Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

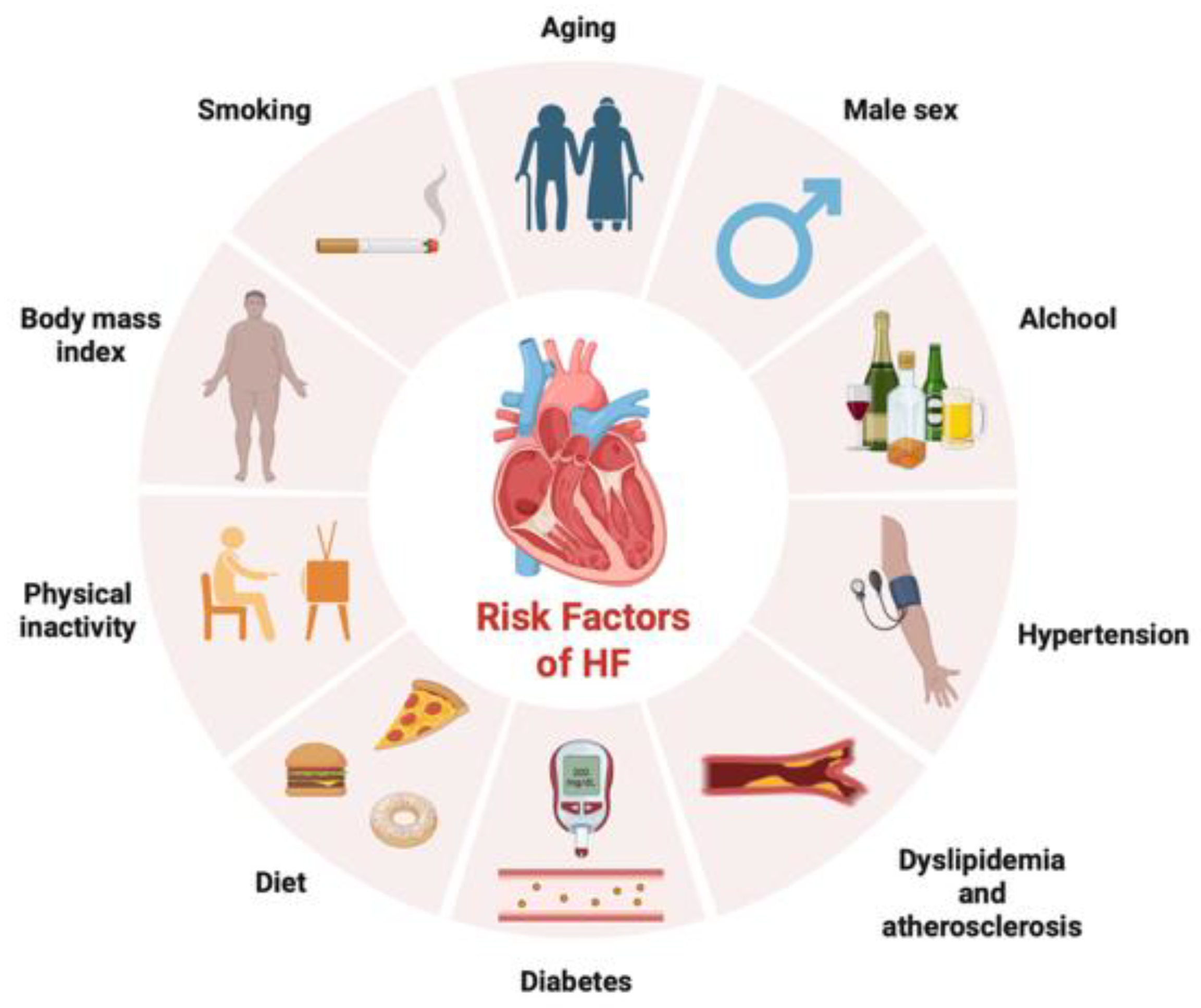

1. Introduction

- Clinical history (e.g. as complication of other diseases)

- By symptoms

- Physical examination

- Heart electrical activity

- Heart ultrasound imaging and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

- Blood biomarkers (e.g. classical biomarkers, i.e. b-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and troponin)

