Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The Immense Value of Coral Reefs and Their Ongoing Loss

Buying Time for Coral Reefs

The Need for National Coral-Focused Adaptation Plans

Promoting Coral-Focused Adaptation

Mainstreaming ROH Strategies into Existing Programs and Policies

Background Important to Developing an Adaptation Plan for Fiji’s Coral Reefs

Fiji’s Resilient Reefs in Peril

An Ideal Crucible for the Evolution of Thermal Tolerance in Corals

Breakthroughs in Facilitating Natural Processes of Adaptation and Recovery

Materials and Methods

Reefs Hope Operational Strategy

- Remote sensing and field searches to locate potential shallow water heat-adapted coral populations as well as to locate ideal cooler-water nursery sites as nearby as possible.

-

A national coral-focused strategy must first seek out and collect heat-adapted corals of declining species on which to build a programme.

- -

- Collect heat-adapted coral stock of all declining species; 10 genotypes can retain approximately 50% of the original genetic diversity, while 35 genotypes can retain roughly 90% of coral genetic diversity within the species [92].

- -

- Two strategies are employed towards this aim, the first uses mass coral bleaching events as an opportunity to collect unbleached and thus heat-resistant corals, collected as the temperature begins to drop but before partially bleached corals regain their color.

- -

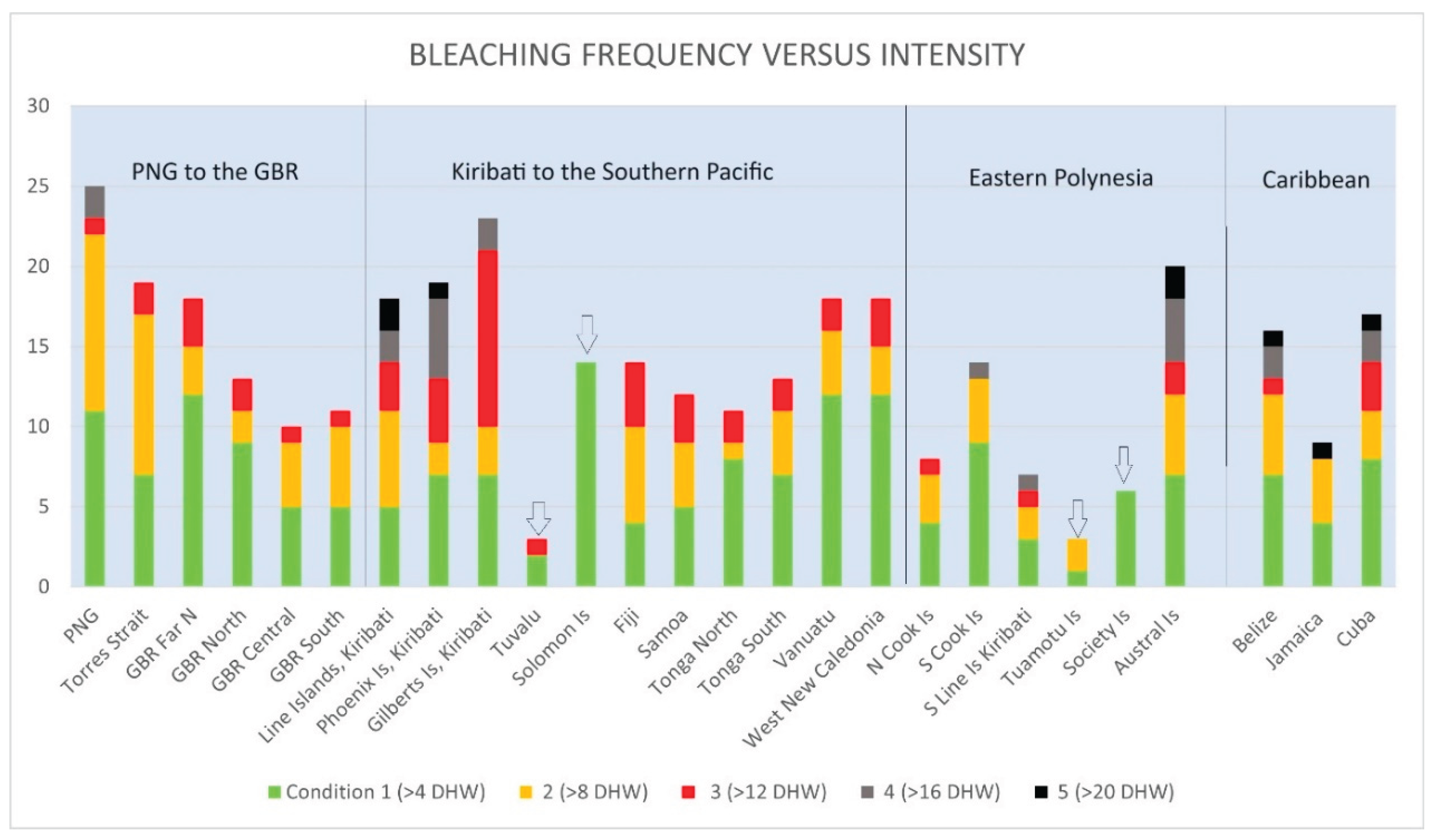

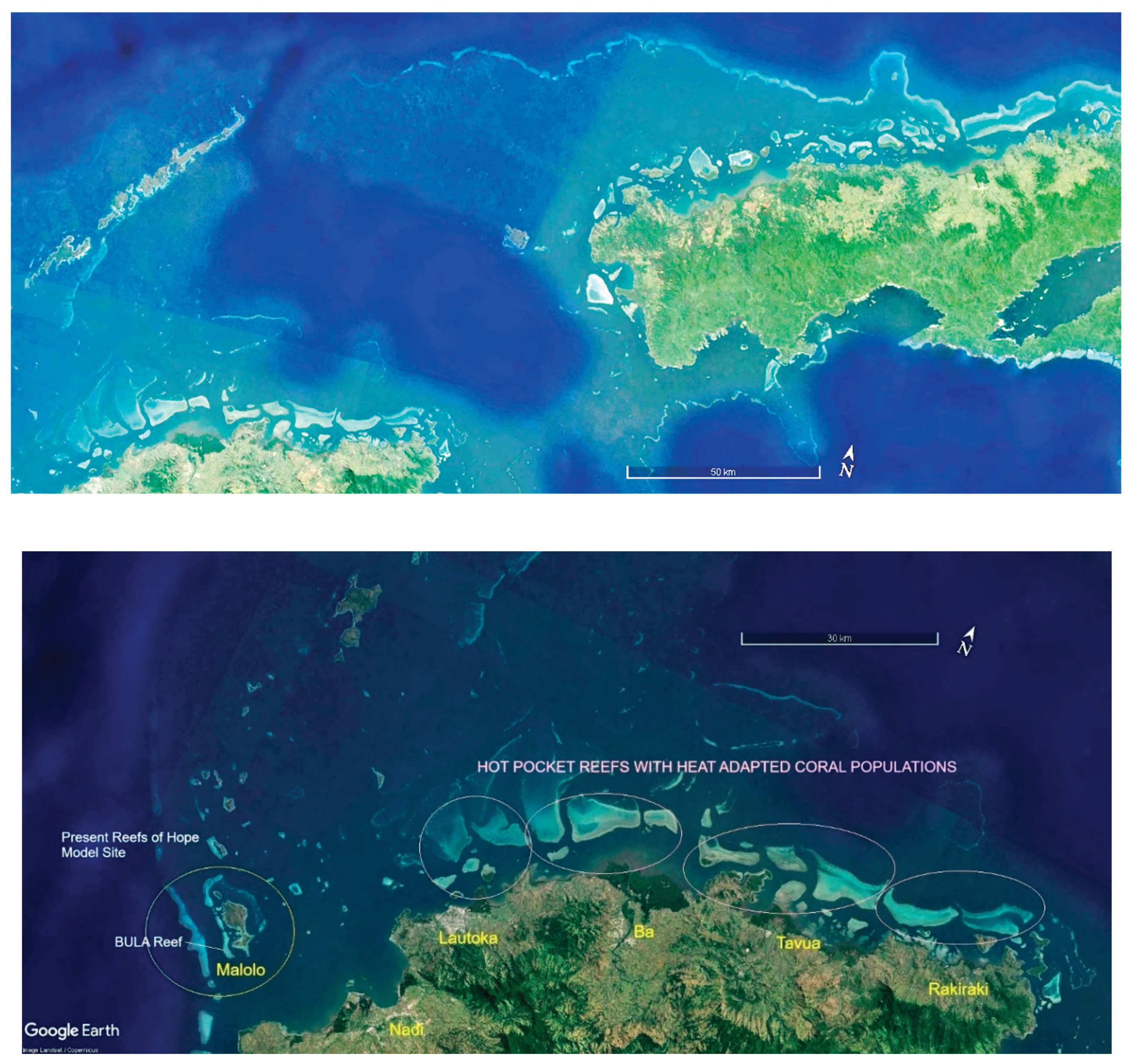

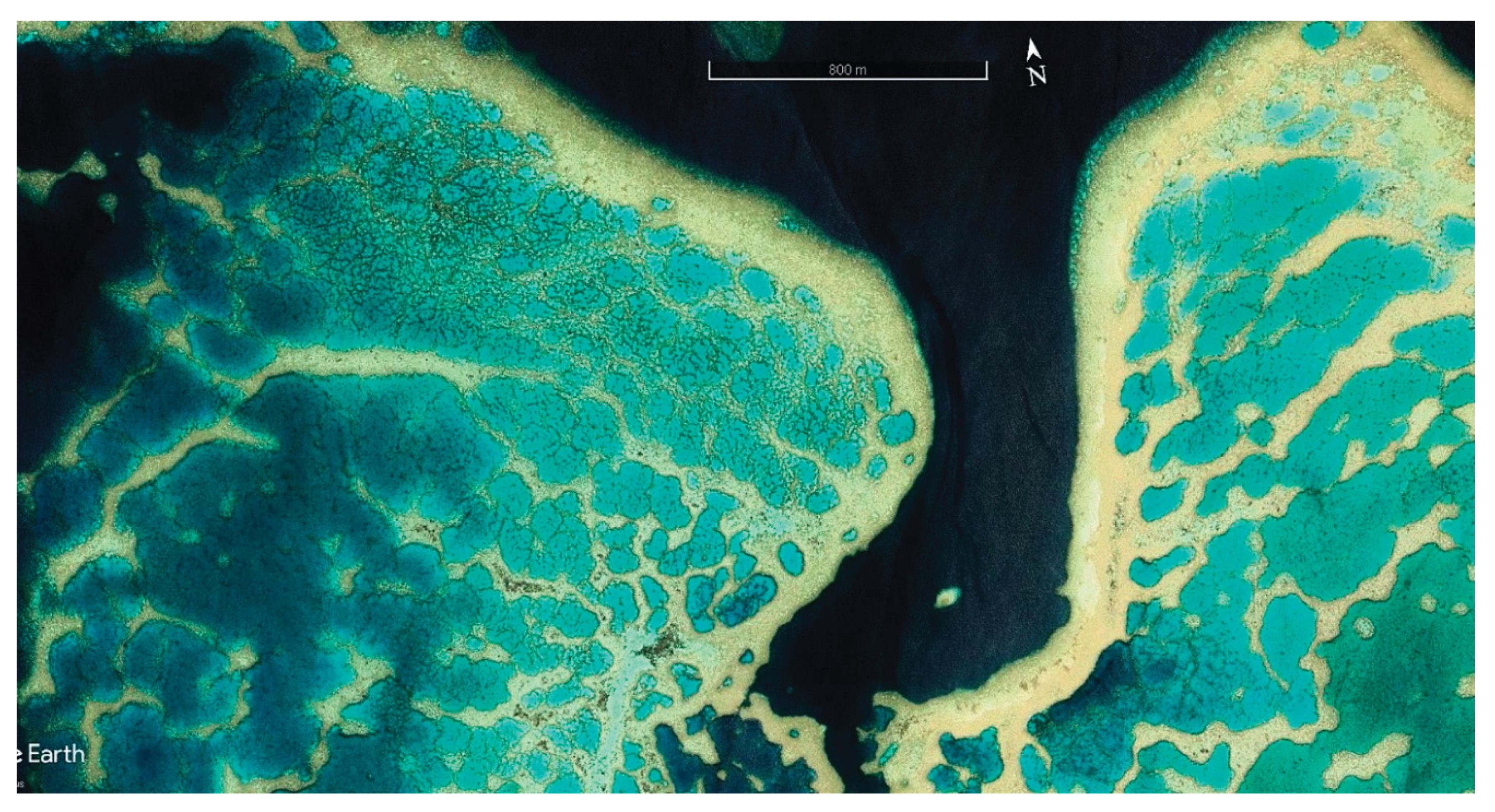

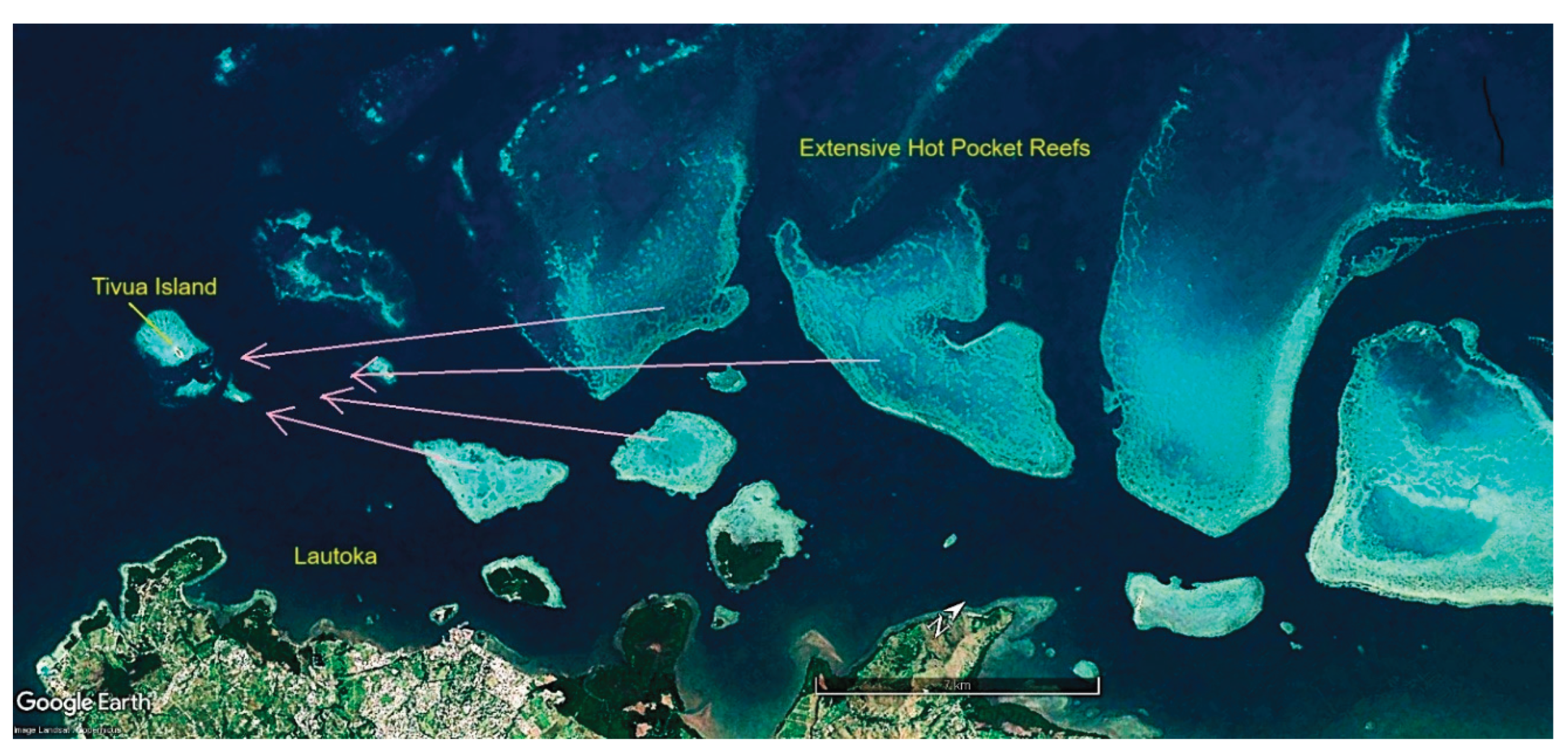

- A second strategy involves identifying heat adapted coral populations of the extreme shallows where corals are chronically exposed to high levels of thermal stress. Corals located in these “hot pocket” areas at the upper threshold of coral survival continually risk death from exposure during extreme low tides and during hot summer temperatures and high UV levels, especially during midday low tides on windless and cloudless days, worsening now due to ocean warming. Once these hot pocket reefs are identified, coral colonies of selected for relocating to cooler-water nurseries nearby, 1-2 meters deeper, to prevent lethal levels of heat stress as the oceans warm, as well as to protect the corals from COTS and other predators.

- -

- The goal is to keep the corals in the gene bank within a thermal stress regime similar to that which they have adapted to before the present climate crisis, to prevent the possibility of symbionts losing their heat resilience over time via local-scale adaptation, which could potentially happen over the decades if a nursery were in much cooler conditions.

