1. Introduction

Day-Ahead Markets (DAM) of electricity are markets in which, on each day, prices for the 24 hours of the next day form at once in an auction, usually held at midday. The data obtained from these markets are organized and presented in a discrete hourly time sequence, but actually the 24 prices of each day share the same information. Accurate encoding and synthetic generation of these time series is important not only as a response to a theoretical challenge, but also for the practical purposes of short term price risk management. The most important features of the hourly price sequences are night/day seasonality, casual sudden upward spikes appearing only at daytime, downward spikes appearing at night time, spike clustering, and long memory with respect to previous days. From a modeling point of view, all of this can mean nonlinearity. Different research communities have developed different DAM prices nonlinear modeling and forecasting methods, discussed and neatly classified some time ago in Ref. [

1]. Interestingly, in Ref. [

1] it is also noted that a large part of papers and models in this research area can be mainly attributed to just two cultures, that of econometricians/statisticians and that of engineers/computational intelligence (CI) people. This bipartition seems to be still valid nowadays. DAM econometricians tend to use discrete time stochastic autoregressions for point forecasting and quantile regressions for probabilistic forecasting [

2], whereas DAM CI people prefer to work with machine learning methods, in some cases also fully probabilistic [

3,

4]. For example, the CI community has adopted so far deep learning techniques both for point forecasting such as recurrent networks (see for example the NBEATSx model [

5,

6] applied to DAM data), and for probabilistic forecasting like conditional GANs [

7,

8,

9] and normalizing flows. In addition, there exist deep learning forecasting models which were never tested on DAM price forecasting. For example, the Temporal Fusion Transformer [

10] can do probabilistic forecasting characterized by learning temporal relationships at different scales, emphasizing the importance of combining probabilistic accuracy with interpretability. DeepAR [

11] is able to predict joint Gaussian distributions (in its DeepVAR form). Noticeably, often these models use the depth dimension for trying to capture multi-scale details (along the day time coordinate and along hours of the same day), at the expense of requiring a very large number of parameters. In their inception, the machine learning methods were often applied to DAM data as black box tools, with a research stance focused mainly on checking whether they work or not on specific data sets. Nowadays internal parts of model architecture are explicitly dedicated to exploiting specific behaviors, like in the NBEATSx model. In any case, this `two-cultures paradigm’ finding, earlier discussed in Ref.[

12] for a broader context, is stimulating in itself, because it can orientate further research.

Building on these grounds, this paper, taking the stance of econometrics but still making use of `old style’, shallow machine learning, will discuss the use of the Vector Mixture (VM) and Vector Hidden Markov Mixture (VHMM) family of models in the context of DAM prices modeling and scenario generation. This family of models is usually approached by the econometrics and CI communities with two different formalisms, so that it can misleadingly appear from the two perspectives as two different families. The VM/VHMM family is based on Gaussian mixtures and hidden Markov models, well known in machine learning [

13], where it is studied using a fully probabilistic approach [

14]. In this paper it will be shown that the members of this family correspond to the Gaussian regime switching 0-lag vector autoregressions of standard econometrics, studied instead using a stochastic difference equations approach. Actually, already at a first inspection VMs/VHMMs and regime switching autoregressions should suggest that they share some features. They are both based on latent (that is, hidden) variables, and are both intrinsically nonlinear. Moreover, it will be shown that they too can exploit a depth dimension which can be very useful for modeling important details of the data. Being vector models they both can remove fake memory effects from hourly time series by directly modeling them as vector series. Yet, there are also common properties that are usually ascribed to the machine learning side only. For example, it is known that because VMs and VHMMs can do unsupervised deep learning (which however current deep learning models usually don’t do), they can automatically organize time series information in a hierarchical and transparent way, which for DAMs lends itself to direct market interpretation. Being VM and VHMM models generative [

15], the synthetic series which they produce automatically include many of the features and fine details present in time series. VMs and VHMMs can do probabilistic forecasting almost by definition. Yet, these features are not usually ascribed to the regime switching 0-lag vector autoregression models too. VMs and VHMMs have also features, knowingly shared by regime switching 0-lag vector autoregressions, which usually are not liked by econometricians. Being generative models, they are not based on errors (i.e. innovations) unlike non-zero lag autoregressions and other discriminative models for time series [

16], so that cross-validation, residual analysis and direct comparison with standard autoregressions is not easy. Moreover, being generative and based on hidden states, the way they forecast is different from usual non-zero lag autoregression forecasting. It can be thus interesting and useful to work out in detail these common properties hidden behind the two different formalisms adopted by the two communities, keeping also in mind that to linear econometric models the issue of interpretability is not usually attributed. It can also be interesting to try to understand how these common properties can be profitably used in DAM prices scenario generation and analysis.

Thus, this paper has three aims. First, it will discuss both the VM and VHMM approach to DAM series and how to include an important hierarchical structure in the VM and VHMM models. Second, it will study their behavior on a freely downloadable specific DAM prices data set

1 coming from the DAM of Alberta in Canada. In the basic Gaussian form in which it will be presented in this paper, the VM/VHMM approach works with stochastic variables with support on the full real line, so that this approach can be directly applied to series which allow for both negative and positive values. Yet, since in the paper the approach will be tested on one year of prices from the Alberta DAM (

values), which are positive and capped, logprices will be everywhere used instead of prices. Estimation of VM/VHMM models relies on sophisticated and efficient algorithms like the Expectation-Maximization, Baum-Welch and Viterbi algorithms. Some software packages exist to facilitate estimation. The two very good open source free Matlab packages

BNT and

pmtk3 by K. Murphy [

17] were used for many of the computations of this paper. In alternative, one can also use

pomegranate [

18], a package written in Python. Third, it will try to narrow the gap between the two research communities, by exploring a model class which can be placed at the intersection among those used by the two communities. In the end, these very simple models will be shown to be able to learn latent price regimes from historical data in a highly structured and unsupervised fashion, enabling the generation of realistic market scenarios and also probabilistic forecasts, while maintaining straightforward econometrics-like explainability.

The paper can be thought as being made up by two parts. After this Introduction,

Section 2 will define suitable notation and review usual vector autoregression modeling to prepare the discussion on VMs and VHMMs for DAM prices.

Section 3 will introduce VMs as machine learning dynamical mixture systems uncorrelated in interday dynamics but correlated in intraday dynamics, and will discuss their inherent capacity of doing clustering.

Section 4 will discuss VMs as regime switching models, i.e. as econometric models. It will also show how they can be made deeper, that is, hierarchical. This feature will come especially at hand when they will be extended into VHMMs in a parsimonious way in terms of number of parameters.

Section 5 will very briefly discuss forecasting with VMs.

Section 6 will show the behavior of VMs when applied to Alberta DAM data in terms of clustering, interpretation of parameters, and scenario generation ability.

Section 2 to

Section 6 will make up the first part of the paper.

Section 7 will introduce VHMMs as models fully correlated in both intraday and interday dynamics, and will discuss their deep learning structure.

Section 8 will briefly discuss forecasting with VHMMs.

Section 9 will show the behavior of VHMMs when applied to Alberta DAM data, their better scenario generation ability in comparison to VMs, and their special ability of modeling spike clustering.

Section 7 to

Section 9 will make up the second part of the paper.

Section 10 will conclude.

2. Notation and Generative vs. Discriminative Autoregression Modeling

This Section will define suitable notation and review usual vector modeling. This will help putting in context related literature and to prepare the discussion on vector mixtures and Markov models of the following Sections.

Consider the DAM equispaced hourly sample time series

of values

, where

t indicates a given hour starting from the beginning of the sample. In order to link the following discussion with the Alberta data, in what follows

will be assumed to be logprices. In DAMs the next day 24 logprices form at once on each day and share the same information, so that it makes microeconomic sense to regroup the hourly scalar series into a daily vector sample series

of

N days, where the vectors

have 24 coordinates

each obtained from

by the mapping

, and are labeled by the day index

d and the day’s hour

h. The series

can be thought as having been sampled from a stochastic chain

of vector stochastic variables

modeled as the vector autoregression

In Eq. (1)

d labels the current day (at which the future at day

is uncertain),

is a day-independent vector function with hourly components

that characterizes the structure of the autoregression model,

labels a set of lagged regressors of

where

is the number of present plus past days on which day

is regressed, with the convention that for

no

variables appear in

. The earliest day in

is hence

, so that for example for

only

is used as a regressor (i.e. 24 hours) and, for

, both

and

(i.e. 48 hours) are used. Hence the autoregression in Eq. (1) uses

vector stochastic variables in all, which include the

variable. For

, i.e.

, Eq. (1) thus represents a 0-lag autoregression. In Eq. (1)

represents the set of model parameters. Moreover, in Eq. (1)

represents the member at time

of a daily vector stochastic chain

of i.i.d. vector innovations

with coordinates

related to days and hours. By definition the

vector stochastic variables have their marginal (w.r.t. daily coordinates

d) joint (w.r.t. intraday coordinates

h) density distributions

all equal to a fixed

. This

will be chosen as a 24-variate Gaussian distribution

, where

and

are (vector) mean and (matrix) covariance of the distribution. Thus in this vector notation

can represent also one

N-variate (in the daily sense) draw from the chain

, driven by a i.i.d. Gaussian noise

which yet includes intraday structure. Incidentally, it can be noticed that the model in Eq. (1) includes for a suitable form of

the possibility of regressing one day’s hour

on the same hour

(only) of

past days, i.e. independently from other hours as

where

are now scalar stochastic variables and

, an approach occasionally used in the literature. Seen as a restriction of Eq. (1), this `independent hours’ scalar model is easier to handle than the full vector model of Eq. (1), but it is of course less accurate. In contrast, the full vector model can take into account both intraday and interday dependencies, and allows for a complete panel analysis of data, cross-sectional and longitudinal, coherent with the microeconomic mechanism which generates the data. Commonly used forms of

are those linear in most of the parameters, like

where

are the matrices of coefficients and

is a vector nonlinear function. If

is linear in the

as well, a vector AR(

) model (VAR(

)) is obtained, like for example the

Gaussian VAR(1) model

For VAR(

) models the Box-Jenkins model selection procedure can be used to select optimal

and to estimate the coefficients.

In the literature, it is however univariate (i.e. scalar) autoregressions directly on the hourly series

[

19,

20], more or less nonlinear and complicated [

21,

22], which are applied most often. Noticeably, the information structure implicitly assumed by univariate models is the typical causal chain in which prices at hour

h depend only on prices of previous hours. On one hand researchers are aware that this structure doesn’t correspond to typical DAM prices information structure [

23], but on the other hand vector models are often considered impractical and heavier to estimate and discuss, especially before the arrival of large neural network models. This issue led first to estimate the data as 24 concurrent but independent series like in Eq. (2), then to the introduction of vector linear autoregressions like that in Eq. (3) [

24], maybe using non-Gaussian disturbances distributions like in [

25] (in this case multivariate Student’s distributions). In the case of models like the VAR(1) of Eq. (3), for each of the

lags a matrix of

parameters (besides vector means and matrix covariances of the innovations) has to be estimated and interpreted. Adding lags is thus computationally expensive and makes the interpretation of the model more complicated, and weakens stability, but in contrast few lags imply short term memory in term of days, i.e. quickly decaying autocorrelation. Seasonality and nonlinearity (like fractional integration) can be further added to these vector regressions [

26], making them able to sustain a longer term memory. A parallel line of research which uses a regime switching type of nonlinearity in the scalar autoregression setting (discussed at length in [

27]) does not concentrate on long term memory but can result in an even more satisfactorily modeling of many DAMs key phenomena like concurrent day/night seasonality and price spiking.

Point forecasting is straightforward with vector models in the form of Eq. (1) as

where

represents the estimated parameter set. In turn, Eq. (4) allows for defining (conditional) forecast vector errors as

on which scalar error functions

can be defined.

As to probabilistic forecasting, it should be noted that the function

in Eq. (1) induces a relationship between

and

that can be written as a conditional distribution

Besides by using stochastic equations like Eq. (1), vector autoregression models can thus also be directly defined by assuming a basic conditional probability distribution like that in Eq. (6). When based on a distribution conditional on some of their variables, probabilistic models are called

discriminative.

In contrast, when defined by means of the full joint distribution like

probabilistic models are called

generative [

28,

29,

30]. The relationship in Eq. (6), often obtained only numerically, can be used for probabilistic forecasting.

Notice that in the 0-lag case, i.e. for

, the set

is empty, and Eq. (1) becomes the Gaussian VAR(0) model

(where a possible constant is omitted). The corresponding probabilistic version of this model, i.e. Eq. (6) specialized according to Eq. (8), becomes the product of factors

In this case the defining distribution is unconditional, and the probabilistic model is both of discriminative and generative type. Estimation becomes probability density estimation. The point forecast becomes equal to

at all days. Probabilistic forecasting is the distribution itself. Both point and probabilistic out-of-sample forecasts are unconditional and based on past values of variables only in the sense that past values shape the distribution during the estimate phase. More in general, in a generative model errors cannot even be defined, and the Box-Jenkins model selection and estimation procedure, which relies on errors, cannot be applied. Notice that in the generative case a sample from the modeled chain includes

variables only, neither more or less, differently from the discriminative case. Generative models are clearly different from discriminative models, and this is probably why their are seldom considered by econometricians.

Finally, it is interesting to compare the realized dynamics for N days implied by probabilistic discriminative models like that in Eq. (6) with the dynamics implied by the VAR(0) model in Eq. (9). Whereas in the former, at each given day d, the next day vector is obtained by sampling from a marginal distribution that changes each day, obtained by feeding the last sampled value back to the distribution, in the latter the sampled distribution never changes. The VAR(0) model is uncorrelated from the point of view of interday dynamics, whereas it remains correlated in intraday dynamics. In contrast, in the case of the generic generative model of Eq. (7), both intraday structure and interday dynamics can be interesting. Based on this point of view, generative models that originate factorized dynamics (like the VAR(0) model and the mixtures which will be introduced next) will be henceforth called uncorrelated, whereas generative models which interday dynamics is more interesting (like the VHMMs) will be called correlated. It will be shown that both types, uncorrelated and correlated, can be in any case very useful for DAM market modeling.

3. Uncorrelated Generative Vector Models, VMs and Clustering

By Eq. (9) the VAR(0) model is defined in distribution as

. Estimation of this model on the data set

means estimating a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean vector

of coordinates

and symmetric covariance matrix

of coordinates

. Parameter estimation is made by maximizing the likelihood

L obtained multiplying Eq. (9)

N times, or maximizing the associated loglikelihood LL. The parameters can be thus be obtained analytically from the data, and since the problem is convex this solution is unique. Once

has been estimated, estimated `hourly’ univariate marginals

and `bi-hourly’ bivariate marginals

can be analytically obtained by partial integration of the distribution. In addition, for a generic market day, i.e. a vector

,

and

can define a distance measure

in a 24 dimensions space from

to the center

of the Gaussian of Eq. (9) as

where the superscript

indicates the inverse and the superscript ′ indicates the transpose.

is called Mahalanobis distance [

31]. This measure will be used later.

