1. Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a heterogeneous group of tumors that arise from the squamous cell epithelium of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx [

1,

2]. There are an estimated 890,000 new cases and 450,000 deaths worldwide each year [

3,

4]. The incidence of HNSCC is expected to increase by 30% by 2030 globally, that is, 1.08 million new cases annually [

5]. In addition to well known risk factors such as alcoholic beverages and tobacco products, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) as etiological factor is increasingly contributing to the initiation and development of HNSCC. Importantly, HPV-attributable HNSCCs continue to rise in many countries [

4]. Among the HPV subtypes, HPV 16 is responsible for up to 90-95% of HPV DNA-positive (HPV DNA⁺) HNSCC [

6], which presents different clinicopathological features, such as better susceptibility for chemoradiation and more favorable outcomes, compared to the HPV DNA-negative (HPV DNA⁻) malignancies [

5,

6,

7].

Testing for presence of hrHPV DNA through polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques has facilitated diagnosis of HPV-associated cancers. However, HPV DNA-positivity alone is not a sufficient proof that the cancer is actually driven by HPV, as the virus could be present in a transcriptionally silent state. Therefore, HPV mRNA pattern analysis was reported more meaningful and reliable to identify HPV-driven cancers [

8,

9]. During truly HPV-driven carcinogenesis, the viral oncogene E7 is continuously expressed in a transcriptionally active HPV infection, leading to upregulation of p16ᴵᴺᴷ⁴ᵃ mRNA and subsequent overexpression of p16 protein, detectable by immunohistochemistry staining (referred to herein as p16 IHC). Thus, p16 IHC has been suggested as a surrogate for HPV status in TNM-8 system [

10]. However, discordant patterns, including HPV DNA-positive but p16 IHC-negative (indicated as

HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁻) and HPV DNA-negative but p16 IHC-positive (indicated as

HPV DNA⁻/p16 IHC⁺)

cases have also been found in HNSCC [

11,

12]. Patients with discordant patterns have a worse prognosis with a lower 5-year overall survival (OS) rate compared to patients with both HPV DNA⁺ and p16 IHC⁺ (indicated as

HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁺) [

5,

13,

14]. The underlying causes of these discordances remain unclear, particularly whether p16 IHC-negativity in HPV DNA⁺ cases result from transcriptionally silent HPV infection and lack of E7 transcripts, or whether the positivity of p16 IHC in the HPV DNA⁻ cases is induced by a non-HPV-dependent pathway. Therefore, p16 IHC-positivity is not a perfect surrogate for HPV etiological diagnosis. Combination of HPV DNA testing and p16 IHC might still overestimate the carcinogenic role of HPV in some cases, as transcriptionally silent HPV infection is not necessarily related to carcinogenesis [

5]. In the current clinical practice, patients who test HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁻ or HPV DNA⁻/p16 IHC⁺, are receiving the same standard treatment as those with HPV-driven tumors. Some clinical trials are exploring the benefit of de-escalation of treatment in patients with HPV-positive cancer [

15,

16]. Misclassification of truly HPV-driven and pseudo-HPV-driven HNSCC due to discordant HPV DNA and p16 IHC patterns could thus lead to an undertreatment and adverse consequences. Therefore, it is urgent to advocate for accurate identification of truly HPV-driven HNSCC interpret clinical data correctly and before deciding the therapeutic strategy or predicting prognosis.

In response to the urgent need to precisely characterize the etiological role of HPV in HNSCC, we propose to elucidate true HPV-driven carcinogenesis by a comprehensive approach of molecular expression profiling. In this study, we describe the application of the novel QuantiGene-Molecular-Profiling-Histology (QG-MPH) assay, which quantifies mRNA expression by multiplexed measurement of 18 individual HPV oncogene E7 plus HPV 16 E6, p16ᴵᴺᴷ⁴ᵃ (referred to herein as p16), and other cancer-associated cellular biomarkers. The approach aims to improve the etiological diagnosis of HNSCC, evaluating the prognostic value of combining HPV mRNA testing with p16 mRNA and p16 IHC, with potential implication for therapeutic decision and prognostic assessment.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Characteristics

A total of 68 cases with valid HPV DNA and mRNA test results were included in the statistical analysis (

Table 1). The mean age at diagnosis was 60.8 ± 10.1 years. Of these patients, 28 (41.2%) had a healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9), while 25 (36.8%) were classified as overweight. A smoking history were found in 48 (70.6%) patients. The most common tumor sites were the tonsil (n=25, 36.8%), floor of the mouth (n=14, 20.6%), and base of tongue (n=11, 16.2%). Tumor staging, revised according to the AJCC 8th edition guidelines, was distributed as follows: Stage I (n=16, 23.5%), Stage II (n=26, 38.2%), Stage III (n=12, 17.6%) and Stage IV (n=14, 20.6%). Tumor differentiation of specimen from the initial surgery was diagnosed: Grade II (n=33, 48.5%) and Grade III (n=33, 48.5%), and only two (2.9%) cases were Grade I. These patients had neither prior HPV testing nor p16 IHC when diagnosed.

2.2. HPV Prevalence by HPV DNA and mRNA Status

The HPV prevalence by HPV DNA and mRNA status is summarized in

Table 2. Generally, out of 68 cases, 37 (54.4%) tested hrHPV DNA⁺, including 34 (50.0%) HPV16 DNA⁺ cases. The majority was single HPV infection (n=32) with two cases showing multiple infections (HPV16⁺/18⁺ or HPV16⁺/35⁺). There were a few other hrHPV infected cases detected: two HPV33⁺cases, and one HPV18⁺/82⁺ case. The QuantiGene Molecular-Profiling-Histology (QG-MPH) assay detected positive hrHPV E7 mRNA expression (hrHPV E7 mRNA⁺) in 26 (38.2%) cases, with 24 (35.3%) specifically positive for HPV16 (HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺). Additionally, HPV18 E7 mRNA⁺ and HPV33 E7 mRNA⁺ were found (one case each). The concordance between HPV DNA and mRNA status were calculated. 70.1% (26/37) of hrHPV DNA⁺ cases were hrHPV mRNA⁺. For HPV16 specifically, 70.5% (24/34) of HPV16 DNA⁺ cases were also HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺. The proportion of HPV positivity was higher in male patients (n=47, 69.1%) than in female (n=21, 30.9%). The HPV⁺ cases in male patients were 27 (39.7%) tested hrHPV DNA⁺, while 25 (36.8%) were HPV16 DNA⁺. In contrast, only 10 (14.7%) female patients were hrHPV DNA⁺, with 9 (13.2%) being HPV16 DNA⁺. For hrHPV E7 mRNA positivity, 18 (26.5%) males and 9 (11.8%) females were positive, with similar proportion (88.9% each) for HPV16 E7 mRNA positivity (16 males, 8 females). Unsurprisingly, the prevalence of HPV infection varied by anatomical sites. The positivity of hrHPV DNA was notably higher in OPSCC compared to non-OPSCC (38.2%, 26/65 vs. 16.2%, 11/65). Among OPSCC, 96.2% (25 out of 26) of hrHPV DNA⁺ OPSCC cases were also hrHPV E7 mRNA⁺, with 92.3% (24 out of 36) being HPV16 DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁺. In contrast, non-OPSCC cases had a lower hrHPV DNA positivity (n=11, 16.2%) with only one case (1.5%) being hrHPV E7mRNA⁺, which was also HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺.

