Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

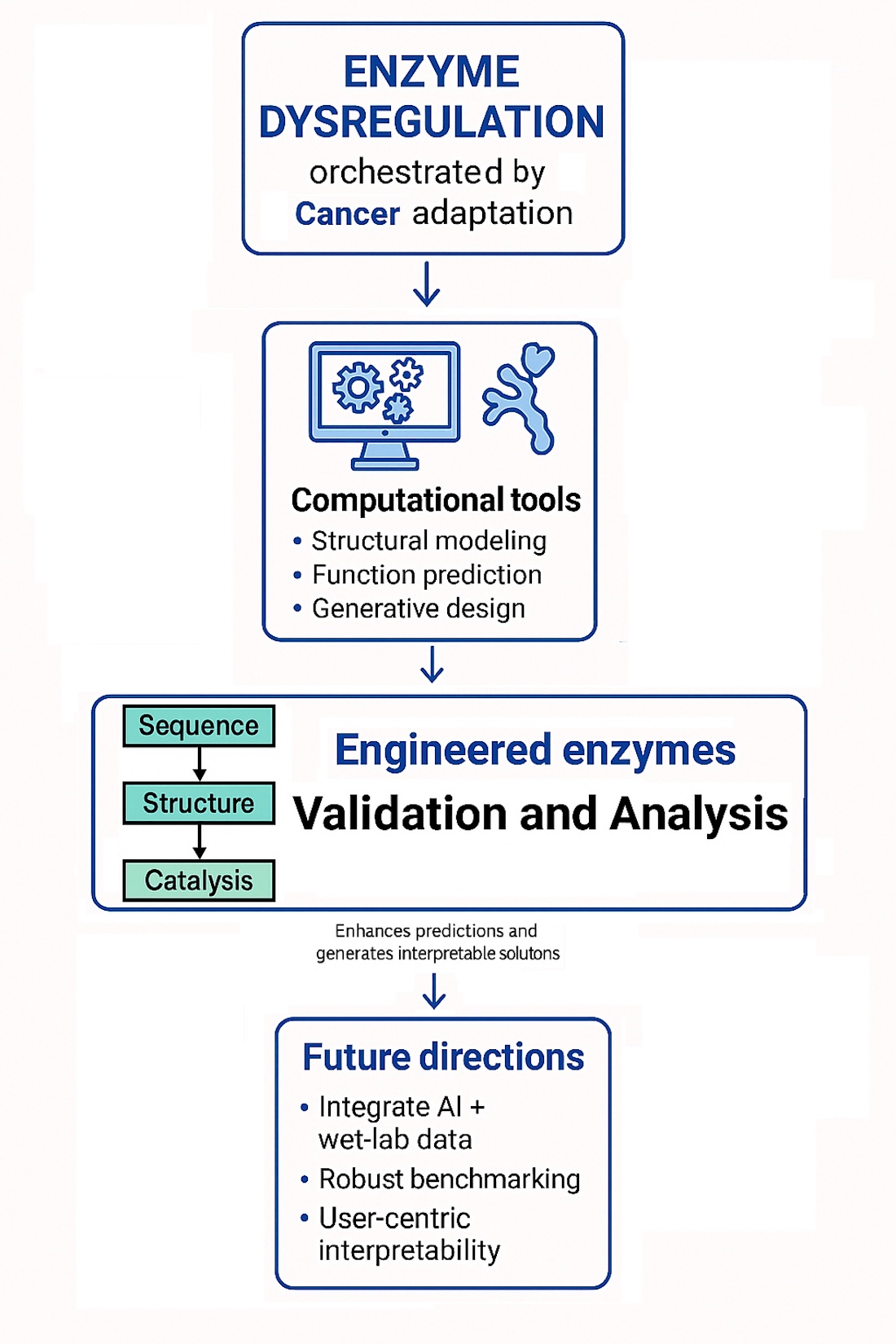

1. Introduction

2. Background

- Correctly aligning substrates within the active site to ensure effective molecular interactions.

- Inducing strain or distortion in specific substrate bonds, making them more susceptible to cleavage.

- Providing an optimal microenvironment, such as acidic or basic side chains, that stabilizes transition states.

- Forming transient covalent intermediates with substrates, which lowers the energy required to proceed through the reaction pathway.

- Temperature. Enzyme activity generally increases with temperature due to enhanced molecular motion, reaching a peak at an optimum temperature. Beyond this point, elevated temperatures can lead to enzyme denaturation, a loss of structural integrity that diminishes or abolishes catalytic activity.

- Enzyme concentration. Increasing the amount of enzyme present in a reaction typically raises the reaction rate, provided that substrate availability is not limiting. However, once substrate molecules are fully utilized, further increases in enzyme concentration yield diminishing returns.

- Substrate concentration. At low substrate levels, reaction velocity increases rapidly with substrate concentration. As enzyme active sites become saturated, the reaction rate plateaus, approaching a maximum velocity () as described by Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

- pH levels. Each enzyme exhibits optimal activity within a specific pH range, which reflects the ionization states of amino acid residues in the active site and substrate. Deviation from this range can disrupt ionic interactions or hydrogen bonding, leading to reduced activity or irreversible denaturation.

- Competitive inhibitors. These molecules resemble the enzyme’s natural substrate and bind to the active site, competing with the substrate. This form of inhibition can often be overcome by increasing the substrate concentration.

- Non-competitive inhibitors. These bind to allosteric sites (locations other than the active site), causing conformational changes that diminish the enzyme’s ability to bind its substrate or carry out catalysis, regardless of substrate concentration[285].

3. Computational Tools in Enzyme Engineering

- Sequence–structure relationship: The amino acid sequence of the enzyme dictates its folding into a unique three-dimensional structure. This structure, including dynamic conformational states, is essential for the proper positioning of functional groups necessary for catalysis.

- Enzyme as a nanomachine: The enzyme facilitates substrate recognition and binding, correctly orienting the substrate within the active site. Afterward, it assists in the formation and release of the product, while minimizing interference from product inhibition or solvent interactions. This machine-like behavior ensures catalytic efficiency and specificity.

- Catalytic transition state stabilization: Key active-site residues interact with the substrate to stabilize the high-energy transition state, thus lowering the activation energy required for the reaction. This step is crucial in bond breaking and bond formation processes.

- Exploration of natural enzyme diversity, through genome mining and metagenomics, to discover novel catalytic functions.

- Enzyme engineering, which modifies natural enzymes to enhance performance, extend substrate scope, or improve operational stability.

- Mechanism redesign, aimed at introducing entirely new catalytic activities or altering reaction pathways.

- Computational enzyme design, which involves de novo construction of enzymes using structure-guided and machine learning-assisted methods.

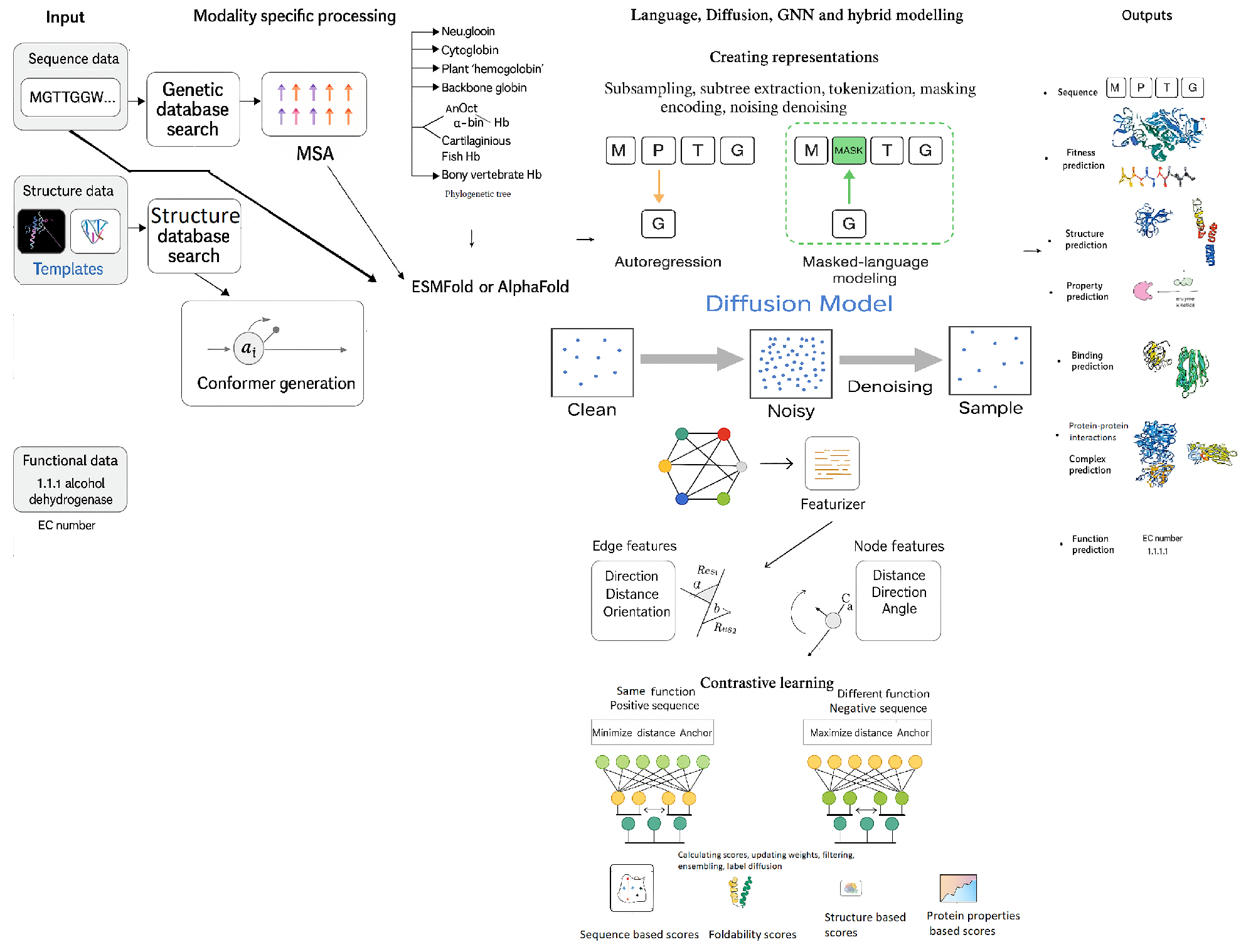

4. Deep Learning Models for Enzyme Engineering

- Autoregressive modeling, where the model is trained to predict each successive residue based on all previous residues in the sequence.

- Masked language modeling, where the model reconstructs missing or masked residues using the context of the surrounding sequence.

- MSA Attention, which captures conserved sequence motifs and patterns from MSAs, reflecting evolutionary constraints essential for protein folding.

