Submitted:

21 July 2023

Posted:

25 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

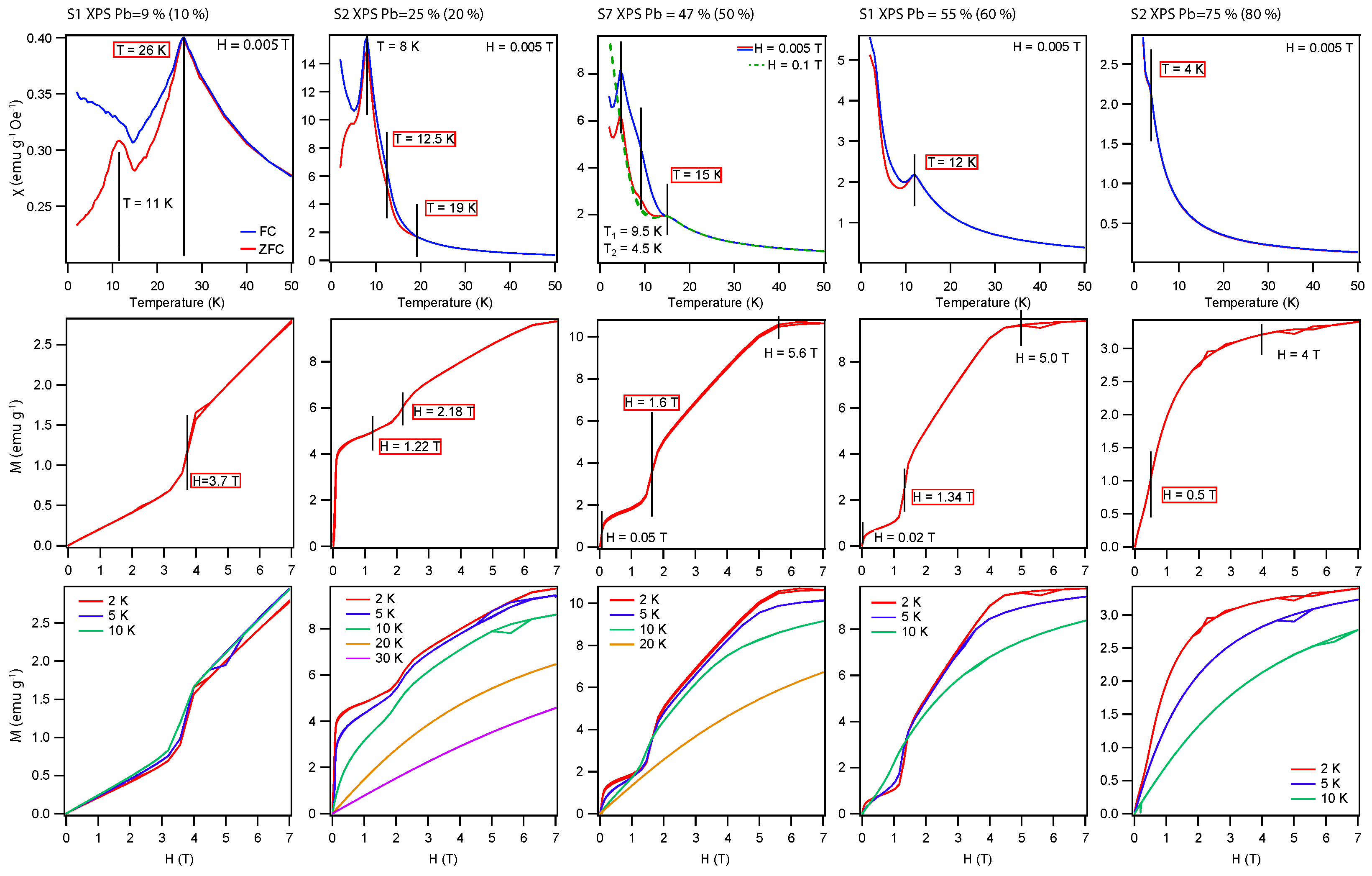

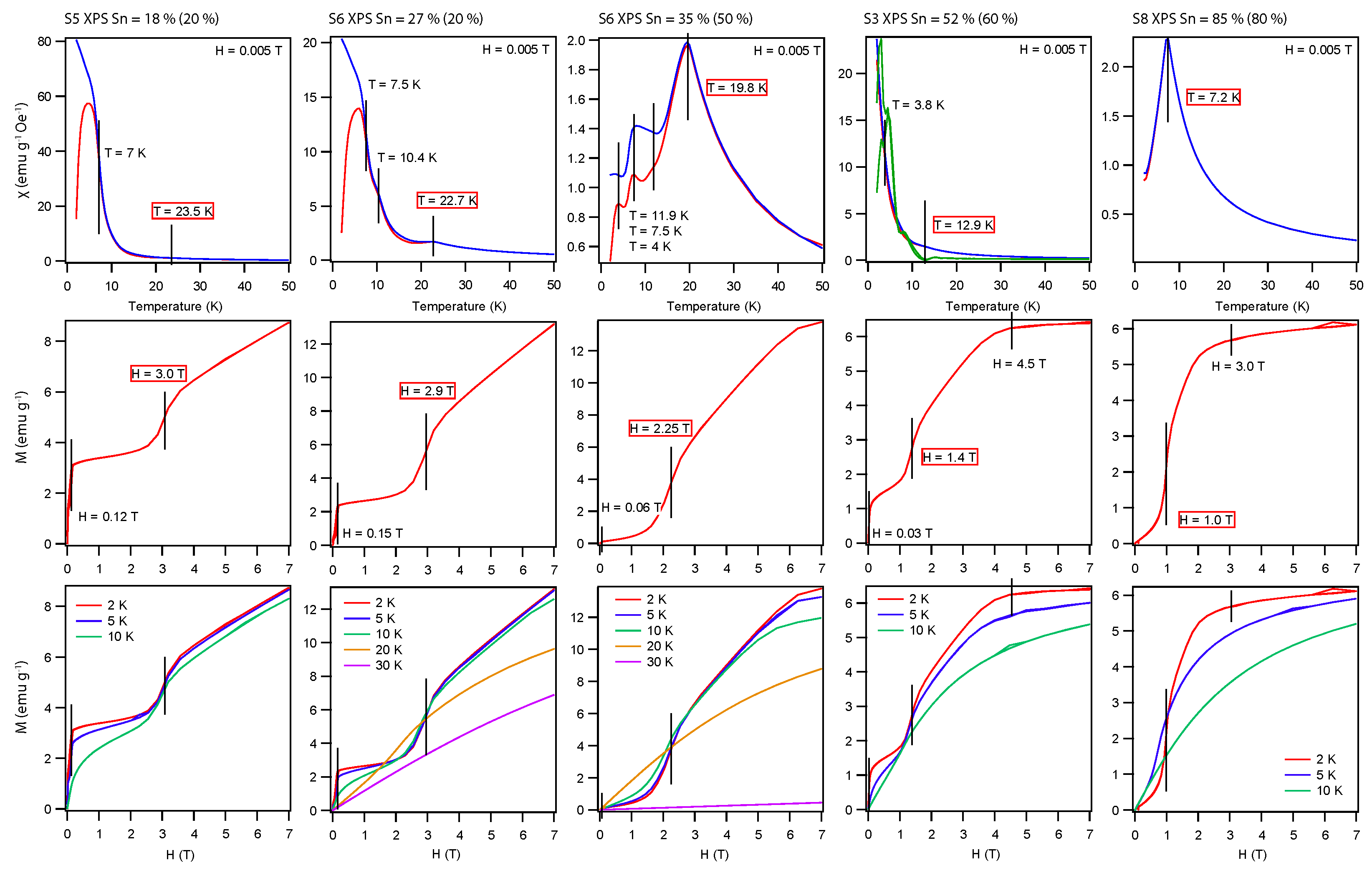

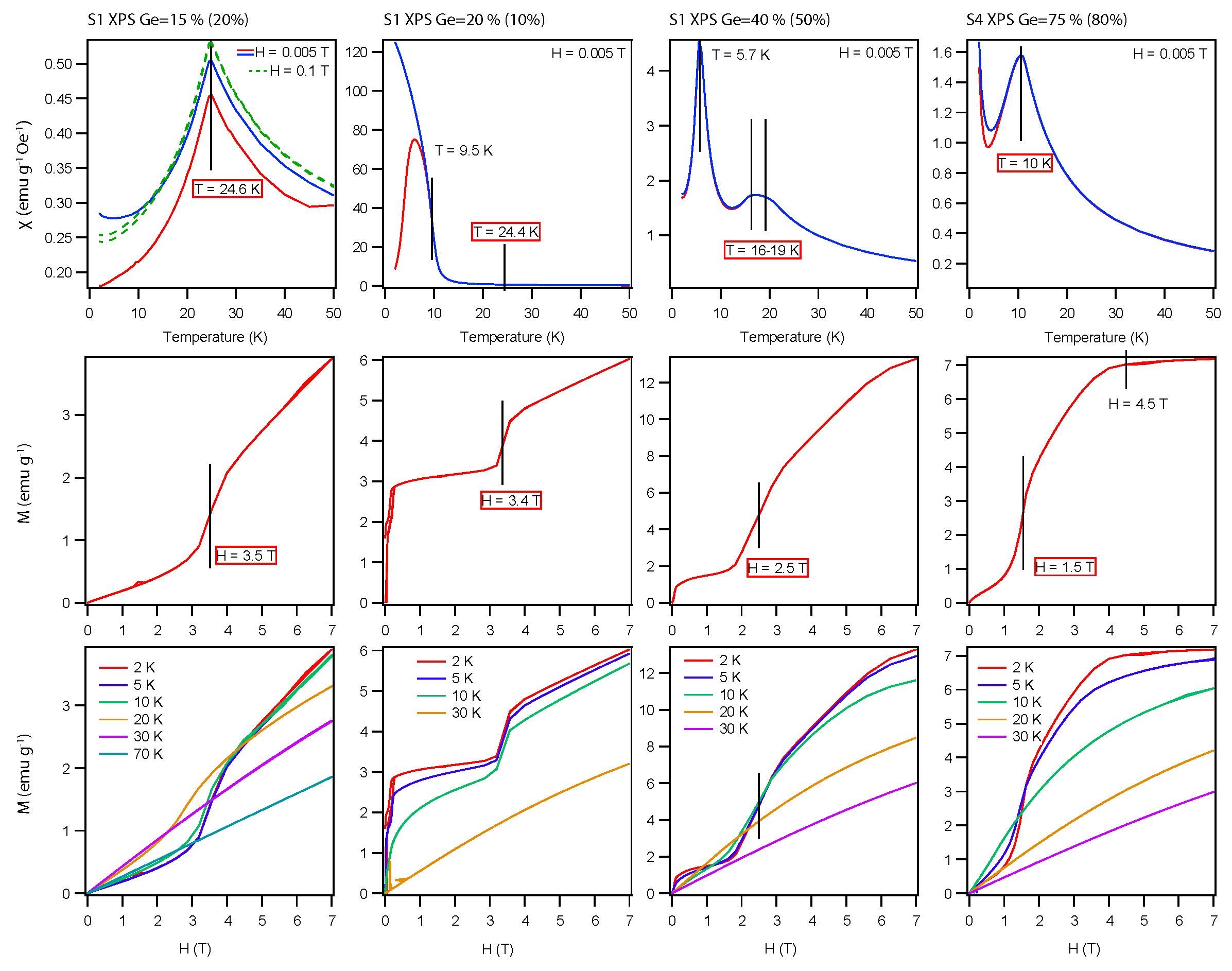

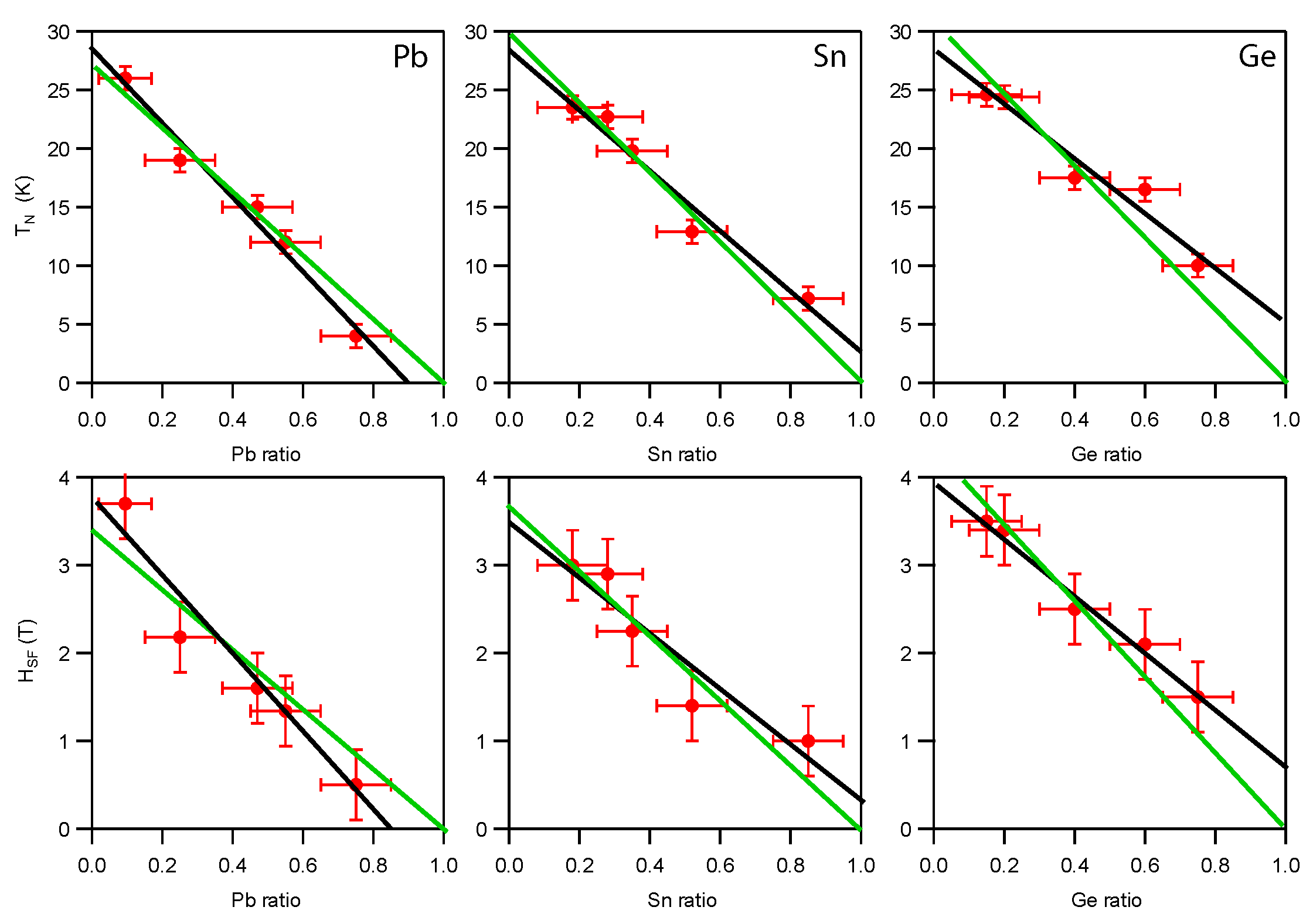

- The first approach involves the insertion of additional (m-1) [BiTe] QLs between one [MnBiTe] SL resulting in the series of compounds MnBiTe with [14,19,20,21,22]. This series includes the homologous phases MnBiTe (m=1: 124), MnBiTe (m=2: 147), and MnBiTe (m=3: 16), all of which can be classified as AFM TIs. However, as the number of [BiTe] QLs increases, significant changes occur in the magnetic properties. For the 147 phase, T is already 13 K and H does not exceed 0.3 T. The phase 16 possesses an uncertain type of magnetic ordering which can be either AFM or FM, depending on growth conditions and the presence of defects [23,24]. For phases with higher m, the system resembles non-interacting 2D ferromagnets formed by the [MnBiTe] SL [21].

