Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The Urgency of Acute Aortic Syndromes

Purpose of the Review

Methods

Approach to Evidence Synthesis

Literature Search

Study Selection

Results

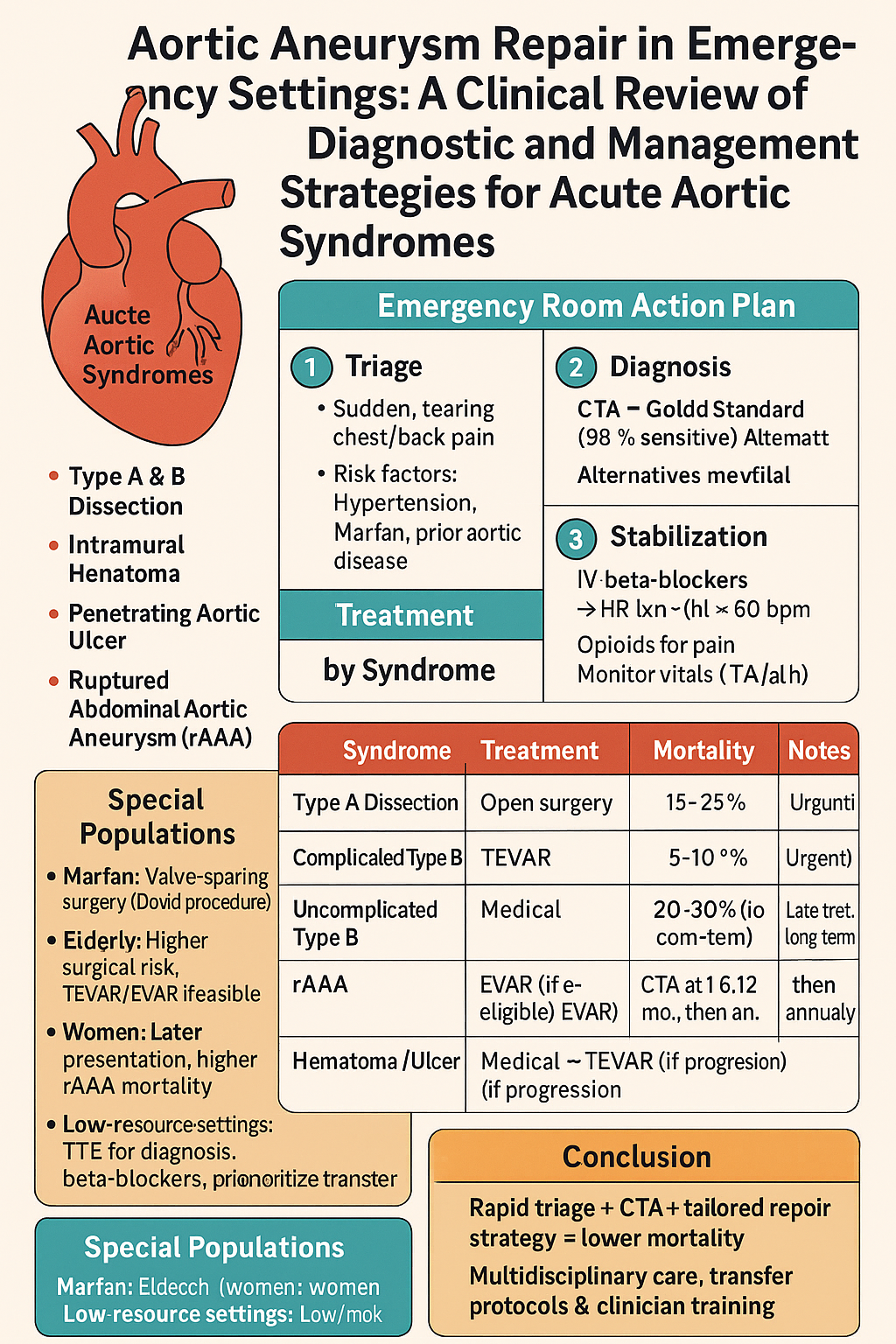

Clinical Approach to AAS in the Emergency Room

Initial Presentation and Triage

- Triage: Assign to a high-acuity area for immediate assessment.

