Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The variable N-terminal A/B domain, which contains the activation function-1 (AF-1) region and mediates interactions with coactivators and corepressors to modulate transcriptional activity.

- The highly conserved central C domain, housing the DNA-binding domain (DBD) that enables NRs to regulate gene expression by binding promoter sequences as homo-/heterodimers or monomers.

- The flexible hinge D domain, which connects the DBD to the ligand-binding domain (LBD) and facilitates LBD rotation for transcriptional responses; it also contains a nuclear localisation signal (NLS) for nuclear import.

2. General Characteristics of NR4A Subfamily

3. NR4A Receptors in Myeloid Cells

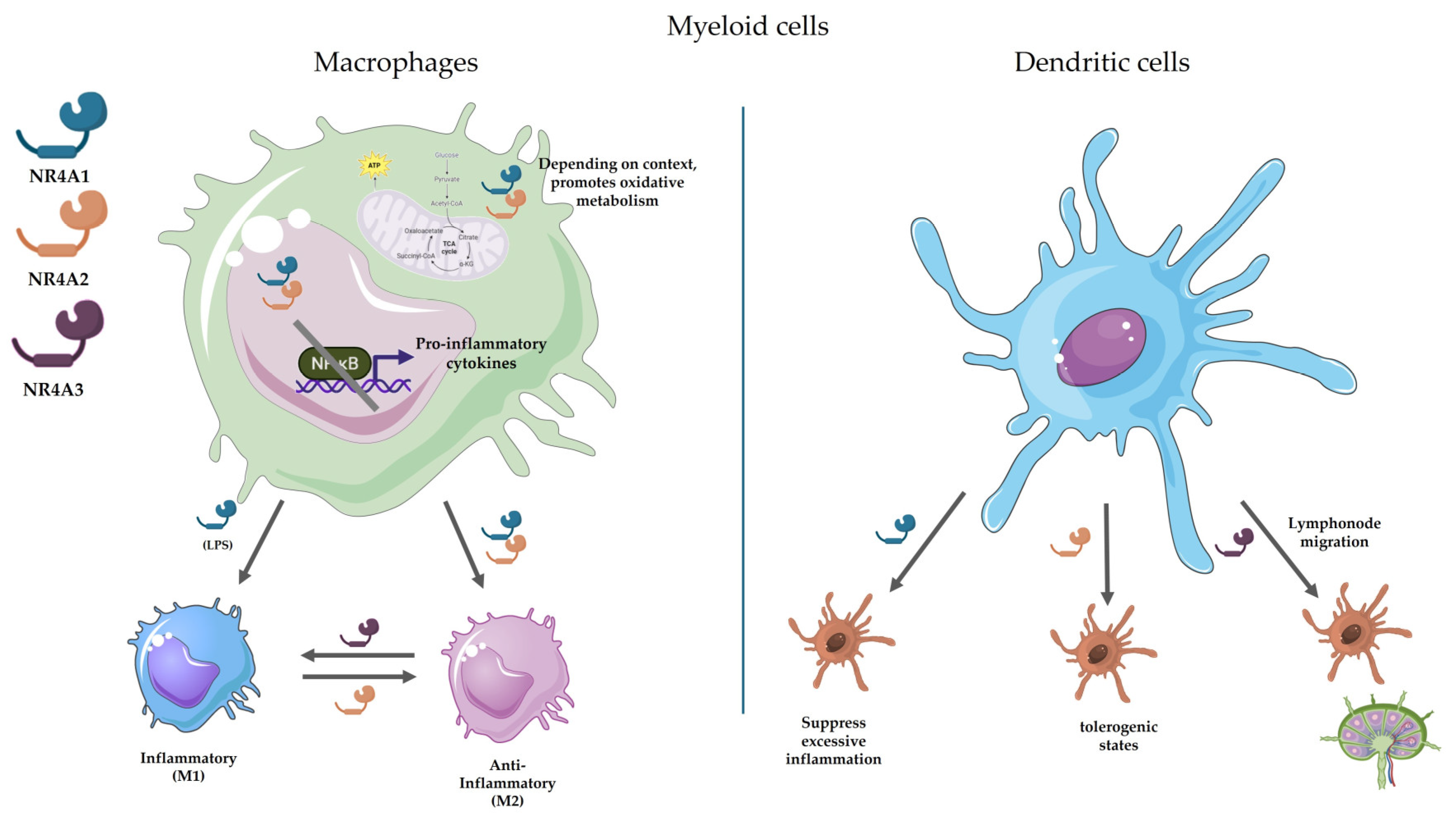

3.1. Macrophages

- NR4A1 plays complex roles in macrophage biology, upregulating genes involved in inflammation, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation. In the context of immune response, while it generally suppresses NF-κB activity and limits inflammatory cytokine production, its effects on the high inflammatory cytokine Tumoral Necrotic Factor α (TNF-α), appear distinct - neither expression nor secretion of this cytokine is altered in NR4A1-deficient macrophages, This exception may relate to succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity, which exerts independent anti-inflammatory effects [37]. NR4A1 deficiency leads to enhanced NF-κB activation, evidenced by increased p65 phosphorylation, and promotes a pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype [10].

