Phages are bacterial viruses with either double (ds) or single stranded DNA or RNA genomes. Phage particles, representing a genome encased within a capsid of protein, represent the predominant form of genetic biomass on earth. Those with ds DNA genomes are estimated at >10

31 [

1], or by simplistic analogy 20 billion particles per mm

2 of the earth’s surface. Overall, the many phage types represent an enormous and diverse gene pool in constant change, attributable to recombinational events arising within an infected host cell, for example by exchanging parts a) with prophage or prophage fragments integrated within the chromosome of the infected cell, b) with extrachromosomal elements (as plasmids or phage genomes) within the host cell, or c) with coinfecting phage genomes injected in parallel into the host cell. Phage can encode genetic traits (lysogenic traits) that allow the phage genome to stably coexist within its host cell without killing it (

i.e., the temperate phage). These temperate phage genomes undergo a decision, upon entering a host cell, to either stably associate within the host or undergo a lytic cycle to kill the host and release progeny as phage particles. Other phage types (the lytic phage) lack lysogenic traits. They may encode highly toxic substances causing death/lysis of the infected cell and only undergo a lytic cycle. Humans have evolved in the constant presence of this biomass and yet there is no known human disease linked to direct phage exposure, even though phages clearly play a role in the evolution of bacterial pathogens [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Phage Therapy (PT). PT depends upon the specificity of a phage particle to bind to and infect (inject its genome) into its pathogenic bacterial target, where surrounding non-target bacterial cells escape infection. Aside from killing the target cell, it is anticipated that the PT agent will reproduce within the target cells and the progeny particles will be released during their lysis, increasing its concentration. The infection is self-limiting, persisting only as long as an infectable form of the pathogen remains. On the downside, PT has the potential to release endotoxin from lysed Gram-negative cells. The rationale for PT assumes a) that predator phages (perhaps a cocktail of different infectious types) that infect a form of pathogenic bacterium can be selected and purified from natural sources (

e.g., from sewage) and concentrated; and b) a cocktail of phages (with differing infective mechanisms) can be introduced within a complex milieu (animal infected by pathogenic bacterium) and effect a reduction or elimination of the pathogen. Administration routes for PT include subcutaneous, nasal, oral, skin patch and intramuscular. PT was first employed in 1919, shortly after the discovery of bacterio

phages [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], and a few recent strategies for PT in wound care and infection include [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Challenges administering phages to animals include bacterial target cell infectivity and host organism response. Avid proponents of PT argue for exclusive use of lytic, rather than temperate phages because their primary objective is cell killing. However, a null mutation within an essential lysogeny gene can turn a temperate phage into one that grows lytically,

i.e. has lost its temperate property.

Infectivity: The dependence of PT on lytic phage infectivity includes several caveats: i) Lytic phage growth, often dependent on headful packaging can move genetic material horizontally from the last cell infected into the next infected cell (general transduction). ii) The sensitivity of the target host cell to phage is dependent upon both the phage host-cell range (infectability)

and the ability of an infected host to provide for/support phage reproduction (

i.e. everything the phage genome does not encode). In combination, this represents a large genetic target for the appearance of mutations that block phage growth. Resistant cells (especially attachment mutants) will show no intermediary sensitivity and grow in the presence of enormous concentrations of the phage to which they were previously sensitive. iii) While using cocktails of phages with differing cell-surface attachment mechanisms for genomic penetration into the same target cell reduces the problem of phage attachment resistance, it increases the risk for gene transduction between cells, and the possibility that phage-phage recombination can produce new recombinant phage during each infection cycle. iv) A huge quantity of a phage lysate (and its disposal) may be necessary for generating phage preps for clinical trials or general use, which is compounded if it is necessary to prepare the lysates on pathogenic host cells.

Response: Systemic phages are rapidly cleared by the immune system. Most phages are highly immunogenic and promote a strong antibody response, “raising fears that PT might be applicable for

in vivo use only once and for a relatively short time per patient because subsequent treatments might see the phage cleared quickly by a strong antibody response” [

23]. Once administered to an animal phages rapidly circulate throughout its tissues [

17,

24], and are removed from the circulation by the spleen, liver and filtering organs of the reticuloendothelial system [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Phages have maintained viability for up to 2-3 weeks in spleen cells [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], indicating they were neither neutralized by antibody nor engulfed by macrophages, but rather passively entrapped (sequestered) [

11,

25]. Viable phages have been detected within 5 min of gastric delivery into mice, suggesting that significant numbers of phages can enter the circulatory system by diffusion, rather than via the lymphatic system [

27]. Phages delivered orally to rabbits were found in the blood plasma and many organs up to 4 days post-administration and persisted in the spleen up to 12 days [

31]. Initial attempts at PT were plagued by obstacles related to poor understanding of phage biology and genetics. The revolution in information and technology since then suggests the early obstacles can be overcome while the ideas remain valuable [

32].

Phage display (PD) systems. PD requires strategies for fusing the coding region for a protein, polypeptide or peptide with a phage surface capsid gene and then displaying the hybrid protein on a virus capsid. The fused polypeptide, perhaps with activity as a ligand, or antigen, can theoretically be designed to join at either the NH2- or COOH- terminal ends of the capsid protein. Display density refers to the extent to which the fused capsid protein can be added to the capsid. Virus particles with only one or a few gene-fusion-display proteins per capsid have low display density, whereas particles displaying perhaps hundreds of fusion proteins have high display density, thus display density can vary from less than one per collection of particles to greater than hundreds per particle. Display densities as low as one or fewer per particle are important in isolating binder-particles with very high affinities for a target ligand; displays of 3 to 10 copies of the fusion-display protein are sufficient to allow isolation of binders to bait when the strength of interaction is in nanomolar to micromolar range. However, for study of weaker interactions (micromolar to millimolar range), the display needs to be on the order of a few hundred fusion proteins per particle [

33]. “Landscape vehicles” [

33], i.e. those which have a very dense display of the candidate peptide on the capsid surface of the phage particle, may be better immunogens for use in live vaccine development and as vehicles for biocatalysis and bio adsorption.

The two main types of PD systems are

filamentous and

lytic as reviewed by [

34]. Filamentous PD was introduced by Smith in 1985 with the typically low density display of peptides fused to one of the low copy capsid proteins at the ends of linear filamentous phage,

e.g., M13 [

35]. This method of PD, referenced many thousands of times, and with numerous clever variations for either cloning the fusion protein within the vector genome or the use of surrogate systems to produce the fusion protein, is based on M13 and related filamentous phages that are released from infected cells by extrusion of phage particles through the cell wall without producing cell lysis. An M13 encoded fusion capsid protein must traverse the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and then be assembled on the phage coat/capsid within the periplasm. This can hinder the display of highly hydrophilic proteins. In contrast,

lytic PD employs either temperate phages, as λ (the focus of this study), or true lytic phages as T4 [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] and T7 [

41] that release (burst) from infected cells by lysing them in terminal stage of the phage growth cycle. Phage particles released by cell lysis theoretically can display hundreds of capsid fusion proteins per particle and in some systems the capsid fusion display protein, prepared separately, can be added to a procapsid structure

in vitro.

The display of peptides and proteins on the capsids of filamentous or lytic phages is a powerful technique for the identification or targeting of specific ligands and can be adapted to generate vaccine reagents [

33,

42,

43,

44]. Potential applications [

33] include the use of display vehicles for targeted gene delivery,

in vivo diagnostics, isolation of tissue-specific peptides, tissue imaging agents (

in vitro and

in vivo), cell targeting [

45], studying the specificities of immune responses of patients with various diseases, cancer therapy, autoimmune disorders and age-related conditions, design of diagnostic assays and therapeutic vaccines, biodetectors for a variety of threat agents (viruses, bacteria, spores, toxins), drug and vaccine delivery to specific cells, and applications involving the use of surface display vehicles as biocatalysts.

λ PD. During phage λ morphogenesis its genomic ds DNA is packaged into a preformed prohead which expands during packaging, exposing sites for increased binding of the capsid head decoration protein gpD (11.4 kDa) to the underlying molecules of protein gpE making up the prohead [

46,

47,

48]. In the process of prohead expansion into a stable mature λ head, about 420 gpD monomers are enzymatically added to the prohead via conversion into 140 gpD

3 trimers, that are affixed to 20 icosahedral faces of the mature particle. The gpD

3 trimer was shown to stabilize the capsid head shell during packaging of the lambda genome [

49,

50]. The addition of gpD to the prohead is dispensable when the 48.5 Kb λ genome includes a deletion of at least 18% [

51]. Cryo-electron microscopy and image reconstruction have shown that the side of the gpD

3 trimer that binds to the capsid is the side on which both the NH2- and COOH- terminal ends reside. Despite this orientation of the gpD trimer, fusion proteins connected by linker peptides to either terminus bind to the capsid, allowing protein and peptide display [

52].

While fusions to gpV, the tail tube protein have been reported [

53,

54], most λ PD reports involve engineered recombination into the λ genome fusing the coding region of a foreign protein/peptide/polypeptide (<) with gene

D, making

D< [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. These studies each anticipate the formation of a viable phage where the chimeric gpD< protein retains gpD functionality and “<” has been fused either to the NH2- or COOH- terminal ends of gpD [

63], or internally within the

D coding sequence [

54]. For gpD< to function similarly to gpD it should not interfere with i) the interaction of gpD or gpD< monomers to form a trimer, or ii) the incorporation of gpD

3 or gpD<

3 trimers on the surface of the λ particle capsid head. If the binding of gpD< is challenged, the expansion of the head is blocked, negating full packaging of the lambda genome, stabilization of lambda particles and the formation of viable phage particles. Diverse proteins have been fused at the N- or C-terminal ends of gpD, including β-galactosidase protein [

63], Cry1Ac toxin from

Bacillus thuringiensis [

64], and the ligand binding domain of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma [LBDPPARγ] [

65]. In the latter example, the solubility of the LBD of PPARγ, which is very prone to protein aggregation was dramatically increased, indicating that generating a gpD-fusion may improve the solubility of proteins which normally clump and precipitate in

E. coli. (See [

66] on using lambda display as a powerful tool for antigen discovery.) Likely, the extent to which genomically encoded gp

D< fusion proteins can form gpD<

3 trimers on lambda capsid heads is limited/varies [

67,

68]. The numbers of fusion proteins displayed by λ appears somewhat size dependent: small peptides of about 10 residues were present at as many as 405 copies per particle, with lower display densities seen for larger gpD< fusions; but overall, phage display on lambda was reported two to three orders of magnitude higher than was displayed by pIII and pVIII fusions on M13 [

67].

