Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global health threat, driven by inappropriate and excessive use of antimicrobials. In 2021, an estimated 4.71 million deaths were associated with bacterial AMR worldwide and projections indicate that this number may rise to 8.22 million annually by 2050 without intensified interventions [

1]. In response to the escalating burden of AMR, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Action Plan (GAP) on AMR in 2015, calling for the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programs to optimise antimicrobial use [

2].

Since the inception of AMS programs over the last 2-3 decades, various stewardship strategies have been developed to address antibiotic misuse [

3]. However, antibiotic use in the surgical units remain high, and are often inappropriate; despite best efforts, antibiotic use in surgical departments remains a key stewardship challenge in many countries [

4,

5,

6]. Point prevalence survey (PPS), which is a cross-sectional method that captures detailed data on antimicrobial use among inpatients at a specific point in time [

6,

7], has been increasingly used internationally to describe antibiotic usage patterns. Based on the 2015 Global PPS, there is wide regional variability in proportion of antimicrobial prescribing within surgical wards, ranging from 28.0% in Western Europe, 34.2% in East and South Asia, to 52.5% in Oceania. Additionally, surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) constituted 12.0% of antimicrobial use in Western Europe, 21.4% in East and South Asia, and 12.6% in Oceania [

7].

In Singapore, the National Antimicrobial Taskforce was established in 2009, and AMS programs were mandated across acute restructured hospitals nation-wide [

8]. Singapore General Hospital (SGH), which is Singapore’s largest acute tertiary care and teaching hospital has established its AMS program since 2008. SGH comprises approximately 2000 beds and over 50 clinical specialties. Of these, 18 are surgical specialties and subspecialties, including general surgery, orthopaedic, cardiothoracic surgery, neurosurgery, plastic and reconstructive surgery, vascular surgery, ophthalmology, and surgical oncology, among others.

Existing AMS Strategies Since 2008

Since its inception, SGH AMS has in place, a suite of internationally recommended strategies [

9,

10,

11]; broadly classified into 1) prospective audit feedback; 2) institutional antibiotic guidelines; 3) use of information technology (IT) tools; and 4) physician engagement and education.

In PAF, AMS pharmacists review prescriptions for select broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., carbapenems, piperacillin-tazobactam, and intravenous fluoroquinolones) and provide prescribers with recommendations when antibiotics are sub-optimally prescribed. Additionally, department-level findings and recommendations are disseminated via quarterly reports to department heads to improve antibiotic use. Furthermore, in-house empiric treatment and SAP guidelines have been developed in collaboration with clinical departments. These guidelines are then embedded into the electronic medical record (EMR) system as computerised decision support systems (CDSS), offering indication-specific antibiotic recommendations. AMS pharmacists also participate in multidisciplinary ward rounds—particularly in intensive care units and selected surgical departments. This "handshake stewardship" approach facilitates real-time collaborative reviews of antimicrobial therapy to improve acceptance of AMS recommendations.

Enhanced Targeted AMS Strategies (2021-2024)

These conventional strategies demonstrated positive outcomes, including improved targeted prescribing practices, reduced mortalities, infection-related readmissions and hospital length of stay [

12]. However, in the PPS conducted by SGH AMS pharmacists in 2021, it was observed that antibiotic use in the surgical inpatient units was high, 60.6%, and this is an area for improvement. Notably, there was a high proportion of patients (63.7%) with SAP duration beyond 24 hours, despite strong recommendations to discontinue SAP after skin closure for most surgeries, as advised by international and local hospital guidelines [

7,

13,

14,

15,

16].

