1. Introduction

Climate change is increasingly affecting terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, with extreme climatic events such as heatwaves and prolonged droughts posing significant challenges to environmental and cultural heritage conservation. Among the most affected systems are lakes, which act as sensitive indicators of climate variability due to their responsiveness to changes in temperature, precipitation, and stratification patterns [

1,

2]. These alterations can significantly influence biogeochemical processes, biodiversity, and the ecological status of lake environments [

3,

4].

In particular, lakes respond rapidly to climate fluctuations, reflecting changes occurring in their catchments [

2]. Higher air temperatures increase evapotranspiration and contribute to declining water levels. They also disrupt thermal stratification and convective mixing processes, which can lead to reduced dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations and altered nutrient cycling [

5]. These changes may result in eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, and shifts in trophic structure and community composition [

6,

7,

8]. Heatwaves, in particular, have been shown to suppress total community biomass, especially among zooplankton, and impair ecosystem resilience [

7].

Additionally, decreasing water levels can enhance sediment resuspension, releasing bound nutrients and contaminants, further exacerbating DO depletion [

9]. Warmer conditions may also prolong the growing season of aquatic macrophytes and accelerate internal phosphorus recycling, amplifying the risk of ecological imbalance [

5]. The increasing frequency and intensity of extreme climatic events have therefore become a focal point in limnological research.

An emerging yet underexplored dimension of this issue is the impact of climatic changes on the preservation of cultural heritage within lacustrine environments. Lakes often serve as natural repositories for archaeological remains, including waterlogged wood and other organic materials that benefit from the anoxic and water-saturated conditions typical of submerged settings [

10,

11]. However, these protective conditions are closely linked to environmental parameters—such as water chemistry, sediment composition, and vegetation cover—all of which are susceptible to climate variability [

10].

Despite the importance of these sites, relatively few studies have investigated the preservation of archaeological materials in lake ecosystems, particularly in relation to ongoing climatic changes [

12]. In volcanic lakes, for instance, the mineralogical characteristics of sediments may influence the degradation processes and long-term conservation of waterlogged wood [

13]. Critical parameters such as water temperature, DO, pH, redox potential, and turbidity—all sensitive to climate variability—can significantly affect preservation dynamics.

Direct monitoring of environmental conditions near submerged archaeological remains is essential but often hindered by logistical constraints, such as limited infrastructure and maintenance challenges in remote or underwater contexts. In this regard, terrestrial meteorological data may serve as useful proxies to infer lake dynamics, especially when correlated with aquatic parameters [

14].

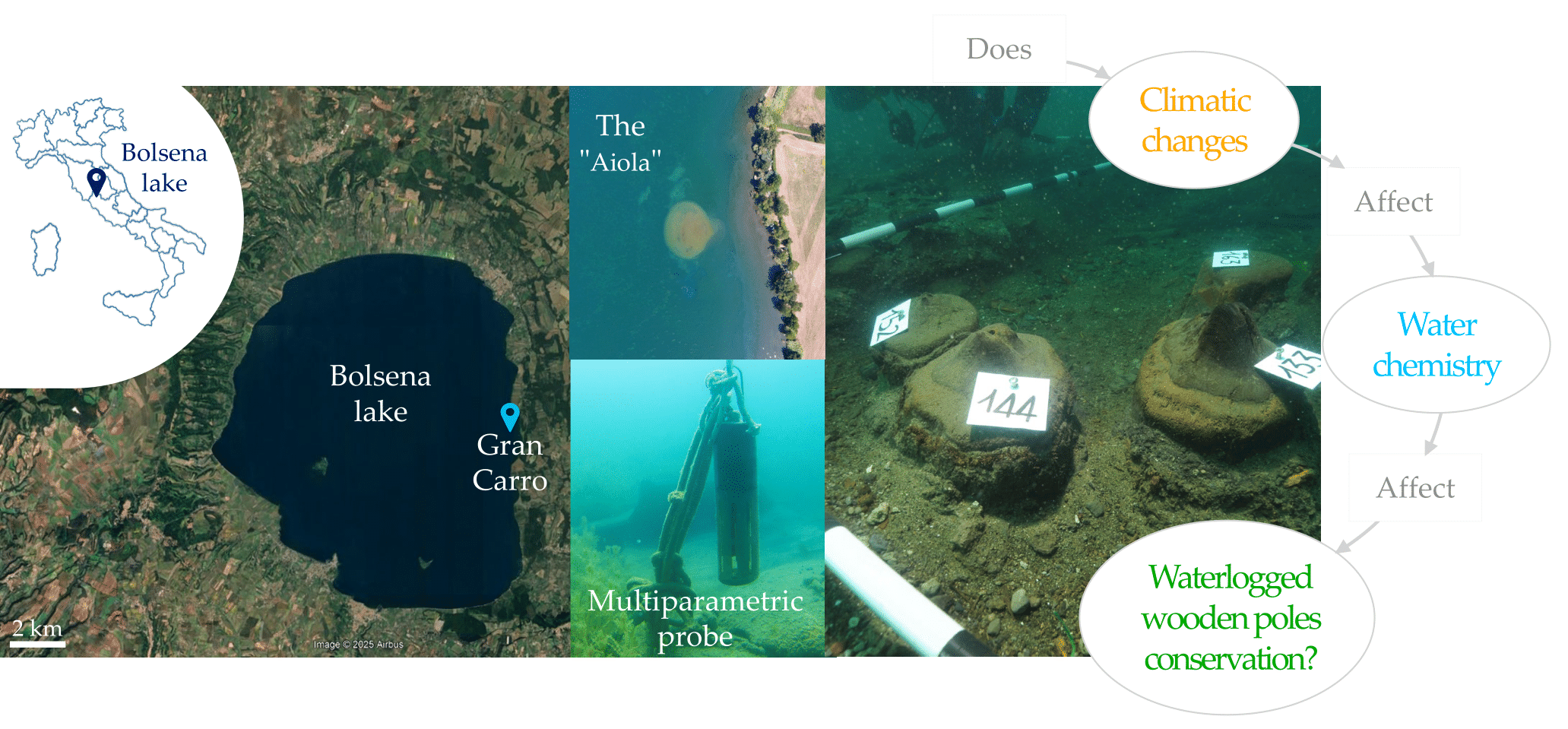

This study investigates the relationship between climatic and limnological parameters in Lake Bolsena, a volcanic lake in central Italy that hosts the submerged archaeological settlement of Gran Carro. The research integrates a 30-year climatic dataset with in situ water quality measurements collected in 2022 through a multiparameter probe installed near the archaeological site. The selected parameters include water temperature, DO, pH, redox potential, and turbidity. The year 2022, characterized by extreme drought and record-breaking heatwaves, provides a significant case study for evaluating the effects of climatic stressors on lake dynamics and the preservation of waterlogged archaeological wood. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) surveys were also employed to assess water level fluctuations and shoreline morphology.

By analysing climatic and aquatic trends, sediment characteristics, and the role of biotic agents in wood degradation, this interdisciplinary research aims to enhance our understanding of how climate change influences the conservation of submerged cultural heritage. The findings contribute to the development of more effective monitoring frameworks and preservation strategies, addressing both environmental and archaeological priorities in lake ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

Lake Bolsena is located in central Italy, in the province of Viterbo, within the Upper Lazio region. It is well known as the largest volcanic lake in Europe, with a water volume of approximately 9.2 km³. The lake occupies a caldera formed by the collapse of the magma chamber roof following the cessation of volcanic activity from the Vulsinian apparatus. Lake Bolsena serves as a vital resource for the local population, providing water for domestic use, agriculture, and supporting tourism. Approximately 22,000 people reside within its watershed, with the population increasing to around 35,000 during the summer months [

15].

The lake is subject to pollution risks, particularly from agricultural runoff containing high levels of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) from fertilisers. The first limnological studies of Lake Bolsena were conducted between 1966 and 1971 by the National Research Council [

16], and data collection has continued regularly since. In 2004, the lake’s water renewal time was estimated at approximately 120 years [

15], but more recent assessments suggest an increase to around 300 years [

17]. In addition to the lake’s intrinsic vulnerability—due to the absence of inflowing tributaries and the presence of only a single outflow—this shift is attributed to factors such as intensified agricultural practices, inadequate maintenance of sewage infrastructure, increasing urbanization, and climate-related stressors [

15,

17].

The ecological status of the lake has been monitored over several decades, with annual reports documenting progressive eutrophication, particularly in the deeper layers [

15]. From an archaeological perspective, the Gran Carro site within the lake has been extensively studied. It was discovered in 1959 by Alessandro Fioravanti [

18,

19] and dates to the beginning of the Early Iron Age (9th century BCE). The settlement is located at a depth of 4–5 meters, approximately 100 meters offshore from the lake’s eastern shore (42°35’N, 11°59’E). Wooden structural remains from the site show variable states of preservation, ranging from well-preserved to heavily degraded wood [

12]. Notably, these remains tend to accumulate heavy metals, reflecting both biotic and abiotic degradation processes [

13].

As for the climate, according to the the Köppen–Geiger climate classification [

20], Lake Bolsena falls within the Csa category, which means a Mediterranean climate with hot dry summers. However, due to its specific altitude (~350 m a.s.l.) and lake influences, local conditions are attenuated. In fact, winters are mild, typically lasting from October through May, with the mean minimum temperature of the coldest month dropping slightly below 0°C (–0.3°C). Summers are moderately warm, with mean maximum temperatures remaining below 29°C. Annual precipitation is moderately high, ranging from 954 to 1166 mm, with summer rainfall events contributing between 103 and 163 mm. Summer aridity is not particularly pronounced and is confined to July and August (

Figure S1), supporting the classification of Bolsena’s climate as mesotemperate, sub-humid to humid ombrotypes and lower supramediterranean thermotype [

21].

2.2. Materials

This study analysed climate data provided by the Civil Protection Department (PC) [

22] and the Regional Agency for the Development and Innovation in Agriculture of Lazio (ARSIAL) [

23], along with water quality data from the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection of Lazio (ARPA) [

24]. Daily maximum (Tmax) and minimum (Tmin) air temperatures, as well as daily precipitation (PRCP), were collected from 1990 to 2023, covering a 34-year period.

