Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Environmental Effects of Soil Degradation/Contamination

2.1. Loss of Soil Fertility

2.2. Water Pollution

2.3. Decreased Biodiversity

2.4. Erosion

2.5. Increased Greenhouse Gas Emissions

2.6. Impact on Food Safety

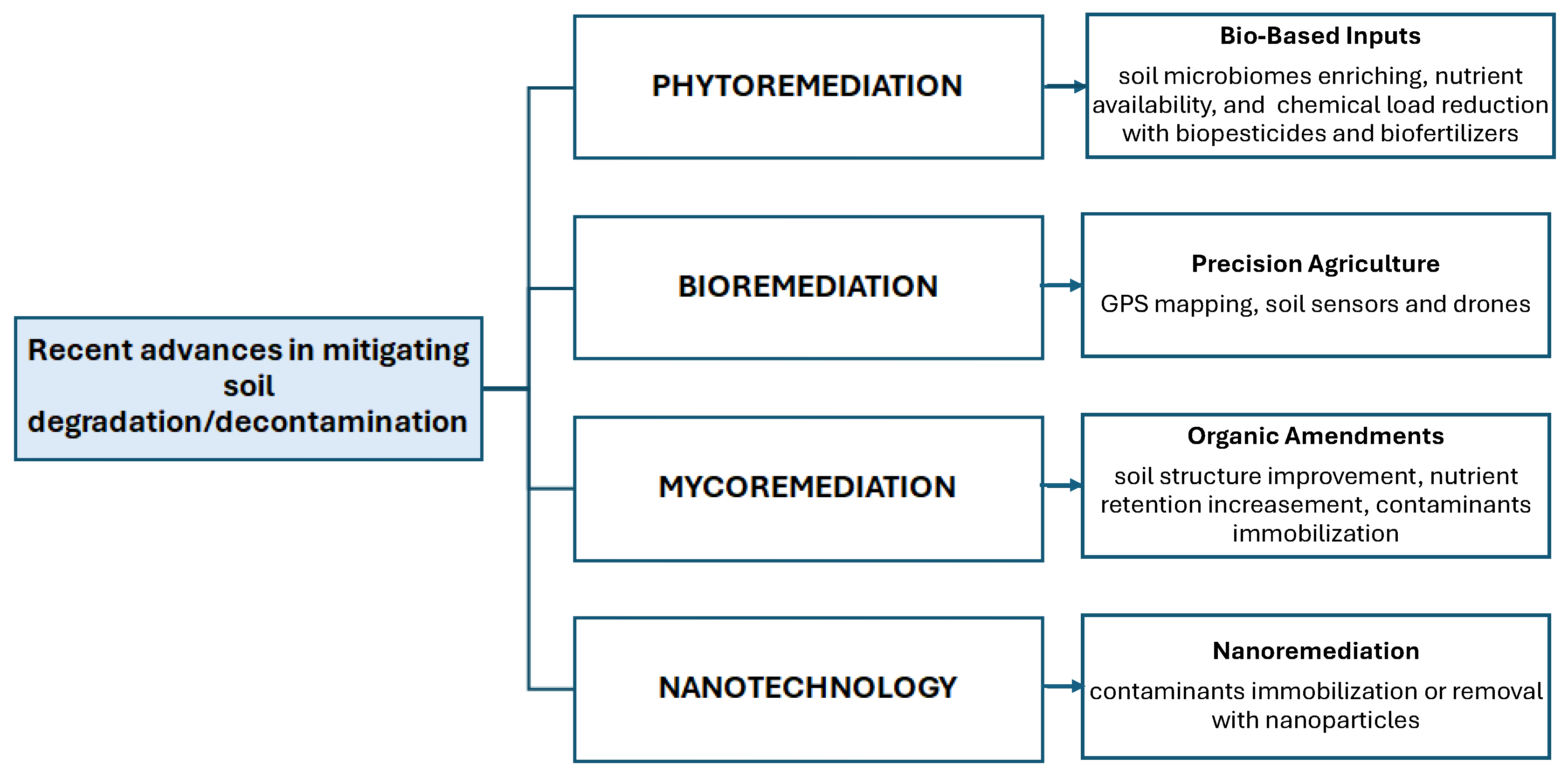

3. Recent Advances in Mitigating Soil Degradation/Decontamination

4. Benefits of Using Mixtures on Soil Degradation/Decontamination

4.1. Dolomite–Sewage Sludge Mixture for Soil Quality Enhancement

- -

- Soil fertility restoration via mineral and organic nutrient input.

- -

- pH correction and nutrient balance, particularly in acidic and depleted soils.

- -

- Improved soil structure due to organic matter promoting aggregation.

- -

- Resource recycling, aligning with EU circular economy goals.

4.2. Dolomite–Stainless Steel Slag Mixture for Petroleum Hydrocarbon Remediation

4.3. Dolomite–Zeolite Mixture for Heavy Metal Immobilization

- -

- pH regulation and metal immobilization: Dolomite raises soil pH, decreasing metal solubility, while zeolite’s high cation exchange capacity adsorbs heavy metals, reducing their mobility and uptake.

- -

- Sustained environmental safety: Over two years, the treatment kept metal bioavailability low, although caution is advised regarding potential re-mobilization of metals after the liming effect diminishes.

