Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

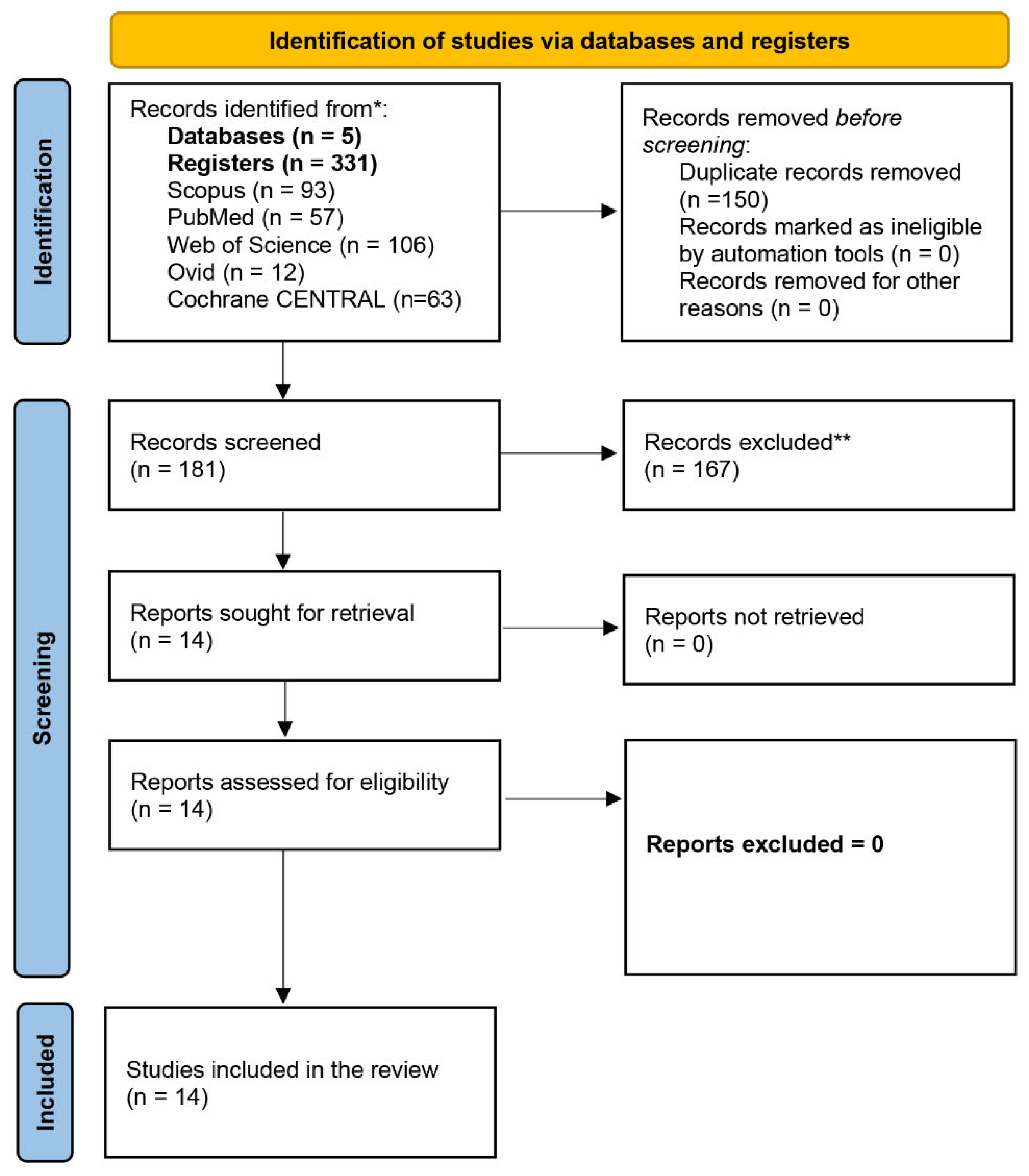

Literature Search and Selection

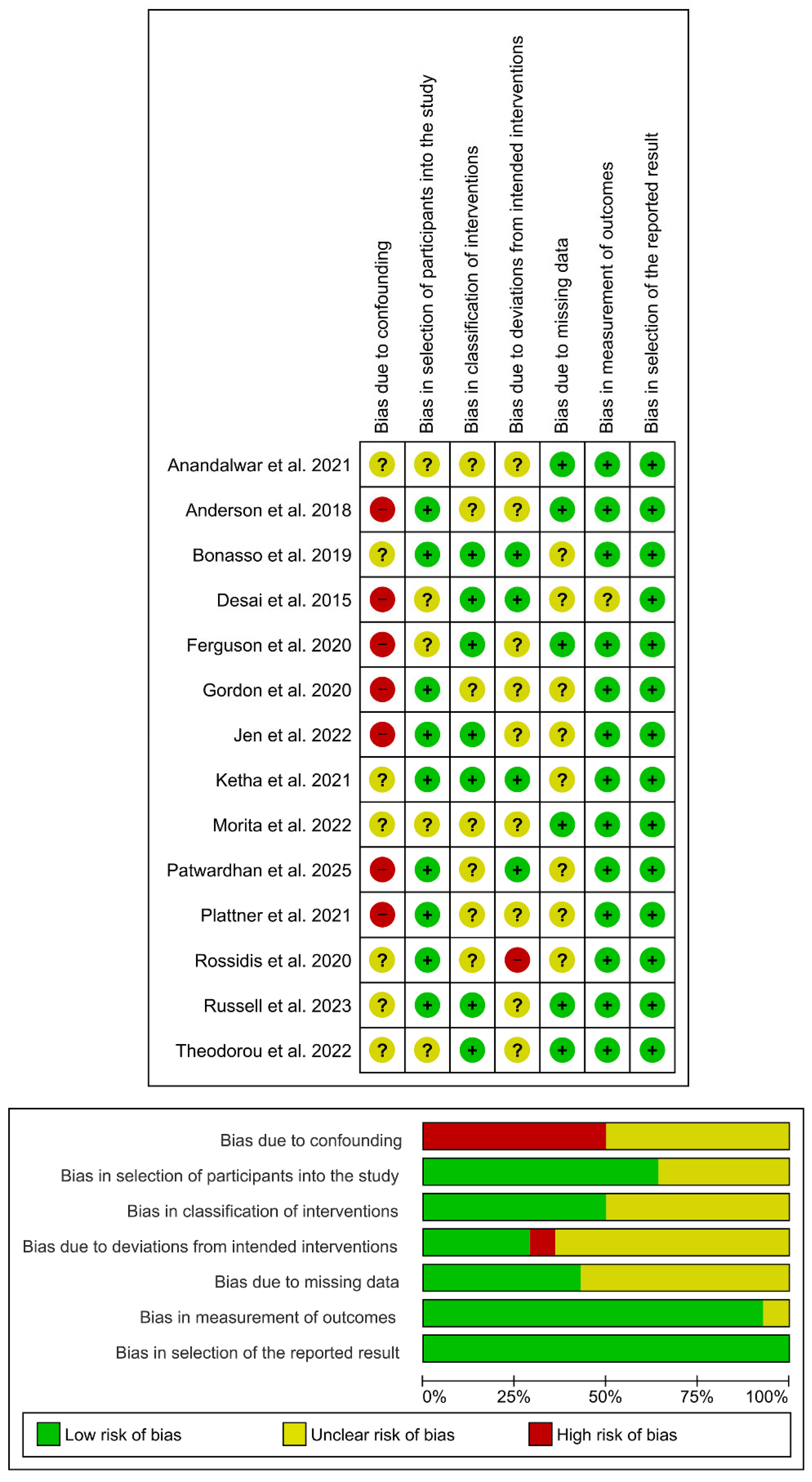

Quality Assessment

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Meta-Analysis

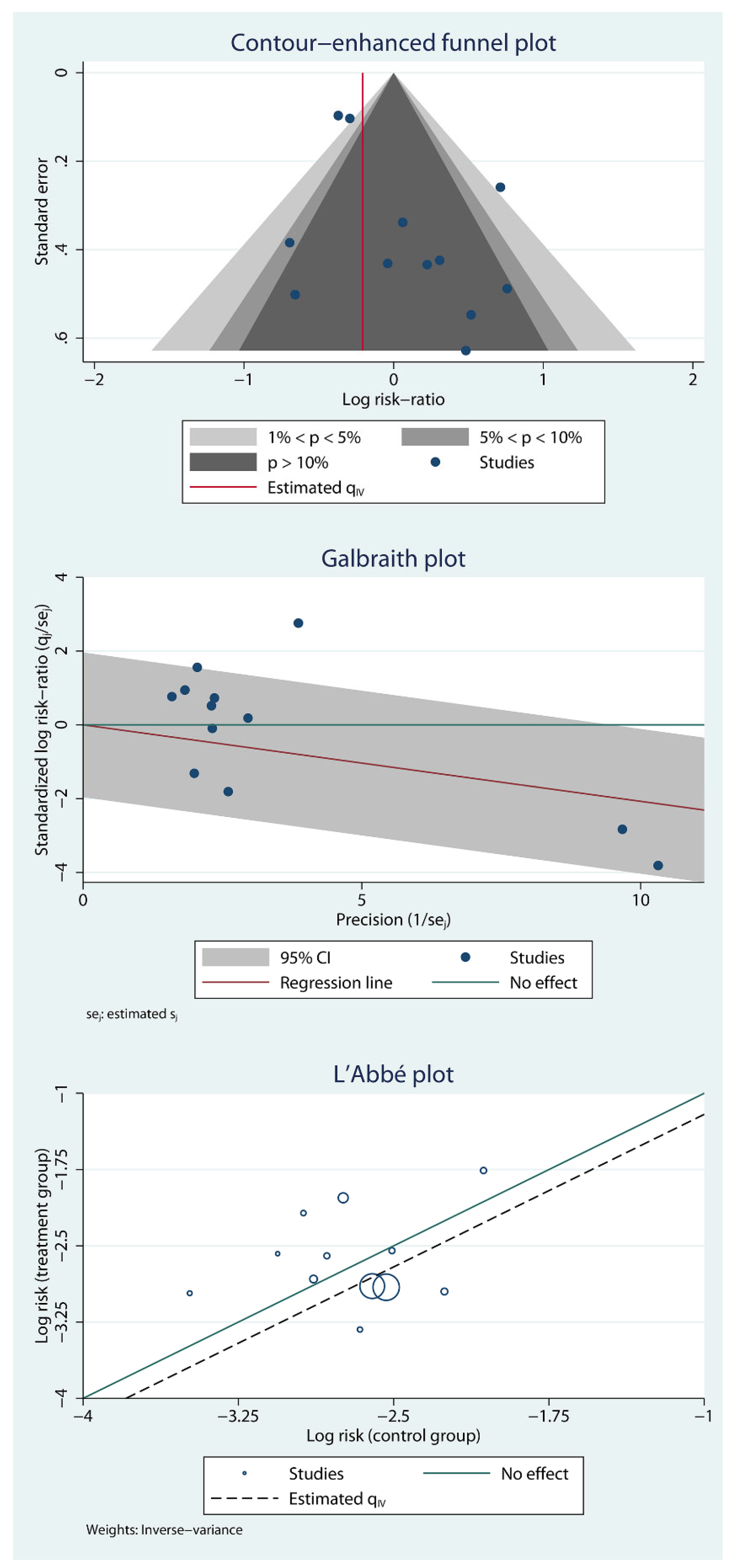

Publication Bias and Small Study Effects

GRADE Assessment

Results

Summary of the Included Studies

