Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Behavioral and Ponderal Variables During Adolescence

2.2. Long-Term Effects of CVS on Voluntary Exercise

2.3. Voluntary Exercise Decreases Food Intake

2.4. Long Term Effects of CVS on ARC and Serum Markers of Energy Homeostasis in Mild Food Restriction and Exercise

2.5. CVS Alters HPA Responses to Mild Food Restriction and Exercise

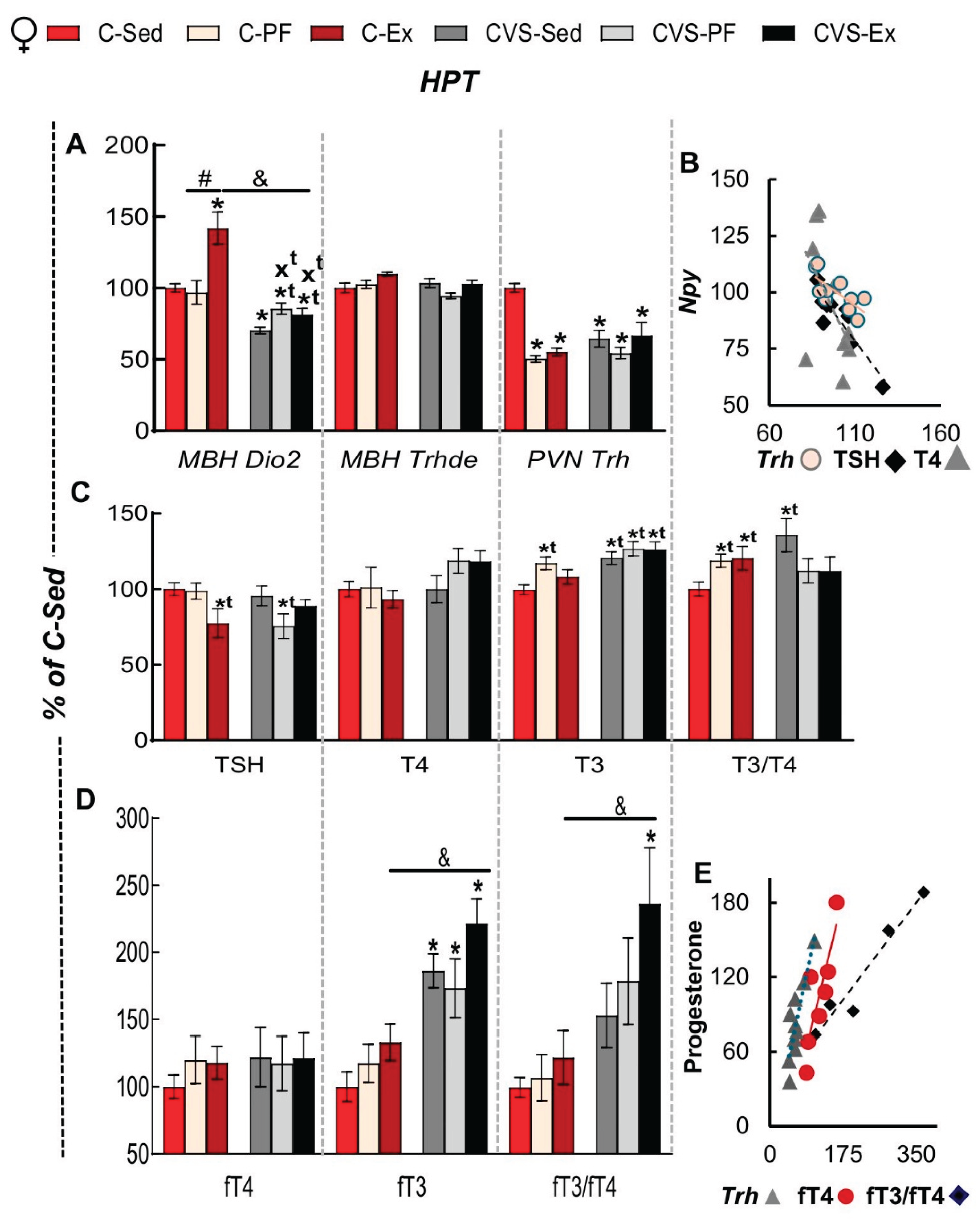

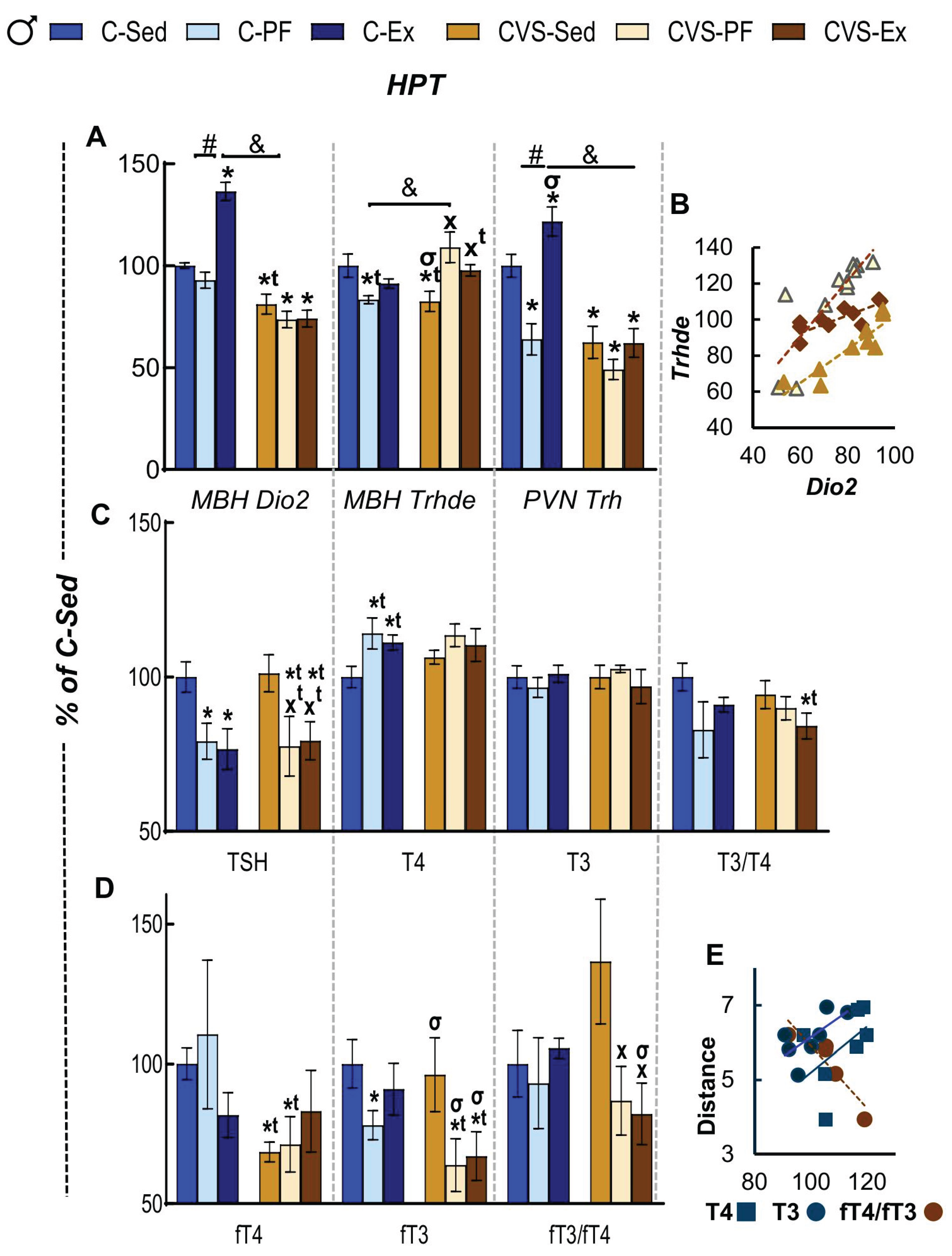

2.6. Long Term Effects of CVS on HPT Axis Activity in Mild Food Restriction and Exercise

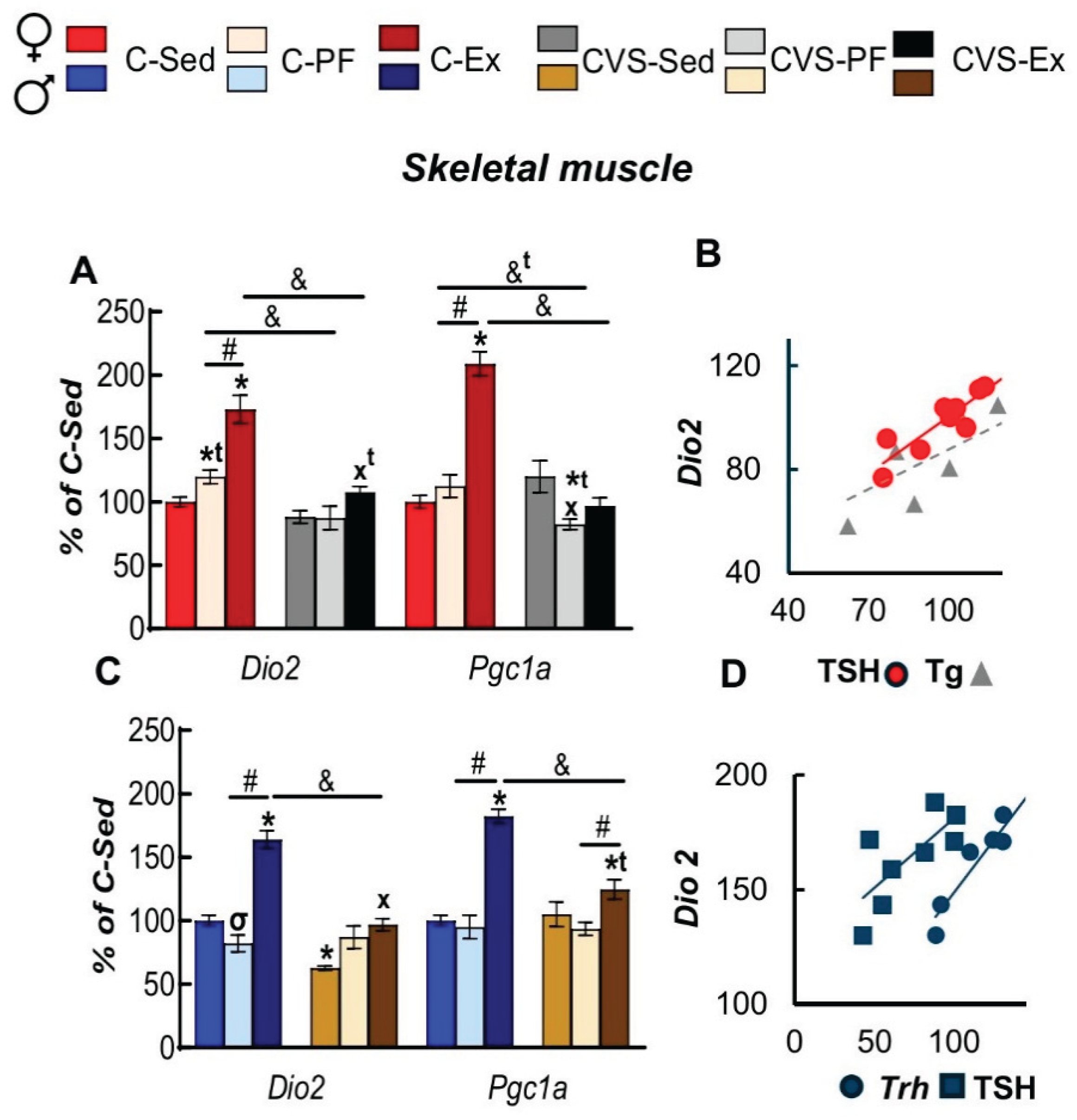

2.7. Long Term Effects of CVS on Gene Expression in SKM, WAT and BAT in Mild Food Restriction and Exercise

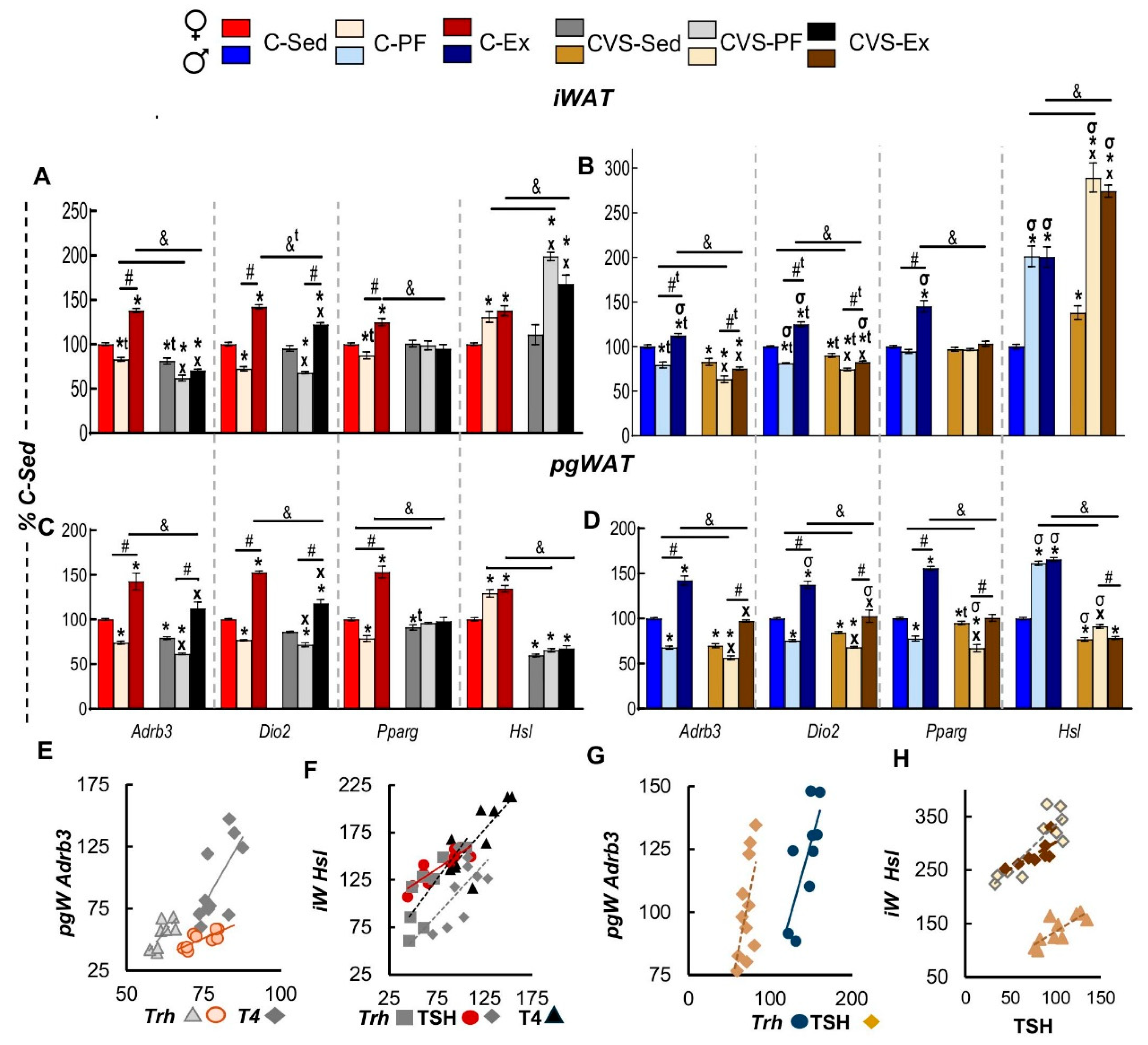

2.7.1. Inguinal and Perigonadal WAT (iWAT, pgWAT)

2.7.2. Brown Adipose Tissue

2.8. Correlation Analyses

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Experimental Groups

4.2. Behavioral Tests

Open Field Test (OFT)

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

4.3. Voluntary Exercise

4.4. Tissue Collection

4.5. Brain Dissections

4.6. Biochemical Measurements

Hormone quantification in serum

4.7. RNA Extraction and mRNA Quantification

4.8. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTH: | corticotrophin |

| Adrb3: | adrenergic receptor β3 |

| AgRP: | Agouti-related peptide |

| ARC: | arcuate nucleus |

| Avp: | Arginine vasopressin |

| BAT: | brown adipose tissue |

| BW: | body weight |

| BWg: | body weight gain |

| C: | control |

| Cort: | corticosterone |

| CR: | calorie restriction |

| CRH: | corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| CVS: | chronic variable stress |

| Dio1: | deiodinase 1 |

| Dio2: | deiodinase 2 |

| Dio3: | deiodinase 3 |

| EPM: | Elevated Plus Maze |

| Ex: | exercised (voluntary wheel-running) |

| FE: | food efficiency |

