1. Introduction

As of 2020, 76 countries or regions worldwide had entered the stage of universal higher education (UNESCO, 2020). However, increased access to higher education has not automatically translated into improved employment outcomes. On the contrary, it has led to structural mismatches in some contexts, such as academic inflation and underemployment (Trow, 2007; Figueiredo et al., 2017). According to the latest OECD (2025) survey, rapidly growing numbers of students are uncertain about their career plans, which is linked to poorer long-term employment outcomes. Additionally, structural shifts in the labor market driven by ongoing economic transformations have made job searches increasingly challenging (Guo & Xiao, 2024). Taken together, the global expansion of higher education and labor market restructuring are jointly shaping how undergraduates form and refine their career orientation.

In East Asia, China’s universities of applied sciences (UAS), which are the main drivers of universal higher education, are now facing mounting challenges. Higher education expansion coincided with China’s transition from a planned to a market-based economy, leading to intensified labor market polarization, a trend projected to escalate under skill-biased technological change (Zhou & Gao, 2025; Yang, 2024). As a result, declining demand for middle-skilled labor has further constrained employment opportunities for UAS graduates. Meanwhile, many UAS have experienced academic drift in their pursuit of prestige, gradually weakening their alignment with regional industry needs (Jing & Welch, 2018). Consequently, students often enter the workforce with limited career preparation and unclear employment goals (West, 2000). More critically, students in UAS typically come from underprivileged backgrounds and often lack early exposure to structured career education. Once enrolled, they also encounter limited institutional resources and underdeveloped support systems, which severely undermine the development of clear career orientation (Nießen et al. 2022). Evidence from EU countries further shows that students in applied universities frequently drop out due to poor career decision-making, low career decidedness, misalignment between aspirations and curricula, and lack of access to meaningful internships or apprenticeships (Bargmann et al., 2022). These issues point to a deeper crisis, not only in the institutional viability of UAS but also in their students’ capacity to formulate career orientation. This highlights the urgent need for institutional interventions, including the provision of effective career education.

Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976), through their classic block experiment, demonstrated that effective learning and development require “tutoring” within the learner’s zone of proximal development (ZPD) from “experts”. They extended this concept into what is now known as instructional scaffolding, which enables individuals to move from inability to independence (Van Der Stuyf, 2002). For students in UAS, developing a clear career orientation is often a novel and challenging task, one that may be unfamiliar even to students in more research-intensive institutions. In this context, career advising functions as a crucial scaffold. It not only helps students begin identifying career options but also facilitates goal clarification, dialogic feedback, and motivational support, all of which serve as essential starting points for the formation of career orientation. Recent studies have confirmed the applicability of this scaffolding mechanism. For instance, Zammitti et al. (2023) demonstrated through experiments that group career counseling could effectively promote psychological resources that help university students build coherent career paths. Furthermore, career advising interventions foster proactive behaviors in students, which are foundational to the development of value-driven and self-regulated career orientations (Elgeddawy et al., 2023).

To build this mechanism, universities worldwide have established career centers that integrate practical activities, assessment, and mentoring services (Lee & Goh, 2003; Schlesinger et al., 2021). However, in many developing countries, professional career guidance remains a nascent and under-resourced field. For example, research in Pakistan revealed that students express urgent and diverse needs for career counseling, yet availability remains extremely limited (Keshf & Khanum, 2021). In contexts where professional counseling infrastructure is lacking, building a broader, more accessible system of career advising may serve as a more feasible foundation. In China, for instance, the government has mandated that universities implement a comprehensive system that integrates career advising with both academic learning and extracurricular activities. Career advising in Chinese universities has been rolled out nationwide, with dedicated personnel assigned to the task (Yang et al. 2024). Furthermore, university counselors are expected to maintain regular contact with each student to provide personalized career guidance.

Despite these efforts, several limitations persist in the existing literature on career advising. First, it tends to overemphasize its direct effects, such as enhancing employability or reducing career anxiety, while overlooking the mechanisms through which advising indirectly shapes career orientation via students’ behavioral engagement (Prescod et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). Second, many studies reduce career advising to mere information provision or isolated course modules, failing to capture its deeper function as a developmental support system (Crookston, 1972; Luff, 2021). Third, most related research has been conducted in Western contexts, with limited attention paid to how career advising is adapted to the evolving landscape of universal higher education, especially in developing countries where student populations are increasingly diverse and career goals are often ambiguous.