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Post-Discharge Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No-Home Antibiotics

Risk of Bias Assessment

Intra-Abdominal Abscess (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

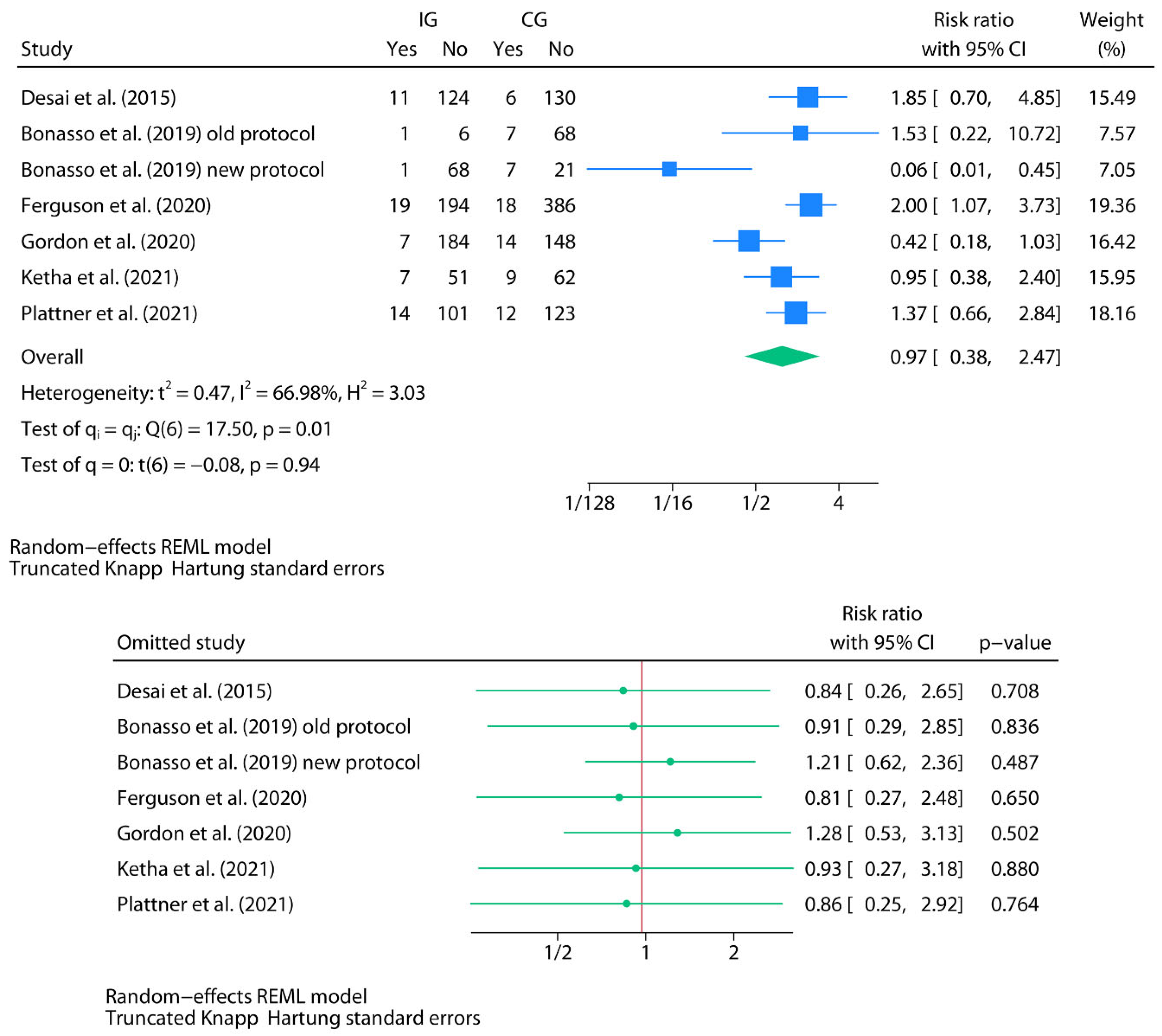

Meta-Analysis for Intra-Abdominal Abscess (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

