1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), specifically Generative AI (GenAI), reshapes the educational landscape. In K-12 education, AI’s rapid advancement is reshaping pedagogical practices, resource management and student competencies (Limna et al., 2022; UNESCO, 2023a). The World Economic Forum (WEF) underscores the urgency of preparing students to use AI tools and critically engage with them, fostering skills to thrive in an AI-driven future (Milberg, 2024). Central to this mission is AI literacy which includes the ability to identify, understand and develop ideas, critically evaluate AI technologies and their applications, and the ethical implications thereof (Hossain, 2023, p. 1). This literacy transcends technical proficiency, encompassing ethical decision-making, contextual awareness and responsible deployment (Voulgari et al., 2022; UNESCO, 2023a). Hollands and Breazeal (2024) further stress that AI literacy fosters optimism about AI’s societal benefits, underscoring its urgency in preparing students and educators alike.

School librarians, also known as teacher-librarians and school library media specialists—historically stewards of information literacy—are uniquely positioned to lead AI literacy efforts. Their expertise in fostering digital literacy, media literacy, academic integrity and copyright literacy (Hossain, 2020; Merga, 2022) aligns with the demands of teaching AI citizenship and promoting ethical engagement with GenAI-generated content (Hossain, 2025a; Oddone et al., 2024). Yet, as AI reshapes library operations—from cataloging to personalized learning—librarians face a dual mandate: to adopt AI tools themselves and to guide students and teachers in navigating the ethical complexities of AI (IFLA, 2020; Softlink Education, 2023). While this potential exists, emerging research suggests systemic challenges, such as hesitancy to adopt AI, which may lead to gaps in librarians' AI readiness and insufficient institutional support (Huang, 2024; Chepchirchir, 2024). These barriers threaten to exacerbate global inequities in digital skills development, particularly in under-resourced regions.

With libraries becoming increasingly reliant on AI and GenAI to deliver services and manage information, the role of AI-literate librarians will only become more paramount (Cox, 2023; Hossain, 2023), with school librarians as no exception. This study fills a critical gap by understanding school librarians' AI literacy and engagement, as well as their preparedness to cultivate AI literacy in K-12 schools, ensuring that both teachers and students can critically, ethically, and effectively navigate an AI-powered world.

2. Problem Statement and Purpose

As GenAI becomes increasingly embedded in K–12 educational environments, the role of school librarians is undergoing a significant transformation (Oddone et al., 2024). Scholars such as Hossain (2025a), Hutchinson (2024) and Yi et al. (2024) have emphasized the growing responsibility of school librarians in fostering inquiry-based learning, guiding the development of essential skills such as information literacy, digital citizenship, AI literacy and AI citizenship. Globally, institutions such as the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA, 2020) advocate for libraries to lead in promoting AI literacy, emphasizing their role in democratizing access to emerging technologies. It is equally important for school librarians to be AI-ready. Hossain (2025b) and Hutchinson (2024) argue that school librarians must overcome reluctance or uncertainty surrounding AI adoption and position themselves as key facilitators in helping students and teachers navigate AI's ethical, pedagogical and technical complexities in K–12 education.

As school librarians shift from a traditional focus on information literacy to broader domains such as digital and media literacy (Bauld, 2023; Hossain et al., 2024), AI literacy emerges as the next critical frontier. As Milberg (2024) points out, it is imperative that education systems move beyond digital literacy and embrace AI literacy as a core educational priority. Despite theoretical recognition of their transformative potential, empirical insights into school librarians’ current AI literacy, practical engagement with AI tools, confidence in addressing AI-related ethical dilemmas and instructional readiness remain sparse. Understanding these dimensions is essential for informing future professional development, policy and curriculum design in K–12 aimed at empowering school library professionals in the age of GenAI. This study aims to address that gap by exploring the AI literacy and engagement of school library professionals globally, providing insight into their current practices and informing the development of professional learning and leadership.