To better understand the lake’s water conditions, data from ARPA Lazio were examined with particular reference to water temperature (Tw), pH, dissolved oxygen concentration (DO), and electrical conductivity (EC). These parameters are widely recognised as key indicators of water quality and ecosystem health and were selected due to their relevance in detecting temporal changes. However, the ARPA dataset spans a shorter period, from 2014 to 2019, totaling six years.

To complement this information and contextualise the lake’s biogeochemical dynamics, it is important to note that the epilimnion—the upper water layer characterised by relatively uniform and warmer temperatures—extends to a depth of approximately 25 meters. The most recent full water turnover, involving mixing between the epilimnion and the colder hypolimnion, occurred in spring 2019 [

25]. Monitoring parameters such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient levels in this layer provides critical insight into the ecological status of the lake.

Since the ARPA monitoring probe is positioned on the western shore—nearly opposite the Gran Carro archaeological site—this study integrated climate data with high-resolution measurements from a multiparameter probe installed near the archaeological remains. Unlike the ARPA dataset, this probe collects hourly data on a daily basis, offering a more detailed temporal resolution. The parameters analysed include water temperature (Tw), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), oxygen saturation (Osat), redox potential (Eh), salinity (Sal), electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS).

2.3. Methods

The initial step of the analysis involved calculating average values of the climatic parameters and examining their temporal variations over the observation period. To evaluate extreme climatic conditions, the climatic dataset was further processed to derive a set of climate indices recommended by the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCCDI) of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations (UN), which are specifically designed to characterise extreme climate events [

26]. The selected indices are listed in

Table 1; in

Table S1 are reported additional climatic indices related to the supplementary materials.

Climate indices were also analysed over the same time frame as the climatic data to evaluate their variation throughout the study period.

Correlation analyses were performed using Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient [

27], a non-parametric method also referred to as a filter method. This approach identifies the most influential variables by assessing the strength and direction of the relationship between each variable and the response of interest. Correlations were examined between daily air temperature data—maximum (Tmax) and minimum (Tmin)—and various water quality parameters, including water temperature (Tw), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), oxygen saturation (Osat), redox potential (Eh), salinity (Sal), electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS), as measured by the probe (Multiparameter Probe Tripod, Aqualabo, Champigny-sur-Marne, France) near the archaeological site.

Importantly, the analysis also accounted for potential lagged effects of climatic variables on water quality. In addition to same-day correlations (Lag 0), the influence of Tmax and Tmin one (Lag 1), two (Lag 2), and three days (Lag 3) prior to water parameter measurements was evaluated to capture delayed responses in the lake system.

2.3.1. UAV Imaging Analysis

Two drones were employed to capture aerial imagery of the "Aiola" area and the lake shoreline during the year 2022: a DJI Phantom 4 RTK and a DJI Phantom 4 (Da-Jiang Innovations Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China) equipped with a Mapir Survey 3 multispectral camera (Mapir Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). UAV flights were conducted at different altitudes—100 metres for general coverage and 70 metres for higher-resolution detail.

The Phantom 4 RTK is characterised by its advanced positioning system, incorporating a Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) module that enhances spatial accuracy by correcting potential errors from the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). This RTK system allows for real-time positional data collection with a precision of up to 1 cm. At an altitude of 100 metres, the Phantom 4 RTK achieves a Ground Sampling Distance (GSD) of 2.74 cm, enabling detailed terrain representation and improved data interpretation.

The DJI Phantom 4 was also equipped with a Mapir Survey 3 multispectral camera featuring wide-angle optics and an OCN (Orange-Cyan-NIR) filter. This setup allows for the capture of imagery across multiple wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, supporting detailed analysis of terrain and vegetation. The Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (OSAVI) was applied to detect vegetation, aquatic plants, water bodies, and potential indicators of environmental disturbance or pollution.

Flights were conducted during different periods—summer 2022 and 2023—in order to compare imagery with corresponding climatic conditions and data from the multiparametric probe.

2.3.2. Sediment Analysis

For the sediment analysis, the following properties were measured: pH, redox potential (Eh), and both available and total phosphorus content. Soil pH was determined potentiometrically in a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil-to-deionised water suspension using a pH meter (Hanna Instruments Inc., Woonsocket, RI, USA), following the protocol described by Van Reeuwijk [

28]. Redox potential (Eh) was measured in a 1:5 (w/v) soil-to-deionised water suspension using a commercially available oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) combination electrode connected to a millivoltmeter (Mettler-Toledo International Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland).

The total metal content was analysed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) with an Optim 8000 DV instrument (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, CT, USA) according to the method described in Sidoti, et al. [

13]. Total phosphorus content was quantified at its specific emission wavelength of 213.617 nm.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Description of Seasonal Climate in Bolsena

Table 2 provides an overview of the climatic conditions in the Bolsena area, which can be classified as sub-Mediterranean due to a brief dry period typically occurring in July and August. During the reference period 2014–2019, the mean annual temperature was 14.8 °C, with a maximum of 40.9 °C recorded in August 2017 and a minimum of −8.3 °C in February 2018. The average total annual precipitation was 840.4 mm, ranging from a maximum of 1140.4 mm in 2014 to a minimum of 531.2 mm in 2017.

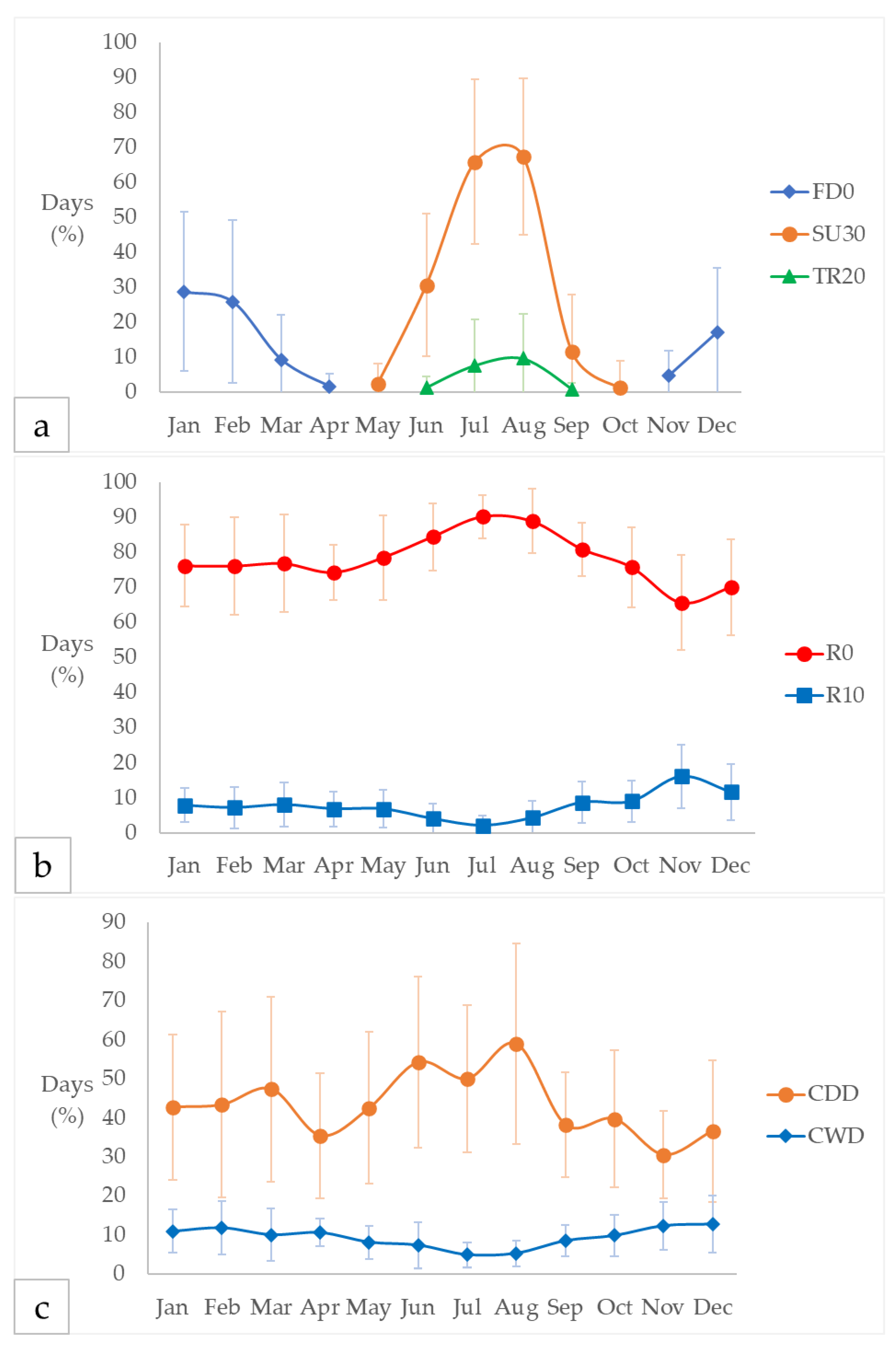

With regard to extreme climatic events, it is possible to draw insights into their seasonal distribution. Nearly 70% of days during the summer months (June to August) record maximum temperatures exceeding 30 °C (

Figure 1a). Tropical Nights are observed particularly in August, aligning with the elevated temperatures recorded during this period. Precipitation is scarce, or even absent, especially in July (

Figure 1b and S2). The number of Consecutive Dry Days (CDD) peaks during the summer, reaching a maximum in August, with 58.97% of days classified as dry (

Figure 1c). In contrast, extreme rainfall events are more frequent between September and November and again from March to April, with notable concentrations in November (

Figure S2). It is important to note that the wide error bars in

Figure 1 reflect substantial interannual variability in the data from 1990 to 2022.