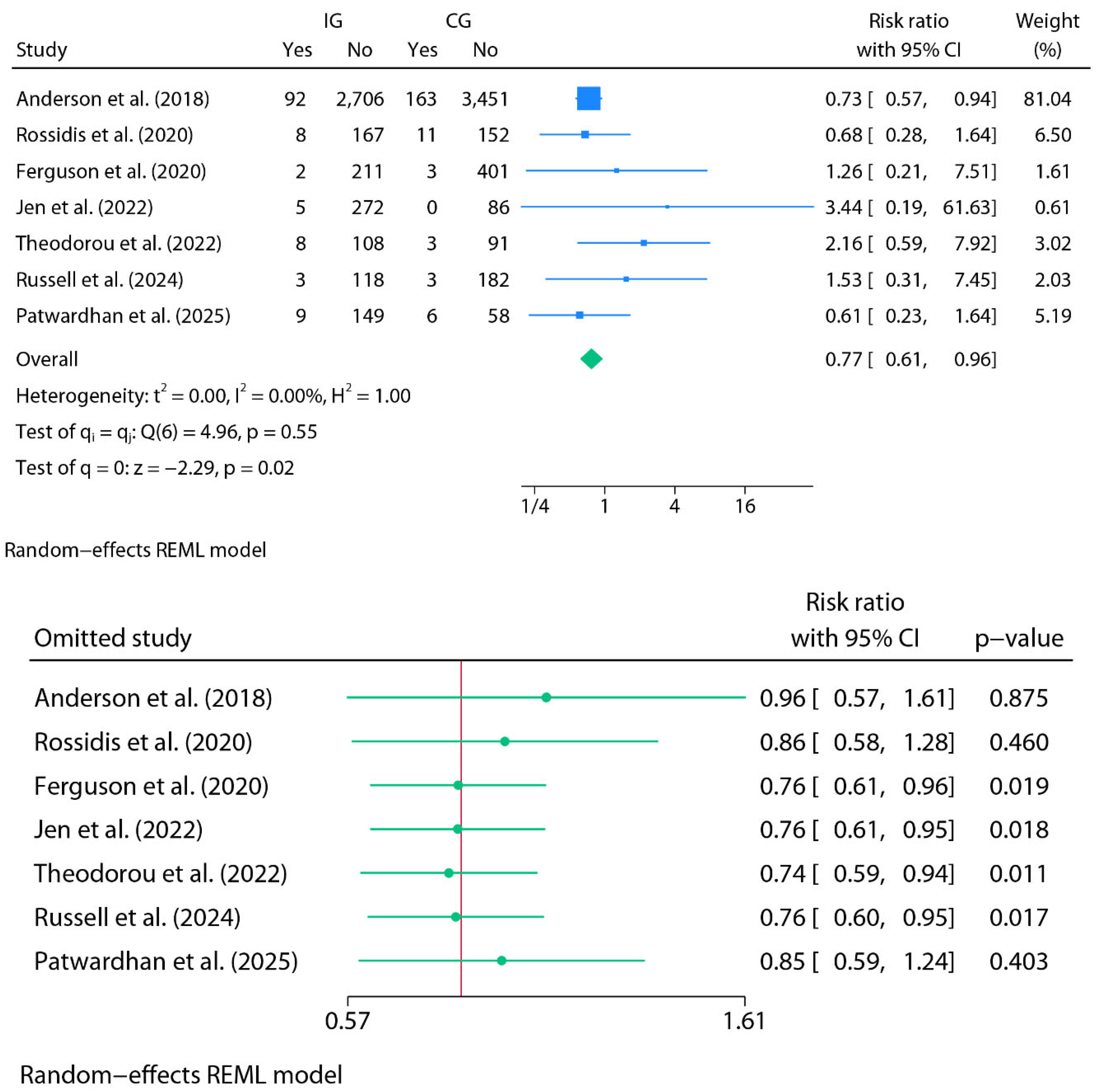

Surgical Site Infection (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

Meta-Analysis for Surgical Site Infection (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

