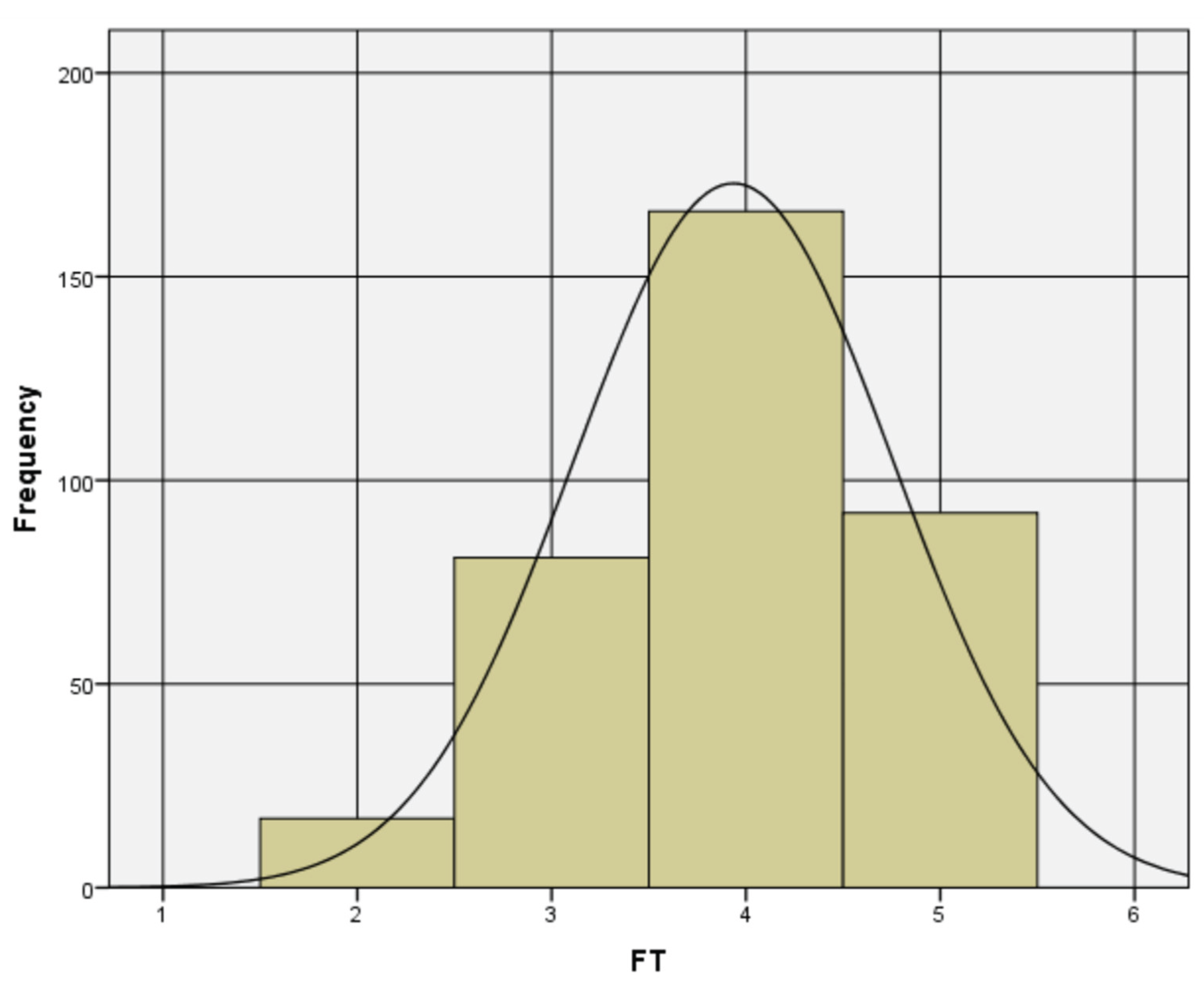

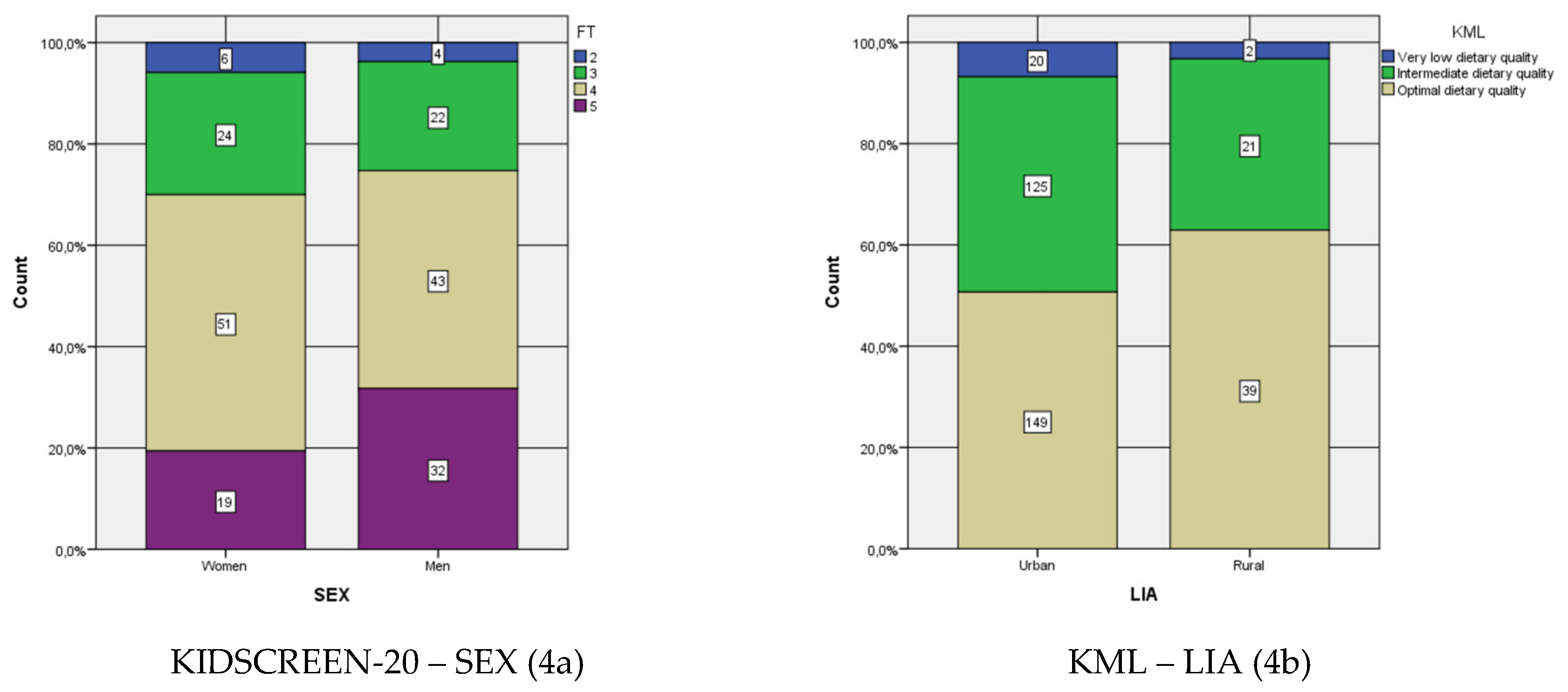

3.3. Resulting Scale Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4.2. Practical Recommendations

4.3. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vega-Salas, M.J.; Caro, P.; Johnson, L.; Armstrong, M.E.G.; Papadaki, A. Socioeconomic inequalities in physical activity and sedentary behaviour among the Chilean population: A systematic review of observational studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas (JUNAEB). Mapa Nutricional 2024: Resultados Abril de 2025; JUNAEB: Santiago, Chile, 2025; Available online: https://www.junaeb.cl/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/INFORME-MN_2024-1.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514187 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Obesidad y Sobrepeso 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Marti, A.; Calvo, C.; Martínez, A. Consumo de alimentos ultraprocesados y obesidad: Una revisión sistemática. Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Grandón, M.; Cerda, C.; León, M. Hábitos de vida saludable en estudiantes del sur de Chile. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juventud 2022, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kininmonth, A.R.; Schrempft, S.; Smith, A.; et al. Associations between the home environment and childhood weight change: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, F.; Steele, E.M.; Louzada, M.L.; Millett, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-processed food consumption and indicators of obesity in the United Kingdom population (2008–2016). Nutrients 2019, 11, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Dinu, M.; Madarena, M.P.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Sofi, F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Jaime, P.; Martins, A.P.B.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.C.; Araneda, J.; Dourado, D.Q.; et al. Diet quality of Chilean schoolchildren: How is it linked to adherence to dietary guidelines? PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausenhus, C.; Gold, J.M.; Perry, C.K.; et al. Factors impacting implementation of nutrition and physical activity policies in rural schools. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulló, M.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Mediterranean diet and oxidation: Nuts and olive oil as important sources of fat and antioxidants. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 1797–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Floody, P.; Alvarez, C.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Latorre-Román, P. Influence of Mediterranean diet adherence, physical activity patterns, and weight status on cardiovascular response to cardiorespiratory fitness test in Chilean school children. Nutrition 2020, 71, 110621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, H.E.; Carbone, S. The antioxidant potential of the Mediterranean diet in patients at high cardiovascular risk: An in-depth review of the PREDIMED. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Daniele, N.; Noce, A.; Vidiri, M.F.; Moriconi, E.; Marrone, G.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; et al. Impact of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome, cancer and longevity. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 8947–8979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augimeri, G.; Galluccio, A.; Caparello, G.; Avolio, E.; La Russa, D.; De Rose, D.; et al. Potential antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of serum from healthy adolescents with optimal Mediterranean diet adherence: Findings from DIMENU cross-sectional study. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez-López, L.; Santiago-Díaz, G.; Nava-Hernández, J.; Muñoz-Torres, A.V.; Medina-Bravo, P.; Torres-Tamayo, M. Mediterranean-style diet reduces metabolic syndrome components in obese children and adolescents with obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Erhart, M.; Bruil, J.; Duer, W.; et al. KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2005, 5, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Erhart, M.; Rajmil, L.; Herdman, M.; Auquier, P.; Bruil, J.; et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: A short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulló, M.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Mediterranean diet and oxidation: Nuts and olive oil as important sources of fat and antioxidants. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 1797–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, B.; Monteiro, D.; Silva, F.M.; Flores, G.; Bento, T.; Duarte-Mendes, P. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour on cardiovascular risk and health-related quality of life in adults: A systematic review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, S.; et al. Nutrition and cognitive health: A life course approach. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1023907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; et al. The effects of nutritional interventions on the cognitive development of preschool-age children: A systematic review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, B.; et al. Impact of nutritional minerals biomarkers on cognitive performance among Bangladeshi rural adolescents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Singer, S.; Pilpel, N.; Fradkin, A.; Modan, D.; Reichman, B. Health-related quality of life among children and adolescents: Associations with obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Voorn, B.; Camfferman, R.; Seidell, J.C.; Halberstadt, J. Health-related quality of life in children under treatment for overweight, obesity or severe obesity: A cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, E.; Camfferman, R.; Putten, L.R.; et al. Changes in the health-related quality of life and weight status of children with overweight or obesity aged 7 to 13 years after participating in a 10-week lifestyle intervention. Child Obes. 2020, 16, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Barahona, R.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Martínez-Salazar, C. Lifestyle associated with physical fitness related to health and cardiometabolic risk factors in Chilean schoolchildren. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2020, 67, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Urtubia, N.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Ureta-Paredes, W.; Carabantes-Silva, R. Relationship between body composition and physical literacy in Chilean children (10 to 16 years): An assessment using CAPL-2. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mosqueira, C.; Castillo Quezada, H.; Peña-Troncoso, S.; et al. Valoración del estado nutricional y la condición física de estudiantes de educación básica de Chile. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, A.; MacMillan Uribe, A.; De Mello, G.T.; Herrero-Loza, A.; Ali, M.; Nguyen, K.; et al. Educators’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing a school-based nutrition, physical activity, and civic engagement intervention: A qualitative analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1616483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, A.M.; Trost, S.G.; Howard, S.J.; Batterham, M.; Cliff, D.; Salmon, J.; et al. Evaluation of an intervention to reduce adolescent sitting time during the school day: The ‘Stand Up for Health’ randomised controlled trial. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausenhus, C.; Gold, J.M.; Perry, C.K.; Kozak, A.T.; Wang, M.L.; Jang, S.H.; et al. Factors impacting implementation of nutrition and physical activity policies in rural schools. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, E.; Koorts, H.; Salmon, J.; Pesce, C.; May, T.; Teo, W.P.; et al. Feasibility of breaking up sitting time in mainstream and special schools with a cognitively challenging motor task. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Farias, N.; Miranda-Marquez, S.; Toledo-Vargas, M.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Ibarra-Mora, J.; Martino-Fuentealba, P.; et al. Results from Chile’s 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2024, 22, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2017, 317, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. Obesity Prevention and Control: School-Based Programs; Community Preventive Services Task Force: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Obesity-School-based-Programs.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Aguilar-Farias, N.; Toledo-Vargas, M.; Miranda-Marquez, S.; Cortinez-O’Ryan, A.; Cristi-Montero, C.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, F.; Martino-Fuentealba, P.; Okely, A.D.; Del Pozo Cruz, B. Sociodemographic predictors of changes in physical activity, screen time, and sleep among toddlers and preschoolers in Chile during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, N.; Zeshan, M.; Pervaiz, Z. Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 pandemic. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, (COVID19–S4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, S.; Granese, M.; Maira, A. Efectos de la Pandemia en el Bienestar Socioemocional de los Niños y Adolescentes en Chile y el Mundo; Documento de trabajo CEP N°647; Centro de Estudios Públicos: Santiago, Chile, 2023; Available online: https://static.cepchile.cl/uploads/cepchile/2023/03/pder647_granese_etal.