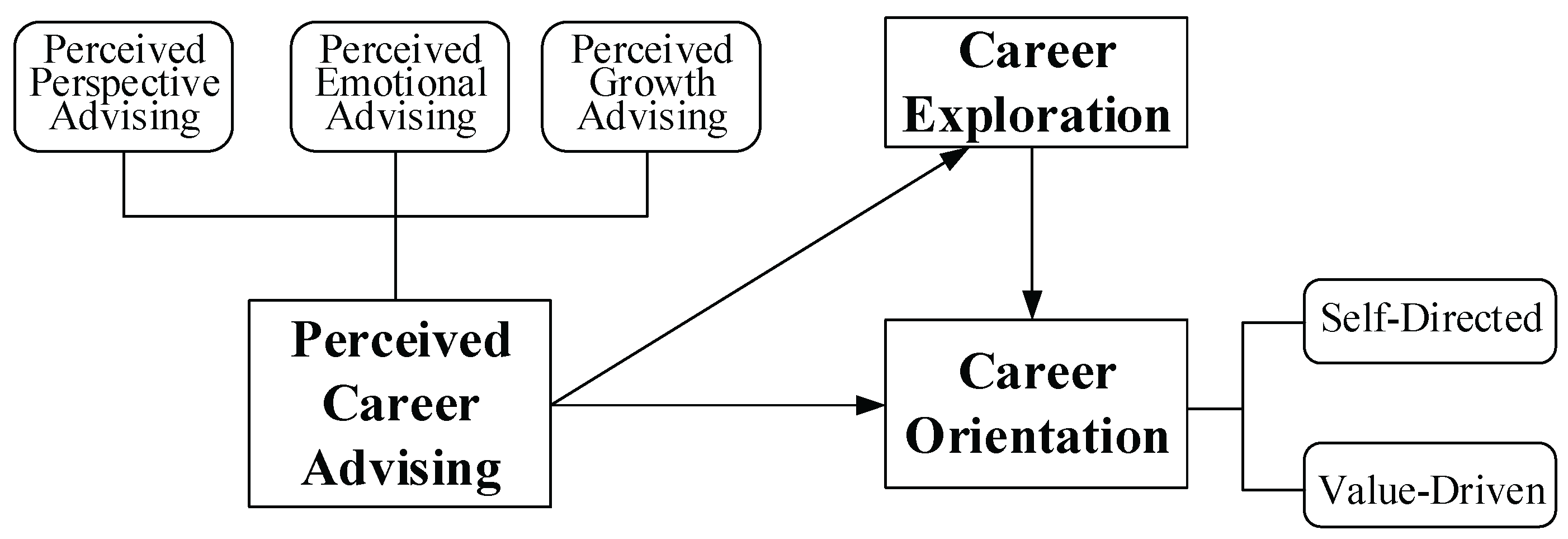

To address these gaps, this study aims to examine how students’ perceived career advising fosters the formation of career orientation by stimulating their exploratory behavior. This study conceptualizes perceived career advising as a multidimensional construct, including perspective advising, emotional advising, and growth advising. It introduces career exploration as a mediating variable between perceived advising and career orientation. Drawing on rigorously sampled data from UAS in China and using structural equation modeling, this study empirically tests the indirect pathway from career advising to career orientation. The findings are expected to enrich theories of developmental advising and inform effective practices in career education.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation and Framework

The conceptual model of this study is grounded in the Social Cognitive Model of Career Self-Management (CSM) proposed by Lent and Brown (2013), which emphasizes individuals’ proactive role in managing their career development across diverse educational and occupational contexts. To contextualize how external support facilitates such development, this study also draws on the concept of instructional scaffolding proposed by Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976) to illustrate how career advising enables students’ transition from career uncertainty to clarity. Within the CSM framework, particular attention is given to students’ perceptions of career advising in forms such as verbal persuasion, emotional encouragement, and resource provision, which influence both career-related behaviors and beliefs (Lent et al., 2000; 2013). Rather than acting solely as a direct predictor of outcomes, career advising in this study is theorized to activate and sustain students’ exploratory behavior, serving as a catalyst for behavioral engagement (Stipanovic et al., 2017).

Career orientation, as the developmental outcome in this model, reflects students’ internalized career direction and decision rationality. Its formation is viewed as the culmination of both institutional scaffolding and individual engagement. Thus, this study adopts a process-oriented framework, positing that perceived career advising influences career orientation indirectly through its effect on career exploration. This mediational structure reflects the pathway from contextual scaffolding to behavioral action and psychological consolidation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual farmwork.

Figure 1.

Conceptual farmwork.

2.2. Career Advising and Perceived Career Advising

Career advising constitutes a structured developmental intervention designed to support individuals in making informed and meaningful career decisions by providing them with resources, guidance, and reflective engagement opportunities (Hughey et al., 2012). Distinct from general career guidance or employment counseling, career advising in higher education is increasingly understood as a developmental alliance—a sustained, student-centered support system that spans information dissemination, emotional regulation, and motivational scaffolding (Schlosser et al., 2011). Grounded in Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994), career advising can be conceptualized as a form of contextual support that influences individuals’ career self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goal-setting behaviors. As a form of social persuasion and vicarious experience, advising helps recalibrate students’ cognitive appraisals of the career environment and enables them to construct future-oriented plans (Zammitti et al., 2023). Drawing more broadly from Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986), career advising functions as an experience-sharing and self-regulatory mechanism that influences behavior through cognitive reframing and emotional support (Luzzo & Day, 1999).

The conceptualization of career advising adopted in this study draws from the developmental tradition of academic advising, particularly the seminal work of Crookston (1972), who viewed advising not merely as a transactional process of information delivery, but as a pedagogical and developmental engagement. In his influential article A Developmental View of Academic Advising as Teaching, Crookston proposed that advising should be understood as an intentional, student-centered, and educational act aimed at promoting students’ self-understanding, decision-making capacity, and long-term life planning. Although Crookston’s focus was originally on academic advising, his underlying framework was deeply intertwined with career development goals, positing advising as a means of empowering students to navigate both educational and vocational pathways.

Building on this view, recent scholarship has further elaborated the developmental advising paradigm, emphasizing the affective, motivational, and future-oriented dimensions of advising interactions (Luff, 1994; Troxel et al., 2021). This developmental stance departs from purely prescriptive or administrative models by foregrounding the advisor-advisee relationship as a space for emotional validation, personal growth, and goal internalization. In the context of Chinese higher education, career advising typically operates within an institutionalized tripartite framework: (a) domain-specific knowledge transmission from faculty members, (b) structured planning and follow-up support from professional advisors, and (c) tacit knowledge exchange within peer groups (Wei et al., 2016). This multidimensional framework fulfills a distinctive psychosocial function, providing scaffolding for students’ career development through cognitive apprenticeship and within communities of practice (Lynch & Lungrin, 2018).

Accordingly, the present study conceptualizes perceived career advising as a multidimensional construct encompassing not only informational and strategic dimensions, but also emotional and growth-oriented dimensions that align with students’ evolving career identity and orientation. Integrating more recent elaborations, the current study identifies three dimensions of perceived career advising: perceived perspective advising, perceived emotional advising, and perceived growth advising. The latter two are part of Crookston’s developmental advising framework.

2.3. Career Orientation and Perceived Career Advising

2.3.1. Career Orientation

Career orientation refers to an individual’s cognitive and motivational approach to managing their career in pursuit of subjective success and self-congruence (Hall, 2004). It captures two key psychological dimensions: decision rationality, reflecting the logic, coherence, and deliberative reasoning behind one’s career choices; and directional clarity, denoting the specificity, certainty, and temporal stability of one’s vocational goals (Pesch et al., 2018). These dimensions are theoretically grounded in the concept of the protean career, which emphasizes individual agency, value alignment, and self-direction in navigating nonlinear and dynamic career environments (Hirschi & Koen, 2021). Based on this, Briscoe and Hall (2006) developed the first Protean Career Attitudes Scale, which includes two dimensions: self-directed and value-driven orientation.

