1. Introduction

There is a consensus in the scientific community on the definition of Physical Literacy (PL), which is described as the physical ability, motivation, confidence, knowledge and willingness to participate in physically active lifestyles, encompassing four domains: physical, psychological, social and cognitive [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It has been noted that the development of movement and sports skills encourages the adoption of more active and healthy behaviors, allowing a physically literate child to perform with ease and confidence in a variety of physically challenging situations, being able to react appropriately to a wide range of scenarios [

1,

3,

6,

7]. In contrast, those children who do not reach an adequate level of PL tend to avoid physical activity situations due to lack of confidence and motivation [

8].

The PL construct can be addressed in both educational and extracurricular settings. Castelli and Centeio [

9] highlight that, within the educational context, curricula can support the development of PL in various ways, such as by distinguishing between structured, unstructured or informal physical activities (such as recess), and through the teaching of physical activities enriched with academic content that integrates theoretical concepts and movement learning.

Consequently, multiple investigations have explored the role of PL both in physical education classes [

10,

11,

12] and in activities performed outside school hours [

13,

14,

15]. The growing interest in PL and the benefits associated with its strengthening have prompted the development of assessment methods that facilitate its monitoring and control. An example of this is the Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy (CAPL) [

16], one of the first tools created for this purpose, which began to be developed in 2009 in response to the need to obtain objective data on PL. This tool was designed to be valid, reliable, feasible, and informative, with the purpose of assessing PL in Canadian children, covering several domains, such as fundamental motor skills, physical activity behavior, physical fitness, and knowledge, as well as awareness and understanding.

Not only does PL generate and encourage greater participation in physical activity and greater adherence to a healthy lifestyle, but it also has a significant impact on the overall health of individuals [

17]. An adequate level of PL is associated with a reduction in the prevalence of childhood obesity, because it promotes active behaviors and lifestyle, along with greater awareness and knowledge about the importance of performing and integrating the practice of regular physical activity into daily life [

18,

19]. The latter being particularly relevant, since childhood obesity is a significant risk factor for the development of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes [

20].

PL contributes to the development of basic motor skills, which are fundamental during childhood, as these skills form the basis for participation in a wide range of physical activities throughout life [

21]. A study by Huang et al. [

22] indicated that children with a higher level of PL showed an improvement in basic motor skills, which in turn correlated with a higher rate of participation in physical activities and better overall physical fitness.

From a health perspective, higher levels of PL are also related to improvements in cardiovascular and metabolic health. Recent research suggests that physically literate children are at lower risk of developing cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia, due to their higher level of regular physical activity [

23,

24].

Finally, PL also has a positive impact on children's mental health and psychological well-being, improving self-esteem and reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression, which contributes to an overall health status [

25,

26].

Due to the relevance of studying the development of PL, this study proposes as objectives (1) to establish the levels of PL in basic (primary) education children in Santiago, Chile, (2) to explore the relationship between PL and BMI in this Chilean population, and (3) to analyze the possible differences in PL levels according to the different BMI categories.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve our research objectives, we used the CAPL-2 questionary in Spanish [

27] and the BMI parameters (height and body weight). The surveyed population corresponds to 439 students from 5th to 8th grade of primary education from 4 educational establishments in the Santiago Sur sector (Chile), whose characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

The results have been obtained from the CAPL-2 questionnaire [

27] complementing for the results in older students according to the study of Blanchard et al. [

28], in relation to the level of motivation (MOTLEV) with physical activity and the level of knowledge (KNOLEV) about physical activity using SPSS software version 23 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) have been contrasted with the demographic variables (Sex, Nutritional category, and Age), by means of a nonparametric statistical analysis of chi-squared test determining the degree of dependence between two variables by p-value, whose acceptable significance is <0.050 and good is <0.010 [

29,

30].

3. Results

The results correlated the demographic variables: gender, nutritional category (NUTCAT), and age, with the motivation level (MOTLEV) for physical activity and the knowledge level (KNOLEV) about physical activity (see

Table 2).