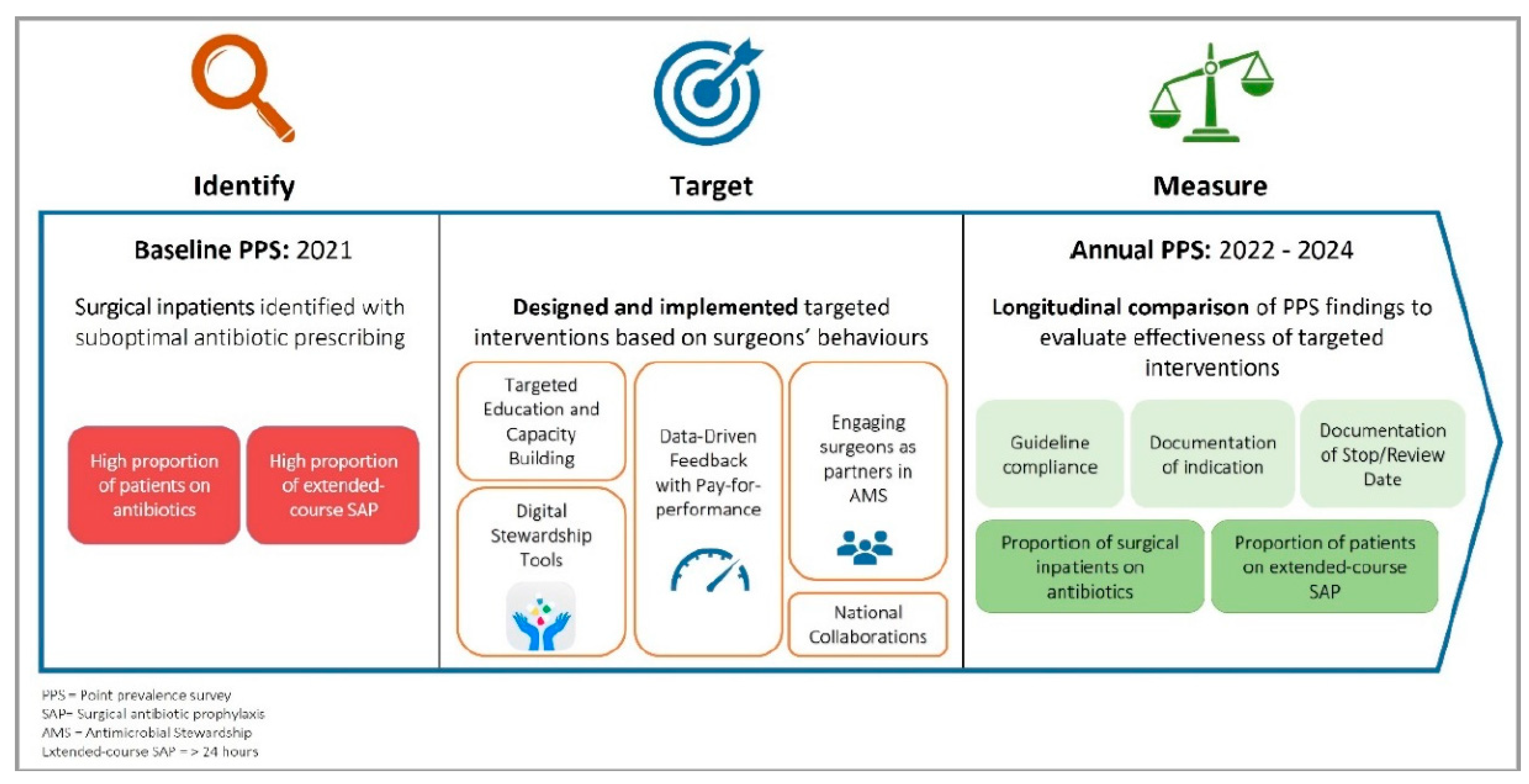

Hence, we implemented a series of targeted AMS strategies among surgical departments to promote appropriate antibiotic use, namely 1) data-driven feedback with pay-for-performance; 2) targeted education and capacity building; 3) engaging surgeons as partners in AMS; 4) digital stewardship tools; and 5) national collaborations (

Figure 1).

In this study, we aim to evaluate the impact of these multi-pronged AMS strategies on the change in antibiotic prescribing patterns in surgical inpatients using serial PPS findings from 2021 to 2024. Antibiotic prescribing patterns that will be evaluated include 1) proportion of surgical inpatients prescribed with antibiotics; 2) proportion of patients who received extended-course SAP and 3) prescriber’s adherence to quality indicators.

Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

Point prevalence surveys (PPS) were conducted annually at SGH between 2021 to 2024. SGH PPS methodology was aligned with the Global-PPS Inpatient Module (available at

www.global-pps.com).

Each PPS was performed based on a single day, 27 April 2021, 20 January 2022, 14 February 2023 and 6 March 2024. Selection of PPS dates was based on availability of AMS pharmacists and weekends/public holidays were avoided as surgeries were fewer, which may potentially introduce selection bias.

Lists of inpatients who remains admitted to surgical departments at the snapshot time of 8.00am on the specified PPS date were extracted from EMR. Patients who were admitted for day surgeries were excluded from PPS as they are considered ambulatory care patients.

All surgical inpatients with an antibiotic prescription active at 8 a.m. were surveyed by trained AMS pharmacists. Patients who received SAP in the 24 hours prior were included in the survey even if antibiotics had stopped by 8.00am. Data collection and patient review was performed retrospectively using daily rounding notes on the morning of PPS date and information from EMR.

The following information was collected as per Global-PPS protocol:

Proportion of surgical inpatients on antibiotics

Antibiotic name, dose, route and frequency

Antibiotic indication

- o

Therapeutic treatment (community-acquired infection or healthcare-associated infection) or

- o

Prophylactic use (medical or surgical); indications for SAP are further stratified based on duration at snapshot time of 8.00am, categorised as ≤ 24 hours or > 24 hours

In addition, the following were collected to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of our AMS strategies:

Enhanced Targeted AMS Strategies (2021-2024)

From 2021, SGH introduced a series of enhanced AMS interventions, spanning hospital-wide strategies and surgeon-specific initiatives.

-

1.

Data-Driven Feedback with Pay-for-performance

Prior to 2021, AMS performance at SGH was incentivised through the inclusion of two key metrics in departmental key performance indicators (KPI): 1) appropriateness of carbapenem prescriptions and 2) appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing using the institution’s CDSS. These KPIs determine departmental AMS performance and directly influenced the annual performance bonuses of surgical departments.

In 2021, we obtained institution’s senior management support to replace “CDSS appropriateness” metric with the “proportion of inpatients prescribed antibiotics” as the KPI. This new KPI promotes appropriate antibiotic use across all antibiotic classes and beyond the scope of CDSS-supported antibiotic prescriptions, which were limited to antibiotics recommended within the in-house antibiotic guidelines. Moving targets were set based on each department’s historical performance, allowing a more comprehensive oversight of antibiotic usage patterns within each clinical department. Concurrently, quarterly departmental reports were enhanced to include the performance of individual departments in respect to meeting of KPIs and highlighted key finding from annual PPS.

-

2.

Targeted Education and Capacity Building

AMS educational outreach was expanded to strengthen stewardship competencies among surgeons. Dedicated lectures pertaining to principles of antibiotic use were delivered annually to junior surgeons. On the other hand, senior surgeons were engaged through annual AMS roadshows at department meetings, where there were dissemination of evidence-based literature review to promote appropriate antibiotic use (e.g. sharing of local/international data on benefit of short-course SAP without compromising SSI rates), guideline updates, introduction of new AMS interventions, and strategies to improve accountability of antibiotics prescribing (e.g. surgeons were encouraged to document antibiotic indications and stop/review dates of antibiotics in daily rounding notes).

-

3.

Engaging surgeons as partners in AMS: Identifying champions and fostering collaborations

The AMS unit partnered with various surgical departments to update antibiotic guidelines and implement quality improvement projects aimed at advocating appropriate antibiotic selection and reducing antibiotic duration, especially in SAP. These initiatives were made possible through the visibility of existing stewardship efforts, which helped identify key AMS champions within each department. AMS champions were surgeons who demonstrated leadership, ownership and commitment to improve antibiotic use in surgical care.

-

4.

