1. From Support to Adaptation: Examining Career Exploration as a Mediator Between Social Support and Parental Behaviors with Career Adaptability

Career adaptability—the capacity to navigate and respond effectively to evolving career demands—has emerged as a critical factor in contemporary career development (Rudolph et al., 2017; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Research increasingly highlights the role of contextual influences, particularly social support and parental behaviors, in shaping this adaptability (Guan et al., 2016; Hirschi, 2009). These influences not only provide emotional, informational, and instrumental resources but also foster engagement in career exploration, a key process through which individuals clarify goals, assess opportunities, and develop adaptive capacities (Kracke, 2002).

Career exploration serves as a central mechanism by which social and parental support may be translated into career adaptability. Through this process, individuals actively seek and process information about themselves and the labor market, which aids in forming adaptive career trajectories (Zikic & Klehe, 2006). Supportive social environments and proactive parental involvement can catalyze this exploration, providing both the confidence and the resources needed to make informed career decisions (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009).

Empirical evidence supports a positive relationship between social support, career exploration, and career adaptability (Hirschi et al., 2011; Nota et al., 2007). Emotional encouragement enhances motivation, informational guidance supports decision-making, and instrumental aid facilitates access to career-related opportunities (Keller & Whiston, 2008; Lent et al., 2000). Similarly, parental behaviors—particularly those involving encouragement, open communication, and modeling adaptive traits—have been found to significantly impact youths’ career exploration and adaptability (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009).

Despite these established associations, the mediating role of career exploration remains underexplored. This study aims to examine how career exploration functions as a conduit through which social support and parental behaviors influence career adaptability. Understanding these pathways can inform the design of more targeted interventions to support career development, especially during critical transitional periods such as adolescence and early adulthood.

2. Background

Theoretical Framework

This study draws upon two complementary career development theories—Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) and Career Construction Theory (CCT)—to examine the relationship between social support, parental behaviors, and career adaptability, with career exploration serving as a mediating mechanism.

SCCT posits that career development is shaped by self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and personal goals (Lent & Brown, 2019). These constructs are influenced by prior performance, social persuasion, emotional states, and vicarious learning. Within this framework, social support and parental behaviors can strengthen self-efficacy and influence career-related decision-making (Wang et al., 2022). SCCT emphasizes how individuals’ beliefs about their abilities impact their career interests, exploration, and adaptability.

CCT, on the other hand, conceptualizes career development as an ongoing process of personal construction. It highlights the role of vocational personality, adaptability resources—concern, control, curiosity, and confidence—and life themes in navigating career transitions (Savickas, 2020). Adaptability, in this context, is a core competency that enables individuals to respond effectively to evolving career demands and uncertainties (Rudolph et al., 2017).

Career exploration is positioned within this framework as a key mediating process. It translates the influence of social support and parental behaviors into concrete career adaptability outcomes. Through exploration, individuals actively engage with career-related information, test their interests, and develop competencies that enhance their adaptability (liu et al., 2024; Yue & Jing, 2025). Thus, career exploration acts as a conduit through which external influences are internalized and transformed into adaptive career behaviors.

Together, these theoretical perspectives provide an integrated understanding of how psychological (self-efficacy, adaptability) and social (support, parenting) factors interact. For example, Hou and colleagues (Hou et al., 2019) demonstrated that career decision-making self-efficacy mediates the effect of social support on career adaptability in a longitudinal study. This framework supports the hypothesis that social support and parental behaviors exert indirect effects on career adaptability through the mediating role of career exploration. This aligns with Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2019), who found that both self-efficacy and parental support mediated the link between personality traits and career exploration among adolescents. By incorporating both cognitive and constructivist perspectives, the model offers a more nuanced explanation of the processes underlying career development.

Social Support in Career Development

Social support is a critical determinant of career development, serving both as a buffer against career-related stress and as a catalyst for exploration and adaptability (Akkermans et al., 2024). It encompasses emotional, informational, and instrumental dimensions, each contributing uniquely to individuals’ ability to navigate evolving career pathways.