Among university students, career orientation often emerges as an emergent construct, shaped by personal, social, and contextual influences. While this period allows for identity exploration, students frequently confront bounded rationality and ambiguous goal structures, especially in universal higher education systems (Sargent & Domberger, 2007). A 2019 survey of 663 undergraduates in a mid-ranked UK university found that only 64% reported having a clear career plan by graduation (Quinlan & Corbin, 2023). In China, a longitudinal study revealed that while nearly 70% of third-year undergraduates had a preliminary career direction, most lacked a well-articulated rationale for their choices (Niu & Zheng, 2018). These findings suggest that career orientation is not a static trait, but a malleable developmental outcome influenced by external structuring forces and individual readiness.

2.3.2. The Impact of Perceived Career Advising on Career Orientation

Although much of the existing literature on the formation of career orientation has focused on familial, institutional, and broader sociocultural factors, a growing body of research underscores the significant role of structured advising services in enhancing students’ vocational direction awareness and decision-making clarity. Belser et al. (2017) and Prescod et al. (2019) found that participation in career planning courses and one-on-one advising sessions not only increased students’ engagement in career-related activities but also significantly improved their clarity and confidence in making career decisions. Particularly for undergraduates, faculty members serve as epistemic brokers, acting as intermediaries of knowledge who facilitate the transfer of domain-specific tacit knowledge that bridges academic training and occupational realities (Rivera and Li 2020).

Further evidence underscores that career advising plays a vital role in clarifying students’ future perspectives and cognitive frameworks for decision-making. It supports their ability to articulate purposeful goals, weigh options rationally, and construct personally meaningful long-term trajectories (Suryadi et al., 2020). For instance, a randomized controlled trial in China revealed that intensive advising interventions significantly improved students’ sense of agency and career-related adaptability, leading to more proactive career behaviors (Zhang et al., 2023). Similar conclusions have been drawn from studies examining advisory consultations, mentoring relationships, and longitudinal feedback systems, which together enhance students’ capacity to formulate and pursue coherent developmental pathways (Muceldili et al., 2012; Mujib & Purusa, 2022).In the European context, structured advising programs in Romanian universities were reported to enhance career planning and confidence among over 94% of student participants, with 73% noting improved alignment in their career direction (Staiculescu & Dobrea, 2017).

These findings collectively suggest that career advising is not just informational or administrative, but developmental in nature and capable of shaping students’ self-understanding, decision logic, and motivational clarity regarding their futures. Based on these findings, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a. Perceived perspective advising positively influences undergraduates’ self-directed orientation.

H1b. Perceived emotional advising positively influences undergraduates’ self-directed orientation.

H1c. Perceived growth advising positively influences undergraduates’ self-directed orientation.

H2a. Perceived perspective advising positively influences undergraduates’ value-driven orientation.

H2b. Perceived emotional advising positively influences undergraduates’ value-driven orientation.

H2c. Perceived growth advising positively influences undergraduates’ value-driven orientation.

2.4. Career Exploration and Its Mediational Role

The construct of career exploration traces its conceptual roots to Jordaan’s (1963) operational definition, which characterizes it as goal-oriented activities generating self- and occupational knowledge. Building on this foundation, Super’s (1990) life-span theory posits career exploration as a developmental task through which individuals crystallize their vocational self-concept during emerging adulthood. Within higher education contexts, this process entails systematic appraisal of career-relevant environmental affordances (Flum & Blustein, 2000), with recent empirical work emphasizing students’ agentic engagement (Cheung & Arnold, 2014). Empirical evidence delineates three-tiered benefits of career exploration: (a) socio-cognitive differentiation, involving the evaluation of personal values against occupational stereotypes; (b) agentic capacity building, which enhances self-directed career management competencies; and (c) intrapersonal calibration, referring to the alignment of personal aptitudes with career demands (Storme & Celik, 2018).

The mediating role of career exploration is grounded in Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) and goal-setting theories, which posit that environmental affordances (e.g., advising interventions) influence distal outcomes indirectly via activation of agentic career behaviors (Lent et al., 2002; Locke & Latham, 2002). In this view, as a goal-directed behavior, career exploration is typically stimulated by contextual resources such as structured advising, institutional scaffolding, and relational support (Li et al., 2022). In particular, career advising activates exploration by reducing decisional paralysis, offering access to occupational information, and encouraging reflective engagement (Peng et al., 2020; Perdrix et al., 2012). Emotional and developmental support from advisors also buffers the cognitive and affective costs of exploration, thereby increasing students’ willingness to invest in exploratory activities.

At the same time, career exploration is a proximal antecedent of career orientation, as it allows students to gradually clarify goals, assess value congruence, and commit to personally meaningful directions (Dozier et al., 2015; Hirschi & Pang, 2023). It transforms abstract career intentions into actionable plans and reinforces directional clarity through iterative feedback. From this perspective, exploration serves as a developmental mechanism that translates external advising into internalized structural orientation (Gati & Asher, 2001). Based on these findings, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a-c. Perceived career advising (perceived perspective advising/perceived emotional advising/perceived growth advising) positively influences undergraduates’ career exploration.

H4a-b. Career exploration positively influences undergraduates’ career orientation (self-directed orientation/value-driven orientation).

H5. Career exploration mediates the impact of perceived career advising on undergraduates’ career orientation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling

After validating the questionnaire through a pilot study, we conducted formal data collection from University S, China in January 2025. It was selected due to its median ranking among national universities and its representative characteristics as UAS. University S comprises 13 faculties, 11 of which offer undergraduate programs spanning a diverse range of academic disciplines, including engineering and technology, and social sciences. This broad disciplinary coverage enhances the generalizability of the study findings, making it a suitable representation of UAS.

As of December 2024, the University S enrolled approximately 18,000 undergraduate students. Stratified random sampling was stratified proportionally by majors and grade levels based on the university’s official enrollment data. A 20% sample of the student population was drawn, and we obtained 3,138 valid responses after screening. Overall, the sample consisted of 2,007 male students (64%) and 1,131 female students (36%). Most students (81.89%) were enrolled in engineering and technology-related subjects, while the remaining students pursued majors in public administration, labor and social security, business administration, and other related fields. The distribution of students by grade level was as follows: 1,128 (35.9%), 879 (28%), 668 (21.3%), and 463 (14.8%).