Digital Stewardship Tools and Platforms

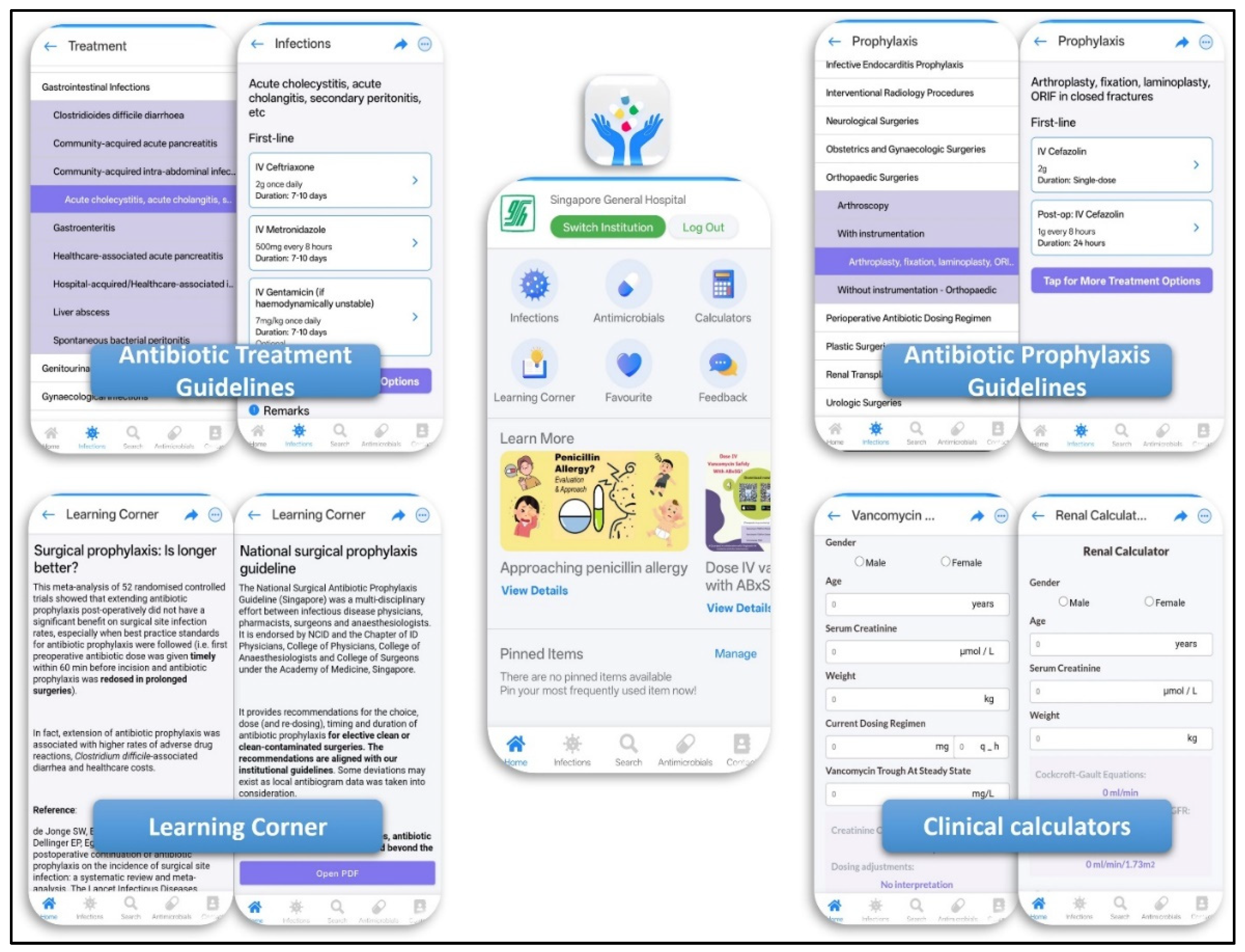

With the advancement of digital solutions and the increasing reliance of junior doctors on mobile phones to search for clinical information, we envisioned that a mobile application that provides accurate and reliable information is the next AMS tool that would advocate for appropriate antibiotic choice and duration. In March 2023, SGH AMS launched

ABxSG, a mobile application designed with the philosophy of “Developed by clinicians, for clinicians”. The development of

ABxSG was informed by a series of focus-group discussions with clinicians, ensuring application features were highly customised to their needs (

Figure 2) [

18].

Apart from providing prescribers with quick and convenient access to in-house antibiotic treatment and SAP guidelines, ABxSG also supports continuous stewardship development through its “Learning Corner,” which features regularly updated educational content. Learning corner includes concise literature summaries on key stewardship topics such as the efficacy of short-course SAP and the role of procalcitonin in guiding antibiotic initiation for infections, e.g. acute pancreatitis.

-

5.

National Collaborations

In a national initiative to improve the use of SAP through harmonization of SAP guidelines nationally, there were collaborative efforts with surgeons to review the literature on SAP and to mutually establish stewardship standards.

Measuring of Impact

A longitudinal comparison of PPS findings from 2021 to 2024 was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the enhanced AMS strategies. The following areas were evaluated: 1) trending of proportion of surgical inpatients on antibiotics; 2) proportion of patients who received extended-course SAP; and 3) prescriber’s adherence to quality indicators (including guideline compliance, documentation of antibiotic indication, and antibiotic stop/review date). In addition, SSI rates were compared between patients who received ≤24 hours (short-course) vs >24 hours (extended-course) of SAP (actual duration) using the chi-square test, conducted using SPSS (Version 26.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Ethnics Declaration

This study was exempted from our institutional ethics board review (Singhealth Institutional Review Board Reference 2022/2560).