2.3. Discrepancies of HPV DNA and mRNA Testing

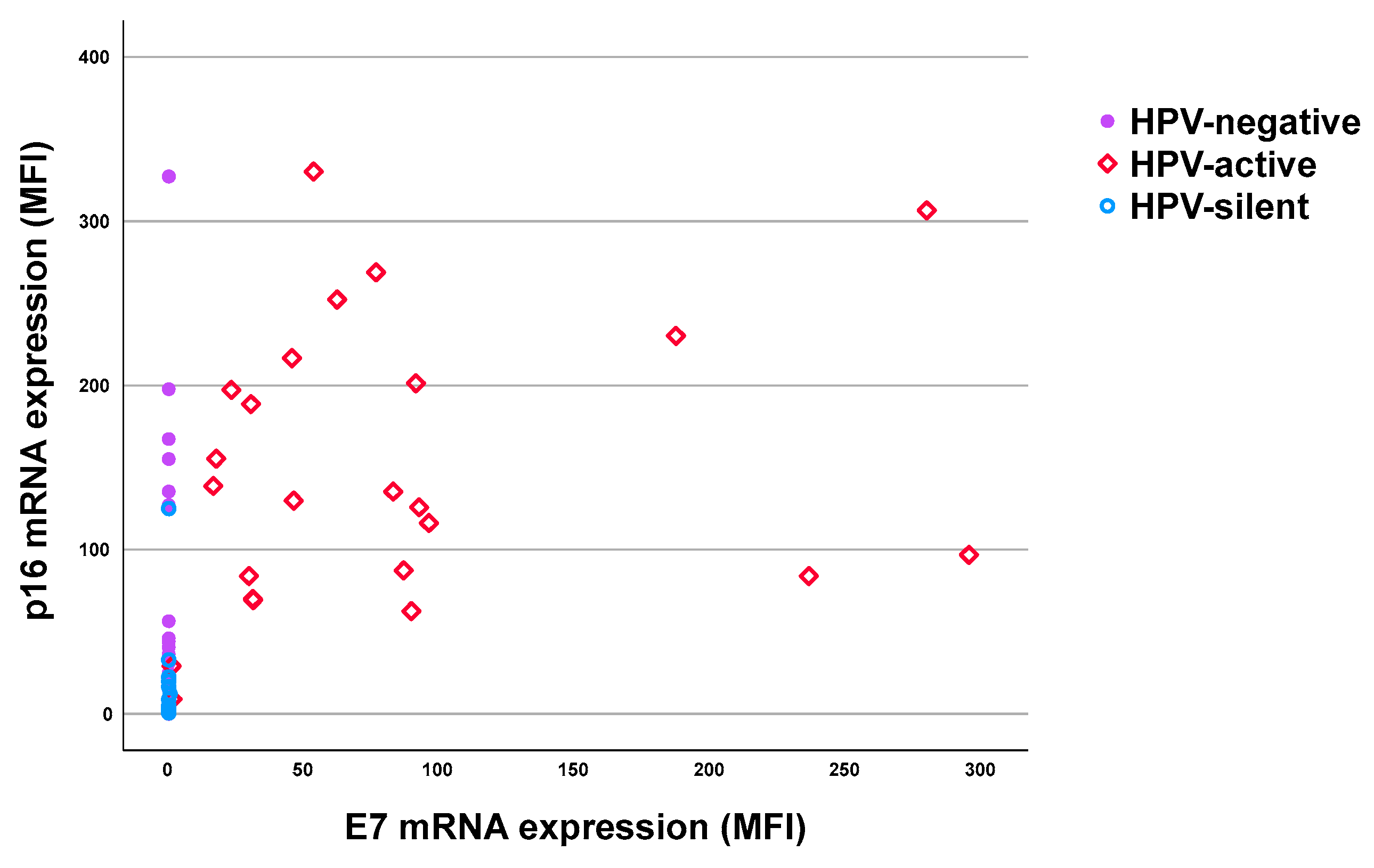

The differences in HPV molecular diagnosis when comparing DNA and mRNA testing are highlighted in

Table 3. Consistently, 23 cases were both hrHPV DNA⁺ and mRNA⁺ (hrHPV DNA⁺/mRNA⁺). Interestingly, three cases showed DNA negativity but with E7 mRNA transcription detectable (hrHPV DNA⁻/mRNA⁺). Together, 26 cases were classified as patients with transcriptionally active hrHPV infection based on hrHPV E7 mRNA⁺ (red squares,

Figure 1). Additionally, 14 (25.6%) cases were positive for hrHPV DNA but negative for E7 mRNA, indicating the presence of HPV infection but classified as transcriptionally silent (hrHPV DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁻, blue circles,

Figure 1) according to the methodology. At last, 28 (41.1%) cases were negative for both hrHPV DNA and E7 mRNA (purple dots,

Figure 1), and classified as HPV-negative tumors.

