1. Introduction

Molecular engineering approaches for the generation of improved molecules for applications in various industrial, research, and medical settings are in increasing demand. Structure-based drug design especially requires designed proteins and advances in structural proteomics and computational modeling. The discovery of various protein/receptor targets by genomic research has expanded rapidly. The automation of biochemical screening was in great demand in drug discovery research because the number of compounds to be tested could be in the millions unless the chemical libraries were made wisely and did not follow the auto-docking system without pharmacological knowledge. The in silico lecture for teaching enzyme reactions starts using qualitatively mathematical equations that describe the philosophy of phenomena; however, individual values are not provided; therefore, it is difficult for beginners to understand the individual biochemical phenomenon from these mathematical equations. Developing computational chemistry can provide various values to describe molecular properties with the stereo structures of proteins. The image impresses students with what is going on inside proteins. Consequently, we first calculate properties, combine them with the equations, and explain the phenomena quantitatively. Or simplify the processes and directly calculate properties from the drawn molecules. The latter method does not understand the biochemical mechanisms but can explain the phenomena quantitatively. However, the latter method can quantitatively accelerate understanding of the biochemical mechanism and advance research projects. Biochemistry describes biological reactions as a part of chemistry where enzymes convert precursors to target molecules (metabolism) after selective molecular interactions with substrates. That is, enzyme reactions demonstrate the selective difference from chemical reactions. The former reaction is rapid, and the latter reaction is slow. We have to select a rapid reaction with complicated purification processes of mixed samples or a slow and selective reaction with simple purification for our final purpose.

Many enzymes are involved in our lives, and enzyme reactivity has not been achieved quantitatively; therefore, further analysis of enzyme reactivity is required. Quantitative analysis of enzymes' reactivity allows for the design of mutants required to develop practical immunoassay methods, enzymatic biosensors, engineered enzymes, and new drugs. The basic phenomenon of molecular interactions has been studied based on quantitative analysis of molecular recognition using chromatography. Auto-docking programs are not satisfactory for this purpose, mainly because they recognize only the molecular shape and not the priority of the reaction center. Enzymatic reactions are simple chemical reactions that occur in specific chambers, where electron transfer can take place under low-energy conditions. One possible approach is the replacement of the original substrate used for obtaining a protein crystal with a new substrate, followed by quantitative analysis of the novel conformations produced [

1,

2].

In the developing process, several factors have been proposed, such as charge transfer interaction, Lewis acid-base interaction, and ion-ion interaction; however, the molecular interaction is quantitatively explained by a combination of mainly van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions using molecular mechanics calculations. Steric hindrance improves selectivity. Therefore, this report demonstrates the combination of hydrogen bonding and helps infer a protein's stereo structure using a related stereo structure and the sequence information. Furthermore, it provides a method for replacing a small substrate with a large one, using the MM2 program for quantitative analysis of the protein and its substrate interaction [

1,

2]. The performance of this method is demonstrated by quantitative analysis of the enzyme reactivity.

The quantitative analysis of reaction mechanisms of alcohol and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases, alanine [

3] and serine racemases [

4],

D-amino acid oxidase [

5], and acidic

D-amino acid oxidase [

1] was previously achieved; furthermore, those of aspartate racemase, glutamate racemase, aspartate oxidase, glutamate oxidase, arginine oxidase, lysine oxidase, Glycine amidinotransferase, Guanidinoacetic acid

N-methyl-transferase, Creatine Kinase, phenylalanine -4-monooxygenase (phenylalanine hydroxylase), and tyrosine hydroxylase are quantitatively described.

3. Results and Discussion

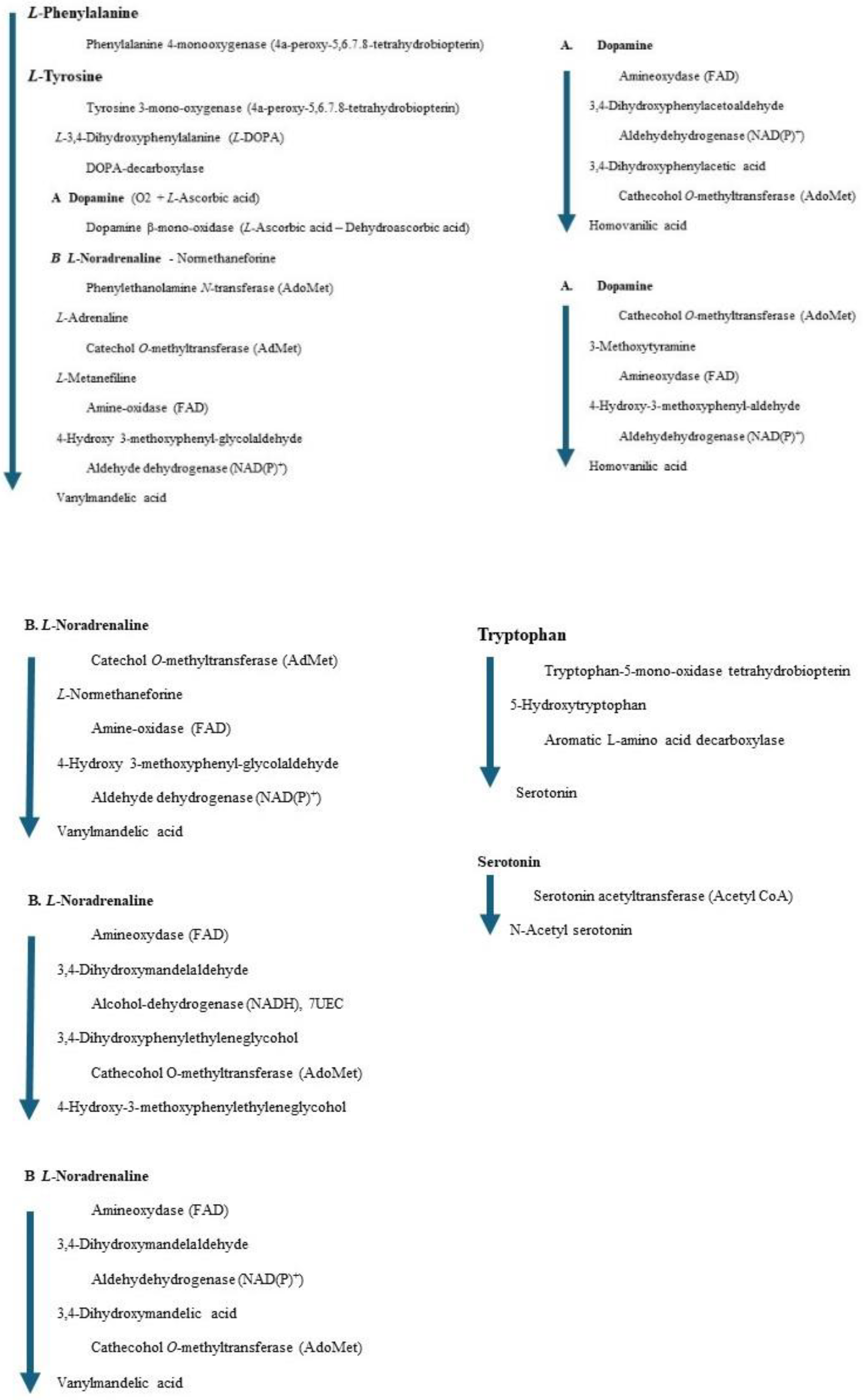

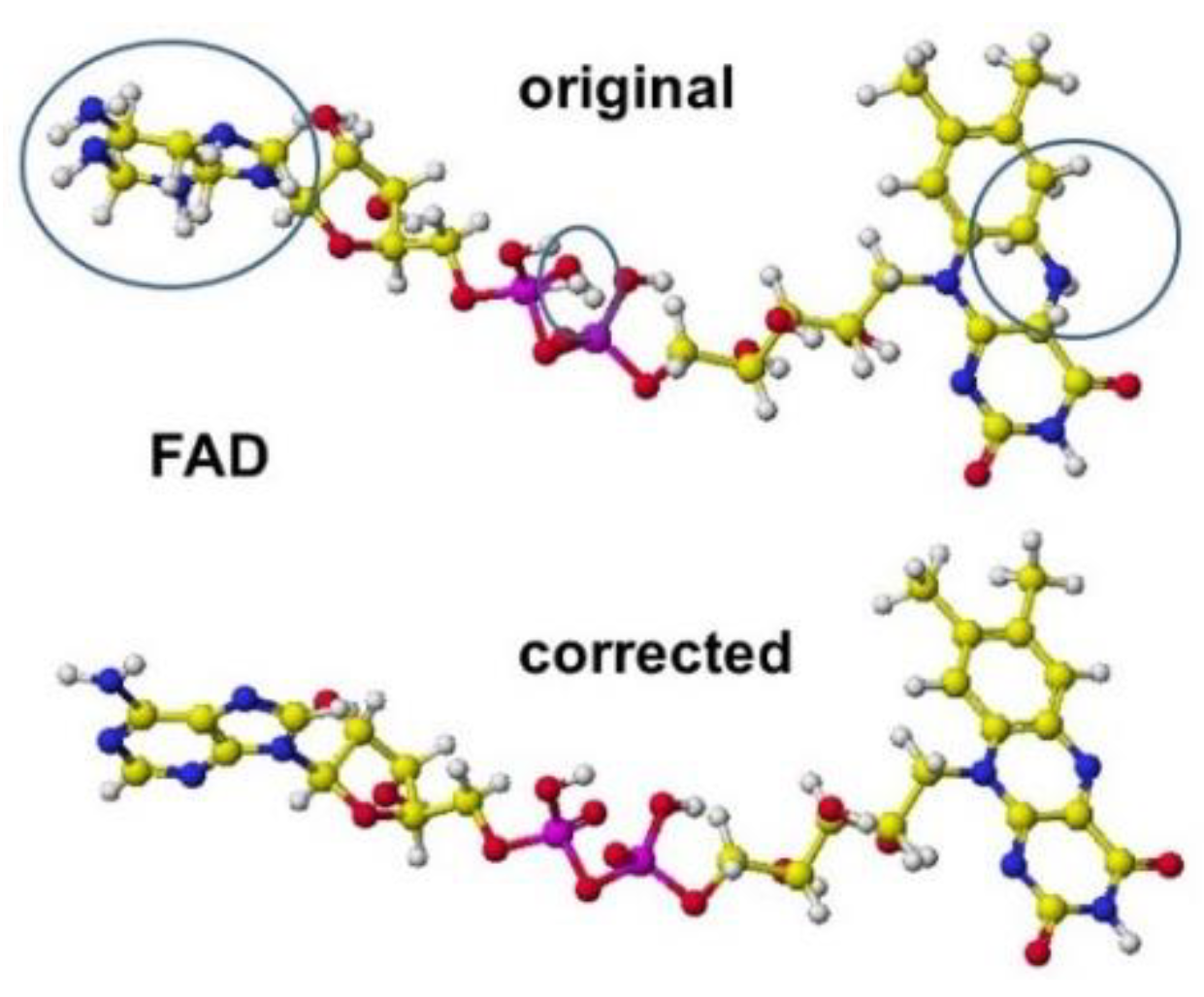

The most critical fixing point is the correction of coenzyme structures in which some atomic orbitals of carbon atoms should be sp

2; however, many of them are sp

3 orbitals. We must carefully correct the atomic orbitals of other elements of coenzymes and cofactors. Sometimes, the lysine amino group binds with the acidic carboxyl groups; however, these non-acceptable bonds can be found as long bonds. The correction points of coenzyme FAD are shown in

Figure 1 [

1].

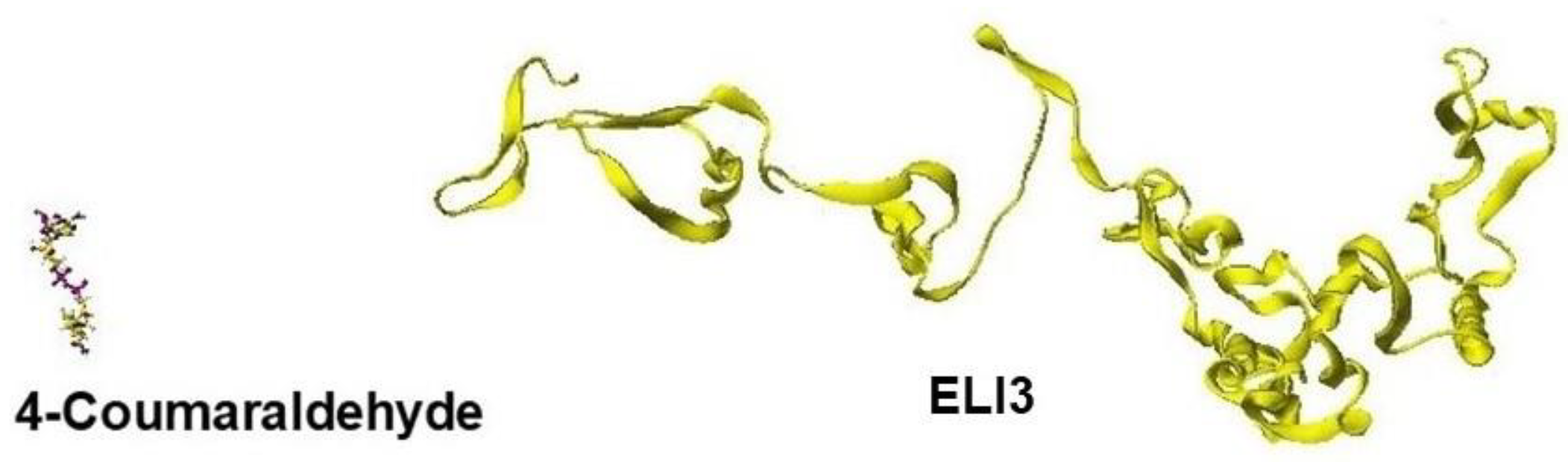

Replacing residual amino acids is a simple process, and replacing amino acids from the beginning and the end because these long-chain peptides do not affect the stereo structure of proteins; however, the order is a careful step. Then, we must replace one-by-one and step-by-step helix amino acids where helix structures are relatively rigid and keep the stereo structure; then, optimize the whole structure; otherwise, the stereo structure can be destroyed. Otherwise, the stereo structure becomes a free shape, as one example is shown in

Figure 2.

In the modification process from the mold protein to a target protein, step-by-step optimization is necessary. Figure 26 shows the optimized ELI3 structure after replacing all amino acids. The optimized structure kept the helix structures, but the interactions between helix coils failed, and the coenzyme was wholly separated [

1].

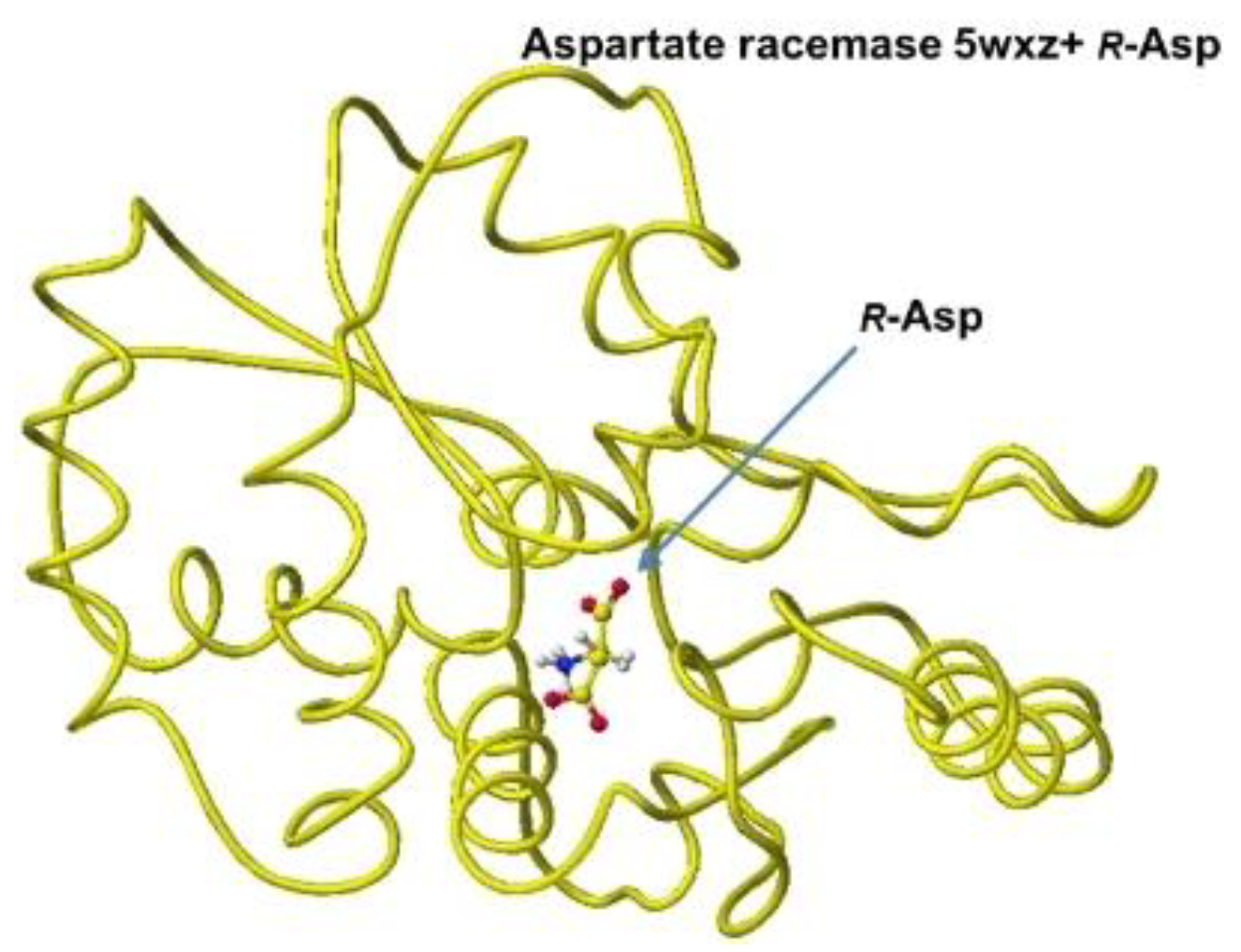

3.1. Aspartate Racemase

S(L)-Amino acids represent the most common amino acid form, most notably as protein residues, whereas

R(D)-amino acids, despite their rare occurrence, play significant roles in many biological processes. Amino acid racemases are enzymes that catalyze the interconversion of

S(L)- and/or

R(D)-amino acids.

R(D)-Aspartate is abundant in the developing brain, and the source of

R(D)-aspartate has been searched. A cloned mammalian aspartate racemase was identified in the brain and neuroendocrine tissues [

6]. The complex conformation of the aspartate racemase is different from that of

R(D)-aspartate oxidase [

5]. In

R(D)-aspartate oxidase, two guanidyl groups contact two carboxy groups of aspartate to hold an aspartate at the exact position, and the aspartate amino group faces the coenzyme FAD flavine carbonyl group. The amino group is oxidized, and the aspartate is converted to a keto-acid. The location of two alginic guanidinyl groups is critical in the selective reaction.

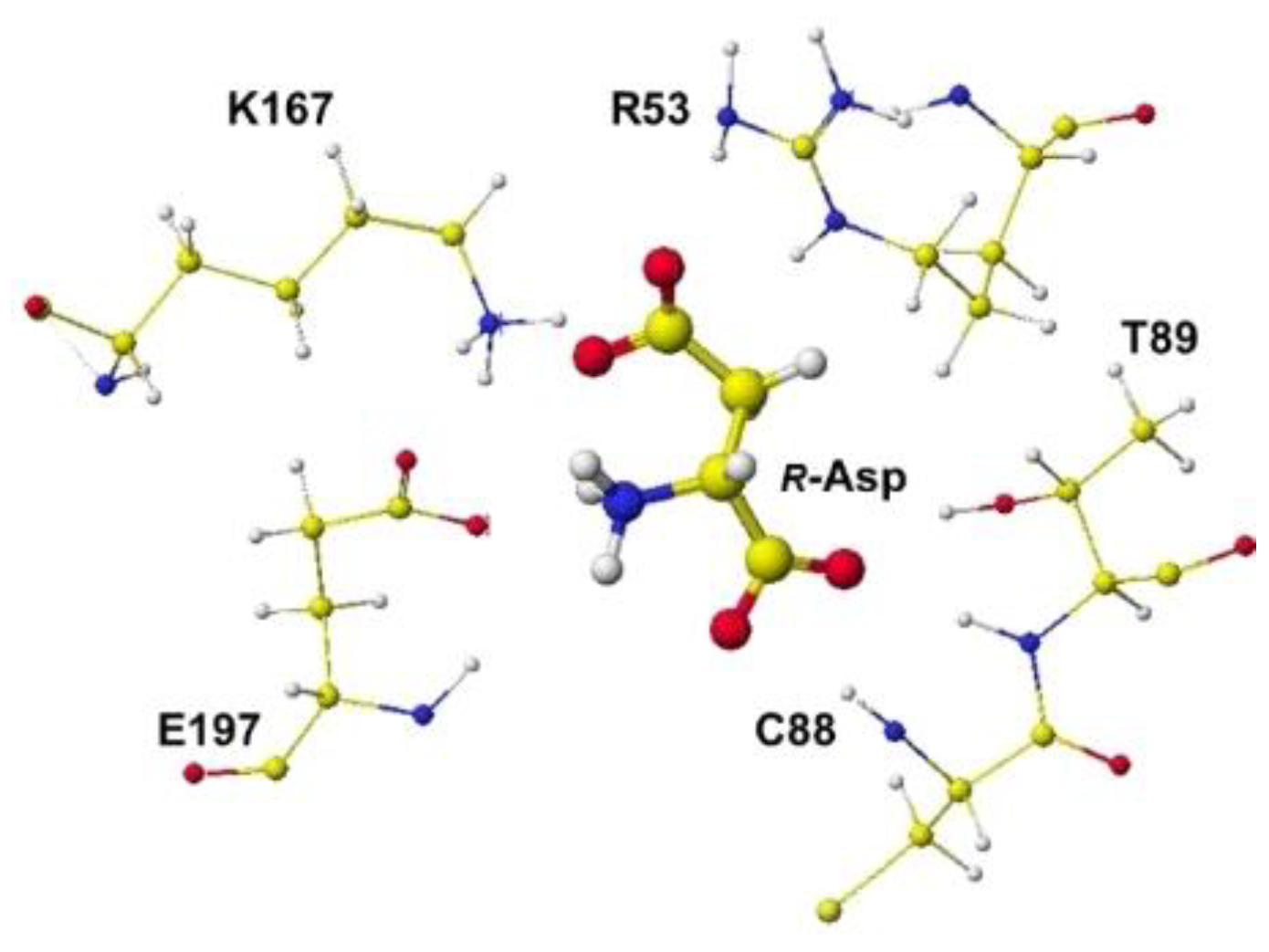

The downloaded stereo structure PDB 5wxz (Crystal structure of Microcystis airuginosa PCC 7806 aspartate racemase in complex with

R(

D)-aspartate without coenzyme) was optimized. The original aspartate was replaced with

S(L)-aspartate, and the complex structures were optimized using an MM2 program. Extracted

R(D)- and

S(L)-aspartate atomic angles were compared with the original angles; generally, the rotation of the amino acid, racemization, occurs in the smallest atom (hydrogen). Indeed, the complex formation with the racemase flattened the original structures inside the protein. The optimized complex Structure and the extracted Structure, which clearly exhibited the complex conformation, are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The

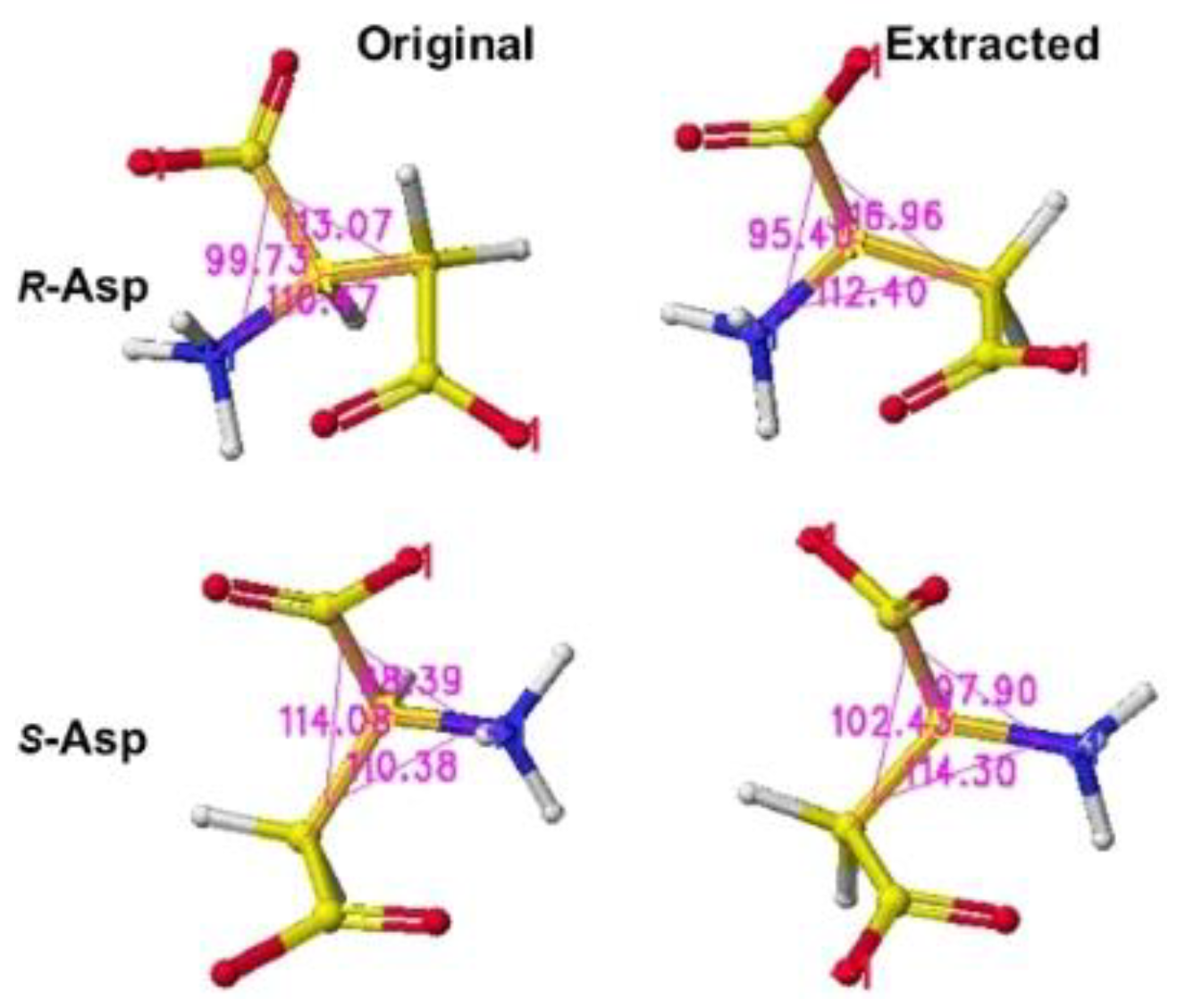

R(D)-aspartate b-carboxy group is tightly contacted with R53 and K167 via ion-ion interaction. The a-amino group is tightly contacted with E197 via ion-ion interaction, but the a-carboxy group is weakly contacted with the L99 peptide bond amino group and T88 hydroxy group via hydrogen bond. The angles of

S(L)- and

R(D)-aspartates are given to describe the structural changes in

Figure 5. The atomic angles of aspartate before and after complex formation are summarized in the following

Table 1.

