Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

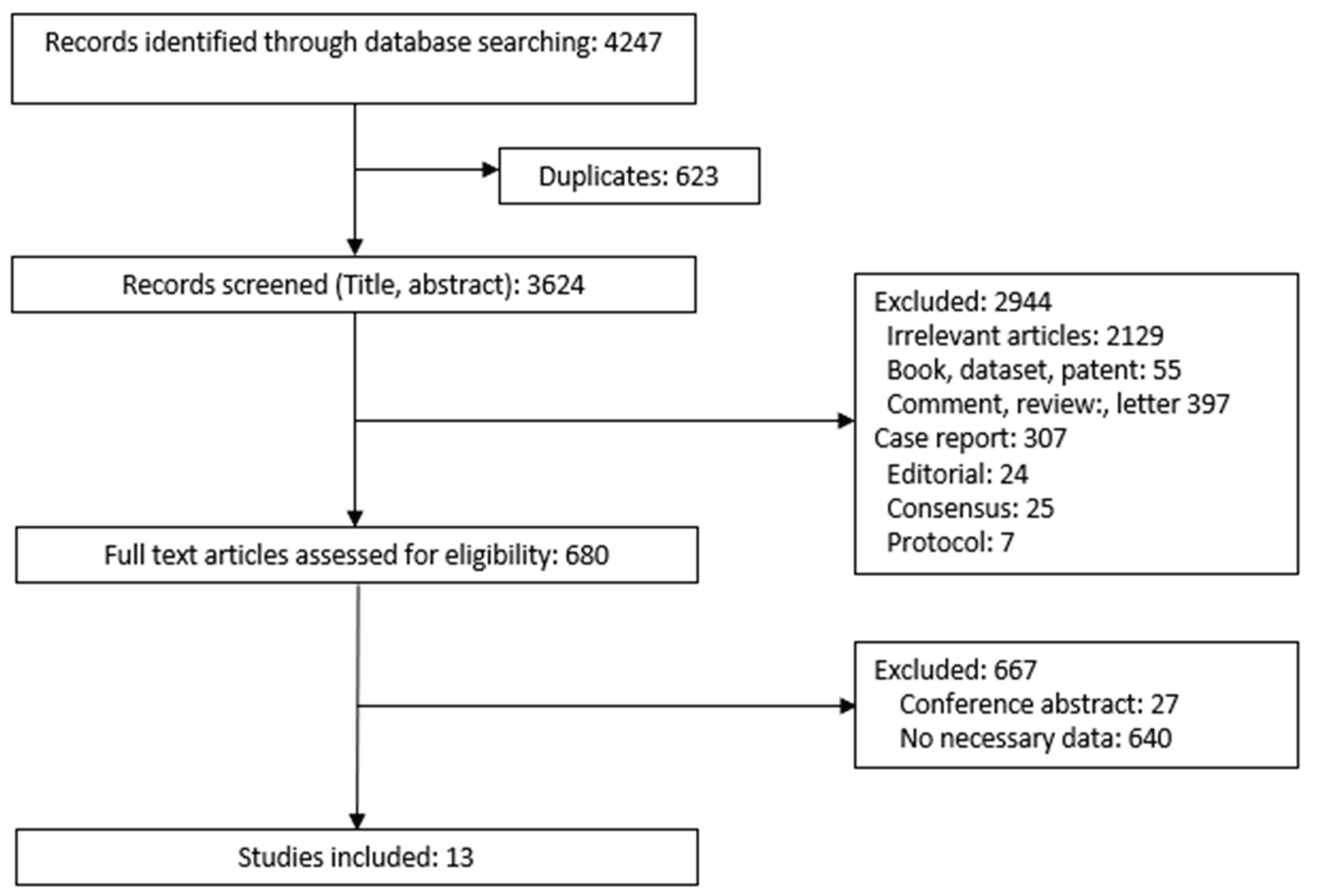

2.1. PRISMA Compliance in Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.2. Data Collection and Management

2.3.3. Data Extraction

2.3.4. Study Quality Evaluation

2.3.5. Measurement of Treatment Effect

2.3.6. Grading the Quality of Evidence

2.3.7. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics and Dissemination

