Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Foreword

Content

- (1)

- Plate pouring (section 1.1). Consistency in plate pouring is essential for chemical genomic screens as it ensures uniform colony growth, accurate phenotypic observations, and reproducibility by providing consistent surface conditions and even distribution of stress conditions. Proper techniques also minimise contamination and variability, improving the reliability of screening results.

- (2)

- Source plate production (section 1.2). Source plates serve as templates, ensuring consistent and reproducible sample distribution. They enable high-throughput screening by allowing transfer of strains to condition plates, reducing contamination and variability while preserving genetic diversity.

- (3)

- Pre-testing (section 1.3). Pre-testing helps validate assay conditions, optimise protocols, and identify potential issues before large-scale screening. This reduces errors, ensures reproducibility, and improves the reliability of results by confirming that the screen functions as intended.

- (4)

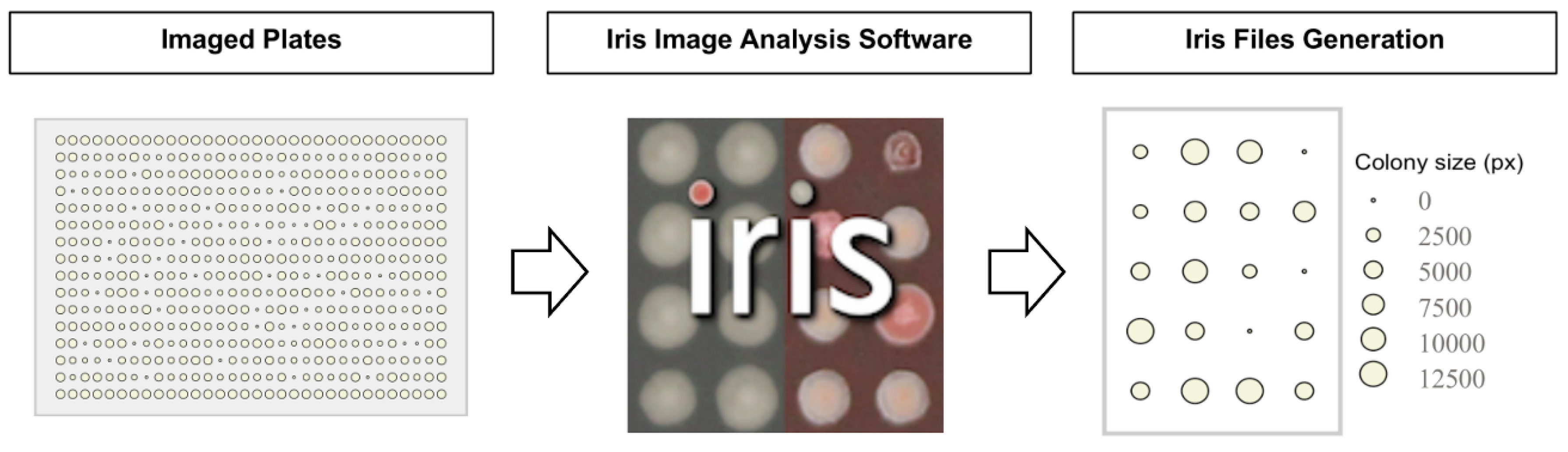

- Screening methodology (section 2). This section describes the methodology used for stamping source plates to condition plates. It is designed specifically for the image analysis software, Iris (Kritikos et al., 2017). Additionally, the protocol includes guidance on biofilm-specific screens (section 4.3), a research area of growing importance given the role of biofilms in bacterial persistence and resistance.

- (5)

- Computational analysis (section 3). Iris (section 3.1) and phenotypic analysis software, ChemGAPP (section 3.2) (Doherty et al., 2023) to ensure that phenotypic data is accurately quantified and interpreted.

1. Pre-screening

1.1. Plate Pouring

Purpose

Materials

- VWR Single Well Plates (Cat no: 734-2977) or any other single-well plate.