Emotional support—characterized by empathy, encouragement, and reassurance—enhances psychological resilience during career decision-making. Informational support, such as guidance, advice, and access to relevant knowledge, equips individuals with the cognitive tools necessary for effective career planning. Instrumental support, including tangible resources like financial aid or access to employment opportunities, provides the structural means to pursue and realize career goals (Putri, 2024).

These forms of support are typically embedded within social networks composed of peers, mentors, and professional communities (Beals et al., 2021). Peers offer validation and mutual understanding, mentors serve as role models and sources of strategic insight, while professional networks expose individuals to diverse career options and facilitate opportunity recognition.

Empirical research consistently links social support with favorable career outcomes, including higher job satisfaction, increased self-efficacy, and greater career adaptability (Al-Jubari et al., 2021; Karatepe & Olugbade, 2017; Xia et al., 2020). Career mentoring, in particular, has been shown to foster exploratory behaviors and adaptive responses to labor market uncertainty—mechanisms central to the development of career adaptability (Kanten et al., 2017).

However, the impact of social support is not uniform across contexts. Cultural norms shape how support is perceived and utilized; collectivist cultures may prioritize familial and communal input, whereas individualistic cultures may emphasize autonomy. Similarly, socioeconomic status can mediate access to quality support networks, potentially reinforcing disparities in career opportunities and outcomes (Koch et al., 2024).

In the context of this study, social support is examined not as a direct determinant of career adaptability, but as a foundational resource that influences exploratory behaviors. Understanding how individuals translate support into action—particularly through career exploration—offers a more nuanced view of how adaptability is cultivated. As such, career exploration emerges as a potential mediating mechanism, linking the presence of support to adaptive career development in the face of complex and dynamic labor environments.

Parental Behaviors and Career Outcomes

Parental behaviors are widely recognized as critical influences on adolescents’ career development and long-term career outcomes. Key behaviors such as involvement, encouragement, and autonomy support play distinct yet interrelated roles in fostering career exploration and adaptability (Zhang et al., 2019).

Parental involvement refers to the active engagement of parents in their children’s career-related activities (Pesch et al., 2016), including discussions about future plans, participation in career events, and the provision of relevant resources. Such involvement has been positively linked to increased intrinsic motivation, deeper engagement in vocational exploration, and greater clarity in career goals. This form of support helps adolescents develop confidence and direction in navigating the complexities of career decision-making.

Parental encouragement, often expressed through verbal affirmations and expressions of belief in a child’s capabilities, serves to reinforce self-efficacy and resilience. Research indicates that such encouragement contributes to higher levels of career adaptability by promoting optimism and perseverance—traits essential for managing career transitions and uncertainties (Söner & Gültekin, 2024; Zeng et al., 2022).

Autonomy support, or the extent to which parents allow and encourage their children to make independent career-related decisions, is another crucial dimension (Wei et al., 2022). Rather than imposing specific expectations, autonomy-supportive parents foster self-determination, critical thinking, and personal responsibility. This approach has been shown to enhance both psychological well-being and career persistence, particularly in fields requiring long-term commitment, such as STEM disciplines. Conversely, controlling or overprotective parenting may hinder the development of autonomy, increasing the risk of career indecision and maladaptive career behaviors.

Importantly, research highlights the need for a balanced approach (Guan et al., 2018; Moavero et al., 2025). While low parental engagement can lead to reduced career motivation and adaptability, excessive involvement or pressure can be equally detrimental, contributing to stress, indecisiveness, and diminished career satisfaction. Career adaptability may serve as a mediating mechanism in these dynamics, shaping how parental behaviors translate into long-term career trajectories (Li et al., 2024).

In summary, supportive parental behaviors—characterized by appropriate involvement, encouragement, and autonomy granting—are instrumental in promoting adaptive career development. Striking the right balance between support and independence is essential to fostering resilience, self-efficacy, and successful career outcomes in youth.

Career Exploration and Adaptability

Career exploration is a dynamic, self-regulatory process through which individuals acquire knowledge about themselves and the world of work, thereby facilitating informed career decision-making (Rezaiee & Kareshki, 2024). It encompasses three interrelated dimensions: self-assessment, environmental scanning, and goal formulation. Self-assessment involves evaluating one’s interests, values, and competencies, while environmental exploration focuses on examining occupational opportunities, labor market trends, and industry demands (Ran et al., 2023). These processes converge in the setting of realistic and strategically aligned career goals.

