1. Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an aging-related disease, and the larger the size, the higher the risk of rupture. The endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) was first introduced in 1991 as a minimally invasive vascular repair [

1]. Since then, numerous studies have demonstrated the benefits of EVAR compared with conventional open aneurysm repair (OAR). Among them, three significant randomized controlled trials consistently reported that EVAR resulted in a significant reduction in the 30-day mortality [

2,

3,

4]. Because EVAR was reported to reduce 30-day mortality dramatically, there was a significant reduction in the number of OAR subsequently.

These reports led to a shift in the concept of an optimal treatment strategy for patients with AAA. With a dramatic increase in the number of EVAR, several guidelines have reflected this change in concept. Representatively, the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) guidelines emphasized the benefits of EVAR for perioperative mortality and recommended it as the preferred treatment option for anatomically fit AAA patients with 10 10-year life expectancy [

5]. The European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) guidelines proposed the same recommendations [

6]. Therefore, EVAR was considered the primary modality to treat AAA patients who had anatomically suitable AAA.

However, there is no nationwide report on the effect of EVAR on aneurysm-related mortality. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the nationwide trends in annual AAA treatment and aneurysm-related mortality, including ruptured AAA (rAAA) and intact AAA (iAAA) over the past 13 years.

2. Materials and Methods

The data source for the recent 13 year-period analysis was the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), comprising data from 2010-2022. Korea’s public medical insurance system covers almost the entire population of Korea. HIRA is a government-operated organization and healthcare service providers submit claims data to HIRA for reimbursement. Therefore, the HIRA data are national characteristic data of actual patients of Korea [

7]. The HIRA Data Access Committee and Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong Institutional Review Board (IRB no. KHNMC 2015-01-027) approved the use of their data in this study. Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong Institutional Review Board has waived informed consent for this study. All methods were carried out by relevant guidelines, including RECORD guidelines and regulations.

The numbers of patients with AAA were collected using the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases and Causes of Death (KCD-7), as this complementary system is an adaptation of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), to Korean conditions. The codes of I713 and I714 represent rAAA and iAAA, respectively. The annual numbers of OAR and EVAR were collected using the Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) codes. The open repairs of AAA were classified with O0223, O0224, and O2034 for suprarenal AAA, infrarenal AAA, and abdominal aorta involving the iliac artery, respectively. The EDI code for EVAR is allocated with only one code of M6612. The detailed KCD and EDI codes for rAAA, iAAA, and AAA repairs were shown in

Table 1.

The annual AAA-related mortality rate was collected using Statistics Korea. The MicroData Integrated Service (MDIS) of Statistics Korea releases the cause of death due to the specific disease. The causes of death were classified according to the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO). The annual number of death patients with rAAA and iAAA was obtained from the server of MDIS. Then, the annual morality rate due to rAAA and iAAA was calculated by the percentage of death number with the total number of patients with rAAA and iAAA.

For statistical analysis, a linear-by-linear association was performed to determine trends in AAA patients and treatments for this period. The Bland-Altman method was used to evaluate trends in population-adjusted frequencies. We measured the relative risk to evaluate trends using MedCalc Statistical software (Ostend, Belgium). The annual trend of mortality rate was analyzed with Poisson regression analysis using the SPSS version 22.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value less than 0.05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Annual Numbers of rAAA and iAAA