The VAR(0) model can become a new stochastic chain after replacing its driving Gaussian distribution with a driving Gaussian mixture, i.e., after changing its innovations sector, making it more complex, i.e., a VM. An

S-component VM is thus a generative dynamic model defined in distribution as

where

is an abbreviated notation for

[

32]. The

S extra parameters

subject to

are called mixing parameters or weights. Like the VAR(0), the VM is a probabilistic generative model, of 0-lag type, uncorrelated in the sense that it generates an interday independent dynamics, unlimited with respect to maximum attainable sequence length. In Eq. (11) the

subscript is there to remark its dynamic nature, since mixture models are not commonly used for stochastic chain modeling, except possibly in GARCH modeling (see for example [

33]). A VAR(0) model can thus be seen as a one-component

VM. For

the distribution in Eq. (11) is multimodal, and maximization of the LL can be made in a numeric way only, either by Montecarlo sampling or by the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm [

15,

34]. Since EM can get stuck into local minima, multiple EM runs have to be run from varied initial conditions in order to be sure to have reached the global minimum. Means and covariances of the

S-component VM can be computed in an analytic way from means and covariances of the components. For example, in the

case in the vector notation the mean is

and in coordinates the covariance is

Hourly variance

is obtained for

in terms of component hourly variances

and

as

The mixture hourly variance is thus the weighted sum of component variances plus a correction term which is similar to covariance in the case of a weighted sum of two gaussian variables. Based on the component variances, in analogy with the distance defined in Eq. (10) a number

S of Mahalanobis distances

can be now associated to each data vector

. In Eq. (11) the weights can be interpreted as probabilities of a discrete hidden variable

s, i.e., as a distribution

over

s.

An estimated VM implicitly clusters data, in a probabilistic way. In machine learning, clustering, i.e., unsupervised classification of vector data points called evidences into a predefined number

K of classes, can be made in either a deterministic or a probabilistic way. Deterministic clustering is obtained using algorithms like K-means [

35], based on the notion of distance between two vectors. K-means generates

K optimal vectors called centroids and partitions the evidences into

K groups such that each evidence is classified as belonging only to the group (cluster) corresponding to the nearest centroid in a yes/not way. Here `near’ is used in the sense of a chosen distance measure, often called linkage. In this paper, for the K-means analysis used in the Figures the Euclidean distance linkage is used. Probabilistic clustering into

clusters can be obtained using

S-component mixtures in the following way. In a first step the estimation of a S-component mixture on all evidences

finds the best placement of means and covariances of

S component distributions, in addition to

S weights

, seen as unconditional probabilities

. Here best is intended in terms of maximum likelihood. The component means are vectors that can be interpreted as centroids, the covariances can be interpreted as parts of distance measures from the centroids, in the Mahalanobis linkage sense of Eq. (10). In a second step, centroids are kept fixed. Conditional probabilities

called responsibilities are then computed by means of a Bayesian-like inference approach which uses a single-point likelihood. In this way, to each evidence a probability

of belonging to one of the clusters is associated, a member relationship which is softer than the yes/not membership given by K-means. For this reason, K-means clustering is called hard clustering, and probabilistic clustering is called soft clustering. Being a mixture, an uncorrelated VM model can do soft clustering in a intrinsic way.

4. VMs as Hierarchical Regime Switching Models

In a dynamical setting, independent copies

of the mixture variable

s can be associated to the days, thus forming a (scalar) stochastic chain

ancillary to

. This suggests an econometric interpretation of VMs. Consider as an example the

model. Each draw at day

d from the two-component VM can be seen as a hierarchical two-step (i.e., doubly stochastic) process, which consists of the following sequence. At first, flip a Bernoulli coin represented by the scalar stochastic variable

with support

and probabilities

. Then, draw from (only) one of the two stochastic variables

,

, specifically from the one which

i corresponds to the outcome of the Bernoulli flip. The variables

are chosen independent from each other and distributed as

. If

is the support of

, the VM can thus be seen as the stochastic nonlinear time series

a vector Gaussian regime switching model in the time coordinate

d, where the regimes 1 and 2 are formally autoregressions without lags, i.e., of VAR(0) form. A path of length

N generated by this model consists of a sequence of

N hierarchical sampling acts from Eq. (15), which is called ancestor sampling. In Eq. (15) the r.h.s. variables

,

,

are daily innovations (i.e., noise generators) and the l.h.s. variables

,

are system dynamic variables. Even though the value of

is hidden and unobserved, it does have an effect on the outcome of observed

because of Eq. (15). Notice that if the regimes had

, for example

like the VAR(1) model of Eq. (3), the model would have been discriminative and not generative. It would have had a probabilistic structure based on the conditional distribution

, like most regime switching models used in the literature [

20]. Yet, it wouldn’t be capable to do soft clustering.

Generative modeling requires at first to choose the joint distribution. The hierarchical structure interpretation of Eq. (15) implies that in this case the generative modeling joint distribution is chosen as the product of factors of the type

From Eq. (16) the marginal distribution of the observable variables

can be obtained by summation

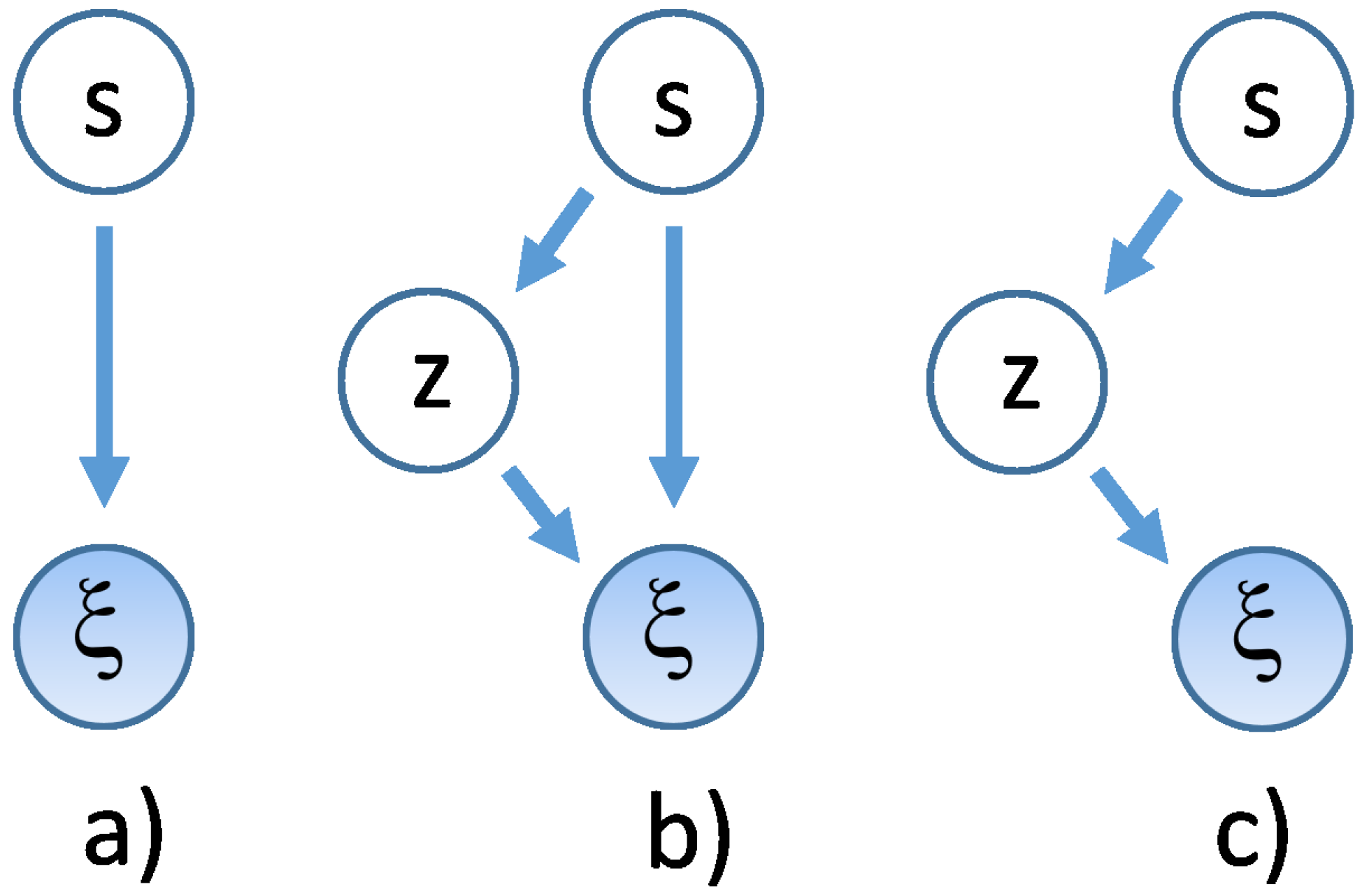

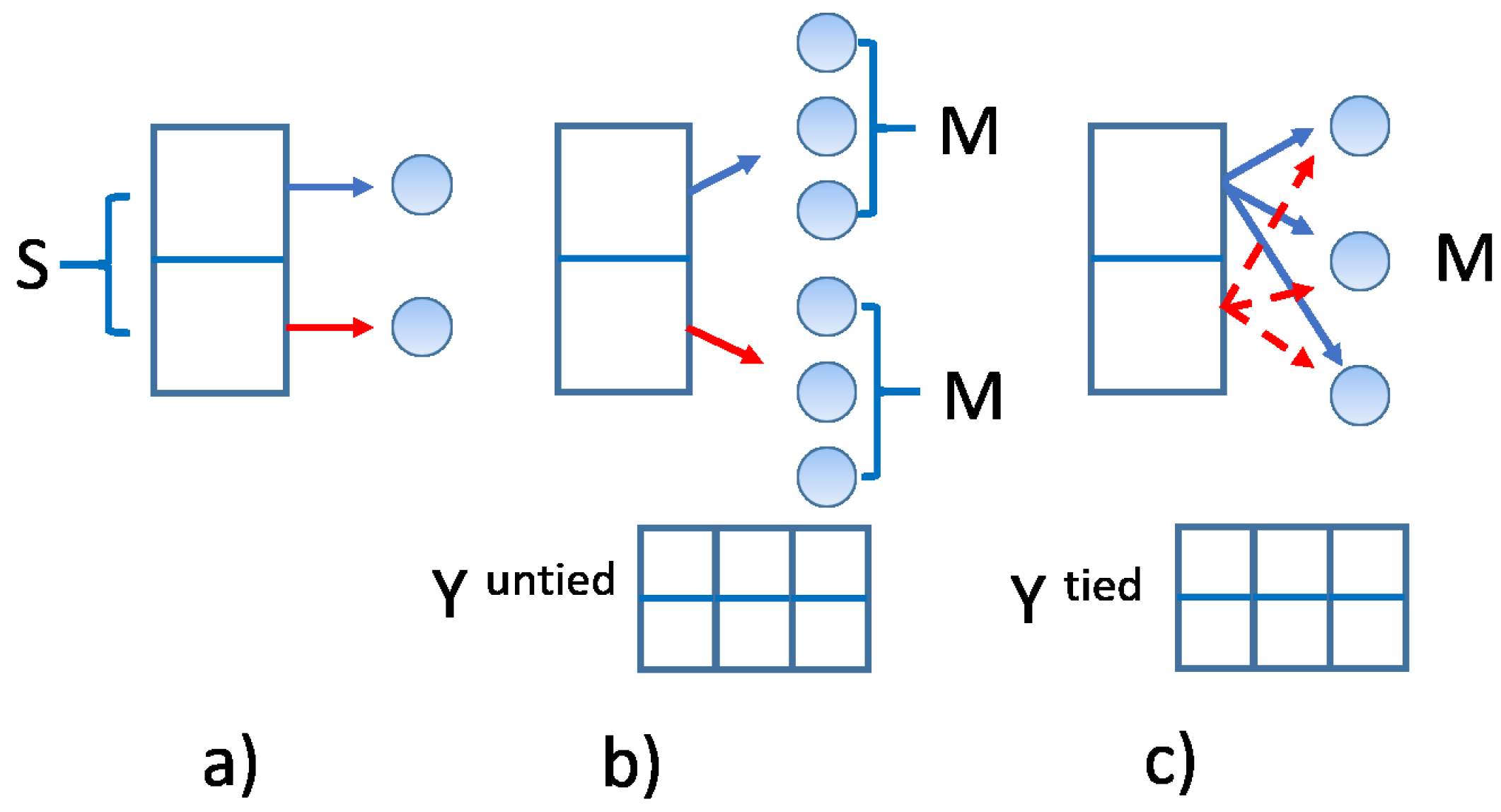

A graphic representation of a VM model is shown in

Figure 1, where model probabilistic dependency structure is shown in such a way that the dynamic stochastic variables, like those appearing on the l.h.s. of Eq. (15), are encircled in shaded (observable type) and unshaded (unobservable type) circles, and linked by an arrow that goes from the conditioning to the conditioned variable. This structure is typical of Bayes Networks [

15]. Specifically, in panel a) of

Figure 1 the model of Eq. (15) is shown.

It will be now shown that models like that in

Figure 1 a) can be made deeper, like those

Figure 1 b) and c), and that this form is also necessary for a parsimonious form of modeling in VHMMs to be discussed in Sec.

Section 7. Define the depth of a dynamic VM as the number

J of hidden variable layers plus one, counting in the

layer as the first of the hierarchy. A deep VM can be defined as a VM with

, i.e., with more than two layers in all, in contrast with the shallow (using machine learning terminology) VM of Eq. (15). A deep VM is a hierarchical VM, that can be also used to detect cluster-within-clusters structures.

As an example, a

VM can be defined in the following way. For a given day

d, let

and

to be again two scalar stochastic variables with

S-valued integer support

,

and same distribution

. Let

to be

S new scalar stochastic variables, all with same

M-valued integer support

,

, and with time-independent distributions

. Consider the following VM obtained for

and

:

where

In Eq. (18) the second layer variables

are thus described by conditional distributions

. This is a regime switching chain which switches among four different VAR(0) autoregressions. Seen the model as a cascade chain, at time

, a Bernoulli coin

is flipped at first. This first flip assigns a value to

. After this flip, one out of a set of two other Bernoulli coins is flipped in turn, either

or

, its choice being conditional on the first coin outcome. This second flip assigns a value to

. Finally, one Gaussian out of four is chosen conditional on the outcomes of both the first and the second flip. Momentarily dropping for clarity the subscript

from the dynamic variables and reversing to mixture notation, the observable sector of this partially hidden hierarchical system is expressed in distribution as a (marginal) distribution in

, with a double sum on hidden component sub-distribution indexes

The number of components used in Eq. (20) is

. Notice again that the Gaussians are here conditioned on both second and third hierarchical layer

i and

j indices. See panel b) of

Figure 1 for a graphical description. Intermediate layer information about the discrete distributions

can be collected in a

matrix

which supplements the piece of information contained in

. In this notation Eq. (20) becomes

Notice also that this hierarchical structure is more flexible than writing the same system as a shallow flip of an

faces dice, because it fully exposes all possible conditionalities present in the chain, better represents hierarchical clustering, and allows for asymmetries - like having one cluster with two subclusters inside and another cluster without internal subclusters. In addition to the structure of Eq. (18), another more compact

hierarchical structure, a useful special case of Eq. (18), is

with the same

f as in Eq. (19). This system has distribution (in the simplified notation)

or, for

,

where

and

, and where now the Gaussians are conditioned to the next layer only. See panel c) of

Figure 1 for a graphical description. This chain can also model a situation in which two different mixtures of the same pair of Gaussians are drawn. In this case each state

corresponds to a bimodal distribution

, unlike the shallow model. This structure, which is a three-layer two-component regime switching dynamics from an econometric point of view, will be specifically used later when discussing hidden Markov mixtures.