-

Suitably sized stripette for drawing up media to correct volumes.

- o

- Alternatively, a suitably sized vessel can be used instead for directly pouring into plates.

- Glass bottles (autoclavable).

- Base growth medium appropriate for your bacterial species.

- Agar – to achieve 2% (w/v) plates.

- Distilled (type 2) water.

- The experimenter's choice of stress conditions e.g. antibiotics (section 1.3).

Method

- (1)

- Prepare Growth Media: Use 2% agar and ensure all components are fully dissolved and mixed with a magnetic stirrer. Adjust pH as needed (Plate Pouring Challenges and Solutions). Autoclave the media before use.

- (2)

- Add Stress Conditions: Add stresses once the agar reaches an appropriate temperature. Mix thoroughly to ensure even distribution.

- (3)

- Pour Plates Aseptically: Pour agar into pre-labelled plates using sterile technique (e.g., Bunsen burner or safety cabinet). Use a consistent volume suited to the plate type e.g., 40 mL for VWR one-well plates (~2/3 full) to reduce dehydration.

- (4)

- Dry Plates Before Use: Allow plates to fully solidify. Do not use immediately; instead, invert and dry at room temperature for 16 hours to remove excess moisture.

| Section 1.1 Plate Pouring Challenges and Solutions | ||

| Challenge | Issues | Solution |

| Plate Labelling | Plate naming inconsistency can impact the ease of tracking screening progress and labels on the bottom of plates can impact the image analysis. | Label all plates with a consistent system throughout the screen on the plate's side |

| Reducing Variation | Plate batch can have an impact on the observed colonies. | Plate batches should be recorded and accounted for in the results. |

| Consideration of Growth Medium Agar Temperature | Keeping the growth medium agar at room temperature for an extended period will make it begin to solidify unevenly, which results in clumps of agar forming in newly poured plates. | Place autoclaved agar immediately into a 55-65°c water bath or incubator. (Note that some condition additives may be temperature sensitive and may need to be added at a different temperature.) |

| Plate drying | Good plate drying can be time-consuming at room temperature. | The drying process can be sped up by drying plates under a steady flow of air within a laminar flow hood. Be mindful, as drying the plates out too much often introduces pinning artefacts. |

| Plate storage | Plates may dry out if not stored correctly when longer-term storage is required. | Plates can be stored safely in a fridge (4-8°C) for up to 4 weeks. However, this depends on the condition (e.g. some additives may precipitate at 4°C). |

| Setting plates | Biased plate surfaces will lead to inconsistencies in colony transfer during pinning. | Ensure the surface that you pour plates on is level. |

| Plate drying during incubation | Plates can dry out during incubation based on agar thickness and the organism on the plates growth time. | For faster-growing organisms, agar volumes of 40 mL are appropriate (if using VWR one-well plates). For slower-growing organisms, such as Mycobacterium bovis BCG, thicker plates are recommended (45-50 mL agar volumes) to prevent plates from completely drying during incubation. Incubators with humidity are also recommended for slower growing organisms to reduce the rate of evaporation. |

1.2. Source Plates

Purpose

- (1)

- Library plates: These plates are the original stocks of bacteria and are typically stored as liquid culture. Usually, for long-term storage of the bacteria they are mixed with glycerol or DMSO to act as cryoprotectant and stored at -80 °C.

- (2)

- Source plates: These plates contain growth medium that are either in solid or liquid format depending on the strains of interest. They are generated from liquid culture (library plates) and are the principal plates to be pinned/stamped out onto condition plates (solid or liquid plates).

Materials

- Prepared growth media plates from section 1.1, containing no stressor.

- Library plates.

- Pinning robot

- 70% ethanol for cleaning the robot (section 4.5).

Method

- (1)

- Thaw and Prepare Library Plates: Fully thaw library plates before transfer. Centrifuge at low speed (~250 x g for 1 minute) to collect contents before removing the seal.