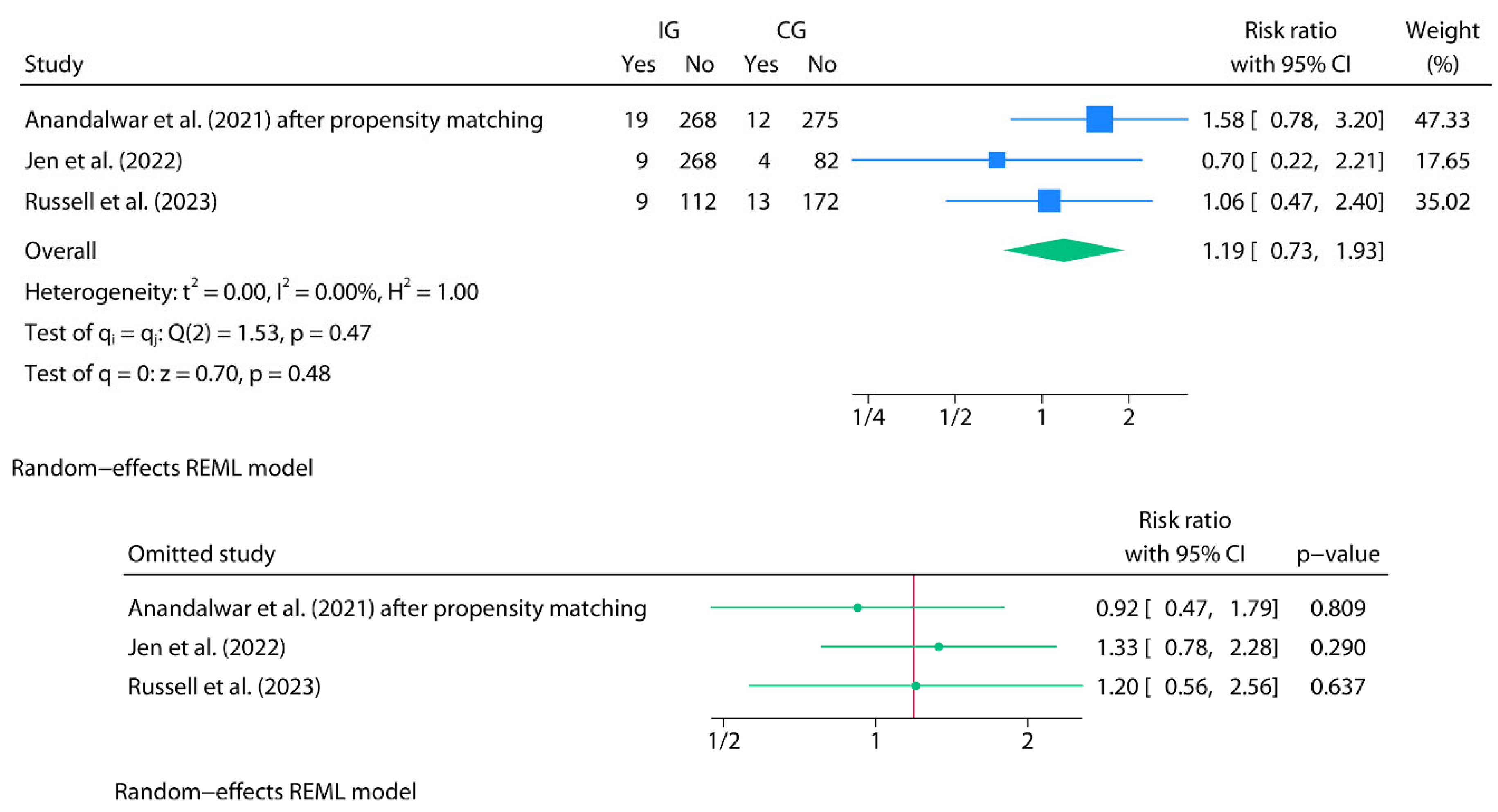

Organ Space Infection (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

Meta-Analysis for Organ Space Infection (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

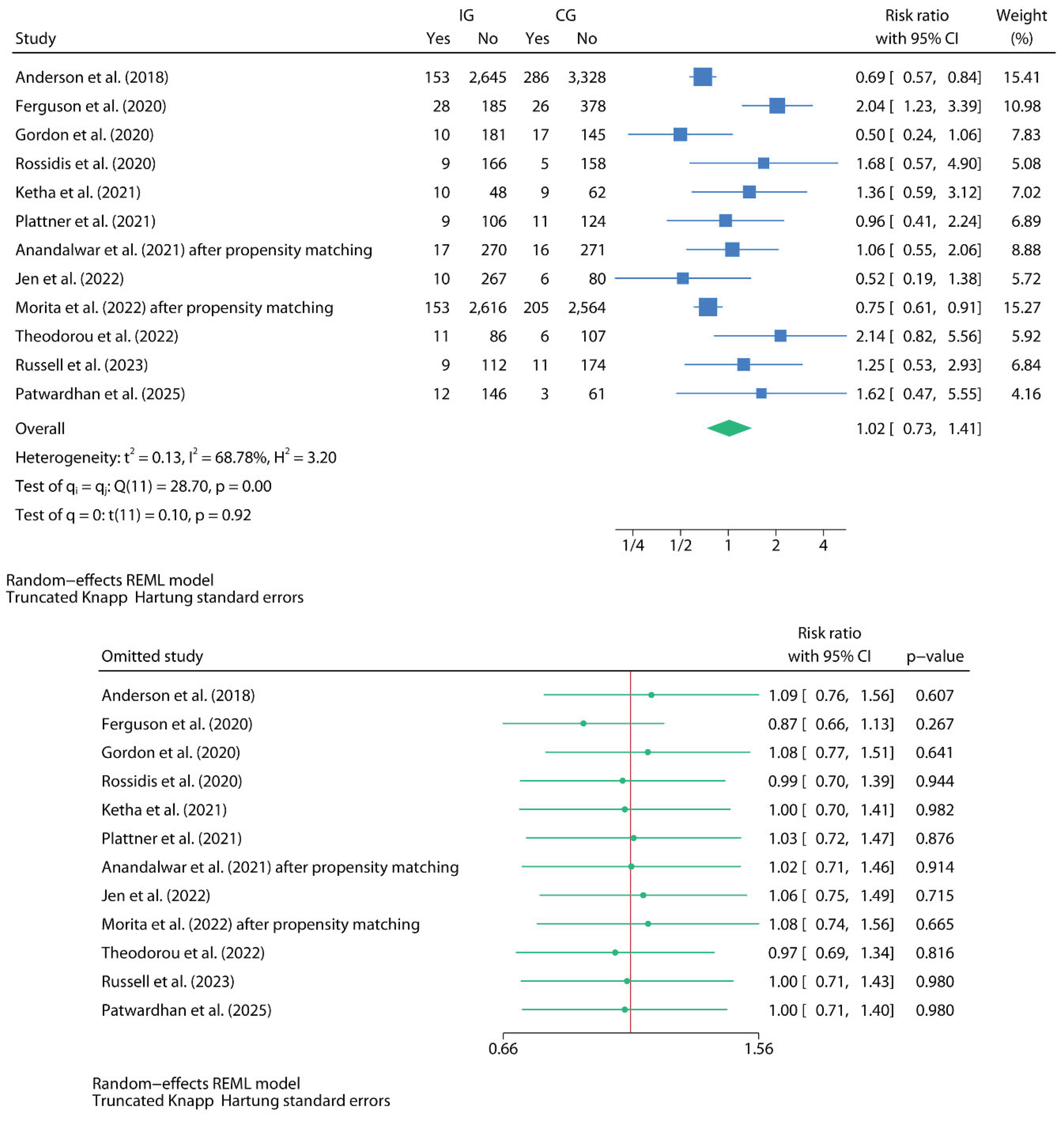

Readmissions (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

Meta-Analysis for Readmissions (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

Secondary Outcomes (Oral Home Antibiotics vs. No Home Antibiotics)

Discussion

Authorship Contribution statement

Conflicts Of Interest

Financial Statement/Funding

Ethical Approval

Statement Of Availability of the Data Used During the Systematic Review

Funding

Registration

References

- Ossai, C.R.; Pu, L.; Kaelber, D. Using Aggregated Data from 1.4 Million Pediatric Patients to Describe the Epidemiology and Demographic Characteristics of Appendicitis. Pediatrics 2020, 146, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omling, E.; Salö, M.; Saluja, S.; Bergbrant, S.; Olsson, L.; Persson, A.; Björk, J.; Hagander, L. Nationwide study of appendicitis in children. Br. J. Surg. 2019, 106, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgeades, C.; Bodnar, C.; Bergner, C.; Van Arendonk, K.J. Association of complicated appendicitis with geographic and socioeconomic measures in children. Surgery 2024, 176, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, K.A.; Bucher, B.T.; Neuman, M.I. Cost and Late Hospital Care of Publicly Insured Children After Appendectomy. J. Surg. Res. 2024, 297, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Ji, Y. Intravenous versus intravenous/oral antibiotics for perforated appendicitis in pediatric patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, J.Y.; Beaudry, P.; Simms, B.A.; Brindle, M.E. Impact of implementing a fast-track protocol and standardized guideline for the management of pediatric appendicitis. Can. J. Surg. 2021, 64, E364–E370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlstedt SG, Pham TQ, Schmeling DJ. The management of pediatric appendicitis: a survey of North American Pediatric Surgeons. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Jun;39(6):875-9; discussion 875-9. [CrossRef]

- Huttner B, Harbarth S, Carlet J, et al. Antibiotics are not automatic anymore—the French national campaign to cut antibiotic overuse. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000353. [CrossRef]

- Sabuncu, E.; David, J.; Bernède-Bauduin, C.; Pépin, S.; Leroy, M.; Boëlle, P.-Y.; Watier, L.; Guillemot, D. Significant Reduction of Antibiotic Use in the Community after a Nationwide Campaign in France, 2002–2007. PLOS Med. 2009, 6, e1000084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement : an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated August 2024). Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2015, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Borm, G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 25–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röver, C.; Knapp, G.; Friede, T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2288-14-25. PMID: 24548571; PMCID: PMC4015721Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088-1101.