Results

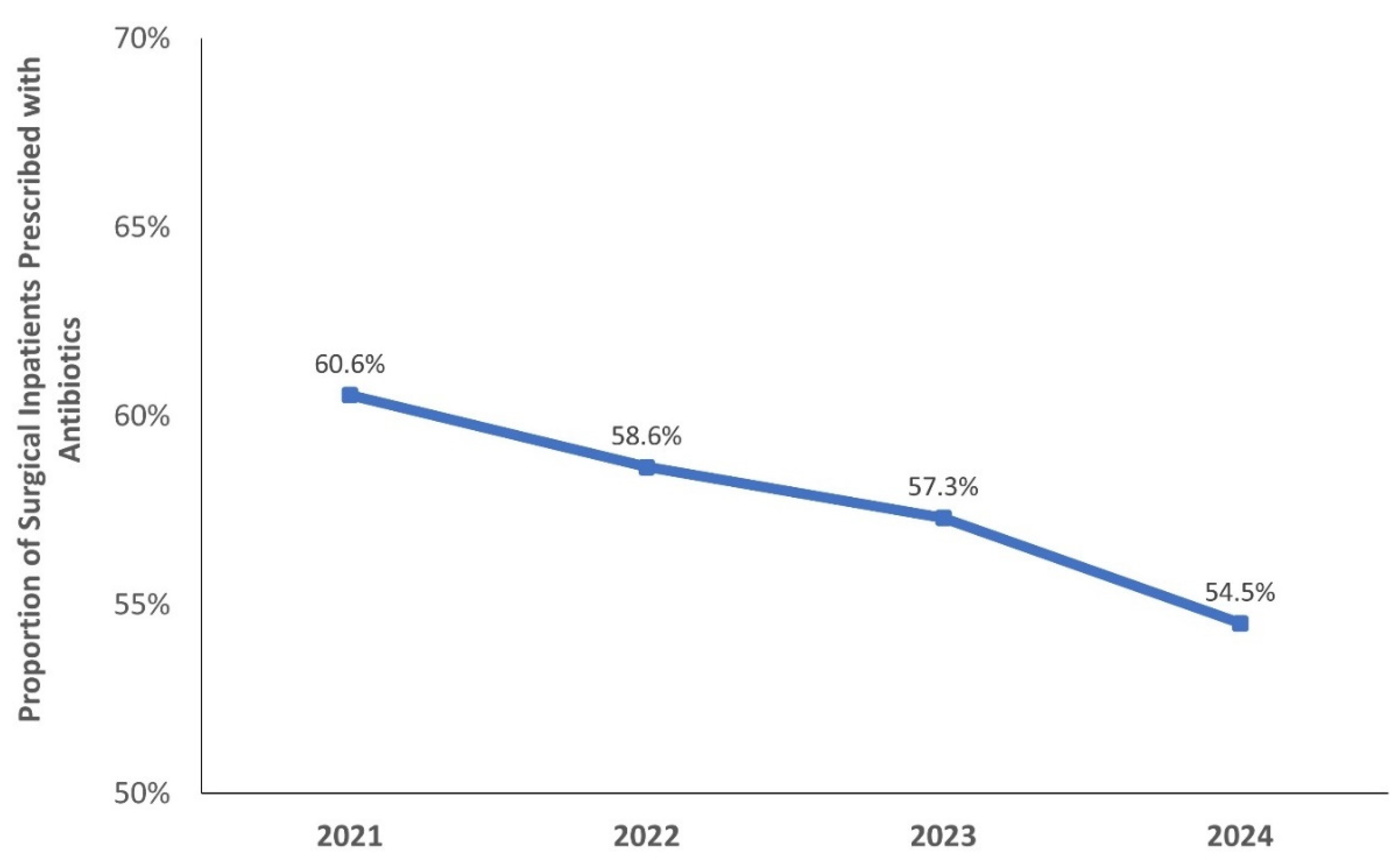

Across the four annual PPS, a total of 2,141 surgical inpatients were surveyed and 1,659 courses of antibiotics were evaluated (

Table 1). Notably, the proportion of surgical inpatients prescribed with antibiotics showed a gradual decline over time, from 60.6% in 2021 to 54.5% in 2024 (

Figure 3).

