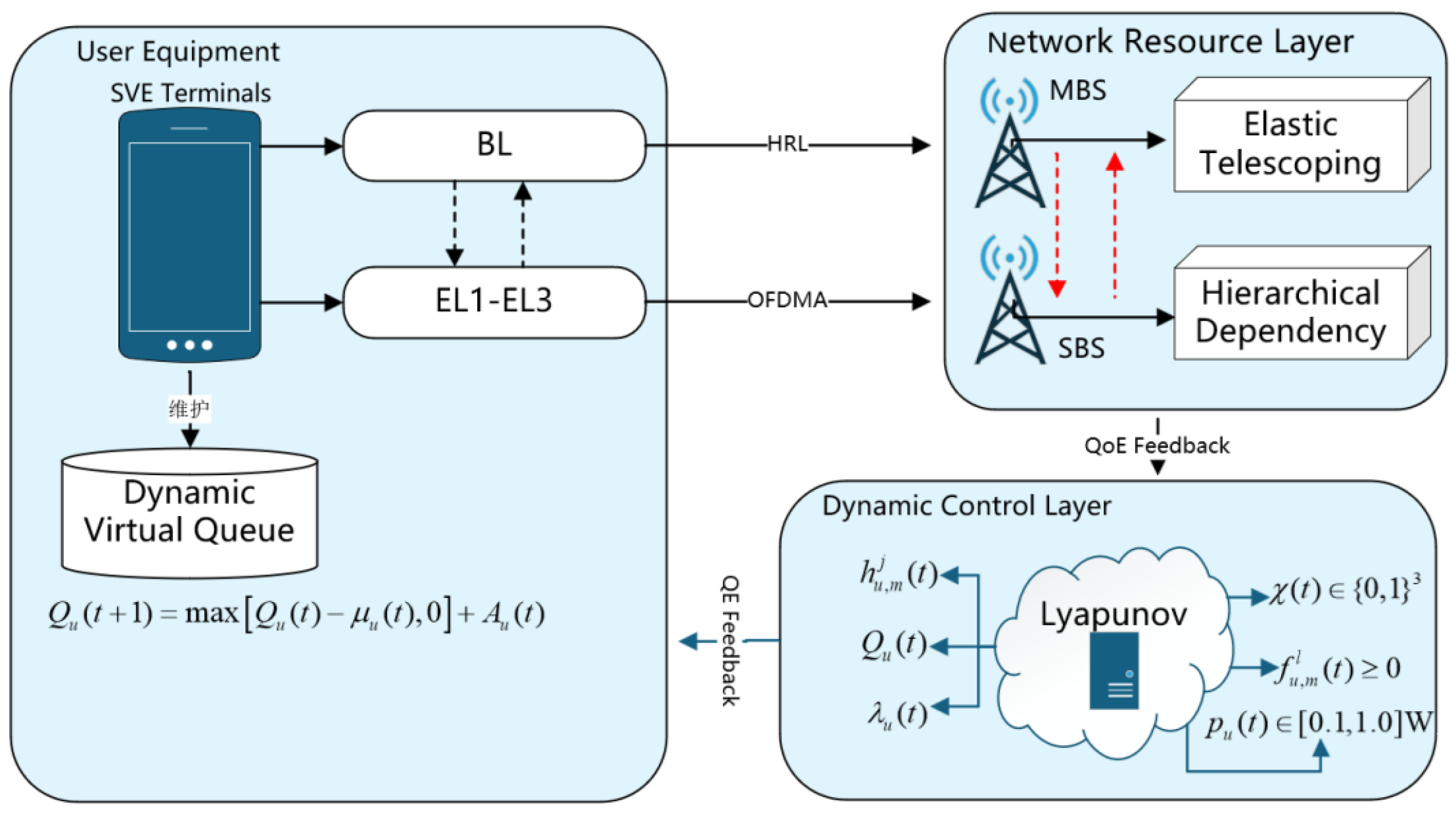

As shown in

Figure 1, in this paper, we propose a collaborative architecture that integrates SVC, MEC and Lyapunov for real-time video streaming transmission requirements in highly dynamic network environments. Where

represents channel state;

represents queue backlog;

represents task arrival rate;

represents offloading decision;

represents resource allocation;

represents power control.