- History: Evaluate pain characteristics, onset, and risk factors (e.g., hypertension, connective tissue disorders).

- Physical Exam: Check for pulse deficits, blood pressure asymmetry (>20 mmHg between arms), or new murmurs (e.g., aortic regurgitation in type A dissection).

Stabilization

Action Steps:

- Hemodynamic Control: Administer intravenous beta-blockers (e.g., esmolol, 0.1–0.5 mg/kg bolus, then 50–200 µg/kg/min infusion) targeting heart rate <60 bpm and systolic blood pressure 100–120 mmHg. Use calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem) if beta-blockers are contraindicated.

- Pain Management: Provide opioids (e.g., morphine 2–4 mg IV) to reduce pain and sympathetic drive.

- Monitoring: Use cardiac monitor, arterial line, and pulse oximetry to track vital signs.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Action Steps:

- Primary Imaging: Order CTA of chest, abdomen, and pelvis to identify dissection flap, hematoma, or ulcer, and assess extent (type A vs. B).

- Alternative Imaging: Use TEE in hemodynamically unstable patients or bedside transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) to detect complications (e.g., aortic regurgitation, tamponade).

- Laboratory Tests: Obtain complete blood count, renal function, lactate, and D-dimer (elevated in 95% of AAS cases) to assess organ perfusion and rule out other diagnoses [1].

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Advantages | Limitations |

| CTA | 98 | 95 | Rapid, widely available | Radiation, contrast risk |

| TEE | 90 | 95 | Bedside, no contrast | Operator-dependent |

| MRA | 95 | 90 | No radiation | Time-consuming, limited access |

Management Strategies by AAS Type

Overview

Type A Aortic Dissection

Action Steps:

- Consultation: Immediately involve cardiothoracic surgery and transfer to a center with aortic expertise.

- Surgical Technique: Replace the ascending aorta with a Dacron graft. For aortic root involvement, use a Bentall procedure (composite valve-graft) or valve-sparing David procedure in younger patients or those with Marfan syndrome [8].

- Outcomes: 30-day mortality is 15–25%, with stroke rates of 5–10%. Malperfusion (e.g., mesenteric, renal) increases mortality to 30% [9].

- Non-Operative: Reserved for prohibitive comorbidities (e.g., advanced age, severe stroke); in-hospital mortality is 39% [10].

Type B Aortic Dissection

Action Steps:

- ●

- Complicated Type B:

- ○

- Consult Vascular Surgery: Plan urgent TEVAR to seal the entry tear and restore perfusion.

- ○

- Technique: Deploy a stent-graft via femoral access, targeting a proximal landing zone. Operative time is 90–120 minutes [12].

- ○

- Outcomes: 30-day mortality is 5–10%, with endoleak rates of 5–15% and reintervention rates of 10–15% at 5 years [13].

- ●

- Uncomplicated Type B:

- ○

- Medical Management: Continue beta-blockers and monitor with serial CTA. Long-term mortality is 20–30% [14].

- ○

- Indications for TEVAR: Persistent pain, uncontrolled hypertension, or aneurysm expansion (>5.5 cm).

Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (rAAA)

Action Steps:

- Stabilization: Use permissive hypotension (systolic BP ~80 mmHg) to minimize bleeding until repair.

- Consult Vascular Surgery: Assess EVAR eligibility (e.g., adequate neck length, no tortuosity).

- Technique: EVAR uses stent-graft placement via femoral access; open repair requires laparotomy and aortic clamping.

- Outcomes: EVAR has 15–20% 30-day mortality vs. 30–40% for open repair. Women and octogenarians have higher mortality (up to 40%) [4].

Intramural Hematoma and Penetrating Aortic Ulcer

Action Steps:

- ●

- Intramural Hematoma:

- ○

- Initial Management: Use beta-blockers and serial CTA every 48 hours.

