Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology, Prevalence and Demographic Trends of HPV Related HNCs

| Clinical and Clinicopathological Features | HPV Positive HNSCC | HPV Negative HNSCC |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Younger and older patients (typically younger) | Older patients (median 61 years) |

| Sex | Male > Female (4:1) | Male > Female (3:1) |

| Anatomic Location | Oropharynx (tonsil, base of tongue, soft palate); rarely nasopharynx | Oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx |

| Risk Factors | HPV, higher number of oral sex partners, low tobacco and alcohol use, marijuana | Tobacco, alcohol |

| Exposures | Increased number of sexual partners and frequency of oral sex | Smoking, smokeless tobacco (e.g., chewing tobacco), alcohol |

| Presenting Signs and Symptoms | Asymptomatic neck masses; typically lack symptoms like odynophagia or otalgia | Dysphagia, hoarseness, odynophagia, otalgia, neck pain, weight loss |

| Primary Tumor and Lymph Node Involvement | Smaller primary tumors, but high risk of advanced cervical lymphadenopathy | Larger primary tumors, widespread cervical lymphadenopathy |

| Distant Organ Metastasis | Unusual sites: skin, brain | Lung |

| Histopathological Features | Non-keratinizing or basaloid | Keratinizing |

| Tumor Differentiation | Undifferentiated | Differentiated |

| Sensitivity to Chemoradiotherapy | Better response | Worse response |

| Prognosis (Survival) | Better prognosis | Worse prognosis |

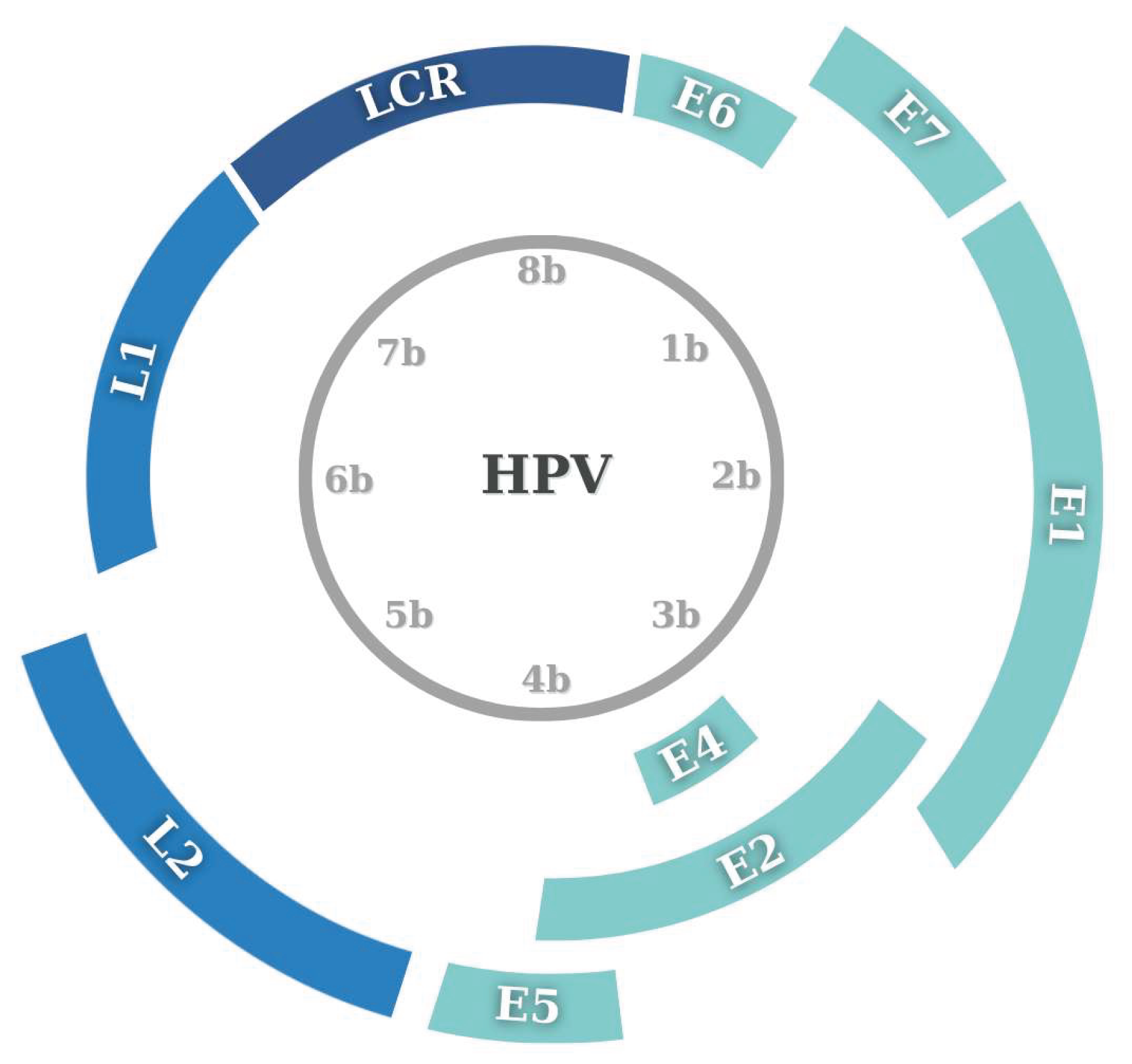

3. Virology and Mechanism of HPV in HNCs

3.1. Oncogenic Mechanism of HPV

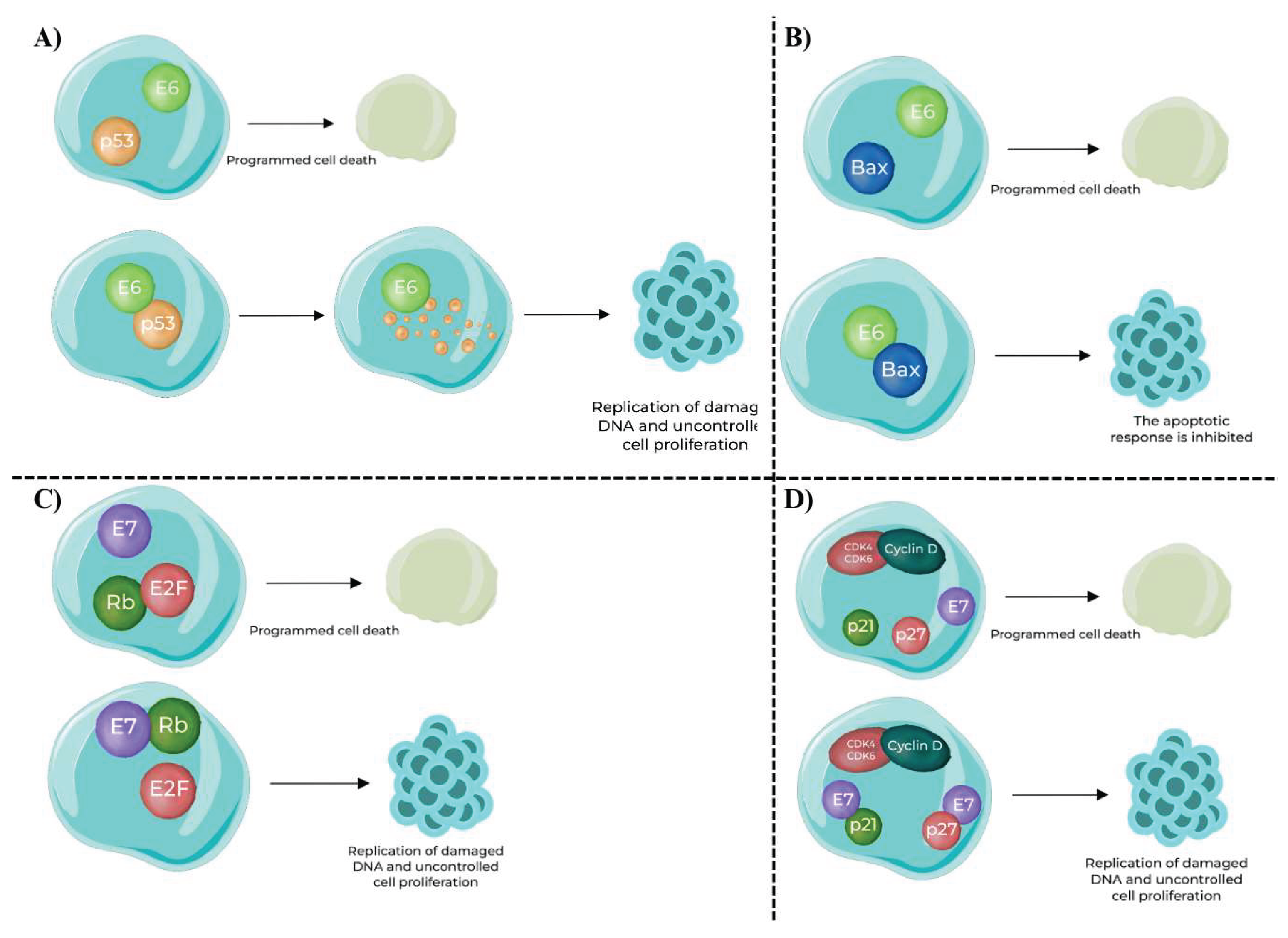

- Interaction with p53 (Figure 2.A): E6 binds to the p53 tumor suppressor protein, a critical regulator of the cell cycle and apoptosis. The binding of E6 to p53 leads to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, thus eliminating its growth-inhibitory effects.

