Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Vitamin D Binding Protein: Beyond Transport

1.2. VDR-Mediated VDBP Regulation: Complex Network

1.3. Disease-related VDBP and VDR Dysfunction

1.4. Limitations of Current VDR-VDBP Modulation Methods

1.5. Small Molecule Immunomodulators: VDR-Independent Ideas

1.6. Metadichol A New VDR Inverse Agonist

1.7. Study Purposes

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment statement. All experimental work was designed by author was outsourced to a commercial service provider Skanda biolabs in Bangalore, India.

2.2. Protocol for Cell Differentiation

2.3. Treatment Conditions

2.4. ELISA VDBP Quantification

3. Results

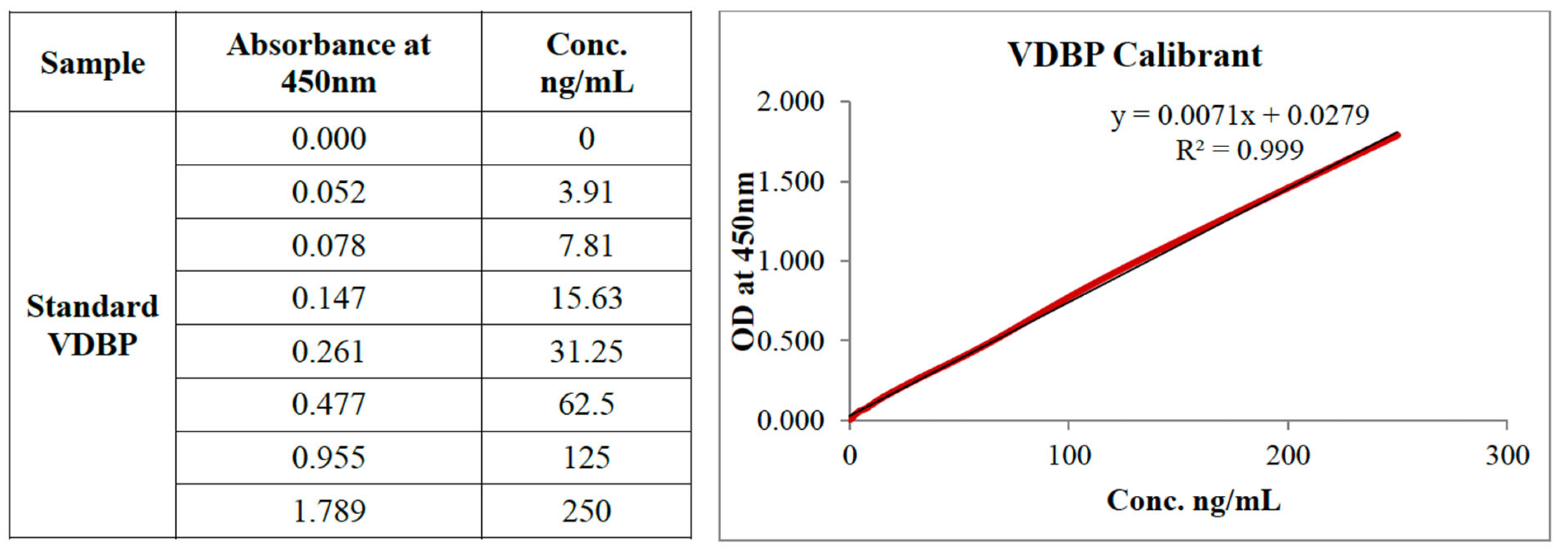