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Lin, L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: Practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine 2019, 98, e15987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.A.; Alemayehu, H.; Holcomb, G.W.; Peter, S.D.S. Safety of a new protocol decreasing antibiotic utilization after laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis in children: A prospective observational study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015, 50, 912–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.K.; Bartz-Kurycki, M.A.; Kawaguchi, A.L.; Austin, M.T.; Holzmann-Pazgal, G.; Kao, L.S.; Lally, K.P.; Tsao, K. Home Antibiotics at Discharge for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis: Friend or Foe? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2018, 227, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasso, P.C.; Dassinger, M.S.; Wyrick, D.L.; Smith, S.D.; Burford, J.M. Evaluation of white blood cell count at time of discharge is associated with limited oral antibiotic therapy in children with complicated appendicitis. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 217, 1099–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossidis, A.C.; Brown, E.G.; Payton, K.J.; Mattei, P. Implementation of an evidence-based protocol after appendectomy reduces unnecessary antibiotics. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 2379–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.M.; Parker, T.D.; Arshad, S.A.; Garcia, E.I.; Hebballi, N.B.; Tsao, K. Standardized Discharge Antibiotics May Reduce Readmissions in Pediatric Perforated Appendicitis. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 255, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.J.; Choi, J.-H.; Ginsburg, H.; Kuenzler, K.; Fisher, J.; Tomita, S. Oral Antibiotics and Abscess Formation After Appendectomy for Perforated Appendicitis in Children. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 256, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketha, B.; Stephenson, K.J.; Dassinger, M.S.; Smith, S.D.; Burford, J.M. Eliminating Use of Home Oral Antibiotics in Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 263, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plattner, A.S.; Newland, J.G.; Wallendorf, M.J.; Shakhsheer, B.A. Management and Microbiology of Perforated Appendicitis in Pediatric Patients: A 5-Year Retrospective Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandalwar, S.P.; Graham, D.A.; Kashtan, M.A.; Hills-Dunlap, J.L.; Rangel, S.J. Influence of Oral Antibiotics Following Discharge on Organ Space Infections in Children With Complicated Appendicitis. Ann. Surg. 2019, 273, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, J.; Hwang, R.; Mattei, P. Post-discharge antibiotics do not prevent intra-abdominal abscesses after appendectomy in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 58, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, K.; Fujiogi, M.; Michihata, N.; Matsui, H.; Fushimi, K.; Yasunaga, H.; Fujishiro, J. Oral Antibiotics and Organ Space Infection after Appendectomy and Intravenous Antibiotics Therapy for Complicated Appendicitis in Children. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 33, 074–080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, C.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Lawrence, Y.; Saadai, P.; Hirose, S.; Brown, E.G. The Utility of Discharge Antibiotics in Pediatric Perforated Appendicitis Without Leukocytosis. J. Surg. Res. 2022, 275, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.W.; Skarda, D.E.; Jones, T.W.; Barnhart, D.C.; Short, S.S. Cessation of Antibiotics for Complicated Appendicitis at Discharge Does Not Increase Risk of Post-operative Infection. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 59, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, U.M.; Kahan, A.; Eldredge, R.S.; Russell, K.W.; Lee, J.; Short, S.S.; Padilla, B.; Cairo, S.B.; Acker, S.N.; Jensen, A.R.; et al. Comparison of Postoperative Antibiotic Protocols for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis: A Western Pediatric Surgery Research Consortium Study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2025, 60, 162165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wijkerslooth, E.M.L.; Boerma, E.-J.G.; van Rossem, C.C.; van Rosmalen, J.; Baeten, C.I.M.; Beverdam, F.H.; Bosmans, J.W.A.M.; Consten, E.C.J.; Dekker, J.W.T.; Emous, M.; et al. 2 days versus 5 days of postoperative antibiotics for complex appendicitis: a pragmatic, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| f | Country | Study design | Age | Sex M/F | Total N | Group definitions | N in IG | N in CG | Discharge criteria and TLC value | Antibiotics and posology (type, duration, route) | Events by group (IG/CG) | p-value | Commentaries |

| Desai et al. (2015) [20] | USA | Prospective |

IG: 9.6(3.8)y1 CG: 10(3.9)y1 |

IG: 60/210 CG: 150/120 |

540 |

CAA (PAA): hole in the appendix or fecalith in the abdomen IG: new protocol CG: old protocol |

270 152 discharged before day 5 (135/152 NHA and 17/152 OHA) |

270 136 discharged before day 5 (136/136 OHA) |

DC: -Regular diet tolerance -Controlled pain with oral medications -No fever over the previous 12 hours Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 17.6 (5.7)1 CG: 17.4 (5.8)1 (p=0.7) Predischarge TLC by group: IG: 8.6 (2.4)1 CG: 16.9 (3.5)1 (p<0.001) |

Old protocol: Preoperative doses of ceftriaxone and metronidazole. 50 mg/kg (max. 2 gr) IV ceftriaxone and 30 mg/kg (max. 1 gr) IV metronidazole every 24 hours -If 5 days IVA: NHA -If <5 days IVA: 7 days OHA (amoxicillin-clavulanate) Newprotocol: Preoperative doses of ceftriaxone and metronidazole. 50 mg/kg (max. 2 gr) IV ceftriaxone and 30 mg/kg (max. 1 gr) IV metronidazole every 24 hours -If 5 days IVA: NHA -If <5 days IVA and leukocytosis: 7 days OHA (amoxicillin-clavulanate) If <5 days IVA and no leukocytosis: NHA |

IAA: IG (global): 12/152 IG (NHA): 11/135 IG (OHA): 1/17 CG (OHA): 6/136 |

IAA (IG vs. CG):0.3 | The number of male cases in the study group (60 out of 270) is strikingly low and does not realistically reflect the expected sex-based prevalence of the disease. |

| Anderson et al. (2018) [21] | USA | Retrospective (NSQIP-Pediatric 2015-2016 database) |

IG: 10.4(4)y1 CG: 10.1(4)y1 |

IG:1,699/1,099 CG: 2,116/1,498 |

6,412 |

CAA: visible hole in the appendix, fecalith in the peritoneal cavity outside the appendix, abscess, or diffuse fibrinopurulent exudate in the peritoneal cavity IG: NHA CG: IVHA + OHA |

2,798 |

3,614 OHA: 3,426/3,614 IVHA: 188/3,614 |

Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 16.0 (5.7)1 CG: 17.2 (5.3)1 (p<0.01) Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

NS |

CPDM: IG (NHA): 315/2,798 CG (IVHA+OHA): 522/3,614a EDV: IG (NHA): 269/2,798 CG (IVHA+OHA): 463/3,614a RA: IG (NHA): 153/2,798 CG (IVHA+OHA): 286/3,614a RO: IG (NHA): 17/2,798 CG (IVHA+OHA): 41/3,614a SSI: IG (NHA): 92/2,798 CG (IVHA+OHA): 163/3,614a |

