1. Introduction

Feed supply is a key factor in the sustainable development of the livestock industry. With the rapid expansion and intensification of the Chinese livestock sector, the demand for feed has steadily increased [1]. C. korshinskii is a drought-resistant leguminous shrub widely cultivated in the northwestern region of China for desertification management [2]. Years of neglecting the coppicing of C. korshinskii may lead to an increased risk of branch aging, wilting, and death [3]. Coppicing holds great significance for C. korshinskii, but the effective utilization of coppicing waste is still a problem to be solved [4].

The competition for food resources between humans and livestock is becoming increasingly evident, highlighting the importance of developing unconventional feed sources [5]. TheC. korshinskiibranches and leaves contain high CP and trace elements, which are beneficial for animal growth [6,7]. As a woody plant, C. korshinskii can accumulate a large amount of biomass. C. korshinskii nutrient content and palatability can be affected by the stage of growth, which causes its harvest time to be seasonally limited. Converting it to hay leads to nutrient loss and increased lignin content. Silage is a convenient method of forage preservation that can alleviate feed shortages in arid regions [8,42]. Silage has become a vital component of livestock feed and is widely adopted in the livestock industry [9,10].

Silage is a complex biochemical process. If the number of Lactobacillaceae attached to the forage is insufficient, it will lead to silage failure. The anaerobic environment is conducive to the growth and metabolism of Lactobacillaceae [13,14]. Lactobacillaceae convert the WSC into lactic acid. When the pH of the silage feed falls below 4, it inhibits the growth and metabolism of most microorganisms, including the Lactobacillaceae themselves [11,12]. With the progression of silage, changes in the microbial community have also occurred [15]. In recent years, researchers have utilized molecular techniques to clarify the parameters of silage and the changes in the microbial community [16,17]. Understanding the complex changes in microbial communities and their functional succession during fermentation is crucial for the development of silage [18-20]. High-throughput sequencing has been widely used in the study of silage microbial communities [21,40]. 16S rRNA is a conserved bacterial sequence frequently utilized for microbial identification [37].

The WSC content of C. korshinskii is relatively low, and its buffering capacity is high, which leads to a lower success rate of silage. C. korshinskiiis characterized by a relatively high tannin content, and studies have indicated that tannins can be detrimental to lactic acid fermentation [27]. The co-silage of C. korshinskii with other forage crops can effectively reduce the tannin content in the silage system, increase the WSC, and thereby enhance the success rate of silage [48,22].

This study assessed the effects of S. psammophila and corn stalks on the nutritional composition and microbial community of C. korshinskii silage. The results aim to provide theoretical guidance and technical support for shrub silage production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Processing

In November 2022, C. korshinskii, S. psammophila, and corn stalks were collected from Wushen Country, Ordos City, Inner Mongolia (38°36’11.5"N, 108°49’48.8"E). The materials were chopped into a size of 2-3cm and stored in woven bags for subsequent use.

The experiment included three treatment groups:

CK group: 30 kg of C. korshinskii supplemented with 3 kg of sugar, with a compacted density of 380 kg/m3.

CS group: 15 kg of C. korshinskii mixed with 15 kg of S. psammophila and 3 kg of sugar.

CC group: 15 kg of C. korshinskii mixed with 15 kg of corn stalks.

After mixing with different materials of S. psammophila and corn stalks inoculants respectively, adjusted to approximate 60% moisture content (fresh weight basis), and anaerobically fermented in sealed 100-L silo and vacuum-sealed at room temperature (25–28°C) for 60 days. After measurement and calculation, the final compacted density is about 380 kg/m3. Each treatment was replicated three times. After 60 days, samples were collected using the quartering method for further analysis.

2.2. Fermentation Characteristics and Chemical Composition Analysis

Silage was placed in an air-forced drying oven at 65°C for 72 hours to analyze DM[41]. The dried samples were ground into 1-mm particles using a mill for nutrient analysis[42]. An elemental analyzer determined total nitrogen according to the Dumas method[43]. WSC was analyzed by the anthrone method. NDF and ADF were performed via the method of Van Soest et al, and sodium sulfite and alpha-amylase were added for the NDF producer[44]. The content of ADL in the sample is determined by the gravimetric method[45].

Samples (10 g) were homogenized in distilled water (90 mL) at 4°C for 24 h. Thereafter, the organic acids analysis of the silage extract was made by filtering the mixture through four layers of cheesecloth and qualitative filter paper. The concentration of organic acids were determined using the Agilent HPLC 1260 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which was equipped with a 210 nm UV detector (Sciex API 5000; McKinley Scientific, Sparta Township, NJ, USA) and Agilent Hi-Plex H column (Agilent Technologies, USA). The eluent was 5 mM H2SO4 with a running rate of 0.7 mL/min at a 55°C column oven temperature.