- Carry out long-term monitoring by installing temperature loggers in collecting sites and nursery sites, as well as coral monitoring plots in the collecting sites and areas adjacent to nurseries to assess changes to the coral populations over time as the ocean warms, or conversely as hot nearshore waters potentially cool, should rapid sea-level rise commence. Bleaching is also monitored within the gene bank nurseries as well as in the collecting sites during marine heat wave events as climate change and ocean warming develops. Corals within the nurseries that exceed their bleaching thresholds are tagged and translocated to sites where temperatures have remained 1-2C cooler, as indicated by logger data. Corals proven bleaching resistant to extreme temperatures on the reefs can be added to the nurseries as space opens, focusing on collecting species of exceptional resilience represented by fewer genotypes, or representing unusual coloration or other characteristics.

-

Regeneration patches are created in subsequent years using fragments trimmed from colonies within the nurseries as the corals grow larger. These patches start with a single or a few rapidly growing open-branched coral species and are intended to jump-start natural recovery processes which in turn facilitate the transition of the patch into a highly diverse patch representing a balanced natural ecosystem. Corals of rapidly growing branching Acropora species within the nurseries are trimmed annually to prevent their overgrowth, and fragments are used to create regeneration patches for the accelerated regeneration of degraded reef areas (synonymous with nucleation patches of Bowden-Kerby 2023). Planted to various structures designed to enhance survival and ecological impact, the focus is on creating strong settlement signals, enhancing fish habitat, and restoring sexual reproduction to corals.

- -

- As best practices for the creation of regeneration patches are not yet known, there is an important need for experimental comparisons between methods and between coral species used. Optimal patch size and comparisons among the various planting structures designed to receive coral fragments and to enhance fish habitat are needed. Single-species patches of various species, growth forms, and genera as well as mixed-species patches must be set out as experimental comparisons of relative impacts on larval-based coral recovery as well as their ability to provide habitat for various fish species. In this way great strides can be made in better understanding natural larval-based recovery processes and interactions between corals and fish, with best practices for enhancing or accelerating the recovery process established.

Nursery Design and Construction

Planting Corals to Table Nurseries

Regeneration Patch Design and Construction

Results

Proof of Concept for Proactive Coral Rescue in the Face of a Marine Heat Wave

Challenges of Establishing Gene Bank Nurseries

Mass Coral Bleaching as a Major Selection Event for Bleaching Resistant Corals

Developing a Fiji National Coral Reef Adaptation Plan

Phases of a Fiji-Wide National Coral Reef Adaptation Plan

Phase One: Coral Species Rescue and Stabilization

Phase Two: Restoring Sexual Reproduction

Phase Three: Facilitating Natural Recovery Processes

Phase Four: Additional Measures to Support Coral Reef Health

Captive Breeding of Corals

Including Tridacnid Clams in the Coral Reef Adaptation Work

Measures to Combat Ocean Acidification

Detailed Components of the Proposed Coral Reef Adaptation Strategy for Fiji

- Build vision and support for the national coral reef adaptation plan as a collaborative partnership between government ministries, NGOs, academic institutions, and scientists. Create a multi-stakeholder management structure and mechanisms for moving forward, including obtaining financial support for a ten-year program.

- Conduct training of managers and field staff in the strategies and methods to build unified vision and upskill local capacity.

- Work within existing NGO implementation sites using existing data, remote sensing, aerial photos, and local expertise to create coral reef adaptation site plans.

- Identify jeopardized heat-adapted coral populations located within shallow reef areas.

- Identify ideal coral refuge sites where waters are expected to remain 2-4°C cooler and make plans for relocation and securing heat adapted coral colonies.

- Focus on rare and less common coral species within shallow heat stressed reefs, collect and translocate at least 5-10 genetically distinct colonies of each coral species per site to reefs where heat stress is less intense, rescuing them from near certain demise in the short term as the ocean warms, and securing them within gene bank nurseries.

- Use mass bleaching events as selection events for collecting bleaching resistant corals from the wider reef area, incorporating them into the gene bank nurseries to secure them from COTS and to ensure that they are cloned and used to reboot reproduction and natural recovery within regeneration patches.

- As the corals in the nurseries grow, branching species are trimmed and fragments used for rapid growth within suspended rope nurseries located in shallow, moderately stressed waters, where they are cultivated for out-planting work. Slow-growing massive coral species can also be propagated via micro-fragmentation techniques and planted onto concrete domes to create adult-sized colonies within 2-3 years.

- The corals in the rope nurseries grow rapidly and are harvested annually during low heat and low UV stress, with the ropes replanted. These second-generation corals are used for out-planting to create multi-genetic and reproductive recovery patches of each coral species on the reef. Either whole colonies are planted directly to degraded reefs, or branches can be planted onto A-frame or reef star structures, segregated by genotype into quadrants on the frame, so that the branches merge into larger reproductive colonies as they grow.

- Duplicate gene bank nurseries by sending samples to secondary nurseries on each atoll as insurance against loss due to unforeseen conditions.

- Establish temperature loggers in donor and recipient sites to monitor marine heat waves over time, monitoring both the corals left behind and those translocated.

- Encourage community and resort COTS removal activities on high-value reefs and within LMMAs, especially around regeneration patches to help ensure their success.

- Include the translocation of giant clams and rare or uncommon species of sea cucumbers and sea urchins in the work and within no-take MPAs, as these important coral reef species also face demise in extreme temperatures. Monitor these species closely to prevent predators from killing them in the new sites and as needed, locate clams within structures designed to shelter them from octopus, eagle rays and triggerfish.

- Continue to assess which coral species remain in each area of the country to determine which species are common, which are uncommon, which have become rare, and which are now locally extinct, with plans for species recovery via restoration of sexual reproduction. Missing or rare species may require cross-site exchange of samples.

- Implement a formal professional-level credentials training programme, adapted from the Reefs of Hope curriculum approved by the South Pacific Community.

- Through trained and experienced facilitators, involve the community and youth in the coral work, building capacity and hope for the future.

- Include the tourism industry in the work, while maintaining high standards by requiring the oversight and employment of professionally certified coral reef regeneration technicians.