- Pair Attention, which instead of just considering which residues are close together, uses specialized components such as "Triangle Multiplication" and "Triangle Attention" to model spatial relationships between groups of three residues - building blocks of proteins. These modules help accurately predict inter-residue distances and angles, crucial for constructing the final 3D structure, and allows the model to infer higher-order geometric relationships, surpassing the sequential modeling limitations of traditional transformer layers.

- Reconstruct plausible evolutionary trajectories,

- Detect horizontal gene transfer events,

- Arrange proteins in pseudotime to infer the relative timing of evolutionary divergence.

- Domain shuffling, which recombines existing structural modules to generate new protein functions;

- Gene duplication, which permits the functional divergence of proteins while preserving ancestral roles;

- Natural selection, which filters variants based on functional fitness in changing environments.

- Generator. Creates new protein sequences.

- Discriminator. Acts as a quality control by distinguishing real sequences from generated (fake) ones.

- Pocket data. Identifies likely active or binding sites within enzymes.

- Contact constraints. Specifies residues that should be spatially close, mimicking atomic contacts.

- Docking data. Provides orientation or distance info between enzyme and ligand or between protein subunits.

5. Interoperability and Assessment

- RMSD (Root-Mean-Square Deviation) is a foundational metric that calculates the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures. It provides a straightforward measure of structural similarity but is sensitive to outliers and may not accurately reflect functional or local similarities.

- GDT addresses RMSD’s limitations by focusing on the percentage of residues that deviate by less than a set distance threshold (e.g., 1Åor 2Å). It provides a more holistic view of structural similarity, particularly effective for evaluating predictions of multi-domain or flexible proteins.

- LCS complements GDT by identifying the longest uninterrupted stretch of residues that can be superimposed under an RMSD threshold. It emphasizes local consistency, which is crucial in identifying preserved motifs and active sites in enzyme design.

- CAD-score measures the difference in residue-residue contact areas between a model and a reference. It is calculated using Voronoi tessellation to evaluate contact surfaces and is particularly effective in judging physical realism. Unlike RMSD and GDT, CAD-score can directly assess the accuracy of domain interfaces and multimeric assemblies.

- Planarity. Many parts of biomolecules, especially aromatic rings like those in phenylalanine or tyrosine, are expected to be flat due to the nature of their chemical bonds. If a predicted structure distorts this flat shape, it may signal a physically unrealistic conformation that wouldn’t be stable in real conditions.

- Bond lengths. Atoms in proteins are held together by covalent bonds with known average distances. Deviations from these expected values suggest the model may have introduced structural artifacts, which could affect protein stability or activity.

- Steric clashes. In real proteins, atoms are spaced so that they don’t overlap. If two atoms are too close, closer than their physical space allows, it creates a steric clash, indicating an impossible structure. These clashes often arise from poor side-chain packing or inaccurate folding predictions and can disrupt protein function.

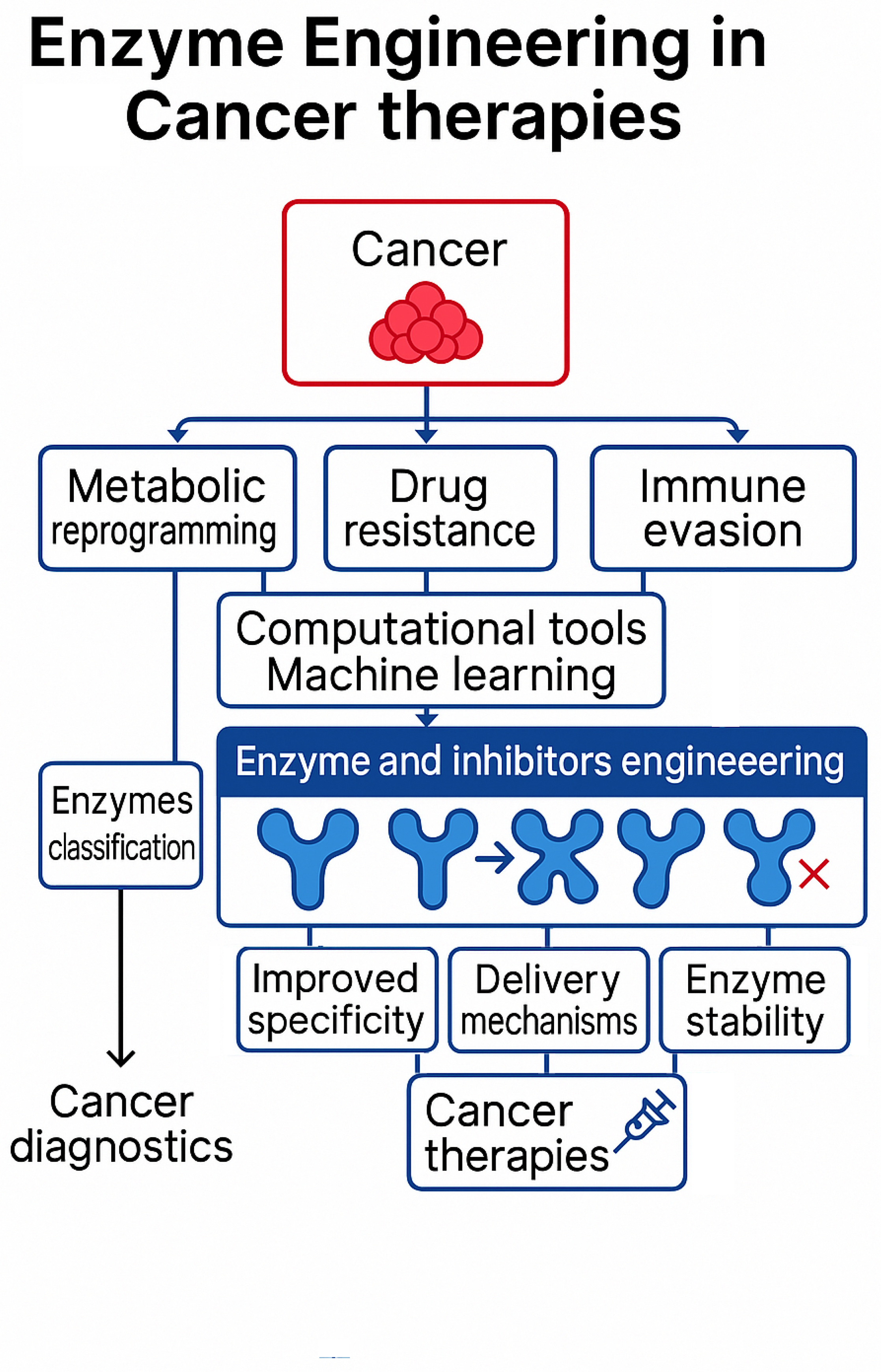

6. Cancer and the Role of Enzymes in Cancer Study

-

Intrinsic Pathway. Triggered by internal cellular stressors such as DNA damage or oxidative stress, this pathway involves the mitochondria releasing cytochrome c into the cytoplasm. This release activates caspases, leading to cell death.Triggered by internal cellular stressors such as DNA damage or oxidative stress, the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is primarily regulated by mitochondria, the energy-producing organelles of the cell. Oxidative stress occurs when an imbalance between reactive oxygen species and antioxidants leads to cellular damage, often compromising mitochondrial function. In response, mitochondria release cytochrome c, a small heme protein that normally facilitates electron transfer in the electron transport chain but, when released into the cytoplasm (the gel-like substance filling the cell and surrounding all organelles), acts as a key apoptotic signal. Once in the cytoplasm, cytochrome c activates initiator caspases. Caspases are a family of proteolytic enzymes - cysteine proteases that cleave target proteins at specific aspartic acid residues, orchestrating a controlled sequence of cellular disassembly. Once activated, executioner caspases systematically degrade cellular components, leading to programmed cell death[280]. This controlled dismantling of the cell ensures minimal damage to surrounding tissues and prevents inflammation, highlighting the tightly regulated nature of apoptosis in maintaining cellular homeostasis.

- Extrinsic Pathway. Initiated by external signals, these signals come from specialized molecules called death ligands, such as Fas ligand (FasL) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which bind to death receptors on the cell surface. When a death ligand binds to its matching receptor (e.g., Fas receptor or TNF receptor), it triggers the formation of a protein complex known as the death-inducing signaling complex. This complex directly activates initiator caspases, which function similarly to caspases in the intrinsic pathway[278].

- Self-sufficiency in growth signals,

- Insensitivity to growth inhibitory (antigrowth) signals,

- Evasion of programmed cell death (apoptosis),

- Limitless replicative potential,

- Sustained vascularity (angiogenesis),

- Tissue invasion and metastasis.

- as drug delivery facilitators,

- as direct therapeutic agents,

- as metabolic regulators influencing cancer proliferation.

6.1. Enzyme-Aided Drug Delivery

- Surgery. Optimal for localized tumors, surgical resection aims to remove the tumor entirely, offering the best chance for a cure when the cancer is confined to a specific area [263].

- Chemotherapy. This systemic therapy targets rapidly dividing cells, effectively treating cancers that have spread beyond the primary site. However, chemotherapy can also affect healthy cells, leading to systemic toxicity [263].

- Radiotherapy. Utilizing ionizing radiation, radiotherapy aims to kill cancer cells or inhibit their growth. It is often used in conjunction with other treatments to enhance effectiveness [263].

- Targeted Therapy. This approach uses drugs or other substances to precisely target cancer cells, often by inhibiting specific molecules involved in tumor growth. For example, imatinib is a kinase inhibitor used to treat Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia [274].

- Small Molecule Targeted Agents. These therapies inhibit specific molecular targets involved in cancer progression [278].

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs). ADCs combine monoclonal antibodies, which are designed to recognize specific proteins on cancer cells, with cytotoxic agents, delivering chemotherapy directly to cancer cells while minimizing damage to normal tissues [274].

- Cell-Based Therapies. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies involve modifying a patient’s T cells to attack cancer cells [274].

- Gene Therapy. This approach involves altering the genetic material within a patient’s cells to treat or prevent disease. Gene therapies aim to correct genetic defects or enhance the immune system’s ability to fight cancer [274].

- Target antigen: Must possess high specificity, low exfoliative properties to minimize shedding of the antigen into the bloodstream, endocytosis capabilities to facilitate the internalization of the ADC into the cancer cells.

- Antibody: Binds to the specific antigen on the target cell.

- Linker: Should be stable, specific for tumor conditions, and allow efficient toxin release. Linkers can be divided into cleavable linkers (chemical cleavage linkers, enzyme catalyzed cleavage linkers, photo-cleavable linkers) and non-cleavable linkers (sulfide bond linkers, maleimide bond linkers); cleavable linkers are a prerequisite for exerting bystander killing effect, hence becoming the mainstream trend of ADC linkers.

- Toxin: Must exhibit strong cytotoxicity, high stability, and controlled degradation. Within the cell, the toxin is released after being degraded by lysosomes, ultimately leading to the apoptosis of the target cell.

- Coupling method: Influences drug uniformity and loading for optimized therapeutic effects.