The relevance of career exploration lies in its capacity to foster career adaptability—a psychosocial construct denoting the readiness and resources to manage occupational tasks, transitions, and uncertainties (Hirschi et al., 2015; Savickas, 2020). As individuals engage in exploration, they refine their vocational identity and enhance their ability to navigate the evolving demands of the workforce. By integrating internal self-knowledge with external realities, exploration serves as a foundation for adaptive career behaviors.

In the context of social support and parental influence, career exploration may function as a critical mediator. Supportive social environments and constructive parental behaviors can promote exploratory behaviors, which in turn facilitate the development of adaptability. This mediating role suggests that exploration not only reflects individual agency but also channels external resources into adaptive career capacities.

Nevertheless, the process must be intentional and well-guided. Unfocused or excessive exploration may lead to decision-making difficulties, goal diffusion, or reduced commitment. Therefore, the effectiveness of exploration in fostering adaptability is contingent on its purposefulness and alignment with clear developmental goals.

In sum, career exploration is not merely a precursor to career choice but a pivotal mechanism through which individuals convert social and familial support into adaptive career capabilities. Recognizing its mediating function provides valuable insight into how external influences shape internal adaptability through structured exploratory engagement.

Hypothesized Model

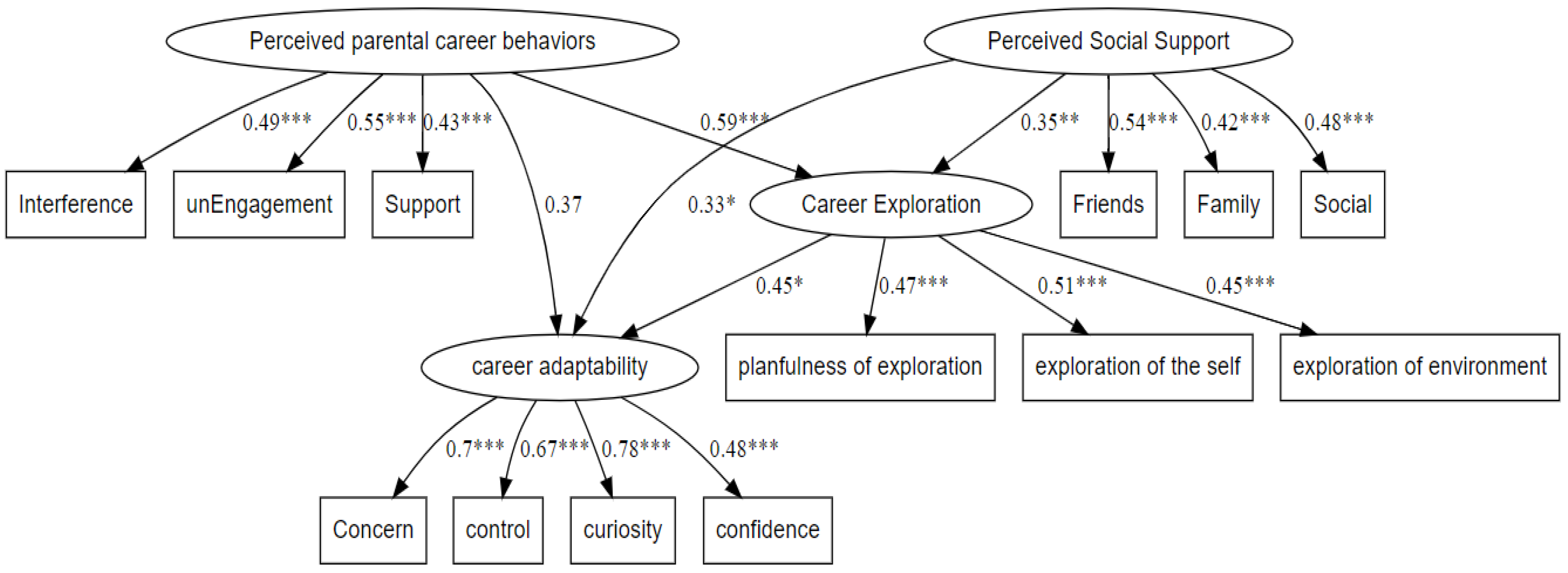

This study proposes a conceptual framework that examines the mediating role of career exploration in the relationships between social support, parental behaviors, and career adaptability. Grounded in career development theory, the model posits that social support and parental behaviors function as antecedent variables that indirectly influence career adaptability through their impact on career exploration.