- NGO-supported gene bank nurseries will provide community-based efforts with multiple genotypes of heat adapted corals for the work within LMMAs.

- Monitor the work and continue with the steps above until most of the coral reef LMMAs of the nation have a coral reef regeneration and recovery programme, focused on active support for the adaptation and recovery of coral reefs.

Recommendations Based on Decades of Lessons Learned

Strategies for Collecting and Moving Corals

- For coral recovery programmes, whole coral colonies should be targeted for inclusion within gene bank nurseries, so that the programme will not have delays waiting for corals to grow to the appropriate reprodctive adult size. We must remember that this is a coral rescue, and what is left behind will be monitored until it likely dies in a severe marine heat wave at some point in the future.

- To move as quickly as possible to save more coral biomass, where patches of branching corals are extensive, duplicate fragments of each coral can be collected at the same time as the gene bank nursery is created, with the intention of creating recovery patches simultaneously. This strategy would therefore also collect 15-20cm fragments for planting to frames and stars.

- A systematic approach to collections on the various hot pocket reefs is important to avoid re-collecting the same genotypes.

- Collecting the few unbleached corals at the end of a mass bleaching event as the waters begin to cool is an effective way to ensure that the corals are truly bleaching resistant. However, if this is done, whole colonies do better than fragments, as fragments often bleach severely in the high UV due to increased exposure, unless the fragments are planted under shade.

- When transporting corals, care must be taken to avoid oxidative stress, which can result when using non-aerated containers, or when fragments bunch up together in a container. In Fiji we get 100% survival from transporting coral colonies for hours on deck out of water, if the corals are shaded and constantly sprayed with cool seawater.

Guidance for Selecting Cooler Water Gene Bank Nursery Sites

- Desktop scoping for hot-pocket coral populations and genebank nursery sites should be conducted using Google Earth satellite photos. Coral populations can be identified among the extensive shallow waters and reef flats as potential hot water collection sites. Prospective cooler water nursery sites can also be located. Ground-truthing visits to the promising sites is the second step, to see what corals remain and to verify assumptions. This desktop and field scoping process is required before any plan of action to rescue heat adapted corals can be devised and carried out. The use of drones might be important to fine-tune strategies and save time, once collection areas are identified.

- Follow the principle that outer reefs are generally cooler than inner reefs and smaller reefs with less shallow water area will be cooler than larger reefs with extensive shallow areas. If shallow water temperature data exists, that would also be useful.

- With Reefs of Hope strategies, ideally corals are not translocated into highly different thermal or light regimes, to prevent acclimation pressures away from their original highly resistant state. The goal is to keep heat-adapted corals within the natural stress regimes where they evolved, which now requires local scale translocation, as thermal conditions are shifting due to warming oceans. As global warming progresses, the location of the gene bank nurseries may thus need to shift into cooler waters in the years to come.

- Even short distance translocation a few hundred meters, if taken from <1m deep and moved to ~2m deep, can make a huge difference in reducing temperatures, as it moves corals from the hot thermal layer that forms at the surface and into the cooler layer below.

- Gene bank nurseries ideally should be secure from wave damage, being located behind a shallow reef facing the incoming wave direction.

- As winds and wave directions can be expected to change during shifting monsoons and storms, the nursery should be located where reefs protect it on all sides, not just the prevailing seasonal or fair-weather wave direction.

- Nurseries are situated in waters 2-3 meters deep, to optimize growth and to allow for more community involvement. Situated at least 1-2 meters deeper than the nearby reef flats or coral heads and situated close-up against the reef, so that breaking waves will roll right over and above the nursery during storms. In this way the nursery will have both good flow and excellent protection, and reef fish will visit the nursery to clean the structures.

- Nurseries located near populations of surgeonfish and juvenile parrotfish are cleaned naturally by the fish. However, if the fish are too afraid to cross barren sand or rubble to the nursery, habitat bridges can be created. Tree nurseries are not recommended due to the high cost of hand cleaning, as well as vulnerability during big wave events.

- Elevated table and rope nurseries help prevent coral predation and are less impacted by resuspended silt and associated disease.

- A-frames and reef stars can be used as easily deployed mini gene bank nurseries in shallow water and hardground sites, with up to six genotypes of a single species per frame and one per star, in close proximity so that effective sexual reproduction is restored.

- If a primary goal is to produce fragments for out-planting, rope nurseries can be established on 3m x 3m iron frame tables linked together over sand or rubble substrates, with each rope representing a single genotype of a particular coral species. The corals are trimmed annually, or one colony is fragmented to replant a replacement rope, and the other colonies are used for out-planting.

- 12. Out-planting for restoration is best focused on cooler water reef areas, and is done as mixed genetic patches, to restore reproductive potential to declining species. If reef stars or A-frames are used, 2-3 distinct genotypes should be planted to each star, with each genotype planted to a specific section, to encourage fusion of branches, resulting in merging into adult colonies over a shorter time frame.

Discussion

Government Incentives and Policies Are Needed to Support Coral Reef Adaptation

Representative Estimated Budget

| ITEM | Per year site cost | 20 Sites/ year | Ten years |

| Personnel | €100,000. | € 2,000,000. | €20,000,000. |

| Boats, Fuel, Travel | 50,000. | 1,000,000. | 10,000,000. |

| Nursery Materials | 10,000. | 200,000. | 2,000,000. |

| Out-planting Materials | 10,000. | 200,000. | 2,000,000. |

| Community Workshops | 10,000. | 200,000. | 2,000,000. |

| SUBTOTALS | € 180,000. | € 3,600,000. | € 36,000,000. |

| Additional support for coral spawning systems to double as giant clam hatcheries |

100,000. |

Five sites/ yr 500,000. |

Ten Years € 5,000,000. |

| TOTALS | € 275,000. | € 4,100,000. | € 41,000,000. |

Reinterpreting of the Precautionary Principle of Science

Conclusion

References

- Drake JL, Mass T, Stolarski J, Von Euw S, van de Schootbrugge B, Falkowski PG. How corals made rocks through the ages. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett J, Jarillo S, Swearer SE, et al. Nature-based solutions for atoll habitability. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377.

