1. Introduction

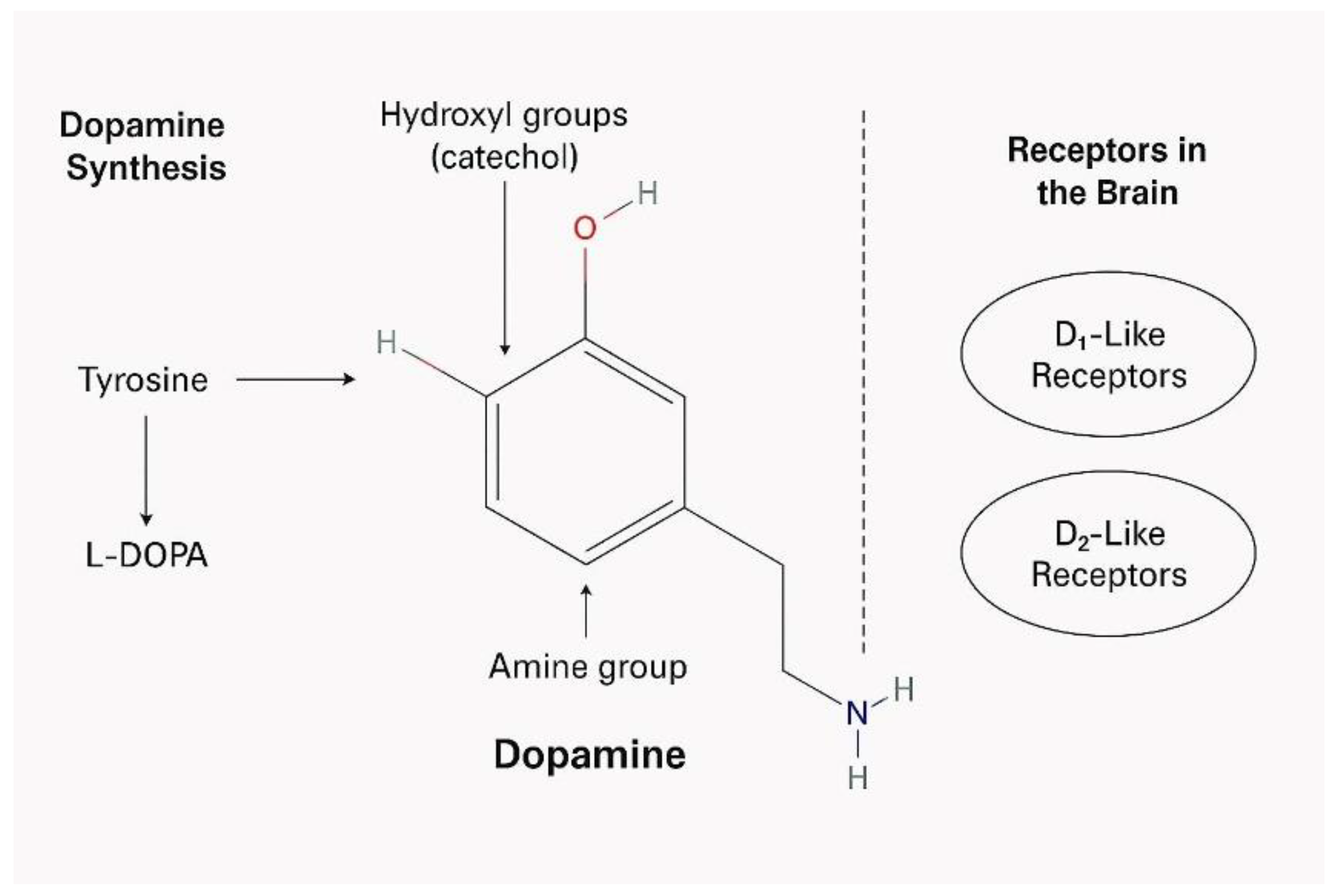

Dopamine is a crucial catecholamine neurotransmitter (

Figure 1) that plays multifaceted roles in the central nervous system, modulating motor control, motivation, cognition, and reward-based behavior [

1]. Its function in the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways underpins emotional processing and executive functions, with alterations in dopaminergic signaling contributing to the pathophysiology of several psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [

2,

3]. For instance, dopamine dysregulation is implicated in major depressive disorder, where altered dopamine transporter density and receptor binding have been documented [

4].

Due to its critical role in mental health, the precise quantification of dopamine levels in biological samples is essential for neurochemical research and clinical diagnostics. Conventional analytical techniques for dopamine detection include high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with electrochemical or fluorescence detection, which offers high sensitivity and selectivity but requires sophisticated instrumentation, extensive sample preparation and skilled personnel [

5]. Capillary electrophoresis with electrochemical detection provides an alternative approach, achieving comparable limits of detection while enabling separation of structurally similar catecholamines [

6]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) are also utilized for dopamine quantification in serum or cerebrospinal fluid, leveraging antibody–antigen specificity, though they often suffer from cross-reactivity and relatively higher detection limits compared to chromatographic methods [

7]. Furthermore, electrochemical techniques based on glassy carbon or modified electrodes have been widely applied for direct dopamine determination, yet they face interference from ascorbic acid and uric acid co-existing in biological matrices [

8]. Despite their analytical robustness, these conventional methods lack portability and are unsuitable for rapid, point-of-care mental health diagnostics, thus motivating the development of novel biosensor-based technologies capable of real-time, cost-effective, and selective dopamine detection to support psychiatric research and personalized treatment strategies [

9].