2.3. Microbial Community Analysis

The original sequencing data is stored on the NovoMagic cloud-based bioinformatics platform (

https://magic.novogene.com) for subsequent analysis. After quality control and noise reduction through DADA2, high-quality amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated. QIIME2 was used to assess microbial community diversity, including alpha diversity indices (Chao1 richness, Shannon, and Simpson diversity indices) and beta diversity metrics. Multivariate analyses, including principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), were employed to evaluate changes in microbial community composition and structure.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data on chemical composition (e.g., ASH, WSC, and CP) and silage quality (e.g., organic acids) were analyzed using Excel and GraphPad Prism 9. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA, and differences among groups were assessed at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of Silage

A comparative analysis of nutritional components in the silage samples revealed significant differences in nutrient composition among the experimental groups (Table 1). The ASH content in the CS group (3.15% DM) was significantly lower than that in the CK (4.28% DM) and CC (4.53% DM) groups (p < 0.01). The WSC content in the CS group (2.27% DM) was significantly higher than that in the CK group (0.85% DM, p < 0.0001). The CP content in the CK group (8.17% DM) was higher than in the CC (6.03% DM) and CS (6.53% DM) groups (p < 0.001). The NDF content in the CS group (72.97% DM) was significantly lower than in the CK group (78.35% DM, p < 0.05). Significant differences in ADF and ADL content were also observed among the groups (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Nutrient composition in different treatment groups after 60 days of silage

Table 1.

Nutrient composition in different treatment groups after 60 days of silage

|

|

|

|

| |

CK |

CC |

CS |

|

|

| ASH (%) |

4.

|

4.

|

3.

|

0.199 |

** |

| CP (%) |

8.

|

6.

|

6.

|

0.263 |

*** |

| NDF (%) |

78.

|

76.

|

72.

|

0.763 |

* |

| ADF (%) |

55.

|

49.

|

58.

|

1.063 |

*** |

| ADL (%) |

25.

|

16.

|

25.

|

0.92 |

*** |

| WSC (%) |

0.

|

0.

|

2.

|

0.075 |

**** |

|

-N (g/100g) |

0.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.019 |

NS |

3.2. Fermented Organic Acid Content

A comparative analysis of organic acids in the silage samples revealed significant differences among the groups (Table 2). The CK group had significantly higher concentrations of lactic acid (0.81 g/mL), formic acid (2.58 g/mL), propionic acid (0.36 g/mL), and valeric acid (2.19 g/mL), compared to both the CC and CS groups (p < 0.05). The lactic acid-to-acetic acid ratio in the CK group (0.72) was also higher than in the other groups (p < 0.05). The isobutyric acid content in the CS group (2.89 g/mL) was significantly higher than in the CK (0.18 g/mL) and CC (0.12 g/mL) groups (p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Comparison of different materials across various items.

Table 2.

Comparison of different materials across various items.

|

|

|

|

| |

CK |

CC |

CS |

|

|

| Lactic acid (g/mL) |

0.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.09 |

* |

| Acetic acid (g/mL) |

1.

|

1.

|

1.

|

0.18 |

NS |

| Lactic acid / Acetic acid |

0.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.09 |

* |

| Formic acid (g/mL) |

2.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.17 |

*** |

| Propionic acid (g/mL) |

0.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.05 |

** |

| Valeric acid (g/mL) |

2.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.59 |

**** |

| Butyric acid (g/mL) |

0.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.11 |

*** |

| Isobutyric acid (g/mL) |

0.

|

0.

|

2.

|

0.08 |

**** |

3.3. Cluster Analysis of Microorganisms

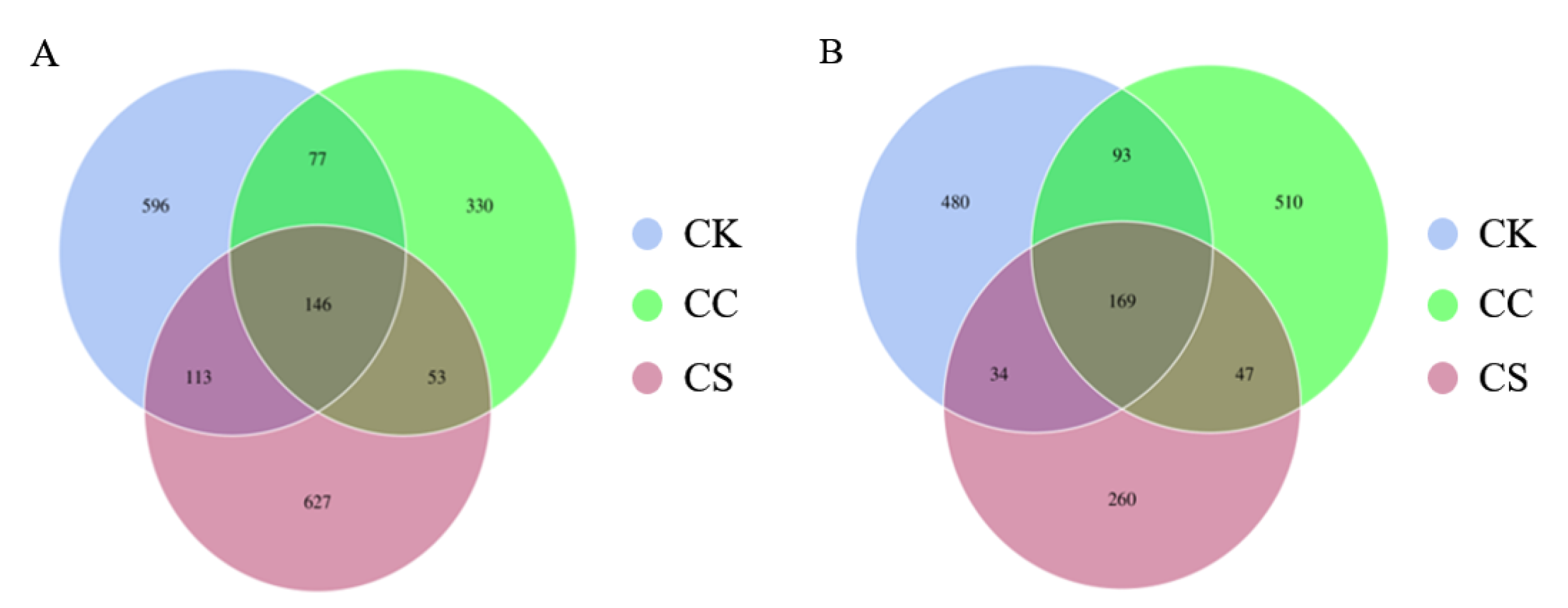

Microbial profiling of silage samples yielded 1,942 bacterial and 1,593 fungal ASVs (