In the case of the aspartate racemase, only the E197 carbonyl group tightly contacts the aspartate amino group via ion-ion interaction, but the a-carboxyl group contacted S87, S89, S128, and T496 hydroxy groups via hydrogen bond. The bcarboxy group binds with the R53 guanidino group and K165 amino group via ion-ion interaction. By the way, R- and S-aspartate were flattened inside the racemase. The total angle of R- and S-aspartate expanded by 2.28 and 6.81°. The electro-localization also supported the conformation change. It seemed the enzyme is favorable in the racemization of S(L)-aspartate.

The proposed reference racemization mechanism was not the same as that obtained in this

in silico analysis. Especially, the contribution of E197 was not mentioned in the reference. McyF is an aspartate racemase is a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) independent amino acid racemase that produces the substrate

R(D)-aspartate for the biosynthesis of microcystin in the cyanobacterium

Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806. The structural analyses indicate that McyF and homologs possess highly conserved residues involved in substrate binding and catalysis. In addition, residues C87 and C195 were assigned to the key catalytic residues of "two bases" that deprotonate

R(D)-Asp and

S(L)-Asp. Further, site-directed mutagenesis combined with enzymatic assays revealed that G197 also participates in the catalytic reaction. The findings provide structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of aspartate racemase and microcystin biosynthesis [

7]. However, the aspartate amino group should contact a carboxy group for the strong ion-ion interaction. These enzymes do not require a coenzyme. However, other racemases (alanine racemase and serine racemase) require coenzyme pyridoxal-5’-phosphate (PLP), and a reference aspartate racemase requires coenzyme PLP.

3.2. Glutamate Racemase

Glutamate racemase is an enzyme essential to the bacterial cell wall biosynthesis pathway and has been considered a target for antibacterial drug discovery. Three distinct mechanisms of regulation for the family of glutamate racemases: allosteric activation by metabolic precursors, kinetic regulation through substrate inhibition, and

R(D)-glutamate recycling using an

R(D)-amino acid transaminase were described. They found a series of uncompetitive inhibitors that bind to a cryptic allosteric site [

8]. Glutamate racemase, a member of the cofactor-independent, two-thiol-based family of amino acid racemases, has been implied in producing and maintaining sufficient

R(D)-glutamate [

9].

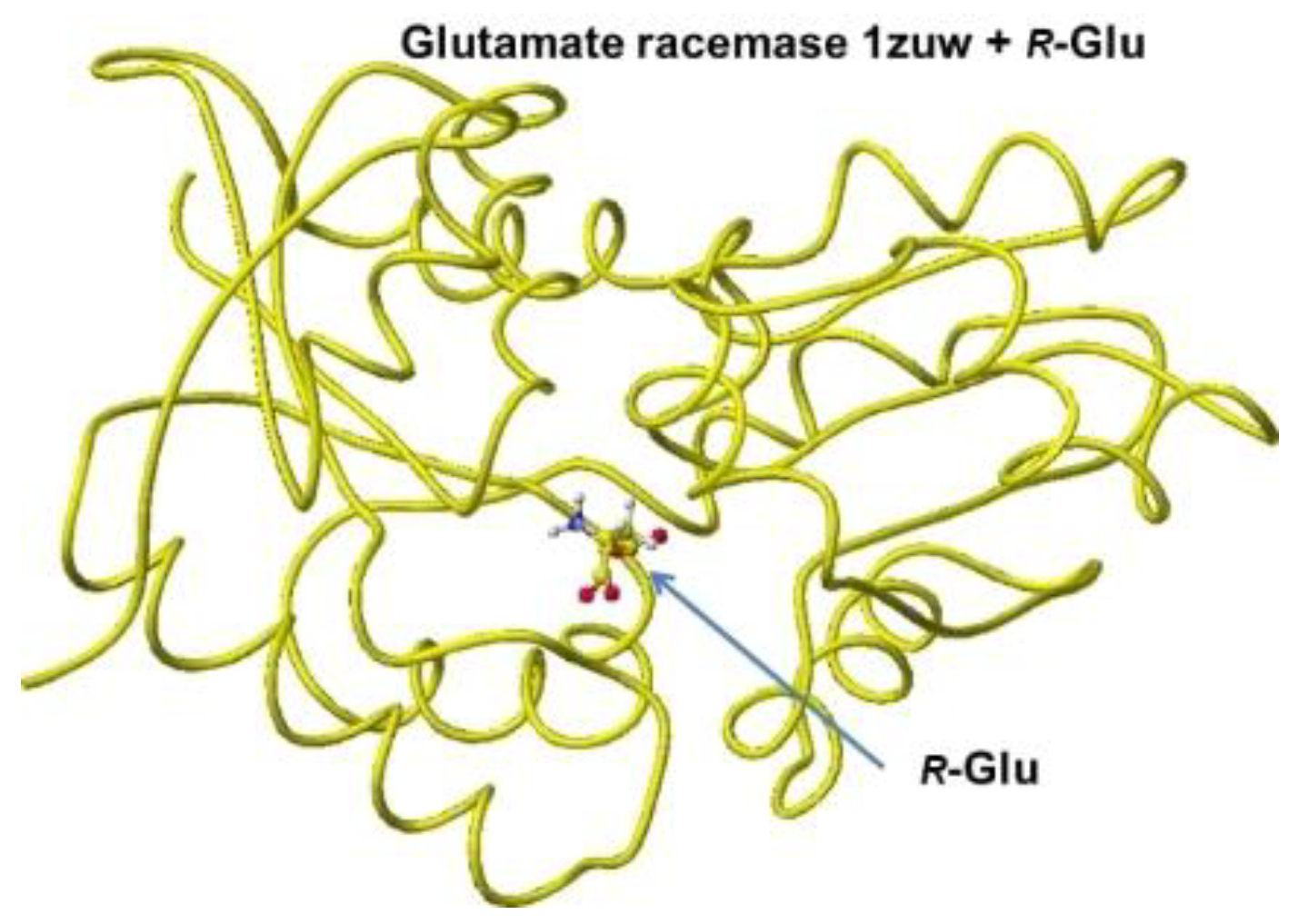

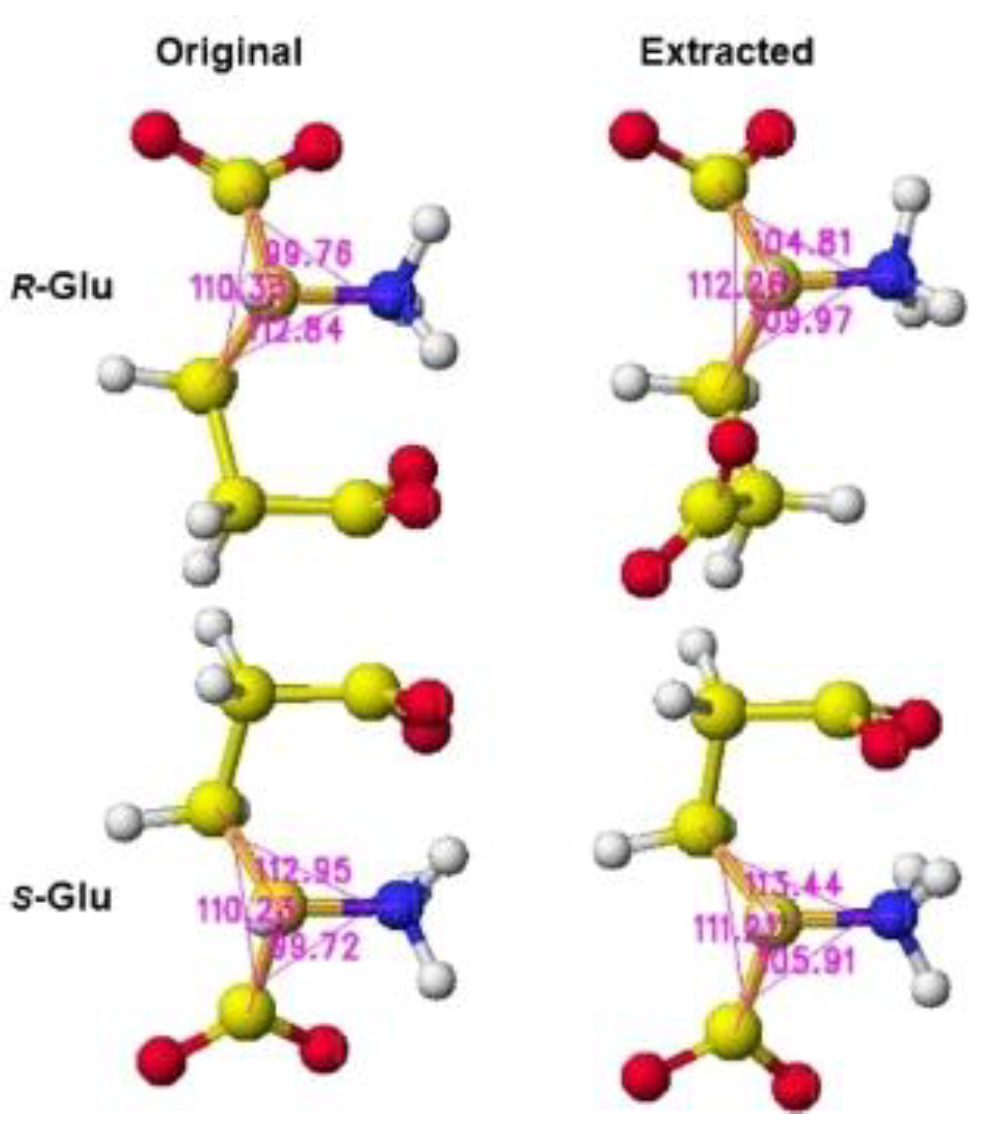

The stereo structure PDB 1zuw (Human Mitochondrial Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Asian Variant, ALDH272, Apo Form, [

1]) was downloaded, and the small molecules (1,2-ethanediol and guanidine) were replaced with

R(D)- or

S(L)-glutamate; then being optimized the complex structures. The atomic angle of extracted

R(D)- and

S(L)-glutamate was measured, and the difference from the original angles was described. Generally, the rotation of an amino acid, racemization, occurs by moving the smallest atom (hydrogen). Indeed, the original structures were flattened, and the total angles changed by about 7 degrees, as the complex form of the enzymes. The optimized complex Structure and the extracted Structure, which clearly exhibited the complex conformation, are shown in

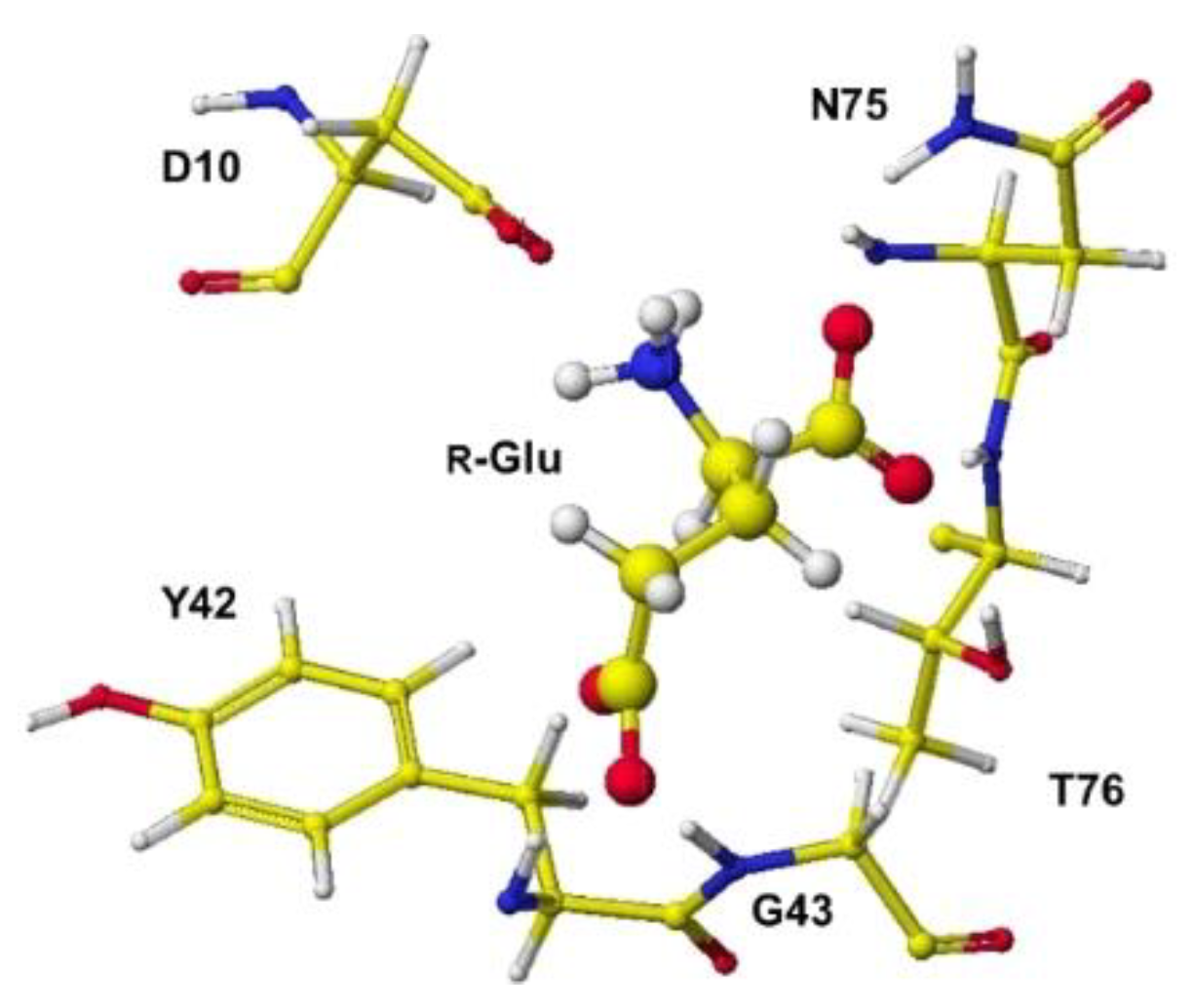

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The angles of

S(L)- and

R(D)-glutamates are given to describe the structural changes in

Figure 8. The atomic angles of glutamate before and after complex formation are summarized in the following

Table 2. This enzyme seemed to favor the racemization of

S(L)-glutamate.

The complex conformation of glutamate racemase is similar to that of aspartate racemase. In the case of the glutamate racemase, only the D10 carbonyl group tightly contacts the glutamate amino group via ion-ion interaction, but the a-carboxyl group contacts N74 amino group and T76 and T186 hydroxy groups. The g-carboxy group does not demonstrate a strong binding site. By the way, R(D)- and S(L)-aspartate were flattened inside the racemase. The total angle of R(D)- and S(L)-aspartate was expanded by 4.11 and 7.17°. The electro-localization also supported the conformation change. The exchange of contact sites of a- and g-carboxy groups may not be possible due to the possible strong binding of the a-amino group and D10 carboxy group.

The proposed conformation at the racemization site is different from that proposed in references 9 and 10, where two thiols contact an S(L)-glutamate amino group. However, the flexibility around a-carbon is the key factor. The final decision will be made using a computer system that can calculate the large molecules' transition state.

3.3. Aspartate Oxidase

S(L)-Aspartate oxidase (a flavoenzyme) converts aspartate to imino-aspartate using either molecular oxygen or fumarate as electron acceptors, and the structure was determined, and the binding site was proposed [

11].

S(L)-Aspartate oxidase from the thermophilic archaea Sulfolobus Tokodaii was produced as a recombinant protein in E. coli in the active form of a holoenzyme. High thermal stability biocatalyst for producing

R(D)-aspartate [

12]. Recombinant thermostable aspartate oxidase was used enantiomerically pure

R(D)-aspartate [

13].

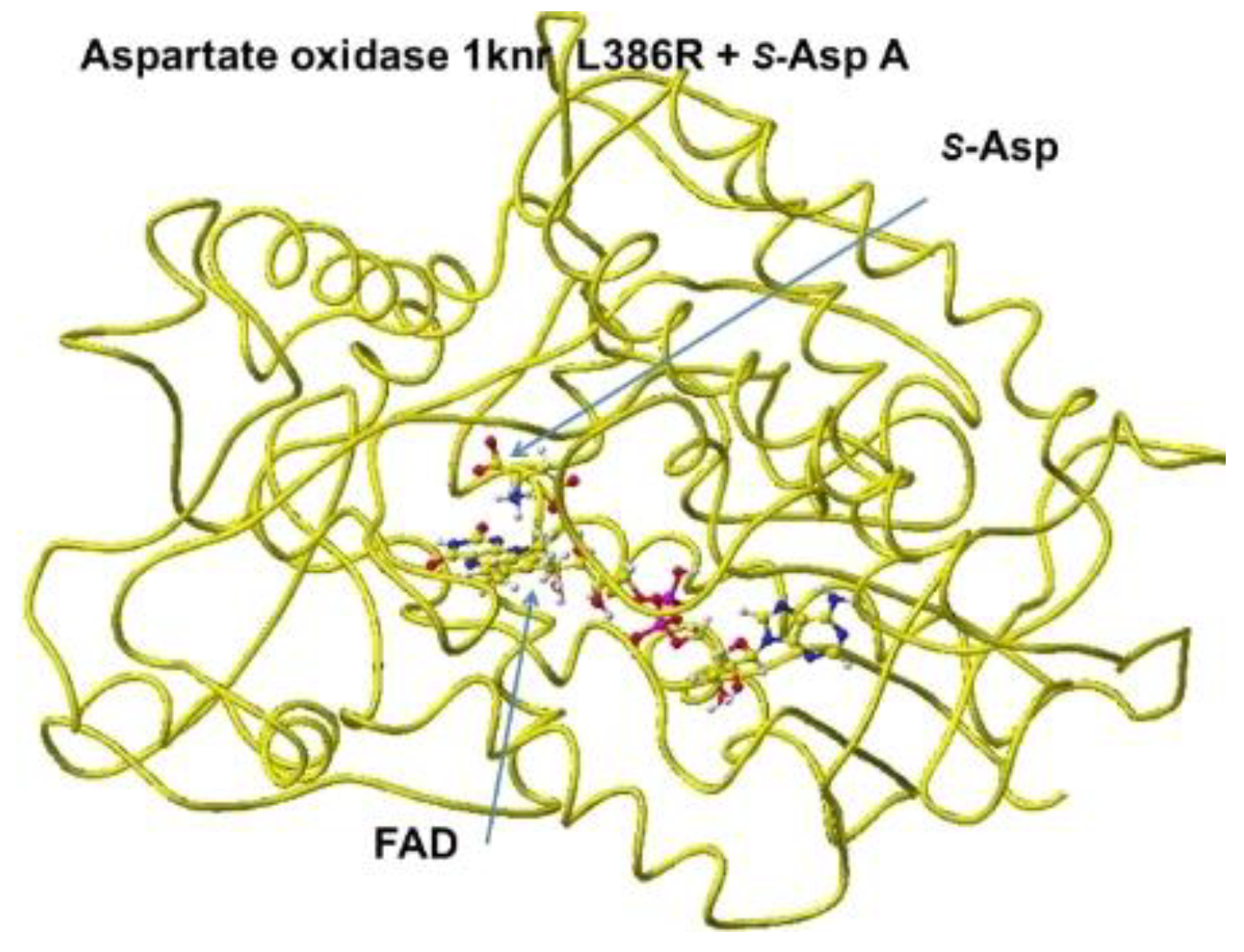

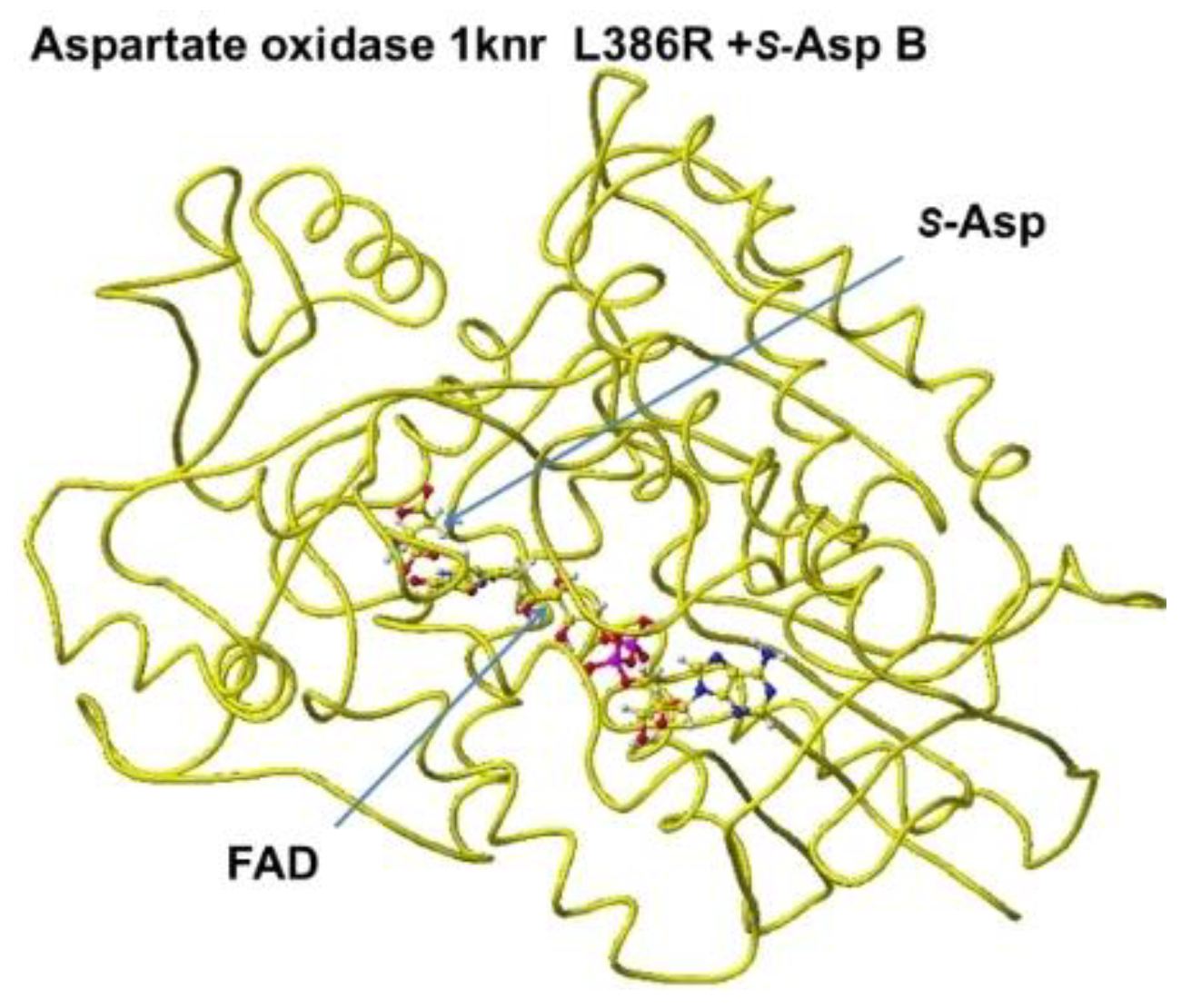

The downloaded stereo structure of PDB 1knr (

S(L)-aspartate oxidase [

14]: R386L mutant of Escherichia coli) was optimized after a mutation of L386R and fixing the structure of the FAD flavine ring. Two possible locations are where

S(L))-aspartate is oxidized around the FAD flavine ring. The strongest molecular interaction (ion-ion interaction) is found between the substitute aspartate carboxy group and the residual protein arginine guanidyl group of

R(D)-aspartate oxidase [

11]. However, the key guanidyl group does not exist at the same location in the

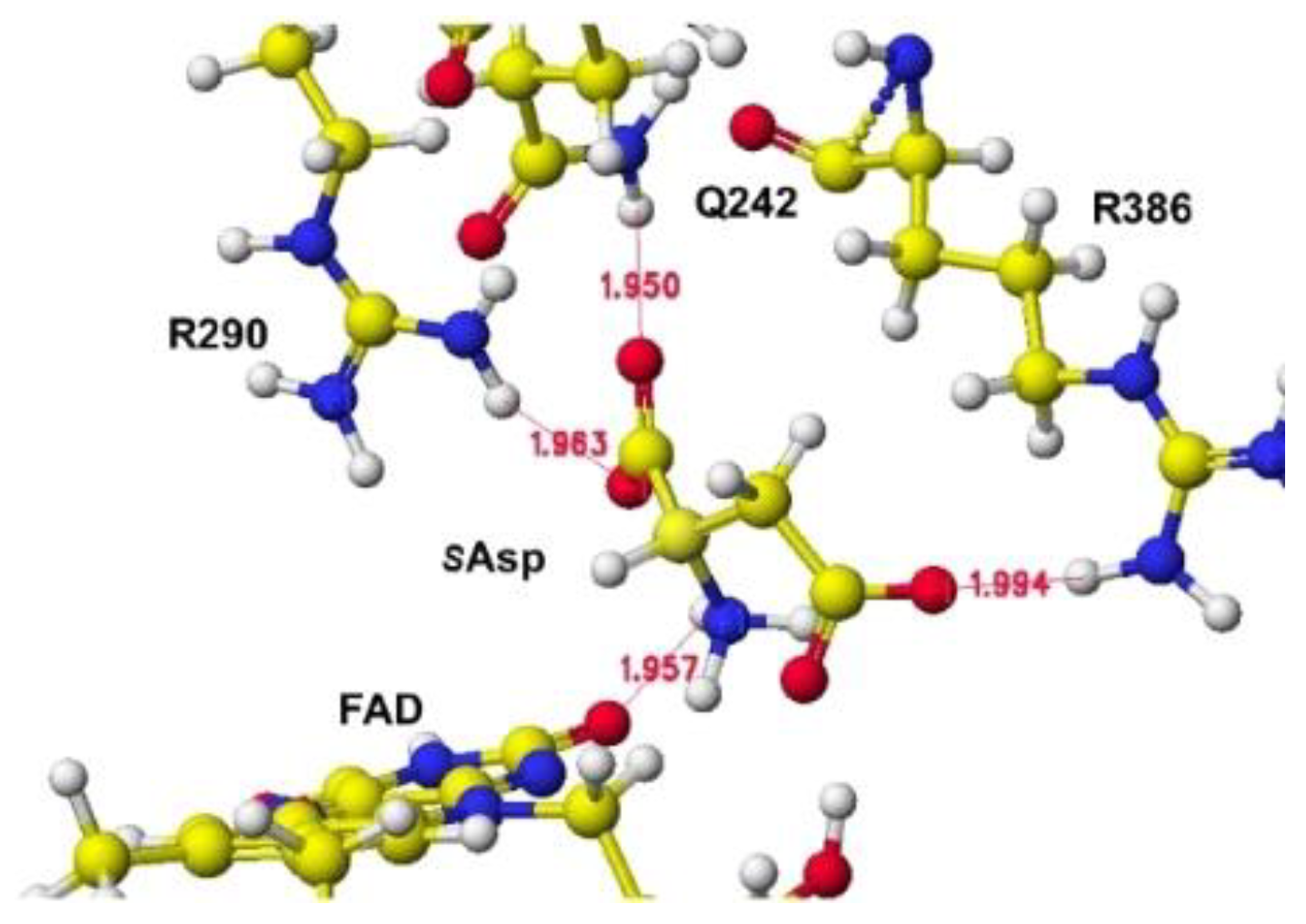

R(D)-aspartate oxidase is near the flavine carbonyl group, and another is located near the FAD flavine ring methyl group. One guanidyl group is located near the flavine carboxy group, but another is located near the FAD hydroxy group and a little far to form a binding with the aspartate b-carboxy group, shown in