| FI: | Food Intake |

| fT3: | free T3 |

| fT4: | free T4 |

| Gr: | Glucocorticoid receptor |

| HPA: | hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal |

| Hprt: | hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 |

| HPT: | hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid |

| HSL (Lipe): | hormone sensitive lipase |

| IL-16: | Interleukin-16 |

| iWAT: | inguinal WAT |

| MBH: | mediobasal hypothalamus |

| NPY: | Neuropeptide Y |

| OFT: | Open Field Test |

| P4: | Progesterone |

| PAS: | photobeam activity system |

| PF: | pair-fed |

| Pgc-1α: | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α |

| pgWAT: | perigonadal WAT |

| PND: | post-natal day |

| POMC: | Pro-opiomelanocortin |

| Ppia: | cyclophilin A |

| Pparg: | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ |

| PRL: | Prolactin |

| PVN: | paraventricular nucleus |

| RFI: | relative food intake |

| SCH: | subclinical hypothyroidism |

| Sed: | sedentary |

| SKM: | skeletal muscles |

| T3: | Triiodothyronine |

| T4: | Thyroxine |

| Tg: | triglycerides |

| TH: | Thyroid hormones |

| TRH: | thyrotropin-releasing hormone |

| TRH-DE (Trhde): | TRH-degrading ectoenzyme |

| TSH: | thyrotropin |

| Ucp1: | uncoupling protein-1 |

| WAT: | white adipose tissues |

| WR: | wheel running |

References

- Kerr,N.R.; Booth,F.W. Contributions of physical inactivity and sedentary behavior to metabolic and endocrine diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33(12):817-827. [CrossRef]

- McEwen,B.S.; Akil,H. Revisiting the Stress Concept:Implications for Affective Disorders. J Neurosci. 2020;40(1):12-21. [CrossRef]

- Agorastos A.; Chrousos G.P. The neuroendocrinology of stress:the stress-related continuum of chronic disease development. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):502-513. [CrossRef]