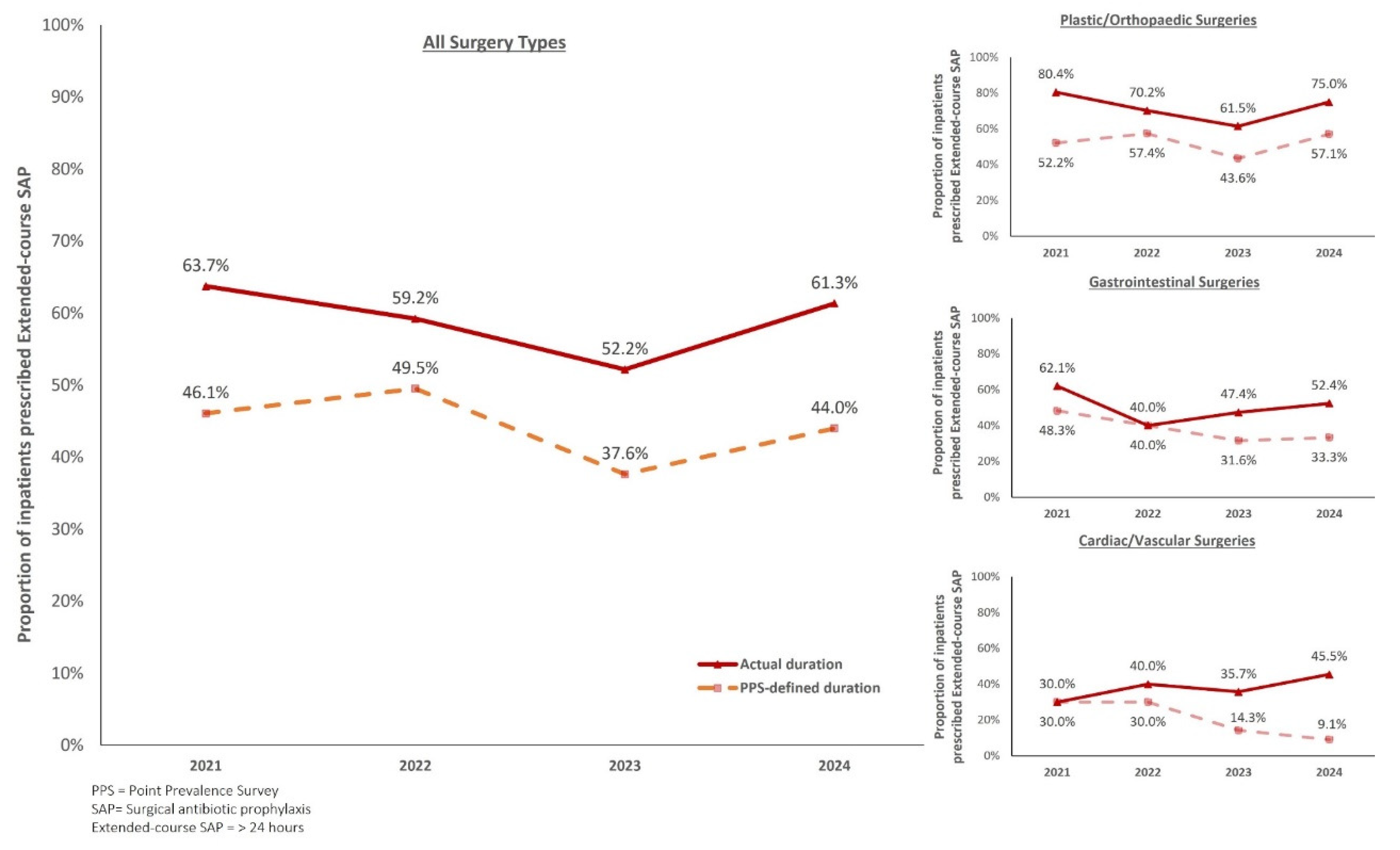

Surgical Prophylaxis

Among antibiotics used within the surgical units, overall, 26.3% was used for SAP across the 4 PPS. Between 2021 and 2023, there was a general decrease in proportion of patients who received extended-course SAP. However, this was followed by an increase in 2024 (

Figure 4).

This trend was observed in both PPS-defined SAP durations [46.1% (2021) to 37.6% (2023); 44.0% (2024)] and actual SAP durations [(63.7% (2021) to 52.2% (2023); 61.3% (2024)]. However, when reviewing both metrics of measuring SAP durations, there was a discordance between PPS-defined and actual SAP durations, with difference ranging from 10-18%. Nevertheless, there was no difference in SSI between patients who received actual SAP duration for ≤24 hours or > 24 hours of (2/193, 1.0% vs 8/247, 3.2%, p=0.2).

The top 3 surgeries that contributed to SAP use were plastic/orthopaedic, gastrointestinal, followed by cardiac/vascular surgeries, accounting for over 70% of SAP use. There was an overall reduction in proportion of patients with actual SAP duration >24 hours during the study period among the plastic/orthopaedic (80.4% to 75%) and gastrointestinal surgeries (62.1% to 52.4%). In cardiac/vascular surgeries, it was observed that trends of SAP duration differed when different definitions were applied. There was an increase in proportion of patients with extended-course SAP (actual duration) from 30.6% to 45.5%. In contrary, when evaluated using PPS-defined SAP duration, a decreasing trend from 30% (2021) to 9.2% (2024) was observed.

PPS Quality Indicators

Key quality indicators pertaining to documentation showed consistent improvement from 2021 to 2024 (

Figure 5). The proportion of antibiotic prescriptions with a documented indication rose from 69.8% (2021) to 80.9% (2024). Additionally, documentation of a stop or review date improved from 42.6% (2021) to 52.7% (2024). Compliance with institutional antibiotic guideline, where available, remained high with slight increase from 80.4% (2021) to 84.8% (2024).

Discussion

In this study, we used PPS to identify surgical inpatients as targets of enhanced AMS strategies and had successfully demonstrated that serial PPS findings can be a useful approach in evaluating the effectiveness of multi-pronged AMS strategies on antibiotic prescribing.

The PPS methodology provides a comprehensive, cross-sectional snapshot of hospital-wide prescribing practices across various wards and patient populations. PPS enables the identification of specific prescribing gaps, such as high rates of antimicrobial consumption, frequent use of prolonged SAP, suboptimal guideline adherence, and inadequate documentation practices [

6,

7,

19,

20,

21]. While PPS is limited to specific survey time points, we demonstrated that PPS data can be trended over time, to assess the impact of AMS interventions and direct future AMS efforts.

Since the inception of the AMS program at SGH in 2008, our strategies primarily targeted broad-spectrum antibiotics (such as carbapenems, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, and intravenous fluroquinolones). However, a PPS conducted in 2021 showed antibiotic prevalence of 60.6% among surgical inpatients, which was much higher than many other countries [

6]. The PPS findings highlight the need to maintain close surveillance to narrow-spectrum antibiotics (such as cefazolin, ceftriaxone, and co-amoxiclav, which are the top 3 most prescribed antibiotics in surgical departments). Appropriate narrow-spectrum antibiotics use in both treatment and SAP in the inpatient surgical units is recommended and work in progress. Currently, PAF of narrow spectrum antibiotics is not possible due to resource constraints at SGH.

Impact of Enhanced AMS Strategies

Serial PPS findings were used to evaluate the impact of our enhanced AMS strategies in the surgical units at SGH. The proportion of surgical inpatients on antibiotics decreased from 60.6% in 2021 to 54.5% in 2024, with an average annual reduction of 1.5% or 2,930 antibiotic-free days (365 days × 1.5% × 2,141 patients/4 years). Assuming all antibiotics costs approximate those of intravenous co-amoxiclav (most common antibiotic prescribed for surgical inpatients), this translates to annual cost savings of $228,276 (based on daily cost of antibiotic and nursing administration) and 4,395 nursing manhours.

As antibiotic treatment contributes to 69.7% of the indication of antibiotic prescribing, the observed reduction in antibiotic use likely reflects that surgeons are increasingly more cognizant in ensuring appropriate antibiotic duration for management of active infections. The increased alignment of surgeons’ practices with stewardship principles can also be observed from the improvement in PPS quality indicators, such as an increase in proportion of patients with documentation of antibiotic indication and plans to review/discontinue antibiotics in the case notes, which served as visual reminders to review antibiotic use daily.

Importantly, from our study, we observed that there was no difference in SSI rates among patients who received short-course versus extended-course SAP (actual duration). This is consistent with global evidence that extended-course SAP does not improve surgical outcomes [

14,

15,

16]. As part of our physician engagement, the SGH AMS program shared local and international data on the benefits of short-course SAP in elective unilateral total knee arthroplasty and cardiothoracic surgeries with the orthopaedic and cardiothoracic surgeons respectively to encourage guideline adherence to short-course SAP [

22,

23]. Also, the AMS program partnered with the hepatobiliary surgeons in the revision of in-house SAP guidelines with the aim to optimise SAP choice and duration [

24].