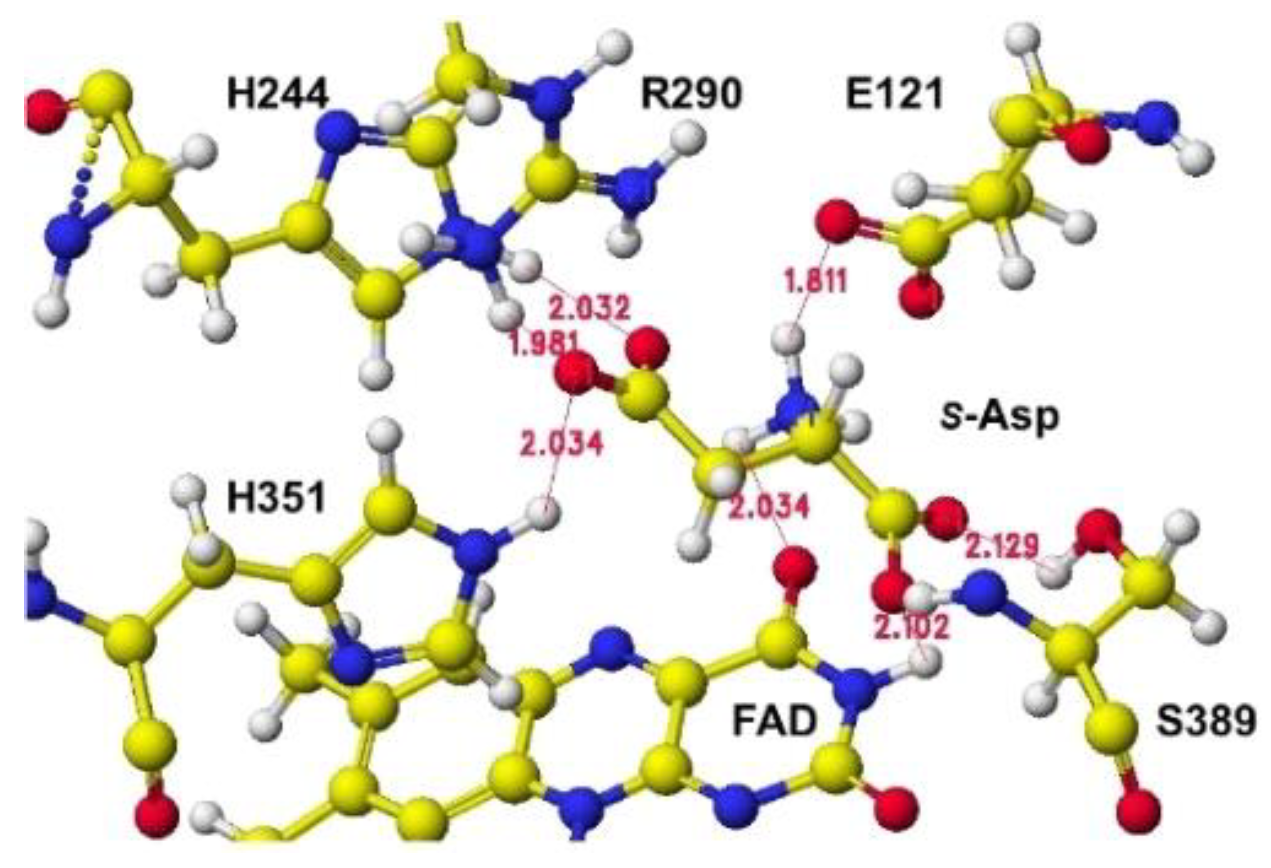

Figure 9, where the b-carboxy group contacts with the R386 guanidyl group and a-carboxy group contact with the R290 guanidinyl group (

Figure 10).

S(L)-glutamate also formed a complex in this location compared to

S(L)-aspartate

in silico analysis. The a-amino group is located near a different flavine carbonyl group from

R(D)-aspartate oxidase. The possible 2

nd complex conformation is shown in

Figure 11, where the b-carboxyl group contacts the H351 ring, but no guanidyl group does not exist around the location (

Figure 12). In this location B,

S(L)-alanine, and

R(D)-aspartate might be oxidized; however, a nearby carboxy group (E121) contacted their amino group even if the amino group was located near the flavine carbonyl group. The electron localization of amino acid a-carbon may indicate the possibility, as the value supported the selective oxidation of

R(D)-amino acid oxidase [

11]. The optimized (final structure) energy values of conformations A and B (Figures 9.91 and 9.93) were -9078.9 and -8594.4 kcal mol

-1.

The apc of the extracted S(L)-aspartate alpha carbon from the optimized stereostructure was changed from -0.265 to -0.157 au at location A (Figure 9.92), and that was changed from -0.265 to -0.135 au at location B (Figure 9.94). It seems that location B is a favorite complex like that of R(D)-aspartate oxidase; however, the location is not specific for S(L)-aspartate based on the electron localization.

The above approach was based on the reaction process of

R(D)-aspartate oxidase, but not the same as that reported, where the succinate complex was the major reaction process to produce fumarate [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Their initial complex conformations were the same as the two residual arginine guanidinyl groups that contacted the two aspartate carboxy groups. Conformation A, in which two guanidinyl groups were contacted with two aspartate carboxy groups, was more stable than conformation B, in which one guanidyl group was contacted with one aspartate carboxyl group. However, apc of a-carbon indicated that the diamino reaction was a favor in conformation B. The detail about

S(L)-aspartate oxidase catalysis for a succinate-formate reaction was described, but the

S(L)-aspartate oxidase reaction mechanism was estimated and proposed in conformation A. The aspartate amino group was far from the proposed flavine ring nitrogen in conformation A.

S(L)-Aspartate oxidase involved the succinate formation from fumarate in cyanobacteria, but the diamino reaction was not described [

15]. This FAD-dependent enzyme is distinct from most amino acid oxidases and closely resembles those of the succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase family rather than the prototyped

R(D)-amino acid oxidases [

16]. This conclusion is based on the conformation around

S(L)-aspartate.

R(D)-Aspartate two carboxy groups in

R(D)-aspartate oxidase are held with two guanidyl groups of the enzyme. This conformation is possible, but the location of the amino group is different, as shown in

Figure 10. The conclusion of the reference can be supported by the conformation B shown in

Figure 12.

3.4. Glutamate Oxidase

Glutamate oxidase has been used for the selective analysis of glutamate in food and pharmaceuticals, and various analytical systems have been developed [

17,

18]. Glutamate oxidase was purified, and the reaction products were determined spectrophotometrically. The reaction selectivity of purified

S(L)-glutamate oxidase was studied [

19].

S(L)-glutamine oxidase was immobilized for the enzyme assay [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The censor was used for monitoring glutamate from cultured nerve cells [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. A combination of glutamate racemase and oxidase censors permitted continuous analysis of both

R(D)- and

S(L)-glutamates [

34]. Glutamate oxidase was used to selectively analyze a neurotoxic amino acid, 3-

N-oxalyl-

L-a,b-diamino-propionic acid [

35]. A recombinant

S(L)-glutamate oxidase was developed for a stable biosensor [

36]. The amino acid (

S(L)-glutamate) is prevalent throughout the mammalian brain, with an estimated 60-70% of synapses using it as their neurotransmitter. A Pt/glutamate oxidase-based sensor was developed and demonstrated the reliable detection of glutamate physiological changes in response to rats' behavioral/neuronal activation [

37].

a-Ketoglutarate, employed to treat mild chronic renal insufficiency, was obtained through enzymatic oxidation of monosodium glutamate catalyzed by

S(L)-glutamate dehydrogenase coupled with NADH oxidase for the regeneration of NADH back to NAD

+ [

38]. The glutamate reuptake by dedicated transporters prevents its accumulation at the synapse as well as non-physiological spillover. Indeed, extracellular glutamate increases the incidence of aberrant synaptic signaling, leading to neuronal excitotoxicity and cell death [

39]. The quantitative

in silico analysis of the reaction mechanisms was performed.

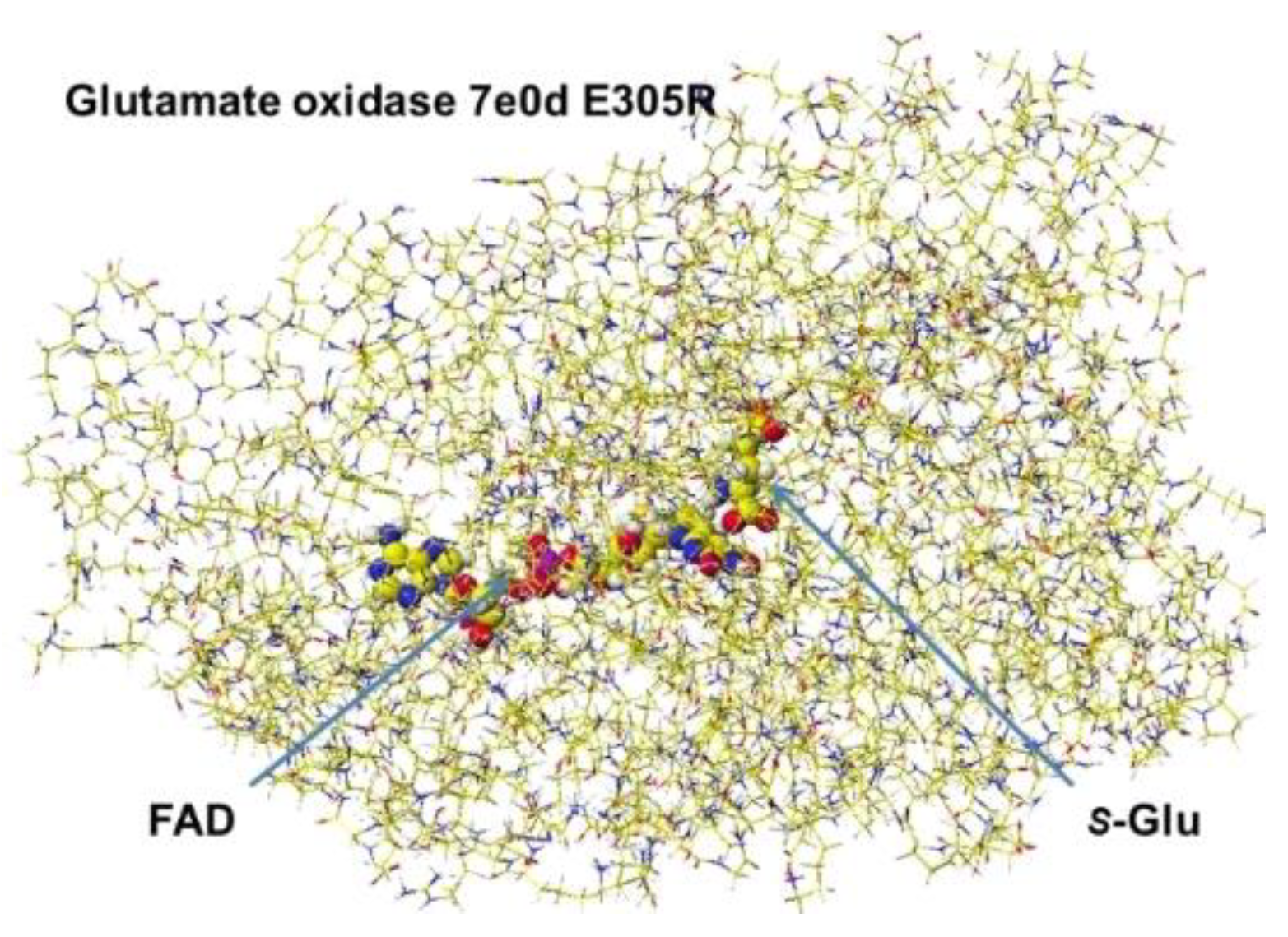

The stereo structure PDB 7e0d (Structure of

S(L)-glutamate oxidase R305E mutant in complex with

S(L)-arginine of Streptomyces sp. X-119-6) was downloaded. E305 was reversed to R305, and the FAD structure was fixed. The complex structure was optimized using the MM2 program. The optimized structure is shown in

Figure 13. Considering the stereo structure of acidic

S(L)-amino acid oxidase, the a-carboxy group contacted the R124 guanidyl group via ion-ion interaction, and the g-carboxyl group contacted the guanidyl group of R305. The a-amino group was located near the flavine carbonyl group and contacted the carboxy group of E617. Furthermore, the possibility of

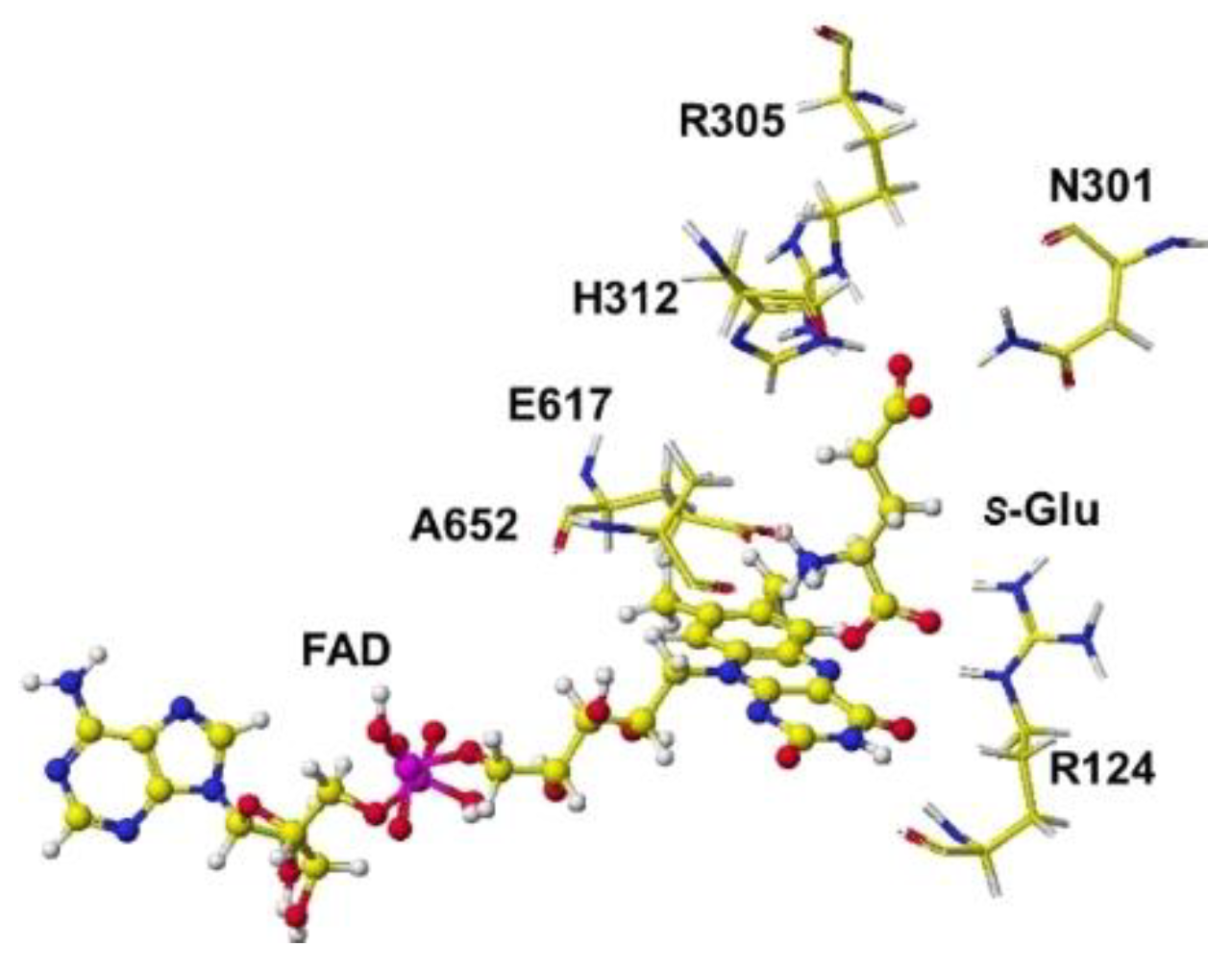

R(D)-glutamate oxidation was studied.

The oxidation mechanism is fundamentally the same as that of

R(D)-aspartate oxidase. The glutamate a-amino group was located near the FAD flavine ring, and the a-carboxy group contacted the R124 guanidyl group, but the g-carboxy group contacted N301, H312, and R305. However, the strong tie with the R304 guanidyl group was not observed (

Figure 14). The apc of the extracted

S(L)-glutamate a-carbon from the optimized stereostructure was changed from -0.202 to -0.192 apc.

3.5. Arginine Oxidase

S(L)-Arginine oxidase discovered in

Pseudomonas sp. TPU7192 is a FAD-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative deamination of

S(L)-arginine and converts

S(L)-arginine to 2-ketoarginine. The cloned enzyme demonstrated high selectivity for

S(L)-arginine [

40]. The enzyme selectivity of ancestral and native

S(L)-arginine oxidase was extensively analyzed. The native is

Oceanobacter kriegii S(L)-arginine oxidase in bacteria. The designed ancestral

L-arginine oxidase was thermostable and exhibited very high selectivity. They found

S(L)-arginine oxidase may have evolved from a thermostable and promiscuous

S(L)-amino acid oxidase [

41]. The mutation of

S(L)-glutamate oxidase (R305E) from Streptomyces sp. X-119-6 developed an enzyme to catalyze

S(L)-arginine [

42]. The stereo structure of

L-arginine oxidase was PDB 7e0d (Structure of

S(L)-glutamate oxidase R305E), and a substrate

S(L)-arginine was installed instead of

S(L)-glutamate, and the complex structure was optimized.

S(L)-Amino acid oxidase/monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. AIU 813 catalyzes the oxidative deamination of the

S(L)-amino acid a-amino group to produce a keto acid. Therefore, the conformation analyses of

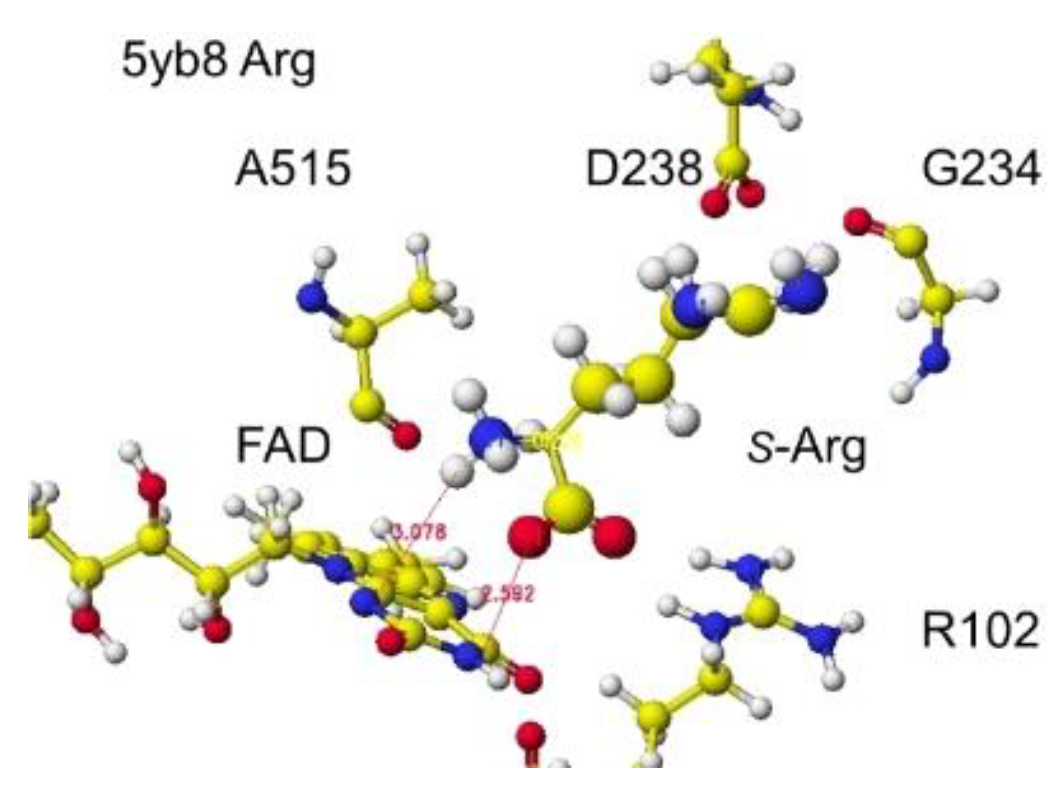

S(L)-lysine, arginine, and ornithine were achieved by preparing these complex structures. Furthermore, the mutation effect of D238 was performed by preparing D238A, D238F, and D238E. The key residual amino acids are D238 and Q258, tightly contact with the a-amino group of substitute amino acids, and D238 tightly contacts the basic group of the substitute amino acids by ion-ion interaction [

43] as found for

R(D)-amino acid oxidase [

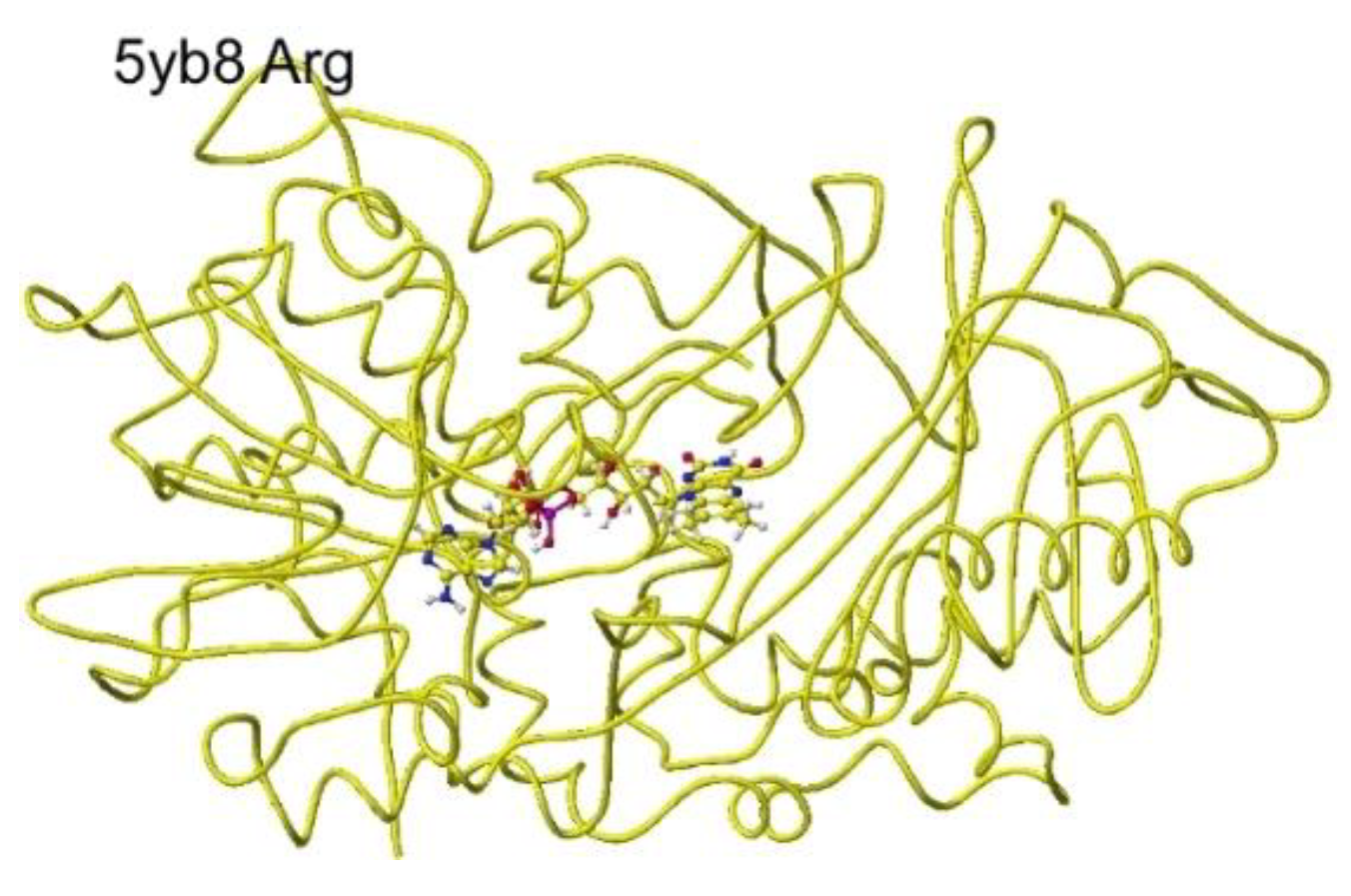

5]. Therefore, the

S(L)-complex arginine structure (RSCB PDB 5yb8, s(

L)-amino acid oxidase/monooxygenase) was downloaded, and the conformation analysis was performed. The corrected and optimized structure is shown in

Figure 15, and the detail is shown in

Figure 16.