Beyond detection, real-time monitoring of dopamine–neural cell interactions is critical for understanding synaptic transmission dynamics, receptor pharmacology and neurotoxicity in both basic neuroscience and neuropharmacological screening. Conventional methods for investigating these interactions include patch-clamp electrophysiology, which enables direct measurement of ion channel activity and membrane potential changes upon dopamine receptor stimulation, providing high temporal resolution and mechanistic insights [

10]. However, it is technically demanding, low-throughput, and unsuitable for large-scale screening applications. Fluorescence-based calcium imaging is also widely used to assess dopamine-induced intracellular signaling by measuring changes in calcium fluxes following receptor activation [

11]. While it allows visualization of cellular networks and moderately high-throughput measurements, it often requires fluorescent labeling, potentially altering cellular physiology and involves expensive instrumentation. Electrochemical methods such as fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) have been employed to detect dopamine release and reuptake in neuronal preparations with sub-second resolution [

12]. Although FSCV excels in sensitivity and selectivity for dopamine, it is invasive when used in vivo and does not directly measure cellular electrophysiological responses. In contrast, biosensor-based approaches, particularly Bioelectric Recognition Assays (BERA), offer label-free, real-time, and non-destructive monitoring of dopamine–cell interactions by detecting alterations in membrane potential upon ligand–receptor binding [

13]. Cell-based bioelectric sensors incorporating neuroblastoma or dopaminergic neurons immobilized on electrode arrays can capture complex responses mediated by D1- and D2-like receptors, reflecting the integrated cellular signaling cascade [

14]. These systems measure alterations in membrane potential upon interaction between dopamine and its receptors on immobilized neuronal or neuroblastoma cells, offering high specificity without the need for labeling or complex sample preparation.

Arduino-based microcontroller platforms have gained significant attention in recent years for their integration into biosensor systems due to their affordability, open-source architecture, and ease of programming, enabling rapid prototyping and portable analytical devices [

15]. Arduino boards, such as Arduino Uno and Arduino Nano, have been widely utilized to control electrochemical sensors, optical sensors and bioelectric impedance setups, providing real-time data acquisition and processing capabilities. For example, Arduino has been employed in the development of electrochemical biosensors for detecting environmental contaminants, glucose and various biomolecules by controlling potentiostatic circuits and recording amperometric or voltammetric signals [

16]. Regarding dopamine sensing, Mgenge et al. [

17] recently reported the integration of an silver chromate nanoparticle-based electroanalytical system for the selective recognition of dopamine with an Arduino Uno R4 Wi-Fi module, thus facilitating the transmission of real-time monitoring data to a cloud platform.