The survey plan and instruments, as well as the overall research protocol, were approved by the institutional ethics review board. Before participation, students received a written consent form detailing the study’s purpose, anonymity assurances, data confidentiality, and potential risks.

3.2. Variable Measurement

A questionnaire was designed to investigate undergraduates’ career advising experiences and assess their level of career orientation. The instrument primarily measured perceived career advising, career exploration, and career orientation, all measured using a five-point Likert scale.

3.2.1. Perceived Career Advising Scale

To systematically capture the developmental role of career advising, this study developed a multidimensional Perceived Career Advising Scale, comprising three subdimensions: perceived perspective advising, perceived emotional advising, and perceived growth advising. This construct emphasizes the student-centered nature of advising, recognizing that its impact depends not only on the content delivered but also on how such support is subjectively understood and internalized by students (Bandura, 1997; Lent & Brown, 2013). Importantly, this framework includes both formal and informal advising agents, acknowledging that in resource-constrained institutional settings such as Chinese universities of applied sciences (UAS), effective support may come from peers, teachers, family members, or counselors. The conceptualization of career advising was primarily informed by Crookston’s (1972) developmental advising model, which views advising not as a transactional or administrative task but as an educational dialogue that fosters students’ reflective thinking and goal setting.

Initial items were generated based on a systematic review of prior advising literature, including career development programs and advising handbooks (e.g., Hughey et al., 2012). These items were then refined through expert review by three higher education specialists to ensure content validity and cultural fit. Cultural adaptation was particularly important, as advising practices in Chinese UAS contexts often extend beyond trained professionals to include academic or administrative personnel with varying levels of guidance experience. Sample items include “Helped me identify opportunities for career development,” “Helped me alleviate stress,” and “Made me grow into a better person.” Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) validated the scale, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.869 in the pilot study and 0.939 in the formal survey, indicating high reliability.

3.2.2. Career Orientation Scale

Career orientation was measured using the protean career orientation scale adapted by Borges (2015) for university students, which grounded in Hall’s conceptual framework. Although the scale developed by Briscoe et al. has been widely used in existing research, its emphasis on working adults made it less suitable for this study. As most Chinese students have limited occupational experience, they faced difficulties in responding to workplace-related items during pilot testing. Specifically, workplace-specific terminology and assumptions about prior job experience were adjusted to reflect the education-to-career transition common in China, ensuring that students could meaningfully engage with the items.

3.2.3. Career Exploration Scale

Career exploration measures were adapted from a subscale of the Career Development Inventory (CDI) (Thompson et al. 1981), which was subsequently modified for career exploration assessment by Lokan (1984). Compared to Stumpf et al.’s (1983) Career Exploration Scale, the CDI places greater emphasis on reflective process. Examples include “I actively seek out opportunities to participate in career development activities” and “After activities, I realize I need to improve myself.”

3.3. Data Analysis Technique

The study variables are classified as predictor and outcome variables; however, their underlying structures and relationships are complex. Therefore, the study employed a variance-based structural equation model (VB-SEM), which is particularly appropriate for modeling multiple latent variables and complex causal relationships, and this approach aims to explore the predictive validity of these relationships. In addition, while maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is widely adopted in social science research for model construction, the present study employed Mplus 8.3 with the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) to accommodate the non-normal distribution of some variables and ensure robust estimation in the mediation model.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

Prior to conducting structural equation modeling, the reliability and validity of each latent construct were examined. As shown in

Table 1, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for Perceived Career Advising, Career Orientation, and Career Exploration were 0.939, 0.918, and 0.924, respectively. All exceeding the 0.70 threshold, indicating high internal consistency. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for the three constructs were 0.596, 0.826, and 0.671, meeting the recommended cutoff of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), thus supporting convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was also confirmed, as the square roots of AVE were greater than the inter-construct correlations, indicating adequate separation among constructs. These results demonstrate that the measurement model has good psychometric properties for subsequent structural analyses.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients among the study variables. All three dimensions of perceived career advising (PCA) showed relatively high means (M=3.666, 3.779, and 3.747, respectively), suggesting that students generally perceived their advising experiences positively. Career exploration (M=3.850), self-directed orientation (M=3.870), and value-driven orientation (M=3.894) also exhibited high means, reflecting students’ active engagement in career development.

Correlation analyses revealed that all three advising dimensions were significantly and positively associated with career exploration, self-directed orientation and value-driven orientation. Perceived growth advising (PGA) showed strong correlations with career exploration (r=0.767, p<0.001), self-directed orientation (r=0.681, p <0.001), and value-driven orientation (r=0.688, p<0.001), underscoring the developmental role of career advising in fostering students’ career-related outcomes.

4.3. Path Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

According to Bentler (1990) and Hu & Bentler (1999), the SEM model fits the data well (CMIN/DF =4.371, p<0.001, CFI=0.878, TLI=0.870, RMSEA=0.063). Following the standards set by Kline (2011), the CMIN/DF value should typically fall between 3 and 5, with lower values indicating better model fit. In this study, the CMIN/DF value is 4.371, which falls within the acceptable range.

As shown in

Table 3, structural path estimates were used to examine the direct and mediated effects of PCA on student career outcomes. PPA had significant direct effects on both self-directed (β=0.324,

p<0.001) and value-driven orientation (β=0.193,

p<0.001). In contrast, neither PEA nor PGA showed significant direct effects on either outcome variable.

All three dimensions of advising significantly predicted career exploration. PPA and PGA had strong positive effects on career exploration (β=0.481 and β=0.511, respectively; both p<0.001), while PEA had a significant negative effect (β=-0.192, p<0.01). Career exploration, in turn, exerted strong positive effects on both self-directed (β=0.660, p<0.001) and value-driven orientation (β=0.650, p<0.001). These results suggest that career exploration function as a key mediator between PCA and students’ developmental outcomes.

