Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structure and Microstructure

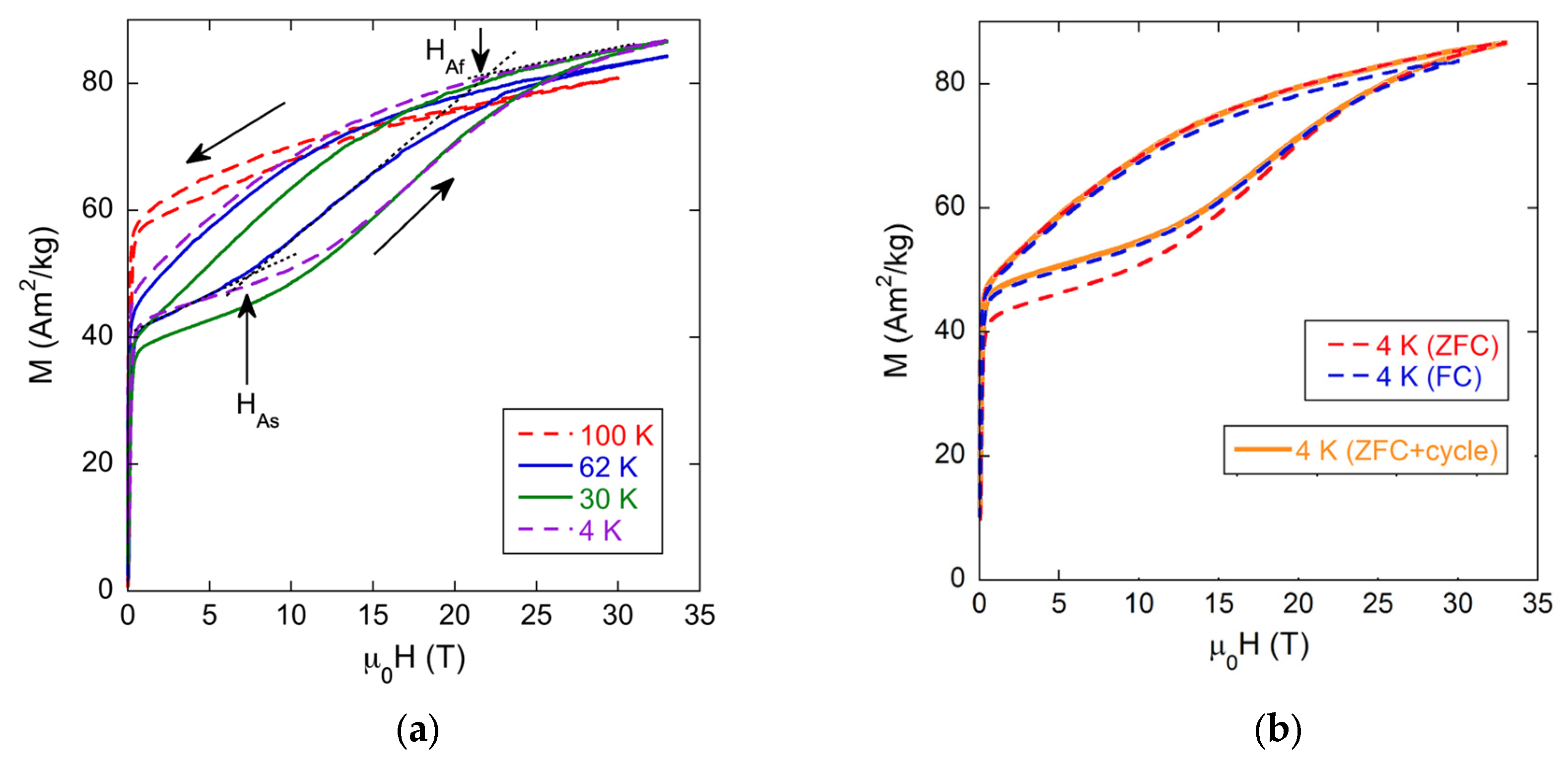

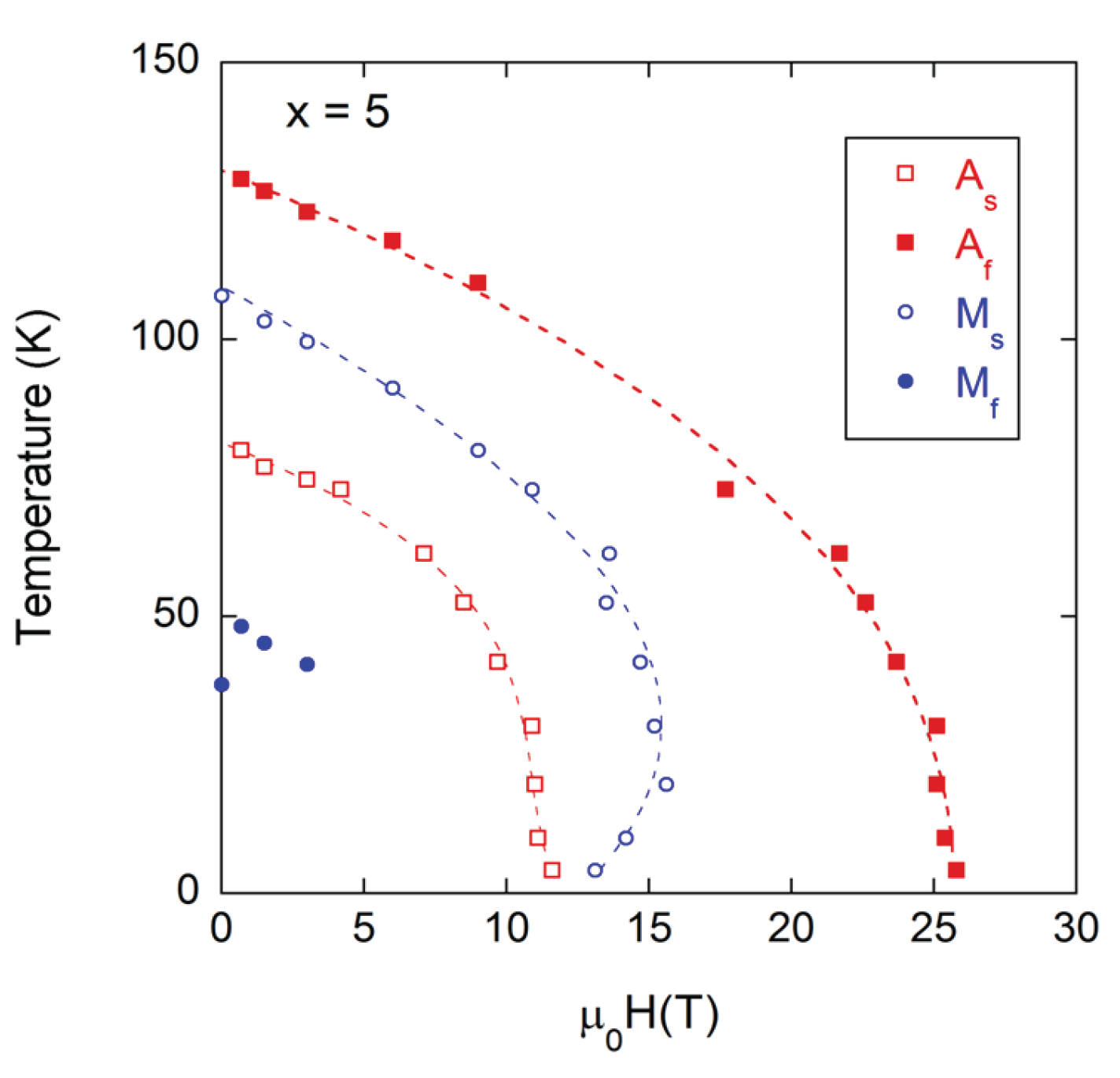