- Impact on Apoptosis (Figure 2.B): E6 also facilitates the degradation of Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein that promotes apoptosis. By targeting Bax for degradation, E6 inhibits the apoptotic response, allowing cells with damaged DNA to survive and proliferate.

- Interaction with Rb Protein (Figure 2.C): E7 binds to pRb, another pivotal tumor suppressor. Rb normally functions by sequestering the E2F transcription factor, thereby preventing it from activating genes required for cell cycle progression. E7’s binding to Rb releases E2F, which then promotes the transcription of genes necessary for cell cycle progression, such as those involved in DNA replication and mitosis.

- Inactivation of Cyclin – Dependent Kinase (CDK) Inhibitors (Figure 2.D): E7 also inhibits CDK inhibitors like p21 and p27. Normally, these inhibitors prevent the activation of cyclin D and CDK4, which are critical for progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. By inhibiting these inhibitors, E7 promotes the activation of cyclin D and CDK4, further facilitating cell cycle progression and malignancy.

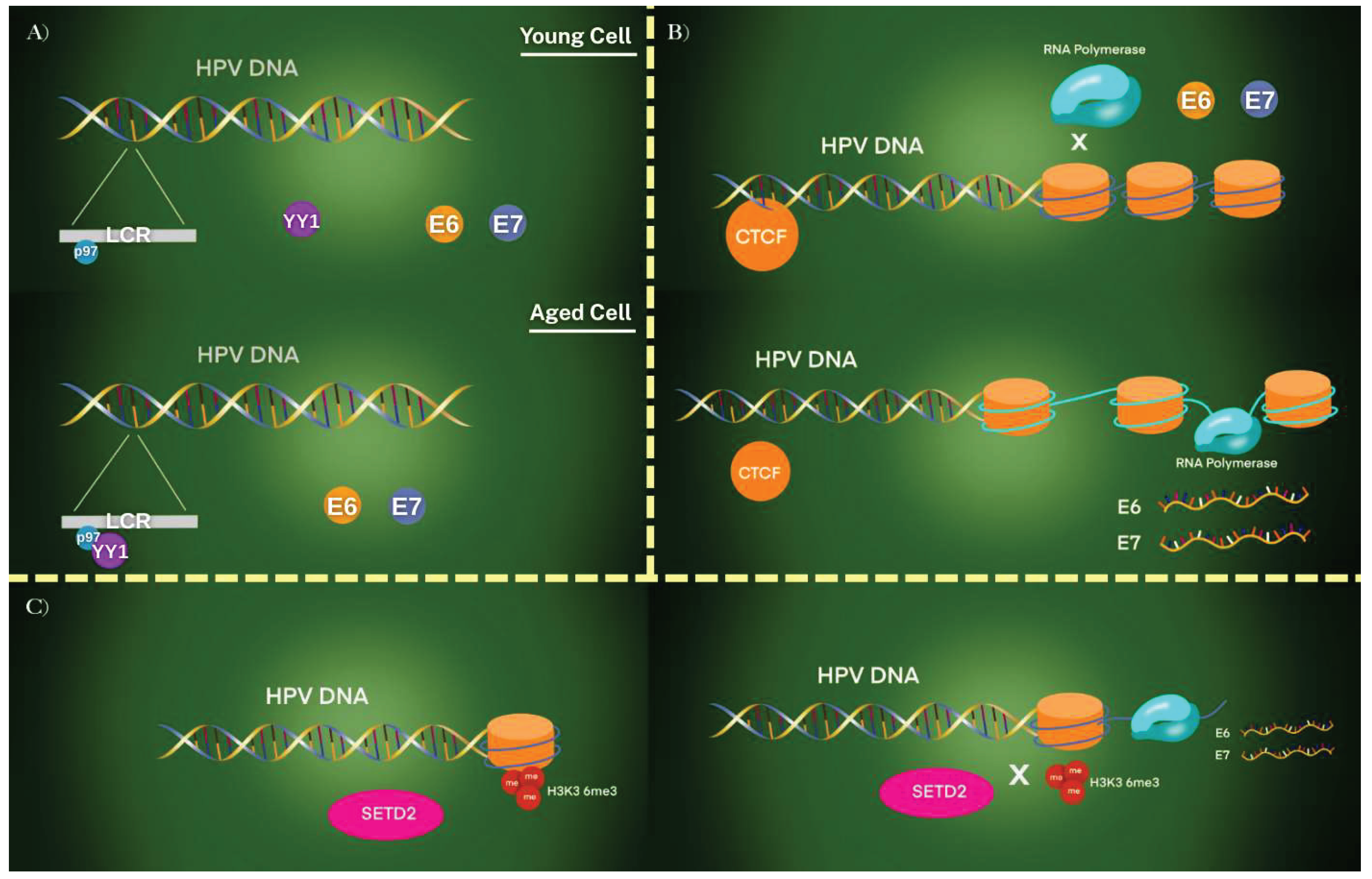

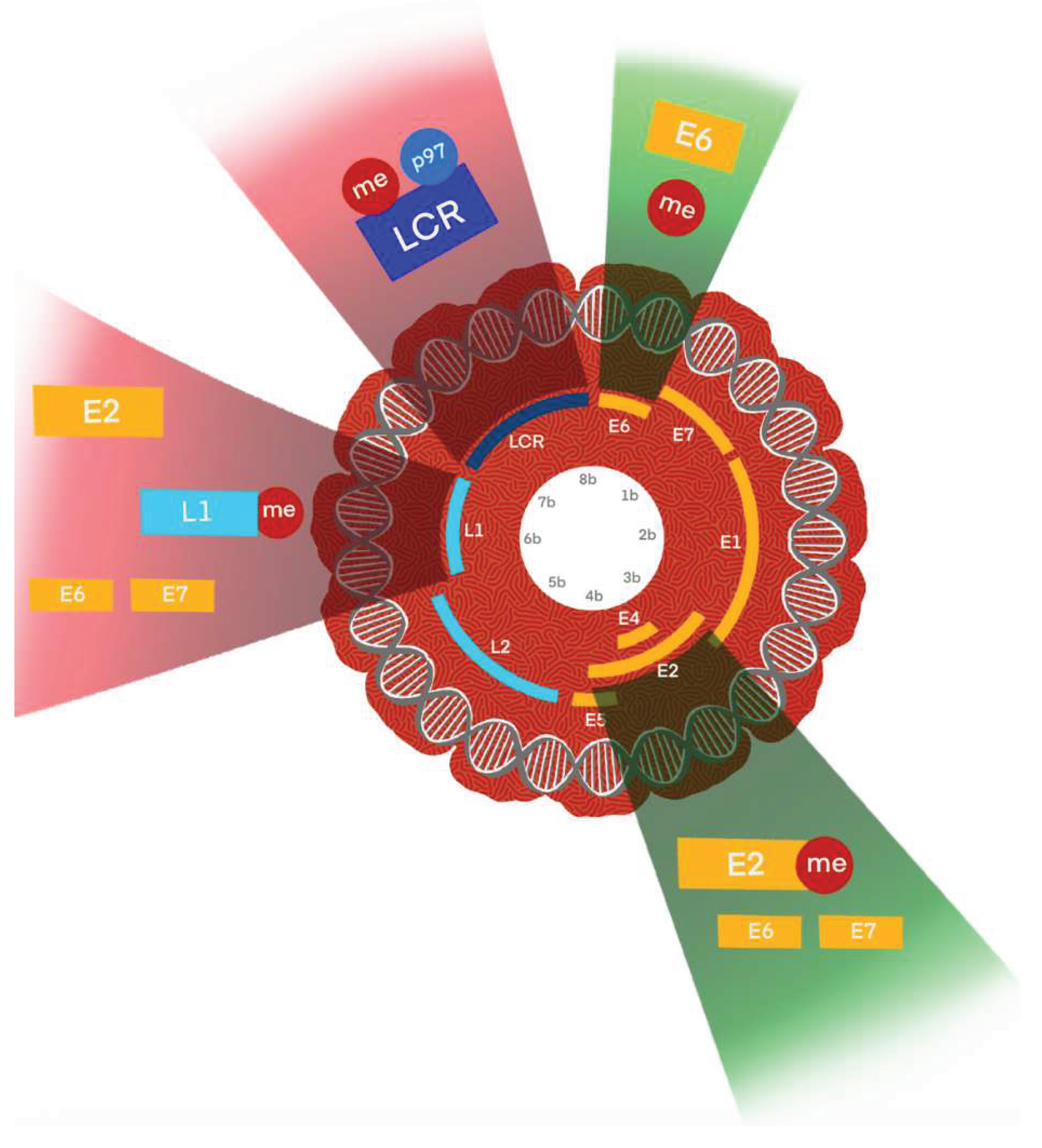

3.2. HPV Mechanism Affected by Epigenetic Regulation

3.3. The Role of DNA Methylation in the HPV Mechanism

3.4. Long Non-Coding RNAs

3.5. Epigenetic Alterations and Their Potential as Biomarker

4. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

4.1. Symptoms and Presentation

4.2. Diagnostic Methods and Challenges

4.2.1. Key Diagnostic Differences

-

Histopathology and p16 Immunohistochemistry:

- p16 Overexpression: One of the hallmark features of HPV related HNCs is the overexpression of p16, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for p16 is widely used as a surrogate marker for HPV infection, particularly in oropharyngeal cancers. p16 positivity, although not entirely specific for HPV, correlates strongly with the presence of oncogenic HPV, especially HPV16 [70,71,72].