Ansuini et al, 2002, were likely the first to circumvent the presence of only having a marginal gpD< fusion in the packaging mix by provisionally supplementing the mix with gpD. They developed a clever licensed vector λD-bio containing two copies of

D, one with a suppressible nonsense (amber) mutation, and a second

D for making gpD< fusions, where the in-frame sequence following the tandem

D included cloning sites

SpeI and

NotI with an intervening ochre termination codon followed by the 13 amino acid sequence recognized by the biotin holoenzyme synthetase BirA. Cloning of out of frame DNA fragments between

SpeI and

NotI nullified synthesis of the downstream peptide recognized by BirA; whereas selection for clones with open reading frames was by streptavidin affinity chromatography. This system, and its derivatives [

54,

69,

70] enabled phage display by co-expression of functional gpD and gpD< gene fusions, however, the recombinant phage tended to accumulate mutations able to block gpD< fusion protein expression, resulting in better phage particle production [

54]. Recalcitrant gene fusion combinations of gpD< blocking phage display were identified which were incompatible with the assembly of stable phage particles [

71,

72], yet the recalcitrant property of gpD< was found suppressible, permitting its display, if a surrogate plasmid system was added that simultaneously produced gpD.

Heat induced λ capsid disassembly yields only soluble gpD monomers, not gpD trimers, suggesting the trimer rapidly dissociates when not attached to the λ head [

73] and gpD remains soluble (does not aggregate) in high molar concentration [

52]. In contrast, in similar treatment, the major capsid protein gpE is easily precipitated and likely exists as aggregates [

73]. Data from phage display by co-expression of functional gpD and gpD< gene fusions tends to suggest that gpD

2gpD< or gpD<

2gpD, or gpD<

3 trimers likely can form on the λ head [

54].

In vitro complementation has been employed to determine if N-terminal, or C-terminal gpD protein fusions will add to a lambda capsid head devoid of gpD. In this system, 10

8 purified λ

Dam15 phage particles (devoid of gpD), with 79.5% of the wild type genome size, are mixed with purified gpD or gpD fusion proteins, to permit addition to the capsid, and then subsequently treated with EDTA (results in expansion of the phage heads devoid of gpD), chelating away Mg

2+. The particle reaction mixture is then mixed with

E. coli cells able to suppress the

Dam15 mutation and resulting phage plaques are counted. Just about any type of N- or C-terminal gpD fusion has been shown to complement for gpD in this assay [

52,

54], where “complementation refers to rendering the phage resistant against EDTA treatment by binding the protein in question to the [purified] λ

D- phage” particles [

52]. Though I may be missing something, these data omitted that the purified λ

Dam15 phage particles (devoid of gpD) with 79.5% λ genomes are already resistant to EDTA, and when plated on an

E. coli suppressor strain will form viable phage plaques (whether or not they were pretreated with EDTA). The critical argument for complementation was that treatments with gpD deleted for 14 N-terminal amino acids complement very poorly. But this could also mean that the NΔ14-gpD protein negatively complements in a reaction that does not require any gpD.

In vivo Complementation assay for gp< activity. In testing whether gpD< fusions will add to head formation in the presence of gpD, or can complement a deficiency in gpD, it is essential to undertake

in vivo complementation assays where the possibility for negative complementation by gpD< is examined. These assays are easily accomplished by a) assessing the efficiency of plating by gpD

+ λ phage on cells where gpD< is being expressed in parallel from a surrogate plasmid, and b) measuring complementation by surrogate expression of gpD< in non-suppressing (nonpermissive) cells infected with λ

Dam phage, and in parallel, measuring the reversion frequency of λ

Dam to λ

D+ as a control. In an

in vivo assay the influence of gpD< expression on culture viability,

i.e. its

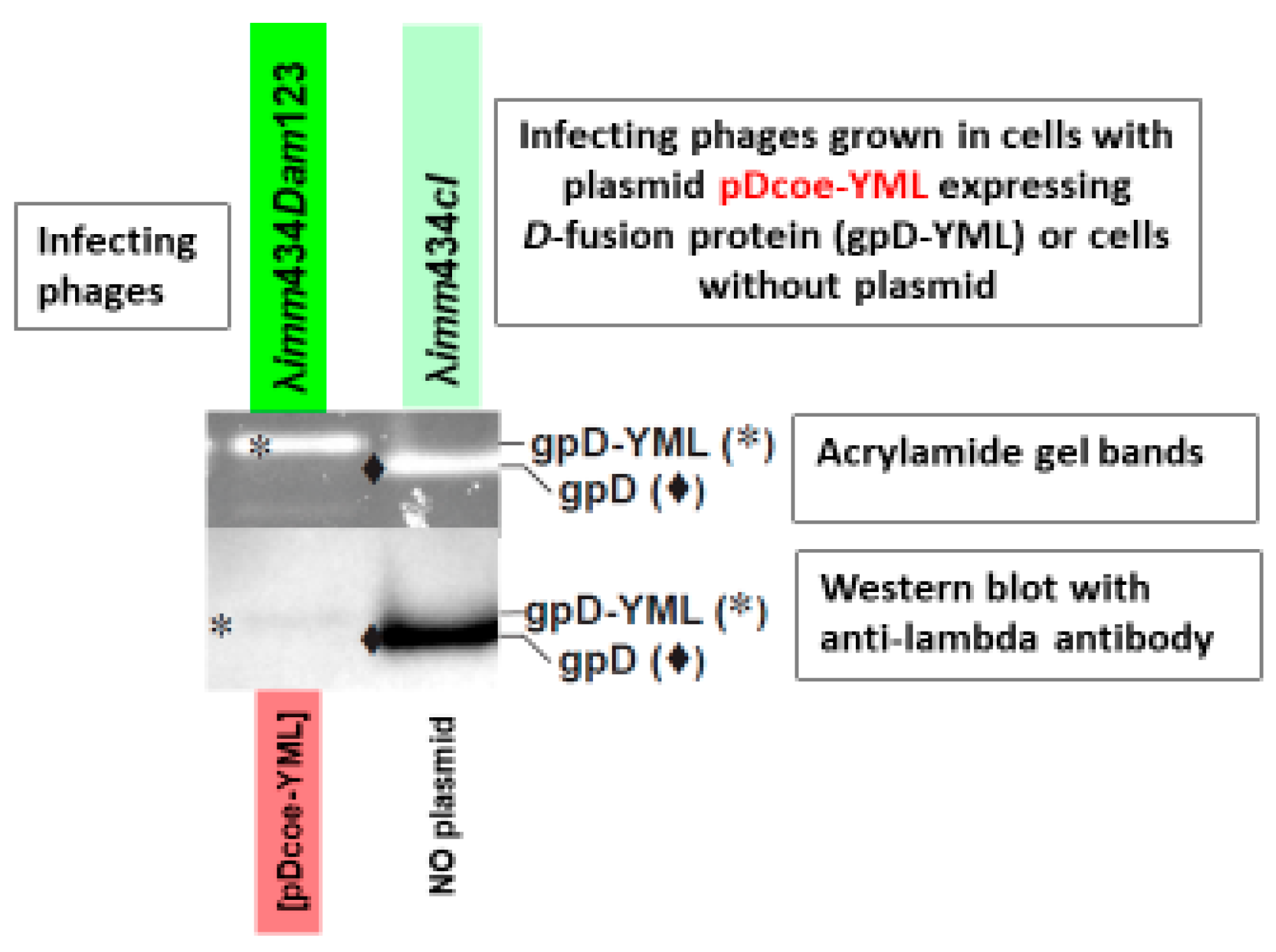

intra-cellular toxicity, is easily examined, as is the relative display density of gpD< on phage particles generated by complementation. Phage particles fully coated with gpD< (left gel lane,

Figure 1) are recovered whenever cells expressing a functional gpD< from a surrogate plasmid are infected with

D-defective phage. In the example, the infecting phages are λ

imm434 and are not sensitive to repression by the λ

immλ CI[Ts]857 repressor encoded on the pcIpR-Dcoe-YMY-timm plasmid.

Phage particles from separate infections were concentrated by differential centrifugation (first to remove cell debris, second after PEG addition, then collecting and resuspending the pellet). Following CsCl banding and dialysis of banded phage particles the preps were submitted to denaturing acrylamide gel electrophoresis. The left gel shows phage particles obtained after infecting non-suppressing

E. coli cells transformed with a plasmid p674 expressing codon optimized gpD-YML with λ

Dam phage. (gpD-YML represents a 17 amino acid C-terminal addition to gpD, including the spacer-GGSGAP joined to 11 amino acids GYMLGSAMSRP representing the disease-specific epitope, termed YML, from the sequence of cervid prion pRp protein [

74].) The reversion frequency for λ

Dam to λ

D+ was less than 10

-5 in an aliquot of the lysate removed before differential centrifugation. The acrylamide gels were treated with Oriole fluorescent stain (Bio-Rad) with UV light excitation. The lower Western blot employed anti-His-gpD mouse antibody with chemiluminescence detection of secondary rabbit anti-mouse IgG (HRP conjugated). This is one of many observations made (see also

Figure 7C) that our His-gpD antibody preps bind well with gpD, but bind very poorly, if at all, with gpD< fusions. The mutation

imm434cI#5 in phage λ

imm434cI#5 (defective in lysogeny) was recombined into

λimm434Dam123 (capable of lysogeny) and single plaque lysates of the recombinant phage

λimm434cI#5Dam123 (A2a, A2b, G1a, G1b), each defective for lysogeny, were employed in future infections (

Figure 5 tubes 3-6) to improve lysate titer.

The

in vivo complementation assay sensitively detects when gpD< proteins provided by the surrogate plasmid are recalcitrant in suppressing the

Dam defect coded by the infecting phage (

Figure 2). Nonpermissive cells with a surrogate plasmid expressing gpD< with a 16 amino acid N-terminal addition (NH2-YML-Dcoe-COOH = MGYMLGSAMSRP-GSGQ

spacer-gpD) failed to complement (absence of phage plaques) the infecting

Dam phage with near wild type genome size. In contrast, similar expression of either gpD (wild type) or gpDcoe (codon optimized) where the YML epitope is fused to the C-terminal end of gpD (=gpD-GGSGAP

spacer-GYMLGSAMSRP both complemented well, permitting plaque formation by the

Dam test phage.