7. Autocorrelated Vector Models and VHMMs

Dynamic econometrics requires models which have a causal temporal structure This is usually automatically enforced by defining them by autoregressions like that in Eq. (1), i.e., in a discriminative way. In fully probabilistic (i.e., generative) modeling such a structure must be directly imposed on the joint distribution which defines the model. One possible approach to enforce a causal structure in a generative model is that of leaving to the hidden dynamics the task of carrying the dynamics forward in time, whereas the observable dynamics is maintained conditionally independent on itself through time. This is what hidden Markov models are designed for [

40]. Henceforth, in order to discuss this approach, the symbol for the set of

variables

will be shortened to

. This choice is intended for both keeping notation light and to remark the specific way in which the dynamic generative approach models the variables, that is all at once. In principle, if the data series has

N variables,

.

A vector Gaussian hidden Markov mixture model is defined in distribution as

for

, and

for

(i.e.,

) [

14]. In Equations (29) and (30)

is often loosely called prior. In Eq. (29) all

will be chosen equal, which makes the system time-homogeneous. The conditional distribution

will be instead chosen as a convex combination of Gaussians, as explained in the following. For this system stationarity is defined as that condition in which

. A time-homogeneous system which has reached stationarity has hence the property that

for all

d, a useful property. It should be yet also recalled out that homogeneity in time doesn’t guarantee stationarity. Notice the overall form

of this model, like in the VM case. The observable joint (w.r.t. intraday dynamics) marginal (w.r.t. observable variables) distribution

is obtained from Eq. (29) by summing over the support of all

, which makes this model a generalized vector mixture. For example, by summing on

Eq. (30) one recovers the observable static

S-component mixture

used to define the shallow (i.e., not-hierarchical) VM. Since the

have a discrete support, it is possible to set up a vector/matrix notation for the daily hidden marginals

and for the constant transition matrix

of entries

, where

and

, with

and

(columns sum to one). In this notation, for example for

, the dynamics of the hidden distribution becomes a multiplicative rule of the form

which starts from an initial distribution

. Under

A, after

n steps forward in time,

becomes

where the superscript

n on

A indicates its n-th power. Time-homogeneous hidden Markov models can be hence be considered `modular’ because, for a given

, the hidden dynamics of

is completely described by the prior

and a single matrix

A which repeats itself as a module for

times.

This means that, after an estimate on the data, a global A will encode information from all interday transitions, which are local in time. To highlight this feature, sometimes a subscript can be attached to A, like for example .

The number of parameters required for the hidden dynamics of a hidden Markov model is thus in all, usually a small number. To this number, a number of parameters for the observable sector should be added for each state. If Gaussians are used, this number can become very large. Hence, the total number of parameters depends in general mainly on the probabilistic structure of the observable sector of the model. The basic idea behind VHMMs is to take the distribution of the observable dynamics as a vector Gaussian mixture, i.e., to piggyback a VM module onto a hidden Markov dynamics backbone, taking also care not to end up with too many Gaussians. This will allow obtaining correlated dynamic vector generative models which are deep and rich in behavior but at the same time parsimonious in the number of parameters, and which can forecast in a more structured way than VMs.

Consider at first the shallow case in which

. In this case, Eq. (29) implies using

S Gaussians in all, as many as the states. Ancestor sampling means picking up one of these Gaussians from this fixed set at each time

d. This is pictorially represented in panel a) of

Figure 15, were one module of the model is shown with two hidden states emitting one Gaussian each. This model is the correlated equivalent of the (uncorrelated) shallow VM of Eq. (15), which was represented in

Figure 1 a).

The shallow model can be extended by associating one

M-component Gaussian mixture to each of the

S hidden states, for

S discrete distributions in all, each hidden state thus supporting a vector of

M weights and a

M-components mixture distribution. This configuration is represented in panel b) of

Figure 15, where the two hidden states emit three Gaussians each. The required weight vectors can be gathered into a matrix

with

non-negative entries, each row of which sums to 1. This is equivalent to using on each day a module of the

deep VM of Eq. (18), which was represented in

Figure 1 b). This means that

corresponds to the matrix

W of Eq. (21) and that the Gaussians

of this model are conditioned both on the intermediate and on the top layer of the hierarchy. This configuration requires

Gaussians in all to be estimated, potentially a lot, each with

parameters where

, besides

A,

and

.

A more parsimonious model can be obtained by choosing to use

M Gaussians instead of

. This is obtained by selecting

M Gaussians and associating to each of the

S hidden states an

s-dependent mixture from the fixed pool of these

M Gaussians, in a tied way, in the same way as the

deep VM of Eq. (23) represented in

Figure 1 c) does. Information about the mixtures can be represented by a

matrix

, formally similar to

, but related to a different interpretation. The Gaussians now have form

since they are conditioned on the next layer only. This setting is represented in panel c) of

Figure 15, where each of the two hidden states is linked to the same triplet of gaussians. Being able to tie a hierarchical mixture is therefore all-important for parsimony, because in the tied case one can have a large number of hidden states but a very small number of Gaussians, maybe two or three, and an overall number of parameters comparable to that of a VAR(1) which has the same memory depth. This last model will be called

tied model in contrast with the model with

Gaussians, which will be called

untied model. The discussed tied model is the smallest model that contains all vector, generative, hidden state features in a fully correlated dynamic way.

From an econometric point of view, the untied and tied VHMM models are deep regime switching VAR(0) autoregressions, with stochastic equations given by Eq. (18) and Eq. (23), where

f of Eq. (19) is replaced with

In Eq. (36)

is the stochastic matrix associated to the transition matrix

A of Eq. (33), i.e., the stochastic generator of the hidden dynamics. Therefore in these models the hidden dynamics evolves according to a linear multiplicative law for the innovations, whereas the overall model results nonlinear. Since the underlying hidden Markov model is modular, it is possible to write in probability density the representative module of these models. For the untied model this module is

having used a mixed notation and having compressed in

(i.e., in

) the `static dynamics’ of the

, i.e., the parametrization of the intermediate layer. Eq. (37) corresponds to the one-lag regime switching chain of Eq. (18). For the tied model,

where

are the entries of

, i.e., the piece of information about the intermediate layer. This dynamic probabilistic equation corresponds to the stochastic chain of Eq. (23). Hence, suitable regime switching VAR(0) autoregressions can have all the properties of the generative correlated VHMM models, clustering capabilities included. One could also say that Equations (37) and (38) are the machine learning,

vector generative correlatives of the vector discriminative dynamics of Eq. (1), which in contrast has no hidden layers, it is based on additive innovations, and can have

. Noticeably, the hidden stochastic variables

of the intermediate layer of the untied and tied models don’t have an autonomous dynamics, like

has. But, if needed, they can be promoted to have it as well without changing the essential architecture of the models. Moreover, being Markovian, these dynamic models incorporate a one-lag memory, controlled by

A. But, if needed, this memory can be in principle extended to more lags, by replacing the first order Markov chain of the hidden dynamics with an higher order Markov chain.

Finally, from a simulation point of view, each draw from these systems will consist of one joint draw of all variables at once. This is typical of generative models. From a more econometric point of view, this one draw can be seen as a sequence of draws from , local in time, each causally dependent on the preceding one only, and with a deep cascading component on their top at each time.

9. Correlated Models on Data

Correlated deep models like the untied and the tied VHMMs overcome the structural limit that prevents uncorrelated VMs to generate series with autocorrelation longer than 24 hours. In order to discuss this feature in relation to Alberta data, two technical results [

41] are first needed.

First, if the Markov chain under the VHMM is irreducible, aperiodic and positive recurrent, as usually estimated matrices

A with small

S ensure, then

Recalling Eq. (35), Eq. (40) means that after some time

n the columns of the square matrix

, seen as vectors, become all equal to the same column vector

. Second, at the same conditions and at stationarity, if

counts the number of times a state

has been visited up to time

n, then

i.e., the components of the limit vector

give the percent of time the state

j is occupied during the dynamics.

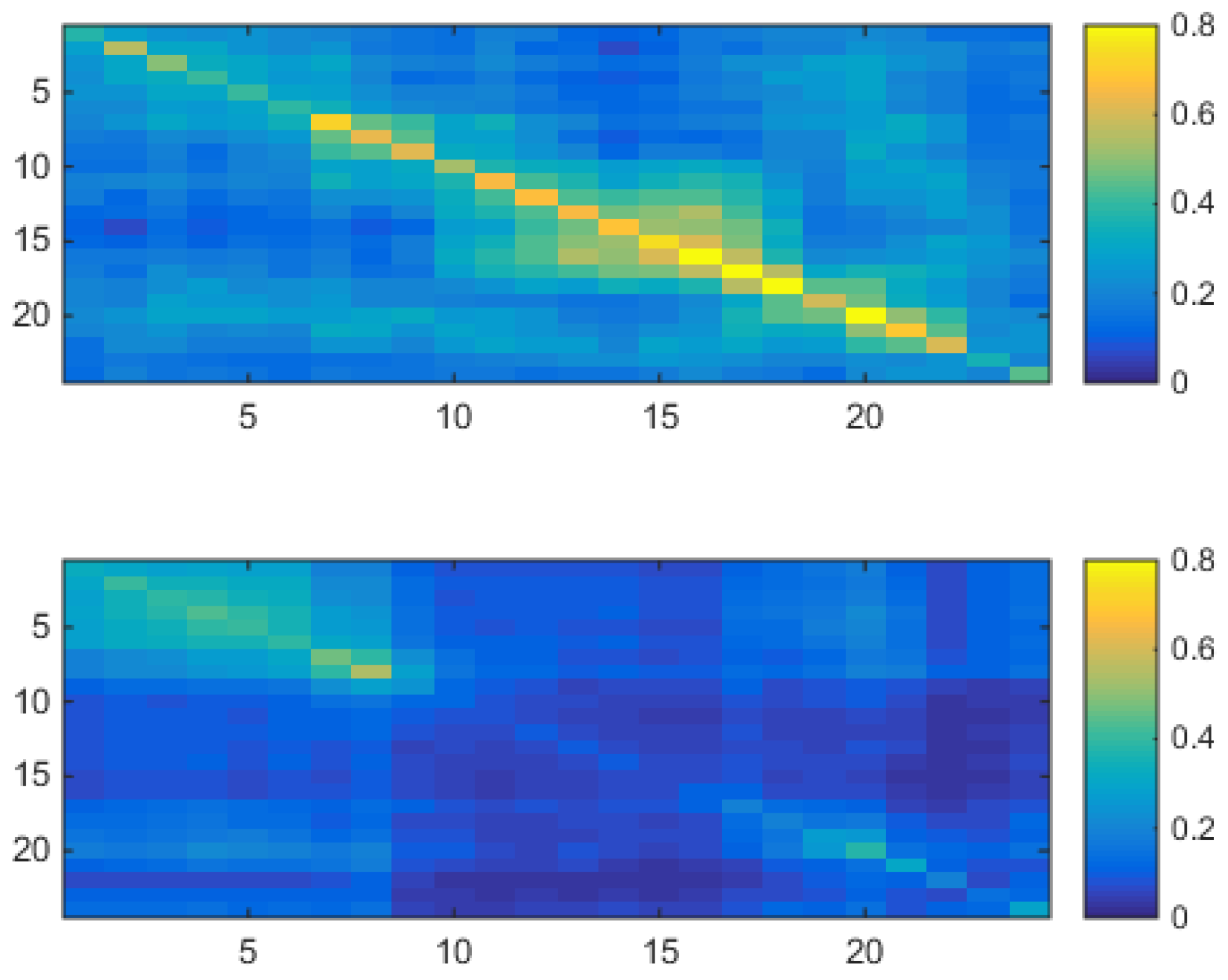

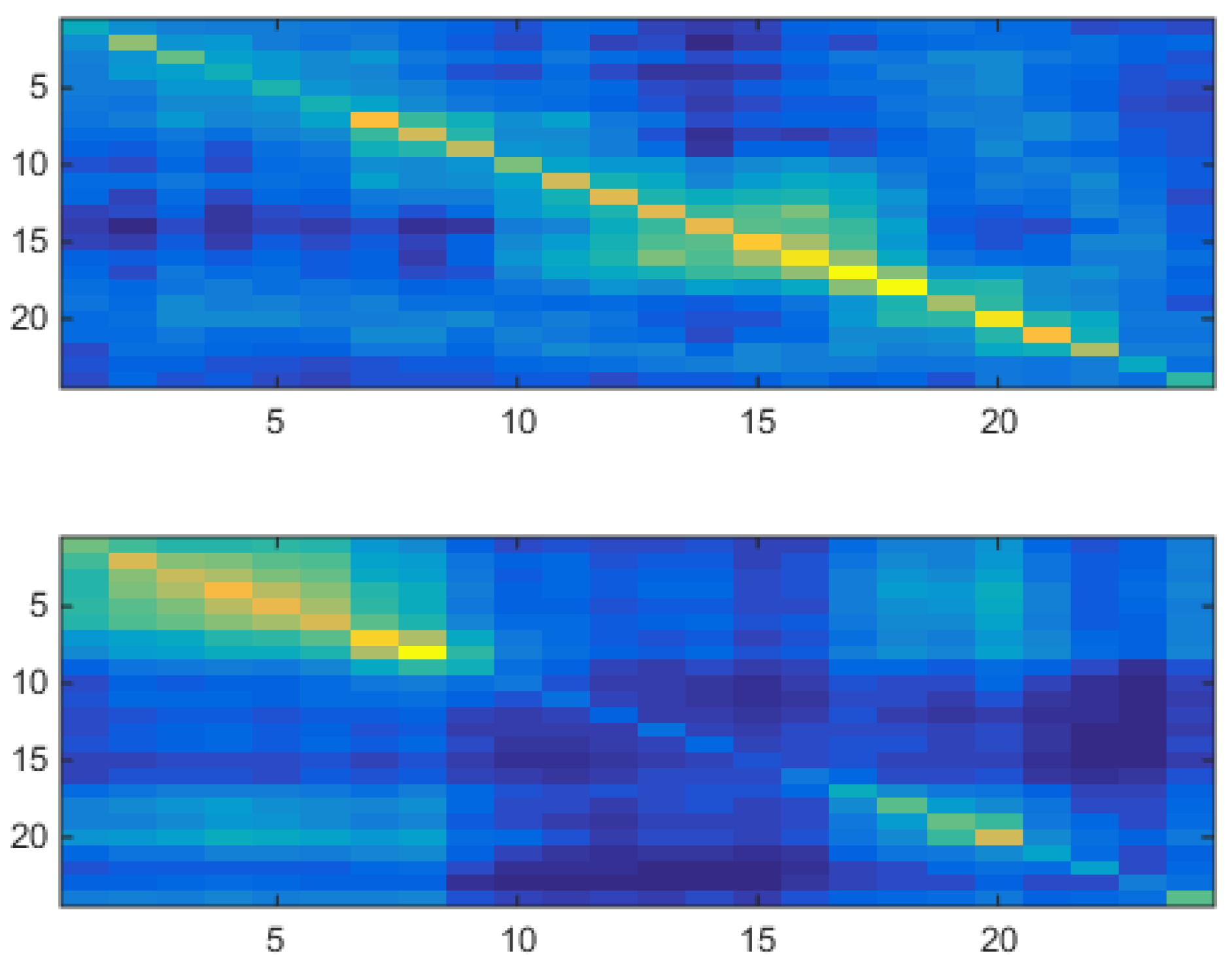

Figure 16 shows for a two-component

tied VHMM the two estimated covariance matrices of the model, to be compared with

Figure 9 for which a two-component uncorrelated shallow VM model was used.