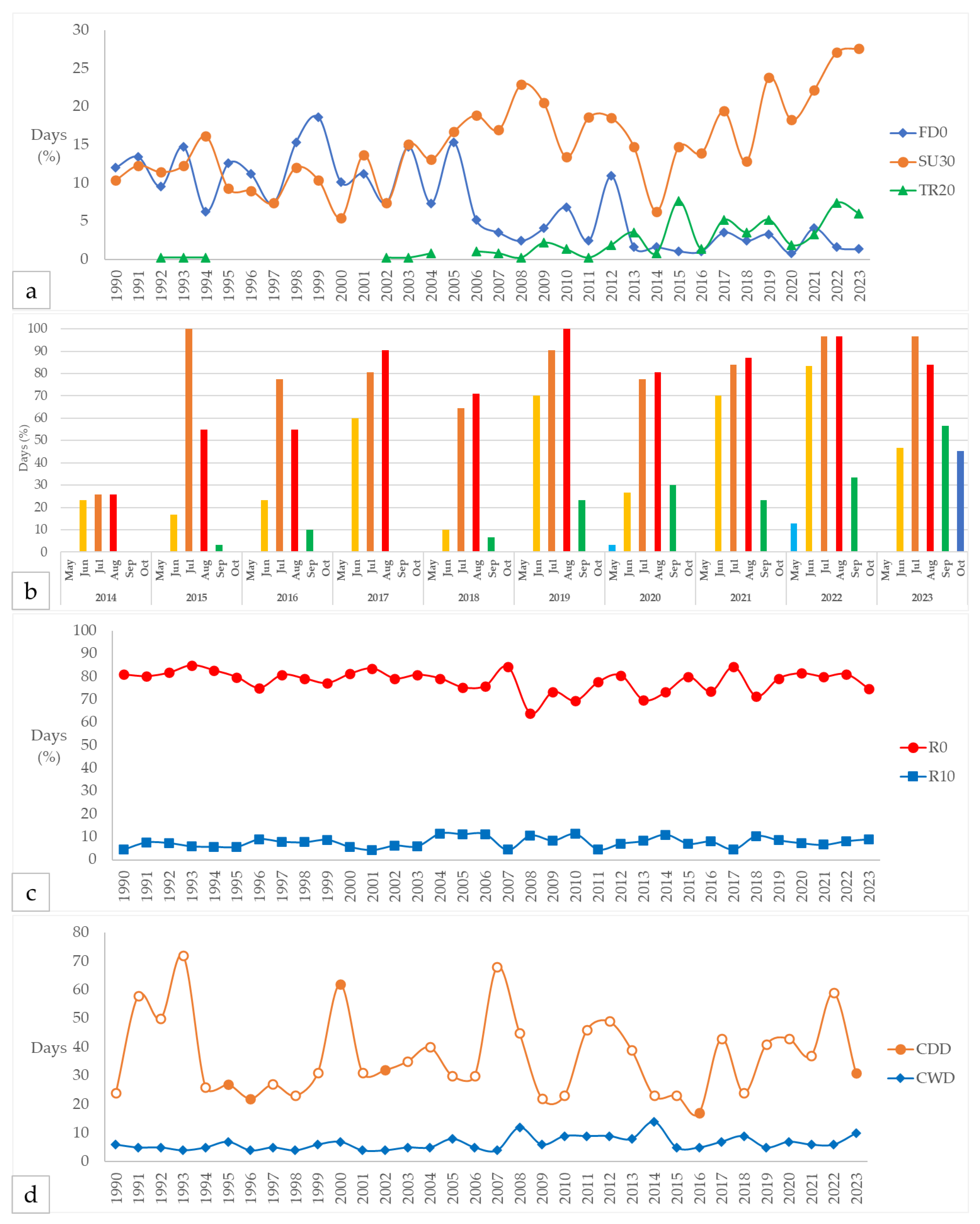

3.2. Temporal Analysis of Bolsena Climate

The time series reveals a clear increase in the total annual number of hot days over the study period. The lowest values were recorded in 2000 (5.5%) and again in 2014 (6.3%). A marked rise in the SU30 is observed after 2014, with peak values reached in 2022 (27.1%) and 2023 (27.7%). In fact, the 2023 data suggest that maximum temperatures exceeded 30 °C for nearly three months (

Figure 2a). These results indicate a clear upward trend in the frequency of hot days, with SU30 values reaching their highest levels in recent years, particularly in 2022 and 2023. The SU30 pattern closely mirrors that of Tropical Nights (TR20). Notably, in 2022, the highest percentage of hot days coincided with the peak occurrence of tropical nights (6%). Tropical nights were absent before 1992 and remained infrequent until 2008. The highest recorded values occurred in 2015 (7.7%) and again in 2022.

In contrast, the number of frost days shows a declining trend (

Figure 2a). From 2013 to 2023, frost days consistently remained below 5%, equating to fewer than 20 frost days per year. In 1999, there were 68 frost days (18.6%), whereas in 2023, only five (1.4%). Frost days are closely linked to winter lake turnover, which typically occurs in January–February [

15,

29], and their reduction is likely attributable to changing climatic conditions that influence this process.

The SU30 curve in

Figure 2a indicates not only increased temperature intensity but also an extension of the hot season. After 2015, hot days began to occur in September; after 2020, they were also recorded in May. By 2023, the hot season appears to extend into October.

Figure 2b further illustrates the intensification of temperature extremes, reflected in the rising SU30 values, suggesting both more frequent and more intense hot days. This shift may have implications for various ecological and climatic processes in the region.

Despite the broader trend of increasing storm and flood events globally, the study area has not experienced significant extreme events of this type to date [

26]. Both the R0 and R10 remain relatively stable, showing no clear increasing or decreasing trend. This suggests that, up to the present, the area has not undergone significant changes in total or extreme rainfall patterns (

Figure 2c).

CDD are commonly observed during the summer months, as indicated by open circles in

Figure 2d. In some years, CDD also occur during the winter season, represented by filled circles (

Figure 2d). A high number of CDD during summer is of particular concern due to elevated temperatures, which pose greater stress on ecosystems and living organisms. Moreover, CDD index has slightly increased since 2014 (

Figure S3), contributing to an extension of the hot season, as previously observed for SU30. This stress is further exacerbated by increased evapotranspiration, particularly when prolonged dry periods coincide with tropical nights [

5].

In contrast, CWD have remained relatively stable at around seven consecutive days over the past three years. However, there is an indication of an increase in 2023, with up to ten consecutive wet days recorded.

The observed variability in both CDD and CWD may have significant implications for local ecosystems, particularly in terms of thermal stress and water availability, which are critical factors for ecosystem resilience and the survival of aquatic and terrestrial organisms.

