1. Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the 16th most common tumor in humans, targeting the tongue, lips, and floor of the mouth. The Global Cancer Observatory estimates that the incidence of OSCC will increase by 40% by 2040 [

1]. Several studies have indicated that the risk of developing oral cancer increases with age, typically affecting individuals older than 50 years, and cases are more common in men [

2,

3]. Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption are primary risk factors, whereas viral infections, particularly involving HPV, have also been suggested as potential contributors. Although HPV infection is a well-established cause of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), its role in oral SCC remains less clear, with lower infection rates observed [

4].

Despite diagnostic and therapeutic innovations, the prognosis of OSCC has not improved with a high recurrence rate and resistance to conventional treatments [

5]. Surgery and Radiotherapy are still the main treatment methods, with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and targeted therapy occasionally used to achieve tumor shrinkage at the same time [

6].

Immunotherapy represents the new frontier of study for individualized therapies against tumors not responding to traditional treatments as well as nanotechnology-based drug delivery [

7], and targeting of the tumor microenvironment (TME). Specifically, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) including pembrolizumab and nivolumab have been Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of recurrent/metastatic HNSCC [

8]. However, although immunotherapy does not provide the same results in patients with similar oncological characteristics and among patients with metastatic HNSCC, only 10% to 18% showed prolonged therapeutic benefit. [

9].

In the personalized medicine era, the mechanisms underlying different responses to similar tumors are investigated [

10]. Many studies have investigated the clinical effects, survival benefits, and adverse reactions of immunotherapy, while the absence of depicting the TME before treatment aroused our interest in conducting further research.

The immune landscape in the tumor microenvironment (TME) can either inhibit or contribute to cancer progression, depending on the type of cell populations present. In HNSCC, the TME exhibits variations according to the anatomical subsite and associated etiological agent [

11]. Primary resistance to immunotherapy may result from a lack of appropriate rejection antigens, deficient immune surveillance, or the presence of immunosuppressive mediators [

12].

From this point of view, a fundamental role seems to be played by the interactions of epithelial neoplastic cells with the various tumor microenvironment (TME) components [

13]. Among these, in addition to immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) originating from various precursor cells (normal fibroblasts, pericytes, smooth muscle cells, epithelial and endothelial cells, quiescent stellate cells, adipocytes, bone marrow-derived MSCs) [

14] are widely represented. There are different types of CAFs, which express different markers correlated with the subtypes, reflecting their functional diversity and varied roles in tumor microenvironment. Among these different subtypes antigen presenting CAFs (apCAFs) are mesothelial cells that acquire fibroblasts characteristics under the influence of IL-1 and TGF-beta and express MHC class II, as Human Leukocyte Antigen – DR Isotype (HLA-DRA) [

15].

HLA-DR is usually expressed on antigen presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells and present peptides antigens of exogenous origin to CD4+ T cells. But unexplainedly, as well as in apCAFs HLA-DR is expressed on other non-APCs tumor cells [

16,

17] such as epithelial laryngeal cancer cells [

18]. Interestingly, it has been noted that non-APC cells HLA-DR expression in TME is correlated with the response to new immune checkpoint regulatory molecules, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 [

19]. PD-L1 is an immune checkpoint inhibitor that binds to PD-1 on T cells, regulating immune responses and preventing autoimmunity. Tumors often exploit this mechanism by overexpressing PD-L1, which helps them evade immune detection and promotes tumor progression by inhibiting cytotoxic T lymphocyte function PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors work by blocking this interaction, thereby enhancing T cell responses and mediating antitumor activity [

20].

PD-L1 is a critical target for cancer immunotherapy in HNSCC. Studies have shown that PD-L1-specific helper T-cells can effectively target and kill tumor cells, suggesting that PD-L1 can be a favourable target for immunotherapy in HNSCC patients. The association of PD-L1 and HLA-DR expression has been observed in a subset of oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma cases, indicating potential for targeted immunotherapy strategies [

21].

To date, only a single study has been reported to isolate epithelial and mesenchymal cell cultures from the same oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patient’s tissue samples [

22]. In this study we analyzed paired epithelial and fibroblasts culture cells derived from normal and tumoral primary tobacco smoking OSCC patients.