7. Enzyme-Drug Interactions in Cancer Therapy

7.1. Enzymes as Direct Therapeutic Agents

7.2. Detection and Modulation of Metabolic Reprogramming of Cancer

7.3. Targeting Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming

- Hexokinase (HK2): Initiates glycolysis by phosphorylating glucose, trapping it inside the cell.

- Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1) functions as a key checkpoint, modulating glucose breakdown based on cellular energy demands.

- Pyruvate Kinase M2 (PKM2) governs the final step of glycolysis and can reroute glucose metabolism toward biosynthetic pathways essential for rapid cell division.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) converts pyruvate into lactate, especially under hypoxic conditions, supporting cancer cell survival and contributing to drug resistance.

7.4. Enzymatic Regulation in Cancer Immunotherapy

8. Conclusions

- Immunogenicity. Many therapeutic enzymes, especially those derived from non-human sources, can elicit immune responses that limit their efficacy and safety.

- Stability and bioavailability. Enzymes must maintain catalytic activity under physiological conditions, often requiring stabilization through chemical modification or encapsulation.

- Targeted delivery. Achieving tissue- or tumor-specific localization remains a major hurdle, necessitating advances in delivery vectors such as nanoparticles, antibody conjugates, or gene therapy platforms.

- Manufacturing scalability. Producing large quantities of highly pure, active enzymes in a cost-effective and reproducible manner is essential for clinical and commercial viability.

- Regulatory and translational hurdles. Standardizing protocols for clinical evaluation, safety assessment, and regulatory approval is critical for successful integration into cancer care.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

Appendix A. Protein engineering machine learning models

| No. | Model Name | Year | Input Data Type | Output Type | Datasets Used | Performance Metrics | Performance Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ProGen[?] | 2020 | Sequences | Sequences | Uniparc[331], UniProtKB[330], SWISS-PROT[329], TrEMBL[328], Pfam[327], NCBI taxonomic information[326] | Perplexity (PPL), mean per token hard accuracy (HA)1 and soft accuracy (SA)2 primary sequence similarity(SS)3, secondary structure accuracy(SSA)4, conformational energy analysis5 | 8.56 PPL, HA in-distribution 45%, out-of-distribution 22%, Fine-Tuned on OOD-80 50%, SA = 20% HA, SS 25% baseline, SSA 25% baseline | Limited structure integration |

| 2 | ProteinMPNN[13] | 2021 | Protein sequences | 3D structures | Protein Data Bank (PDB)[310], CATH[323] | PDB Test Accuracy (%)6, PDB Test Perplexity7, AlphaFold Model Accuracy (%)8 | with random decoding step: PDB 50.8%, with noise 47.9%, Perplexity 4.74, with noise 5.25, AlphaFold 46.9%, with noise 48.5% | Dependent on high-quality, static backbone inputs. The message-passing framework may not fully capture long-range, non-local interactions, allosteric effects |

| 3 | ProtTrans[200] | 2021 | Sequences | Embeddings, annotations | Uniref50[324], Uniref100[324], BFD(Big Fantastic Database)9[325] | Q3/Q810, Q10 11, Q2 12 | Q3 87%, Q8 77%, Q10 81%, Q2 91% | Requires fine-tuning for specific tasks |

| 4 | AlphaFold 2[204] | 2021 | Sequence, MSA, Homology 3D atom coordinates | 3D protein structures | custom BFD, PDB[310], for MSA Uniref90[324], Uniclust30[321], MGnify[320] | Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), pLDDT13, C local-distance difference test (lDDT-C)14, pTM15 | RMSD ∼ 1.46Å, pLDDT 0.76, lDDT-C∼ 80, pTM 0.85 | Predicts static structures |

| 5 | GEMME[6] | 2022 | Protein sequences | Fitness predictions | Mutations dataset16 | Spearman Correlation Coefficient (SCC) | 0.53 | Relies on the quality and diversity of multiple sequence alignments, sensitive to the specific filtering criteria, may struggle to capture complex, non-linear sequence-function relationships. |

| 6 | ProtST[9] | 2022 | Sequences | Secondary structure | ProtDescribe17 | Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR)18, Function annotation 19, Binary, subcellular localization accuracy, Fitness landscape Spearman’s 20 | AUPR 0.898, 0.878, Binary 93.04, Subcellular 83.39, Spearman’s 0.895 | Focused on structure tasks |

| 7 | OPUS-GO[113] | 2022 | Protein sequences | Functional annotations | not explicitly mentioned | AUPR, on GO21 term predictions, AUC22 , Calcium ion binding F1-score23, Binary, Subcellular localization Accuracy, AUPR and on two protein EC number prediction datasets | GO AUPR 0.678 , GO 0.690, AUC 0.826 , F1-score 0.327, Bin 0.931, Sub 0.837, Ion 0.827, EC AUPR 0.902, EC 0.881 | Relies on curated graphs |

| No. | Model Name | Year | Input Data Type | Output Type | Datasets Used | Performance Metrics | Performance Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GPDL-H[11] | 2023 | Protein sequences, structure | Structure optimization | seeding model CATH[323], PDB | Sc-TM-score24, Motif RMSD25, PAE26, pLDDT27 | Sc-TM-score 0.99, Motif RMSD near 0.58 Å, max PAE 2.43, pLDDT 90.66 | Requires large-scale training |

| 2 | RFdiffusion[12] | 2023 | Protein sequences | Structural and functional properties | noising structures from PDB[310] for up to 200 steps | RMSD generated vs AlphaFold2[204], TM-score | RMSD 0.90, 0.98, 1.15, 1.67 Å(increases with protein length), TM-score 100 amino acids 0.85, 200 amino acids 0.75, 300 amino acids 0.65, 400 amino acids 0.55, 600 amino acids 0.50, 800–1000 amino acids 0.40 (decreases with protein length) | Computationally expensive |

| 3 | TranceptEVE[5] | 2023 | Sequences | Fitness landscapes | ProteinGym[318], ClinVar[319], EVE DMS[319] | Protein mutations Spearman correlation of ProteinGym[2]28 data with Low, Medium , High Depth29, AUC of ClinVar[319] data | Spearman correlation Low 0.460, Medium 0.463, High 0.508, All30 0.472, AUC 0.767 | High computational cost |

| 4 | Tranception[94] | 2023 | Sequences | Mutational landscapes | UniProt[317] | Perplexity, log-likelihood | Perplexity 1.2 | Limited scalability for long proteins |

| 5 | SaProt[7] | 2023 | Sequences | Mutational fitness scores | ProteinGym[318], ClinVar[319] | ClinVar AUC, ProteinGym Spearman’s , Thermostability Spearman’s , Human Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) ACC%, Metal Ion Binding ACC%, EC , GO Molecular function (MF), Biological process(BP), Cellular component(CC) , DeepLoc Subcellular and Binary ACC | ClinVar AUC 0.909, ProteinGym Spearman’s 0.478, Thermostability Spearman’s 0.724, HumanPPI ACC% 86.41, Metal Ion Binding ACC% 75.75, EC 0.882, GO MF 0.682, GO BP 0.486, GO CF 0.479, Subcellular 85.57, Binary 93.55 | Dependent on MSA |

| 6 | TTT[226] | 2023 | Sequences | Task-dependent outputs | MaveDB[346], DeepLoc[316] | Avg. Spearman, TM-score, LDDT | SaProt (650M) + TTT 0.4583, ESM3 + TTT TM-score 0.3954, ESMFold + TTT LDDT 0.5047 | Task-dependent architecture |

| 7 | AlphaProteo[221] | 2024 | Sequences | Protein binders | UniProt[317], PDB[310] | Experimental Success Rate (%)31 tested on BHRF132 SC2RBD 33 IL-7RA34 PD-L135 TrkA36, Binding Affinity ( in nM)37 | BHRF1 88, SC2RBD 8.5, IL-7RA 24.5, PD-L1 9.6, TrkA 9.6, VEGF-A 33, n | Needs fine-tuning |

| 8 | Stability Oracle[366] | 2024 | Structural data | Stability predictions () | C2878, cDNA117K, T2837 from MMseqs2[301] | AUROC, Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC), Spearman, precision, RMSE | p53 variations AUROC 0.83, Pearson 0.75, Spearman 0.76, precision 0.55, T2837 RMSE 0.0033 | Requires experimental validation |

| 9 | Chai-1[297] | 2024 | Sequence | Structure prediction | Custom datasets, PDB | The fraction of predictions with ligand root mean square deviation (ligand RMSD) to the ground truth lower than 2 Åfor PoseBusters benchmark set[344] | TM-score > 0.75, RMSD < 1.5Å | Requires large-scale training |

| 10 | LigandMPNN[295] | 2024 | Structural data | Protein-ligand binding predictions | PDB[310]38 | Sequence recovery for residues interacting with small molecules, nucleotides, metals, RMSD, Chi1 fraction39 Chi2, Chi3, and Chi4 fractions40 | Chi1 (small molecules) 86.1%, Chi1 (nucleotides) 71.4%, Chi1 (metals) 79.3% , weighted average Chi1, Chi2, Chi3, and Chi4 fractions for small molecules 84.0%, Chi2 64.0%, Chi3 28.3%, Chi4 18.7%, RMSD near small molecules ∼0.5–1.2Å, RMSD near DNA or RNA in protein-DNA or protein-RNA complexes, RMSD near metal ions ∼0.5–1.1Å | Limited to known binding sites |

| 11 | MODIFY[36] | 2024 | Protein sequences, structural data | Structure, function, stability predictions | For evaluation: ProteinGym[94,318] for zero-shot protein fitness, GB1[315], ParD3[311,313],CreiLOV[314] for high-order mutants | Spearman | all proteins ∼0.42 – 0.65, Low MSA Depth ∼0.35 – 0.50, Medium MSA Depth∼0.40 – 0.55, High MSA Depth ∼0.50 – 0.65 | Still evolving, data-dependent |

| 12 | TourSynbio[309] | 2024 | Protein sequences, textual data | Protein designs, functional annotations | InternLM2-7B[308], ProteinLM-Dataset[307] | ProteinLMBench benchmark set quieries accuracy | 62.18% | High computational requirements |

| 13 | ESM3[8] | 2024 | Sequences | Embeddings, structure | Joint Genome Institute databases[306], UniRef clusters[324], MGnify: the microbiome sequence data analysis resource[304], Observed Antibody Space[303], The Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank[302] | mean pTM41, pLDDT, backbone cRMSD42 by prompting | pTM >0.8, pLDDT >0.8, cRMSD < 1.5Å | Resource-intensive training |

| 14 | AlphaFold 3[300] | 2024 | Sequence data | Multi-protein complexes | PDB[310], Protein monomer distillation43, Disordered protein PDB distillation44, RNA distillation45, JASPAR 9[298] | DockQ score46, DockQ Score for Protein-Protein Interfaces, Predicted Local Distance Difference Test between the predicted structure with the actual structure (pLDDT), Ligand-Protein Binding Accuracy (RMSD-based), lDDT (local Distance Difference Test)47 | DockQ ∼0.7, pLDDT >70, ∼50% of ligand-protein predictions have RMSD ≤ 2Å48, ∼20% of ligand-protein predictions have RMSD < 1Å49, Protein-RNA binding lDDT ∼65%, Protein-DNA (dsDNA) binding lDDT ∼50%, RNA-only (CASP15 RNA benchmark) lDDT ∼85%, Protein-ligand binding lDDT 50-70%, RNA predictions 75-85%, DNA predictions 50-80%, Protein-protein (general) binding lDDT ∼77%, Protein-protein (antibody-involved) binding lDDT 50-60%, Protein-ligand (small molecules) lDDT 40-50% | Requires extensive computational resources |