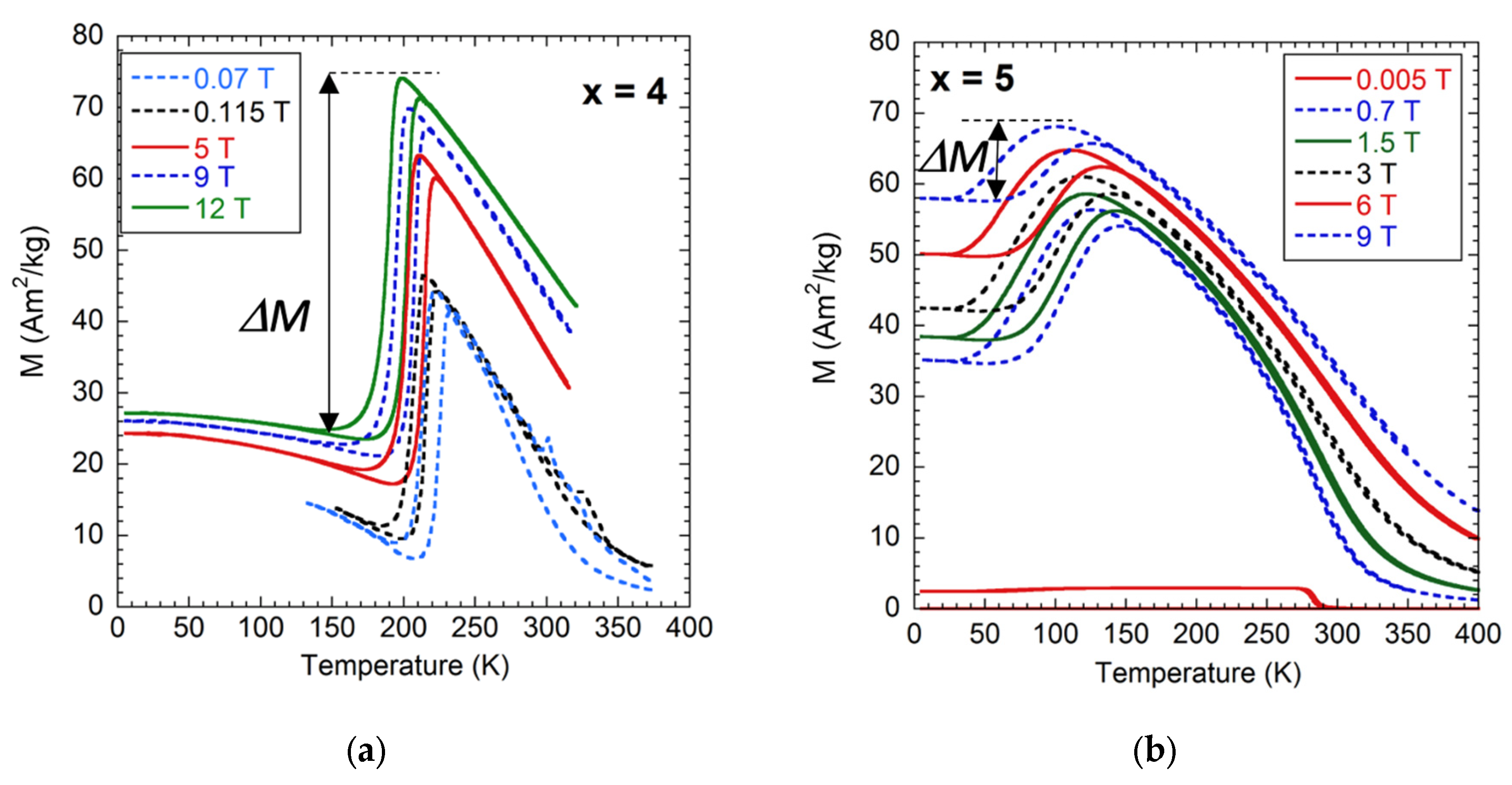

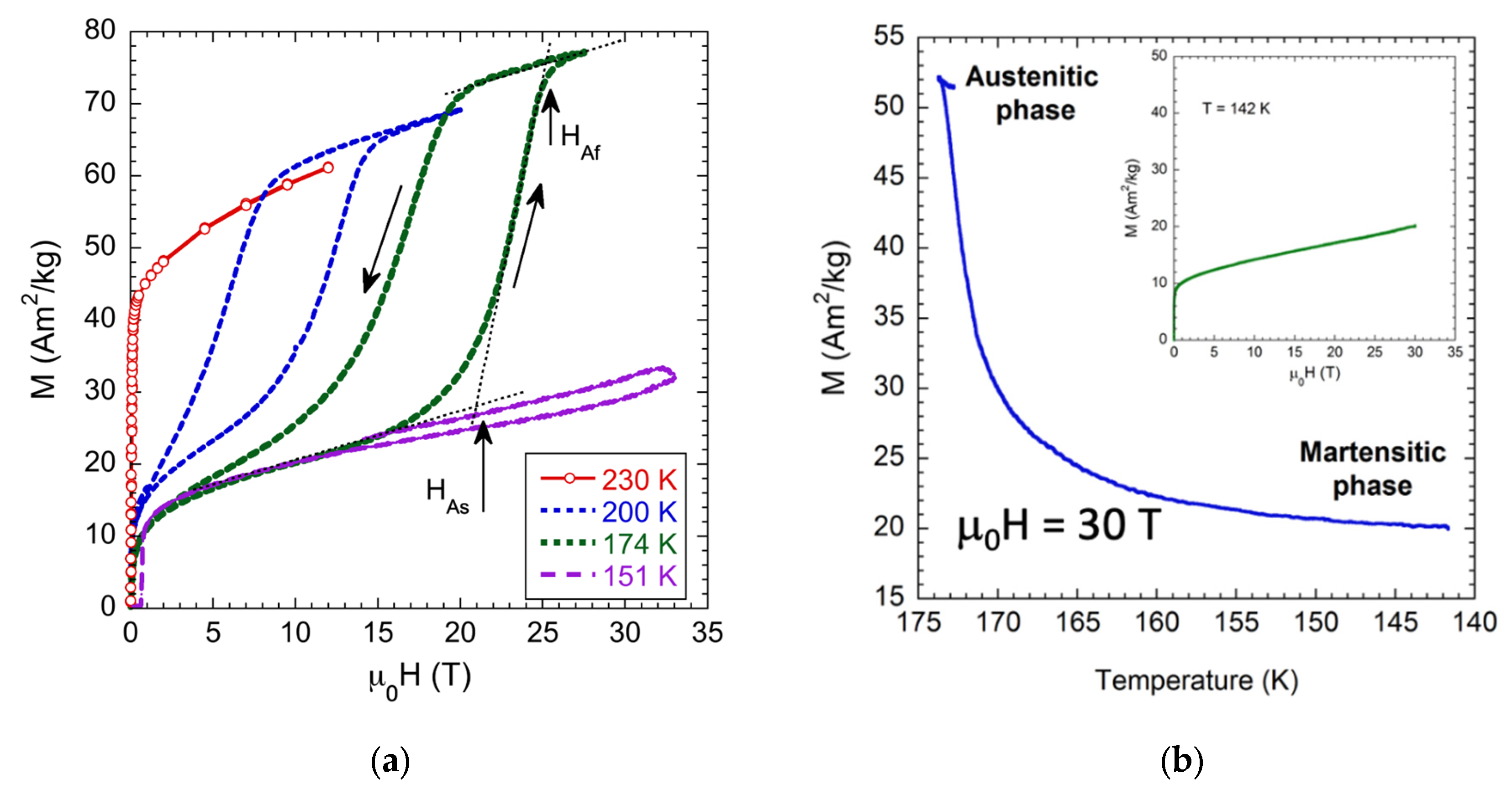

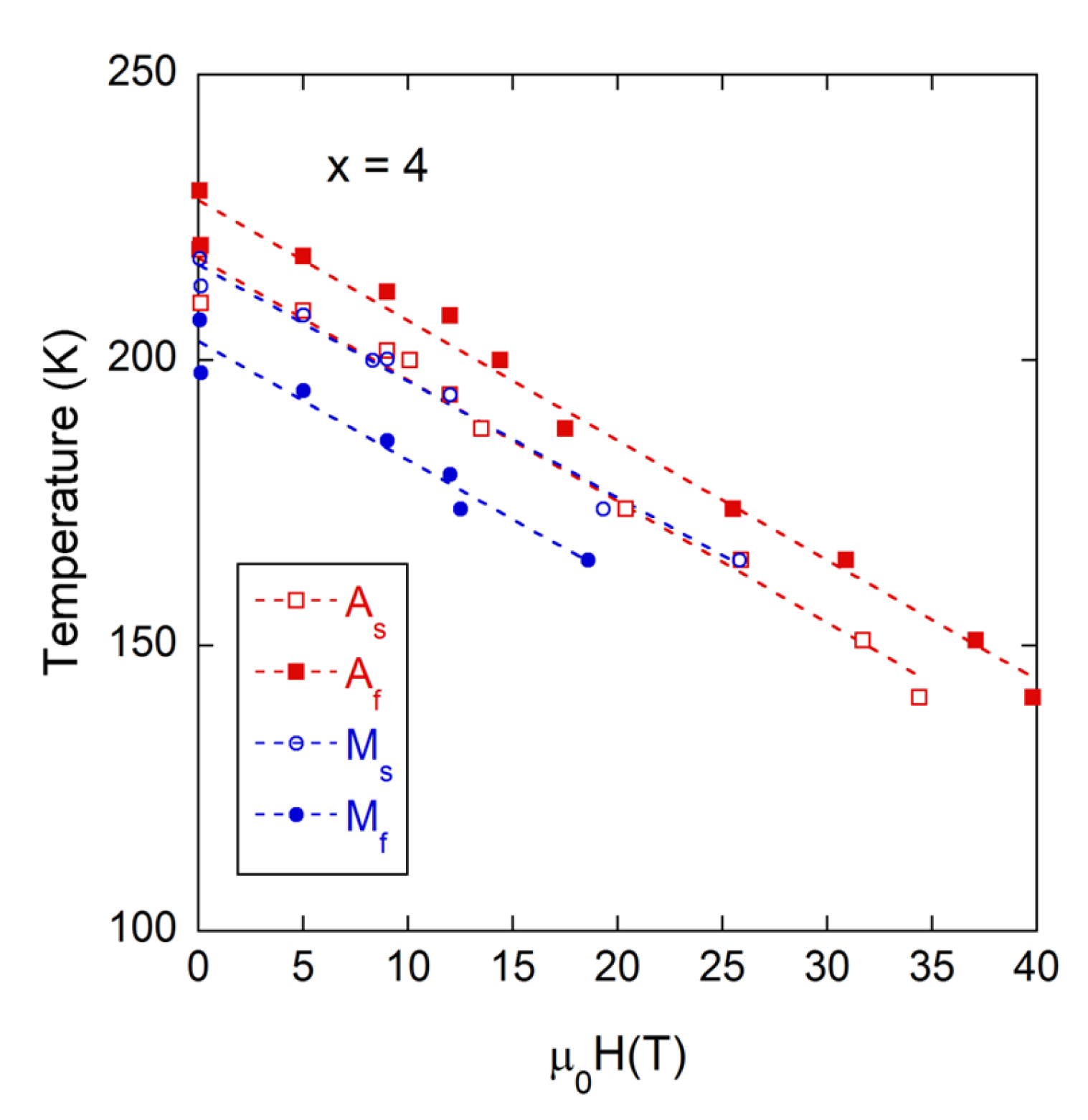

3.2. Magnetic Field Influence on the Martensitic Transformation and Kinetic Arrest

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMSMA | Heusler metamagnetic shape memory alloy |

| MT | Martensitic transformation |

| MMSM | Metamagnetic shape memory effect |

| MCE | Magnetocaloric effect |

| MFIMT | Magnetic field induced transformation |

| ZFC | Zero Field Cooling |

| H/SFC | High/Super Field Cooling |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| VSM | Vibrating Sample Magnetometry/Magnetometer |