4.4. Mediation Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

The mediation effects were examined and are summarized in

Table 4, and H5 was supported. Career exploration was found to significantly mediate the associations between different dimensions of perceived career advising (PCA) and the two outcome variables. Among the three advising types, perceived perspective advising (PPA) exhibited a partial mediation effect on both self-directed and value-driven orientation. Specifically, the indirect effect of PPA on self-directed through career exploration was significant (β= 0.317,

p< 0.001), and the direct path was also significant (β=0.324,

p<0.001), indicating a stable and complementary relationship. The proportion of mediation reached approximately 49.5%, suggesting that nearly half of PPA’s total impact on self-directed orientation was explained via career exploration. For value-driven orientation, the mediating role of career exploration was even more prominent, accounting for about 61.9% of the total effect.

In contrast, perceived emotional advising (PEA) demonstrated a full mediation effect on both self-directed and value-driven orientation. While the indirect effects were statistically significant and negative (β=-0.127 and -0.125, respectively; both p<0.01), the direct effects were nonsignificant, implying that career exploration fully mediated the influence of PEA. Perceived growth advising (PGA) also showed a complete mediation through career exploration. Although the direct effects on self-directed and value-driven orientation were not statistically significant, the indirect effects were both significant and positive (β= 0.337 and 0.332, respectively; both p<0.001). Notably, the mediation proportion for value-driven orientation exceeded 100%, which can be interpreted as a suppressor effect. In these cases, career exploration not only mediates but explains and reverses the underlying effects, underscoring its central role in connecting developmental advising to career outcomes.

Table 4.

Mediation test.

| path |

Effect Value |

S.E. |

BC 95% CI |

p |

Proportion of

Mediation Effect |

| Lower 5% |

Upper 5% |

| PPA→CE→SDO |

Indirect effect |

0.317 |

0.033 |

263 |

371 |

0.000 |

49.45% |

| Direct effect |

0.324 |

0.046 |

235 |

399 |

0.000 |

| Total effect |

0.641 |

0.054 |

553 |

730 |

0.000 |

| PEA→CE→SDO |

Indirect effect |

-0.127 |

0.044 |

-0.200 |

-0.054 |

0.004 |

69.02% |

| Direct effect |

-0.057 |

0.054 |

-0.145 |

0.031 |

0.287 |

| Total effect |

-0.184 |

0.072 |

-0.303 |

-0.065 |

0.011 |

| PGA→CE→SDO |

Indirect effect |

0.337 |

0.046 |

261 |

0.413 |

0.000 |

125.28% |

| Direct effect |

-0.068 |

0.06 |

-0.166 |

0.031 |

0.258 |

| Total effect |

0.269 |

0.075 |

0.145 |

0.393 |

0.000 |

| PPA→CE→VDO |

Indirect effect |

0.313 |

0.033 |

0.258 |

0.368 |

0.000 |

61.86% |

| Direct effect |

0.193 |

0.05 |

0.112 |

0.275 |

0.000 |

| Total effect |

0.506 |

0.054 |

0.418 |

0.594 |

0.000 |

| PEA→CE→VDO |

Indirect effect |

-0.125 |

0.044 |

-0.197 |

-0.053 |

0.004 |

113.64% |

| Direct effect |

0.015 |

0.060 |

-0.085 |

0.114 |

0.808 |

| Total effect |

-0.110 |

0.075 |

-0.233 |

0.013 |

0.140 |

| PGA→CE→VDO |

Indirect effect |

0.332 |

0.045 |

0.257 |

0.407 |

0.000 |

107.10% |

| Direct effect |

-0.022 |

0.065 |

-0.130 |

0.085 |

0.733 |

| Total effect |

0.310 |

0.077 |

0.183 |

0.437 |

0.000 |

Taken together, these findings indicate that career exploration functions as a critical mechanism linking perceived career advising to students’ career orientation. While PPA promotes both self-directed and value-driven motivation through a dual pathway, PEA and PGA rely more heavily on career exploration to exert their influence, pointing to the varied psychological routes through which advising shapes undergraduate career development.

5. Discussions

5.1. Only PPA Directly and Positively Influences Career Orientation

The results partially support H1 and H2. Among the three types of advising, only PPA demonstrated significant and stable direct effects on both outcome variables. This finding reinforces the idea that structured, information-based advising plays a central role in shaping students’ capacity for autonomous decision-making and purpose-driven goal setting. It echoes earlier work suggesting that goal clarity and decision-related cognitive inputs are core antecedents of self-determined career planning (Brown et al., 2003; Lent & Brown, 2013). Furthermore, this suggests that perspective advising may be fundamental to resolving students’ difficulties in career orientation, as it aligns more directly with their immediate developmental needs.

In contrast, PEA and PGA showed no significant direct associations with either outcome variable. One explanation could be that emotionally affirming or aspirational conversations, though valuable for trust-building, may fall short of mobilizing students’ planning capacities if they are not supported by actionable strategies or tangible goals (Sampson et al., 2004). These results challenge the assumption that all forms of support foster career development equally (Gati & Asulin-Peretz, 2011). While previous literature has highlighted the motivational benefits of affective support (Bagci, 2018), our findings suggest that if not anchored in instrumental content, such advising may not yield measurable effects on students’ career direction. As Dey (2014), former Vice Provost for Student Affairs at Stanford University, emphasized, new initiatives must be incorporated into existing career services to address evolving student needs.

5.2. PPA and PGA Encourage Career Exploration While PEA Hinder It

H3a-c are partially confirmed by the findings, which indicate that PPA and PGA significantly predict students’ engagement in career exploration. This suggests that when students receive advising that offers direction or encourages long-term development, they are more likely to initiate exploration efforts, such as seeking information, reflecting on alternatives, or engaging in internships. This pattern aligns with previous studies on exploratory behavior (Super, 1990; Hirschi, 2020). Developmental advising that provides both structure and encouragement appears particularly effective in facilitating students’ transition from passive contemplation to active planning.

However, PEA exhibited an unexpected negative effect on career exploration. This finding contradicts prior assumptions that emotional support necessarily strengthens students’ engagement. Similar patterns have been observed in counseling research, where emotional reassurance without cognitive structuring may foster dependency and decreased self-efficacy (Lapan et al., 2001). Moreover, students with high uncertainty or low confidence may interpret emotional support as a signal of external control rather than internal readiness, thereby hindering proactive exploration (Ryan & Deci, 2000). In short, without sufficient instrumental orientation, perceived emotional advising cannot serve as an effective foundation for exploration.