Appendix B. Benchmarks

| Benchmark | Intended Application | Input | Performance Metric | Datasets Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASP[14] | Protein structure and folding evaluation | Protein sequences, 3D structures | predicted lDDT, lDDT50, RMSD, TM-score, Pearson correlation | Custom dataset |

| TAPE[102] | Sequence-based tasks | Protein sequences | Perplexity, Accuracy, AUPR, Precision, Spearman’s | Pfam[327] , CB513[369], CASP12, and TS115[370] |

| PEER[4] | Protein function/localization/structure prediction, protein-protein and protein-ligand interaction | Protein sequences | Accuracy, Precision, RMSE, Spearman’s | FLIP[380], Meltome atlas[371], TAPE[102], Envision[379], DeepSol[378], DeepLoc[316], ProteinNet[373], SCOP database[377], Klausen’s dataset[360], CB513[369], Guo’s yeast PPI dataset[376], Pan’s human PPI dataset[375], SKEMPI dataset[374], PDBbind-2019 dataset[372] |

| ProteinGym[2] | Fitness landscape evaluation | Protein sequences and variants | Spearman Correlation, AUC, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC)51, Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gains (NDCG)52, Top K Recall | Deep Mutational Scanning[3], ClinVar[319], FLIP[380], MaveDB[346] |

| Aviary[195] | DNA for molecular cloning, answering research questions, engineering protein stability. | Protein sequences, natural language | Accuracy | LitQA[350], HotpotQA[351], SeqQA[349], GSM8K[352] |

| ProteinLMBench[307] | Protein comprehension | Protein sequences, text pairs | Query Accuracy | ProteinLMDataset[307] |

| DeepLoc[16] | Predicting subcellular protein localization | Protein sequences | Classification Accuracy | DeepLoc dataset |

| PoseBusters[344] | Ligand-protein binding accuracy | The re-docked ligands and the true ligand(s), the protein with any cofactors | Chemical, intramolecular , intermolecular validity, the minimum heavy-atom symmetry-aware root-mean-square deviation, sequence identity, | PDB[310], The Astex Diverse set[381] |

| CAMEO[345] | Continuous protein assessment | Protein sequences, experimental 3D structures | lDDT, Contact Area Difference score (CAD-score)53, TM-score, Global Distance Test(GDT)54, MaxSub score55, Oligomeric state accuracy based on quaternary state scores (QS-score)56, reliability of local model confidence estimates (“model B-factor”)57 | PDB[310] (weekly updated) |

| PDB-Struct[217] | Structural validation | Experimental 3D structures | Clashscore58, MolProbity score59, Ramachandran plot statistics60 | PDB[310] (curated experimental structures) |

References

- Munn, D. H.; Mellor, A. L. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2007, 117, 2316–2326. [CrossRef]

- Notin, P.; Kollasch, A.; Ritter, D.; Van Niekerk, L.; Paul, S.; Spinner, H.; Rollins, N.; Shaw, A.; Orenbuch, R.; Weitzman, R. Proteingym: Large-scale benchmarks for protein fitness prediction and design. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36, .

- Hopf, T. A.; Ingraham, J. B.; Poelwijk, F. J.; Schärfe, C. P.; Springer, M.; Sander, C.; Marks, D. S. Mutation effects predicted from sequence co-variation. Nature biotechnology 2017, 35, 128–135. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, R.; Tang, J. PEER: A Comprehensive and Multi-Task Benchmark for Protein Sequence Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.02096 2022, .

- Notin, P.; Van Niekerk, L.; Kollasch, A. W.; Ritter, D.; Gal, Y.; Marks, D. S. TranceptEVE: Combining family-specific and family-agnostic models of protein sequences for improved fitness prediction. bioRxiv 2022, 2022–12.

- Laine, E.; Karami, Y.; Carbone, A. GEMME: a simple and fast global epistatic model predicting mutational effects. Molecular biology and evolution 2019, 36, 2604–2619. [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Han, C.; Zhou, Y.; Shan, J.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, F. Saprot: Protein language modeling with structure-aware vocabulary. bioRxiv 2023, 2023–10.

- Hayes, T.; Rao, R.; Akin, H.; Sofroniew, N. J.; Oktay, D.; Lin, Z.; Verkuil, R.; Tran, V. Q.; Deaton, J.; Wiggert, M.; Badkundri R. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–07. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yuan, X.; Miret, S.; Tang, J. Protst: Multi-modality learning of protein sequences and biomedical texts. International Conference on Machine Learning 2023, 38749–38767.

- Zhuo, L.; Chi, Z.; Xu, M.; Huang, H.; Zheng, H.; He, C.; Mao, X.; Zhang, W. Protllm: An interleaved protein-language llm with protein-as-word pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07920 2024, .

- Zhang, B.; Liu, K.; Zheng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Mu, J.; Wei, T.; Chen, H. Protein Language Model Supervised Scalable Approach for Diverse and Designable Protein Motif-Scaffolding with GPDL. bioRxiv 2023, 2023–10.

- Watson, J. L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N. R.; Trippe, B. L.; Yim, J.; Eisenach, H. E.; Ahern, W.; Borst, A. J.; Ragotte, R. J.; Milles, L. F.; Wicky, B.I. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100. [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R. J.; Milles, L. F.; Wicky, B. I.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R. J.; Bethel, N.; Leung P. J. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Kryshtafovych, A.; Schwede, T.; Topf, M.; Fidelis, K.; Moult, J. Critical assessment of methods of protein structure prediction (CASP)—Round XV. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2023, 91, 1539–1549. [CrossRef]

- van Kempen, M.; Kim, S. S.; Tumescheit, C.; Mirdita, M.; Gilchrist, C. L.; Söding, J.; Steinegger, M. Foldseek: fast and accurate protein structure search. Biorxiv 2022, 2022–02. [CrossRef]

- Almagro Armenteros, J. J.; Sønderby, C. K.; Sønderby, S. K.; Nielsen, H.; Winther, O. DeepLoc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using deep learning. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3387–3395. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Goetsch, L.; Dumontet, C.; Corvaïa, N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2017, 16, 315–337. [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Cai, P.; Liu, D.; Han, M.; Liu, J.; Le, Y.; Zhang, D; Hu, Q.N. High-throughput prediction of enzyme promiscuity based on substrate–product pairs. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2024, 25, bbab089. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Cen, M.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Zou, Y.; Lv, Q.; Li, S; Huang, L. Deciphering potential molecular mechanisms in clear cell renal cell carcinoma based on the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 related genes: Identifying UBE2C correlates to infiltration of regulatory T cells. BioFactors 2025, 51, e2143. [CrossRef]

- Moshawih, S.; Goh, H.P.; Kifli, N.; Idris, A.C.; Yassin, H.; Kotra, V.; Goh, K.W.; Liew, K.B; Ming, L.C. Synergy between machine learning and natural products cheminformatics: Application to the lead discovery of anthraquinone derivatives. Chemical Biology and Drug Design 2022, 99, 556–566.

- Hanahan, D; Weinberg, R.A. Weinberg Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Gogoshin, G; Rodin, A.S. Graph neural networks in cancer and oncology research: emerging and future trends. Cancers 2023, 15(24), 5858.

- Avelar, P.H.D.C; Wu, M; Tsoka, S. Incorporating Prior Knowledge in Deep Learning Models via Pathway Activity Autoencoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05813 2023 .

- Kaur, S.; Xu, K.; Saad, O. M.; Dere, R. C.; Carrasco-Triguero, M. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy: Design, mechanism, and future applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2021, 169, 34–46.

- Jain, R. K.; Stylianopoulos, T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2010, 7, 653–664. [CrossRef]

- Yingying Diao; Yan Zhao; Xinyao Li; Baoyue Li; Ran Huo; Xiaoxu Han A Simplified Machine Learning Model Utilizing Platelet-Related Genes for Predicting Poor Prognosis in Sepsis. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1286203. [CrossRef]

- Guojun Lu, W. S.; Yu Zhang Prognostic Implications and Immune Infiltration Analysis of ALDOA in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12, 721021.

- Yang, J.; Virostko, J.; Liu, J.; Jarrett, A. M.; Hormuth, D. A.; Yankeelov, T. E. Comparing mechanism-based and machine learning models for predicting the effects of glucose accessibility on tumor cell proliferation. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 10387. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Ai, S.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, S. Targeting ALDOA to Modulate Tumorigenesis and Energy Metabolism in Retinoblastoma. iScience 2024, 27, 10725. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N.; Su, J.L.; Tan, S.H.; Chen, X.L.; Cheng, T.L.; Jiang, Z.; Luo, Y.Z.; Zhang, L.M. Machine learning based on metabolomics unveils neutrophil extracellular trap-related metabolic signatures in non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing chemoimmunotherapy. World Journal of Clinical Cases 2024, 12, 4091. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Jia, H.; Jiang, N.; Zhao, J.; Nan, X. Establishment of Chemotherapy Prediction Model Based on Hypoxia-Related Genes for Oral Cancer. Journal of Cancer 2024, 15, 5191–5203. [CrossRef]

- Abriata, L.A. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry: past, present, and future of AI in biology. Communications Biology 2024, 7, Article number: 1409. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Khatib, F.; Treuille, A.; Barbero, J.; Lee, J.; Beenen, M.; Leaver-Fay, A.; Baker, D.; Popović, Z.; Players, F. Predicting protein structures with a multiplayer online game. Nature 2010, 466, 756–760. [CrossRef]

- Leaver-Fay, A.; Tyka, M.; Lewis, S. M.; Lange, O. F.; Thompson, J.; Jacak, R.; Kaufman, K. W.; Renfrew, P. D.; Smith, C. A.; Sheffler, W.; Davis, I. W.; Cooper, S.; Treuille, A.; Mandell, D. J.; Richter, F.; Ban, Y.; Fleishman, S. J.; Corn, J. E.; Kim, D. E.; Lyskov, S.; Berrondo, M.; Mentzer, S.; Popović, Z.; Havranek, J. J.; Karanicolas, J.; Das, R.; Meiler, J.; Kortemme, T.; Gray, J. J.; Kuhlman, B.; Baker, D.; Bradley, P. Rosetta3: An Object-Oriented Software Suite for the Simulation and Design of Macromolecules. Methods in Enzymology 2011, 487, 545–574.