The system architecture comprises three functional components: a mobile client, a network resource layer, and a dynamic control layer [

20]. The mobile client implements SVC-based decomposition of video streams into base layer (BL) and enhancement layers (EL1-EL3) with hierarchical dependencies, and establishes a dynamic virtual queue to enable real-time feedback of task backlog status. The base layer is preferentially offloaded to macro base stations through ultra-reliable low-latency communication (URLLC) links, while the enhancement layers dynamically select OFDMA subbands for transmission to small base stations based on channel state prediction [

21]. The network resource layer integrates heterogeneous computing resource pools from macro/small base stations, performs on-demand resource allocation through elastic scaling mechanisms, and enforces layered dependency constraints to ensure video transmission integrity [

22]. The dynamic control layer incorporates Lyapunov optimization modules to jointly optimize offloading policies, resource allocation weights, and power control parameters in real time, achieving dynamic balance between user experience quality maximization and queue stability through Drift-plus-Penalty minimization [

16]. This architectural design overcomes randomness constraints in resource allocation for hyper-dynamic environments, establishing a closed-loop scheduling mechanism through hierarchical decoupling and online optimization decision-making. Used

to denote the users in the mobile video system, each user generates a real-time video stream with frame rate

and resolution

.

denotes the set of MEC servers, where

is a macro base station,

is a small base station, and the computational power

is heterogeneously distributed with the coverage radius

.

denotes the set of SVC video tiers.

denotes the set of orthogonal subbands with bandwidth

, supporting OFDMA multiple access.

2.1. User Side Mode

Assume that for each user

at the user terminal, there is one and only one video computation task, denoted as

, which is atomic and cannot be divided into subtasks. The performance of each computational task

is expressed as a tuple consisting of two descriptions

, where

denotes the size of the task data transmitted from the user-side device to the MEC server, and

denotes the size of the resources required to complete the computational task, both of which can be obtained based on the size of the user’s task execution data volume. In the MEC system of this paper, each computational task can perform video parsing at the user end or can be offloaded to the MEC server to perform video parsing. By offloading the video computation task to the server, the video user saves the energy required for the computation task, but sending the video task to the uplink adds more time and energy [

23].

Using

to denote the local computing power of user

, in terms of the number of CPU cycles per second, if the user

u performs video parsing locally, the latency to complete the task is:

The energy consumption model is used to represent the energy consumed by the user to parse the video locally. Using

f for the CPU frequency and

for the energy factor, each computation cycle is

, where the size of

is determined by the chip architecture. According to the above model, the energy consumption for locally executing the video task

is:

The user equipment is based on SVC technology, which structures the real-time captured video stream in time slices. Each time slice lasts for 1 second and corresponds to frames of video data, which are generated into layered packets by H.265/SVC encoder: Base Layer (BL) contains 1 frame with NOTICE P frames, with a bit rate of , where K is the compression factor, which determines the minimum acceptable quality of the video, and Enhancement Layer (EL) is realized by layered incremental coding, where the bit rate of the first layer is the enhancement rate, providing resolution enhancement or dynamic range extension. The EL is realized by layered incremental coding, where the code rate of layer one is the enhancement rate, which provides resolution enhancement or dynamic range extension. This hierarchical structure allows users to flexibly choose the transmission layer according to the network conditions.

2.2. Task Offloading Model

Assuming a multi-user multi-MEC server architecture where each user’s video computation tasks can be selectively offloaded to any available small base station within the system [

5], three distinct latency components emerge during the offloading process: (i) uplink transmission latency when offloading video tasks to MEC servers; (ii) computation processing latency at the base station’s MEC server; and (iii) downlink transmission latency for returning computation results to the user [

24]. Given that uplink data size is typically significantly smaller than downlink data, and considering the inherent asymmetry in wireless channel capacity where downlink data rates substantially exceed uplink rates, the downlink transmission delay can be neglected in computational complexity analysis [

25].