5.3. Career Exploration Serves as a Core Mediator

Consistent with Hypotheses H4 and H5, career exploration significantly predicted both self-directed and value-driven orientation. More importantly, it mediated the effects of all three advising types on career orientation. These findings highlight that affective and growth-oriented conversations can still be effective when channeled through exploratory engagement (Koen et al., 2012). In particular, the estimated mediation proportion of PGA exceeding 100% suggests a suppressor effect. Suppressor effects of this nature have been reported in research on career identity transitions (Briscoe et al., 2012), and suggest that career exploration functions not merely as a pathway but as a reframing mechanism.

In contrast, PPA demonstrated a pattern of partial mediation. This suggests that PPA has both a direct cognitive-structural effect and an indirect developmental effect via career exploration. The complementary mediation pattern aligns with findings from career construction theory (Savickas, 2005), which emphasizes that both direct guidance and exploratory experience jointly contribute to identity consolidation. These findings underscore the importance of career advising frameworks that not only deliver structured input but also actively cultivate students’ exploratory agency.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study examined how different forms of perceived career advising influence undergraduates’ career orientation, and how these effects are mediated by career exploration. By triggering students’ exploratory engagement, perceived career advising plays an initiating role in shaping career orientation, functioning as a developmental scaffold. Career exploration, in turn, functions as a central mechanism that connects institutional guidance to students’ long-term developmental goals.

6.1. Strengthening Structured PA and Activating the Functions of EA and GA

The results underscore that not all forms of advising contribute equally to students’ career development. Among the three types examined, perspective advising plays a foundational role. Therefore, any effective career advising system must first ensure the stable implementation of structured, information-rich perspective advising. To operationalize this, Faculty and staff of UAS can be trained to deliver targeted advising modules that include goal clarification tools, decision-mapping exercises, and labor market literacy sessions.

Once this foundation is in place, the potential of emotional and growth advising can be more fully activated. Emotional advising can be redesigned to function not only as reassurance, but as a catalyst for exploration when paired with reflective questioning. For example, advising sessions can include emotional check-ins followed by values clarification or narrative career construction tasks, which help students transform affective states into motivational energy. Similarly, growth advising should be scaffolded through structured goal-setting templates, personal development plans, and milestone tracking systems. Advisors can assist students in identifying long-term aspirations and breaking them down into actionable steps (Yang et al. 2024). In doing so, universities can shift from fragmented advising encounters to an integrated, student-centered guidance ecology that promotes clarity, confidence, and commitment.

6.2. Promoting Career Exploration as a Developmental Process

The findings confirm that career exploration is a key developmental mechanism through which career advising translates into career orientation. Yet, exploration does not occur spontaneously. To harness this potential, institutions must build an integrated system in which advising catalyzes exploration, and exploration deepens advising impact.

At the institutional level, exploration should be cultivated as a staged and supported process. Universities can develop tiered exploration tracks aligned with students’ academic progression. For instance, early-stage advising may focus on broad exposure, such as industry talks, career simulations, or alumni panels. Whereas mid- to late-stage advising can incorporate applied learning opportunities such as guided internships, job shadowing, or service-learning projects. These should be intentionally sequenced with pre-exploration advising sessions and post-exploration reflection modules to ensure students make meaning from experience and update their goals accordingly (Kang, 2023).

Moreover, universities could embed career exploration into general education curricula, allowing students to investigate real-world problems, conduct informational interviews, and co-construct evolving career identities with peers and mentors (Venson et al. 2016). Such modules not only bridge advising and curriculum, but also reposition exploration as a developmental competency.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

While offering robust theoretical and empirical contributions, this study is circumscribed by its focus on a Chinese university, which may limit the generalizability of the findings beyond this specific educational and cultural context, and by its cross-sectional design. Future research should adopt longitudinal or mixed-method designs to better capture how advising and exploration interact across different academic years. Lastly, while this study focuses on advising and exploration as key variables, other influences such as personality traits, peer norms, or academic major may also play a role in shaping career orientation. Future research could integrate these factors into more complex models, or explore how different student groups experience and benefit from various advising strategies.

Author Contributions

T.G. performed the data analysis and wrote the original draft. G.X. provided the funding acquisition and supervision. T.H. and J.S. reviewed and edited the draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No.72374072), the Project of the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League of China (Grant No. KT2024407587) and the Project of Career Development Center, East China Normal University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University Committee on Human Research Protection of East China Normal University (Approval Code: No. HR 828-2024, Approval Date: 04 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bagci, S. C. (2018). Does everyone benefit equally from self-efficacy beliefs? The moderating role of perceived social support on motivation. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(2), 204-219.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986(23-28), 2.

- Bargmann, C., Thiele, L., & Kauffeld, S. (2022). Motivation matters: Predicting students’ career decidedness and intention to drop out after the first year in higher education. Higher Education, 1-17.

- Borges, L. F. L., De Andrade, A. L., de Oliveira, M. Z., & Guerra, V. M. (2015). Expanding and adapting the protean career management scale for university students (PCMS-U). The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18, E103.

- Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., & DeMuth, R. L. F. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers: An empirical exploration. Journal of vocational behavior, 69(1), 30-47.

- Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., & ` DeMuth, R. L. (2012). Protean and boundaryless careers in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 4-18.

- Cheung, R., & Arnold, J. (2014). The impact of career exploration on career development among Hong Kong Chinese university students. Journal of College Student Development, 55(7), 732-748.

- Crookston, B. B. (1972). A developmental view of academic advising as teaching. Journal of College Student Personnel.

- Dey F, Cruz Vergara C Y. Evolution of career services in higher education[J]. New directions for student services, 2014,2014(148): 5-18.

- Dozier, V. C., Sampson Jr, J. P., Lenz, J. G., Peterson, G. W., & Reardon, R. C. (2015). The impact of the Self-Directed Search Form R Internet version on counselor-free career exploration. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(2), 210-224.

- Elgeddawy, M., Abouraia, M., & Magd, H. (2024). Academic and Career Advising: Factors of Success and Opportunities for Institutional Improvement. International Society for Technology, Education, and Science.