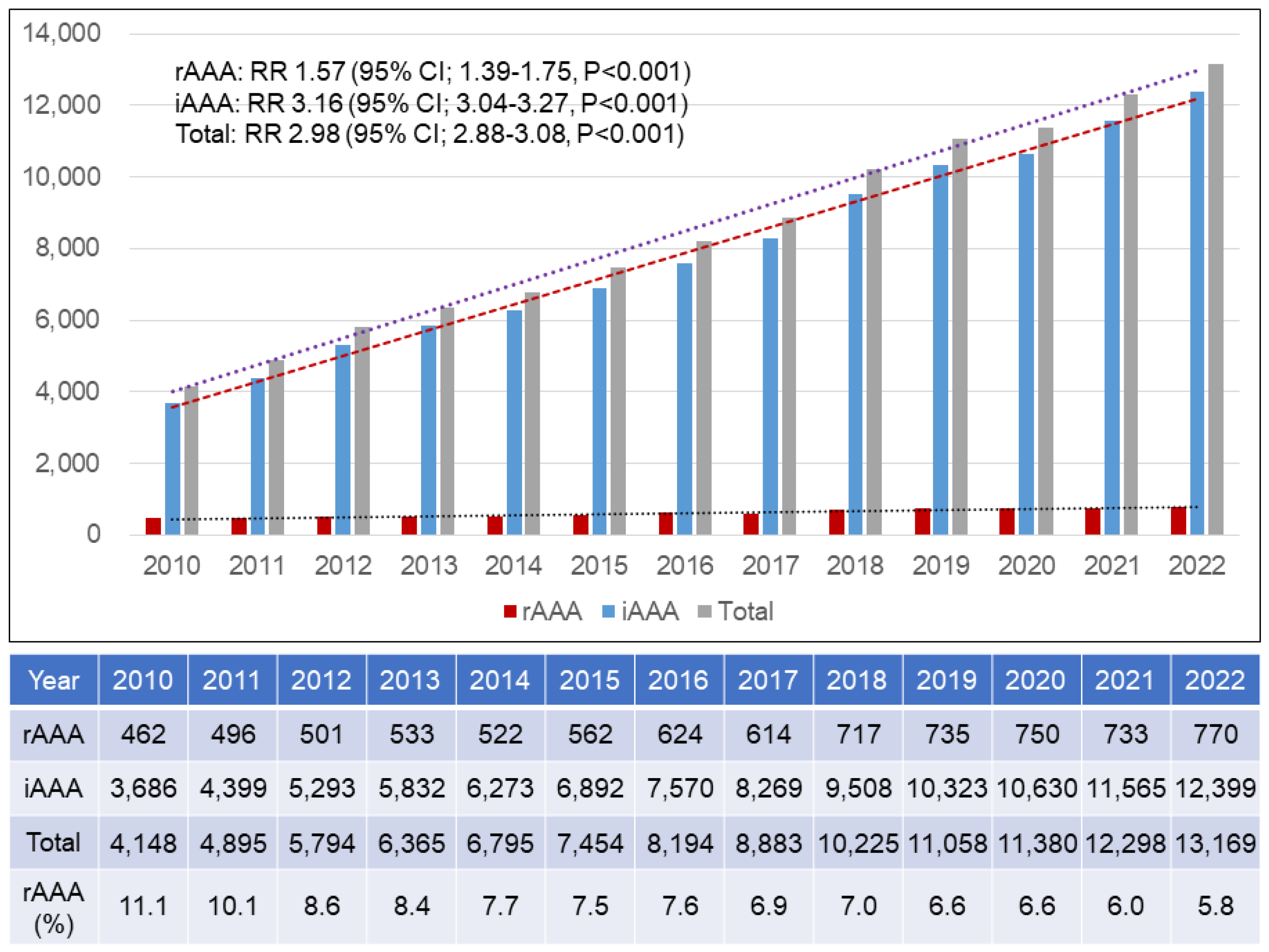

There was a total of 110,658 patients with AAA from 2010 to 2022, of which 8,019 had rAAA while 102,639 had iAAA.

Figure 1 represents the annual number of patients with AAA. The annual number of rAAA patients increased from 462 in 2010 to 770 in 2022 (relative risk, RR 1.57, 95% confidence interval, CI, 1.39-1.75, P<0.001). Compared to rAAA, the annual number of iAAA increased more rapidly from 3,686 in 2010 to 12,399 in 2022 (RR 3.16, 95% CI; 3.04-3.27, P<0.001). The rapid increase in the number of iAAA patients resulted in a 2.98-fold increase in the total number of AAA patients during the study period (RR 2.98, 95% CI 2.88-3.08, P<0.001).