Similar to the literature [

26], this paper applies the Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) technique to the uplink transmission system by dividing the transmission band

B into

W equal sub-bands of size

N, i.e,

, and each BS (Band Width) can receive up to one user’s upload task at the same time. receive upload tasks from

N users simultaneously. Assuming that the set of available subbands for each BS is

, the offloading variable is defined as

considering the allocation of uplink subbands, where

;

denotes that task

offloads the

l layer of the video from user

u to base station

m via subband

j, and

has the opposite meaning. i.e:

Assuming that the task offloading policy is

X, then

. In the system of this paper, each video task can either be parsed locally or offloaded to an associated MEC for parsing. Therefore, the feasibility analysis leads to:

Furthermore, assuming that both the user side and the BS are equipped with a single antenna for uplink transmission, and the power of user

u to transmit a task to the BS is

, then

, denoting the power pooling. Due to the application of OFDMA technology in the uplink, users of the same base station will transmit tasks on different subbands, which well suppresses the mutual interference among subbands [

27]. However, there is still interference between the mobile devices, where the Signal Noise Ratio (SINR) of the user

u uploading the task to the subband

j is:

In the formula, denotes the background noise variance. represents the channel gain coefficient between the base station (BS) and associated users for transmission. indicates the transmit power of user u when offloading tasks to the server. signifies user k uploading the layer of a video through subcarrier j to server m. Furthermore, stands for the transmit power of user k in the process of offloading tasks to the server, and refers to the channel gain coefficient between server and user k for transmission.

The path loss model adopted in this paper [

28] is given by

, where

represents the distance between BSM and user

u (in units of km ). Each user’s video task is transmitted on only one subcarrier; therefore, the rate at which user

u uploads video to server BSM

is:

In the formula,

, where

denotes the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) from user

u to server BSM on subcarrier

j. Consequently, the transmission time for user

u to send video task

over the uplink is given by:

In the equation, , where represents the offloading of the l-th layer of a video from user u to server m via subcarrier j.

2.3. SVC-MEC Computing Resource Integration Model

In dense heterogeneous network environments, this paper formulates a dynamic MEC resource scheduling model tailored for multi-user real-time video streaming demands by leveraging SVC hierarchical characteristics. The proposed model achieves efficient computing resource allocation and QoS guarantees through synergistic integration of multi-BS resource constraints and SVC hierarchical features. Within the system architecture, MBSs and SBSs are provisioned with differentiated computing resource pools [

29], where MBSs prioritize SVC BL tasks by reserving

of the resource pool

.

and implementing a lightweight containerized instance preloading mechanism. The cold-start latency of the base layer tasks is compressed to 5 ms to ensure the real-time requirement: the

; while the small base station focuses on the resilient processing of the enhancement layer (EL) tasks by adopting a dynamic resource allocation mechanism based on the SVC hierarchical dependency:

In the equation, denotes the computational resources allocated by base station m to user u for the th layer of video at time slot t. The numerator, , represents the bit rate of the th layer of the video. The denominator is the total bit rate of all users’ tasks at the same layer. Additionally, signifies the total computational resource capacity of base station m.

Activate high-level resource allocation only when the completion of a low-level task is detected, and introduce a dynamic fallback mechanism as shown below to prevent resource overload:

In the equation, represents the total amount of computational resources already allocated by base station m. Here, denotes the total computational resource capacity of base station m. The highest EL task refers to the video stream task with the highest level in the enhancement layer.

For bursty traffic scenarios, the model is designed with an elastic resource expansion mechanism:

Where

is the elasticity expansion coefficient,

is the hyperbolic tangent function, which is used to smooth the adjustment of the resource expansion amplitude,

represents the average queue length hole value of the system.

By dynamically adjusting the capacity of the small base station resource pool to cope with the instantaneous load surge, and at the same time, establishing a rapid response mechanism to automatically trigger the hierarchical degradation strategy when resource overload is detected to ensure system stability.