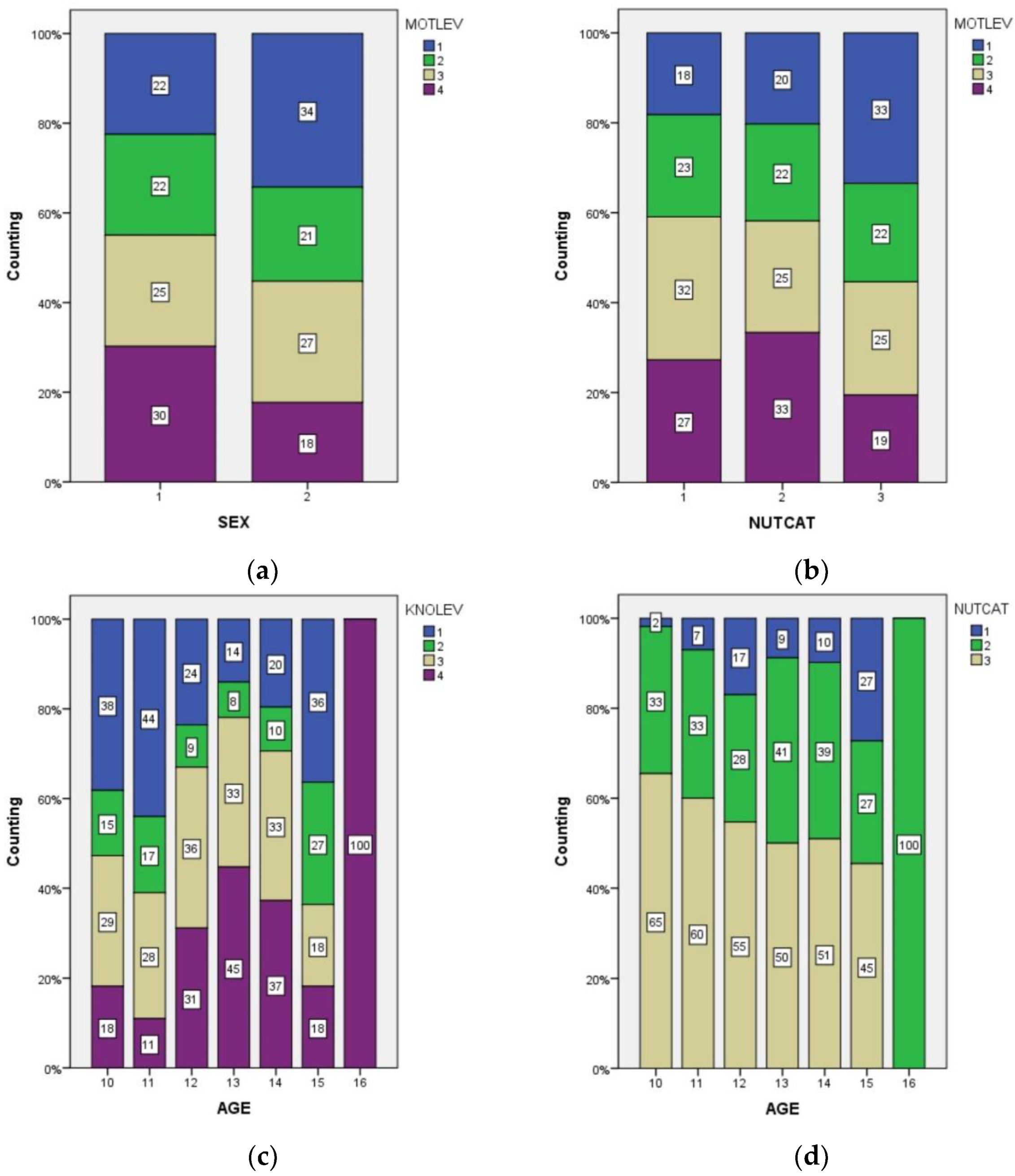

Therefore, in this case, motivation level correlates well with gender and acceptably with nutritional category, and knowledge level correlates well with age. Additionally, nutritional category correlates acceptably with age (p-value = 0.032). All significant correlations can be seen in

Figure 1.

Figure 1a shows the gender differences, to the detriment of the female gender, in the motivation to participate in physical activities, where boys present higher levels of motivation to engage in physical activity compared to girls.

Figure 1b reveals that as nutritional category increases, motivation to engage in physical activity decreases, especially in students with higher BMI. Similarly,

Figure 1c illustrates how the level of knowledge about physical activity increases with age, reflecting greater knowledge in students with higher age, i.e., upper grades. In relation to the nutritional category,

Figure 1d indicates that being overweight is more prevalent as age increases, with an increase in the proportion of overweight children in the older age groups.

4. Discussion

The results of our study show different interesting dynamics in the relationship between physical literacy, BMI, and sociodemographic factors such as age and sex in children and adolescents who participated in the study. These findings are explored in detail below, organized into key points.

4.1. Relationship between Age and BMI

We observe that as children grow older, their BMI tends to increase. The global trend for childhood obesity continues to rise [

31]. This finding could be related to changes in lifestyle as age increases, which could be determined by the increase in caloric foods during adolescence [

32] and the decrease in physical activity during this same age, because children and adolescents decrease their rate of physical activity as they increase in age, due to commitments related to increased academic difficulty along with increased screen time [

33].