- NR4A2 was first linked to NF-κB regulation through studies in TLR4-stimulated microglia, where its depletion exacerbated pro-inflammatory responses. Upon TLR4 activation, NR4A2 undergoes SUMOylation and phosphorylation, enabling it to bind phosphorylated NF-κB/p65 at target gene promoters. This interaction recruits the Co-REST repressor complex, displacing NF-κB/p65 and suppressing pro-inflammatory gene expression [10,42].

- In macrophages, NR4A2 expression is induced through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway, which attenuates innate inflammatory responses. NR4A2 promotes M2 polarisation and protects against endotoxin-induced sepsis, suggesting it functions as an inflammatory brake [43]. Interestingly, in autoimmune conditions like bullous pemphigoid, pro-inflammatory macrophages show elevated NR4A2 levels, possibly representing a compensatory mechanism to restrain inflammation [44].

- NR4A3 demonstrates distinct functions in macrophage biology. Silencing NOR1 in human IL-4-polarized macrophages downregulates alternative activation markers (Mannose Receptor, IL-1Ra, CD200R, F13A1, IL-10, PPARγ) while increasing MMP9 expression and activity - typically associated with M1 phenotypes [45]. In atherosclerosis, NR4A3 promotes early disease events by enhancing monocyte adhesion to endothelium. Inflammatory signals like NF-κB activate NR4A3, which induces expression of adhesion molecules (either directly on monocytes or indirectly via endothelial VCAM-1/ICAM-1 upregulation), facilitating immune cell recruitment to vascular walls [46].

3.2. Dendritic Cells

- NR4A1 serves as a critical immunoregulator in DCs. Expressed across human and murine DC subsets, its expression rapidly increases upon TLR stimulation. NR4A1-deficient DCs display hyperinflammatory responses with enhanced NF-κB-dependent cytokine production (IL-6, TNFα, IL-12) and increased T-cell stimulatory capacity [41,48]. Conversely, pharmacological activation of NR4A1 suppresses cytokine and attenuates DC-driven allogeneic T-cell proliferation. positioning it as a key checkpoint against excessive immune activation [48].

- NR4A2, while less abundantly expressed in DCs than other family members [17], plays a specialised role in immune tolerance. Saini et al. demonstrated that NR4A2 drives a regulatory phenotype in bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs), suppressing autoimmune neuroinflammation through Treg expansion. These findings suggest NR4A2 can reprogram immunogenic DCs toward tolerogenic states [49].

- NR4A3 shows preferential expression in migratory DCs and in essential for their lymph node homing. NR4A3-deficient DCs exhibit reduced CCR7 expression - the key chemokine receptor for DC migration - both at steady-state and upon activation [47,50]. While NR4A3 doesn’t directly bind the CCR7 promoter, it may regulate migration indirectly through transcription factors like FOXO1 or broader migratory programs [17,50].