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A.K.; Sofi, N.Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Moore, T.H.; Hooper, L.; Gao, Y.; Zayegh, A.; Ijaz, S.; et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Urtubia, N.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; García-Gordillo, M.Á.; Carmelo-Adsuar, J. Physical activity-based interventions for reducing body mass index in children aged 6–12 years: A systematic review. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1449436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.Z.; Beckmann, J.; Lang, C.; Seelig, H.; Nqweniso, S.; Probst-Hensch, N.; et al. Impact of a school-based health intervention program on body composition among South African primary schoolchildren: Results from the KaziAfya cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espejo, J.P.; Tumani, M.F.; Aguirre, C.; Sanchez, J.; Parada, A. Educación alimentaria nutricional: Estrategias para mejorar la adherencia al plan dietoterapéutico. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2022, 49, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verjans-Janssen, S.R.B.; van de Kolk, I.; Van Kann, D.H.H.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Gerards, S.M.P.L. Effectiveness of school-based physical activity and nutrition interventions with direct parental involvement on children’s BMI and energy balance-related behaviors: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2023–2024; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE). Proyecciones y Estimaciones de Población Total País, Urbano-Rural y Regional, 2002–2035 (Base 2017); INE: Santiago, Chile, 2024; Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Universidad Diego Portales. Informe Anual sobre Derechos Humanos en Chile 2024; Centro de Derechos Humanos, Facultad de Derecho UDP: Santiago, Chile, 2024; Available online: https://derechoshumanos.udp.cl/cms/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/INFORME-ANUAL-DDHH-UDP-2024-COMPLETO.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Chile 2022; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-chile-2022_311ec37e-en.html (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile (BCN). Clima y Vegetación. Chile Nuestro País; BCN: Santiago, Chile. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/siit/nuestropais/clima.htm (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Altavilla, C.; Caballero-Pérez, P. An update of the KIDMED questionnaire, a Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2543–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, D.F.; Granfeldt, M.G.; Mosso, C.C.; Sáez, C.K.; Muñoz, R.S. Evaluación nutricional y adherencia a la dieta mediterránea de adolescentes chilenos que residen en hogares de familias hospedadoras. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2016, 43, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Auquier, P.; Erhart, M.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Bruil, J.; et al. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, G.T.; Montaño, E.R.; González, A.E.; Sepúlveda, P.R.; Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C.; Martínez, V.N.; et al. Propiedades psicométricas del cuestionario de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud KIDSCREEN-27 en adolescentes chilenos. Rev. Med. Chil. 2014, 142, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J. Psychometric validity. In The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing; Irwing, P., Booth, T., Hughes, D.J., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Hernández-Dorado, A.; Muñiz, J. Decalogue for the factor analysis of test items. Psicothema 2022, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.D.; Yu, C.C. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: Skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2015, 75, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Cerny, B.A. Factor analysis of the image correlation matrix. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1979, 39, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. Exploratory item factor analysis: A practical guide revised and updated. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, development and future directions. Psicothema 2017, 29, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang-Wallentin, F.; Jöreskog, K.G.; Luo, H. Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with misspecified models. Struct. Equ. Model. 