-

HPV DNA/RNA Testing:

-

Comparison with HPV Negative HNCs:

- HPV negative HNCs are less likely to show p16 overexpression and typically do not harbor HPV DNA/RNA. Instead, these cancers are more often associated with mutations in genes like TP53, which are linked to tobacco exposure. The absence of HPV biomarkers in HPV nonrelated HNCs highlights the importance of differentiating between these two subtypes for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning [80,81,82].

4.2.2. Emerging Diagnostic Methods for HPV related HNCs

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): NGS allows for comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, providing insights into the genetic landscape of HPV related HNCs [84]. This technique can identify viral integration sites, mutation signatures, and other molecular features unique to HPV related tumors. NGS also helps in distinguishing HPV related from HPV nonrelated tumors by identifying characteristic mutations or the absence thereof [85].

- Liquid Biopsy: Liquid biopsy is an innovative, non-invasive diagnostic tool that analyzes circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or HPV DNA in the bloodstream. This approach holds promise for early detection, monitoring disease progression, and assessing treatment response in HPV related HNC patients. Liquid biopsy could potentially overcome some of the limitations of tissue biopsies, particularly in cases where tumor tissue is difficult to access [86].

- Circulating Biomarkers: Beyond ctDNA, circulating biomarkers such as antibodies against HPV oncoproteins (E6 and E7) and miRNAs are being studied for their potential role in the diagnosis and prognosis of HPV related HNCs. These biomarkers could offer a non-invasive method to monitor disease status and guide therapeutic decisions [87,88].

4.2.3. Challenges in the Diagnosis of HPV Related HNCs

- False Positives and Negatives: While p16 IHC is a valuable tool, it is not infallible. False positives can occur in HPV nonrelated tumors that exhibit p16 overexpression without the presence of HPV DNA. Conversely, false negatives may arise in HPV related tumors with low p16 expression. Combining p16 IHC with HPV DNA/RNA testing is essential to mitigate these risks [71].

- Tumor Heterogeneity: HPV related HNCs exhibit considerable heterogeneity, not only in terms of HPV subtypes but also in their biological behavior and response to treatment. This heterogeneity complicates the diagnostic process, necessitating a multifaceted approach that includes histopathology, molecular testing, and biomarker analysis [89,90].

4.2.3. Role of Biomarkers in Diagnosis

5. Treatment and Prognosis

5.1. Standard Treatment Approaches for HPV Related HNCs

- Radiotherapy: Radiotherapy (RT) is often the cornerstone of treatment for HPV related oropharyngeal cancers, particularly in patients with early-stage disease. HPV related tumors are generally more radiosensitive compared to HPV nonrelated tumors, which allows for effective tumor control with potentially lower doses of radiation. Given the favorable prognosis of HPV related HNCs, there has been increasing interest in treatment de-escalation, aiming to reduce the long-term toxicity associated with standard doses of radiation. Studies are exploring reduced radiation doses and the omission of concurrent chemotherapy in selected patients with favorable prognostic features [98,99,100,101].

- Chemoradiotherapy (CRT): For locally advanced HPV related HNCs, concurrent chemoradiotherapy remains a standard approach. The combination of radiation with platinum-based chemotherapy, such as cisplatin, enhances treatment efficacy by sensitizing tumor cells to radiation. Given the high response rates observed in HPV related tumors, there is ongoing research into reducing chemotherapy intensity or exploring alternative agents with fewer side effects [102,103,104,105].

- Surgery: Minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS), are increasingly being used for HPV related oropharyngeal cancers. TORS allows for precise tumor resection with minimal morbidity and may be followed by adjuvant radiation or chemoradiotherapy depending on the pathological findings [106,107].

5.2. Emerging and Investigational Treatment Modalities

5.3. Prognosis and Survival Outcomes

| Key Features | HPV Related HNC | HPV Nonrelated HNC |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and Presentation | Subtle and insidious onset | More pronounced and diverse symptoms |

| Often asymptomatic in early stages | Severe throat pain, dysphagia, otalgia, vocal changes | |

| Painless cervical lymphadenopathy | Often detected at a later stage | |

| Localized symptoms | Associated with tobacco and alcohol use | |

| Associated with lymphoid-rich areas (e.g., tonsils, base of tongue) | ||

| Methods | p16 overexpression used as a surrogate marker | More traditional diagnostic approaches |

| HPV DNA/RNA testing | Less reliance on p16 and HPV biomarkers | |

| Emerging techniques like NGS and liquid biopsy | Diagnosis often based on clinical presentation and histopathology | |

| Biomarkers in Diagnosis | p16 immunohistochemistry | Less reliance on HPV biomarkers |

| HPV DNA/RNA testing | Often associated with mutations in genes like TP53 | |

| Emerging biomarkers such as circulating miRNAs and antibodies against HPV oncoproteins (E6/E7) | Importance of differentiating from HPV related HNCs for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning | |

| Treatment | Radiotherapy, Chemoradiotherapy | More aggressive treatment required |

| Transoral Robotic Surgery | Often involves higher doses of radiation and more intensive chemotherapy | |

| Ongoing research in treatment de-escalation | Higher rates of treatment-related toxicities | |

| Immunotherapy, targeted therapies, and personalized medicine | Challenges in treating more advanced disease | |

| Prognosis and Survival | Generally favorable prognosis | Poorer prognosis |

| Five-year survival rates can exceed 80% | Five-year survival rates typically around 47% | |

| Better response to treatment | Higher rates of acute and long-term toxicities | |

| Prognosis negatively impacted by concurrent smoking | Reduced quality of life |

6. HPV Vaccines and Avoiding HPV Related HNCs

6.1. Studies of Therapeutic Vaccines

6.2. Effectiveness of HPV Vaccines in Preventing Head and Neck Cancers

6.3. HPV Vaccination Strategies and Challenges: A Critical Step in Cancer Prevention

7. Ongoing research HNCs – related to HPV

7.1. Oropharyngeal Cancer

7.2. Laryngeal Cancer

7.3. Hypopharyngeal Cancer

7.4. Sinonasal Cancer

7.5. Nasopharyngeal Cancer

7.6. Salivary Gland Cancer

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HNCs | Head and neck cancers |

| 9vHPV | 9-valent HPV vaccine |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| circRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| CRT | Chemoradiotherapy |

| CTCF | CCCTC-binding factor |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| E2BS | E2 binding sites |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HNSCCs | Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas |

| HPSCC | Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| HPV+NPC | HPV related nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IMPT | Intensity-modulated proton therapy |

| ISH | In situ hybridization |

| LCR | The long control region |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| LSCC | Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma |

| me | Methylation |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| MRD | Minimal residual disease |

| NCDB | National Cancer Database |

| ncRNAs | Non-coding RNAs |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| OPC | Oropharyngeal cancers |

| OPSCC | Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| pRb | Retinoblastoma protein |

| R/M HNSCC | Recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SETD2 | SET-domain containing protein 2 |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin1 |

| SNSCC | Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma |

| TORS | Transoral Robotic Surgery |

| URR | Upstream regulatory region |

| VLPs | Virus-like particles |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WRN | Werner Syndrome Protein |

| YY1 | Yin Yang 1 |

References

- Anderson, G.; Ebadi, M.; Vo, K.; Novak, J.; Govindarajan, A.; Amini, A. An Updated Review on Head and Neck Cancer Treatment with Radiation Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, M.D.; Rocco, J.W.; Yom, S.S.; Haddad, R.I.; Saba, N.F. Head and Neck Cancer. The Lancet 2021, 398, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, D.G.; Spencer, S.; Adelstein, D.; Adkins, D.; Anzai, Y.; Brizel, D.M.; Bruce, J.Y.; Busse, P.M.; Caudell, J.J.; Cmelak, A.J.; et al. Head and Neck Cancers, Version 2. 2020. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2020, 18, 873–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormley, M.; Creaney, G.; Schache, A.; Ingarfield, K.; Conway, D.I. Reviewing the Epidemiology of Head and Neck Cancer: Definitions, Trends and Risk Factors. Br Dent J 2022, 233, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.; Ebadi, M.; Vo, K.; Novak, J.; Govindarajan, A.; Amini, A. An Updated Review on Head and Neck Cancer Treatment with Radiation Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, F. dos S. ; Fernandes, G.A.; Antunes, J.L.F.; Villa, L.L.; Toporcov, T.N. Global Incidence Trends in Head and Neck Cancer for HPV-Related and -Unrelated Subsites: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. Oral Oncol 2021, 115, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oropharyngeal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - NCI.