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Towards a Thematic Strategy for Soil Protection [COM (2002) 179 final]. 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2002:0179:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Nunes, F.C.; Alves, L.J.; Cseko, C.; de Carvalho, N.; de Gross, E.M.; Soares, T.; Narasimha, M.; Prasad, V. Chapter 9 - Soil as a complex ecological system for meeting food and nutritional security. In Climate Change and Soil Interactions, Narasimha, M., 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Montanarella, L.; Pennock, D.J.; McKenzie, N.; Badraoui, M.; Chude, V.; Baptista, I.; Mamo, T.; Yemefack, M.; Aulakh, M.S.; Yagi, K.; et al. World's soils are under threat. SOIL 2016, 2, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlemann, J.P.; Tanner, E.V.; Hiederer, R.; Kapos, V. Global soil carbon: understanding and managing the largest terrestrial carbon pool. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Hübner, R.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Stagnating crop yields: An overlooked risk for the carbon balance of agricultural soils? Sci. Total. Environ. 2015, 536, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, P.; Eskridge, K.M.; Cassman, K.G. Distinguishing between yield advances and yield plateaus in historical crop production trends. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Harvey, C.; Resosudarmo, P.; Sinclair, K.; Kurz, D.; McNair, M.; Crist, S.; Shpritz, L.; Fitton, L.; Saffouri, R.; et al. Environmental and Economic Costs of Soil Erosion and Conservation Benefits. Science 1995, 267, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A. Land Resources: Now and for the Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Enhancing crop yields in the developing countries through restoration of the soil organic carbon pool in agricultural lands. Land Degrad. Dev. 2005, 17, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D. Soil Erosion: A Food and Environmental Threat. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2006, 8, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. Personal communication. 18 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roose, E.J.; Lal, R.; Feller, C.; Barthes, B.; Stewart, B.A. (Eds.) Soil Erosion and Carbon Dynamics, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, B.; Xu, D.; Gao, L.; Yin, S. Heavy metal pollution in sediments of the largest reservoir (Three Gorges Reservoir) in China: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 20844–20858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsova, N.; Motuzova, G.; Kolchanova, K.; Stepanov, A.; Karpukhin, M.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S. The effect of humic substances on Cu migration in the soil profile. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 35, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-P.; Bi, Q.-F.; Qiu, L.-L.; Li, K.-J.; Yang, X.-R.; Lin, X.-Y. Increased risk of phosphorus and metal leaching from paddy soils after excessive manure application: Insights from a mesocosm study. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 666, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, J.; Błońska, E.; Łyszczarz, S.; Tibbett, M. Forest Humus Type Governs Heavy Metal Accumulation in Specific Organic Matter Fractions. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, K.; Wick, A.F.; DeSutter, T.; Chatterjee, A.; Harmon, J. Soil Salinity: A Threat to Global Food Security. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 2189–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Quillérou, E.; Nangia, V.; Murtaza, G.; Singh, M.; Thomas, R.; Drechsel, P.; Noble, A. Economics of salt-induced land degradation and restoration. Nat. Resour. Forum 2014, 38, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOLAW) – Managing Systems at Risk; FAO: Rome, Italy; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shahtahmassebi, A.R.; Song, J.; Zheng, Q.; Blackburn, G.A.; Wang, K.; Huang, L.Y.; Pan, Y.; Moore, N.; Shahtahmassebi, G.; Haghighi, R.S.; et al. Remote sensing of impervious surface growth: A framework for quantifying urban expansion and re-densification mechanisms. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2016, 46, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation. Bioscience 2002, 52, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero-Sierra, C.; Marques, M.; Ruíz-Pérez, M. The case of urban sprawl in Spain as an active and irreversible driving force for desertification. J. Arid. Environ. 2013, 90, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyński, P.; Plak, A.; Hanaka, A. Influence of the soil sealing on the geoaccumulation index of heavy metals and various pollution factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 24, 4801–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G. Impact of land-take on the land resource base for crop production in the European Union. Sci. Total. Environ. 2012, 435-436, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettri, B.; Singha, N.A.; Singh, A.K. Efficiency and kinetics of Assam crude oil degradation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus sp. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 5793–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, C.; Spada, V.; Sciarrillo, R. Assessment of three approaches of bioremediation (Natural Attenuation, Landfarming and Bioagumentation – Assistited Landfarming) for a petroleum hydrocarbons contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2017, 170, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, G.; Tafese, T.; Abda, E.M.; Kamaraj, M.; Assefa, F.; He, Y. Factors Influencing the Bacterial Bioremediation of Hydrocarbon Contaminants in the Soil: Mechanisms and Impacts. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, A.Y.; Gladkov, E.A.; Osipova, E.S.; Gladkova, O.V.; Tereshonok, D.V. Bioremediation of Soil from Petroleum Contamination. Processes 2022, 10, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, L.T.; Yusuff, A.S.; Adeyi, A.A.; Omotara, O.O. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation of crude oil contaminated soil: Process parameters influence. South Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.K.; Bajagain, R.; Jeong, S.-W.; Kim, J. Effect of consortium bioaugmentation and biostimulation on remediation efficiency and bacterial diversity of diesel-contaminated aged soil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo, E.; Madrid, F.; Lara-Moreno, A.; Villaverde, J. Soil bioremediation by cyclodextrins. A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 591, 119943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, D.K.; Kim, J. New insights into bioremediation strategies for oil-contaminated soil in cold environments. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 142, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.K. Sadovnikova, O.O. L.K. Sadovnikova, O.O. Ekologiya H.Z. Sredy, S. Vysshaya Moscow, Russia, 2006; ISBN 5-06-005558-2.; Lifshits, S.K.; Glyaznetsova, Y.; Chalaya, O.N. Self-Regeneration of Oil-Contaminated Soils in the Cryolithozone on the Example of the Territory of the Former Oil Pipeline «Talakan-Vitim». In Proceedings of the INTEREKSPO GEO-SIBIR, Novosibirsk, Russia, pp. 199–206, 2018.