CPDM, EDV, RA: <0.01 RO: 0.03 SSI: 0.01 |

188 patients (2.9%) received IVHA instead of OHA, and the analyses did not adequately stratify the OHA group from the IVHA group. The authors were contacted to request the raw data, but no response was received. This should be considered a limitation when interpreting the present study's data. As this was a retrospective review of a national database, there were no standardized discharge criteria prior to hospital discharge in either group nor was a antibiotics and posology report, which may represent a major source of heterogeneity. |

| Bonasso et al. (2019) [22] | USA | Retrospective |

IG:9.28y2 CG:9.37y2 |

IG: 55/42 CG:56/26 |

179 |

CAA: GA, PAA IG: NHA CG: OHA |

97 NHA: 69/97 OHA: 28/97 |

82 NHA: 7/82 OHA: 75/82 |

DC: -Diet tolerance -Controlled pain with oral medications -No fever (<38.5°C) Preoperative TLC by group: NS Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

Old protocol: Preoperative doses of ceftriaxone and metronidazole. 50 mg/kg IV ceftriaxone and 30 mg/kg IV metronidazole every 24 hours -If <10 days IVA: OHA until 10 days of ATB treatment completionb Newprotocol: Preoperative doses of ceftriaxone and metronidazole. 50 mg/kg IV ceftriaxone and 30 mg/kg IV metronidazole every 24 hours -If TLC was elevated: OHA until 7 days of ATB treatment completionb -If normal TLC: NHA |

IAA: CG (global): 8/82 IG (Global): 10/97 OHA: 7/75 NHA: 1/7 RA: CG (global): 11/82 IG (global): 12/97 OHA: 7/28 NHA: 1/69 |

RA: 1 | Although the authors reported 9 additional intra-abdominal abscesses in the CG group and 9 in the IG group (all corresponding to patients who remained hospitalized and continued on IV antibiotic therapy), these cases were excluded from the group-specific event counts (global), as they are not within the scope of the present review. The authors report 17 abscesses in the CG and 19 in the IG, with 9 inpatient abscesses in both groups. However, for the IG, the total counts are inconsistent: they report 19 abscesses, of which 9 occurred during hospitalization, 7 in the OHA subgroup, and 1 in the NHA subgroup, resulting in a discrepancy of 2 cases. We contacted the authors to clarify this issue, but did not receive a response. Although n=28 is inferred for the OHA subgroup (total N=97 minus n=69 discharged without antibiotics, per author's Table 1, the original study's Table 1 uses n=20 for calculating the mean duration of home oral antibiotics, indicating an internal data inconsistency. |

| Rossidis et al. (2020) [23] | USA | Retrospective |

IG:12(9-14)y3,c CG:11(8-14)y3,c |

IG: 489/325c CG: 448/300c |

1,562c (PAA: 338) |

PAA: a visible hole in the appendix, a free fecalith, diffuse peritonitis, or an abscess at the time of surgery IG: new protocol CG: old protocol |

814c (PAA: 175) OHA: 59/175 NHA: 116/175 |

748c (PAA: 163) OHA: 145/163 NHA: 18/163 |

DC: -Diet tolerance -Controlled pain with oral medications -No fever (≥ 24 hours) Preoperative TLC by group: NS Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

Old protocol: Postoperative ATB 7-14 days (empirically) Most patients with OHA (empirically) Newprotocol: NHA IG: 59/175 OHA CG: 145/163 OHA |

RA: CG (global): 5/163d IG (global): 9/175d SSI: CG (global): 11/163d IG (global): 8/175d EDV: CG (global): 13/163d IG (global): 18/175d RO: CG (global): 1/163d IG (global): 2/175d |

RA: 0.42 EDV: 0.57 SSI: 0.48 RO: 0.99 |

Although it is understood that the study refers to OHA rather than IVHA, this is not explicitly stated at any point in the manuscript. The authors were contacted to confirm this information, but they did not respond. The authors did not report having determined TLC before discharge. The article provides overall data for the old protocol and new protocol groups, but does not report raw data for patients with OHA and NHA. We contacted the corresponding author to clarify this information, but did not receive a response. |

| Ferguson et al. (2020) [24] | USA | Retrospective |

IG:9.7(3.9)y1 CG:10.1(3.9)y1, |

IG: 120/93 CG: 258/146 |

617 |

PAA: intra- operative visualization of a hole in the appendix, intra- abdominal stool, or intra-abdominal fecalith IG: old protocol CG: new protocol |

213 OHA: 12/213 NHA: 201/213 |

404 OHA: 397/404 NHA: 7/404 |

DC: -Diet tolerance -Controlled pain with oral medications -No fever (≥ 24 hours) -No unexpected abdominal pain -No emesis -Normal TLC Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 17.9 (5.7)1 CG: 17.5(5.3)1 (p=0.42) Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

Preoperative ATB Piperacillin-tazobactam 100 mg/kg/dose IV every 8 h (<40 kg) or 3.375 g IV every 6h (40 kg) Or Cefepime 50 mg/kg/dose IV every 12 h, (max. 2 g/dose) Plus Metronidazole 10 mg/kg/dose IV every 8 h (max. 500 mg/dose) Postoperative ATB Amoxicillin-clavulanate 25-45 mg/kg/d PO divided every 12 h (<40 kg) or 500-875 mg/ dose every 12 h (40 kg) Old protocol (IG): no OHA standardization (12/213 OHA, 201/213 NHA) New protocol (CG): OHA (7 additional days) to all patients at discharge (397/404 OHA, 7/404 NHA) Amoxicilin-clavulanate (n=382), ciprofloxacin + metronidazole (n=13), others (n=2) |

IAA IG (global): 19/213 CG (global): 18/404 SSI: IG (global): 2/213 CG (global): 3/404 EDV IG (global): 10/213 CG (global): 15/404 RAe IG (global): 28/213 CG (global): 26/404 ROe IG (global): 2/213 CG (global): 2/404 |

IAA: 0.03 SSI: 0.8 RO: 0.51 EDV: 0.56 RA: 0.005 |

Patients who underwent conversion to open surgery, as well as those who had primary open appendectomy or remained hospitalized for 8 or more days, were excluded, which may introduce a potential selection bias. For the purposes of this review, the pre-standardization group has been defined as the intervention group (IG) and the post-standardization group as the control group (CG), since the authors standardized the practice of prescribing, rather than withholding, OHA. The article provides overall data for the old protocol and new protocol groups, but does not report raw data for patients with OHA and NHA. We contacted the corresponding author to clarify this information, but did not receive a response. Patients were excluded if an open or laparoscopic-converted-to-open appendectomy was performed. |

| Gordon et al. (2020) [25] | USA | Retrospective |

IG: 8.0 (6.0-11)y 3 CG: 9.0 (6.0-12)y 3 |

157/96 | 253 |

CAA (PAA): Perforation of the appendix without abscess or phlegmon before surgery or identification of a perforated appendix intra- operatively IG: new protocol (NHA) CG: old protocol (OHA) |

91 | 162 |

DC: -Afebrile for at least 24 h -Tolerating a regular diet -Minimal abdominal tenderness -Normal TLC Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 16.6(13.9-19.7)3 CG: 16.8(13.8-20.3)3 (p=0.57) Predischarge TLC by group: IG: 8.1(6.8-10.4)3 CG: 9.5(7.4-10.9)3 (p=0.02) |