HPV16 infection was the dominated type among the analyzed HNSCC cases, with 91.9% (34/37) of hrHPV DNA⁺ and 92.3% (24/26) of hrHPV E7 mRNA⁺ being linked to HPV16 in the study. Out of the total, 34 (52.3%) were HPV16 DNA⁺, and HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺ was observed in 24 (36.9%) cases, classified as transcriptionally active HPV16 infections. Among the 34 HPV16 DNA⁺ cases, 13 (38.3%) were E7 mRNA⁻ cases, showing discrepancies in HPV status between Multiplexed Papillomavirus Genotyping (MPG) and QG-MPH measurement and classified as transcriptionally silent HPV16 infections (HPV16 DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁻). 28 cases (43.1%) were negative for both HPV16 DNA and E7 mRNA, and thus classified as HPV16 unrelated etiology.

2.4. Comparison of p16 mRNA and p16 Protein Expression with HPV Status

To better understand the etiological role of HPV in HNSCC, an in-depth analysis of p16 mRNA and p16 protein expression was conducted in the HPV16 related cases (n =65). The results were stratified based on HPV DNA and mRNA status.

2.4.1. Correlation of p16 mRNA Expression with HPV16 DNA and E7 mRNA Status

The E7 mRNA⁺ group showed the highest mean MFI of p16 mRNA expression at 132.6 (range 8.9-330.1,

Table 4), regardless of HPV DNA status. The distribution is shown by red dots in

Figure 2. In the DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁻ group, the mean MFI of p16 mRNA was lower at 9.0 (range 0.57-125.1), whereas in the DNA⁻/E7 mRNA⁻ group, the mean MFI value of p16 mRNA was 16.8 (range 0-327.2). Notably, the p16 mRNA expression was significantly higher in the E7 mRNA⁺ group compared to both the DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁻ group (

p < 0.001) and the DNA⁻/E7 mRNA⁻ group (

p < 0.001). Another finding was that the p16 mRNA expression was also lower in the DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁻ group than that of the DNA⁻/E7 mRNA⁻ group (

p = 0.050), which might be due to HPV-independent pathway affecting the DNA⁻/E7 mRNA⁻ cases.

2.4.2. Correlation Between p16 Protein Expression and HPV16 DNA and E7 mRNA Status

The correlation between p16 protein expression and HPV16 status is summarized in

Table 5. As defined, 79.2 % cases (19/24 HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺) presented p16 IHC⁺, while 55.9 % cases (19/34 HPV16 DNA⁺) presented p16 IHC⁺, indicating better concordance between overexpressed p16 protein and HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺ status compared to that between p16 protein and HPV16 DNA⁺ status.

When relating the p16 IHC negativity to HPV status, the majority of p16 IHC⁻ cases were found in groups without transcriptionally active HPV infection. In summary, 37 out of 41 HPV mRNA⁻ cases (90.2%) were p16 IHC⁻, while 28 out of 31 HPV DNA⁻ cases (90.3%) were p16 IHC⁻. Noteworthy, in the HPV16 DNA⁺/mRNA⁻ group, 12 out of 13 cases (92.2%) were p16 IHC⁻, plus one p16 IHC-invalid case. The results also showed that 28 HPV DNA⁻ cases were correctly interpreted as p16 IHC⁻, while 37 HPV mRNA⁻ cases were p16 IHC⁻, highlighting that p16 protein expression was more closely associated with transcriptionally active HPV (as indicated by E7 mRNA status) than with HPV DNA testing alone. The concordance between HPV mRNA and p16 IHC was higher than that between HPV DNA and p16 IHC.