- Stelzle, D.; Tanaka, L.F.; Lee, K.K.; Ibrahim Khalil, A.; Baussano, I.; Shah, A.S. V; McAllister, D.A.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Klug, S.J.; Winkler, A.S.; et al. Estimates of the Global Burden of Cervical Cancer Associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health 2021, 9, e161–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosper, P.F.; Bradley, S.; Luo, Q.; Kimple, R.J. Biology of HPV Mediated Carcinogenesis and Tumor Progression. Semin Radiat Oncol 2021, 31, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Shu, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Zheng, Z.M.; Albers, A.E.; Qian, X. Current Status of Human Papillomavirus-Related Head and Neck Cancer: From Viral Genome to Patient Care. Virol Sin 2021, 36, 1284–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vats, A.; Trejo-Cerro, O.; Thomas, M.; Banks, L. Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: What Remains? Tumour Virus Res 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marur, S.; D’Souza, G.; Westra, W.H.; Forastiere, A.A. HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer: A Virus-Related Cancer Epidemic. Lancet Oncol 2010, 11, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, V.X.; Long, S.; Tassler, A. Smoking and Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2023, 149, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Shu, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Zheng, Z.M.; Albers, A.E.; Qian, X. Current Status of Human Papillomavirus-Related Head and Neck Cancer: From Viral Genome to Patient Care. Virol Sin 2021, 36, 1284–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndon, S.; Singh, A.; Ha, P.K.; Aswani, J.; Chan, J.Y.K.; Xu, M.J. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Global Epidemiology and Public Policy Implications. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vani, N. V.; Madhanagopal, R.; Swaminathan, R.; Ganesan, T.S. Dynamics of Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection in Healthy Population and Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 11731–11745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymonowicz, K.A.; Chen, J. Biological and Clinical Aspects of HPV-Related Cancers. Cancer Biol Med 2020, 17, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Characteristics of HPV Associated versus Non-HPV Associated Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (HNSCC) Clinical Characteristics HPV Status; 2024.

- Mehanna, H.; Taberna, M.; von Buchwald, C.; Tous, S.; Brooks, J.; Mena, M.; Morey, F.; Grønhøj, C.; Rasmussen, J.H.; Garset-Zamani, M.; et al. Prognostic Implications of P16 and HPV Discordance in Oropharyngeal Cancer (HNCIG-EPIC-OPC): A Multicentre, Multinational, Individual Patient Data Analysis. Lancet Oncol 2023, 24, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.; Hisamatsu, K.; Suzui, N.; Hara, A.; Tomita, H.; Miyazaki, T. A Review of HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancer. J Clin Med 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Characteristics of HPV Associated versus Non-HPV Associated Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (HNSCC) Clinical Characteristics HPV Status; 2024.

- Thompson, L.D.R. HPV-Related Multiphenotypic Sinonasal Carcinoma. Ear Nose Throat J 2020, 99, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, D.; Kalarani, I.B.; Mohammed, V.; Veerabathiran, R. Potential Role of Human Papillomavirus Proteins Associated with the Development of Cancer. Virusdisease 2022, 33, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burley, M.; Roberts, S.; Parish, J.L. Epigenetic Regulation of Human Papillomavirus Transcription in the Productive Virus Life Cycle. Semin Immunopathol 2020, 42, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petca, A.; Borislavschi, A.; Zvanca, M.; Petca, R.-C.; Sandru, F.; Dumitrascu, M. Non-Sexual HPV Transmission and Role of Vaccination for a Better Future (Review). Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-J.; Yang, A.; Wu, T.-C.; Hung, C.-F. Immunotherapy for Human Papillomavirus-Associated Disease and Cervical Cancer: Review of Clinical and Translational Research. J Gynecol Oncol 2016, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Structure of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) LEAM Solution Fluorescence Microscope Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Transmission of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Replication of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Pathogenesis of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Clinical Manifestations of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) How You Can See Earth in a Whole New Light With These Insane Time-Lapses.

- Antonishyn, N.A. The Utility of Hpv Typing and Relative Quantification of HPV-16 Transcripts for Monitoring HPV Vaccine Efficacy and Improving Colposcopy Triage of Women with Abnormal Cervical Cyto; 2014.

- Ullah, M.I.; Mikhailova, M. V.; Alkhathami, A.G.; Carbajal, N.C.; Zuta, M.E.C.; Rasulova, I.; Najm, M.A.A.; Abosoda, M.; Alsalamy, A.; Deorari, M. Molecular Pathways in the Development of HPV-Induced Oropharyngeal Cancer. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, G.H.; Salman, N.A. Pathogenesis of Human Papillomavirus – Immunological Responses to HPV Infection. In Human Papillomavirus - Research in a Global Perspective; InTech, 2016.

- Kombe Kombe, A.J.; Li, B.; Zahid, A.; Mengist, H.M.; Bounda, G.-A.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, T. Epidemiology and Burden of Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases, Molecular Pathogenesis, and Vaccine Evaluation. Front Public Health 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, A.A.; Warburton, A. The Role of Integration in Oncogenic Progression of HPV-Associated Cancers. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfenov, M.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Gehlenborg, N.; Freeman, S.S.; Danilova, L.; Bristow, C.A.; Lee, S.; Hadjipanayis, A.G.; Ivanova, E. V.; Wilkerson, M.D.; et al. Characterization of HPV and Host Genome Interactions in Primary Head and Neck Cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 15544–15549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo-Teh, N.S.L.; Ito, Y.; Jha, S. High-Risk Human Papillomaviral Oncogenes E6 and E7 Target Key Cellular Pathways to Achieve Oncogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, G.H.; Tsirimonaki, E.; Marchetti, B.; O’Brien, P.M.; Sibbet, G.J.; Andrew, L.; Campo, M.S. Down-Regulation of MHC Class I by Bovine Papillomavirus E5 Oncoproteins. Oncogene 2002, 21, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, F.; Zaidi, M.; Fakhry, C.; Gaykalova, D.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Human Papillomavirus-Related Carcinogenesis in Head and Neck Cancer. Microbes Infect 2017, 19, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vats, A.; Trejo-Cerro, O.; Thomas, M.; Banks, L. Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: What Remains? Tumour Virus Res 2021, 11, 200213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.W.; Lilie, H.; Kalbacher, H.; Roos, N.; Frecot, D.I.; Feige, M.; Conrady, M.; Votteler, T.; Cousido-Siah, A.; Bartoli, G.C.; et al. Evidence for Direct Interaction between the Oncogenic Proteins E6 and E7 of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelin, J.; Sabol, I.; Tomaić, V. Do or Die: HPV E5, E6 and E7 in Cell Death Evasion. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosper, P.F.; Bradley, S.; Luo, Q.; Kimple, R.J. Biology of HPV Mediated Carcinogenesis and Tumor Progression. Semin Radiat Oncol 2021, 31, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Shen, J.; Chen, J.; Hong, J.; Xu, Y.; Qian, C. Prophylactic and Therapeutic HPV Vaccines: Current Scenario and Perspectives. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, A.A. Human Papillomaviruses: Diversity, Infection and Host Interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Oropeza, R.; Piña-Sánchez, P. Epigenetic and Transcriptomic Regulation Landscape in HPV+ Cancers: Biological and Clinical Implications. Front Genet 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, I.J.; Tang, G.; Pentland, I.; Parish, J.L.; Coleman, N. CTCF Association with Episomal HPV16 Genomes Regulates Viral 1 Oncogene Transcription and Splicing 2 3. [CrossRef]