4. NR4A Receptors in Lymphoid Cells

4.1. T Cells

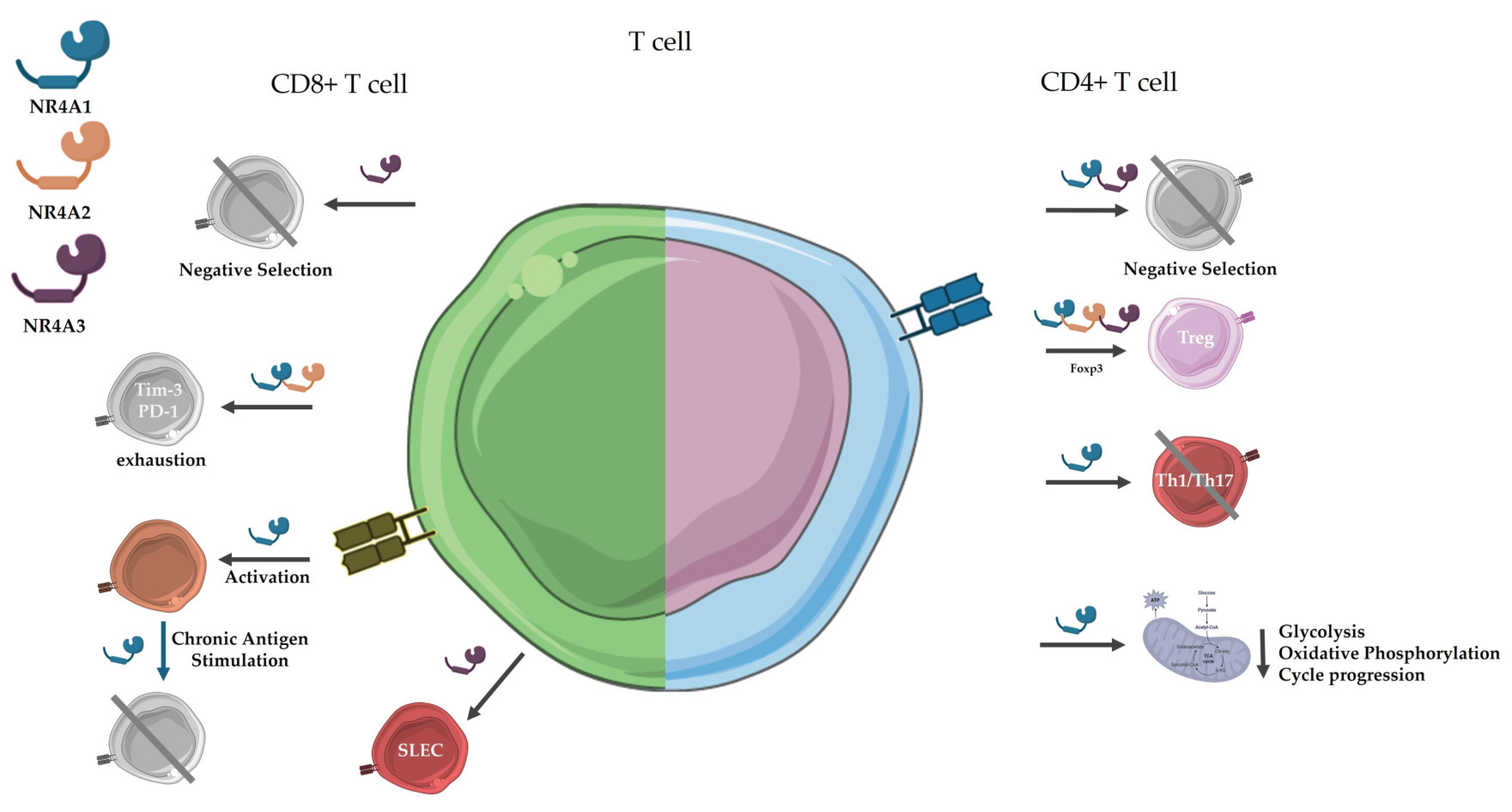

4.1.1. CD4+ T Cells

- CD4+ T cells are the master regulators of adaptive immunity, coordinating immune responses against pathogens and cancer by directing the activity of B cells, macrophages, and CD8+ T cells. Upon recognizing antigen via MHC class II on dendritic cells, naïve CD4+ T cells proliferate and differentiate into specialized subsets dictated by the inflammatory environment: Th1 (IFN-γ producers that activate macrophages and CD8+ T cells), Th2 (IL-4-secreting helpers for B cell class-switching to IgE), Th17 (IL-17-dependent recruiters of neutrophils), Tfh (follicular helpers for B cell germinal center responses), and Tregs (suppressors of autoimmunity). Post-infection, most effector CD4+ T cells undergo apoptosis, but a subset persists as long-lived memory cells—mirroring the CD8+ T cell response [28]. Regarding the diverse repertoire of different populations of T cells, NR4A family is among the few factors directly implicated in thymic selection, orchestrating thymic deletion and Treg diversion, establishing a cell-intrinsic tolerance program upon self-antigen recognition. This process likely serves as a critical fail-safe against autoimmunity [56].

- NR4A1 serves as a master regulator of CD4+ T cells. While expressed at low levels In naïve cells, it rapidly induces upon antigen engagement [28]. suppresses effector T cell responses by inhibiting Th1/Th17 differentiation and cytokine production (IFN-γ, IL-17) while promoting Treg development and function [57]. Mechanistically, NR4A1 competes with AP-1 transcription factors at shared DNA binding sites, directly repressing IL-2 transcript [58]. It also modulates T cell metabolism, with NR4A1 deficiency leading to enhanced glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation that fuels unchecked proliferation [59,60].

- NR4A2. While NR4A1 and NR4A3 serve as primary regulators of Treg biology, NR4A2 exhibits unique and context-dependent functions in immune homeostasis. Unlike its family members, NR4A2 protein remains undetectable in stimulated thymocytes despite mRNA expression, suggesting divergent regulatory mechanisms during thymic selection [66]. In mature CD4+ T cells, NR4A2 demonstrates partial functional redundancy with other NR4As, as evidenced by only modest reductions in Foxp3 and CD25 expression in NR4A2 single-knockout models [63]. However, its specific capacity to suppress IL-4 promoter activity in reporter assays [26] and maintain Treg identity through conserved Foxp3 enhancer elements (CNS1/2) [67,68,69] indicates specialised roles in peripheral immune regulation.

- NR4A3 plays dual yet distinct roles in thymocyte development and Treg differentiation. During thymic selection, NR4A3 functions redundantly with NR4A1 to enforce central tolerance, particularly in mediating negative selection of self-reactive thymocytes [62]. Both nuclear receptors trigger apoptosis through a shared mitochondrial pathway - following nuclear export, they bind and convert anti-apoptotic BCL-2 into a pro-apoptotic form by exposing its BH3 domain [28]. This non-transcriptional mechanism complements their transcriptional regulation of apoptotic genes, providing a fail-safe for eliminating autoreactive clones.

4.1.2. CD8+ T Cells

- NR4A1 orchestrates CD8+ T cell responses through stage-specific functions. During initial T cell receptor (TCR) activation, NR4A1 expression peaks rapidly (1-3 hours post-stimulation), with single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrating its transcription levels directly correlate with TCR signal strength [76]. This immediate-early response supports initial T cell activation while simultaneously establishing regulatory checkpoints. Under conditions of chronic antigen exposure, NR4A1 undergoes functional switching - upregulating the pro-apoptotic factor BIM to trigger mitochondrial apoptosis of overactivated clones, thereby preventing immunopathology [28]. This dual role as both activation promoter and termination signal is evidenced in NR4A1-deficient models, which exhibit enhanced antitumor activity but also dysregulated T cell expansion [12,59].

- NR4A2. As well as NR4A1, NR4A2 participates in CD8+ T cell exhaustion. A recent work of Srirat et al. demonstrated that genetic deletion of NR4A2 in CD8+ T cells reduced tumour size, with the double-knockout in NR4A1/2 showing a strong antitumoral response [82].