We aimed to investigate the de-novo HLA-DR expression in fibroblasts and CAFs culture cells in order to support non apCancer associate fibroblasts role in tobacco smoking-HPV negative oral cancerogenesis. In addition, we evaluated de novo HLA-DR expression in cancer derived epithelial culture cells. Importantly, both cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and normal fibroblasts expressed HLA-DR, with significantly higher levels in CAFs. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [

23] showed increased HLA-DR and PD-L1 expression in HNSCC biopsies compared to normal tissues, and a positive correlation between these two markers in cancer samples. TCGA data provide comprehensive genomic and clinical information that advances cancer research by elucidating tumorigenic mechanisms, enabling biomarker discovery, characterizing shared signalling pathways, and guiding the development of targeted combinatorial therapies.

These findings indicate the tumor microenvironment can modulate HLA-DR expression in non-antigen-presenting cancer cells and CAFs. Further studies are required to better understand the biological effects of HLA-DR+ CAFs and tumor-derived epithelial cells in tobacco-associated, HPV-negative OSCC, including their potential correlation with responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1, as well as the mechanisms and signaling pathways through which HLA-DR+ CAFs and their activity within the TME influence OSCC prognosis.

Additionally, we aim to clarify the prognostic significance of environmentally induced HLA-DR expression in non-antigen-presenting OSCC cells and CAFs, particularly in the context of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor immunotherapy for primary OSCC.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Consideration

Institutional Ethics Committee approval was taken (IC number 3740). All patients who took part in our study provided informed consent. The confidentiality of the documentation of the detailed case history, clinical details, and patient personnel information was maintained.

Patients

Five patients underwent surgery for primary OSCC. The tumor staging was evaluated following the eight edition of TNM Classification [

24]. TNM classification is described in

Table 1. Inclusion criteria: 1) diagnosis of primary oral squamous carcinoma, 2) signing of informed consent for involvement in the study. Exclusion criteria: 1) patients diagnosed with non-primary squamous carcinoma of the head and neck and already undergoing radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy, biological therapy.

To validate our findings and investigate potential correlations and prognostic implications, we utilized data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). TCGA data for head and neck cancer were obtained from:

Expression levels of HLA-DR and PD-L1 were reported in FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million reads mapped), a unit commonly used to quantify gene expression from RNA-seq data.

Primary Cell Cultures

During surgery tumoral and healthy tissue (far at least 3 cm from macroscopic tumor) specimens were sterile collected. The biological material was washed in a Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution with antibiotics and after a mechanical digestion, was incubated with Collagenase IV (0,1% in PBS) solution for 2h at 37° in Petri Dishes. Fibroblasts and epithelial cells were isolated from both biopsies and cultured in two different media. Both Fibroblasts and CAFs were selected at different passages in trypsin-EDTA 0.25% and cultured with DMEM-high glucose (10% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% Penicillin/streptomycin, 1% L-Glutamine). Both normal and cancer epithelial cells were cultured in a specific medium DMEM - high glucose (HAM F12 1:1, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 1% L-Glutamine, Insulin 10ug/ml, Epidermal growth factor 20ng/ml, Hydrocortisone 0.5yg/ml). Cells were expanded in Flask T75 at different passages. Cells were frozen at each different passage using Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) 10% at -80 °C.