- James, C.D.; Das, D.; Morgan, E.L.; Otoa, R.; Macdonald, A.; Morgan, I.M. Werner Syndrome Protein (WRN) Regulates Cell Proliferation and the Human Papillomavirus 16 Life Cycle during Epithelial Differentiation. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac, M.; Moody, C.A. Epigenetic Regulation of the Human Papillomavirus Life Cycle. Pathogens 2020, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac, M.; DeVico, B.M.; Raspanti, S.M.; Moody, C.A. The SETD2 Methyltransferase Supports Productive HPV31 Replication through the LEDGF/CtIP/Rad51 Pathway. J Virol 2023, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Kurokawa, T.; Mima, M.; Imamoto, S.; Mizokami, H.; Kondo, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Misawa, K.; Hanazawa, T.; Kaneda, A. DNA Methylation and HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Knebel Doeberitz, M.; Prigge, E.-S. Role of DNA Methylation in HPV Associated Lesions. Papillomavirus Research 2019, 7, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M.A.; Wentzensen, N.; Mirabello, L.; Ghosh, A.; Wacholder, S.; Harari, A.; Lorincz, A.; Schiffman, M.; Burk, R.D. Human Papillomavirus DNA Methylation as a Potential Biomarker for Cervical Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2012, 21, 2125–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenigul, N.N.; Yazıcı Yılmaz, F.; Ayhan, I. Can Serum Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels Predict HPV Penetration in Patients with ASCUS? Nutr Cancer 2021, 73, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casarotto, M.; Fanetti, G.; Guerrieri, R.; Palazzari, E.; Lupato, V.; Steffan, A.; Polesel, J.; Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; Fratta, E. Beyond MicroRNAs: Emerging Role of Other Non-Coding RNAs in HPV-Driven Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonelli, P.; Borrelli, A.; Tuccillo, F.M.; Buonaguro, F.M.; Tornesello, M.L. The Role of CircRNAs in Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Munger, K. The Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Pathogenesis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Liu, F.; Yang, A.-G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in the Pathogenesis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2022, 24, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, T.R.; Santos, J.M.O.; Gil da Costa, R.M.; Medeiros, R. Long Non-Coding RNAs Regulate the Hallmarks of Cancer in HPV-Induced Malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021, 161, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Munger, K. Expression of the Cervical Carcinoma Expressed PCNA Regulatory (CCEPR) Long Noncoding RNA Is Driven by the Human Papillomavirus E6 Protein and Modulates Cell Proliferation Independent of PCNA. Virology 2018, 518, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.A.; Hayes, K.E.; Brownmiller, T.; Harold, A.D.; Jagannathan, R.; Lockman, P.R.; Khan, S.; Martinez, I. Long Non-Coding RNA FAM83H-AS1 Is Regulated by Human Papillomavirus 16 E6 Independently of P53 in Cervical Cancer Cells. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopczyńska, M.; Kolenda, T.; Guglas, K.; Sobocińska, J.; Teresiak, A.; Bliźniak, R.; Mackiewicz, A.; Mackiewicz, J.; Lamperska, K. PRINS LncRNA Is a New Biomarker Candidate for HPV Infection and Prognosis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinić, S.; Rich, A.; Anayannis, N. V.; Cabarcas-Petroski, S.; Schramm, L.; Meneses, P.I. Gene Expression and DNA Methylation in Human Papillomavirus Positive and Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Lian, Y.; Tao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, S. Relationship between P16/Ki67 Immunoscores and PAX1/ZNF582 Methylation Status in Precancerous and Cancerous Cervical Lesions in High-Risk HPV-Positive Women. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.F.; Vu, L.; Spanos, W.C.; Pyeon, D. The Key Differences between Human Papillomavirus-Positive and -Negative Head and Neck Cancers: Biological and Clinical Implications. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, S.; Sethi, R.K.V.; Wang, A.; Dabekaussen, K.; Egloff, A.M.; Del Vecchio Fitz, C.; Kuperwasser, C.; Uppaluri, R.; Shin, J.; Rettig, E.M. Circulating Tumor-Tissue Modified HPV DNA Testing in the Clinical Evaluation of Patients at Risk for HPV-Positive Oropharynx Cancer: The IDEA-HPV Study. Oral Oncol 2023, 147, 106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, M.D.; Clegg, D.; Belcastro, A.; Smith, B.D.; Eric Heidel, R.; Carlson, E.R.; Hechler, B. Are Throat Pain and Otalgia Predictive of Perineural Invasion in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2022, 80, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran, K.; Carey, R.M.; Lin, X.; Seckar, T.D.; Wei, Z.; Chorath, K.; Newman, J.G.; O’Malley, B.W.; Weinstein, G.S.; Feldman, M.D.; et al. The Microbiome of HPV-Positive Tonsil Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Neck Metastasis. Oral Oncol 2021, 117, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhania, N.; Mishra, A. Alcohol Consumption, Tobacco Use, and Viral Infections: A Multifactorial Approach to Understanding Head and Neck Cancer Risk.

- McIlwain, W.R.; Sood, A.J.; Nguyen, S.A.; Day, T.A. Initial Symptoms in Patients With HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Oropharyngeal Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2014, 140, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitzer, G.C.; Smith, M.A.; Harris, S.L.; Kimple, R.J. Review of the Clinical and Biologic Aspects of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Head and Neck. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2014, 88, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, M.N.; Faísca, P.; Ferreira, H.A.; Gaspar, M.M.; Reis, C.P. Current Insights and Progress in the Clinical Management of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillison, M.L.; Koch, W.M.; Capone, R.B.; Spafford, M.; Westra, W.H.; Wu, L.; Zahurak, M.L.; Daniel, R.W.; Viglione, M.; Symer, D.E.; et al. Evidence for a Causal Association Between Human Papillomavirus and a Subset of Head and Neck Cancers.

- Simoens, C.; Gheit, T.; Ridder, R.; Gorbaslieva, I.; Holzinger, D.; Lucas, E.; Rehm, S.; Vermeulen, P.; Lammens, M.; Vanderveken, O.M.; et al. Accuracy of High-Risk HPV DNA PCR, P16(INK4a) Immunohistochemistry or the Combination of Both to Diagnose HPV-Driven Oropharyngeal Cancer. BMC Infect Dis 2022, 22, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallus, R.; Nauta, I.H.; Marklund, L.; Rizzo, D.; Crescio, C.; Mureddu, L.; Tropiano, P.; Delogu, G.; Bussu, F. Accuracy of P16 IHC in Classifying HPV-Driven OPSCC in Different Populations. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubilla, A.L.; Lloveras, B.; Alejo, M.; Clavero, O.; Chaux, A.; Kasamatsu, E.; Velazquez, E.F.; Lezcano, C.; Monfulleda, N.; Tous, S.; et al. The Basaloid Cell Is the Best Tissue Marker for Human Papillomavirus in Invasive Penile Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Study of 202 Cases From Paraguay. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2010, 34, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppel, F.; Gendreizig, S.; Martinez-Ruiz, L.; Florido, J.; López-Rodríguez, A.; Pabla, H.; Loganathan, L.; Hose, L.; Kühnel, P.; Schmidt, P.; et al. Mucosa-like Differentiation of Head and Neck Cancer Cells Is Inducible and Drives the Epigenetic Loss of Cell Malignancy. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaux, A.; Sanchez, D.F.; Fernández-Nestosa, M.J.; Cañete-Portillo, S.; Rodríguez, I.M.; Giannico, G.A.; Cubilla, A.L. The Dual Pathogenesis of Penile Neoplasia: The Heterogeneous Morphology of Human Papillomavirus-Related Tumors. Asian J Urol 2022, 9, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baněčková, M.; Cox, D. Top 10 Basaloid Neoplasms of the Sinonasal Tract. Head Neck Pathol 2023, 17, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi Rossi, P.; Carozzi, F.; Ronco, G.; Allia, E.; Bisanzi, S.; Gillio-Tos, A.; De Marco, L.; Rizzolo, R.; Gustinucci, D.; Del Mistro, A.; et al. P16/Ki67 and E6/E7 MRNA Accuracy and Prognostic Value in Triaging HPV DNA-Positive Women. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2021, 113, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi Rossi, P.; Ronco, G.; Mancuso, P.; Carozzi, F.; Allia, E.; Bisanzi, S.; Gillio-Tos, A.; De Marco, L.; Rizzolo, R.; Gustinucci, D.; et al. Performance of <scp>HPV E6</Scp> / <scp>E7 MRNA</Scp> Assay as Primary Screening Test: Results from the <scp>NTCC2</Scp> Trial. Int J Cancer 2022, 151, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, K.; Shah, P. V.; Coates, S.; Alexiev, B.A.; Samant, S. In Situ Hybridization for High Risk HPV E6/E7 MRNA in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Otolaryngol 2021, 42, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klussmann, J.P.; Gültekin, E.; Weissenborn, S.J.; Wieland, U.; Dries, V.; Dienes, H.P.; Eckel, H.E.; Pfister, H.J.; Fuchs, P.G. Expression of P16 Protein Identifies a Distinct Entity of Tonsillar Carcinomas Associated with Human Papillomavirus. Am J Pathol 2003, 162, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blons, H.; Laurent-Puig, P. TP53 and Head and Neck Neoplasms. Hum Mutat 2003, 21, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, T.; Li, S.; Henry, L.E.; Liu, S.; Sartor, M.A. Molecular Tumor Subtypes of HPV-Positive Head and Neck Cancers: Biological Characteristics and Implications for Clinical Outcomes. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krsek, A.; Baticic, L.; Braut, T.; Sotosek, V. The Next Chapter in Cancer Diagnostics: Advances in HPV-Positive Head and Neck Cancer. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.H.; Sais, D.; Tran, N. Advances in Human Papillomavirus Detection and Molecular Understanding in Head and Neck Cancers: Implications for Clinical Management. J Med Virol 2024, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocjan, B.J.; Bzhalava, D.; Forslund, O.; Dillner, J.; Poljak, M. Molecular Methods for Identification and Characterization of Novel Papillomaviruses. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2015, 21, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantre-Justino, M.; Alves, G.; Delmonico, L. Clinical Applications of Liquid Biopsy in HPV-negative and HPV-positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Advances and Challenges. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 2022, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberly, H.W.; Sciscent, B.Y.; Lorenz, F.J.; Rettig, E.M.; Goyal, N. Current and Emerging Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Predictive Biomarkers in Head and Neck Cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.M.; Tjoa, T.; Armstrong, W.B. Circulating Tumor <scp>HPV</Scp> - <scp>DNA</Scp> in the Management of <scp>HPV</Scp> -Positive Oropharyngeal Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Head Neck 2025. [CrossRef]