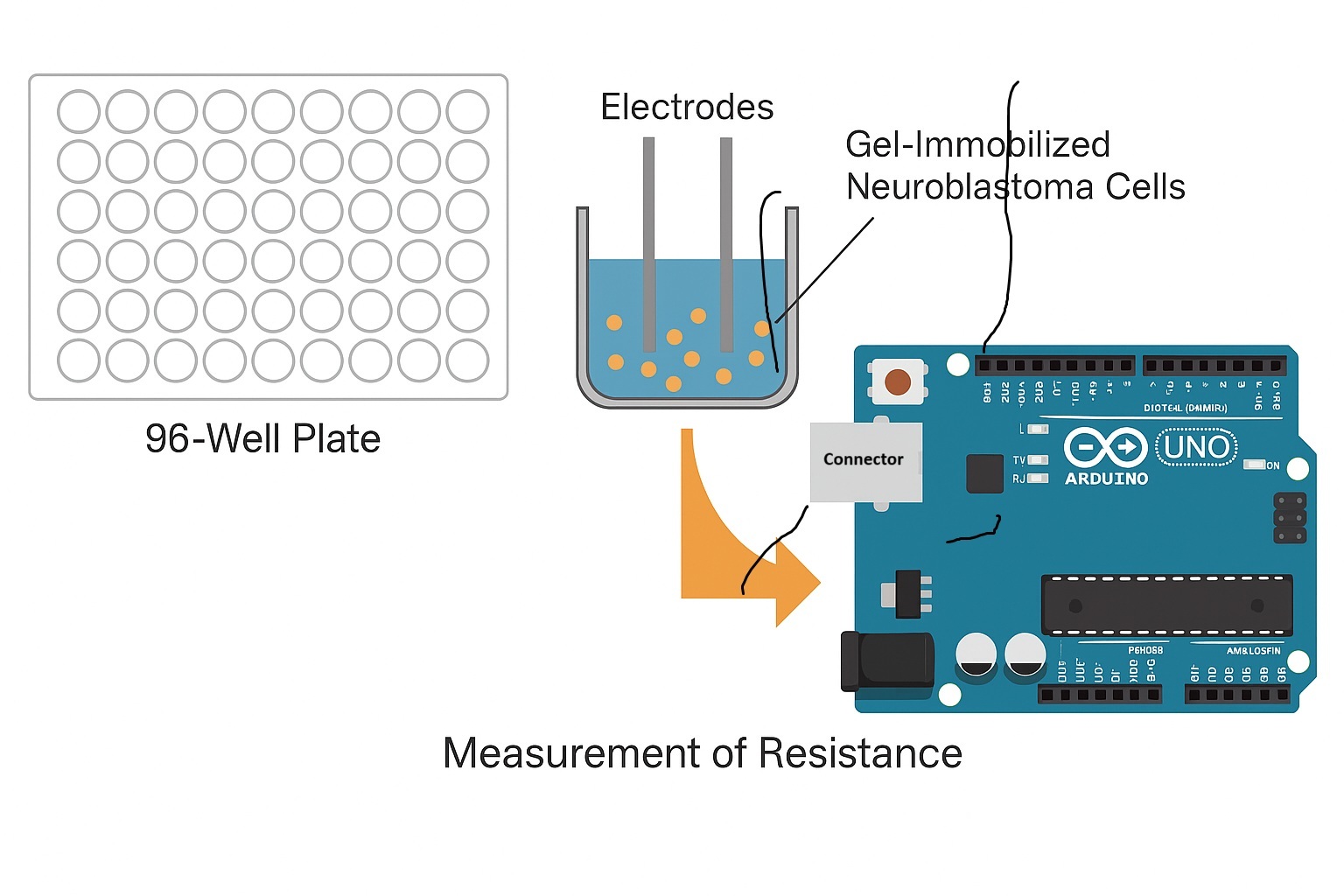

In the present study, we report the design and implementation of a BERA-type bioelectric biosensor based on an Arduino platform for the real-time monitoring of dopaminergic activity in gel-immobilized N2a neuroblastoma cells. In particular, we investigated the concentration-dependent effect of dopamine on the response of neuronal cells in relation to different temperatures (24°C and 37°C) as a key environmental factor in three-dimensional biomimetic cell cultures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Cell Culture and Cell Immobilization

Murine neuroblastoma (N2a) cell cultures were originally provided from LGC Promochem (UK) and subcultured in Dulbecco's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 μgL−1 antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin) and 2 mM L-glutamine which were provided from Invitrogen (CA, USA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). Following subculture, N2a cells were immobilized in a 1.2% low gelling temperature (low melting temperature – LM) agarose matrix. Cell suspensions were diluted with PBS (1:10) before being plated under sterile conditions in ELISA wells and mixed with liquid agar mixture to a total volume of 200 μL per well (containing approx. 50,000 cells). Consequently, immobilized cell cultures were either left to solidify at 24 °C or maintained in semi-liquid form at 37 °C in a CO2 incubation chamber.

2.2. Dopamine Treatment

Dopamine (DA) assays were conducted on immobilized cells on the following day after gel immobilization. DA solutions in double distilled water were prepared freshly on the day of each assay. DA was prepared at concentrations of 100 μM, 1 mM and 10 mM using serial dilutions. Treatment of immobilized cells with DA was achieved by adding 5 μL of solution (containing DA at different concentrations) directly onto the cell-containing wells under light-protected conditions. Temperature control was achieved by using a bespoke water bath.