Figure 1). Bacterial ASV (

Figure 1A) richness varied by treatment: CS (627) > CK (596) > CC (330). Fungal (

Figure 1B) richness showed an inverse trend: CC (510) > CK (480) > CS (260).

3.4. Relative Abundance of Microbial Species

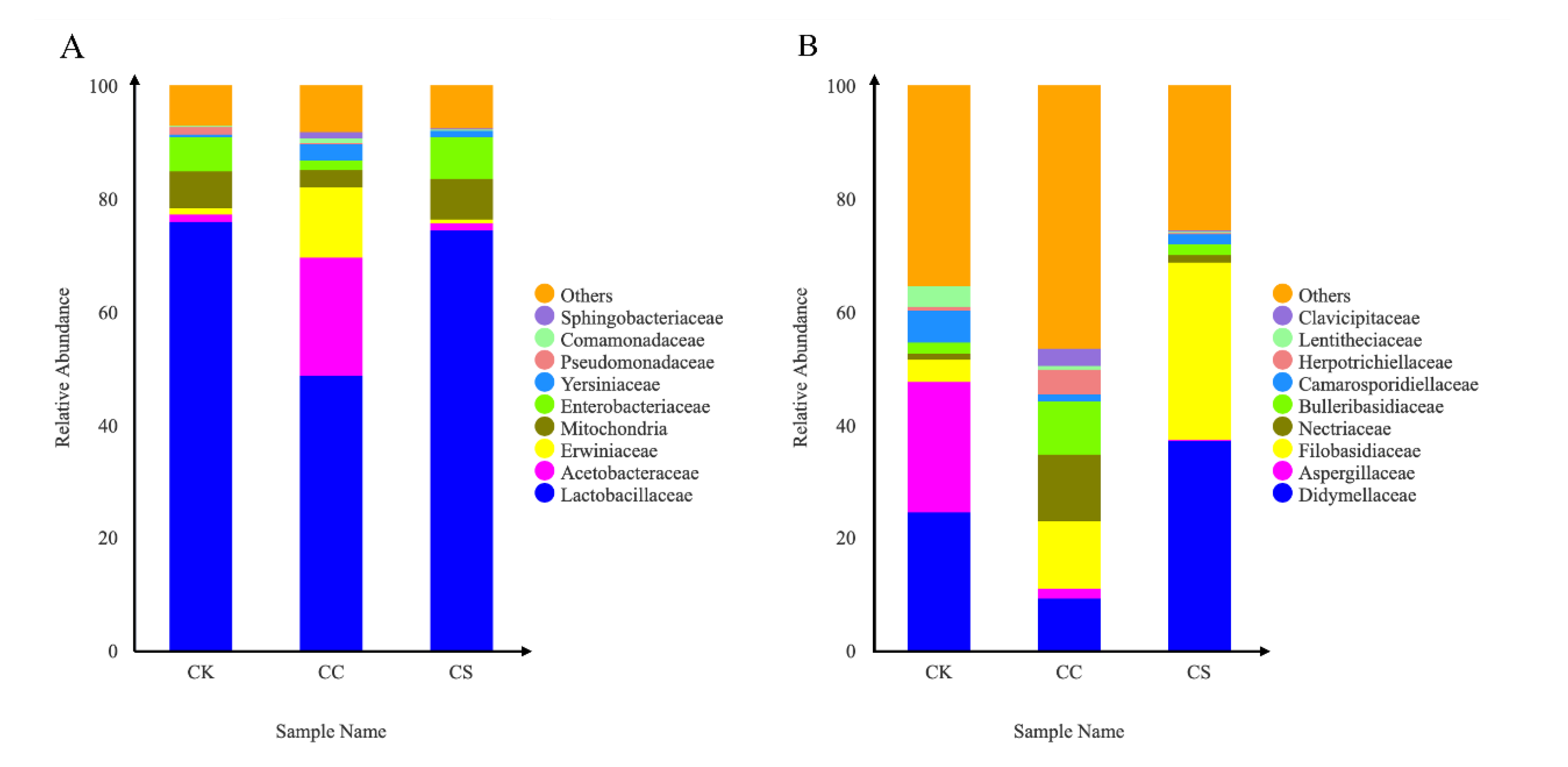

At the family taxonomic rank,

Lactobacillaceae was the dominant bacterial group in all treatment groups, accounting for 72.17% in the CK group, 59.58% in the CS group, and 44.76% in the CC group (

Figure 2A). Among fungi,

Didymellaceae had the highest relative abundance, with 24.68% in the CK group, 37.20% in the CS group, and 9.13% in the CC group (

Figure 2B).