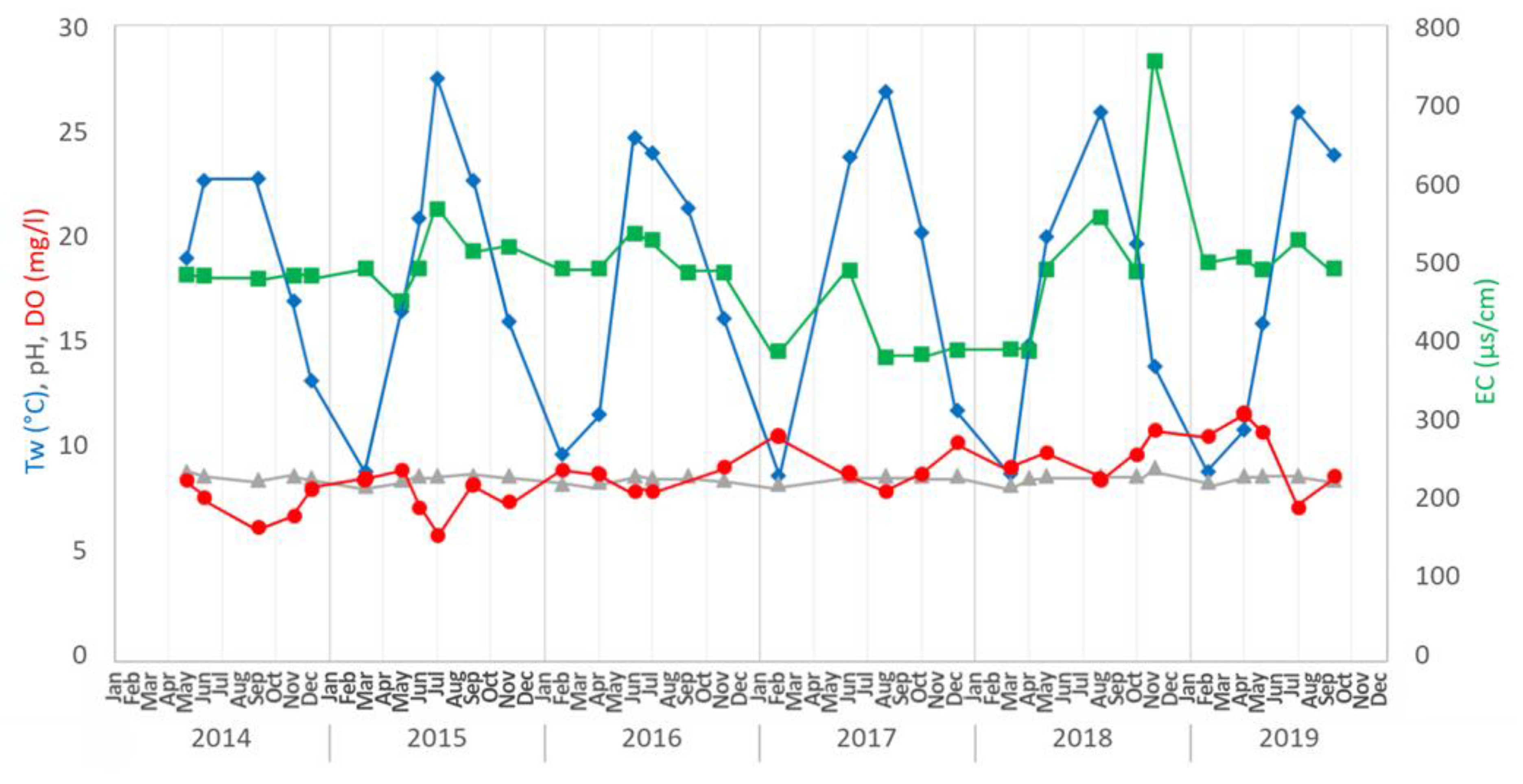

3.3. Water Data Analysis

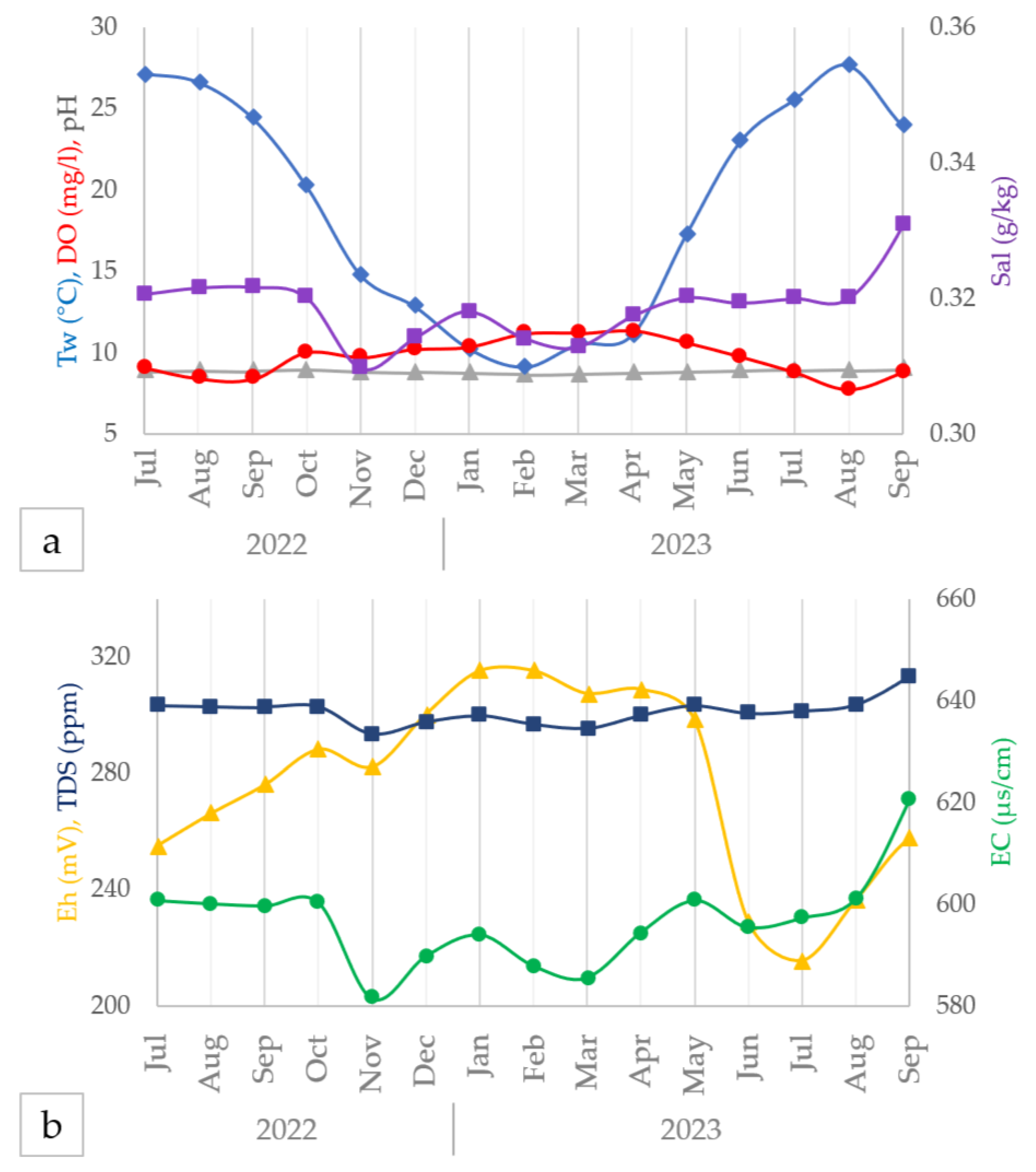

Lake Bolsena is classified as a monomictic lake [

15], meaning it undergoes a single mixing event of the water column annually. This overturn typically occurs in January or February, during which vertical mixing reaches its greatest depth, usually between late winter and early spring (

Figure 3). Thermal stratification begins in April and persists until December [

25]. The highest epilimnetic temperatures are recorded in July and August, ranging between 24 and 26 °C. The warmest surface water conditions occur in August, when average temperatures reach approximately 26.5 °C.

Throughout the year, the pH of the epilimnion remains consistently alkaline, never falling below 8—even during the mixing period in early February, which is typically associated with changes in water chemistry. This persistent alkalinity contrasts with other systems where elevated pH has been attributed to high bicarbonate concentrations [

30]; however, bicarbonates were not detected in the water column or sediments of Lake Bolsena. The pH remains high—up to 8.8—until December. Notably, Mosello, et al. [

15] reported a surface pH of 7.6 in December, indicating interannual variability.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations show distinct seasonal variation. The lowest DO values, around 6 mg/L, are observed during the summer stratification period (

Figure 3), coinciding with thermal stability and limited vertical mixing. From October to May, DO concentrations are consistently above 9 mg/L, reflecting good oxygenation throughout the water column. According to Björdal and Elam [

31] and Salmaso, et al. [

29] values above 6 mg/L are considered sufficient to support aquatic life, including fish species. These findings suggest that Lake Bolsena maintains generally favorable oxygen conditions during the mixing period, while experiencing oxygen depletion during periods of strong stratification in summer.

3.4. Water Analysis Close to Archaeological Settlement

The multiparameter probe installed in July 2022 at a depth of 4 metres recorded slightly different conditions compared to the corresponding surface water values measured by the ARPA monitoring unit located on the opposite side of the lake (

Figure 4). The analysis of these differences provides insights into the vertical stratification of water properties in proximity to the archaeological settlement.

Figure 4b shows a high redox potential (Eh), which is typical of lentic environments such as lakes [

32]. Since the probe is positioned within the epilimnion at 4 m depth, Eh values remain consistently positive. This indicates an oxidizing environment, as oxygen concentrations in the epilimnion are generally higher than in deeper water layers [

33].

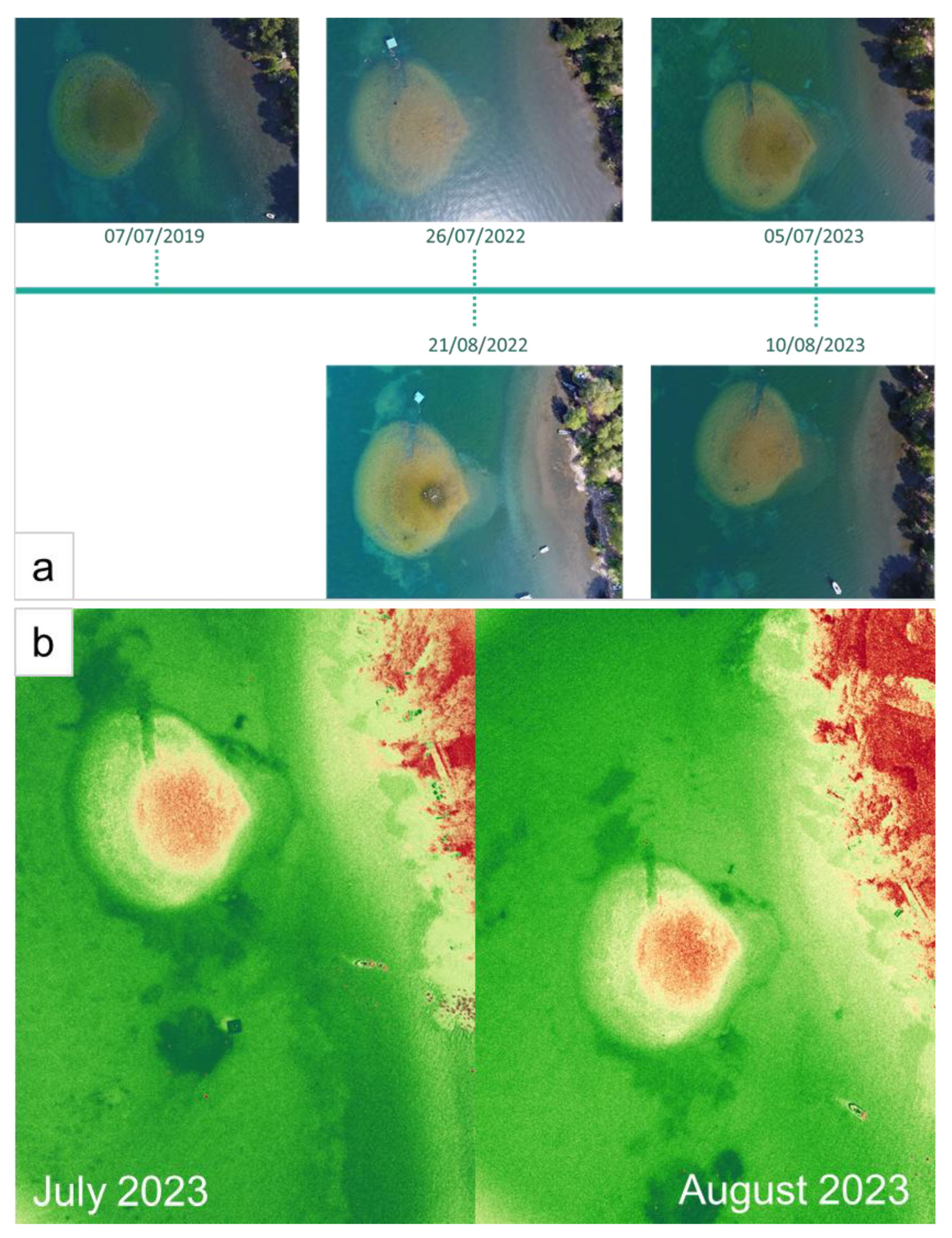

The year 2022 has been reported as exceptional from a climatic perspective [

34]. In that year, Lake Bolsena registered a water level of only 35 cm above the silt layer, compared to the expected minimum of 70 cm required during the same period to prevent water stagnation [

35]. The combined effects of extreme heat and prolonged drought are clearly evident in aerial imagery of the Aiola structure, captured by an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Previously interpreted as a ritual platform, Aiola is now hypothesized to be closely associated with nearby hot spring activity.

UAV imagery (

Figure 5a) reveals that Aiola was significantly more exposed in July 2023 than in July 2019. An even greater portion of its upper surface emerged by late July 2022 and early August 2023. On 21 August 2022, a substantial part of Aiola’s summit was clearly above water level (the black coloration of the surface corresponds to the stones composing the uppermost layer). Due to strong evapotranspiration, the shoreline appears noticeably closer, indicating substantial water retreat.