- Arnold, F. H. Innovation by Evolution: Bringing New Chemistry to Life. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2019, 58, 14420–14426. [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Chin, M.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, W.; Mai, B.K.; Wang, H.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Y. Machine learning-guided co-optimization of fitness and diversity facilitates combinatorial library design in enzyme engineering. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6392. [CrossRef]

- Rouzbehani, R.; Kelley, S.T. AncFlow: An Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction Approach for Determining Novel Protein Structural. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-07. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Jia, H.; Jiang, N.; Zhao, J.; Nan, X. Establishment of chemotherapy prediction model based on hypoxia-related genes for oral cancer. Journal of Cancer 2024, 15(16), 5191. [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, F.; Sanchis, J.; Reetz, M. T. Learning from Protein Engineering by Deconvolution of Multi-Mutational Variants. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 63, e202404880. [CrossRef]

- Harding-Larsen, D.; Funk, J.; Madsen, N.G.; Gharabli, H.; Acevedo-Rocha, C.G.; Mazurenko, S.; Welner, D.H. Protein representations: Encoding biological information for machine learning in biocatalysis. Biotechnology Advances 2024, 108459. [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V.K.; Kumar, L.S.; Kumar, S. Enzymes. In: Chemistry of Natural Products. Springer International Publishing, 2022.

- Laurent, J. M.; Janizek, J. D.; Ruzo, M.; Hinks, M. M.; Hammerling, M. J.; Narayanan, S.; Ponnapati, M.; White, A. D.; Rodriques, S. G. Lab-bench: Measuring capabilities of language models for biology research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10362 2024, .

- Johnson, S. R.; Fu, X.; Viknander, S.; Goldin, C.; Monaco, S.; Zelezniak, A.; Yang, K. K. Computational scoring and experimental evaluation of enzymes generated by neural networks. Nature biotechnology 2024, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lipsh-Sokolik, R.; Fleishman, S. J. Addressing epistasis in the design of protein function. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2314999121. [CrossRef]

- Maynard Smith, J. Natural selection and the concept of a protein space. Nature 1970, 225, 563–564. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zou, Z.; Brooks III, C. L. Deciphering protein evolution and fitness landscapes with latent space models. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5644. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Pan, Q.; Pires, D. E. V.; Rodrigues, C. H. M.; Ascher, D. B. DDMut: predicting effects of mutations on protein stability using deep learning. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, W122-W128. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Won, M.; An, J.; Yoon, C.; Kim, D.; Lee, S. J.; Kang, H.; Kim, J. S. Advances in covalent organic frameworks for cancer phototherapy. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2024, 506, 215720. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Guan, Q.; Dong, Y. Covalent Organic Frameworks: Opportunities for Rational Materials Design in Cancer Therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 63, e202314763. [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Chen, C.; Zeng, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y. Emerging strategies in stimuli-responsive prodrug nanosystems for cancer therapy. ACS nano 2022, 16, 13513–13553. [CrossRef]

- Mizera, M.; Lewandowska, K.; Miklaszewski, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Machine Learning Approach for Determining the Formation of β-Lactam Antibiotic Complexes with Cyclodextrins Using Multispectral Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 743. [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, K. J.; Raines, R. T. Assessing and utilizing esterase specificity in antimicrobial prodrug development. Methods in enzymology 2022, 664, 199–220.

- Iyer, K. A.; Ivanov, J.; Tenchov, R.; Ralhan, K.; Rodriguez, Y.; Sasso, J. M.; Scott, S.; Zhou, Q. A. Emerging Targets and Therapeutics in Immuno-Oncology: Insights from Landscape Analysis. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2024, 67, 8519-8544. [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, M.; Lv, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, S.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Deep neural network for discovering metabolism-related biomarkers for lung adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14, 1270772. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lal, R. G.; Bowden, J. C.; Astudillo, R.; Hameedi, M. A.; Kaur, S.; Hill, M.; Yue, Y.; Arnold, F. H. Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution. bioRxiv 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Mora, A.; Li, F.Z.; Gürsoy, E.; Johnston, K.E; Arnold, F.H. LevSeq: Rapid Generation of Sequence-Function Data for Directed Evolution and Machine Learning. bioRxiv 2024, .

- Prakinee, K., Phaisan, S., Kongjaroon, S. and Chaiyen, P. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction for Designing Biocatalysts and Investigating their Functional Mechanisms. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction for Designing Biocatalysts and Synthetic Biology. JACS Au 2024, 4, 4571–4591. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Higginson, B.; Ward, T.R. Creation and optimization of artificial metalloenzymes: Harnessing the power of directed evolution and beyond. Chem 2024, 10, 2373-2389. [CrossRef]

- Esteves, F., Rueff, J. and Kranendonk, M., 2021. The central role of cytochrome P450 in xenobiotic metabolism—a brief review on a fascinating enzyme family. Journal of Xenobiotics 2024, 11, pp.94-114. [CrossRef]

- Bundit Boonyarit, N. Y. GraphEGFR: Multi-task and transfer learning based on molecular graph attention mechanism and fingerprints improving inhibitor bioactivity prediction for EGFR family proteins on data scarcity. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2024, 45, Pages. [CrossRef]

- Ai, D., Cai, H., Wei, J., Zhao, D., Chen, Y. and Wang, L., 2023. DEEPCYPs: A deep learning platform for enhanced cytochrome P450 activity prediction. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1099093. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Tang, Y.; Gong, C.; Huang, Z.; Feng Y.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Li, W. Prediction of Cytochrome P450 Substrates Using the Explainable Multitask Deep Learning Models. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2024, 37, . [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, Z.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Li, W. Machine Learning Models to Predict Cytochrome P450 2B6 Inhibitors and Substrates. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2023, 36, . [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F.; Hu, P.; Gao, Y.; Bai, X.; Peng, S.; Ren, C.; Xu, X.; Liu, Z. CGMega: explainable graph neural network framework with attention mechanisms for cancer gene module dissection. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 5997. [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Pacheco, S.E.; Mueller, A.; Puente-Pineda, J.A.; Zúñiga-Miranda, J.; Guamán, L.P. Designing Cytochrome P450 Enzymes for Use in Cancer Gene Therapy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Mutti, P.; Lio, F.; Hollfelder, F. Microdroplet screening rapidly profiles a biocatalyst to illuminate functional sequence space. bioRxiv 2024, .

- Xing Wan, S. S. Discovery of alkaline laccases from basidiomycete fungi through machine learning-base approach. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 2024, 17, . [CrossRef]

- Changda Gong; Yanjun Feng; Jieyu Zhu; Guixia Liu; Yun Tang; Weihua Li Evaluation of Machine Learning Models for Cytochrome P450 Inhibition Prediction. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2024, 44, .

- Xin-Man Hu; Yan-Yao Hou; Xin-Ru Teng; Yong Liu; Yu Li; Wei Li; Yan Li; Chun-Zhi Ai Prediction of Cytochrome P450-Mediated Bioactivation Using Machine Learning Models and In Vitro Validation. Archives of Toxicology 2024, 98, .

- Kao, D. Prediction of Cytochrome P450-Related Drug-Drug Interactions by Deep Learning. 2022, .

- López-Vidal, E. M.; Schissel, C. K.; Mohapatra, S.; Bellovoda, K.; Wu, C.; Wood, J. A.; Malmberg, A. B.; Loas, A.; Gómez-Bombarelli, R.; Pentelute, B. L. Deep Learning Enables Discovery of a Short Nuclear Targeting Peptide for Efficient Delivery of Antisense Oligomers. JACS Au 2021, 1, 1751–1761. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Huo, M.; Liu, X.; Li, S. C. Biomarkers and computational models for predicting efficacy to tumor ICI immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1368749. [CrossRef]

- Iacobini, C.; Vitale, M.; Pugliese, G.; Menini, S. The “sweet” path to cancer: focus on cellular glucose metabolism. Frontiers in Oncology, 13, p.1202093. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, 13, 1202093. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wu, M.; Liu, Q.; Lv, H.; Jiang, R. DeepHistone: a deep learning approach to predicting histone modifications. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 193. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, Z.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Li, W. Machine Learning Models to Predict Cytochrome P450 2B6 Inhibitors and Substrates. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2023, 36, 1227–1236. [CrossRef]

- Neelakandan A. R.; Rajanikant G. K. A deep learning and docking simulation-based virtual screening strategy enables the rapid identification of HIF-1α pathway activators from a marine natural product database. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2024, 42, 629–651.

- Kim, J. H.; Lee, W. S.; Lee, H. J.; Yang, H.; Lee, S. J.; Kong, S. J.; Je, S.; Yang, H.; Jung, J.; Cheon, J.; Kang, B. Deep learning model enables the discovery of a novel immunotherapeutic agent regulating the kynurenine pathway. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 2005280. [CrossRef]

- Boush, M.; Kiaei, A. A.; Mahboubi, H. Trending Drugs Combination to Target Leukemia-associated Proteins/Genes: Using Graph Neural Networks under the RAIN Protocol. medRxiv 2023, 2023–08.

- Liu, X.; Hu, W.; Diao, S.; Abera, D.E.; Racoceanu, D.; Qin, W. Multi-scale feature fusion for prediction of IDH1 mutations in glioma histopathological images. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2024, 248, 108116. [CrossRef]

- Cong, C.; Xuan, S.; Liu, S.; Pagnucco, M.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y. Dataset Distillation for Histopathology Image Classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09709 2024.

- Fang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Cai, C.; Lin, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Shen, H. Deep Learning Predicts Biomarker Status and Discovers Related Histomorphology Characteristics for Low-Grade Glioma. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07464 2023, 15, .

- Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, D.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Chen, L. The regulatory mechanisms and inhibitors of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 in cancer. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2023, 13, 1438–1466.

- Sonowal, S., Pathak, K., Das, D., Buragohain, K., Gogoi, A., Borah, N., Das, A. and Nath, R. L-Asparaginase Bio-Betters: Insight Into Current Formulations, Optimization Strategies and Future Bioengineering Frontiers in Anti-Cancer Drug Development. Advanced Therapeutics 2024, 7, 2400156. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, Q.; Yu, X.; Huang, M.; Ding, M.; Li, W.; Tang, Y.; Liu, G. Prediction of IDO1 Inhibitors by a Fingerprint-Based Stacking Ensemble Model Named IDO1Stack. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202300151. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Ji, Y.; Guo, Y.; Duan, J.; Liu, X.; Yan, D.; Liang, D.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z. Computational Pathology for Prediction of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Gene Mutation from Whole Slide Images in Adult Patients with Diffuse Glioma. The American Journal of Pathology 2024, 194, 747–758. [CrossRef]

- Redlich, J.; Feuerhake, F.; Weis, J.; Schaadt, N. S.; Teuber-Hanselmann, S.; Buck, C.; Luttmann, S.; Eberle, A.; Nikolin, S.; Appenzeller, A.; Portmann, A.; Homeyer, A. Applications of artificial intelligence in the analysis of histopathology images of gliomas: a review. npj Imaging 2024.