3.2. Gender Distribution

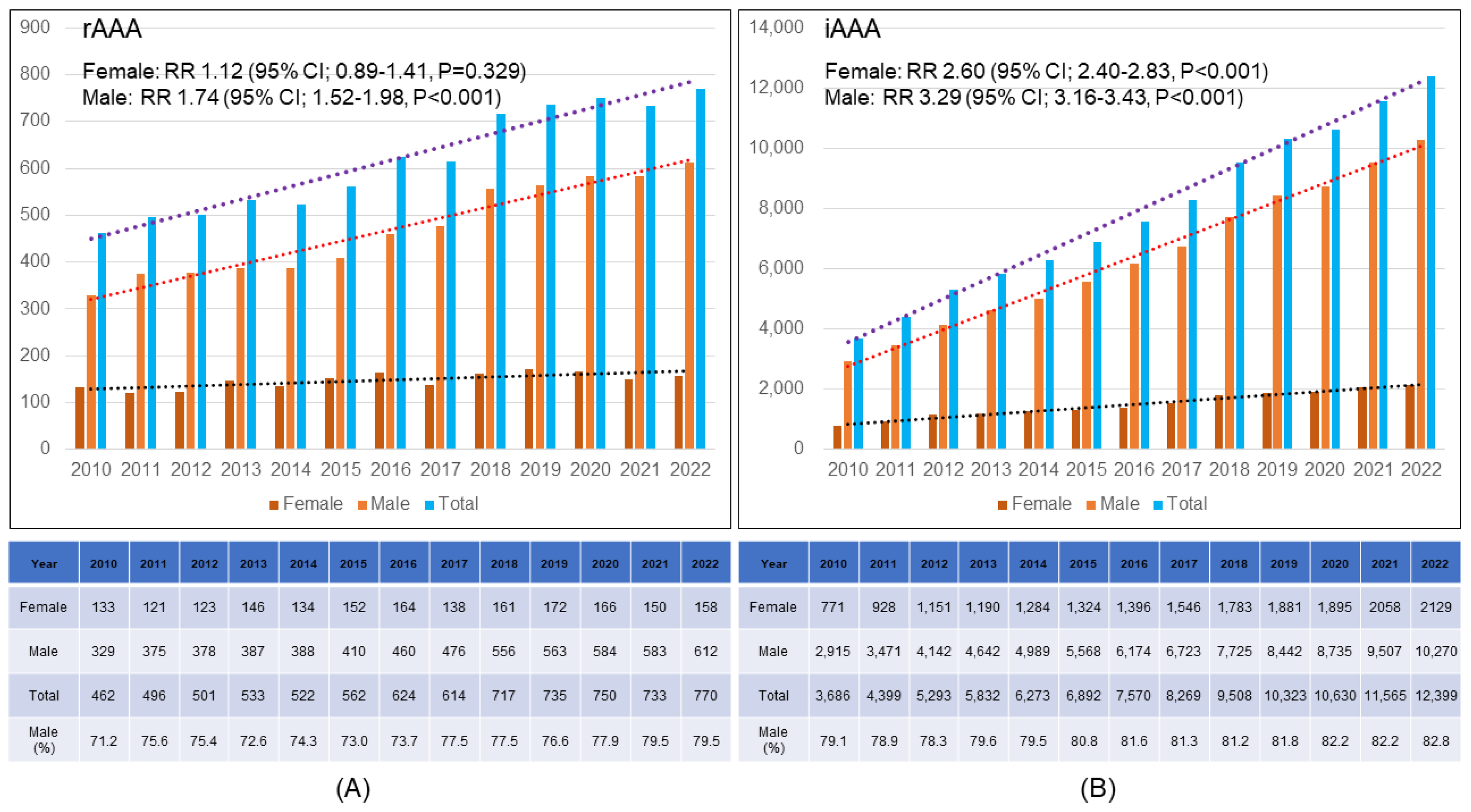

During the study period, the annual number of male rAAA patients increased gradually (RR 1.74, 95% CI; 1.52-1.98, P<0.001), while that of female rAAA patients showed no statistically significant increase (RR 1.12, 95% CI; 0.89-1.41, P=0.329). Therefore, the proportion of male rAAA patients increased from 71.2% in 2010 to 79.5% in 2022 (

Figure 2A).

Figure 2B demonstrates the annual changes in gender distribution of iAAA patients. The annual numbers of male and female iAAA patients increased 3.29-fold and 2.60-fold, with statistical significance (P<.001).

3.3. Age Distribution

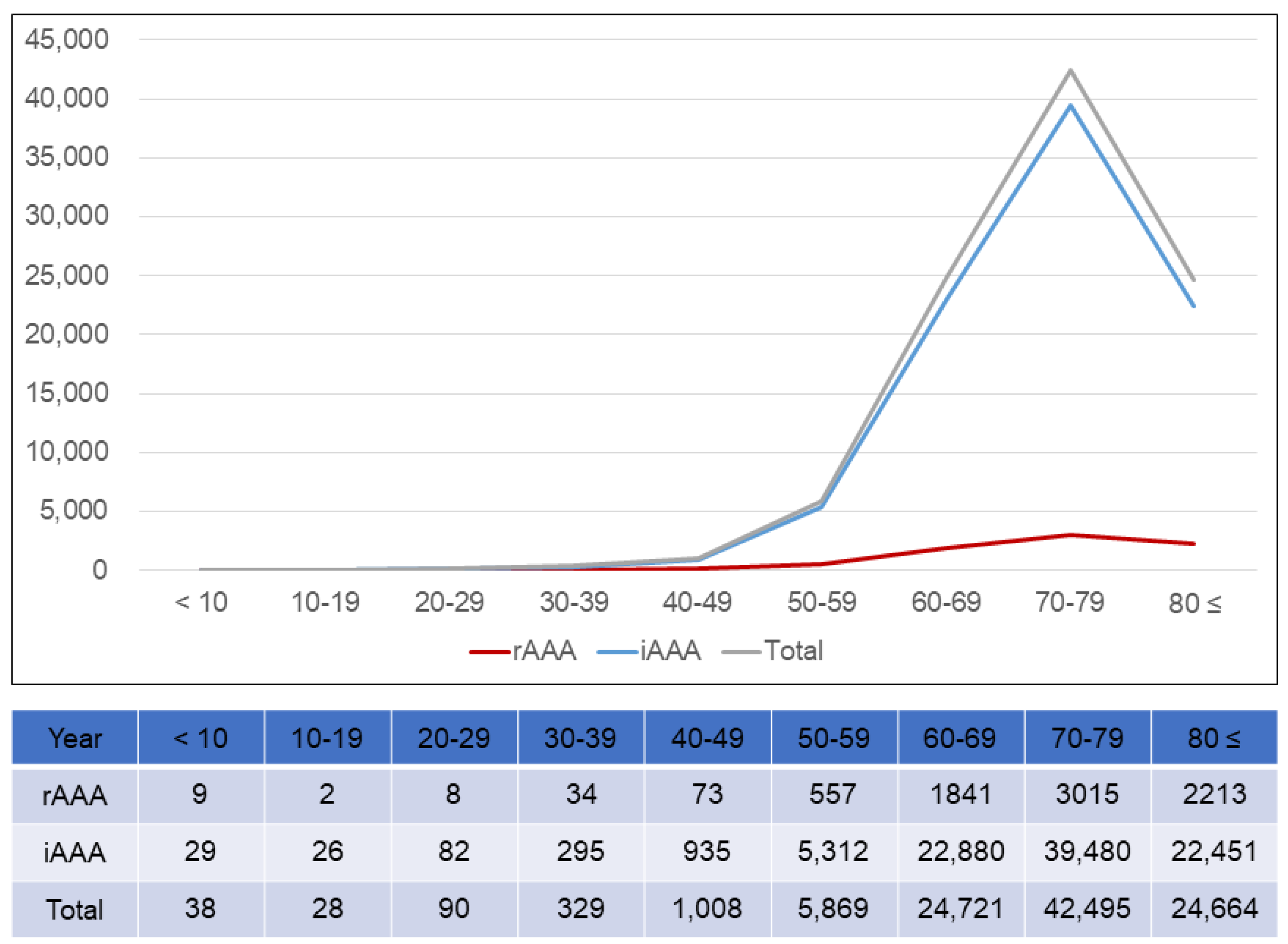

The patients most frequently treated for AAA were those in their 70s, regardless of the presence of rupture (