2.5. Impact of HPV Status and p16 IHC Status on Prognosis

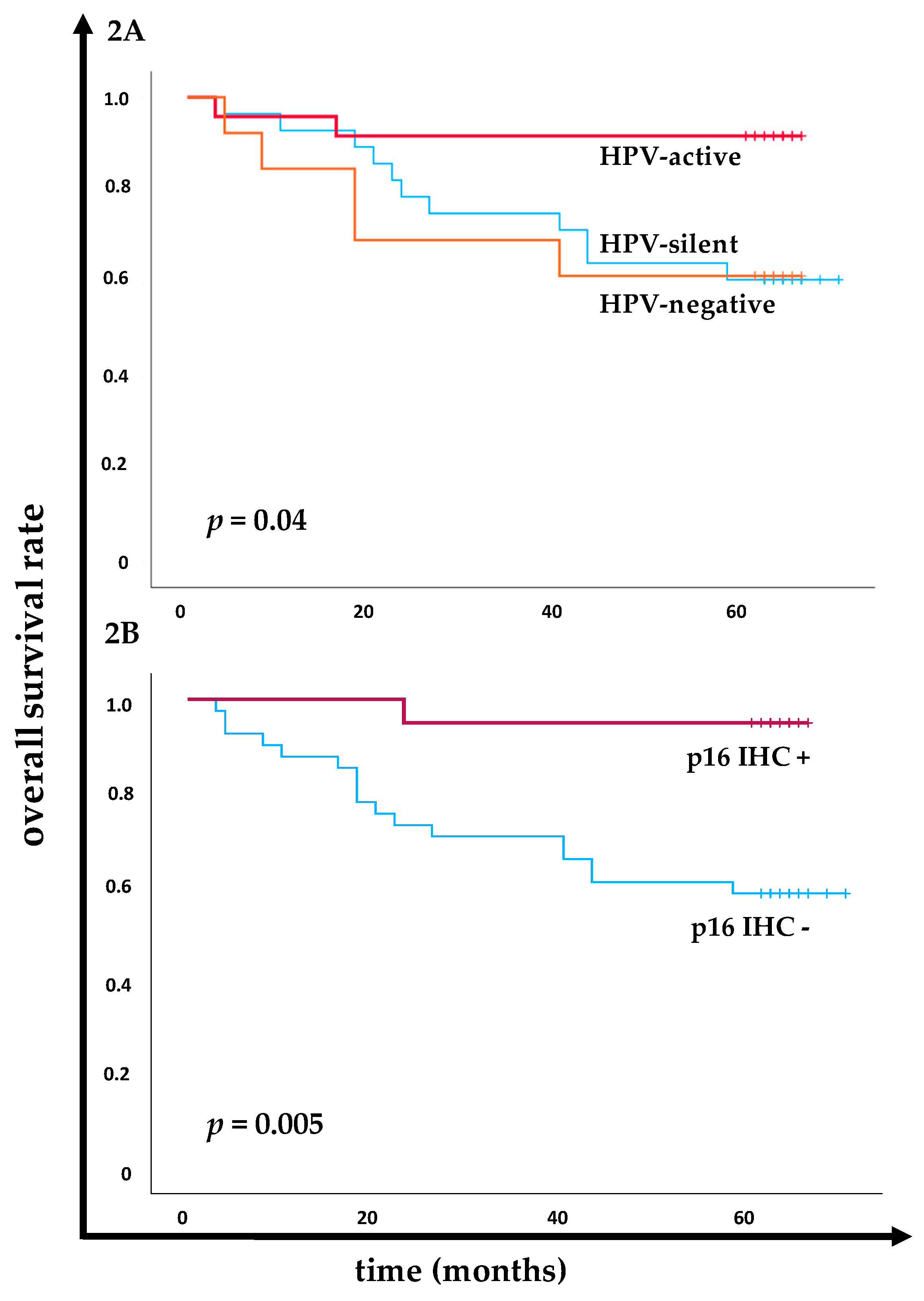

The prognostic impact of HPV DNA and E7 mRNA status and p16 IHC were investigated, particularly focusing on the transcriptional activity of the HPV, as indicated by E7 mRNA expression, and the corresponding survival disparities (

Figure 2). Significantly better overall survival (OS) rate was demonstrated in the transcriptionally active HPV infected (E7 mRNA⁺) group compared to those with transcriptionally silent or HPV-negative (DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁻ and DNA⁻/E7 mRNA⁻) cancers (

p = 0.04 at Log-Rank,

Figure 2A). Specifically, 91.7% (22/24) of patients in the E7 mRNA⁺ group were still alive at the last 5-year follow-up. In contrast, OS rate was lower in the transcriptional silent group (61.5%, 8/13) and the HPV-negative group (60.7%, 17/28), indicating similarity in poorer outcome between the latter two groups.

As expected, p16 IHC⁺ was closely associated with significant better prognosis compared to p16 IHC⁻ (

p = 0.005 at Log-Rank,

Figure 2B). At the 5-year follow-up, 95.0% (19/20) of patients with p16 IHC⁺ were alive, compared to only 58.5% (24/41) of those with p16 IHC⁻.

Additionally, the correlation between p16 mRNA expression and p16 IHC status was analyzed (supplementary

Figure S1). The p16 mRNA expression was significantly higher in the p16 IHC⁺ group (mean MFI 127.8, range 31.0 - 330.1) as compared to the p16 IHC⁻ group (mean MFI 12.2, range 0.6 - 327.2). Interestingly, 19.5% (8/41) of the p16 IHC⁻ cases showed notably elevated p16 mRNA expression, ranging from 125.1 to 327.2. These outliers with increased p16 mRNA expression survived for more than 5 years, suggesting that elevated p16 mRNA expression might be indicative for a better prognosis, even in the absence of detectable p16 protein by IHC.

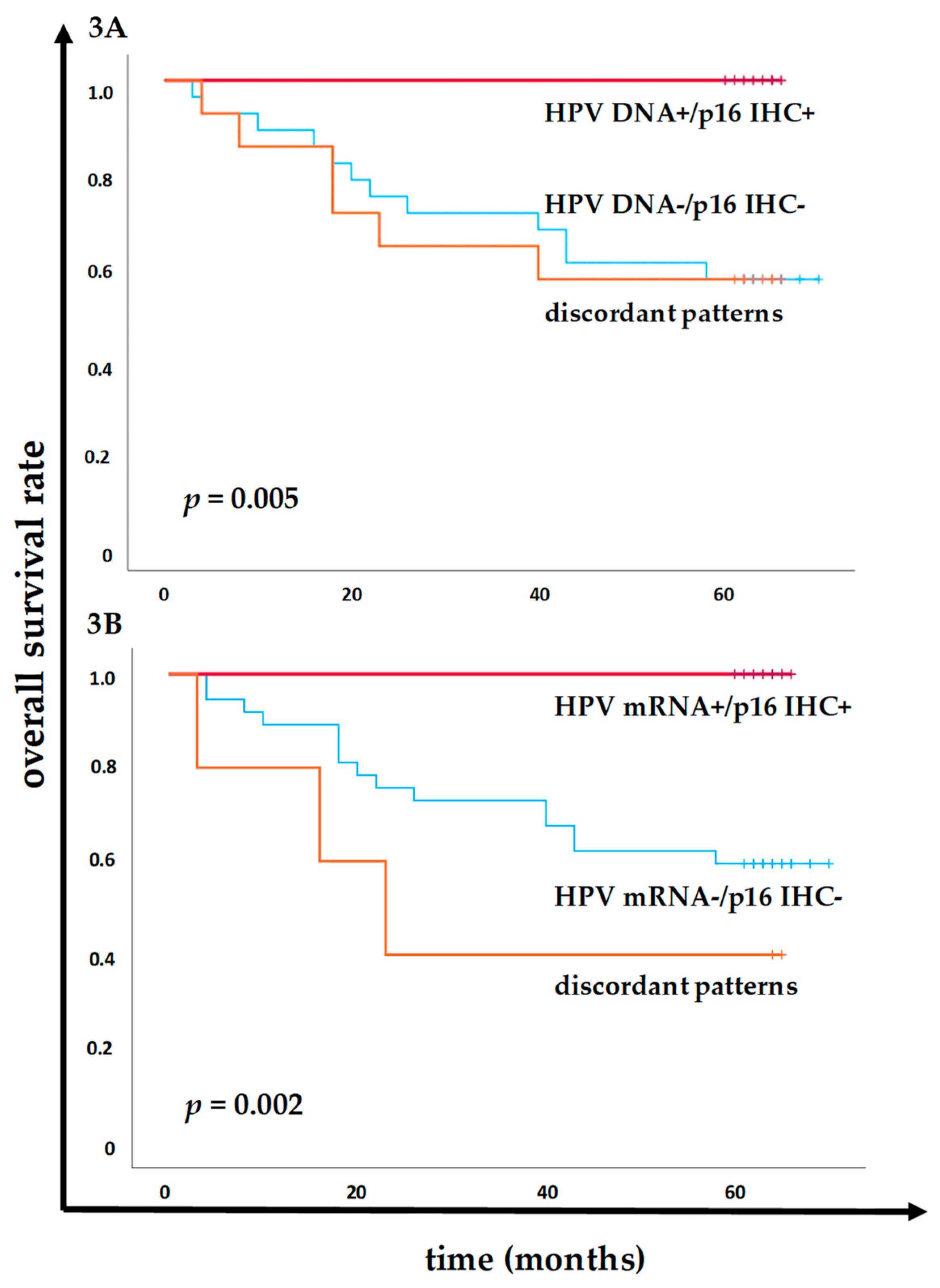

The prognostic implications of combined HPV DNA or HPV mRNA status with p16 IHC was analyzed, refining the ability to predict patient outcomes. Patients who tested both HPV DNA⁺ and p16 IHC⁺ had a significantly better OS rate compared to those HPV DNA⁻ and p16 IHC⁻ (