Old protocol: While admitted: IV piperacillin/tazobactam or IV meropenem OHA (ciprofloxacin/metronidazole or amoxicillin/clavulanate) New protocol: While admitted: IV piperacillin/tazobactam or IV meropenem NHA |

IAA IG (NHA): 7/91 CG (OHA): 14/162 RA IG (NHA): 10/91 CG (OHA): 17/162 |

IAA: 0.99 RA: 0.99 |

Although all patients who underwent appendectomy before November 2017 were discharged on OHA, the length of the antibiotic course was not standardized. This varied from 5 to 14 d based on the discretion of each surgeon. In addition, patients who were sent home without antibiotics (NHA) had significantly lower TLC counts at the time of discharge (p=0.02). |

| Ketha et al. (2021) [26] | USA | Retrospective |

IG: 8.8y2 CG: 9y2 |

72/57 | 129 |

PAA: clinically perforated appendicitis at time of surgery as noted on operative reports. IG: new protocol (NHA) CG: old protocol |

58 (OHA:0/58 NHA: 58/58) |

71 (OHA: 16/71 NHA: 55) |

DC: -Afebrile for 24 h (<38.5 C) - Adequate diet tolerance. - Adequate pain control with oral medications. Preoperative TLC by group: NS Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

Old protocol: Preoperative: ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg and metronidazole 30 mg/kg IV While admitted: ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg and metronidazole 30 mg/kg IV once daily If DC accomplished before day 7, TLC was checked. If TLC >13.5x109/L, OHA (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) 7 days If TLC ≤ 13.5x109/L, NHA New protocol: Preoperative: ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg and metronidazole 30 mg/kg IV While admitted: ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg and metronidazole 30 mg/kg IV once daily NHA |

IAA IG (NHA): 7/58 CG (global): 9/71 RA IG (NHA): 10/58 CG (global): 9/71 |

IAA: 1 RA: 0.61 |

Doesn´t specify if the abscess occurs post-discharge The article provides overall data for the old protocol and new protocol groups but does not report raw data for patients with OHA and NHA. We contacted the corresponding author to clarify this information but did not receive a response. |

| Plattner el al. (2021) [27] | USA | Retrospective | 10.3 (3.9) y1 | 56%/44% 186/147g |

333 (295)f |

PAA: Presence of intra-luminal contents outside of the bowel at time of surgery (as per the operative note) IG: NHA CG: OHA, IVHA, OHA+IVHA |

NHA:115 | 180 (OHA, IVHA, OHA + IVHA) OHA: 135/180 |

DC: NS TLC: NS Preoperative TLC by group: NS Predischarge TLC by group: IG: 92 CG: 10.62 (p<0.001) |

Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage: meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, and/or a fourth-generation cephalosporin. Narrow-spectrum antibiotic coverage: metronidazole plus a third-generation cephalosporin, most commonly ceftriaxone IG: NHA CG: OHA, IVHA, OHA+IVHA |

IAA IG (NHA): 14/115g CG (OHA+IVHA+OHA/IVHA): 38/180g CG (OHA): 12/135g RA IG (NHA): 9/115g CG (OHA+IVHA+OHA/IVHA): 14/180g CG (OHA): 11/135g |

IAA: OHA+IVHA+OHA/IVHA: <0.01 OHA vs. NHA: 0.79 RA: OHA vs. NHA: 0.39 |

The study included 333 patients, but only 295 underwent appendectomy. The choice between narrow and broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage was at surgeon´s discretion Initial broad-spectrum antibiotic use was associated with increased odds of postoperative abscess formation (OR 3.17, 95%CI 1.58-6.38) Patients with home antibiotics (OHA, IVHA and mixed OHA + IVHA) had a significantly higher rate of postoperative abscess formation than NHA while patients with OHA did not differ in abscess formation compared to the NHA group. The average discharge TLC was significantly higher in the group of patients who experienced readmission compared to those who did not (p<0.001). |

| Anandalwar et al. (2021) [28] |

USA | Retrospective (NSQIP-P database from January 2013 to June 2015) | 10 (7-17) y3 |

Before PM: 416/370 After PM: 334/240 |

Before PM: 711 (786) PM: 574 |

CAA: Presence of a visible hole, diffuse fibrinopurulent exudate extending outside the right lower quadrant and pelvis (defined as exudate in more than two quadrants of the abdomen and pelvis), intra-abdominal abscess, or an extra-luminal fecalith IG: NHA CG: OHA |

Before PM: 306 After PM: 287 |

Before PM: 405 After PM: 287 |

DC: NS Preoperative TLC by group (before PM): IG: 74 (24.2)5 CG: 91 (22.5)5 (p=0.02) Preoperative TLC by group (after PM): IG: 72 (25.1)5 CG: 77 (26.8)5 (p=0.89) Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

NS |

OSI (before PM)h: IG (NHA): 6.2% 19/306g CG (OHA): 4.4% 18/405g OSI (after PM)h: IC (NHA): 6.6% 19/287g CG (OHA): 4.2% 12/287g RA (after PM): IC (NHA): 5.9% 17/287g CG (OHA): 5.6% 16/287g |

OSI (before PM): 0.30 OSI (after PM: 0.21 RA (after PM): 0.71 IAA: 0.30 |

Since this work reports data from a database that includes 29 NSQIP-Pediatric hospitals, therefore it can´t be assumed that discharge criterion, and the antibiotic used and its posology was consistent among all the hospitals, as it has not been specified on the paper. Adjusted analyses (after PM) showed no statistically significant differences between groups (OHA/NHA) for either OSI or RA. The sex distribution table reflects the pre-exclusion cohort (n=786), which explains why male + female totals exceed the final sample. After excluding patients with inpatient imaging or IV antibiotics at discharge, the analytic cohort was reduced to 711 |

| Jen et al. (2022) [29] | USA | Retrospective | Main study arm (no initial DSI): IG: 9.9 (4.0)y1 CG: 10.2 (4.2) y1 |

232/173 Main study arm (no initial DSI): 203/160 |

405 Main study arm (no initial DSI):363 |

CAA: (PAA): either intraoperative or pathologic findings of PAA IG: NHA CG: OHA |

288 Main study arm (no initial DSI): 277 |

117 Main study arm (no initial DSI): 86 |

DC: based on attending surgeon preference but based on somewhat standardized guidelines that included remaining afebrile for at least 24 h, tolerating a regular diet, and having pain that was well-controlled with oral analgesics. Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 16.9(5.3)1 CG: 17.5(6.4)1 (p=0.36) Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

Initial antibiotics Ceftriaxone/metronidazole (CG,n=75; IG, n=259) Piperacillin/tazobactam (CG, n=6; IG, n=8) Other (CG, n=5; IG, n=10) OHA (CG): Ciprofloxacin/metronidazole (n=72) Amoxicillin-clavulanate (n=12) Other (n=2) |

OSI: IG (NHA): 9/277 CG (OHA): 4/86 EDV: IG (NHA): 23/277 CG (OHA): 10/86 RA: IG (NHA): 10/277 CG (OHA): 6/86 SSI: IG (NHA): 5/277 CG (OHA): 0/86 |