Hypothesis 1: Social support is positively associated with career exploration. Emotional, informational, and instrumental support from an individual’s social network is expected to facilitate engagement in career-related exploratory activities.

Hypothesis 2: Parental behaviors—specifically involvement, encouragement, and autonomy support—are positively related to career exploration. These behaviors are theorized to create an environment that motivates and empowers individuals to actively investigate career possibilities.

Hypothesis 3: Career exploration mediates the relationship between social support and career adaptability. It is proposed that social support enhances career adaptability indirectly by promoting the self-reflective and information-seeking processes characteristic of exploration.

Hypothesis 4: Career exploration mediates the relationship between parental behaviors and career adaptability. Supportive parental involvement is expected to foster adaptability by encouraging individuals to engage in meaningful career exploration, thereby developing the competencies needed to navigate career transitions.

This model emphasizes the pivotal role of career exploration as a mechanism through which external supports—both general (social) and specific (parental)—are translated into career adaptability. Unlike direct-effect models that assume a straightforward influence of support on adaptability, the proposed model highlights the importance of intervening processes in career development.

In sum, the hypothesized model provides a theoretically grounded and empirically testable framework that contributes to understanding how social and familial support systems shape career adaptability through the mediating influence of career exploration.

3. Method

Participants

This study involved middle school students (Grades 7–9) from Tehran County, Iran, during the 2024–2025 academic year. The target population comprised students enrolled in public middle schools within District 5 of Tehran’s educational system.

A multistage cluster random sampling method was employed. First, five schools were randomly selected from District 5. Within each selected school, classes were chosen at random, and all students in those classes were invited to participate. The final sample included 643 students, with the sample size determined using G*Power software to ensure sufficient statistical power for SEM. Data were collected in person during school hours, following informed consent procedures.

Measures

Career adaptability was assessed using the 12-item short form of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale developed by Maggiori and colleagues (Maggiori et al., 2017). The scale measures four dimensions: concern (items 1–3), control (4–6), curiosity (7–9), and confidence (10–12). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not strong) to 5 (very strong). In Karimi and colleagues’ study (Karimi et al., 2021), internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) were acceptable, ranging from .70 to .83 across subscales, with an overall reliability of .78.

- 2.

Career Exploration Questionnaire (CEQ)

Career exploration behaviors were measured using the Career Exploration Questionnaire (CEQ) originally developed by Kracke (Kracke, 1997). This instrument consists of six items evaluating self- and environment-oriented exploration activities (e.g., “I try to find out which occupations best fit my strengths and weaknesses.”). Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). The scale demonstrated reliability coefficients of .79 for girls and .76 for boys.

- 3.

Perceived Parental Career-Related Behaviors (PCB)

Parental behaviors were measured using the Perceived Parental Career-Related Behavior Scale by Dietrich and Kracke (2009). This 15-item instrument includes three subscales: support (items 1–5), interference (6–10), and lack of engagement (11–15). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). The reliability of each scale was confirmed through Cronbach’s alpha, showing satisfactory internal consistency: for girls, support scored .93, interference .72, and lack of engagement .68; for boys, the respective values were .84, .78, and .75 (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009).

- 4.

Perceived Social Support

Perceived social support (PSS) was measured using a validated subscale of a broader adolescent well-being inventory. This subscale assesses the extent to which students perceive emotional and instrumental support from significant others (e.g., family, friends, and teachers). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The internal consistency of the MSPSS was confirmed using Cronbach’s alpha (Total = .88; Subscales: .91, .87, .85). Test-retest reliability over 2–3 months showed adequate stability (Total = .85; Subscales: .72, .85, .75) (Zimet et al., 1988).

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 and R Version 4.3.2. Analyses in R utilized the psych, lavaan, semPlot, and lavaanPlot packages to conduct SEM and associated visualizations.