The synthetic plasmid pcIpR-GOI-timm expression vector [

75] positions the cloned gene of interest (GOI) in the position of λ gene

cro (on the phage) and is placed just upstream from a powerful λ terminator

tImm and downstream from λ promoter

pR (regulated by the plasmid encoded temperature sensitive repressor CI[Ts]857). Numerous variations of this expression plasmid have been employed [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79] to vary, thermally, the expression of the cloned GOI from fully off (culture incubation temperatures 25-30

oC) to fully expressed (at 42

OC). When cells with this plasmid are grown at 25 or 30

oC the plasmid encoded CI repressor can prevent the expression of extremely toxic proteins, peptides, or gpD-fusions [

77,

80]. The utility of expressing gene fusions with gpD is that the fusion protein does not aggregate within the cells or on purification. An example is illustrated (

Figure 3) with the 207 amino acid fusion between gpD and epitopes from the Porcine Circovirus 2 capsid protein. We have seen similar results (no aggregation at high concentration) for the 354 amino acid gpD-GFP fusion protein, and others (not shown).

Thermal regulation of the GOI encoded by plasmid pcIpR-GOI-timm is varied by shifting the transformed cells growing at 30

OC to higher temperatures,

Table 1.

Dual display. Once it was realized that both gpD and gpD< can be combined on a lambda particle and that in the absence of gpD some gpD< fusions are incompatible with the assembly of stable phage particles [

71] it was proposed that “dual” gpD expression systems [

75] could be advantaged that eliminated the complex cloning of recombinant

D-fusions into the lambda vector genome, or into a lambda vector with both

D and

Dam genes. The

D-fusion could be induced and expressed from a surrogate plasmid in

E. coli cells while simultaneously infecting the cells either with λ

D+ or λ

Dam phage. In the first instance, both gpD (generated by infecting phage) and gpD< (expression induced from plasmid) would compete in decorating the capsid head of the infecting phage. In the second situation, the head of the infecting λ

Dam phage is fully complemented by the plasmid expressed gpD< fusion protein (

Figure 1). In these assays negative complementation by a gpD< (as seen for the N-terminal addition of the YML epitope to gpD, plasmid p676, pYML-Dcoe) is observed as a reduction in plating of λ

D+ on cells expressing the gpD< fusion protein. Positive complementation is measurable by observing the formation of plaque forming λ

Dam phage on non-amber suppressing cells expressing a plasmid-encoded gpD< fusion.

The ability to vary the expression of gpD< is an important aspect of the dual display system,

i.e., effectively being able to tune the expression of gpD< from the expression plasmid. One might imagine that expressing more gpD (or the gpD< fusion protein) is better for complementation. They would be wrong. In retrospect, our ability to produce phage particles displaying gpD-CAP ([

75,

76] likely only worked because we were unable to raise the incubator room induction temperature above 38

oC. Even quite low levels of gpD expression from plasmid at 37

oC (compare to

Table 1) can suppress the

D-defect of an infecting phage,

Figure 4.

Potential use of Lambda Display Particles (LDP) as vaccine reagents. LDP can be prepared by infecting cells expressing gpD< gene fusion proteins with either λ

D+ or λ

D- phage lysates (

Figure 5). When infecting only with λ

D- phage, only phage coated with gpD< are produced (see

Figure 1). The ability to simultaneously produce multiple LDP in the same infection,

Figure 5 (band in 6), allows the possibility for producing multivalent reagent preparations in the same reaction and permits the hypothesis for rapid production of multiple single epitope vaccine methodology (

Figure 6).

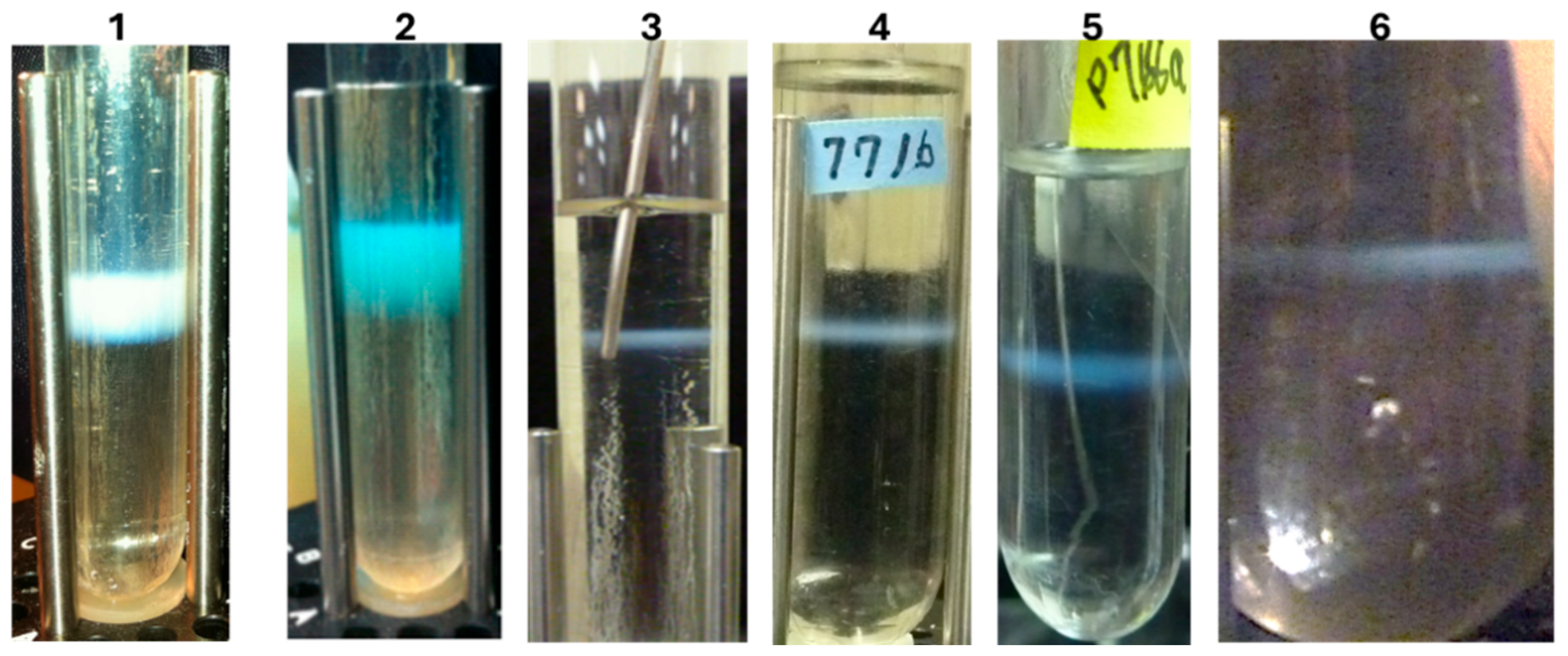

Figure 5.

CsCl banding of LDP lysate preparations made by infecting nonpermissive host cells transformed with pcIpR[ ]timm plasmids expressing gpD< gene fusions and carrying out the infections at 37

oC in Lauria-Bertani (LB) broth (10 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g Bacto yeast extract,5 g NaCl per liter), made 50 ug/ml with ampicillin, in a shaking water bath. Banded lambda display particles (LDP) prepared from cultures expressing gpD< within the infected cells:

1. Display of gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 (251 amino acid fusion protein, see

Figure 7); 12 liters early log phase cells were infected with λ

imm434cI#5; single burst (as described [

80], band titer 1.64x10

10 particles/ul. 2. Display of gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 (241 amno acids fusion protein, see

Figure 7); 12 liters early log cells cells infected with λ

imm434cI#5; single burst, band titer 1.64x10

10 particles/ul. 3. gpDcoe-YML (C-terminal fusion of gpD to 17 amino acids including YML epitope from prion protein pRp); from infection of cells at MOI 0.1 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123; shown second banding of phage recovered per two-liter lysate, band titer 2.63x10

10 particles per ul.

4. gpD-RBD#1 (fusion of Dcoe at C-terminal to spacer and 14 amino acids (#’s 443-456) from 2019-nCoV [

81] capsid receptor binding domain for spike protein to human lung epithelial ACE2 protein); from infection of cells (grown overnight to stationary phase, pelleted and resuspended in TM buffer [0.01 M Tris, 0.01M MgCl2, pH 7.8]), mixed and incubated 30 min at 35

oC at MOI of 0.04 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123 (reversion frequency = 4.2x10

-6); shown second banding of phage recovered per two-liter lysate: 8.93x10

12 viable particles per 7x10

8 input phage = 1.27x10

4 amplification/input phage to infection.

5. gpD-RBD#2 (fusion of Dcoe at C-terminal to spacer and 13 amino acids (#’s 482-494) from 2019-nCoV capsid receptor binding domain); cells infected at MOI of 0.04 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123; shown second banding of phage recovered per two-liter lysate: 1.08x10

13 viable particles per 7x10

8 input phage = 1.53x10

4 amplification/input phage to infection.

6. Trivalent infection: This comprised a mix (0.34 ml of each) of the three cell types grown at 30

oC overnight, pelleted, concentrated two-fold and suspended in TM buffer. Each separate cell aliquot was infected at MOI of 0.04 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123, held at 35

oC for 30 min, and the mixture pipetted into a liter of LB broth (done in duplicate, yielding two liters of lysate). The cell titers for the culture cells was determined simultaneously: 594[gpD-RBD#1] (1.14x10

9 cfu/ml), 594[gpD-RBD#2] (5.95x10

8 cfu/ml) and 594[gpD-RBD#3] (fusion of Dcoe at C-terminal to spacer and 11 amino acids (#496-506) from 2019-nCoV capsid receptor binding domain) at 1.38x10

9 cfu/ml. Shown is first banding (larger centrifuge tube than used in

1-5) of phage output recovered per two liters of lysate: 6.47x10

12 viable particles per 7x10

8 input phage = 9.22x10

3 amplification/input phage to infection.

Figure 5.