3. Literature Review

The rapid advancement of AI, particularly GenAI tools like ChatGPT, has reshaped pedagogical practices, resource accessibility and learning paradigms in K-12 education (Limna et al., 2022). International organizations such as UNESCO (2023b) call for integrating AI competencies into national curricula to equip students for a future dominated by AI. This mirrors the WEF’s push to embed AI in education, ensuring a workforce skilled in critically engaging with evolving technologies (Milberg, 2024). The OECD (2025) further plans to introduce Media and Artificial Intelligence Literacy (MAIL) as part of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) starting in 2029, aimed at evaluating AI proficiency among youth.

Emerging studies further underscore the urgency of embedding AI literacy into educational ecosystems. Hornberger et al. (2023) and Milberg (2024) observe that students—many of whom already interact with AI tools in their daily lives—expect AI to play a central role in their future careers. Williams (2024) argues that AI literacy is a foundational skill required at all educational levels. Echoing this, Hossain (2025) advocates for educating students in AI competence to engage critically, ethically and responsibly with AI-generated content, thereby developing what he terms ‘critical AI literacy’ and ‘AI citizenship’ skills.

Several countries and organizations have developed policies and frameworks aimed at increasing citizens' AI literacy and competence, as well as addressing ethical concerns raised by AI. As of August 2024, 70 (Bangladesh developed a ‘National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence’ in 2020 which is not in the OECD list.) countries, both developed and developing, have already published their national AI policies and strategies (OECD.AI, 2021 & 2025). As a result of these national policies and strategies, AI benefits are acknowledged, and rules and frameworks are established for the safe and ethical use of AI while protecting citizens’ rights and privacy. In addition, UNESCO (2023b) developed AI competency frameworks for teachers and students in 2023, and the European Union established the first comprehensive legal framework for AI (European Commission, 2022). Several countries, including China, Finland, Portugal, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have already formally integrated AI literacy into their K-12 school curricula (UNESCO, 2022). Australia published the pioneering ‘Australian Framework for Generative AI in Schools’ to support AI use within Australian schools (Department of Education, 2023). Significantly, from the 2025-2026 school year forward, AI literacy will be a compulsory subject in the UAE for all students in K-12 (McFarland, 2025).

Studies highlight that AI can transform teaching and learning. Educators are increasingly tasked with fostering ‘AI-ready’ students—individuals equipped to use AI responsibly, understand its mechanisms and navigate ethical dilemmas (Luckin et al., 2022). Hossain et al. (2024) emphasize that teachers must ensure students are equipped to navigate AI technologies ethically and legally, thereby fostering critical and informed engagement with AI outputs. Cheng et al. (2020) found that AI has been extensively embraced across various educational institutions at multiple levels, promising to personalize learning experiences, particularly for students with special needs, thereby enhancing inclusivity and accessibility (Walter, 2024). Additionally, the use of AI can enhance learner-centered pedagogical approaches, higher-order thinking and ethical standards if used appropriately (UNESCO, 2023b).

According to Khazanchi and Khazanchi (2025), teachers must develop AI competencies in order to teach 21st-century skills. However, challenges persist, including gaps in teachers’ AI knowledge, limitations in curriculum design and the absence of clear pedagogical guidelines in K–12 (Su et al., 2023). Similarly, studies have found that non-expert educators often lack the knowledge required to understand how AI works or its implications for learning (Northeastern University & GALLUP, 2019).

Libraries, as long-standing hubs of knowledge organization and access, are also undergoing transformation due to the proliferation of GenAI. Contemporary library services now incorporate AI to streamline operations, enhance personalization and improve user experience (Cox, 2023; Goodchild et al., 2024). AI-driven systems assist in cataloguing, content recommendation, language translation and user behavior analytics, helping libraries become more inclusive and efficient (Adewojo et al., 2025; Kalbande et al., 2024). However, the successful integration of AI technologies requires more than infrastructure—it demands an advanced level of AI literacy among Library and Information Science (LIS) professionals (Cox, 2023; Goodchild et al., 2024).