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

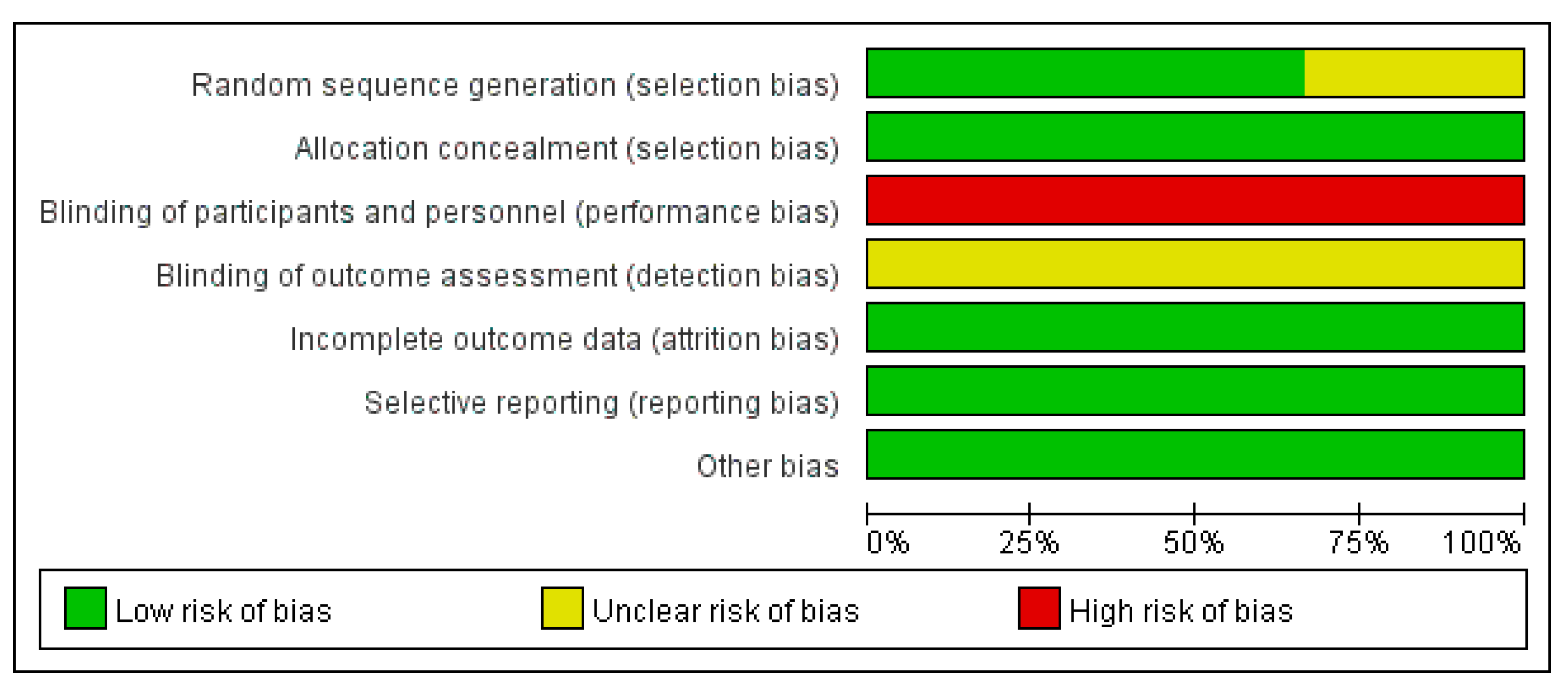

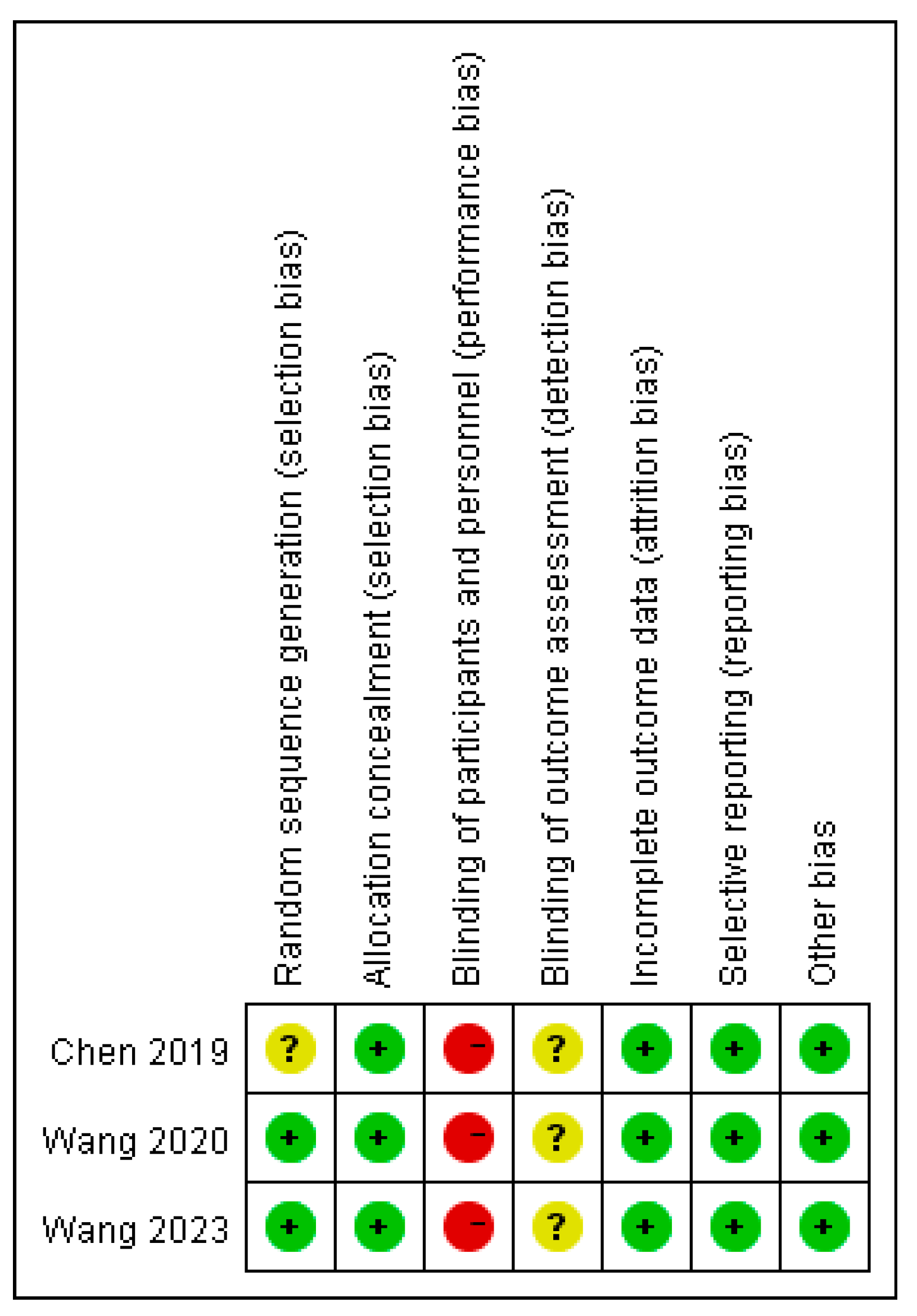

3.2. Quality Assessment

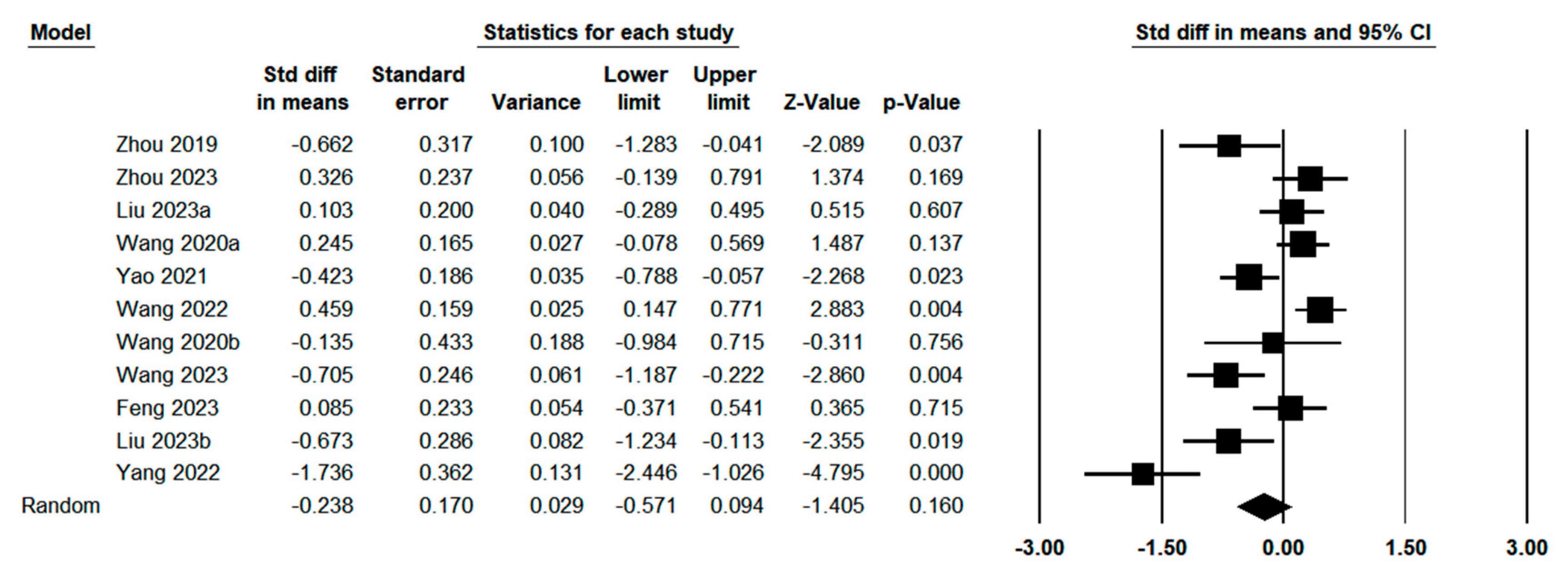

3.3. Quantitative Meta-Analysis

3.3.1. Publication Bias and Heterogeneity Test

3.3.2. Clinical Characteristics Between Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Laparoscopy