CsCl banding of LDP lysate preparations made by infecting nonpermissive host cells transformed with pcIpR[ ]timm plasmids expressing gpD< gene fusions and carrying out the infections at 37

oC in Lauria-Bertani (LB) broth (10 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g Bacto yeast extract,5 g NaCl per liter), made 50 ug/ml with ampicillin, in a shaking water bath. Banded lambda display particles (LDP) prepared from cultures expressing gpD< within the infected cells:

1. Display of gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 (251 amino acid fusion protein, see

Figure 7); 12 liters early log phase cells were infected with λ

imm434cI#5; single burst (as described [

80], band titer 1.64x10

10 particles/ul. 2. Display of gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 (241 amno acids fusion protein, see

Figure 7); 12 liters early log cells cells infected with λ

imm434cI#5; single burst, band titer 1.64x10

10 particles/ul. 3. gpDcoe-YML (C-terminal fusion of gpD to 17 amino acids including YML epitope from prion protein pRp); from infection of cells at MOI 0.1 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123; shown second banding of phage recovered per two-liter lysate, band titer 2.63x10

10 particles per ul.

4. gpD-RBD#1 (fusion of Dcoe at C-terminal to spacer and 14 amino acids (#’s 443-456) from 2019-nCoV [

81] capsid receptor binding domain for spike protein to human lung epithelial ACE2 protein); from infection of cells (grown overnight to stationary phase, pelleted and resuspended in TM buffer [0.01 M Tris, 0.01M MgCl2, pH 7.8]), mixed and incubated 30 min at 35

oC at MOI of 0.04 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123 (reversion frequency = 4.2x10

-6); shown second banding of phage recovered per two-liter lysate: 8.93x10

12 viable particles per 7x10

8 input phage = 1.27x10

4 amplification/input phage to infection.

5. gpD-RBD#2 (fusion of Dcoe at C-terminal to spacer and 13 amino acids (#’s 482-494) from 2019-nCoV capsid receptor binding domain); cells infected at MOI of 0.04 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123; shown second banding of phage recovered per two-liter lysate: 1.08x10

13 viable particles per 7x10

8 input phage = 1.53x10

4 amplification/input phage to infection.

6. Trivalent infection: This comprised a mix (0.34 ml of each) of the three cell types grown at 30

oC overnight, pelleted, concentrated two-fold and suspended in TM buffer. Each separate cell aliquot was infected at MOI of 0.04 with λ

imm434cI#5Dam123, held at 35

oC for 30 min, and the mixture pipetted into a liter of LB broth (done in duplicate, yielding two liters of lysate). The cell titers for the culture cells was determined simultaneously: 594[gpD-RBD#1] (1.14x10

9 cfu/ml), 594[gpD-RBD#2] (5.95x10

8 cfu/ml) and 594[gpD-RBD#3] (fusion of Dcoe at C-terminal to spacer and 11 amino acids (#496-506) from 2019-nCoV capsid receptor binding domain) at 1.38x10

9 cfu/ml. Shown is first banding (larger centrifuge tube than used in

1-5) of phage output recovered per two liters of lysate: 6.47x10

12 viable particles per 7x10

8 input phage = 9.22x10

3 amplification/input phage to infection.

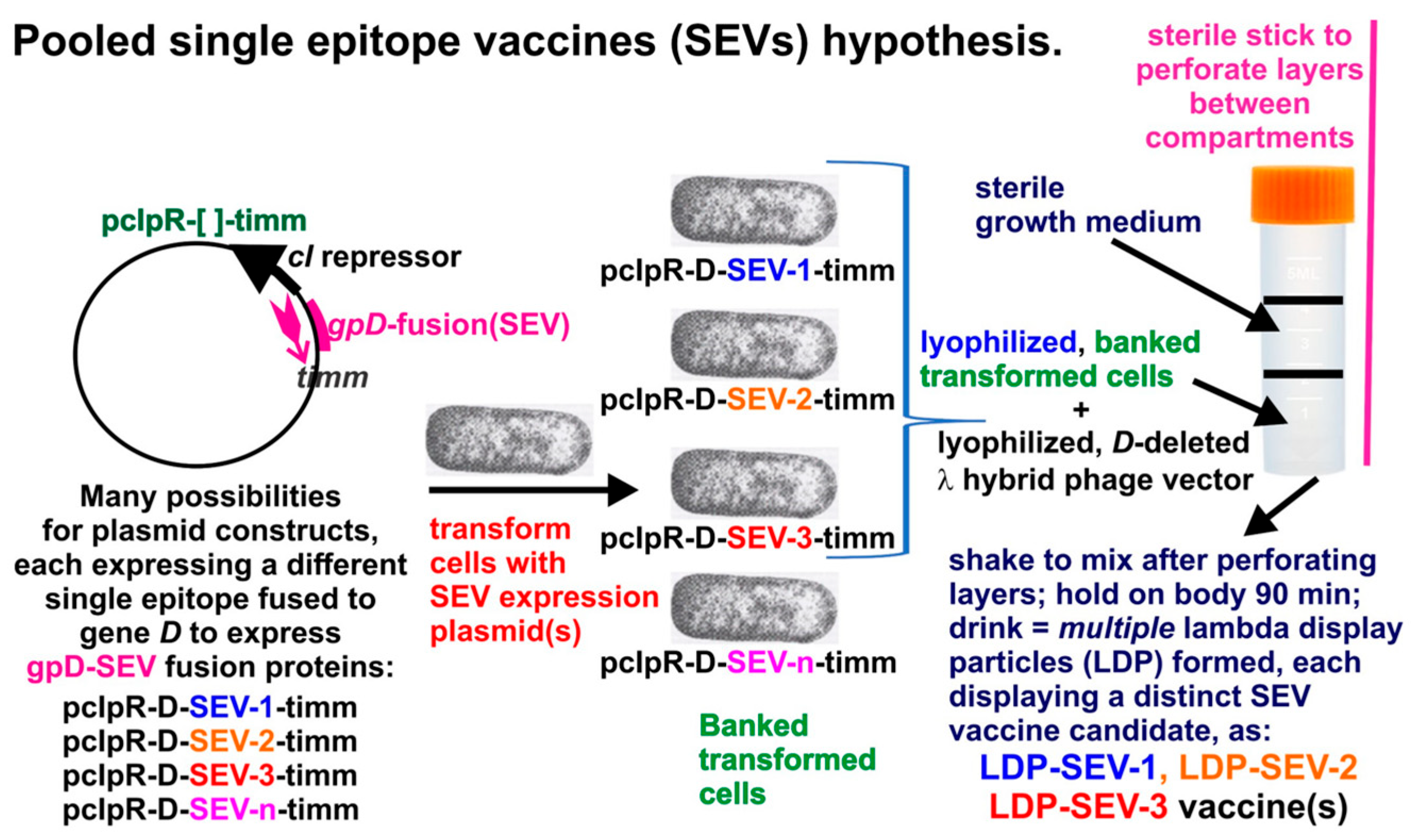

Figure 6.

Multiple, fully gpD<-coated phage particles (LDP) can be produced in a single infection. This hypothesis is based on the result for simultaneously producing three phage particles, each displaying a distinct disease specific epitope [

81] of the capsid spike protein of the SARS coronavirus (shown

Figure 5, band 6). Of note, the patented, ingestible

E. coli Nissle 1917 strain (EcN) [GmbH/Pharma-Zentrale GmbH, 58313 Herdecke/Germany] has been described [

82] and assuming if a λ-sensitive variant was available/obtainable, it might become a useful host strain.

Figure 6.

Multiple, fully gpD<-coated phage particles (LDP) can be produced in a single infection. This hypothesis is based on the result for simultaneously producing three phage particles, each displaying a distinct disease specific epitope [

81] of the capsid spike protein of the SARS coronavirus (shown

Figure 5, band 6). Of note, the patented, ingestible

E. coli Nissle 1917 strain (EcN) [GmbH/Pharma-Zentrale GmbH, 58313 Herdecke/Germany] has been described [

82] and assuming if a λ-sensitive variant was available/obtainable, it might become a useful host strain.