Between July 2022 and September 2023, pH values near the archaeological site remained alkaline (

Figure 4), with an average above 8 and peak values exceeding 9.10 during the summer, extending through to October 2022. This persistent alkalinity is attributed to elevated water hardness, which was measured at 36.7 °F. In 2002, Mosello, et al. [

15] reported a mean electrical conductivity (EC) of 400 μS/cm in Lake Bolsena; however, our measurements from 2022 and early 2023 recorded values exceeding 600 μS/cm in the area adjacent to the archaeological settlement (

Figure 4), indicating a higher concentration of dissolved ions, likely influenced by localized hydrothermal inputs.

Water temperatures were anomalously high, reaching 26 °C in July. Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels remained above 6 mg/L, indicating satisfactory oxygenation conditions. The winter overturn was evident between January and March 2023, as demonstrated by the combination of high DO levels and low water temperatures (

Figure 4).

Figure 5b allows for the identification of various elements within the water using multispectral imagery. Dark green areas correspond to travertine deposits, while light green tones indicate the presence of algae. The shoreline appears yellow due to a reduced algal presence. On the top of the Aiola structure, algae are absent because the water is too shallow; as a result, this area appears red in the OSAVI index rendering. In both images of

Figure 5b, the upper left corner appears red despite being covered by trees, which should normally appear green. This discrepancy is due to water coverage affecting the reflectance signal and, consequently, the index. However, since the primary aim of this analysis is focused on aquatic features, this issue can be corrected by applying a reclassification of the spectral data.

Currently, no significant differences are observed between July and August 2023; therefore, ongoing monitoring and comparison with future datasets will be necessary to detect meaningful trends.

The extreme heat events of 2022 likely induced a strong thermal stratification and enhanced water column stability. Increased light availability and phosphorus release from sediments may have favoured the proliferation of cyanobacterial blooms [

36]. Notably, elevated pH levels during this period may facilitate the mineralization of organic phosphorus. At high pH, hydroxyl ions can displace organic or metal-organic phosphate complexes, promoting phosphorus bioavailability [

36]. While these pH changes may not directly harm aquatic organisms, they significantly affect the solubility and availability of key nutrients, potentially exacerbating eutrophication. For instance, increased phosphorus solubility may stimulate excessive algal growth, thereby raising long-term oxygen demand in the system [

37].

Moreover, the heat stress conditions of 2022 resulted in higher evapotranspiration rates. This effect may have been intensified by continuous water withdrawals to support agriculture and domestic needs in the region. Di Matteo, et al. [

38] previously linked water level decline in Lake Bolsena (between the 1980s and mid-1990s) primarily to reduced precipitation. However, our findings suggest that increased temperatures and associated climatic indices now play a more prominent role, as precipitation levels do not exhibit a significant long-term decline. The drought during summer 2022, in particular, was marked by an uninterrupted dry period of 59 days between May and July, reinforcing the importance of temperature-driven processes in lake level reduction.

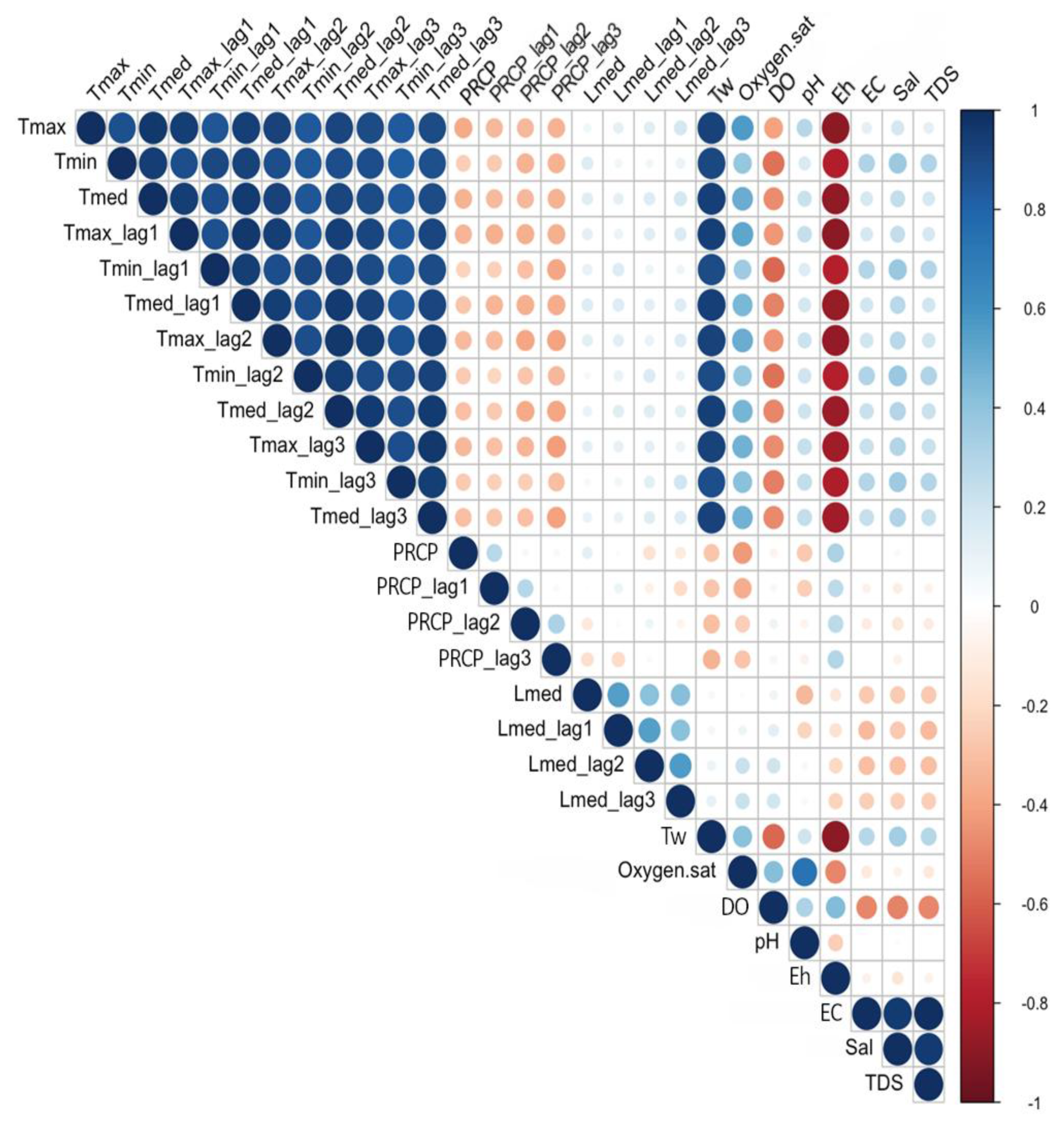

3.5. Correlation Between Climatic and Water Properties

As expected, the increase in air temperatures is positively correlated with the rise in water temperatures. This effect persists for up to two days after the initial air temperature measurement (day t), indicating a thermal inertia of the water body. Both atmospheric and water temperatures exert a negative influence on dissolved oxygen availability. Notably, minimum air temperatures appear to play a relevant role, potentially linked to climatic stress associated with the Tropical Nights Index. Elevated nighttime temperatures intensify lake water stratification, further restricting oxygen circulation.

Indeed, increasing thermal stress is associated with a decline in dissolved oxygen (DO) levels and, more prominently, with a reduction in redox potential (Eh). Redox potential is a measure of the system’s capacity to engage in oxidation-reduction reactions. Under extreme conditions, diminished oxygen availability and lower redox values may lead to hypoxia, with detrimental effects on aquatic organisms. During anaerobic phases, stable thermal stratification can inhibit vertical mixing, thereby reducing oxygen penetration into deeper water layers.

The relationship between redox potential, electrical conductivity, and turbidity is complex and context-dependent, governed by the chemical and physical properties of the aquatic system. In general, a positive correlation is observed between redox potential and conductivity (

Figure 6). Oxidizing conditions (high Eh) promote the dissolution of specific ionic species—such as sulphates, nitrates, and metal ions (e.g., Fe³⁺, Mn²⁺)—thereby enhancing conductivity. Conversely, under reducing conditions (low Eh), processes such as sulphate reduction to sulphide increase ionic concentrations and alter conductivity.

In Lake Bolsena, sulphide species are believed to play a key role in arsenic immobilisation through the precipitation of arsenic into insoluble forms [

13]. Furthermore, redox dynamics indirectly influence turbidity by affecting the precipitation of compounds. For instance, oxidation of ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) to ferric iron (Fe³⁺) can lead to the formation of insoluble ferric hydroxides, contributing to increased turbidity. Similar mechanisms may occur for other metals and organic matter.

Changes in redox conditions also regulate microbial community composition, as different taxa dominate under specific redox environments. These microbial processes modulate biogeochemical cycling and can generate organic matter and particulates, further influencing turbidity. Dissolved oxygen is moderately correlated with redox potential—higher DO levels generally support more oxidising conditions. Additionally, DO is negatively correlated with conductivity, salinity, and total dissolved solids (TDS), all of which show strong mutual positive autocorrelation, as expected given the interdependence of these parameters (e.g., conductivity being derived from TDS and salinity).

It is crucial to note that the ecological consequences of redox potential variations depend on both their magnitude and persistence, as well as the limnological characteristics of the lake and its watershed. Prolonged periods of elevated temperature, especially in summer, should be considered a major environmental stressor. Numerous studies have demonstrated that increases in air temperature can significantly alter lake circulation dynamics due to differential warming of surface and deep layers [

39,

40].

As observed in Lake Bolsena, these effects may be amplified in lakes with limited hydrological inflows and long water residence times. Therefore, in assessing lake trophic evolution, it is necessary to consider not only catchment-derived nutrient loads but also broader climatic drivers. A long-term trend has already been identified in Bolsena, where alternating drought and flood periods since the early 1990s have disrupted the lake’s hydrological regime, leading to reduced inflows [

41]. Monitoring redox potential fluctuations is thus essential for evaluating water quality, managing aquatic ecosystems, and anticipating the ecological consequences of climate change.