Initial data screening included an examination for multivariate outliers. After removing 21 outlier cases, the final analytic sample comprised 643 valid observations. Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to explore associations among the primary study variables. The correlation matrix revealed significant positive relationships among career adaptability, career exploration, perceived social support, and career-specific parental behaviors, with the exception of the non-significant association between perceived social support and career-specific parental behaviors.

To test the hypothesized mediation model, SEM was employed to evaluate whether career exploration mediated the effects of two predictor variables—perceived social support and career-specific parental behaviors—on the outcome variable, career adaptability. Model fit was assessed using multiple indices, as recommended (Kline, 2023).

5. Discussion

This study examined the mediating role of career exploration in the relationship between two contextual factors—perceived social support and career-specific parental behaviors—and the outcome variable of career adaptability. Findings indicate that career exploration serves as a significant partial mediator, highlighting its importance in translating supportive environments into adaptive career functioning.

Both parental behaviors and perceived social support demonstrated strong direct effects on career adaptability (β = .371 and β = .327, respectively). In addition, these variables indirectly influenced career adaptability through their impact on career exploration, with statistically significant indirect effects for parental behaviors (β = .349, p < .05) and social support (β = .099, p < .05). These results underscore the role of exploratory behavior as a mechanism through which social contexts shape career development. This is consistent with recent research showing that environmental factors, including parental and social support, influence career adaptability via self-regulatory processes such as career exploration (Guan et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2023; Pham et al., 2024).

Interestingly, no significant correlation was found between perceived social support and parental behaviors (r = −.02, p > .05), suggesting that these two sources of support operate independently in influencing career trajectories during emerging adulthood.

These findings align with career construction theory (Savickas, 2020), which posits that career adaptability develops through the interplay between individual psychological resources and contextual influences. Within this framework, career exploration represents a key self-regulatory process through which individuals respond to and engage with their environment to build adaptability.

Notably, the stronger path from parental behaviors to career exploration (β = .59) compared to that from social support (β = .348) indicates that parents have a more direct and targeted impact on career-related behaviors (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009; Liang et al., 2023). This may reflect the dual role of parental influence, which provides not only emotional support but also practical guidance, encouragement, and information—all of which are instrumental in fostering career exploration.

While perceived social support also contributes positively to exploration and adaptability, its influence is more diffuse (Ataç et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2021; Öztemel & Yıldız-Akyol, 2021; Xu et al., 2024). Support from peers, extended family, and significant others may bolster general well-being and confidence (Acoba, 2024) but lacks the specificity of parental behaviors in promoting career-oriented action. Nevertheless, its significant indirect effect affirms the multifaceted nature of support systems in career development.

Importantly, the sustained direct effects of both social support and parental behaviors on career adaptability—despite the mediating role of exploration—support a dual-pathway model. This model suggests that adaptability is influenced both directly by contextual support and indirectly through exploratory behavior, reinforcing the notion that career adaptability is not purely self-driven but co-constructed through individual and environmental factors (Hlad′o et al., 2020; Leung & Zhou, 2024).

This study extends the existing literature by empirically testing career exploration as a mediating mechanism (Chen et al., 2022), addressing a gap in prior research that has often proposed but not rigorously examined this linkage. Previous studies have shown the influence of support on outcomes like vocational identity and decision-making self-efficacy (Kleine et al., 2021); this research advances the field by demonstrating how exploration serves as a behavioral conduit connecting support to adaptability.

A further contribution lies in distinguishing between general perceived social support and career-specific parental behaviors. The lack of correlation between these variables suggests they represent distinct constructs with unique implications for intervention. Programs designed to enhance career adaptability may benefit from separately targeting parental engagement and broader support networks, recognizing their differential roles in shaping exploratory behavior (Guan et al., 2018; Hlad′o et al., 2020; Hlaďo & Ježek, 2018).

In sum, this study offers new insight into the developmental mechanisms underpinning career adaptability in emerging adulthood. By confirming a partially mediated model, it affirms that adaptability is fostered through the interplay of self-directed exploration and contextual support. These findings support a holistic, ecological approach to career development and inform strategies in education and counseling aimed at promoting adaptability through both individual agency and systemic support.