- García-Carmona, M.; Romero-Freire, A.; Aragón, M.S.; Garzón, F.M.; Peinado, F.M. Evaluation of remediation techniques in soils affected by residual contamination with heavy metals and arsenic. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 191, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Kashyap, N. Garg, Arsenic toxicity in crop plants: responses and remediation strategies, in: M. Hasanuzzaman, K. Nahar, M. Fujita (Eds.), Mechanisms of Arsenic Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants, Springer, Singapore, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-T.; Ding, J.; Xiong, C.; Zhu, D.; Li, G.; Jia, X.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Xue, X.-M. Exposure to microplastics lowers arsenic accumulation and alters gut bacterial communities of earthworm Metaphire californica. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union, Directive 2004/107/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15/12/2004 relating to arsenic, cadmium, mercury, nickel and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ambient air, J. Eur. Union L 23 (2005) 3–16.

- Y. Liu, Landscape connectivity in Soil Erosion Research: concepts, implication, quantification. Geogr. Res. Pap. 1 (2016) 195–202.

- Sun, W.; Shao, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhai, J. Assessing the effects of land use and topography on soil erosion on the Loess Plateau in China. CATENA 2014, 121, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Hahad, O.; Daiber, A.; Landrigan, P.J. Soil and water pollution and human health: what should cardiologists worry about? Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 119, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.H.; Jones, R.R.; Brender, J.D.; De Kok, T.M.; Weyer, P.J.; Nolan, B.T.; Villanueva, C.M.; Van Breda, S.G. Drinking Water Nitrate and Human Health: An Updated Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.O. (Ed.) Biodiversity; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wagg, C.; Bender, S.F.; Widmer, F.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 5266–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, ITPS, GSBI, SCBD, EC. State of knowledge of soil biodiversity—Status, challenges and potentialities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, D.H.; Bardgett, R.D.; Behan-Pelletier, V.; Herrick, J.E.; Jones, T.H.; Ritz, K.; Six, J.; Strong, D.R.; van der Putten, W.H. Soil Ecology and Ecosystem Services. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil degradation by erosion. Land Degrad. Dev. 2001, 12, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashagaluke, J.B.; Logah, V.; Opoku, A.; Sarkodie-Addo, J.; Quansah, C.; Marelli, B. Soil nutrient loss through erosion: Impact of different cropping systems and soil amendments in Ghana. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0208250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.P.; Bressiani, D.; Ebling, É.D.; Reichert, J.M. Best management practices to reduce soil erosion and change water balance components in watersheds under grain and dairy production. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil Structure and Sustainability. J. Sustain. Agric. 1991, 1, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, J.N.; Fiener, P. Soil erosion on arable land: An unresolved global environmental threat. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2023, 48, 136–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuazo, V.D.; Pleguezuelo, C.R.R. Soil-Erosion and Runoff Prevention by Plant Covers: A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 28, 785–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyssels, G.; Poesen, J.; Bochet, E.; Li, Y. Impact of plant roots on the resistance of soils to erosion by water: a review. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2005, 29, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.; Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A. Transformation of the Nitrogen Cycle: Recent Trends, Questions, and Potential Solutions. Science 2008, 320, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; van Drecht, G. Current and historical population and land cover. In: Bouwman, A.F., Kram, T., Klein Goldewijk, K. (Eds.), Integrated Modelling of Global Environmental Change. An overview of IMAGE 2.4. Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 2006; pp. 93–112.

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Beusen, A.; van Drecht, G.; De Vos, M. The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 20(1) (2011) 73–86.