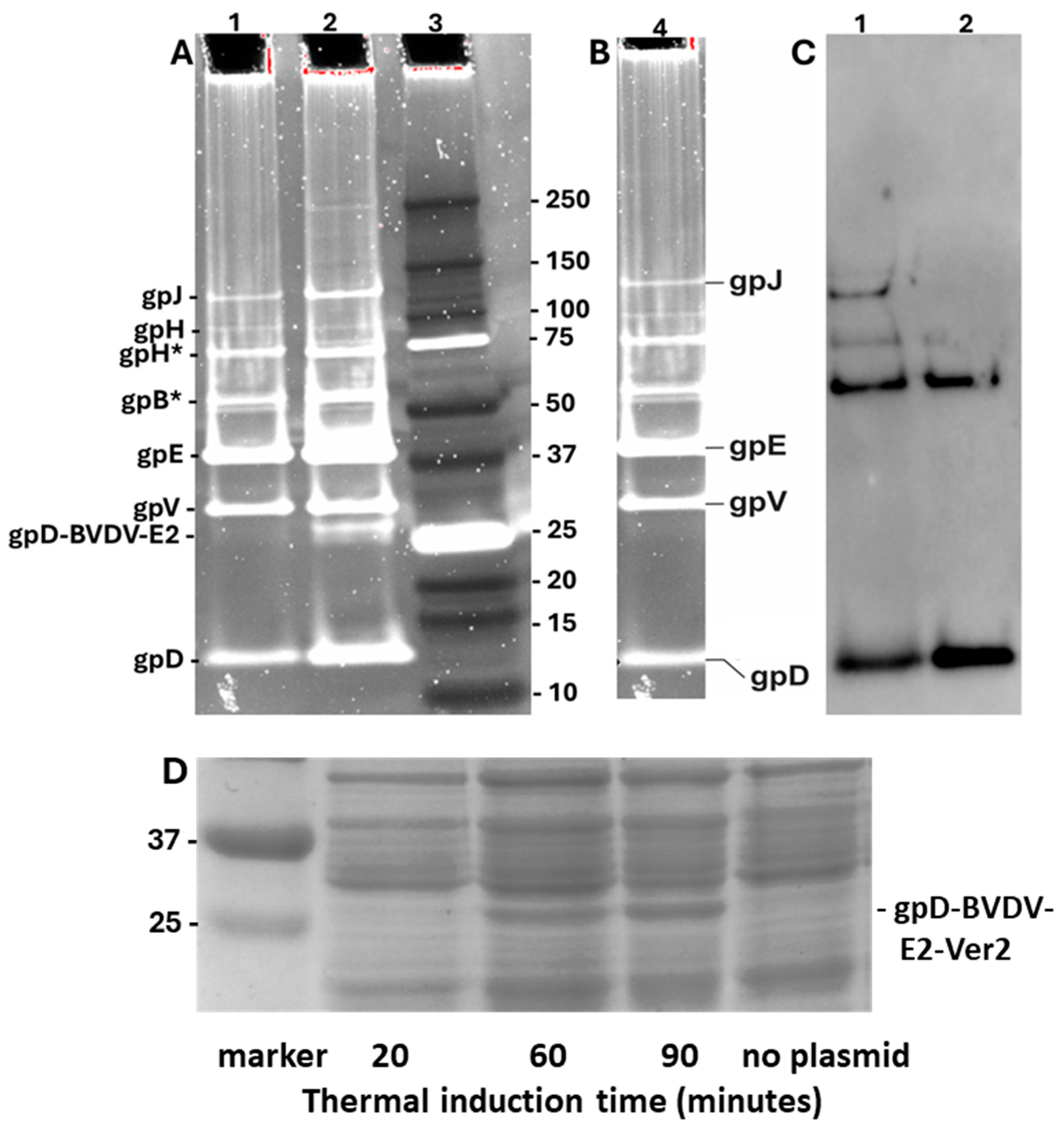

In addition to our earlier studies [

76] with the Porcine Circovirus capsid fusion gpD-CAP, we explored whether other complex gpD< fusion proteins could be added to the λ capsid head in the presence of gpD

+.

E. coli cells expressing gpD-fusions to epitopes from Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus 2 (BVDV2) E2 capsid protein were infected with λ

imm434cI#5, i.e., a D+ phage. The phage particles from CsCl bands shown in lanes 1 (gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2) and 2 (gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3),

Figure 5, were dialysed, diluted and run on denaturing acrylamide gels, respectively,

Figure 7A, lanes 1 and 2. In parallel, CsCl-banded λ

imm434cI#5 phage particles obtained upon infecting nonpermissive W3350 cells with no plasmid, were diluted, dialyzed, and run on equivalent denaturing acrylamide gel, shown in

Figure 7B. The phage bands are labeled as suggested in Figure 1 of [

83]. Phage λ

imm434cI#5 does not appear to encode either of the tail fiber genes

tfa or

stf [

84]. Both the Ver2 and Ver3 show an extra band, presumed to be 248 amino acid gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 (lane 1) and 238 amino acids gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 (lane 2). These gpD-fusion bands Ver2 and Ver3 are totally absent in the particles from infection of cells without a plasmid by λ

imm434cI#5 (

Figure 7B, lane 4; examine region below the band for gpV). Assuming all 420 gpD binding sites are occupied on the phage particles (

Figure 5 tubes 1 and 2 obtained from the infections of cells with expression plasmids), possibly 65 binding sites for gpD may be occupied by gpD-BVDV2-Ver3. The Ver3 gpD fusion display protein was 10 amino acids shorter than the Ver2 variant that included the additional (problematic?) 79-88 amino acid loop present in the BVDV2 E2 protein (legend,

Figure 7). This suggests increased “recalcitrance” in capsid head binding by fusion protein gpD-BVDV-E2-Ver2 compared with gpD-BVDV-E2-Ver3, since the gel,

Figure 7D, clearly shows there is a high level of gpD-BVDV-E2-Ver2 expression from the induced plasmid, implying it was available for binding to the head. The Western blot (

Figure 7C) of lanes 1 and 2 (

Figure 7A), employing anti-His-gpD mouse antibody (made to the His-tagged-gpD), revealed strong binding to gpD, and to higher molecular weight aggregates of gpD (never previously observed), but there was no binding by the antibody to the gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 or -Ver3 fusion proteins (

i.e. to the bands shown slightly above the 25 kD marker in

Figure 7A, lanes 1 and 2). The immune response of young lambs to the gpD-BVDV-E2 Ver2 and Ver3 phage particles (

Figure 5, lanes 1 and 2) and to banded (not shown) λ

imm434cI#5 particles prepared in the absence of any gpD-fusion protein, is shown in

Figure S1, following either intradermal or intranasal administration. All the particle types were immunogenic.

Figure 7.

Comparison of phage particles coated with gpD and gpD< (epitopes from Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus -BVDV2 E2 protein [

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90] with phage particles obtained without exposure to gpD<.

A. Lane 1. Phage particles from band shown in

Figure 4 (tube 1): λ

imm434cI#5 infection of nonpermissive W3350 cells with plasmid expressing gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 = 1-110 gpD-GGSGAP(spacer)-[E2:47-88(EGKDLKILKTKRYLVAVHERALSTSAEFMQISDGTIAP)]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:111-121(KGKFNASLLNG)]-AAY(spacer)- 309-372(RDRYFQQYMLKGEWQYWFDLDSVDHHKDYFSEFIIIAVVALLGGKYVLLLLITYTILFG)].

Lane 2. Phage particles from band shown in

Figure 4 (tube 1): λ

imm434cI#5 infection of cells with plasmid expressing gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 = 1-110 gpD-GGSGAP(spacer)-[E2:47-78(EGKDLKILKTKRYLVAVHERALSTSAEF)]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:111-121(KGKFNASLLNG)]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:146-160(LDTTVVRTYRRTTPF]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:309-372(RDRYFQQYMLKGEWQYWFDLDSVDHHKDYFSEFIIIAVVALLGGKYVLLLLITYTILFG)].

Lanes 1, 2: Trace analysis (TotalLab software version 2.4 evaluation of UV Trans Illumination and ChemiDoc MP images of the Oriole stain) showed the density/volume of the gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 band (in lane 2) was at least 6.4-fold less than the gpD band in same lane, while the density of same band in lane 2 for the Ver2 display phage was >40 less.

Lane 3. BioRad marker set 10 kD-250kD.

B. Lane 4. Phage particles from CsCl band (not shown) derived from lysate produced after infection of nonpermissive W3350 cells with λ

imm434cI#5.

C. Western blot of the gel shown in A, corresponding to lanes 1 and 2, employing anti-His-gpD mouse antibody with chemiluminescence detection of secondary rabbit anti-mouse IgG (HRP conjugated).

D. Cell extracts from W3350 cells transformed with plasmid pcIpR-Dcoe-BVDV-E2-Ver2, were grown to mid log in shaking water bath at 30

oC then shifted to 42

oC to thermally induce the expression of the gpD-BVDV-E2-Ver2 gene fusion protein from pcIpR[GOI]-timm plasmid. Cell extracts from the induced cultures were pelleted, lysed with SDS, aliquots were run out by electrophoresis on denaturing acrylamide gel, and stained with Coomassie blue. The culture for “no plasmid” was collected after heat shift from 30

oC to 42

oC with culture shaking for 90 minutes.

Figure 7.

Comparison of phage particles coated with gpD and gpD< (epitopes from Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus -BVDV2 E2 protein [

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90] with phage particles obtained without exposure to gpD<.

A. Lane 1. Phage particles from band shown in

Figure 4 (tube 1): λ

imm434cI#5 infection of nonpermissive W3350 cells with plasmid expressing gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 = 1-110 gpD-GGSGAP(spacer)-[E2:47-88(EGKDLKILKTKRYLVAVHERALSTSAEFMQISDGTIAP)]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:111-121(KGKFNASLLNG)]-AAY(spacer)- 309-372(RDRYFQQYMLKGEWQYWFDLDSVDHHKDYFSEFIIIAVVALLGGKYVLLLLITYTILFG)].

Lane 2. Phage particles from band shown in

Figure 4 (tube 1): λ

imm434cI#5 infection of cells with plasmid expressing gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 = 1-110 gpD-GGSGAP(spacer)-[E2:47-78(EGKDLKILKTKRYLVAVHERALSTSAEF)]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:111-121(KGKFNASLLNG)]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:146-160(LDTTVVRTYRRTTPF]-AAY(spacer)-[E2:309-372(RDRYFQQYMLKGEWQYWFDLDSVDHHKDYFSEFIIIAVVALLGGKYVLLLLITYTILFG)].

Lanes 1, 2: Trace analysis (TotalLab software version 2.4 evaluation of UV Trans Illumination and ChemiDoc MP images of the Oriole stain) showed the density/volume of the gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver3 band (in lane 2) was at least 6.4-fold less than the gpD band in same lane, while the density of same band in lane 2 for the Ver2 display phage was >40 less.

Lane 3. BioRad marker set 10 kD-250kD.

B. Lane 4. Phage particles from CsCl band (not shown) derived from lysate produced after infection of nonpermissive W3350 cells with λ

imm434cI#5.

C. Western blot of the gel shown in A, corresponding to lanes 1 and 2, employing anti-His-gpD mouse antibody with chemiluminescence detection of secondary rabbit anti-mouse IgG (HRP conjugated).

D. Cell extracts from W3350 cells transformed with plasmid pcIpR-Dcoe-BVDV-E2-Ver2, were grown to mid log in shaking water bath at 30

oC then shifted to 42

oC to thermally induce the expression of the gpD-BVDV-E2-Ver2 gene fusion protein from pcIpR[GOI]-timm plasmid. Cell extracts from the induced cultures were pelleted, lysed with SDS, aliquots were run out by electrophoresis on denaturing acrylamide gel, and stained with Coomassie blue. The culture for “no plasmid” was collected after heat shift from 30

oC to 42

oC with culture shaking for 90 minutes.