- (2)

- Create Source Plates: Use a pinning robot or hand-pinning tool to transfer glycerol-stored strains from library plates onto growth media, generating new source plates. Multiple library plates can be combined into various screening formats (Figure 2). Additional information related to creating and storing source plates can be found in Source Plate Challenges and Tips.

- (3)

- Maintain Sterility and Optimise Growth: Ensure sterile technique during transfers and use sealing films suited to the plate type. During media transfer (section 2.1), aspirate any residual media from pipette tips. Adjust growth time and temperature based on the organism and plate format, for example, 1536-format plates typically require shorter incubation than 96-format plates due to tighter colony spacing.

| Section 1.2 Source Plates Challenges and Solutions | ||

| Challenge | Issues | Solution |

| Defrosting | Insufficient defrosting of plates and centrifugation of plates prior to plate pinning. This process ensures that a sufficient amount of bacteria is pinned onto the source plates, and reduces the risk of cross-contamination upon removal of plate seals. | Ensure that any original frozen libraries in library plates stored at -80 °C are thoroughly defrosted at room temperature and then centrifuged prior to being pinned. |

| Viability of Source Plates | Ensure that species are still viable before commencing the screen. Once prepared, they can remain viable for up to four weeks when stored at 4–7°C. | Generally, source plates can remain viable for up to four weeks when stored at 4–7°C. After this period, re-pinning is required; however, this is species-dependent. |

| Replicate Plate Copies | Ensure to create sufficient replicate plate copies to avoid having to undertake unnecessary repeats. | For all stored library plates, it is strongly advised to create at least two identical copies of these plates and store these appropriately. This step can be undertaken manually or using an automated liquid handler. |

1.3. Pre-Testing

Purpose

Materials

- All produced condition plates (section 1.1).

- Source plates (section 1.2).

- Incubator.

Method

- (1)

- Optimise Pre-testing: Determine stress concentrations that allow sufficient growth with visible phenotypic differences (See Plate Pouring and Pretesting and Tips). If unclear, use MIC broth microdilution for guidance (see Pretesting Challenges and Tips).

- (2)

- Standardise Format: Use consistent plate formats and growth media across the screen to ensure comparability.

- (3)

- Refine Incubation: Adjust incubation time based on organism and stress level. Use control plates (no stress) to benchmark growth rates and compare with condition plates to define a dynamic range. For example, if control growth occurs at 9 hours, low and high stress may delay growth to 10 or 12 hours respectively. Ensure colonies remain resolvable for Iris analysis.

- (4)

- Prevent Artefacts: Control for issues like colony overlap, edge effects, and contamination to improve data quality (Figure 4; section 4.1).

| Section 1.3 Pre-testing Challenges and Solutions | ||

| Challenge | Issues | Solution |

| Determining Stress Concentrations | The optimum concentration needs to be investigated to determine a suitable concentration for the entire microbial library present on the condition plates. | Consult literature data for conditions, examples such as (Brochado et al., 2018) and (Nichols et al., 2011). Websites such as EUCAST (Kahlmeter G et al., The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing - EUCAST. 2025 https://www.eucast.org/) can be used to help with identifying appropriate antimicrobial concentrations. |

| Serial Dilutions | The MIC must be determined either by literature consultation or through serial dilutions. | For further MIC determination, prepare a serial dilution of the chemical using a 10-fold or 2-fold dilution series on 3-4 conditions to stimulate the dynamic range. The final concentrations must span across a range expected to include the MIC for the species you're testing. Use pre-testing plates for this purpose. |

| Determining Incubation Time | Ensure that incubation time is optimised for specific species being screened. | If this is the first time performing the procedure on a screening plate, check the plates hourly to determine the optimal incubation time for the strains. This will establish a baseline incubation period, which can then be applied consistently for all strains in the screen. |