3.1. ELISA Validation and Performance

3.2. Monocytic Cell Line Baseline VDBP and VDR Expression

3.2. U 937 Cell Line Baseline VDBP and VDR Expression

3.3. LPS-Induced VDBP Release via VDR-Independent Pathways

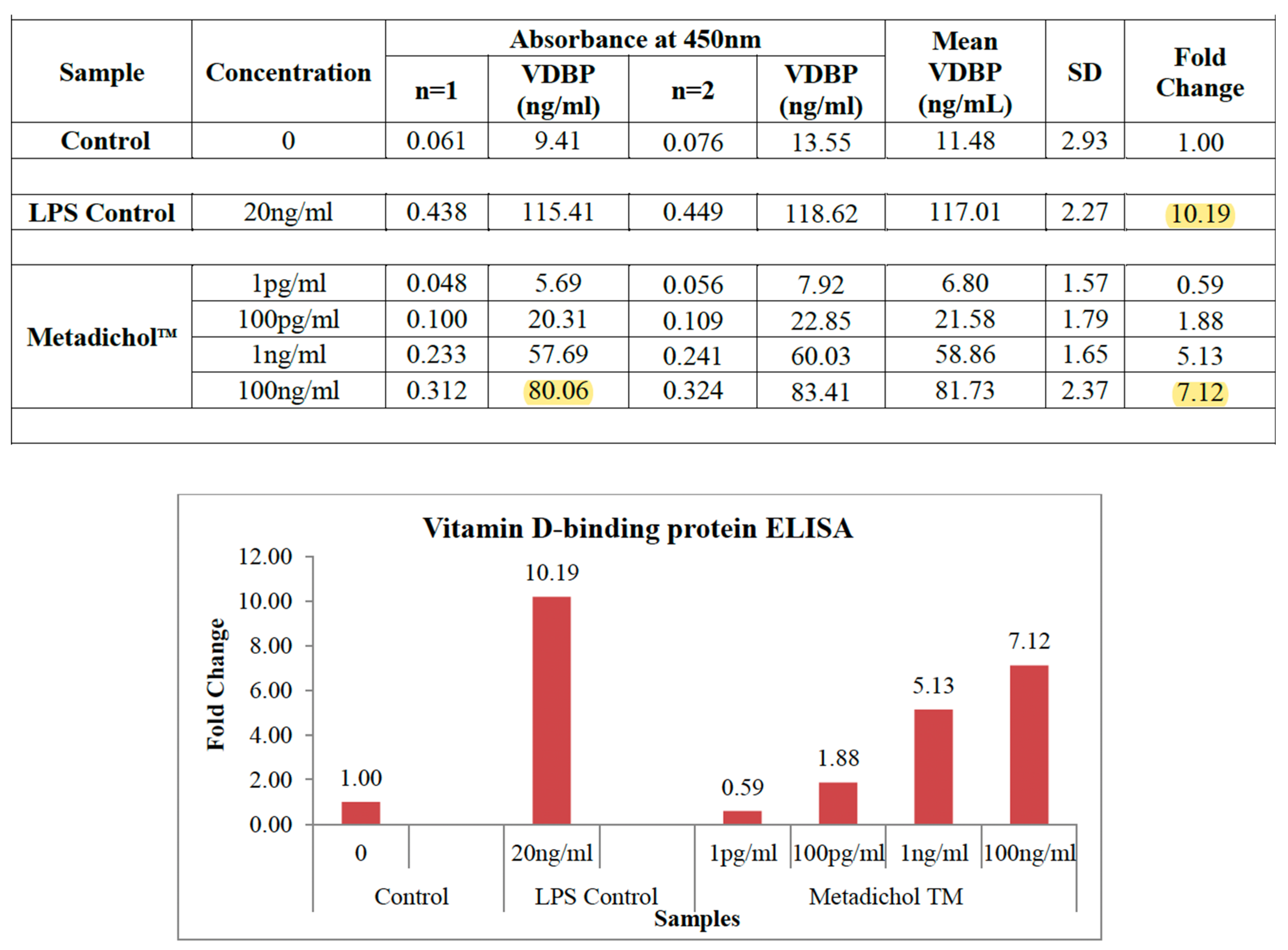

3.4. THP-1 Cell VDR Inverse Agonism Response

3.5. Progressive Dose Escalation Increased VDBP Production via VDR Inverse Agonist Activity

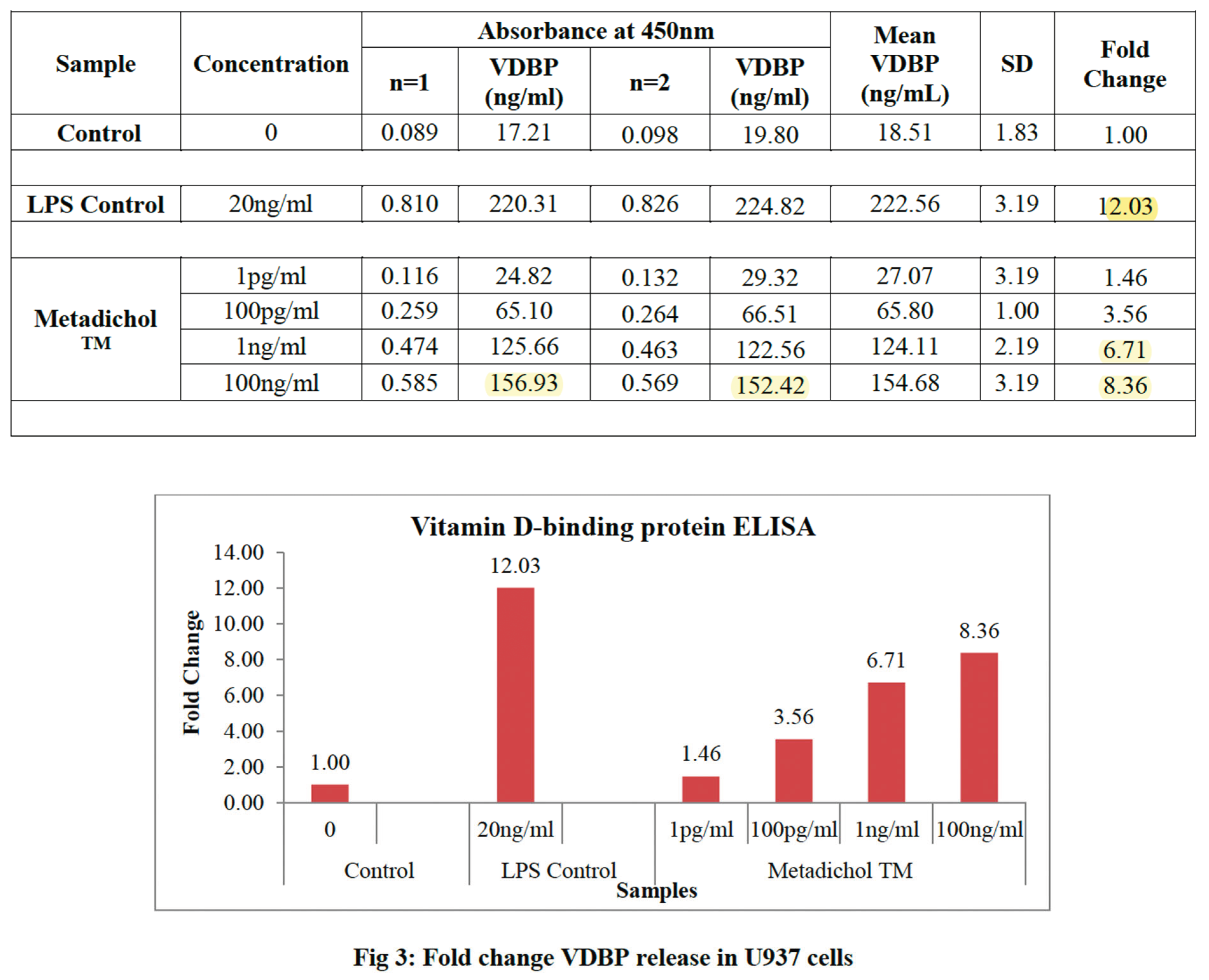

3.6. U937 Cell VDR Inverse Agonism Response

3.7. VDR Inverse Agonism vs. Inflammatory Stimulation Efficacy Comparison

3.8. Inter-Cell Line Variability and VDR-Mediated Consistency

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism: VDR Inverse Agonism and VDBP Regulation