The upper panel of

Figure 16 has an analog in the upper panel of

Figure 9. Both covariances have their highest values along their diagonal, very low values off-diagonal, and high values concentrated in the daily part. The lower panel of

Figure 16 has an analog in the lower panel of

Figure 9. Both covariances have their highest values along their diagonal, very low values off-diagonal, and high values concentrated in the night part. Namely, the correlated VHMM extracts the same structure as that extracted by the uncorrelated VM, i.e., a night/day structure.

Besides covariances and means another estimated quantity is

(weights of each hidden state are along columns). This means that, from the point of view of the tied model, each market day contains the possibility of being both night- or day-like, but in general each day is very biased towards being mainly day-like or mainly night-like. The last piece of information is contained in the estimated

(columns sum to one). After about

days

reaches stationarity becoming

As Eq. (40) indicates, this gives

, which means, in accordance with Eq. (41), that the system tends to spend about two thirds of its time on the first of the two states, in an asymmetric way.

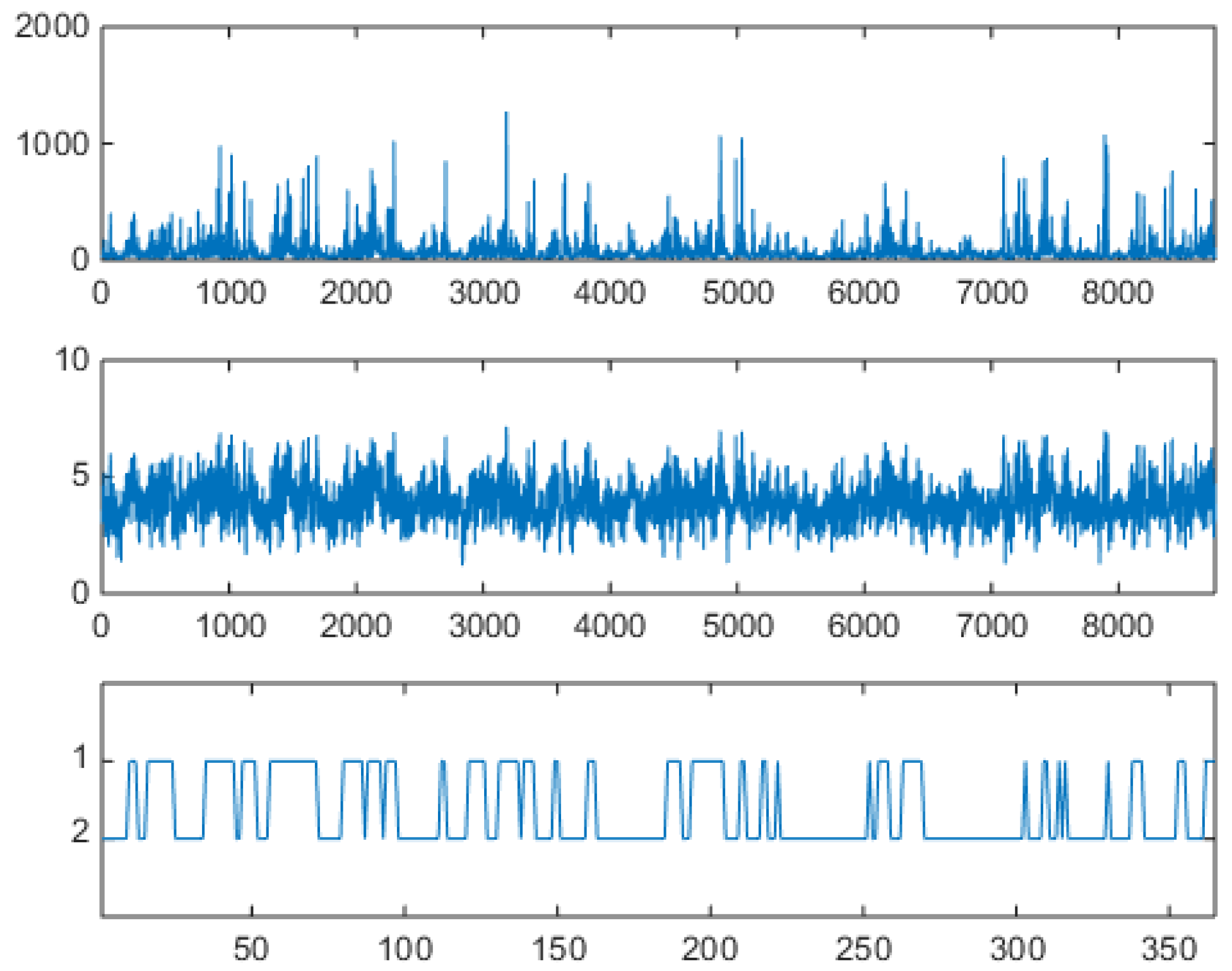

Once this information is encoded in the system, i.e., the parameters

are known by estimation, a yearly synthetic series (

) can be generated, which will contain the extracted features. The series is obtained by ancestor sampling, i.e., first by generating a dynamics for the hidden variables

using the first line of Eq. (23) with

(to be compared with Eq. (19)), then for each time

d by cascading through the two-level hierarchy of the last lines of Eq. (23) down to one of the two components. The obtained emissions (i.e., logprices and prices), organized in a hourly sequence, are shown in upper and middle panels of

Figure 17, to be compared both with

Figure 12 obtained with the shallow

VM and with the original series in

Figure 2.

The hourly series shows spikes and antispikes, but now spikes and antispikes appear in clusters of a given width. This behavior was not possible for the uncorrelated VM. The VHMM mechanism for spike clustering can be evaluated by looking at the lower panel of

Figure 17 where the daily sample dynamics

is shown in relation with the hourly logprice dynamics. Spiky, day-type market days are generated mostly when

. Look for example at the three spike clusters respectively centered at day 200, beginning at day 250, and beginning at day 300. Between day 200 and 250, and between day 250 and 300 night-type market days are mostly generated with

. Once in a spiky state, the system tends to remain in that state. Incidentally, notice that the lower panel of

Figure 17 is not a reconstruction of the hidden dynamics, because when the generative model is used for synthetic series generation the sequence

is known and it is actually not hidden. It should also be noticed that the VHMM logprice generation mechanism is slightly different from the VM case for a further reason too. In the VM case the relative frequency of spiky and not spiky components is directly controlled by the ratio of the two component weights. In the VHMM case each state supports a mixture of both components. The estimation creates two oppositely balanced mixtures, one mainly day-typed, the other mainly night-typed. The expected permanence time on the

state, given by

(i.e., by

), controls the width of the spike clusters. A blowup of the sequence of synthetically generated hours is shown in

Figure 18, to be compared with the VM results in

Figure 12 and the original data in

Figure 3.

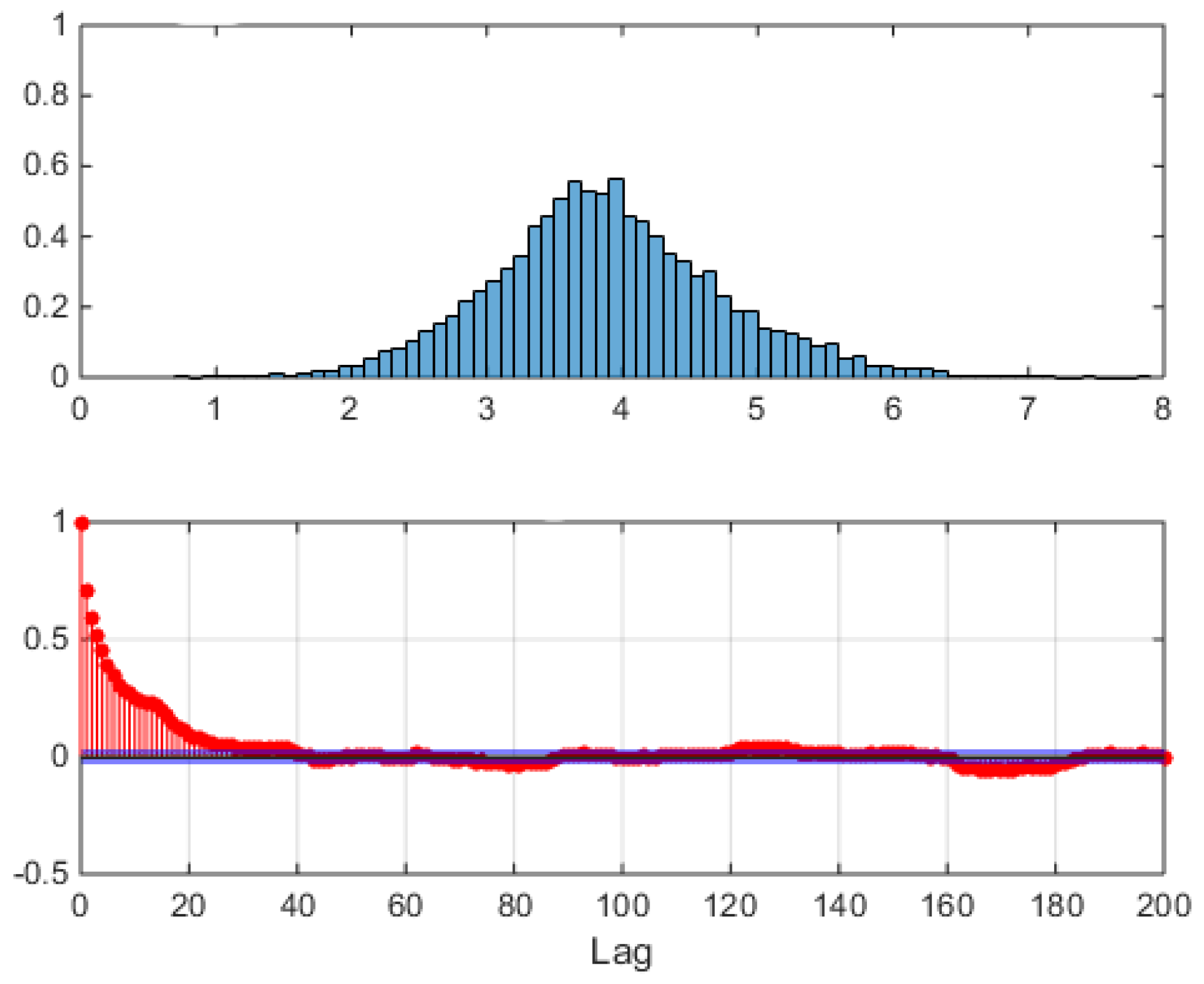

The aggregated, unconditional logprice sample distribution of all hours is shown in the upper panel of

Figure 19, where left and right thick tails remind the asymmetrically contributing spikes and antispikes, whose balance depends now not only on static weight coefficients but also on the type of the dynamics that

is able to generate.

In the lower panel of

Figure 19 the sample preprocessed correlation function is shown, obtained subtracting Eq. (27) from the hourly data, as in

Figure 14 (VM) and

Figure 4 (market data). Now the sample autocorrelation for the sample trajectory of

Figure 17 extends itself to hour 48, i.e., to 2 days, due to the interday memory mechanism. Not all generated trajectories will of course have this property, each trajectory being just a sample from the joint distribution of the model, which has peaks (high probability regions) and tails (low probability regions). An example of this varied behavior is shown in

Figure 20, where sample autocorrelation was computed on three different draws. The lag 1 effect is always possible, but it is not realized in all three samples, as can be seen in the lower panel of

Figure 20.

These results were discussed using machine learning terminology, but they could have been discussed using switching lag autoregressions terminology as well.

10. Conclusions

In this paper a method for modeling and reproducing electricity DAM price hourly series in their most important features is outlined, which bridges the two most common approaches to DAM prices modeling, the machine learning and the econometric approaches. From an econometric perspective the steps taken were: i) in a preliminary way, a multivariate vector autoregression approach replaced the more usual univariate autoregression approach, as it is becoming ever more common nowadays, ii) to a 0-lag multivariate linear autoregression, regime switching nonlinearity was added, showing that this addition is equivalent to using generative, static mixture models, which can get a depth dimension which can make them hierarchical), iii) hidden state hierarchical Markov mixture models added dynamics to the static scheme. Hence, the method can be summarized to be a vector hierarchical generative hidden state approach to DAM price data generation, at the crossroad between econometrics and machine learning.

In facts, by analyzing in detail the inner workings of mixture models and hidden Markov mixture models of the machine learning community, the paper shows how to recognize behind these models usual econometric VAR(0) regime switching autoregressions. This allows one to look at regime switching autoregressions as generative models that can do deep clustering and manage deeply clustered data, by assuming as basic data the daily vectors of hourly logprices. From this reinterpretation point of view, the paper also shows that simple regime switching autoregressions are able to encode intraday and interday mutual dependency of data at once, with a straightforward interpretation of all their parameters in terms of the market data phenomenology. All these features are very interesting for DAM prices modeling and DAM price scenario generation.

In [

12] it was pointed out that the econometricians and the CI people cultures’ `founding values’ are respectively interpretability and accuracy of models, and the two communities feel sometimes in conflict for that. In DAM price forecasting, linear autoregressions have been always easily interpreted, whereas neural networks started out as very effective black box tools. Indeed, linear autoregressions are in general not so much accurate in reproducing and forecasting fine details of DAM data, whereas neural networks can be very accurate and leverage complex structures. The vector hidden Markov mixtures discussed in this paper are probably an example of an intermediate class of models that are both accurate in dealing with data fine details, easy to interpret, not complex at all, sporting a very low number of parameters, and palatable for both communities. This approach is thus hoped to lead to a more nuanced understanding of price formation dynamics through latent regime identification, while maintaining interpretability and tractability, which are two essential properties for deployment in real-world energy applications. Looking ahead, it could thus become interesting to explore how the equivalent of the hierarchical mixture structure could be added to non-hmm, recurrent network dynamic backbones of current deep learning models.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the dynamic VM/regime switching models discussed in the text, with their probabilistic dependency structure. Dynamic stochastic variables are shown inside circles, shaded when variables are observable and unshaded when they are not observable. Arrows show the direction of dependencies among variables. a) Model of Eq. (15); b) Model of Eq. (18); c) Model of Eq. (23).

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the dynamic VM/regime switching models discussed in the text, with their probabilistic dependency structure. Dynamic stochastic variables are shown inside circles, shaded when variables are observable and unshaded when they are not observable. Arrows show the direction of dependencies among variables. a) Model of Eq. (15); b) Model of Eq. (18); c) Model of Eq. (23).