| Stamping Source Plates to Condition Plates | Over-stamping a source plate can dilute the transferred cell mass, leading to inaccurate results. | Determining the number of condition plates per source plate is important as the source plate serves as a biological replicate. An initial test screen using one source plate and multiple condition plates is recommended. Typically, 10–15 plates can be stamped from a single source plate (section 4.4, Table 2). |

| Plate Format for Biofilms | Growth media plates may not be suitable for strains forming biofilms (section 4.3). | Typically, solid source plate to solid screening plate stamping is conducted to ensure a consistent amount of cell mass is transferred for each strain. In cases where growth media plates are not suitable for specific species, liquid culture can be used instead as a source plate: thaw glycerol stocks, inoculate a fresh liquid culture plate to saturation, and then stamp directly onto condition plates to maintain uniform cell transfer. |

2. Screening

Purpose

Materials

- A pinning head (a tool used to replicate plates typically in 96, 384, or 1536 configurations) (section 4.5).

- 70% ethanol for sterilising.

- Condition plates containing conditions (section 1.3 for choices).

- Source plates (section 1.2).

- Static incubator.

Method

- (1)

- Prepare condition and Source plates: Inspect all plates for defects (e.g., bubbles, uneven surfaces) and if they have been contaminated. Discard all plates that fail this final quality control. To avoid pinning artefacts, we recommend bringing source plates to room temperature (Source Plates Challenges and Tips).

- (2)

- Ensure Sterility: In a sterile environment, ensure that pinning components are clean (Screening Challenges and Tips).

- (3)

-

Pinning Procedure: Select an appropriate pinning protocol (section 4.4, Table 2 for replication limits per source plate). A single source plate can be used to stamp multiple condition plates (Source Plates Challenges and Tips). Pinning involves:

- a.

- Aligning the pinning head over each strain on the source plate.

- b.

- Gently lowering it to pick up a small, consistent amount of material.

- c.

- Transferring material by lightly touching the pins to the condition plate without piercing the agar.

- (4)

- Sterilise Between Source Plates: When switching source plates, sterilise the pinning head with 70% ethanol and allow to air dry before repeating the pinning process (Screening Challenges and Tips).

- (5)

- Incubation: Place condition plates in a static incubator at the appropriate temperature and duration for the organism used (section 1.3).

- (6)

- Imaging: Once colonies reach an appropriate size for image analysis (e.g., via Iris), remove plates from the incubator and proceed with imaging.

| Section 2 Screening Challenges and Solutions | ||

| Challenge | Issues | Solution |

| Condensation | Plates develop condensation on the lid after bringing the plates up to room temperature. | Remove all condensation by wiping the plates with a tissue that has been pre-wet with 70% ethanol for sterility. |

| Importance of Sterilisation | Potential for cross- contamination when using a reusable pinning tool. | Ensure thorough sterilisation between sources. Debris can be removed using a brush and water and the pins can be sterilised by submerging the head in 70% ethanol for 10 seconds and allowing it to air-dry. Alternative methods, such as autoclaving or using Virkon solutions, may be used depending on the tool, as well as disposable pinning heads (section 4.5). Refer to the manufacturers' protocols for this purpose. |

| Order of Plate Stamping | When stamping condition plates from source plates, the order of conditions matters. The initial stamping from a source plate transfers more cell mass, potentially affecting results. | It is recommended to assign the first condition plate containing a stress which is expected to elicit a strong effect to minimise the impact of the higher cell mass. |

3. Imaging & Data Analysis

3.1. Taking Images & Iris

Purpose

Materials

- Camera: A built-in fixed 18-megapixel Canon EOS Rebel T3i camera (Canon) is used within our group; however, generally any suitable camera to take plate images can be used. Refer to the robot manufacturers' protocols for guidance on specific types of cameras that are suitable for the robot type.

- Ensure to maintain a fixed distance between the camera and plates as well as consistent lighting, preferably with a lightbox. This minimises variability across images.