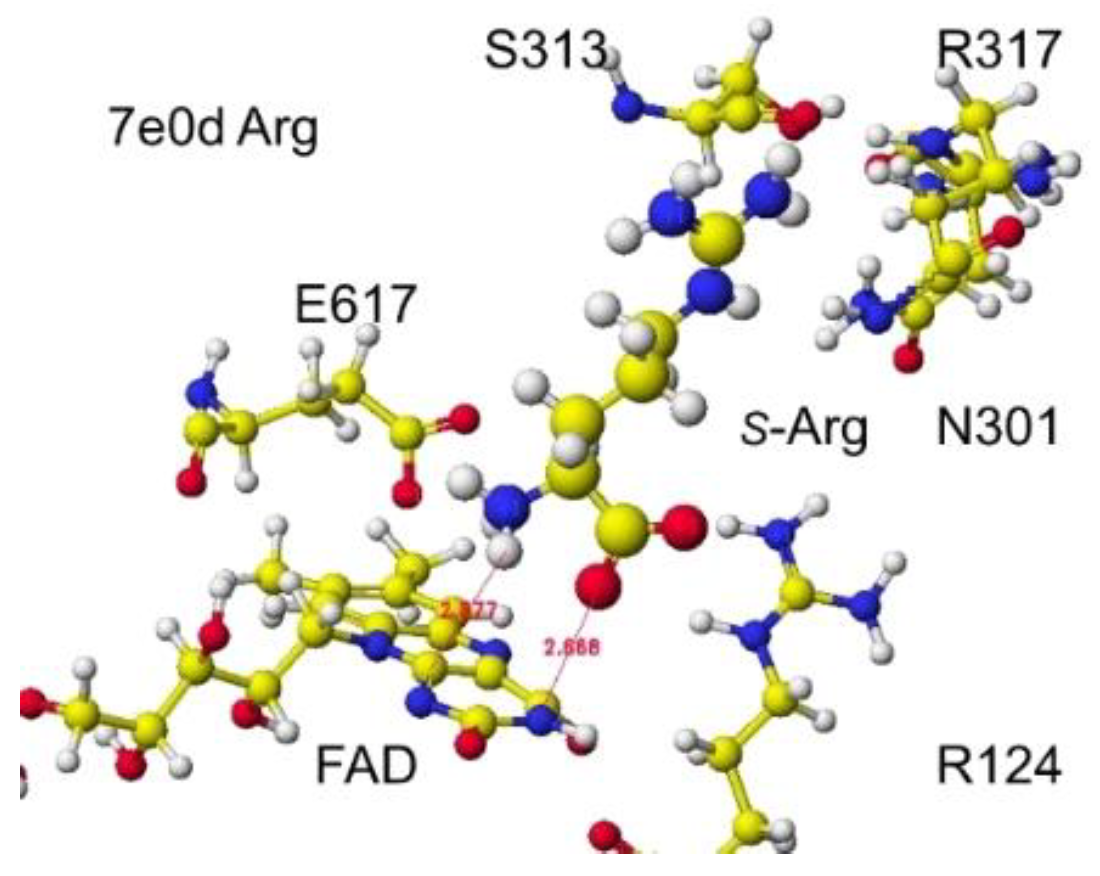

The shortest distance between the arginine amino group and the FAD flavine ring was 3.1 Å, and the a-carboxy group was within 2.6Å. The apc value of a-carbon was changed from 0.263 to 0.226 au. An engineered

S(L)-arginine oxidase was developed by a mutation R305E of the initially created

S(L)-lysine oxidase (RSCB PDB 7e0c) from

S(L)-glutamate oxidase from Streptomyces sp. X-119-6 (RSCB 2e1m). The protein structure was crystallographically determined and registered as PDB 7e0d. The conformation analysis demonstrated the highly selective

S(L)-arginine oxidase [

44]. Further in silico analysis of 7e0d was performed. The corrected and optimized structure is shown in

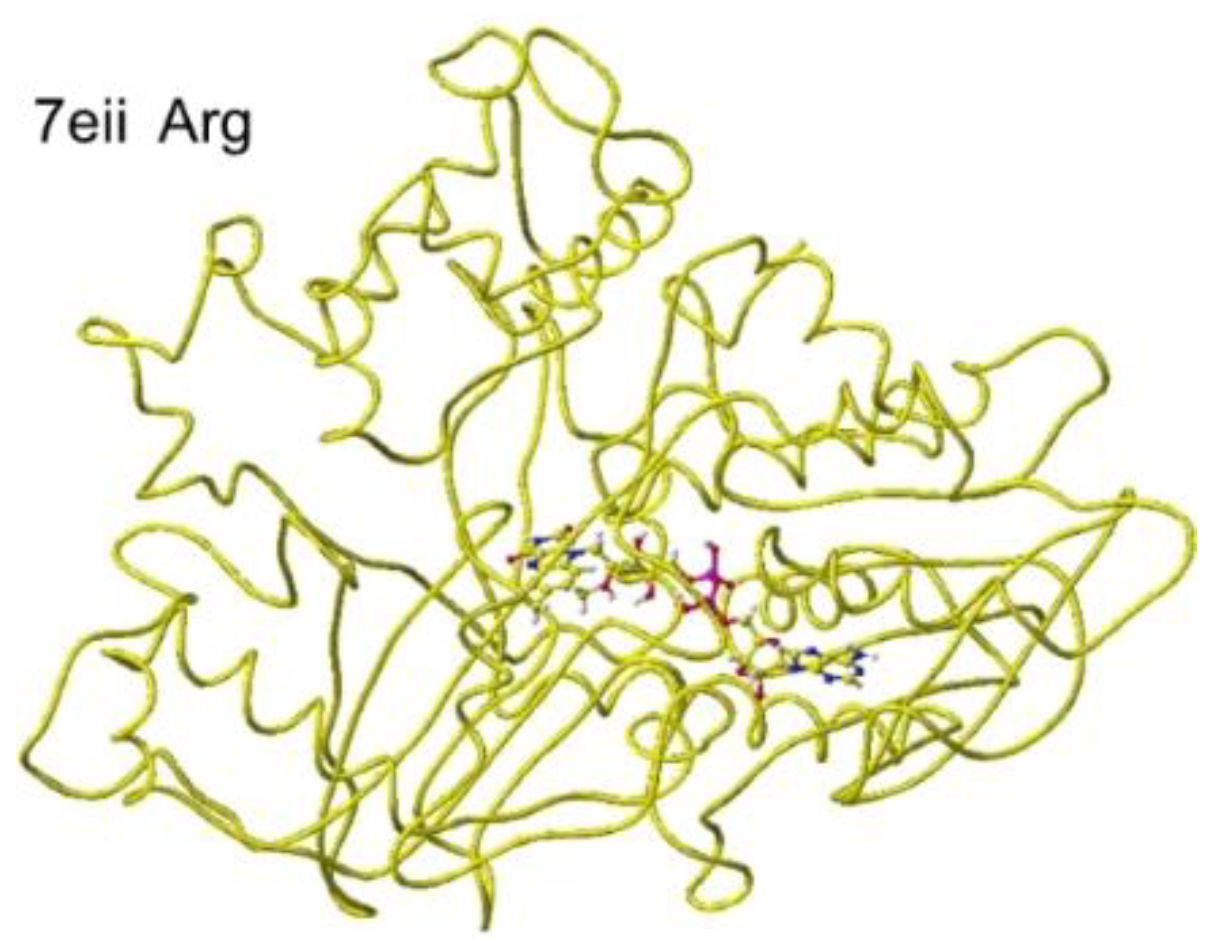

Figure 17, and the detail is shown in

Figure 18

The original Structure of

S(L)-arginine was deformed a lot inside these optimized

S(L)-arginine oxidases, as shown in

Figure 9. The atomic distance between the substitute arginine amino group and the FAD flavine ring was less than 3.1Å in 5yb8 and less than 2.9Å in 7e0d. The apc of arginine a-carbon was changed from -0.263 au to -0.180 in 5yb8. In 5yb8, the arginine guanidyl group contacts D238, and the carboxy group contacts R612 by ion-ion interaction. In 7e0d, the substitute arginine carboxy group contacts R124 by ion-ion interaction, and the guanidyl group contacts S313, M302, and N301 by hydrogen bonds with their peptide connection carbonyl oxygen and hydroxy groups. These property differences indicate that their reaction speed may be different even if these enzymes selectively oxidize

S(L)-arginine. The selective oxidation of

S(L)-arginine was high in 7e0d.

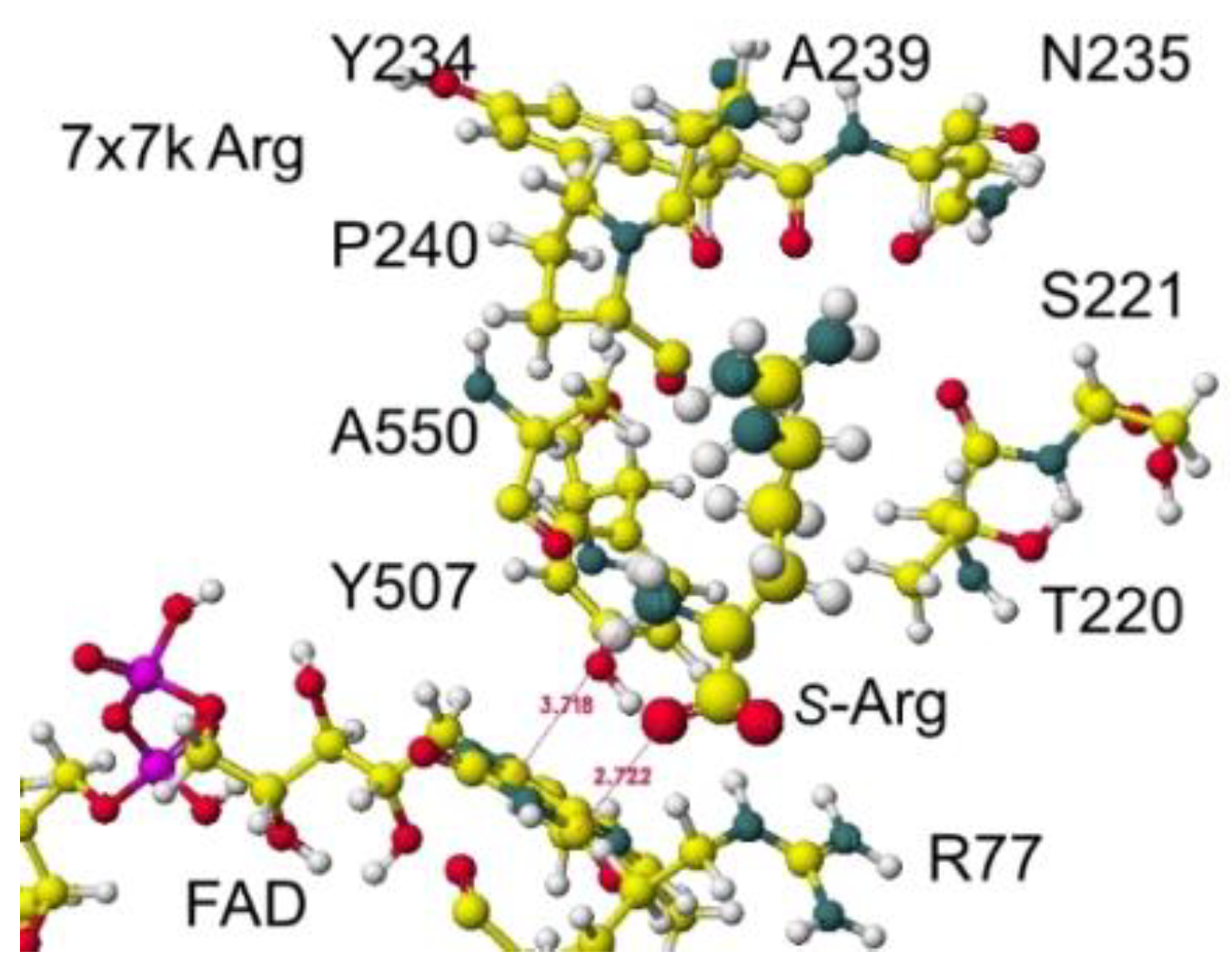

Similar results were obtained for 7x7k ancestral lysine oxidase [

5]. The optimized structure is shown in

Figure 19, and the conformation in detail is shown in

Figure 20.

The atomic distance between the substitute lysine carboxy oxygen and the flavine ring was 2.7Å, and that between the residual lysine a-amino group and the flavine ring was 3.7Å. Both oxygen and amino hydrogen were contacted with the flavine ring; however, monooxygenase's activity seemed stronger. The atomic partial charge of a-carbon was 0.000 from -0.263 au. 7eij ancestral

S(L)-Lys oxidase K387A variant with

S(L)-arginine was also oxidized

S(L)-arginine. The optimized structure is shown in

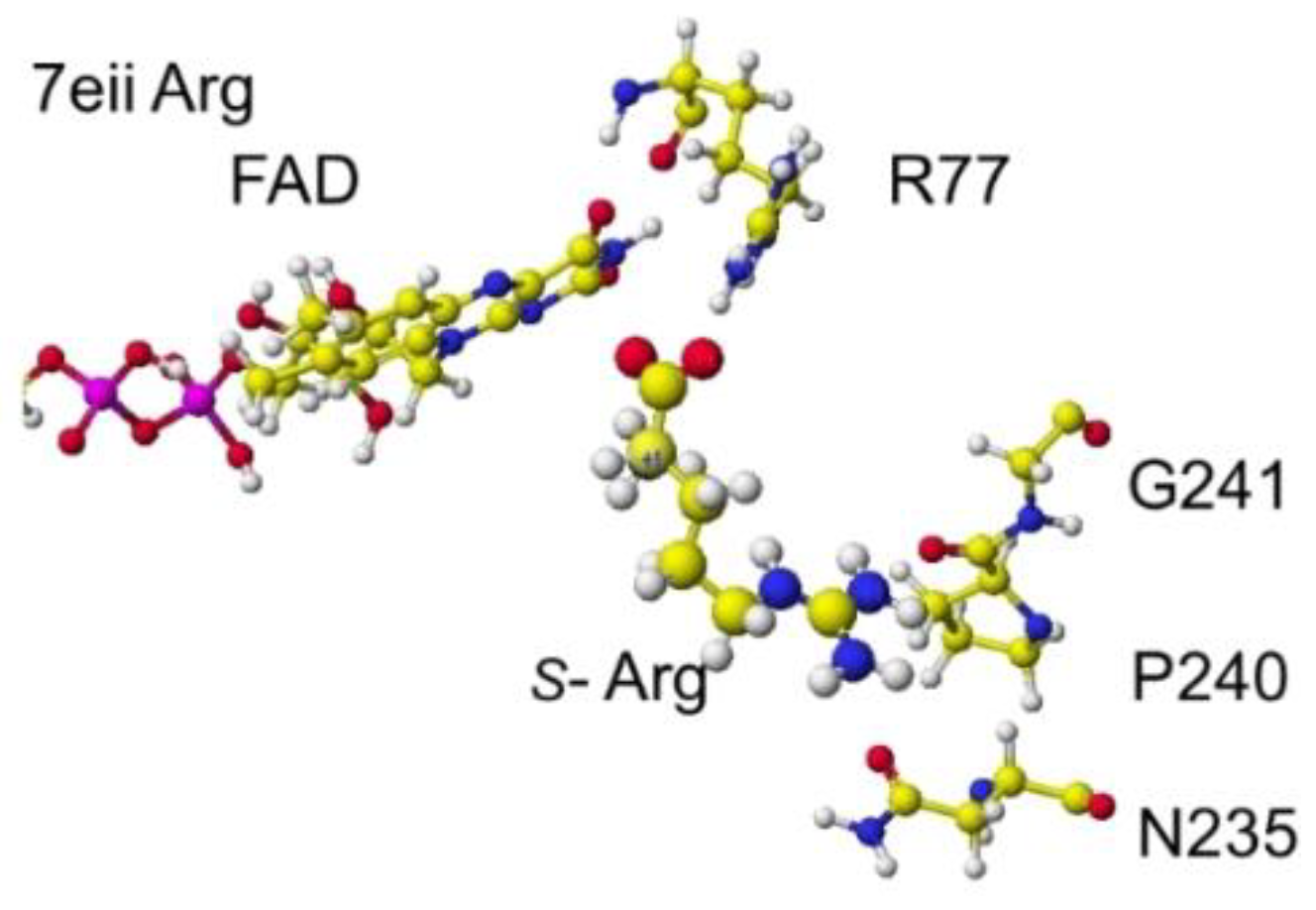

Figure 21, and the conformation around

S(L)-arginine is shown in

Figure 22.

The residual arginine a-carboxy and a-amino groups were located at 3.1 and 3.9 Å from the FAD flavine ring, respectively. The apc of a-carbon was changed from -0.263 to -0.217 au. These results indicate that the enzyme 7eii is not favorable for arginine oxidation.

3.6. Lysine Oxidase

Lysine oxidase (LOX), also known as protein-lysine 6-oxidase, is an enzyme that, in humans, is encoded by the LOX gene. It catalyzes the conversion of lysine molecules into highly reactive aldehydes that form cross-links in extracellular matrix proteins. Lysine oxidase is an extracellular copper-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the formation of aldehydes from lysine residues in collagen and elastin precursors. These aldehydes are highly reactive and undergo spontaneous chemical reactions with other lysyl oxidase-derived aldehyde residues or with unmodified lysine residues. This results in the cross-linking of collagen and elastin, which is essential for the stabilization of collagen fibrils and for the integrity and elasticity of mature elastin [

44].

The Structure of

S(L)-Amino acid oxidase/monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. AIU 813, which catalyzes both the oxidative deamination and oxidative decarboxylation of the a-group of

S(L)-Lys to produce a keto acid and amide, was determined and revealed the substrate recognition.[

45]. The kinetic characteristics of homodimer enzyme

S(L)-lysine a-oxidase from

Trichoderma, cf. aureoviride Rifai VKM F-4268D, were investigated, taking into account allosteric effects. It was a highly selective allosteric enzyme with positive cooperativity for S(L)-lysine and was responsible for the biosynthesis of 2,6-diaminopimelic acid,

S-ornithine, and

S-arginine. [

46]

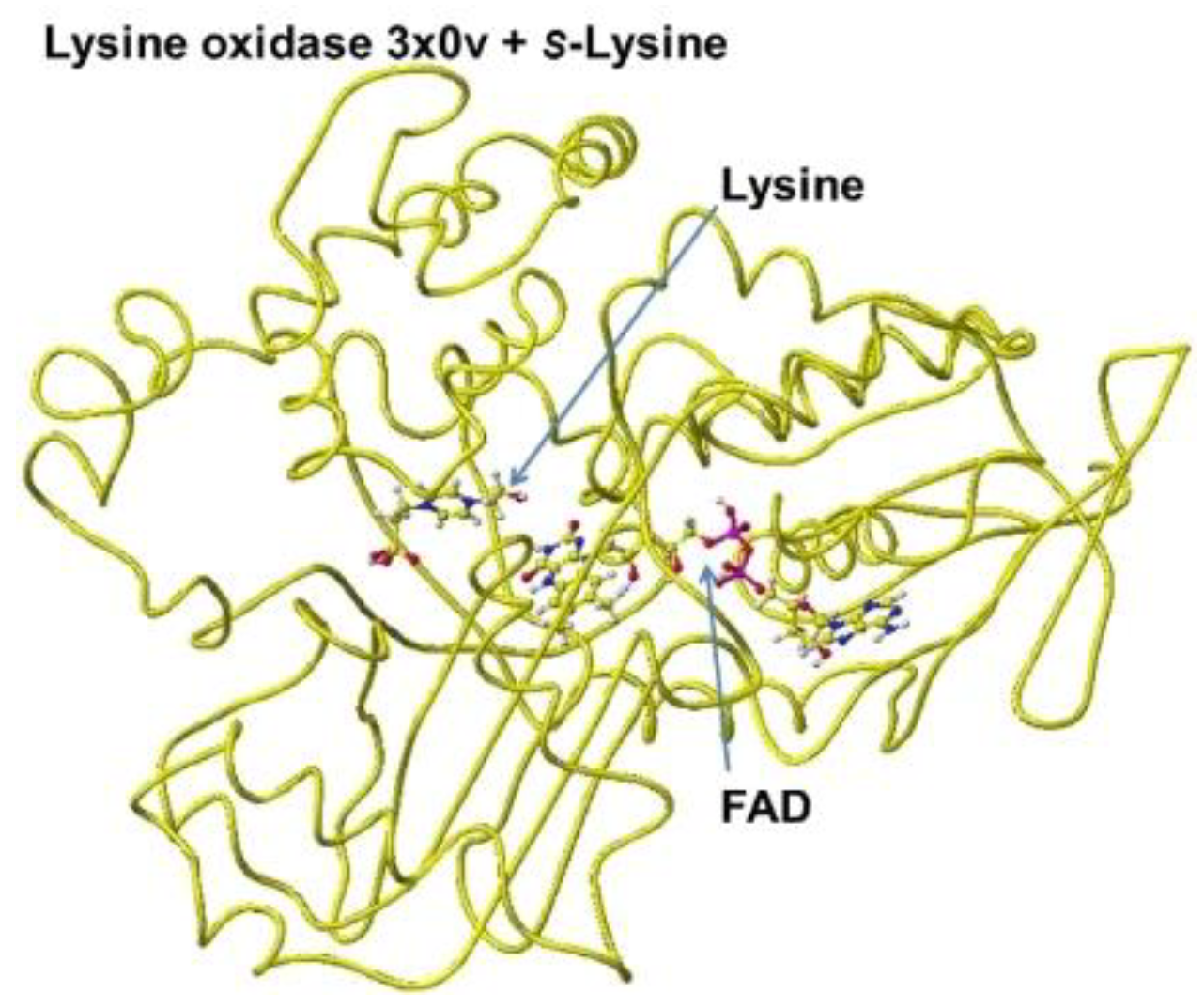

The downloaded PDB 3x0v

S(L)-lysine alpha-oxidase from Trichoderma viride does not include lysine as the substitute; therefore, the location of the lysine substitute was studied based on the results obtained for

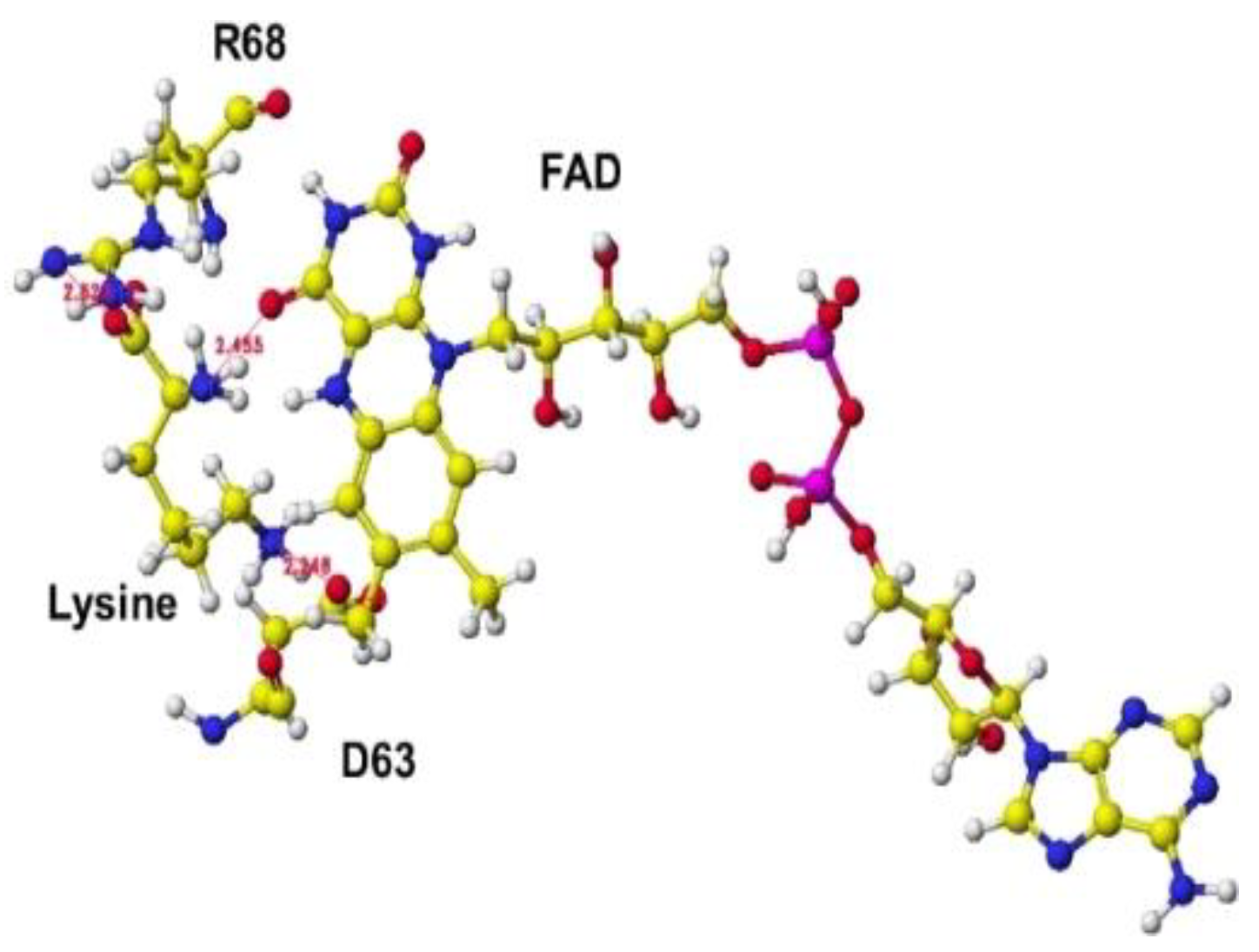

R(D)-aspartate oxidase. First, fixed the FAD structure and removed 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid. The alpha carboxy group should come into contact with a-guanidino or e-lysine amino group via strong ion-ion interaction (Coulombic force). The alpha-amino group should be located near the carbonyl group of the coenzyme flavine ring for oxidation. The e-amino group of the substitute lysine should come into contact with the carboxy group of either glutamate or aspartate of the enzyme. Finally, the carboxy group of the substitute contacted the arginine (R68) guanidino group, and the e-amino group of the enzyme contacted the carboxy group of the aspartate (D63). The complex structure is shown in

Figure 23, and the conformation details are shown in

Figure 24.

The electrons (atomic partial charge) of a-carbon of the substitute lysine shifted from -0.262 to -0.130 au. The electron localization supported the possible oxidation. The residual lysine a-amino group was 2.5Å from the FAD flavine ring, and the carboxy group was 2.6Å from the residual R68 guanidyl group. The results indicated that this enzyme is a favored in the oxidation of the lysine amino group.