- Hird EJ; Slanina-Davies A; Lewis G; Hamer M; Roiser JP. From movement to motivation:a proposed framework to understand the antidepressant effect of exercise. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):273. [CrossRef]

- Esteves JV; Stanford KI. Exercise as a tool to mitigate metabolic disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;327(3):C587-C598. [CrossRef]

- Chow LS; Gerszten RE; Taylor JM; Pedersen BK; van Praag H; Trappe S; Febbraio MA; Galis ZS; Gao Y; Haus JM; Lanza IR; Lavie CJ; Lee CH; Lucia A; Moro C; Pandey A; Robbins JM; Stanford KI; Thackray AE; Villeda S; Watt MJ; Xia A; Zierath JR; Goodpaster BH; Snyder MP. Exerkines in health; resilience; disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(5):273-289. [CrossRef]

- Murphy,R.M.; Watt,M.J.; Febbraio,M.A. Metabolic communication during exercise. Nat Metab. 2020;2(9):805-816. [CrossRef]

- Hwang,E.; Portillo,B.; Grose,K.; Fujikawa,T.; Williams,K.W. Exercise-induced hypothalamic neuroplasticity:Implications for energy and glucose metabolism. Mol Metab. 2023;73:101745. [CrossRef]

- Quarta C; Claret M; Zeltser LM; Williams KW; Yeo GSH; Tschöp MH; Diano S; Brüning JC; Cota D. POMC neuronal heterogeneity in energy balance; beyond:an integrated view. Nat Metab. 2021;3(3):299-308. [CrossRef]

- Lorsignol A; Rabiller L; Labit E; Casteilla L; Pénicaud L. The nervous system; adipose tissues:a tale of dialogues. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2023;325(5):E480-E490. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z; Su J; Tang J; Chung L; Page JC; Winter CC; Liu Y; Kegeles E; Conti S; Zhang Y; Biundo J; Chalif JI; Hua CY; Yang Z; Yao X; Yang Y; Chen S; Schwab JM; Wang KH; Chen C; Prerau MJ; He Z. -Spinal projecting neurons in rostral ventromedial medulla co-regulate motor; sympathetic tone. Cell. 2024;187(13):3427-3444. e21. [CrossRef]