1.1. Enigmatic Definition of HF

2. Biomarkers and HF: the Classical Molecules and Their Advantages and Limitations

2.1. Traditional Biomarkers: BNP and NT-proBNP with Their Advantages and Limitations

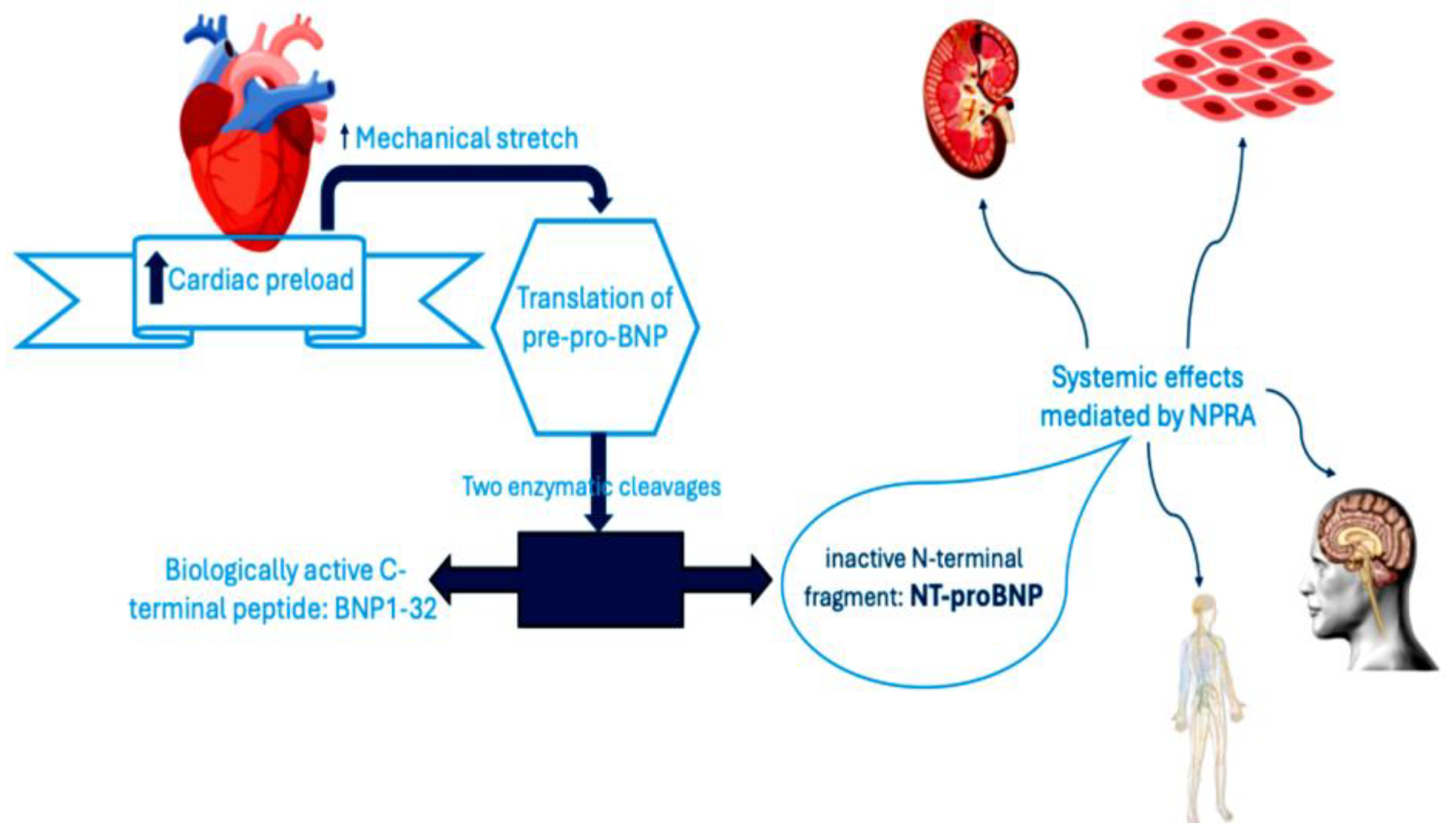

2.1.1. BNP and NT-proBNP

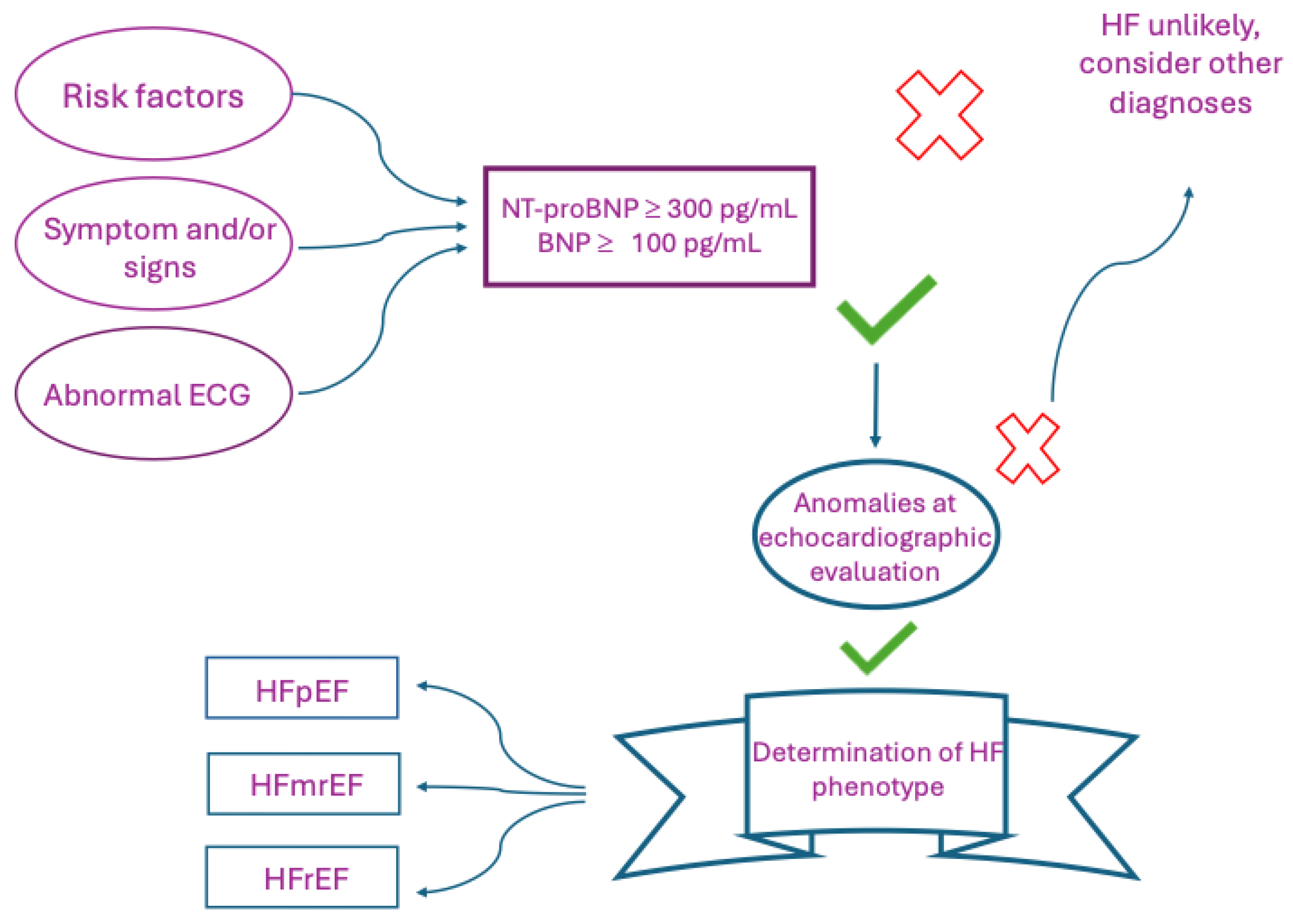

2.1.2. NTproBNP and HF

2.1.3. MR-pro-ANP: Another Biomarker Prevalently Associated with the HF Diagnosis

2.1.4. Troponins as Myocardial Damage Biomarker

3. Emerging Biomarkers: from Diagnostic to Prognostic and Therapeutic Purpose

3.1. Biomarkers of Neuro-Hormonal Activation

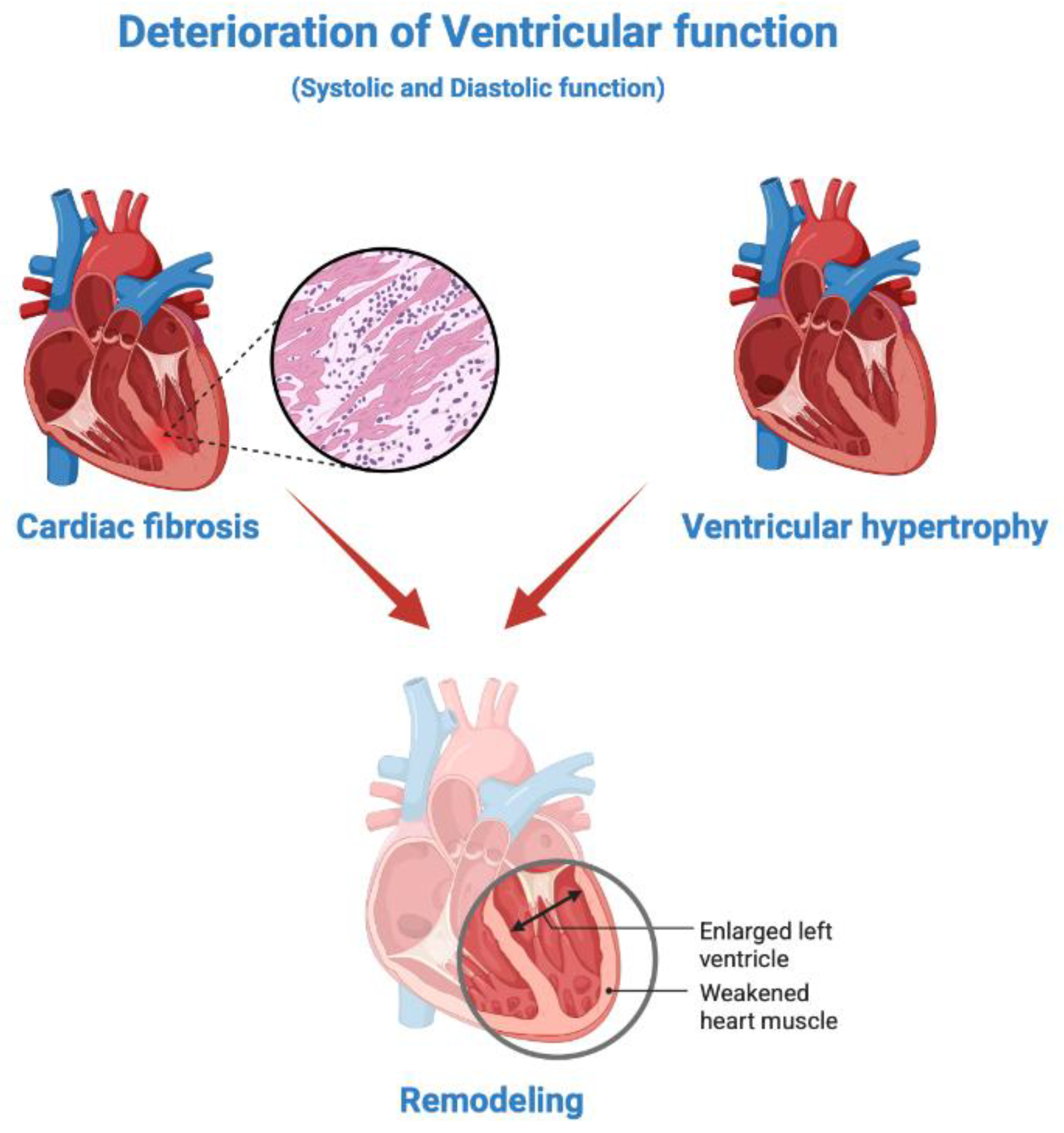

3.2. Biomarkers of Fibrosis and Cardiac Remodeling

3.2. Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

3.4. Clinical Viewpoint: Considerations and Limitations

4. Other Promising Biomarkers: Biomarkers of Negative HF Outcomes

4.1. Iron Deficiency

4.1.1. ID Blood Biomarkers

4.1.2. Clinical Viewpoint: Considerations and Limitations

4.2. Altered Renal Function: Related Biomarkers

4.2.1. Clinical Viewpoint: Considerations and Limitations

4.3. Altered Hepatic Function: Related Biomarkers

4.4. Endocrine-Metabolic Changes

5. Considerations: Towards the Development of Multi-Biomarkers Panels Through Artificial Intelligence and Multi-Omics???

5.1. From the Application of Multi-Omics to the Identification of Further Emerging Biomarkers: Genetic, Genomic and Transcriptome Biomarkers

6. From Identifying New Molecules as Emerging Biomarkers to Applying Them as Targets for Innovative Treatments in HF

6.1. Molecular Targeted Therapies

6.2. Challenges and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Riet EE, Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Limburg A, Landman MA, Rutten FH. , “Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 18(3):242-52. , 2016. [CrossRef]

- Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C, Sanderson JE, Rusconi C, Flachskampf FA, Rademakers FE, Marino P, Smiseth OA, De Keulenaer G, Leite-Moreira AF, Borbély A, Edes I, Handoko ML, Heymans S, Pezzali N, Pieske B, Dickstein K, Fraser AG, Brutsaert DL., “How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology.,” Eur Heart J, Vols. 28(20):2539-50. , 2007. [CrossRef]

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Commodore-Mensah Y, Elkind MSV, Evenson KR, Eze-Nliam C, Fugar S, Generoso G, Heard DG, Hiremath S, Ho JE, Kalani R, Kazi DS, Ko D, Levine DA, “Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association.,” Circulation , Vols. 147(8):e93-e621., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longeneck, “Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association,” Circulation, Vols. 141(9):e139-e596., 2020. [CrossRef]

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Allen NB, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Bansal N, Beaton AZ, Commodore-Mensah Y, Currie ME, Elkind MSV, Fan W, Generoso G, Gibbs BB, Heard DG, Hiremath S, Johansen MC, Kazi DS, Ko D, Leppert MH, Magnani, “2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association.,” Circulation, 2025.

- Siontis GC, Bhatt DL, Patel CJ., “Secular Trends in Prevalence of Heart Failure Diagnosis over 20 Years (from the US NHANES).,” Am J Cardiol., Vols. 172:161-164. , 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ho JE, Enserro D, Brouwers FP, Kizer JR, Shah SJ, Psaty BM, Bartz TM, Santhanakrishnan R, Lee DS, Chan C, Liu K, Blaha MJ, Hillege HL, van der Harst P, van Gilst WH, Kop WJ, Gansevoort RT, Vasan RS, Gardin JM, Levy D, Gottdiener JS, de Boer RA, Larson MG., “Predicting Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction: The International Collaboration on Heart Failure Subtypes.,” Circ Heart Fail., 2016.

- Rasalam R, Sindone A, Deed G, Audehm RG, Atherton JJ. , “State of precision medicine for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a new therapeutic age.,” ESC Heart Fail, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes SL, Carvalho RR, Santos LG, Sá FM, Ruivo C, Mendes SL, Martins H, Morais JA., “Pathophysiology and Treatment of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: State of the Art and Prospects for the Future.,” Arq Bras Cardiol. , Vols. 114(1):120-129. , 2020.