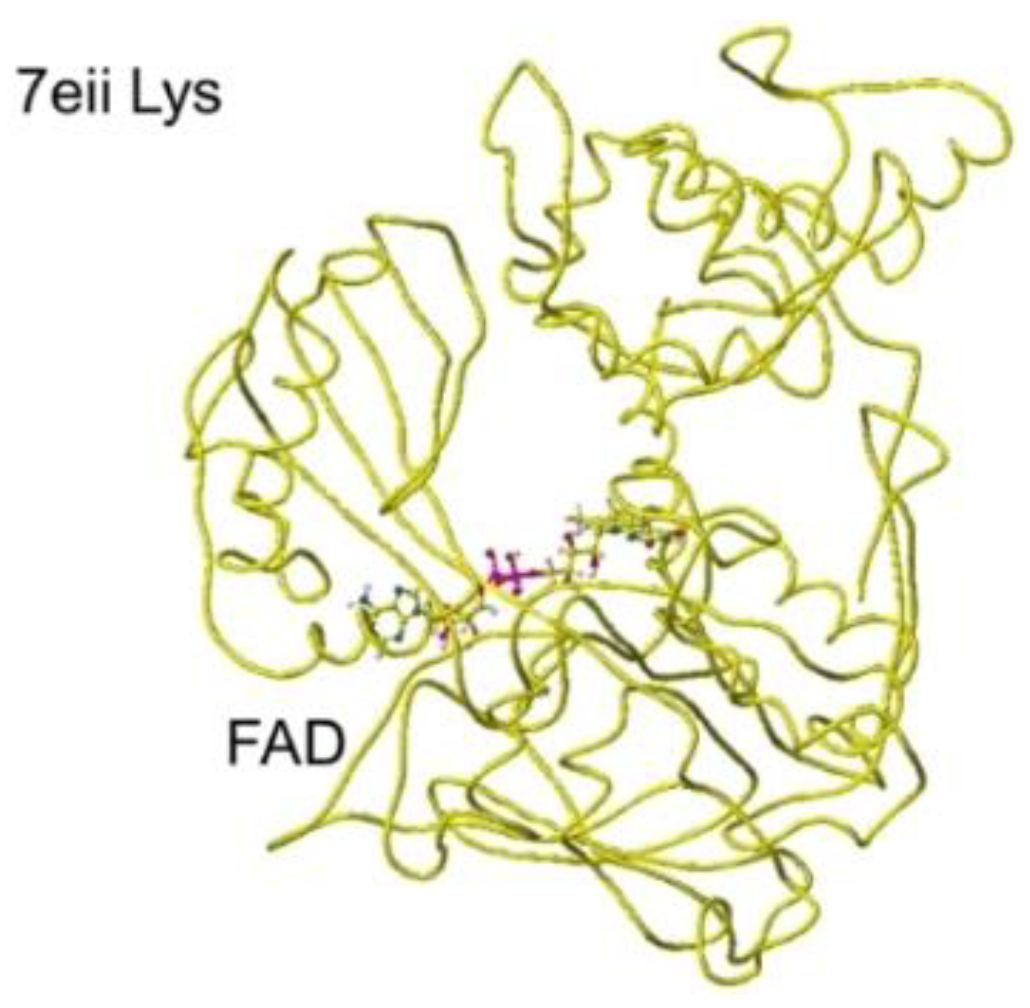

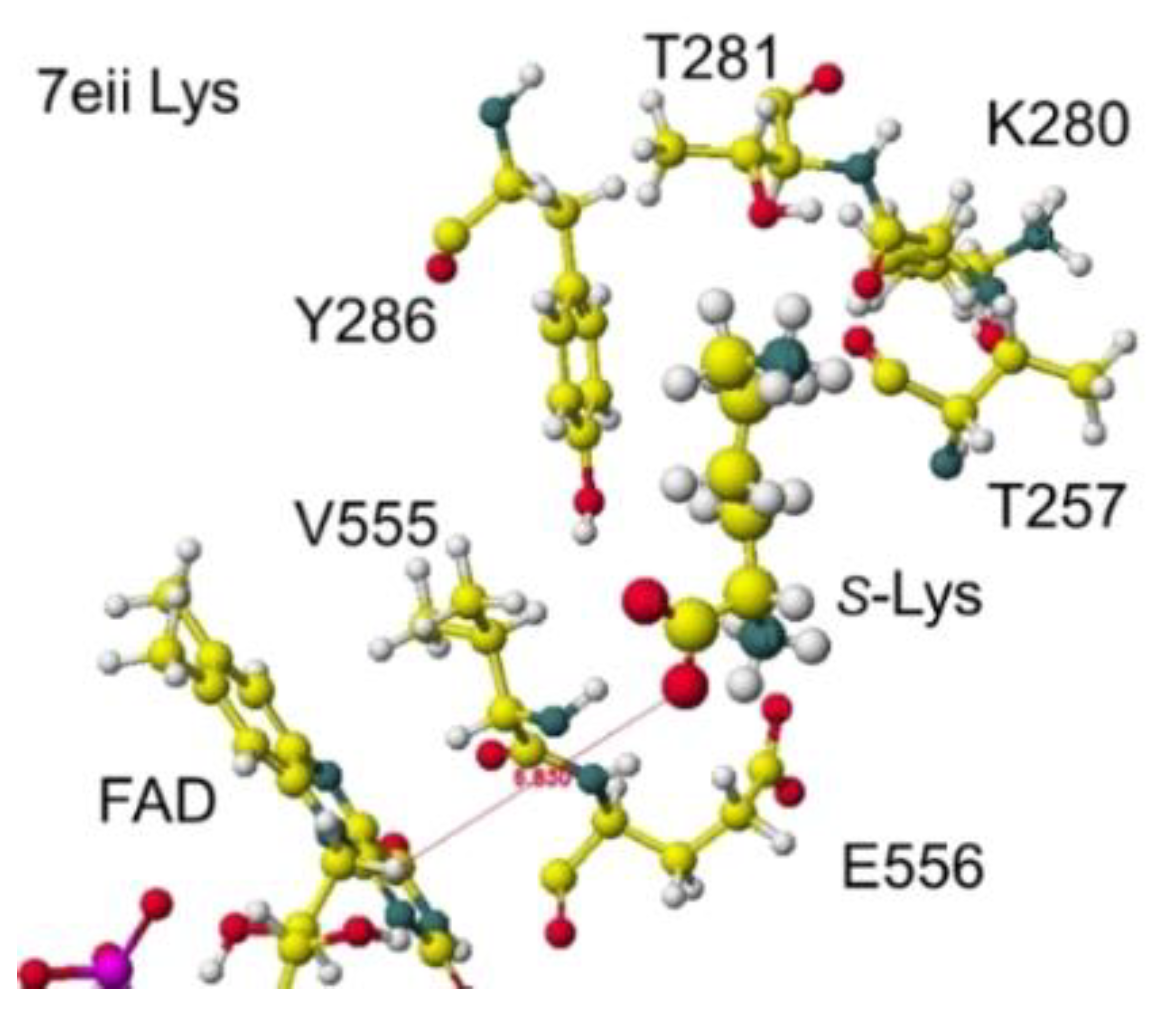

Furthermore, the ancLLys conformation was further analyzed for the comparison of results obtained for other oxidases. The structure of downloaded lysine oxidase 7eii from RSCB PDB ancestral

S(L)-Lys oxidase K387A variant with

S(L)-Lys[

46] was optimized using an MM2 program. The optimized and extracted structures are shown in

Figure 25 and

Figure 26.

The substitute S(L)-lysine a-carboxy and g-amino groups were tightly contacted with R36 and E383 via ion-ion interaction, respectively. However, the a-amino group contacted G553, Y254, and Y268 via hydrogen bonds. The Y516 intercepted the substitute S(L)-lysine, contacting with the FAD flavine ring. The a-amino and carboxy groups of substitute S(L)-Lysine were located at 5.3 and 4.6 Å from the FAD flavine ring, and the apc of a-carbon was 0.184 au. The result indicated that the diamine oxidation reaction might not occur smoothly. However, the a-amino and carboxy groups of substitute S(L)-Lysine were located at 2.9 and 3.2 Å from the FAD flavine ring before the complex optimization. Therefore, the mutation of 7eii was studied using the Y516A mutation to reduce the molecular size. The optimized conformation was the same, and the substitute S(L)-lysine was located near the FAD flavine ring. The substituent S(L)-lysine a-carboxy and a-amino groups were 3.1 and 3.8 Å from the FAD flavine ring. The result indicated that monooxygenase is the favorite reaction. Further analysis was performed on the possible R(D)-lysine oxidation based on the conformation.

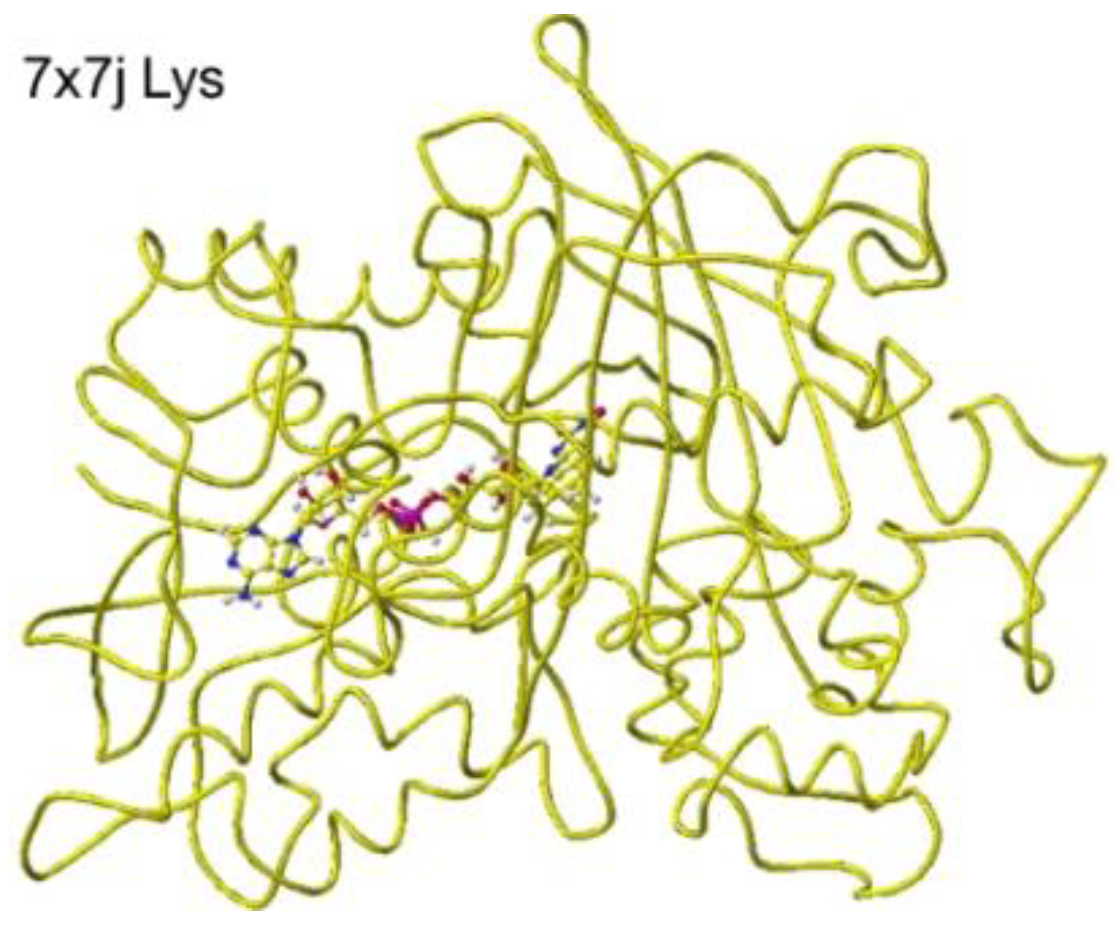

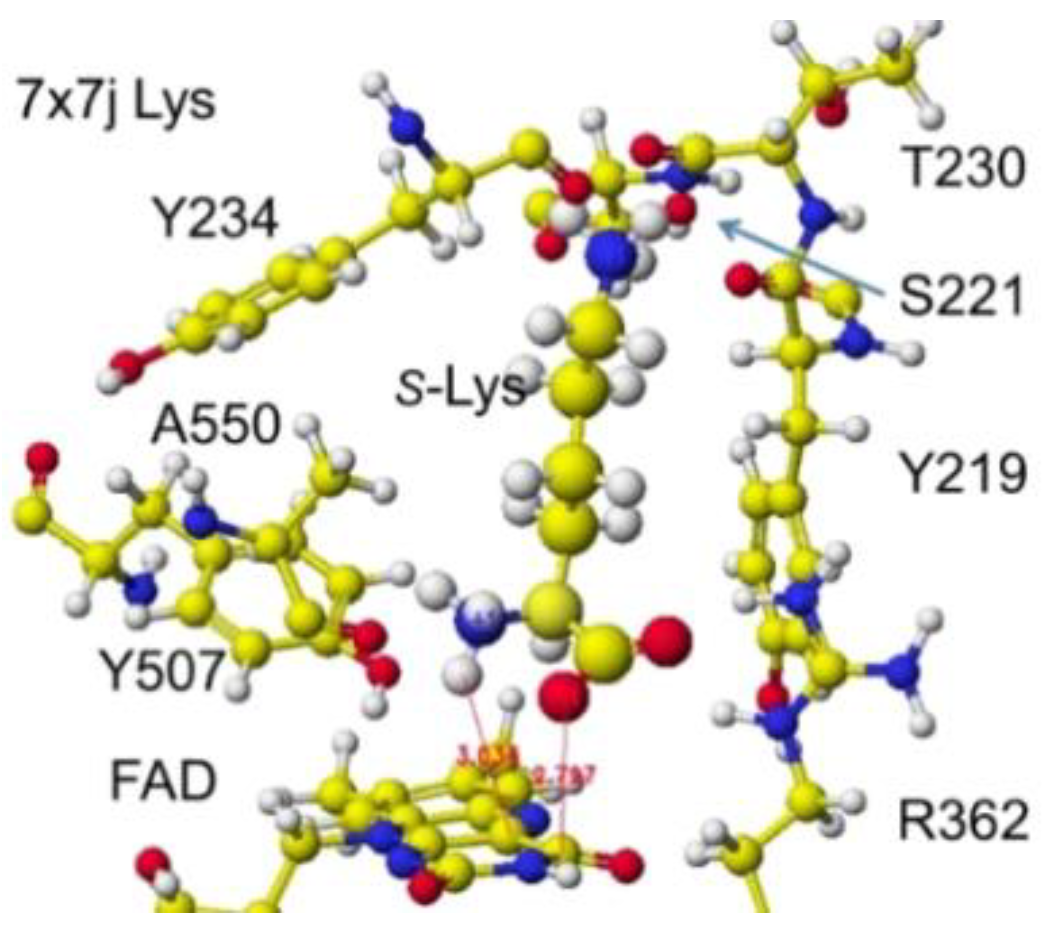

`Similar results were obtained for 7x7j ancestral lysine oxidase [

47]. The a-amino and carboxy groups of the substitute

S(L)-lysine were located at 3.0 and 2.8 Å from the FAD flavine ring, respectively, as shown in

Figure 27 and

Figure 28.

These nearest atoms were contacted together; however, the monooxygenase reactivity may be stronger than the oxidase based on the atomic distance. The apc of a-carbon was changed from -0.262 to -0.194 au. It seems that this enzyme digests more arginine than lysine. The atomic distance between the substitute lysine carboxy oxygen and the flavine ring was 2.8Å, and that between the lysine a-amino group and the flavine ring was 3.0 Å. Both oxygen and amino hydrogen contacted the flavine ring; however, monooxygenase's activity seemed stronger. The atomic partial charge of a-carbon was -0.194 au from -0.000 au.

Another anc.

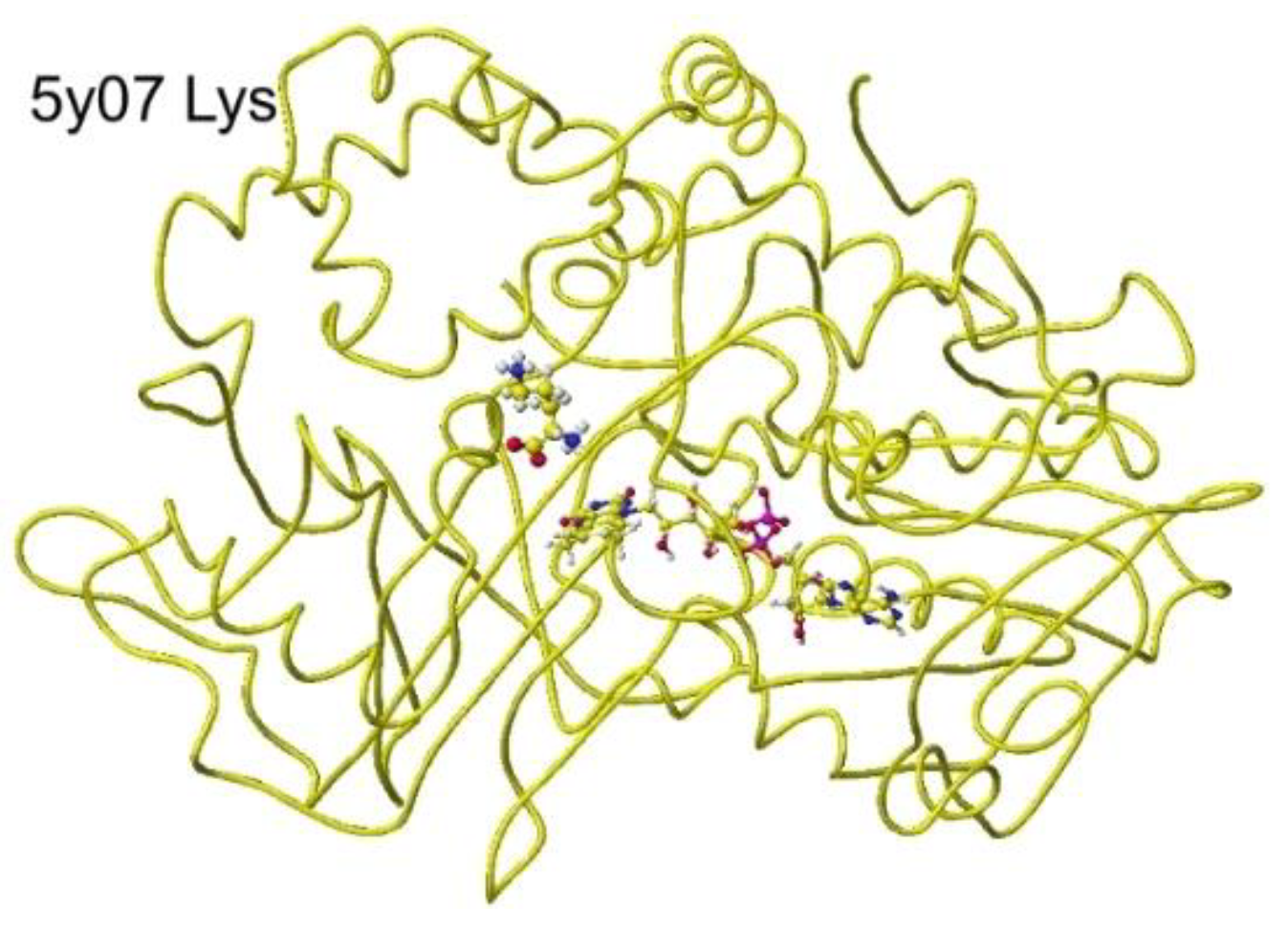

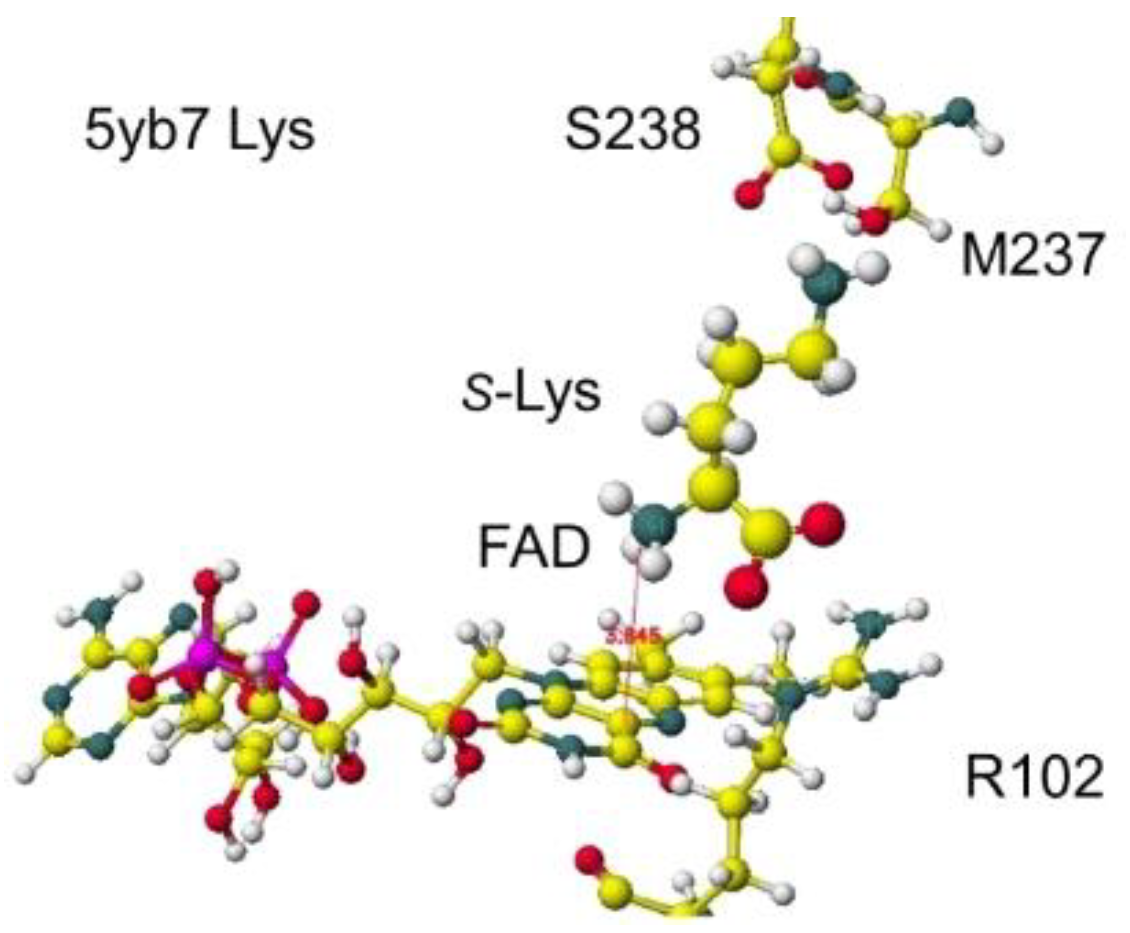

LLys was reported, and the specificity was reported. A selective

S(L)-lysine oxidase (AncLLysO2) was developed using the ancestral sequence reconstruction method, and the specificities were studied. The AncLLysO2 exhibited strong oxidase activity and high specificity toward

S(L)-Lys. [

46] The stereo structure is 5yb7 PDB of RSDB. The downloaded structure was fixed and optimized to analyze the selectivity. The conformation was analyzed by the specificity of 5yb7 lysine oxidase. The optimized structure and the extracted structures are shown in

Figure 29 and

Figure 30.

The nearest substitute arginine a-amino group was located at 3.8 Å from the FAD flavine ring. The a-carboxy group was located at 4.3 Å from the FAD flavine ring, but it contacted the residual R102 guanidyl group. The apc of a-carbon was changed from -0.262 to 0.000 au for the lysine complex, and the change was from -0.211 to 0.000 au for the arginine complex. The apc value change indicates that this enzyme is a favor for the selective oxidation of S(L)-lysine.

3.7. Glycine Amidinotransferase

HPLC analysis of guanidino compounds found a large quantity of arginine and creatine in patients' sera. If people do not take arginine and creatine as supplements, the enzyme activity of glycine amidinotransferase (GAT) and creatine kinase (CK) is weakened by poor production or third-party inhibition [

48]. The possible treatment is to dose RNA of these enzymes at the molecular level or activate these enzymes by dose suitable compounds; therefore, we have to develop a fast diagnosis of these enzymes. The approach is either the direct analysis of the enzyme activity or the analysis of the precursor and metabolite. First, we have to make clear the reaction mechanism to focus on the target compounds for the development of fast analysis.

The metabolism (reaction) mechanism from glycine to guanidinoacetate was described as the contribution of the enzyme serine355 (S355) was proposed, where the serine contacted the arginine guanidino group and the guanidino group was transferred to glycine [

49]. However, S355 hydroxy group contacts with the substrate arginine carboxy group (4JDW) [

50] and other substrates g-aminobutyric acid (6JDW), norvaline (1JDX) carboxy group contacts with the serine hydroxy group, and their amino groups are free from contact with the serine. Another proposal about the reaction mechanisms is that the glycine amino group contacts the substrate arginine guanidino group, which transfers to glycine [

50,

51]. The reaction mechanism was examined

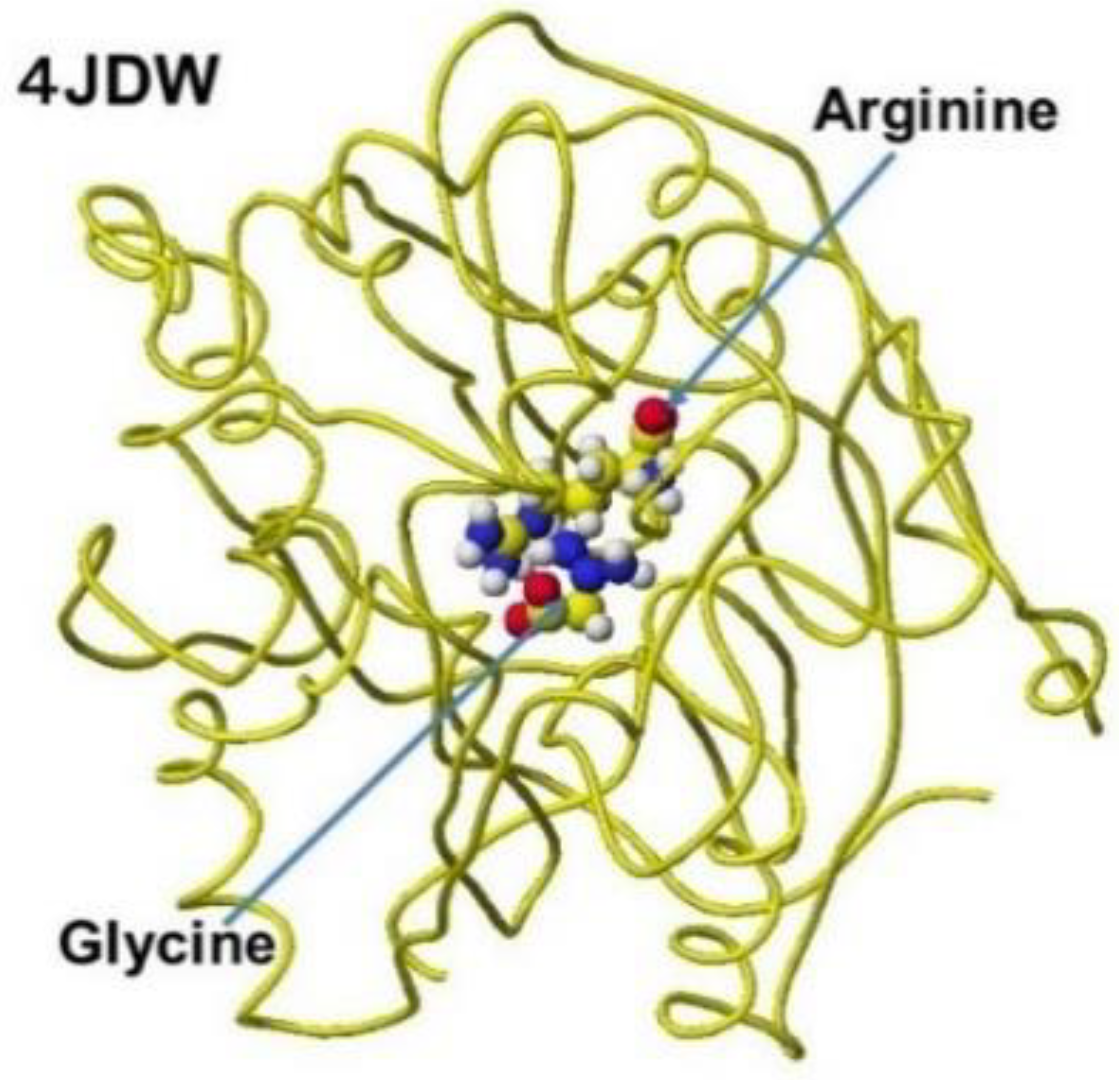

in silico using downloaded AGAT structures.