- NR4A3. While NR4A1 and NR4A3 share overlapping expression patterns, accumulating evidence reveals their distinct functional roles in T cell biology. NR4A3 serves as a specific marker for thymocytes receiving strong TCR signals during negative selection, with NR4A3 deficiency impairing the deletion of autoreactive clones [55]. Their differential expression patterns further highlight this functional divergence - NR4A1 responds to both positive and negative selection signals (albeit more strongly to the latter), while NR4A3 induction occurs exclusively in response to high-affinity TCR engagement [28]. These findings fundamentally challenge the concept of complete redundancy between these nuclear receptor family members.

4.2. B Cells

- NR4A1. During the GC response, B cell clones compete for entry and dominance, with selection typically favouring those expressing high-affinity B cell receptors (BCRs). However, GCs are not exclusively dominated by high-affinity clones; they can sustain a heterogeneous population, including low-affinity B cells, over extended periods. This suggests the presence of regulatory mechanisms that prevent early monopolization by dominant clones. Recent studies highlight the orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1 as a key negative regulator in this process. Upon BCR-antigen engagement, NR4A1 is rapidly induced, forming a negative feedback loop that curbs B cell proliferation and restricts the early expansion of high-affinity clones [83].

4.3. NKT Cell

5. NR4A Receptors in Pathology

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volle, D.H. Nuclear receptors in physiology and pathophysiology. Mol. Asp. Med. 2021, 78, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P. Nuclear Receptors in Health and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, R.; Glass, C.K. Signaling by Nuclear Receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a016709–a016709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volle, D.H. Nuclear receptors as pharmacological targets, where are we now? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3777–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, M.; Czimmerer, Z.; Nagy, L. The role of lipid-activated nuclear receptors in shaping macrophage and dendritic cell function: From physiology to pathology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Pineda-Torra, I.; Venteclef, N. Editorial: Nuclear Receptors and Coregulators in Metabolism and Immunity. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 828635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbrandt, J. Nerve growth factor induces a gene homologous to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Neuron 1988, 1, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law SW, Conneely OM, DeMayo FJ, O’Malley BW (1992) Identification of a new brain-specific transcription factor, NURR1. Molecular Endocrinology 6:2129–2135. [CrossRef]

- Ohkura, N.; Hijikuro, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Miki, K. Molecular Cloning of a Novel Thyroid/Steroid Receptor Superfamily Gene from Cultured Rat Neuronal Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 205, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.P.; Crean, D. Molecular Interactions between NR4A Orphan Nuclear Receptors and NF-κB Are Required for Appropriate Inflammatory Responses and Immune Cell Homeostasis. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1302–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranhotra, H.S. The NR4A orphan nuclear receptors: mediators in metabolism and diseases. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. 2014, 35, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring JA, Elison WS, Tessem JS (2019) Function of nr4a orphan nuclear receptors in proliferation, apoptosis and fuel utilization across tissues. Cells 8. [CrossRef]

- Crean D, Murphy EP (2021) Targeting NR4A Nuclear Receptors to Control Stromal Cell Inflammation, Metabolism, Angiogenesis, and Tumorigenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, He Y, Kamenecka TM, Kojetin DJ (2025) Towards a unified molecular mechanism for liganddependent activation of NR4A-RXR heterodimers. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- de Vera, I.M.S.; Munoz-Tello, P.; Zheng, J.; Dharmarajan, V.; Marciano, D.P.; Matta-Camacho, E.; Giri, P.K.; Shang, J.; Hughes, T.S.; Rance, M.; et al. Defining a Canonical Ligand-Binding Pocket in the Orphan Nuclear Receptor Nurr1. Structure 2019, 27, 66–77.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe, S.; Karki, K. The Paradoxical Roles of Orphan Nuclear Receptor 4A (NR4A) in Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 19, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, S.; Le Corre, L.; Odagiu, L.; Labrecque, N. Role of NR4A family members in myeloid cells and leukemia. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2022, 3, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurakula, K.; Koenis, D.S.; van Tiel, C.M.; de Vries, C.J. NR4A nuclear receptors are orphans but not lonesome. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2543–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zárraga-Granados, G.; Muciño-Hernández, G.; Sánchez-Carbente, M.R.; Villamizar-Gálvez, W.; Peñas-Rincón, A.; Arredondo, C.; Andrés, M.E.; Wood, C.; Covarrubias, L.; Castro-Obregón, S.; et al. The nuclear receptor NR4A1 is regulated by SUMO modification to induce autophagic cell death. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0222072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorrow JP, Murphy EP (2011) Inflammation: A role for NR4A orphan nuclear receptors? Biochem Soc Trans 39:688–693.