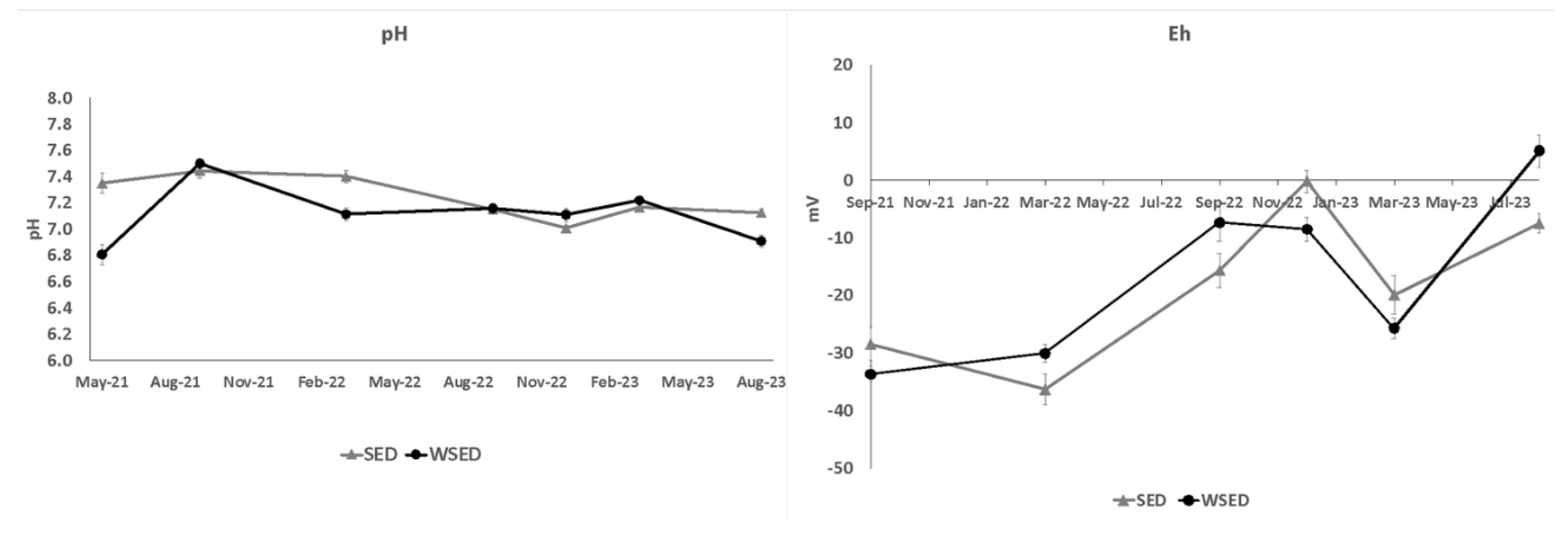

3.6. Sediment

Sediment quality plays a critical role in the conservation of cultural heritage, as the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of sediments—particularly in conjunction with the surrounding water—can significantly influence the preservation of archaeological materials [

42,

43]. Sediments surrounding waterlogged archaeological wood (WAW) often exhibit distinct features in terms of decay evidence, microbial activity and diversity, and chemical composition when compared to sediments unaffected by the presence of WAW. Moreover, sediment properties may undergo alterations due to both natural factors (e.g., climate change) and anthropogenic influences (e.g., overtourism, pollution), which can ultimately impact the rate of WAW degradation.

From 2021 to 2023, sediment characteristics were analysed at the Gran Carro archaeological site. The sediments hosting the settlement are predominantly sandy to loamy-sand in texture and exhibited significantly higher organic carbon content in areas in direct contact with WAW (referred to as Wsed), compared to sediments outside this zone (Sed) [

13]. Among the key chemical parameters influencing the biological degradation of wood, pH and redox potential (Eh) are particularly relevant. At Gran Carro, sediment pH was classified as neutral to slightly alkaline (according to USDA standards) (

Figure 7), while redox conditions were generally suboxic to anoxic (

Figure 7).

Natural fluctuations in these parameters were observed over the three-year monitoring period, likely reflecting seasonal dynamics, varying climatic conditions, and human pressures. Nonetheless, these redox and pH conditions did not inhibit microbial activity. Evidence of consistent nitrification suggests that oxidative microbial processes were ongoing [

44]. Notably, a slight but significant acidification and increase in Eh were recorded in Winter 2022 and Summer 2023 in Wsed, possibly reflecting enhanced microbial decomposition near the WAW interface.

Total phosphorus (TP) content in sediments serves as a useful indicator of lake eutrophication. At Gran Carro, sediment TP concentrations ranged from 422 to 545 mg kg⁻¹ [

44], corresponding to nominal to moderate pollution levels based on the United States Environmental Protection Agency [

45] classification (nominal pollution <450 ppm; moderate pollution >450 ppm). Water column phosphorus levels were consistent with values reported by Mosello, et al. [

17], who observed an increase from 9 to 16 ppb between 2004 and 2017. These authors concluded that Lake Bolsena had transitioned from oligotrophic to mesotrophic status due to increased external nutrient input.

Furthermore, phosphorus loading in the water may be amplified by reduced redox potential associated with thermal stratification driven by rising temperatures. The reductive dissolution of iron and manganese compounds under low Eh conditions can lead to the release of phosphorus previously bound to these minerals, thus increasing its availability in the water column.

3.7. Possible Scenario for Wood Degradation in Waterlogged Lake Conditions

Waterlogged wood is subject to degradation by wood-decaying fungi and bacteria, primarily classified as erosion and tunnelling bacteria [

31]. Soft rot fungi, while tolerant of low oxygen concentrations, still require oxygen to be metabolically active. These fungi can survive across a wide pH range (3–9), with optimal activity between pH 6 and 8; fungal growth is significantly restricted only under highly alkaline conditions (pH 9) [

46]. This implies that in the presence of oxygen, fungal degradation of wood remains possible even when pH conditions are suboptimal.

Among bacterial agents, tunnelling bacteria are typically found in wood samples not buried at significant depths, whereas erosion bacteria are more tolerant to oxygen-deprived (anaerobic) environments. Erosion bacteria are particularly effective at degrading wood in the presence of toxic heartwood extractives, which often inhibit fungal colonisation. Microbial activity under anoxic conditions promotes the accumulation of sulphur compounds and contributes to environmental acidification [

13,

47]. Similar considerations apply to ammonium accumulation. Thus, understanding bacterial activity in relation to redox potential, conductivity, and pH is essential for evaluating the preservation potential of archaeological wood [

31].

Redox potential values between +100 and +400 mV are generally considered conducive to wood preservation [

14]. However, no direct correlation has yet been established between redox potential and actual rates of wood degradation. Therefore, the interpretation of redox, conductivity, and dissolved oxygen values in the context of active decay remains uncertain. Under low redox (reducing) conditions, organic matter decomposition by anaerobic microorganisms can lead to oxygen depletion, which could influence the balance between preservation and degradation.

Each lake habitat possesses intrinsic environmental characteristics that shape distinct bacterial communities [

48], leading to specific microbial biogeographies within lake systems [

49]. Under projected climate warming scenarios, elevated temperatures are expected to influence bacterial communities, potentially selecting for species that pose a greater threat to wood preservation. Nevertheless, the impact of temperature depends on depth and the nature of the surrounding sedimentary environment.

Experimental attempts to assess the influence of environmental parameters on wood-degrading bacterial activity have yielded inconsistent results. While higher temperatures are known to accelerate the activity of erosion bacteria in laboratory conditions—where they are often used to stimulate decay [

50]—there is no conclusive evidence that long-term elevated temperatures promote decay in natural setting [

31]. This is likely due to the interplay of multiple environmental factors, including soil composition, redox potential, and oxygen demand. Previous microcosm studies have shown that increased nitrogen concentrations do not necessarily enhance erosion bacterial activity [

43]. Similarly, ammonium concentrations alone may not be predictive of bacterial degradation potential without consideration of redox, conductivity, and pH [

31].

In the case of Lake Bolsena, sediment analysis revealed heightened biological activity near wooden archaeological remains, consistent with bacterial (particularly erosion bacterial) activity under anoxic conditions. If a general lowering of lake level is assumed—as may result from enhanced evapotranspiration—greater oxygen penetration could occur, accelerating wood degradation. Under such conditions, soft rot fungi, which degrade wood more rapidly than bacteria, may become dominant agents of deterioration.

4. Conclusions

Identifying reliable climatic proxies to characterize the dynamics of lacustrine ecosystems remains a significant challenge, particularly in large and heterogeneous basins such as Lake Bolsena. The spatial variability of environmental conditions, influenced by climate, anthropogenic pressures, and water abstraction, complicates the extrapolation of results across the entire catchment. For this reason, in assessing the conservation risks to submerged archaeological wood, a site-specific approach focusing on water and sediment parameters in direct proximity to the archaeological remains was adopted.

The observed increase in air and water temperatures, along with the greater frequency of extreme events—such as tropical nights and heatwaves—has led to altered redox conditions, reduced dissolved oxygen, and intensified chemical and biological processes within the lake system. These changes support the activity of anaerobic wood-degrading agents, such as erosion bacteria, whose presence was confirmed in the sediments surrounding archaeological wooden poles. Furthermore, rising evapotranspiration may cause water level drops, potentially exposing submerged remains to increased oxygen availability and accelerating degradation by aerobic fungi and bacteria.

Although a watershed management plan is currently in place to maintain seasonal lake level stability, its effectiveness may be limited under future climate scenarios characterized by more frequent extremes. Therefore, integrated management strategies that consider both catchment-scale climate drivers and localized preservation conditions are essential to ensure the long-term conservation of submerged archaeological heritage.

The Gran Carro site, with its unique assemblage of waterlogged wooden structures, represents a cultural and historical legacy of exceptional importance. Preserving this underwater heritage is not only a scientific and conservation challenge but also a responsibility toward safeguarding the archaeological identity of the region for future generations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org. Table S1: Additional analysed climatic indices of the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCDDI) reported in the supplementary materials. Table S2: Monthly mean of water temperature (Tw), dissolved oxygen (DO), pH and electrical conductivity (EC) in the years 2014-2018, data from regional agency of environmental protection of Lazio (ARPA). All parameters are referred to the epilimnion zone. Figure S1: Walter-Lieth diagram of temperature and precipitation in Bolsena in the period 1990-2022. Figure S2: Monthly percentage of rainy days (R0, R1, R10, R20, and R50) for the period 1990–2022 (data from ARSIAL and PC). The highest concentration of rainy days occurs in November, with most events falling into the R1 or R10 categories. Figure S3: Percentage of consecutive dry days per month (May-October), showing a slight increase from 2014 to 2022.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MR; Data curation: ST; Formal analysis: ST, FC, ES; Funding acquisition: MR; Investigation: BB, ES, MC, ST, MCM, GG; Methodology: MR, ST, MC, FA; Project administration: MR; Resources: MR, MCM, BB; Supervision: MR; GG; Validation: MR, ST; Writing - original draft: ST, MR; Writing - review & editing: ST, MR, MCM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the JPICH-19 project funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research: “Archaeological Wooden Pile-Dwellings in Mediterranean European Lakes: Strategies for Their Exploitation, Monitoring, and Conservation (WOODPDLAKE)”.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the entire team of CRAS-APS (Centro Ricerche per l'Archeologia Subacquea) for their technical assistance in probe management and UAV analysis. Special thanks are also extended to Salvatore Grimaldi for his valuable support and supervision in the analysis of climatic data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gosling, S. N.; Arnell, N. W., A global assessment of the impact of climate change on water scarcity. Climatic Change 2016, 134 (3), 371-385. [CrossRef]

- Adrian, R.; O'Reilly, C. M.; Zagarese, H.; Baines, S. B.; Hessen, D. O.; Keller, W.; Livingstone, D. M.; Sommaruga, R.; Straile, D.; Van Donk, E.; Weyhenmeyer, G. A.; Winder, M., Lakes as sentinels of climate change. Limnology and Oceanography 2009, 54 (6part2), 2283-2297.