- (2)

- The second approach is to substitute Bi atoms with Sb atoms, resulting in Mn(BiSb)Te compounds [25]. This substitution generally leads to an increase in the number of anti-site defects, such as Mn (Mn occupying the position of Bi or Sb atoms) [26,27]. Consequently, this substitution affects the magnetic order of the SL, transforming it from ferromagnetic to ferrimagnetic [18]. By adjusting the growth parameters, it is possible to further increase the number of anti-site defects and induce a transition from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic behavior in the ground state [27].

- (3)

- Another way is to dilute Mn atoms with non-magnetic atoms. The A = Ge, Pb, Sn elements can be chosen as suitable substituents. There are ternary TI compounds, such as ABiTe, with the same symmetry group as MnBiTe [13,28], allowing for arbitrary ratios of Mn substitution. Several studies [29,30,31,32,33] have demonstrated the synthesis of these crystals and confirmed the absence of additional substitution defects, as in the case of s substitution of Sb for Bi atoms.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARPES | Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy |

| AFM, FM, PM | Antiferromagnetic, ferromagnetic, paramagnetic |

| EDC | Energy distribution curves |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| H | Spin-flop transition field |

| QAHE | Quantum anomalous Hall effect |

| QL/SL | Quintuple [BiTe]/ septuple [MnBiTe] layers block |

| SQUID | Superconducting quantum interference device |

| TI | Topological insulator |

| T | Nèel temperature |

| XPS | X-ray photoemission spectroscopy |

| ZFC, FC | Zero field cooled, field cooled |

| Phases 124, 147, 16 | (MnA)BiTe with m = 1,2,3 (A = Ge, Pb, Sn) |

References

- Chang, C.Z.; Li, M. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in time-reversal-symmetry breaking topological insulators. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2016, 28, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Xue, Q.K. The Road to High-Temperature Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect in Magnetic Topological Insulators. SPIN 2019, 09, 1940016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustino, F.; Lee, J.H.; Trier, F.; Bibes, M.; Winter, S.M.; Valentí, R.; Son, Y.W.; Taillefer, L.; Heil, C.; Figueroa, A.I.; et al. The 2021 quantum materials roadmap. Journal of Physics: Materials 2021, 3, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Z.; Liu, C.X.; MacDonald, A.H. Colloquium: Quantum anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2023, 95, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otrokov, M.M.; Rusinov, I.P.; Blanco-Rey, M.; Hoffmann, M.; Vyazovskaya, A.Y.; Eremeev, S.V.; Ernst, A.; Echenique, P.M.; Arnau, A.; Chulkov, E.V. Unique Thickness-Dependent Properties of the van der Waals Interlayer Antiferromagnet MnBi2Te4 Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 107202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otrokov, M.M.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Bentmann, H.; Estyunin, D.; Zeugner, A.; Aliev, Z.S.; Gaß, S.; Wolter, A.U.B.; Koroleva, A.V.; Shikin, A.M.; et al. Prediction and observation of an antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nature 2019, 576, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, M.; Zhu, T.; Xing, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Topological Axion States in the Magnetic Insulator MnBi2Te4 with the Quantized Magnetoelectric Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 206401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Du, S.; Wang, Z.; Gu, B.L.; Zhang, S.C.; He, K.; Duan, W.; Xu, Y. Intrinsic magnetic topological insulators in van der Waals layered MnBi2Te4-family materials. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaaw5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, K.; Liao, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, L.; Tang, L.; Feng, X.; et al. Experimental Realization of an Intrinsic Magnetic Topological Insulator. Chinese Physics Letters 2019, 36, 076801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Shi, M.Z.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.H.; Zhang, Y. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Science 2020, 367, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; He, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Robust axion insulator and Chern insulator phases in a two-dimensional antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nature Materials 2020, 19, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Luo, T.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. High-Chern-number and high-temperature quantum Hall effect without Landau levels. National Science Review 2020, 7, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Kim, T.H.; Park, C.H.; Chung, C.Y.; Lim, Y.S.; Seo, W.S.; Park, H.H. Crystal structure, properties and nanostructuring of a new layered chalcogenide semiconductor, Bi2MnTe4. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 5532–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliev, Z.S.; Amiraslanov, I.R.; Nasonova, D.I.; Shevelkov, A.V.; Abdullayev, N.A.; Jahangirli, Z.A.; Orujlu, E.N.; Otrokov, M.M.; Mamedov, N.T.; Babanly, M.B.; Chulkov, E.V. Novel ternary layered manganese bismuth tellurides of the MnTe-Bi2Te3 system: Synthesis and crystal structure. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 789, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Heitmann, T.; Huang, Z.; Chen, K.Y.; Cheng, J.G.; Wu, W.; Vaknin, D.; Sales, B.C.; McQueeney, R.J. Crystal growth and magnetic structure of MnBi2Te4. Phys. Rev. Materials 2019, 3, 064202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Yu, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, S. Antiferromagnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4: synthesis and magnetic properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

