Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Inclusion Criteria:

- Patients with an indication for prenatal CMA due to prenatal maternal serum screening (MSS) tests risk with increased NT, advanced maternal age (AMA), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), increased nuchal translucency (NT), the detection of a structural anomaly or a soft marker in a prenatal ultrasound, a family history of chromosomal abnormalities, and risk determination in NIPT tests.

- Patients who signed an informed consent form agreeing to undergo prenatal genetic testing.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria:

- Patients with biochemical risks in prenatal screening but without increased nuchal translucency, prenatal USG abnormalities, or parental karyotype anomalies are required for a prenatal CMA indication.

- Patients who did not sign the informed consent form and declined prenatal genetic testing.

2.4. Parameters to be Examined:

- Presence of possible aneuploidy

- Presence of possible microdeletions/microduplications

- Mosaicism

- Uniparental disomy (UPD)

2.5. Karyotype Analysis:

2.6. CMA Analysis:

2.7. Statistical Analysis:

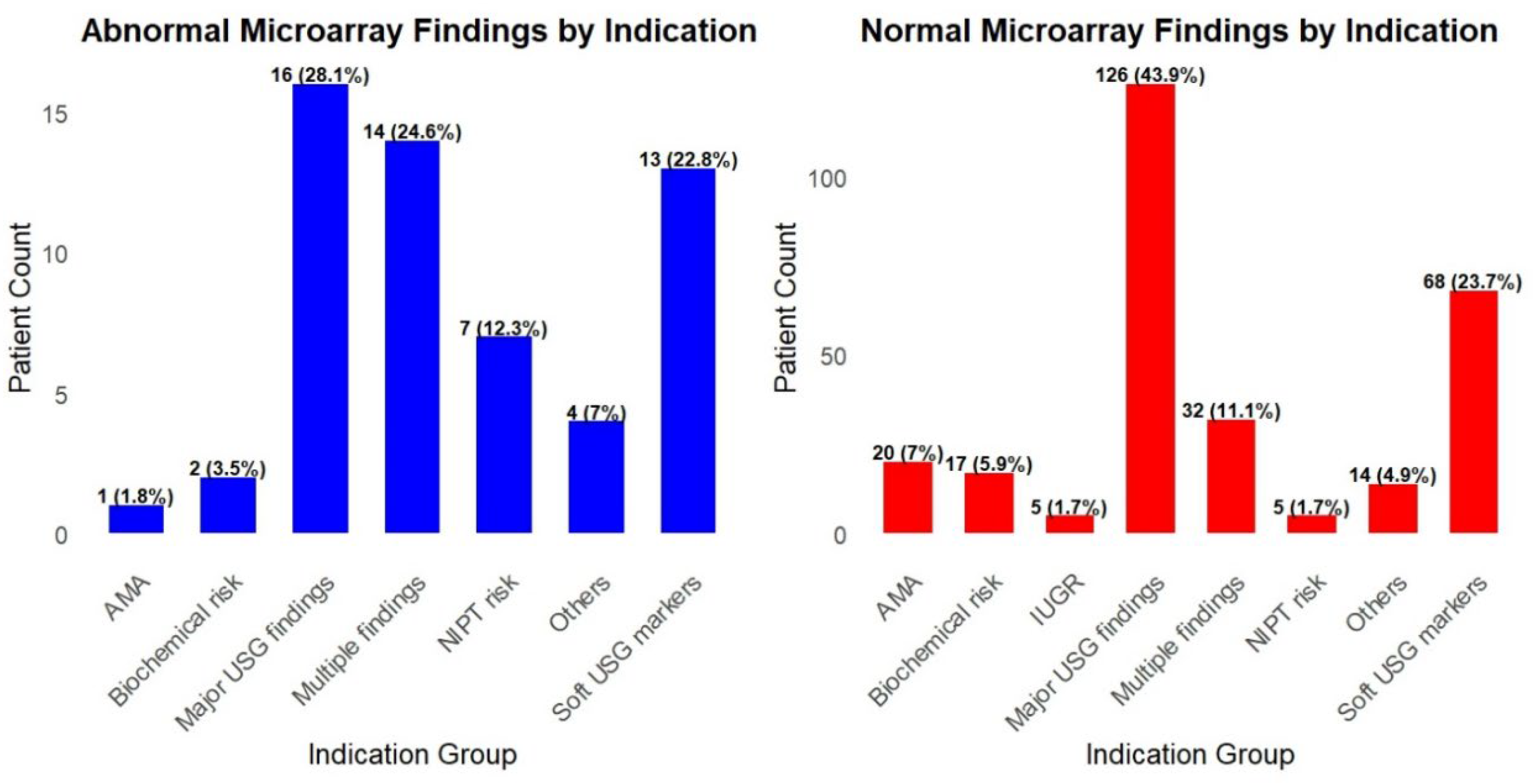

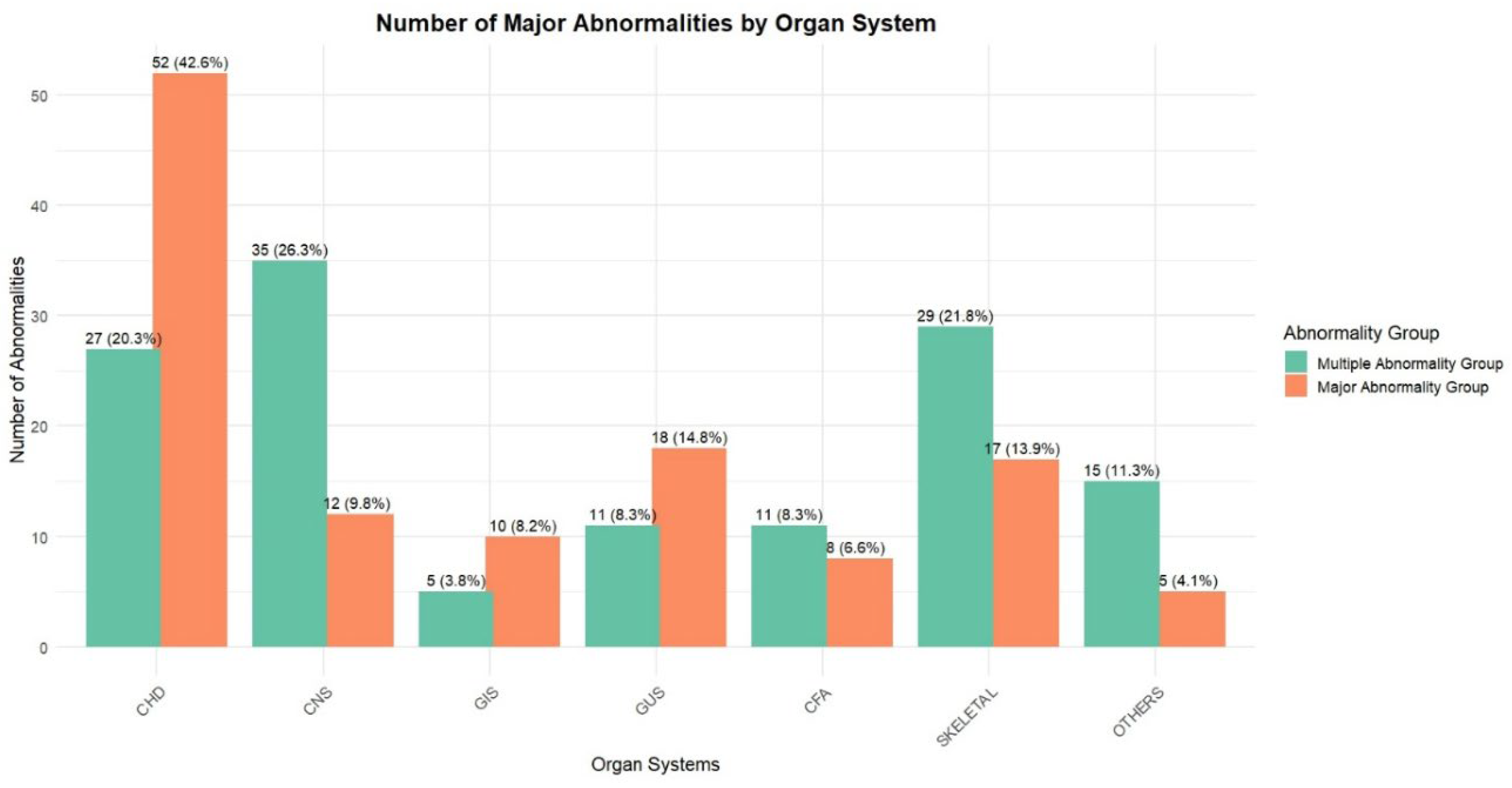

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOG | American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| AS | Amniocentesis |

| AVSD | Atrioventricular septal defect |

| CFM | Craniofacial morphology |

| CGH | Comparative genomic hybridization |

| CHD | Coronary heart disease |

| CMA | Chromosomal microarray analysis |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CNV | Copy number variants |

| CPC | Choroid plexus cysts |

| CSP | Cavum septi pellucidi |

| CVS | Cardiovascular system |

| CVS | Chorionic villus sampling |

| EICF | Echogenic intracardiac focus |