3.5. Alpha Diversity of Silage

The Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices were used to evaluate microbial diversity (Tables 3 and 4). The bacterial Chao1 index was relatively high in the CK (410.81) and CS (431.81) groups but lower in the CC group (338.75). The fungal Chao1 index was higher in the CC group (371.08) compared to the CK (340) and CS groups (343.62). The Simpson index indicated lower bacterial diversity in the CK (0.82) and CS (0.79) groups compared to the CC group (0.96).

Table 3.

diversity of bacteria in treatment groups

Table 3.

diversity of bacteria in treatment groups

|

|

|

|

| |

CK |

CC |

CS |

|

|

| Chao

|

410.81 |

338.75 |

431.81 |

53.43 |

0.313 |

|

3.83 |

3.38 |

3.41 |

0.21 |

0.148 |

|

0.86 |

0.77 |

0.86 |

0.21 |

0.549 |

| Coverage |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

– |

– |

Table 4.

diversity of fungi in three experimental groups.

Table 4.

diversity of fungi in three experimental groups.

|

|

|

|

| |

CK |

CC |

CS |

|

|

| Chao

|

340.0 |

371.08 |

343.62 |

35.09 |

0.473 |

|

4.

|

5.

|

3.

|

0.20 |

0.025 |

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.

|

0.02 |

0.001 |

| Coverage |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

– |

– |

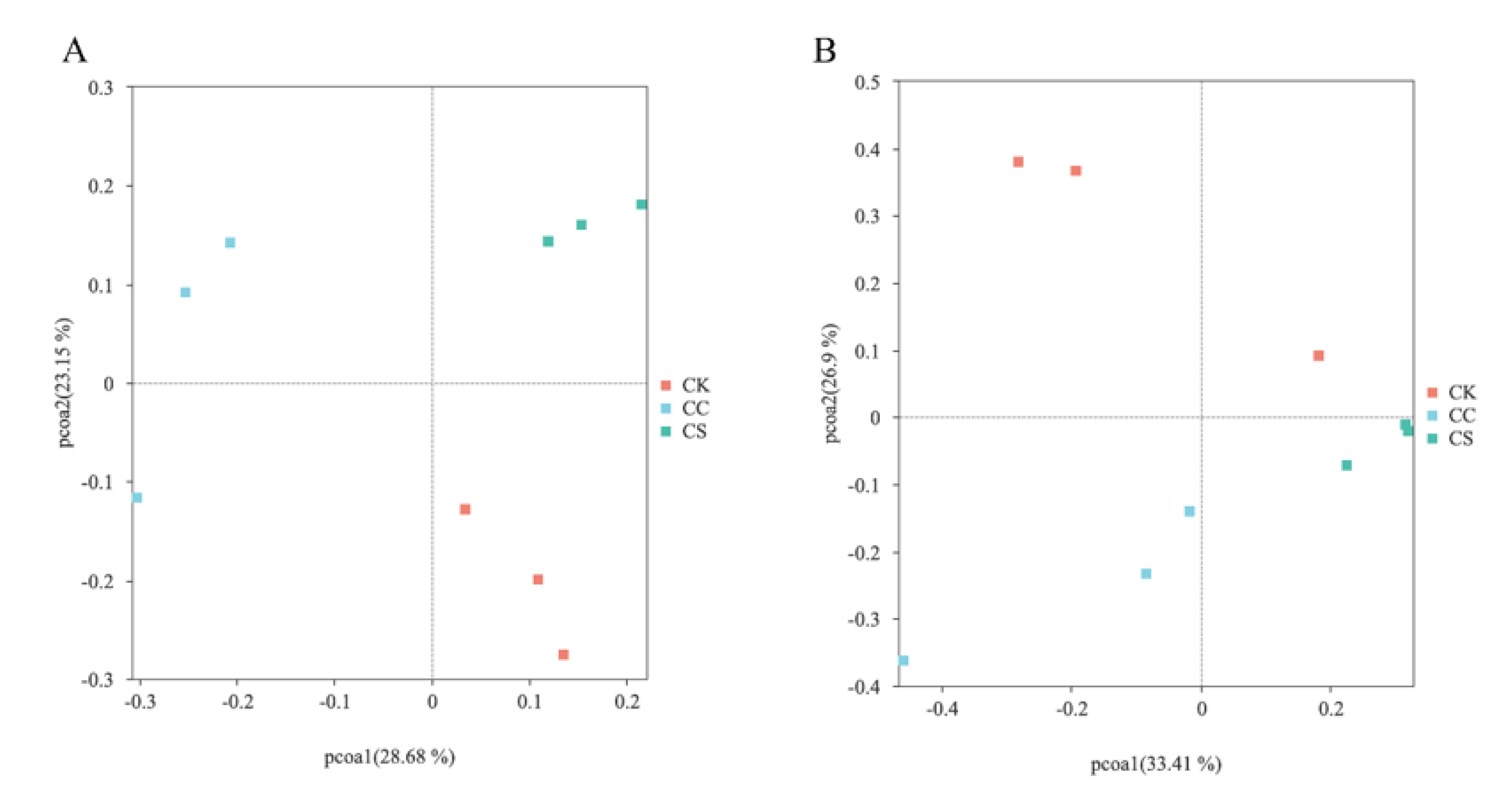

3.6. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA)

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) utilizing Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics demonstrated significant segregation of microbial communities across treatment groups (

Figure 3).

Figure 3A reveals the differences in the spatial distribution of bacteria in the three treatment groups, with CS samples predominantly occupying the first quadrant, CC samples distributed across the second and third quadrants, and CK samples clustering in the fourth quadrant.