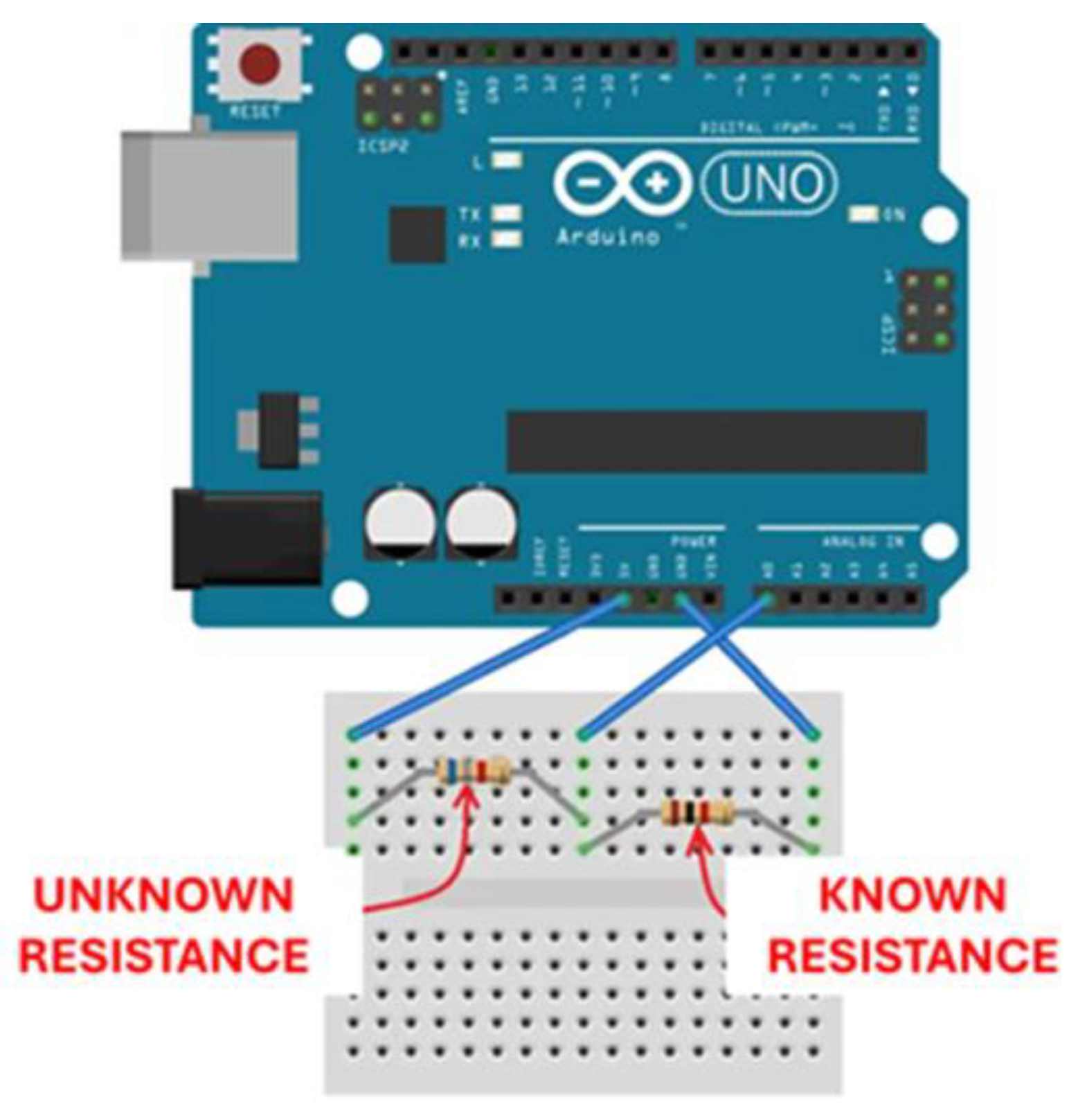

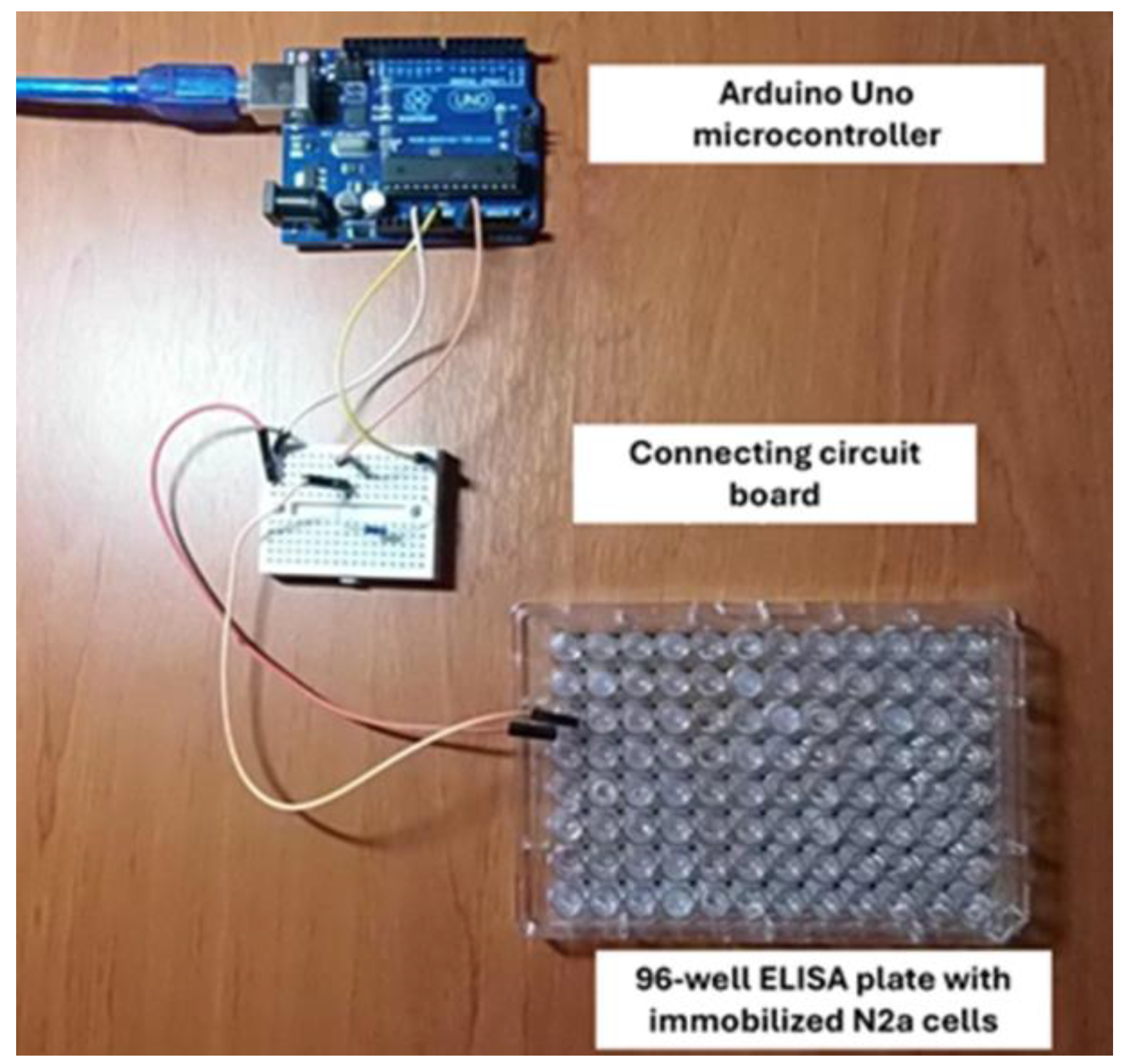

2.3. Bioelectric Biosensor Setup

A custom Arduino-based circuit was developed to measure variable resistance (in this case, the change in resistance of the immobilized N2a cell complex after adding DA at different concentrations and at different temperatures) based on comparison with resistance of known value. The schematics of said circuit are illustrated in the following

Figure 2:

According to the above provision, the known resistance terminals (as a reference base) were connected to the analog input A0 and the ground (GDN), while the electrodes connected to the immobilized cell system (variable, unknown resistance) had one end connected to the 5 V power output and the other common to the known impedance (analog input A0). Resistors of the order of 1kΩ (kOhm) were used as constant-size resistors. The system was connected to a computer on which the variable resistance measurement program was executed (see below). The actual set-up is illustrated in the following

Figure 3:

Electrodes (Ag/AgCl) were inserted into the exact opposite sides of each well to measure the bioelectric response, according to the principles of the Bioelectric Recognition Assay (BERA). In parallel, the resistance of cell-free gel was measured in all treatment combinations. Prior to each measurement, the electrodes were rinsed with PBS each time and cleaned thoroughly with sterile paper.

Variable Resistance Measurement Program