Figure 3). In the rAAA group, rapid increase was shown in their 60s and peak was demonstrated in their 70s. However, in the iAAA group, rapid increase was shown in their 50s. It was 10 years younger than rAAA group. More rapid increase was shown in their 70s in the iAAA group. In the rAAA, 80s and older ranked second followed by those in their 60s. In the iAAA group, those in their 60s ranked second, followed by those in their 80s or older.

3.4. Annual Trends of EVAR Versus OAR

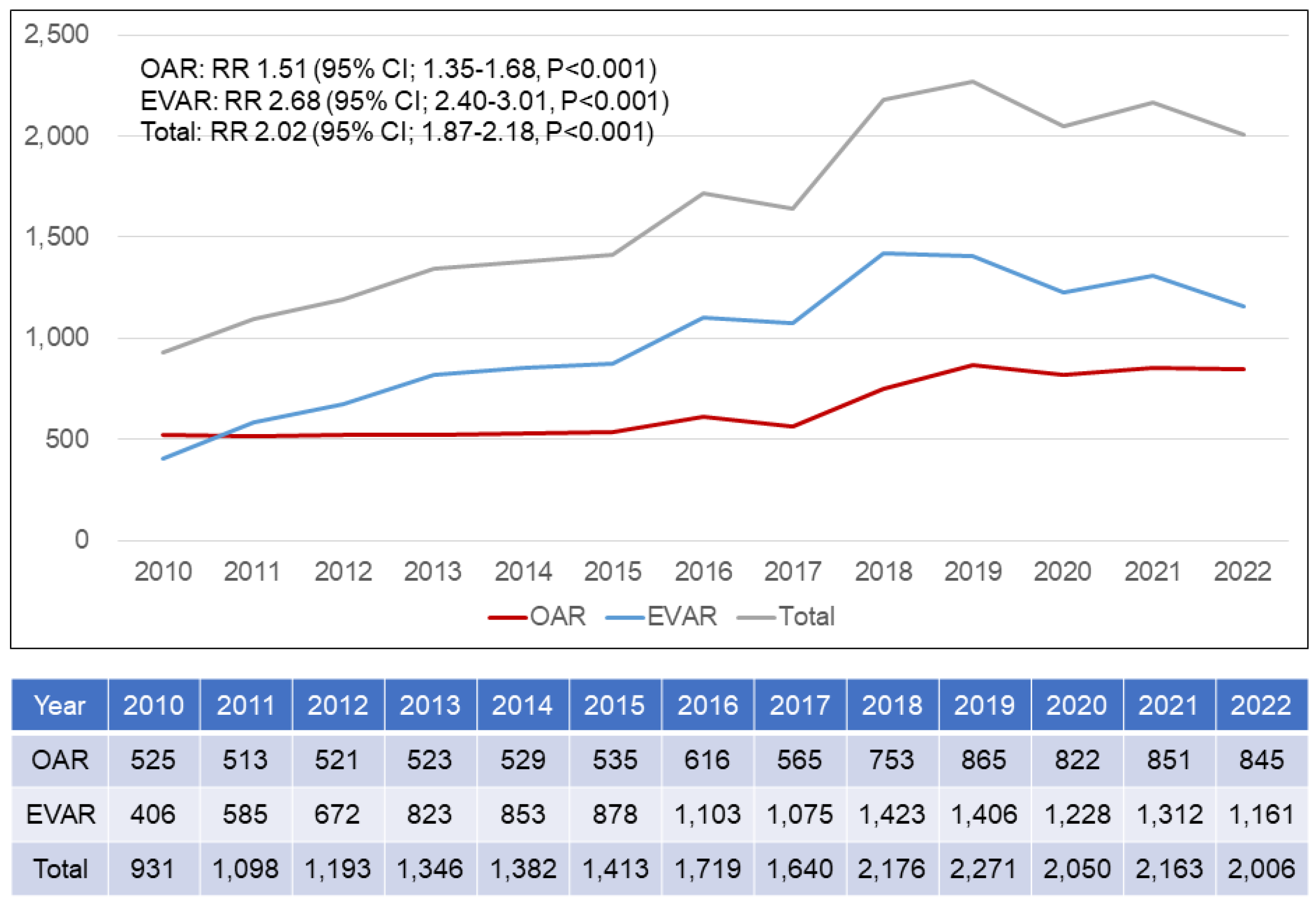

Figure 4 shows the annual number of patients who underwent aneurysm repair by open repair or endovascular repair. The total number of aneurysm repairs increased significantly from 931 in 2010 to 2,006 in 2022 (RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.87-2.18, P<0.001). During the 13-year period, the annual number of patients who underwent OAR increased from 525 in 2010 to 845 in 2022 (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.35-1.68, P<0.001), with a gradual upward trend. However, the number of patients who underwent EVAR markedly increased from 406 in 2010 to 1,161 in 2022 (RR 2.68, 95% CI 2.40-3.01, P<0.001). In 2010 and 2011, the number of patients who performed EVAR annually surpassed those who performed OAR. As the years passed, the number of patients who performed EVAR was higher than that of those who performed OAR.