| GUS | Genitourinary System |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| LP | Likely pathogenic |

| MSS | Maternal serum screening |

| NIPT | Non-Invasive Prenatal Test |

| NT | Nuchal translucency |

| P | Pathogenic |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| TGA | Transposition of Great Arteries |

| UPD | Uniparental disomy |

| US | Ultrasound |

| VOUS | Variants of uncertain significance |

| WES | Whole-exome sequencing |

References

- Kearney HM, Thorland EC, Brown KK, Quintero-Rivera F, South ST. American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional copy number variants. Genet Med. 2011;13(7):680-685. [CrossRef]

- Levy B, Wapner R. Prenatal diagnosis by chromosomal microarray analysis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(2):201-212. [CrossRef]

- Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, Ballif BC, Eng CM, Zachary JM, et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2175-2184. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Chen M, Wang H, Guo Y, Chau MHK, Yan H, et al. Clinical utility of expanded non-invasive prenatal screening and chromosomal microarray analysis in high-risk pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(3):459-465. [CrossRef]

- South ST, Lee C, Lamb AN, Higgins AW, Kearney HM. ACMG Standards and Guidelines for constitutional cytogenomic microarray analysis, including postnatal and prenatal applications: revision 2013. Genet Med. 2013;15(11):901-909. [CrossRef]

- Vogel I, Petersen OB, Christensen R, Hyett J, Lou S, Vestergaard EM. Chromosomal microarray as primary diagnostic genomic tool for pregnancies at increased risk within a population-based combined first-trimester screening program. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(4):480-486. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Hu T, Wang J, Li Q, Wang H, Liu S. Prenatal Diagnostic Value of Chromosomal Microarray in Fetuses with Nuchal Translucency Greater than 2.5 mm. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:6504159. [CrossRef]

- Mademont-Soler I, Morales C, Soler A, Martínez-Crespo JM, Shen Y, Margarit E, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities in fetuses with abnormal cardiac ultrasound findings: evaluation of chromosomal microarray-based analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(4):375-382. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Li J, Ru T, Wang Y, Xu Y, Yang Y, et al. Identification of copy number variations associated with coronary heart disease by chromosomal microarray analysis and next-generation sequencing. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36(4):321-327. [CrossRef]

- Huang R, Fu F, Zhou H, Zhang L, Lei T, Cheng K, et al. Prenatal diagnosis in the fetal hyperechogenic kidneys: assessment using chromosomal microarray analysis and exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2023;142(6):835-847. [CrossRef]

- Xie X, Wu X, Su L, Cai M, Li Y, Huang H, Xu L. Application of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Microarray in Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetuses with Central Nervous System Abnormalities. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:4239-4246. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly JC, Platt LD, Rebarber A, Zachary J, Grobman WA, Wapner RJ. Association of copy number variants with specific ultrasonographically detected fetal anomalies. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):83-90. [CrossRef]

- On Genetics GC. Committee opinion no. 581: the use of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122(6):1374-1377.