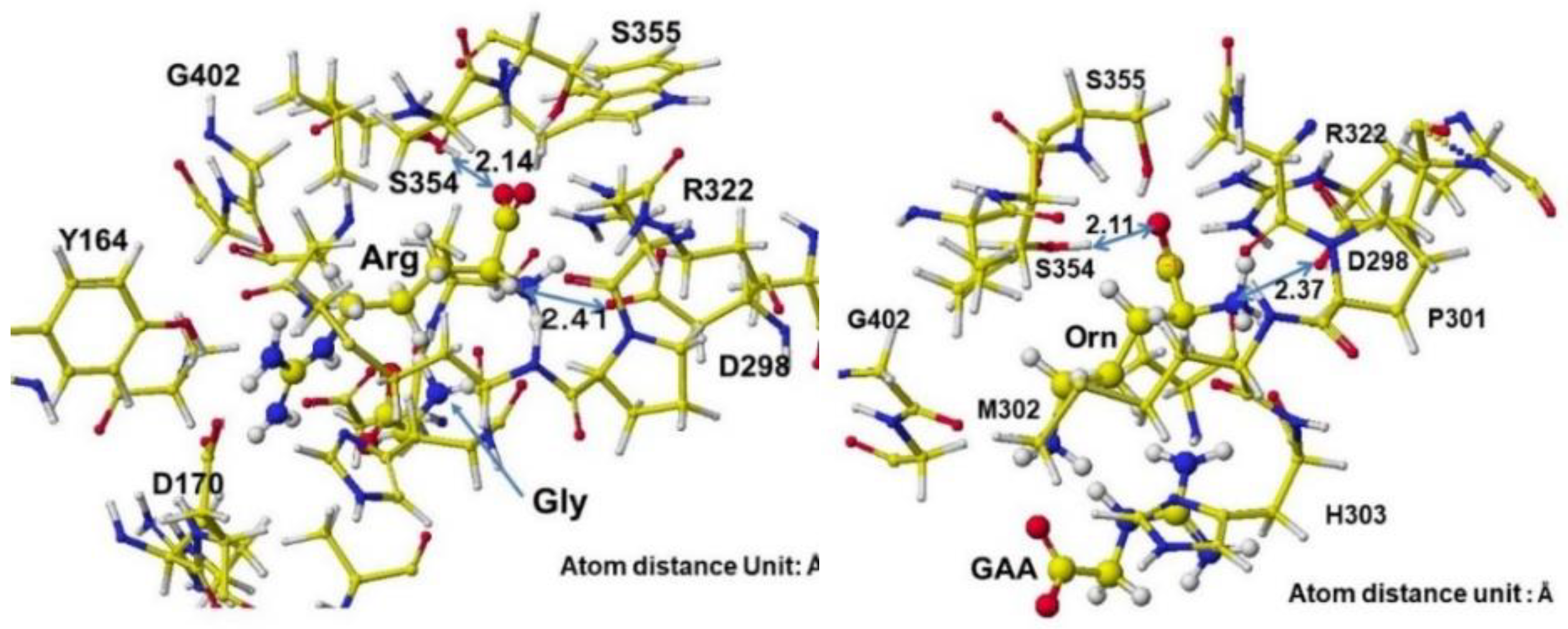

The several stereo structures of human AGAT were downloaded from the RSCB PDB, and 4JDW was chosen due to the substrate arginine. The stereo structure was corrected and optimized using a CAChe

# MM2 program. The residual amino acids within 3Å were extracted for further analysis. A glycine molecule was installed near the arginine guanidino group and optimized to study the feasibility of electron transfer from arginine guanidino to glycine. The atomic distance and apcs of target atoms support the possibility of their contact. The AGAT's downloaded, corrected, and optimized Structure (4JDW) is shown in

Figure 31, and the apcs are shown in

Figure 32. The location of arginine and glycine is indicated as their molecular form, and the protein is exhibited as a line form.

According to the AGAT enzyme reaction mechanism report, the protein's serine removes arginine's guanidino group, transfers to a glycine amino group, and produces guanidinoacetate. However, the stereo structure indicates that the carboxy and amino groups are located near the residual arginine guanidyl and serine hydroxy groups, the substrate arginine guanidino group is far from the molecular interaction site, and no serine exists near the substrate arginine guanidino group. The stereo structure indicates that the rotation of the substrate arginine is difficult

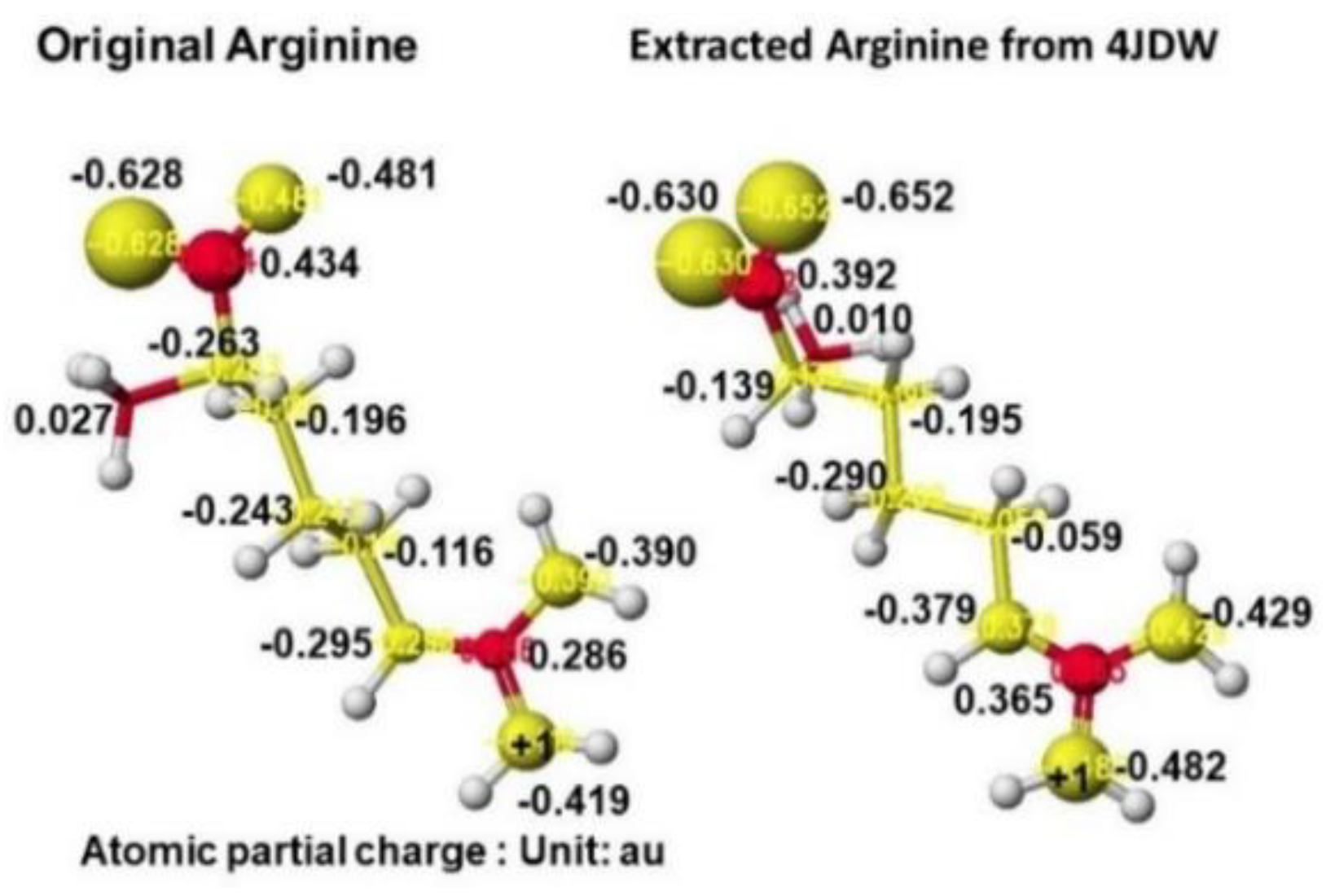

in vivo. Therefore, the electron localization of the substrate arginine before and after being trapped in the enzyme reaction center was analyzed.

Figure 33 shows the extracted conformation of substrate arginine by surrounding residual amino acids at 3Å distance from the substrate arginine. The feasibility of enzyme reactions is the same as that of chemical reactions. The localized electron of atoms near the reaction center indicates the reactivity; therefore, arginine's atomic partial charge (apc) before and after was calculated using a MOPAC PM5 program. The arginine carboxy group contacts the residual S355 and R322, and the amino group contacts the residual D298. The substrate arginine is tightly held by the residual amino acids S355, R322, and D295 and cannot be rotated inside the reaction chamber, and the guanidino group can contact glycine. The electron localization explains the binding tightness. The atomic partial charge values of target atoms shown in

Figure 33 indicate the binding center.

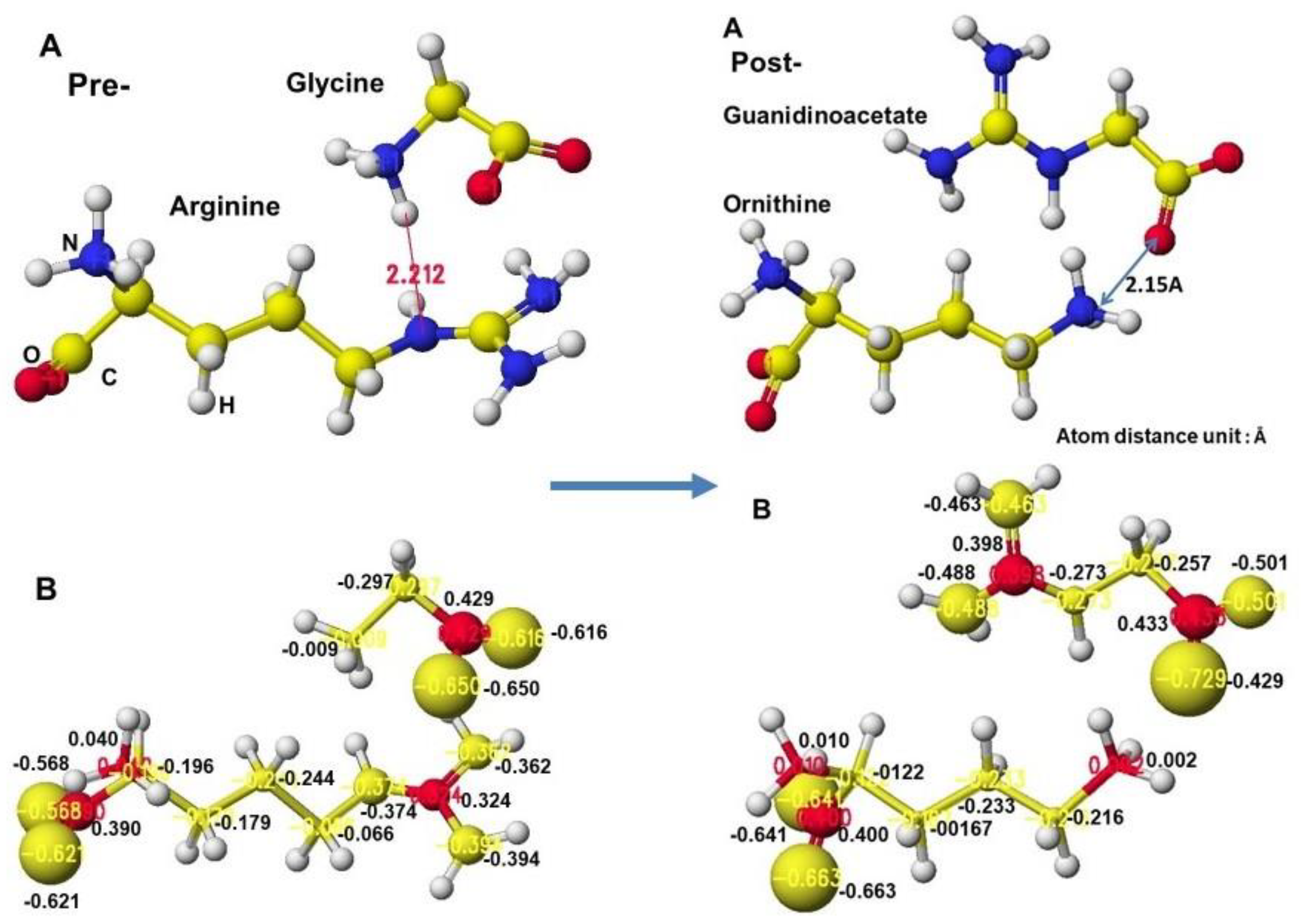

The complex structures of arginine, glycine complex, and ornithine guanidinoacetate are shown in

Figure 34. Initially, glycine tightly contacts the arginine guanidino group (

Figure 34 Å Pre), and the arginine guanidino group is transferred to the glycine amino group; then, the arginine is converted to ornithine, and the glycine becomes guanidinoacetate. The electron localization is shown in

Figure 34B. The atomic partial charge change indicates their contact center and the feasibility of the reaction.

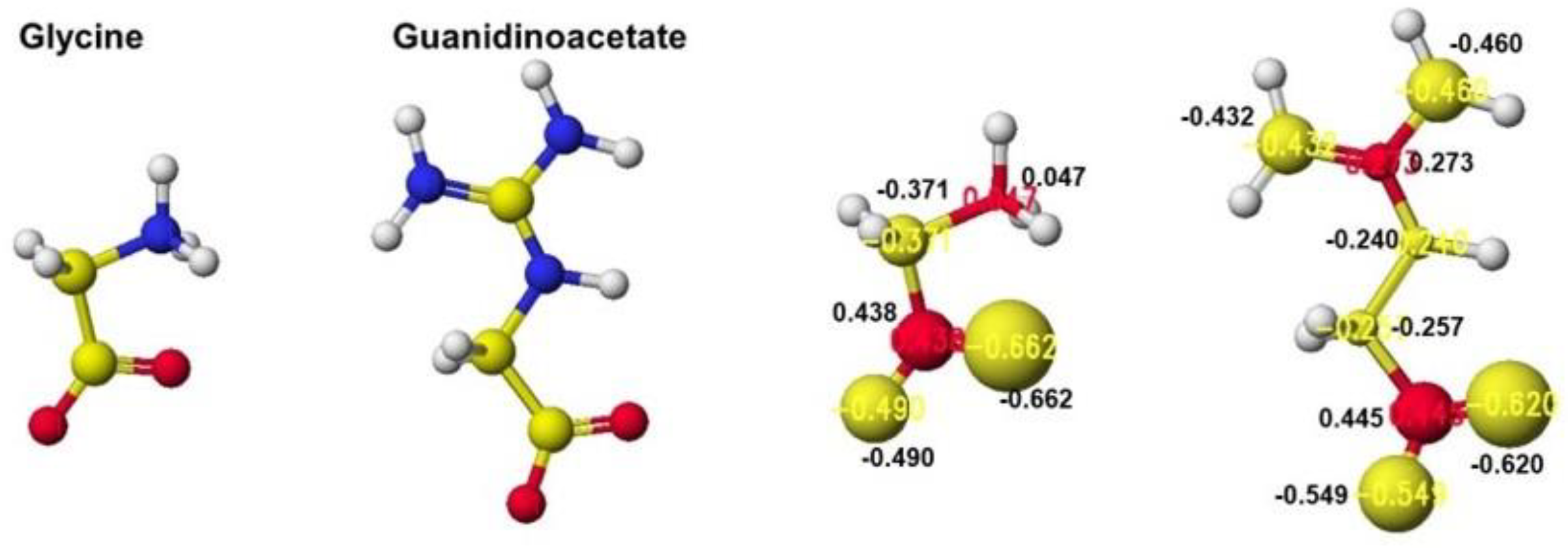

Figure 35 exhibits the original structure of glycine and guanidinoacetate with the atomic partial charge of heavy atoms to make clear the reaction center.

The apc values of the substrate arginine carboxy oxygen are -0.628 and -0.481, and those held by the enzyme are -0.652 and -0.630 au; the strong negative values are recovered a little by forming the complex with glycine. The apc value of guanidino carbon is changed from 0.286 to 0.365 au by the folding and a little recovered by the complex formation to 0.324 au.

The reactivity is also understood from the apc value changes of glycine and guanidinoacetate. The apc values of glycine carboxy oxygen atoms change from -0.490 and -0.662 to -0.616 and -0.650 au. Those guanidinoacetate carboxy oxygen atoms change from -0.620 and -0.549 au to -0.724 and -0.501 au. Such a conformation analysis and apc value change make clear the reaction center and the enzyme selectivity [

1].

The enzyme reaction converts glycine to guanidinoacetate; therefore, glycine is required as the precursor. Dosing glycine is one treatment method, and the second step is dosing RNA to increase the amount of AGAT. If the activity of amino acid oxidase or D-amino acid oxidase is too high, we shall dose the inhibitor to keep glycine content constant. The analysis of glycine is also a target of diagnosis. If an inventor damages the enzyme activity, we should use antibiotics and antiviral drugs to kill viruses and bacteria. First, we need a precise diagnosis that clearly indicates personal enzyme activities.

3.8. Guanidinoacetic Acid N-methyl-transferase

HPLC analysis of guanidino compounds found a large quantity of arginine and creatine. If people do not take arginine and creatine as supplements, the enzyme activity of glycine amidinotransferase (GAT) and creatine kinase (CK) is weakened by poor production or third-party inhibition. A possible treatment is to dose RNA of these enzymes at a molecule-level reproduction or activate these enzymes by dose suitable compounds. Therefore, we need to develop a rapid diagnosis for these enzymes. In the metabolic process, guanidino acetic acid N-methyltransferase is a key enzyme, and the reaction mechanism is visualized even if this enzyme activity is not a biomarker.

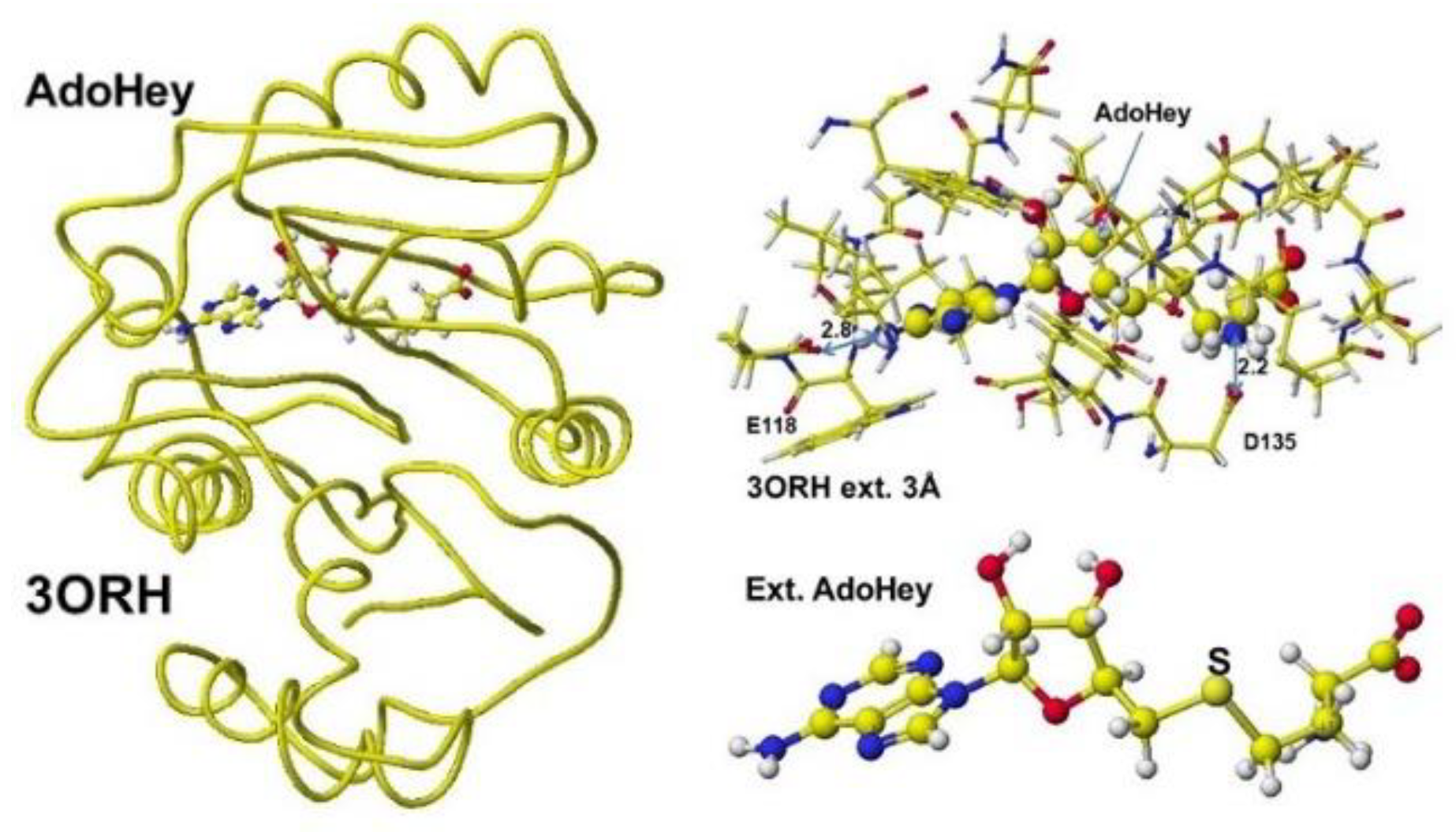

The enzyme reaction mechanism can be analyzed using the enzyme stereo structures. The stereo structure of these human enzymes is stored in the RSCB PDB. Therefore, the enzyme reaction mechanisms are analyzed using downloaded protein structures after correction, especially for the substitutes. Previously, the reaction mechanisms of glycine amidinotransferase (GAT) were analyzed (VisualizationXXIII). Both inborn errors and disease damage enzyme activity. Early oral dosing of creatine can normalize inborn error patients [

52], and the weakened GAT activity is determined by analyzing guanidinoacetate (GAA) in urine and serum; however, one-spot analysis is affected by personal lifestyle and requires a balanced analysis of metabolites. The following enzyme after GAT is guanidinoacetate

N-methyltransferase, which metabolizes guanidinoacetate to creatine. The coenzyme is

S-adenosyl methionine (AdoMe), whose

S-methyl group is transferred to the guanidinoacetate guanidyl group. A human guanidino

N-methyltransferase is downloaded from the PDB (3ORN), including

S-adenosyl-

L-homocysteine (AdeHey). The optimized structure, extracted Structure of AdoHey with residual amino acids within 3Å, and extracted AdoHey structures are shown in