- Reid, P.; Marcu, L.G.; Olver, I.; Moghaddasi, L.; Staudacher, A.H.; Bezak, E. Diversity of Cancer Stem Cells in Head and Neck Carcinomas: The Role of HPV in Cancer Stem Cell Heterogeneity, Plasticity and Treatment Response. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2019, 135, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keck, M.K.; Zuo, Z.; Khattri, A.; Stricker, T.P.; Brown, C.D.; Imanguli, M.; Rieke, D.; Endhardt, K.; Fang, P.; Brägelmann, J.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Head and Neck Cancer Identifies Two Biologically Distinct HPV and Three Non-HPV Subtypes. Clinical Cancer Research 2015, 21, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindele, A.; Holm, A.; Nylander, K.; Allard, A.; Olofsson, K. Mapping Human Papillomavirus, Epstein–Barr Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Adenovirus, and P16 in Laryngeal Cancer. Discover Oncology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritzen, B.B.; Sjöstedt, S.; Jensen, J.M.; Kiss, K.; von Buchwald, C. Unusual Cases of Sinonasal Malignancies: A Letter to the Editor on HPV-Positive Sinonasal Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2023, 62, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojtechova, Z.; Sabol, I.; Salakova, M.; Smahelova, J.; Zavadil, J.; Turek, L.; Grega, M.; Klozar, J.; Prochazka, B.; Tachezy, R. Comparison of the MiRNA Profiles in HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Tonsillar Tumors and a Model System of Human Keratinocyte Clones. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, S.; Sharma, P.; Wise, P.; Sposto, R.; Hollingshead, D.; Lamb, J.; Lang, S.; Fabbri, M.; Whiteside, T.L. MRNA and MiRNA Profiles of Exosomes from Cultured Tumor Cells Reveal Biomarkers Specific for HPV16-Positive and HPV16-Negative Head and Neck Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannigrahi, M.K.; Sharma, R.; Singh, V.; Panda, N.K.; Rattan, V.; Khullar, M. DNA Methylation Regulated MicroRNAs in HPV-16-Induced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC). Mol Cell Biochem 2018, 448, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, S.; Wang, R. Therapeutic Strategies of Different HPV Status in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Epidemiology, Molecular Biology and Clinical Management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.M. De-Escalation Treatment for Human Papillomavirus–Related Oropharyngeal Cancer: Questions for Practical Consideration. Cancer Network 2023.

- Nissi, L. P16 AND XCT AS BIOMARKERS IN OROPHARYNGEAL SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA AND BEYOND.

- García-Anaya, M.; Segado-Guillot, S.; Cabrera-Rodríguez, J.; Toledo-Serrano, M.; Medina-Carmona, J.; Gómez-Millán, J. Dose and Volume De-Escalation of Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2023, 186, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.J.; Vokes, E.E. Optimizing Treatment De-Escalation in Head and Neck Cancer: Current and Future Perspectives. Oncologist 2021, 26, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, Md.T.; Ghosh, A.K.; Khatun, R.A.; Hussain, Q.M.; Mollah, Md.N.U.; Hussain, S.Md.A.; Habib, A.K.M.A.; Hosen, M.M.A.; Rahim, I.U. Comparison of Outcome of Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy and Sequential Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced, Inoperable Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck Region. Saudi Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 10, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.J.; Torres-Saavedra, P.A.; Saba, N.F.; Shenouda, G.; Bumpous, J.M.; Wallace, R.E.; Chung, C.H.; El-Naggar, A.K.; Gwede, C.K.; Burtness, B.; et al. Radiotherapy Plus Cisplatin With or Without Lapatinib for Non–Human Papillomavirus Head and Neck Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2023, 9, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, S.; Wang, R. Therapeutic Strategies of Different HPV Status in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassen, P.; Huang, S.H.; Su, J.; Waldron, J.; Andersen, M.; Primdahl, H.; Johansen, J.; Kristensen, C.A.; Andersen, E.; Eriksen, J.G.; et al. Treatment Outcomes and Survival Following Definitive (Chemo)Radiotherapy in <scp>HPV</Scp> -positive Oropharynx Cancer: Large-scale Comparison of <scp>DAHANCA</Scp> vs <scp>PMH</Scp> Cohorts. Int J Cancer 2022, 150, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holcomb, A.J.; Herberg, M.; Strohl, M.; Ochoa, E.; Feng, A.L.; Abt, N.B.; Mokhtari, T.E.; Suresh, K.; McHugh, C.I.; Parikh, A.S.; et al. Impact of Surgical Margins on Local Control in Patients Undergoing <scp>single-modality</Scp> Transoral Robotic Surgery for <scp>HPV-related</Scp> Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck 2021, 43, 2434–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; Gunasekera, D.; Krishnan, G.; Krishnan, S.; Hodge, J.; Lizarondo, L.; Foreman, A. Is Transoral Robotic Surgery Useful as a Salvage Technique in Head and Neck Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Head Neck 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtness, B.; Harrington, K.J.; Greil, R.; Soulières, D.; Tahara, M.; de Castro, G.; Psyrri, A.; Basté, N.; Neupane, P.; Bratland, Å.; et al. Pembrolizumab Alone or with Chemotherapy versus Cetuximab with Chemotherapy for Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-048): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. The Lancet 2019, 394, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saba, N.F.; Pamulapati, S.; Patel, B.; Mody, M.; Strojan, P.; Takes, R.; Mäkitie, A.A.; Cohen, O.; Pace-Asciak, P.; Vermorken, J.B.; et al. Novel Immunotherapeutic Approaches to Treating HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.F.; Liu, S. V.; Sukari, A.; Chung, C.H.; Bauml, J.; Haddad, R.I.; Gause, C.K.; Niewood, M.; Gammage, L.L.; Brown, H.; et al. KEYNOTE-055: A Phase II Trial of Single Agent Pembrolizumab in Patients (Pts) with Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) Who Have Failed Platinum and Cetuximab. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015, 33, TPS3094–TPS3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, K.; Chung, H.C.; Shankaran, V.; Geva, R.; Catenacci, D.; Gupta, S.; Eder, J.P.; Golan, T.; Le, D.T.; Burtness, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Patients with PD-L1-Positive Advanced Gastric Cancer (KEYNOTE-012): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 1b Trial. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Kounatidis, D.; Panagopoulos, F.; Geladari, E.; Karampela, I.; Stratigou, T.; Dalamaga, M. Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer: Where Do We Stand? Curr Oncol Rep 2023, 25, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian, R.; Savani, M.; Bauman, J.E. Immunotherapy Approaches in HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.; Martins, D.; Mendes, F. Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer When, How, and Why? Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseddine, A.A.; Burman, B.; Lee, N.Y.; Zamarin, D.; Riaz, N. Tumor Immunity and Immunotherapy for HPV-Related Cancers. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 1896–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Phase 1 Dose-Escalation and Expansion Study of CUE-101, given as Monotherapy and in Combination with Pembrolizumab, in Patients with Recurrent:Metastatic HPV16+ Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer (R:M HNSCC).

- Ho, A.L.; Nabell, L.; Neupane, P.C.; Posner, M.R.; Yilmaz, E.; Niu, J.; Naqash, A.R.; Pearson, A.T.; Wong, S.J.; Nieva, J.J.; et al. HB-200 Arenavirus-Based Immunotherapy plus Pembrolizumab as First-Line Treat-Ment of Patients with Recurrent/Metastatic HPV16-Positive Head and Neck Cancer: Updated Results; 2025.

- Rosenberg, A.J.; Juloori, A.; Izumchenko, E.; Cursio, J.; Gooi, Z.; Blair, E.A.; Lingen, M.W.; Cipriani, N.; Hasina, R.; Starus, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant HPV16-Specific Arenavirus-Based Immunotherapy HB-200 plus Chemotherapy Followed by Response-Stratified de-Intensification in HPV16+ Oro-Pharyngeal Cancer: TARGET-HPV; 2025.

- Yan, S.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, W.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Sintilimab and Platinum-Doublet Chemotherapy Followed by Transoral Robotic Surgery for HPV-Associated Resectable Oropharyngeal Cancer: Single-Arm, Phase II Trial; 2025.