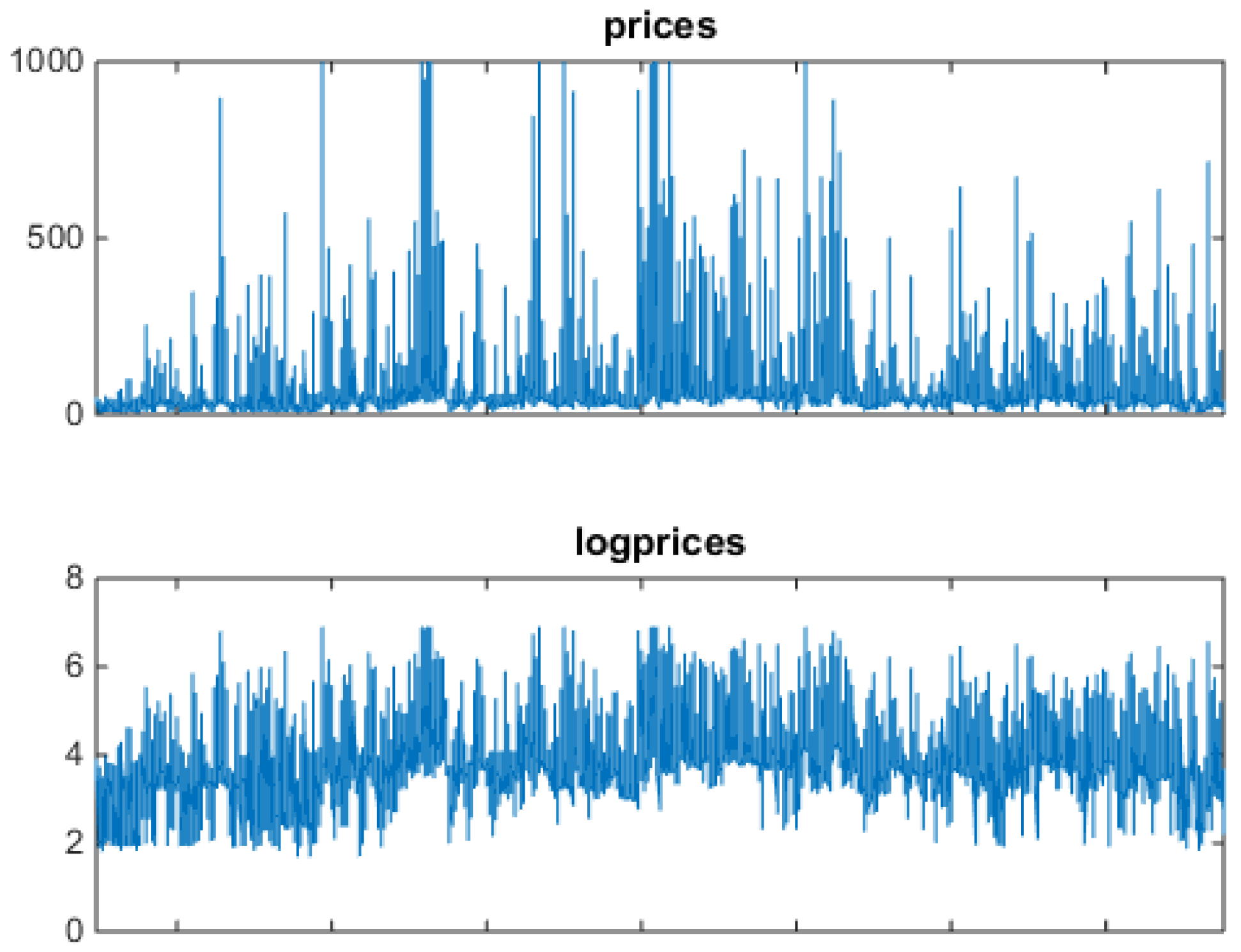

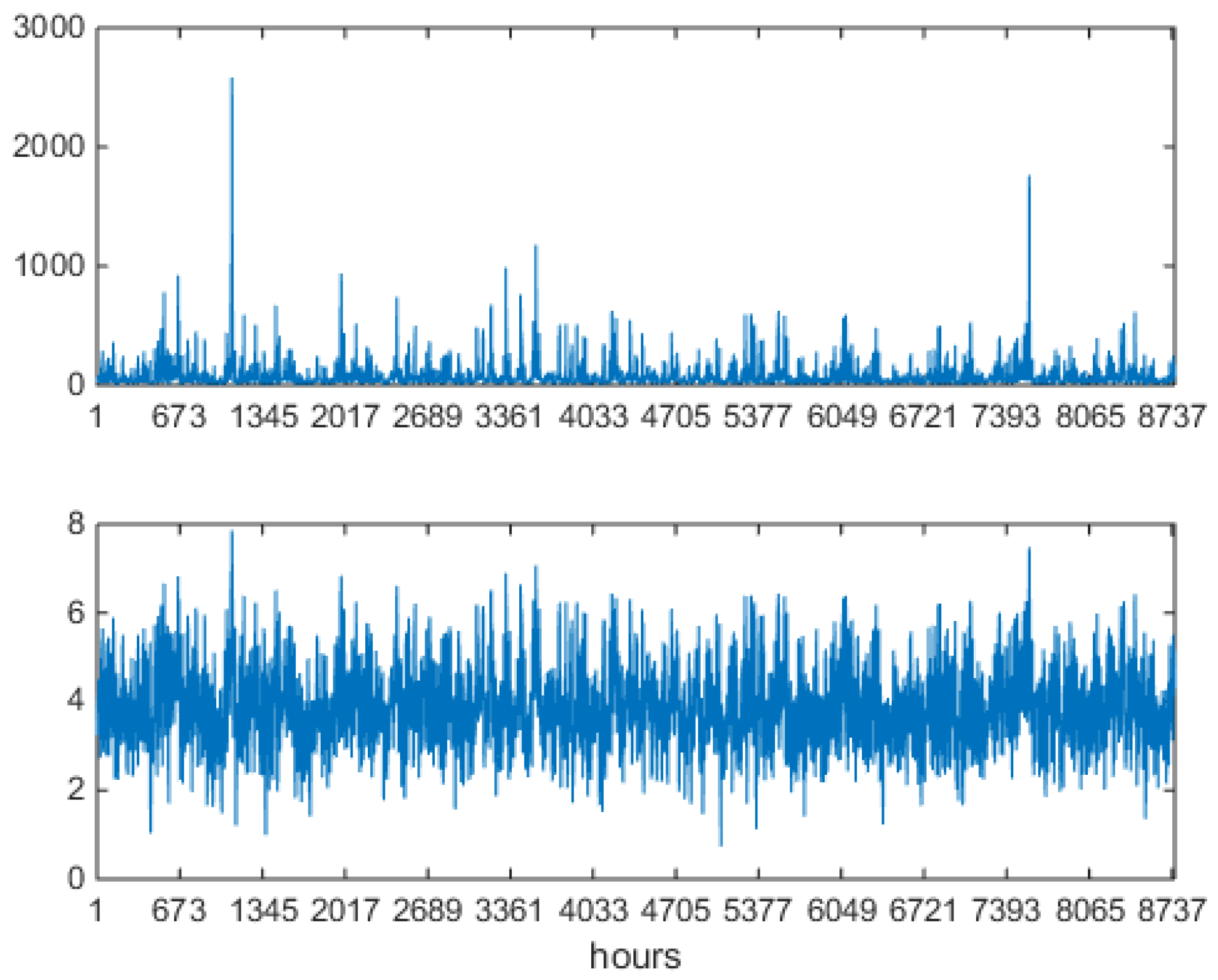

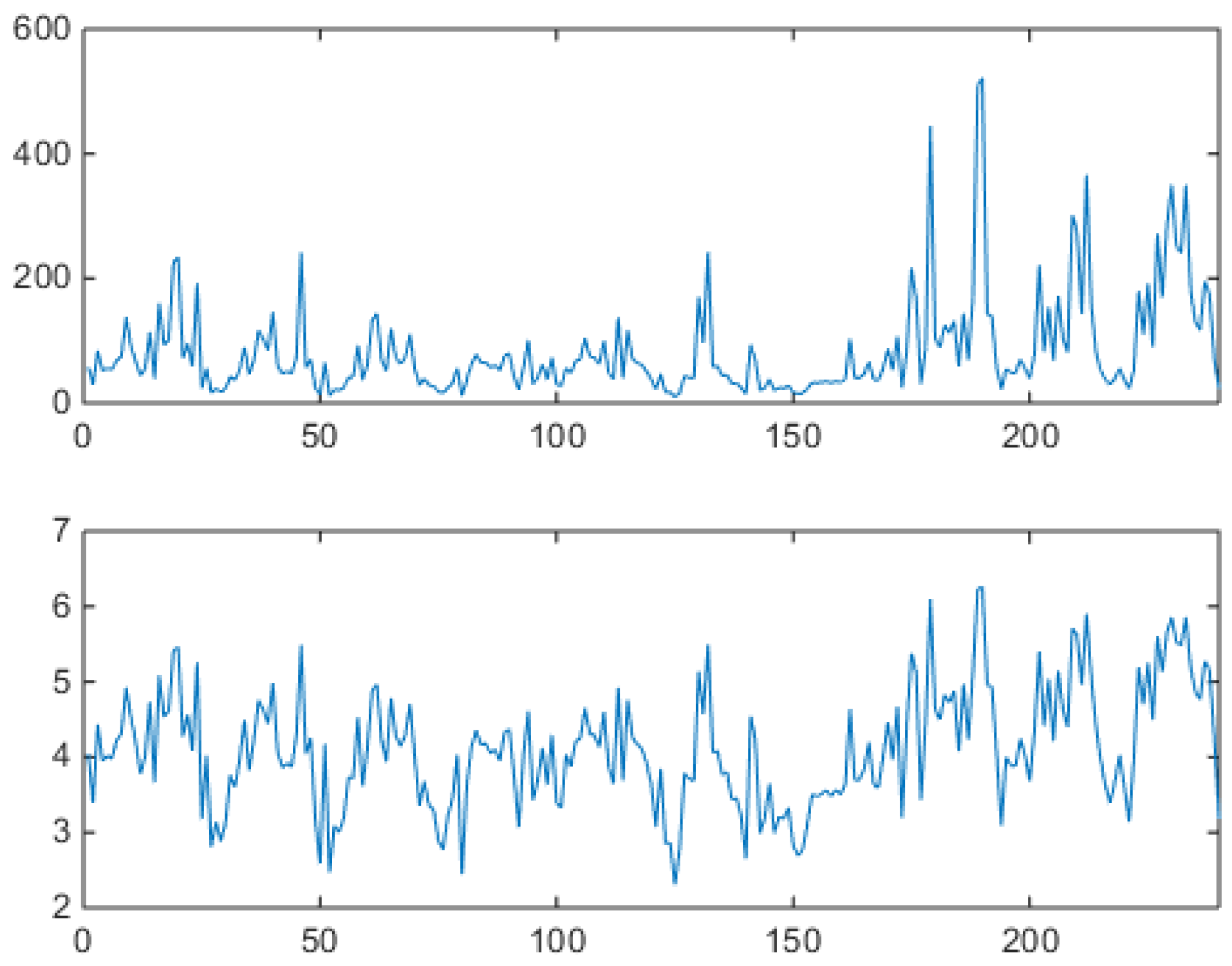

Figure 2.

Alberta power market data: one year from Apr-07-2006 to Apr-06-2007 of hourly data (8760 values). Prices in Canadian Dollars (C$) in the upper panel, and logprices in the lower panel. In this market, during this period, prices are capped at C$ 1000. Notice the frequent presence antispikes, better visible in the logprice panel.

Figure 2.

Alberta power market data: one year from Apr-07-2006 to Apr-06-2007 of hourly data (8760 values). Prices in Canadian Dollars (C$) in the upper panel, and logprices in the lower panel. In this market, during this period, prices are capped at C$ 1000. Notice the frequent presence antispikes, better visible in the logprice panel.