- Achten A, Weerts J, van Koll J, Ghossein M, Mourmans SGJ, Aizpurua AB, van Stipdonk AMW, Vernooy K, Prinzen FW, Rocca HB, Knackstedt C, van Empel VPM, “Prevalence and prognostic value of ventricular conduction delay in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.,” Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc., vol. 57:101622, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dogheim GM, Amralla MT, Werida RH., “Role of neopterin as an inflammatory biomarker in congestive heart failure with insights on effect of drug therapies on its level.,” Inflammopharmacology., Vols. 30(5):1617-1622., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vlachakis PK, Theofilis P, Kachrimanidis I, Giannakopoulos K, Drakopoulou M, Apostolos A, Kordalis A, Leontsinis I, Tsioufis K, Tousoulis D., “The Role of Inflammasomes in Heart Failure.,” Int J Mol Sci. , vol. 25(10):5372., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ,, “2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.,” J Am Coll Cardiol, Vols. 62(16):e147-239., 2013.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Evers LR, Fang JC, Fedson SE, Fonarow GC, Hayek SS, Hernandez AF, Khazanie P, Kittleson MM, Lee CS, Link MS, Milano CA, Nnacheta LC, Sandhu AT, Stevenson , “2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 79(17):1757-1780. , 2022. [CrossRef]

- McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rønnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Ste, “ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart,” Eur J Heart Fail. , Vols. 14(8):803-69., 2012.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P;, “2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 18(8):891-975., 2016.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray , “2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contributio,” Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed)., vol. 75(6):523. , 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui H, Isobe M, Ito H, Ito H, Okumura K, Ono M, Kitakaze M, Kinugawa K, Kihara Y, Goto Y, Komuro I, Saiki Y, Saito Y, Sakata Y, Sato N, Sawa Y, Shiose A, Shimizu W, Shimokawa H, Seino Y, Node K, Higo T, Hirayama A, Makaya M, Masuyama T, Murohara T, Mo, “JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure - Digest Version.,” Circ J., Vols. 83(10):2084-2184., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui H, Ide T, Ito H, Kihara Y, Kinugawa K, Kinugawa S, Makaya M, Murohara T, Node K, Saito Y, Sakata Y, Shimizu W, Yamamoto K, Bando Y, Iwasaki YK, Kinugasa Y, Mizote I, Nakagawa H, Oishi S, Okada A, Tanaka A, Akasaka T, Ono M, Kimura T, Kosaka S, Kos, “JCS/JHFS 2021 Guideline Focused Update on Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure.,” Circ J., Vols. 85(12):2252-2291., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid CM, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, Anker SD, Atherton J, Böhm M, Butler J, Drazner MH, Michael Felker G, Filippatos G, Fiuzat M, Fonarow GC, Gomez-Mesa JE, Heidenreich P, Imamura T, Jankowska EA, Januzzi J, Khazanie P, “Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition o,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 23(3):352-380., 2021.

- Blecker S, Katz SD, Horwitz LI, Kuperman G, Park H, Gold A, Sontag D. , “Comparison of Approaches for Heart Failure Case Identification From Electronic Health Record Data.,” JAMA Cardiol. , Vols. 1(9):1014-1020., 2016. [CrossRef]

- Volpe M, Carnovali M, Mastromarino V., “The natriuretic peptides system in the pathophysiology of heart failure: from molecular basis to treatment.,” Clin Sci (Lond), Vols. 130(2):57-77., 2016. [CrossRef]

- Maisel AS, Duran JM, Wettersten N., “Natriuretic Peptides in Heart Failure: Atrial and B-type Natriuretic Peptides.,” Heart Fail Clin., Vols. 14(1):13-25., 2018.

- Sudoh T, Maekawa K, Kojima M, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H., “Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA encoding a precursor for human brain natriuretic peptide.,” Biochem Biophys Res Commun, Vols. 159(3):1427-34., 1989. [CrossRef]

- McGrath MF, de Bold ML, de Bold AJ., “The endocrine function of the heart.,” Trends Endocrinol Metab., Vols. 16(10):469-77. , 2005.

- Vergani M, Cannistraci R, Perseghin G, Ciardullo S. , “The Role of Natriuretic Peptides in the Management of Heart Failure with a Focus on the Patient with Diabetes.,” J Clin Med., vol. 13(20):6225., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura M, Yasue H, Morita E, Sakaino N, Jougasaki M, Kurose M, Mukoyama M, Saito Y, Nakao K, Imura H. , “ Hemodynamic, renal, and hormonal responses to brain natriuretic peptide infusion in patients with congestive heart failure,” Circulation. , Vols. 84(4):1581-8., 1991. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa O, Ogawa Y, Itoh H, Suga S, Komatsu Y, Kishimoto I, Nishino K, Yoshimasa T, Nakao K, “Rapid transcriptional activation and early mRNA turnover of brain natriuretic peptide in cardiocyte hypertrophy. Evidence for brain natriuretic peptide as an “emergency” cardiac hormone against ventricular overload.,” J Clin Invest., Vols. 96(3):1280-7. , 1995.

- Smith MW, Espiner EA, Yandle TG, Charles CJ, Richards AM., “Delayed metabolism of human brain natriuretic peptide reflects resistance to neutral endopeptidase.,” J Endocrinol. , Vols. 167(2):239-46. , 2000. [CrossRef]

- Daniels LB, Maisel AS. , “Natriuretic peptides,” J Am Coll Cardiol, Vols. 50(25):2357-68. , 2007.

- Vickery S, Price CP, John RI, Abbas NA, Webb MC, Kempson ME, Lamb EJ., “B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and amino-terminal proBNP in patients with CKD: relationship to renal function and left ventricular hypertrophy.,” Am J Kidney Dis., Vols. 46(4):610-20., 2005. [CrossRef]

- Mueller C, McDonald K, de Boer RA, Maisel A, Cleland JGF, Kozhuharov N, Coats AJS, Metra M, Mebazaa A, Ruschitzka F, Lainscak M, Filippatos G, Seferovic PM, Meijers WC, Bayes-Genis A, Mueller T, Richards M, Januzzi JL Jr; Heart Failure Association of the , “Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 21(6):715-731. , 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fang M, Wang D, Tang O, McEvoy JW, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Christenson RH, Selvin E., “Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in US Adults With and Without Diabetes.,” J Am Heart Assoc., vol. 12(11):e029083., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Natriuretic Peptides Studies Collaboration, Willeit P, Kaptoge S, Welsh P, Butterworth AS, Chowdhury R, Spackman SA, Pennells L, Gao P, Burgess S, Freitag DF, Sweeting M, Wood AM, Cook NR, Judd S, Trompet S, Nambi V, Olsen MH, Everett BM, Kee F, Ärnlöv J,, “Natriuretic peptides and integrated risk assessment for cardiovascular disease: an individual-participant-data meta-analysis.,” Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. , Vols. 4(10):840-9. , 2016. [CrossRef]

- Cleland JGF, Pfeffer MA, Clark AL, Januzzi JL, McMurray JJV, Mueller C, Pellicori P, Richards M, Teerlink JR, Zannad F, Bauersachs J, “The struggle towards a Universal Definition of Heart Failure-how to proceed?,” Eur Heart J., Vols. 42(24):2331-2343., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pandey A, Berry JD, Drazner MH, Fang JC, Tang WHW, Grodin JL. , “Body Mass Index, Natriuretic Peptides, and Risk of Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: Analysis From the TOPCAT Trial.,” J Am Heart Assoc. , vol. 7(21):e009664., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ndumele CE, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Lazo M, Agarwal SK, Nambi V, Deswal A, Blumenthal RS, Ballantyne CM, Coresh J, Selvin E. , “N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide and Heart Failure Risk Among Individuals With and Without Obesity: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study.,” Circulation, Vols. 133(7):631-8., 2016.

- Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. , “Evidence Supporting the Existence of a Distinct Obese Phenotype of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction.,” Circulation, Vols. 136(1):6-19, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Welsh P, Campbell RT, Mooney L, Kimenai DM, Hayward C, Campbell A, Porteous D, Mills NL, Lang NN, Petrie MC, Januzzi JL, McMurray JJV, Sattar N. , “Reference Ranges for NT-proBNP (N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide) and Risk Factors for Higher NT-proBNP Concentrations in a Large General Population Cohort.,” Circ Heart Fail., vol. 15(10):e009427., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bayes-Genis A, Docherty KF, Petrie MC, Januzzi JL, Mueller C, Anderson L, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Christodorescu R, Del Prato S, Gustafsson F, Lam CSP, Moura B, Pop-Busui R, Seferovic P, Volterrani M, Vaduganathan M, Metra M, Rosano , “Practical algorithms for early diagnosis of heart failure and heart stress using NT-proBNP: A clinical consensus statement from the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 25(11):1891-1898. , 2023. [CrossRef]

- Januzzi JL Jr, Chen-Tournoux AA, Christenson RH, Doros G, Hollander JE, Levy PD, Nagurney JT, Nowak RM, Pang PS, Patel D, Peacock WF, Rivers EJ, Walters EL, Gaggin HK;, “ ICON-RELOADED Investigators. N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in the Emergency Department: The ICON-RELOADED Study.,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 71(11):1191-1200, 2018.

- Ianos RD, Iancu M, Pop C, Lucaciu RL, Hangan AC, Rahaian R, Cozma A, Negrean V, Mercea D, Procopciuc LM. , “Predictive Value of NT-proBNP, FGF21, Galectin-3 and Copeptin in Advanced Heart Failure in Patients with Preserved and Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.,” Medicina (Kaunas)., vol. 60(11):1841., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen DV, Nguyen SV, Pham AL, Nguyen BT, Hoang SV., “Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in the new era of heart failure treatment.,” PLoS One., vol. 19(9):e0309948. , 2024.

- Ammar LA, Massoud GP, Chidiac C, Booz GW, Altara R, Zouein FA. , “BNP and NT-proBNP as prognostic biomarkers for the prediction of adverse outcomes in HFpEF patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis.,” Heart Fail Rev, Vols. 30(1):45-54, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Goetze JP, Bruneau BG, Ramos HR, Ogawa T, de Bold MK, de Bold AJ. , “Cardiac natriuretic peptides.,” Nat Rev Cardiol., Vols. 17(11):698-717., 2020 .