OSI: 0.54 EDV: 0.35 RA: 0.18 SSI: 0.21 |

The authors do not analyze the presence of OSI, EDV, RA or SSI based on the antibiotics administered. The use of multiple different antibiotics and regimens without protocol may constitute a relevant source of heterogeneity. |

| Morita et al. (2022) [30] | Japan | Retrospective (Diagnosis Procedure Combination database) | 3-18y4 | Before PM: 7,842/5,258 After PM: 3,330/2,208 |

Before PM: 13,100 After PM: 5,538 |

CAA: NS IG: NHA CG: OHA |

Before PM: 9,599 After PM:2,769 |

Before PM: 3,501 After PM:2,769 |

DC: NS Preoperative TLC by group: NS Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

NS |

RA due to OSI (before PM): IG (NHA): 333/9,599 CG (OHA): 163/3,501 RA due to OSI (after PM): IG (NHA): 93/2,769 CG (OHA): 145/2,769 Global RA (within 60 days of discharge) (before PM): IG (NHA): 549 /9,599 CG (OHA): 247/ 3,501 Global RA (within 60 days of discharge) (after PM): IG (NHA): 153/2,769 CG (OHA): 205/2,769 |

RA due to OSI (PM): 0.002 RA due to OSI (after PM: 0.001 Global RA (before PM): 0.005 Global RA (after PM): 0.004 |

Since this work reports data from a nationwide database that includes more than 1,200 hospitals, therefore it can´t be assumed that discharge criterion, and the antibiotic used and its posology was consistent among all the hospitals, as it has not been specified on the paper. |

| Theodorou et al. (2022) [31] | USA | Retrospective |

Old protocol: 8.9 (6.2-11.4) y3 New protocol: 9.2 (6.7-12.3) y3 |

132/78 | 210 |

CAA: PAA: hole in the appendix, a fecalith in the abdomen, with or without an associated abscess or purulent fluid. IG: New protocol CG: Old protocol |

97 OHA: 14/97 |

113 OHA: 80/113 |

DC: -Afebrile for 24 h - Tolerating a diet -Pain manageable with oral medications -A benign examination Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 16.3(14-18.23 CG: 18.5(14.8-21.93 (p=0.003) Predischarge TLC by group: IG: 9.2(7.3-10.7)3 CG: 8.9(7.7-10.9)3 (p=0.77) |

Preoperative administration of intravenous IV ceftriaxone and metronidazole Postoperative treatment: NS Old protocol: If normal TLC: 5 days OHA If abnormal TLC: 10 days OHA OHA: 80/113; NHA: 33/113 New protocol If normal TLC: NHA If abnormal TLC: 10 days OHA OHA: 14/97; NHA: 83/97 |

SSI: IG (global): 9/97 CG (global): 2/113 NHA: 8/116g OHA: 3/94g RA: IG (global): 11/97 CG (global): 6/113 |

SSI (CG vs. IG): 0.03 SSI (OHA vs. NHA): 0.53 RA: 0.13 |

Open appendectomy patients were excluded as there may be a higher rate of surgical site infections in this patient population compared to laparoscopic appendectomy The authors do not specify a cut-off point for TLC. There were no significant differences in TLC at discharge between the SSI and non-SSI groups. The article provides overall data for the old protocol and new protocol groups, but does not report raw data for patients with OHA and NHA. We contacted the corresponding author to clarify this information, but did not receive a response. The authors report proportions conditioned on outcome: 3/11 patients with SSI (27.3%) received antibiotics, and 91/199 without SSI (45.7%) did. However, restructuring the data by treatment group shows that 3 of 94 patients who received antibiotics developed SSI (3.2%), compared to 8 of 116 without antibiotics (6.9%). This corresponds to infected:non-infected ratios of 0.03 (3/91) in the antibiotic group and 0.07 (8/108) in the no-antibiotic group—identical to the original data but correctly aligned for effect estimation. |

| Russell et al. (2023) [32] | USA | Retrospective (NSQIP database from January 2015 to May 2022) |

Old protocol: 9.8(4) y1 New protocol: 9.6(4) y1 |

173/133g | 306 |

CAA: Presence of a visible hole, diffuse fibrinopurulent exudate (defined as exudate in >2 quadrants of the abdomen and pelvis), intra-abdominal abscess, or an extraluminal fecalith IG: new protocol CG: old protocol |

121 OHA:10/121 NHA:111/121 |

185 OHA:170/185g IVHA:1/185g NHA:14/185g |

DC: -Adequate oral intake -Feeling generally well. -No fever (<38.5ºC) Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 17(5.9)1 CG: 17.7(6.2)1 (p=0.24) Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

In both protocols, patients were treated with intravenous (IV) Ceftriaxone and IV Metronidazole while hospitalized. CG: The CG was discharged home on OHA (Augmentin or Cefdinir and Metronidazole if they had an allergy to Augmentin) if their TLC was elevated at the time of discharge IG: NHA. No predischarge TLC check. |

SSI: IG (global): 3/121 CG (global): 3/185 OSI: IG (global): 9/121 CG (global): 13/185 RA: IG (global): 9/121 CG (global): 11/185 |

SSI: 0.68 OSI: 1 RA: 0.64 |

The article provides overall data for the old protocol and new protocol groups but does not report raw data for patients with OHA and NHA. We contacted the corresponding author to clarify this information but did not receive a response. |

| Patwardhan Et al. (2025) [33] |

USA | Retrospective (NSQIP-P database from 2021 to 2023) |

No-OHA: 9.3 (4.3) y1 OHA if high TLC: 10.1 (4.0) y1 OHA to complete a minimum number of total postoperative ATB days: 9.5 (4.0) y1 Standardized OHA discharge: 10.1 (3.7) y1 |

827/515 | 1,342 |

CAA: Intraoperative findings of CAA: the presence of a visible hole in the appendix, an intraperitoneal fecalith, diffuse fibrinopurulent exudate, or the presence of an abscess. IG: NHA cohort (cohort 1) CG: OHA cohort (cohort 4) |

158 OHA: 7/158 NHA: 151/158 |

64 OHA: 59/64 NHA: 5/64 |

DC: -Lack of fever -Resolution or significantly improving abdominal pain -Tolerance of adequate oral intake Preoperative TLC by group: IG: 17.1(6.0)1 CG: 17.3(6.2)1 (p=0.8)(4-groups comparison) Predischarge TLC by group: NS |

Postoperative antibiotic protocol used at each site was collected, with 6/9 centers using ceftriaxone/metronidazole as intravenous therapy while inpatient and 7/8 centers using amoxicillin/clavulanic acid as the oral antibiotic of choice on discharge (Original articles` Supplemental Table 1) IG: 7/158 OHA; 151/158 NHA CG: 59/64 OHA; 5/64 NHA |

SSI: IG (Global): 9/158 CG (Global): 6/64 RA: IG (Global): 12/158 CG (Global): 3/64 |

SSI (4-protocols comparison): 0.43 RA (4-protocols comparison): 0.06 |

Since this work reports data from a database that includes 29 NSQIP-Pediatric hospitals, therefore it can´t be assumed that discharge criterion, and the antibiotic used and its posology was consistent among all the hospitals. Hospitals were classified into four groups based on their protocol: 1) No OHA, 2) OHA if high TLC on the day of discharge, 3) OHA to complete a minimum number of total post-operative ATB days, and 4) standardized OHA discharge regardless of inpatient antibiotic duration. Only patients undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy were included. The article provides overall data for different protocols and new protocol groups but does not report raw data for patients with OHA and NHA. We contacted the corresponding author to clarify this information, but did not receive a response. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).