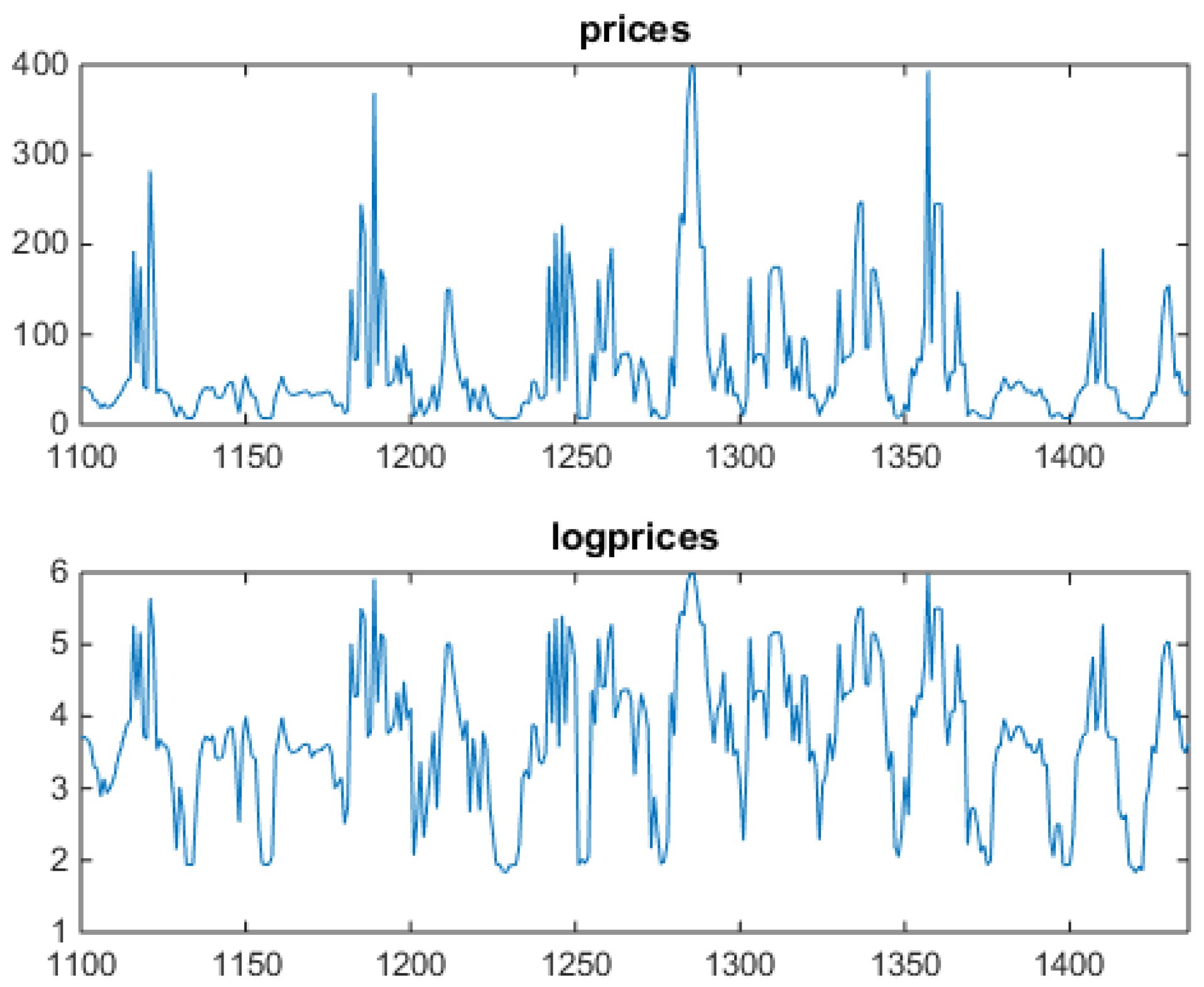

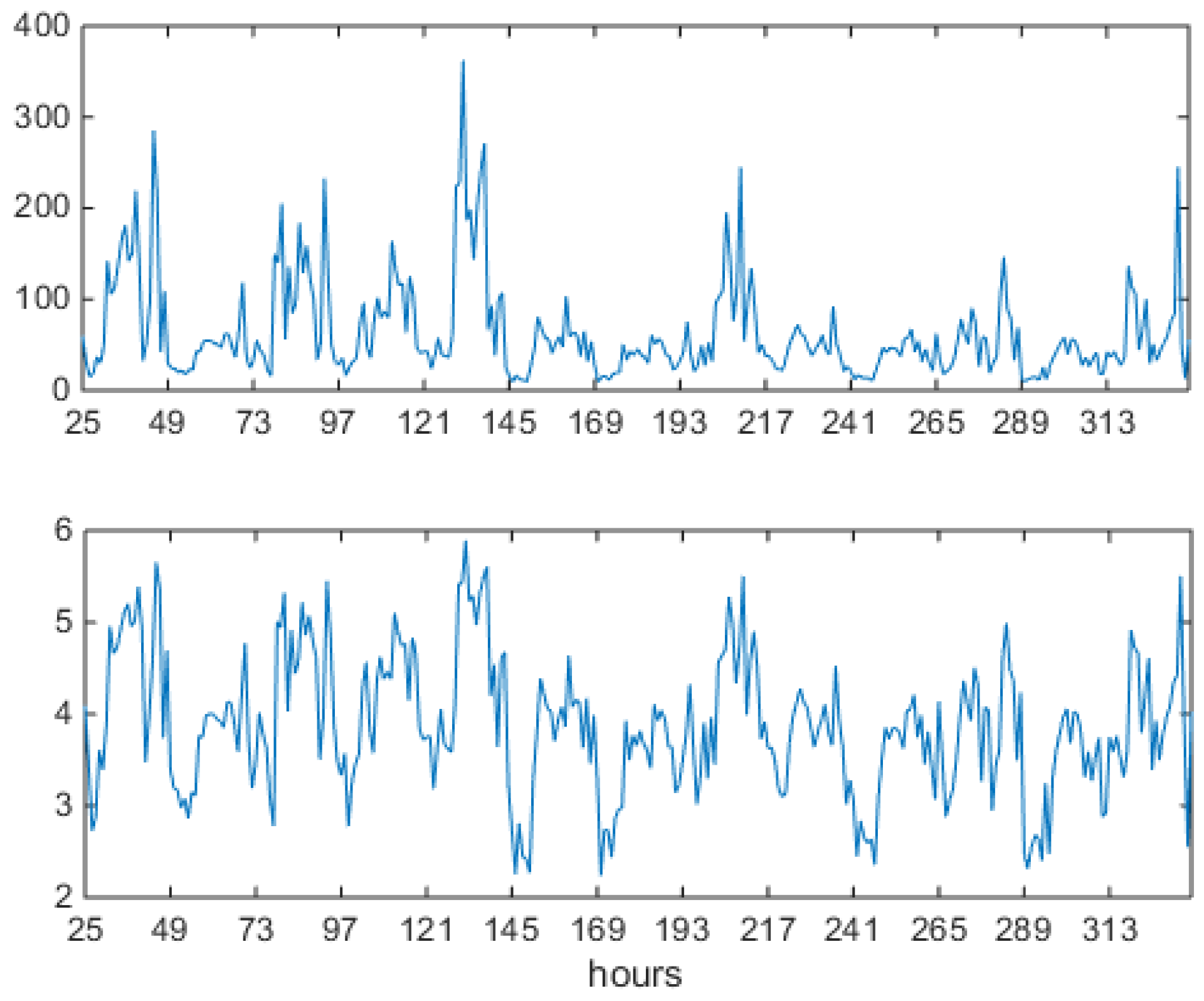

Figure 3.

Alberta power market data blowup: two weeks (336 values) of hourly price and logprice profiles. Prices in the upper panel, and log-prices in the lower panel. Spikes concentrate in central hours, never appear during night time. Antispikes never appear during daylight. On the x axis, progressive hour indexes relative to the data set.

Figure 3.

Alberta power market data blowup: two weeks (336 values) of hourly price and logprice profiles. Prices in the upper panel, and log-prices in the lower panel. Spikes concentrate in central hours, never appear during night time. Antispikes never appear during daylight. On the x axis, progressive hour indexes relative to the data set.

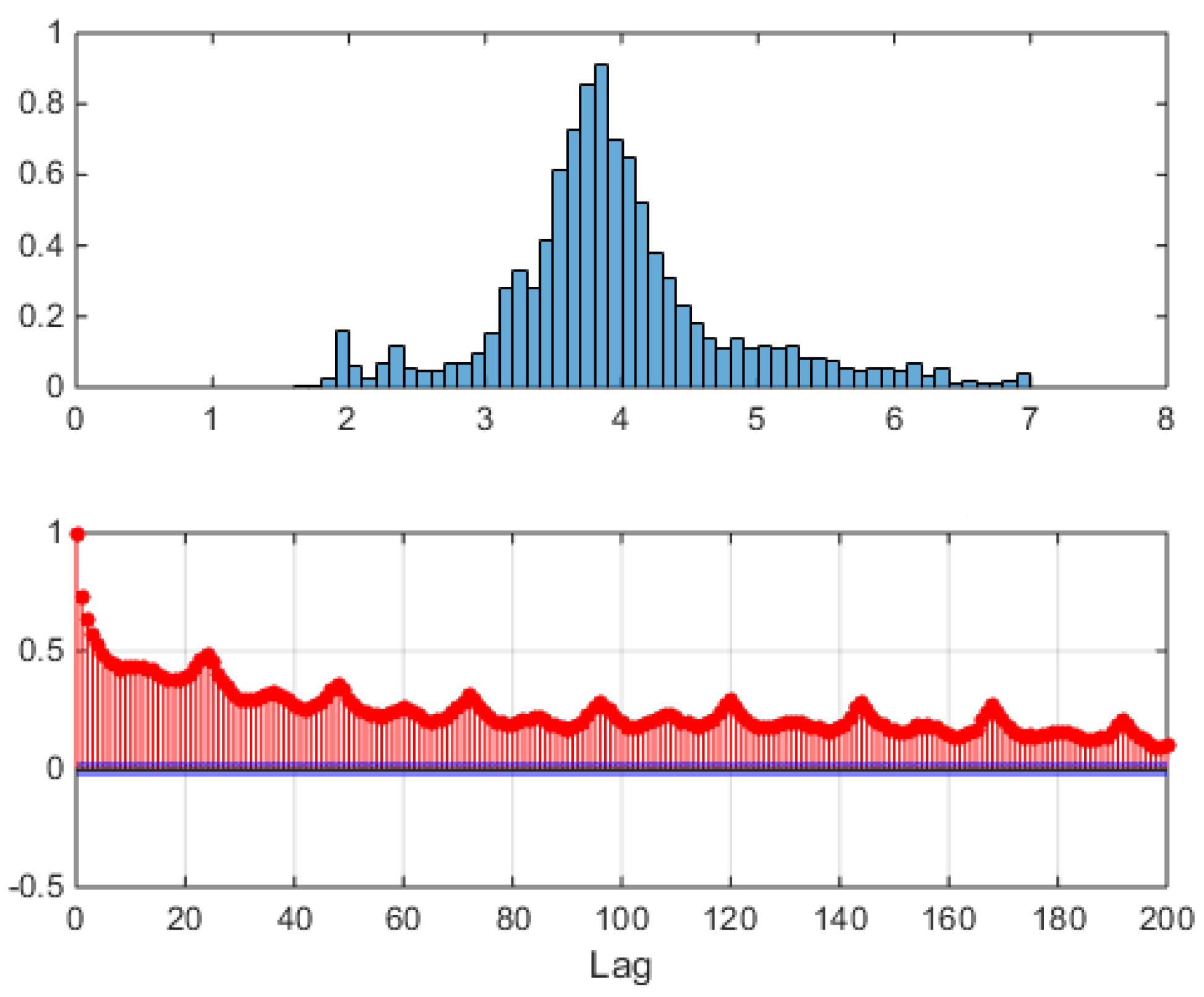

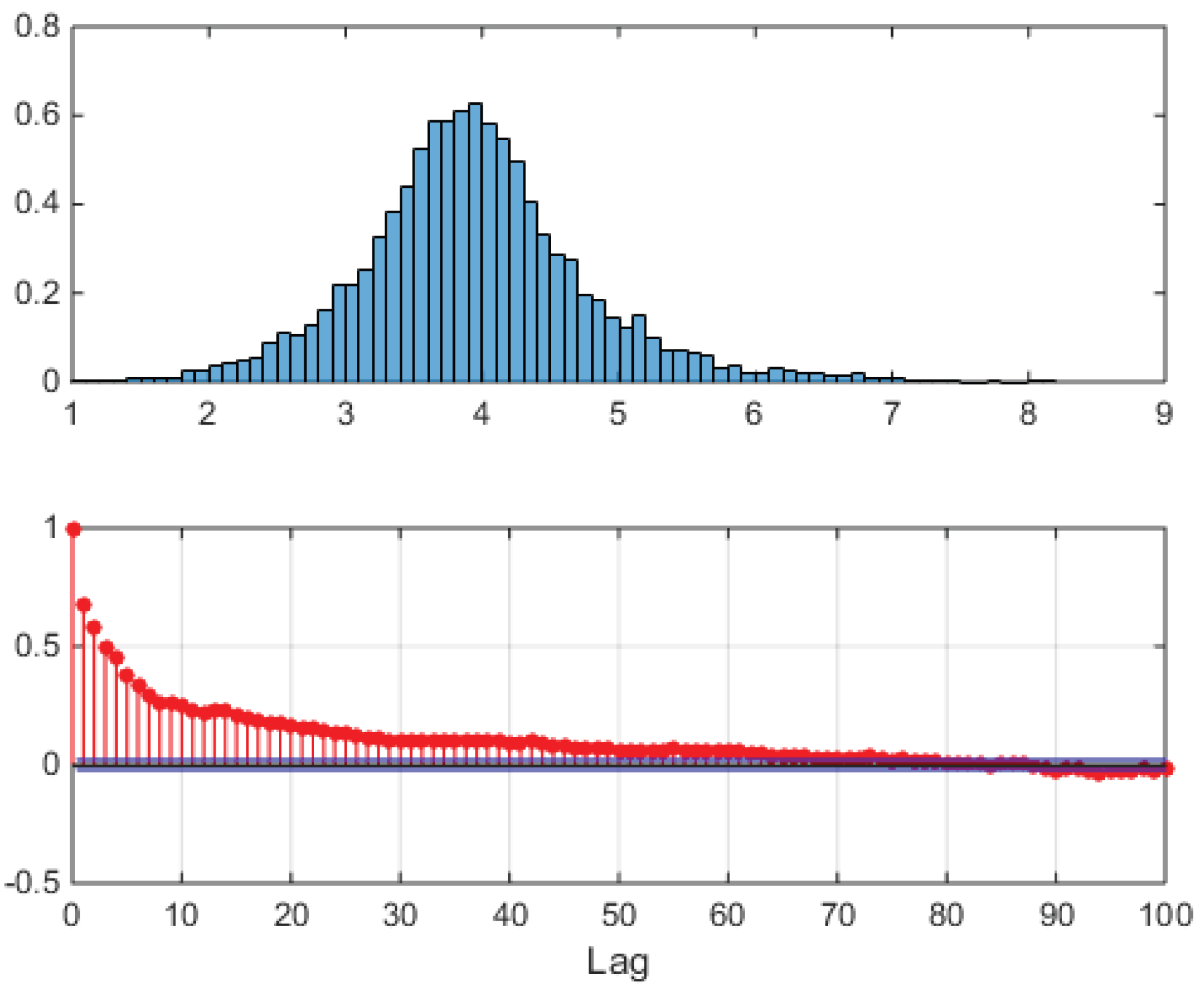

Figure 4.

Alberta power market data: one year from Apr-07-2006 to Apr-06-2007. Upper panel: empirical unconditional distribution of logprices, bar areas sum to 1. Lower panel: autocorrelation of preprocessed timeseries. For each day, at each hour the full data set average of that hour’s logprice was subtracted as .

Figure 4.

Alberta power market data: one year from Apr-07-2006 to Apr-06-2007. Upper panel: empirical unconditional distribution of logprices, bar areas sum to 1. Lower panel: autocorrelation of preprocessed timeseries. For each day, at each hour the full data set average of that hour’s logprice was subtracted as .

Figure 5.

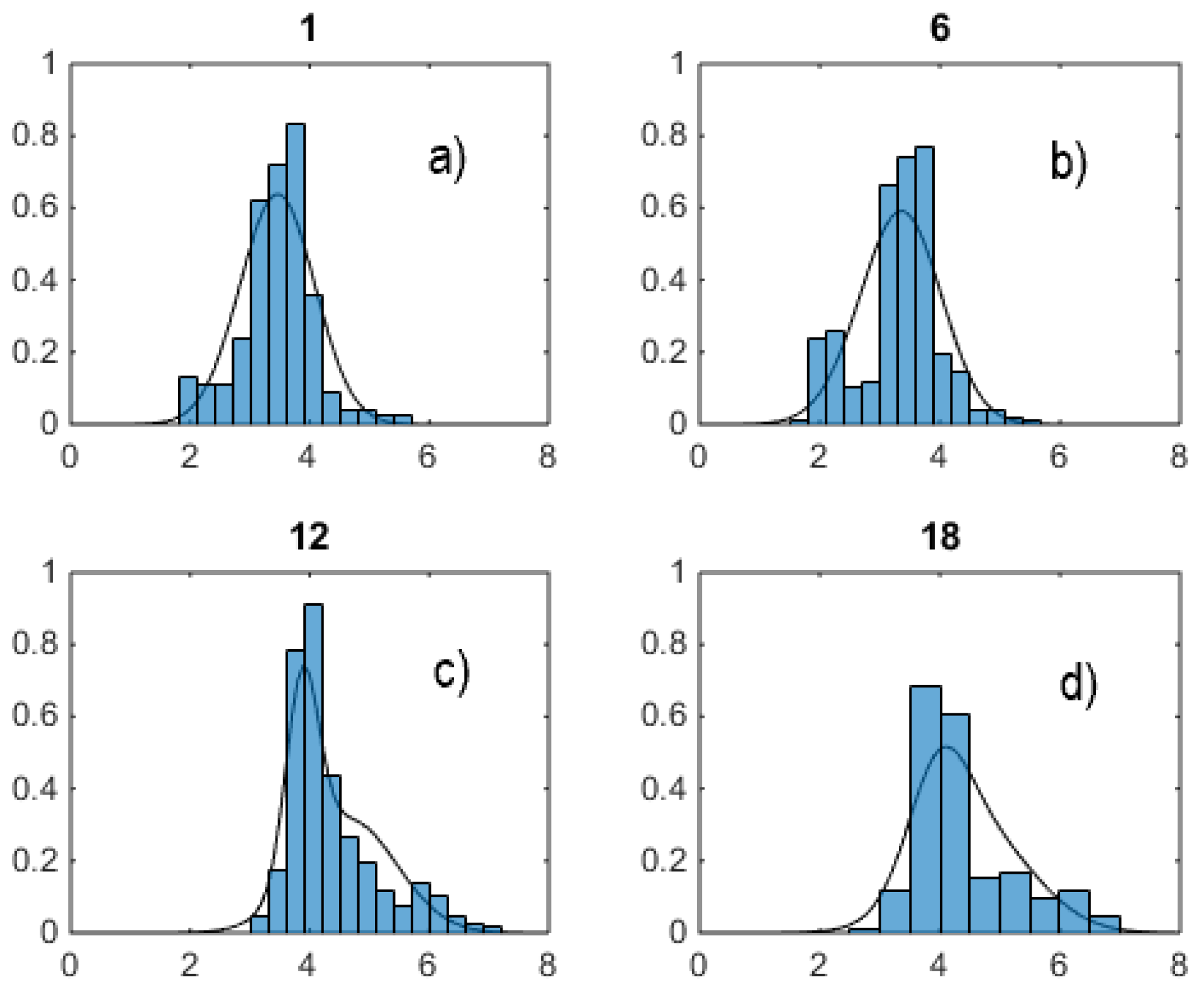

Four choices of logprice hourly sample distributions (histograms, bar areas sum to 1), and estimated marginals (continuous lines) of a two-component VM. a) hour 1, b) hour 6, c) hour 12, d) hour 18. Notice strong multimodality and skewness in panels b), c) and d).