4.2. VDR Inverse Agonism vs. Traditional Immunomodulation

4.2.1. Broader effects of Metadichol Benefits over VDR-Independent Small Molecules

| Component | Function | Interaction with VDBP-VDR Axis | Therapeutic Implications | Key References |

| Sirtuins (SIRT) | NAD+-dependent deacetylases (SIRT1-7) regulating inflammation, metabolism, DNA repair, and aging. SIRT1 inhibits NF-κB, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines; SIRT6 supports DNA repair and metabolism. | SIRT1 reduces inflammation, complementing VDBP’s MAF-mediated immune activation without cytokine storms. SIRT6 enhances metabolic stability, supporting VDBP’s role in vitamin D transport and tissue repair. | Enhances immune balance in cancer, infections, and aging; supports metabolic health in chronic diseases; promotes longevity by countering immunosenescence. | 136,157,158,159, 160 |

| Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) | Nuclear receptor regulating VDBP expression and vitamin D signaling. Constitutive activity suppresses VDBP; Metadichol™ acts as an inverse agonist, reducing VDR activity to boost VDBP (7.12-8.36-fold). | Core component of the axis; VDR inverse agonism derepresses VDBP synthesis, enhancing MAF production for innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. | Corrects VDBP depletion in cancer, infections, and aging; offers targeted immunomodulation without inflammatory side effects of VDR agonists. | 15-20 |

| Toll-Like Receptors (TLR) | Pattern-recognition receptors (e.g., TLR4, TLR7, TLR9) driving innate immune responses via pathogen recognition. Modulated by Metadichol to enhance immune activation. | TLRs amplify pathogen recognition, synergizing with VDBP-MAF’s phagocytic activity. VDR inverse agonism prevents TLR-induced inflammatory overdrive. | Improves pathogen clearance in infections; enhances tumor antigen recognition in cancer; balances metabolic inflammation in chronic diseases. | 68, 110-111,187 |

| Krüppel-Like Factors (KLF) | Zinc-finger transcription factors (e.g., KLF2, KLF4, KLF10) regulating immune cell differentiation, inflammation, and circadian genes. KLF2 suppresses inflammation; KLF10 links immunity and circadian rhythms. | KLFs regulate immune cell function, supporting VDBP-MAF’s immune activation. KLF10 enhances circadian alignment of VDBP-VDR activity, amplifying Metadichol™’s effects. | Suppresses inflammation in cancer and infections; supports circadian-aligned immunity in aging; potential for metabolic regulation via KLF4. | 161-163 |

| Circadian Rhythms | Clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY) regulate immune and metabolic functions diurnally. Modulated by Metadichol™ via SIRT1, VDR, and KLF10 interactions. | Aligns VDBP-VDR activity with immune/metabolic cycles, optimizing phagocytosis and cytokine production. Enhances efficacy of Metadichol™’s multi-pathway modulation. | Optimizes immune responses in infections and cancer; counters circadian disruption in aging and chronic diseases; supports precision medicine with timed dosing. | 164-167 |

| mTOR | Serine/threonine kinase regulating cell growth, proliferation, and immune responses. Downregulated by Metadichol™, reducing excessive immune activation and metabolic stress. | mTOR downregulation complements VDBP-VDR’s controlled immune activation by limiting T-cell overactivation and inflammation, enhancing macrophage-mediated immunity via VDBP-MAF. | Inhibits tumor growth in cancer; reduces inflammatory damage in infections; mitigates metabolic dysfunction in aging and chronic diseases. | 168-170 |

4.3. Difference Between Cytokine-Based and VDR Agonist Therapies

4.4. VDR Inverse Agonist Therapy Clinical Implications

4.5. Infection Control and VDR Dysfunction

4.6. Age-Related VDR Dysfunction and Immune Decline

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest Statement

Statement of Data Availability

References

- Haddad, J.G.; Rojanasathit, S. Acute Administration of 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol in Man. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1976, 42, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speeckaert, M.; Huang, G.; Delanghe, J.R.; Taes, Y.E.C. Biological and clinical aspects of the vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin) and its polymorphism. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 372, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D.D.; Haddad, J.G.; Kowalski, M.A.; Halloran, B.; Gee, E.; Ryzen, E. Assessment of the Free Fraction of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in Serum and Its Regulation by Albumin and the Vitamin D-Binding Protein *. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1986, 63, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, N.; White, P. The Multifunctional Properties and Characteristics of Vitamin D-binding Protein. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 11, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Chishimba, L.; Stockley, R.A.; Thickett, D.R. The vitamin D axis in the lung: a key role for vitamin D-binding protein. Thorax 2010, 65, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, S.N.; McGandy, R.B.; Bailey, S.M.; Nondasuta, A.; Tantiwongse, P. Subcutaneous fat remodelling in Southeast Asian infants and children. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 1985, 68, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, R.E.; Kamboh, M.I. Ethnic variation in vitamin D-binding protein (GC): a review of isoelectric focusing studies in human populations. Hum. Genet. 1986, 72, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, S.; Yamamoto, N. Vitamin D3 binding protein (group-specific component) is a precursor for the macrophage-activating signal factor from lysophosphatidylcholine-treated lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1991, 88, 8539–8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyama, H.; Yamamoto, N. Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer with Gc Protein-Derived Macrophage-Activating Factor, GcMAF. Transl. Oncol. 2008, 1, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Bielenberg, D.R.; Fannon, M.; Gregory, K.J.; Dridi, S.; Wu, J.; Pirie-Shepherd, S.; Huang, B.; Zhao, B. Vitamin D Binding Protein-Macrophage Activating Factor Directly Inhibits Proliferation, Migration, and uPAR Expression of Prostate Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e13428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider GB, Grecco KE, Reichert TA, Lamb DJ. Prognostic significance of serum vitamin D binding protein and macrophage colony stimulating factor in prostate cancer. *Clin Cancer Res*. 2007;13(11):3311-3318. [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Henderson, B.; Reddi, K.; Poole, S.; Meghji, S.; Hopper, C.; Hodges, S.; Wilson, M. Interleukin 6 production by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human fibroblasts is potently inhibited by Naphthoquinone (vitamin K) compounds. Cytokine 1995, 7, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, S.; Punzi, T.; Morucci, G.; et al. Effects of vitamin D-binding protein-derived macrophage-activating factor on human prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 4833–4842. [Google Scholar]