- Munoz-Tello, P.; Lin, H.; Khan, P.; de Vera, I.M.S.; Kamenecka, T.M.; Kojetin, D.J. Assessment of NR4A Ligands That Directly Bind and Modulate the Orphan Nuclear Receptor Nurr1. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 15639–15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-G.; Smith, S.W.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Schwartz, L.M.; Osborne, B.A. Apoptotic signals delivered through the T-cell receptor of a T-cell hybrid require the immediate–early gene nur77. Nature 1994, 367, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woronicz, J.D.; Calnan, B.; Ngo, V.; Winoto, A. Requirement for the orphan steroid receptor Nur77 in apoptosis of T-cell hybridomas. Nature 1994, 367, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwa, R.; Brooks, J.F.; Mueller, J.L.; Nielsen, H.V.; Zikherman, J. NR4A nuclear receptors in T and B lymphocytes: Gatekeepers of immune tolerance*. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 307, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, T.; Kashiwagi, I.; Yoshida, R.; Fukaya, T.; Morita, R.; Kimura, A.; Ichinose, H.; Metzger, D.; Chambon, P.; Yoshimura, A. Nr4a receptors are essential for thymic regulatory T cell development and immune homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta, P.I.; van Tiel, C.M.; Vos, M.; Pols, T.W.; van Thienen, J.V.; Ferreira, V.; Arkenbout, E.K.; Seppen, J.; Spek, C.A.; van der Poll, T.; et al. Nuclear Receptors Nur77, Nurr1, and NOR-1 Expressed in Atherosclerotic Lesion Macrophages Reduce Lipid Loading and Inflammatory Responses. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2288–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeanneteau, F.; Barrère, C.; Vos, M.; De Vries, C.J.; Rouillard, C.; Levesque, D.; Dromard, Y.; Moisan, M.-P.; Duric, V.; Franklin, T.C.; et al. The Stress-Induced Transcription Factor NR4A1 Adjusts Mitochondrial Function and Synapse Number in Prefrontal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 1335–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odagiu, L.; May, J.; Boulet, S.; Baldwin, T.A.; Labrecque, N. Role of the Orphan Nuclear Receptor NR4A Family in T-Cell Biology. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveney, B.J.E.; Oki, S.; Yamamura, T.; Stangel, M. Nuclear Receptor NR4A2 Orchestrates Th17 Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Inflammation via IL-21 Signalling. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e56595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, S.; Chikuma, S.; Kondo, T.; Ito, M.; Nakatsukasa, H.; Omata-Mise, S.; Yoshimura, A. Inhibition of Nr4a Receptors Enhances Antitumor Immunity by Breaking Treg-Mediated Immune Tolerance. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 3027–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandukwala, H.S.; Rao, A. 'Nurr'ishing Treg cells: Nr4a transcription factors control Foxp3 expression. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G.-X.; Xu, Y.-M. Nr4a1 plays a crucial modulatory role in Th1/Th17 cell responses and CNS autoimmunity. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2018, 68, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Chen, J.; González-Avalos, E.; Samaniego-Castruita, D.; Das, A.; Wang, Y.H.; López-Moyado, I.F.; Georges, R.O.; Zhang, W.; Onodera, A.; et al. TOX and TOX2 transcription factors cooperate with NR4A transcription factors to impose CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12410–12415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, T.; Kashiwagi, I.; Yoshida, R.; Fukaya, T.; Morita, R.; Kimura, A.; Ichinose, H.; Metzger, D.; Chambon, P.; Yoshimura, A. Nr4a receptors are essential for thymic regulatory T cell development and immune homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Mueller, J.L.; Noviski, M.; Huizar, J.; Lau, D.; Dubinin, A.; Molofsky, A.; Wilson, P.C.; Zikherman, J. Nur77 Links Chronic Antigen Stimulation to B Cell Tolerance by Restricting the Survival of Self-Reactive B Cells in the Periphery. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 2907–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, S.; Le Corre, L.; Odagiu, L.; Labrecque, N. Role of NR4A family members in myeloid cells and leukemia. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2022, 3, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenis, D.S.; Medzikovic, L.; van Loenen, P.B.; van Weeghel, M.; Huveneers, S.; Vos, M.; Gogh, I.J.E.