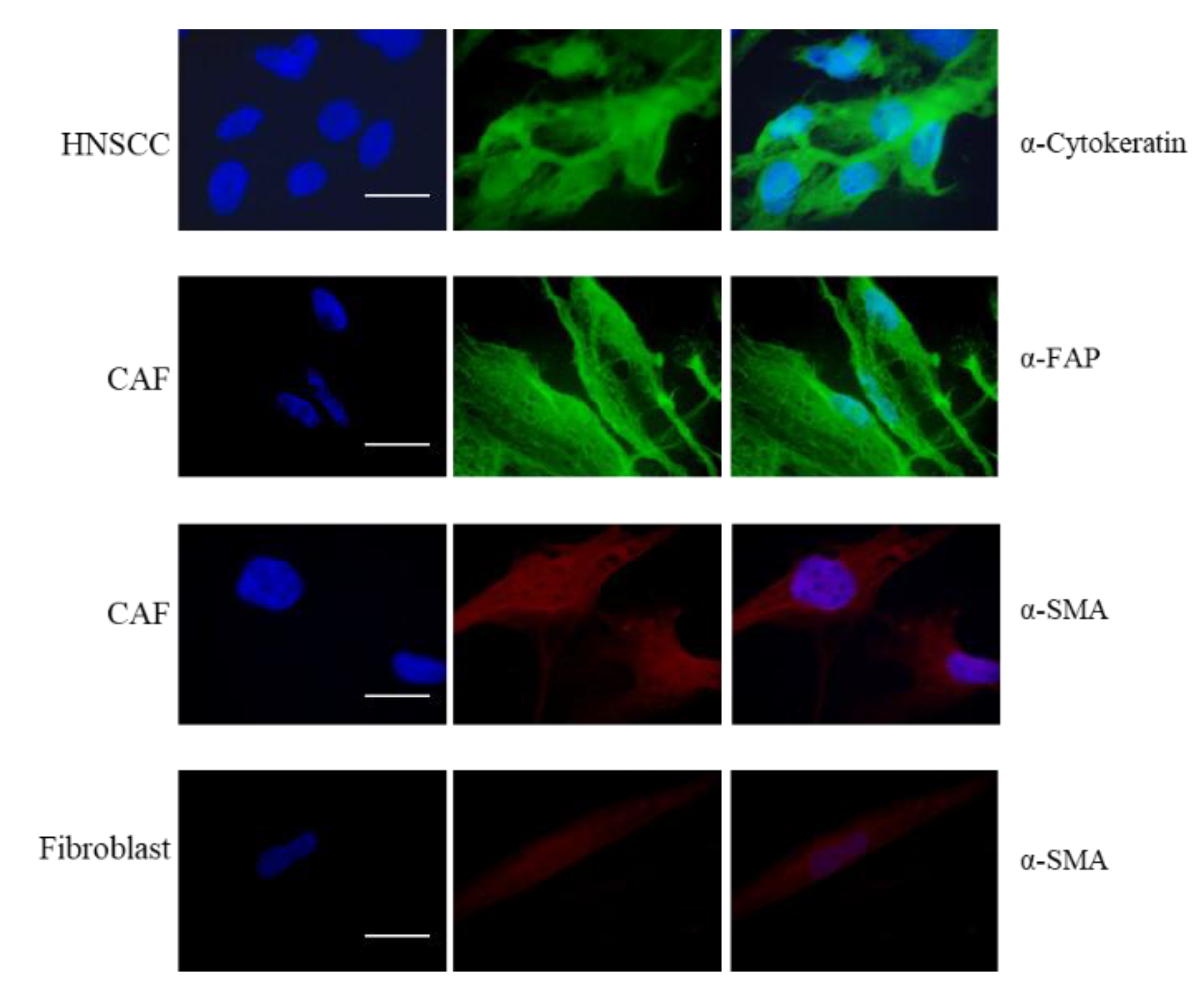

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Expression of α-SMA, marker of fibroblast, FAP, marker of CAFs, and cytokeratin for HNSCC tumor cells was evaluated by immunofluorescence analysis. Briefly, cells were seeded on the 4-well chamber slides (VWR, Germany) with a 30000 cells/well density, were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at RT and permeabilized with triton-X for 10 min. After blocking with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (VWR, Germany) solution for 30 min at RT, 200 µL of a primary antibody solution, anti-fibroblast activation protein (αFAP-rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling), or alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA mouse monoclonal, Cell Signaling) or anti-cytokeratin (mouse monoclonal, Novus Biological) was added and incubated for 2 h in RT. Then, the cells were washed twice with 2% BSA in PBS solution and incubated with secondary antibody solution for 1 h at 37 °C in darkness. All slides were washed twice with 2% BSA in PBS solution and 400 µL of DAPI (SAFSD8417, VWR, Germany) solution was added. Fluorescence staining was photographed using Olympus IX83 microscope (Boston Industries, Inc., MA, USA).

Flow Cytometry – Sorting

Cells were detached with trypsin and then resuspended in PBS-0.5%BSA-1mM EDTA. To perform sorting procedures, cells were marked with anti-CD90 antibody (a CAF-specific marker, 130-110-638 Milteny Biotec) and EpCAM (marker of epithelial/cancer cells, 130-111-002, Milteny Biotec), then the separation of positive cells was performed with a sorter (BD FACSMelody™ Cell Sorter, USA) and collected in PBS-0.5%BSA-1mM EDTA at 4 °C.

Evaluation of HLA-DR Expression

100000 sorted cells were used for each measurement. CAF CD90 positive cells or EpCAM-HNSCC positive cells were incubated for 45 min at 4 °C with 2 µL of HLA-DR antibody (BD Horizon™ BV786 Mouse Anti-Human HLA-DR, 564041, BD Biosceince). After washing with PBS, the percentage of HLA-DR positive cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter). Analysis of the obtained results was performed using CytExpert 2.4.0.28 (Beckman Coulter).