2.4. Lyapunov Optimization Model

In highly dynamic network environments, resource allocation for real-time video streaming confronts multiple challenges including rapidly fluctuating channel conditions and drastic variations in user demand [

30]. Conventional static optimization approaches struggle to adapt to these time-varying characteristics, while prediction-driven algorithms face limitations in computational complexity and forecasting accuracy. The Lyapunov optimization framework offers a comprehensive theoretical foundation for addressing this challenge - it characterizes system dynamics through virtual queue construction and converts complex long-term stochastic optimization problems into deterministic subproblems using the Drift-plus-Penalty methodology [

6]. The following analysis systematically explores the engineering implementation of this framework across three critical dimensions: virtual queue design, parameter adaptive adjustment, and parallelized execution.

2.4.1. Enhanced Analysis of Virtual Queue Design

Based on the existing virtual queue

, we further introduce a priority weight factor

to distinguish the urgency levels of different users and video layers. For example, the base layer

of real-time surveillance videos can be set as

, while the enhancement layers

are set as

, thereby reflecting differentiated processing in queue updates:

In the formula:

represents the distortion queue state of user

u’s

layer video at time slot

t ;

is the priority weight factor used to differentiate the transmission urgency of different video layers;

denotes the amount of successfully transmitted data for the

layer within time slot

indicates the cumulative distortion in video quality due to transmission failures. This equation ensures non-negative queue values through nonlinear mapping and dynamically reflects the transmission integrity of video layers. Where the task queue update follows the following equation.

In the formula: represents the task queue length of user u at time slot t; denotes the amount of data successfully transmitted for the layer through base station indicates the volume of new video tasks arriving within time slot t. This equation employs a non-negative truncation operation to ensure the physical significance of the queue and achieves temporal propagation of the queue state through the accumulation of new tasks.

This design enables high-priority tasks to be allocated higher scheduling weights during resource contention, particularly in latency-critical scenarios such as medical emergencies or industrial control systems. Furthermore, the modeling of distortion accumulation requires refinement to incorporate spatial-temporal complexity characteristics of video content-motion-intensive scenes (e.g., moving objects) should incur higher distortion penalties compared to static backgrounds to better capture QoF degradation patterns.

2.4.2. Dynamic Adjustment Mechanism for Drift Plus Penalty Optimization

The choice of parameter

V is one of the core challenges of the Lyapunov framework. Traditional static settings (e.g., fixed) are difficult to adapt to network load breaking. For this reason, adaptive

V regulation algorithm is proposed, based on Lyapunov function:

In the equation:

represents the Lyapunov function value at time slot

t;

quantifies the backlog level of the task queue;

signifies the cumulative effect of distortion in video layers. This function amplifies the penalty weight for large queue states through a quadratic term, encouraging the system to prioritize high-backlog tasks. A smaller value indicates superior system stability. The conditional drift is expressed by the following equation:

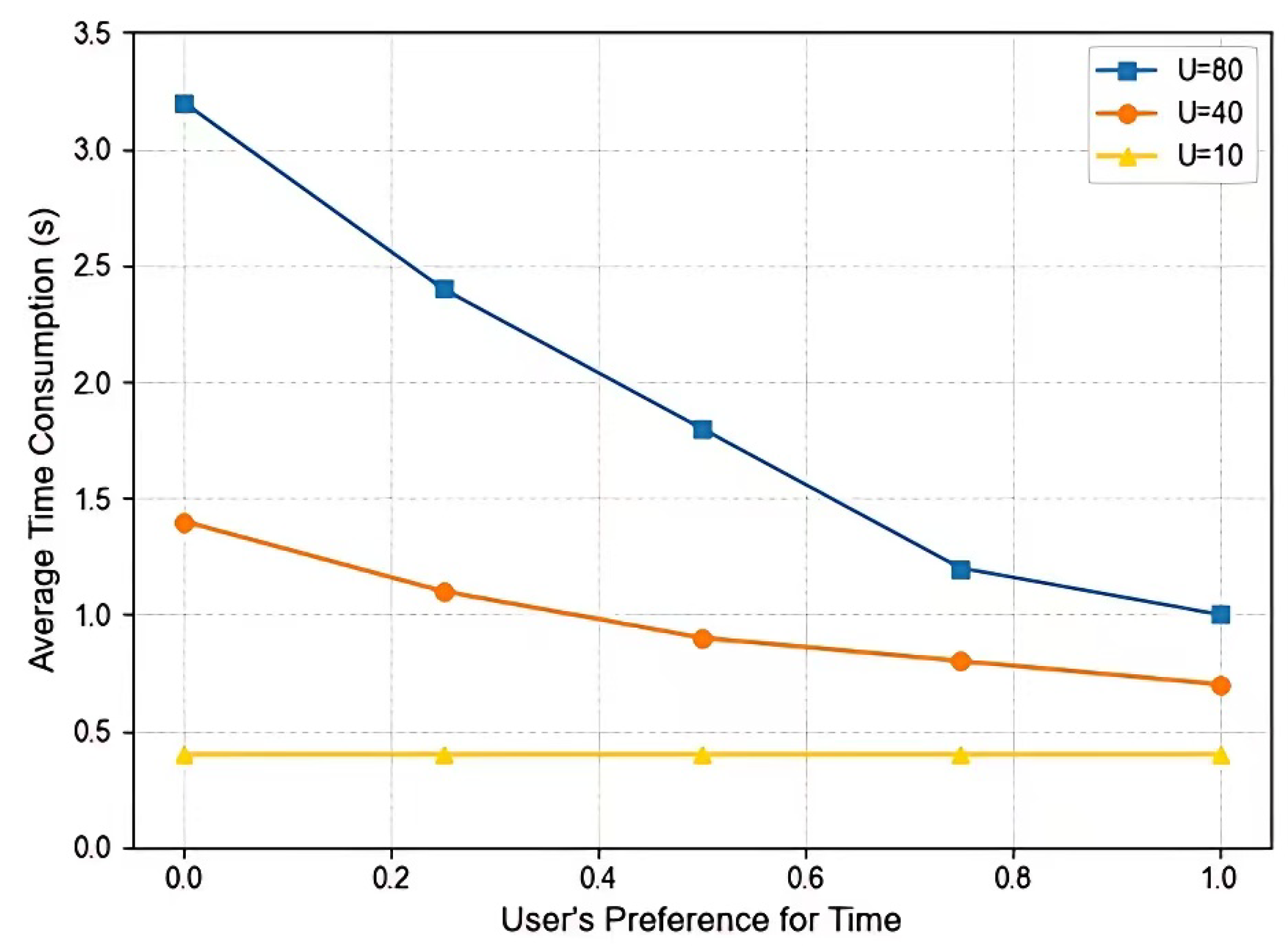

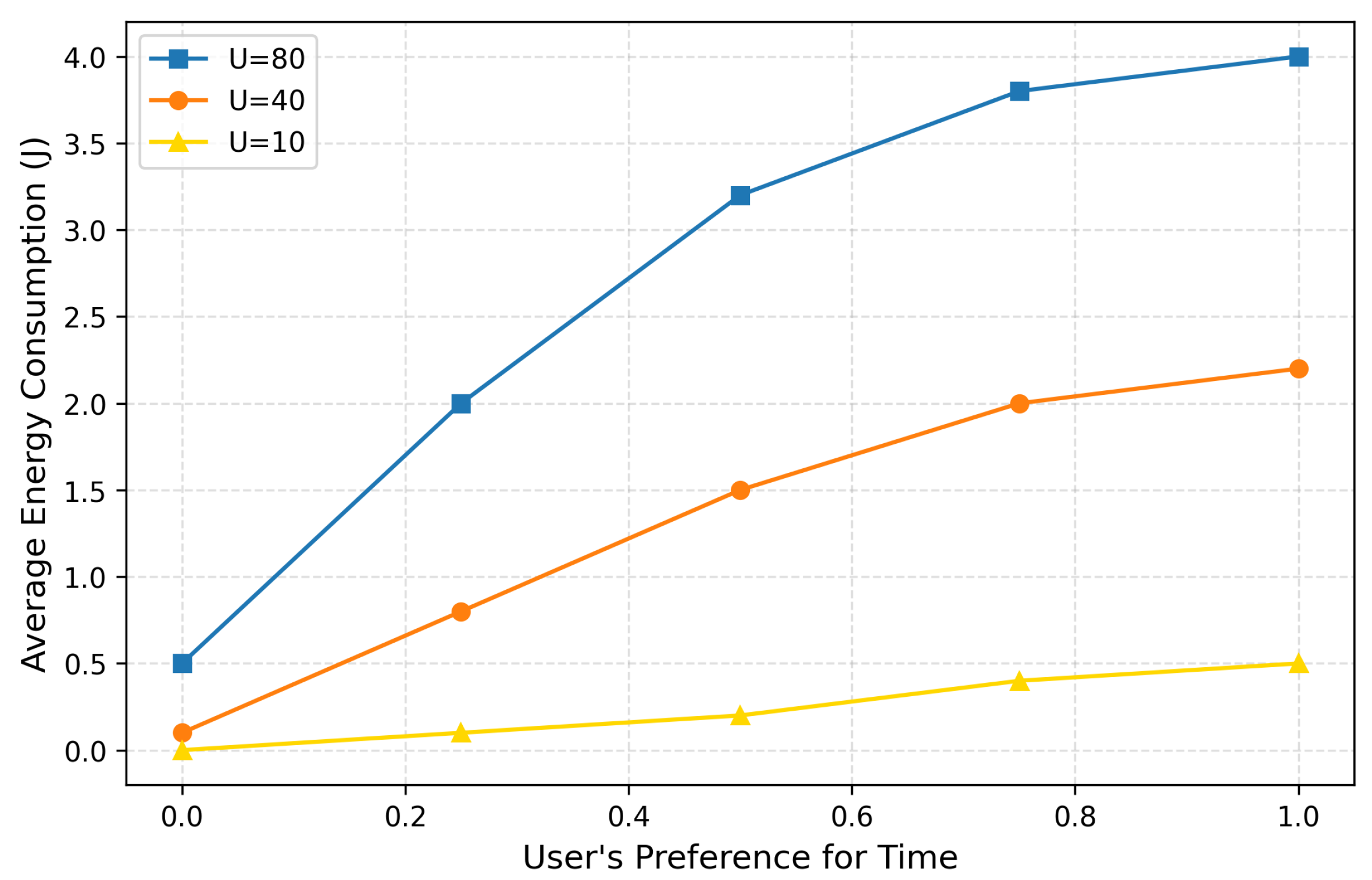

Specific adjustment strategies include: (i) Short-term adjustment: dynamically scale V based on the ratio of instantaneous queue length to distortion value. For example, when , temporarily reduce V to prioritize stabilizing the queue. (ii) Long-term learning: utilize reinforcement learning (such as DQN) to train the adjustment strategy for V, with a reward function based on long-term Quality of Experience (QoE) and delay metrics.