Figure 3B shows the distribution of fungal PCOA in the three groups. The CK group is distributed in the first and second quadrants, the CC treatment group is in the third quadrant, and the CS treatment group is concentrated in the fourth quadrant. This quadrant-specific distribution indicates pronounced structural divergence in microbial community composition among treatments.

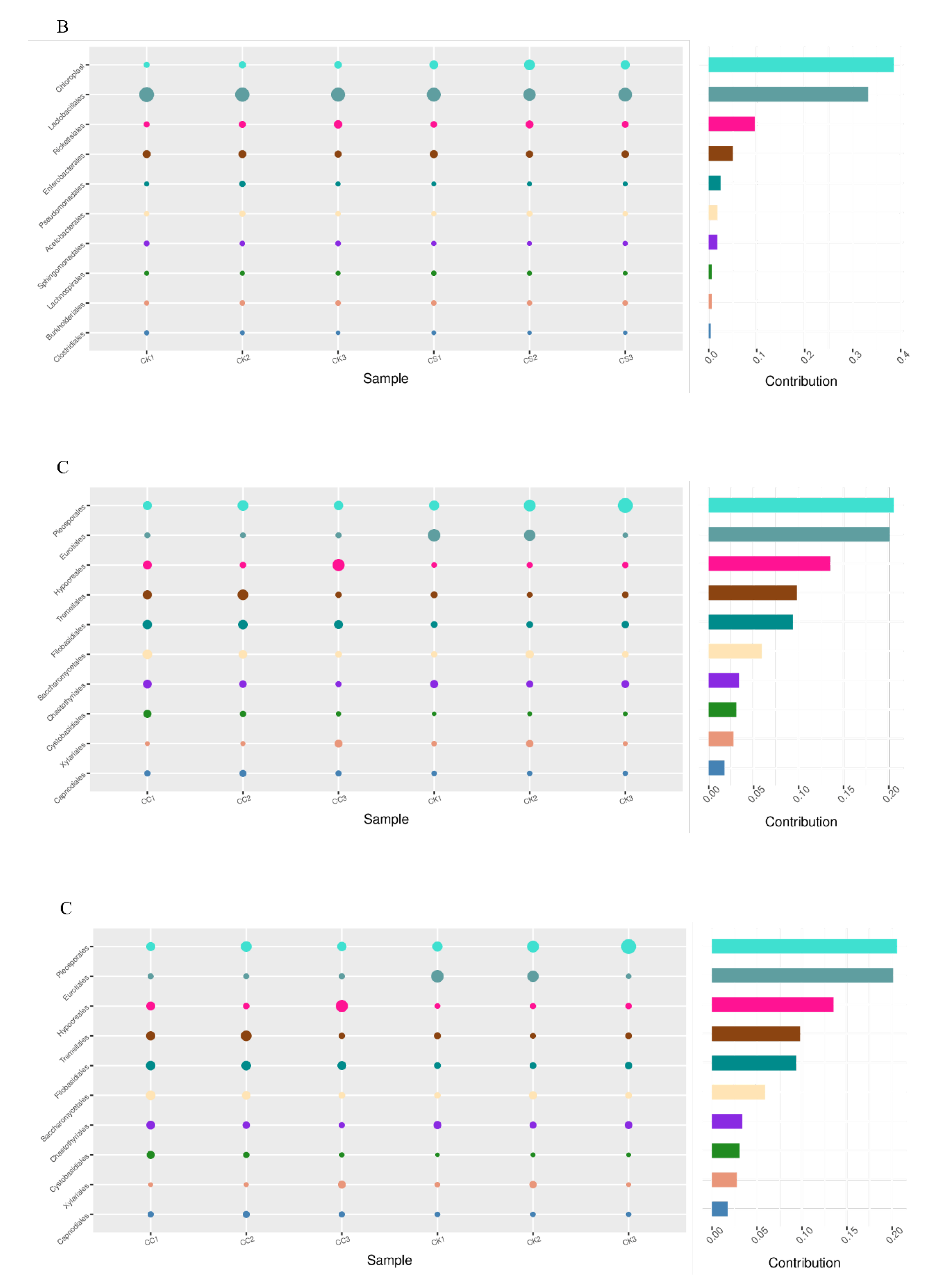

3.7. SIMPER Analysis

SIMPER (Similarity PERcentage) analysis indicates significant differences among the three treatment groups duerent microbial cme to the composition of diffomunities (

Figure 4).

Lactobacillaceae were identified as the main bacteria responsible for the differences between the CK and CC groups, accounting for 36% (

Figure 4A). At the same time,

Lactobacillaceae is also the main bacterium responsible for the differences between CK and CS (

Figure 4B). The comparison of fungal communities showed that

Pleosporales and

Eurotiales caused significant differences between the CK and CC groups (

Figure 4C), while

Filobasidiales and

Eurotiales were the main reasons for the differences between the CK and CS groups (

Figure 4D).

4. Discussion

Research indicates that isobutyric acid is commonly associated with Clostridium fermentation, which can negatively impact the quality of silage feeds by increasing pH and promoting the growth of spoilage microorganisms [28]. The high isobutyric acid and Pleosporales in the CS treatment group suggest a poorer fermentation quality. This is consistent with previous studies showing that high lignin content in woody plants like S. psammophila can hinder fermentation by reducing the availability of fermentable sugars [24,32].