- Callaway JL, Shaffer LG, Chitty LS, Rosenfeld JA, Crolla JA. The clinical utility of microarray technologies applied to prenatal cytogenetics in the presence of a normal conventional karyotype: a review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(12):1119-1123. [CrossRef]

- Bütün Z, Kayapınar M, Şenol G, Akca E, Gökalp EE, Artan S. Comparison of conventional karyotype analysis and CMA results with ultrasound findings in pregnancies with normal QF-PCR results. 2025.

- Benn P, Cuckle H, Pergament E. Non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy: current status and future prospects. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;42(1):15-33.

| Sample | Results (Hg19) | Week | USG | Maternal Age | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | 16p13.11(14975292_16295863)x1 | 23+4 | Enlarged ventricle | 30 | USG findings |

| AS | 16p12.2p11.2(21575087_29319922)x1 | 26 | Enlarged ventricle | 35 | USG findings |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 21+2 | Hepatic calcification, echogenic cardiac focus | 28 | USG findings |

| AS | 15q11.2(22766739_23226254)x1 | 22 | Ambiguous genitals, hydronephrosis | 20 | Congenital anomaly |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 23+2 | Renal pyelectasis | 33 | Congenital anomaly |

| AS | Trisomy 13 | 24+3 | Ventriculomegaly, renal pyelectasis, hypospadias, coarctation of the aorta | 38 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Trisomy 18 | 30 | Anal atresia, polyhydramniosis, IUGR, single umblical artery | 24 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 18+3 | Renal pelviectasis, AVSDa | 36 | Multiple findings |

| AS | 8p23.3p23.1(170692_12009597)x3, 9p24.3p11.2(10201_44888946)x3, 9q13q22.33(68158106_101087286)x3 | 16+6 | Cleft palate, CHD | 35 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Klinefelter Syndrome | 22 | Pulmonary stenosis, cleft lip and palate, renal pelviectasis, thymus hypoplasia | 26 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Trisomy 18 | 28 | Clenched hand, VSD | 26 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Trisomy 18 | 22 | IUGR, clench hand, mandibular hypoplasia, VSD, horseshoe kidney | 35 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 17 | Duodenal atresia, NT:6mm | 39 | Multiple findings |

| AS | Trisomy 13 | 23 | Inferior Vermis Hypoplasia, Polyhydramnios, Mesochardia, TGAb | 37 | Multiple findings |

| Chord sample |

Trisomy 13 | 24 | Cleft Lip/Palate, Hyperecogenic Bowel, Hypoplastic Left Heart, Aortic Coarctation, Holoprosencephaly | 24 | Multiple findings |

| AS | 22q11.21(18877787_21461607)x1, Di George | 28 | Truncus Arteriosus, hypoplastic tymus, VSD | 35 | CHD |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 21+4 | Hypoplastic nasal bone, AVSDa | 33 | CHD |

| AS | 14q32.2q32.33(99718925_107289511)x1 | 32 | Craniosynostosis, hypoplastic left heart, aortic hypoplasia, doubled collecting system of the left kidney | 25 | CHD |

| AS | Klinefelter Syndrome | 16+3 | D-TGAb | 38 | CHD |

| AS | Turner Syndrome | 25 | Aort hypoplasia | 21 | CHD |

| AS | 4p16.3p11(84414_49620838)x3, 13q11q12.11(19020095_21578150)x1 | 23+2 | Pulmonary hypoplasia, VSD, Fallot tetralogy, overriding aorta, clenched hand | 23 | CHD |

| CVS | Turner Syndrome | 14+1 | Hypoplastic left heart | 23 | CHD |

| AS | Trisomy 13 | 21+5 | AVSDa | 23 | CHD |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 17+2 | VSD, echogenic liver focus | 37 | CHD |