HPV Detection and Genotyping

HPV DNA detection was performed using the HybriSpot HPV Direct Flow Chip kit (Master Diagnostica, Granada, Spain) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. A total of 200-ng DNA were utilized for each reaction. The HybriSpot HPV Direct Flow Chip detects the following high-risk HPV genotypes: 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82.

DNA Detection

Two to four 10-µm unstained sections from the FFPE blocks were collected in nuclease-free microcentrifuge tubes. Established precautions were followed to mitigate the contamination of the sections obtained for total DNA extraction. Following deparaffinization and proteinase K digestion overnight at 56 °C, total DNA was extracted using the Qiagen FFPE extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of the DNA extracted was assessed with a Biodrop µLite spectrophotometer (Biodrop LTD, Cambridge, UK). The absorbance ratios were used as quality indicators as follows: A260nm/A280nm (ca. 1.8 for pure DNA) and A260nm/A230nm (ca. 2.0–2.2 for pure DNA). The DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA Broad Range Assay or Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity kit and a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Lastly, the DNA integrity and functionality were determined by the amplification of a 205 base-pair human β-globin gene fragment, using conventional PCR and gel electrophoresis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize clinical and experimental data. Continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and first-third quartile, as appropriate. Categorical variables were summarized with absolute and percentage frequencies.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank exact test for paired data was used to analyze the presence of HLA-DR in both normal and neoplastic tissues in the experimental samples. TCGA data were used to validate our findings and evaluated via unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, when necessary. In particular, we analyzed relative protein expression levels (CPTAC, Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium) of HLA-DR and PD-L1 in normal and HNSCC specimens. Correlation between HLA-DR and PD-L1 mRNA expression levels in the TCGA cohort was assessed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r).

To evaluate the prognostic value of HLA-DR and PD-L1, survival analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Univariable analyses were first performed to assess the association of HLA-DR and PD-L1 expression with overall survival (OS). Multivariable Cox regression models were then applied, incorporating HLA-DR and PD-L1 expression while adjusting for potential confounders, including age, sex, and disease stage. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and corresponding p-values were reported.

A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7.04 (San Diego, CA, USA) and R software (version 4.4.0, 2024-04-24) for Windows.

3. Results

Clinical features of five patients enrolled in the present study are listed in

Table 1.

HPV detection was negative for all cases. We harvested primary cell cultures from biopsies of all patients obtaining epithelial cancer cells, CAFs and normal fibroblast from healthy tissue (far at least 3 cm from macroscopic tumor). As shown in

Figure 1 the purity of the cell preparation by immunofluorescence staining was confirmed: α-SMA (α smooth muscle actin) was used as fibroblast marker, FAP (fibroblast activating protein) as CAF marker and Cytokeratin as epithelial marker for cancer cells.