- Pi, X.; Luo, Q.; Feng, L.; Xu, Y.; Tang, J.; Liang, X.; Ma, E.; Cheng, R.; Fensholt, R.; Brandt, M.; Cai, X.; Gibson, L.; Liu, J.; Zheng, C.; Li, W.; Bryan, B. A., Mapping global lake dynamics reveals the emerging roles of small lakes. Nature Communications 2022, 13 (1), 5777. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Her, Y.; Muñoz-Carpena, R.; Yu, X.; Martinez, C.; Singh, A., Climate change impacts on water quantity and quality of a watershed-lake system using a spatially integrated modeling framework in the Kissimmee River – Lake Okeechobee system. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2023, 47, 101408. [CrossRef]

- North American Lake Management Society Climate change impacts on lakes. https://www.nalms.org/nalms-position-papers/climate-change-impacts-on-lakes/.

- Botrel, M.; Maranger, R., Global historical trends and drivers of submerged aquatic vegetation quantities in lakes. Global Change Biology 2023, 29 (9), 2493-2509. [CrossRef]

- Rogora, M.; Frate, L.; Carranza, M. L.; Freppaz, M.; Stanisci, A.; Bertani, I.; Bottarin, R.; Brambilla, A.; Canullo, R.; Carbognani, M.; Cerrato, C.; Chelli, S.; Cremonese, E.; Cutini, M.; Di Musciano, M.; Erschbamer, B.; Godone, D.; Iocchi, M.; Isabellon, M.; Magnani, A.; Mazzola, L.; Morra di Cella, U.; Pauli, H.; Petey, M.; Petriccione, B.; Porro, F.; Psenner, R.; Rossetti, G.; Scotti, A.; Sommaruga, R.; Tappeiner, U.; Theurillat, J. P.; Tomaselli, M.; Viglietti, D.; Viterbi, R.; Vittoz, P.; Winkler, M.; Matteucci, G., Assessment of climate change effects on mountain ecosystems through a cross-site analysis in the Alps and Apennines. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 624, 1429-1442. [CrossRef]

- Vad, C. F.; Hanny-Endrédi, A.; Kratina, P.; Abonyi, A.; Mironova, E.; Murray, D. S.; Samchyshyna, L.; Tsakalakis, I.; Smeti, E.; Spatharis, S.; Tan, H.; Preiler, C.; Petrusek, A.; Bengtsson, M. M.; Ptacnik, R., Spatial insurance against a heatwave differs between trophic levels in experimental aquatic communities. Global Change Biology 2023, 29 (11), 3054-3071. [CrossRef]

- Matthiesen, H.; Hollesen, J.; Dunlop, R.; Seither, A.; de Beer, J., In situ Measurements of Oxygen Dynamics in Unsaturated Archaeological Deposits. Archaeometry 2015, 57 (6), 1078-1094. [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, R.; van ’t Oor, M.; Kloppenburg, A.; Huisman, H., Rate of occurrence of wood degradation in foundations and archaeological sites when groundwater levels are too low. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2023, 63, 23-31.

- Matthiesen, H.; Brunning, R.; Carmichael, B.; Hollesen, J., Wetland archaeology and the impact of climate change. Antiquity 2022, 96 (390), 1412-1426. [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, M.; Galotta, G.; Antonelli, F.; Sidoti, G.; Humar, M.; Kržišnik, D.; Čufar, K.; Davidde Petriaggi, B., Micro-morphological, physical and thermogravimetric analyses of waterlogged archaeological wood from the prehistoric village of Gran Carro (Lake Bolsena-Italy). Journal of Cultural Heritage 2018, 33, 30-38. [CrossRef]

- Sidoti, G.; Antonelli, F.; Galotta, G.; Moscatelli, C.; Kržišnik, D.; Vinciguerra, V.; Tamantini, S.; Marabottini, R.; Macro, N.; Romagnoli, M., Mineral compounds in oak waterlogged archaeological wood and volcanic lake compartments. EGUsphere 2023, 2023, 1-13.

- Williams, J., Thirty Years of Monitoring in England — What Have We Learnt? Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 2012, 14 (1-4), 442-457.

- Mosello, R.; Arisci, S.; Bruni, P., Lake Bolsena (Central Italy): An updating study on its water chemistry. J. Limnol 2004, 63, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Carollo, A.; Barbanti, L.; Gerletti, M.; Ferrari, I.; Nocentini, A. M.; Bonomi, G.; Ruggiu, D.; Tonolli, L. Indagini limnologiche sui laghi di Bolsena, Bracciano, Vico e Trasimeno; Istituto di Ricerca sulle Acque (IRSA), Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR): Verbania Pallanza, Italy, 1974; p 179.

- Mosello, R.; Bruni, P.; Rogora, M.; Tartari, G.; Dresti, C., Long-term change in the trophic status and mixing regime of a deep volcanic lake (Lake Bolsena, Central Italy). Limnologica 2018, 72, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, B.; Severi, E. L'abitato sommerso della prima età del Ferro del Gran Carro di Bolsena: verso una nuova prospettiva Analysis Archaeologica [Online], 2018, p. 25-51. http://digital.casalini.it/9788854911420.

- Persiani, C., Il lago di Bolsena nella Preistoria. In Sul filo della corrente - La navigazione nelle acque interne in Italia centrale, dalla preistoria all'età moderna, Petitti, P., Ed. Società Cooperativa ARX: Montefiascone (VT), Italy, 2009; pp 39-82.

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F., World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 259-263. [CrossRef]

- Blasi, C., Fitoclimatologia del Lazio. Università La Sapienza; Regione Lazio: Rome, Italy, 1994.

- Civil Protection Department, Hydrometeorological network. Regione Lazio: Rome (Italy), 2023.

- ARSIAL, Agrometeorological network. Regione Lazio: Rome (Italy), 2023.

- ARPA Lazio, Sistema informativo regionale ambientale del Lazio. Regione Lazio: Rome (Italy), 2023.

- Bruni, P. Stato ecologico del Lago di Bolsena 2022; Bolsena (Italy), 2022.

- Nanni, G.; Minutolo, A. Report Città-Clima 2023 - Speciale Alluvioni; Legambiente: Rome (Italy), 2023.

- Kendall, M. G., A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30 (1-2), 81-93.

- Van Reeuwijk, L. P. Procedures for Soil Analysis (6ª ed., Technical Paper No. 9); International Soil Reference and Information Centre (ISRIC): Wageningen, Netherlands, 2002.

- Salmaso, N.; Mosello, R.; Garibaldi, L.; Decet, F.; Maria, C.; Brizzio; Cordella, P., Vertical mixing as a determinant of trophic status in deep lakes: A case study from two lakes south of the Alps (Lake Garda and Lake Iseo). Education J. Limnol 2002, 62, 33-41. [CrossRef]

- Huisman, D. J.; Kretschmar, E. I.; Lamersdorf, N., Characterising physicochemical sediment conditions at selected bacterial decayed wooden pile foundation sites in the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2008, 61 (1), 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Björdal, C. G.; Elam, J., Bacterial degradation of nine wooden foundation piles from Gothenburg historic city center and correlation to wood quality, environment, and time in service. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2021, 164, 105288. [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, M., Redox Potential. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters, Likens, G. E., Ed. Academic Press: Oxford, 2009; pp 852-859.

- Manahan, S. E., Environmental chemistry. 7th ed. ed.; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, 2000.

- Wang, W.; Shi, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Woolway, R. I., The impact of extreme heat on lake warming in China. Nature Communications 2024, 15 (1), 70. [CrossRef]

- Bruni, P. Il livello del lago di Bolsena; 2022.

- Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Qian, H.; Yang, H.; Niu, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhu, G.; Woolway, R. I.; Jeppesen, E., The unprecedented 2022 extreme summer heatwaves increased harmful cyanobacteria blooms. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 896, 165312. [CrossRef]

- Munson, B. H.; Axler, R.; Hagley, C.; Host, G.; Merrick, G.; Richards, C. pH. https://waterontheweb.org/under/waterquality/ph.html.

- Di Matteo, L.; Dragoni, W.; Giontella, C.; Melillo, M. In Impact of climatic change on the management of complex systems: the case of the Bolsena Lake and its aquifer, Central Italy, 33 rd International Geological Congress - Hydrogeology, Olso (Norway), Aug. 6-14, 2008; Paliwal, B. S., Ed. Scientific publisher, Jodhpur (India): Olso (Norway), 2008.

- Livingstone, D. M., A Change of Climate Provokes a Change of Paradigm: Taking Leave of Two Tacit Assumptions about Physical Lake Forcing. International Review of Hydrobiology 2008, 93 (4-5), 404-414. [CrossRef]

- Straile, D.; Livingstone, D. M.; Weyhenmeyer, G. A.; George, D. G., The Response of Freshwater Ecosystems to Climate Variability Associated with the North Atlantic Oscillation. In The North Atlantic Oscillation: Climatic Significance and Environmental Impact, 2003; pp 263-279.