Theoretical Implications

This study makes important theoretical contributions by illuminating the mediating role of career exploration in the relationships among perceived social support, career-specific parental behaviors, and career adaptability. The findings both reinforce and extend established career development frameworks, particularly Career Construction Theory (Savickas, 2020) and Social Cognitive Career Theory (Brown & Lent, 2023), through empirical validation of career exploration as a critical link between external influences and internal adaptability resources. SEM confirms the conceptual coherence and empirical strength of these relationships.

Career exploration emerges as a central psychological process that transforms external supports—namely, career-specific parental behaviors and general perceived social support—into enhanced career adaptability. Whereas prior research (Acoba, 2024; Guan et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2022) often examined these variables in isolation, this study clarifies how career exploration operationalizes supportive inputs to yield adaptive outcomes. The observed partial mediation indicates that exploration functions not merely as a byproduct of support but as an active mechanism channeling its effects. This aligns with Career Construction Theory, which conceptualizes career development as a sequence of adaptive readiness, adaptability resources, and adapting responses (Savickas, 2020); career exploration represents the “adapting response” activated by readiness factors like social support, ultimately fostering adaptability. Likewise, Social Cognitive Career Theory’s focus on learning experiences and self-directed behaviors is enriched by this mediation model, demonstrating how social and familial influences are internalized through exploratory actions (Lent & Brown, 2019). Consequently, these findings both validate and advance these theoretical frameworks by elucidating the mediating processes through which environmental resources foster personal career adaptability.

Moreover, this study distinguishes the unique and additive impacts of career-specific parental behaviors and general social support on career adaptability. Both factors exerted significant direct effects even after accounting for career exploration, suggesting that these sources of support operate through partially independent pathways. This distinction supports the theoretical view that proximal (e.g., parental) and distal (e.g., broader social) support systems should be considered complementary rather than redundant components within a young person’s career development ecology. Developmental and ecological models of career development, such as Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory applied to career contexts, can benefit from this nuance, underscoring the importance of addressing both family-specific behaviors and broader social environments in interventions aimed at enhancing career adaptability. The dual-pathway finding thus advocates for a multilayered understanding of social influence in career development.

Finally, the results emphasize the contextual and developmental relevance of social influences on career adaptability, especially within collectivist or family-centered cultures. Parental behaviors may play a particularly strong role in shaping career exploration and adaptability in sociocultural contexts where familial expectations and interdependence are integral to identity formation. This aligns with emerging culturally informed career theories that highlight relational influences in non-Western populations (Yang & Su, 2025; Yao & McWha-Hermann, 2025). Additionally, the findings carry implications for lifespan and developmental career theories, identifying adolescence and early adulthood—the periods represented in this sample—as critical windows for cultivating career adaptability through exploration. Career interventions targeting these stages could enhance both immediate and long-term adaptability by promoting exploration opportunities and strengthening supportive relationships. Collectively, these findings contribute to a dynamic understanding of career adaptability as a construct that is socially scaffolded, contextually grounded, and developmentally nurtured.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences regarding the relationships among perceived social support, parental career-specific behaviors, career exploration, and career adaptability. While SEM offers a robust analytical approach, it cannot replace longitudinal data in establishing temporal precedence or directionality. Second, reliance on self-reported measures may introduce social desirability bias and common method variance, potentially inflating or obscuring the true associations among variables. Lastly, the study focused on a select set of variables, omitting potentially significant mediators or moderators such as self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, identity development, or contextual influences like peer or school factors. These unexamined constructs may also substantially influence career adaptability and account for variance beyond the current model.