Figure 5.

Four choices of logprice hourly sample distributions (histograms, bar areas sum to 1), and estimated marginals (continuous lines) of a two-component VM. a) hour 1, b) hour 6, c) hour 12, d) hour 18. Notice strong multimodality and skewness in panels b), c) and d).

Figure 6.

Hour/hour scatterplots, . 2-dimensional projections of clusters of logprices, hard-clustered with k-means in two clusters, a different model for each panel. Light red (south-west) and dark blue (north-east) distinguish the two populations found. Superimposed black crosses represent cluster centroids. First hour fixed at hour 1, second hour fixed at a) 2, b) 7, c) 13, d) 19. Clusters are not so well separated as with local k-means, but here the algorithm behaves in the same way for all cases.

Figure 6.

Hour/hour scatterplots, . 2-dimensional projections of clusters of logprices, hard-clustered with k-means in two clusters, a different model for each panel. Light red (south-west) and dark blue (north-east) distinguish the two populations found. Superimposed black crosses represent cluster centroids. First hour fixed at hour 1, second hour fixed at a) 2, b) 7, c) 13, d) 19. Clusters are not so well separated as with local k-means, but here the algorithm behaves in the same way for all cases.

Figure 7.

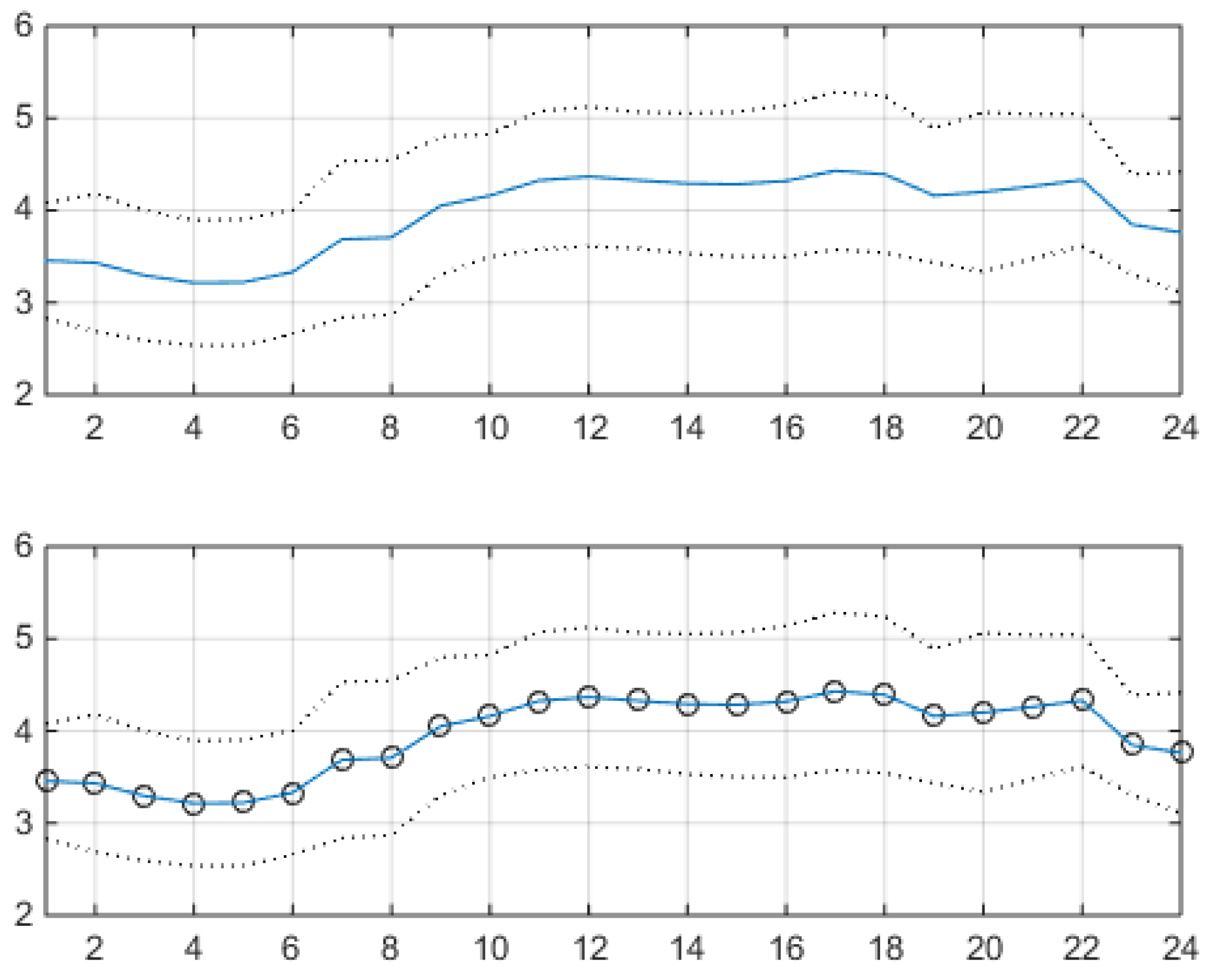

Two-component VM fit. Sample hourly means (upper panel) and estimated hourly means (lower panel) (solid lines) plus/minus corresponding one standard deviation curves (dotted lines). In the lower panel, is superimposed as a sequence of circles to , to help comparison - they practically coincide. Here BIC=. The number of reruns used to obtain this estimate is 300.

Figure 7.

Two-component VM fit. Sample hourly means (upper panel) and estimated hourly means (lower panel) (solid lines) plus/minus corresponding one standard deviation curves (dotted lines). In the lower panel, is superimposed as a sequence of circles to , to help comparison - they practically coincide. Here BIC=. The number of reruns used to obtain this estimate is 300.

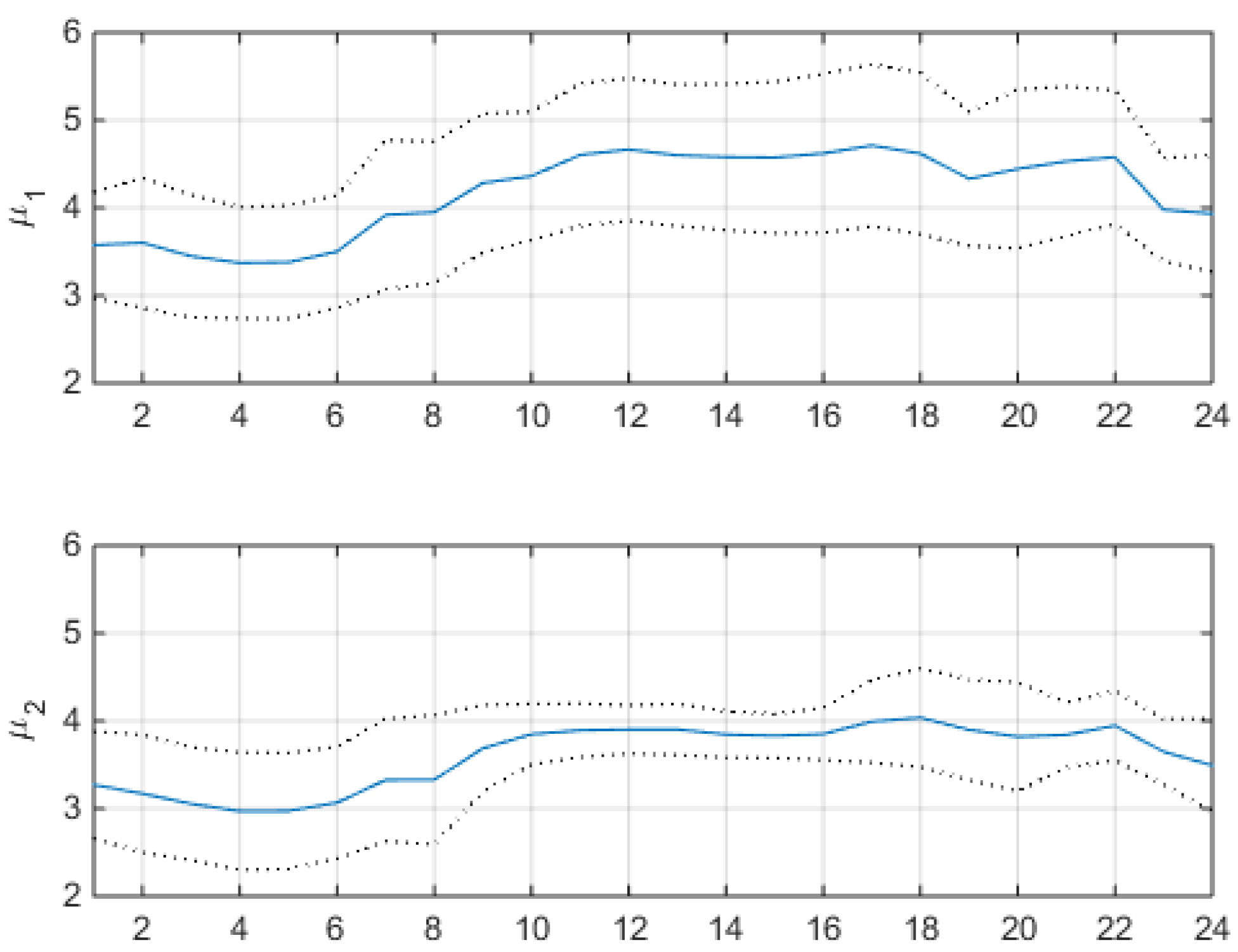

Figure 8.

Two-component VM fit. The upper panel shows the estimated hourly mean

of the first component (solid line) plus/minus one standard deviation of the component (dotted lines). The lower panel shows the estimated hourly mean

of the second component (solid line) plus/minus one standard deviation of the component (dotted lines). Their weights are

and

, their weighted sum is

in the lower panel of

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Two-component VM fit. The upper panel shows the estimated hourly mean

of the first component (solid line) plus/minus one standard deviation of the component (dotted lines). The lower panel shows the estimated hourly mean

of the second component (solid line) plus/minus one standard deviation of the component (dotted lines). Their weights are

and

, their weighted sum is

in the lower panel of

Figure 7.

Figure 9.

Two-component VM fit. Estimated hourly component covariances. Upper panel: first component . Lower panel: second component . h on the y- and x-axis. Covariance value scale on the r.h.s..

Figure 9.

Two-component VM fit. Estimated hourly component covariances. Upper panel: first component . Lower panel: second component . h on the y- and x-axis. Covariance value scale on the r.h.s..

Figure 10.

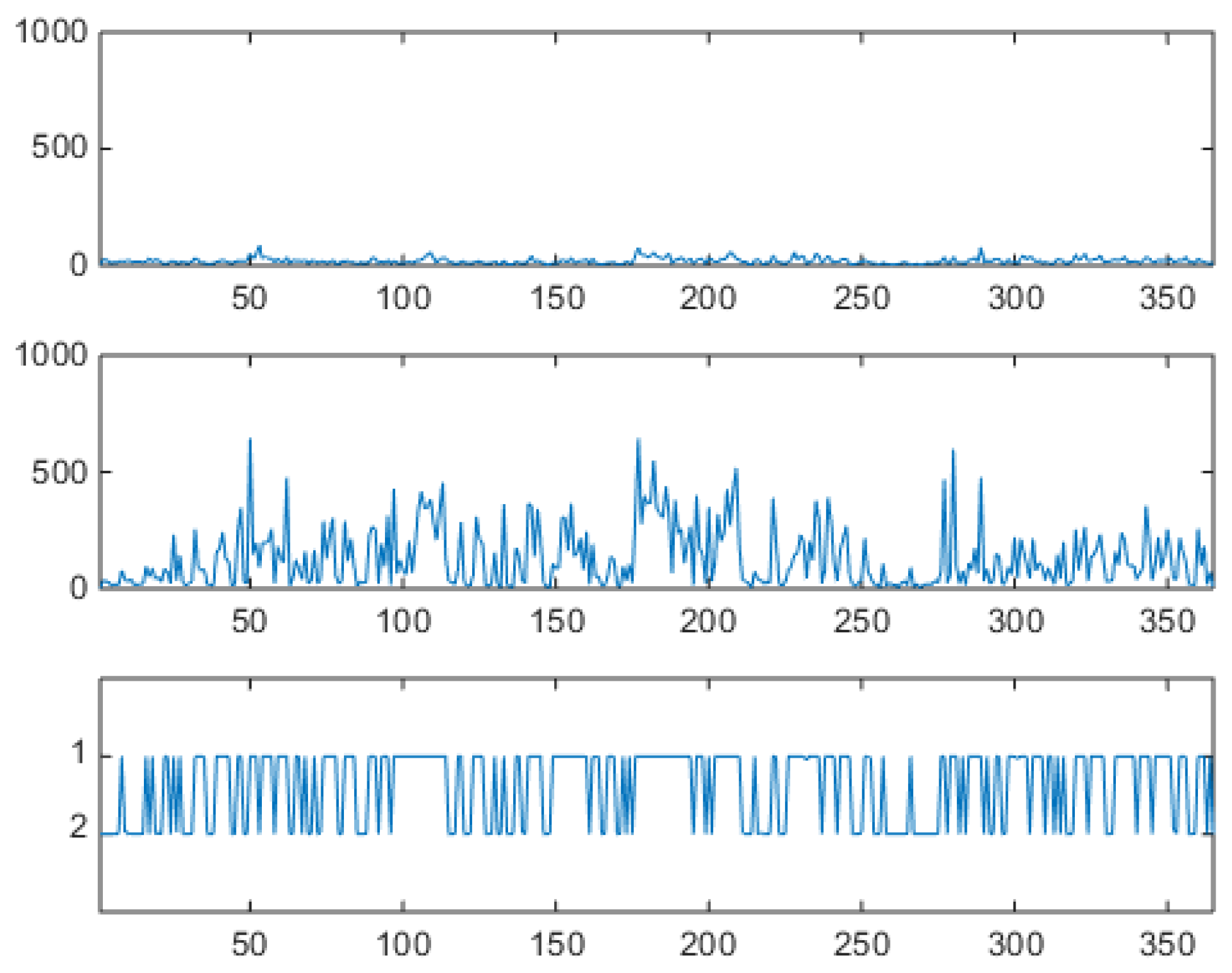

Two-component VM fit. Mahalanobis distances of individual market days from cluster 1 (upper panel) and cluster 2 (middle panel) centroids. In the lower panel the inferred membership at each day, or , to one of the two clusters. Time scale in days. Large distance from cluster 2 corresponds to large posterior probability of belonging to cluster 1. Market days can be classified ex post in terms of their (hidden) type.