- Thyer, L.; Pacini, S.; Morucci, G.; Ward, E.; Smith, R.; Noakes, D.; Gulisano, M.; Branca, J.J. ; Thyer THERAPEUTIC EFFECTS OF HIGHLY PURIFIED DE-GLYCOSYLATED GCMAF IN THE IMMUNOTHERAPY OF PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC DISEASES. Am. J. Immunol. 2013, 9, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.W.; Meyer, M.B. The Vitamin D Receptor: New Paradigms for the Regulation of Gene Expression by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2010, 39, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussler, M.R.; Whitfield, G.K.; Kaneko, I.; Haussler, C.A.; Hsieh, D.; Hsieh, J.-C.; Jurutka, P.W. Molecular Mechanisms of Vitamin D Action. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 92, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C.; Molnar, F. Current Status of Vitamin D Signaling and Its Therapeutic Applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 528–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D Metabolism, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haid, C.; Chekmenev, D.S.; Kel, A.E. P-Match: transcription factor binding site search by combining patterns and weight matrices. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W432–W437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevde, N.K.; Kim, S.; Pike, J.W.; Watanuki, M.; Meyer, M.B. The Human Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 6 Distal Promoter Contains Multiple Vitamin D Receptor Binding Sites that Mediate Activation by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Intestinal Cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 1447–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, F.H.; Dardenne, O.; Arabian, A.; St-Arnaud, R.; Prud’hOmme, J. Targeted Inactivation of the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-Hydroxylase Gene (CYP27B1) Creates an Animal Model of Pseudovitamin D-Deficiency Rickets*. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 3135–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodera, Y.; Hosoya, T.; Takeyama, K.-I.; Murayama, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Kitanaka, S.; Kato, S. Positive and Negative Regulations of the Renal 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-Hydroxylase Gene by Parathyroid Hormone, Calcitonin, and 1α,25(OH)2D3 in Intact Animals*. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 2224–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsdottir, H.; Pan, J.; Debes, G.F.; Alt, C.; Habtezion, A.; Soler, D.; Butcher, E.C. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to 'program' T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Tang, D.H.; Modlin, R.L. Cutting Edge: Vitamin D-Mediated Human Antimicrobial Activity againstMycobacterium tuberculosisIs Dependent on the Induction of Cathelicidin. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 2060–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantorna, M.T.; Veldman, C.M.; DeLuca, H.F. Expression of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Receptor in the Immune System. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 374, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, C.D.; Manolagas, S.C.; Deftos, L.J.; Provvedini, D.M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 Receptors in Human Leukocytes. Science 1983, 221, 1181–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moras, D.; Mitschler, A.; Klaholz, B.; Rochel, N.; Wurtz, J. The Crystal Structure of the Nuclear Receptor for Vitamin D Bound to Its Natural Ligand. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.W.; Bauer, C.B.; DeLuca, H.F.; Vanhooke, J.L.; Benning, M.M. Molecular Structure of the Rat Vitamin D Receptor Ligand Binding Domain Complexed with 2-Carbon-Substituted Vitamin D3 Hormone Analogues and a LXXLL-Containing Coactivator Peptide, Biochemistry 2004, 43, 4101–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, W.D.; Inderjeeth, C.A.; Chew, G.T.; Vasikaran, S.D.; Taranto, M.; Glendenning, P.; Seymour, H.M.; Gillett, M.J.; Goldswain, P.R.; Musk, A.A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in vitamin D-insufficient hip fracture patients after supplementation with ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol. Bone 2009, 45, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orav, E.J.; Willett, W.C.; Staehelin, H.B.; Stuck, A.E.; Henschkowski, J.; Thoma, A.; Wong, J.B.; Kiel, D.P.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A. Prevention of Nonvertebral Fractures With Oral Vitamin D and Dose Dependency. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.V.; Feldman, D. Mechanisms of the Anti-Cancer and Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Vitamin D. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011, 51, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, K.K.; Trump, D.L.; Johnson, C.S. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: Potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, W.-L.; Pinkel, D.; Collins, C.; Kowbel, D.; Albertson, D.G.; Segraves, R.; Gray, J.W.; Dairkee, S.H.; Ylstra, B. Quantitative mapping of amplicon structure by array CGH identifies CYP24 as a candidate oncogene. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata S, Yanoma S, Nakamura H, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with colorectal cancer: disease progression and survival. *Br J Cancer*. 2018;119(6):744-751. [CrossRef]

- Bektas-Kayhan K, Unur M, Yaylim-Eraltan I, et al. Association of vitamin D binding protein polymorphisms with the risk of oral cancer. In Vivo 2010, 24, 953–957. [Google Scholar]

- Powe, C.E.; Ricciardi, C.; Berg, A.H.; Erdenesanaa, D.; Collerone, G.; Ankers, E.; Wenger, J.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Thadhani, R.; Bhan, I. Vitamin D–binding protein modifies the vitamin D–bone mineral density relationship. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorello, L.B.; Williams, S.M.; Zheng, W.; et al. Blood vitamin D levels in relation to genetic variation in vitamin D receptor and binding protein. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19, 2630–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsa, K.; Seriolo, B.; Paolino, S.; Uprus, M.; Cutolo, M. Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2007, 7, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.; Ibañez, D.; Gladman, D.; Toloza, S.; Urowitz, M. Vitamin D insufficiency in a large female SLE cohort. Lupus 2009, 19, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binion, D.G.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Ulitsky, A.; Naik, A.; Skaros, S.; Zadvornova, Y.; Issa, M. Vitamin D Deficiency in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2011, 35, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeke, F.; Mathieu, C.; Gysemans, C.; Korf, H.; Takiishi, T. Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010, 10, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, M. Antibacterial effects of vitamin D. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 7, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Kinyamu, H.K.; Rafferty, K.; Balhorn, K. Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake in elderly women: effect on serum parathyroid hormone and vitamin D metabolites. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaughlin, J.; Holick, M.F. Aging decreases the capacity of human skin to produce vitamin D3. J. Clin. Investig. 1985, 76, 1536–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawelec, G.; Loeb, M.; Mitnitski, A.; McElhaney, J.; Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Witkowski, J.M. Aging, frailty and age-related diseases. Biogerontology 2010, 11, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derhovanessian, E.; Goldeck, D.; Pawelec, G. Inflammation, ageing and chronic disease. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 29, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Lahore, H.; McDonnell, S.L.; Baggerly, C.A.; French, C.B.; Aliano, J.L.; Bhattoa, H.P. Evidence that Vitamin D Supplementation Could Reduce Risk of Influenza and COVID-19 Infections and Deaths. Nutrients 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solway, J.; Meltzer, D.O.; Vokes, T.; Arora, V.; Best, T.J.; Zhang, H. Association of Vitamin D Status and Other Clinical Characteristics With COVID-19 Test Results. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019722–e2019722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Niles, J.K.; Kroll, M.H.; Kaufman, H.W.; Holick, M.F. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0239252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, D.E.; Ginde, A.A. Vitamin D3 to Treat COVID-19. JAMA 2021, 325, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.L.; Nan, D.; Fernandez-Ayala, M.; García-Unzueta, M.; Hernández-Hernández, M.A.; López-Hoyos, M.; Muñoz-Cacho, P.; Olmos, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Cuadra, M.; Ruiz-Cubillán, J.J.; et al. Vitamin D Status in Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e1343–e1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karumanchi, S.A.; Wenger, J.; Bhan, I.; Powe, C.E.; Berg, A.H.; Nalls, M.; Thadhani, R.; Zhang, D.; Tamez, H.; Powe, N.R.; et al. Vitamin D–Binding Protein and Vitamin D Status of Black Americans and White Americans. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvin, E.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Lutsey, P.L.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Laha, T.J.; Henderson, C.M.; Misialek, J.R. Measurement by a Novel LC-MS/MS Methodology Reveals Similar Serum Concentrations of Vitamin D–Binding Protein in Blacks and Whites. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniol, M.; Autier, P.; Mullie, P.; Pizot, C. Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Lee, I.M.; Christen, W.; Bassuk, S.S.; Mora, S.; Gibson, H.; Gordon, D.; Copeland, T.; D'Agostino, D.; et al. Vitamin D Supplements and Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, F.; Huet, T.; Antony, P.; Moras, D.; Potier, N.; Laverny, G.; Rochel, N.; Belorusova, A.Y.; Molnár, F.; Metzger, D.; et al. A Vitamin D Receptor Selectively Activated by Gemini Analogs Reveals Ligand Dependent and Independent Effects. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, L.P.; Mizwicki, M.T.; Bula, C.M.; Norman, A.W.; Moras, D.; Bishop, J.E.; Keidel, D.; Wurtz, J.-M. Identification of an alternative ligand-binding pocket in the nuclear vitamin D receptor and its functional importance in 1α,25(OH) 2 -vitamin D 3 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 12876–12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J.; Slatopolsky, E. Vitamin D analogs: therapeutic applications and mechanisms for selectivity. Mol. Aspects Med. 2008, 29, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierold C, Mings JA, DeLuca HF. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide induces 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) gene expression in fetal rat calvaria cells. *J Biol Chem*. 2001;276(26):23804-23810. [CrossRef]