-V.; Bossche, J.V.D.; Speijer, D.; Kim, Y.; et al. Nuclear Receptor Nur77 Limits the Macrophage Inflammatory Response through Transcriptional Reprogramming of Mitochondrial Metabolism. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 2127–2140.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan DG, O’Neill LAJ (2017) Krebs cycle rewired for macrophage and dendritic cell effector functions. FEBS Lett 591:2992–3006. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.-Z.; Li, F.-W.; Wu, J.-F.; Zhang, H.-K.; He, J.-P.; Xing, Y.-Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.-J.; et al. Impeding the interaction between Nur77 and p38 reduces LPS-induced inflammation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, R.N.; Shaked, I.; Hubbeling, H.G.; Punt, J.A.; Wu, R.; Herrley, E.; Zaugg, C.; Pei, H.; Geissmann, F.; Ley, K.; et al. NR4A1 (Nur77) Deletion Polarizes Macrophages Toward an Inflammatory Phenotype and Increases Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.P.; Crean, D. NR4A1-3 nuclear receptor activity and immune cell dysregulation in rheumatic diseases. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 874182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saijo, K.; Winner, B.; Carson, C.T.; Collier, J.G.; Boyer, L.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Gage, F.H.; Glass, C.K. A Nurr1/CoREST Pathway in Microglia and Astrocytes Protects Dopaminergic Neurons from Inflammation-Induced Death. Cell 2009, 137, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Saini, A.; Chandra, V.; Nanduri, R.; Kalra, R.; Bhagyaraj, E.; Khatri, N.; Gupta, P. Nuclear Receptor Nr4a2 Promotes Alternative Polarization of Macrophages and Confers Protection in Sepsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18304–18314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Solís-Barbosa, M.; Santana, E.; Muñoz-Torres, J.R.; Segovia-Gamboa, N.C.; Patiño-Martínez, E.; A Meraz-Ríos, M.; Samaniego, R.; Sánchez-Mateos, P.; Sánchez-Torres, C. The nuclear receptor Nurr1 is preferentially expressed in human pro-inflammatory macrophages and limits their inflammatory profile. Int. Immunol. 2023, 36, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, F.; Eeckhoute, J.; Copin, C.; Vanhoutte, J.; Duhem, C.; Derudas, B.; Dubois-Chevalier, J.; Colin, S.; Zawadzki, C.; Jude, B.; et al. The neuron-derived orphan receptor 1 (NOR1) is induced upon human alternative macrophage polarization and stimulates the expression of markers of the M2 phenotype. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Howatt, D.A.; Gizard, F.; Nomiyama, T.; Findeisen, H.M.; Heywood, E.B.; Jones, K.L.; Conneely, O.M.; Daugherty, A.; Bruemmer, D. Deficiency of the NR4A Orphan Nuclear Receptor NOR1 Decreases Monocyte Adhesion and Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, S.; Daudelin, J.-F.; Odagiu, L.; Pelletier, A.-N.; Yun, T.J.; Lesage, S.; Cheong, C.; Labrecque, N. The orphan nuclear receptor NR4A3 controls the differentiation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells following microbial stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 15150–15159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tel-Karthaus, N.; Kers-Rebel, E.D.; Looman, M.W.; Ichinose, H.; de Vries, C.J.; Ansems, M. Nuclear Receptor Nur77 Deficiency Alters Dendritic Cell Function. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, A.; Mahajan, S.; Gupta, P. Nuclear receptor expression atlas in BMDCs: Nr4a2 restricts immunogenicity of BMDCs and impedes EAE. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Mikulski, Z.; Seo, G.-Y.; Andreyev, A.Y.; Marcovecchio, P.; Blatchley, A.; Kronenberg, M.; Hedrick, C.C. The transcription factor NR4A3 controls CD103+ dendritic cell migration. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 4603–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, M.; Yashiro, T.; Uchida, Y.; Ando, T.; Hara, M.; Arai, H.; Ogawa, H.; Okumura, K.; Kasakura, K.; Nishiyama, C. The Orphan Nuclear Receptor NR4A3 Is Involved in the Function of Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 2958–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejean, A.S.; Joulia, E.; Walzer, T. The role of Eomes in human CD4 T cell differentiation: A question of context. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018, 49, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino W, Mendes-Da-Cruz DA, Lepletier A, Dardenne M (2016) Hormonal control of T-cell development in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12:77–89.