Group and Conventional Laparoscopy Group

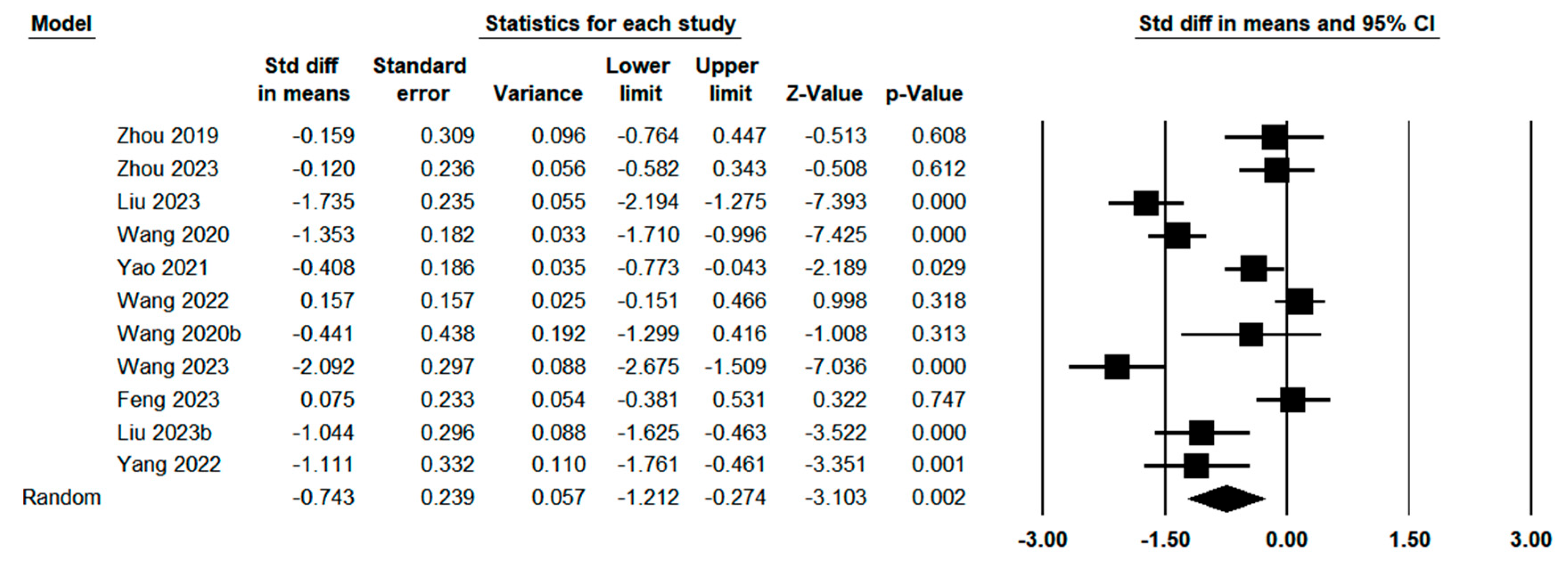

3.3.3. Operative Outcomes Between Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Laparoscopy Group and Conventional Laparoscopy Group

3.3.4. Postoperative Outcomes Between Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Laparoscopy Group and Conventional Laparoscopy Group