- Maisel A, Mueller C, Nowak R, Peacock WF, Landsberg JW, Ponikowski P, Mockel M, Hogan C, Wu AH, Richards M, Clopton P, Filippatos GS, Di Somma S, Anand I, Ng L, Daniels LB, Neath SX, Christenson R, Potocki M, McCord J, Terracciano G, Kremastinos D, Hartma, “Mid-region pro-hormone markers for diagnosis and prognosis in acute dyspnea: results from the BACH (Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure) trial.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 55(19):2062-76. , 2010.

- Shah RV, Truong QA, Gaggin HK, Pfannkuche J, Hartmann O, Januzzi JL Jr., “Mid-regional pro-atrial natriuretic peptide and pro-adrenomedullin testing for the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of patients with acute dyspnoea.,” Eur Heart J., Vols. 33(17):2197-205. , 2012. [CrossRef]

- Masson S, Latini R, Carbonieri E, Moretti L, Rossi MG, Ciricugno S, Milani V, Marchioli R, Struck J, Bergmann A, Maggioni AP, Tognoni G, Tavazzi L; GISSI-HF Investigators., “The predictive value of stable precursor fragments of vasoactive peptides in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the GISSI-heart failure (GISSI-HF) trial.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 12(4):338-47. , 2010. [CrossRef]

- Carella M, Magro D, Scola L, Pisano C, Guida E, Gervasi F, Giambanco C, Aronica TS, Frati G, Balistreri CR., “Corrigendum to “CAR, mGPS and hs-mGPS: Which of these is the best gero-biomarker for age-related diseases? And for what clinical application?” [Mech. Aging Dev. 220 (2024) 111952].,” Mech Ageing Dev. , vol. 221:111977. , 2024.

- Wettersten N., “Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure: Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment.,” Int J Heart Fail., Vols. 3(2):81-105. , 2021.

- Awwad A, Parashar Y, Bagchi S, Siddiqui SA, Ajari O, deFilippi C., “Preclinical screening for cardiovascular disease with high-sensitivity cardiac troponins: ready, set, go?,” Front Cardiovasc Med., vol. 11:1350573, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Netala VR, Hou T, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Teertam SK., “Cardiovascular Biomarkers: Tools for Precision Diagnosis and Prognosis.,” Int J Mol Sci., vol. 26(7):3218., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Breha A, Delcea C, Ivanescu AC, Dan GA. , “The Prognostic Value of Troponin Levels Adjusted for Renal Function in Heart Failure - A Systematic Review.,” Rom J Intern Med. , Vols. 63(2):107-126., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lotfinaghsh A, Imam A, Pompian A, Stitziel NO, Javaheri A., “Clinical Insights from Proteomics in Heart Failure,” Curr Heart Fail Rep. , vol. 22(1):12., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lee HK, McCarthy CP, Jaffe AS, Body R, Alotaibi A, Sandoval Y, Januzzi JL Jr. , “High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Assays: From Implementation to Resource Utilization and Cost Effectiveness.,” J Appl Lab Med., Vols. 10(3):710-730. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Raber I, McCarthy CP, Januzzi JL Jr., “A Test in Context: Interpretation of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Assays in Different Clinical Settings.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 77(10):1357-1367. , 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim M, Ahmad J, Abbas M, Zainullah, Umar Z, Nasir M, Zain K, Ahmad J, Arshad S, Bashir A, Ullah S, Ahmad Z, Safdar S., “The Role of N-terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide, Troponins, and D-dimer in Acute Cardio-Respiratory Syndromes: A Multi-specialty Systematic Review.,” Cureus., vol. 17(5):e84460., 2025.

- Luo Q, Zhang Q, Kong Y, Wang S, Wei Q., “ Heart failure, inflammation and exercise.,” Int J Biol Sci., Vols. 21(8):3324-3350. , 2025.

- Mylavarapu M, Kodali LSM, Vempati R, Nagarajan JS, Vyas A, Desai R., “Circulating microRNAs in predicting fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review.,” World J Cardiol. , vol. 17(5):106123., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Roman-Pepine D, Serban AM, Capras RD, Cismaru CM, Filip AG., “A Comprehensive Review: Unraveling the Role of Inflammation in the Etiology of Heart Failure.,” Heart Fail Rev., 2025. [CrossRef]

- BaniHani HA, Khaled LH, Al Sharaa NM, Al Saleh RA, Bin Ghalaita AK, Bin Sulaiman AS, Holeihel A. , “Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis of Cardiac Fibrosis: A Systematic Review.,” Cureus, vol. 17(3):e81264, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shalmi TW, Jensen ASB, Goetze JP., “Cardiac natriuretic peptides.,” Adv Clin Chem, Vols. 122:115-139., 2024.

- Giovou AE, Gladka MM, Christoffels VM., “The Impact of Natriuretic Peptides on Heart Development, Homeostasis, and Disease.,” Cells., vol. 13(11):931. , 2024.

- Z. Q. K. Y. W. S. W. Q. Luo Q, “Heart failure, inflammation and exercise.,” Int J Biol Sci., Vols. 21(8):3324-3350., 2025.

- Cohn JN, Levine TB, Olivari MT, Garberg V, Lura D, Francis GS, Simon AB, Rector T. , “Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure.,” N Engl J Med., Vols. 311(13):819-23. , 1984. [CrossRef]

- Cabassi A, de Champlain J, Maggiore U, Parenti E, Coghi P, Vicini V, Tedeschi S, Cremaschi E, Binno S, Rocco R, Bonali S, Bianconcini M, Guerra C, Folesani G, Montanari A, Regolisti G, Fiaccadori E. , “Prealbumin improves death risk prediction of BNP-added Seattle Heart Failure Model: results from a pilot study in elderly chronic heart failure patients.,” Int J Cardiol., Vols. 168(4):3334-9., 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ceconi C, Ferrari R, Bachetti T, Opasich C, Volterrani M, Colombo B, Parrinello G, Corti A., “Chromogranin A in heart failure; a novel neurohumoral factor and a predictor for mortality.,” Eur Heart J, Vols. 23(12):967-74., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Røsjø H, Husberg C, Dahl MB, Stridsberg M, Sjaastad I, Finsen AV, Carlson CR, Oie E, Omland T, Christensen G., “Chromogranin B in heart failure: a putative cardiac biomarker expressed in the failing myocardium.,” Circ Heart Fail., Vols. 3(4):503-11, 2010.

- Azuma K, Nishimura K, Min KD, Takahashi K, Matsumoto Y, Eguchi A, Okuhara Y, Naito Y, Suna S, Asakura M, Ishihara M., “Plasma renin activity variation following admission predicts patient outcome in acute decompensated heart failure with reduced and mildly reduced ejection fraction.,” Heliyon., vol. 9(2):e13181., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan M, Cheema B, Cleveland E, Sankar K, Subacius H, Fonarow GC, Solomon SD, Lewis EF, Greene SJ, Maggioni AP, Böhm M, Zannad F, Butler J, Gheorghiade M. , “Plasma renin activity, response to aliskiren, and clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for heart failure: the ASTRONAUT trial,” Eur J Heart Fail, Vols. 20(4):677-686., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Voors AA, Kremer D, Geven C, Ter Maaten JM, Struck J, Bergmann A, Pickkers P, Metra M, Mebazaa A, Düngen HD, Butler J., “Adrenomedullin in heart failure: pathophysiology and therapeutic application,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 21(2):163-171. , 2019. [CrossRef]

- Richards AM, Doughty R, Nicholls MG, MacMahon S, Sharpe N, Murphy J, Espiner EA, Frampton C, Yandle TG; Australia-New Zealand Heart Failure Group., “Plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and adrenomedullin: prognostic utility and prediction of benefit from carvedilol in chronic ischemic left ventricular dysfunction.,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 37(7):1781-7., 2001.

- von Haehling S, Filippatos GS, Papassotiriou J, Cicoira M, Jankowska EA, Doehner W, Rozentryt P, Vassanelli C, Struck J, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P, Kremastinos D, Bergmann A, Morgenthaler NG, Anker SD. , “Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin as a novel predictor of mortality in patients with chronic heart failure.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 2(5):484-91., 2010. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee K., “Neurohormonal activation in congestive heart failure and the role of vasopressin.,” Am J Cardiol. , Vols. 95(9A):8B-13B., 2005. [CrossRef]

- Maisel A, Xue Y, Shah K, Mueller C, Nowak R, Peacock WF, Ponikowski P, Mockel M, Hogan C, Wu AH, Richards M, Clopton P, Filippatos GS, Di Somma S, Anand IS, Ng L, Daniels LB, Neath SX, Christenson R, Potocki M, McCord J, Terracciano G, Kremastinos D, Hart, “Increased 90-day mortality in patients with acute heart failure with elevated copeptin: secondary results from the Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure (BACH) study.,” Circ Heart Fail., Vols. 4(5):613-20., 2011.

- Zhong Y, Wang R, Yan L, Lin M, Liu X, You T., “Copeptin in heart failure: Review and meta-analysis.,” Clin Chim Acta, Vols. 475:36-43. , 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhang CL, Xie S, Qiao X, An YM, Zhang Y, Li L, Guo XB, Zhang FC, Wu LL. , “Plasma endothelin-1-related peptides as the prognostic biomarkers for heart failure: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis.,” Medicine (Baltimore)., vol. 96(50):e9342. , 2017.