- Carpentier AC; Blondin DP; Haman F; Richard D. Brown Adipose Tissue-A Translational Perspective. Endocr Rev. 2023;44(2):143-192d. oi:10.1210/endrev/bnac015.13. Mishra G; Townsend KL. The metabolic; functional roles of sensory nerves in adipose tissues. Nat Metab. 5(9):1461-1474. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo P; Jaimes-Hoy L; Uribe RM; Charli JL. 2015;60 YEARS OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY:TRH; the first hypophysiotropic releasing hormone isolated:control of the pituitary-thyroid axis. J Endocrinol. 226(2):T85-T100. [CrossRef]

- Costa-E-Sousa,R.H.; Rorato,R.; Hollenberg,A.N.; Vella,K.R. Regulation of Thyroid Hormone Levels by Hypothalamic Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons. Thyroid. 2023;33(7):867-876. [CrossRef]

- Herman JP. The neuroendocrinology of stress:Glucocorticoid signaling mechanisms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 137:105641. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sinha RA; Yen PM. Metabolic Messengers:Thyroid Hormones. Nat Metab. 2024;6(4):639-650. [CrossRef]

- Jimeno B; Verhulst S. Meta-analysis reveals glucocorticoid levels reflect variation in metabolic rate; not ‘stress’. Elife. 2023;12:RP88205. [CrossRef]

- Russo SC; Salas-Lucia F; Bianco AC. Deiodinases; the Metabolic Code for Thyroid Hormone Action. Endocrinology. 2021;162(8):bqab059. [CrossRef]

- Köhrle,J.; Frädrich,C. Deiodinases control local cellular and systemic thyroid hormone availability. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;193(Pt 1):59-79. [CrossRef]

- Fekete,C.; Lechan; R. M. Central regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis under physiological; pathophysiological conditions. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(2), 159-194; [CrossRef]

- Sánchez E; Vargas MA; Singru PS; Pascual I; Romero F; Fekete C; Charli JL; Lechan RM. Tanycyte pyroglutamyl peptidase II contributes to regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis through glial-axonal associations in the median eminence. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2283-91. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez A; Lazcano I; Sánchez-Jaramillo E; Uribe RM; Jaimes-Hoy L; Joseph-Bravo P; Charli JL. Tanycytes; the Control of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Flux Into Portal Capillaries. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:401. [CrossRef]

- Ruisseau PD; Taché Y; Brazeau P; Collu R. Pattern of adenohypophyseal hormone changes induced by various stressors in female; male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1978;27(5-6):257-71. [CrossRef]

- Uribe RM; Redondo JL; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Suckling; cold stress rapidly; transiently increase TRH mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58(1):140-5. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Mariscal M; Sánchez E; García-Vázquez A; Rebolledo-Solleiro D; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Acute response of hypophysiotropic thyrotropin releasing hormone neurons; thyrotropin release to behavioral paradigms producing varying intensities of stress; physical activity. Regul Pept. 2012;179(1-3):61-70. [CrossRef]

- Uribe RM; Jaimes-Hoy L; Ramírez-Martínez C; García-Vázquez A; Romero F; Cisneros M; Cote-Vélez A; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Voluntary exercise adapts the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis in male rats. Endocrinology. 2014;155(5):2020-30. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato RS; Ignácio DL; Padron AS; Peçanha R; Marassi MP; Rosenthal D; Werneck-de-Castro JPS; Carvalho DP. The effect of acute exercise session on thyroid hormone economy in rats. J Endocrinol. 2008;198(2):347-53. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo,P.; Jaimes-Hoy,L.; Charli,J.L. Regulation of TRH neurons and energy homeostasis-related signals under stress. J Endocrinol. 2015;224(3):R139-59. [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou,A.; Tziaferi,V.; Toumba,M. Stress, Thyroid Dysregulation, and Thyroid Cancer in Children and Adolescents:Proposed Impending Mechanisms. Horm Res Paediatr. 4477;2023;96(1):44-53. [CrossRef]

- Hackney,A.C.; Saeidi,A. The thyroid axis, prolactin, and exercise in humans. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 9, 45–50. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lankhaar,J.A.; deVries,W.R.; Jansen,J.A.; Zelissen,P.M.; Backx,F.J. Impact of overt and subclinical hypothyroidism on exercise tolerance:a systematic review. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 85(3), 365–389. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou,N.; Bogdanis,G.C.; Mastorakos,G. Endocrine responses of the stress system to different types of exercise. Rev Endocr Metab Disor. 24(2), 251–266. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Murphy,R.M.; Watt,M.J.; Febbraio,M.A. Metabolic communication during exercise. Nature metabolism, 2(9), 805–816. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lundsgaard,A.M.; Fritzen,A.M.; Kiens,B. The Importance of Fatty Acids as Nutrients during Post-Exercise Recovery. Nutrients, 12(2), 280. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bloise FF; Cordeiro A; Ortiga-Carvalho TM. Role of thyroid hormone in skeletal muscle physiology. J Endocrinol. 2018;236(1):R57-R68. [CrossRef]

- Bocco BM; Louzada RA; Silvestre DH; Santos MC; Anne-Palmer E; Rangel IF; Abdalla S; Ferreira AC; Ribeiro MO; Gereben B; Carvalho DP; Bianco AC; Werneck-de-Castro JP. Thyroid hormone activation by type 2 deiodinase mediates exercise-induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α expression in skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2016;594(18):5255-69. [CrossRef]

- Silva JE; Bianco SD. Thyroid-adrenergic interactions:physiological; clinical implications. Thyroid. 2008;18(2):157-65. [CrossRef]

- Mullur R; Liu YY; Brent GA. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(2):355-82. [CrossRef]

- Guilherme A; Yenilmez B; Bedard AH; Henriques F; Liu D; Lee A; Goldstein L; Kelly M; Nicoloro SM; Chen M; Weinstein L; Collins S; Czech MP. Control of Adipocyte Thermogenesis; Lipogenesis through β3-Adrenergic; Thyroid Hormone Signal Integration. Cell Rep. 2020;31(5):107598. [CrossRef]

- Müller P; Leow MK-S; Dietrich JW. Minor perturbations of thyroid homeostasis and major cardiovascular endpoints—Physiological mechanisms and clinical evidence. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022;9:942971. [CrossRef]

- Sotelo-Rivera I; Jaimes-Hoy L; Cote-Vélez A; Espinoza-Ayala C; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. An acute injection of corticosterone increases thyrotrophin-releasing hormone expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus but interferes with the rapid hypothalamus pituitary thyroid axis response to cold in male rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2014;26(12):861-9. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Campos A; Gutiérrez-Mata A; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Chronic stress inhibits hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis; brown adipose tissue responses to acute cold exposure in male rats. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(4):713-723. [CrossRef]