Evaluating biological activity of antimicrobial polypeptides fused to gpD. In a previous study [

80] we examined whether antimicrobial polypeptides fused to gpD could exhibit biological activity. For this purpose, we fused antimicrobial peptides, including cathelicidins from human (LL37), pig (PR39), or human α- or β-defensins to gpD, and examined whether they retained antimicrobial activity conformation when fused to gpD. We found that fusion to the NH2- terminal end of gpD nullified antimicrobial activity for all of them, whereas the same fusions to the COOH-end of gpD each retained strong antimicrobial activity (

E. coli toxicity). The high toxicity of the fused α- defensin (HD5) and β-defensins (HβD3 and DEFβ126 [deleted for C-terminal 32 amino acid residues]) expressed in 594 host cells suggest that either a) these COOH-fused defensin undergo the correct formation of three possible intramolecular disulfide bonds after translation within the cytoplasm of wild type

E. coli cells that were not impaired for synthesis of either thiroredoxin or glutathione (

i.e., remained competent in

trxB and

gor genes), or b) that reduced versions of the gpD-linked defensins without disulfide bonds represent the highly toxigenic form of the antimicrobial peptides. There is evidence for the β-defensin HBD1 that only after the reduction of its disulfide-bridges does it become a potent antimicrobial [

91]. The relative toxicity of gpD-fused α-and β-defensins and cathelicidins expressed in wild type (594) and in

DsbC trxB (C3026H) cells where disulfide-bridges can form within the cytoplasm was compared,

Table 2. In cells (C3026H) where the gpD-fused HβD3 β-defensin and fused HD5 α-defensin could form disulfide-bridges, defensin toxicity was eliminated. This did not hold for the DEFβ126 β-defensin that had been deleted for 32 residues at COOH end. Presumable, without these additional 32 amino acids, correct folding to enable disulfide bond formation between any of its seven cysteins cannot occur. Strain C3026H had no influence on toxicity when either the pig or human cathlicidins were directly fused to the COOH end of gpD (both fusion combinations remained highly toxic), but it could suppress the toxicity of the complex cathelicidin LL37 fusion expressed from plasmid p619 (for which we have no explanation since the additions to gpD do not not contain cysteines). These data support the reported result for defensin HBD1, and suggest that the reduced versions of α- and β-defensins without disulfide bridges (but not the oxidized versions) are required for manifesting their antimicrobial activity.

DNA vaccines delivered in phage lambda particles (LDNAP). The advantages and disadvantages of DNA vaccines, regulatory hurdles and their use against viral diseases, bacterial pathogens, cancer and immunological responses are reviewed in [

92,

93,

94,

95]. The DNA vaccine is usually a plasmid DNA that encodes a disease specific antigen. The antigen gene is expressed from a broadly active eukaryotic promoter, often derived from the Herpes Cytomegalovirus (CMV). The antigen gene is cloned between the eukaryotic promoter and a eukaryotic termination/polyadenylation (PA) signal. A typical method for delivering a DNA vaccine involves using a gene gun [

96,

97,

98] containing gold particles with the DNA vaccine coated on them. Particles from the gun enter a target cell, where injected DNA enters the cell nucleus [

99] and then is transcribed. The mRNA is transported out of nucleus for translation and processing of the expressed protein antigen(s) encoded by the vaccine. The objective is to target antigen presenting cells, especially dendritic cells, that can present the antigenic peptides onto host cell MHC, evoking both cell mediated and humoral immune responses.

One key disadvantage to DNA vaccines,

e.g., compared to protein vaccines, is that the vaccine DNA is degraded by ubiquitous DNase when moved as a DNA reagent into a biological milieu. Phage particles encapsulating a DNA vaccine expression system provide an important improvement over naked DNA,

i.e., the DNA packed into the capsid particle (called a sheathed DNA vaccine) is protected from DNase, and particles about the size of phages like λ are readily phagocytized by dendritic cells, increasing the probability that an expressed antigenic gene product is processed by an animal’s innate immune system [

23,

24,

100].

March and coworkers were early pioneers in evaluating mammalian expression cassettes integrated within the lambda genome for the purpose of developing DNA vaccines [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105]. They were able to use whole λ particles as a DNA vaccine against Hepatitis B showing an immune response in vaccinated rabbits. In this work they linearized plasmid preCMV-HBsAg [Aldverson] and cloned it into a λgt11 DNA vector, generating phage particles for vaccination after λ

in vitro packaging of the cloned expression plasmid [

103]; similarly, they cloned other eukaryotic expression cassettes, as pcDNA3 or Stratagene plasmid pBK-CMV into the Stratagene cloning vector λZAP or again into λgt11.

These early attempts potentially suffered in two ways. First, all of the plasmid eukaryotic vectors incorporated into phage particles included antibiotic resistance genes that were moved, via DNA vaccine construction, into animal hosts. Gene transfer of antibiotic resistance into a eukaryotic host during vaccine administration seems undesirable. For example, Stratagene plasmid pBK-CMV encodes kanamycin/neomycin resistance and pcDNA3.1/myc-His(-)A (or B or C variants) encode both ampicillin resistance gene for selection in E. coli and neomycin resistance gene for selection in eukaryotic cells. Secondly, eukaryotic gene expression from the plasmids they employed was likely quite low (by a factor of greater than 20) compared to expression from the pCI-neo (Promega) cloning vector [Promega Notes Magazine 51:10(1995)].

With these limitations in mind, we chose to design plasmids with a powerful eukaryotic expression cassette, where only the expression cassette, without other plasmid components, was moved into a phage λ genome. For short, these phage particles with cloned eukaryotic expression cassettes were designated LDNAP. It was assumed the LDNAP phage could additionally be grown in cells expressing some gpD< fusion protein, enabling them to target ligands binding to “<” displayed from the phage. Such particles were termed L2DP (DNA-display particles).

Most of the poor eukaryotic expression plasmids included large multiple cloning sites (MCS, about 113 base pairs) and straddling bacteriophage T7 and T3 promoters (184 base pairs), with possibilities for hairpin structures that may limit gene expression. In a set of plasmids, loosely termed pSJH, focusing on pSJH-D’ herein (see Supplement:

Plasmid Construction Example (for Plasmid p578)), the MCS was reduced to 30 base pairs (

AseI-XhoI-NotI-ClaI) and the T7 and T3 were eliminated. The eukaryotic expression cassette was designed to be recombined or directly cloned (without any of the plasmid parts or selection genes), into a λ phage hybrid capable of strong plaque forming ability,

i.e., one retaining all the vector’s recombinational potential (Note: many lambda cloning vectors are highly deleted for nonessential genes and plaque poorly.) A comparison of the expression of eukaryotic genes EGFP and Luc2P from the pSJH plasmids to their expression from commercial plasmids is shown (

Table 3).

In providing that the pSJH vectors could enable substitutional gene exchange recombination (

Figure 8A),

i.e., replacing a dispensable portion of the λ genome with the eukaryotic expression cassette, copies of DNA from λ genome were introduced into the plasmids straddling the eukaryotic expression cassette. These included segments representing λ bases 18968-19328 and 23937-24310, color coded as purple and orange regions, respectively (

Figure 8). Their presence in possible vector phage to make LDNAP was examined by PCR (

Figure 8B). Surprisingly, only four of the nine potential vector phages carried both regions, and did not include the λ

imm434cI#5 phage that we had used extensively in developing LDP (

Figure 5’s and

Figure 7). An example showing recombinational uptake of a pSJH plasmid eukaryotic expression cassette straddled by the purple and orange DNA homologies into LDNAP vector is shown (

Figure 9A), where the LDNAP phage plaques incorporating the eukaryotic expression cassette for EGFP can be detected by hybridization by all of the purified LDNAP plaques (

Figure 9B). A diagram of the cloning sites A and B for moving a eukaryotic expression cassette from one of the plasmids into a vector phage containing purple and orange homologies into a vector phage to make an LDNAP is shown (

Figure 10). Versions of the pSJH plasmids include GFP gene (replacing antibiotic resistance as a selectable marker and placed under control of the lambda

pR promoter) within the eukaryotic expression cassette, that is to be moved into a λ vector. This figure shows that λ gene

lom is substituted (either by recombination or cloning) when the cassette is moved into a λ. LDNAP vectors made from essentially wild type λ phage will tolerate ~6044bp (12.5%λ) substitutions. As noted, these LDNAP vector recombinants can be modified to make L2DP,

i.e. display-coated LDNAP for targeting cell receptors.

Progress and remaining work to exploit LDNAP as vaccine agents. Several recent reviews have examined the potential utility of using phage particles as vaccine delivery vehicles [

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114] and the cellular immune responses. We previously demonstrated a) that LDP displaying fused gpD-CAP epitopes [

75] of the Porcine Circovirus 2 (PCV2) produced both neutralizing IgG antibody (in an

in vitro assay) and a T-cell mediated cellular immune response to intradermal vaccination [

76]; b) that LDP displaying gpD-pRp disease specific prion protein epitopes patterned to combat chronic wasting disease in cervids and formulated as a mucosal vaccine was taken up in Peyer’s patches and the draining mesenteric lymph nodes in claves, and resulted in both mucosal IgA and IgG immune responses [

74]; and c) we show herein (

Figure S1) that LDP representing phage particles shown in

Figure 5 gradients 1 and 2 and displaying disease specific epitopes (gpD-BVDV2-E2-Ver2 and gp-BVDV2-E2-Ver3) of the capsid protein for Bovine Viral Diarrheal Virus 2 were immunogenic when administered either nasally or intradermally. In short, in each of the three vaccination assays the LDP proved immunogenic, but very much work is required to assess whether this vaccination strategy, which does not require adjuvant, stimulates a protective immune response.

Much further work is needed to prepare and evaluate sheathed DNA vaccines using the LDNAP cloning or recombination technology described herein in order to update the original studies pursued by March and collaborators. Many problems with this technology require solution, each are linked to being able to follow the fate and immune responses of LDNAP administered to and expressed within dendritic cells. Importantly, learning if protective immune responses are evoked in vaccinated animals.

Use of LDP as antimicrobials to antimicrobial resistant bacteria, or a nontargeted version of phage therapy? We have shown that human and porcine cathelicidins LL37 and PR39 linked to the COOH-terminal end of gpD are highly toxic when expressed within E. coli, and similar results were observed for reduced versions of selected human α- and β-defensins. Coated phage particles comprising LDP with gpD-fused cathelicidins or defensins are generated simply by infecting cells capable of expressing a gpD-fusion protein below the lethal expression temperatures, i.e. below 41-42oC. Alternatively, LDP can arise in expression cells where the gpD-fusion is only toxigenic when administered to the outer surface of cells. We have found that D-defective λ phage are complemented efficiently (50-90+%, not shown) at infection temperatures of 37-39oC by cultures of all the toxigenic gpD-fusions with cathelicidins and defensins. Clearly, the cathelicidins and defensins evaluated retained biological activity when fused at the COOH end of gpD. LDP lysates produced via using a D-defective infecting phage can be employed to generate LDP coated with pathogen-sensitive gpD-fusions. Preparation of antimicrobial agents made from LDP will require screening for display peptides that exhibit external cellular toxicity. In such a display system, none of the produced LDP would encode the toxic gpD-fusion gene, nullifying horizontal gene transfer.