The program (sketch software) to perform variable resistance measurements through Arduino was as follows:

int analogPin= 0;

int raw= 0;

int Vin= 5;

float Vout= 0;

float R1= 1000;

float R2= 0;

float buffer= 0;

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop()

{

raw= analogRead(analogPin);

if(raw)

{

buffer= raw * Vin;

Vout= (buffer)/1024.0;

buffer= (Vin/Vout) -1;

R2= R1 * buffer;

Serial.print("Vout: ");

Serial.println(Vout);

Serial.print("R2: ");

Serial.println(R2);

delay(1000);

}

}

Cell responses were measured as one-minute-long resistance time series. The final readings (in Ohms) were displayed in a txt file and exported in Excel for statistical analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For each temperature tested (24/37 °C), two individual 96-well plates containing gel immobilized cells were used. In each plate, a set of n=24 randomly distributed wells were used for each dopamine concentration tested. In addition, experiments were conducted at eight different dates. Consequently, a total of n= 384 (=24x2x8) individual measurements (resistance time series) were used for each dopamine x temperature combination. As mentioned in 2.3. above, the resistance of cell-free agarose gel in microwells was also measured in parallel during each individual assay and the measured value was subtracted from the cell-containing ge measurements. In this way, measurements were normalized for gel-associated resistance effects. Data were further analyzed using ANOVA to evaluate the effects of dopamine concentration and temperature on cellular response.