- Parra-Montes de Oca MA; Gutiérrez-Mariscal M; Salmerón-Jiménez MF; Jaimes-Hoy L; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Voluntary Exercise-Induced Activation of Thyroid Axis; Reduction of White Fat Depots Is Attenuated by Chronic Stress in a Sex Dimorphic Pattern in Adult Rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:418. [CrossRef]

- Weaver IC; Diorio J; Seckl JR; Szyf M; Meaney MJ. Early environmental regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression:characterization of intracellular mediators; potential genomic target sites. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1024:182-212. [CrossRef]

- Jaimes-Hoy L; Romero F; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Sex Dimorphic Responses of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis to Maternal Separation; Palatable Diet. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:445. [CrossRef]

- Jaimes-Hoy L; Pérez-Maldonado A; Narváez Bahena E; de la Cruz Guarneros N; Rodríguez-Rodríguez A; Charli JL; Soberón X; Joseph-Bravo P. Sex Dimorphic Changes in Trh Gene Methylation; Thyroid-Axis Response to Energy Demands in Maternally Separated Rats. Endocrinology. 2021;162(8):bqab110. [CrossRef]

- Vella KR; Hollenberg AN. Early Life Stress Affects the HPT Axis Response in a Sexually Dimorphic Manner. Endocrinology. 2021;162(9):bqab137. [CrossRef]

- Biondi B; Cooper DS. Thyroid hormone therapy for hypothyroidism. Endocrine. 2019;66(1):18-26. [CrossRef]

- 49. Baksi,S.; Pradhan,A. Thyroid hormone:sex-dependent role in nervous system regulation and disease. Biology of sex differences, 12(1), 25. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Heck AL; Handa RJ. Sex differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis’ response to stress:an important role for gonadal hormones. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(1):45-58. [CrossRef]

- Parra-Montes de Oca MA; Sotelo-Rivera I; Gutiérrez-Mata A; Charli JL; Joseph-Bravo P. Sex Dimorphic Responses of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis to Energy Demands; Stress Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:746924. [CrossRef]

- Chen J; Zhang L; Zhang X. Overall, sex-and race/ethnicity-specific prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in US adolescents aged 12–18 years. Front Public Health 12:1366485. [CrossRef]

- Romeo RD. The metamorphosis of adolescent hormonal stress reactivity:A focus on animal models. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;49:43-51. [CrossRef]

- Drzewiecki,C.M.; Juraska,J.M. The structural reorganization of the prefrontal cortex during adolescence as a framework for vulnerability to the environment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2020;199, 173044. [CrossRef]

- Schneider M. Adolescence as a vulnerable period to alter rodent behavior. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354(1):99-106. [CrossRef]

- McCormick CM. Methods; Challenges in Investigating Sex-Specific Consequences of Social Stressors in Adolescence in Rats:Is It the Stress or the Social or the Stage of Development? Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2022;54:23-58. [CrossRef]

- Holder MK; Blaustein JD. Puberty; adolescence as a time of vulnerability to stressors that alter neurobehavioral processes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(1):89-110. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti-de-Albuquerque,J.P.; Donato,J.; Jr. Rolling out physical exercise and energy homeostasis:Focus on hypothalamic circuitries. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;63:100944. [CrossRef]

- nt. Neuroendocrinol. 2009;63, 100944. 2021. Lafontan M; Langin D. Lipolysis; lipid mobilization in human adipose tissue. Prog Lipid Res. 48(5):275-97. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner,A.; Hiedra,L.; Pinna,G.; Eravci,M.; Prengel,H.; Meinhold,H. Rat brain type II 5’-iodothyronine deiodinase activity is extremely sensitive to stress. J Neurochem. 1998;71(2), 817–826. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-deMena,R.; Calvo,R.M.; Garcia,L.; Obregon,M.J. Effect of glucocorticoids on the activity, expression and proximal promoter of type II deiodinase in rat brown adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;428, 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Queathem ED; Welly RJ; Clart LM; Rowles CC; Timmons H; Fitzgerald M; Eichen PA; Lubahn DB; Vieira-Potter VJ. White Adipose Tissue Depots Respond to Chronic Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor Activation in a Sexually Dimorphic; Depot Divergent Manner Cells. 2021;10(12):3453. [CrossRef]

- Pereira,V.H.; Marques,F.; Lages,V.; Pereira,F.G.; Patchev,A.; Almeida,O.F.; Almeida-Palha,J.; Sousa,N.; Cerqueira,J.J. Glucose intolerance after chronic stress is related with downregulated PPAR-γ in adipose tissue. Cardiovascular diabetology, 15(1), 114. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Holm C; Osterlund T; Laurell H; Contreras JA. Molecular mechanisms regulating hormone-sensitive lipase; lipolysis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:365-93. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda K; Yamada T. UCP1 Dependent; Independent Thermogenesis in Brown; Beige Adipocytes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:498. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care; Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care; Use of Laboratory Animals. 2011;8th ed. Washington (DC):National Academies Press (US);. PMID:21595115.

- Toth E; Gersner R; Wilf-Yarkoni A; Raizel H; Dar DE; Richter-Levin G; Levit O; Zangen A. Age-dependent effects of chronic stress on brain plasticity; depressive behavior. J Neurochem. 2008;107(2):522-32. [CrossRef]

- Basso JC; Morrell JI. Using wheel availability to shape running behavior of the rat towards improved behavioral; neurobiological outcomes. J Neurosci Methods. 2017;290:13-23. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.07.009.

- Perelló M; Chacon F; Cardinali DP; Esquifino AI; Spinedi E. Effect of social isolation on 24-h pattern of stress hormones; leptin in rats. Life Sci. 2006;78(16):1857-62. [CrossRef]

- Paxinos; George; Watson; Charles. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates–The New Coronal Set, 5th Edn.

- Goodman T.; Hajihosseini M.K. Hypothalamic tanycytes-masters and servants of metabolic, neuroendocrine, and neurogenic functions. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:387. [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski P; Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction:twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(2):581-5. [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski M; Birol I; Jones S; Marra M. Hive Plots — Rational Approach to Visualizing Networks. Brief Bioinform. 2012;13(5):627-44. [CrossRef]

- Jankord,R.; Solomon,M.B.; Albertz,J.; Flak,J.N.; Zhang,R.; Herman,J.P. Stress vulnerability during adolescent development in rats. Endocrinology, 152, 629–638. [CrossRef]

- Cotella EM; Gómez AS; Lemen P; Chen C; Fernández G; Hansen C; Herman JP; Paglini MG. Long-term impact of chronic variable stress in adolescence versus adulthood. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;10; 88:303-310. [CrossRef]