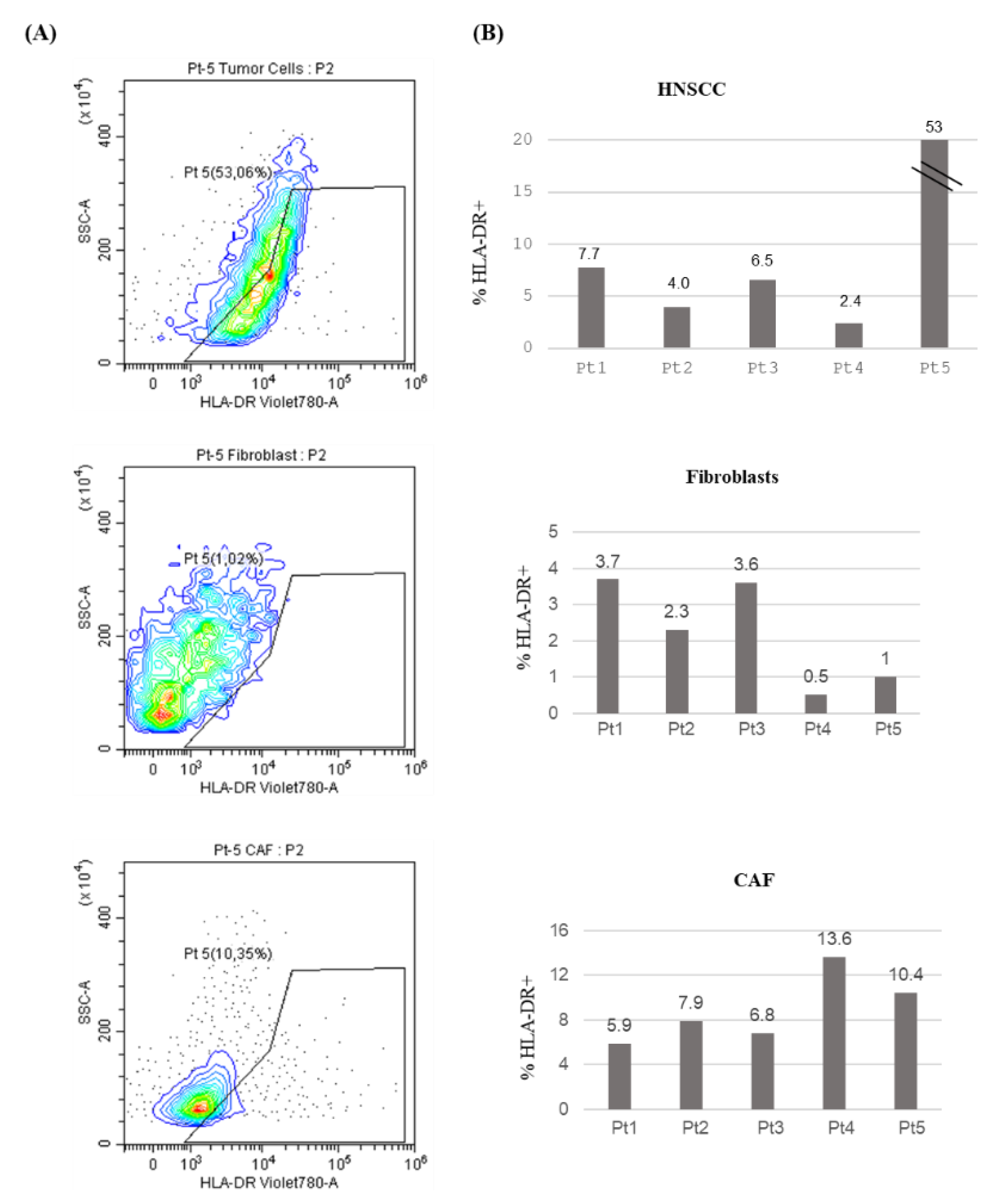

In order to evaluate HLA-DR expression in these primary cultures we performed Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis. HLA-DR levels in tumor cells, as depicted in

Figure 2 (A, B), exhibited a high degree of variability across different patients ranging from 2.4 to 53%. Therefore, the confirmation of our previous finding adopting a different detection method, strengthens the validity of this observation.

To analyze HLA-DR expression in the tumor microenvironment (TME), we compared HLA-DR levels in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and normal fibroblasts (

Figure 2 A, B). The % of positive HLA-DR cells span from 0.5 to 3.7 in normal fibroblast while in CAFs range from 5.9 to 13.6, with no statistically significant difference (P=0.063).