Summary. We show how it is easily possible to produce fully coated LDP, or to produce partially coated LDP without any complex bacteriophage genetic engineering, making the system available to all. We show that multiple, single epitope LDP vaccine reagents can be generated in a single infection lysate. We provide a system whereby either intracellular phage-plasmid substitution recombination, or by cloning can generate sheathed DNA vaccine particles, termed LDNAP that have the advantage of high-level eukaryotic expression cassette without incorporating plasmid resistance elements or other genes. We note that the LDNAP phage can be propagated in bacterial cells expressing a gpD-fusion protein, forming L2DP vaccine particles that could target ligands on antigen presenting cells, increasing the specificity of the sheathed DNA vaccine particle.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr. Karthic Rajamanickam for constructing plasmids p674- p676 and Connie Hayes for constructing the remaining plasmids shown in Table S1 and Plasmid Construction Example. Funding for the studies described in Figure S1 was received from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grand Challenges) by Drs. vanDen Hurk and Hayes, University of Saskatchewan. Other funding was mainly from NSERC Canada Discovery grants awarded to Sidney Hayes between about 2000-2018 and 2020-21 sabbatical funding from University of Saskatchewan.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Brussow, H. and R.W. Hendrix, Phage genomics: Small is beautiful. Cell, 2002. 108(1): p. 13-16. [CrossRef]

- Brussow, H., C. Canchaya, and W.D. Hardt, Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 2004. 68(3): p. 560-602, table of contents. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, P.L. and M.K. Waldor, Bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence. Infect Immun, 2002. 70(8): p. 3985-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broudy, T.B. and V.A. Fischetti, In vivo lysogenic conversion of Tox(-) Streptococcus pyogenes to Tox(+) with Lysogenic Streptococci or free phage. Infect Immun, 2003. 71(7): p. 3782-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harhala, M., et al., Two novel temperate bacteriophages infecting Streptococcus pyogenes: Their genomes, morphology and stability. PLoS One, 2018. 13(10): p. e0205995. [CrossRef]

- McShan, W.M., K.A. McCullor, and S.V. Nguyen, The Bacteriophages of Streptococcus pyogenes. Microbiol Spectr, 2019. 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, I., et al., Genome sequence of an M3 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes reveals a large-scale genomic rearrangement in invasive strains and new insights into phage evolution. Genome Res, 2003. 13(6A): p. 1042-55. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.V. and W.M. McShan, Chromosomal islands of Streptococcus pyogenes and related streptococci: molecular switches for survival and virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2014. 4: p. 109. [CrossRef]

- Alisky, J., et al., Bacteriophages show promise as antimicrobial agents. J Infect, 1998. 36(1): p. 5-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, B., et al., Bacteriophage therapy rescues mice bacteremic from a clinical isolate of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun, 2002. 70(1): p. 204-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlton, R.M., Phage therapy: past history and future prospects. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz), 1999. 47(5): p. 267-74.

- Stone, R., Bacteriophage therapy. Stalin's forgotten cure. Science, 2002. 298(5594): p. 728-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulakvelidze, A., Z. Alavidze, and J.G. Morris, Jr., Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2001. 45(3): p. 649-59. [CrossRef]

- Summers, W.C., ed. Felix d'Herelle and the Orgins of Molecular Biology. 1999, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. 47-59.

- Merril, C.R., D. Scholl, and S.L. Adhya, The prospect for bacteriophage therapy in Western medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2003. 2(6): p. 489-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabrowska, K., Phage therapy: What factors shape phage pharmacokinetics and bioavailability? Systematic and critical review. Med Res Rev, 2019. 39(5): p. 2000-2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabrowska, K., et al., Bacteriophage penetration in vertebrates. J Appl Microbiol, 2005. 98(1): p. 7-13.

- Summers, W.C., Bacteriophage therapy. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2001. 55: p. 437-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djebara, S., et al., Processing Phage Therapy Requests in a Brussels Military Hospital: Lessons Identified. Viruses, 2019. 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Regeimbal, J.M., et al., Personalized Therapeutic Cocktail of Wild Environmental Phages Rescues Mice from Acinetobacter baumannii Wound Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2016. 60(10): p. 5806-16. [CrossRef]

- Schooley, R.T., et al., Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails To Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017. 61(10). [CrossRef]

- Young, M.J., et al., Phage Therapy for Diabetic Foot Infection: A Case Series. Clin Ther, 2023. 45(8): p. 797-801. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.R. and J.B. March, Bacteriophages and biotechnology: vaccines, gene therapy and antibacterials. Trends Biotechnol, 2006. 24(5): p. 212-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.R. and J.B. March, Bacterial viruses as human vaccines? Expert Rev Vaccines, 2004. 3(4): p. 463-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier, M.R., M.E. Trigg, and C.R. Merril, Fate of bacteriophage lambda in non-immune germ-free mice. Nature, 1973. 246(5430): p. 221-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchley, C.J., The actvity of mouse Kupffer cells following intravenous injection of T4 bacteriophage. Clin Exp Immunol, 1969. 5(1): p. 173-87.

- Keller, R. and F.B. Engley, Jr., Fate of bacteriophage particles introduced into mice by various routes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med, 1958. 98(3): p. 577-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchley, C.J. and J.G. Howard, The immunogenicity of phagocytosed T4 bacteriophage: cell replacement studies with splenectomized and irradiated mice. Clin Exp Immunol, 1969. 5(1): p. 189-98.

- Merril, C.R., et al., Long-circulating bacteriophage as antibacterial agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1996. 93(8): p. 3188-92.

- Nungester, W.J., and Watrous, R.M., Accumulation of bacteriophage in spleen and liver following itws intravenous inoculation. Proceedings of The Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 1934: p. 31910-31905.

- Reynaud, A., et al., Characteristics and diffusion in the rabbit of a phage for Escherichia coli 0103. Attempts to use this phage for therapy. Vet Microbiol, 1992. 30(2-3): p. 203-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinstry, M., and Edgar, R., ed. Phages, their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotchnology. ed. M.K. Walder, Friedman, D. I., Adhya, S. L. 2005, ASM Press: Washington, DC.

- Gupta, A., Oppenheim, A. B., and Chaudhary, V. K., Phage display: a molecular fashion show., in Phages. Their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotechnology., M.K. Walder, Friedman, D. I., Adhya, S. L. , Editor. 2005, ASM Press: Washington, D.C. p. 415-429.

- Ebrahimizadeh, W. and M. Rajabibazl, Bacteriophage vehicles for phage display: biology, mechanism, and application. Curr Microbiol, 2014. 69(2): p. 109-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.P., Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science, 1985. 228(4705): p. 1315-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q., et al., Bacteriophage T4 capsid: a unique platform for efficient surface assembly of macromolecular complexes. J Mol Biol, 2006. 363(2): p. 577-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.J., et al., Phage display of intact domains at high copy number: a system based on SOC, the small outer capsid protein of bacteriophage T4. Protein Sci, 1996. 5(9): p. 1833-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.J., et al., Orally delivered foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid protomer vaccine displayed on T4 bacteriophage surface: 100% protection from potency challenge in mice. Vaccine, 2008. 26(11): p. 1471-81.

- Shivachandra, S.B., et al., In vitro binding of anthrax protective antigen on bacteriophage T4 capsid surface through Hoc-capsid interactions: a strategy for efficient display of large full-length proteins. Virology, 2006. 345(1): p. 190-8. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., et al., Bacteriophage T4 nanoparticle capsid surface SOC and HOC bipartite display with enhanced classical swine fever virus immunogenicity: a powerful immunological approach. J Virol Methods, 2007. 139(1): p. 50-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X., et al., Advances in the T7 phage display system (Review). Mol Med Rep, 2018. 17(1): p. 714-720. [CrossRef]

- Benhar, I., Biotechnological applications of phage and cell display. Biotechnol Adv, 2001. 19(1): p. 1-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.F. and M. Yu, Epitope identification and discovery using phage display libraries: applications in vaccine development and diagnostics. Curr Drug Targets, 2004. 5(1): p. 1-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willats, W.G., Phage display: practicalities and prospects. Plant Mol Biol, 2002. 50(6): p. 837-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambkin, I. and C. Pinilla, Targeting approaches to oral drug delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2002. 2(1): p. 67-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feiss, M., Becker, A., DNA packaging and cutting., in Lambda II, R.W. Hendrix, Roberts, J.W., Stahl, F.W., and Weisberg, R.A., Editor. 1983, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY. p. 305-330.

- Georgopoulos, C., Tilly, K., and Casjens, S., Lambdoid phage head assembly, in Lambda II, J.W.R. R.W. Hendrix, F.S. Stahl, R.A. Weisberg, Editor. 1983, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Cold Spring Harbor, NY. p. 279-304.

- Katsura, I., Structure and function of the major tail protein of bacteriophage lambda. Mutants having small major tail protein molecules in their virion. J Mol Biol, 1981. 146(4): p. 493-512. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, G.C., et al., Bacteriophage lambda stabilization by auxiliary protein gpD: timing, location, and mechanism of attachment determined by cryo-EM. Structure, 2008. 16(9): p. 1399-406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, N. and R. Weisberg, Packaging of coliphage lambda DNA. I. The role of the cohesive end site and the gene A protein. J Mol Biol, 1977. 117(3): p. 717-31.

- Sternberg, N. and R. Weisberg, Packaging of coliphage lambda DNA. II. The role of the gene D protein. J Mol Biol, 1977. 117(3): p. 733-59.