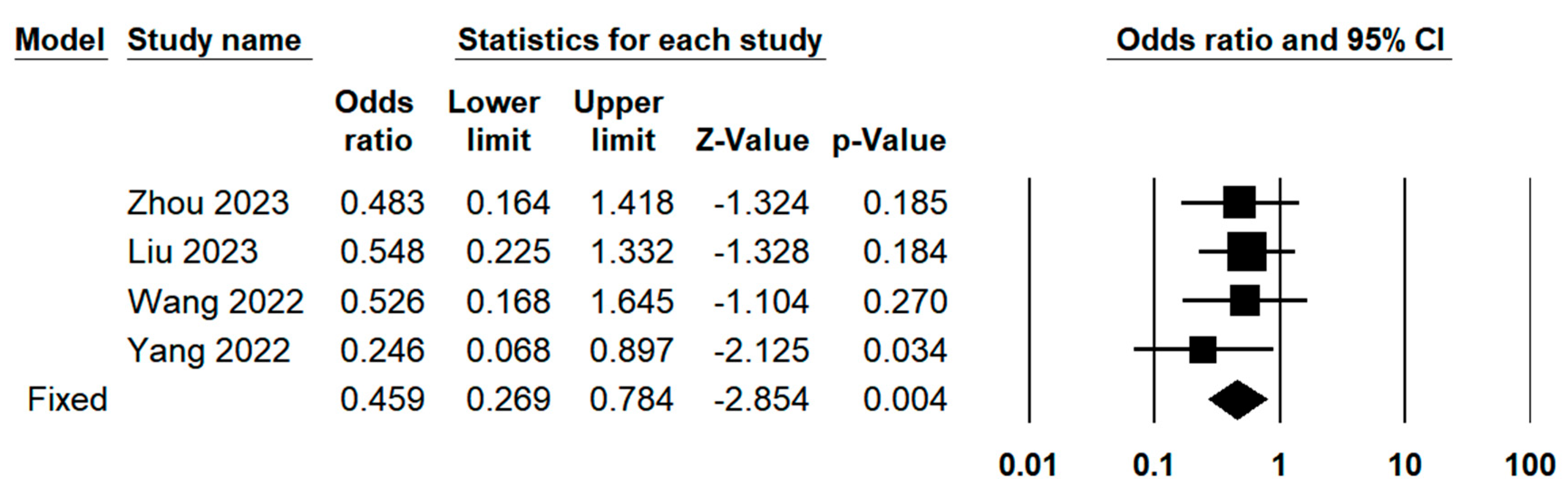

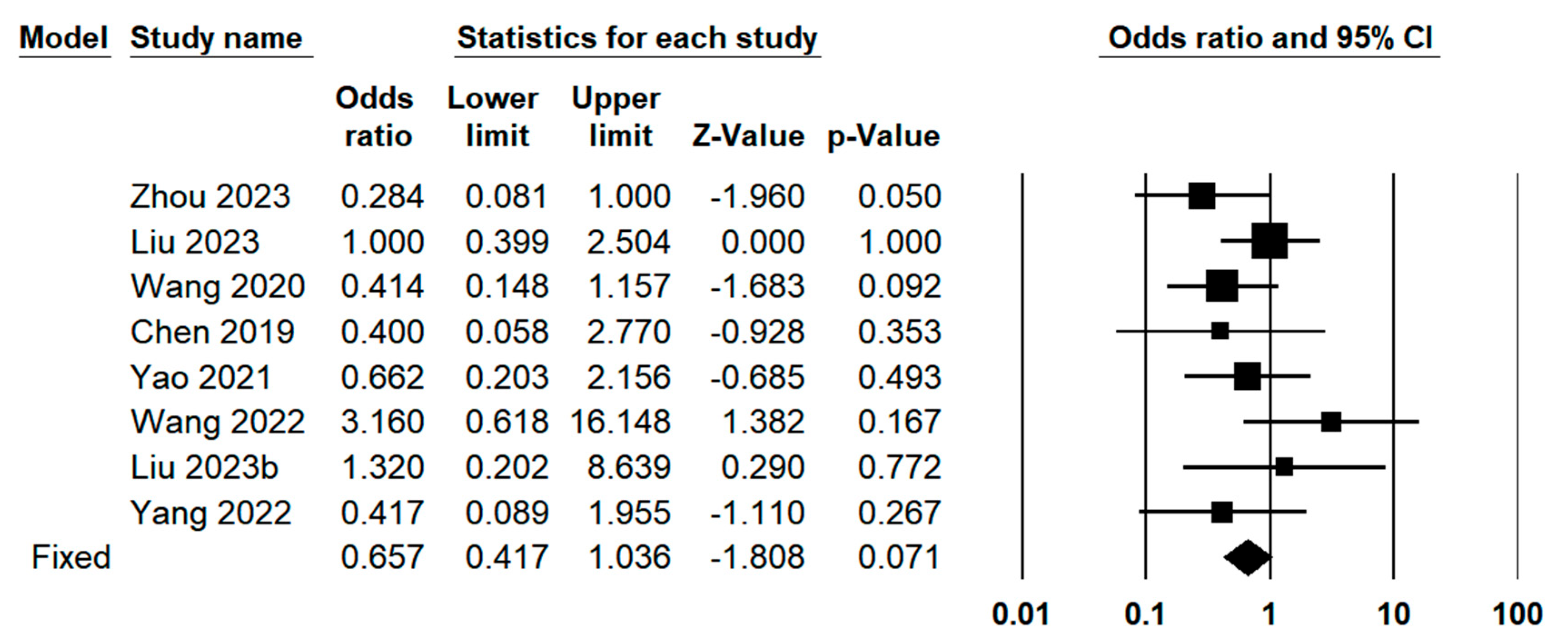

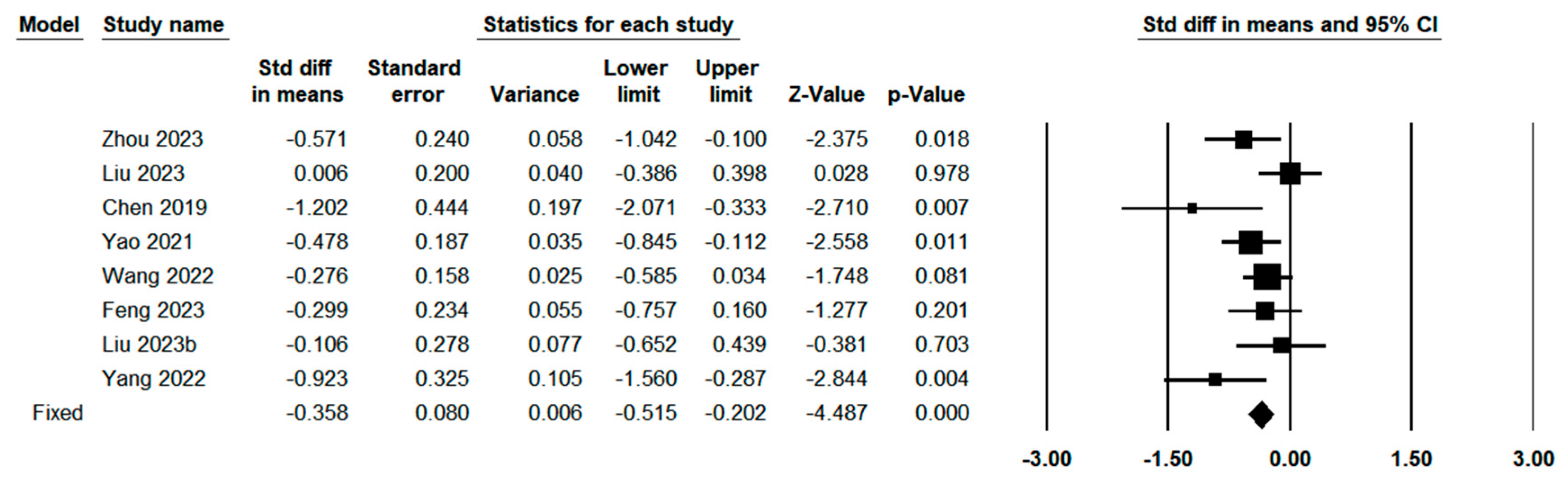

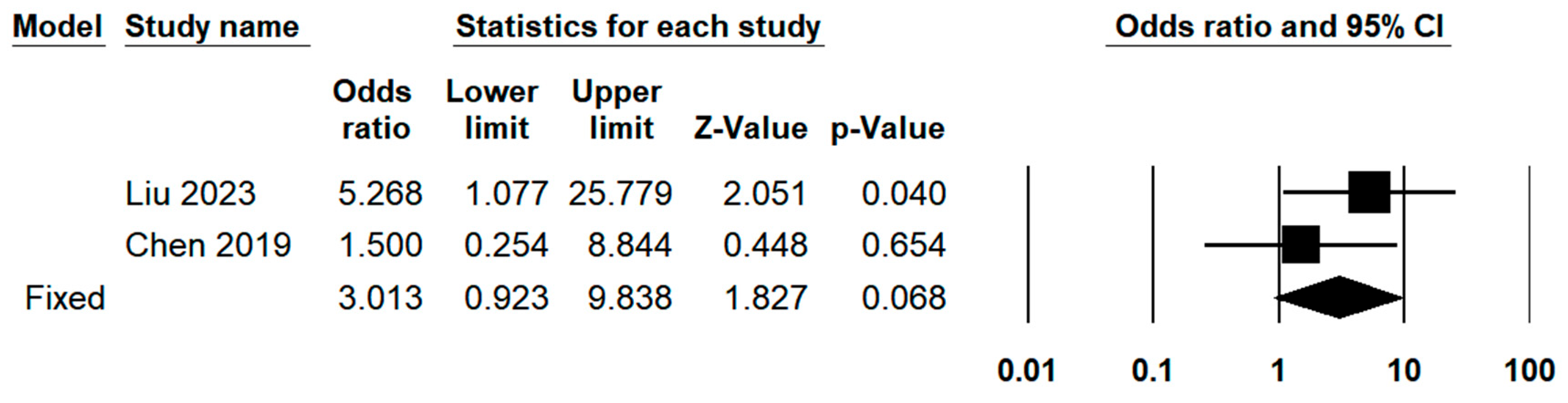

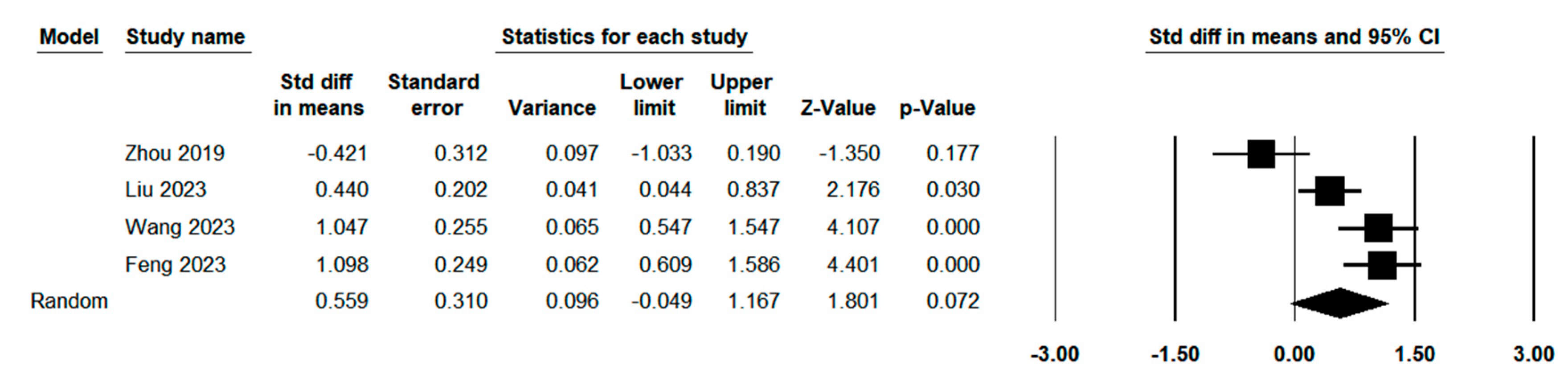