3. Results and Discussion

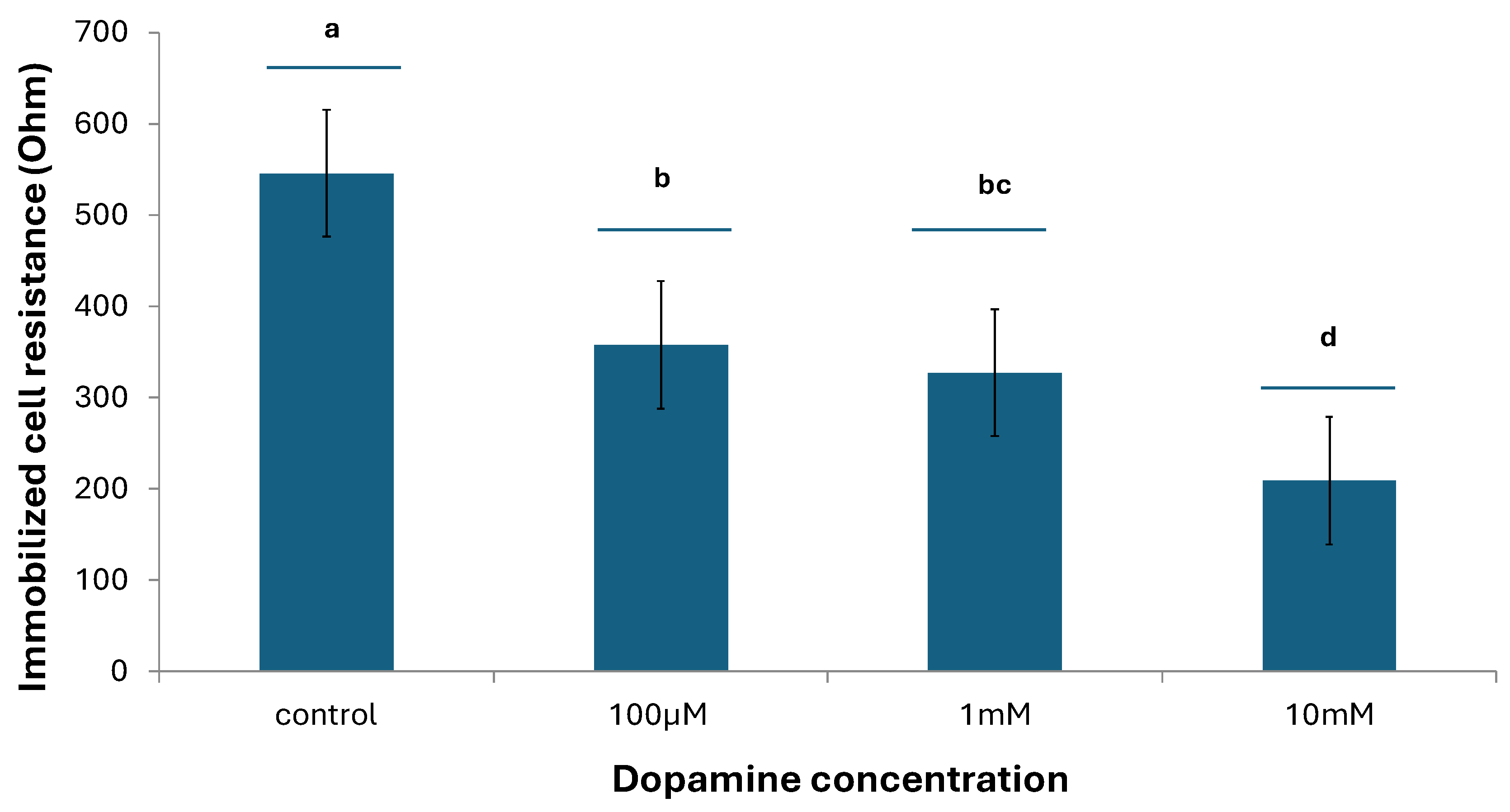

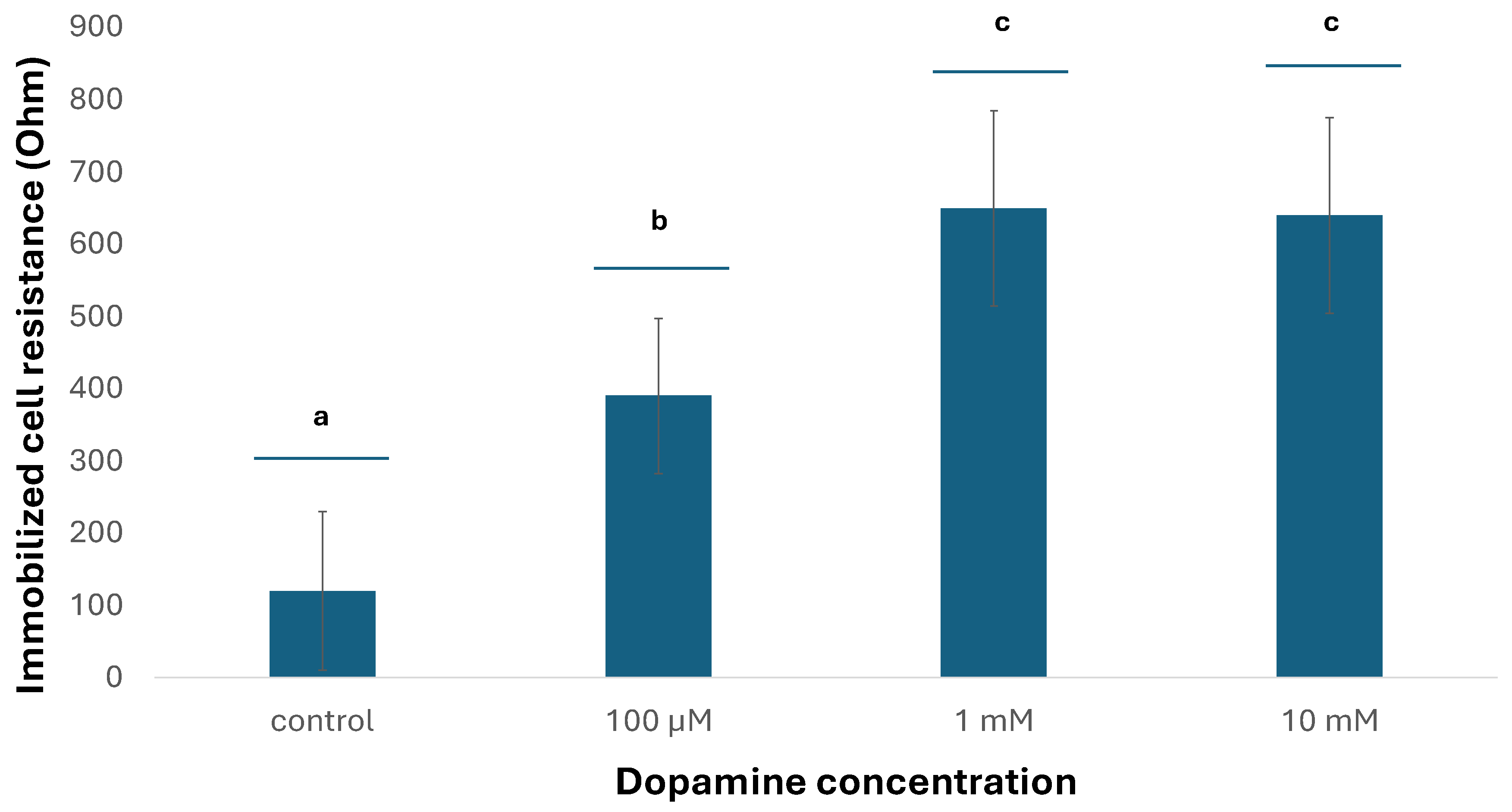

The results showed that there are specific ways of response of the cells at the two different temperatures: at the lower temperature (24 °C), the resistance of immobilized neuroblastoma cells declined with increasing dopamine concentrations, while most differences between concentrations were statistically significant (

Figure 4). On the contrary, an opposite pattern was observed at the higher temperature (37 °C), where the resistance of immobilized neuroblastoma cells increased with increasing dopamine concentrations (

Figure 5). This indicates that temperature does appear to play a particularly significant role in relation to its effect proportionally to the concentration of dopamine in cultured neuroblastoma cells.

In their previous study using a BERA-based biosensor to investigate the effect of dopamine on non-immobilized N2a cells, Apostolou et al. [

14] reported that increasing dopamine concentrations in the range of 1 μM to 1 mM what's correlated with a proportional reduction of the cell membrane potential towards negative values, an effect which was attributed to concentration-dependent membrane hyperpolarization as a result of dopamine D2-receptor activation. On the contrary, at DA concentrations lower than 1 μΜ, an opposite pattern of membrane-depolarization (increase of positive potential) was observed as a result of D1 receptor activation. These findings were in line with the established differential responses of D1 and D2 receptors to different ranges of dopamine concentration in conjuction to cAMP accummulation [

19,

20].

In the present study, N2a cells were immobilized in 1.2% LM agarose gel. This 3D cell immobilization offers a method to simulate the actual cell environment in vivo in a more realistic way than 2D cultures [

21]. It has been previously demonstrated that N2a cells can be maintained in gel for at least three weeks exhibiting normal physiological functions [

22]. However, the gel itself represents a diffusion barrier for even small molecules such as dopamine (molecular weight = 153,18 g/mL), meaning that cells immobilized in it will be exposed to lower DA concentrations then in suspension culture.