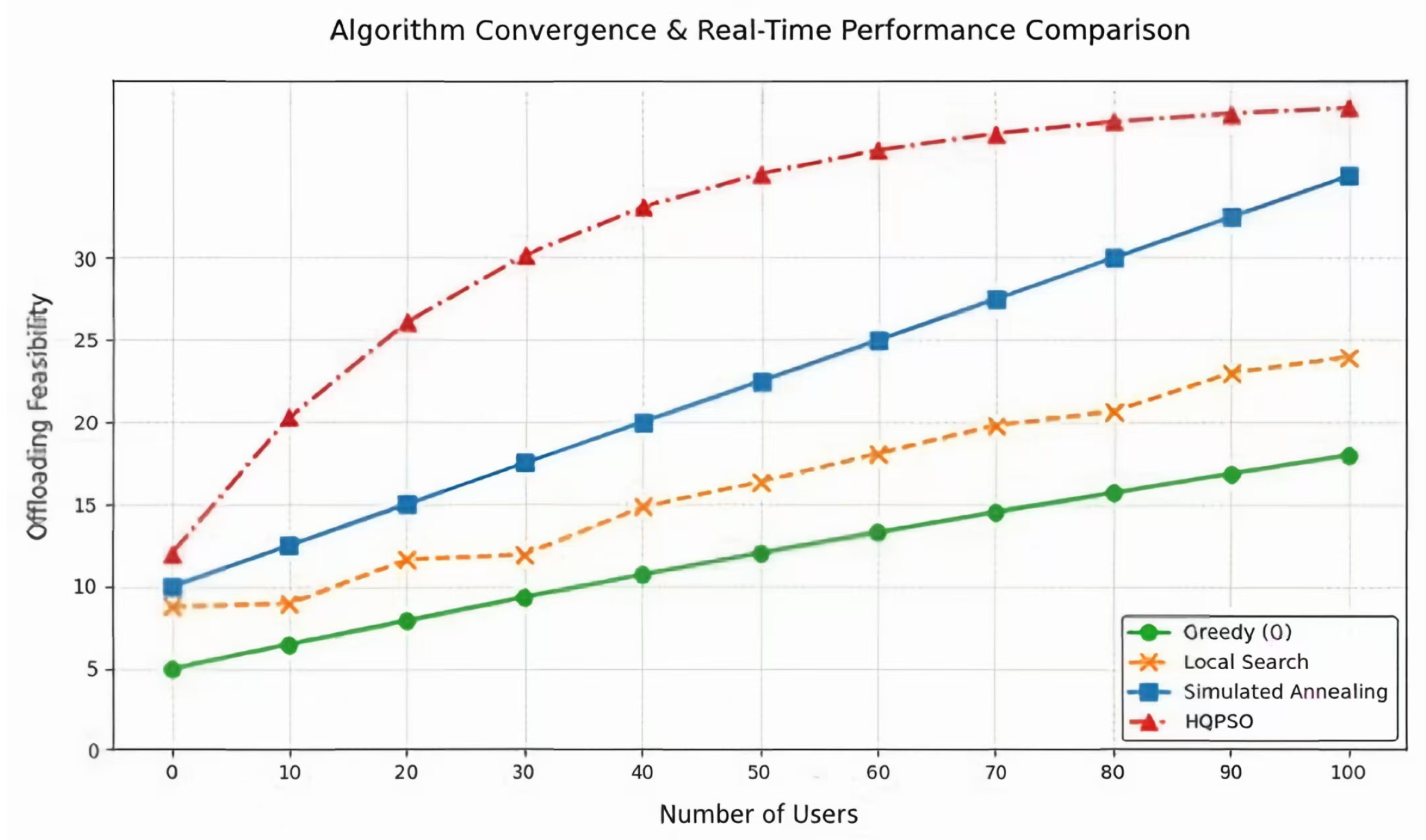

This dynamic regulation enables the system to automatically switch to low-latency mode during congested periods (such as live sports broadcasts), while enhancing video quality during network idle times (such as late at night). Experiments show that the adaptive V strategy can improve QoE by compared to fixed-value schemes.

2.5. Systematic General Computational Model

Based on the description of the modules above, it is known that in a video processing system, each user device generates different video computing tasks, which usually have different computing resource requirements

and data transmission requirements

. These tasks may be processed locally or offloaded to the MEC (Mobile Edge Computing) servers for computation over the wireless network. The system needs to make a decision on whether to offload a task based on the computing power of the device

and the network condition. To this end, the system takes into account multiple factors, including computing power, transmission delay, and network bandwidth, and makes a dynamic judgment. The core goal of offloading decision-making is to improve the overall efficiency of the system by minimizing delay and energy consumption, while ensuring the resource load balance of the system [

31]. In this context, the offloading decision is calculated by the following formula:

In the formula,

and

represent the computational capabilities of the MEC server and user devices, respectively.

denotes the data transmission delay for task

, with a threshold used to determine whether offloading the task to the MEC server would enhance performance. This decision-making process aids in determining the optimal processing method for tasks [

27], ensuring that computational tasks are completed within a reasonable timeframe while avoiding system overload due to insufficient network transmission or local computing resources.