Figure 3A). Remarkably, 100% (19/19) of patients in the HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁺ group were alive at the 5-year follow-up, whereas only 57.1% (16/28) of the HPV DNA⁻/p16 IHC⁻ group survived (

p = 0.005 at Log-Rank). In addition, 100% (19/19) of patients in the HPV mRNA⁺/p16 IHC⁺ group survived the 5-year follow-up, compared to 59.5% (22/37) of those in the HPV mRNA⁻/p16 IHC⁻ group (

p = 0.001 at Log-Rank,

Figure 3B). Further, the results also identified that patients with discordant expression patterns, either between HPV DNA status and p16 IHC status, or between HPV mRNA and p16 IHC status, had worse outcomes. Specifically, the OS rate was 57.1% (8/14) in the group with discordant HPV DNA and p16 IHC results, compared to 40% (3/5) in the group with discordant HPV E7 mRNA and p16 IHC results, indicating the prognostic disadvantage for patients with discordant categories and the advantages for incorporating the molecular mRNA profiling by QG-MPH to p16 IHC in making therapeutic decision and predicting patient outcomes in HNSCC.

3. Discussion

The susceptibility of HNSCC to chemoradiation therapy significantly varies based on its etiology, which in turn, is affecting the prognosis for a patient. A subset of HNSCCs is associated with HPV, and a more favorable prognosis of HPV⁺ patients was observed compared with those harboring HPV⁻ malignancies [

17]. Traditionally, HPV infection is tested through HPV DNA, and p16 overexpression has been suggested as a surrogate marker for HPV status in the TNM-8 system [

10,

17]. However, exceptions exist, where there is either p16 diffuse overexpression without detectable HPV DNA or HPV DNA positivity without corresponding p16 overexpression (HPV DNA⁻/p16 IHC⁺ or HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁻, respectively). Both cases were associated worse outcomes [

5,

13]. This highlights the limitations of relying solely on HPV DNA testing alone or in combination with p16 IHC to identify true HPV etiology, where transcriptionally active HPV oncogene expression is a necessary activity of truly HPV-driven HNSCCs [

5]. Accordingly, the findings in our study also underline the limitations of DNA-based assay plus p16 IHC in distinguishing transcriptionally active HPV infections from silent ones, which do not play a true etiological role in the HNSCC carcinogenesis. Our study further pointed out that within the HPV DNA⁺ HNSCC cases, not only the molecular profiles but also patients’ prognosis can differ significantly based on HPV mRNA expression status, again suggesting that precise and accurate etiological identification is required to optimize individual personalized therapeutic strategies.

We here describe the use of the QG-MPH assay to profile HPV oncogene E7 and p16ᴵᴺᴷ⁴ᵃ mRNA expression, enhancing the accuracy of HPV etiological diagnosis. One of the most relevant results of our research was that 54.4% of cases tested hrHPV DNA⁺, while only 38.2% expressed detectable hrHPV E7 mRNA levels

. The discrepancy reveals that HPV DNA detection alone cannot reliably determine whether an HPV infection is transcriptionally active and etiologically significant in HNSCC. By contrast, HPV E7 mRNA profiling using QG-MPH enables more assured molecular diagnosis by distinguishing transcriptionally active from silent HPV infections. Notably, we found that 70.6% (24/34) HPV16 DNA⁺ cases were observed HPV16 E7 mRNA⁺, and categorized as transcriptionally active HPV16 infections. Conversely, 38.3% of HPV16 DNA⁺ cases lacked detectable E7 mRNA, and were categorized as transcriptionally silent HPV16 infections. These findings, particularly the anatomical differences observed, such as higher hrHPV DNA and mRNA positivity among OPSCC compared to non-OPSCC, align with previous reports showing that OPSCC was more strongly correlated with transcriptionally active hrHPV, and primarily HPV16 [

13,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Most non-OPSCC cases were transcriptionally silent, explaining the poorer prognosis of HPV DNA⁺ non-OPSCC [

5,

22].

The oncogenic role of hrHPV in HNSCC is mediated through the viral oncogene expression of E6 and E7. While E6 abrogates p53-induced apoptosis, E7 is responsible for driving the cancer cell into proliferation by binding to the cell-cycle regulator retinoblastoma protein (pRB) and release of the transcription factor E2F. Subsequently, E2F leads to unscheduled cell-cycle progression and causes aberrant compensatory upregulation of p16ᴵᴺᴷ⁴ᵃ [

23,

24]. Consistently, our results demonstrate that transcriptionally active HPV infections (E7 mRNA⁺) induce significant p16 mRNA upregulation, leading to overexpression of p16 protein (p16 IHC⁺). In contrast, most of the HPV DNA-positive but E7 mRNA-negative cases did not show upregulated p16 mRNA expression and overexpression of p16 protein, indicating the presence of transcriptionally silent HPV infection and absence of HPV’s oncogenic activity. Therefore, these HPV DNA⁺/ E7 mRNA⁻ cases should be precisely classified as pseudo-HPV-driven cancers, where hrHPV is like an ‘unresolved bystander’ to the malignancy.