- ○

- Surgical Indications: Progression to dissection, rupture, or persistent pain. TEVAR is preferred for descending aorta involvement.

- ○

- Outcomes: 15–20% mortality with medical management; 5–7% with TEVAR [17].

- ●

- Penetrating Aortic Ulcer:

- ○

- Technique: TEVAR for symptomatic or enlarging ulcers, with 95% technical success.

- ○

- Outcomes: 5% 30-day mortality, 2–5% reintervention at 3 years [18].

| AAS Type | Preferred Treatment | 30-Day Mortality (%) | Key Complications |

| Type A Dissection | Open Repair | 15–25 | Stroke (5–10%), Malperfusion |

| Type B Dissection (Complicated) | TEVAR | 5–10 | Endoleak (5–15%) |

| Type B Dissection (Uncomplicated) | Medical | 20–30 (long-term) | Progression to Complicated |

| rAAA | EVAR | 15–20 | Endoleak, Reintervention |

| Intramural Hematoma | Medical/TEVAR | 5–20 | Progression to Dissection |

| Penetrating Aortic Ulcer | TEVAR | 5–7 | Reintervention (2–5%) |

Postoperative Care

Overview

Monitoring and Support

Action Steps:

- Hemodynamics: Maintain systolic blood pressure 100–120 mmHg using beta-blockers or vasodilators (e.g., nitroprusside). Monitor for malperfusion via lactate and renal function tests.

- Respiratory Support: Ventilate patients post-open repair for 24–48 hours, weaning as tolerated. TEVAR/EVAR patients may require shorter ventilation [20].

- Neurologic Assessment: Monitor for stroke or spinal cord ischemia (1–3% risk with TEVAR), using serial neurologic exams [21].

Complication Management

Action Steps:

- Bleeding: Transfuse packed red blood cells for hemoglobin <7 g/dL. Use fresh frozen plasma for coagulopathy post-open repair [22].

- Endoleaks: Monitor TEVAR/EVAR patients with CTA at 1 month. Type I endoleaks require urgent reintervention; type II may be observed [23].

- Renal Failure: Initiate dialysis for acute kidney injury (10–20% risk post-open repair) [24].

Follow-Up

Action Steps:

- Medical Therapy: Continue beta-blockers indefinitely to reduce aortic wall stress. Statins and antihypertensives improve long-term survival [25].

Action Steps:

- Surgical Preference: Favor valve-sparing David procedures to avoid prosthetic valve complications [8].

- Outcomes: Higher reintervention rates (10–15% at 10 years) due to progressive aortic dilatation [27].

- Genetic Counseling: Refer for genetic testing and family screening post-stabilization.

- Elderly Patients

Action Steps:

Women

Action Steps:

Management in Resource-Limited Settings

Challenges

Action Steps:

- Diagnosis: Use TTE if CTA/TEE is unavailable, focusing on aortic root dilatation or pericardial effusion [34].

- Stabilization: Rely on widely available beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol) and opioids for pain control.

- Treatment: Transfer to a tertiary center for surgery. If transfer is delayed, prioritize medical management for uncomplicated type B dissection or intramural hematoma [35].

- Training: Educate ER staff on AAS recognition to reduce misdiagnosis, using clinical decision tools (e.g., ADD-RS score) [36].

Multidisciplinary Care and Transfer

Team Approach

Action Steps:

Discussion

Conclusions

- For a patient with suspected AAS in the ER, clinicians should:

- Triage rapidly, assessing chest/back pain and risk factors.

- Stabilize with beta-blockers and permissive hypotension (for rAAA).

- Confirm diagnosis with CTA or TEE.

- Select treatment: open repair for type A, TEVAR for complicated type B or penetrating ulcers, EVAR for rAAA, medical management for select cases.

- Provide ICU monitoring and long-term follow-up.