Despite increasing evidence demonstrating no additional benefits to extension of SAP duration [

25] and our AMS efforts, there was only a modest overall reduction in proportion of extended-course SAP either using PPS-defined SAP duration (from 46.1% (2021) to 44.0% (2024)) or actual SAP duration (from 63.7% (2021) to 61.3% (2024)). Clinically significant reduction in actual prescribed SAP duration of >24 hours from 2021 to 2024 was noticeable for plastic/orthopaedic (80.3% to 75%) and gastrointestinal (62.1% to 52.4%) surgeries. Conversely, the proportion of SAP of >24 hours (actual duration) increased from 30% (2021) to 45.5% (2024), emphasizing on the need to further engage surgeons from the cardiothoracic and vascular departments. These findings underscore the value of stratified PPS data in further identifying specialty-specific stewardship gaps in prescribing even within surgical units.

Despite overall progress, a modest reversal in extended-course SAP was observed in 2024, particularly in plastic/orthopaedic and gastrointestinal surgeries—disciplines that consistently account for over 60% of all SAP use (

Figure 4). We also observed a concurrent decrease in surgical inpatients admitted to SGH from 616 (2021) to 488 (2024). These findings prompted us to examine our hospital’s admission data, and we found an 8.9% increase in day surgeries (excluded from inpatient PPS protocol) from 68,062 surgeries in 2021 to 74,109 surgeries in 2024. This increase was also supported by a recent article discussing how evolution in surgical care and shortage of hospital beds have driven demand for shorter hospital stay and an increase in day surgery arthroplasties performed at SGH [

26]. Put together, these results suggest that uncomplicated procedures, typically associated with short-course SAP may be underrepresented in inpatient PPS results. In contrary, patients with more complex and complicated surgeries remain managed as inpatients and surgeons may be more inclined to use extended-course SAP.

While opportunities for further improvement in antibiotic prescribing remain, especially in SAP, we acknowledge that there is overall significant improvement in antibiotic prescribing patterns over time, with the implementation of the enhanced multi-pronged AMS strategies since 2021. This improvement was made possible only with an effective AMS program, led and supported by hospital senior leaders. Continued engagement with surgical units is essential for sustained and further improvements in antibiotic use.

Garnering Hospital Leadership Support

Securing continued support from hospital senior leadership is vital to the success of any AMS program. Leadership advocacy facilitates the allocation of adequate resources, infrastructure, and authority to the AMS program, which would empower it to effectively design and drive strategies [

27]. At our institution, the governance structure enables the Chief Quality Officer and Chairman of Medical Board to provide direct oversight of the AMS program. This enabled us to designate hospital pharmacists as full time AMS pharmacists and appoint a full-time executive to manage administrative functions. Financial resources were also allocated to build infrastructure critical to AMS efforts. For example, we secured buy-in from senior leaders to develop the

ABxSG app and various IT-tools (e.g. CDSS, development of real-time reports/dashboards) to facilitate appropriate antibiotic prescribing and surveillance.

Furthermore, adequate authority was granted to the AMS team to influence antibiotic prescribing at a higher level. For example, the AMS team could propose/change KPI that impacts prescribers’ bonus payout. In addition, the AMS team was encouraged to, and they were given the support to actively engage surgeons to improve antibiotic use (e.g. through educational roadshows, project collaboration, regular quarterly HOD reports). Additionally, open endorsement of leadership advocacy within the institution was critical in demonstrating that the institution values and prioritises AMS initiatives. In the World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week in 2022, the hospital Chief Executive Officer and Chairman of Medical Board were featured as champions of AMS in the “Friends of AMS” campaign alongside with prominent surgeons of the hospital; their endorsements were posted on institution social media (Instagram and Workplace) and hospital intranet. While strong leadership support has enabled the AMS program to approach surgical teams with confidence, it is equally important for the AMS program to adopt behavioural change models, when designing effective and sustainable AMS initiatives to engage surgeons [

28].

Understanding Surgical Prescribing Culture

The challenge of optimizing antibiotic use in surgical inpatients has been well described locally and globally [

13,

29] and may stem from differences in antibiotic decision-making between medical doctors and surgeons. Hence, the enhanced AMS strategies introduced at SGH between 2021 to 2024 were designed to address the culture and behaviours unique to surgical teams, which may differ even across surgical specialties.

Surgeons as Individualists

Unlike the more collectivist decision-making observed in medical teams, surgical teams tend to follow an individualist approach with the surgeon influencing decision-making [

30]. Therefore, engaging senior surgeons directly was our priority. Senior surgeons were positioned as AMS champions, serving as role models for junior surgeons. AMS strategies focused on involving surgeons in annual roadshows and collaborations in clinical guideline revisions/quality improvement projects was key in promoting shared ownership of stewardship goals and driving effective change in antibiotic prescribing habits.

For instance, in urology, a quality improvement initiative between AMS unit, Urology and Infectious Diseases departments, updated in-house guidelines to replace extended-course SAP with single-dose ceftriaxone for transperineal prostate biopsy. This update subsequently led to a reduction in unnecessary extended SAP from 83% to 21% post implementation (unpublished data).

Carrot and the Stick

Antibiotic stewardship is often viewed as peripheral to surgical management, as surgeons are primarily focused on surgical outcomes. Postoperative uncertainty and fear of SSI can drive defensive prescribing, often resulting in surgeons choosing an extended-course SAP. Besides various project collaboration, we had the support of hospital senior leadership to integrate antibiotic prescribing performance into surgical departmental KPIs to strengthen and incentivise accountability, which was pertinent in driving behavioural change among surgeons.

Bridging the Communication Gaps

Charani et al. further noted that time constraints during ward rounds due to scheduling of surgeries may lead to inadequate communication about antibiotic plans [

30]. At SGH, this was observed from the low documentation rates of antibiotic indication and plans for review or discontinuation, in the PPS findings. To mitigate this, quarterly reports to surgical departments now include trends on these indicators, along with feedback to improve antibiotic-related documentation. In addition, the

ABxSG mobile application supported rapid, time-sensitive decision making by providing easily accessible SAP guidelines in the fast-paced surgical setting.

Strengths of PPS

Compared to other stewardship surveillance tools, PPS offers distinct advantages in the evaluation of AMS performance. While PAF is a cornerstone AMS strategy at SGH, it is resource intensive and typically focused on treatment with selected broad-spectrum antibiotics. In contrast, PPS provides a snapshot of antibiotic prescribing practices (including use of narrower-spectrum antibiotics and surgical prophylaxis) and enables AMS program to narrow down targets of interventions.