Beyond biological curiosity, accurate molecular diagnosis of truly HPV-driven HNSCC is important for making precise personalized therapeutic decisions and predicting prognosis. We next evaluated the impact of HPV DNA and mRNA detection and/or p16 IHC on prognosis in terms of 5-year OS. In this study, we also explore the prognostic implications of combining HPV mRNA status with p16 IHC

, further refining the ability to predict patient outcomes. Patients with transcriptionally active HPV infections (HPV DNA⁺/E7 mRNA⁺) had significantly higher OS rate compared to those with transcriptionally silent (HPV DNA⁺/E7 mRNA¯) or HPV-negative tumors. Furthermore, we found that the combination of HPV mRNA status with p16 IHC improved the prognosis prediction, with patients in the HPV E7 mRNA⁺/p16 IHC⁺ group showing significantly better outcomes than those in the HPV E7 mRNA⁻/p16 IHC⁻ group. Specifically, the poorest outcomes were observed in patients with discordant HPV DNA and p16 IHC results in the study. The reason for these observations is unknown and will need further investigation. However, it is attractive to argue that these patients may have been misclassified and that future patients with discordant status should be treated more appropriately, avoiding unfavorable outcomes and shorter survival. Besides, OS rates were 57.1% (8/14) in the group with discordant HPV DNA and p16 IHC results, compared to 40% (3/5) in the group with discordant HPV mRNA and p16 IHC results. In previous report, patients with discordant testing patterns (HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁻ or HPV DNA⁻/p16 IHC⁺) had a significantly worse prognosis than patients testing HPV DNA⁺/p16 IHC⁺, which is consistent with our findings [

25]. These discordant patterns of HPV DNA and p16 IHC results in the study by Mehanna et al., highlighted the need for comprehensive molecular profiling. Our findings confirm that the integration of HPV E7 mRNA testing using QG-MPH with p16 mRNA or p16 IHC significantly improves the identification of transcriptionally active HPV-driven tumors, which in turn, provides a more accurate diagnosis and prognosis prediction for HNSCC patients. This approach could potentially refine therapeutic strategies and improve patient outcomes.

A limitation of our study is the use of Formalin-fixed-paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material stored for more than 15 years. The possibility of potential degradation of DNA and mRNA in these FFPE blocks should be considered. Another limitation is sample size by different anatomic sites. However, the corresponding results of etiological classification and the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis provide solid support to the meaningfulness of the data. Fresh tumor tissue samples should be used in the future prospective studies and when actual clinical diagnoses are to be done.

In the present work, a major practical advantage is that the novel QG-MPH assay enables an easy and comprehensive measurement of a broad panel of biomarkers, for example, HPV E7 mRNA of 18 individual genotypes plus p16 mRNA, and additional biomarkers, when necessary, within a single analysis, indicating whether the HPV infection is transcriptionally active. Importantly, QG-MPH assay enhances HPV etiological diagnosis to molecularly distinguish truly HPV-driven HNSCC from truly non-HPV induced malignancies. The potential benefit of the QG-MPH assay is a reduction of misclassification and providing valuable implications for therapeutic decision making and prognosis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Clinical Specimens

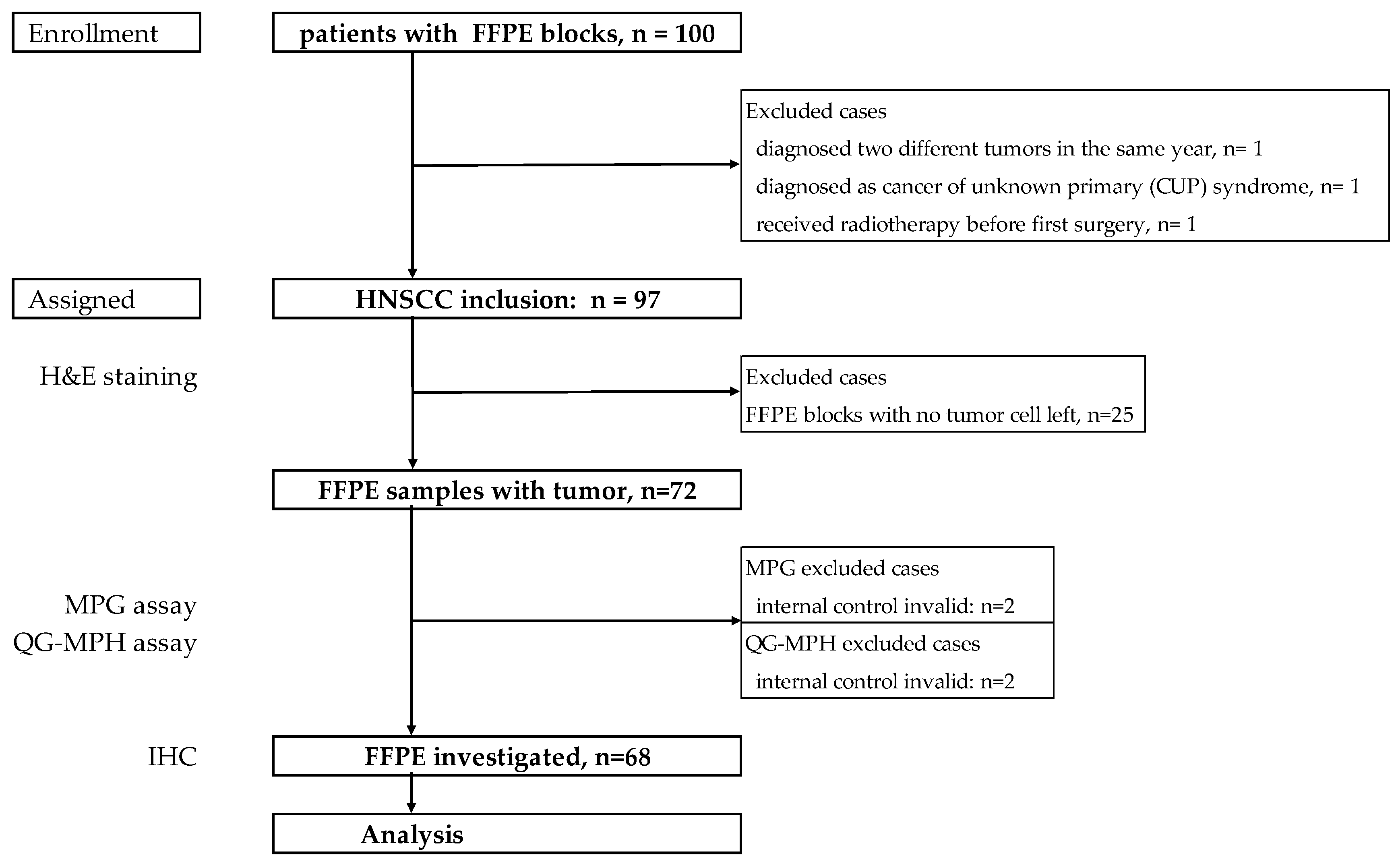

The Institutional Review Board of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany (EA4/035/08) approved the study. Patient’s clinical characteristics including age, gender, clinical and pathological diagnosis were retrieved from medical records. The key eligibility criteria were pathologically confirmed HNSCC at initial diagnosis. FFPE blocks were provided by the pathology department of Ernst von Bergmann Clinic, a Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin-affiliated hospital in Potsdam, Germany. 227 patients diagnosed as HNSCC with clinical data were obtained and analyzed, shown in previous publication 17. For this study, 100 FFPE blocks from those patients were collected and archived between 2001 and 2013 (

Figure 4). Three cases were excluded when censoring the medical history, including one patient who was diagnosed with two different primary tumors, one cancer of unknown primary, and one treated with radiation before salvage surgery.