In the case of the low melting temperature agarose gel used in the present study, the association between diffusion and temperature can be described by the following equation:

where:

and is dopamine diffusion in water at 24°C (~6 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²s-1) and at 37°C (~7,2 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²s-1), respectively

T is the temperature (in Kelvin)

n is the viscosity (m²s

-1), which increases by approximately 5-7% between 24°C and 37°C for 1.5-2% LM agarose [

23].

Provided that LM agar melts at or below 30°C, incubating immobilized cells at 37 °C means that LM agarose no longer functions as a gel matrix, therefore cell exposure to dopamine largely resembles conditions close to suspension culture. In that case, cell resistance is expected to increase with dopamiine concentration, due to increased membrane hyperpolarization as a result of D2 receptor activation. Indeed, this assumption is corroborated by the findings of the present study at 37 °C (

Figure 5). On the contrary, at 24 °C cells are immobilized in a rigid, solidified gel structure allowing only part of the applied dopamine concentration to reach them. The magnitude of said reduction of the final DA concentration reaching the cells can be described by the following equations [

24]:

where:

K24 = gel permeability factor (dimensionless, <1) is ~0.7 for small molecules in agarose gels, increases by ~5-7% from 24°C to 37°C

D24,gel = effective diffusion coefficient of dopamine at 24°C in gel state

D37,liquid = diffusion coefficient of dopamine at 37°C in liquid (melted) state

In other words, the gel state at 24 °C reduces effective dopamine diffusion by approximately 42% compared to the liquid state at 37 °C. Consequently, immobilized neuroblastoma cells would interact with lower dopamine concentrations, such that could lead to the activation of D1 receptors and cell membrane depolarization, which in turn could be associated with decreased cell electrical resistance.

We should also not overlook the fact that 37 °C is a temperature much more optimal for normal mammalian cell function then 24 °C, meaning that cells cultured at the second, suboptimal temperature may not be fully responsive to dopamine. Naturally, this possibility merits further investigation.