References

- Kainuma, R.; Imano, Y.; Ito W; Sutou Y. ; Morito H.; Okamoto S.; Kitakami O.; Oikawa K.; Fujita A.; Kanomata T.; Ishida K. Magnetic-field-induced shape recovery by reverse phase transformation. Nature 2006, 439, 957–960; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.Y.; Cao, Z.X.; Ma, L.; Liu, G.D.; Chen, J.L.; Wu, G.H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.X. Realization of magnetic field-induced reversible martensitic transformation in NiCoMnGa alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 102507; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenke, T.; Duman, E.; Acet, M.; Wassermann, E.F.; Moya, X.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A. Inverse magnetocaloric effect in ferromagnetic Ni-Mn-Sn alloys. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 450–454; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Villa, P.O.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A.; Soto-Parra, D.E.; Sánchez-Llamazares, J.L.; Flores-Zúñiga, H.; Frontera, C. Elastocaloric and magnetocaloric effects in Ni-Mn-Sn(Cu) shape-memory alloy. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 53506, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainuma, R.; Oikawa, K.; Ito, W.; Sutou, Y.; Kanomata, T.; Ishida, K. Metamagnetic shape memory effect in NiMn-based Heusler-type alloys. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 1837; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Ito, W.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Tajima, S.; Kawaura, H.; Kainuma, R.; Ishida, K. Metamagnetic shape memory effect in polycrystalline NiCoMnSn alloy fabricated by spark plasma sintering. Scripta Mater. 2009, 61, 504–507; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkovaara, J.; Heczko, O.; Ayuela, A.; Nieminen, R.M. Coexistence of ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic order in Mn-doped Ni2MnGa. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 63, 212405; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.L.; Feuchtwanger, J.; Allen, S.M.; O'Handley, R.C.; Lazpita, P.; Barandiarán, J.M.; Gutiérrez, J.; Ouladdiaf, B.; Mondelli, C.; Lograsso, T.A.; Schlagel, D.L. Chemical order in off-stoichiometric Ni-Mn-Ga ferromagnetic shape-memory alloys studied with neutron diffraction. Philos. Mag. A 2007, 87, 3437–3447; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuang, H.C.; Ma, S.C.; Cao, Q.Q.; Wang, D.H.; Du, Y.W. Martensitic transformation and magnetic properties in high-Mn content Mn50Ni50-xInx ferromagnetic shape memory alloys. J. Alloy Comp. 2011, 509, 5761–5764; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G. Metamagnetic phase transformation in Mn50Ni37In10Co3 polycrystalline alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 61904; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázpita, P.; Sasmaz, M.; Barandiarán, J.M.; Chernenko, V.A. Effect of Fe doping and magnetic field on martensitic transformation of Mn-Ni(Fe)-Sn metamagnetic shape memory alloys. Acta Materialia 2018, 155, 95–103; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Woodward, R.C. Metallurgical origin of the effect of Fe doping on the martensitic and magnetic transformation behaviours of Ni50Mn40-xSn10Fex magnetic shape memory alloys. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 445–452; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Tai, Z.; Zhang, K.; Tian, X.; Cai, W. Simultaneous enhancement of magnetic and mechanical properties in Ni-Mn-Sn alloy by Fe doping, Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2–10; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, W.; Ito, K.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Kainuma, R.; Koyama, K.; Watanabe, K.; Fujita, A.; Oikawa, K.; Ishida, K.; Kanomata, T. Kinetic arrest of martensitic transformation in the NiCoMnIn metamagnetic shape memory alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 021908; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ito, W.; Tokunaga, M.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Kainuma, R.; Ishida, K. Kinetic arrest of martensitic transformation in NiCoMnAl metamagnetic shape memory alloy. Mater. Trans. 2010, 51, 1357–1360; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetsu, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Ito, W.; Kihara, T.; Takahashi, K.; Tokunaga, M.; Kainuma, R. Magnetic field-induced reverse martensitic transformation and thermal transformation arrest phenomenon of Ni41Co9Mn39Sb11 alloy. Metals 2014, 4, 609–622; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázpita, P.; Pérez-Checa, A. .; Barandiarán J.M.; Ammerlan A.; Zeitler U.; Chernenko V.A. Suppression of martensitic transformation in Ni-Mn-In metamagnetic shape memory alloy under very strong magnetic field. Journal of alloys and Compounds 2021, 874, 159814 (6 pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Landazábal, J.I.; Recarte, V.; Sánchez-Alarcos, V.; Gómez-Polo, C.; Kustov, S.; Cesari, E. Magnetic field induced martensitic transformation linked to the arrested austenite in a Ni-Mn-In-Co shape memory alloy. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 093515; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ortiz, C.O.; Soto-Parra, D.E.; Alvarez-Alonso, P.; Lázpita, P.; Salazar, D.; Castillo-Villa, P.O.; Flores-Zúñiga, H.; Chernenko, V.A. Influence of Fe doping and magnetic field on martensitic transition in Ni-Mn-Sn melt-spun ribbons. Acta Mater. 2016, 107, 9–16; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).