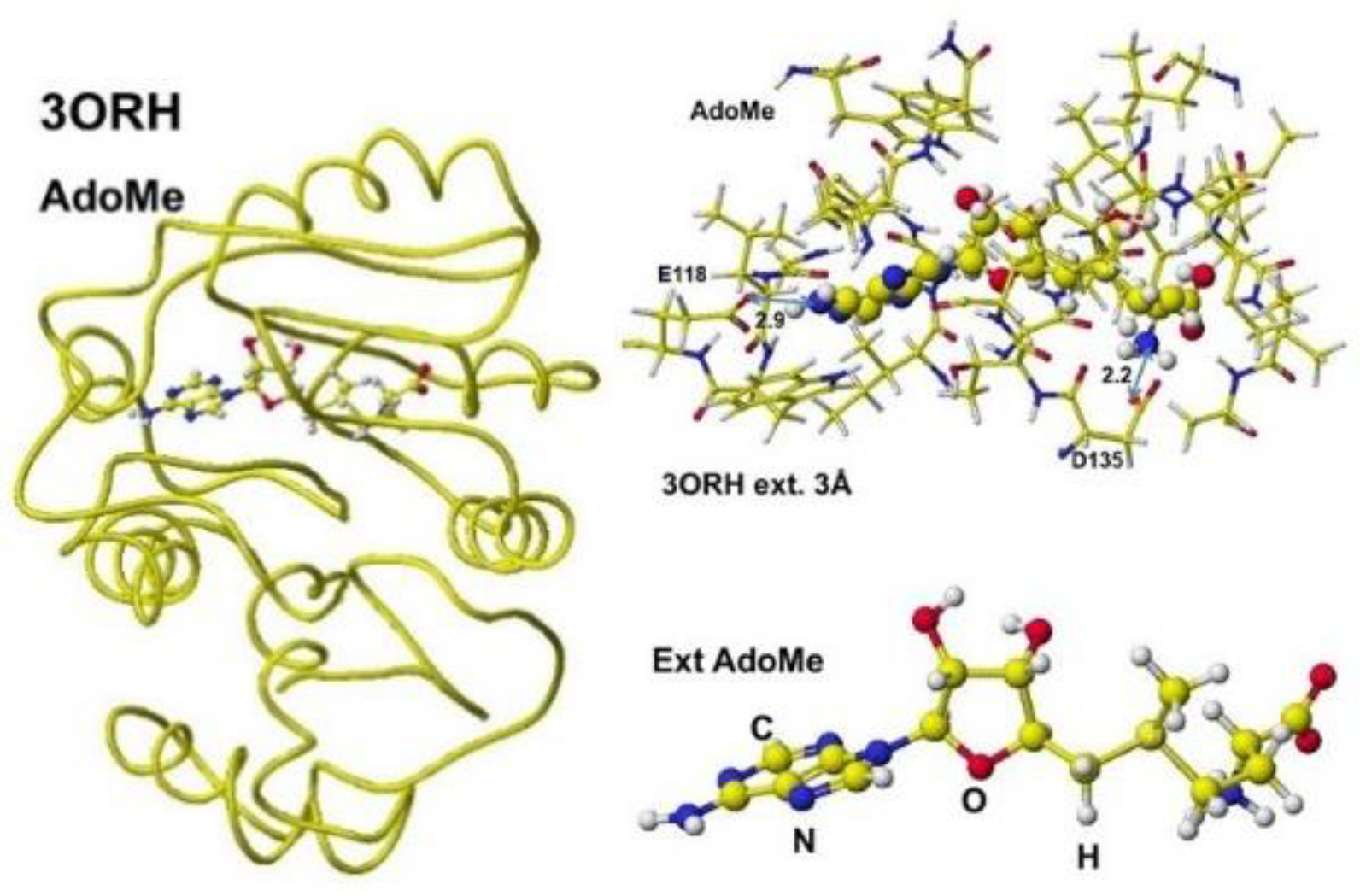

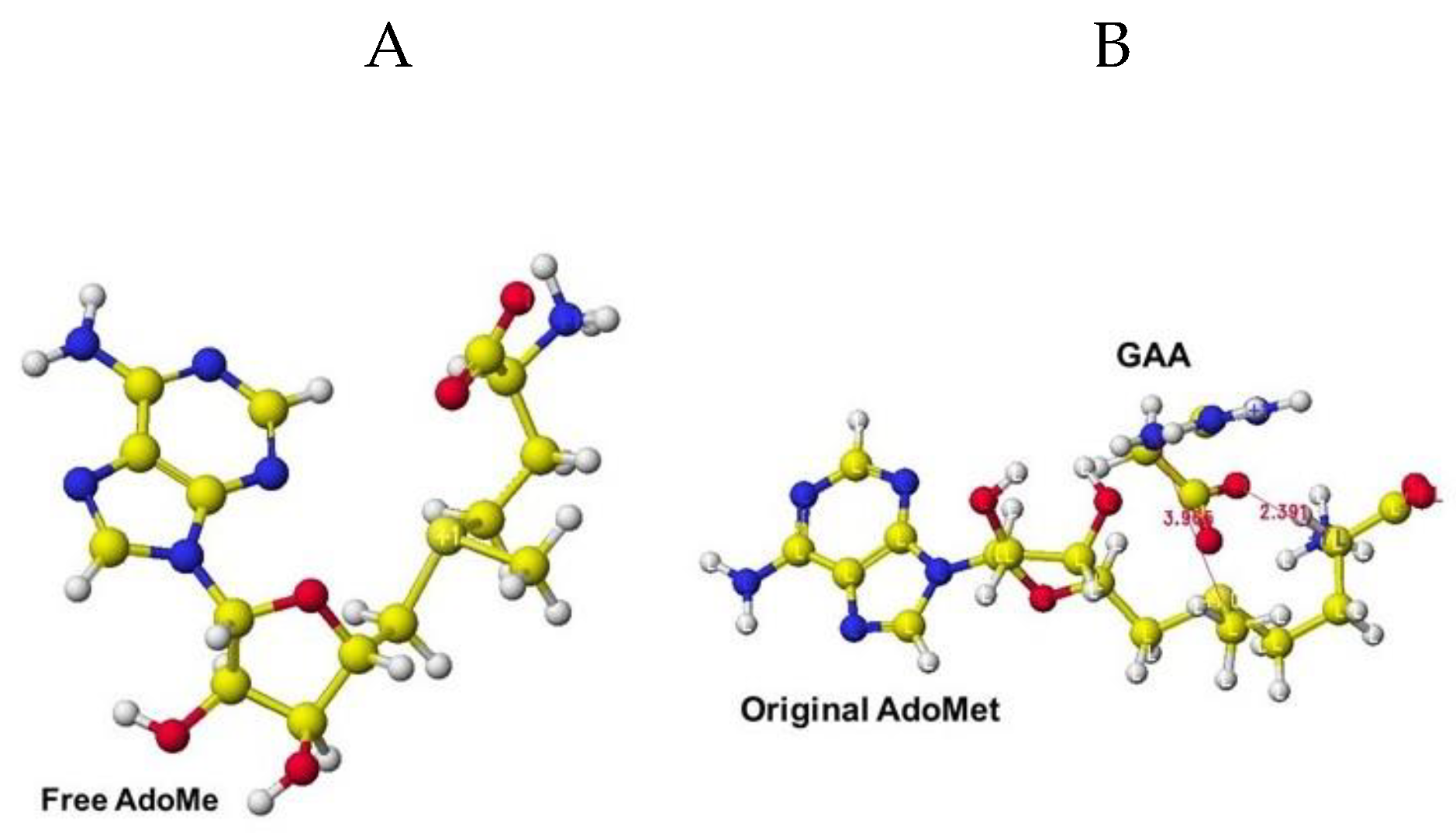

Figure 36. The AdoHey carboxy group binds with the Aspartic acid (D135) carboxy group via ion-ion interaction; the atomic distance between the amino nitrogen and carboxy oxygen is 2.2Å. AdoHey adenosine amino group binds with glutamic acid (E118) carboxy group; the atomic distance between the nitrogen and oxygen is 2.9Å. These bonds keep the AdoMe and AdoHey structure straight. The atomic partial value of the key atom sulfur changed from 0.869 to 0.914 au, and that of the methyl group carbon changed from -0.447 to -0.572 au by electron localization.

First,

S-adenosyl-

L-homocysteine is converted to

S-adenosyl methionine, a guanidinoacetate is inserted, and the chemical structures are corrected. The optimized complex structure is shown in

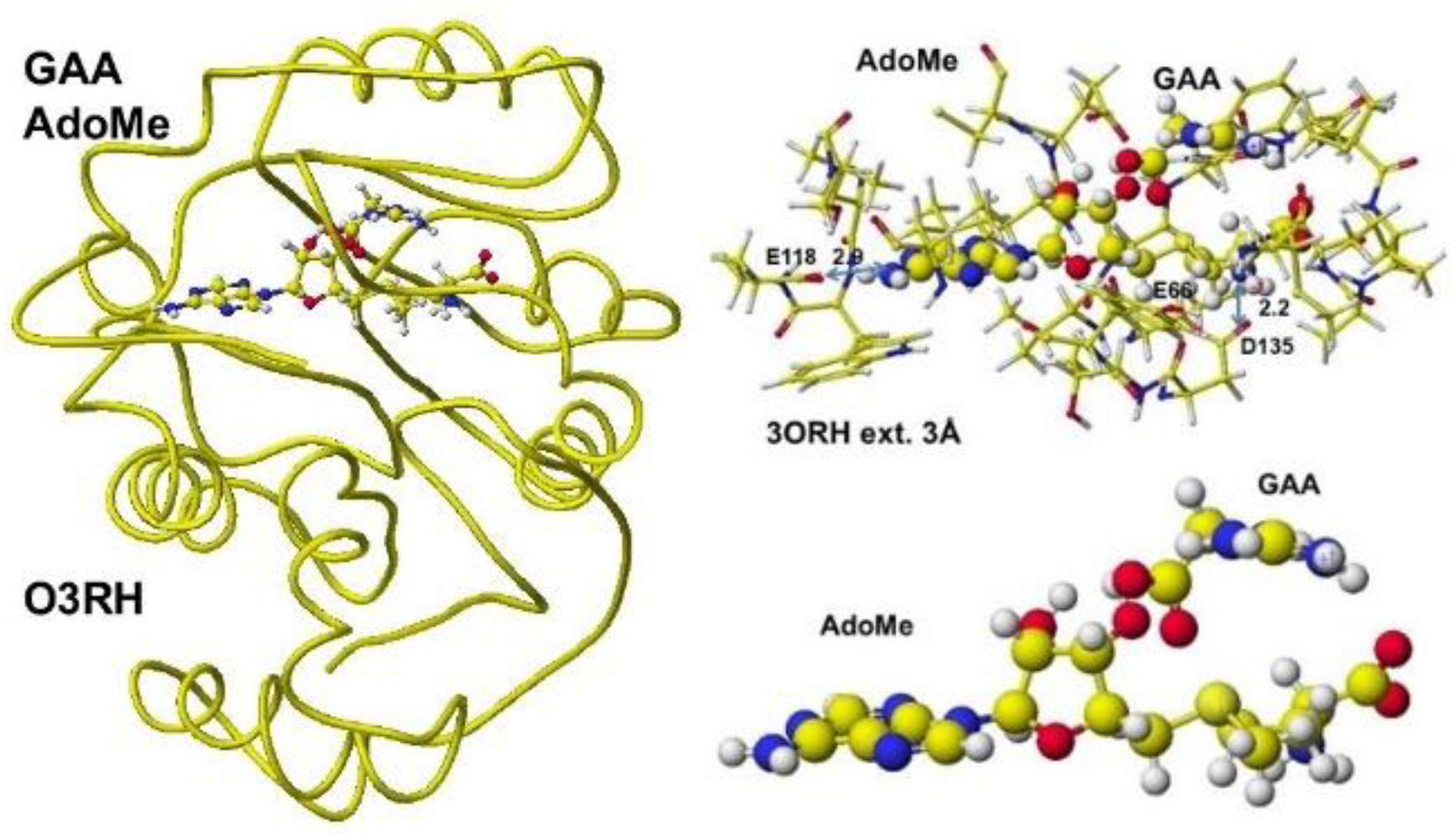

Figure 37, including residual amino acids within 3Å from AdoMe and extracted AdoMe. The holding of AdoMe inside the enzyme is the same as that of AdoHey. Insert GAA; then, the complex structure is optimized. The GAA carboxy group contacts the AdoMe sulfur. The construction of the transition state from GAA to creatine is difficult inside an enzyme. Therefore, the docking of creatine with AdoHey is performed by the insertion and the whole structure optimization. The result is shown in

Figure 38, including an extracted conformation with residual amino acids with 3Å from AdoHey. The optimized structure of Guanidinoacetic acid

N-methyltransferase with

S-adenosyl-

L-homocysteine and creatine complex, the extracted conformation and

S-adenosyl-

L-homocysteine, and creatine complex is shown in

Figure 39.

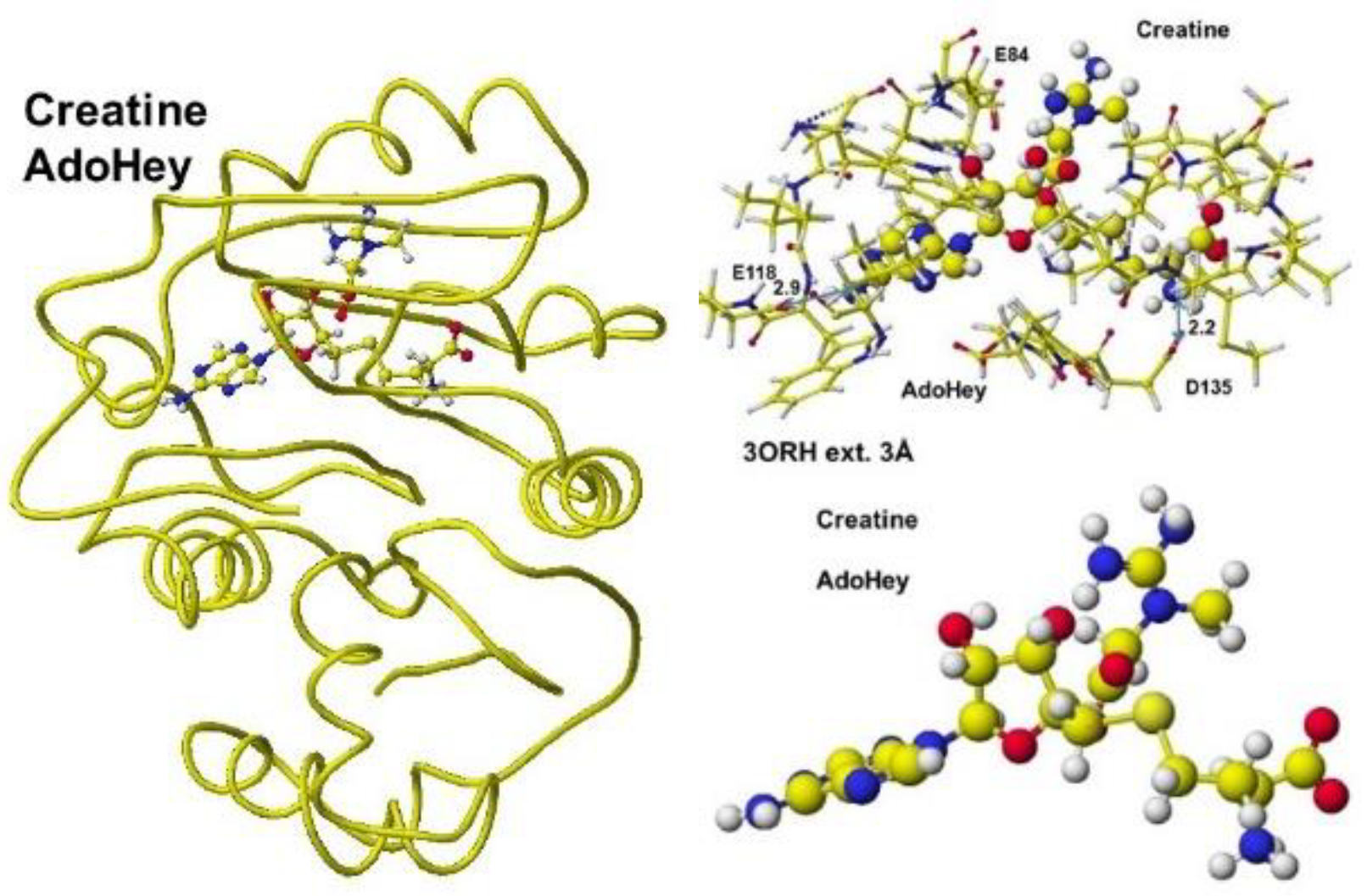

The extracted and modified AdoMe is bent outside the enzyme after the optimization, as shown in

Figure 40A. Therefore, the docking process is not automated, and guanidinoacetate and creatine are carefully inserted into and optimized complex structures. Guanidinoacetate and creatine carboxy group bind with

S-adenosylmethionine and

S-adenosyl-

L-homocysteine amino group

in vitro (

Figure 40B), but the amino group already binds with the residual amino acid carboxy group

in vivo; therefore, the guanidinoacetate and creatine carboxy group locate near the sulfur atom of these coenzymes.

Chronic kidney disease is crucial, and resistance exercise can improve patient health; however, guanidinoacetate was not a diagnosis target [

53]. This reaction, converting from guanidinoacetate to creatine, requires the reaction cofactor

S-adenosyl methionine. Therefore,

S-adenosyl methionine is one drug candidate. If an inventor damages the enzyme activity, we must kill viruses and bacteria using antibiotics. We need a presided diagnosis that indicates personal enzyme activities.

3.9. Creatine Kinase

One of the biomarkers of diagnosis in kidney disease is creatine kinase, which metabolizes creatine to creatine phosphate, which is automatically metabolized to creatinine [

48]. Therefore, creatine kinase activity can be determined by the concentration ratio of creatine and creatinine. Creatine is taken as a supplement, and the concentration in serum is affected by personal lifestyle; therefore, measurement of the balanced amount of creatine and creatinine is necessary to determine the individual health condition.

Several stereo-structures of human creatine kinase were downloaded from RSCD PDB and corrected the structures, then optimized using an MM2 program. Human brain creatine kinase PDB 3DRB [

54] includes ADP, Mg, and nitrate; however, human brain creatine kinase 3DRE contains (-)-7-[(6-chloro-2-naphtalemyl)-1'-(pyridinyl)-spiro[5H-oxazolo[3,2-a]pyrazine-2(3H), 4’-priperidin]-5-one instead ADP even though the report indicates ADP as a cofactor. It seems that the stereo structure of 3DRE[

54] is deformed; therefore, the stereo structure of human creatine kinase PDB 7TUN [

55] is used as the standard structure after comparison with other human creatine kinases. An initial complex conformation with cofactors is critical for optimizing the complex structure; therefore, the PDB 4RF9 [

56] structure is used as a reference structure.

Human sarcomeric mitochondrial creatine kinase 4ZPM includes ADP and uranium and has 72.4% similarity to human brain creatine kinase 7RUN and T. Californica Creatine Kinase PDB 1VRP, containing ADP, guanidinoacetic acid, magnesium, and nitrate [

57], has 89.3% similarity to 7TUM, and their secondary structures are identical. Therefore, 7RUM is used as the standard for human brain creatine kinase, and 1VRP is used for further analysis to visualize the human creatine kinase reaction mechanism. Therefore, the location of ATP and ADP is carefully managed by comparison of several crystal structures. First, 1VRP ADP is converted to ATP following the stereo structure of Anthoplasma PDB 4RF9 [

58], and the residual amino acids of 1VRP are replaced with the residual amino acids of 7TUM. The mutation process is the same as that created by a human

D-amino acid oxidase from the East

D-amino acid oxidase.

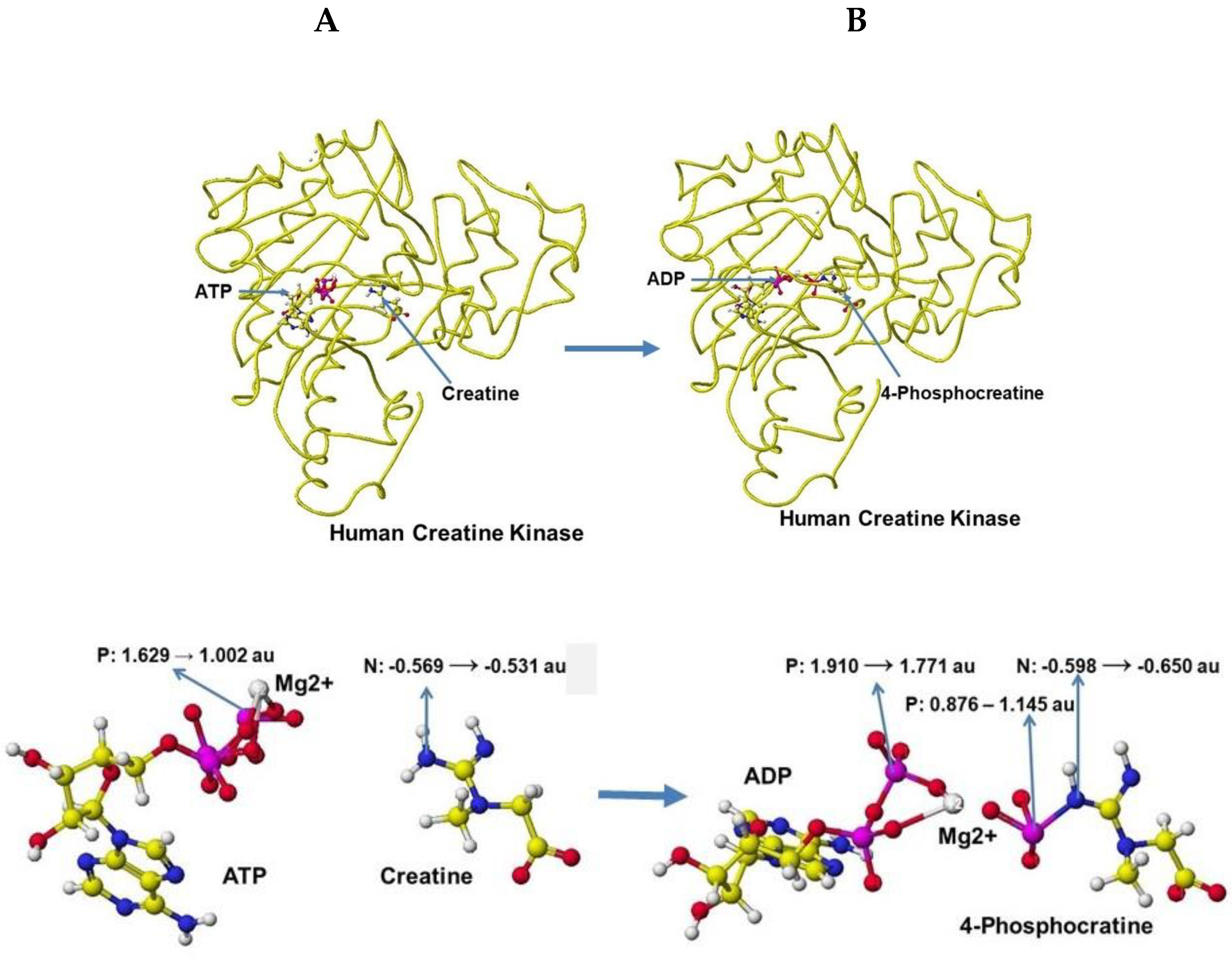

The optimized stereo structure of human brain creatine kinase is shown in

Figure 41A. An ATP, a creatine molecule, and an ionized magnesium (2

+) are included in the stereo structure. Some magnesium binds the hydroxy groups in reference structures, but the magnesium binds only the phosphate oxygen in these structures. Magnesium has a crucial role in ATP activity [

59,

60], binds with three phosphate oxygens, and the magnesium moves to bind with two remaining phosphate oxygens after releasing one phosphate to creatine. After releasing one phosphate to convert creatine to creatine phosphate, ATP is converted to ADP. An optimized stereo structure of human creatine kinase with ADP and creatine phosphate is shown in

Figure 41 B.

The apc of ATP g-phosphorus is changed from 1.529 to 1.002 au by the existence of creatine, and the apc of creatine nitrogen is increased from -0.569 to -0.531 au. The induction of the electron contributes to the molecular interaction. The phosphorus transport of ATP to creatine, which produces 4-phosphocreatine can also be explained by the change of apc values of key atoms. The b-phosphorus apc value is changed from 1.910 to 1.771 au, and that of the previous g-phosphorus of ATP is changed from 0.876 to 1.145, and that of nitrogen of 4-phosphocreatine is changed from -0.598 to -0.650 au. The optimization of chemical structure using the MM2 program to calculate molecular interaction energy and the MOPAC PM5 method to calculate electron localization makes the enzyme reaction mechanisms clearer.

Visualizing enzyme reaction processes helps understand the reaction mechanisms, develop diagnosis methods, and design medicines. The last three reports visualize the biomarker reaction processes of kidney disease and propose possible clinical analysis targets. The biomarkers are arginine transferase and creatine kinase, and the measure of these enzyme activities can be determined by the relative values of arginine and guanidinoacetate and that of creatine and creatinine. Furthermore, the enzyme reaction that activates compounds and increases the enzyme mass by RNA is the medicine candidates. ATP and ADP are unstable compounds; therefore, their precursors are potential medicine candidates, and further modification can provide more friendly medicines. Furthermore, in the critical subject of our aging society, the early identification of biomarkers of growing senile people and dose drugs to help MIBYO people, pre-dementia patients.

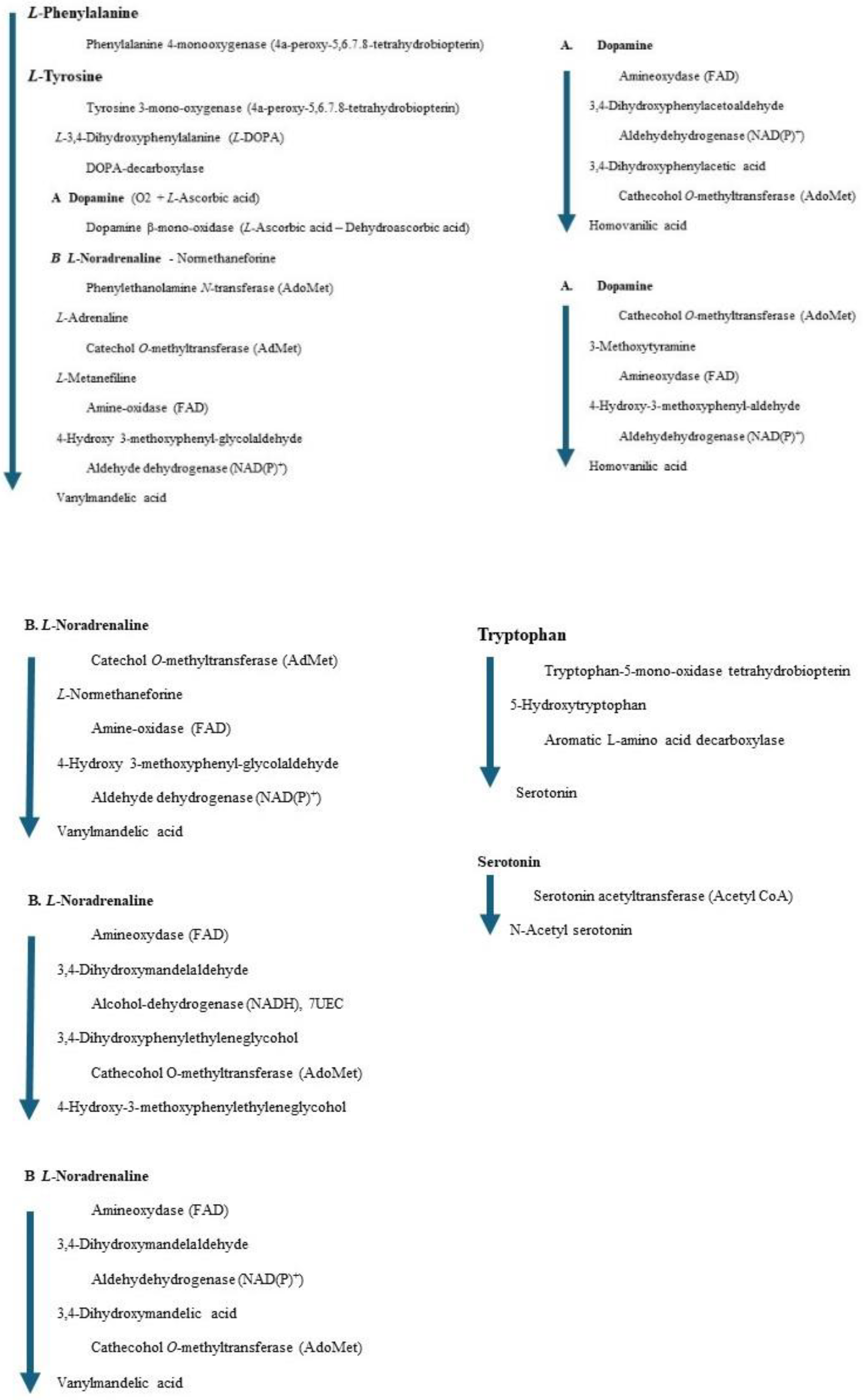

3.10. Complex Metabolism of Aromatic Amino Acids

While our metabolisms are normal, we are healthy; however, when some are injured for unknown reasons, and damage our health. The damaged metabolism, characterized by a weakened enzyme, can be identified through analysis of normal metabolism. The precursor-to-metabolite ratio indicates personal health condition, and a weakened enzyme is a biomarker for the diagnosis target. We should develop a quick and mass analysis method for general use, and furthermore, create new drugs. One target is to identify senile dementia persons (MIBYO persons) before their actual dementia patients in our aging society. The key molecules for communication are catechol amines and serotonin; these are metabolites of aromatic amino acids that our body cannot synthesize.

The phenylalanine metabolism is very complex, and several enzymes and coenzymes (cofactors) act for similar reactions. The total number of enzymes is less than the total number of metabolites; therefore, the weakened one enzyme affects the total balance of metabolisms. A chromatogram may indicate a large quantity (storage) of several metabolites; however, the biomarker is one enzyme. We also should measure the amount of coenzyme to normalize the metabolism. The following Figures indicate the metabolites and enzymes that these reactions will be visualized.

3.10.1. Human Phenylalanine -4-monooxygenase (Phenylalanine Hydroxylase)

The deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase causes phenylketonuria. The toxic effects of accumulating phenylalanine metabolites cause severe mental retardation [

60,

61,

62,

63]. Therefore, the measurement of phenylalanine hydroxylase activity is a common diagnosis. Phenylalanine hydroxylase catalyzes the hydroxylation of

L-phenylalanine to

L-tyrosine. The reaction is described in the following equation [

64,

65].