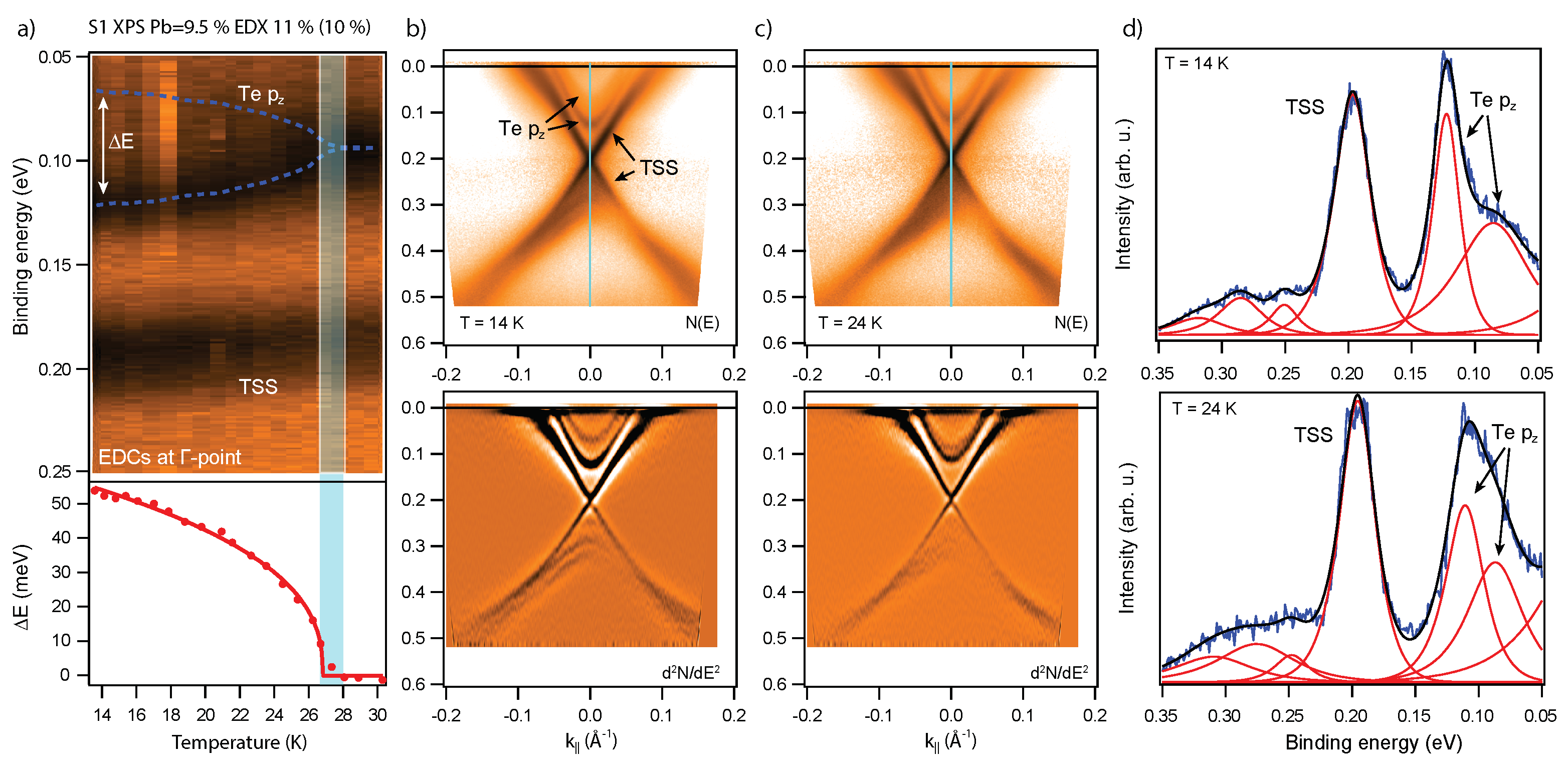

- Estyunin, D.A.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Shikin, A.M.; Schwier, E.F.; Otrokov, M.M.; Kimura, A.; Kumar, S.; Filnov, S.O.; Aliev, Z.S.; Babanly, M.B.; Chulkov, E.V. Signatures of temperature driven antiferromagnetic transition in the electronic structure of topological insulator MnBi2Te4. APL Materials 2020, 8, 021105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Ke, L.; Yan, J.; McDonald, R.D.; McQueeney, R.J. Defect-driven ferrimagnetism and hidden magnetization in MnBi2Te4. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 184429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, F.; Sasase, M.; Ienaga, K.; Obata, Y.; Yukawa, R.; Horiba, K.; Kumigashira, H.; Okuma, S.; Inoshita, T.; Hosono, H. Natural van der Waals heterostructural single crystals with both magnetic and topological properties. Science Advances 2019, 5, eaax9989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Gordon, K.N.; Liu, P.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Hao, P.; Narayan, D.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Brawer, H.; Ramirez, A.P.; Ding, L.; Cao, H.; Liu, Q.; Dessau, D.; Ni, N. A van der Waals antiferromagnetic topological insulator with weak interlayer magnetic coupling. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimovskikh, I.I.; Otrokov, M.M.; Estyunin, D.; Eremeev, S.V.; Filnov, S.O.; Koroleva, A.; Shevchenko, E.; Voroshnin, V.; Rybkin, A.G.; Rusinov, I.P.; et al. Tunable 3D/2D magnetism in the (MnBi2Te4)(Bi2Te3)m topological insulators family. npj Quantum Materials 2020, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikin, A.M.; Estyunin, D.A.; Glazkova, D.A.; Fil’nov, S.O.; Klimovskikh, I.I. Electronic and Spin Structures of Intrinsic Antiferromagnetic Topological Insulators of the MnBi2Te4(Bi2Te3)m Family and Their Magnetic Properties (Brief Review). JETP Letters 2022, 115, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Zhu, Y.; Miao, L.; Fernandez-Mulligan, S.; Green, E.; Mei, R.; Tan, H.; Yan, B.; Liu, C.X.; Alem, N.; Mao, Z.; Yang, S. Delicate Ferromagnetism in MnBi6Te10. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 9815–9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcakaev, A.V.; Rubrecht, B.; Facio, J.I.; Zabolotnyy, V.B.; Corredor, L.T.; Folkers, L.C.; Kochetkova, E.; Peixoto, T.R.F.; Kagerer, P.; Heinze, S.; et al. Intermixing-Driven Surface and Bulk Ferromagnetism in the Quantum Anomalous Hall Candidate MnBi6Te10. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2203239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Fei, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, B.; Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P.; Wei, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Z.; et al. Intrinsic magnetic topological insulator phases in the Sb doped MnBi2Te4 bulks and thin flakes. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Nambu, Y.; Koretsune, T.; Xiangyu, G.; Yamamoto, T.; Brown, C.M.; Kageyama, H. Realization of interlayer ferromagnetic interaction in MnSb2Te4 toward the magnetic Weyl semimetal state. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 195103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.L.; Zheng, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Chi, M.; Wu, Y.; Chakoumakos, B.C.; McGuire, M.A.; Sales, B.C.; Wu, W.; Yan, J. Site Mixing for Engineering Magnetic Topological Insulators. Phys. Rev. X 2021, 11, 021033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, L.A.; Kuznetsov, V.L.; Rowe, D.M. Thermoelectric properties and crystal structure of ternary compounds in the Ge(Sn,Pb)Te-Bi2Te3 systems. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2000, 61, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Naveed, M.; Chen, B.; Du, Y.; Guo, J.; Xie, H.; Fei, F. Magnetic and electrical transport study of the antiferromagnetic topological insulator Sn-doped MnBi2Te4. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 144407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Yao, Y.T.; Hu, C.; Feng, E.; Cao, H.; Mazin, I.I.; Chang, T.R.; Ni, N. Magnetic dilution effect and topological phase transitions in (Mn1-xPbx)Bi2Te4. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 045121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changdar, S.; Ghosh, S.; Vijay, K.; Kar, I.; Routh, S.; Maheshwari, P.K.; Ghorai, S.; Banik, S.; Thirupathaiah, S. Nonmagnetic Sn doping effect on the electronic and magnetic properties of antiferromagnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2023, 657, 414799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, A.S.; Usachov, D.Y.; Tarasov, A.V.; Fedorov, A.V.; Bokai, K.A.; Klimovskikh, I.; Stolyarov, V.S.; Sergeev, A.I.; Lavrov, A.N.; Golyashov, V.A.; et al. Magnetic Dirac semimetal state of (Mn,Ge)Bi2Te4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.13024. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, A.V.; Makarova, T.P.; Estyunin, D.A.; Eryzhenkov, A.V.