- Software: S&P Imager (S&P Robotics, version 2.0.1.0) and EOS Utility (Canon, version 2.10.0.0) is used within our group.

Method

- (1)

- Capture Images: We recommend using an automated plate imaging system that is able to capture pictures of condition plates with consistent lighting and focus (Imaging & Data Analysis Challenges and Tips).

- (2)

- File Naming and Analysis: Name image files using the format: Condition_Concentration_SourcePlate_Replicate. This format is optimised for Iris but works with other analysis tools as well. For full Iris method details, see Kritikos et al., (2017) (Imaging & Data Analysis Challenges and Tips).

| Section 3.1 Imaging & Data Analysis Challenges and Solutions | ||

| Challenge | Issues | Solution |

| Image Lighting | Avoid using flash to prevent glare from the agar. | If additional lighting is needed, position the light source to the side of the plate. |

| Quality of Camera | Capturing good-quality images. | Use a high-quality camera capable of producing images with a minimum resolution of 18 megapixels. |

| Naming System | Avoiding confusion during analysis. | Establish a logical and coherent naming system for plates. |

3.2. Phenotypic Analysis (ChemGAPP & Data Visualisation)

Purpose

- (1)

- ChemGAPP Big: for large-scale, genome-wide screens.

- (2)

- ChemGAPP Small: for targeted hypothesis testing or small-scale mutant analyses.

Materials

Method

- (1)

-

Large-Scale Screens – ChemGAPP Big: ChemGAPP Big (Figure 7) is designed for full-genome chemical-genomic screens. The pipeline begins with optional quality control (QC) checks to flag poor-quality replicates or plates. It then performs two stages of normalisation:

- Edge effect correction: A Wilcoxon rank-sum test compares colony sizes at the plate centre vs. edge to correct for border artefacts.

- Scaling: All plates are adjusted so their medians match the average colony size at the plate centre, standardising across conditions.

- (2)

- Small-Scale Screens – ChemGAPP Small: ChemGAPP Small is suitable for focused experiments involving a limited number of strains or conditions. Unlike ChemGAPP Big, it does not assume a defined fitness distribution.

- a.

- Mutant vs. Wildtype: using the ratio of mean colony sizes.

- b.

- Mutant vs. Control Condition: allowing inference of fitness under treatment vs. baseline.

- (3)

- To run ChemGAPP:

- a.

- Export data from your plate reader or image analyser in `.iris` format.

- b.

- Upload the files to ChemGAPP via the web interface or command-line.

| Section 3.2 Phenotypic Analysis Challenges and Solutions | ||

| Challenge | Issues | Solution |

| File format | ChemGAPP only accepts `.iris` files. | If using other analysis software, the output may need to be converted. |

| File naming | Proper naming is essential to avoid analysis errors. | ChemGAPP includes a file renaming tool to standardise filenames and avoid analysis errors. |

4. Additional Considerations

4.1. Troubleshooting

4.2. Recycling

- (1)

- Clean Used Plates: Remove old agar with a spatula, taking care not to scratch the plates. Place empty plates in an airtight box and soak overnight in 5% (w/v) Virkon or an appropriate laboratory disinfectant.

- (2)

- Rinse and Dry: Rinse thoroughly with water to remove disinfectant residue. Dry plates in a 60 °C incubator for at least 24 hours. To reduce excess moisture, place a salt desiccant in the incubator.

- (3)

- Inspect and Store: Discard any damaged plates. Store clean, undamaged plates in a sealed container for future use.