This is particularly relevant for school librarians within the K-12 education system, whose roles are evolving in the digital age. The 2023 Softlink School Library Survey in Australia found that school library professionals see AI as holding significant promise, particularly in enhancing students’ critical thinking and information retrieval skills through integration into information literacy programs (Softlink Education, 2023). These findings underscore the dual challenges and opportunities AI poses for school library programs, suggesting that advancing AI literacy among school librarians may mitigate many of the emerging issues.

Nevertheless, a growing body of research has identified barriers to AI adoption within the library sector. For example, Huang (2024) found that although librarians increasingly recognize AI’s inevitability, the lack of skilled personnel impedes its effective deployment. Hossain (2023) argues that AI-literate librarians are better positioned to critically evaluate and implement AI systems, while Ali and Richardson (2025) caution that a lack of such literacy leaves professionals ill-equipped to meet evolving user expectations.

Gültekin and Ali (2025) highlight the necessity of structured training programs and institutional support to enable successful adaptation, a sentiment echoed by Chepchirchir (2024) and Cox (2023), who see librarians as emerging co-creators of AI-driven services. However, as Huang (2024) notes, inadequate training and ethical uncertainties—including concerns around misinformation, privacy and trust—continue to hinder effective adoption. To address these challenges, it is essential that school librarians develop a nuanced understanding of AI tools and applications (Hossain, 2023 & 2025b; Hutchinson, 2024; Oddone et al., 2024; Yi et al., 2024). Against this backdrop, this study explores school librarians’ AI literacy across global contexts, examining their familiarity with AI tools, professional engagement, instructional integration, technical knowledge and perceptions of ethical challenges—including academic integrity, privacy and trustworthiness.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study adopted a mixed-methods exploratory design to explore the nuances of AI literacy, readiness and professional engagement with AI technologies among school librarians worldwide. As Creswell (2017) emphasizes, mixed-methods research enhances the depth and breadth of understanding by integrating both quantitative and qualitative data. Exploratory designs are particularly well-suited for under-researched or emerging areas, allowing researchers to generate initial insights and conceptual clarity (Stebbins, 2001; Stewart, 2025).

4.2. Instrument Development and Pilot Testing

A structured questionnaire was developed using Google Forms, informed by an extensive literature review, the authors’ professional experience in teaching and school librarianship, and feedback from subject matter experts. The questionnaire employed both closed-ended—Likert scales, checkboxes, multiple-choice—and open-ended questions to capture nuanced responses from school librarians.

A pilot study was conducted with 12 school librarians (nine from international schools, two from private schools and one from a public school), as well as one LIS faculty member. Pilot feedback led to several refinements, including the clarification of key terms such as AI familiarity—defined as general awareness or recognition of AI technologies—and AI literacy, defined as a deeper understanding of AI principles, implications and the ethical application of AI tools. All relevant terms, study objectives and data privacy protocols were clearly defined for participants within the survey.

Besides demographics and background information, the survey questions were divided into five domains to explore the multidimensional nature of AI literacy among school library professionals. In addition, the survey items were mapped onto relevant learning domains, reflecting cognitive, behavioral, affective and psychomotor dimensions:

- I.

AI Familiarity and Literacy (Cognitive Domain): Participants self-rated their AI literacy and familiarity using 5-point Likert scales. Multiple-choice items were included to assess understanding of core AI concepts and functions.

- II.

Application and Usage of AI Tools (Behavioral Domain): This section examined the personal and professional use of AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Bard, Bing), indicating observable behaviors linked to technology adoption.

- III.

Instructional Confidence and Readiness (Affective Domain): Scaled items measured participants perceived confidence and readiness to explain AI concepts to students or colleagues, reflecting internal states such as values, motivation and self-efficacy.

- IV.

Instructional Practice (Psychomotor and Behavioral Domains): Items in this section explored how participants incorporate AI into information literacy instruction and other standard library practices, capturing both action-oriented implementation and pedagogical engagement.

- V.