Particularly in Chile, the trend is towards increasing obesity, identifying in the 2016-2017 National Health Survey that almost 44% of children between 5 and 17 years old were overweight or obese [

34], a situation that is emphasized by “Chile's 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents” [

35], again highlighting that Chilean children and adolescents decrease their rate of physical activity as they increase in age, supporting the increasing trend of BMI as age increases in the pediatric population.

4.2. Motivation and Sex

Motivation to participate in physical activity, on the other hand, is inversely related to sex, with the majority of boys increasing or maintaining their motivation to engage in physical activity as they get older, unlike their female counterparts in whom the trend was not evident. In this sense, and in view of the results, the need for specific interventions to address gender differences in motivation for physical activity, especially in girls and adolescents, is suggested [

36]. In this regard, Jekauc et al. [

37] found that gender differences in motivation for physical activity widen with age, with boys maintaining higher levels of motivation than girls throughout adolescence. At the same time, the 2018 National Survey of Physical Activity and Sports in Chile supports this observation, concluding that men tend to participate more in physical activities than women, especially during adolescence, which could suggest the presence of cultural and social barriers that could undermine women's motivation to engage in physical activity [

38].

4.3. Knowledge and Age

Levels of knowledge about physical activity increase with age and is independent of sex. This increase may be related to time of exposure to the educational environment, where the benefits of physical activity are promoted [

39]. This finding aligns with the conceptualization of physical literacy as a progressive journey across the lifespan, where knowledge accumulates over time and experience [

40]. Both The National Health Survey 2016-2017 [

34] and “Chile's 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents” [

35] have reported an increasing awareness of the importance of physical activity in Chile, however, this knowledge does not always translate into healthy practices, supporting our observation that knowledge does not directly influence the nutritional category. In this sense, Bailey et al [

41], highlight that, although knowledge is an essential component of physical literacy, its impact on healthy behavior is mediated by motivation and the social environment

4.4. Relationship between Motivation and Nutritional Status

The inverse relationship found between motivation for physical activity and BMI suggests that more motivated children tend to have a BMI closer to that expected for their age and height. This finding underscores the importance of motivation as a key factor in promoting a healthy weight and lifestyle, highlighting the need to foster a culture that motivates children and adolescents to be active [

42]. Owen et al. [

43] found that intrinsic motivation to engage in physical activity is associated with greater adherence to a healthy lifestyle and, therefore, a lower incidence of obesity and overweight in adolescents.

4.5. Knowledge and Nutritional Status

Interestingly, we did not find a significant relationship between knowledge level and nutritional category. This suggests that, although knowledge about the benefits of regular physical activity is important, it is not sufficient by itself to influence behaviors that affect BMI [

44]. Likewise, it supports the idea that, although knowledge about physical activity is included within the concept of physical literacy, its influence on health will also depend on motivational and behavioral factors that need to be addressed in a comprehensive manner [

45]. Along these lines, the suggestion is that physical activity and healthy lifestyle education should be accompanied by motivational strategies that foster a supportive environment to ensure the effectiveness of interventions [

46,

47].

Likewise, improvement in physical literacy levels also requires improvements in nutritional labeling [

48] so that children and adolescents can make informed decisions about their own nutrition. Muñoz et al. [

49] in their study on the influence of body composition on physical literacy in Spanish children highlights that a higher percentage of fat mass is associated with lower levels of physical competence, which in turn could be linked to increased consumption of junk food and energy drinks as children get older [

32,

48].

4.6. Implications for Public Health

The results of our study, together with data from national surveys, underscore the importance of public health policies that address both education and motivation for physical activity, that is, physical literacy as a whole [

50]. For their part, the results of the 2016-2017 National Health Survey and Chile's 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents highlight the urgent need to intervene early in life to reverse the increasing trends of overweight and obesity, which reinforces the relevance of our findings in the Chilean context [

34,

35], so interventions should be specific for each age group and sex, considering the particular barriers and motivations of each subgroup to maximize their effectiveness [

51,

52].