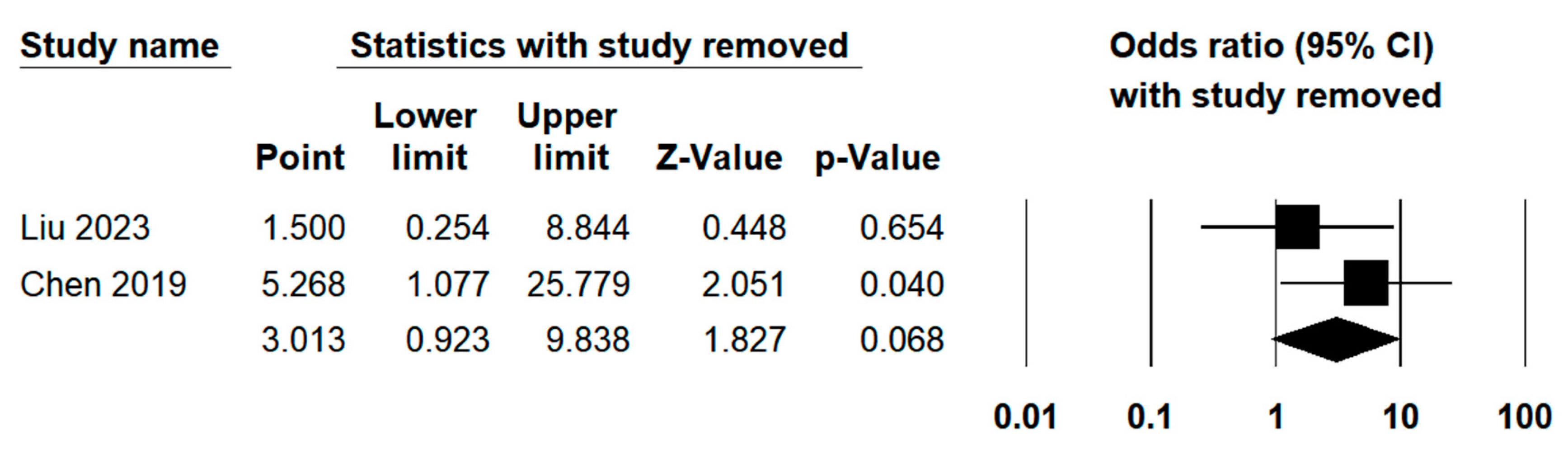

3.3.5. Pathological Outcomes Between Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Laparoscopy Group and Conventional Laparoscopy Group