To achieve dynamic scheduling and optimization of tasks under highly dynamic scenarios, the system employs a Lyapunov optimization framework to manage resource allocation. This framework adjusts in real-time based on changes in the task queue

, which represents the queue state of the

layer for the

type of task at time

t. The system’s objective is to adjust resource allocation according to the arrival and processing status of each task, minimizing system latency and energy consumption while ensuring balanced system load [

32]. The queue evolution within the Lyapunov optimization framework is described by the following equation:

In the formula: represents the arrival rate of tasks at time t, and denotes the processing rate of the task queue at time t. The dynamic adjustment of queue states ensures that the system can optimize resource allocation based on the current task load.

During the optimization process of resource allocation, the system aims to minimize the drift-plus-penalty function, ensuring that tasks are processed according to their priority order while avoiding excessive delays and resource wastage. This objective function is expressed by the following equation:

where

is the weight of the task and

is the drift penalty coefficient. By regulating these values, the system is able to efficiently allocate computational resources, avoiding a certain portion of resources being over-occupied and ensuring the optimization of overall performance.

The primary objective of this research is to synergistically optimize offloading decisions and resource allocation for video computing tasks in hyper-dynamic environments. Video stream processing requires ensuring both data integrity and quality while minimizing transmission and computational latency [

33]. Latency optimization constitutes a critical system design dimension, particularly for real-time video streaming applications where the system must guarantee rapid response capabilities and timely task execution [

34]. To achieve this, the system dynamically adjusts computational resource allocation through real-time monitoring of base layer (BL) and enhancement layer (EL) task latencies, thereby minimizing overall task completion time [

35]. The mathematical formulations for BL latency and EL latency are specified as Equations (

18) and (

19):

In the public center: and denote the bandwidth of the local device and the MEC server respectively, while and are the transmission demands of the base layer and the enhancement layer. The system dynamically adjusts the bandwidth allocation and optimizes the transmission path according to these demands, thus reducing the overall delay and improving the efficiency of video stream processing.

While ensuring real-time response, the system must also minimize energy consumption. This not only helps extend the life of the equipment, but also improves the overall stability of the system. During task processing, the system dynamically adjusts the energy allocation according to the use of different computing resources to ensure a balance between energy consumption and latency. The energy consumption

E can be calculated by the following formula:

In the formula, and represent the energy consumption of local devices and MEC servers, respectively. and denote the latency for local and MEC processing. By optimizing latency and energy consumption, the system can achieve more efficient resource management.

Based on the above multi-dimensional modeling, the system optimization objective is defined as maximizing the user’s comprehensive QoE under the premise of ensuring queue stability, and the system implements a dynamic resource management and scheduling framework. This framework continuously adjusts task offloading, resource allocation, load balancing, coding optimization, delay and energy management through Lyapunov optimization methods, and optimizes resource allocation based on real-time feedback. The overall model can be represented by the following comprehensive formulation:

In the formula,

represents the offloading decision set at time slot

denotes the MEC resource allocation vector;

indicates the user transmission power;

is the Lyapunov drift term, representing system stability;

V is a control parameter used to adjust the weight between Quality of Experience (QoE) and queue stability;

is the QoE penalty function. The specific meanings of the constraints in Equation (

21) are as follows: (i) Constraint

ensures that the subtasks of the same video task can only be executed locally or offloaded to one MEC server, guaranteeing a unique offloading path. (ii) Constraint

states that the total computational resources allocated by the MEC server must not exceed its current available resource limit. (iii) Constraint

requires that the transmission power of user devices must comply with the preset maximum power limit. (iV) Constraint

ensures that users receive at least the base layer data of the video stream, maintaining basic service quality. (V) Constraint

restricts the cumulative distortion of layered video transmission, ensuring overall video quality meets the standard.