In contrast, the CK group exhibited excellent fermentation quality, with higher lactic acid, formic acid, and other organic acids, as well as a higher ratio of lactic acid to acetic acid. These findings are consistent with previous studies, indicating that Lactobacillaceae play a crucial role in the fermentation of silage feed by converting WSC into lactic acid, thereby lowering the pH and inhibiting spoilage microorganisms [33,34]. Lactobacillaceas have a strong ability to produce lactic acid [38].Lactobacillaceas utilize WSC for growth and metabolism; sufficient WSC is a key factor for the successful fermentation of silage feed [29-31]. The dominance of Lactobacillaceae in the CK treatment group further supports this observation. Microbial community analysis shows significant differences in bacterial and fungal diversity among the treatment groups. The relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in the CK group (72.17%) is significantly higher than that in the CS group (58.58%) and the CC group (44.76%), indicating that the supplementation of WSC in the silage system is beneficial for the growth and metabolism of Lactobacillaceae.

In contrast, the abundance of Lactobacillaceas in the CC and CS groups is relatively low, which may be the reason for their poorer fermentation quality, as insufficient lactic acid production could prevent the pH from reducing to the ideal range, thereby failing to inhibit undesirable microbial activity [35,36].

SIMPER analysis found that Lactobacillaceae was the main factor contributing to the differences between treatment groups. In fungi, Pleosporales and Eurotiales were major contributors to the differences between the CK and CC groups, while the Filobasidiales and Eurotiales abundance differences led to differences in the CK and CS groups. As shown by the Simpson index, the fungal diversity was higher in the CC and CS treatment groups, indicating that the growth of harmful microorganisms was not inhibited. The CS group had higher ADF and ADL compared to the CC group, indicating that the quality of S. psammophila mixed with C. korshinskii silage was poor. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown that high ADL content can negatively affect the digestibility and palatability of silage [23,48]. In contrast, the lower ADF and ADL in the CC group suggest that corn stalks may be a more suitable additive to improve the fermentation quality of C. korshinskii silage.

This study indicates that the addition of S. psammophila and corn stalks significantly alters the nutritional composition and microbial community of C. korshinskii silage fermentation. These findings provide empirical evidence for utilizing agricultural by-products to enhance C. korshinskii silage production.

5. Conclusions

This study produces silage feed by mixing corn stalks orS. psammophila with C. korshinskii. The fermentation quality and microbial community were tested, and the results indicated that the silage feed made from the mixture of S. psammophila and C. korshinskii has relatively poor quality. Corn stalks effectively reduced the content of cellulose and lignin in C. korshinskii silage, providing a cost-effective alternative. But its lactic acid content remains lower than that of C. korshinskii silage with added sugar. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing silage practices to enhance feed resource utilization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yongqing Wan and Hao Zhai; methodology, Yongqing Wan; software, Hao Zhai; validation, Mingyu Sun, Siyuan Liu and Dongli Wan; formal analysis, Yongqing Wan and Chaoqun Zhang; investigation, Jinnan Gao; resources, Yongqing Wan, Ruigang Wang and Jinyao Yang; data curation, Hao Zhai and Mingyu Sun; writing—original draft preparation, Hao Zhai; writing—review and editing, Hao Zhai, Yongqing Wan and Chaoqun Zhang; supervision, Yongqing Wan; project administration, Yongqing Wan; funding acquisition, Yongqing Wan and Ruigang Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China (2022MS03035) and the Ordos Science & Technology Plan (2022EEDSKJZDZX017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASH |

ash |

| WSC |

water-soluble carbohydrates |

| CP |

crude protein |

| ADF |

acid detergent fiber |

| NDF |

neutral detergent fiber |

| ADL |

Acid Detergent Lignin |

References

- Kung Jr, L., Shaver, R. D., Grant, R. J., & Schmidt, R. J. Silage review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101(5), 4020–4033.

- Zhang, S. J. , Chaudhry, A. S., Osman, A., Shi, C. Q., Edwards, G. R., Dewhurst, R. J., & Cheng, L. Associative effects of ensiling mixtures of sweet sorghum and alfalfa on nutritive value, fermentation and methane characteristics. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2015, 206, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. , & Liu, B. Effects of planting Caragana shrubs on soil nutrients and stoichiometries in desert steppe of Northwest China. Catena 2019, 183, 104213. [Google Scholar]

- You, J. , Zhang, H., Zhu, H., Xue, Y., Cai, Y., & Zhang, G. Microbial community, fermentation quality, and in vitro degradability of ensiling caragana with lactic acid bacteria and rice bran. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 804429. [Google Scholar]

- Varijakshapanicker, P., Mckune, S., Miller, L., Hendrickx, S., Balehegn, M., Dahl, G. E., & Adesogan, A. T. Sustainable livestock systems to improve human health, nutrition, and economic status. Animal Frontiers 2019, 0(4), 39–50.

- Wang, G. , Chen, Z., Shen, Y., & Yang, X. Efficient prediction of profile mean soil water content for hillslope-scale Caragana korshinskii plantation using temporal stability analysis. Catena 2021, 206, 105491. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F., Usman, S., Huang, W., Jia, M., Kharazian, Z. A., Ran, T., Li, F., Ding, Z., & Guo, X. Effects of inoculating feruloyl esterase-producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum A1 on ensiling characteristics, in vitro ruminal fermentation and microbiota of alfalfa silage. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2023, 14(1), 43.