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Golyashov, V.A.; Kokh, K.A.; Tereshchenko, O.E.; Shikin, A.M. Topological Phase Transitions Driven by Sn Doping in (Mn1-xSnx)Bi2Te4. Symmetry 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Q.; Teo, K.L.; Jalil, M.B.A.; Liew, T. Compositional dependencies of ferromagnetic Ge1-xMnxTe grown by solid-source molecular-beam epitaxy. Journal of Applied Physics 2006, 99, 08D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Springholz, G.; Lechner, R.T.; Groiss, H.; Kirchschlager, R.; Bauer, G. Molecular beam epitaxy of single phase GeMnTe with high ferromagnetic transition temperature. Journal of Crystal Growth 2011, 323, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Taskin, A.A.; Sasaki, S.; Segawa, K.; Ando, Y. Optimizing Bi2-xSbxTe3-ySey solid solutions to approach the intrinsic topological insulator regime. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 165311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Miotkowski, I.; Liu, C.; Tian, J.; Nam, H.; Alidoust, N.; Hu, J.; Shih, C.K.; Hasan, M.Z.; Chen, Y.P. Observation of topological surface state quantum Hall effect in an intrinsic three-dimensional topological insulator. Nature Physics 2014, 10, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokh, K.A.; Makarenko, S.V.; Golyashov, V.A.; Shegai, O.A.; Tereshchenko, O.E. Melt growth of bulk Bi2Te3 crystals with a natural p-n junction. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokh, K.A.; Andreev, Y.M.; Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Lanskii, G.V.; Kokh, A.E. Growth of GaSe and GaS single crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2011, 46, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasawa, H.; Schwier, E.F.; Arita, M.; Ino, A.; Namatame, H.; Taniguchi, M.; Aiura, Y.; Shimada, K. Development of laser-based scanning μ-ARPES system with ultimate energy and momentum resolutions. Ultramicroscopy 2017, 182, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuszkiewicz, W.; Hennion, B.; Witkowska, B.; Łusakowska, E.; Mycielski, A. Neutron scattering study of structural and magnetic properties of hexagonal MnTe. physica status solidi (c) 2005, 2, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogi, M.; Yoshimi, R.; Tsukazaki, A.; Yasuda, K.; Kozuka, Y.; Takahashi, K.S.; Kawasaki, M.; Tokura, Y. Magnetic modulation doping in topological insulators toward higher-temperature quantum anomalous Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 182401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Wang, B.S.; Yan, J.Q.; Parker, D.S.; Zhou, J.S.; Uwatoko, Y.; Cheng, J.G. Suppression of the antiferromagnetic metallic state in the pressurized MnBi2Te4 single crystal. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 094201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).