- Ferrario F, Beck MW, Storlazzi CD, Micheli F, Shepard CC, Airoldi L. The effectiveness of coral reefs for coastal hazard risk reduction and adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan MM, Kabir MB, Prodhan MSR, et al. The Physical and Mechanical Properties of Coral Sand. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2024, 2, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O, Poloczanska ES, Skirving W, Dove S. Coral reef ecosystems under climate change and ocean acidification. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 252954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M, Burke L, Wood SA, Ashpole J, Hutchison J, zu Ermgassen P. Mapping the global value and distribution of coral reef tourism. Mar. Policy 2017, 82, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1999, 50, 839–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voolstra CR, Peixoto RS, Ferrier-Pagès C. Mitigating the ecological collapse of coral reef ecosystems. EMBO Rep. 2023, 2023, 24. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Program. (2021). Why are coral reefs dying? 2021, November 12. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/why-are-coral-reefs-dying.

- Najeeb S, Khan RAA, Deng X, Wu C. Drivers and consequences of degradation in tropical reef island ecosystems: strategies for restoration and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1518701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulà C, Bradshaw CJA, Cabeza M, Manca F, Montano S, Strona G. Restoration cannot be scaled up globally to save reefs from loss and degradation. Nat Ecol Evol. 2025, 9, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggat WP, Camp EF, Suggett DJ, et al. Rapid Coral Decay Is Associated with Marine Heatwave Mortality Events on Reefs. Current Biology. 2019, 29, 2723–2730.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden-Kerby, A. Coral-focused climate change adaptation and restoration based on accelerating natural processes: Launching the “Reefs of Hope” paradigm. Oceans 2023, 4, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes TP, Kerry JT, Álvarez-Noriega M, Álvarez-Romero JG, Anderson KD, Baird AH, et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 2017, 543, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. (2019). IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/.

- Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby PJ, Hooten AJ, Steneck RS, Greenfield P, Gomez E, et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 2007, 318, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A Research Review of Interventions to Increase the Persistence and Resilience of Coral Reefs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Bay RA, Palumbi SR, Davies SW, et al. Coral conservation in the age of genome editing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 12134–12141. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbi SR, Barshis DJ, Traylor-Knowles N,; Bay RA. Mechanisms of reef coral resistance to future climate change. Science 2014, 344, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver TA & Palumbi, SR. Do fluctuating temperature environments elevate coral thermal tolerance. Coral Reefs 2011, 30, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaie A, Silbiger NJ, McClanahan TR, et al. High frequency temperature variability reduces the risk of coral bleaching. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas L, Rose NH, Bay RA, Lopez EH, Morikawa MK, Ruiz-Jones L, Palumbi SR. Mechanisms of thermal tolerance in reef-building corals across a fine-grained environmental mosaic: Lessons from Ofu, American Samoa. Frontiers in Marine Science 2018, 5, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa MK,; Palumbi SR. Using naturally occurring climate resilient corals to construct bleaching-resistant nurseries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 10586–10591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oppen MJH, Oliver JK, Putnam HM, Gates RD. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 2307–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood S, Stephen J, Pandolfi JM, Palumbi SR. Potential for conservation via relocation: Spatial genetic structure of thermally tolerant corals and implications for assisted migration. Global Change Biology 2023, 29, 999–1013. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA. (2023). Unprecedented marine heatwave impacts Florida coral reefs. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coral Reef Watch. https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov.

- Lindsey, R. (2023). NOAA and partners race to rescue remaining Florida corals from historic ocean heat wave. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/noaa-and-partners-race-rescue-remainig-florida-corals-historic-ocean.

- Muller EM, Bartels E, Baums IB, et al. Widespread coral bleaching in Florida linked to anomalously high sea temperatures. Frontiers in Marine Science 2023, 10, 1227745. [Google Scholar]

- Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. (2023). 2023 Coral Rescue Operation Summary. NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

- Eakin CM, Heron SF, Liu G, et al. (2023). Global coral bleaching continues into 2023: record heat stress in the Atlantic and Caribbean. NOAA Coral Reef Watch Special Report, September 2023.

- AGRRA (Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment). (2023). Preliminary Report on Coral Mortality in the Caribbean following 2023 Heatwaves. https://www.agrra.

- 32 Alemu J, Laydoo R, et al. (2024). Coral bleaching and mortality in Trinidad and Tobago during the 2023–2024 marine heatwave. Marine Pollution Bulletin (early view).

- Hernández-Delgado EA, Rodríguez-González YM. Runaway Climate Across the Wider Caribbean and Eastern Tropical Pacific in the Anthropocene: Threats to Coral Reef Conservation, Restoration, and Social–Ecological Resilience. Atmosphere. 2025, 16, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden-Kerby A, Romero L, and Kirata T. (2021). Chapter 17: Line Islands Case Study. In: Active Coral Restoration: Techniques for a changing planet, David Vaughn, Editor. 610pp. https://www.jrosspub.com/science/environmental-science/active-coral-restoration.html.

- IPCC. 2023. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change (2023). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. (2024). Global Climate Highlights 2023: Hottest Year on Record. European Union, ECMWF. https://climate.copernicus.

- Wooldridge, S. A. , & Pratchett, M. S. Coral predators exert selection pressure on corals with heat tolerance traits: implications for reef recovery under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 7, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Kayal, M. , Vercelloni, J., Lison de Loma, T., Bosserelle, P., Chancerelle, Y., Geoffroy, S., Stievenart, C., Michonneau, F., Penin, L., Planes, S., & Adjeroud, M. Predator crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) outbreak, mass mortality of corals, and cascading effects on reef fish and benthic communities. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47363. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden-Kerby, A. (2003). Community-based Management of Coral Reefs: An Essential Requisite for Certification of Marine Aquarium Products Harvested from Reefs Under Customary Marine Tenure. Chapter 11: 141-166 In: Marine Ornamental Species: Collection, Culture and Conservation. Cato, J and C. Brown Editors. Iowa State Press/ Blackwell Scientific Publications, NY, 395 pp.