- Lv, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, M. Insight into deep learning for glioma IDH medical image analysis: A systematic review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37150.

- Fang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Cai, C.; Lin, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Shen, H.; Tan, J.; Zhang, Y. Deep learning predicts biomarker status and discovers related histomorphology characteristics for low-grade glioma. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07464 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cong, C.; Xuan, S.; Liu, S.; Pagnucco, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y. Dataset distillation for histopathology image classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09709 2024. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xu, P.; Wu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Han, C.; Lin, J.; Zhao, K.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Lu, C. CroMAM: A Cross-Magnification Attention Feature Fusion Model for Predicting Genetic Status and Survival of Gliomas using Histological Images. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Iwamoto, Y.; Chen, Y.W. IDH mutation status prediction by a radiomics associated modality attention network. Visual Computer 2023, 39, 2367–2379. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zanazzi G. J.; Hassanpour, S. Predicting prognosis and IDH mutation status for patients with lower-grade gliomas using whole slide images. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 16849. [CrossRef]

- Basak, K.; Ozyoruk, K.B.; Demir, D. Whole Slide Images in Artificial Intelligence Applications in Digital Pathology: Challenges and Pitfalls. Turkish Journal of Pathology 2023, 39, 101–108.

- Notin, P.; Dias, M.; Frazer, J.; Marchena-Hurtado, J.; Gomez, A.N.; Marks, D.;Gal, Y. Tranception: protein fitness prediction with autoregressive transformers and inference-time retrieval. ArXiv 2022, abs/2205.13760, .

- Bozkurt, E. U.; rsted, E. C.; Volke, D. C.; Nikel, P. I. Accelerating enzyme discovery and engineering with high-throughput screening. Natural Product Reports 2025, .

- Lu, M. Y.; Williamson, D. F. K.; Chen, T. Y.; Mahmood, F. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2021, 5, 555–570.

- Shao, Z.; Bian, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y. TransMIL: Transformer Based Correlated Multiple Instance Learning for Whole Slide Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2021, 2136–2147.

- Khorsandi, D.; Rezayat, D.; Sezen, S.; Ferrao, R.; Khosravi, A.; Zarepour, A.; Khorsandi, M.; Hashemian, M.; Iravani, S.; Zarrabi, A. Application of 3D, 4D, 5D, and 6D Bioprinting in Cancer Research: What Does the Future Look Like?. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2024, Issue 19, .

- Laury, A.R.; Zheng, S.; Aho, N.; Fallegger, R.; Hänninen, S.; Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Tanevski, J.; Youssef, O.; Tang, J.; Carpén, O.M. Opening the Black Box: Spatial Transcriptomics and the Relevance of Artificial Intelligence–Detected Prognostic Regions in High-Grade Serous Carcinoma. Modern Pathology 2024, 37, 100508. [CrossRef]

- Nogales, J. M. S.; Parras, J.; Zazo, S. DDQN-based optimal targeted therapy with reversible inhibitors to combat the Warburg effect. Mathematical Biosciences 2023, 363, 109044.

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; dos Santos Costa, A.; Fazel-Zarandi, M.; Sercu, T.; Candido, S.; Rives, A. Language models of protein sequences at the scale of evolution enable accurate structure prediction. BioRxiv 2022, 2022, 500902.

- Rao, R.; Bhattacharya, N.; Thomas, N.; Duan, Y; Chen, P; Canny, J; Abbeel, P; Song, Y. TAPE: A Benchmark for Transformer-Based Models of Protein Sequences. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.11803 2020, .

- Hie, B.L.; Yang, K.K; Kim, P.S. Evolutionary velocity with protein language models predicts evolutionary dynamics of diverse proteins. Cell Systems 2022, 13, 274–285. [CrossRef]

- Howard H.R. Using Machine Vision of Glycolytic Elements to Predict Breast Cancer Recurrences: Design and Implementation. Metabolites 2023, 13, 41.

- Brouwer, B.; Della-Felice, F.; Illies, J.H.; Iglesias-Moncayo, E.; Roelfes, G.; Drienovská, I. Noncanonical Amino Acids: Bringing New-to-Nature Functionalities to Biocatalysis. Chemical Reviews 2024, 124, XX. [CrossRef]

- Moon, H. H.; Jeong, J.; Park, J. E.; Kim, N.; Choi, C.; Kim, Y.; Song, S. W.; Hong, C.; Kim, J. H.; Kim, H. S. Generative AI in glioma: Ensuring diversity in training image phenotypes to improve diagnostic performance for IDH mutation prediction. Neuro-Oncology 2024, 26, 1124-1135. [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, M., Chaudhry, N. and Choudhary, R. Classification of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH) Mutation Status in Gliomas Using Transfer Learning. Pakistan Journal of Scientific Research 2024, 3, 224–233. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Iwamoto, Y.; Cheng, J.; Bai, J.; Zhao, G.; Han, X. Chen, Y. W. IDH mutation status prediction by a radiomics associated modality attention network. The Visual Computer 2023, 39(6), 2367–2379.

- Krebs, O.; Agarwal, S.; Tiwari, P. Self-supervised deep learning to predict molecular markers from routine histopathology slides for high-grade glioma tumors. Medical Imaging 2023: Digital and Computational Pathology 2023, 12471, 1247102.

- Wang, Y.; Xue, P.; Cao, M.; Yu, T.; Lane, S. T.; Zhao, H. Directed evolution: methodologies and applications. Chemical reviews 2021, 121, 12384–12444.

- Alzaeemi, S. A.; Noman, E. A.; Al-shaibani, M. M.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Mohamed, R. M. S. R.; Almoheer, R.; Seif, M.; Tay, K. G.; Zin, N. M.; El Enshasy, H. A. Improvement of L-asparaginase, an Anticancer Agent of Aspergillus arenarioides EAN603 in Submerged Fermentation Using a Radial Basis Function Neural Network with a Specific Genetic Algorithm (RBFNN-GA). Fermentation 2023, 9, . [CrossRef]

- Madani, A.; McCann, B.; Naik, N.; Keskar, N.S.; Anand, N.; Eguchi, R.R.; Huang, P.S.; Socher, R. ProGen: Language Modeling for Protein Generation. bioRxiv 2020, .

- Xu, G.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xia, X.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J. OPUS-GO: An interpretable protein/RNA sequence annotation framework based on biological language model. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–12.

- Safari, M.; Beiki, M.; Ameri, A.; Toudeshki, S.H.; Fatemi, A.; Archambault, L. Shuffle-ResNet: Deep learning for predicting LGG IDH1 mutation from multicenter anatomical MRI sequences. Biomedical Physics and Engineering Express 2022, 8, 065036. [CrossRef]

- Goldwaser, E.; Laurent, C.; Lagarde, N.; Fabrega, S.; Nay, L.; Villoutreix, B.O.; Jelsch, C.; Nicot, A.B.; Loriot, M.A; Miteva, M.A. Machine learning-driven identification of drugs inhibiting cytochrome P450 2C9. PLOS Computational Biology 2022, 18, e1009820. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M.; He, L.; Yu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Shen, J.; Lu, B. Machine learning-based cell death marker for predicting prognosis and identifying tumor immune microenvironment in prostate cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37554. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lisanza, S.; Juergens, D.; Tischer, D.; Watson, J.L.; Castro, K.M.; Ragotte, R.; Saragovi, A.; Milles, L.F.; Baek, M.; Anishchenko, I. Scaffolding protein functional sites using deep learning. Science 2022, 377, 387–394. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Du, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Rao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, K. The deubiquitinating enzymes-related signature predicts the prognosis and immunotherapy response in breast cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 11553–11567. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, P. Deep learning for computational biology. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 1–16.

- Li, Y.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Li, M. DeepCellEss: cell line-specific essential protein prediction with attention-based interpretable deep learning. Bioinformatics 2022, 39, btac779. [CrossRef]

- Corpas, F. J.; Barroso, J. B.; Sandalio, L. M.; Palma, J. M.; Lupiánez, J. A.; del Rıo, L. A. Peroxisomal NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase. Characterization and activity regulation during natural senescence. Plant Physiology 1999, 121, 921–928.

- Li, X.; Strasser, B.; Neuberger, U.; Vollmuth, P.; Bendszus, M.; Wick, W.; Dietrich, J.; Batchelor, T. T.; Cahill, D. P.; Andronesi, O. C. Deep learning super-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of brain metabolism and mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase glioma. Neuro-Oncology Advances 2022, 4, vdac071.

- Tang, W.T.; Su, C.Q.; Lin, J.; Xia, Z.W.; Lu, S.S; Hong, X.N. T2-FLAIR mismatch sign and machine learning-based multiparametric MRI radiomics in predicting IDH mutant 1p/19q non-co-deleted diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Clinical Radiology 2024, 79, e750–e758.

- Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Z.; Feng, W.; Hu, Y.; Ni, J.; Yao, F.; Zhou, G.; Wan, C.; Zhang, X. Deep-learning and conventional radiomics to predict IDH genotyping status based on magnetic resonance imaging data in adult diffuse glioma. Frontiers in Oncology 2023, 13, 1143688.

- Nakagaki, R.; Debsarkar, S.S.; Kawanaka, H.; Aronow, B.J.; Prasath, V.S. Deep learning-based IDH1 gene mutation prediction using histopathological imaging and clinical data. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 179, 108902.

- Lee, S.H.; Jang, H.J. Deep learning-based prediction of molecular cancer biomarkers from tissue slides: A new tool for precision oncology. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology 2022, 28, 754–772. [CrossRef]

- Sharrock, A.V.; Mumm, J.S.; Williams, E.M.; Čėnas, N.; Smaill, J.B.; Patterson, A.V.; Ackerley, D.F.; Bagdžiūnas, G.; Arcus, V.L. Structural Evaluation of a Nitroreductase Engineered for Improved Activation of the 5-Nitroimidazole PET Probe SN33623. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 6593.

- Levinthal, C. Are there pathways for protein folding?Journal de Chimie Physique 1968, 65, 44–45. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; McLeod, H.L. Strategies for enzyme/prodrug cancer therapy. Clinical Cancer Research 2001, 7, 3314–3324.

- Kim, G. B.; Kim, J. Y.; Lee, J. A.; Norsigian, C. J.; Palsson, B. O.; Lee, S. Y. Functional annotation of enzyme-encoding genes using deep learning with transformer layers. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7370. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Pranaw, K.; Tiwari, R.; Khare, S. K. Recent development in the uses of asparaginase as food enzyme. Green bio-processes: enzymes in industrial food processing 2019, 55–81.