- Perez AL, Grodin JL, Wu Y, Hernandez AF, Butler J, Metra M, Felker GM, Voors AA, McMurray JJ, Armstrong PW, Starling RC, O’Connor CM, Tang WH., “Increased mortality with elevated plasma endothelin-1 in acute heart failure: an ASCEND-HF biomarker substudy.,” Eur J Heart Fail, Vols. 18(3):290-7. , 2016. [CrossRef]

- Guo S, Hu Y, Ling L, Yang Z, Wan L, Yang X, Lei M, Guo X, Ren Z. , “Molecular mechanisms and intervention approaches of heart failure (Review),” Int J Mol Med., vol. 56(2):125., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Malik MK, Kinno M, Liebo M, Yu MD, Syed M, “Evolving role of myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.,” Front Cardiovasc Med., vol. 12:1573346., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ververeli CL, Dimitroglou Y, Soulaidopoulos S, Cholongitas E, Aggeli C, Tsioufis K, Tousoulis D., “Cardiac Remodeling and Arrhythmic Burden in Pre-Transplant Cirrhotic Patients: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Management Strategies.,” Biomedicines., vol. 13(4):812. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Vergaro G, Prud’homme M, Fazal L, Merval R, Passino C, Emdin M, Samuel JL, Cohen Solal A, Delcayre C., “Inhibition of Galectin-3 Pathway Prevents Isoproterenol-Induced Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Fibrosis in Mice.,” v, Vols. 67(3):606-12., 2016. [CrossRef]

- Meijers WC, Januzzi JL, deFilippi C, Adourian AS, Shah SJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, de Boer RA., “ Elevated plasma galectin-3 is associated with near-term rehospitalization in heart failure: a pooled analysis of 3 clinical trials.,” Am Heart J. , Vols. 167(6):853-60.e4., 2014. [CrossRef]

- Miró Ò, González de la Presa B, Herrero-Puente P, Fernández Bonifacio R, Möckel M, Mueller C, Casals G, Sandalinas S, Llorens P, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Jacob J, Bedini JL, Gil V., “The GALA study: relationship between galectin-3 serum levels and short- and long-term outcomes of patients with acute heart failure.,” Biomarkers, Vols. 22(8):731-739. , 2017. [CrossRef]

- Gehlken C, Suthahar N, Meijers WC, de Boer RA., “Galectin-3 in Heart Failure: An Update of the Last 3 Years.,” Heart Fail Clin., Vols. 14(1):75-92., 2018.

- Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Bayes-Genis A, Vergaro G, Sciarrone P, Passino C, Emdin M., “Clinical and Prognostic Significance of sST2 in Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week.,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 74(17):2193-2203. , 2019.

- Emdin M, Aimo A, Vergaro G, Bayes-Genis A, Lupón J, Latini R, Meessen J, Anand IS, Cohn JN, Gravning J, Gullestad L, Broch K, Ueland T, Nymo SH, Brunner-La Rocca HP, de Boer RA, Gaggin HK, Ripoli A, Passino C, Januzzi JL Jr., “sST2 Predicts Outcome in Chronic Heart Failure Beyond NT-proBNP and High-Sensitivity Troponin T.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 72(19):2309-2320., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Richards AM., “ST2 and Prognosis in Chronic Heart Failure.,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 72(19):2321-2323., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dalal JJ, Digrajkar A, Das B, Bansal M, Toomu A, Maisel AS. , “ST2 elevation in heart failure, predictive of a high early mortality.,” Indian Heart J., Vols. 70(6):822-827., 2018.

- Chen Y, Guan J, Qi C, Wu Y, Wang J, Zhao X, Li X, He C, Zhang J, Zhang Y. , “Association of point-of-care testing for sST2 with clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure,” ESC Heart Fail. , Vols. 11(5):2857-2868. , 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Zhao X, Liang L, Tian P, Feng J, Huang L, Huang B, Wu Y, Wang J, Guan J, Li X, Zhang J, Zhang Y., “sST2 and Big ET-1 as Alternatives of Multi-Biomarkers Strategies for Prognosis Evaluation in Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure.,” Int J Gen Med., Vols. 16:5003-5016., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Vergaro G, Richards AM, Lam CSP, Latini R, Anand IS, Cohn JN, Ueland T, Gullestad L, Aukrust P, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Bayes-Genis A, Lupón J, de Boer RA, Takeishi Y, Egstrup M, Gustafsson I, Gaggin HK, Eggers KM, Huber K, Gamble GD, , “Circulating levels and prognostic value of soluble ST2 in heart failure are less influenced by age than N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and high-sensitivity troponin T,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 22(11):2078-2088., 2020. [CrossRef]

- Aimo A, Maisel AS, Castiglione V, Emdin M., “sST2 for Outcome Prediction in Acute Heart Failure: Which Is the Best Cutoff?,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 74(3):478-479., 2019.

- Cotter G, Voors AA, Prescott MF, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, Pang PS, Ponikowski P, Milo O, Hua TA, Qian M, Severin TM, Teerlink JR, Metra M, Davison BA., “Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) in patients admitted for acute heart failure: results from the RELAX-AHF study.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 17(11):1133-43., 2015. [CrossRef]

- Santema BT, Chan MMY, Tromp J, Dokter M, van der Wal HH, Emmens JE, Takens J, Samani NJ, Ng LL, Lang CC, van der Meer P, Ter Maaten JM, Damman K, Dickstein K, Cleland JG, Zannad F, Anker SD, Metra M, van der Harst P, de Boer RA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Rienstr, “The influence of atrial fibrillation on the levels of NT-proBNP versus GDF-15 in patients with heart failure.,” Clin Res Cardiol., Vols. 109(3):331-338. , 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zile MR, Desantis SM, Baicu CF, Stroud RE, Thompson SB, McClure CD, Mehurg SM, Spinale FG., “Plasma biomarkers that reflect determinants of matrix composition identify the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic heart failure.,” Circ Heart Fail. , Vols. 4(3):246-56. , 2011. [CrossRef]

- Martin EM, Chang J, González A, Genovese F., “Circulating collagen type I fragments as specific biomarkers of cardiovascular outcome risk: Where are the opportunities?,” Matrix Biol., Vols. 137:19-32. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham JW, Claggett BL, O’Meara E, Prescott MF, Pfeffer MA, Shah SJ, Redfield MM, Zannad F, Chiang LM, Rizkala AR, Shi VC, Lefkowitz MP, Rouleau J, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Zile MR., “Effect of Sacubitril/Valsartan on Biomarkers of Extracellular Matrix Regulation in Patients With HFpEF.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 76(5):503-514, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sommakia S, Almaw NH, Lee SH, Ramadurai DKA, Taleb I, Kyriakopoulos CP, Stubben CJ, Ling J, Campbell RA, Alharethi RA, Caine WT, Navankasattusas S, Hoareau GL, Abraham AE, Fang JC, Selzman CH, Drakos SG, Chaudhuri D, “FGF21 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 21) Defines a Potential Cardiohepatic Signaling Circuit in End-Stage Heart Failure.,” Circ Heart Fail., vol. 15(3):e008910, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fan L, Gu L, Yao Y, Ma G., “Elevated Serum Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Is Relevant to Heart Failure Patients with Reduced Ejection Fraction.,” Comput Math Methods Med, vol. 2022:7138776., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gu L, Jiang W, Zheng R, Yao Y, Ma G., “Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Correlates with the Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy.,” Cardiology, Vols. 146(1):27-33., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ghazal R, Wang M, Liu D, Tschumperlin DJ, Pereira NL. , “Cardiac Fibrosis in the Multi-Omics Era: Implications for Heart Failure.,” Circ Res, Vols. 136(7):773-802., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Soejima H, Irie A, Fukunaga T, Oe Y, Kojima S, Kaikita K, Kawano H, Sugiyama S, Yoshimura M, Kishikawa H, Nishimura Y, Ogawa H., “Osteopontin expression of circulating T cells and plasma osteopontin levels are increased in relation to severity of heart failure.,” Circ J., Vols. 71(12):1879-84. , 2007. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Xie J, Chen J, Li R, Wu H, Zhang X, Chen Q, Gu R, Xu B., “Syndecan-4 deficiency accelerates the transition from compensated hypertrophy to heart failure following pressure overload.,” Cardiovasc Pathol., Vols. 28:74-79, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lim S, McMahon CD, Matthews KG, Devlin GP, Elston MS, Conaglen JV. , “Absence of Myostatin Improves Cardiac Function Following Myocardial Infarction.,” Heart Lung Circ., Vols. 27(6):693-701. , 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chen P, Liu Z, Luo Y, Chen L, Li S, Pan Y, Lei X, Wu D, Xu D., “Predictive value of serum myostatin for the severity and clinical outcome of heart failure.,” Eur J Intern Med. , Vols. 64:33-40., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Xu X, Shang R, Chen Y. , “Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) as an important risk factor for the increased cardiovascular diseases and heart failure in chronic kidney disease.,” Nitric Oxide., Vols. 78:113-120., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis S, Veljkovic A, Georgianos PI, Lazarevic G, Perisic Z, Hadzi-Djokic J, Liakopoulos V, Kocic G., “Association between Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation with Cardiac Necrosis and Heart Failure in Non-ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients and Various Degrees of Kidney Function.,” Oxid Med Cell Longev., vol. 2021:3090120., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liberale L, Duncker DJ, Hausenloy DJ, Kraler S, Bøtker HE, Podesser BK, Heusch G, Kleinbongard P., “Vascular (dys)function in the failing heart.,” Nat Rev Cardiol. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Andreadou I, Ghigo A, Nikolaou PE, Swirski FK, Thackeray JT, Heusch G, Vilahur G., “Immunometabolism in heart failure.,” Nat Rev Cardiol., 2025.

- Nägele H, Bahlo M, Klapdor R, Schaeperkoetter D, Rödiger W. , “CA 125 and its relation to cardiac function.,” Am Heart J., Vols. 137(6):1044-9., 1999. [CrossRef]

- Núñez J, Miñana G, González M, Garcia-Ramón R, Sanchis J, Bodí V, Núñez E, Chorro FJ, Llàcer A, Miguel A. , “Antigen carbohydrate 125 in heart failure: not just a surrogate for serosal effusions?,” Int J Cardiol, Vols. 146(3):473-4. , 2011. [CrossRef]

- Marinescu MC, Oprea VD, Munteanu SN, Nechita A, Tutunaru D, Nechita LC, Romila A., “Carbohydrate Antigen 125 (CA 125): A Novel Biomarker in Acute Heart Failure.,” Diagnostics (Basel)., vol. 14(8):795., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Carella M, Magro D, Scola L, Pisano C, Guida E, Gervasi F, Giambanco C, Aronica TS, Frati G, Balistreri CR., “CAR, mGPS and hs-mGPS: What is among them the best gero-biomarker for age-related diseases? And for what clinical application?,” Mech Ageing Dev., vol. 220:111952., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Di Rosa M, Sabbatinelli J, Giuliani A, Carella M, Magro D, Biscetti L, Soraci L, Spannella F, Fedecostante M, Lenci F, Tortato E, Pimpini L, Burattini M, Cecchini S, Cherubini A, Bonfigli AR, Capalbo M, Procopio AD, Balistreri CR, Olivieri F. , “Inflammation scores based on C-reactive protein and albumin predict mortality in hospitalized older patients independent of the admission diagnosis.,” Immun Ageing., vol. 21(1):67., 2024.