- Figueiredo, H., Biscaia, R., Rocha, V., & Teixeira, P. (2017). Should we start worrying? Mass higher education, skill demand and the increasingly complex landscape of young graduates’ employment. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1401-1420.

- Flum, H., & Blustein, D. L. (2000). Reinvigorating the study of vocational exploration: A framework for research. Journal of vocational Behavior, 56(3), 380-404.

- Gati, I., & Asher, I. (2001). Prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice: From decision theory to career counseling practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 50(2), 140-157.

- Gati, I., & Asulin-Peretz, L. (2011). Internet-based self-help career assessments and interventions: Challenges and implications for evidence-based career counseling. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(3), 259-273.

- Guo, L., & Xiao, F. (2024). Digital economy, aging of the labour force, and employment transformation of migrant workers: Evidence from China. Economic Analysis and Policy, 84, 787-807.

- Hall D T, Yip J, Doiron K. Protean careers at work: Self-direction and values orientation in psychological success[J]. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2018, 5: 129-156.

- Hall, D. T. (1996). Protean careers of the 21st century. Academy of management perspectives, 10(4), 8-16.

- Hall, D. T. (2004). The protean career: A quarter-century journey. Journal of vocational behavior, 65(1), 1-13.

- Hirschi, A. (2020). Whole-life career management: A counseling intervention framework. The career development quarterly, 68(1), 2-17.

- Hirschi, A., & Koen, J. (2021). Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103505.

- Hirschi, A., & Pang, D. (2023). Pursuing money and power, prosocial contributions, or personal growth: measurement and nomological net of different career strivings. Journal of Career Development, 50(6), 1206-1228.

- Hughey, K. F., Nelson, D., Damminger, J. K., & McCalla-Wriggins, B. (2012). The handbook of career advising. John Wiley & Sons.

- Jing, W., & Welch, A. (2018). Academic drift in China’s universities of applied technology. International Higher Education, 94, 30-31.

- Jordaan, J.P. (1963), “Exploratory behavior: the formation of self and occupational concepts”, in Super, D.E. (Ed.), Career Development: Self Concept Theory, College Entrance Examination Board, New York, NY, pp. 42-78.

- Kang, D. (2023). Prioritizing Career Preparation: Learning Achievements and Extracurricular Activities of Undergraduate Students for Future Success. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 611. [CrossRef]

- Keshf, Z., & Khanum, S. (2021). Career Guidance and Counseling Needs in a Developing Country’s Context: A Qualitative Study. SAGE Open, 11(3).

- Kleine, A. K., Schmitt, A., & Wisse, B. (2021). Students’ career exploration: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103645.

- Koen, J., Klehe, U. C., & Van Vianen, A. E. (2012). Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 395-408.

- Laff, N. S. (1994). Reconsidering the developmental view of advising: Have we come a long way?. nacada Journal, 14(2), 46-49.

- Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., & Petroski, G. F. (2001). Helping seventh graders be safe and successful: A statewide study of the impact of comprehensive guidance and counseling programs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(3), 320-330.

- Lee, J. K., & Goh, M. (2003). Career counseling centers in higher education: A study of cross-cultural applications from the United States to Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 4, 84-96.

- Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of counseling psychology, 60(4), 557.

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of counseling psychology, 47(1), 36.

- Li, Q., Baciu, G., Cao, J., Huang, X., Li, R. C., Ng, P. H.,... & Wang, Y. (2022, June). Kcube: A knowledge graph university curriculum framework for student advising and career planning. In International Conference on Blended Learning (pp. 358-369). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Lokan, J. (1984). Manual of the Career Development Inventory—Australian Edition. Melbourne: ACER.

- Luzzo, D. A., & Day, M. A. (1999). Effects of Strong Interest Inventory feedback on career decision-making self-efficacy and social cognitive career beliefs. Journal of Career Assessment, 7(1), 1-17.

- Lynch, J., & Lungrin, T. (2018). Integrating academic and career advising toward student success. New Directions for Higher Education, 2018(184), 69-79.

- Muceldili, B., Artar, M., & Erdil, O. (2021). Determining the moderating role of career guidance in the relationship between social isolation and job search self-efficacy: A study on university students. Business and Economics Research Journal, 12(4), 843-854.

- Mujib, M., & Purusa, N. A. (2022). Shaping The Protean Career Orientation of Undergraduate Students: Does Academic Advisor Plays Role?. Relevance: Journal of Management and Business, 5(2), 136-159.

- Nießen, D., Wicht, A., Schoon, I., & Lechner, C. M. (2022). “You can’t always get what you want”: Prevalence, magnitude, and predictors of the aspiration–attainment gap after the school-to-work transition. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 71, 102091.

- NIU X C, ZHENG Y J. (2018). College Students’ Career Directions: Examining the Process Based on Longitudinal Survey Data. Modern University Education, 05:58-71+113.

- OECD (2025), The State of Global Teenage Career Preparation, OECD Publishing, Paris, . [CrossRef]

- Peng, H., Shih, Y., & Chang, L. (2020). The impact of a career group counseling mix model on satisfaction of low-achieving college students-specialty-oriented career exploration group counseling. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 12(2), 1.

- Perdrix, S., Stauffer, S., Masdonati, J., Massoudi, K., & Rossier, J. (2012). Effectiveness of career counseling: A one-year follow-up. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 565-578.

- Pesch, K. M., Larson, L. M., & Seipel, M. T. (2018). Career certainty and major satisfaction: The roles of information-seeking and occupational knowledge. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(4), 583-598.

- Prescod, D. J., Gilfillan, B., Belser, C. T., Orndorff, R., & Ishler, M. (2019). Career decision-making for undergraduates enrolled in career planning courses. College Quarterly, 22(2).

- Quinlan, K. M., & Corbin, J. (2023). How and why do students’ career interests change during higher education?. Studies in Higher Education, 48(6), 771-783.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68.

- Rivera, H., & Li, J. T. (2020, April). Potential factors to enhance students’ STEM college learning and career orientation. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 5, p. 25). Frontiers Media SA.

- Sampson, J. P., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. G. (2004). Career counseling and services: A cognitive information processing approach. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Brooks/Cole.