- Buller, R.; Lutz, S.; Kazlauskas, R.; Snajdrova, R.; Moore, J.; Bornscheuer, U. From nature to industry: Harnessing enzymes for biocatalysis. Science 2023, 382, eadh8615. [CrossRef]

- Reetz, M. T.; Qu, G.; Sun, Z. Engineered enzymes for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and other high-value products. Nature Synthesis 2024, 3, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Deng, H.; He, J.; Keasling, J. D.; Luo, X. UniKP: a unified framework for the prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters. Nature communications 2023, 14, 8211.

- Ge, F.; Chen, G.; Qian, M.; Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Hu, D.; Xu, Y.; Xin, Y.; Wang, D. Artificial intelligence aided lipase production and engineering for enzymatic performance improvement. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 71, 14911–14930.

- Yang, R.; Zha, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Cheng, B.; Yan, B. Multi-stage virtual screening of natural products against p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase: Predictive modeling by machine learning, docking study, and molecular dynamics simulation. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10495.

- Kumar, S.; Boehm, J.; Lee, J. C. p38 MAP kinases: key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2003, 2, 717–726.

- Kumar, M.; Anand, S.; Jha, R. K.; Singh, A. Neural Network-Based L-Asparaginase Production Using Acinetobacter baumannii from Pectic Waste: Process Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2016, 7, 173–180.

- Wilkinson, S. P.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. Bioinformatic Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of L-Asparaginase Enzymes with Antitumor Properties. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 4567.

- Smith, J.; Patel, R.; Kim, E. Machine Learning-Assisted Screening of L-Asparaginase Variants for Enhanced Stability and Activity. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2023, 104, 107080.

- Ramirez, D. L.; Hernandez, J. M.; Lopez, M. C. A Novel L-Asparaginase from Thermophilic Bacteria: Biochemical Characterization and Potential Biotechnological Applications. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic 2021, 180, 105640.

- Jain, P.; Das, S.; Ghosh, K. Deep Learning for Predicting Catalytic Residues in L-Asparaginase Enzymes. BMC Bioinformatics 2024, 25, 89.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J. Enhanced L-Asparaginase Activity through Directed Evolution and Computational Design. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 2020, 33, 145–152.

- Park, H. J.; Choi, S. W.; Kang, M. J. Cryo-EM Analysis of L-Asparaginase Complex Reveals Molecular Mechanism of Substrate Recognition. Structure 2019, 27, 1023–1031.

- Tanaka, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Ito, A. Synthetic Biology Approaches to Engineer L-Asparaginase for Tailored Therapeutic Applications. Biotechnology Advances 2023, 65, 108068.

- Munn, D. H.; Sharma, M. D.; Baban, B.; Harding, H. P.; Zhang, Y.; Ron, D.; Mellor, A. L. GCN2 kinase in T cells mediates proliferative arrest and anergy induction in response to indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase. Immunity 2005, 22, 633–642. [CrossRef]

- Muller, A. J.; Manfredi, M. G.; Zakharia, Y.; Prendergast, G. C. Inhibiting IDO pathways to treat cancer: lessons from the ECHO-301 trial and beyond. Seminars in Immunopathology 2019, 41, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. S.; Mcgaha, T.; Munn, D. H. Chemo-immunotherapy: role of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase in defining immunogenic versus tolerogenic cell death in the tumor microenvironment. Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Cancer Progression and Cancer Therapy 2017, 91–104.

- Munn, D. H.; Mellor, A. L. Indoleamine 2, 3 dioxygenase and metabolic control of immune responses. Trends in Immunology 2013, 34, 137–143.

- Niu, B.; Lee, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Johnson, J. The Accurate Prediction of Antibody Deamidations by Combining High-Throughput Automated Peptide Mapping and Protein Language Model-Based Deep Learning. Antibodies 2024, 13, 74.

- Hua, C.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, O.; Tang, J.; Ying, R.; Jin, W.; Wolf, G.; Precup, D.; Zheng, S. Reaction-conditioned De Novo Enzyme Design with GENzyme. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.16694 2024, .

- Wen, Y.; Liu, H.; Cao, C.; Wu, R. Applications of protein engineering in the pharmaceutical industry. Synthetic Biology Journal 2024, 1.

- Yan, Y.; Shi, Z.; Wei, H. ROSes-FINDER: a multi-task deep learning framework for accurate prediction of microorganism reactive oxygen species scavenging enzymes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1245805. [CrossRef]

- Nijkamp, E.; Ruffolo, J. A.; Weinstein, E. N.; Naik, N.; Madani, A. Progen2: exploring the boundaries of protein language models. Cell Systems 2023, 14, 968–978. [CrossRef]

- Hager, P.; Jungmann, F.; Holland, R.; Bhagat, K.; Hubrecht, I.; Knauer, M.; Vielhauer, J.; Makowski, M.; Braren, R.; Kaissis, G.; Rueckert, D., Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 2613–2622. [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, A. J.; Ting, D. S. J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T. F.; Ting, D. S. W. Large language models in medicine. Nature Medicine 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T. B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 2020, .

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D. d. L.; Hendricks, L. A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; Hennigan, T.Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.15556 2022, .

- Huang, C.; Zhang, L.; Tang, T.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhang, W.; Jia, X.; You, S. Application of Directed Evolution and Machine Learning to Enhance the Diastereoselectivity of Ketoreductase for Dihydrotetrabenazine Synthesis. JACS Au 2024, 4, 2547–2556.

- López-Cortés, A.; Cabrera-Andrade, A.; Echeverría-Garcés, G.; Echeverría-Espinoza, P.; Pineda-Albán, M.; Elsitdie, N.; Bueno-Miño, J.; Cruz-Segundo, C. M.; Dorado, J.; Pazos, A.; Gonzáles-Díaz, H. Unraveling druggable cancer-driving proteins and targeted drugs using artificial intelligence and multi-omics analyses. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 19359. [CrossRef]

- Giurini, E. F.; Godla, A.; Gupta, K. H. Redefining bioactive small molecules from microbial metabolites as revolutionary anticancer agents. Cancer Gene Therapy 2024, 31, 187–206. [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Kiaei, A. A.; Boush, M.; Aghaei, F. Emerging Drug Combinations for Targeting Tongue Neoplasms Associated Proteins/Genes: Employing Graph Neural Networks within the RAIN Protocol. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–06.

- Dashti, N.; Kiaei, A. A.; Boush, M.; Gholami-Borujeni, B.; Nazari, A. AI-Enhanced RAIN Protocol: A Systematic Approach to Optimize Drug Combinations for Rectal Neoplasm Treatment. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–05.

- Sadeghi, S.; Kiaei, A. A.; Boush, M.; Salari, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Safaei, D.; Mahboubi, M.; Tajfam, A.; Moghadam, S. A graphSAGE discovers synergistic combinations of Gefitinib, paclitaxel, and Icotinib for Lung adenocarcinoma management by targeting human genes and proteins: the RAIN protocol. medRxiv 2024, 2024–04.

- Yang, L.; Lei, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z.L. Rising above: exploring the therapeutic potential of natural product-based compounds in human cancer treatment. Tradit Med Res 2025, 10, 18. [CrossRef]

- Harding-Larsen, D.; Funk, J.; Madsen, N. G.; Gharabli, H.; Acevedo-Rocha, C. G.; Mazurenko, S.; Welner, D. H. Protein representations: Encoding biological information for machine learning in biocatalysis. Biotechnology Advances 2024, 108459. [CrossRef]

- Jelassi, S.; Brandfonbrener, D.; Kakade, S. M.; Malach, E. Repeat after me: Transformers are better than state space models at copying. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01032 2024, .

- Pleiss, J. Modeling Enzyme Kinetics: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives for Biocatalysis. Biochemistry 2024, 63, 2533–2541.

- Felix A. Döppel; Martin Votsmeier. Robust mechanism discovery with atom conserving chemical reaction neural networks. In Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2024, 40, 105507.

- Grauman, Å.; Ancillotti, M.; Veldwijk, J.; Mascalzoni, D. Precision cancer medicine and the doctor-patient relationship: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2023, 23, 286. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, T. Unraveling the Double-Edged Sword Effect of AI Transparency on Algorithmic Acceptance. 2024, .

- Xie, W. J.; Warshel, A. Harnessing generative AI to decode enzyme catalysis and evolution for enhanced engineering. National Science Review 2023, 10, nwad331. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lee, H. Expanding functional protein sequence spaces using generative adversarial networks. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2188.

- Ahmed, Y. B.; Al-Bzour, A. N.; Ababneh, O. E.; Abushukair, H. M.; Saeed, A. Genomic and Transcriptomic Predictors of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma Patients: A Machine Learning Approach. Cancers 2022, 14, 5605. [CrossRef]

- Emran, T.B.; Shahriar, A.; Mahmud, A.R.; Rahman, T.; Abir, M.H.; Siddiquee, M.F.R.; Ahmed, H.; Rahman, N.; Nainu, F.; Wahyudin, E.; Mitra, S. Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms, Immunoprevention, and Therapeutic Approaches. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 891652.

- Martin Alonso, M. C.; Alamdari, S.; Samad, T. S.; Yang, K. K.; Bhatia, S. N.; Amini, A. P. Deep learning guided design of protease substrates. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–02.

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Huang, W. Nanoparticulation of Prodrug into Medicines for Cancer Therapy. Advanced Science 2021, . [CrossRef]

- Bannigan, P.; Bao, Z.; Hickman, R. J.; Aldeghi, M.; Häse, F.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Allen, C. Machine learning models to accelerate the design of polymeric long-acting injectables. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 35. [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F. P.; Waxman, D. J.; Mishra, A.; Zhao, X. Designing Cytochrome P450 Enzymes for Use in Cancer Gene Therapy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, 12, 1405466. [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.; Gosu, V.; Tripathi, T.; Saudagar, P. Molecular Dynamics Simulation to Study Protein Conformation and Ligand Interaction. Protein Folding Dynamics and Stability: Experimental and Computational Methods 2023, 107–127.

- Tandel, G. S.; Biswas, M.; Kakde, O. G.; Tiwari, A.; Suri, H. S.; Turk, M.; Laird, J. R.; Asare, C. K.; Ankrah, A. A.; Khanna, N.; Madhusudhan, B.K. A review on a deep learning perspective in brain cancer classification. Cancers 2019, 11, 111. [CrossRef]

- Nicolás Lefin; Javiera Miranda; Jorge F. Beltrán; Lisandra Herrera Belén; Brian Effer; Adalberto Pessoa Jr; Jorge G. Farias; Zamorano, M. Current state of molecular and metabolic strategies for the improvement of L-asparaginase expression in heterologous systems. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1208277.

- Callaghan, R., Luk, F. and Bebawy, M. Inhibition of the Multidrug Resistance P-Glycoprotein: Time for a Change of Strategy?. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2014, 42, 623–631.

- Wang, X., Zhang, H. and Chen, X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist 2019, 2, 141–160.

- Yi, M.; Jiao, D.; Qin, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K.; Li, A. Synergistic effect of immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Molecular Cancer 2019, 18, 1-12.