- Rueda, S.; Romero, F.; Vidal, J.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; de Osaba, M.J.M. Vitamin D, PTH, and the Metabolic Syndrome in Severely Obese Subjects. Obes. Surg. 2008, 18, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Valero, V.; Rubio, E.; Esteva, I.; Colomo, N.; Soriguer, F.; Gutierrez, C.; González-Molero, I.; de Adana, M.S.R.; Rojo-Martínez, G.; Morcillo, S.; et al. Hypovitaminosis D and incidence of obesity: a prospective study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 680–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto N, Willett NP. Immunotherapeutic synergism between vitamin D-binding protein-derived macrophage activating factor and phagocytosis-activating factor on monocyte and macrophage activities. *Integr Cancer Ther*. 2013;12(6):500-518. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Urade, M. Pathogenic significance of alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase activity found in the hemagglutinin of influenza virus. Microbes Infect. 2005, 7, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symoens, J.; Rosenthal, M. Levamisole in the modulation of the immune response: the current experimental and clinical state. J. Reticuloendothel. Soc. 1977, 21, 175–221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janssen PH, Janssen PA. The activity of levamisole after parenteral administration in mice. *Toxicol Appl Pharmacol*. 1972;21(1):45-54. [CrossRef]

- Hemmi, H.; Takeda, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Sanjo, H.; Kaisho, T.; Horiuchi, T.; Tomizawa, H.; Akira, S.; Sato, S.; Hoshino, K. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88–dependent signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, M. Imiquimod: mode of action. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 157, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, A.M. CpG Motifs in Bacterial DNA and Their Immune Effects. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 20, 709–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, A.M.; Rasmussen, W.L.; Ballas, Z.K. Induction of NK activity in murine and human cells by CpG motifs in oligodeoxynucleotides and bacterial DNA. J. Immunol. 1996, 157, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R.; Krause, C.D.; Pestka, S. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2004, 202, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinchieri, G. Type I interferon: friend or foe? J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2053–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.M.; Borden, E.C.; Smith, T.J.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Blum, R.H.; Strawderman, M.H. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996, 14, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haluska, F.G.; Jonasch, E. Interferon in Oncological Practice: Review of Interferon Biology, Clinical Applications, and Toxicities. Oncol. 2001, 6, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B. Medicinal properties of Echinacea: A critical review. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, K.I.; Mead, M.N. Immune System Effects of Echinacea, Ginseng, and Astragalus: A Review. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.; Brown, G.D. A new receptor for β-glucans. Nature 2001, 413, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.J.; Goodridge, H.S.; Underhill, D.M. β-glucan recognition by the innate immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 230, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetvicka, V.; Vannucci, L.; Sima, P.; Richter, J. Beta Glucan: Supplement or Drug? From Laboratory to Clinical Trials. Molecules 2019, 24, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Policosanol nano. US patent 8,722,093. May 13, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, PR. Policosanol nano. US patent 9,034,383. May 19, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, PR. Policosanol nano. US patent 9,006,292. April 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, P.; Azemar, N.; Nolla, J.; Solans, C.; Garcia-Celma, M. Nano-emulsions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 10, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions versus microemulsions: terminology, differences, and similarities. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenakin, T. Inverse, protean, and ligand-selective agonism: matters of receptor conformation. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, R.A.; Ijzerman, A.P. Recent developments in constitutive receptor activity and inverse agonism, and their potential for GPCR drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 27, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelen, G.; Bouillon, R.; Tocchini-Valentini, G.; Vandewalle, M.; De Clercq, P.; Moras, D.; Claessens, F.; Verlinden, L.; Verstuyf, A.; Rochel, N. Superagonistic Action of 14-epi-Analogs of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D Explained by Vitamin D Receptor-Coactivator Interaction. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkkonen, L.; Väisänen, S.; Dunlop, T.W.; Frank, C.; Carlberg, C. Spatio-temporal Activation of Chromatin on the Human CYP24 Gene Promoter in the Presence of 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 350, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, T.; Izquierdo, P.; Esquena, J.; Solans, C. Formation and stability of nano-emulsions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 108-109, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, N.; Benoit, J.-P.; Saulnier, P. Design and production of nanoparticles formulated from nano-emulsion templates—A review. J. Control. Release 2008, 128, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, S.; Shakeel, F.; Talegaonkar, S.; Ahmad, F.J.; Khar, R.K.; Ali, M. Development and bioavailability assessment of ramipril nanoemulsion formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007, 66, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaiko, J.; McClements, D.J. Low-energy formation of edible nanoemulsions by spontaneous emulsification: Factors influencing particle size. J. Food Eng. 2015, 146, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol and vitamin C increase in vivo, an open-label study. *Vitam Miner*. 2017;6:163. [CrossRef]