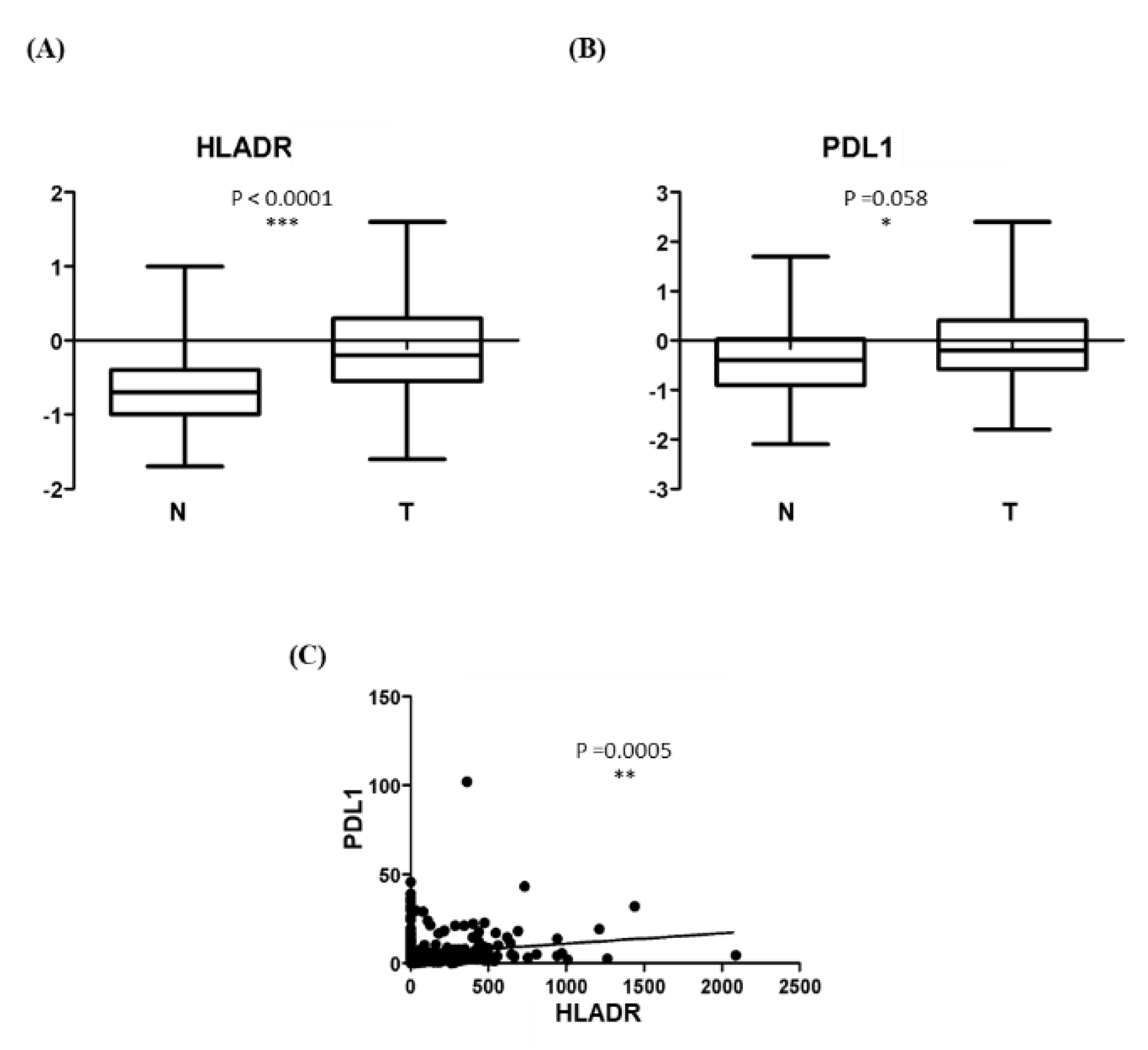

Validation in a larger cohort was performed using TCGA data. As shown in

Figure 3A, HLA-DR protein levels were significantly higher in HNSCC tumor tissues (T = 109; mean = -0.104 ± 0.698) compared with normal tissues (N = 70; mean = -0.599 ± 0.545), with a p between group < 0.0001

Given previous reports of HLA-DR and PD-L1 co-expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, we next assessed PD-L1 protein levels in the same HNSCC dataset. As shown in

Figure 3B, PD-L1 expression was significantly higher in tumor tissues (T = 87; mean = -0.022 ± 0.813) compared with normal tissues (N = 57; mean = -0.386 ± 0821) with a p between group of 0.0098.

Correlation analysis of TCGA data was then performed in 492 HNSCC specimens, whose baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 2. A significant positive correlation was observed between HLA-DR and PD-L1 mRNA expression (r = 0.157, p = 0.0005; Figure 4C).

Finally, we evaluated the prognostic impact of HLA-DR and PD-L1 expression on overall survival (OS) in the TCGA cohort. In univariable Cox proportional hazards models, neither HLA-DR (HR: 0.674; 95% CI: 0.352–1.292; p = 0.235) nor PD-L1 (HR: 0.975; 95% CI: 0.840–1.130; p = 0.733) was significantly associated with OS. Multivariable analyses adjusted for age, sex, and stage yielded consistent results: HLA-DR (HR: 0.613; 95% CI: 0.309–1.216; p = 0.161) and PD-L1 (HR: 1.030; 95% CI: 0.885–1.199; p = 0.700) did not demonstrate prognostic significance.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first in which pairs of epithelial and mesenchymal cell cultures obtained from the same patient are created, representing tissue of tobacco-associated HPV negative OSCC.

Although HPV infection is a well-established cause of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), its role in oral SCC remains less clear, with lower infection rates observed [

4].

HLA-DR levels in tumor epithelial cells exhibit a high degree of variability across different patients ranging from 2.4 to 63%. Here, the confirmation of our previous finding using a different detection method strengthens the validity of this observation [

18].

HLA-DR is an antigen belonging to MHC II which was discovered in the 1980s and was then neglected to the detriment of studies on the PD-1 and PDL-1 antigens of MHC I. Today, great interest is being rediscovered in the expression of HLA-DR due to its possible role as a biomarker of the individual response of patients affected by OSCC to treatments adjuvant surgery. Further studies will be necessary to evaluate which molecular mechanisms induce the expression of HLA-DR in oral cancer and in what way they interfere with tumor growth.