- van Hamburg, J.P.; Tas, S.W. Molecular mechanisms underpinning T helper 17 cell heterogeneity and functions in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 87, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, S.; Odagiu, L.; Dong, M.; Lebel, M.; Daudelin, J.-F.; Melichar, H.J.; Labrecque, N. NR4A3 Mediates Thymic Negative Selection. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.V.; Yang, L.; Mueller, J.L.; Ritter, A.J.; Hiwa, R.; Proekt, I.; Rackaityte, E.; Aylard, D.; Gupta, M.; Scharer, C.D.; et al. Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 redundantly control clonal deletion and contribute to an anergy-like transcriptome in auto-reactive thymocytes to impose tolerance in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G.-X.; Xu, Y.-M. Nr4a1 plays a crucial modulatory role in Th1/Th17 cell responses and CNS autoimmunity. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2018, 68, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Yan, X.; Xiao, M.; Hao, J.; Alekseev, A.; Khong, H.; Chen, T.; et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies NR4A1 as a key mediator of T cell dysfunction. Nature 2019, 567, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii Y, Matsuda S, Takayama G, Koyasu S (2008) ERK5 is involved in TCR-induced apoptosis through the modification of Nur77. Genes to Cells 13:411–419. [CrossRef]

- Liebmann, M.; Hucke, S.; Koch, K.; Eschborn, M.; Ghelman, J.; Chasan, A.I.; Glander, S.; Schädlich, M.; Kuhlencord, M.; Daber, N.M.; et al. Nur77 serves as a molecular brake of the metabolic switch during T cell activation to restrict autoimmunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 201721049–E8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.E.; Holzapfel, K.L.; Xing, Y.; Cunningham, N.R.; Maltzman, J.S.; Punt, J.; Hogquist, K.A. T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwa, R.; Nielsen, H.V.; Mueller, J.L.; Mandla, R.; Zikherman, J. NR4A family members regulate T cell tolerance to preserve immune homeostasis and suppress autoimmunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, T.; Kondo, T.; Shichita, T.; Morita, R.; Ichinose, H.; Yoshimura, A. Suppression of Th2 and Tfh immune reactions by Nr4a receptors in mature T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, A.; Ito, M.; Mise-Omata, S.; Ando, M. SOCS: negative regulators of cytokine signaling for immune tolerance. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, J.F.; Weiss, A. Endogenous Nur77 Is a Specific Indicator of Antigen Receptor Signaling in Human T and B Cells. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bending, D.; Zikherman, J. Nr4a nuclear receptors: markers and modulators of antigen receptor signaling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2023, 81, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.-Y.; Jang, Y.; Kim, W.; Shin, J.; Toh, H.T.; Kim, C.-H.; Yoon, H.S.; Leblanc, P.; Kim, K.-S. Chloroquine modulates inflammatory autoimmune responses through Nurr1 in autoimmune diseases. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, H.Y.; Shin, J.H.; Oh, S.; Jeong, H.; Hwang, E.S. Enhanced CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development by amodiaquine through activation of nuclear receptor 4A. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16946–16946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa C, Tone Y, Tsuda M, et al. (2014) TGF-β–Mediated Foxp3 Gene Expression Is Cooperatively Regulated by Stat5, Creb, and AP-1 through CNS2. The Journal of Immunology 192:475–483. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Tsuboi, H.; Asashima, H.; Hirota, T.; Kondo, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Matsumoto, I.; Nakamura, S.; Sumida, T. cDNA microarray analysis identifies NR4A2 as a novel molecule involved in the pathogenesis of Sjögren's syndrome. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017, 190, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Zhong, X.; Wu, H.; Feng, M.; Gwack, Y.; Isakov, N.; Sun, Z. Steroid nuclear receptor coactivator 2 controls immune tolerance by promoting induced T reg differentiation via up-regulating Nr4a2. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bending, D.; Martín, P.P.; Paduraru, A.; Ducker, C.; Marzaganov, E.; Laviron, M.; Kitano, S.; Miyachi, H.; Crompton, T.; Ono, M. A timer for analyzing temporally dynamic changes in transcription during differentiation in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2931–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, E.; Elliot, T.A.; Thawait, N.; Kanabar, S.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; Ono, M.; Toellner, K.-M.; Wraith, D.C.; Anderson, G.; Bending, D. Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 Reporter Mice Are Differentially Sensitive to T Cell Receptor Signal Strength and Duration. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Browne, J.P.; López-Moyado, I.F.; Trifari, S.; Wong, V.; Chavez, L.; Rao, A.; Pereira, R.M. Dynamic Changes in Chromatin Accessibility Occur in CD8 + T Cells Responding to Viral Infection. Immunity 2016, 45, 1327–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurd, N.S.; He, Z.; Louis, T.L.; Milner, J.J.; Omilusik, K.D.; Jin, W.; Tsai, M.S.; Widjaja, C.E.; Kanbar, J.N.; Olvera, J.G.; et al. Early precursors and molecular determinants of tissue-resident memory CD8 + T lymphocytes revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odagiu L, Boulet S, de Sousa DM, et al. (2020) Early programming of CD8+ T cell response by the orphan nuclear receptor NR4A3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:24392–24402. [CrossRef]

- Nowyhed, H.N.; Huynh, T.R.; Thomas, G.D.; Blatchley, A.; Hedrick, C.C. Cutting Edge: The Orphan Nuclear Receptor Nr4a1 Regulates CD8+ T Cell Expansion and Effector Function through Direct Repression of Irf4. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 3515–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Yan, X.; Xiao, M.; Hao, J.; Alekseev, A.; Khong, H.; Chen, T.; et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies NR4A1 as a key mediator of T cell dysfunction. Nature 2019, 567, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; López-Moyado, I.F.; Seo, H.; Lio, C.-W.J.; Hempleman, L.J.; Sekiya, T.; Yoshimura, A.; Scott-Browne, J.P.; Rao, A. NR4A transcription factors limit CAR T cell function in solid tumours. Nature 2019, 567, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lith SC, van Os BW, Seijkens TTP, de Vries CJM (2020) ‘Nur’turing tumor T cell tolerance and exhaustion: novel function for Nuclear Receptor Nur77 in immunity. Eur J Immunol 50:1643–1652.