4.2. Molecular Slicing and Histopathological Evaluation of FFPE Blocks

To exclude carry-over between patients’ materials for molecular analyses, the microtome was thoroughly cleaned by DNA/RNA-ExitusPlus™ (PanReac AppliChem, Germany) between different patient’s FFPE blocks and before the start of molecular sectioning. For each sample, a new disposable blade was used. FFPE blocks of mouse liver were sectioned after cleaning and prior to each patient’s specimen and analyzed for HPV genotypes and human actin-β negativity. Each FFPE block was serially sectioned using a sandwich method. The first and last slides (2-5 μm thickness) were used for histopathological verification after Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. Two pathologists confirmed the presence of tumor cell residues and estimated the percentage of tumor cell area. The blocks with less than 5% area of tumor cells were excluded from the analysis, determined as nonsufficient tumor tissue. Average tumor cell percentage (TCP) area was calculated by the formula below:

In-between, two sets of sections (5-10 μm thickness, 5-10 slices) were collected in DNA/RNAase-free microcentrifuge tubes and tested for HPV DNA and mRNA using MPG and QG-MPH assays, respectively.

4.3. DNA Extraction and Multiplexed Papillomavirus Genotyping Assay

DNA extraction and purification from one set of FFPE sections was done by Maxwell® 16 FFPE Plus LEV DNA purification Kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) according to the standard protocol. HPV genotyping was done and analyzed by MPG assay as described in prior studies 18, 19. The MPG assay has analytical sensitivity to detect 18 hrHPVs (HPV16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82) and 9 low-risk HPVs(HPV6, 11, 42, 43, 54, 57, 70, 72, 90) by amplification of a generic-L1 gene sequence and subsequent genotyping enabled by genotype-specific probes conjugated to Luminex-suspension beads. Negative and positive controls and a human β-globin internal control monitored the sample cellularity, the efficiency of DNA isolation, PCR amplification, hybridization, and genotyping. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of probe signal had to be three-fold higher than the MFI of the background to count as positive. None of the mouse liver control samples tested positive for HPV or human β-globin DNA, confirming the absence of cross-contamination between patients FFPE sections.

4.4. RNA Extraction and QuantiGene-Molecular-Profiling-Histology Assay

RNA was released from FFPE sections (5 μm thickness, 5-10 pieces) using the QuantiGene FFPE Sample Processing Kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the sections were incubated with 200 µL Homogenizing Buffer supplemented with 3.3 µL proteinase K solution (50 µg/µL) in the microfuge tubes for 12-18 hrs at 65°C at 650 rpm in a Thermoshaker. The samples were centrifuged for 5min at 10,000x g (Microfuge, Heraeus) at room temperature. The aqueous lysate containing the desired RNA was collected and transferred to a MultiScreen Filter plate (Merck Millipore, Ireland). The filter plate was then placed on top of another clean 96-well plate, and centrifuged (Multifuge 1S-R, Heraeus) for 5min at 2500 rpm to remove any paraffin residuals. The crude lysate was then ready for downstream QG-MPH assay or stored at -80°C for later use.

The QG-MPH (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) contains a panel of custom oligonucleotides for mRNA capture hybridization and quantification assay based on Luminex suspension bead array multiplexing and branched DNA signal amplification. The QG-MPH diagnostic assay comprises the multiplexed detection of 18 hrHPV (HPV16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82) E7 oncogene mRNA, three spliced HPV16 mRNAs (16E1_4, 16E6*I and 16E1C), and cellular biomarker mRNA (like p16ᴵᴺᴷ⁴ᵃ, Ki67, p53 and others) in a custom Plex-set [

26]. These are informative about the exact HPV genotype-specific mRNA status and the severity of cellular transformation. On each plate three negative control (NC) wells containing plex set and capture-bead mixture plus buffer only and one lysate of the HPV16-positive cervical cancer cell line CaSki as a positive control (PC) were included. ACTB mRNA served as internal control and for normalization to cellularity.

As described previously with some modification [

26], 20 µL of the FFPE extraction lysate was applied to a well of a 96-well hybridization plate and mixed with 15 µL premixture containing the probe-set, capture-beads, blocking reagent and proteinase K, accordingly to the manufacture’s protocol. For capture hybridization of specific target mRNAs, the plate was sealed and incubated for 18-22 hours at 54°C, 600 rpm in a microplate thermostatic shaker (neoLab Migge, Heidelberg, Germany). For signal amplification by branched DNA technology, pre-amplifier, amplifier, biotinylated label probe and Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin (SAPE) were sequentially incubated according to the protocol. MFI was detected by a Bioplex 200 instrument (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and recorded per bead class, i.e. mRNA target.

For HPV genotyping by genotype-specific E7 mRNA, the cutoff was set at the mean of the specific bead class background plus 3x standard deviation (SD) of the NK:

The sample was considered positive when the detected MFI was higher than the cutoff value, accordingly.