- Wulsin,A.C.; Wick-Carlson,D.; Packard,B.A.; Morano,R.; Herman,J.P. Adolescent chronic stress causes hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical hypo-responsiveness and depression-like behavior in adult female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 65, 109–117. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Smith,B.L.; Morano,R.L.; Ulrich-Lai,Y.M.; Myers,B.; Solomon,M.B.; Herman,J.P. Adolescent environmental enrichment prevents behavioral and physiological sequelae of adolescent chronic stress in female (but not male) rats. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 21(5), 464–473. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood BN; Fleshner M. Voluntary Wheel Running:A Useful Rodent Model for Investigating the Mechanisms of Stress Robustness; Neural Circuits of Exercise Motivation. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2019;28:78-84. [CrossRef]

- Mathis V; Wegman-Points L; Pope B; Lee CJ; Mohamed M; Rhodes JS; Clark PJ; Clayton S; Yuan LL. Estrogen-mediated individual differences in female rat voluntary running behavior. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2024 136(3):592-605. [CrossRef]

- Casillas F; Flores-González A; Juárez-Rojas L; López A; Betancourt M; Casas E; Bahena I; Bonilla E; Retana-Márquez S. Chronic stress decreases fertility parameters in female rats. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2023;69(3):234-244. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar AS Jr; Speck AE; Amaral IM; Canas PM; Cunha RA. The exercise sex gap; the impact of the estrous cycle on exercise performance in mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10742. [CrossRef]

- Suchacki KJ; Thomas BJ; Ikushima YM; Chen KC; Fyfe C; Tavares AAS; Sulston RJ; Lovdel A; Woodward HJ; Han X; Mattiucci D; Brain EJ; Alcaide-Corral CJ; Kobayashi H; Gray GA; Whitfield PD; Stimson RH; Morton NM; Johnstone AM; Cawthorn WP. The effects of caloric restriction on adipose tissue; metabolic health are sex-; age-dependent. Elife. 2023;12:e88080. [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences in energy metabolism:natural selection; mechanisms; consequences. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20(1):56-69. [CrossRef]

- Harris RB. Chronic; acute effects of stress on energy balance:are there appropriate animal models? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308(4):R250-65. [CrossRef]

- Münzberg,H.; Singh,P.; Heymsfield,S.B.; Yu,S.; Morrison,C.D. Recent advances in understanding the role of leptin in energy homeostasis. F1000Res. 2020 ; 9:F1000 Faculty Rev-451. [CrossRef]

- López López AL; Escobar Villanueva MC; Brianza Padilla M; Bonilla Jaime H; Alarcón Aguilar FJ. Chronic unpredictable mild stress progressively disturbs glucose metabolism; appetite hormones in rats. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2018;14(1):16-23. [CrossRef]

- Sasse SK; Nyhuis TJ; Masini CV; Day HE; Campeau S. Central gene expression changes associated with enhanced neuroendocrine; autonomic response habituation to repeated noise stress after voluntary wheel running in rats. Front Physiol. 2013;4:341. [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen M; Wilsgaard T; Grimsgaard S; Hopstock LA; Hansson P. Associations between postprandial triglyceride concentrations; sex; age; body mass index:cross-sectional analyses from the Tromsø study 2015-2016. Front Nutr. 2023. 10:1158383. [CrossRef]

- Holcomb LE; Rowe P; O’Neill CC; DeWitt EA; Kolwicz SC Jr. Sex differences in endurance exercise capacity; skeletal muscle lipid metabolism in mice. Physiol Rep. 2022;10(3):e15174. [CrossRef]

- Brady LS; Smith MA; Gold PW; Herkenham M. Altered expression of hypothalamic neuropeptide mRNAs in food-restricted; food-deprived rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;52(5):441-7. [CrossRef]

- Loh K; Herzog H; Shi YC. Regulation of energy homeostasis by the NPY system. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(3):125-35. [CrossRef]

- He,Z.; Gao,Y.; Alhadeff,A.L.; Castorena,C.M.; Huang,Y.; Lieu,L.; Afrin,S.; Sun,J.; Betley,J.N.; Guo,H.; Williams,K.W. Cellular and synaptic reorganization of arcuate NPY/AgRP and POMC neurons after exercise. Mol Metab. 18, 107–119. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sergeyev V; Fetissov S; Mathé AA; Jimenez PA; Bartfai T; Mortas P; Gaudet L; Moreau JL; Hökfelt T. Neuropeptide expression in rats exposed to chronic mild stresses. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;178(2-3):115-24. [CrossRef]

- J H Urban; A C Bauer-Dantoin; J E Levine; Neuropeptide Y gene expression in the arcuate nucleus:sexual dimorphism; modulation by testosterone; Endocrinology; 132; Issue 1:139–145. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Rebouças EC; Leal S; Sá SI. Regulation of NPY; α-MSH expression by estradiol in the arcuate nucleus of Wistar female rats:a stereological study. Neurol Res. 2016;38(8):740-7. [CrossRef]

- Lindblom J; Haitina T; Fredriksson R; Schiöth HB. Differential regulation of nuclear receptors; neuropeptides; peptide hormones in the hypothalamus; pituitary of food restricted rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;133(1):37-46. [CrossRef]

- Levay EA; Tammer AH; Penman J; Kent S; Paolini AG. Nutr Res. 2010;30(5):366-73. [CrossRef]

- Chen C; Nakagawa S; An Y; Ito K; Kitaichi Y; Kusumi I. The exercise-glucocorticoid paradox:How exercise is beneficial to cognition; mood; the brain while increasing glucocorticoid levels. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017;44:83-102. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo P; Lazcano I; Jaimes-Hoy L; Gutierrez-Mariscal M; Sanchez-Jaramillo E; Uribe RM; Charli JL. Sexually dimorphic dynamics of thyroid axis activity during fasting in rats. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2020;25(7):1305-1323. [CrossRef]

- van Haasteren GA; Linkels E; van Toor H; Klootwijk W; Kaptein E; de Jong FH; Reymond MJ; Visser TJ; de Greef WJ. Effects of long-term food reduction on the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis in male; female rats. J Endocrinol. 1996;150(2):169-78. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S; Su Z; Wen X. Associationof T3/T4 ratio with inflammatory indicatorsand all-cause mortality in stroke survivors. Front Endocrinol. 2025;15:1509501. [CrossRef]

- Araujo RL; Andrade BM; da Silva ML; Ferreira AC; Carvalho DP. Tissue-specific deiodinase regulation during food restriction; low replacement dose of leptin in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E1157–E1163. [CrossRef]

- Weitzel JM; Iwen KA. Coordination of mitochondrial biogenesis by thyroid hormone. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;342(1-2):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Nappi A; Moriello C; Morgante M; Fusco F; Crocetto F; Miro C. Effects of thyroid hormones in skeletal muscle protein turnover. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2024;35(4-5):253-264. [CrossRef]

- Toyoda N; Yasuzawa-Amano S; Nomura E; Yamauchi A; Nishimura K; Ukita C; Morimoto S; Kosaki A; Iwasaka T; Harney JW; Larsen PR; Nishikawa M. Thyroid hormone activation in vascular smooth muscle cells is negatively regulated by glucocorticoid. Thyroid. 2009;19(7):755-63. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-deMena R; Anedda A; Cadenas S; Obregon MJ. TSH effects on thermogenesis in rat brown adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;404:151-8. [CrossRef]