- Govan H, Tawake A,; Tabunakawai K. Community-based marine resource management in the South Pacific. SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin 2009, 25, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jupiter SD, Cohen PJ, Weeks R, Tawake A,; Govan H. Locally-managed marine areas: multiple objectives and diverse strategies. Pacific Conservation Biology 2014, 20, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClanahan TR, Darling ES, Maina J, Muthiga NA, et al. Climate change and coral reef fisheries: shared challenges, converging solutions. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2021, 288, 20210927. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden-Kerby, A. (2020). Coral restoration for climate change adaptation in the South Pacific. Pages 54-57 In: Hein et al. Coral Reef Restoration as a strategy to improve ecosystem services – A guide to coral restoration methods. UNEP Report, 60pp.

- Eastwood EK, López EH, Drew JA. Population Connectivity Measures of Fishery-Targeted Coral Reef Species to Inform Marine Reserve Network Design in Fiji. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 19318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harding SP, Solandt JL, Walker RC, Walker D, Taylor J, Haycock S, Davis MT, and Raines P. Reef Check Data Reveal Rapid Recovery from Coral Bleaching In the Mamanucas, Fiji. Silliman Journal 2022, 44. [Google Scholar]

- WCS (2020). https://fiji.wcs.org/News-Room/ID/15026/ Research Expedition to Assess Coral Reef Health and Recovery from Tropical Cyclone Winston.

- Rowlands G, Comley J, and Raines P, (2005). The Coral Coast, Viti Levu, Fiji, A Marine Resource Assessment. Published: by Coral Cay Foundation and SPREP. 124pp.

- Bruckner, AW. (2014). Global Reef Expedition: Lau Province, Fiji. Field Report. Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Landover MD. 33 pp.

- Lequeux C, Dumas P,; Andréfouët S. Connectivity of coral reefs in the Fiji Islands: insights from oceanographic modeling and implications for conservation. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 135, 684–697. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Mellegers M, & Souter D. (2018). Fiji Marine Environment Monitoring Report 2005–2015. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network.

- Ganachaud A, Sen Gupta A, Brown JN, et al. Projecting changes in the South Pacific Ocean circulation using IPCC models. Climate Dynamics 2011, 36, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Mumby PJ, Sartori G, Buccheri E, Alessi C, Allan H, Doropoulos C, Rengiil G, Ricardo G. Allee effects limit coral fertilization success. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2418314121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mellin C, Brown S, Cantin N, Klein-Salas E, Mouillot D, Heron SF, Fordham DA. Cumulative risk of future bleaching for the world's coral reefs. Sci Adv. 2024, 10, eadn9660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schoepf V, Stat M, Falter JL, McCulloch MT. Thermally tolerant corals have limited capacity to acclimatize to future warming. Global Change Biology 2019, 25, 968–982. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KT, Martynek MP,; Barott KL. Local habitat heterogeneity rivals regional differences in coral thermal tolerance. Coral Reefs 2024, 43, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepac CN, and Barshis DJ. Reduced thermal tolerance of massive coral species in a highly variable environment. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2020, 28720201379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L. et al. The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne DG, Morrow KM,; Webster NS. Insights into the coral microbiome: Underpinning the health and resilience of reef ecosystems. Annual Review of Microbiology 2016, 70, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suggett DJ,; Smith DJ. Coral bleaching patterns are the outcome of complex biological and environmental networking. Global Change Biology 2020, 26, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apprill, A. The role of symbioses in the adaptation and resilience of coral reefs to environmental change. Annual Review of Marine Science 2020, 12, 489–516. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler M, Arif C, Burt JA, Dobretsov S, Roder C, LaJeunesse TC, Voolstra CR. Biogeography and molecular diversity of coral symbionts in the genus Symbiodinium around the Arabian Peninsula. Journal of Biogeography 2017, 44, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, R. Thermal adaptation in reef coral symbionts. Nature 2004, 430, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkelmans R,; van Oppen MJH. The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: A ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2006, 273, 2305–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunning R, Silverstein RN, & Baker, AC. Investigating the causes and consequences of symbiont shuffling in a multi-partner coral symbiosis under environmental stress. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 0141. [CrossRef]

- Barshis DJ, Ladner JT, Oliver TA, Seneca FO, Traylor-Knowles N, Palumbi SR. Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs CA, Fauth JE, Halas JC, Dustan P, Bemiss J, Woodley CM. Oxidative stress and seasonal coral bleaching. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2002, 33, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middlebrook R, Anthony KRN,; Hoegh-Guldberg O. Thermal priming affects symbiont photosynthesis but does not alter bleaching susceptibility in Acropora millepora. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2008, 357, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay RA,; Palumbi SR. Multilocus adaptation associated with heat resistance in reef-building corals. Current Biology 2014, 24, 2952–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oppen MJH, Oliver JK, Putnam HM,; Gates RD. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 2307–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon GB, Davies SW, Aglyamova GA, Meyer E, Bay LK,; Matz MV. Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science 2015, 348, 1460–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth TD, Heron SF, Ortiz JC, Mumby PJ, Grech A, Ogawa D, Eakin CM, Leggat W. Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 2016, 352, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoepf V, Carrion SA, Pfeifer SM, Naugle M, Dugal L, Bruyn J, McCulloch MT. Stress-resistant corals may not acclimatize to ocean warming but maintain heat tolerance under cooler temperatures. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kenkel CD, Meyer E,; Matz MV. Gene expression under chronic heat stress in populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different thermal environments. Molecular Ecology 2013, 22, 4322–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley KM, Bay LK, van Oppen MJH. Selective breeding of corals provides insight into the genetic basis of thermal tolerance. Frontiers in Marine Science 2020, 7, 796. [Google Scholar]