Other metrics such as Days of Therapy (DOT) or Defined Daily Doses (DDD) offer valuable antibiotic consumption but require robust electronic health record systems and lack insight into prescribing practices. By capturing indicators such as documentation, guideline adherence and SAP duration, PPS enables institutions to target AMS interventions, set benchmarks and monitor progress effectively. Therefore, PPS should be advocated both in resource-low or resource-rich settings to identify targets of AMS interventions and evaluate the effectiveness of AMS initiatives.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, day surgeries are excluded as these are ambulatory care patients and inpatient PPS is unable to capture the full prescribing patterns for surgical units. With the recent introduction of outpatient PPS module (with inclusion of day surgeries) by the Global PPS team, we intend to conduct the outpatient PPS in the coming years to capture a more comprehensive antibiotic prescribing data within the hospital. Of note, the outpatient PPS module defines SAP duration based on “planned antibiotic duration” instead of a “snapshot duration”, which will significantly increase the accuracy of SAP duration during data collection.

Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of PPS may not capture day-to-day variability. For example, surgeons who routinely prescribe extended SAP-course practices may have been off-duty on survey days. Additionally, observed improvements may be confounded by external factors such as changes to staffing or training that is not initiated by the AMS unit. The potential impact of these limitations can be minimised by a longitudinal comparison across multiple surveys.

Thirdly, the PPS methodology is also limited in resolution. While the information collected offer general insight into prescribing practices, other detailed information on the specific surgical procedures or type of infection was not documented. For example, both laminectomy and knee arthroplasty are categorised as plastic/orthopaedic surgeries but may differ in surgeons’ prescribed duration of SAP.

Fourthly, the original Global-PPS protocol captures SAP duration as of the survey date (PPS-defined duration), rather than the full intended or completed duration, which may lead to under-representation of the actual SAP duration received by the patients.

Lastly, while increasing the number of PPS done per year could provide better insight into prescribing gaps in a timelier manner, PPS could only be conducted once yearly at our 2000-bed institution as it is resource intensive. Recent studies have explored the use of innovation to develop partial or fully automated surveillance systems to collect information on antibiotic indication and healthcare-associated infections [

31,

32]. These solutions will certainly aid in facilitating more regular surveys to have a deeper understanding of changes in surgeons’ practice following implementation of specific strategies over time. Hence, it is pertinent for us to explore innovative solutions to facilitate more regular surveys.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that targeted multi-pronged AMS strategies can improve antibiotic prescribing over time by reducing the proportion of patients prescribed with antibiotics and the use of extended-course SAP, alongside improvement in appropriate documentation and guideline compliance. PPS is a useful tool to identify targets of interventions and to evaluate the effectiveness of AMS strategies. The study results also reinforce the importance of targeted, multidisciplinary AMS interventions tailored to different behaviours and cultures in surgical settings. Despite the gains achieved, continued efforts are necessary to sustain improvements and address persistent barriers, particularly in high-volume surgical specialties.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge our members of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Unit at Singapore General Hospital for their invaluable contributions towards the annual point prevalence surveys and the implementation of our AMS strategies, without which this study would not have been made possible. In particular, we thank our Infectious Disease doctors, Dr Maciej Piotr Chlebicki, Dr Benjamin Cherng Pei Zhi, Dr Thien Siew Yee and Dr Cherie Si Le Gan. We also thank the surgical departments, especially their AMS champions for their engagement in our quality improvement initiatives.

Appendix

Table A1.

Proportion of Surgical Inpatients Prescribed Extended-course (>24 hours) Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis.

Table A1.

Proportion of Surgical Inpatients Prescribed Extended-course (>24 hours) Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis.

| Point Prevalence Survey |

27 April 2021 |

20 January 2022 |

14 February 2023 |

6 March 2024 |

| SAP duration > 24 hours |

Actual (%) |

PPS-defined (%) |

No. of surgeries |

Actual (%) |

PPS-defined (%) |

No. of surgeries |

Actual (%) |

PPS-defined (%) |

No. of surgeries |

Actual (%) |

PPS-defined (%) |

No. of surgeries |

| Plastic/Orthopaedic |

37 (80.4) |

24 (52.2) |

46 |

33 (70.2) |

27 (57.4) |

47 |

24 (61.5) |

17 (43.6) |

39 |

21 (75.0) |

16 (57.1) |

28 |

| Central Nervous Systems |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

1 (25.0) |

1 (25.0) |

4 |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 |

| Cardiac/Vascular |

3 (30.0) |

3(30.0) |

10 |

4 (40.0) |

3 (30.0) |

10 |

5 (35.7) |

2 (14.3) |

14 |

5 (45.5) |

1 (9.1) |

11 |

| Ear, Nose, Throat |

1 (33.3) |

1 (33.3) |

3 |

2 (40.0) |

1 (20.0) |

5 |

3 (60.0) |

3 (60.0) |

5 |

2 (100.0) |

2 (100.0) |

2 |

| Gastrointestinal |

18 (62.1) |

14 (48.3) |

29 |

6 (40.0) |

6 (40.0) |

15 |

9 (47.4) |

6 (31.6) |

19 |

11 (52.4) |

7 (33.3) |

21 |

| Obstetrics/Gynaecological |

4 (100.0) |

4 (100.0) |

4 |

5 (55.6) |

4 (44.4) |

9 |

3 (60.0) |

3 (60.0) |

5 |

6 (66.7) |

6 (66.7) |

9 |

| Respiratory |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 |

3 (75.0) |

3 (75.0) |

4 |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

| Urological |

2 (33.3) |

1 (16.7) |

6 |

8 (61.5) |

7 (53.8) |

13 |

4 (57.1) |

3 (42.9) |

7 |

1 (33.3) |

1 (33.3) |

3 |

| Total |

65 (63.7) |

61 (46.1) |

102 |

61 (59.2) |

51 (49.5) |

103 |

48 (52.2) |

35 (37.6) |

93 |

46 (61.3) |

33 (44.0) |

75 |

Table A2.

Point Prevalence Survey Quality Indicators for Surgical Inpatients (2021-2024).

Table A2.