3.5. Mortality Rate

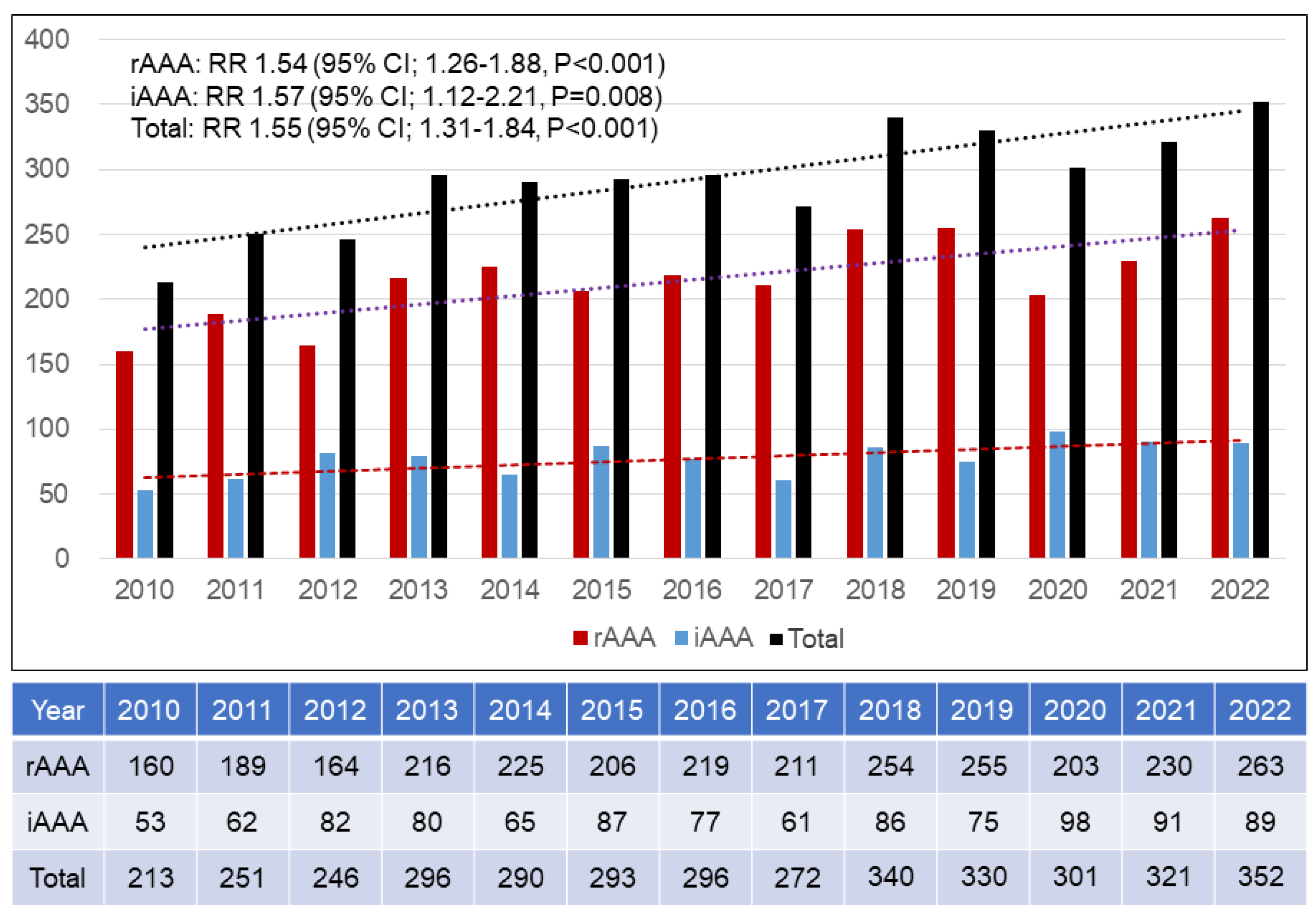

Figure 5 demonstrated the annual numbers of died patients with rAAA and iAAA. Total numbers of patients with rAAA and iAAA increased gradually with 1.54-fold and 1.57-fold, respectively. Therefore, total number of died patients with AAA tardily increased from 213 in 2010 to 352 in 2022 by 1.55-fold (RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.31-1.84, P<0.001).