| AS | 11q23.3q25(119110984_134946504)x1, 11q23.3(118545797_119103406)x3 | 22+4 | Hypoplastic left heart | 31 | CHD |

| AS | Xq27.2q28(140856453_155234707)x1, 4q28.3q35.2(134134331_190484505)x3 | 23 | VSD, truncus arteriosus, left-sided gall bladder | 33 | CHD |

| AS | Trisomy 18 | 22 | IUGR, Perimembranous VSD | 35 | CHD |

| AS | 13q21.33q33.2(73157290_105760332)x1 | 30 | Vernian hypoplasia, Pes equinovarus | 25 | CNS anomaly |

| AS | 16p11.2(29323692_30364805)x3 | 22+5 | Hydrocephaly, lemon sign, cerebellar hypoplasia, left multicyclic dysplastic kidney, Sacral meningomyelocele. | 37 | CNS anomaly |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 16+5 | Alobar holoprosencephaly | 37 | CNS anomaly |

| CVS | Trisomy 18 | 12 | NT:7mm | 43 | Increased NT |

| CVS | Trisomy 21 | 12+5 | NT:5, Cystic hygroma | 32 | Increased NT |

| AS | 10p11.1(38784659_39150257)x1 , 10q11.22q11.23(49262918_51832748)x1 | 16 | NT 2.6 | 36 | Increased NT |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 13+4 | NT 5, diffuse edema, echogenic cardiac focus | 38 | Increased NT |

| C.V.S | 4q31.3q35.2(155190509_191044208)x3 | 13 | NT:4mm | 39 | Increased NT |

| AS | Trisomy 13 | 18 | Polydactyly of the right foot, hyperecogenic heart | 37 | Skeletal anomaly |

| AS | Xp22.31(6453470_8126718)x0 | 15+4 | N | 23 | Biochemical risk |

| AS | 4q22.2q22.3(94006191_97808388)x1 | 17 | N | 34 | Biochemical risk |

| AS | 15q11.2(22766739_23226254)x1 | 22 | N | 20 | Other |

| AS | 47,XYY | 20+4 | CSPc | 38 | Other |

| C.V.S | 6q14.3q22.31(85761559_120871846)x1 | NA | NA | 25 | Other |

| AS | Mosaic UPD of chromosome 3 | 20 | CSPc | 41 | Other |

| AS | Trisomy 18 | 17 | Megacystit, clenched hand, hydrops, club foot, VSD | 40 | Hydrops |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 28 | Hydrops, polyhydramniosis | 34 | Hydrops |

| AS | Yp11.31p11.2(2657176_10057648)x2,Yq11.1q11.221(13133499_19567718)x2,Yq11.222q11.223(20804835_24522333)x0 | 20 | N | 24 | NIPT risk |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 19+2 | Fallot tetralogy | 35 | NIPT risk |

| C.V.S | Trisomy 21 | 13+5 | NIPT Tr.21 risk | 24 | NIPT risk |

| AS | 16q11.2q23.1(46501717_75493481)x3 | 14 | N | 24 | NIPT risk |

| AS | Trisomy 21 | 17 | NT:3.4MM | 17 | NIPT risk |

| Results (Hg19) | Size | Detected by Karyotyping | Week | USG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16p13.11(14975292_16295863)x1 | 1.32 Mb | No | 23+4 | Enlarged ventricle |

| 16p12.2p11.2(21575087_29319922)x1 | 7.74 Mb | Yes | 26 | Enlarged ventricle |

| 15q11.2(22766739_23226254)x1* | 460 Kb | No | 22 | Ambiguous genitals, hydronephrosis |

| 8p23.3p23.1(170692_12009597) x3 9p24.3p11.2(10201_44888946) x3 9q13q22.33(68158106_101087286) x3 |