4.3. Biofilm Screening

4.4. Species-Specific Considerations

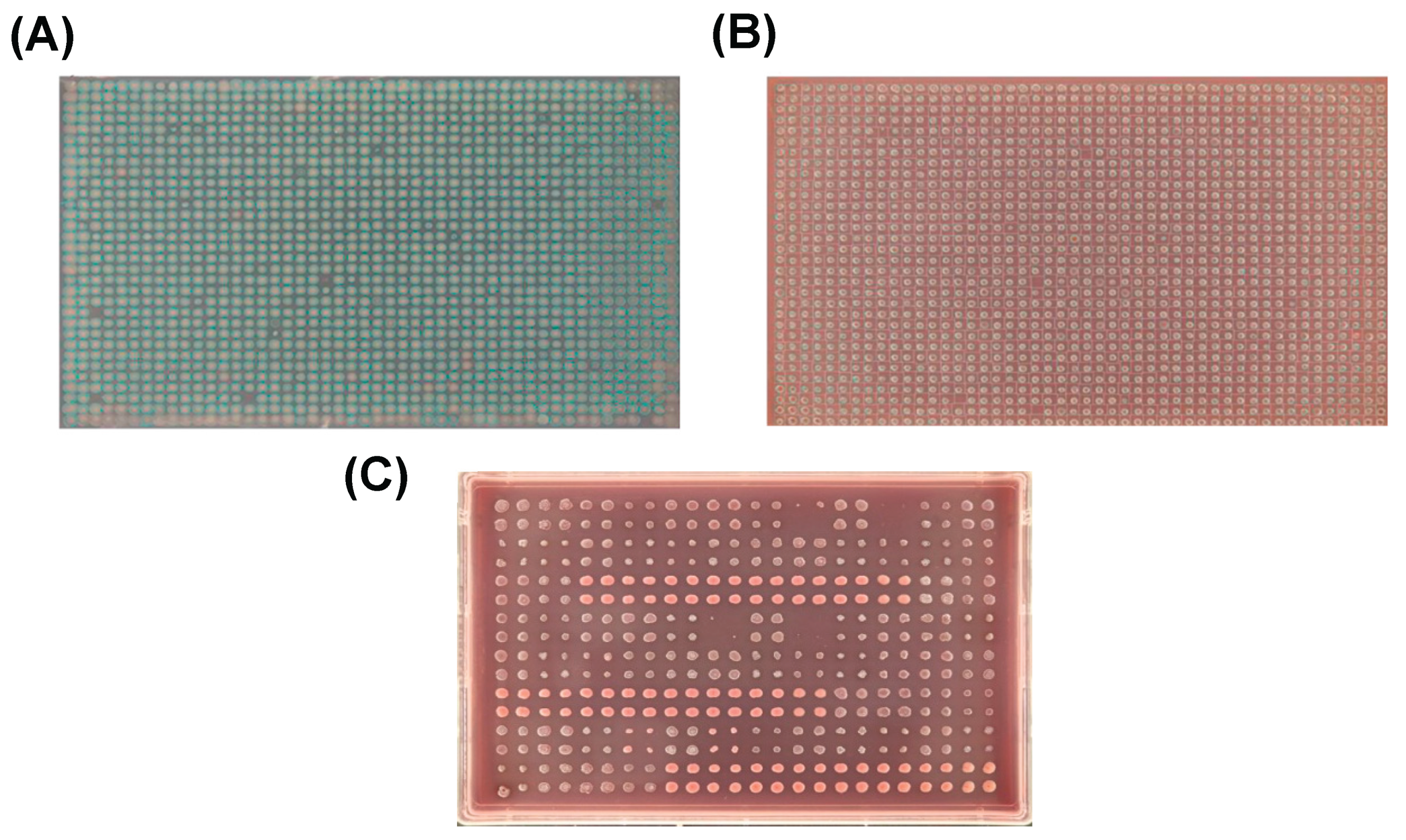

- Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae can be grown on agar made by combining LB Lennox Broth (Tryptone 10 g/L, NaCl 5 g/L, Yeast Extract 5 g/L) and Agar 15g/L.

- Salmonella enterica on LB Miller Broth (Tryptone 10 g/L, NaCl 10 g/L, Yeast Extract 5 g/L) and Agar 15g/L.

- Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and Mycobacteroides abscessus can be grown using an enriched 7H9 media supplemented with 1% (w/v) glycerol, 10% (w/v) ADC, 0.2% (w/v) BactoTM cas amino acids, 50 μg/ml L-Tryptophan and 50 μg/mL Natures Aid multivitamins and then plated onto 7H9 agar using 2% (w/v) BD Difco™ agar and 7H9 media. Optionally, add 25 μg/mL of amphotericin B to inhibit fungal contamination. To prevent from drying out during the incubation period, ensure to monitor the humidity using a hygrometer if possible or by using a water reservoir and mimising the air flow. The liquid BCG culture that is being pinned should be shaken at 25 rpm before use in the pinning operation.

4.5. Screening Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alodaini D, Hernandez-Rocamora V, Boelter G, Ma X, Alao MB, Doherty HM, et al. Reduced peptidoglycan synthesis capacity impairs growth of E. coli at high salt concentration. mBio. 2024 Apr 1;15(4):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Bobonis J, Mitosch K, Mateus A, Karcher N, Kritikos G, Selkrig J, et al. Bacterial retrons encode phage-defending tripartite toxin–antitoxin systems. Nature. 2022 Sep 1;609(7925):144–50. [CrossRef]

- Brochado AR, Telzerow A, Bobonis J, Banzhaf M, Mateus A, Selkrig J, et al. Species-specific activity of antibacterial drug combinations. Nature. 2018 Jul 12;559(7713):259–63. [CrossRef]

- Cacace E, Kritikos G, Typas A. Chemical genetics in drug discovery. Current Opinion in Systems Biology. 2017 Aug 1;4:35–42. [CrossRef]

- Dittmar JC, Reid RJ, Rothstein R. Open Access SOFTWARE ScreenMill: A freely available software suite for growth measurement, analysis and visualization of high-throughput screen data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:353. [CrossRef]

- Doherty HM, Kritikos G, Galardini M, Banzhaf M, Moradigaravand D. ChemGAPP: a tool for chemical genomics analysis and phenotypic profiling. Bioinformatics. 2023 Apr 1;39(4):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ezraty B, Vergnes A, Banzhaf M, Yohann D, Huguenot A, Brochado A, et al. Fe-S Cluster Biosynthesis Controls Uptake of Aminoglycosides in a ROS-Less Death Pathway. Science. 2013 Jun 28;340(6140):1580–3. [CrossRef]

- Fajardo A, Martínez-Martín N, Mercadillo M, Galán JC, Ghysels B, Matthijs S, et al. The neglected intrinsic resistome of bacterial pathogens. PLoS ONE. 2008 Feb 20;3(2). [CrossRef]

- Flemming HC, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Vol. 14, Nature Reviews Microbiology. Nature Publishing Group; 2016. p. 563–75. [CrossRef]

- Gomez MJ, Neyfakh AA. Genes involved in intrinsic antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter baylyi. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2006 Nov;50(11):3562–7. [CrossRef]

- Koo BM, Kritikos G, Farelli JD, Todor H, Tong K, Kimsey H, et al. Construction and Analysis of Two Genome-Scale Deletion Libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell Systems. 2017 Mar 22;4(3):291-305.e7. [CrossRef]

- Kritikos G, Banzhaf M, Herrera-Dominguez L, Koumoutsi A, Wartel M, Zietek M, et al. A tool named Iris for versatile high-throughput phenotyping in microorganisms. Nature Microbiology. 2017 Feb 17;2(1):1–24. [CrossRef]

- Nichols RJ, Sen S, Choo YJ, Beltrao P, Zietek M, Chaba R, et al. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell. 2011 Jan 7;144(1):143–56. [CrossRef]

- Schuldiner M, Collins SR, Thompson NJ, Denic V, Bhamidipati A, Punna T, et al. Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell. 2005 Nov 4;123(3):507–19. [CrossRef]

- Tamae C, Liu A, Kim K, Sitz D, Hong J, Becket E, et al. Determination of antibiotic hypersensitivity among 4,000 single-gene-knockout mutants of Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008 Sep;190(17):5981–8. [CrossRef]