- Kurniawan RB, Oktafia P, Saputra PBT, Purwati DD, Saputra ME, Maghfirah I, Faizah NN, Oktaviono YH, Alkaff FF. , “The roles of C-reactive protein-albumin ratio as a novel prognostic biomarker in heart failure patients: A systematic review.,” Curr Probl Cardiol., vol. 49(5):102475., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri A, Soltani S, Asoudeh F, Esmaillzadeh A., “Effects of omega-3 supplementation on serum albumin, pre-albumin and the CRP/albumin ratio in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis.,” Nutr Rev. , Vols. 81(3):237-251. , 2023. [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento DM, Bock PM, Nemetz B, Goldraich LA, Schaan BD., “Meta-Analysis of Physical Training on Natriuretic Peptides and Inflammation in Heart Failure.,” Am J Cardiol., Vols. 178:60-71. , 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rawat A, Vyas K., “ Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Predictor of Mortality and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients.,” Cureus. , vol. 17(5):e83359., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Li D, Du Y., “Prognostic value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for cardiovascular diseases: research progress.,” Am J Transl Res. , Vols. 17(2):1170-1177. , 2025.

- Ang SP, Chia JE, Jaiswal V, Hanif M, Iglesias J., “Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis.,” J Clin Med. , vol. 13(5):1212., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vakhshoori M, Nemati S, Sabouhi S, Yavari B, Shakarami M, Bondariyan N, Emami SA, Shafie D., “Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) prognostic effects on heart failure; a systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMC Cardiovasc Disord., vol. 23(1):555. , 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zadorozny L, Du J, Supanekar N, Annamalai K, Yu Q, Wang M. , “Caveolin and oxidative stress in cardiac pathology.,” Front Physiol. , vol. 16:1550647., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kittipibul V, Ambrosy AP, Greene SJ. , “Myeloperoxidase inhibition in the landscape of anti-inflammatory therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the ENDEAVOR trial.,” Heart Fail Rev. , Vols. 30(4):735-738., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yu F, Zhao H, Luo L, Wu W. , “Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Supplementation to Alleviate Heart Failure: A Mitochondrial Dysfunction Perspective.,” Nutrients., vol. 17(11):1855. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dan LX, Xie SP. , “Autophagy in cardiac pathophysiology: Navigating the complex roles and therapeutic potential in cardiac fibrosis.,” Life Sci., vol. 123761, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sen I, Trzaskalski NA, Hsiao YT, Liu PP, Shimizu I, Derumeaux GA., “Aging at the Crossroads of Organ Interactions: Implications for the Heart.,” Circ Res., Vols. 136(11):1286-1305., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Wang C, Xu Y, Wang H, Wang X. , “Network pharmacology and bioinformatics analysis reveals: NXC improves cardiac lymphangiogenesis through miR-126-3p/SPRED1 regulating the VEGF-C axis to ameliorate post-myocardial infarction heart failure.,” J Ethnopharmacol., vol. 350:119959., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen YL, Lin YN, Xu J, Qiu YX, Wu YH, Qian XG, Wu YQ, Wang ZN, Zhang WW, Li YC., “Macrophage-derived VEGF-C reduces cardiac inflammation and prevents heart dysfunction in CVB3-induced viral myocarditis via remodeling cardiac lymphatic vessels.,” Int Immunopharmacol., vol. 143(Pt 1):113377. , 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mericskay M, Zuurbier CJ, Heather LC, Karlstaedt A, Inserte J, Bertrand L, Kararigas G, Ruiz-Meana M, Maack C, Schiattarella GG. , “Cardiac intermediary metabolism in heart failure: substrate use, signalling roles and therapeutic targets.,” Nat Rev Cardiol., 2025.

- Auerbach M, DeLoughery TG, Tirnauer JS., “Iron Deficiency in Adults: A Review.,” JAMA, Vols. 333(20):1813-1823., 2025.

- Anghel L, Dinu C, Patraș D, Ciubară A, Chiscop I., “Iron Deficiency Treatment in Heart Failure-Challenges and Therapeutic Solutions.,” J Clin Med., vol. 14(9):2934., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Maidana D, Arroyo-Álvarez A, Barreres-Martín G, Arenas-Loriente A, Cepas-Guillen P, Brigolin Garofo RT, Caravaca-Pérez P, Bonanad C. , “Targeting Inflammation and Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: A Focus on Older Adults.,” Biomedicines., vol. 13(2):462., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Maack C., “Metabolic alterations in heart failure.,” Nat Rev Cardiol., 2025.

- Ibrahim R, Takamatsu C, Alabagi A, Pham HN, Thajudeen B, Demirjian S, Tang WHW, William P, “Kidney Replacement Therapies in Advanced Heart Failure: Timing, Modalities and Clinical Considerations.,” J Card Fail. , Vols. 31(5):833-844. , 2025.

- Giangregorio F, Mosconi E, Debellis MG, Provini S, Esposito C, Garolfi M, Oraka S, Kaloudi O, Mustafazade G, Marín-Baselga R, Tung-Chen Y. , “A Systematic Review of Metabolic Syndrome: Key Correlated Pathologies and Non-Invasive Diagnostic Approaches.,” J Clin Med. , vol. 13(19):5880., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bansal B, Lajeunesse-Trempe F, Keshvani N, Lavie CJ, Pandey A., “Impact of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease on Cardiovascular Structure, Function, and the Risk of Heart Failure.,” Can J Cardiol., 2025.

- Bernhard J, Galli L, Speidl WS, Krychtiuk KA., “Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis.,” Curr Cardiol Rep. , vol. 27(1):28. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Savarese G, von Haehling S, Butler J, Cleland JGF, Ponikowski P, Anker SD., “Iron deficiency and cardiovascular disease.,” Eur Heart J., Vols. 44(1):14-27, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghafourian K, Shapiro JS, Goodman L, Ardehali H., “Iron and Heart Failure: Diagnosis, Therapies, and Future Directions.,” JACC Basic Transl Sci., Vols. 5(3):300-313. , 2020.

- McDonagh T, Damy T, Doehner W, Lam CSP, Sindone A, van der Meer P, Cohen-Solal A, Kindermann I, Manito N, Pfister O, Pohjantähti-Maaroos H, Taylor J, Comin-Colet J. , “Screening, diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: putting the 2016 European Society of Cardiology heart failure guidelines into clinical practice.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 20(12):1664-1672. , 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lam CSP, Doehner W, Comin-Colet J; IRON CORE Group, “ Iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: case-based practical guidance.,” ESC Heart Fail. , Vols. 5(5):764-771., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Grote Beverborg N, Klip IT, Meijers WC, Voors AA, Vegter EL, van der Wal HH, Swinkels DW, van Pelt J, Mulder AB, Bulstra SK, Vellenga E, Mariani MA, de Boer RA, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P., “Definition of Iron Deficiency Based on the Gold Standard of Bone Marrow Iron Staining in Heart Failure Patients.,” Circ Heart Fail., vol. 11(2):e004519., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gan S, Azzo JD, Zhao L, Pourmussa B, Dib MJ, Salman O, Erten O, Ebert C, Richards AM, Javaheri A, Mann DL, Rietzschel E, Zamani P, van Empel V, Cappola TP, Chirinos JA. , “Transferrin Saturation, Serum Iron, and Ferritin in Heart Failure: Prognostic Significance and Proteomic Associations.,” Circ Heart Fail., vol. 18(2):e011728. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Graham FJ, Guha K, Cleland JG, Kalra PR., “Treating iron deficiency in patients with heart failure: what, why, when, how, where and who.,” Heart. , Vols. 110(20):1201-1207. , 2024.

- von Haehling S, Ebner N, Evertz R, Ponikowski P, Anker SD., “Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: An Overview.,” JACC Heart Fail. , Vols. 7(1):36-46. , 2019.

- Dinatolo E, Dasseni N, Metra M, Lombardi C, von Haehling S., “Iron deficiency in heart failure.,” J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). , Vols. 19(12):706-716., 2018.

- Gamage M, Manouras A, Hage C, Savarese G, Ljung K, Melin M., “Implementation of guidelines for intravenous iron therapy in heart failure patients.,” ESC Heart Fail. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sindone A, Doehner W, Comin-Colet J. , “Systematic review and meta-analysis of intravenous iron-carbohydrate complexes in HFrEF patients with iron deficiency.,” ESC Heart Fail., Vols. 10(1):44-56., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pezel T, Audureau E, Mansourati J, Baudry G, Ben Driss A, Durup F, Fertin M, Godreuil C, Jeanneteau J, Kloeckner M, Koukoui F, Kesri-Tartière L, Laperche T, Roubille F, Cohen-Solal A, Damy T. , “Diagnosis and Treatment of Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: OFICSel study by the French Heart Failure Working Group.,” ESC Heart Fail., Vols. 8(2):1509-1521., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Houstis NE, Cunningham TF, Brooks LC, Chen K, Slocum CL, Ostrom K, Birchenough C, Moore E, Tattersfield H, Sigurslid H, Guo Y, Landsteiner I, Rouvina JN, Lewis GD, Malhotra R., “Transferrin Saturation Is a Better Predictor Than Ferritin of Metabolic and Hemodynamic Exercise Responses in HFpEF.,” JACC Heart Fail. , vol. 13(8):102478., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Aboelsaad IAF, Claggett BL, Arthur V, Dorbala P, Matsushita K, Lutsey PL, Yu B, Lennep BW, Ndumele CE, Farag YMK, Shah AM, Buckley LF., “Hepcidin, Incident Heart Failure and Cardiac Dysfunction in Older Adults: the ARIC Study.,” Eur J Prev Cardiol., vol. zwaf018. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Busti F, Borella N, Scoccia E, Pecoraro B, Sani E, Morandin R, Csermely A, Piasentin D, Grespan E, Castagna A, Bilson J, Byrne CD, Valenti L, Girelli D, Targher G. , “Elevated plasma hepcidin concentrations are associated with an increased risk of mortality and nonfatal cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a prospective study.,” Cardiovasc Diabetol., vol. 23(1):305., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Valenti AC, Vitolo M, Imberti JF, Malavasi VL, Boriani G., “Red Cell Distribution Width: A Routinely Available Biomarker with Important Clinical Implications in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation.,” Curr Pharm Des., Vols. 27(37):3901-3912., 2021. [CrossRef]