2010, 17, 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. MSA: The forgotten index for identifying inappropriate items before computing exploratory item factor analysis. Methodology 2021, 17, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicer, W.F.; Fava, J.L. Affects of variable and subject sampling on factor pattern recovery. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Timmerman, M.E.; Kiers, H.A.L. The Hull method for selecting the number of common factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Assessing goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2005, 37, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. Available online: https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~snijders/mpr_Schermelleh.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Kalkan, Ö.K.; Kelecioğlu, H. The effect of sample size on parametric and nonparametric factor analytical methods. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2016, 16, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, R.H. A new asymmetric measure of association for ordinal variables. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, E. Guidelines to statistical evaluation of data from rating scales and questionnaires. J. Rehabil. Med. 2000, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassmann, F.; de Groot, R.; Dietrich, S.; Timar, E.; Jaccoud, F.; Giuberti, L.; et al. Determinants and drivers of young children’s diets in Latin America and the Caribbean: Findings from a regional analysis. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, G.X.; Monge-Rojas, R.; King, A.C.; Hunter, R.; Berge, J.M. The social environment and childhood obesity: Implications for research and practice in the United States and countries in Latin America. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22 (Suppl 3), e13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.C.; Lira, M.; Kain, J. Vulnerabilidad socioeconómica y obesidad en escolares chilenos de primero básico: Comparación entre los años 2009 y 2013. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2017, 88, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, D.; Reimers, A.K.; Wagner, M.O.; Woll, A. Physical activity in sports clubs of children and adolescents in Germany: Results from a nationwide representative survey. J. Public Health 2013, 21, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; López-Bueno, R.; Sillero-Quintana, M.; Pardhan, S.; Yuste Lucas, J.L.; Cavero-Redondo, I. Mediterranean diet and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa-Milian, L.; Fernández-García, J.C.; Vicente-Herrero, M.T.; Morales-Gil, I.M.; Segura-Fragoso, A.; Planelles-Ramos, M.V.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and its association with anthropometric and lifestyle factors in Spanish adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurtdaş Depboylu, A.; Arslan, S.; Arikan Durmaz, S. Factors affecting Mediterranean diet adherence in adolescents: Age, physical activity, and sleep quality. Nutrition 2023, 112, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesildemir, O.; Bayram, M.; Alarcón, J.A.; Yildiz, E.; Tur, J.A.; Turkmen, M.; et al. Socioeconomic determinants of adherence to the Mediterranean diet among children and adolescents: A multi-country study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, B.D.M.; de Souza, A.C.N.; Rodrigues, P.R.M.; Cunha, D.B.; Muraro, A.P. Adherence to school meals and co-occurrence of the healthy and unhealthy food markers among Brazilian adolescents. Cien. Saude Colet. 2023, 28, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, E.A.; Pedrozo, E.A.; Da Silva, T.N. The PNAE (National School Feeding Program) activity system and its mediations. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 981932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Toledo, S.; Canals-Sans, J.; Ballonga-Paretas, C.; Arija-Val, V. Estado nutricional de escolares peruanos según nivel socioeconómico. Proyecto INCOS. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Comunitaria 2020, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Malnutrición en Niños y Niñas en América Latina y el Caribe. CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2018. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/enfoques/malnutricion-ninos-ninas-america-latina-caribe (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. Plan Nacional de Actividad Física Escolar; MINEDUC: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Rojas, G.; Hurtado Almonacid, J.; Páez Herrera, J. Inactividad física en niñas: Percepciones de los niños, niñas y docentes sobre el programa “Crecer en Movimiento” en Chile. LATAM Rev. Lat. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 2025, 6, 2148–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, C.; Carmona, C.; Albornoz, J.; Hernández-García, R.; Torres-Luque, G. Efecto de un programa de actividades deportivas extraescolares en jóvenes chilenos. Retos 2019, 35, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, L.; Salali, G.D.; Andersen, L.B.; Hallal, P.C.; Northstone, K.; Sardinha, L.B.; et al. Gender differences in the distribution of children’s physical activity: Evidence from nine countries. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujelbane, M.A.; Ammar, A.; Salem, A.; Kerkeni, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Bouaziz, B.; et al. Gender-specific insights into adherence to Mediterranean diet and lifestyle: Analysis of 4,000 responses from the MEDIET4ALL project. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1570904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Helmer, C.K.; Wong, J.; Diep, T.; Domingue, S.K.; Do, R.; et al. Social epidemiology of early adolescent nutrition. Pediatr. Res. Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peral-Suárez, Á.; Haycraft, E.; Blyth, F.; Holley, C.E.; Pearson, N. Dietary habits across the primary-secondary school transition: A systematic review. Appetite 2024, 201, 107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afe, J.E.; Ubajaka, C.F.; Okoye, A.C. Nutritional status of adolescents in public and private secondary schools in Asaba, Delta State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2023, 15, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, F.E.; Alpat Yavaş, İ.; Saleki, N.; Bakırhan, H.; Pehlivan, M. Diet quality and snack preferences of Turkish adolescents in private and public schools. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1365355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.; Hecht, A.A.; McLoughlin, G.M.; Turner, L.; Schwartz, M.B. Universal school meals and associations with student participation, attendance, academic performance, diet quality, food security, and body mass index: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, T.M.; Mackenzie, E.; Siette, J. “Establishing healthy habits and lifestyles early is very important”: Parental views of brain health literacy on dementia prevention in preschool and primary school children. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1401806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csima, M.; Podráczky, J.; Keresztes, V.; Soós, E.; Fináncz, J. The role of parental health literacy in establishing health-promoting habits in early childhood. Children 2024, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Buhr, E.; Tannen, A. Parental health literacy and health knowledge, behaviours and outcomes in children: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniyagundi Podiya, J.; Navaneetham, J.; Bhola, P. Influences of school climate on emotional health and academic achievement of school-going adolescents in India: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstad Aasan, B.E.; Lillefjell, M.; Krokstad, S.; Sylte, M.; Sund, E.R. The relative importance of family, school, and leisure activities for the mental wellbeing of adolescents: The Young-HUNT study in Norway. Societies 2023, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.; Al Nuaimi, A.; Guang, Y.; Al Sheryani, Y.; Al Rashedi, A. The effects of home and school on children’s happiness: A structural equation model. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2018, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514187 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Karpouzis, F.; Anastasiou, K.; Lindberg, R.; Walsh, A.; Shah, S.; Ball, K. Effectiveness of school-based nutrition education programs that include environmental sustainability components, on fruit and vegetable consumption of 5–12 year old children: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2025, 57, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Medeiros, G.C.B.; de Azevedo, K.P.M.; Garcia, D.; Segundo, V.H.O.; de Sousa Mata, A.N.; Fernandes, A.K.P.; et al. Effect of school-based food and nutrition education interventions on the food consumption of adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Shinde, S.; Young, T.; Fawzi, W.W. Impacts of school feeding on educational and health outcomes of school-age children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 04051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Cronbach’s alpha | Level | MIF | χ2/df | RMSEA | AGFI | GFI | CFI | NNFI | RMSR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥200 | ≥0.70 ≤0.90 |