- Di Francesco, S.; Biscarini, C.; Montesarchio, V.; Manciola, P., On the role of hydrological processes on the water balance of Lake Bolsena, Italy. Lakes & Reservoirs: Science, Policy and Management for Sustainable Use 2016, 21 (1), 45-55. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, B. A., Site characteristics impacting the survival of historic waterlogged wood: A review. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2001, 47 (1), 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Kretschmar, E. I.; Keijer, H.; Nelemans, P.; Lamersdorf, N., Investigating physicochemical sediment conditions at decayed wooden pile foundation sites in Amsterdam. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2008, 61 (1), 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M. C.; Marabottini, R.; Tamantini, S.; Di Buduo, G. M.; Galotta, G.; Antonelli, F.; Romagnoli, M., Sediments surrounding waterlogged archaeological wood: could arsenic be involved in preserving wooden pile dwelling from microbial decay? The Gran Carro case study (Lake Bolsena, central Italy). Journal of Cultural Heritage 2025.

- US EPA, Supplemental Guidance for Developing Soil Screening Levels for Superfund Sites. In Soil Screening Guidance, United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA): Washington, DC (US), 2002.

- Blanchette, R. A.; Nilsson, T.; Daniel, G.; Abad, A., Biological Degradation of Wood. In Archaeological Wood: Properties, Chemistry and Preservation, Rowell, R. M.; Barbour, R. J., Eds. American Chemical Society: Washington, DC (USA), 1990; Vol. 225, pp 141-174.

- Antonelli, F.; Galotta, G.; Sidoti, G.; Zikeli, F.; Nisi, R.; Davidde Petriaggi, B.; Romagnoli, M., Cellulose and lignin nano-scale consolidants for waterlogged archaeological wood. Frontiers in Chemistry 2020, 8 (32). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, H.; Dong, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, G.; Hou, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Lai, Z., amoA-encoding archaea and thaumarchaeol in the lakes on the northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2013, 4. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A. N.; Yadav, N.; Kour, D.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, K.; Kumar, A.; Rastegari, A. A.; Sachan, S. G.; Singh, B.; Chauhan, V. S.; Saxena, A. K., Chapter 1 - Bacterial community composition in lakes. In Freshwater Microbiology, Bandh, S. A.; Shafi, S.; Shameem, N., Eds. Academic Press: 2019; pp 1-71.

- Nilsson, T.; Björdal, C., Culturing wood-degrading erosion bacteria. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2008, 61 (1), 3-10.

Figure 1.

Seasonal climatic analysis of the Bolsena area for the period 1990–2023 (based on ARSIAL and PC datasets). Results are expressed as the monthly percentage of days. (a) FD0: Frost days, number of says when Tmin ≤ 0 °C; SU30: Hot days, number of days when Tmax ≥ 30 °C; TR20: Tropical nights, number of days when Tmin ≥ 20 °C. (b) R0: Dry days, number of days when PRCP < 1 mm; R10: Heavy precipitation days, number of days when PRCP ≥ 10mm. (c) CDD: Consecutive dry days, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP < 1mm; CWD: Consecutive wet days, maximum number of consecutive, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP ≥ 1mm.

Figure 1.

Seasonal climatic analysis of the Bolsena area for the period 1990–2023 (based on ARSIAL and PC datasets). Results are expressed as the monthly percentage of days. (a) FD0: Frost days, number of says when Tmin ≤ 0 °C; SU30: Hot days, number of days when Tmax ≥ 30 °C; TR20: Tropical nights, number of days when Tmin ≥ 20 °C. (b) R0: Dry days, number of days when PRCP < 1 mm; R10: Heavy precipitation days, number of days when PRCP ≥ 10mm. (c) CDD: Consecutive dry days, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP < 1mm; CWD: Consecutive wet days, maximum number of consecutive, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP ≥ 1mm.

Figure 2.

Climatic analysis of the Bolsena area for the period 1990–2023 (based on ARSIAL and PC datasets). Results are expressed as the annual percentage of days. (a) FD0: Frost days, number of says when Tmin ≤ 0 °C; SU30: Hot days, number of days when Tmax ≥ 30 °C; TR20: Tropical nights, number of days when Tmin ≥ 20 °C. (b) Consecutive dry days per month (May-October) in the period 2014-2023. (c) R0: Dry days, number of days when PRCP < 1 mm; R10: Heavy precipitation days, number of days when PRCP ≥ 10mm. (d) CDD: Consecutive dry days, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP < 1mm; CWD: Consecutive wet days, maximum number of consecutive, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP ≥ 1mm; filled circles indicate that the maximum number of consecutive dry days (CDD) occurred during winter, whereas open circles indicate that the maximum occurred during summer.

Figure 2.

Climatic analysis of the Bolsena area for the period 1990–2023 (based on ARSIAL and PC datasets). Results are expressed as the annual percentage of days. (a) FD0: Frost days, number of says when Tmin ≤ 0 °C; SU30: Hot days, number of days when Tmax ≥ 30 °C; TR20: Tropical nights, number of days when Tmin ≥ 20 °C. (b) Consecutive dry days per month (May-October) in the period 2014-2023. (c) R0: Dry days, number of days when PRCP < 1 mm; R10: Heavy precipitation days, number of days when PRCP ≥ 10mm. (d) CDD: Consecutive dry days, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP < 1mm; CWD: Consecutive wet days, maximum number of consecutive, maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP ≥ 1mm; filled circles indicate that the maximum number of consecutive dry days (CDD) occurred during winter, whereas open circles indicate that the maximum occurred during summer.

Figure 3.

Dataset of water temperature (Tw), dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and electrical conductivity (EC) for the period 2014–2019, provided by the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection of Lazio (ARPA Lazio). All parameters refer to measurements taken in the epilimnion layer.

Figure 3.

Dataset of water temperature (Tw), dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and electrical conductivity (EC) for the period 2014–2019, provided by the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection of Lazio (ARPA Lazio). All parameters refer to measurements taken in the epilimnion layer.

Figure 4.

Monthly mean of the analysed parameters monitored by the multiparametric probe. Tw: Water temperature; DO: dissolved oxygen; pH; Sal: Salinity; Eh: Redox potential; EC: electrical conductivity.

Figure 4.

Monthly mean of the analysed parameters monitored by the multiparametric probe. Tw: Water temperature; DO: dissolved oxygen; pH; Sal: Salinity; Eh: Redox potential; EC: electrical conductivity.

Figure 5.

(a) On 21 August 2022, during an intense drought period accompanied by high temperatures, the Aiola structure appeared significantly more exposed and visibly closer to the shoreline. The lowered lake level is evidenced by the presence of exposed sediments between Aiola and the shore. (b) Comparison of multispectral aerial imagery (OSAVI index) acquired in July and August 2023, highlighting changes in surface conditions and vegetation stress around the site.

Figure 5.

(a) On 21 August 2022, during an intense drought period accompanied by high temperatures, the Aiola structure appeared significantly more exposed and visibly closer to the shoreline. The lowered lake level is evidenced by the presence of exposed sediments between Aiola and the shore. (b) Comparison of multispectral aerial imagery (OSAVI index) acquired in July and August 2023, highlighting changes in surface conditions and vegetation stress around the site.

Figure 6.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for the analysed parameters. Tmin, Tmed, and Tmax refer to minimum, mean, and maximum air temperatures, respectively. PRCP represents precipitation, L indicates lake water level, Tw is water temperature, and TDS denotes total dissolved solids. The term Lag refers to the sum of values recorded 1, 2, or 3 days prior, respectively.

Figure 6.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for the analysed parameters. Tmin, Tmed, and Tmax refer to minimum, mean, and maximum air temperatures, respectively. PRCP represents precipitation, L indicates lake water level, Tw is water temperature, and TDS denotes total dissolved solids. The term Lag refers to the sum of values recorded 1, 2, or 3 days prior, respectively.

Figure 7.

Redox potential (Eh) and pH of sediments measured at the Gran Carro archaeological site from 2021 to 2023. Wsed refers to sediments in direct contact with waterlogged archaeological wood (WAW), while Sed refers to sediments not in contact with WAW.

Figure 7.

Redox potential (Eh) and pH of sediments measured at the Gran Carro archaeological site from 2021 to 2023. Wsed refers to sediments in direct contact with waterlogged archaeological wood (WAW), while Sed refers to sediments not in contact with WAW.

Table 1.

Analysed climatic indices from the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCDDI) of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and United Nations (UN).

Table 1.

Analysed climatic indices from the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCDDI) of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and United Nations (UN).

| ID |

Indicator name |

Definitions |

| FD0 |

Frost days |

Number of days when Tmin ≤ 0 °C |

| SU30 |

Hot days* |

Number of days when Tmax ≥ 30 °C |

| TR20 |

Tropical nights |

Number of days when Tmin ≥ 20 °C |

| R0 |

Dry days |

Number of days when PRCP < 1 mm |

| R10 |

Heavy precipitation days |

Number of days when PRCP ≥ 10mm |

| CDD |

Consecutive dry days |

Maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP < 1mm |

| CWD |

Consecutive wet days |

Maximum number of consecutive days with PRCP ≥ 1mm |

Table 2.

¹ Monthly cumulative mean of precipitation (P) in the years 2014-2019 in Bolsena, dataset from the Italian Service of Civil Defence (PC) and Regional Agency for the Development and Innovation in Agriculture in Lazio (ARSIAL). ² Monthly mean air temperature (Ta) in the years 2014-2019 in Bolsena, dataset from PC and ARSIAL.

Table 2.

¹ Monthly cumulative mean of precipitation (P) in the years 2014-2019 in Bolsena, dataset from the Italian Service of Civil Defence (PC) and Regional Agency for the Development and Innovation in Agriculture in Lazio (ARSIAL). ² Monthly mean air temperature (Ta) in the years 2014-2019 in Bolsena, dataset from PC and ARSIAL.

| 2014-2019 |

P (mm)¹ |

Ta² (°C) |

| Jan |

74.5 |

6.5 |

| Feb |

82.8 |

6.6 |

| Mar |

92.1 |

9.4 |

| Apr |

49.9 |

13.4 |

| May |

65.1 |

16.9 |

| Jun |

47.6 |

21.3 |

| Jul |

38.4 |

24.4 |

| Aug |

32.3 |

24.3 |

| Sep |

67.3 |

20.0 |

| Oct |

83.8 |

15.8 |

| Nov |

123.0 |

11.3 |

| Dec |

83.7 |

7.7 |

Cumulative

Mean |

840.4

70.0 ± 24.5 |

-

14.8 ± 6.4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).