- Cai, Y., Du, Z., Yamasaki, S., Nguluve, D., Tinga, B., Macome, F., & Oya, T. Community of natural lactic acid bacteria and silage fermentation of corn stover and sugarcane tops in Africa. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 2019, 33(8), 1252.

- Xiong, Y., Xu, J., Guo, L., Chen, F., Jiang, D., Lin, Y., Guo, C., Li, X., Chen, Y., Ni, K., & Yang, F. Exploring the Effects of Different Bacteria Additives on Fermentation Quality, Microbial Community and In Vitro Gas Production of Forage Oat Silage. Animals 2022, 12(9), 1122.

- Hao, M. , Feng, Y., Shi, Y., Shen, H., Hu, H., Luo, Y., Xu, L., Kang, J., Xing, A., Wang, S., & Fang, J. Yield and quality properties of silage maize and their influencing factors in China. Science China Life sciences 2022, 65(8), 1655–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. , Li, X., Guan, H., Huang, L., Ma, X., Peng, Y., Li, Z., Nie, G., Zhou, J., Yang, W., Cai, Y., & Zhang, X. Microbial community and fermentation characteristic of Italian ryegrass silage prepared with corn stover and lactic acid bacteria. Bioresource Technology 2019, 279, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muck, R. E., Nadeau, E. M. G., McAllister, T. A., Contreras-Govea, F. E., Santos, M. C., & Kung, L., Jr. Silage review: Recent advances and future uses of silage additives. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101(5), 3980–4000.

- Ren, H. , Sun, W., Yan, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Song, B., Zheng, Y., & Li, J. Bioaugmentation of sweet sorghum ensiling with rumen fluid: fermentation characteristics, chemical composition, microbial community, and enzymatic digestibility of silages. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 294, 126308. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X. , Wang, S., Zhao, J., Dong, Z., Li, J., Liu, Q., Sun, F., & Shao, T. Effect of ensiling alfalfa with citric acid residue on fermentation quality and aerobic stability. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2020, 269, 114622. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Zhao, J., Dong, Z., Li, J., Kaka, N. A., & Shao, T. Sequencing and microbiota transplantation to determine the role of microbiota on the fermentation type of oat silage. Bioresource Technology 2020, 309, 123371. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Li, J., Zhao, J., Dong, Z., Dong, D., & Shao, T. Silage fermentation characteristics and microbial diversity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in response to exogenous microbiota from temperate grasses. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. , Zhang, Y., Ren, H. Q., Geng, J. J., Xu, K., Huang, H., & Ding, L. L. Physicochemical characteristics and microbial community evolution of biofilms during the start-up period in a moving bed biofilm reactor. Bioresource Technology 2015, 180, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dong, L. , Zhang, H., Gao, Y., & Diao, Q. Dynamic profiles of fermentation characteristics and bacterial community composition of Broussonetia papyrifera ensiled with perennial ryegrass. Bioresource Technology 2020, 310, 123396. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. , Sun, Y., Yuan, Z., Kong, X., Wang, Y., Yang, L., Zhang, Y., & Li, D. Effect of microalgae supplementation on the silage quality and anaerobic digestion performance of Manyflower silvergrass. Bioresource Technology 2015, 189, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H. , Wu, J., Gao, L., Yu, J., Yuan, X., Zhu, W., Wang, X., & Cui, Z. Aerobic deterioration of corn stalk silage and its effect on methane production and microbial community dynamics in anaerobic digestion. Bioresource Technology 2018, 250, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grützke, J. , Malorny, B., Hammerl, J. A., Busch, A., Tausch, S. H., Tomaso, H., & Deneke, C. Fishing in the soup–pathogen detection in food safety using metabarcoding and metagenomic sequencing. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Nkosi, B. D. , Meeske, R., Langa, T., Motiang, M. D., Modiba, S., Mkhize, N. R., & Groenewald, I. B. Effects of ensiling forage soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) with or without bacterial inoculants on the fermentation characteristics, aerobic stability and nutrient digestion of the silage by Damara rams. Small Ruminant Research 2016, 134, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L., Jiang, Y., Ling, Q., Na, N., Xu, H., Vyas, D., Adesogan, A., & Xue, Y. Effects of adding pre-fermented fluid prepared from red clover or lucerne on fermentation quality and in vitro digestibility of red clover and lucerne silages. Agriculture 2021, 11(5), 454.

- Bai, C. L. , Zhao, H. P., Jia, M., & Ding, H. J. Progress on research and utilization of caragana intermedia kuang. cv. ordos. Animal Husbandry and Feed Science 2016, 37, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Valk, L. C. , Luttik, M. A., De Ram, C., Pabst, M., van den Broek, M., van Loosdrecht, M. C., & Pronk, J. T. A Novel D-Galacturonate Fermentation Pathway in Lactobacillus suebicus Links Initial Reactions of the Galacturonate-Isomerase Route With the Phosphoketolase Pathway. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10, 3027. [Google Scholar]

- You, S. , Du, S., Ge, G., Wan, T., & Jia, Y. Microbial community and fermentation characteristics of native grass prepared without or with isolated lactic acid bacteria on the Mongolian Plateau. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 731770. [Google Scholar]