Data Availability

Reporting Guidelines

Ethics and Consent

Competing Interests

Grant Information

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Hagan, P.G.; Nienaber, C.A.; Isselbacher, E.M.; et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): New insights into an old disease. JAMA 2000, 283, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isselbacher, E.M.; Preventza, O.; Black, J.H.; et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease. Circulation 2022, 146, e334–e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovatt, S.; Ho, K.M.; Wong, Z.H.; et al. Acute aortic syndromes: An opportunity to improve. BMJ 2024, 386, bmj–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Goncalves, F.B.; et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbel, R.; Aboyans, V.; Boileau, C.; et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2873–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilacosta, I.; San Román, J.A.; Aragoncillo, P.; et al. Acute aortic syndrome: A new look at an old conundrum. Heart 2009, 95, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaria, J.E.; Pochettino, A.; Brinster, D.R.; et al. New paradigms and improved results for the surgical treatment of acute type A dissection. Ann. Surg. 2002, 236, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, T.E.; Feindel, C.M. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1992, 103, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimarchi, S.; Nienaber, C.A.; Rampoldi, V.; et al. Contemporary results of surgery in acute type A aortic dissection: The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection experience. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 140, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, L.A.; Awais, M.; Woznicki, E.M.; et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of acute aortic dissection: 17-year trends from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, C.A.; Kische, S.; Rousseau, H.; et al. Endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection: Long-term results of the randomized investigation of stent grafts in aortic dissection trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, W.Y.; McGarvey, M.; Pochettino, A.; et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair for acute complicated type B aortic dissection: Superiority relative to conventional open surgical and medical therapy. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 140, S109–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattori, R.; Tsai, T.T.; Myrmel, T.; et al. Complicated acute type B dissection: Is surgery still the best option? Interv. 2008, 1, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, T.T.; Fattori, R.; Trimarchi, S.; et al. Long-term survival in patients presenting with type B acute aortic dissection: Insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation 2006, 114, 2226–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMPROVETrial Investigators Endovascular or open repair strategy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: 30-day outcomes from Improver and omised trial, B. M.J 2014, 348, f7661. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, A.; Czerny, M.; Nienaber, C.; et al. Acute intramural hematoma of the aorta: A mystery in evolution. Circulation 2018, 137, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.K.; Kim, H.S.; Kang, D.H.; et al. Outcomes of medically treated patients with aortic intramural hematoma. Am. J. Med. 2002, 113, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittle, S.L.; Lynch, R.J.; Cole, P.E.; et al. Midterm follow-up of penetrating ulcer and intramural hematoma of the aorta. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002, 123, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambria, R.P.; Crawford, R.S.; Cho, J.S.; et al. Surgical management of acute aortic dissection: New data. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2000, 12, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaby, S.; Saito, S.; Katsumata, T. Acute type A dissection: Is surgery always necessary? Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002, 124, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossone, E.; LaBounty, T.M.; Eagle, K.A. Stroke and outcomes in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Circulation 2013, 128, S175–S179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampoldi, V.; Trimarchi, S.; Eagle, K.A.; et al. Simple risk models to predict surgical mortality in acute type A aortic dissection: The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection score. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 83, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veith, F.J.; Baum, R.A.; Ohki, T.; et al. Nature and significance of endoleaks and endotension: Summary of opinions expressed at an international conference. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002, 35, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, N.D.; Ganapathi, A.M.; Hanna, J.M.; et al. Impact of acute kidney injury on outcomes of type A aortic dissection repair. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Mehta, R.H.; Ince, H.; et al. Clinical profiles and outcomes of acute type B aortic dissection in the current era: Lessons from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation 2003, 108, II312–II317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansac, E.; Di Centa, I.; Raoux, F.; et al. Aortic root surgery in Marfan syndrome: Comparison of outcomes after valve-sparing and valve-replacing procedures. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 142, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenbach, K.; Oelze, T.; Salcher, R.; et al. Aortic dissection: A 20-year single-center experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004, 78, 1595–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.; Rogers, C.A.; Davies, I.; et al. Outcomes of emergency surgery for acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 149, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, A.; Regesta, T.; Pansini, S.; et al. Octogenarians with uncomplicated acute type A aortic dissection benefit from emergency operation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 96, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Eusanio, M.; Trimarchi, S.; Patel, H.J.; et al. Surgery for acute type A aortic dissection in the elderly: A multicenter study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 1627–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, T.; Pomposelli, F.; Hagberg, R.; et al. Gender differences in outcomes after emergency repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 59, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylski, B.; Hoffmann, I.; Beyersdorf, F.; et al. Gender-related differences in outcomes after repair of acute type A aortic dissection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 99, 2031–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Bis, K.G.; Glover, J.L.; et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers of the aorta: A 15-year experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1994, 58, 1160–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coady, M.A.; Rizzo, J.A.; Hammond, G.L.; et al. Natural history of penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers and intramural hematomas of the aorta. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 116, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.B.; Ubbink, D.T.; van der Vliet, J.A. Outcome after surgical and endovascular intervention in patients with penetrating aortic ulcer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2007, 31, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratzka, L.F.; Bakris, G.L.; Beckman, J.A.; et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. Circulation 2010, 121, e266–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerny, M.; Schoenhoff, F.; Etz, C.; et al. Current options and recommendations for the treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies involving the aortic arch: An expert consensus document of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.J.; Williams, D.M.; Upchurch, G.R.; et al. Operative delay in acute type A dissection: Risky or safe? Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, F.H.; Trimarchi, S.; Verhagen, H.J.; et al. Endovascular repair of ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysms: A systematic review. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 52, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, M.J.; Ulug, P.; Powell, J.T.; et al. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: Endovascular repair does not confer any long-term survival advantage over open repair. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimerink, J.J.; Hoornweg, L.L.; Vahl, A.C.; et al. Endovascular repair versus open repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, M.D.; Kato, N.; Mitchell, R.S.; et al. Endovascular stent-grafting for descending thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabenwöger, M.; Alfonso, F.; Bachet, J.; et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for the treatment of aortic diseases: A position statement from the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012, 42, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggebrecht, H.; Nienaber, C.A.; Neuhäuser, M.; et al. Endovascular stent-graft placement in aortic dissection: A meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.Y.; Eagle, K.A.; Vaishnava, P. Acute type B aortic dissection: Surgical or endovascular intervention? Thorac. Surg. 2008, 86, 1749–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, K.; Björck, M.; Lundkvist, J.; et al. Treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm in nine countries 2005-2009: A vascunet report. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 42, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermerhorn, M.L.; O’Malley, A.J.; Jhaveri, A.; et al. Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, R.M.; Brown, L.C.; Powell, J.T.; et al. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Freischlag, J.A.; Kyriakides, T.C.; et al. Outcomes following endovascular vs open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: A randomized trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, J.C.; Palmaz, J.C.; Barone, H.D. Transfemoral intraluminal graft implantation for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 5, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riambau, V.; Böckler, D.; Brunkwall, J.; et al. Editor’s choice – Management of descending thoracic aorta diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 53, 4–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, G.R.; Escobar, G.A.; Azizzadeh, A.; et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for endovascular treatment of acute and chronic thoracic aortic disease. J Vasc Surg 2018, 68, 91S–114S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipp, B.S.; Deeb, G.M.; Prager, R.L.; et al. Impact of hospital volume on outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodney, P.P.; Travis, L.L.; Nallamothu, B.K.; et al. Hospital volume, surgeon volume, and outcomes of aortic aneurysm repair in the VQI. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 63, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Holt, P.; et al. Endovascular versus open repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: The IMPROVE trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016, 52, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgranges, P.; Kobeiter, H.; Katsahian, S.; et al. A randomised trial comparing endovascular and open repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (ECAR). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015, 50, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkos, C.D.; Harkin, D.W.; Giannakou, A.; et al. Emergency endovascular aneurysm repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 41, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buth, J.; Harris, P.L.; van Marrewijk, C. Outcome of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients with conditions considered unfit for an open procedure: A report on the EUROSTAR experience. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002, 35, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.L.; Buth, J.; Mialhe, C.; et al. Incidence and risk factors of late rupture, conversion, and death after endovascular repair of infrarenal aortic aneurysms: The EUROSTAR experience. J. Vasc. Surg. 2000, 32, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leurs, L.J.; Bell, R.; Degrieck, Y.; et al. Endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic diseases: Combined experience from the EUROSTAR and United Kingdom Thoracic Endograft registries. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 40, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, M.P.; Ergin, M.A.; McCullough, J.N.; et al. Results of immediate surgical treatment in patients with acute type A aortic dissection and organ malperfusion. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000, 70, 2014–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.R.; Sundt, T.M.; Pasque, M.K.; et al. Aggressive surgical treatment of acute aortic dissection with organ malperfusion. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2002, 74, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boening, A.; Karck, M.; Conzelmann, L.O.; et al. German registry for acute aortic dissection type A: Structure, results, and future perspectives. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, L.M.; Madsen, J.C.; Isselbacher, E.M.; et al. Late outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for acute type A aortic dissection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 88, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzelmann, L.O.; Weigang, E.; Mehlhorn, U.; et al. Mortality in patients with acute aortic dissection type A: Analysis of pre- and intraoperative risk factors from the German Registry for Acute Aortic Dissection Type A (GERAADA). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 49, e44–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, U.; Melina, G.; Takkenberg, J.J.; et al. Open versus endovascular repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 56, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, L.L.; Storm-Versloot, M.N.; Ubbink, D.T.; et al. Gender differences in outcome after endovascular and open repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2007, 34, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, N.N.; Vouyouka, A.G.; McKinsey, J.F.; et al. National outcomes for the treatment of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: Comparison of open versus endovascular repairs. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinssen, M.; Verhoeven, E.L.; Buth, J.; et al. A randomized trial comparing conventional and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Sweeting, M.J.; Powell, J.T.; et al. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 64, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oderich, G.S.; Forbes, T.L.; Chaikof, E.L.; et al. Evolution of endovascular therapy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malas, M.B.; Arhuidese, I.; Elefteriades, J.; et al. Outcomes of endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 59, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.T.; Sweeting, M.J.; Ulug, P.; et al. Editor’s choice – Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: Endovascular repair improves 30-day outcomes in women. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 54, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oderich, G.S.; Georghiades, G.S.; Chaikof, E.L.; et al. Outcomes of endovascular repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Vascular Quality Initiative. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 70, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattori, R.; Montgomery, D.; Lovato, L.; et al. Acute intramural hematoma of the aorta as a cause of sudden death: A multicenter study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, M.P.; Schillinger, M.; Grabenwöger, M.; et al. Surgical treatment of acute type A dissection: Midterm results. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2002, 73, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geirsson, A.; Bavaria, J.E.; Swarr, D.; et al. Significance of malperfusion syndromes prior to surgical repair of acute type A dissection: Outcomes and risk factors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 84, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerny, M.; Krähenbühl, E.; Reineke, D.; et al. The impact of preoperative malperfusion on outcomes in acute type A aortic dissection: Results from the GERAADA registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2628–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontyev, S.; Borger, M.A.; Davierwala, P.; et al. Redo aortic surgery: Does one versus two stages impact survival? Thorac. Surg. 2018, 105, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrera, A.L.; Miller, C.C.; Safi, H.J.; et al. Acute type A aortic dissection: Surgical intervention or watchful waiting? Thorac. Surg. 2003, 75, 1472–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchoukos, N.T.; Masetti, P.; Murphy, S.F. Management of acute aortic dissection: A focus on surgical techniques. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Impact of gender on outcomes after repair of acute type A aortic dissection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 110, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, A.; Mukherjee, D.; Mehta, R.H.; et al. Long-term outcome of medically treated patients with acute aortic intramural hematoma. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossone, E.; Rampoldi, V.; Nienaber, C.A.; et al. Usefulness of pulse deficit to predict in-hospital complications and mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 89, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.T.; Evangelista, A.; Nienaber, C.A.; et al. Partial thrombosis of the false lumen in patients with acute type B aortic dissection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).