- Auwerx, J. The human leukemia cell line, THP-1: A multifacetted model for the study of monocyte-macrophage differentiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1991, 47, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, C.; Nilsson, K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937). Int. J. Cancer 1976, 17, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell T, Behnke WD, Woodford TA, Schreiber RE. Enhanced proteolytic activity of activated human monocytes. *Cell Immunol*. 1985;97(2):354-364. [CrossRef]

- Hass R, Bartels H, Topley N, et al. TPA-induced differentiation and adhesion of U937 cells: changes in ultrastructure, cytoskeletal organization and expression of cell surface antigens. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1989, 48, 282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Sims, G.P.; Chen, X.X.; Gu, Y.Y.; E Lipsky, P.; Chen, S. Modulatory Effects of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 on Human B Cell Differentiation. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1634–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kohro, T.; Hamakubo, T.; Aburatani, H.; Kodama, T.; Wada, Y. A Comparison of Differences in the Gene Expression Profiles of Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate Differentiated THP-1 Cells and Human Monocyte-derived Macrophage. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2004, 11, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, S.; To, J.; Lund, M.E.; O'BRien, B.A. The choice of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate differentiation protocol influences the response of THP-1 macrophages to a pro-inflammatory stimulus. J. Immunol. Methods 2016, 430, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.K.; Jung, H.S.; Yang, H.I.; Yoo, M.C.; Kim, C.; Kim, K.S. Optimized THP-1 differentiation is required for the detection of responses to weak stimuli. Inflamm Res. 2007, 56, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, K.S.; Yadav, N.P.; Rai, V.K.; Mishra, N. Nanoemulsion as pharmaceutical carrier for dermal and transdermal drug delivery: Formulation development, stability issues, basic considerations and applications. J. Control. Release 2018, 270, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, T.A.; Gupta, A.; Eral, H.B.; Doyle, P.S. Nanoemulsions: formation, properties and applications. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 2826–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.S.; Glenn, D.J.; Nishimoto, M.; Gardner, D.G.; Olsen, K.; Chen, S.; Ni, W.; Grigsby, C.L. Expression of the Vitamin D Receptor Is Increased in the Hypertrophic Heart. Hypertension 2008, 52, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, R.; Hewison, M.; Stewart, P.M.; Zehnder, D.; Howie, A.J.; Williams, M.C.; McNinch, R.W. Extrarenal Expression of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-Hydroxylase1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raetz, C.R.H.; Whitfield, C. Lipopolysaccharide Endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 635–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.S.; Lee, J.-O. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2013, 45, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanput, W.; Mes, J.J.; Wichers, H.J. THP-1 cell line: An in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigneault, M.; Preston, J.A.; Marriott, H.M.; Whyte, M.K.B.; Dockrell, D.H. The Identification of Markers of Macrophage Differentiation in PMA-Stimulated THP-1 Cells and Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z. The use of THP-1 cells as a model for mimicking the function and regulation of monocytes and macrophages in the vasculature. Atherosclerosis 2012, 221, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.R.; Ihle, J.N.; Spivak, J.L. Interleukin 3 promotes the in vitro proliferation of murine pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1985, 76, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G.; E Cooke, N.; Walgate, J. Human serum binding protein for vitamin D and its metabolites. II. Specific, high affinity association with a protein in nucleated tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 5965–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, R.; Sibug, M.; Liuzzo, J.; Webster, R. Localization and quantitation of the vitamin D binding protein (Gc- globulin) in human neutrophils. Blood 1993, 82, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.; Perez, H.D.; Chenoweth, D.; Elfman, F. Identification of the C5a des Arg cochemotaxin. Homology with vitamin D-binding protein (group-specific component globulin). J. Clin. Investig. 1988, 82, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, P.; Mosekilde, L.; Hermann, A.P.; Brot, C.; Lauridsen, A.L.; Heickendorff, L.; Nexo, E. Plasma concentrations of 25-Hydroxy-Vitamin D and 1,25-Dihydroxy-Vitamin D are Related to the Phenotype of Gc (Vitamin D-Binding Protein): A Cross-sectional Study on 595 Early Postmenopausal Women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2005, 77, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, R.; Larson, C.; I Shulman, A.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Structural Determinants of Allosteric Ligand Activation in RXR Heterodimers. Cell 2004, 116, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, F.; Callow, P.; Peluso-Iltis, C.; Haertlein, M.; Moras, D.; Moulin, M.; Mély, Y.; Roessle, M.; I Svergun, D.; Rochel, N.; et al. Common architecture of nuclear receptor heterodimers on DNA direct repeat elements with different spacings. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, J.; Constans, J. Affinity differences for vitamin D metabolites associated with the genetic isoforms of the human serum carrier protein (DBP). Hum. Genet. 1993, 92, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, J.; Gomme, P.T. Therapeutic potential of vitamin D-binding protein. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, L.; Blumberg, H.M.; E Judd, S.; Ziegler, T.R.; Yamshchikov, A.V.; Tangpricha, V.; Martin, G.S. Alterations in vitamin D status and anti-microbial peptide levels in patients in the intensive care unit with sepsis. J. Transl. Med. 2009, 7, 28–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellert, C.; Ball, D.; Brenner, H.; Schöttker, B. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and overall mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastani Z, Berger C, Langsetmo L, et al. In healthy adults, biological activity of vitamin D, as assessed by expression of cathelicidin, varies with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. *J Clin Endocrinol Metab*. 2013;98(7):2944-2951. [CrossRef]