11.8MB 44.8Mb 33Mb |

Yes | 16+6 | Cleft palate, CHD |

| 22q11.21(18877787_21461607)x1 | 2.583 kb | No | 28 | Truncus Arteriosus, hypoplastic tymus, VSD |

| 14q32.2q32.33(99718925_107289511)x1 | 7.5 Mb | Yes | 32 | Craniosynostosis, hypoplastic left heart, aortic hypoplasia, doubled collecting system of the left kidney |

| 4p16.3p11(84414_49620838) x3, 13q11q12.11(19020095_21578150)x1 |

49.5 Mb 2.6Mb |

Yes No |

23+2 | Pulmonary hypoplasia, VSD, Fallot tetralogy, overriding aorta, clenched hand |

| 11q23.3q25(119110984_134946504) x1 11q23.3(118545797_119103406)x3 |

15.8Mb 558Kb |

Yes No |

22+4 | Hypoplastic left heart |

| Xq27.2q28(140856453_155234707)x1 4q28.3q35.2(134134331_190484505)x 3 |

14.2Mb 56.3 Mb |

Yes | 23 | VSD, truncus arteriosus, left-sided gall bladder |

| 13q21.33q33.2(73157290_105760332)x1 | 33 Mb | Yes | 30 | Vermian hypoplasia, Pes equinovarus |

| 16p11.2(29323692_30364805)x3 | 1.04Mb | No | 22+5 | Hydrocephaly, lemon sign, cerebellar hypoplasia, left multicyclic dysplastic kidney, Sacral meningomyelocele. |

| 10p11.1(38784659_39150257) x1, 10q11.22q11.23(49262918_51832748)x1 |

366Kb 2.6 Mb |

No | 16 | NT 2.6 |

| 4q31.3q35.2(155190509_191044208)x3 | 36Mb | Yes | 13 | NT:4mm |

| Xp22.31(6453470_8126718)x0 | 1.7Mb | No | 15+4 | N |

| 4q22.2q22.3(94006191_97808388)x1 | 3.8Mb | No | 17 | N |

| 15q11.2(22766739_23226254)x1* | 460 Kb | No | 22 | N |

| 6q14.3q22.31(85761559_120871846)x1 | 35.1 Mb | Yes | NA | NA |

| Mosaic UPD of whole chromosome 3 | No | 20 | CSP | |

| Yp11.31p11.2(2657176_10057648)x2, Yq11.1q11.221(13133499_19567718)x2, Yq11.222q11.223(20804835_24522333)x0 |

7.4Mb 6.4 Mb 3.7Mb |

Yes | 20 | N |

| 16q11.2q23.1(46501717_75493481)x3 | 29Mb | Yes | 14 | N |

| Indications | N | Abnormal | P/LP CNV | Aneuploidi | Abnormal Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USG findings | 41 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.073 |

| Congenital anomaly | 39 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.053 |

| Multiple indications | 38 | 10 | 1 | 9 | 0.26 |

| CHD | 35 | 13 | 5 | 8 | 0.37 |

| CNS anomaly | 34 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.088 |

| Increased NT | 33 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Skeletal anomaly | 26 | 1 | - | 1 | 0.038 |

| Biochemical risk1 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.105 |

| Other (Family history) | 18 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Hydrops | 15 | 2 | - | 2 | 0.14 |

| NIPT risk | 12 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0.58 |

| AMA | 21 | 1 | - | 1 | 0.047 |

| Cystic hygroma | 6 | 5 | - | 5 | 0.83 |

| IUGR | 5 | - | - | - | 0 |

| Anhydramnios/oligohydramnios | 3 | - | - | - | 0 |

| Total | 344 | 57 | 18 | 39 | 0.165 |

| CVS* | CNS* | GUS* | GIS* | CFM* | Skeletal | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Ilial atresia | Pelviectasis | |||||

| P2 | Cleft palate | Nasal bone: 6MM | |||||

| P3 | Coarctation of the aorta | Eophageal atresia, | Hypoplastic radius and ulna, left hemihypoplasia | ||||