- Kleberg, J.; Nataraj, A.; Xiao, Y.; Podder, B.R.; Jin, Z.; Tithi, T.I.; Zheng, G.; Smalley, K.S.M.; Moser, E.K.; Safe, S.; et al. Targeting Lineage-Specific Functions of NR4A1 for Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirat, T.; Hayakawa, T.; Mise-Omata, S.; Nakagawara, K.; Ando, M.; Shichino, S.; Ito, M.; Yoshimura, A. NR4a1/2 deletion promotes accumulation of TCF1+ stem-like precursors of exhausted CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.F.; Tan, C.; Mueller, J.L.; Hibiya, K.; Hiwa, R.; Vykunta, V.; Zikherman, J. Negative feedback by NUR77/Nr4a1 restrains B cell clonal dominance during early T-dependent immune responses. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109645–109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Hiwa, R.; Mueller, J.L.; Vykunta, V.; Hibiya, K.; Noviski, M.; Huizar, J.; Brooks, J.F.; Garcia, J.; Heyn, C.; et al. NR4A nuclear receptors restrain B cell responses to antigen when second signals are absent or limiting. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Hill, T.M.; Gordy, L.E.; Suryadevara, N.; Wu, L.; Flyak, A.I.; Bezbradica, J.S.; Van Kaer, L.; Joyce, S. Nur77 controls tolerance induction, terminal differentiation, and effector functions in semi-invariant natural killer T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 17156–17165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fan, F.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y. The nuclear receptor 4A family members: mediators in human disease and autophagy. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2020, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe, S.; Jin, U.-H.; Morpurgo, B.; Abudayyeh, A.; Singh, M.; Tjalkens, R.B. Nuclear receptor 4A (NR4A) family – orphans no more. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 157, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Oki, S.; Ozawa, T.; Hohjoh, H.; Miyake, S.; Yamamura, T. Orphan nuclear receptor NR4A2 expressed in T cells from multiple sclerosis mediates production of inflammatory cytokines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 8381–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G.-X.; Xu, Y.-M. Nr4a1 plays a crucial modulatory role in Th1/Th17 cell responses and CNS autoimmunity. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2018, 68, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, A.J.; Rinner, B.; Pichler, M.; Prochazka, K.; Pansy, K.; Bischof, M.; Fechter, K.; Hatzl, S.; Feichtinger, J.; Wenzl, K.; et al. NR4A3 Suppresses Lymphomagenesis through Induction of Proapoptotic Genes. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2375–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechter K, Feichtinger J, Prochazka K, et al. (2018) Cytoplasmic location of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphomas is associated with a favourable cancer specific survival. Sci Rep 8. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-X.; Ke, N.; Sundaram, R.; Wong-Staal, F. NR4A1, 2, 3 – an orphan nuclear hormone receptor family involved in cell apoptosis and carcinogenesis. 2006, 21, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang JR, Gan WJ, Li XM, et al. (2014) Orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 promotes colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis by regulating MMP-9 and E-cadherin. Carcinogenesis 35:2474–2484. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, G.; Sun, X. Targeting Orphan Nuclear Receptors NR4As for Energy Homeostasis and Diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safe, S.; Shrestha, R.; Mohankumar, K. Orphan nuclear receptor 4A1 (NR4A1) and novel ligands. Essays Biochem. 2021, 65, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Upadhyay, S.; Mariyam, F.; Martin, G.; Hailemariam, A.; Lee, K.; Jayaraman, A.; Chapkin, R.S.; Lee, S.-O.; Safe, S. Flavone and Hydroxyflavones Are Ligands That Bind the Orphan Nuclear Receptor 4A1 (NR4A1). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Luo, Q.; Alitongbieke, G.; Chong, S.; Xu, C.; Xie, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Celastrol-Induced Nur77 Interaction with TRAF2 Alleviates Inflammation by Promoting Mitochondrial Ubiquitination and Autophagy. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 141–153.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safe, S. Natural products and synthetic analogs as selective orphan nuclear receptor 4A (NR4A) modulators. Histol Histopathol. 2024, 39, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | NR4A1 (Nur77) | NR4A2 (Nurr1) | NR4A3 (NOR1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol / Synonyms | NR4A1 / Nur77, TR3, NGFI-B | NR4A2 / Nurr1, NOT, RNR1 | NR4A3 / NOR1, TEC, MINOR, CHN |

| Expression Type | Immediate early gene | Immediate early gene | Immediate early gene |

| DNA Binding | Monomer (NBRE), homodimer or heterodimer (NurRE), RXR dimerization | Monomer (NBRE), homodimer or heterodimer (NurRE), RXR dimerization | Monomer (NBRE); low affinity for NurRE; does not dimerize with RXR |

| Ligand Binding Domain (LBD) | Atypical, constitutively active; binds synthetic ligands (e.g., CsnB) | Atypical but dynamic; binds DHA, AEA, and synthetic molecules | Atypical; potential interaction with unsaturated fatty acids and prostaglandins |

| Tissue Expression | Broad (thymus, spleen, liver, brain, immune cells) | CNS (midbrain dopaminergic neurons), cartilage, immune tissues | Heart, skeletal muscle, immune cells, CNS |

| Canonical Functions | Apoptosis regulation, T cell development, inflammation modulation | Dopaminergic neuron maintenance, anti-inflammatory roles, immune regulation | Vascular remodeling, metabolic regulation, immune homeostasis |

| Role in Immune Response | Suppresses NF-κB signaling, regulates T cell activation and macrophage polarization | Restricts DC immunogenicity, promotes anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes | Modulates DC migration, neutrophil survival, anti-inflammatory effects in monocytes/macrophages |

| Neurological Role | Neuroprotective; expressed in cortex and hippocampus | Essential for dopaminergic neuron development; mutations linked to Parkinson’s disease | Implicated in hippocampal development, inner ear formation, depressive behavior |

| Cardiovascular Involvement | Attenuates vascular inflammation, promotes endothelial homeostasis | Limited but protective role in atherosclerosis | Regulates VSMC proliferation, modulates atherosclerosis progression, promotes cardiac hypertrophy |

| Cancer-Related Functions | Dual role: tumor suppressor or promoter depending on context; modulates immune microenvironment | Tumor suppressor; may inhibit angiogenesis and inflammatory gene expression | Tumor suppressor in AML; involved in oncogenic fusion proteins (e.g., EWS–NR4A3 in sarcomas) |

| Metabolic Regulation | Modulates glucose and lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function | Regulates insulin gene expression and β-cell function | Controls lipid/glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle, insulin secretion |

| Modulators / Ligands | Cytosporone B, 6-mercaptopurine, PDNPA | Anandamide (AEA), DHA, CsnB, prostaglandins | Arachidonic acid, PGA1/PGA2, synthetic fatty acids |

| Therapeutic Potential | Immunotherapy, cancer, inflammation, cardiovascular disease | Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, sepsis, inflammatory disorders | Cardiovascular disease, AML, metabolic syndrome, neurodegeneration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).