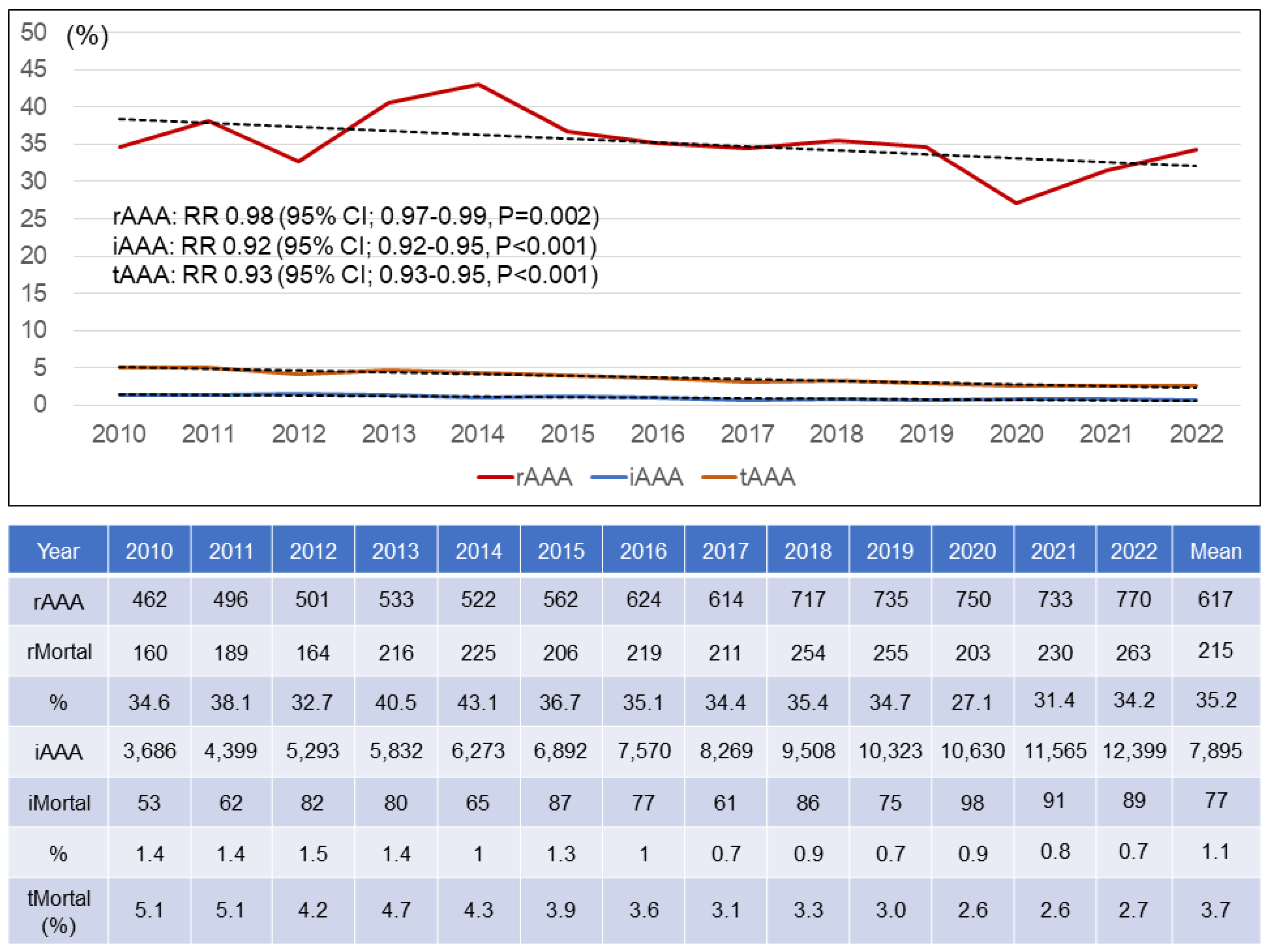

Figure 6 showed the total numbers of patients and died patients with rAAA and iAAA. With those numbers, annual morality rates of AAA were calculated. The morality rate of rAAA was 34.6% in 2010 and 34.2% in 2022 with no changes. Although the total number of patients performed EVAR surpassed that of those performed OAR as 2010 and 2011, the annual mortality rates were similar with the average mortality rate 35.2%. However, the annual mortality rates of iAAA were 1.4% in 2010 and 0.7% in 2022 with the downward trend. The mean mortality rate of iAAA was 1.1 %.

4. Discussion

In this study, AAA nearly tripled over the past 13 years, mainly due to the increase in iAAA. In the annual distribution by gender, iAAA increased in both men and women, but rAAA increased in men, while there was no statistically significant increase in women. Looking at the distribution by age, both rAAA and iAAA were the most prevalent in their 70s. With the increase of AAA, OAR and EVAR showed an increasing trend, and EVAR surpassed OAR in 2011. Over the past 13 years, the mortality rate of iAAA has decreased, while the rate of rAAA has not changed significantly.

It is presumed that the increase in AAA, including rAAA and iAAA, was largely due to health service examination. The diagnosis rate of AAA increased due to abdominal ultrasound, which was included in the health service examination and was widely performed. The introduction of screening program for AAA has being contemplated by health services in several countries [

8]. Many studies demonstrated that AAA screening lowered the mortality rate from AAA and benefits in terms of cost-effectiveness. The UK Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) randomized trial showed that screening resulted in a reduction in all-cause mortality, and the benefit in AAA-related mortality continued to accumulate throughout follow-up [

9]. In addition, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reported that one-time invitation for AAA screening in men aged 65 years or older was associated with decreased AAA rupture and AAA-related mortality rates [

10]. A systematic review on the long-term benefits of one-time AAA screening revealed that population-based one-time screening for AAA with ultrasound in asymptomatic men aged 65 years and older remains beneficial during the longer term after screening has ceased, with significant reductions in AAA mortality and AAA rupture rate, and hence avoids unnecessary AAA-related deaths [

11]. Another reason was assumed that the departments treating AAA have diversified. Previously, OAR and EVAR were performed in vascular surgery and interventional radiology, respectively. But now, AAA has been being treated in general surgery and cardiothoracic surgery as well as interventional cardiology, including two departments [

12]. Another important reason for the increase in AAA might be the increase in public awareness. Tilson MD insisted that AAA was a silent killer and we needed to raise public awareness of this deadly disease [

13].