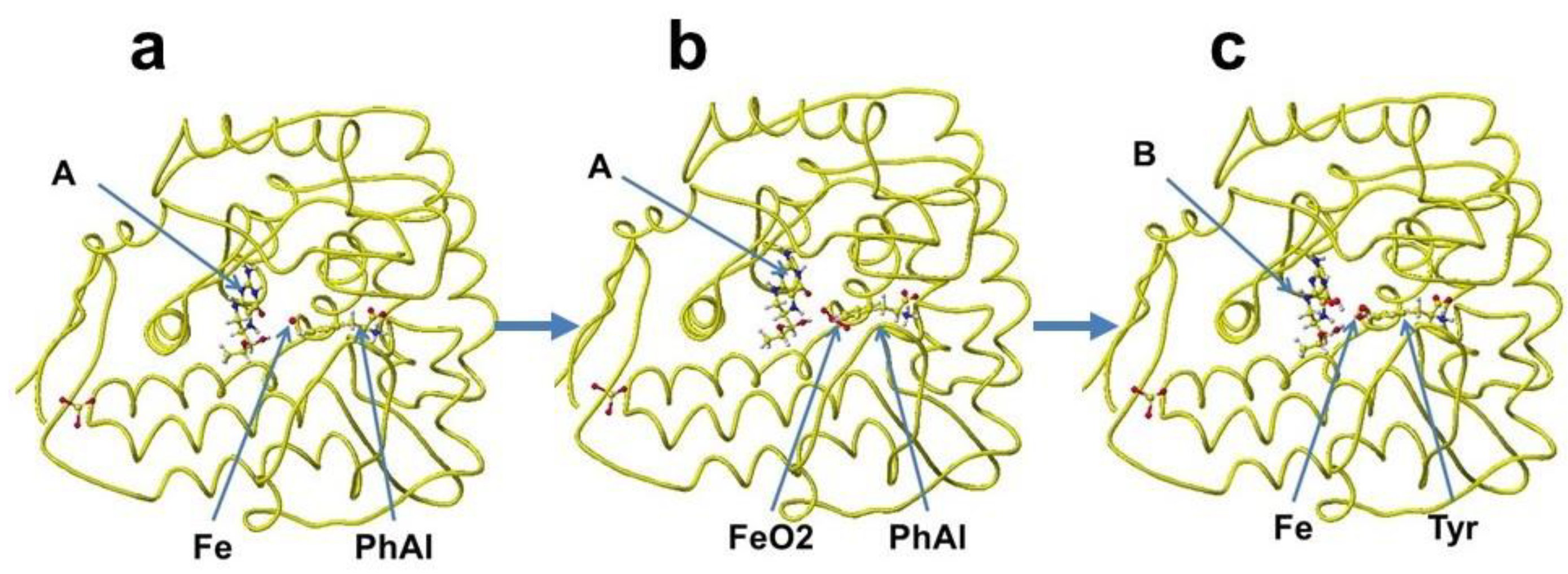

(6R)-L-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahnydrobiopterin (A) + L-phenylalanine + O2 = (4aS,6R)-4a-hydroxy-L-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (B) + L-tyrosine

A downloaded human phenylalanine hydroxylase includes cofactors

A, b(2-thienyl)alanine, and ion. The water molecules are erased, and the b(2-thienyl)alanine is converted to

L-phenylalanine (

Figure 42a). This phenylalanine hydroxylase is different from the phenylalanine hydroxylase from human

Legionella pneumophila, which has a major functional role in the synthesis of the pigment pyomelanin (a potential virulence factor). The reaction center of this phenylalanine hydroxylase is relatively hydrophobic, and the residual amino acids within 5Å from the substitute phenylalanine are 20% aromatic amino acids compared to 14% of the total 309 amino acids. The reaction center of later phenylalanine hydroxylase is hydrophilic [

66]. Therefore, these human phenylalanine hydroxylases should have different contributions to pathophysiology. A cofactor, iron (Fe2

+) forms a six-coordinate complex. The ion binds with two histidine ring nitrogens (H285, H290) and two glutamic acid oxygens (E330). The free ports should bind oxygen ligands to bridge with (6

R)-

S-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahnydrobiopterin and

S-phenylalanine. Therefore, two oxygen atoms were added and bound to the iron; then, the complex structure was optimized. The optimized structure is shown in

Figure 42b. Then, (6

R)-

S-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahnydrobiopterin is oxygenated to (4a

S,6

R)-4ahydroxy-

S-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin, and phenylalanine is converted to

S-tyrosine. The new complex is optimized. The optimized structure is shown in

Figure 42c.

The cofactor conformations before and after the enzyme reaction are extracted from

Figure 42 and are shown in

Figure 43a-c. The reaction processes are examined by apc (unit: au) calculation using MOPAC PM5. The key atoms are circled in the Figure. The apc values are summarized in

Table 3.

The apc values of key atoms indicate that the complex formation induces the electron localization toward the oxidation of compound A and reduction of compound B. The highest difference of the carbon (C) apc (0.075 or 0.570 au) supports the reaction center.

Phenylalanine hydroxylase is the first enzyme in phenylalanine metabolism. When this enzyme activity is weakened, these cofactors (in the correct dose) may reactivate the enzyme reaction. However, compound A tetrahydrobiopterin is biosynthesized from

guanosine triphosphate (GTP) by three chemical reactions mediated by the enzymes GTP cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH), 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase (PTPS), and sepiapterin reductase (SR) [

67]. Therefore, the reactivation of phenylalanine hydroxylase is not simple. It requires iron, oxygen, and compound A, whose precursor is not a simple chemical. Furthermore, compound A is a cofactor involved in the synthesis of serotonin, dopamine, and nitric oxide, which have all been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. The compound A is considered an effective compound in treating all symptom domains of schizophrenia [

68].

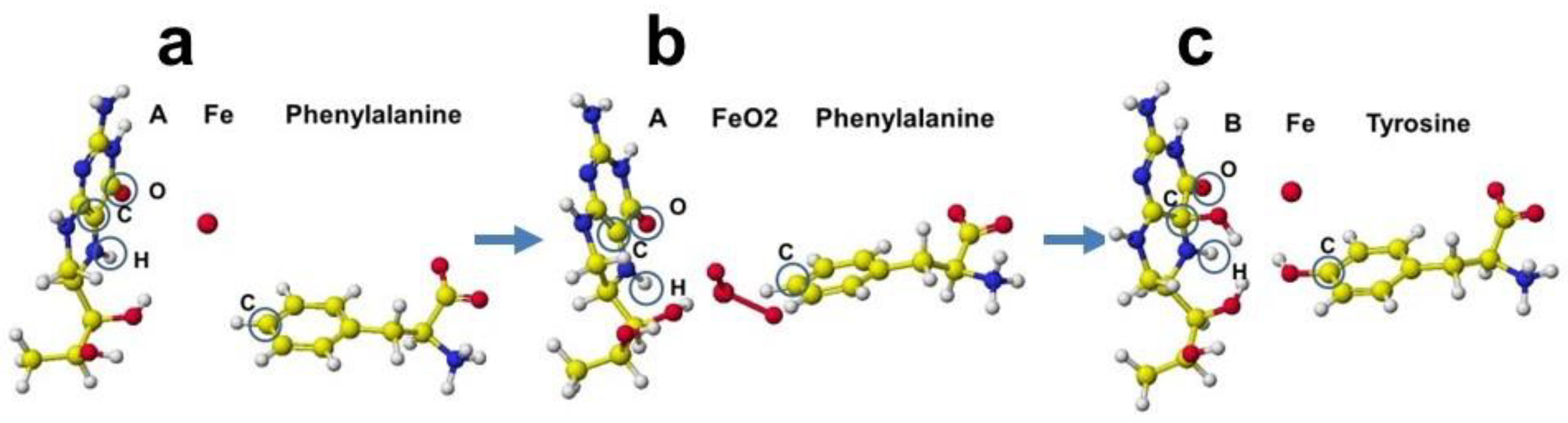

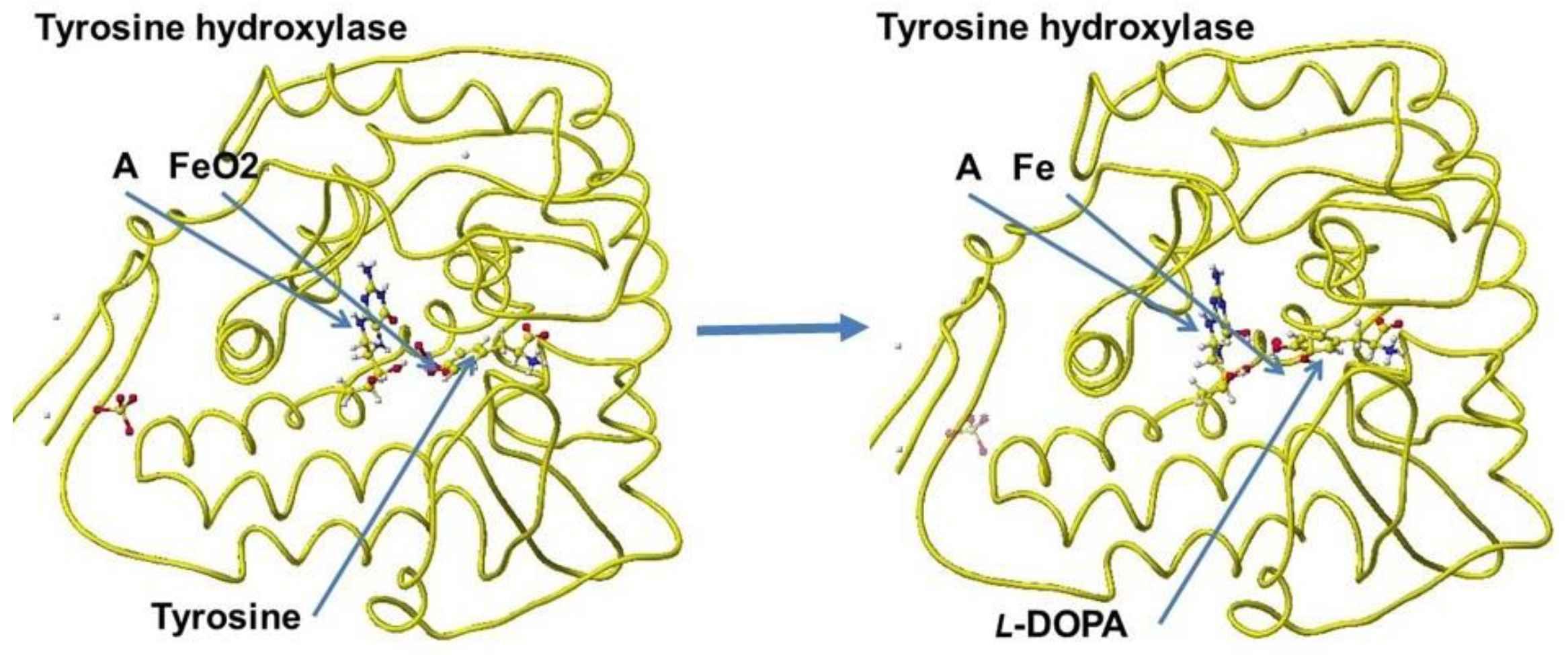

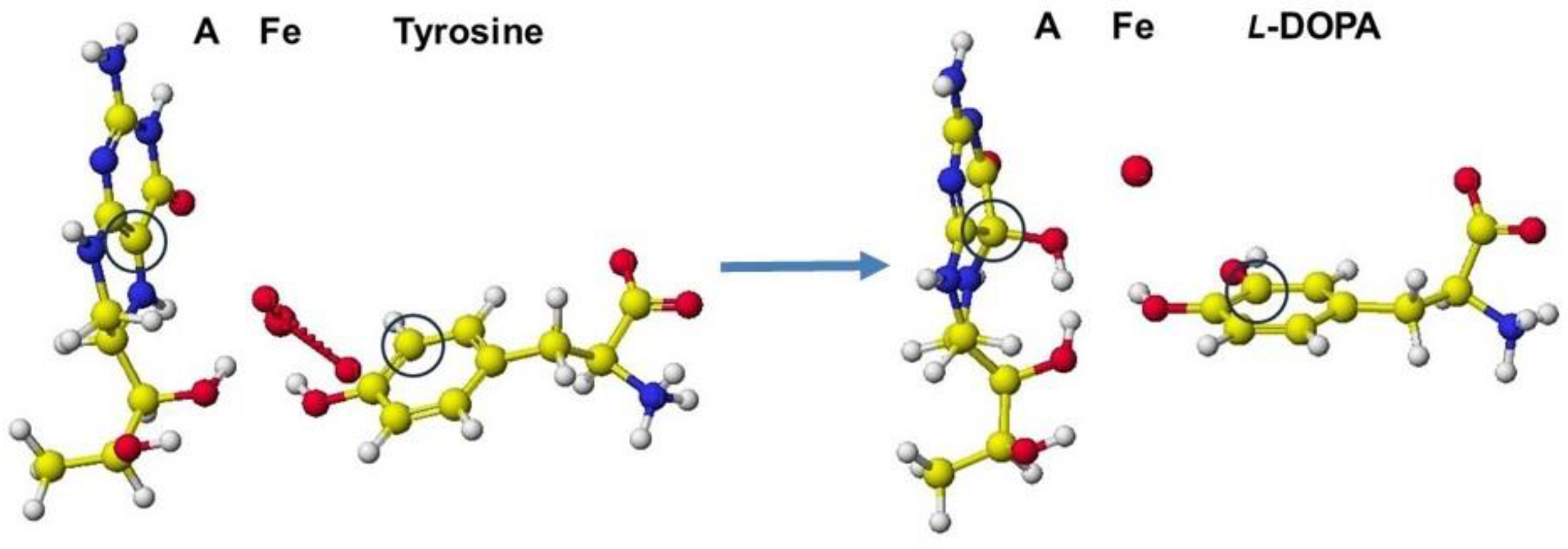

3.10.2. Human Tyrosine Hydroxylase

Tyrosine hydrogenase follows phenylalanine hydrogenase in the process of phenylalanine metabolism.

Tyrosine hydroxylase catalyzes the hydroxylation of

L-tyrosine to

L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (

L-DOPA). The reaction is described in the following equation [

67,

68].

(6R)-L-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahnydrobiopterin (A) + L-tyrosine + O2 = (4aS,6R)-4a-hydroxy-L-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (B) + L-DOPA

A downloaded human tyrosine hydroxylase structure (PDB 2XSN only zinc ion and a rat tyrosine hydroxylase that contains 7,8-dihydrobiopterin and iron ion; however, these locations are not adequate to analyze the reaction mechanism. Tyrosine hydroxylase and phenylalanine hydroxylase use the same cofactors, and their stereo structures are very similar. Therefore, the stereo structure of tyrosine hydroxylase is constructed from the phenylalanine hydroxylase previously prepared [

68]. The stereo structure of tyrosine hydroxylase and the reaction scheme are shown in

Figure 44 and

Figure 45.

The apc values of the reaction center atoms indicate the electron localization affected by the surrounding molecules; therefore, the initial location of cofactors is critical to analyzing the reaction mechanisms. We should carefully select a downloaded PDB file, even if the species differ, but the fundamental conformation should be the same for the same reactions. The careful replacement of residual amino acids can produce the stereo structure of human enzymes.

Tyrosine hydroxylase is the second enzyme in phenylalanine metabolism. The enzyme reaction mechanism is the same as that of phenylalanine hydroxylase, and the cofactors are the same. Therefore, we can use the same approach used for phenylalanine hydroxylase.. When this enzyme activity is weakened, these cofactors (in the correct dose) may reactivate the enzyme reaction. However, compound A tetrahydrobiopterin is biosynthesized from

guanosine triphosphate (GTP) by three chemical reactions mediated by the enzymes GTP cyclohydrolase I, 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase, and sepiapterin reductase [

67]. Therefore, the reactivation of tyrosine hydroxylase is not simple. It requires iron, oxygen, and compound A, whose precursor is not a simple chemical. Furthermore, compound A is a cofactor involved in the synthesis of serotonin, dopamine, and nitric oxide, which have all been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. The compound A is considered an effective compound in treating all symptom domains of schizophrenia [

68].

Figure 1.

Correction points of the coenzyme structure White, yellow (gray), blue (dark gray), red (black), and purple (large black) balls: hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphate.

Figure 1.

Correction points of the coenzyme structure White, yellow (gray), blue (dark gray), red (black), and purple (large black) balls: hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphate.

Figure 2.

A directly optimized ELI3 structure after replacing the whole amino acids.

Figure 2.

A directly optimized ELI3 structure after replacing the whole amino acids.

Figure 3.

Optimized Structure of.aspartate racemase 5wxz with R(D)-aspartate.

Figure 3.

Optimized Structure of.aspartate racemase 5wxz with R(D)-aspartate.

Figure 4.

Extracted R(D)-aspartate with surrounded residues.

Figure 4.

Extracted R(D)-aspartate with surrounded residues.

Figure 5.

Extracted R(D)- and S(L)-aspartates with measured angle.

Figure 5.

Extracted R(D)- and S(L)-aspartates with measured angle.

Figure 6.

Optimized structure of glutamate racemase 1zum with R(D)-glutamate.

Figure 6.

Optimized structure of glutamate racemase 1zum with R(D)-glutamate.

Figure 7.

Extracted R(D)-glutamate with measured angle.

Figure 7.

Extracted R(D)-glutamate with measured angle.

Figure 8.

Extracted S(L)-glutamate with measured angle.

Figure 8.

Extracted S(L)-glutamate with measured angle.

Figure 9.

Aspartate oxidase, conformation A .

Figure 9.

Aspartate oxidase, conformation A .

Figure 10.

S(L)-aspartate and tightly bound residues in conformation A.

Figure 10.

S(L)-aspartate and tightly bound residues in conformation A.

Figure 11.

Aspartate oxidase, conformation B.

Figure 11.

Aspartate oxidase, conformation B.

Figure 12.

S(L)-aspartate and tightly bound residues in conformation B.

Figure 12.

S(L)-aspartate and tightly bound residues in conformation B.

Figure 13.

Optimized structure of 7e0d E305R with S(L)-glutamate.with S(L)-glutamate.

Figure 13.

Optimized structure of 7e0d E305R with S(L)-glutamate.with S(L)-glutamate.

Figure 14.

Extracted S(L)-glutamate with bound molecules.

Figure 14.

Extracted S(L)-glutamate with bound molecules.

Figure 15.

Optimized structure of arginine oxidase with S(L)-arginine.

Figure 15.

Optimized structure of arginine oxidase with S(L)-arginine.

Figure 16.

Conformation of around S(L)-arginine.

Figure 16.

Conformation of around S(L)-arginine.

Figure 17.

Optimized structure of arginine oxidase 7e0d.

Figure 17.

Optimized structure of arginine oxidase 7e0d.

Figure 18.

Conformation of around S(L)-arginine.

Figure 18.

Conformation of around S(L)-arginine.

Figure 19.

Optimized structure of 7x2k lysine oxidase.

Figure 19.

Optimized structure of 7x2k lysine oxidase.

Figure 20.

Extracted conformation around the substitute S(L) -arginine.

Figure 20.

Extracted conformation around the substitute S(L) -arginine.

Figure 21.

Optimized structure of arginine oxidase.

Figure 21.

Optimized structure of arginine oxidase.

Figure 22.

The conformation around S(L)-arginine.

Figure 22.

The conformation around S(L)-arginine.

Figure 23.

Optimized structure of 3x0v with S(L)-lysine.

Figure 23.

Optimized structure of 3x0v with S(L)-lysine.

Figure 24.

Extracted conformation structure of S(L) lysine complex.

Figure 24.

Extracted conformation structure of S(L) lysine complex.

Figure 25.

Optimized structure of 7eii with S(L)-lysine.

Figure 25.

Optimized structure of 7eii with S(L)-lysine.

Figure 26.

Extracted conformation around the S(L)-lysine.

Figure 26.

Extracted conformation around the S(L)-lysine.

Figure 27.

Optimized structure of 7x7j lysine oxidase.

Figure 27.

Optimized structure of 7x7j lysine oxidase.

Figure 28.

Extracted conformation around the substitute S(L) -arginine.

Figure 28.

Extracted conformation around the substitute S(L) -arginine.

Figure 29.

Optimized structure of 5yb7 lysine.

Figure 29.

Optimized structure of 5yb7 lysine.

Figure 30.

Extracted conformation around the Oxidase substitute S(L)-lysine.

Figure 30.

Extracted conformation around the Oxidase substitute S(L)-lysine.

Figure 31.

Downloaded and optimized stereo structure of Arginine: Glycineamidinotransferase (GAT) including arginine and glycine.

Figure 31.

Downloaded and optimized stereo structure of Arginine: Glycineamidinotransferase (GAT) including arginine and glycine.

Figure 32.

Atomic partial charge of arginine heavy atoms of free form (original) and optimized inside the enzyme.

Figure 32.

Atomic partial charge of arginine heavy atoms of free form (original) and optimized inside the enzyme.

Figure 33.

Extracted stereo structure of arginine and substitutes with residual amino acids within 3 Å from the arginine (Arg) or ornithine (ORN). The key atom distances are indicated in the Figures.

Figure 33.

Extracted stereo structure of arginine and substitutes with residual amino acids within 3 Å from the arginine (Arg) or ornithine (ORN). The key atom distances are indicated in the Figures.

Figure 34.

Extracted conformations of pre- and post-reactions with heavy atom atomic partial charge values.

Figure 34.

Extracted conformations of pre- and post-reactions with heavy atom atomic partial charge values.

Figure 35.

Optimized structure and heavy atom atomic partial charge values of glycine and guanidinoacetate.

Figure 35.

Optimized structure and heavy atom atomic partial charge values of glycine and guanidinoacetate.

Figure 36.

Downloaded and optimized the Structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase, extracted and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine.

Figure 36.

Downloaded and optimized the Structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase, extracted and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine.

Figure 37.

Optimized Structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase with modified S-adenosylmethionine and the extracted conformation and S-adenosylmethionine.

Figure 37.

Optimized Structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase with modified S-adenosylmethionine and the extracted conformation and S-adenosylmethionine.

Figure 38.

Optimized Structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase, S-adenosylmethionine, and Lhomocysteine, guanidinoacetate, extracted conformation, and S-adenosylmethionine guanidinoacetate complex.

Figure 38.

Optimized Structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase, S-adenosylmethionine, and Lhomocysteine, guanidinoacetate, extracted conformation, and S-adenosylmethionine guanidinoacetate complex.

Figure 39.

Optimized structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase with S-adenosyl- and creatine complex, the extracted conformation and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine, and creatine complex.

Figure 39.

Optimized structure of Guanidinoacetic acid N-methyltransferase with S-adenosyl- and creatine complex, the extracted conformation and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine, and creatine complex.

Figure 40.

Optimized Structure of S-adenosylmethionine (A), complex of extracted S-adenosylmethionine and guanidino acetic acid (B).

Figure 40.

Optimized Structure of S-adenosylmethionine (A), complex of extracted S-adenosylmethionine and guanidino acetic acid (B).

Figure 41.

Structures of human creatine kinase before and after the enzyme reaction.

Figure 41.

Structures of human creatine kinase before and after the enzyme reaction.

Figure 42.

a. Reaction scheme of phenylalanine hydroxylase; b. Optimized structure of phenylalanine hydrogenase complex with ligand oxygen atoms; c. Optimized structure of phenylalanine hydrogenase complex with tyrosine.

Figure 42.

a. Reaction scheme of phenylalanine hydroxylase; b. Optimized structure of phenylalanine hydrogenase complex with ligand oxygen atoms; c. Optimized structure of phenylalanine hydrogenase complex with tyrosine.

Figure 43.

Reaction processes of phenylalanine hydroxylase.

Figure 43.

Reaction processes of phenylalanine hydroxylase.

Figure 44.

Reaction scheme of tyrosine hydroxylase; b. Optimized structure of tyrosine hydrogenase complex with cofactor (A), iron, and tyrosine, and tyrosine hydrogenase complex with L-DOPA.

Figure 44.

Reaction scheme of tyrosine hydroxylase; b. Optimized structure of tyrosine hydrogenase complex with cofactor (A), iron, and tyrosine, and tyrosine hydrogenase complex with L-DOPA.

Figure 45.

Reaction processes of tyrosine hydroxylase: The key carbon atoms are circled to explain the reaction.

Figure 45.

Reaction processes of tyrosine hydroxylase: The key carbon atoms are circled to explain the reaction.

Table 1.

Properties of aspartate before and after complexing with aspartate racemase (5wxz)

Table 1.

Properties of aspartate before and after complexing with aspartate racemase (5wxz)

| |

R(D)-Aspartate |

S(L)-Aspartate |

| |

Angle° |

apc (au) |

Angle° |

apc (au) |

|

Before |

After |

DaH |

DaC |

DaN+

|

Before |

After |

DaH |

DaC |

DaN+

|

| CO2--C.H.–CH2

|

113.07 |

111.13 |

0.004 |

+0.054 |

-0.062 |

113.11 |

116.31 |

+0.003 |

+.074 |

-0.053 |

| NH3+ -CH–CO2-

|

99.74 |

101.32 |

|

|

|

99.74 |

103.78 |

|

|

|

| NH3+ -CH–CH2

|

110.46 |

113.10 |

|

|

|

110.50 |

110.07 |

|

|

|

| Total |

323.27 |

325.55 |

|

|

|

323.35 |

330.16 |

|

|

|

| Change |

|

2.28° |

|

|

|

|

6.81° |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Properties of glutamate before and after in complex with glutamate racemase (1zuw)

Table 2.

Properties of glutamate before and after in complex with glutamate racemase (1zuw)

| |

R(D)-Glutamate |

S(L)-Glutamate |

| |

Angle ° |

apc (au) |

Angle ° |

apc (au) |

| |

Before |

After |

DaH |

DaC |

DaN+ |

Before |

After |

DaH |

DaC |

DaN |

| CO2- - C.H. – CH2

|

110.33 |

112.26 |

0.052 |

0.009 |

-0.031 |

110.23 |

111.21 |

0.023 |

0.048 |

-0.038 |

| NH3+ - CH – CO2-

|

99.76 |

104.81 |

|

|

|

|

99.72 |

105.91 |

|

|

| NH3+ - CH – CH2

|

112.84 |

109.97 |

|

|

|

|

113.44 |

113.44 |

|

|

| Total |

322.93 |

327.04 |

|

|

|

|

323.39 |

330.56 |

|

|

| Change |

|

4.11° |

|

|

|

|

|

7.17 |

|

|

Table 3.

Atomic partial charge of key atoms (au).

Table 3.

Atomic partial charge of key atoms (au).

| Cofactor |

|

A (free) |

A+FeO2 |

D |

B |

D |

B (free) |

| Atom |

C |

-0.215 |

-0.196 |

(+0.019) |

0.299 |

(-0.056) |

0.355 |

| |

O |

-0.512 |

-0.573 |

(+0.061) |

-0.397 |

(+0.081) |

-0.478 |

| |

H |

-0.155 |

-0.138 |

(+0.017) |

0.130 |

(-0.022) |

0.152 |

| Amino acid |

PhAl (free) |

PhAl+FeO2 |

|

Tyr |

|

Tyr (free) |

|

| |

C |

-0.155 |

-0.138 |

(+0.017) |

0.130 |

(-0.022) |

0.152 |