3.3.6. Meta-Regression Analysis

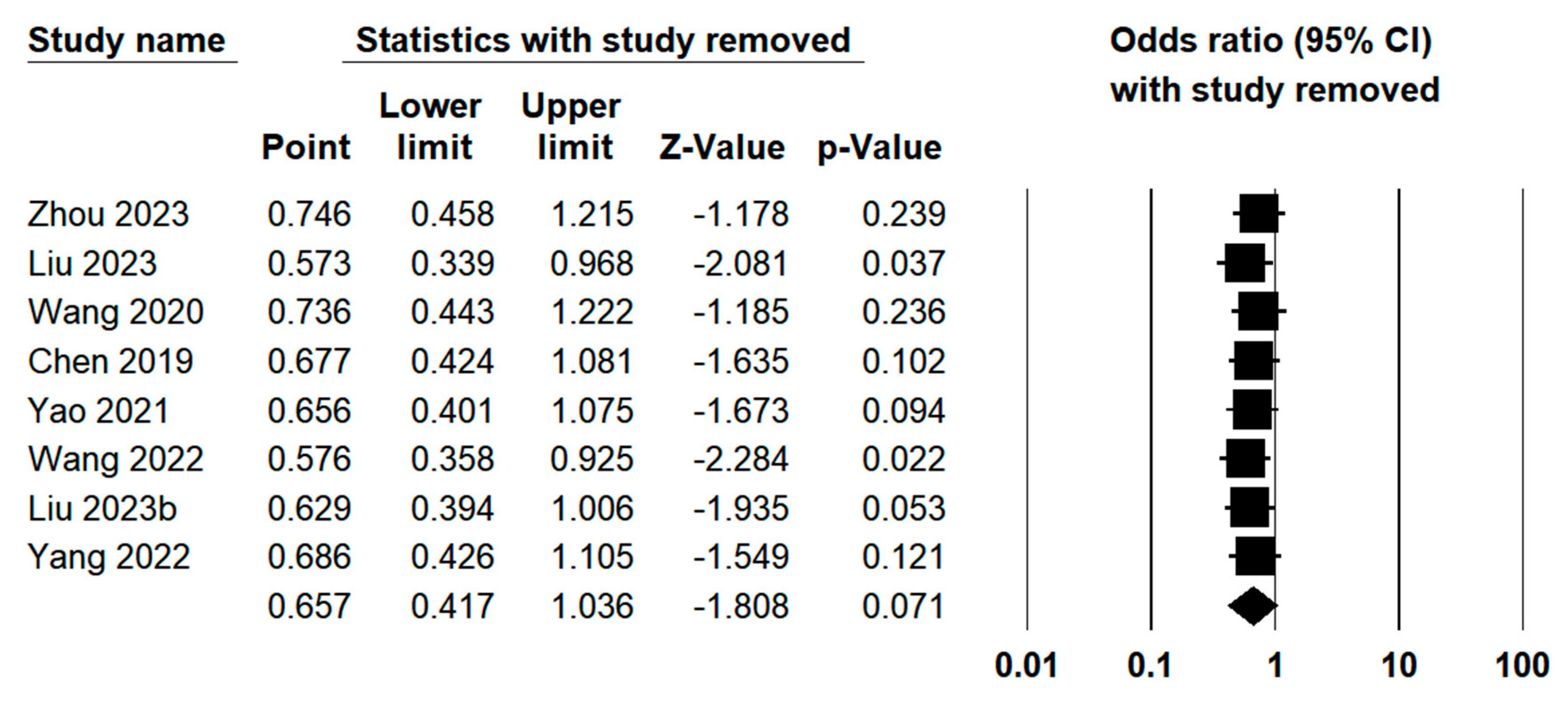

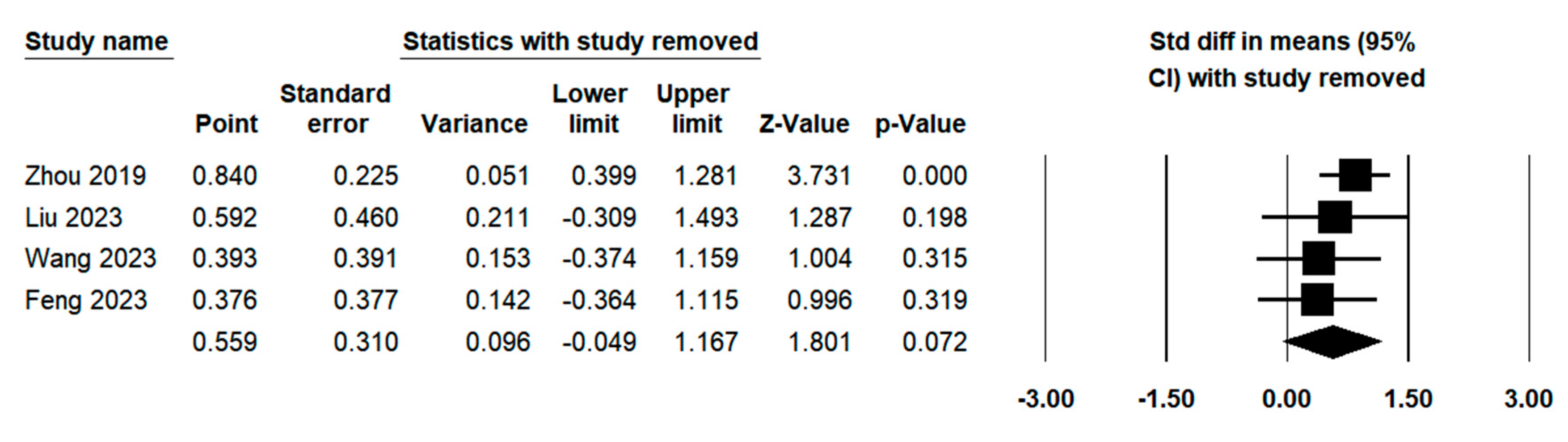

3.3.7. Sensitivity Analysis

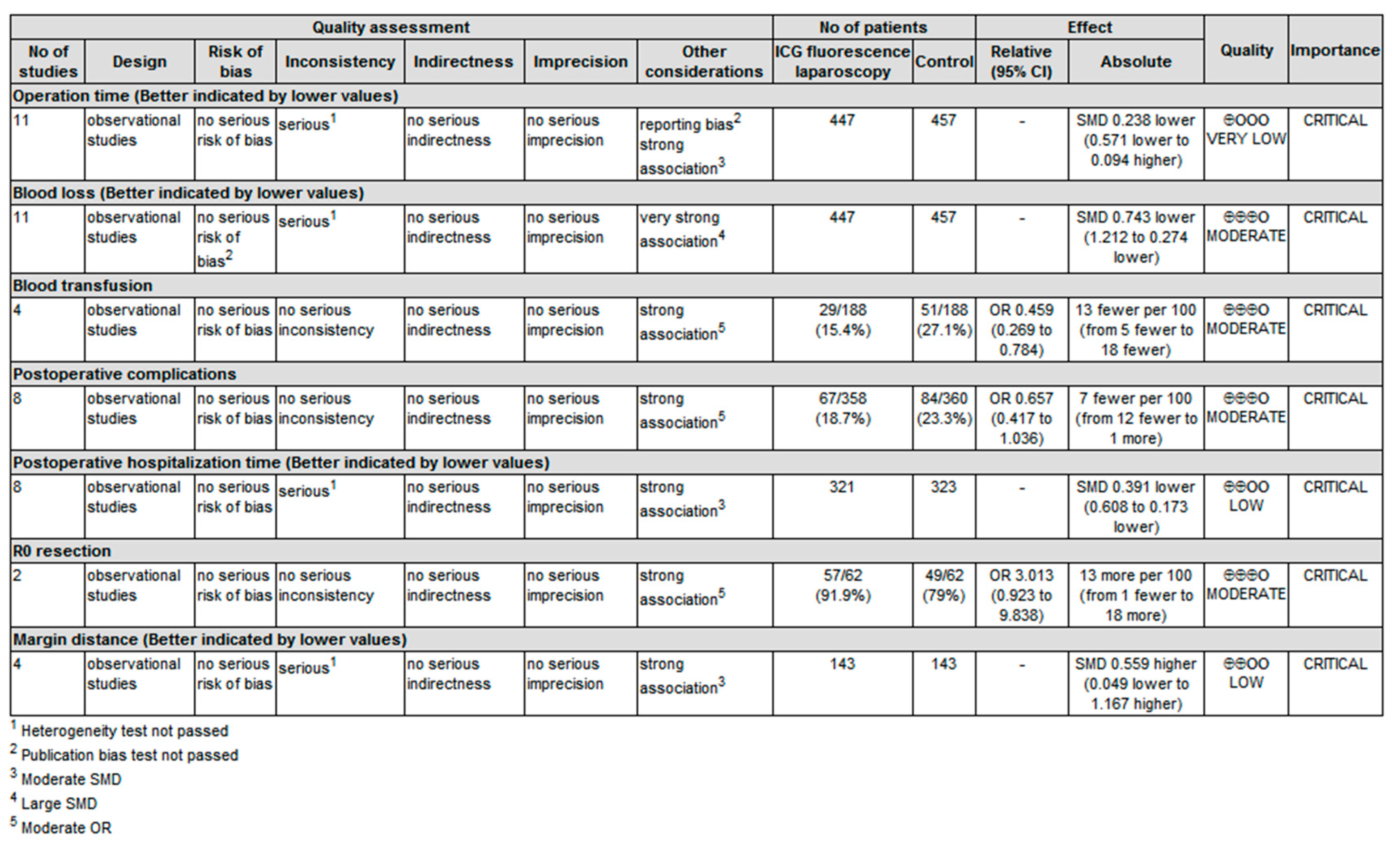

3.3.8. Evidence Quality Examination

3.4. Qualitative Systematic Review of Prognosis Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Sung, H.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71 209–249. 71.

- Llovet, J.M.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, M.; et al. New frontiers in liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep 2020, 2, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glantzounis, G.K.; et al. The role of liver resection in the management of intermediate and advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma. A systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018, 44, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G., F. Kanwal, and J.M. Llovet, Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023 20, 864–884.

- Pang, T.C. and V. World J Hepatol 2015, 7, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; et al. Progress on the molecular mechanism of portal vein tumor thrombosis formation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Cell Res 2023, 426, 113563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuuchi, M., H. Hasegawa, and S. Yamazaki, Ultrasonically guided subsegmentectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet, 1985, 161, 346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Shindoh, J.; et al. Complete removal of the tumor-bearing portal territory decreases local tumor recurrence and improves disease-specific survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2016, 64, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garancini, M.; et al. Non-anatomical liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: the SegSubTe classification to overcome the problem of heterogeneity. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; et al. Anatomical vs nonanatomical liver resection for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021, 13, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.W.; et al. Effect of anatomical liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2023, 109, 2784–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M. and A. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zeindler, J.; et al. Anatomic versus non-anatomic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma-A European multicentre cohort study in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients. Cancer Med 2024, 13, e6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevarez, N.M. and A. Hepatoma Research 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Shindoh, J.; et al. The intersegmental plane of the liver is not always flat--tricks for anatomical liver resection. Ann Surg 2010, 251, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harimoto, N.; et al. Laparoscopic hepatectomy and dissection of lymph nodes for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Case report. Surg Endosc 2002, 16, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croome, K.P. and M. Arch Surg 2010, 145, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; et al. Approaches of laparoscopic anatomical liver resection of segment 8 for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study of short-term results at multiple centers in China. Int J Surg 2023, 109, 3365–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; et al. Theory and technical practice of anatomic liver resection based on portal territory for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Digestive Surgery 2022, 21, 591–597. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, H.; et al. Segmentectomy of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2012, 19, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., J. Cao, and J. JAMA Surg 2024.