- Hollis, B.W.; Safadi, F.F.; Liebhaber, S.A.; Thornton, P.; Gentile, M.; Haddad, J.G.; Magiera, H.; Cooke, N.E. Osteopathy and resistance to vitamin D toxicity in mice null for vitamin D binding protein. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zella JB, McCary LC, DeLuca HF. Oral administration of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 completely protects vitamin D receptor knockout mice from lethal external calcium stress. *Arch Biochem Biophys*. 2003;417(1):77-83. [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.H.; Mäder, K.; Gohla, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery--a review of the state of the art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, R. BioMEMS: state-of-the-art in detection, opportunities and prospects. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W. Formulation of poorly water-soluble drugs for oral administration: Physicochemical and physiological issues and the lipid formulation classification system. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 29, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevaskis, N.L.; Charman, W.N.; Porter, C.J.H. Lipids and lipid-based formulations: optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Miyamoto, K.-I.; Pike, J.W.; Li, B.; Taketani, Y.; Morita, K.; Kitano, M.; Takeda, E.; Inoue, Y. The Caudal-Related Homeodomain Protein Cdx-2 Regulates Vitamin D Receptor Gene Expression in the Small Intestine. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999, 14, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.W.; Goetsch, P.D.; Meyer, M.B. VDR/RXR and TCF4/β-Catenin Cistromes in Colonic Cells of Colorectal Tumor Origin: Impact on c-FOS and c-MYC Gene Expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Camp, M.; Convents, R.; Marcelis, S.; Bouillon, R.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L. Action of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the cell cycle genes, cyclin D1, p21 and p27 in MCF-7 cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1998, 142, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, M.; Cano, A.; Baulida, J.; de Herreros, A.G.; Lafarga, M.; Puig, I.; Espada, J.; Berciano, M.T.; PálMer, H.G.; GonzálEz-Sancho, J.M.; et al. Vitamin D3 promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of β-catenin signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 154, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amery, W.K.; Bruynseels, J.P. Levamisole, the story and the lessons. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1992, 14, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, P.R. Metadichol®: A nano lipid emulsion that expresses all 49 nuclear receptors in stem and somatic cells. Arch. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2023, 7, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P. Metadichol, a Natural Ligand for the Expression of Yamanaka Reprogramming Factors in Human Cardiac, Fibroblast, and Cancer Cell Lines. Med Res. Arch. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P. Metadichol®-induced expression of circadian clock transcription factors in human fibroblasts. Med Res. Arch. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.R. Metadichol-Induced Differentiation of Pancreatic Ductal Cells (PANC-1) into Insulin-Producing Cells. Med Res. Arch. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. The quest for immortality: introducing Metadichol®, a novel telomerase activator. *J Stem Cell Res Ther*. 2019;9(446):2. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol®, a novel agonist of the anti-aging Klotho gene in cancer cell lines. *J Cancer Sci Ther*. 2018;10(11):351-357. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol®, vitamin C and GULO gene expression in mouse adipocytes. *Biol Med (Aligarh)*. 2018;10(426):2. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol® induced high levels of vitamin C: case studies. *Vitam Miner*. 2017;6(169):4. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol®: a novel inverse agonist of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and NRF2 inhibitor. *J Cancer Sci Ther*. 2017;9(9):661-668. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol, a novel ROR gamma inverse agonist, and its applications in psoriasis. *J Clin Exp Dermatol Res*. 2017;8(6):433. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.R. Metadichol®: A novel inverse agonist of thyroid receptor and its applications in thyroid diseases. Biol. Med. (Aligarh) 2019, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, PR. Metadichol modulates the DDIT4-mTOR-p70S6K axis: a novel therapeutic strategy for mTOR-driven diseases. Preprint. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.R. Metadichol® induced expression of TLR family members in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Med Res. Arch. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amery WK, Bruynseels JP. Levamisole, the story and the lessons. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1992;14:481-486.

- Van Dijk A, Sillevis Smitt PA, Verbeek MM, et al. Agranulocytosis associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use: A case series. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10:160-166.

- Navi, D.; Huntley, A. Imiquimod 5 percent cream and the treatment of cutaneous malignancy. Dermatol. Online J. 2004, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, I.; Golitz, L.; Owens, M.; Lindholm, J.; Geisse, J.; Stampone, P. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results from two phase III, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 50, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, A.M.; Vollmer, J. Immunotherapeutic applications of CpG oligodeoxynucleotide TLR9 agonists. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug A, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, et al. Identification of CpG oligonucleotide sequences with high induction of IFN-alpha/beta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. *Eur J Immunol*. 2001;31(7):2154-2163. [CrossRef]

- Krieg, A.M.; Hartmann, G. Mechanism and Function of a Newly Identified CpG DNA Motif in Human Primary B Cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinman, D.M. Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhe, R.; Jaiswal, M.; Sharma, P.K. Nanoemulsion: an advanced mode of drug delivery system. 3 Biotech 2014, 5, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, A.A.; Desai, N.; Dixit, R.; Nagarsenker, M. Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems: formulation insights, applications and advances. Nanomedicine 2010, 5, 1595–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerszten, R.E.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Mattson, M.P.; Kohrt, W.M.; Kraus, W.E.; Jakicic, J.M.; Bamman, M.M.; Cooper, D.M.; Boyce, A.T.; Rodgers, M.; et al. Understanding the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Physical Activity-Induced Health Benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olefsky, J.M.; Glass, C.K. Inflammation and Lipid Signaling in the Etiology of Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, B.B.; Yang, V.W. Mammalian Krüppel-Like Factors in Health and Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1337–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Krüppel-like factors in immune regulation. *J Leukoc Biol*. 2012;91(4):559-571. [CrossRef]

- Baginska, J.; Viry, E.; Berchem, G.; Poli, A.; Noman, M.Z.; van Moer, K.; Medves, S.; Zimmer, J.; Oudin, A.; Niclou, S.P.; et al. Granzyme B degradation by autophagy decreases tumor cell susceptibility to natural killer-mediated lysis under hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17450–17455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisaki, Y.; Scheiermann, C.; Frenette, P.S. Circadian control of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzini, E.; Massimiliano, L.; Penna, G.; Rescigno, M. Oral Tolerance Can Be Established via Gap Junction Transfer of Fed Antigens from CX3CR1+ Macrophages to CD103+ Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2014, 40, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schibler, U.; Asher, G. Crosstalk between Components of Circadian and Metabolic Cycles in Mammals. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, E.; Farina, C. Astrocytes: Key Regulators of Neuroinflammation. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Kepp, O.; Smyth, M.J. Type I interferons in anticancer immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in immune cells. *J Cell Biol*. 2012;197(2):241-251. [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, A.; Lindenmann, J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B. Biol. Sci. 1957, 147, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestka, S. The Interferons: 50 Years after Their Discovery, There Is Much More to Learn. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20047–20051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, R.; Hewison, M.; Stewart, P.M.; Zehnder, D.; Wheeler, D.C.; Howie, A.J.; Williams, M.C.; Chana, R.S. Synthesis of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 by Human Endothelial Cells Is Regulated by Inflammatory Cytokines. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeyama, K.-I.; Yanagisawa, J.; Kobori, M.; Kitanaka, S.; Kato, S.; Sato, T. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D 3 1α-Hydroxylase and Vitamin D Synthesis. Science 1997, 277, 1827–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohe, B.; Safford, S.E.; Nemere, I.; Farach-Carson, M.C. Regulation of expression of 1,25D3-MARRS/ERp57/PDIA3 in rat IEC-6 cells by TGFβ and 1,25(OH)2D3. Steroids 2007, 72, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussler, M.R.; Haussler, C.A.; Jurutka, P.W.; Thompson, P.D.; Hsieh, J.C.; Remus, L.S.; Selznick, S.H.; Whitfield, G.K. The vitamin D hormone and its nuclear receptor: molecular actions and disease states. J. Endocrinol. 1997, 154, S57–S73. [Google Scholar]