- Chung, C.H.; Li, J.; Steuer, C.E.; Bhateja, P.; Johnson, M.; Masannat, J.; Poole, M.I.; Song, F.; Hernandez-Prera, J.C.; Molina, H.; et al. Phase II Multi-Institutional Clinical Trial Result of Concurrent Cetuximab and Nivolumab in Recurrent and/or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2022, 28, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Study (OpcemISA) of the Combination of ISA101b and Cemiplimab versus Cemiplimab for Recurrent:Metastatic (R:M) HPV16-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer (OPC).

- Li, Q.; Tie, Y.; Alu, A.; Ma, X.; Shi, H. Targeted Therapy for Head and Neck Cancer: Signaling Pathways and Clinical Studies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo, F.; Perez-Dominguez, F.; Osorio, J.C.; Oliva, C.; Calaf, G.M. PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway in HPV-Driven Head and Neck Carcinogenesis: Therapeutic Implications. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo, F.; Perez-Dominguez, F.; Osorio, J.C.; Oliva, C.; Calaf, G.M. PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway in HPV-Driven Head and Neck Carcinogenesis: Therapeutic Implications. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.Y.; Sherman, E.J.; Schöder, H.; Wray, R.; White, C.; Dunn, L.; Hung, T.; Pfister, D.G.; Ho, A.L.; Mcbride, S.M.; et al. Intra-Treatment Hypoxia Directed Major Radiation de-Escalation as Definitive Treatment for Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer; 2025.

- Burtness, B.; Flamand, Y.; Quon, H.; Weinstein, G.S.; Mehra, R.; Garcia, J.J.; Kim, S.; O, B.W.; Jr, malley; Ozer, E.; et al. Long-Term Follow up of E3311, a Phase II Trial of Transoral Surgery (TOS) Followed by Pathology-Based Adjuvant Treatment in HPV-Associated (HPV+) Oropharynx Cancer (OPC): A Trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group; 2025.

- Frank, S.J.; Busse, P.; Ira Rosenthal, D.; Hernandez, M.; Michael Swanson, D.; Garden, A.S.; Sturgis, E.M.; Ferrarotto, R.; Brandon Gunn, G.; Patel, S.H.; et al. Phase III Randomized Trial of Intensity-Modulated Proton Therapy (IMPT) versus Intensity-Modulated Photon Therapy (IMRT) for the Treatment of Head and Neck Oropharyngeal Carcinoma (OPC); 2025.

- Hirayama, S.; Al-Inaya, Y.; Aye, L.; Bryan, M.E.; Das, D.; Mendel, J.; Naegele, S.; Faquin, W.C.; Sadow, P.; Fisch, A.S.; et al. Prospective Validation of CtHPVDNA for Detection of Minimal Residual Disease and Prediction of Recurrence in Patients with HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer Treated with Surgery; 2025.

- Wei, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, X. Description of CRISPR-Cas9 Development and Its Prospects in Human Papillomavirus-Driven Cancer Treatment. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, S.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Chen, W.; Li, X. Synergistic Antitumor Effect on Cervical Cancer by Rational Combination of PD1 Blockade and CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated HPV Knockout. Cancer Gene Ther 2020, 27, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, T.; He, D.; Tian, R.; Cui, Z.; Tian, X.; Gao, Q.; Ma, X.; Yang, J.; et al. In Vitro and in Vivo Growth Inhibition of Human Cervical Cancer Cells via Human Papillomavirus E6/E7 MRNAs’ Cleavage by CRISPR/Cas13a System. Antiviral Res 2020, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarsheth, N.B.; Norberg, S.M.; Sinkoe, A.L.; Adhikary, S.; Meyer, T.J.; Lack, J.B.; Warner, A.C.; Schweitzer, C.; Doran, S.L.; Korrapati, S.; et al. TCR-Engineered T Cells Targeting E7 for Patients with Metastatic HPV-Associated Epithelial Cancers. Nat Med 2021, 27, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sandberg, M.L.; Martin, A.D.; Negri, K.R.; Gabrelow, G.B.; Nampe, D.P.; Wu, M.-L.; McElvain, M.E.; Toledo Warshaviak, D.; Lee, W.-H.; et al. Potent, Selective CARs as Potential T-Cell Therapeutics for HPV-Positive Cancers. Journal of Immunotherapy 2021, 44, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharkey Ochoa, I.; O’Regan, E.; Toner, M.; Kay, E.; Faul, P.; O’Keane, C.; O’Connor, R.; Mullen, D.; Nur, M.; O’Murchu, E.; et al. The Role of HPV in Determining Treatment, Survival, and Prognosis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimić, I.; Božinović, K.; Milutin Gašperov, N.; Kordić, M.; Pešut, E.; Manojlović, L.; Grce, M.; Dediol, E.; Sabol, I. Head and Neck Cancer Patients’ Survival According to HPV Status, MiRNA Profiling, and Tumour Features—A Cohort Study. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.-H.; Su, C.-C.; Wu, S.-Y.; Hsueh, W.-T.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chen, H.H.W.; Hsiao, J.-R.; Liu, C.-H.; Tsai, Y.-S. Impact of Alcohol and Smoking on Outcomes of HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Roest, R.H.; van der Heijden, M.; Wesseling, F.W.R.; de Ruiter, E.J.; Heymans, M.W.; Terhaard, C.; Vergeer, M.R.; Buter, J.; Devriese, L.A.; de Boer, J.P.; et al. Disease Outcome and Associated Factors after Definitive Platinum Based Chemoradiotherapy for Advanced Stage HPV-Negative Head and Neck Cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2022, 175, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, S.; Wang, R. Therapeutic Strategies of Different HPV Status in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.Z.; Jou, J.; Cohen, E. Vaccine Strategies for Human Papillomavirus-Associated Head and Neck Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. Laurent, J.; Luckett, R.; Feldman, S. HPV Vaccination and the Effects on Rates of HPV-Related Cancers. Curr Probl Cancer 2018, 42, 493–506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagón, T.; Franco, E.L.; Tejada, R.; Vaccarella, S. Epidemiology of HPV-Associated Cancers Past, Present and Future: Towards Prevention and Elimination. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2024, 21, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petca, A.; Borislavschi, A.; Zvanca, M.; Petca, R.-C.; Sandru, F.; Dumitrascu, M. Non-Sexual HPV Transmission and Role of Vaccination for a Better Future (Review). Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, E.Y.; Adjei Boakye, E.; Taylor, D.B.; Kuziez, D.; Rohde, R.L.; Pannu, J.S.; Simpson, M.C.; Patterson, R.H.; Varvares, M.A.; Osazuwa-Peters, N. Medical Students’ Knowledge of HPV, HPV Vaccine, and HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras, C.; Tsang, S.H.; Herrero, R.; Guillén, D.; Darragh, T.M.; Stoler, M.H.; Hildesheim, A.; Wagner, S.; Boland, J.; Lowy, D.R.; et al. Efficacy of the Bivalent HPV Vaccine against HPV 16/18-Associated Precancer: Long-Term Follow-up Results from the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribb, J.P.; Wheelock, J.H.; Park, E.S. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and the Current State of Oropharyngeal Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Dela J Public Health 2023, 9, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, V.; Jung, W.; Linde, C.; Coates, E.; Ledgerwood, J.; Costner, P.; Yamshchikov, G.; Streeck, H.; Juelg, B.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; et al. Differences in HPV-Specific Antibody Fc-Effector Functions Following Gardasil® and Cervarix® Vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Papillomavirus Vaccination INTRODUCTION.

- Rumfield, C.S.; Roller, N.; Pellom, S.T.; Schlom, J.; Jochems, C. Therapeutic Vaccines for HPV-Associated Malignancies. Immunotargets Ther 2020, 9, 167–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boilesen, D.R.; Nielsen, K.N.; Holst, P.J. Novel Antigenic Targets of HPV Therapeutic Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardella, B.; Gritti, A.; Soleymaninejadian, E.; Pasquali, M.; Riemma, G.; La Verde, M.; Schettino, M.; Fortunato, N.; Torella, M.; Dominoni, M. New Perspectives in Therapeutic Vaccines for HPV: A Critical Review. Medicina (B Aires) 2022, 58, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.; Cowell, L.G.; Tomkies, A.; Day, A.T. Therapeutic Vaccination for HPV-Mediated Cancers. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2023, 11, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skolnik, J.M.; Morrow, M.P. Vaccines for HPV-Associated Diseases. Mol Aspects Med 2023, 94, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, G.; Corica, C. Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine and Prevention of Head and Neck Cancer, What Is the Current Evidence? Oral Oncol 2021, 115, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndon, S.; Singh, A.; Ha, P.K.; Aswani, J.; Chan, J.Y.-K.; Xu, M.J. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Global Epidemiology and Public Policy Implications. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timbang, M.R.; Sim, M.W.; Bewley, A.F.; Farwell, D.G.; Mantravadi, A.; Moore, M.G. HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Review on Burden of the Disease and Opportunities for Prevention and Early Detection. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019, 15, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, G.; Corica, C. Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine and Prevention of Head and Neck Cancer, What Is the Current Evidence? Oral Oncol 2021, 115, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weekly Epidemiological Record Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire Sommaire.