To advance this research, future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to elucidate how social support, parental behaviors, career exploration, and adaptability evolve over time. Such designs would allow for rigorous testing of mediation pathways and directional hypotheses. Experimental or intervention studies are recommended to evaluate the effectiveness of targeted strategies—such as parental coaching or peer mentoring—in enhancing career adaptability via career exploration. Additionally, future research should investigate moderating factors including socioeconomic status, educational attainment, and cultural background, which may affect the strength or direction of these relationships. Expanding the model to incorporate psychological constructs such as identity formation, resilience, and future orientation would provide a more comprehensive understanding of career adaptability. Contextual supports, including school-based guidance programs and peer influences, also warrant examination as complementary factors. Finally, cross-cultural comparative research is essential to determine the universality or cultural specificity of these dynamics, potentially uncovering important variations in how social and familial factors interact with individual agency across diverse sociocultural environments. These extensions will enrich theoretical frameworks and enhance the practical relevance of career development research.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for stakeholders engaged in career development, particularly in fostering career adaptability among youth. By identifying career exploration as a partial mediator between perceived social support, parental career-specific behaviors, and career adaptability, this research provides empirical support for integrated strategies that encompass individual, familial, and institutional influences to strengthen career readiness. Career adaptability—a critical competency for navigating evolving labor markets—can be cultivated not only through direct interventions but also by reinforcing the support systems and exploratory processes underpinning adaptive capacities. The mediating role of career exploration highlights the importance of experiential and reflective learning opportunities in translating social and parental inputs into meaningful adaptability outcomes.

Career counselors and educators should prioritize structured, developmentally appropriate career exploration programs that include activities such as self-reflection, goal setting, occupational research, internships, job shadowing, and career simulations. The significant mediating effect of career exploration underscores these programs’ critical role in converting external support into internal adaptability. Moreover, this study advocates for family-inclusive career guidance, encouraging counselors to organize parent engagement seminars or workshops to disseminate evidence-based strategies for supporting children’s career development. Facilitating parent-child dialogues about vocational interests and exploration can amplify parental influence. Educators are encouraged to embed career development within curricula through interdisciplinary approaches, normalizing career exploration as a valued component of the educational experience. Institutionalizing such supports enables schools to become proactive environments where adaptability is cultivated through social influence and self-directed inquiry.

Parents should recognize that career-specific behaviors—such as discussing career options, modeling decision-making, and encouraging exploratory activities—have a distinct and measurable impact on their child’s career adaptability. While general emotional support remains important, it alone is insufficient. Practical actions, including arranging workplace visits, connecting youth with professionals, setting clear career goals, and facilitating internship opportunities, foster adaptive confidence and decision-making skills. These findings position parents not merely as emotional anchors but as active agents in their children’s vocational identity development and career planning.

Policy makers are encouraged to support the integration of career exploration modules within secondary and post-secondary curricula, ensuring equitable access across socioeconomic groups. Funding priorities should emphasize programs that develop robust support networks—such as mentorship schemes, alumni panels, and peer advisory boards—to enhance the effects of social support and exploratory engagement. Institutional policies should incentivize partnerships among schools, industries, and families to establish community-based exploration opportunities. Such initiatives align systemic support with youth’s developmental trajectories, ultimately contributing to a more adaptable and career-ready workforce.

Youth development organizations can leverage these findings to design targeted interventions that cultivate both career exploration skills and adaptive mindsets. Programs might include workshops focused on decision-making, future orientation, and proactive planning. Additionally, fostering social capital through peer networks, community mentors, and structured group activities can complement exploration-based initiatives to reinforce adaptability outcomes. By embedding both social and experiential elements, these programs can create holistic developmental environments where youth are prepared to navigate uncertainty, make informed choices, and adapt flexibly to career challenges throughout life.

Table 2.

Standard Regression Weight in the Full Mediation and Indirect Model.

Table 2.

Standard Regression Weight in the Full Mediation and Indirect Model.

| DV |

|

IV |

Mediation Model |

|

Indirect Model |

| UNStd |

95% CI |

β |

|

|

| CEX |

← |

PSS |

.091 |

[.024, .157] |

.348**

|

|

|

| CEX |

← |

PCB |

.319 |

[.207, .467] |

.59***

|

|

|

| CAD |

← |

CEX |

1.093 |

[.420, 2.257] |

.452*

|

|

|

| CAD |

← |

PCB |

.485 |

[.037, .975] |

.371*

|

|

.349**

|

| CAD |

← |

PSS |

.207 |

[.034, .356] |

.327*

|

|

.099*

|

| Note.CEX: Career Exploration, PSS: Perceived Social Support, PCB: Perceived parental career behaviors, CAD: career adaptability. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. |