- Korth, M.J.; Martin, T.R.; Tisoncik, J.R.; Katze, M.G.; Farrar, J.; Simmons, C.P. Into the Eye of the Cytokine Storm. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, J.W.; Borish, L.C. 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, S460–S475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.S.; Krishnan, A.V.; Feldman, D.; Trump, D.L. The Role of Vitamin D in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2010, 39, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.S.; Deeb, K.K.; Trump, D.L. Vitamin D: Considerations in the Continued Development as an Agent for Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Cancer J. 2010, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, P.; Van Haver, D.; Bouillon, R.; Gysemans, C.; Mathieu, C.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Eelen, G.; Vanoirbeek, E. Mechanism and Potential of the Growth-Inhibitory Actions of Vitamin D and Analogs. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1893–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee P, Chatterjee M. Antiproliferative role of vitamin D-related pathway in prostate cancer: literature review. *J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol*. 2003;84(2-3):225-236. [CrossRef]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitvogel, L.; Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Kroemer, G. Immunological aspects of cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Allison, J.P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 2015, 348, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-Like Receptor Triggering of a Vitamin D-Mediated Human Antimicrobial Response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, P.; Christakos, S.; Yim, S.; Ragunath, C.; Diamond, G. Induction of cathelicidin in normal and CF bronchial epithelial cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2007, 6, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, A.R.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Hooper, R.L.; Greenberg, L.; Aloia, J.F.; Bergman, P.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Esposito, S.; Ganmaa, D.; Ginde, A.A.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 2017, 356, i6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, P.; Lindh, A.U.; Björkhem-Bergman, L.; Lindh, J.D. Vitamin D and Respiratory Tract Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T.; Dupuis, G.; Lesur, O.; Gayoso, I.; Tarazona, R.; Solana, R. Innate immunosenescence: Effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Semin. Immunol. 2012, 24, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubeck-Loebenstein, B.; Weiskopf, D.; Weinberger, B. The aging of the immune system. Transpl. Int. 2009, 22, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Campisi, J. Chronic Inflammation (Inflammaging) and Its Potential Contribution to Age-Associated Diseases. J. Gerontol. A Ser. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69 (Suppl. 1), S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecino-Rodriguez, E.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Dorshkind, K. Causes, consequences, and reversal of immune system aging. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modesti, M.; Loreto, M.F.; Corsi, M.P.; De Martinis, M.; Ginaldi, L. Immunosenescence and infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2001, 3, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, S.C. Clinical Relevance of Age-Related Immune Dysfunction. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, M.; Miquel, J. An Update of the Oxidation-Inflammation Theory of Aging: The Involvement of the Immune System in Oxi-Inflamm-Aging. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 3003–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, C.; Colonna-Romano, G.; Caruso, M.; Grimaldi, M.P.; Listi, F.; Lio, D.; Candore, G.; Balistreri, C.R.; Nuzzo, D.; Vasto, S. Inflammatory networks in ageing, age-related diseases and longevity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2007, 128, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Metadichol Study Finding | Literature Context | Advancement Over Literature |

| Mechanism | Dose-dependent VDBP release via VDR inverse agonism (7.12-fold in THP-1, 8.36-fold in U937 at 100 ng/ml). | Traditional approaches use VDR agonists (e.g., calcitriol) or antagonists, which often suppress VDBP through feedback or block beneficial VDR functions . | Introduces VDR inverse agonism, reducing constitutive VDR activity to derepress VDBP synthesis, avoiding negative feedback and preserving VDR functions. |

| Dose-Response | Sigmoidal dose-response curve (1 pg/ml to 100 ng/ml), indicating selective VDR modulation. | Literature lacks consistent dose-response data for VDBP modulation due to non-specific mechanisms or poor pharmacokinetics | Predictable, selective VDR binding with a clear dose-response relationship, enhancing therapeutic precision. |

| Immune Activation | Achieves ~70% of LPS-induced VDBP levels without excessive inflammation. | Immunomodulators like TLR agonists or interferons induce inflammation, worsening VDR-VDBP dysregulation | Controlled immune activation via VDR pathway, minimizing inflammatory side effects like cytokine storms. |

| Formulation | Nanoemulsion enhances bioavailability, enabling effective VDR modulation at low doses. | Traditional small molecules have hydrophobic limitations, reducing intracellular target reach | Improved cellular uptake and nuclear delivery, allowing lower doses for VDR interaction. |

| VDBP Supplementation | Stimulates endogenous VDBP production, bypassing exogenous delivery. | Direct VDBP/MAF supplementation is limited by protein instability, immunogenicity, and glycosylation complexity | Endogenous VDBP induction is more physiologically relevant, avoiding stability and immune reaction issues. |

| Non-Specific Immunomodulators | Targets VDR-VDBP axis, addressing underlying dysregulation. | Small molecules (e.g., levamisole, imiquimod, CpG) act via VDR-independent pathways, failing to correct VDBP depletion | Directly addresses VDBP deficiency, integrating TLR, sirtuin, and nuclear receptor modulation for broader efficacy. |

| Disease Relevance | Restores VDBP in cancer, infections, and aging by countering VDR hyperactivity. | VDR-VDBP dysregulation in cancer is poorly addressed by existing therapies | Targets root cause of VDBP depletion, offering potential in cancer immunotherapy, infection control, and immune senescence. |

| Therapeutic Potential | Consistent dose-response across cell lines suggests personalized therapy based on VDR/VDBP status. | Current therapies lack specificity and personalization, with variable efficacy | Enables tailored immunomodulation, leveraging conserved VDR mechanisms for diverse patient profiles. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).