Point Prevalence Survey Quality Indicators for Surgical Inpatients (2021-2024).

| Point Prevalence Survey |

27 April 2021 |

20 January 2022 |

14 February 2023 |

6 March 2024 |

|

Antibiotics Prescribed, no.1

|

516 |

386 |

406 |

351 |

| Documentation of Antibiotic Indication |

360 (69.8) |

285 (73.8) |

308 (75.9) |

284 (80.9) |

| Documentation of Antibiotic Stop/Review Date |

220 (42.6) |

183 (47.4) |

195 (48.0) |

185 (52.7) |

|

Guideline Compliance, no (%)2

|

366 (82.1) |

282 (80.8) |

307 (80.4) |

262 (84.8) |

|

Guidelines not available or Unknown Indication, no.3

|

70 |

37 |

24 |

42 |

References

- Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. World Health Organization; 2016. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/193736/9789241509763_eng.pdf.

- Dyar OJ, Huttner B, Schouten J, Pulcini C. What is antimicrobial stewardship? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(11):793-798. [CrossRef]

- Parker H, Frost J, Day J, et al. Tipping the balance: A systematic review and meta-ethnography to unfold the complexity of surgical antimicrobial prescribing behavior in hospital settings. PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0271454. [CrossRef]

- Tourmousoglou CE, Yiannakopoulou EC, Kalapothaki V, Bramis J, Papadopoulos JS. Adherence to guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in general surgery: a critical appraisal. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;61(1):214-218. [CrossRef]

- Aldeyab MA, Kearney MP, McELNAY JC, et al. A point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in four acute-care teaching hospitals utilizing the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC) audit tool. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(9):1714-1720. [CrossRef]

- Versporten A, Zarb P, Caniaux I, et al. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(6):e619-e629. [CrossRef]

- Chua AQ, Kwa ALH, Tan TY, Legido-Quigley H, Hsu LY. Ten-year narrative review on antimicrobial resistance in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2019;60(8):387-396. [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Division. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Health-Care Facilities in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A WHO Practical Toolkit. World Health Organization; 2019. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/329404/9789241515481-eng.pdf.

- Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. [CrossRef]

-

Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Health Care Full Publication. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2018. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/202307/antimicrobial_stewardship_in_australian_health_care_-_july_2023_up_to_chapter_20.pdf.

- Loo L, Lee W, Chlebicki P, Kwa AL. Implementing national antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP): Our Singapore story. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(suppl_1). [CrossRef]

- Chung W, Shafi H, Seah J, et al. National surgical antibiotic prophylaxis guideline in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51:695-711.

- Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017 JAMA Surg 2017;152:784-91. JAMA Surg.2017;152.

-

Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. World Health Organization; 2018. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/277399/9789241550475-eng.pdf.

- Phillips BT, Sheldon ES, Orhurhu V. Preoperative Versus Extended Postoperative Antimicrobial Prophylaxis of Surgical Site Infection During Spinal Surgery: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37:2710-2733.

- National Healthcare Safety Network. Procedure-Associated Module: Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI). Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Accessed January 5, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf.

- Chun Lim SY, Wei Lee L, Yvonne Zhou P, et al. 503. Antibiotic mobile application ABxSG - an innovative and effective antibiotic stewardship tool that improves antibiotic use and reduces healthcare costs. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2025;12(Supplement_1). [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Núñez M, Perez-Galera S, Girón-Ortega JA, et al. Predictors of inappropriate antimicrobial prescription: Eight-year point prevalence surveys experience in a third level hospital in Spain. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Zarb P, Amadeo B, Muller A, et al. Identification of targets for quality improvement in antimicrobial prescribing: the web-based ESAC Point Prevalence Survey 2009. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(2):443-449. [CrossRef]

- Zarb P, Goossens H. European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): Value of a point-prevalence survey of antimicrobial use across Europe. Drugs. 2011;71(6):745-755. [CrossRef]

- Lim JL, Yii DYC, Hung KC, et al. 815. Short-course vs. Extended-course perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in patients receiving unilateral primary total knee arthroplasty. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(Supplement_1):S500-S501. [CrossRef]

- Li Ling Lim C, Chua NG, Lim FK, et al. A single-centre retrospective study on the impact of reducing surgical prophylaxis from 48 hours to 24 hours in cardiothoracic surgery. EMJ Int Cardiol. Published online 2022:37-46. [CrossRef]

- Hung KC, Chung SJ, Kwa AL, Lee WHL, Koh YX, Goh BKP. Surgical prophylaxis in pancreatoduodenectomy: Is cephalosporin still the drug of choice in patients with biliary stents in situ? Pancreatology. 2024;24(6):960-965. [CrossRef]

- Effect of postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis on the incidence of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis de Jonge, Stijn W et al. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20:1182-1192.

- Lim JBT, Xu S, Abdullah HR, Pang HN, Yeo SJ, Chen JYQ. Enhanced recovery after surgery: Singapore General Hospital arthroplasty experience. Singapore Med J. Published online 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dellit TH, Owens RC, Mcgowan JE, Gerding DN, Weinstein RA, Burke JP. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159-177. [CrossRef]

- Lorencatto F, Charani E, Sevdalis N, Tarrant C, Davey P. Driving sustainable change in antimicrobial prescribing practice: how can social and behavioural sciences help? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(10):2613-2624. [CrossRef]

- Borg MA. Prolonged perioperative surgical prophylaxis within European hospitals: an exercise in uncertainty avoidance? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(4):1142-1144. [CrossRef]

- Charani E, Ahmad R, Rawson TM, Castro-Sanchèz E, Tarrant C, Holmes AH. The differences in antibiotic decision-making between acute surgical and acute medical teams: An ethnographic study of culture and team dynamics. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(1):12-20. [CrossRef]

- Sakai M, Sakai T, Watariguchi T, Kawabata A, Ohtsu F. Development and validation of an automated antimicrobial surveillance system based on indications for antimicrobial administration. J Infect Chemother. 2025;31(1):102472. [CrossRef]

- Verberk JDM, Aghdassi SJS, Abbas M, et al. Automated surveillance systems for healthcare-associated infections: results from a European survey and experiences from real-life utilization. J Hosp Infect. 2022;122:35-43. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).