- Reay, D.S.; Davidson, E.A.; Smith, K.A.; Smith, P.; Melillo, J.M.; Dentener, F.; Crutzen, P.J. Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mer, J.; Roger, P. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2001, 37, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil degradation by erosion. Land Degrad. Dev. 2001, 12, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Ahlström, A.; Hobbie, S.E.; Reich, P.B.; Nieradzik, L.P.; Staver, A.C.; Scharenbroch, B.C.; Jumpponen, A.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Randerson, J.T.; et al. Fire frequency drives decadal changes in soil carbon and nitrogen and ecosystem productivity. Nature 2017, 553, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.D.; Phelps, J.; Yuen, J.Q.; Webb, E.L.; Lawrence, D.; Fox, J.M.; Bruun, T.B.; Leisz, S.J.; Ryan, C.M.; Dressler, W.; et al. Carbon outcomes of major land-cover transitions in SE Asia: great uncertainties and REDD + policy implications. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 3087–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certini, G. Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia 2005, 143, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO and ITPS. Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR) – Main Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Rabl, A.; de Kok, T.M.; Drews, M.; Friedrich, R.; Hertel, O.; Holland, M.; Klimont, Z.; Matsuoka, Y.; Mayorga, E.; et al. Estimating the costs of nitrogen pollution in Europe and the effects of measures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 3571–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Singh, S. Heavy metals in vegetables: Screening health risks involved in cultivation along wastewater drain and irrigated river in India. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2014, 49, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Van Liedekerke, M.; Yigini, Y.; Montanarella, L. Contaminated Sites in Europe: Review of the Current Situation Based on Data Collected through a European Network. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2013, 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, W.E.H.; Nortcliff, S. Soils and food security. In: Brevik, E.C., Burgess, L.C. (Eds.), Soils and Human Health. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 299–321.

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.R.; Aktoprakligil, D.; Ozdemir, A.; Vertii, A. Turk. J. Bot. 25(3) (2001) 111–121.

- Nedjimi, B.; Daoud, Y. Flora: Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 204(4) (2009) 316–324.

- Dalvi, A.A.; Bhalerao, S.A. Ann. Plant Sci. 2(9) (2013) 362–368.

- Fourati, E.; Wali, M.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Abdelly, C.; Ghnaya, T. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 108 (2016) 295–303.

- Jacobs, A.; Drouet, T.; Noret, N. Plant Soil 430 (2018) 381–394.

- Ghazaryan, K.A.; Movsesyan, H.S.; Minkina, T.M.; Sushkova, S.N.; Rajput, V.D. Environ. Geochem. Health 43 (2021) 1327–1335.

- Yang, W.J.; Gu, J.F.; Zhou, H.; Huang, F.; Yuan, T.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liao, B.H. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (2020) 16134–16144.

- Khalid, A.; Farid, M.; Zubair, M.; Rizwan, M.; Iftikhar, U.; Ishaq, H.K.; Ali, S. Int. J. Environ. Res. 14 (2020) 243–255.

- Das, P.; Datta, R.; Makris, K.C.; Sarkar, D. Environ. Pollut. 158(5) (2010) 1980–1983.

- Hannink, N.K.; Subramanian, M.; Rosser, S.J.; Basran, A.; Murray, J.A.; Shanks, J.V.; Bruce, N.C. Int. J. Phytorem. 9(5) (2007) 385–401.

- Just, C.L.; Schnoor, J.L. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38(1) (2004) 290–295.

- Sampaio, C.J.; de Souza, J.R.; Damiao, A.O.; Bahiense, T.C.; Roque, M.R. Biotechnology 9 (2019) 1–10.

- Mahar, A.; Wang, P.; Ali, A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Lahori, A.H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 126 (2016) 111–121.

- Nedjimi, B.; Daoud, Y. Flora: Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 204(4) (2009) 316–324.

- Tome, F.V.; Rodrıguez, P.B.; Lozano, J.C. Sci. Total Environ. 393(2–3) (2008) 351–357.

- Rezania, S.; Taib, S.M.; Din, M.F.M.; Dahalan, F.A.; Kamyab, H. J. Hazard. Mater. 318 (2016) 587–599.

- Dhanwal, P.; Kumar, A.; Dudeja, S.; Chhokar, V.; Beniwal, V. Advanced Environmental Biotechnology; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Al Chami, Z.; Amer, N.; Al Bitar, L.; Cavoski, I. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 12 (2015) 3957–3970.

- Monaci, F.; Trigueros, D.; Mingorance, M.D.; Rossini-Oliva, S. Environ. Geochem. Health 42 (2020) 2345–2360.

- Bacchetta, G.; Boi, M.E.; Cappai, G.; De Giudici, G.; Piredda, M.; Porceddu, M. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 101(6) (2018) 758–765.