- Sargent, L. D., & Domberger, S. R. (2007). Exploring the development of a protean career orientation: values and image violations. Career development international, 12(6), 545-564.

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction.

- Schlesinger, J., O’Shea, C., & Blesso, J. (2021). Undergraduate student career development and career center services: Faculty perspectives. The Career development quarterly, 69(2), 145-157.

- Schlosser, L. Z., Lyons, H. Z., Talleyrand, R. M., Kim, B. S., & Johnson, W. B. (2011). Advisor-advisee relationships in graduate training programs. Journal of Career Development, 38(1), 3-18.

- Staiculescu, C., & Dobrea, R. C. (2017). Impact of the career counseling services on employability. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

- Stipanovic, N., Stringfield, S., & Witherell, E. (2017). The influence of a career pathways model and career counseling on students’ career and academic self-efficacy. Peabody journal of education, 92(2), 209-221.

- Storme, M., & Celik, P. (2018). Career exploration and career decision-making difficulties: The moderating role of creative self-efficacy. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(3), 445-456.

- Streufert, B. (2019). Career advising: A call for universal integration and curriculum. Academic Advising Today, 42(2).

- Stumpf, S. A., Colarelli, S. M., & Hartman, K. (1983). Development of the career exploration survey (CES). Journal of vocational behavior, 22(2), 191-226.

- Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of vocational behavior, 16(3), 282-298.

- Suryadi, B., Sawitri, D. R., Hayat, B., & Putra, M. (2020). The Influence of Adolescent-Parent Career Congruence and Counselor Roles in Vocational Guidance on the Career Orientation of Students. International Journal of Instruction, 13(2), 45-60.

- Thompson, A. S., Lindeman, R. H., Super, D. E., Jordaan, J. P., & Myers, R. A. (1981). Career development inventory (Vol. 1). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Trow, M. (2007). Reflections on the transition from elite to mass to universal access: Forms and phases of higher education in modern societies since WWII. In International handbook of higher education (pp. 243-280). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Troxel, W. G., Bridgen, S., Hutt, C., & Sullivan-Vance, K. A. (2021). Transformations in academic advising as a profession. New Directions for Higher Education, 2021(195-196), 23-33.

- Van Der Stuyf, R. R. (2002). Scaffolding as a teaching strategy. Adolescent learning and development, 52(3), 5-18.

- Venson, E., Figueiredo, R., Silva, W., & Ribeiro, L. C. (2016, October). Academy-industry collaboration and the effects of the involvement of undergraduate students in real world activities. In 2016 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 1-8). IEEE.

- Wei, C., Akos, P., Jiang, X., & Harbour, S. (2016). A Comparison of University Career Services in China and the United States. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 6(1).

- West, J. (2000). Higher education and employment: opportunities and limitations in the formation of skills in a mass higher education system. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 52(4), 573-588.

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100.

- Yang, Y., Ye, X., Ma, X., & Wu, H. (2024). How does developmental advising impact college students? Findings from medical students in China. Studies in Higher Education, 49(12), 2844-2860.

- Zammitti, A., Russo, A., Ginevra, M. C., & Magnano, P. (2023). “Imagine Your Career after the COVID-19 Pandemic”: An Online Group Career Counseling Training for University Students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y., Xu, C., & Xu, Z. (2023). Protean career orientation and proactive career behaviors during school-to-work transition: Mechanism exploration and coaching intervention. Journal of Career Development, 50(3), 547-562.

Table 1.

Reliability and Validity Testing of Measurement Instruments.

Table 1.

Reliability and Validity Testing of Measurement Instruments.

| Variable |

Convergent Validity |

Discriminant Validity |

| Cronbach’s Alpha |

AVE |

CO |

CE |

PCA |

| Career Orientation |

0.918 |

0.826 |

0.909 |

|

|

| Career Exploration |

0.924 |

0.671 |

0.479 |

0.819 |

|

| Perceived Career Advising |

0.939 |

0.596 |

0.735 |

0.521 |

0.772 |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficients among Variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficients among Variables.

| |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Perceived perspective advising |

3.666 |

0. 879 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceived emotional advising |

3.779 |

0.831 |

0.913***

|

— |

|

|

|

|

| Perceived growth advising |

3.747 |

0.829 |

0.915***

|

0.955 |

— |

|

|

|

| Career exploration |

3.797 |

0.850 |

0.773***

|

0.735***

|

0.767***

|

— |

|

|

| Self-directed orientation |

3.870 |

0.904 |

0.720***

|

0.659***

|

0.681***

|

0.816***

|

— |

|

| Value-driven orientation |

3.894 |

0.872 |

0.689***

|

0.648***

|

0.688***

|

0.793***

|

0.921***

|

— |

Table 3.

Path coefficients analysis.

Table 3.

Path coefficients analysis.

| path |

Estimate(B) |

S.E. |

C.R. |

p |

β |

Result |

| PPA→SDO |

0.346 |

0.046 |

7.090 |

0.000 |

0.324 |

H1a supported |

| PEA→SDO |

-0.057 |

0.054 |

-1.064 |

0.287 |

-0.057 |

H1b not supported |

| PGA→SDO |

-0.069 |

0.060 |

-1.130 |

0.258 |

-0.068 |

H1c not supported |

| PPA→VDO |

0.208 |

0.05 |

3.886 |

0.000 |

0.193 |

H2a supported |

| PEA→VDO |

0.015 |

0.06 |

0.243 |

0.808 |

0.015 |

H2b not supported |

| PGA→VDO |

-0.023 |

0.065 |

-0.341 |

0.733 |

-0.022 |

H2c not supported |

| PPA→CE |

0.518 |

0.047 |

10.133 |

0.000 |

0.481 |

H4a supported |

| PEA→CE |

-0.193 |

0.067 |

-2.878 |

0.004 |

-0.192 |

H4c supported |

| PGA→CE |

0.525 |

0.068 |

7.563 |

0.000 |

0.511 |

H4c supported |

| CE→SDO |

0.653 |

0.025 |

26.820 |

0.000 |

0.660 |

H4a supported |

| CE→VDO |

0.650 |

0.026 |

25.462 |

0.000 |

0.650 |

H4b supported |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).