- Masami Murakami; Yuji Kamiya; Tadashi Morimura; Osamu Araki; Makoto Imamura; Takayuki Ogiwara; Haruo Mizuma; Masatomo Mori; Thyrotropin Receptors in Brown Adipose Tissue:Thyrotropin Stimulates Type II Iodothyronine Deiodinase; Uncoupling Protein-1 in Brown Adipocytes; Endocrinology; 142(3):1195–1201. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sun,C.; Mao; S.; Chen,S.; Zhang; W.; Liu,C.PPARs-Orchestrated Metabolic Homeostasis in the Adipose Tissue. Int J Mol Sci. 8974;22 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tsiloulis T; Watt MJ. Exercise; the Regulation of Adipose Tissue Metabolism. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;135:175-201. [CrossRef]

- Granneman JG; Lahners KN. Regulation of mouse beta 3-adrenergic receptor gene expression; mRNA splice variants in adipocytes. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(4 Pt 1):C1040-4. [CrossRef]

- Fève B; Baude B; Krief S; Strosberg AD; Pairault J; Emorine LJ. dexamethasone down-regulates β3-adrenergic receptors in 3T3-F442A adipocytes. J Biol Chem 267(22):15909–15915. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Valle A; García-Palmer FJ; Oliver J; Roca P. Sex differences in brown adipose tissue thermogenic features during caloric restriction. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;19(1-4):195-204. [CrossRef]

- Jeremic N, Chaturvedi P, Tyagi SC. Browning of White Fat:Novel Insight Into Factors, Mechanisms, and Therapeutics. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(1):61-8. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Sumuano JT; Velez-delValle C; Beltrán-Langarica A; Marsch-Moreno M; Hernandez-Mosqueira C; Kuri-Harcuch W. Glucocorticoid paradoxically recruits adipose progenitors; impairs lipid homeostasis; glucose transport in mature adipocytes. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2573. [CrossRef]

- Laurens C; de Glisezinski I; Larrouy D; Harant I; Moro C. Influence of Acute; Chronic Exercise on Abdominal Fat Lipolysis:An Update. Front Physiol. 2020;11:575363. [CrossRef]

- Balagova,L.; Graban,J.; Puhova,A.; Jezova,D. Opposite Effects of Voluntary Physical Exercise on β3-Adrenergic Receptors in the White and Brown Adipose Tissue. Horm Metab Res. 2019;51(9):608-617. [CrossRef]

- Lehnig AC; Stanford KI. Exercise-induced adaptations to white; brown adipose tissue. J Exp Biol. 2018;221(Pt Suppl 1):jeb161570. [CrossRef]

- Slavin BG; Ong JM; Kern PA. Hormonal regulation of hormone-sensitive lipase activity; mRNA levels in isolated rat adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 1994;35(9):1535-41.

- Narita T; Kobayashi M; Itakura K; Itagawa R; Kabaya R; Sudo Y; Okita N; Higami Y. Differential response to caloric restriction of retroperitoneal; epididymal; subcutaneous adipose tissue depots in rats. Exp Gerontol. 2018;104:127-137. [CrossRef]

- Walczak,K.; Sieminska; LObesity; Thyroid Axis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9434. [CrossRef]

- Dewal RS; Stanford KI. Effects of exercise on brown; beige adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864(1):71-78. [CrossRef]

- Bakopanos E; Silva JE. Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on beta(3)-adrenergic receptor expression in HIB-1B brown adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;190(1-2):29-37. [CrossRef]

- Vargas Y; Castro Tron AE; Rodríguez Rodríguez A; Uribe RM; Joseph-Bravo P; Charli JL. Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone; Food Intake in Mammals:An Update. Metabolites. 2024;4(6):302. [CrossRef]

- Yan Su; Ewout Foppen; Eric Fliers; Andries Kalsbeek; Effects of Intracerebroventricular Administration of Neuropeptide Y on Metabolic Gene Expression; Energy Metabolism in Male Rats; Endocrinology; Volume 157(8):3070–3085. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Martelli,D.; Brooks; V.L.Leptin Increases:Physiological Roles in the Control of Sympathetic Nerve Activity; Energy Balance; the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Thyroid Axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24, 2684. [CrossRef]

- Dearing,C.; Handa,R.J.; Myers,B. Sex differences in autonomic responses to stress:implications for cardiometabolic physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2022;323(3):E281-E289. [CrossRef]

- Tanner MK; Mellert SM; Fallon IP; Baratta MV; Greenwood BN. Multiple Sex-; Circuit-Specific Mechanisms Underlie Exercise-Induced Stress Resistance. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2024;67:37-60. [CrossRef]

- Russell VA; Zigmond MJ; Dimatelis JJ; Daniels WM; Mabandla MV. The interaction between stress; exercise; its impact on brain function. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;29(2):255-60. [CrossRef]

- Bourke CH; Neigh GN. Behavioral effects of chronic adolescent stress are sustained; sexually dimorphic. Horm Behav. 2011;60(1):112-20. [CrossRef]

- Vieira IH; Rodrigues D; Paiva I. The Mysterious Universe of the TSH Receptor. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13:944715. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira-Cordero A; Salas-Bastos A; Fornaguera J; Brenes JC. Behavioural characterisation of chronic unpredictable stress based on ethologically relevant paradigms in rats. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):17403. [CrossRef]

- Nair BB; Khant Aung Z; Porteous R; Prescott M; Glendining KA; Jenkins DE; Augustine RA; Silva MSB; Yip SH; Bouwer GT; Brown CH; Jasoni CL; Campbell RE; Bunn SJ; Anderson GM; Grattan DR; Herbison AE; Iremonger KJ. Impact of chronic variable stress on neuroendocrine hypothalamus; pituitary in male; female C57BL/6J mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2021;33(5):e12972. [CrossRef]

- Guo TY; Liu LJ; Xu LZ; Zhang JC; Li SX; Chen C; He LG; Chen YM; Yang HD; Lu L; Hashimoto K. Alterations of the daily rhythms of HPT axis induced by chronic unpredicted mild stress in rats. Endocrine. 2015;48(2):637-43. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J; Huang J; Aximujiang K; Xu C; Ahemaiti A; Wu G; Zhong L; Yunusi K. Thyroid Dysfunction; Neurological Disorder; Immunosuppression as the Consequences of Long-term Combined Stress. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4552. [CrossRef]

- Yesmin R; Watanabe M; Sinha AS; Ishibashi M; Wang T; Fukuda A. A subpopulation of agouti-related peptide neurons exciting corticotropin-releasing hormone axon terminals in median eminence led to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation in response to food restriction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15:990803. [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Bravo,P.; Gutiérrez-Mariscal,M.; Jaimes-Hoy,L.; Charli; JL. Thyroid Axis and Energy Balance:Focus on Animals and Implications for Humankind. In:Preedy, V., Patel, V. 2017;(eds) Handbook of Famine, Starvation, and Nutrient Deprivation. Springer, Cham.