It will be interesting to investigate if HLA-DR expression is different between HPV negative and HPV positive OSCC, as it happens for the reduced MHC Class II expression in HPV negative vs HPV positive oropharyngeal and cervical cancers [

25,

26].

Opposite to oropharyngeal epithelial HLA-DR + HPV + culture cells, in our experience with HPV - culture cells, HLA-DR expression could not be interpretated as a part of the viral immune response where T cells would provoke extensive expression of cytokines including IFNγ, which might sequentially promote the MHC-II expression in HPV+ tumor cells [

16,

27].

A fundamental role in the expression of HLA-DR appears to be played by fibroblastic mesenchymal cells. It therefore appears important to study not only transformed epithelial cells but also mesenchymal cells.

Quite recently, it has been hypothesized that HLA-DR expression may be involved in the modulation of the response to treatment with anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1. In particular, HLA-DR+ correlates with a lower response to treatment with anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1, identifying it as an unfavorable prognostic marker in immunotherapy treatments [

19].

PD-L1 is a crucial target for cancer immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of PD-L1-specific helper T-cells in targeting and killing tumor cells, suggesting PD-L1’s potential as a valuable immunotherapeutic target in HNSCC patients. Co-expression of PD-L1 and HLA-DR has been observed in some oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma cases, opening ways for targeted immunotherapy [

21].