- Tong AHY, Evangelista M, Parsons AB, Xu H, Bader GD, Pagé N, et al. Systematic Genetic Analysis with Ordered Arrays of Yeast Deletion Mutants. Science. 2001 Dec 14;294(5550):2364–8. [CrossRef]

- Typas A, Banzhaf M, van den Berg Van Saparoea B, Verheul J, Biboy J, Nichols RJ, et al. Regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis by outer-membrane proteins. Cell. 2010 Dec 23;143(7):1097–109. [CrossRef]

- Wagih O, Parts L. Gitter: A robust and accurate method for quantification of colony sizes from plate images. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2014;4(3):547–52. [CrossRef]

| Issue | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uneven shading across the plate. | Insufficient mixing of LB media before plate pouring. | Ensure thorough mixing of agar. It is recommended to use a magnetic stirrer. |

| Unstable agar under certain conditions. | Insufficient mixing of the condition and/or the condition is not stable within the media. Conditions can prevent the agar from solidifying such as pH and Sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). |

Use a magnetic stirrer and/or check and optimise the suitability of condition concentration such as adjusting the pH to ensure agar solidifies. |

| Bubbles in the agar. | Some detergents, such as SDS, have a greater tendency to form bubbles within the agar. | A flaming technique can be used to resolve this issue. |

| Fungal contamination after incubation. | High humidity in the incubator. | Use humidity-controlled incubators (max 20% humidity). Place a water tray in incubators with low humidity. Consider the use of an antifungal to decontaminate. |

| Outer edge effects of colonies & distortion. |

Increased growth at the edge of solid agar due to reduced nutrient competition. This problem is exacerbated if present on source plates. | Ensure adequate mixing of media & chemicals/dyes before plate pouring. Reduce incubation time. |

| Biofilm formation (sticky/thin glossy covering on plate). | Plates are left too long in the incubator. Species are prone to biofilm formation. Unsuitable conditions can enhance biofilm formation. Plates are too cold, affecting colony attachment. |

Reduce incubation time and/or temperature. Use broth media with higher salt content and avoid no salt conditions. Allow plates to adjust fully to room temperature before use. |

| Colonies are fusing with each other. | Plates are overgrown plates leading to cross-contamination. Incubation time is too long. |

Reduce incubation time and/or temperature. Store plates in the fridge after incubation. Ensure agar is uniformly distributed. |

| No colonies observed on plates. | Poor transfer of bacterial strains or poor pre-testing conditions. | Check library plates for growth on normal media. Verify pre-testing conditions or perform broth microdilution assays to obtain MIC values. |

| Reduced colony size. | Plates have not been incubated long enough. Condition concentrations may be too high. |

Incubate the plate for a longer time. Reduce the condition plate concentrations. |

| Colonies show swarming effects/motility. | Media is not ideal for bacteria or plates incubated for too long. | Alter the salt composition of media, shorten incubation time, or use a smaller plate format. |

| Species | Biofilm Formation |

Growth Time | Motility (swarming effect) | Consistent growth on solid agar | Storage Stability of Source Plates | Plate replication | No. condition plates from source plate |

| Escherichia coli | * | ~6 hours | * | + | ** | S-S | ~11 |

| Vibrio cholerae† | ** | ~24 hours | * | + | * | S-S | ~11 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | *** | ~6 hours | ** | + | *** | S-S | TBD |

| Staphylococcus aureus | TBD | ~16 hours | * | + | *** | S-S | ~10 |

| Salmonella enterica | * | ~6 hours | *** | + | *** | S-S | ~11 |

| Mycobacterium bovis BCG†† | * | ~2 weeks | * | - | ** | L-S | TBD |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | **** | **** | * | + | ** | S-S | TBD |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | * | ~6 hours | * | - | *** | S-S L-S |

~22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).