- Surgery, >E.B.o.C.J.o.D. Surgery;, E.B.o.C.J.o.D. and S.f.H.-p.-b.S.o.C.R.H. Association, Chinese expert consensus on the theoretical and technical system of laparoscopic portal terri-tory staining guided anatomic liver resection (2023 edition). 22, 2023; 22. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.D.; et al. Minimally invasive donor hepatectomy, systemic review. Int J Surg 2020, 82S, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Real-Time Navigation Guidance Using Fusion Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging in Laparoscopic Non-Anatomical Hepatectomy of Hepatocellular Carcinomas at Segments 6, 7, or 8 (with Videos). Med Sci Monit 2019, 25, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Effects of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging of laparoscopic anatomic liver resection for HCC: a propensity score-matched study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2023, 408, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Navigation- Versus Conventional-Laparoscopic Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-Matched, Retrospective, Cohort Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2023, 30, 1991–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Liangliang, Y.B.Z.W. , Comparison of fluorescent laparoscopic hepatectomy and conventional laparoscopic hepatectomy in the treatment of patients with HCC. Journal of Practical Hepatology 2020, 23, 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; et al. Clinical analysis on safety and efficacy of ICG real-time fluorescence imaging in laparoscopic hepatectomy of HCC at special location. Medical Journal of Chinese People's Liberation Army 2019, 44, 336–340. 44.

- Yao, C. , Application of ICG fluorescence imaging in laparoscopic hepatectomy for primary liver cancer. 2021, Bengbu Medical University.

- Jianxi, W.; et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided laparoscopic hepatectomy versus conventional laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A single-center propensity score matching study. Front Oncol 2022, 12, p. 9300; 65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Clinical study of indole green fluorescence navigation in laparoscopic liver tumor resection. 2020, China Medical University.

- Wang, S., J. Li, and W. The Practical Journal of Cancer 2023, 38, 443–446. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B. , Clinical value of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in laparoscopic curative resection of liver cancer. 2023, Jilin University.

- Guo, C.; et al. Application of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging technique in laparoscopic hepatectomy. Journal of Laparoscopic Surgery 2021, 26, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; et al. Application of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imageguided Laparoscopic Hepatectomy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Inner Mongolia Medical Journal 2023, 55, 659–662. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. , Application of indocyanine green fluorescence in hepatectomy of complex segment hepatocellular carcinoma. 2022, Zunyi Medical University.