Interesting results could be found by looking at the annual distribution of rAAA and iAAA by sex. In iAAA, it increased in both men and women, whereas in rAAA, it increased 1.74-fold in men, but there was no significant change in women over the past 13 years. This was speculated to be due to the high frequency of rAAA in men overall. Another reason might be the probability for rAAA repair by sex. Malayala SV compared the characteristics of rAAA in females and males [

14]. The probability to undergo surgery for rAAA was significantly lower for females as compared to males (P = 0.03). However, we should consider the important finding that women tended to have a smaller size of the ruptured aneurysm, faster growth, frequency of rupture, and higher mortality rate though the overall incidence of AAA rupture was higher in males [

14,

15].

According to the distribution of AAA by age, AAA increased as age increased until the 70s and then decreased in the 80s. Singh K et al assessed the age- and sex-specific distribution of the abdominal aortic diameter and the prevalence of and risk factors for AAA [

16]. The prevalence of AAA increased with age. The mean aortic diameter increased with age in both men and women (p < 0.001), although the increase was more pronounced in men. From the age of 55 years, there was a pronounced increase in standard deviation and skewness, particularly in men. Howard DPJ et al reported the population-based data on age-specific incidence of acute AAA [

17]. The incidence per 100,000 population per year was 55 in men aged 65-74 years, but increased to 112 at age 75-84 years and to 298 at age 85 years or above.

Figure 3 showed that although AAA was most prevalent in their 70s, iAAA showed a rapid increase in their 40s, whereas rAAA showed a rapid increase in their 50s, 10 years later. Although this study did not show a detailed age-dependent distribution of rAAA and iAAA, it showed that rAAA rapidly increasing age was higher than iAAA rapidly increasing age. Gormley S et al identified that the mean age of iAAA and rAAA was 75.1 years and 77.8 years, respectively [

18].

This nationwide data analysis showed that the number of EVAR procedures increased from 406 in 2010 to 1,161 in 2022 with a 2.68-fold increasing. The EVAR procedure has the advantage of being less invasive than standard OAR, which has been performed with the basic concept of aneurysm exclusion. Since EVAR was a minimally invasive procedure for AAA patients, the increase in the number of procedures was expected to result in improvements in procedural outcomes, such as aneurysm-related death. However, there were studies showing contradictory results in the long-term results. Yei K et al reported the long-term outcomes associated with EVAR compared with OAR using the Medicare-matched database [

19]. Overall mortality after elective AAA repair was higher with EVAR than OAR despite reduced 30-day mortality and perioperative morbidity after EVAR. Endovascular repair additionally was associated with significantly higher rates of long-term rupture and reintervention. Also, the UK EndoVascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR) randomised controlled trial showed that EVAR had an early survival benefit but an inferior late survival benefit compared with OAR [

20]. However, Lederle FA demonstrated that long-term overall survival was similar among patients who underwent EVAR and those who underwent OAR. A difference between groups was noted in the number of patients who underwent secondary therapeutic procedures [

21].

With the rapid increase in EVAR over the past 13 years, the iAAA mortality rate decreased from 1.4% in 2010 to 0.7% in 2022, while the rAAA mortality rate did not change. In this study, we could not investigate the detail post- EVAR and post-OAR mortality for rAAA due to the use of public data. A systematic review and meta-analysis addressed the mortality after repair of rAAA [

22]. In-hospital and/or 30-day mortality ranged between 0% and 54% in different series, whereas the pooled mortality after EVAR was 24.5%. In addition, mortality after both endovascular and concurrent open repair from the same unit, the pooled mortality after OAR was 44.4%. The pooled overall mortality for aAAA undergoing endovascular or open repair was 35% showing a similar result of our study. Hoornweg LL et al reported changes in mortality after rAAA repair over time [

23]. Mortality after rAAA repair has not changed over the past 15 years. They assumed that this could be explained by increased age of patients undergoing rAAA repair.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study based on an administrative database. Therefore, there was an intrinsic limit to the number of variables that could be measured. Second, the source of database to collect the patients’ and procedures’ numbers only. Third, follow-up data and long-term outcomes were unavailable. Finally, there was no detail post- EVAR and post-OAR mortality for rAAA and iAAA due to the use of public data. Further evaluation is needed after more detailed data are collected, including those specifying the center volume, the application of standard or non-standard EVAR, and use of iliac branch device.