- Jennings, M.R.; Munn, D; Blazeck, J. Immunosuppressive metabolites in tumoral immune evasion: redundancies, clinical efforts, and pathways forward. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2021, 9, e003013.

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. G.; Shen, Y. Validation of an LLM-based Multi-Agent Framework for Protein Engineering in Dry Lab and Wet Lab. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.06029 2024, .

- Shen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Mamalakis, M.; He, L.; Xia, H.; Li, T.; Su, Y.; He, J.; Wang, Y. G. A Fine-tuning Dataset and Benchmark for Large Language Models for Protein Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) 2024, 2390–2395.

- Pecher, B.; Srba, I.; Bielikova, M. A survey on stability of learning with limited labelled data and its sensitivity to the effects of randomness. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 57, 1–40.

- Kim, S.; Schrier, J.; Jung, Y. Explainable Synthesizability Prediction of Inorganic Crystal Structures using Large Language Models. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 64, e202423950. [CrossRef]

- Van Herck, J.; Gil, M. V.; Jablonka, K. M.; Abrudan, A.; Anker, A. S.; Asgari, M.; Blaiszik, B.; Buffo, A.; Choudhury, L.; Corminboeuf, C.; Daglar, H. Assessment of fine-tuned large language models for real-world chemistry and material science applications . Chemical Science 2025, 16, 670–684. [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Mindermann, S.; Privitera, D.; Besiroglu, T.; Bommasani, R.; Casper, S.; Choi, Y.; Goldfarb, D.; Heidari, H.; Khalatbari, L.; Longpre, S. International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI (Interim Report). arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.05282 2024 .

- Sarumi, O. A.; Heider, D. Large language models and their applications in bioinformatics. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2024.

- Yan, K.; Tang, Z. When General-Purpose Large Language Models Meet Bioinformatics. In CS582 ML for bioinformatics workshop , .

- Narayanan, S.; Braza, J. D.; Griffiths, R.; Ponnapati, M.; Bou, A.; Laurent, J.; Kabeli, O.; Wellawatte, G.; Cox, S.; Rodriques, S. G.; White, A.D. Aviary: training language agents on challenging scientific tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.21154 2024, .

- Brueggemeier, R. W.; Hackett, J. C.; Diaz-Cruz, E. S. Aromatase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Endocrine Reviews 2005, 26, 331-345. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhong, T.; Yu, X. Deep learning methods for protein structure prediction. MedComm–Future Medicine 2024, 3, e96. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, J.; Deng, M.; Lai, L. Hierarchical graph transformer with contrastive learning for protein function prediction. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad410. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Dalal, K.; Xu, J.; Vikram, A.; Zhang, G.; Dubois, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Koyejo, S.; Hashimoto, T. Learning to (learn at test time): Rnns with expressive hidden states. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.04620 2024, .

- Elnaggar, A.; Heinzinger, M.; Dallago, C.; Rehawi, G.; Wang, Y.; Jones, L.; Gibbs, T.; Feher, T.; Angerer, C.; Steinegger, M.; Bhowmik, D. Prottrans: Toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44, 7112–7127. [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., Cui, H., Li, J.C., Luo, Y., Jiang, G. and Zhao, H. Enzyme function prediction using contrastive learning. Science 2023, 379, xx–xx. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, P.; Fernandes, P. Machine Learning: A Suitable Method for Biocatalysis. Catalysts 2023, 13, 961. [CrossRef]

- Trippe, B. L.; Yim, J.; Tischer, D.; Baker, D.; Broderick, T.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. Diffusion probabilistic modeling of protein backbones in 3d for the motif-scaffolding problem. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.04119 2022, .

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Zidek, A.; Potapenko, A.; others Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589.

- Ferruz, N.; Schmidt, S.; Höcker, B. ProtGPT2 is a deep unsupervised language model for protein design. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 4348.

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; Bodenstein, S.W. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500.

- Ryu, J. Y.; Kim, H. U.; Lee, S. Y. Deep learning enables high-quality and high-throughput prediction of enzyme commission numbers. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 13996–14001.

- Ma, B.; Kumar, S.; Tsai, C.; Hu, Z.; Nussinov, R. Transition-state ensemble in enzyme catalysis: possibility, reality, or necessity? Journal of theoretical biology 2000, 203, 383–397.

- Guengerich, F.P. Roles of Individual Human Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Drug Metabolism. Pharmacological Reviews 2024, 76, 1104–1132.

- Huang, Y. J.; Mao, B.; Aramini, J. M.; Montelione, G. T. Assessment of template-based protein structure predictions in CASP10. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2014, 82, 43–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Skolnick, J. Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2004, 57, 702–710. [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.; Wang, Z.; Qin, P. pLDDT-Predictor: High-speed Protein Screening Using Transformer and ESM2. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.21283 2024 .

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhong, B.; Liu, K.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J.; Wei, T.; Chen, H. Scaffold-Lab: Critical Evaluation and Ranking of Protein Backbone Generation Methods in A Unified Framework. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–02. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Ding, F.; Wang, R.; Shen, R.; Zhang, X.; Luo, S.; Su, C.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Berger, B.; Ma, J. High-resolution de novo structure prediction from primary sequence. BioRxiv 2022, 2022–07.

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; Smetanin, N.; Verkuil, R.; Kabeli, O.; Shmueli, Y.; others Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. Advanced strategies of enzyme activity regulation for biomedical applications. ChemBioChem 2022, 23, e202200358.

- Wang, C.; Zhong, B.; Zhang, Z.; Chaudhary, N.; Misra, S.; Tang, J. PDB-Struct: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Structure-based Protein Design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00080 2023, .

- Edmunds, N. S.; Genc, A. G.; McGuffin, L. J. Benchmarking of AlphaFold2 accuracy self-estimates as indicators of empirical model quality and ranking: a comparison with independent model quality assessment programmes. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae491.

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, W.X.; Liu, Q.; Zitnik, M. Efficient Generation of Protein Pockets with PocketGen. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 1–14.

- Hayes, T.; Rao, R.; Akin, H.; Sofroniew, N. J.; Oktay, D.; Lin, Z.; Verkuil, R.; Tran, V. Q.; Deaton, J.; Wiggert, M.; Badkundri, R. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. Science 2025, eads0018. [CrossRef]

- Zambaldi, V.; La, D.; Chu, A. E.; Patani, H.; Danson, A. E.; Kwan, T. O.; Frerix, T.; Schneider, R. G.; Saxton, D.; Thillaisundaram, A.; Wu, Z. De novo design of high-affinity protein binders with AlphaProteo. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.08022 2024.

- Qiu, J.; Li, L.; Sun, J.; Peng, J.; Shi, P.; Zhang, R.; Dong, Y.; Lam, K.; Lo, F. P.; Xiao, B.; Yuan, W. Large ai models in health informatics: Applications, challenges, and the future. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023, 27, 6074–6087. [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, A.; Essam, H.; Salah-Eldin, W.; Moustafa, W.; Elkerdawy, M.; Rochereau, C.; Rost, B. Ankh: Optimized protein language model unlocks general-purpose modelling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.06568 2023.

- Chen, B.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Geng, Y.; Gong, J.; Li, S.; Bei, Z.; Tan, X.; Wang, B.; Zeng, X.; Liu, C. xTrimoPGLM: unified 100B-scale pre-trained transformer for deciphering the language of protein. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.06199 2024.

- Song, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y. Accurately predicting enzyme functions through geometric graph learning on ESMFold-predicted structures. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 8180. [CrossRef]

- Bushuiev, A.; Bushuiev, R.; Zadorozhny, N.; Samusevich, R.; Stärk, H.; Sedlar, J.; Pluskal, T.; Sivic, J. Training on test proteins improves fitness, structure, and function prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.02109 2024, .

- Gantz, M.; Mathis, S.V.; Nintzel, F.E.; Zurek, P.J.; Knaus, T.; Patel, E.; Boros, D.; Weberling, F.M.; Kenneth, M.R.; Klein, O.J.; Medcalf, E.J. Microdroplet Screening Rapidly Profiles a Biocatalyst to Enable Its AI-Guided Engineering. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–04.

- Son, A.; Park, J.; Kim, W.; Lee, W.; Yoon, Y.; Ji, J.; Kim, H. Integrating Computational Design and Experimental Approaches for Next-Generation Biologics. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1073. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Machine learning-assisted amidase-catalytic enantioselectivity prediction and its application in biocatalyst engineering. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6392.

- Hollmann, F.; Sanchis, J.; Reetz, M. T. Learning from Protein Engineering by Deconvolution of Multi-Mutational Variants. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, .

- Menke, M. J.; Ao, Y.; Bornscheuer, U. T. Practical Machine Learning-Assisted Design Protocol for Protein Engineering: Transaminase Engineering for the Conversion of Bulky Substrates. ACS Catalysis 2024, .

- Zhou, J.; Huang, M. Navigating the landscape of enzyme design: from molecular simulations to machine learning. Chemical Society Reviews 2024, 53, 8202–8239. [CrossRef]

- Paton, A.; Boiko, D.; Perkins, J.; Cemalovic, N.; Reschützegger, T.; Gomes, G.; Narayan, A. Generation of Connections Between Protein Sequence Space and Chemical Space to Enable a Predictive Model for Biocatalysis. ChemRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Joon, P.; Kadian, M.; Dahiya, M.; Sharma, G.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, A.; Parle, M. Prognosticating Drug Targets and Responses by Analyzing Metastasis-Related Cancer Pathways. Handbook of Oncobiology: From Basic to Clinical Sciences 2023, 1–25.

- Sorrentino, C.; Ciummo, S. L.; Fieni, C.; Di Carlo, E. Nanomedicine for cancer patient-centered care. MedComm 2024, 5, e767.

- Guo, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Yi, Y. Multistage self-assembled nanomaterials for cancer immunotherapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 7750. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Yin, J.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Chai, X.; Niu, T.; Zeng, S.; Jia, Q. INTEDE 2.0: the metabolic roadmap of drugs. Nucleic acids research 2024, 52, D1355–D1364. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, F.; Zhou, Y.; Mou, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, K.; Xue, J.; Luo, Y.; Fu, J.; He, X.; Gao, J. INTEDE: interactome of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D1233–D1243. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yin, J.; Lu, M.; Mou, M.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Tan, Y.; Wang, S.; Chu, X.; Dai, H.; Hou, T. DrugMAP: molecular atlas and pharma-information of all drugs. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D1288–D1299. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Mou, M.; Li, X.; Xu, W.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, F. DrugMAP 2.0: molecular atlas and pharma-information of all drugs. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 51, D1372–D1382.

- Srivastava, A.; Vinod, P. A Single-Cell Network Approach to Decode Metabolic Regulation in Gynecologic and Breast Cancers. Systems Biology and Applications 2024, 11(1), 26.

- Jackson, S. E.; Chester, J. D. Personalised cancer medicine. International journal of cancer 2015, 137, 262–266.

- Kearney, T.; Flegg, M. B. Enzyme kinetics simulation at the scale of individual particles. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2024, 161(19).