- Macaulay, B.; Rees, D. Bioremediation of oil spills: a review of challenges for research advancement. Ann. Environ. Sci. 8 (2014) 9–37.

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants: An Overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Pan, H.; Wang, Q.; Ge, Y.; Liu, W.; Christie, P. Enrichment of the soil microbial community in the bioremediation of a petroleum-contaminated soil amended with rice straw or sawdust. Chemosphere 2019, 224, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. Mycoremediation (bioremediation with fungi) – growing mushrooms to clean the earth. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2014, 26, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yadav, A.N.; Mondal, R.; Kour, D.; Subrahmanyam, G.; Shabnam, A.A.; Khan, S.A.; Yadav, K.K.; Sharma, G.K.; Cabral-Pinto, M.; et al. Myco-remediation: A mechanistic understanding of contaminants alleviation from natural environment and future prospect. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpasi, S.O.; Anekwe, I.M.S.; Tetteh, E.K.; Amune, U.O.; Shoyiga, H.O.; Mahlangu, T.P.; Kiambi, S.L. Mycoremediation as a Potentially Promising Technology: Current Status and Prospects—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekrami, E.; Pouresmaieli, M.; Hashemiyoon, E.S.; Noorbakhsh, N.; Mahmoudifard, M. Nanotechnology: A sustainable solution for heavy metals remediation. Environ. Nanotechnology, Monit. Manag. 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.D.; Attia, M.F.; Whitehead, D.C.; Alexis, F. Nanotechnology for Environmental Remediation: Materials and Applications. Molecules 2018, 23, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Joshi, H. Application of nanotechnology in the remediation of contaminated groundwater: a short review. Rec. Res. Sci. Technol. 2(6) (2010) 51–57.

- Mueller, N.C.; Nowack, B. Nanoparticles for Remediation: Solving Big Problems with Little Particles. Elements 2010, 6, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, W.; Tsang, P.E.; Fang, J.; Zhao, D. Remediation of lead contaminated soil by biochar-supported nano-hydroxyapatite. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 132, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisman, V.; Georgescu, P.L.; Ghisman, G.; Buruiana, D.L. A New Composite Material with Environmental Implications for Sustainable Agriculture. Materials 2023, 16, 6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruiana, D.-L.; Benea, L.; Ghisman, V.; Arama, P.C.; Ghisman, G. Sewage sludge-based composition with a fertilizing role. RO138471 (A0), National. OSIM patent 11 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 86/278/EEC on the Protection of the Environment, and in Particular of the Soil, When Sewage Sludge Is Used in Agriculture. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1986, L181, 6–12. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31986L0278.

- Fytili, D.; Zabaniotou, A. Utilization of sewage sludge in EU application of old and new methods—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruiana, D.L.; Obreja, C.-D.; Herbei, E.E.; Ghisman, V. Re-Use of Silico-Manganese Slag. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisman, V.; Muresan, A.C.; Buruiana, D.L.; Axente, E.R. Waste slag benefits for correction of soil acidity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhille, J.; Goedemé, T.; Penne, T.; Van Thielen, L.; Storms, B. Measuring water affordability in developed economies. The added value of a needs-based approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Park, M. Assessment of Quantitative Standards for Mega-Drought Using Data on Drought Damages. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruiana, D.L.; Georgescu, P.L.; Ghisman, V.; Bogatu, N.L.; Ghisman, G.; Axente, E.R.; Arama, C. Petroleum hydrocarbon absorption mixture using dolomite. RO137696 (A0), National. OSIM patent 10 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vrînceanu, N.; Motelică, D.; Dumitru, M.; Calciu, I.; Tănase, V.; Preda, M. Assessment of using bentonite, dolomite, natural zeolite and manure for the immobilization of heavy metals in a contaminated soil: The Copșa Mică case study (Romania). CATENA 2019, 176, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).