- Hong, S.K.; et al. Pure Laparoscopic Donor Hepatectomy: A Multicenter Experience. Liver Transpl 2021, 27, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; et al. Application Effect of ICG Fluorescence Real-Time Imaging Technology in Laparoscopic Hepatectomy. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 819960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotohda, N.; et al. Expert Consensus Guidelines: How to safely perform minimally invasive anatomic liver resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2022, 29, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamoto, T. and M. Cancer Biol Med 2019, 16, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardi, G.; et al. Parenchymal Sparing Anatomical Liver Resections With Full Laparoscopic Approach: Description of Technique and Short-term Results. Ann Surg 2021, 273, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; et al. Laparoscopic anatomical portal territory hepatectomy using Glissonean pedicle approach (Takasaki approach) with indocyanine green fluorescence negative staining: how I do it. HPB (Oxford) 2021, 23, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, G.; et al. The Applications of 3D Imaging and Indocyanine Green Dye Fluorescence in Laparoscopic Liver Surgery. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; et al. Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Navigation in Liver Surgery: A Systematic Review on Dose and Timing of Administration. Ann Surg 2022, 275, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P.A.; et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery: comprehensive review. BJS Open 2023, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; et al. Anatomical Liver Resections Guided by 3-Dimensional Parenchymal Staining Using Fusion Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging. Ann Surg 2015, 262, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging to localize insulinoma and provide three-dimensional demarcation for laparoscopic enucleation: a retrospective single-arm cohort study. Int J Surg 2023, 109, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiloglou, M.; et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence image processing techniques for breast cancer macroscopic demarcation. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroyoshi, J.; et al. Identification of Glisson's Capsule Invasion During Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastasis by Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography Using Perflubutane. World J Surg 2021, 45, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, H.; et al. Real-time Navigation for Liver Surgery Using Projection Mapping With Indocyanine Green Fluorescence: Development of the Novel Medical Imaging Projection System. Ann Surg 2018, 267, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; et al. Perioperative and Disease-Free Survival Outcomes after Hepatectomy for Centrally Located Hepatocellular Carcinoma Guided by Augmented Reality and Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging: A Single-Center Experience. J Am Coll Surg 2023, 236, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; et al. Laparoscopic Anatomical Portal Territory Hepatectomy with Cirrhosis by Takasaki's Approach and Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Navigation (with Video). Ann Surg Oncol 2020, 27, 5179–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; et al. Effects of Anatomical or Non-Anatomical Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma on Survival Outcome. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; et al. Clinical values of total laparoscopic liver resections:with experiences of 123 cases. Journal of laparoscopic surgery 2006, 479–481. [Google Scholar]

- Darido, E.F. and T. World J Surg 2011, 35, 2594–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.H.; et al. Laparoscopic liver resection versus open liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: 3-year outcomes of a cohort study with propensity score matching. Surg Oncol 2020, 33, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Author (Year) | Study design | Total Sample size | ICG sample size | CL sample size |

| 1 | Zhou 201926 | Retrospective study | 42 | 21 | 21 |

| 2 | Zhou 202327 | Retrospective study | 72 | 36 | 36 |

| 3 | Liu 202328 | Retrospective study | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| 4 | Wang 202029 | RCT | 148 | 74 | 74 |

| 5 | Chen 201930 | RCT | 24 | 12 | 12 |

| 6 | Yao 202131 | Retrospective study | 118 | 56 | 62 |

| 7 | Wang 202232 | Retrospective study | 162 | 81 | 81 |

| 8 | Wang 2020b33 | Retrospective study | 24 | 8 | 16 |

| 9 | Wang 202334 | RCT | 70 | 35 | 35 |

| 10 | Feng 202335 | Retrospective study | 74 | 37 | 37 |

| 11 | Guo 202136 | Retrospective study | 35 | 11 | 24 |

| 12 | Liu 2023b37 | Retrospective study | 52 | 28 | 24 |

| 13 | Yang 202238 | Retrospective study | 42 | 21 | 21 |

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure |

| Zhou 2019 | *** | ** | *** |

| Zhou 2023 | *** | ** | ** |

| Liu 2023 | *** | ** | *** |

| Yao 2021 | *** | * | *** |

| Wang 2022 | *** | ** | *** |

| Wang 2020b | *** | * | ** |

| Feng 2023 | *** | ** | *** |

| Guo 2021 | *** | * | *** |

| Liu 2023b | *** | * | ** |

| Yang 2022 | *** | * | ** |

| Variables | N | Publication Bias | Heterogeneity Test | |||

| P value for rank correlation test | P value for regression intercept | I2 | Q | P | ||

| Basic Characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 11 | 0.815 | 0.890 | 17.02% | 12.052 | 0.282 |

| Gender | 10 | 0.929 | 0.441 | 0.00% | 5.937 | 0.746 |

| ASA | 3 | 0.602 | 0.591 | 0.00% | 0.788 | 0.674 |

| HBV infection | 7 | 0.881 | 0.776 | 0.00% | 1.733 | 0.943 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 9 | 0.677 | 0.984 | 0.00% | 2.315 | 0.970 |

| Child-Pugh classification | 6 | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.00% | 0.882 | 0.972 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 9 | 0.404 | 0.466 | 79.43% | 38.889 | <0.001 |

| Operative outcomes | ||||||

| Operation time (min) | 11 | 0.036 | 0.043 | 82.77% | 58.025 | <0.001 |

| Blood loss (ml) | 11 | 0.312 | 0.370 | 90.82% | 108.948 | <0.001 |

| Blood transfusion | 4 | 0.174 | 0.210 | 0.00% | 1.107 | 0.775 |

| Postoperative outcomes | ||||||

| Complication | 8 | 0.805 | 0.767 | 12.10% | 7.964 | 0.336 |

| Postoperative hospitalization (day) |

8 | 0.108 | 0.109 | 43.13% | 12.308 | 0.091 |

| Pathological outcomes | ||||||

| R0 resection | 2 | 6.49% | 1.069 | 0.301 | ||

| Margin distance (mm) | 4 | 0.497 | 0.667 | 83.68% | 18.385 | <0.001 |

| Moderator | Operation time | Blood loss | Margin distance | ||||||

| β | P | I2 | β | P | I2 | β | P | I2 | |

| Age | 0.114 | 0.063 | 74.53% | 0.014 | 0.880 | 88.94% | |||

| Gender | 0.010 | 0.027 | 73.52% | 0.003 | 0.688 | 87.11% | |||

| ASA | -0.007 | 0.945 | 93.44% | ||||||

| HBV status | 0.006 | 0.270 | 83.69% | 0.003 | 0.698 | 88.87% | |||

| Liver cirrhosis status | 0.009 | 0.370 | 87.38% | 0.004 | 0.727 | 88.41% | |||

| Child-Pugh classification | 0.013 | 0.199 | 78.83% | -0.012 | 0.438 | 90.45% | |||

| Tumor size | -0.325 | 0.478 | 84.87% | ||||||

| Study type: RCT | 0.047 | 0.919 | 84.48% | -1.180 | 0.021 | 86.13% | 0.655 | 0.402 | 86.22% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).