- García-Escobar A, Lázaro-García R, Goicolea-Ruigómez J, González-Casal D, Fontenla-Cerezuela A, Soto N, González-Panizo J, Datino T, Pizarro G, Moreno R, Cabrera JÁ. , “Red Blood Cell Distribution Width is a Biomarker of Red Cell Dysfunction Associated with High Systemic Inflammation and a Prognostic Marker in Heart Failure and Cardiovascular Disease: A Potential Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence.,” High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev, Vols. 31(5):437-449. , 2024. [CrossRef]

- Masini G, Graham FJ, Pellicori P, Cleland JGF, Cuthbert JJ, Kazmi S, Inciardi RM, Clark AL., “Criteria for Iron Deficiency in Patients With Heart Failure.,” J Am Coll Cardiol., Vols. 79(4):341-351. , 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pinsino A, Carey MR, Husain S, Mohan S, Radhakrishnan J, Jennings DL, Nguonly AS, Ladanyi A, Braghieri L, Takeda K, Faillace RT, Sayer GT, Uriel N, Colombo PC, Yuzefpolskaya M. , “The Difference Between Cystatin C- and Creatinine-Based Estimated GFR in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: Insights From PARADIGM-HF.,” Am J Kidney Dis., Vols. 82(5):521-533., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Łagosz P, Biegus J, Urban S, Zymliński R. , “Renal Assessment in Acute Cardiorenal Syndrome.,” Biomolecules. , vol. 13(2):239. , 2023. [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis N, Nikolaou M., “Integrated Management of Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic Syndrome: Expanding Roles of SGLT2is, GLP-1RAs, and GIP/GLP-1RAs.,” Biomedicines. , vol. 13(1):135., 2025.

- Cheng Z, Lin X, Xu C, Zhang Z, Lin N, Cai K., “Prognostic Value of Serum Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Acute Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis.,” Rev Cardiovasc Med. , vol. 25(12):428., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis N, Nikolaou M., “From Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome to Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic Syndrome: Proposing an Expanded Framework.,” Biomolecules., vol. 15(2):213., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bastos JM, Colaço B, Baptista R, Gavina C, Vitorino R., “Innovations in heart failure management: The role of cutting-edge biomarkers and multi-omics integration,” J Mol Cell Cardiol Plus., vol. 11:100290., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Massaccesi L, Balistreri CR. , “Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Acute and Chronic Diseases.,” Antioxidants (Basel)., vol. 11(9):1766., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Carella M, Porreca A, Piazza C, Gervasi F, Magro D, Venezia M, Verso RL, Vitale G, Agnello AG, Scola L, Aronica TS, Balistreri CR. , “Could the Combination of eGFR and mGPS Facilitate the Differential Diagnosis of Age-Related Renal Decline from Diseases? A Large Study on the Population of Western Sicily.,” J Clin Med., vol. 12(23):7352., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sarhene M, Wang Y, Wei J, Huang Y, Li M, Li L, Acheampong E, Zhengcan Z, Xiaoyan Q, Yunsheng X, Jingyuan M, Xiumei G, Guanwei F., “Biomarkers in heart failure: the past, current and future.,” Heart Fail Rev, Vols. 24(6):867-903., 2019.

- Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, Shah SJ, Anand IS, O’Meara E, Desai AS, Heitner JF, Li G, Fang J, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Markov V, Ryabov V, Reis G, Assmann SF, McKinlay SM, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD., “Cardiac structure and function and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the echocardiographic study of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) Trial.,” Circ Heart Fail. , Vols. 7(5):740-51., 2014.

- Abreu J, Seringa J, Magalhaes T., “Machine learning methods, applications and economic analysis to predict heart failure hospitalisation risk: a scoping review.,” BMJ Open, vol. 15(6):e093495., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sharda M, Sharma S, Raikar S, Verhagen N, Wagle J, Mathur R, Gowda S, Kommu S, Prasad R, Bhandari S, Jha P., “The Role of Machine Learning in Predicting Hospital Readmissions Among General Internal Medicine Patients: A Systematic Review.,” Cureus., vol. 17(5):e84761., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Loscalzo J, Mahmud AKMF, Aly DM, Rzhetsky A, Zitnik M, Benson M., “Digital twins as global learning health and disease models for preventive and personalized medicine.,” Genome Med. , vol. 17(1):11., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Palaparthi EC, Aditya Reddy P, Padala T, Sri Venkata Mahi Karthika K, Paka R, Ami Reddy V, Ayub S, Khyati Sri V, Rebanth Nandan V, Patnaik PK, Medabala T, Sayana SB. , “The Rise of Personalized Medicine in Heart Failure Management: A Narrative Review.,” Cureus., vol. 17(5):e83731., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Palaparthi EC, Padala T, Singamaneni R, Manaswini R, Kantula A, Aditya Reddy P, Chandini P, Sathwika Eliana A, Siri Samhita P, Patnaik PK., “Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review of Novel Pharmacological and Molecular Targets.,” Cureus., vol. 17(4):e81573., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Magro D, Venezia M, Balistreri CR, “The omics technologies and liquid biopsies: Advantages, limitations, applications, Medicine in Omics,,” Medicine in Omics, vol. 11, 2024.

- Rai H, Colleran R, Cassese S, Joner M, Kastrati A, Byrne RA. , “Association of interleukin 6 -174 G/C polymorphism with coronary artery disease and circulating IL-6 levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis.,” Inflamm Res., Vols. 70(10-12):1075-1087., 2021. [CrossRef]

- McCrink KA, Lymperopoulos A, “β1-adrenoceptor Arg389Gly polymorphism and heart disease: marching toward clinical practice integration.,” Pharmacogenomics., Vols. 16(10):1035-8. , 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ha SK. , “ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism and diabetic nephropathy: clinical implications of genetic information.,” J Diabetes Res., vol. 2014:846068., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee DSM, Cardone KM, Zhang DY, Tsao NL, Abramowitz S, Sharma P, DePaolo JS, Conery M, Aragam KG, Biddinger K, Dilitikas O, Hoffman-Andrews L, Judy RL, Khan A, Kullo IJ, Puckelwartz MJ, Reza N, Satterfield BA, Singhal P; Penn Medicine Biobank; Arany Z, Cap, “Common-variant and rare-variant genetic architecture of heart failure across the allele-frequency spectrum,” Nat Genet., Vols. 57(4):829-838. , 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu RF, Cretoiu SM., “MicroRNAs as monitoring markers for right-sided heart failure and congestive hepatopathy.,” J Med Life, Vols. 14(2):142-147., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Huang XH, Li JL, Li XY, Wang SX, Jiao ZH, Li SQ, Liu J, Ding J., “miR-208a in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Remodeling.,” Front Cardiovasc Med., vol. 8:773314., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Asjad E, Dobrzynski H. , “MicroRNAs: Midfielders of Cardiac Health, Disease and Treatment.,” Int J Mol Sci., vol. 24(22):16207., 2023.

- Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM, Creemers EE., “Circulating microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for cardiovascular diseases,” Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol., Vols. 303(9):H1085-95., 2012. [CrossRef]

- Colpaert RMW, Calore M., “MicroRNAs in Cardiac Diseases.,” Cells, vol. 8(7):737., 2019.

- Moradi A, Khoshniyat S, Nzeako T, Khazeei Tabari MA, Olanisa OO, Tabbaa K, Alkowati H, Askarianfard M, Daoud D, Oyesanmi O, Rodriguez A, Lin Y. , “The Future of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 Gene Therapy in Cardiomyopathies: A Review of Its Therapeutic Potential and Emerging Applications.,” Cureus., vol. 17(2):e79372., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Frommelt PC, Pearson GD, Mahle WT, Chen S, Dunbar-Masterson C, Mital S, Williams IA, Ghanayem NS, Goldberg CS, Jacobs JP, Krawczeski CD, Lewis AB, Pasquali SK, Pizarro C, Gruber PJ, Atz AM, Khaikin S, Gaynor JW, Ohye RG; Pediatri, “Transplantation-free survival and interventions at 3 years in the single ventricle reconstruction trial.,” Circulation, Vols. 129(20):2013-20., 2014. [CrossRef]

- Atz AM, Zak V, Mahony L, Uzark K, D’agincourt N, Goldberg DJ, Williams RV, Breitbart RE, Colan SD, Burns KM, Margossian R, Henderson HT, Korsin R, Marino BS, Daniels K, McCrindle BW; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. , “Longitudinal Outcomes of Patients With Single Ventricle After the Fontan Procedure.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 69(22):2735-2744. , 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Eitoku T, Ousaka D, Kondo M, Kurita Y, Hirai K, Fukushima Y, Baba K, Goto T, Horio N, Kobayashi J, Kuroko Y, Kotani Y, Arai S, Iwasaki T, Sato S, Kasahara S, Sano S, Oh H., “Intracoronary Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Single Ventricle Physiology: The PERSEUS (Cardiac Progenitor Cell Infusion to Treat Univentricular Heart Disease) Randomized Phase 2 Trial.,” Circ Res. , Vols. 120(7):1162-1173. , 2017.