Figure 10.

Two-component VM fit. Mahalanobis distances of individual market days from cluster 1 (upper panel) and cluster 2 (middle panel) centroids. In the lower panel the inferred membership at each day, or , to one of the two clusters. Time scale in days. Large distance from cluster 2 corresponds to large posterior probability of belonging to cluster 1. Market days can be classified ex post in terms of their (hidden) type.

Figure 11.

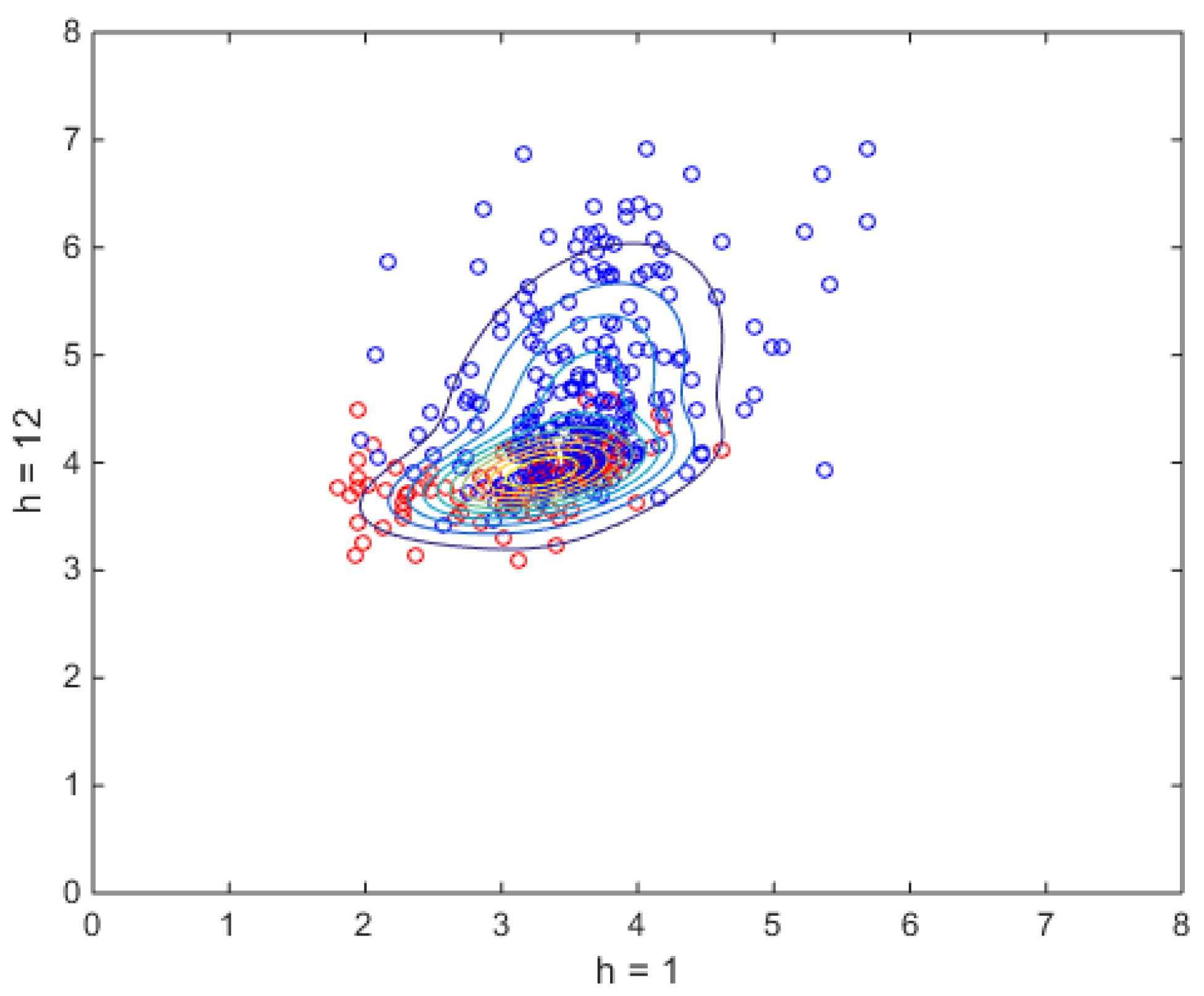

Fully probabilistic two-component VM fit of a choice of a two-hours marginal (bi-marginal), for the hours 1 and 12. Estimated bi-marginal probability density function, represented in terms of level curves, superimposed to the scatterplot of the market data - i.e., the distribution is seen from above. Data points (i.e., market days 2-d projections) of the scatterplot are marked as light red (south-west) or dark blue (north-east) according to membership inferred from soft clustering. The two peaks of the bimodal 2-d distribution are clearly visible. Compare this soft-clustered scatterplot with k-means hard clustered scatterplots, and their centroid positions. Notice that it is not possible to extract a distribution from k-means.

Figure 11.

Fully probabilistic two-component VM fit of a choice of a two-hours marginal (bi-marginal), for the hours 1 and 12. Estimated bi-marginal probability density function, represented in terms of level curves, superimposed to the scatterplot of the market data - i.e., the distribution is seen from above. Data points (i.e., market days 2-d projections) of the scatterplot are marked as light red (south-west) or dark blue (north-east) according to membership inferred from soft clustering. The two peaks of the bimodal 2-d distribution are clearly visible. Compare this soft-clustered scatterplot with k-means hard clustered scatterplots, and their centroid positions. Notice that it is not possible to extract a distribution from k-means.

Figure 12.

Synthetically generated series of 365 24-component logprice daily vectors, arranged in one hourly sequence 8760 hours long, sampled from a two-component VM estimated on Alberta data. Upper panel: prices. Lower panel: logprices. On the x axis, progressive hour number. To be compared with the market data series of

Figure 2.

Figure 12.

Synthetically generated series of 365 24-component logprice daily vectors, arranged in one hourly sequence 8760 hours long, sampled from a two-component VM estimated on Alberta data. Upper panel: prices. Lower panel: logprices. On the x axis, progressive hour number. To be compared with the market data series of

Figure 2.

Figure 13.

Blowup of the synthetically generated series of

Figure 12, two weeks. Prices (upper panel) and logprices (lower panel). On the x axis, progressive hour number. To be compared with the market data blowup in

Figure 3.

Figure 13.

Blowup of the synthetically generated series of

Figure 12, two weeks. Prices (upper panel) and logprices (lower panel). On the x axis, progressive hour number. To be compared with the market data blowup in

Figure 3.

Figure 14.

One year of synthetically generated series of logprices, two-component VM estimated on data. Upper panel: empirical unconditional distribution of logprices, bar areas sum to 1. Lower panel: preprocessed autocorrelation. To be compared with market data autocorrelation in

Figure 4. Notice the tail arriving at lag 24 (1 day).

Figure 14.

One year of synthetically generated series of logprices, two-component VM estimated on data. Upper panel: empirical unconditional distribution of logprices, bar areas sum to 1. Lower panel: preprocessed autocorrelation. To be compared with market data autocorrelation in

Figure 4. Notice the tail arriving at lag 24 (1 day).

Figure 15.

Types of S-state VHMMs, for , and intermediate layer weight matrices and . a) shallow mixture: one component per state, no intermediate layer; b) untied model, mixtures with components per state that can differ across states, i.e., 6 components in all, associated to for the intermediate layer; c) tied model, mixtures, components in all, associated to for the intermediate layer.

Figure 15.

Types of S-state VHMMs, for , and intermediate layer weight matrices and . a) shallow mixture: one component per state, no intermediate layer; b) untied model, mixtures with components per state that can differ across states, i.e., 6 components in all, associated to for the intermediate layer; c) tied model, mixtures, components in all, associated to for the intermediate layer.

Figure 16.

Two-component

tied VHMM fit. Estimated hourly component covariances. Upper panel: first component

. Lower panel: second component

.

h on the y- and x-axis. Compare with the two components of

Figure 9 obtained in the

shallow VM case.

Figure 16.

Two-component

tied VHMM fit. Estimated hourly component covariances. Upper panel: first component

. Lower panel: second component

.

h on the y- and x-axis. Compare with the two components of

Figure 9 obtained in the

shallow VM case.

Figure 17.

Two-component

tied VHMM estimated yearly on logprice data. Synthetically generated series for prices, logprices and hidden states. Upper panel: prices. Middle panel: logprices. Hours on x-axis for upper and middle panels. Lower panel: state trajectory

. Days on x-axis for the lower panel. State membership controls spikiness: for

spikiness is higher than for

. Compare with component covariances of

Figure 16.

Figure 17.

Two-component

tied VHMM estimated yearly on logprice data. Synthetically generated series for prices, logprices and hidden states. Upper panel: prices. Middle panel: logprices. Hours on x-axis for upper and middle panels. Lower panel: state trajectory

. Days on x-axis for the lower panel. State membership controls spikiness: for

spikiness is higher than for

. Compare with component covariances of

Figure 16.

Figure 18.

Two weeks of synthetically generated series of prices (upper panel) and logprices (lower panel), one full year estimate,

two-component tied VHMM estimated on logprice data. Hours on the x-axis for both panels. To be compared with market data series of

Figure 3.

Figure 18.

Two weeks of synthetically generated series of prices (upper panel) and logprices (lower panel), one full year estimate,

two-component tied VHMM estimated on logprice data. Hours on the x-axis for both panels. To be compared with market data series of

Figure 3.

Figure 19.

One year of synthetically generated series of logprices,

two-component tied VHMM estimated on one year of logprice data. Upper panel: empirical unconditional distribution of logprices, bar areas sum to 1, logprices on the x-axis. Lower panel: preprocessed autocorrelation. Notice the tail arriving at lag 48 (2 days). To be compared with the autocorrelation of original market data series of

Figure 4 and to the VM autocorrelation of

Figure 14, which arrives at lag 24.

Figure 19.

One year of synthetically generated series of logprices,

two-component tied VHMM estimated on one year of logprice data. Upper panel: empirical unconditional distribution of logprices, bar areas sum to 1, logprices on the x-axis. Lower panel: preprocessed autocorrelation. Notice the tail arriving at lag 48 (2 days). To be compared with the autocorrelation of original market data series of

Figure 4 and to the VM autocorrelation of

Figure 14, which arrives at lag 24.

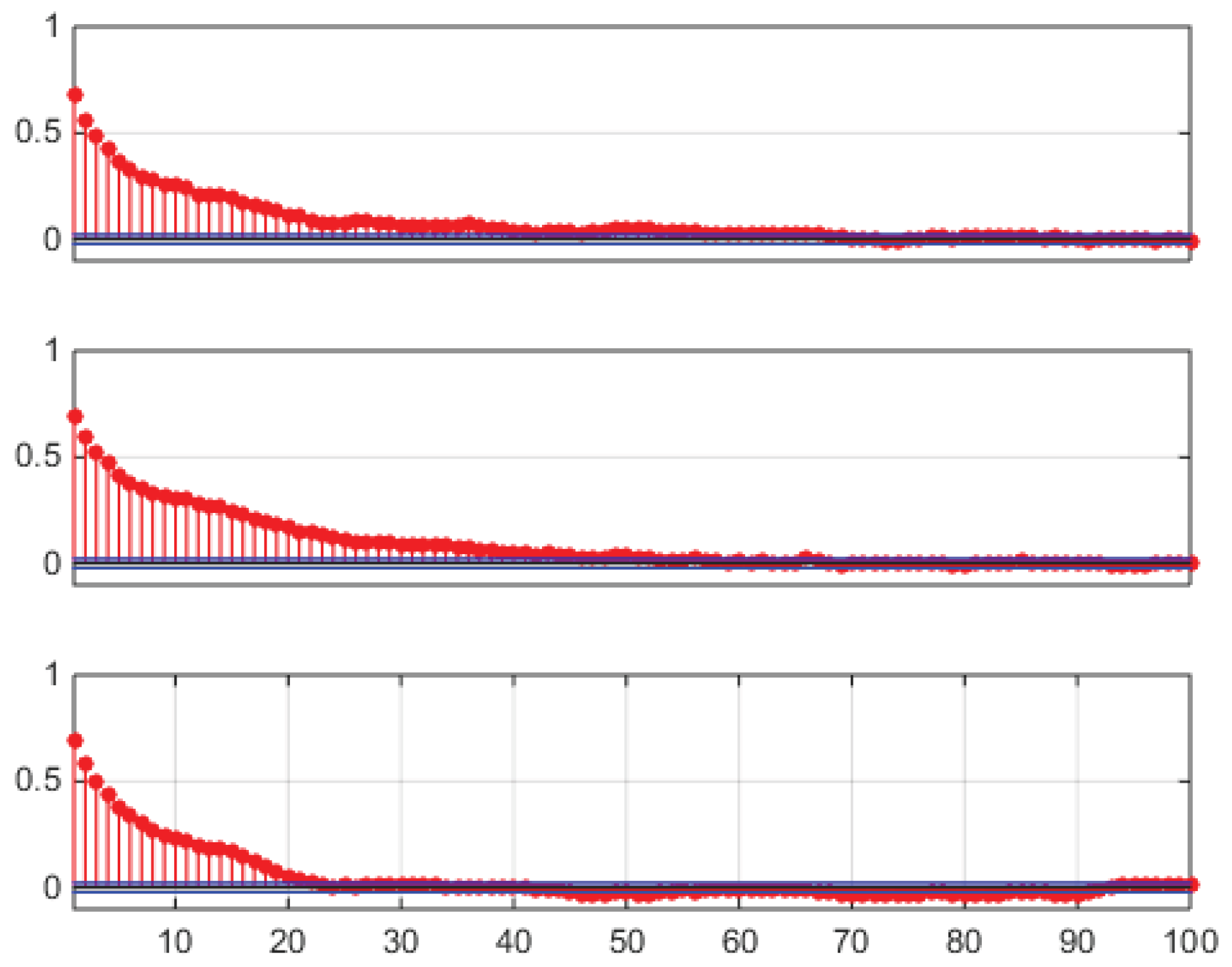

Figure 20.

Sample autocorrelation functions of three synthetically generated samples from a two-component tied VHMM estimated yearly on logprice data. Upper, middle and lower panels: sample autocorrelations. Lag scale on the x-axis extends to four days. These profiles are rather different. Notice the short autocorrelation in the lower panel.

Figure 20.

Sample autocorrelation functions of three synthetically generated samples from a two-component tied VHMM estimated yearly on logprice data. Upper, middle and lower panels: sample autocorrelations. Lag scale on the x-axis extends to four days. These profiles are rather different. Notice the short autocorrelation in the lower panel.