Good fit | NR | ≥0 | ≤0.05 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.95 | ≥0.97 | ≥0.97 | <0.05 ++ |

| ≤2 | ≤1.00 | ≤1.00 | ≤1.00 | ≤1.00 | ||||||

| Acceptable fit | ≥3 | >2 | >0.05 | ≥0.85 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.95 | ≥0.95 | ≥0.05 | ||

| ≤3 | ≤0.08 | <0.90 | <0.95 | <0.97 | <0.97 | ≤0.08 ++ |

| Sociodemographic variables | Level | N | n% |

| Sex | Women | 170 | 48% |

| Men | 186 | 52% | |

| Age (years old) | 7 | 1 | 0% |

| 8 | 22 | 6% | |

| 9 | 87 | 24% | |

| 10 | 118 | 33% | |

| 11 | 99 | 28% | |

| 12 | 25 | 7% | |

| 13 | 1 | 0% | |

| 14 | 3 | 1% | |

| Grade | 3° | 60 | 17% |

| 4° | 126 | 35% | |

| 5° | 123 | 35% | |

| 6° | 47 | 13% | |

| Living Area | Urban | 294 | 83% |

| Rural | 62 | 17% | |

| Kind of school | Municipal | 134 | 38% |

| Subsidized | 78 | 22% | |

| Private | 144 | 40% |

| Variables | N | Mean | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| PAH1 * | 356 | 3.70 | 1.119 * | -0.475 * | 0.129 | -0.383 * | 0.258 |