- Balistreri CR., “In reviewing the emerging biomarkers of human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) and their vesicles as potential biomarkers of cardiovascular manifestations and targets for personalized treatments.,” Mech Ageing Dev. , vol. 222:112006. , 2024. [CrossRef]

- Balistreri CR, Buffa S, Pisano C, Lio D, Ruvolo G, Mazzesi G. , “Are Endothelial Progenitor Cells the Real Solution for Cardiovascular Diseases? Focus on Controversies and Perspectives.,” Biomed Res Int., vol. 2015:835934. , 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dorsheimer L, Assmus B, Rasper T, Ortmann CA, Ecke A, Abou-El-Ardat K, Schmid T, Brüne B, Wagner S, Serve H, Hoffmann J, Seeger F, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Rieger MA., “Association of Mutations Contributing to Clonal Hematopoiesis With Prognosis in Chronic Ischemic Heart Failure.,” JAMA Cardiol., Vols. 4(1):25-33., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Figal DA, Bayes-Genis A, Díez-Díez M, Hernández-Vicente Á, Vázquez-Andrés D, de la Barrera J, Vazquez E, Quintas A, Zuriaga MA, Asensio-López MC, Dopazo A, Sánchez-Cabo F, Fuster JJ. , “Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Progression of Heart Failure With Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 77(14):1747-1759., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Assmus B, Cremer S, Kirschbaum K, Culmann D, Kiefer K, Dorsheimer L, Rasper T, Abou-El-Ardat K, Herrmann E, Berkowitsch A, Hoffmann J, Seeger F, Mas-Peiro S, Rieger MA, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM., “Clonal haematopoiesis in chronic ischaemic heart failure: prognostic role of clone size for DNMT3A- and TET2-driver gene mutations.,” Eur Heart J., Vols. 42(3):257-265., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yu B, Roberts MB, Raffield LM, Zekavat SM, Nguyen NQH, Biggs ML, Brown MR, Griffin G, Desai P, Correa A, Morrison AC, Shah AM, Niroula A, Uddin MM, Honigberg MC, Ebert BL, Psaty BM, Whitsel EA, Manson JE, Kooperberg C, Bick AG, Ballantyne CM, Reiner AP, N, “Supplemental Association of Clonal Hematopoiesis With Incident Heart Failure.,” J Am Coll Cardiol. , Vols. 78(1):42-52., 2021.

- Scolari FL, Abelson S, Brahmbhatt DH, Medeiros JJF, Fan CS, Fung NL, Mihajlovic V, Anker MS, Otsuki M, Lawler PR, Ross HJ, Luk AC, Anker S, Dick JE, Billia F., “Clonal haematopoiesis is associated with higher mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock.,” Eur J Heart Fail., Vols. 24(9):1573-1582., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Schuermans A, Honigberg MC, Raffield LM, Yu B, Roberts MB, Kooperberg C, Desai P, Carson AP, Shah AM, Ballantyne CM, Bick AG, Natarajan P, Manson JE, Whitsel EA, Eaton CB, Reiner AP. , “Clonal Hematopoiesis and Incident Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction.,” JAMA Netw Open., vol. 7(1):e2353244. , 2024. [CrossRef]

| Guideline | Definition criterion | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 ACCF/AHA [13] | Presence of clinical symptoms and classification based on EF values | • HF is a complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood. • There is no single diagnostic test for HF because it is largely a clinical diagnosis based on careful history and physical examination. EF is considered important in classification of patients with HF because of differing patient demographics, comorbid, conditions, prognosis, and response to therapies. |

|

2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA [14] |

Clinical definition Distinction into 4 different stages to emphasize the development and progression of the disease Classification based on EF values |

HF is a complex clinical syndrome with symptoms and signs that result from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood. Therapeutic interventions in each stage aim to modify risk factors (stage A, at risk of heart failure), treat risk and structural heart disease to prevent HF (stage B, Pre-heart failure), and reduce symptoms, morbidity, and mortality (stages C, symptomatic heart failure and D, Advanced heart failure). |

| 2012 ESC [15] | Presence of specific clinical symptoms and signs and reduction of EF. If EF is preserved, relevant structural heart disease and/or diastolic dysfunction must be present. |

HF is defined, clinically, as a syndrome in which patients have typical symptoms (e.g. breathlessness, ankle swelling, and fatigue) and signs (e.g. elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary crackles, and displaced apex beat) resulting from an abnormality of cardiac structure or function. |

| 2016 ESC [16] | Presence of symptoms and/or clinical signs and reduction of EF. If this is mildly reduced or preserved, the following must be present: - elevated natriuretic peptide values - one of the following conditions: 1- relevant structural heart disease diastolic disfunction |

HF is a clinical syndrome characterized by typical symptoms (e.g. breathlessness, ankle swelling and fatigue) that may be accompanied by signs (e.g. elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary crackles and peripheral oedema) caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality, resulting in a reduced cardiac output and/or elevated intracardiac pressures at rest or during stress. |

| 2021 ESC [17] | Presence of symptoms and/or clinical signs and reduction of EF. If EF is preserved, it is necessary that there is objective evidence of cardiac structural and/or functional abnormalities consistent with the presence of LV diastolic dysfunction/raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptides. |

Heart failure is not a single pathological diagnosis, but a clinical syndrome consisting of cardinal symptoms (e.g. breathlessness, ankle swelling, and fatigue) that may be accompanied by signs (e.g. elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary crackles, and peripheral oedema). It is due to a structural and/or functional abnormality of the heart that results in elevated intracardiac pressures and/or inadequate cardiac output at rest and/or during exercise. |

| 2017 JCS/JHFS [18] | Presence of clinical symptoms and classification based on EF values | HF is defined as a clinical syndrome consisting of dyspnoea, malaise, swelling and/or decreased exercise capacity due to the loss of compensation for cardiac pumping function due to structural and/or functional abnormalities of the heart. |

| 2021 JCS/JHFS [19] | Presence of clinical symptoms and/or signs, personal and family history, ECG, chest X-ray and only lastly evaluation of markers (BNP, NT-proBNP). | HF is defined as a clinical syndrome consisting of dyspnoea, malaise, swelling, and/or decreased exercise capacity owing to the loss of compensation for cardiac pumping function owing to structural and/or functional abnormalities of the heart |

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| • Early diagnosis marker in patients with diabetes in the absence of a clear clinical expression of heart failure | • The increase in BNP and NT-proBNP may also depend on other comorbidities such as chronic renal failure or atrial fibrillation |

| • In the absence of a defined cardiovascular pathology, the dosage of NT-proBNP values could predict the onset of heart failure, coronary artery disease and stroke | • The value of NT-proBNP should also be correlated with age, sex and BMI |

| • NT-proBNP values are significantly associated with increased odds of advanced HF | • There is a significant “grey area” in which the diagnosis is rather indeterminate |

| • Correlation between NT-proBNP values and the risk of adverse events in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. |

| Biomarker | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| MR-pro-ANP | • capability to predict stable chronic HF | • performance diminished in patients with BNP and NT-pro-BNP values within the ‘gray-zone’ • same interferences as the assays for BNP and NT-pro-BNP |

| cTn | • predict new HF • elevated levels are associated with advanced HF, poor prognosis, mortality risk and development of HF in subjects with previous acute myocardial infarction • In patients with acute HF → frequent hospital admissions, increased intensive care unit admissions and in-hospital mortality. • in patients with chronic HFrEF → increased long-term mortality and a higher risk of HF rehospitalization |

• different values based on sex and race • increase in serum values in the case of cardiovascular diseases not related to HF but also in non-cardiovascular diseases |

| Norepinephrine | • good predictor of prognosis | • no better prognostic performance than BNP |

| Chromogranin A-B | • expression proportional to the severity of HF | few studies available |

| PRA | • independent predictor of cardiac death | few studies available |

| ADM | • plasma concentrations increase in case of HF | • routine dosing limited by its short half-life and binding to transport proteins |

| MR-proADM | • good predictor of survival | few studies available |

| Copeptin | • good predictor of mortality | |

| Urocortin-1 | • Circulating levels increase in HF | • not appear to have additional diagnostic or prognostic value over NT-proBNP |

| Gal-3 | • Levels are helpful for short-term mortality and rehospitalization. • The prognostic power is more significant in HFpEF |

• Levels vary by sex and increase with age and in other conditions, such as systemic inflammation and renal failure. |

| sST2 | • repeated measurement is useful in prognostic stratification and predicted rehospitalization especially in chronic HF • an independent predictor of reverse remodeling |

• insufficient evidence to recommend its use in clinical practice • no unanimous consensus on the best prognostic cut-off in chronic HF |

| GDF-15 | • elevated levels in HF patients may be detected as early as 90 days before hospital admission | • conflicting data regarding the cardioprotective role |

| MMPs/TIMPs | • concentration probably reflects the extent of cardiac tissue remodeling, with important prognostic implications. | few studies available |

| FGF21 | • levels are strongly linked to left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and patients with higher levels show an increased risk of cardiac death and high levels are independent of other comorbidities | few studies available |

| OPN | • excellent prognostic biomarker | few studies available |

| SDC-4 | • its increased levels are significantly associated with left ventricular hypertrophy | few studies available |

| MSTN | • levels are significantly associated with a lower survival rate and a higher number of rehospitalizations | few studies available |

| CRP | • prognostic role • associated with an increased risk of developing HF in elderly subjects |

• poor specificity |

| CA125 | • • potential role in clinical management (monitoring of decongestant therapy) and prognosis | • further studies are needed to establish reference intervals for for diagnosis and treatment monitoring. |

| CAR | • In chronic HF, high levels are associated with elevated PAPs- LVESV and decreased TAPSE. | few studies available |

| NLR | • elevated levels can predict a raised risk of short- and long-term mortality and adverse outcome in patients with acute HF | few studies available |

| MPO | • Plasma concentration increases in chronic HF • Independent predictor of 1-year mortality compared with BNP |

few studies available |

| miRNA | Role |

|---|---|

| mir-22 | • regulates calcium reuptake by sarcoplasmic reticulum • associated with hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis |

| miR-133/miR-223-3p | • their silencing reduces GLUT4 expression and thus increases myocardial glucose uptake in HF patients. |

| miR-21 | • involved in HF-related fibrosis through the stimulation of the ERK-MAP pathway |

| miR-1 | • involved in regulating myocardial hypertrophy |

| miR-212/132 | • associated with cardiac hypertrophy and HF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).