5. Conclusions

The findings of our study confirm the national trend of increasing BMI with age in Chilean children and adolescents. Motivation to engage in physical activity shows an inverse relationship with BMI, with males being more motivated than females. This suggests the need to develop specific interventions that consider gender differences. On the other hand, although knowledge about the benefits of physical activity and an active lifestyle increases with age, it does not have a significant influence on its own on nutritional status. This indicates that knowledge, without the backing of motivation and social support, is not sufficient to generate sustainable changes in behavior. Our findings underscore the importance of designing programs and public policies that promote physical literacy, specifically tailored to the characteristics of each age and gender group, to improve pediatric health in Chile. Motivation to engage in physical activity emerges as a key factor for the success of these interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: PLBM.csv.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.-U. and A.V.-M.; methodology, A.V.-M.; validation, N.C.-B., and G.S.-S.; formal analysis, N.M.-U., A.V.-M., N.C.-B., and G.S.-S.; investigation, W.U.-P., N.M.-U. and A.V.-M.; resources, M.M.-M.; data curation, N.M.-U., A.V.-M., and G.S.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.-U., and G.S.S.; writing—review and editing, N.M.-U., R.C.-S., and A.V.-M.; visualization, R.C.-S., and A.V.-M.; supervision, M.M.-M.; project administration, A.V.-M..; funding acquisition, R.C.-S., A.V.-M., N.C.-B., and G.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Article Processing Charge (APC) was partially funded by Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Code: APC2024). Additionally, the publication fee (APC) was partially financed through the Publication Incentive Fund, 2024, by the Universidad Central de Chile (Code: APC2024), Universidad Arturo Prat (Code: APC2024), Universidad de Las Americas (Code: APC2024), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (Code: APC2024), and Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana (Code: APC2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics and Biosafety Committee of Universidad de Extremadura (Register Number 152/2022, 28 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- De Balazs, A.C.R.; de D’Amico, R.L.; Cedeño, J.J.M. Alfabetización física: una percepción reflexiva. Dialógica Rev. Multidiscip. 2017, 14, 87–102. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6216222 (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Whitehead, M. Definition of physical literacy and clarification of related issues. ICSSPE Bull. J. Sport Sci. Phys. Educ. 2013, 65, 72–79. Available online: https://www.icsspe.org/sites/default/files/bulletin65_0.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Whitehead, M. Physical Literacy: Throughout the Lifecourse; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/books/mono/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9780203881903&type=googlepdf (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Durden-Myers, E.J. Advancing physical literacy research in children. Children 2024, 11, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkovic Vuletic, P.; Gilic, B.; Zenic, N.; Pavlinovic, V.; Kesic, M.G.; Idrizovic, K.; et al. Analyzing the associations between facets of physical literacy, physical fitness, and physical activity levels: Gender- and age-specific cross-sectional study in preadolescent children. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano-Mairena, J.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Rodal, M.; et al. Role of satisfaction with life, sex and body mass index in physical literacy of Spanish children. Children 2024, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Tang, X.; Qiao, J.; Wang, H. Unlocking resilience: How physical literacy impacts psychological well-being among quarantined researchers. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Longmuir, P.E.; Barnes, J.D.; Belanger, K.; Anderson, K.D.; Bruner, B.; et al. Physical literacy levels of Canadian children aged 8–12 years: Descriptive and normative results from the RBC Learn to Play–CAPL project. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, D.M.; Centeio, E.E.; Beighle, A.E.; Carson, R.L.; Nicksic, H.M. Physical literacy and comprehensive school physical activity programs. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, P.; Vandenborn, E.; Santarossa, S.; Milne, M.M.; Milne, K.J.; Woodruff, S. Physical literacy improves with the Run Jump Throw Wheel program among students in grades 4–6 in southwestern Ontario. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriellaars, D.J.; Cairney, J.; Bortoleto, M.A.; Kiez, T.K.; Dudley, D.; Aubertin, P. The impact of circus arts instruction in physical education on the physical literacy of children in grades 4 and 5. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2019, 38, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilic, B.; Sunda, M.; Versic, S.; Modric, T.; Olujic, D.; Sekulic, D. Effectiveness of physical-literacy-based online education on indices of physical fitness in high-school adolescents: Intervention study during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Children 2023, 10, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremer, E.; Graham, J.D.; Cairney, J. Outcomes and feasibility of a 12-week physical literacy intervention for children in an afterschool program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandigo, J.; Lodewyk, K.; Tredway, J. Examining the impact of a teaching games for understanding approach on the development of physical literacy using the Passport for Life assessment tool. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2019, 38, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, M.; Pelletier, R.; Labbé, M.; Best, K.L.; Robert, M.T. Exploring knowledge of the concept of physical literacy among rehabilitation professionals, students and coaches practicing in a pediatric setting. Disabilities 2023, 3, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longmuir, P.E.; Boyer, C.; Lloyd, M.; Yang, Y.; Boiarskaia, E.; Zhu, W, et al. The Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy: Methods for children in grades 4 to 6 (8 to 12 years). BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, H.A.T.; Di Cristofaro, N.A.; Cairney, J.; Bray, S.R.; MacDonald, M.J.; Timmons, B.W. Physical literacy, physical activity, and health indicators in school-age children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Eather, N.; Weaver, R.G.; Riley, N.; Beets, M.W.; Lubans, D.R. Behavioral correlates of muscular fitness in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkinson, G.R.; Lang, J.J.; Tremblay, M.S. Temporal trends in the cardiorespiratory fitness of children and adolescents representing 19 high-income and upper-middle-income countries between 1981 and 2014. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goran, M.I.; Dumke, K.; Bouret, S.G.; Kayser, B.; Walker, R.W.; Blumberg, B. The obesogenic effect of high fructose exposure during early development. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.E.; Stodden, D.F.; Barnett, L.M.; Lopes, V.P.; Logan, S.W.; Rodrigues, L.P.; et al. Motor competence and its effect on positive developmental trajectories of health. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ö.; Aydoğdu, O.; Yıkılmaz, S.K.; Feyzioğlu, Ö.; Pişirici, P. Physical literacy as a determinant of physical activity level among late adolescents. PLoS ONE 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenmann, J.C. Aerobic fitness, fatness and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Barreira, T.V.; Broyles, S.T.; Chaput, J.P.; Fogelholm, M.; Hu, G.; et al. Physical activity, sedentary time, and obesity in an international sample of children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 2062–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Silva, E.S.; et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; et al. Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Barrios-Fernández, S.; Rojo-Ramos, J.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M. Spanish Translation and Cultural Adaptation of the Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy-2 (CAPL-2) Questionnaires. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, J.; Van Wyk, N.; Ertel, E.; Alpous, A.; Longmuir, P.E. Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy in grades 7-9 (12-16 years): Preliminary validity and descriptive results. J. Sport. Sci. 2019, 38, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Suárez, N. Estadística en la Toma de Decisiones: El p-valor. Telos 2012, 14, 439–446. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/993/99324907004.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Molina-Arias, M. What is the real significance of p-value? Rev. Pediatr. Aten. Primaria 2017, 19, 377–381. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S1139-76322017000500014&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z.A.; Hamid, Z.A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.M.; Craig, C.L.; Gauvin, L.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Tracking of obesity and physical activity from childhood to adulthood: The Physical Activity Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2009, 4, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Kho, M.E.; Saunders, T.J.; Larouche, R.; Colley, R.C.; et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile. Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2016-2017. Santiago: MINSAL; 2017. Available in: https://www.minsal.cl/encuesta-nacional-de-salud-2016-2017/. (Accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Aguilar-Farias, N.; Miranda-Marquez, S.; Toledo-Vargas, M.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Ibarra-Mora, J.; Martino-Fuentealba, P.; et al. Results from Chile’s 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2024, 22, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Timperio, A.; Crawford, D.; Salmon, J. What factors are associated with adolescents’ school break time physical activity and sedentary time? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jekauc, D.; Reimers, A.K.; Wagner, M.O.; Woll, A. Physical activity in sports clubs of children and adolescents in Germany: results from a nationwide representative survey. J. Public Health 2013, 21, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Deportes de Chile. Encuesta Nacional de Actividad Física y Deportes 2018. Santiago: IND; 2018. Available online https://www.ind.cl/encuesta-nacional-de-actividad-fisica-y-deportes/. (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Trudeau, F.; Shephard, R.J. Physical education, school physical activity, school sports and academic performance. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, S. Physical literacy in the field of physical education – A challenge and a possibility. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.; Hillman, C.; Arent, S.; Petitpas, A. Physical activity: an underestimated investment in human capital? J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.B.; Smith, J.; Lubans, D.R.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determined motivation and physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimm, S.Y.S.; Glynn, N.W.; Kriska, A.M.; Barton, B.A.; Kronsberg, S.S.; Daniels, S.R.; et al. Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennis, C.D. On their own: preparing students for a lifetime. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2010, 81, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Rosenkranz, R.R.; Peralta, L.R.; Bennie, A.; Fahey, P.; Lubans, D.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in school physical education lessons. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, J.; Booth, M.L.; Phongsavan, P.; Murphy, N.; Timperio, A. Promoting physical activity participation among children and adolescents. Epidemiol. Rev. 2007, 29, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Urtubia, N.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Estrada-Muñoz, C.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Castillo, D. Healthy behavior and sports drinks: a systematic review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Barrios-Fernández, S.; Adsuar, J.C.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Risco-Gil, M.; García-Gordillo, M.Á.; et al. Influence of body composition on physical literacy in Spanish children. Biology 2021, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.P.; Dengel, D.R.; Lubans, D.R. Supporting public health priorities: recommendations for physical education and physical activity promotion in schools. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: WHO, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).