| PAH2 * | 356 | 3.56 | 1.542 * | -0.362 * | 0.129 | -1.063 * | 0.258 |

| PAH3 * | 356 | 3.79 | 1.506 * | -0.701 * | 0.129 | -0.592 * | 0.258 |

| PAH4 * | 356 | 3.85 | 1.528 * | -0.756 * | 0.129 | -0.546 * | 0.258 |

| PAH5 * | 356 | 3.74 | 1.320 * | -0.563 * | 0.129 | -0.586 * | 0.258 |

| MAF1 * | 356 | 4.03 | 1.529 * | -1.039 * | 0.129 | -0.155 * | 0.258 |

| MAF2 * | 356 | 3.72 | 1.135 * | -0.683 * | 0.129 | 0.032 * | 0.258 |

| MAF3 * | 356 | 4.01 | 1.223 * | -1.017 * | 0.129 | 0.266 * | 0.258 |

| MAF4 * | 356 | 3.18 | 1.590 * | -0.190 * | 0.129 | -0.892 * | 0.258 |

| MAF5 * | 356 | 3.46 | 1.759 * | -0.398 * | 0.129 | -0.936 * | 0.258 |

| MAF6 * | 356 | 3.53 | 1.771 * | -0.456 * | 0.129 | -0.921 * | 0.258 |

| MAF7 * | 356 | 3.85 | 1.714 * | -0.902 * | 0.129 | -0.368 * | 0.258 |

| FLT1 * | 356 | 3.70 | 1.511 * | -0.643 * | 0.129 | -0.534 * | 0.258 |

| FLT2 * | 356 | 3.65 | 1.536 * | -0.496 * | 0.129 | -0.882 * | 0.258 |

| FLT3 * | 356 | 3.84 | 1.367 * | -0.733 * | 0.129 | -0.385 * | 0.258 |

| FLT4 * | 356 | 4.16 | 1.346 * | -1.317 * | 0.129 | 0.754 * | 0.258 |

| FLT5 * | 356 | 4.12 | 1.346 * | -1.195 * | 0.129 | 0.453 * | 0.258 |

| FLT6 * | 356 | 3.25 | 1.940 * | -0.240 * | 0.129 | -1.174 * | 0.258 |

| FLT7 * | 356 | 3.42 | 2.014 * | -0.375 * | 0.129 | -1.172 * | 0.258 |

| TWF1 * | 356 | 4.10 | 1.242 * | -1.222 * | 0.129 | 0.766 * | 0.258 |

| TWF2 * | 356 | 4.25 | 1.101 * | -1.368 * | 0.129 | 1.133 * | 0.258 |

| TWF3 * | 356 | 4.03 | 1.250 * | -1.004 * | 0.129 | 0.220 * | 0.258 |

| TWF4 * | 356 | 3.88 | 1.433 * | -0.831 * | 0.129 | -0.241 * | 0.258 |

| SCL1 * | 356 | 3.81 | 1.364 * | -0.663 * | 0.129 | -0.618 * | 0.258 |

| SCL2 * | 356 | 3.80 | 1.054 * | -0.541 * | 0.129 | -0.380 * | 0.258 |

| SCL3 * | 356 | 3.98 | 0.943 * | -0.777 * | 0.129 | -0.004 * | 0.258 |

| SCL4 * | 356 | 4.21 | 1.046 * | -1.227 * | 0.129 | 0.699 * | 0.258 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 356 | ||||||

| KMO and Bartlett’s Test | |||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0.875 | ||||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 2387.848 | |||

| Degree of freedom | 190 | ||||

| Significance | 0.000 | ||||

| Pattern Matrix a | |||||

| ID | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 |

| PAH1 | 0.451 | ||||

| PAH2 | 0.547 | ||||

| PAH3 | 0.639 | ||||

| PAH4 | 0.512 | ||||

| PAH5 | 0.518 | ||||

| MAF4 | 0.814 | ||||

| MAF5 | 0.748 | ||||

| MAF6 | 0.647 | ||||

| FLT3 | 0.425 | ||||

| FLT5 | 0.413 | ||||

| FLT6 | 0.671 | ||||

| FLT7 | 0.670 | ||||

| TWF1 | 0.675 | ||||

| TWF2 | 0.756 | ||||

| TWF3 | 0.635 | ||||

| TWF4 | 0.654 | ||||

| SCL1 | 0.431 | ||||

| SCL2 | -0.579 | ||||

| SCL3 | -0.724 | ||||

| SCL4 | -0.552 | ||||

| Eigenvalue | 5.683 | 1.178 | 1.049 | 0.775 | 0.725 |

| % of Variance | 28.413 | 5.891 | 5.243 | 3.874 | 3.625 |

| Cumulative % | 28.413 | 34.303 | 39.547 | 43.421 | 47.046 |

| Factor Correlation Matrix b | |||||

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 1.000 | 0.370 | 0.341 | 0.426 | -0.421 |

| 2 | 0.370 | 1.000 | 0.367 | 0.261 | -0.329 |

| 3 | 0.341 | 0.367 | 1.000 | 0.349 | -0.398 |

| 4 | 0.426 | 0.261 | 0.349 | 1.000 | -0.354 |

| 5 | -0.421 | -0.329 | -0.398 | -0.354 | 1.000 |

| KMO and Bartlett’s Test | ||||||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. (confidence interval 90%) | 0.875 (0.791; 0.862) | |||||||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 3226.8 | ||||||

| Degree of freedom | 190 | |||||||

| Significance | 0.000010 | |||||||

| Rotated Loading Matrix | ||||||||

| Variable (Item) | Factor 1 (F1) | Factor 2 (F2) | Factor 3 (F3) | Factor 4 (F4) | Factor 5 (F5) | |||

| Factor Name | ||||||||

| PAH1 | 0.487 | |||||||

| PAH2 | 0.570 | |||||||

| PAH3 | 0.680 | |||||||

| PAH4 | 0.568 | |||||||

| PAH5 | 0.561 | |||||||

| MAF4 | 0.859 | |||||||

| MAF5 | 0.782 | |||||||

| MAF6 | 0.696 | |||||||

| FLT3 | 0.478 | |||||||

| FLT5 | 0.494 | |||||||

| FLT6 | 0.690 | |||||||

| FLT7 | 0.705 | |||||||

| TWF1 | 0.702 | |||||||

| TWF2 | 0.777 | |||||||

| TWF3 | 0.657 | |||||||

| TWF4 | 0.707 | |||||||

| SCL1 | 0.437 | |||||||

| SCL2 | 0.608 | |||||||

| SCL3 | 0.764 | |||||||

| SCL4 | 0.638 | |||||||

| Explained Variance | 0.359 | 0.085 | 0.082 | 0.066 | 0.063 | |||

| Cumulative Variance | 0.359 | 0.443 | 0.523 | 0.591 | 0.654 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 7.169 | 1.689 | 1.637 | 1318 | 1.260 | |||