- He, L. , Lv, H., Xing, Y., Chen, X., & Zhang, Q. Intrinsic tannins affect ensiling characteristics and proteolysis of Neolamarckia cadamba leaf silage by largely altering bacterial community. Bioresource Technology 2020, 311, 123496. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, O. C. M. , Ogunade, I. M., Weinberg, Z., & Adesogan, A. T. Silage review: Foodborne pathogens in silage and their mitigation by silage additives. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101(5), 4132–4142. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H. , Yang, R., Zhao, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., Huang, M., & Zeng, Q. Recent advances and strategies in process and strain engineering for the production of butyric acid by microbial fermentation. Bioresource Technology 2018, 253, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, S. , Wang, Y., Zhao, J., Dong, Z., Li, J., Nazar, M., Kaka, NA., & Shao, T. Influences of growth stage and ensiling time on fermentation profile, bacterial community compositions and their predicted functionality during ensiling of Italian ryegrass. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2023, 298, 115606. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Du, S., Sun, L., Cheng, Q., Hao, J., Lu, Q., Ge, G., Jia Y., & Jia, Y. Effects of lactic acid bacteria and molasses additives on dynamic fermentation quality and microbial community of native grass silage. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 830121. [Google Scholar]

- Long, S. , Li, X., Yuan, X., Su, R., Pan, J., Chang, Y., Shi, M., Cui, Z., Huang, N., & Wang, J. The Effect of Early and Delayed Harvest on Dynamics of Fermentation Profile, Chemical Composition, and Bacterial Community of King Grass Silage. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 864649. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , & Nishino, N. Changes in the bacterial community and composition of fermentation products during ensiling of wilted Italian ryegrass and wilted guinea grass silages. Animal Science Journal 2013, 84(8), 607–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scherer, R. , Gerlach, K., & Südekum, K. H. Biogenic amines and gamma-amino butyric acid in silages: Formation, occurrence and influence on dry matter intake and ruminant production. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2015, 210, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem, M. , & Hugenholtz, J. Metabolic pathway engineering in lactic acid bacteria. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2003, 14(2), 232–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eder, A. S. , Magrini, F. E., Spengler, A., da Silva, J. T., Beal, L. L., & Paesi, S. Comparison of hydrogen and volatile fatty acid production by Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterobacter aerogenes singly, in co-cultures or in the bioaugmentation of microbial consortium from sugarcane vinasse. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2020, 18, 100638. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. , Dong, Z., Chen, L., Wang, S., & Shao, T. The replacement of whole-plant corn with bamboo shoot shell on the fermentation quality, chemical composition, aerobic stability and in vitro digestibility of total mixed ration silage. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2020, 259, 114348. [Google Scholar]

- Su, R. , Ni, K., Wang, T., Yang, X., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Jie, C., & Zhong, J. Effects of ferulic acid esterase-producing Lactobacillus fermentum and cellulase additives on the fermentation quality and microbial community of alfalfa silage. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zi, X. , Li, M., Yu, D., Tang, J., Zhou, H., & Chen, Y. Natural Fermentation Quality and Bacterial Community of 12 Pennisetum sinese Varieties in Southern China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 627820. [Google Scholar]

- Nsereko, V. L. , & Rooke, J. A. Effects of peptidase inhibitors and other additives on fermentation and nitrogen distribution in perennial ryegrass silage. Journal of the Science of Food & Agriculture 1999, 79(5), 679–686.

- Dong, Z. , Li, J., Chen, L., Wang, S., & Shao, T. Effects of Freeze-Thaw Event on Microbial Community Dynamics During Red Clover Ensiling. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 1559. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Zhang, G., Zhang, P., Ma, X., Li, F., Zhang, H., Tao, X., Ye, J., & Nabi, M. Rumen fluid fermentation for enhancement of hydrolysis and acidification of grass clipping. Journal of environmental management 2018, 220, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, W. , Jiang, Z., Wang, C., Xu, B., Lu, Z., Wang, F., Zong, X., Jin, M., & Wang, Y. Dynamics of defatted rice bran in physicochemical characteristics, microbiota and metabolic functions during two-stage co-fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2022, 362, 109489. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, K. , Abbas, M., Meng, L., Cai, H., Peng, Z., Li, Q., EI-Sappah, AH., Yan, L., & Zhao, X. Analysis of the fungal diversity and community structure in Sichuan dark tea during pile-fermentation. Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 706714. [Google Scholar]

- Brusotti, G. , Cesari, I., Dentamaro, A., Caccialanza, G., & Massolini, G. Isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from plant resources: the role of analysis in the ethnopharmacological approach. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2014, 87, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Souza, M. L. , Ribeiro, L. S., Miguel, M. G. D. C. P., Batista, L. R., Schwan, R. F., Medeiros, F. H., & Silva, C. F. Yeasts prevent ochratoxin A contamination in coffee by displacing Aspergillus carbonarius. Biological Control 2021, 155, 104512. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Li, J., Zhao, J., Dong, Z., Dong, D., & Shao, T. Effect of epiphytic microbiota from napiergrass and Sudan grass on fermentation characteristics and bacterial community in oat silage. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2022, 132(2), 919–932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romero, J. J. , Park, J., Joo, Y., Zhao, Y., Killerby, M., Reyes, D. C., Tiezzi, F., Gutierrez-Rodriguez, E., & Castillo, M. S. A combination of Lactobacillus buchneri and Pediococcus pentosaceus extended the aerobic stability of conventional and brown midrib mutants–corn hybrids ensiled at low dry matter concentrations by causing a major shift in their bacterial and fungal community. Journal of Animal Science 2021, 99(8), skab141.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).