| P4 | Ventriculomegaly, | Pelviectasis | |||||

| P5 | Ventriculomegaly, ARSA | ||||||

| P6 | Ventriculomegaly, Coarctation of the aorta |

Renal pyelectasis, hypospadias |

|||||

| P7 | VSD | NT:5.5 | |||||

| P8 | Hemivertebra | NT:5.5 | |||||

| P9 | Echogenic intracardiac focus, VSD | NT:6 mm | |||||

| P10 | Single umbilical artery | Anal atresia | Polyhydramniosis | IUGR | |||

| P11 | AVSD | Renal pelviectasis | |||||

| P12 | Hypoplastic left heart | Hydrops | |||||

| P13 | Occipital cephalocele, Corpus callosum dysgenesis, spina bifida | Hypoplastic thorax | NT:9 mm, IUGR | ||||

| P14 | CHD | Cleft palate | |||||

| P15 | Club foot, clenched hand | Hydrops fetalis | |||||

| P16 | Pulmonary stenosis | Renal pelviectasis | cleft lip and palate | Thymus hypoplasia | |||

| P17 | Muscular vsd | Renal pelviectasis, | |||||

| P18 | Hypoplastic left heart, | Tubular hypoplasia | |||||

| P19 | Aortic arch anomaly, | Tethered cord, CSP | |||||

| P20 | pulmonary artery hypoplasia | Omphalocele | Polyhydramnios | Clenched hands | |||

| P21 | Coarctation of the aorta, Ebstein anomaly | Hydrops fetalis | |||||

| P22 | VSD | Clenched hand | |||||

| P23 | Omphalocele | Hydrops fetalis | |||||

| P24 | VSD | Horseshoe kidney | mandibular hypoplasia | Clenched hand | IUGR | ||

| P25 | Renal pelviectasis, polyhydramniosis |

||||||

| P26 | Echogenic cardiac focus, VSD | Oligohydroamniosis | |||||

| P27 | VSD | Clenched hand, rocker bottom feet | |||||

| P28 | Ventriculomegaly, | Hydrocephalus | Clench Hand, Pes Echinovarus, | Cystic Hygroma, Pleural Effusion | |||

| P29 | Tetralogy Of Fallot | Encephalocele | Hypertelorism | ||||

| P30 | Echogenic cardiac focus | NT: 6.2 mm | |||||

| P31 | Tricuspid Atresia, Right Ventricular Hypoplasia, | Polyhydroamniosis | Diaphragmatic Hernia | ||||

| P32 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, AMA | Edema,Hydrops fetalis, | |||||

| P33 | Unilateral cardiac ventriculomegaly, VSD | Polyhydroamniosis | |||||

| P34 | Bilateral pes equinovarus, narrow thorax | NT:7.71mm | |||||

| P35 | Ectopia Cordis | Omphalocele | Cystic Hygroma, NT:6.3mm | ||||

| P36 | Encephalocele | NT:6mm | |||||

| P37 | Choroid plexus cyst | Echogenic bowel | , NT:4mm | ||||

| P38 | Ventriculomegaly | cleft lip | |||||

| P39 | Bilateral pes equinovarus, narrow thorax | NT:7.71mm | |||||

| P40 | Duodenal atresia | NT:6mm | |||||

| P41 | Mesocardia, TGA | Inferior Vermis Hypoplasia | Polyhydramnios | ||||

| P42 | Hypoplastic Left Heart, Aortic Coarctation, | Holoprosophechaly | Hyperecogenic Bowel | Cleft Lip/Palate | |||

| P43 | Truncus Arteriosus, VSD | Hypoplastic tymus | |||||

| P44 | Pulmonary stenosis, Fallot tetralogy, right aortic arch, | Hypoplasia of the thymus | |||||

| P45 | Hypoplastic left heart, aortic hypoplasia, | Double collecting system of the left kidney | Craniosynostosis | ||||

| P46 | Pulmonary hypoplasia, VSD, Fallot tetralogy, overriding aorta | Clenched hand | |||||

| P47 | VSD, truncus arteriosus | Left-sided gall bladder |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).