| % Eigenvalue | 54.838% | 12.920% | 12.522% | 10.082% | 9.638% | |||

| Inter Factor Correlation Matrix | ||||||||

| Factor | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |||

| F1 | 1.000 | |||||||

| F2 | 0.427 | 1.000 | ||||||

| F3 | 0.430 | 0.366 | 1.000 | |||||

| F4 | 0.356 | 0.435 | 0.361 | 1.000 | ||||

| F5 | 0.382 | 0.344 | 0.262 | 0.379 | 1.000 | |||

| Article | Country | Sample | Method | Factors | MIF | χ2/df | RMSEA | AGFI | GFI | CFI | NNFI | RMSR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Model | Chile | 356 | EFA/CFA | 5 | 3 | 1.15 **,+ | 0.021 ** | 0.989 ** | 0.994 ** | 0.998 ** | 0.996 ** | 0.031 ** |

| Schermelleh-Engel et al. [44] | Parameters | ≥200 | Good fit |

- | NR | ≥0 ≤2 |

≤0.05 | ≥0.90 ≤1.00 |

≥0.95 ≤1.00 |

≥0.97 ≤1.00 |

≥0.97 ≤1.00 |

<0.05 ++ |

| Acceptable fit | - | ≥3 | >2 3 |

>0.05 ≤0.08 |

≥0.85 <0.90 |

≥0.90 <0.95 |

≥0.95 <0.97 |

≥0.95 <0.97 |

≥0.05 ≤0.08 ++ |

| Scale | Valid cases | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 356 | 5 | 0.836** |

| Factor 2 | 356 | 3 | 0.725* |

| Factor 3 | 356 | 4 | 0.731* |

| Factor 4 | 356 | 5 | 0.713* |

| Factor 5 | 356 | 3 | 0.781* |

| KIDSCREEN-20 | 356 | 20 | 0.876** |

| Cross-Table | Test | Value | Asymptotic Standardized Error a | Approximate T b | Approximate Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIDSCREEN-20 * SEX | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.128 | 0.056 | 2.266 | 0,023 * |

| Gamma | 0.192 | 0.084 | 2.266 | 0,023 * | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KIDSCREEN-20 * AGE | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | -0.034 | 0.041 | -0.832 | 0,405 |

| Gamma | -0.052 | 0.063 | -0.832 | 0,405 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KIDSCREEN-20 * GRD | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | -0.012 | 0.038 | -0.307 | 0,759 |

| Gamma | -0.019 | 0.061 | -0.307 | 0,759 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KIDSCREEN-20 * LIA | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.000 | 0.042 | -0.003 | 0,998 |

| Gamma | 0.000 | 0.112 | -0.003 | 0,998 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KIDSCREEN-20 * KOS | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.010 | 0.044 | 0.226 | 0,822 |

| Gamma | 0.015 | 0.068 | 0.226 | 0,822 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KML * SEX | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.016 | 0.054 | 0.297 | 0,766 |

| Gamma | 0.029 | 0.099 | 0.297 | 0,766 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KML * AGE | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.031 | 0.046 | 0.691 | 0,489 |

| Gamma | 0.051 | 0.074 | 0.691 | 0,489 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KML * GRD | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.022 | 0.047 | 0.482 | 0,630 |

| Gamma | 0.038 | 0.079 | 0.482 | 0,630 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KML * LIA | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.076 | 0.040 | 1.910 | 0,056 |

| Gamma | 0.246 | 0.128 | 1.910 | 0,056 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KML * KOS | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | 0.039 | 0.045 | 0.882 | 0,378 |

| Gamma | 0.074 | 0.083 | 0.882 | 0,378 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| KIDSCREEN-20 * KML | Ordinal per ordinal | Kendall’s Tau-C | -0.002 | 0.043 | -0.039 | 0,969 |

| Gamma | -0.003 | 0.078 | -0.039 | 0,969 | ||

| N of valid cases | 356 | |||||

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | N of valid cases | Expected counts less than 5 (%). | Test validity |

Value | df | Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIDSCREEN-20 | SEX | 356 | 0.0% * | Yes | 7.402 | 3 | 0.060 |

| KML | LIA | 356 | 16.7% * | Yes | 3.442 | 2 | 0.179 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).