Analysis Atlas database [

23] revealed increased HLA-DR and PD-L1 expression in HNSCC biopsies compared to normal tissues, along with a positive correlation between these two markers in cancer samples.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this research suggest that the tumor microenvironment can modulate HLA-DR expression in both non-antigen-presenting cancer cells and apCAFs. The observed correlation between PD-L1 and HLA-DR offers potential insights for developing targeted immunotherapy strategies in HNSCC. Further research is needed to evaluate the prognostic significance of microenvironment-associated HLA-DR expression in non-antigen-presenting OSCC cells and CAFs, particularly concerning the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor immunotherapy in primary OSCC.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of A. Gemelli University Hospital Foundation (protocol code 3740).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Huang, Z.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Tang, J.; Huang, C. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas: State of the Field and Emerging Directions. Int J Oral Sci 2023, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polz-Gruszka, D.; Morshed, K.; Stec, A.; Polz-Dacewicz, M. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) in Oral and Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in South-Eastern Poland. Infect Agents Cancer 2015, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepan, K.O.; Mazul, A.L.; Larson, J.; Shah, P.; Jackson, R.S.; Pipkorn, P.; Kang, S.Y.; Puram, S.V. Changing Epidemiology of Oral Cavity Cancer in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023, 168, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Bayoumy, K.; Christensen, N.D.; Hu, J.; Viscidi, R.; Stairs, D.B.; Walter, V.; Chen, K.M.; Sun, Y.W.; Muscat, J.E.; JP, R. , Jr An Integrated Approach for Preventing Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancers: Two Etiologies with Distinct and Shared Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Cancer Prev Res 2020, 13, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, R.D.; Yeudall, W.A.; Salo, T. Grand Challenges in Oral Cancers. Front Oral Health 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaidar-Person, O.; Gil, Z.; Billan, S. Precision medicine in head and neck cancer. Drug Resist Updat 2018, 40, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.; Gupta, T.; Rai, A.K.; Pandey, P. Pioneering a New Era in Oral Cancer Treatment with Electrospun Nanofibers: A Comprehensive Insight. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. Published online January 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyford-Pike, S.; Peng, S.; Young, G.D. Evidence for a Role of the PD-1:PD-L1 Pathway in Immune Resistance of HPV-Associated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, U.; Muller, L.; Lechner, A. Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer—Scientific Rationale, Current Treatment Options and Future Directions. Swiss Med Wkly 2018, 148, w14625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, R.; Peltonen, K.; Rannikko, J.H.; Liu, R.; Kumari, A.N.; Nicorici, D.; Lee, M.H.; Mutka, M.; Kovanen, P.E.; Niinikoski, L.; et al. Patient-Derived Tumor Explant Models of Tumor Immune Microenvironment Reveal Distinct and Reproducible Immunotherapy Responses. OncoImmunology 2025, 14, 2466305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partlová, S.; Bouček, J.; Kloudová, K.; Lukešová, E.; Zábrodský, M.; Grega, M.; Fučíková, J.; Truxová, I.; Tachezy, R.; Špíšek, R.; et al. Distinct Patterns of Intratumoral Immune Cell Infiltrates in Patients with HPV-Associated Compared to Non-Virally Induced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e965570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.; Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Desrichard, A.; Havel, J.J.; Dalin, M.G.; Riaz, N.; Lee, K.W.; Ganly, I.; Hakimi, A.A.; Chan, T.A.; et al. The Head and Neck Cancer Immune Landscape and Its Immunotherapeutic Implications. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e89829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, T.; An, Z. Unleashing the Power of Immune Checkpoints: A New Strategy for Enhancing Treg Cells Depletion to Boost Antitumor Immunity. Int Immunopharmacol 2025, 147, 113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Yao, F.; Wu, L.; Xu, T.; Na, J.; Shen, Z.; Liu, X.; Shi, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, Y. Heterogeneity and Interplay: The Multifaceted Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Tumor and Therapeutic Strategies. Clin Transl Oncol 2024, 26, 2395–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elyada, E.; Bolisetty, M.; Laise, P.; Flynn, W.F.; Courtois, E.T.; Burkhart, R.A.; Teinor, J.A.; Belleau, P.; Biffi, G.; Lucito, M.S.; et al. Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Reveals Antigen-Presenting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Discov 2019, 9, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, M.L.; Cook, R.S.; Johnson, D.B.; Balko, J.M. Biological Consequences of MHC-II Expression by Tumor Cells in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. Apr 2019, 25, 2392–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Estrada, M.V.; Salgado, R.; Sanchez, V.; Doxie, D.B.; Opalenik, V., SR; AE, F.; E, J.; AS, G.; AR, S.; et al. Melanoma-Specific MHC-II Expression Represents a Tumour-Autonomous Phenotype and Predicts Response to Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Therapy. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prampolini, C.; Almadori, G.; Bonvissuto, D.; Barba, M.; Giraldi, L.; Boccia, S.; Paludetti, G.; Galli, J.; Parolini, O.; Settimi, S.; et al. Immunohistochemical Detection of “Ex Novo” HLA-DR in Tumor Cells Determines Clinical Outcome in Laryngeal Cancer Patients. HLA 2021, 98, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrane, K.; Le Meur, C.; Besse, B.; Hemon, P.; Le Noac’h, P.; Pradier, O.; Berthou, C.; Abgral, R.; Uguen, A. HLA-DR Expression in Melanoma: From Misleading Therapeutic Target to Potential Immunotherapy Biomarker. Front Immunol 2024, 14, 1285895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, K.; Cross, N.; Jordan-Mahy, N.; Leyland, R. The Extrinsic and Intrinsic Roles of PD-L1 and Its Receptor PD-1: Implications for Immunotherapy Treatment. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 568931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata-Nozaki, Y.; Ohkuri, T.; Ohara, K.; Kumai, T.; Nagata, M.; Harabuchi, S.; Kosaka, A.; Nagato, T.; Ishibashi, K.; Oikawa, K.; et al. PD-L1-Specific Helper T-Cells Exhibit Effective Antitumor Responses: New Strategy of Cancer Immunotherapy Targeting PD-L1 in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Transl Med 2019, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, N.; Gangadharan, C.; Pillai, V.; Kuriakose, M.A.; Suresh, A.; Das, M. Establishment and Characterization of Novel Autologous Pair Cell Lines from Two Indian Non Habitual Tongue Carcinoma Patients. Oncol Rep 2022, 48, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlen, M.; Zhang, C.; Lee, S.; Sjöstedt, E.; Fagerberg, L.; Bidkhori, G.; Benfeitas, R.; Arif, M.; Liu, Z.; Edfors, F.; et al. A Pathology Atlas of the Human Cancer Transcriptome. 2017, 357, eaan2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brierley, J.D. MKGE, Christian Wittekind. In TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours; 2016.

- Yan, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Q.; Du, M.; Li, Y.; He, S.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Bei, J.; Chen, S.; et al. Deciphering the Interplay of HPV Infection, MHC-II Expression, and CXCL13+ CD4+ T Cell Activation in Oropharyngeal Cancer: Implications for Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2024, 73, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.M.; Salnikov, M.; Tessier, T.M.; Mymryk, J.S. Reduced MHC Class I and II Expression in HPV-Negative vs. HPV-Positive Cervical Cancers. Cells 2022, 11, 3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseddine, A.A.; Burman, B.; Lee, N.Y.; Zamarin, D.; Riaz, N. Tumor Immunity and Immunotherapy for HPV-Related Cancers. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 1896–1912. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).