4. Conclusions

In the present study we demonstrate, as proof of concept, that integrated microcontroller systems such as Arduino, combined with a simple bioelectric recording set up, can be used as a cost efficient and user-friendly platform for screening the bio activity of neurotransmitters, as the first step before employing more elaborate and sophisticated analytical tools. Its integration with wireless modules (e.g., Bluetooth or Wi-Fi) facilitates remote monitoring applications, enhancing usability in point-of-care diagnostics and in-field analyses [

25]. Additionally, Arduino platforms can be combined with smartphone applications to visualize and store biosensor data in real-time, expanding their accessibility in resource-limited settings [

26].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; software, S.K; validation, M.P.,; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K., M.P.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; supervision, S.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data (3.072 cell resistance time series) supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADHD |

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| BERA |

Bioelectric Recognition Assay |

| DA |

Dopamine |

| FSCV |

Fast-scan cyclic voltametry |

| HPLC |

High performance liquid chromatography |

| LM |

Low melting temperature |

References

- Dunlop, B.W.; Nemeroff, C.B. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, O.D.; Kapur, S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: Version III—the final common pathway. Schizophr. Bull. 2009, 35, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, A.A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belujon, P.; Grace, A.A. Dopamine system dysregulation in major depressive disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mefford, I.N. Application of high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection to neurochemical analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 1981, 3, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, B.; Song, E. Recent Advances in the Detection of Neurotransmitters. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Johnson, M.; Mandal, R.; Cruz, M.; Martínez-Huélamo, M.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Wishart, D.S. A Comprehensive LC–MS Metabolomics Assay for Quantitative Analysis of Serum and Plasma. Metabolites 2024, 14, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, A.J.S.; Lee, J.-J.; Rahman, M.A. Electrochemical Sensors Based on Carbon Nanotubes. Sensors 2009, 9, 2289–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. Graphene-based biosensors for detection of biomarkers. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakmann, B.; Neher, E. Patch clamp techniques for studying ionic channels in excitable membranes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1984, 46, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynkiewicz, G.; Poenie, M.; Tsien, R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 3440–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.L.; Venton, B.J.; Heien, M.L.; Wightman, R.M. Detecting subsecond dopamine release with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in vivo. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintzios, S.; Pistola, E.; Panagiotopoulos, P.; Bomsel, M.; Alexandropoulos, N.; Bem, F.; Ekonomou, G.; Biselis, J.; Levin, R. Bioelectric recognition assay (BERA). Biosens Bioelectron. 2001, 16, 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolou, T.; Moschopoulou, G.; Kolotourou, E.; Kintzios, S. Assessment of in vitro dopamine-neuroblastoma cell interactions with a bioelectric biosensor: perspective for a novel in vitro functional assay for dopamine agonist/antagonist activity. Talanta 2017, 170, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caux, M.; Achit, A.; Var, K.; Boitel-Aullen, G.; Rose, D.; Aubouy, A.; Argentieri, S.; Campagnolo, R.; Maisonhaute, E. PassStat, a simple but fast, precise and versatile open source potentiostat. HardwareX 2022, 11, e00290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; Farahani, A.; Docoslis, A.; Vahdatifar, S. Developing an integrated microfluidic and miniaturized electrochemical biosensor for point of care determination of glucose in human plasma samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021, 413, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgenge, L.; Saha, C.; Kumari, P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Singh, H.; Mallick, K. Electrochemical sensing of dopamine using nanostructured silver chromate: Development of an IoT-integrated sensor. Anal Biochem. 2025, 698, 115726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrikou, S.; Tsekouras, V.; Karageorgou, M.-A.; Moschopoulou, G.; Kintzios, S. Detection of Superoxide Alterations Induced by 5-Fluorouracil on HeLa Cells with a Cell-Based Biosensor. Biosensors 2019, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, A.A.; Bunney, B.S. The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: burst firing. J. Neurosci. 1984, 4, 2877–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missale, C.; Nash, S.R.; Robinson, S.W.; Jaber, M.; Caron, M.G. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 1998, 78, 189–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumèche, B.; Küppers, M.; Stapf, S.; Blümich, B.; Hartmeier, W.; Ansorge-Schumacher, M.B. Immobilization of enzymes within agarose gels: assessment by NMR microscopy. J. Microencapsul. 2004, 21, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsanakis, N.; Katsivelis, A.; Kintzios, S. Immobilization of Electroporated Cells for Fabrication of Cellular Biosensors: Physiological Effects of the Shape of Calcium Alginate Matrices and Foetal Calf Serum. Sensors 2009, 9, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.; Hsu, J.T. Modelling the effect of temperature on the gel-filtration chromatographic protein separation, Comp. Chem. Engineer. 2018, 112, 304–315. [Google Scholar]

- Peppas, N.A.; Bures, P.; Leobandung, W.; Ichikawa, H. Hydrogels in pharmaceutical formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2000, 50, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Ghani, M.A.; Nordin, A.N.; Zulhairee, M.; Che Mohamad Nor, A.; Shihabuddin Ahmad Noorden, M.; Muhamad Atan, M.K.F.; Ab Rahim, R.; Mohd Zain, Z. Portable Electrochemical Biosensors Based on Microcontrollers for Detection of Viruses: A Review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardini, E.; Serpelloni, M.; Tonello, S. Printed Electrochemical Biosensors: Opportunities and Metrological Challenges. Biosensors 2020, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).