5. Conclusions

The number of patients with AAA has increased during the last 13 years. With the increasing trend in the number of EVAR procedures, the mortality rate associated with iAAA decreased by 50%, while the mortality rate associated with rAAA showed no significant change, averaging 35.2%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J. and S.C.; methodology, J.J.; software, J.J. and S.C.; validation, J.J. and S.C. and J.J. and S.C.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, J.J.; resources, J.J. and S.C.; data curation, J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J. and S.C.; visualization, J.J. and S.C.; supervision, J.J.; project administration, J.J. and S.C.; funding acquisition, NA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong (protocol code; KHNMC 2015-01-027and January 28th, 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to lack of information on the participant’s identity.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Parodi, J.C.; Palmaz, J.C.; Barone, H.D. Transfemoral intraluminal graft implantation for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1991,5,491-499. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, R.M.; Brown, L.C.; Kwong, G.P.; Powell, J.T.; Thompson, S.G.; EVAR trial participants. Comparison of endovascular aneurysm repair with open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1), 30-day operative mortality results: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004,364,843-848.

- Prinssen, M.; Verhoeven, E.L.; Buth, J.; Cuypers, P.W.; van Sambeek, M.R.; Balm, R.; Buskens, E.; Grobbee, D.E.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; Dutch Randomized Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM)Trial Group. A randomized trial comparing conventional and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004,351,1607-1618. [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Freischlag, J.A.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Padberg, F.T. Jr.; Matsumura, J.S.; Kohler, T.R.; Lin, P.H.; Jean-Claude, J.M.; Cikrit, D.F.; Swanson, K.M.; et al. Outcomes following endovascular vs open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomized trial. J.A.M.A. 2009,302,1535-1542.

- Chaikof, E.L.; Dalman, R.L.; Eskandari, M.K.; Jackson, B.M.; Lee, W.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Mastracci, T.M.; Mell, M.; Murad, M.H.; Nguyen, L.L.; et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018,67,2-77. [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D'Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karko,s C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc Surg. 2024,67,192-331. [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Kim, J.A.; Kim, S. A guide for the utilization of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service National Patient Samples. Epidemiol. Health. 2014;36:e2014008. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, G.A.; Giannoukas, A.D.; Georgiadis, G.S.; Antoniou, S.A.; Simopoulos, C.; Prassopoulos, P.; Lazarides, M.K. Increased prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair compared with patients without hernia receiving aneurysm screening. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;53:1184-1188. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.G.; Ashton, H.A.; Gao, L.; Buxton, M.J.; Scott, R.A.; Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) Group. Final follow-up of the Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) randomized trial of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening. Br. J. Surg. 2012;99:1649-1656. [CrossRef]

- Guirguis-Blake, J.M.; Beil, T.L.; Senger ,C.A.; Whitloc,k E.P. Ultrasonography screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160:321-329. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.U.; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; Kenny, M.; Miller, J.; Raina, P.; Sherifali, D. A systematic review of short-term vs long-term effectiveness of one-time abdominal aortic aneurysm screening in men with ultrasound. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018;68:612-623. [CrossRef]

- Hurks, R.; Ultee, K.H.J.; Buck, D.B.; DaSilva, G.S.; Soden, P.A.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; Verhagen, H.J.M.; Schermerhorn, M.L. The impact of endovascular repair on specialties performing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;62:562-568.

- Tilson MD. Public awareness of aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001;9:311-312.

- Malayala SV, Raza A, Vanaparthy R. Gender-Based Differences in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Rupture: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020;12:794-802. [CrossRef]

- Stuntz, M.; Audibert, C.; Su, Z. Persisting disparities between sexes in outcomes of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm hospitalizations. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:17994. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Bønaa, K.H.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Bjørk, L.; Solberg, S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study : The Tromsø Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001;154:236-244.

- Howard, D.P.; Banerjee, A.; Fairhead, J.F.; Handa, A.; Silver, L.E.; Rothwell, P.M.; Oxford Vascular Study. Age-specific incidence, risk factors and outcome of acute abdominal aortic aneurysms in a defined population. Br. J. Surg. 2015;102:907-915. [CrossRef]

- Gormley, S.; Bernau, O.; Xu, W.; Sandiford, P.; Khashram, M. Incidence and Outcomes of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair in New Zealand from 2001 to 2021. J. Clin .Med. 2023;12;2331. [CrossRef]

- Yei, K.; Mathlouthi, A.; Naazie, I.; Elsayed, N.; Clary, B.; Malas, M. Long-term Outcomes Associated With Open vs Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair in a Medicare-Matched Database. J.A.M.A. Netw. Open. 2022;5:e2212081. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Powell, J.T.; Sweeting, M.J.; Epstein, D.M.; Barrett, J.K.; Greenhalgh, R.M. The UK EndoVascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR) randomised controlled trials: long-term follow-up and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health. Technol. Assess. 2018;22:1-132. [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Stroupe, K.T.; Freischlag, J.A.; Padberg, F.T. Jr.; Matsumura, J.S,; Huo, Z.; Johnson, G.R.; OVER Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group.. Open versus Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:2126-2135.

- Karkos, C.D.; Harkin, D.W.; Giannakou, A.; Gerassimidis, T.S. Mortality after endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Surg. 2009;144:770-778.

- Hoornweg, L.L.; Storm-Versloot, M.N.; Ubbink, D.T.; Koelemay, M.J.; Legemate, D.A.; Balm, R. Meta analysis on mortality of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2008;35:558-570. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.11.019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).