- Coppola A; Meli R; Diano S. Inverse shift in circulating corticosterone; leptin levels elevates hypothalamic deiodinase type 2 in fasted rats. Endocrinology. 146(6):2827-33. [CrossRef]

- Wray JR; Davies A; Sefton C; Allen TJ; Adamson A; Chapman P; Lam BYH; Yeo GSH; Coll AP; Harno E; White A. Global transcriptomic analysis of the arcuate nucleus following chronic glucocorticoid treatment. Mol Metab. 2019;26:5-17. [CrossRef]

- Benvenga S; Di Bari F; Granese R; Borrielli I; Giorgianni G; Grasso L; Le Donne M; Vita R; Antonelli A. Circulating thyrotropin is upregulated by estradiol. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2018;11:11-17. [CrossRef]

- Ha GE; Cheong E. Chronic Restraint Stress Decreases the Excitability of Hypothalamic POMC Neuron; Increases Food Intake. Exp Neurobiol. 30(6):375-386. [CrossRef]

- Stranahan,A.M.; Lee,K.; Mattson,M.P. Central mechanisms of HPA axis regulation by voluntary exercise. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10, 118–227. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J; Kim H.J.; Lee W.J.; Seong J.K. A comparison of the metabolic effects of treadmill and wheel running exercise in mouse model. Lab Anim Res. 2020;36:3. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Valles A; Sánchez E; de Gortari P; García-Vazquez AI; Ramírez-Amaya V; Bermúdez-Rattoni F; Joseph-Bravo P. The expression of TRH; its receptors; degrading enzyme is differentially modulated in the rat limbic system during training in the Morris water maze. Neurochem Int. 2007;50(2):404-17. [CrossRef]

- Bianco AC, Dumitrescu A, Gereben B, Ribeiro MO, Fonseca TL, Fernandes GW, Bocco BMLC. Paradigms of Dynamic Control of Thyroid Hormone Signaling. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(4):1000-1047. [CrossRef]

- Giacco A; Cioffi F; Cuomo A; Simiele R; Senese R; Silvestri E; Amoresano A; Fontanarosa C; Petito G; Moreno M; Lanni A; Lombardi A; de Lange P. Mild Endurance Exercise during Fasting Increases Gastrocnemius Muscle; Prefrontal Cortex Thyroid Hormone Levels through Differential BHB; BCAA-Mediated BDNF-mTOR Signaling in Rats. Nutrients. 2022;14(6):1166. [CrossRef]

- Shen,S.; Liao,Q.; Liu,J.; Pan,R.; Lee,S.M.; Lin,L. Myricanol rescues dexamethasone-induced muscle dysfunction via a sirtuin 1-dependent mechanism. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10, 429–444. [CrossRef]

- Haque,N.; Tischkau; S.A.Sexual Dimorphism inAdipose-Hypothalamic Crosstalkand the Contribution of ArylHydrocarbon Receptor to RegulateEnergy Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23, 7679. [CrossRef]

- Vidal P; Stanford KI. Exercise-Induced Adaptations to Adipose Tissue Thermogenesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:270. [CrossRef]

- Münzberg H; Singh P; Heymsfield SB; Yu S; Morrison CD. Recent advances in understanding the role of leptin in energy homeostasis. F1000Res. 9:F1000 Faculty Rev-451. [CrossRef]

- Scheel AK, Espelage L, Chadt A. Many Ways to Rome:Exercise, Cold Exposure and Diet-Do They All Affect BAT Activation and WAT Browning in the Same Manner? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4759. [CrossRef]

- Recazens E, Mouisel E, Langin D. Hormone-sensitive lipase:sixty years later. Prog Lipid Res. 2021;82:101084. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Wang Y, Liu L, Lutfy K, Friedman TC, Liu Y, Jiang M, Liu Y. Lack of adipose-specific hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase causes inactivation of adipose glucocorticoids and improves metabolic phenotype in mice. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019;133(21):2189-2202. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Seong JK. AMP-activated protein kinase activation in skeletal muscle modulates exercise-induced uncoupled protein 1 expression in brown adipocyte in mouse model. J Physiol. 2022;600(10):2359-2376. [CrossRef]

- Hellstrom IC, Dhir SK, Diorio JC, Meaney MJ. Maternal licking regulates hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor transcription through a thyroid hormone-serotonin-NGFI-A signalling cascade. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1601):2495-510. [CrossRef]

- Louzada RA, Santos MC, Cavalcanti-de-Albuquerque JP, Rangel IF, Ferreira AC, Galina A, Werneck-de-Castro JP, Carvalho DP. Type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is upregulated in rat slow- and fast-twitch skeletal muscle during cold exposure. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307(11):E1020-9. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez A, St Germain DL. Dexamethasone inhibits growth factor-induced type 3 deiodinase activity and mRNA expression in a cultured cell line derived from rat neonatal brown fat vascular-stromal cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143(7):2652-8. [CrossRef]

- de Vries EM, van Beeren HC, van Wijk ACWA, Kalsbeek A, Romijn JA, Fliers E, Boelen A. Regulation of type 3 deiodinase in rodent liver and adipose tissue during fasting. Endocr Connect. 2020;9(6):552-562. [CrossRef]

- Ayyar VS, Almon RR, DuBois DC, Sukumaran S, Qu J, Jusko WJ. Functional proteomic analysis of corticosteroid pharmacodynamics in rat liver:Relationship to hepatic stress, signaling, energy regulation, and drug metabolism. J Proteomics. 2017;160:84-105. [CrossRef]

- Mason J, Southwick S, Yehuda R, Wang S, Riney S, Bremner D, et al. Elevation of serum free triiodothyronine, total triiodothyronine, thyroxine-binding globulin, and total thyroxine levels in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1994) 51(8):629–41. [CrossRef]

- Raise-Abdullahi P, Meamar M, Vafaei AA, Alizadeh M, Dadkhah M, Shafia S, Ghalandari-Shamami M, Naderian R, Afshin Samaei S, Rashidy-Pour A. Hypothalamus and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder:A Review. Brain Sci.; 13(7):1010. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich JW, Hoermann R, Midgley JEM, Bergen F, Müller P. The Two Faces of Janus:Why Thyrotropin as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor May Be an Ambiguous Target. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:542710. [CrossRef]

- Sotelo-Rivera I, Cote-Vélez A, Uribe RM, Charli JL, Joseph-Bravo P. Glucocorticoids curtail stimuli-induced CREB phosphorylation in TRH neurons through interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A. Endocrine. 2017;55(3):861-871. [CrossRef]

- Osterlund C, Spencer RL. Corticosterone pretreatment suppresses stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity via multiple actions that vary with time, site of action, and de novo protein synthesis. J Endocrinol. 2011 ; 208(3):311-22. [CrossRef]

- Jaszczyk A, Juszczak GR. Glucocorticoids, metabolism and brain activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;126:113-145. [CrossRef]

- Fallon IP, Tanner MK, Greenwood BN, Baratta MV. Sex differences in resilience:Experiential factors and their mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2020;52(1):2530-2547. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).