- Morand, G.B.; Cardona, I.; Cruz, S.B.S.C.; Mlynarek, A.M.; Hier, M.P.; Alaoui-Jamali, M.A.; da Silva, S.D. Therapeutic Vaccines for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal and Cervical Cancer: The Next De-Intensification Strategy? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsentemeidou, A.; Fyrmpas, G.; Stavrakas, M.; Vlachtsis, K.; Sotiriou, E.; Poutoglidis, A.; Tsetsos, N. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine to End Oropharyngeal Cancer. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2021, 48, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsu, V.D.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Atuhebwe, P.; Bloem, P.N.; Ndiaye, C. National Implementation of HPV Vaccination Programs in Low-Resource Countries: Lessons, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Prev Med (Baltim) 2021, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lai, Y.M.; Holloway, A. The Status and Challenges of HPV Vaccine Programme in China: An Exploration of the Related Policy Obstacles. BMJ Glob Health 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanja-Chege, C.M. HPV Vaccination in Kenya: The Challenges Faced and Strategies to Increase Uptake. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, R.M.; Adrien, N.; Badiane, O.; Diallo, A.; Loko Roka, J.; Brennan, T.; Doshi, R.; Garon, J.; Loharikar, A. National Introduction of HPV Vaccination in Senegal—Successes, Challenges, and Lessons Learned. Vaccine 2022, 40, A10–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Xie, X.; Liu, J.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wu, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Kong, B.; Chen, W.; et al. Elimination of Cervical Cancer: Challenges Promoting the HPV Vaccine in China. Indian J Gynecol Oncol 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, J.; Yücel, M.; Kızılkaya, S.; Yıldırım, G.; Özyiğit, I.İ.; Yuluğkural, Z. HPV, HPV VACCINATION WORLDWIDE AND CURRENT STATUS OF HPV VACCINATION IN TURKEY: A LITERATURE REVIEW. TURKISH MEDICAL STUDENT JOURNAL 2022, 9, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadayi, E.; Karademir, D.; Karahan, S. Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors of Women Who Have or Have Not Had Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Turkey about the Virus and the Vaccine. J Community Health 2022, 47, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheed, D. e. N.; Schiller, J.; Stanley, M.; Franco, E.L.; Poljak, M.; Kjaer, S.K.; del Pino, M.; van der Klis, F.; Schim van der Loeff, M.F.; Baay, M.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Adults: Impact, Opportunities and Challenges – a Meeting Report. In Proceedings of the BMC Proceedings; BioMed Central Ltd, August 1 2021; Vol. 15.

- Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Graboyes, E.M.; Khariwala, S.S. Expanding Indications for the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: One Small Step for the Prevention of Head and Neck Cancer, but One Giant Leap Remains. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020, 146, 1099–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilley, S.; Miller, K.M.; Huh, W.K. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Ongoing Challenges and Future Directions. Gynecol Oncol 2020, 156, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira-Rodrigues, A.; Flores, M.G.; Macedo Neto, A.O.; Braga, L.A.C.; Vieira, C.M.; Sousa-Lima, R.M. de; de Andrade, D.A.P.; Machado, K.K.; Guimarães, A.P.G. HPV Vaccination in Latin America: Coverage Status, Implementation Challenges and Strategies to Overcome It. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbıyık, H.I.; Palalıoğlu, R.M. HPV Infection, HPV Vaccines and Cervical Cancer Awareness: A Multi-Centric Survey Study in Istanbul, Turkey. Women Health 2021, 61, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taberna, M.; Mena, M.; Pavón, M.A.; Alemany, L.; Gillison, M.L.; Mesía, R. Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer. Annals of Oncology 2017, 28, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribb, J.P.; Wheelock, J.H.; Park, E.S. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and the Current State of Oropharyngeal Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Dela J Public Health 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeramange, C.E.; Tang, K.D.; Irwin, D.; Hartel, G.; Langton-Lockton, J.; Ladwa, R.; Kenny, L.; Taheri, T.; Whitfield, B.; Vasani, S.; et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) DNA Methylation Changes in HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2024, 45, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wookey, V.B.; Appiah, A.K.; Kallam, A.; Ernani, V.; Smith, L.M.; Ganti, A.K. HPV Status and Survival in Non-Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Anticancer Res 2019, 39, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandić, K.; Milutin Gašperov, N.; Božinović, K.; Dediol, E.; Krasić, J.; Sinčić, N.; Grce, M.; Sabol, I.; Barešić, A. Integrative Analysis in Head and Neck Cancer Reveals Distinct Role of MiRNome and Methylome as Tumour Epigenetic Drivers. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shomorony, A.; Puram, S. V.; Johnson, D.N.; Chi, A.W.; Faquin, W.C.; Deshpande, V.; Deschler, D.G.; Emerick, K.S.; Sadow, P.M. A Non-Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and the Pitfalls of HPV Testing: A Case Report. Otolaryngology Case Reports 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom, S.S.; Torres-Saavedra, P.; Caudell, J.J.; Waldron, J.N.; Gillison, M.L.; Xia, P.; Truong, M.T.; Kong, C.; Jordan, R.; Subramaniam, R.M.; et al. Reduced-Dose Radiation Therapy for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Carcinoma (NRG Oncology HN002). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021, 39, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, S.; Shibata, H.; Adkins, D.; Uppaluri, R. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Strategies in HPV-Related Head-and-Neck Cancer. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2022, 10, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-M.; Wu, M.; Han, F.-Y.; Sun, Y.-M.; Yang, J.-Q.; Liu, H.-X. Role of HPV Status and PD-L1 Expression in Prognosis of Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2021, 14, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allegra, E.; Bianco, M.R.; Mignogna, C.; Caltabiano, R.; Grasso, M.; Puzzo, L. Role of P16 Expression in the Prognosis of Patients With Laryngeal Cancer: A Single Retrospective Analysis. Cancer Control 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.E.; Bilger, A.; Rademacher, J.; Lambert, P.F.; Thibeault, S.L. Preclinical Models of Laryngeal Papillomavirus Infection: A Scoping Review. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 3256–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.; Lin, L.; Huang, Q.; Hu, C.; Zhang, M. HPV16 Status Might Correlate to Increasing Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Hypopharyngeal Cancer. Acta Otolaryngol 2023, 143, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbure, N.; Handorf, E.; Ridge, J.A.; Bauman, J.; Liu, J.C.; Giri, A.; Galloway, T.J. Prognostic Significance of Human Papillomavirus Status and Treatment Modality in Hypopharyngeal Cancer. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3042–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, E.J.; Oliver, J.R.; Jacobson, A.S.; Li, Z.; Hu, K.S.; Tam, M.; Vaezi, A.; Morris, L.G.T.; Givi, B. Human Papillomavirus in Patients With Hypopharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (United States) 2022, 166, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebsgaard, M.; Eriksen, P.; Ramberg, I.; von Buchwald, C. Human Papillomavirus in Sinonasal Malignancies. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2023, 11, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstedt, S.; von Buchwald, C.; Agander, T.K.; Aanaes, K. Impact of Human Papillomavirus in Sinonasal Cancer—a Systematic Review. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2021, 60, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi-Saab, T.; Lozar, T.; Chen, Y.; Tannenbaum, A.P.; Geye, H.; Yu, M.; Weisman, P.; Harari, P.M.; Kimple, R.J.; Lambert, P.F.; et al. Morphologic Spectrum of HPV-Associated Sinonasal Carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.Y.; Hirayama, S.; Goss, D.; Zhao, Y.; Faden, D.L. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oral Oncol 2024, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naegele, S.; Efthymiou, V.; Das, D.; Sadow, P.M.; Richmon, J.D.; Iafrate, A.J.; Faden, D.L. Detection and Monitoring of Circulating Tumor HPV DNA in HPV-Associated Sinonasal and Nasopharyngeal Cancers. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2023, 149, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.H.; Yang, T.H.; Cheng, Y.F.; Chen, C.S.; Lin, H.C. Association of Nasopharynx Cancer with Human Papillomavirus Infections. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, S.; Walburn, T.; Tasoulas, J.; Patel, S.; Agarwal, A.; Gulley, M.L. Plasma Circulating HPV DNA Surveillance in a Patient With Nasopharyngeal Cancer. Ear Nose Throat J 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.H.; Yang, T.H.; Lee, H.C.; Lin, H.C.; Chen, C.S. Association of Salivary Gland Cancer with Human Papillomavirus Infections. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, F.E.; Aldayem, L.N.; Hemaida, M.A.; Siddig, O.; Osman, Z.H.; Shafig, I.R.; Salih, M.A.M.; Muneer, M.S.; Hassan, R.; Ahmed, E.S.; et al. Molecular Detection of Human Papillomavirus-16 among Sudanese Patients Diagnosed with Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Salivary Gland Carcinoma. BMC Res Notes 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costin, C.A.; Chifu, M.B.; Pricope, D.L.; Grigoraş, A.; Balan, R.A.; Amălinei, C. Are HPV Oncogenic Viruses Involved in Salivary Glands Tumorigen(esis? Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2024, 65, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).