- Bay RA, Palumbi SR. Multilocus adaptation associated with heat resistance in reef-building corals. Current Biology 2014, 24, 2952–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley KM, Warner PA, Bay LK. The genetic architecture of inherited variation in thermal tolerance in the reef-building coral Acropora millepora. Molecular Ecology 2019, 28, 3864–3880. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JA, Brokstein PB, Voolstra C, Coffroth MA. Late larval development and onset of symbiosis in the coral Acropora palmata. Biological Bulletin 1999, 196, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose M, Kinzie RA, Hidaka M. Vertical transmission of symbiotic dinoflagellates in the planulae of the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Zoological Science 2001, 18, 515–518. [Google Scholar]

- Apprill A, Marlow HQ, Martindale MQ, Rappé MS. The onset of microbial associations in the coral Pocillopora meandrina. ISME Journal 2009, 3, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite DCA, Salles JF, Calderon EN, Castro CB, Bianchini A, Marques JA, Parente TE, Tsai SM, Peixoto RS. Broadcast spawning coral species associate with specific bacterial communities during early developmental stages. Ecological Indicators 2017, 81, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam HM, Mayfield AB, Fan TY, Chen CS, Gates RD. The physiological and molecular responses of larvae from the reef-building coral Pocillopora damicornis exposed to near-future increases in temperature and pCO2. Marine Biology 2012, 160, 2157–2173. [Google Scholar]

- Voolstra CR, Buitrago-López C, Perna G, Cárdenas A, Hume BCC, Rädecker N, Barshis DJ. Standardized short-term acute heat stress assays resolve historical differences in coral thermotolerance across microhabitat reef sites. Global Change Biology 2021, 27, 4307–4319. [Google Scholar]

- Stat M,; Gates RD. Clade D Symbiodinium in Scleractinian Corals: A “Nugget” of Hope, a Selfish Opportunist, an Ominous Sign, or All of the Above? Journal of Marine Biology 2011, 2011, 730715. [Google Scholar]

- Barott KL, et al. Coral bleaching response is unaltered by community composition in long-term warmed reefs. PNA 2021, 118, e2025435118. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TP, Kerry JT, Baird AH, Connolly SR, Dietzel A, Eakin CM, Heron SF, Hoey AS, Hoogenboom MO, Liu G, McWilliam MJ, Pears RJ. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 2018, 556, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pears RJ, Devlin M, Hammerman N. et al. (2024). CORDAP R&D Technology Roadmap on Managing the Ecological Risks of Coral Reef Interventions. CORDAP. cordap.org.

- NOAA. (2023). Record-breaking marine heatwave devastates Florida coral reefs. Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Morais RA, Smith TB, Williams DE, & Edmunds PJ. (2024). Caribbean corals under extreme heat stress: insights from the 2023 bleaching event. Coral Reefs.

- Vardi T, Williams DE, Sandin SA,; Zgliczynski BJ. Shifting paradigms in coral restoration: building resilience in the age of climate change. Ecological Applications 2021, 31, e02315. [Google Scholar]

- Bay RA, Rose NH, Logan, CA,; Palumbi, SR. Genomic models predict successful coral adaptation if future ocean warming rates are reduced. Science Advances 2019, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer TL, Porto I, Zubillaga AL. Restoration of coral populations in light of genetic diversity estimates. Coral Reefs. 2009, 28, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McDougall, A. (2020). Territorial Damselfishes as Coral Gardening Partners during a Bloom of the Cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Master’s Thesis, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paerl HW,; Paul VJ. Climate change: Links to global expansion of harmful cyanobacteria. Environmental Microbiology Reports 2012, 4, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeij MJA, Marhaver KL, Huijbers CM, Nagelkerken I,; Simpson SD. Coral larvae move toward reef sounds. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10660. [Google Scholar]

- Lillis A, Eggleston DB,; Bohnenstiehl DR. Soundscape variation from a larval perspective: the role of habitat identity and temporal dynamics in a coral reef. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2013, 472, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mason B, Beard M,; Miller MW. Coral larvae settle at a higher frequency on red surfaces. Coral Reefs 2011, 30, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin PM, Szmant AM. Settlement induction of Acropora palmata planulae by a GLW-amide neuropeptide. Coral Reefs 2010 2010, 29, 929–939. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Hatta M. The Importance of GLWamide Neuropeptides in Cnidarian Development and Physiology. The Importance of GLWamide Neuropeptides in Cnidarian Development and Physiology. J. Amino Acids 2011 2011, 424501. [Google Scholar]

- Morishima SY, Yamashita H, Ohara S, Nakamura Y, Quek VZ, Yamauchi M, et al. Study on expelled but viable zooxanthellae from giant clams, with an emphasis on their potential as subsequent symbiont sources. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleypas JA, Anthony KRN, Castruccio FS, et al. Designing a blueprint for coral reef survival under rapid climate change. Global Change Biology 2021, 27, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O, Poloczanska ES, Skirving W, Dove S. Coral reef ecosystems under climate change and ocean acidification. Frontiers in Marine Science 2018, 4, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Tittensor DP, Novaglio C, Harrison CS, et al. A global agenda for advancing climate resilience of marine ecosystems. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AK, Griffies SM, Winton M, et al. Mechanisms and impacts of a partial AMOC collapse in the GFDL CM4 climate model. Journal of Climate 2020, 33, 8043–8064. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze C, Meyer S, Goris N, et al. The quiet crossing of ocean tipping points. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2008478118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe RJ, Falter JL, Monismith SG, Atkinson MJ. Wave-driven circulation of a coastal reef–lagoon system. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2009, 39, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woesik R, Houk P, Isechal AL, et al. Climate-change refugia in the sheltered bays of Palau: analogs of future reefs. Ecology and Evolution 2012, 2, 2474–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy EV, Perry CT, Halloran PR, Iglesias-Prieto R, Schönberg CHL, Wisshak M, et al. Avoiding coral reef functional collapse requires local and global action. Current Biology 2020, 30, R995–R1000. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).