- Yang, F., et al., Novel fold and capsid-binding properties of the lambda-phage display platform protein gpD. Nat Struct Biol, 2000. 7(3): p. 230-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, I.S., Assembly of functional bacteriophage lambda virions incorporating C-terminal peptide or protein fusions with the major tail protein. J Mol Biol, 1995. 248(3): p. 497-506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavoni, E., et al., Simultaneous display of two large proteins on the head and tail of bacteriophage lambda. BMC Biotechnol, 2013. 13: p. 79. [CrossRef]

- Ansuini, H., et al., Biotin-tagged cDNA expression libraries displayed on lambda phage: a new tool for the selection of natural protein ligands. Nucleic Acids Res, 2002. 30(15): p. e78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchini, C., et al., Searching for DNA-protein interactions by lambda phage display. J Mol Biol, 2002. 322(4): p. 697-706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, R., et al., Selection of biologically active peptides by phage display of random peptide libraries. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 1996. 7(6): p. 616-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, M., et al., Affinity selection of cDNA libraries by lambda phage surface display. Gene, 2000. 256(1-2): p. 229-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santi, E., et al., Bacteriophage lambda display of complex cDNA libraries: a new approach to functional genomics. J Mol Biol, 2000. 296(2): p. 497-508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, C., et al., Efficient display of an HCV cDNA expression library as C-terminal fusion to the capsid protein D of bacteriophage lambda. J Mol Biol, 1998. 282(1): p. 125-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucconi, A., et al., Selection of ligands by panning of domain libraries displayed on phage lambda reveals new potential partners of synaptojanin 1. J Mol Biol, 2001. 307(5): p. 1329-39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, N. and R.H. Hoess, Display of peptides and proteins on the surface of bacteriophage lambda. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995. 92(5): p. 1609-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikawa, Y.G., I.N. Maruyama, and S. Brenner, Surface display of proteins on bacteriophage lambda heads. J Mol Biol, 1996. 262(1): p. 21-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilchez, S., J. Jacoby, and D.J. Ellar, Display of biologically functional insecticidal toxin on the surface of lambda phage. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2004. 70(11): p. 6587-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, B. and W.J. Ma, Display of aggregation-prone ligand binding domain of human PPAR gamma on surface of bacteriophage lambda. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2006. 27(1): p. 91-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beghetto, E. and N. Gargano, Lambda-display: a powerful tool for antigen discovery. Molecules, 2011. 16(4): p. 3089-105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A., et al., High-density functional display of proteins on bacteriophage lambda. J Mol Biol, 2003. 334(2): p. 241-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, V.K., Gupta, A., Adhya, S., and Pastan, I., Novel lambda phage display system and the process. 2003.

- Minenkova, O., et al., Identification of tumor-associated antigens by screening phage-displayed human cDNA libraries with sera from tumor patients. Int J Cancer, 2003. 106(4): p. 534-44. [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, E., et al., Identification of a panel of tumor-associated antigens from breast carcinoma cell lines, solid tumors and testis cDNA libraries displayed on lambda phage. BMC Cancer, 2004. 4: p. 78. [CrossRef]

- Zanghi, C.N., et al., A simple method for displaying recalcitrant proteins on the surface of bacteriophage lambda. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005. 33(18): p. e160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanghi, C.N., et al., A tractable method for simultaneous modifications to the head and tail of bacteriophage lambda and its application to enhancing phage-mediated gene delivery. Nucleic Acids Res, 2007. 35(8): p. e59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X., Heat induced capsid disassembly and DNA release of bacteriophage lambda. PLoS One, 2012. 7(7): p. e39793. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cano, P., et al., Lambda display phage as a mucosal vaccine delivery vehicle for peptide antigens. Vaccine, 2017. 35(52): p. 7256-7263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S., L.N. Gamage, and C. Hayes, Dual expression system for assembling phage lambda display particle (LDP) vaccine to porcine Circovirus 2 (PCV2). Vaccine, 2010. 28(41): p. 6789-99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamage, L.N., J. Ellis, and S. Hayes, Immunogenicity of bacteriophage lambda particles displaying porcine Circovirus 2 (PCV2) capsid protein epitopes. Vaccine, 2009. 27(47): p. 6595-604. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S., et al., Phage Lambda P Protein: Trans-Activation, Inhibition Phenotypes and their Suppression. Viruses, 2013. 5(2): p. 619-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S., K. Rajamanickam, and C. Hayes, Complementation Studies of Bacteriophage lambda O Amber Mutants by Allelic Forms of O Expressed from Plasmid, and O-P Interaction Phenotypes. Antibiotics (Basel), 2018. 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, K. and S. Hayes, The Bacteriophage Lambda CII Phenotypes for Complementation, Cellular Toxicity and Replication Inhibition Are Suppressed in cII-oop Constructs Expressing the Small RNA OOP. Viruses, 2018. 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S., Bacterial Virus Lambda Gpd-Fusions to Cathelicidins, alpha- and beta-Defensins, and Disease-Specific Epitopes Evaluated for Antimicrobial Toxicity and Ability to Support Phage Display. Viruses, 2019. 11(9). [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y., et al., Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. J Virol, 2020. 94(7). [CrossRef]

- Sonnenborn, U., Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917-from bench to bedside and back: history of a special Escherichia coli strain with probiotic properties. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2016. 363(19). [CrossRef]

- Casjens, S.R. and R.W. Hendrix, Locations and amounts of major structural proteins in bacteriophage lambda. J Mol Biol, 1974. 88(2): p. 535-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, R.W. and R.L. Duda, Bacteriophage lambda PaPa: not the mother of all lambda phages. Science, 1992. 258(5085): p. 1145-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branza-Nichita, N., et al., Antiviral effect of N-butyldeoxynojirimycin against bovine viral diarrhea virus correlates with misfolding of E2 envelope proteins and impairment of their association into E1-E2 heterodimers. J Virol, 2001. 75(8): p. 3527-36. [CrossRef]

- Deregt, D., et al., Mapping of a type 1-specific and a type-common epitope on the E2 (gp53) protein of bovine viral diarrhea virus with neutralization escape mutants. Virus Res, 1998. 53(1): p. 81-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deregt, D., et al., Monoclonal antibodies to the E2 protein of a new genotype (type 2) of bovine viral diarrhea virus define three antigenic domains involved in neutralization. Virus Res, 1998. 57(2): p. 171-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, W., et al., The surface glycoprotein E2 of bovine viral diarrhoea virus contains an intracellular localization signal. J Gen Virol, 2004. 85(Pt 5): p. 1101-1111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paton, D.J., J.P. Lowings, and A.D. Barrett, Epitope mapping of the gp53 envelope protein of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Virology, 1992. 190(2): p. 763-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gennip, H.G.P., et al., Functionality of Chimeric E2 Glycoproteins of BVDV and CSFV in Virus Replication. Virology: Research and Treatment, 2008. 1: p. VRT.S589. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, B.O., et al., Reduction of disulphide bonds unmasks potent antimicrobial activity of human beta-defensin 1. Nature, 2011. 469(7330): p. 419-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.H., DNA vaccines: roles against diseases. Germs, 2013. 3(1): p. 26-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

PCV2 vaccines. Available from: http://cvmweb2.cvm.iastate.edu/departments/vdpam/swine/diseases/pcv2/associated_diseases/control/vaccines.asp.

- Donnelly, J., K. Berry, and J.B. Ulmer, Technical and regulatory hurdles for DNA vaccines. Int J Parasitol, 2003. 33(5-6): p. 457-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajcani, J., Mosko, T., and Rezuchova, Current developments in viral DNA vaccines: shall they solve the unsolved? Reviews in Midical Virology 2005, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.H., et al., Gene gun-based nucleic acid immunization alone or in combination with recombinant vaccinia vectors suppresses virus burden in rhesus macaques challenged with a heterologous SIV. Immunol Cell Biol, 1997. 75(4): p. 389-96. [CrossRef]

- Han, R., et al., Gene gun-mediated intracutaneous vaccination with papillomavirus E7 gene delays cancer development of papillomavirus-induced skin papillomas on rabbits. Cancer Detect Prev, 2002. 26(6): p. 458-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prayaga, S.K., M.J. Ford, and J.R. Haynes, Manipulation of HIV-1 gp120-specific immune responses elicited via gene gun-based DNA immunization. Vaccine, 1997. 15(12-13): p. 1349-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, H., et al., Kinetics and mechanism of DNA uptake into the cell nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2001. 98(13): p. 7247-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepson, C.D. and J.B. March, Bacteriophage lambda is a highly stable DNA vaccine delivery vehicle. Vaccine, 2004. 22(19): p. 2413-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.R. and J.B. March, Bacteriophage-mediated nucleic acid immunisation. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol, 2004. 40(1): p. 21-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, J.B., Bacteriophage-mediated immunization. 2002.

- March, J.B., J.R. Clark, and C.D. Jepson, Genetic immunisation against hepatitis B using whole bacteriophage lambda particles. Vaccine, 2004. 22(13-14): p. 1666-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, J.B., et al., Phage library screening for the rapid identification and in vivo testing of candidate genes for a DNA vaccine against Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small colony biotype. Infect Immun, 2006. 74(1): p. 167-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, R.M., Jepson, C.D., Clark, J.R., March, J.B., and cKeever, D.J. , Efferent lymphatic cannulation of DNA vaccines. Immunology, 2003. 110: p. 120.

- Hayes, S., et al., NinR- and red-mediated phage-prophage marker rescue recombination in Escherichia coli: recovery of a nonhomologous immlambda DNA segment by infecting lambdaimm434 phages. Genetics, 2005. 170(4): p. 1485-99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghebati-Maleki, L., et al., Phage display as a promising approach for vaccine development. J Biomed Sci, 2016. 23(1): p. 66. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mora, A., et al., Bacteriophage-Based Vaccines: A Potent Approach for Antigen Delivery. Vaccines (Basel), 2020. 8(3). [CrossRef]

- Hodyra-Stefaniak, K., et al., Mammalian Host-Versus-Phage immune response determines phage fate in vivo. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 14802. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, N., and Abediankenari, S., Phage particles as vaccine delivery vehicles: concepts, applications and prospects. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M., et al., Bacteriophages and the Immune System. Annu Rev Virol, 2021. 8(1): p. 415-435. [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem, J.D., et al., Interactions between Bacteriophage, Bacteria, and the Mammalian Immune System. Viruses, 2018. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Sweere, J.M., et al., Bacteriophage trigger antiviral immunity and prevent clearance of bacterial infection. Science, 2019. 363(6434). [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, U., et al., Phage display: a molecular tool for the generation of antibodies--a review. Placenta, 2000. 21 Suppl A: p. S106-12. [CrossRef]

- Zeghouf, M., et al., Sequential Peptide Affinity (SPA) system for the identification of mammalian and bacterial protein complexes. J Proteome Res, 2004. 3(3): p. 463-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).