For the quantification of relative p16 mRNA expression (referred to herein as p16 mRNA), the MFI value in reaction without sample lysate was determined as p16 NC. The net MFI value of p16 and ACTB were calculated by subtracting the average NC from the raw value, e.g., the net MFI value of p16 was equal to the raw p16 MFI minus the mean p16 MFI of the NC. Further, the MFI of relative p16 mRNA expression that was normalized by ACTB of individual sample was calculated by the formula:

4.5. Immunohistochemistry

FFPE sections of 2-5 μm thickness were stained on a Ventana BenchMark ULTRA (Roche Tissue Diagnostics) using antibodies against p16 (clone E6H4, solution 1:2, Ventana) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Two trained pathologists assessed the p16 IHC. The p16 staining was interpreted as block positivity/diffuse when strong nuclear or strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of a field of tumor cells was identified. The result was marked as failed when there were insufficient tumor cells in the slide and negative when only individual interspersed cells were stained.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and percentages. The MFI was described as median value and range (from Minimum to Maximum value). Statistical analyses compared categorical parameters by the Chi-square or Fishes’ exact tests. The Pearson Chi-Square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare quantitative independent variables, while for nonparametric variables, the Mann-Whitney U tests was used. Length of survival (months) was calculated from the date of first diagnosis to the date of death or last survival follow-up 5 years later; overall survival was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, and significance was evaluated with the Log-Rank tests. P-values were calculated excluding missing values and were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

The innovative QG-MPH assay offers a multiplexed and accurate measurement of the HPV E7 and p16 mRNA in HNSCC specimen and enable more precise differentiation between truly HPV-driven HNSCC and transcriptionally silent, non-etiological HPV infections. Thereby, the assay has the potential to strengthen the accuracy of HPV etiological diagnosis, ultimately leading to better clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Supplementary Figure S1. Correlation of p16 mRNA expression and p16 IHC status in HNSCC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Lili Liang, Andreas Albers and Andreas M. Kaufmann; methodology, Lili Liang, Marla Greve, Eliane Taube and Jonathan Pohl; software, Lili Liang; validation, Lili Liang, Marla Greve and Andreas M. Kaufmann; formal analysis, Lili Liang; resources and clinical data acquiring, Andreas Albers and Stephanie Schmidt; data curation, Lili Liang and Stephanie Schmidt; writing—original draft preparation, Lili Liang; writing—review and editing, Andreas Albers and Andreas M. Kaufmann; visualization, Lili Liang; supervision, Andreas M. Kaufmann; project administration, Andreas Albers and Andreas M. Kaufmann. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany (EA4/035/08).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to AIS e.V. for partially funding financial support to Lili Liang.

Conflicts of Interest

Andreas M. Kaufmann declares that he is named inventor in a patent of Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin concerning the QG-MPH assay (patent no. WO2020/161285A1). Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel: R.L., et al., Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2022. 72(1): p. 7-33.

- de Martel, C., et al., Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer, 2017. 141(4): p. 664-670.

- Johnson, D.E., et al., Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2020. 6(1): p. 92.

- Barsouk, A., et al., Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med Sci (Basel), 2023. 11(2).

- Sabatini, M.E. and S. Chiocca, Human papillomavirus as a driver of head and neck cancers. Br J Cancer, 2020. 122(3): p. 306-314. [CrossRef]

- Watson, M., et al., Using population-based cancer registry data to assess the burden of human papillomavirus-associated cancers in the United States: overview of methods. Cancer, 2008. 113(10 Suppl): p. 2841-54. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.N.D., M. Mierzwa, and N.J. D'Silva, Radiation resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: dire need for an appropriate sensitizer. Oncogene, 2020. 39(18): p. 3638-3649. [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.C., et al., Biological and clinical relevance of transcriptionally active human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer, 2010. 126(8): p. 1882-1894. [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, D., et al., Viral RNA patterns and high viral load reliably define oropharynx carcinomas with active HPV16 involvement. Cancer Res, 2012. 72(19): p. 4993-5003. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H. and B. O’Sullivan, Overview of the 8th Edition TNM Classification for Head and Neck Cancer. Current Treatment Options in Oncology, 2017. 18(7): p. 40. [CrossRef]

- Kofler, B., et al., Sensitivity of tumor surface brushings to detect human papilloma virus DNA in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol, 2017. 67: p. 103-108. [CrossRef]

- Albers, A.E., et al., Meta analysis: HPV and p16 pattern determines survival in patients with HNSCC and identifies potential new biologic subtype. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 16715. [CrossRef]

- Kühn, J.P., et al., HPV Status as Prognostic Biomarker in Head and Neck Cancer-Which Method Fits the Best for Outcome Prediction? Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(18).

- Rietbergen, M.M., et al., Human papillomavirus detection and comorbidity: critical issues in selection of patients with oropharyngeal cancer for treatment De-escalation trials. Ann Oncol, 2013. 24(11): p. 2740-5. [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.E. and C.E. Steuer, HPV as a Carcinomic Driver in Head and Neck Cancer: a De-escalated Future? Curr Treat Options Oncol, 2022. 23(3): p. 325-332.

- Rosenberg, A.J. and E.E. Vokes, Optimizing Treatment De-Escalation in Head and Neck Cancer: Current and Future Perspectives. Oncologist, 2021. 26(1): p. 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Leemans, C.R., P.J.F. Snijders, and R.H. Brakenhoff, The molecular landscape of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2018. 18(5): p. 269-282. [CrossRef]

- Nicolás, I., et al., Prognostic implications of genotyping and p16 immunostaining in HPV-positive tumors of the uterine cervix. Modern Pathology, 2020. 33(1): p. 128-137. [CrossRef]

- Gallus, R., et al., Prevalence of HPV Infection and p16(INK4a) Overexpression in Surgically Treated Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Vaccines (Basel), 2022. 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M., et al., HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2022. 19(5): p. 306-327. [CrossRef]

- Marklund, L., et al., Survival of patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) in relation to TNM 8 - Risk of incorrect downstaging of HPV-mediated non-tonsillar, non-base of tongue carcinomas. Eur J Cancer, 2020. 139: p. 192-200.

- zur Hausen, H., Human papillomaviruses and their possible role in squamous cell carcinomas. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 1977. 78: p. 1-30.

- Pal, A. and R. Kundu, Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: The Cervical Cancer Hallmarks and Targets for Therapy. Front Microbiol, 2019. 10: p. 3116. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M., et al., p16(INK4a) overexpression predicts translational active human papillomavirus infection in tonsillar cancer. Int J Cancer, 2010. 127(7): p. 1595-602. [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, H., et al., Prognostic implications of p16 and HPV discordance in oropharyngeal cancer (HNCIG-EPIC-OPC): a multicentre, multinational, individual patient data analysis. Lancet Oncol, 2023. 24(3): p. 239-251. [CrossRef]

- Skof, A.S., et al., Human Papillomavirus E7 and p16INK4a mRNA Multiplexed Quantification by a QuantiGeneTM Proof-of-Concept Assay Sensitively Detects Infection and Cervical Dysplasia Severity. Diagnostics, 2023. 13(6): p. 1135. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).