Perceived Challenges (Cognitive and Affective Domains): An open-ended question elicited reflections on institutional, pedagogical, and ethical barriers to enhancing AI literacy. Responses were analyzed thematically to identify common cognitive insights and affective responses.

4.3. Participants and Data Collection

The survey was conducted over an extended period, initially from May to November 2024 (n = 310), to accommodate participant availability across global regions and enhance response diversity. A further nine responses were collected between January and April 2025 from school librarians in the Netherlands, following the first author's keynote presentation. This flexible, staggered approach enabled the researchers to reach a broader and more geographically diverse group of participants, including those in underrepresented educational contexts. The questionnaire was disseminated globally through multiple channels, including:

Listservs of the International Association of School Librarianship (IASL) and the IFLA School Libraries Section.

National and regional school library associations and organizations.

Social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter), Facebook and LinkedIn.

Professional networks of the research team.

No formal sampling strategy was employed; participation was entirely voluntary. In addition to a detailed data privacy and ethics statement embedded in the Google Form, the study’s purpose was briefly outlined in the email invitations and social media posts used for distribution. The survey yielded 319 responses from school librarians across more than 50 countries. Notable response rates included the United States (71), India (42), Portugal (35) and Australia (34), with additional significant contributions from Canada, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (14 each), New Zealand (10), the Netherlands (9), Germany (8), and both Hong Kong and Hungary (6 each). Fewer than five responses were recorded from all other countries. In this study, we grouped countries by continent as shown in

Table 1. Respondents represented diverse genders, grade-level responsibilities and institutional contexts, including public, private and international school systems.

4.4. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS and Google Sheets and visualized using Flourish Studio. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the closed-ended survey questions. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to summarize the distribution of responses across demographic variables and report trends. Inferential statistical tests were conducted to understand relationships and differences between variables.

Qualitative data from the open-ended responses were subjected to thematic analysis under four (4) broad categories (e.g., 1. Institutional and policy constraints; 2. Educator attitudes and knowledge gaps; 3. Time, resources and professional development needs; and 4. Student misuse and ethical challenges) aligned with the study's objectives. This process allowed for the identification of common challenges, barriers and contextual insights shared by school librarians globally.

4.5. Ethical Considerations

As independent researchers not affiliated with a university or formal research institution, we were not in a position to obtain approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or equivalent ethics committee. However, the study was conducted in full alignment with the principles outlined in the ‘European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity’ (All European Academies, 2023). We adhered to core ethical standards, including voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity and the confidentiality of respondents' data. Participants were informed about the purpose of the research, data usage policies, confidentiality measures and their right to withdraw at any stage. These measures ensure transparency, respect for participants' autonomy and the responsible handling of all collected data.

5. Findings and Analysis

5.1. Demographic Overview of the Respondents

The demographic profile of the 319 school library professionals presented in

Table 1 reflects a diverse and globally distributed sample, with the majority based in Europe (33.2%) and North America (27.6%), followed by Asia (21.9%) and Oceania (14.1%). Gender distribution is heavily skewed, with females comprising 85.6% of respondents, aligning with known trends in school librarianship, while male representation remains low (11.9%). Grade-level responsibilities are well balanced across educational stages, with the highest proportions of school librarians working in K–8 (24.8%) and high school (24.8%) settings, and a notable 21.9% covering both middle and high school. Over half of the respondents (53%) are employed in public schools, with 21.9% in international and 18.2% in private, local institutions, ensuring varied institutional contexts.

In terms of qualifications, nearly half of the participants (46.1%) hold a master’s degree in library and information science (LIS), 21.0% possess a postgraduate certificate or diploma in LIS, and an almost equal and notable minority (19.5%) —an amount nearly equal to those with postgraduate-level LIS education—lack formal credentials, reflecting a broad spectrum of academic preparation. The participants' professional experience is quite evenly distributed, with nearly equal representation across the different ranges of years of experience, particularly among those with 1–5 (20.7%), 6–10 (21.3%) and 11–15 (20.7%) years of service. This demographic spread enhances the study’s generalizability and provides rich insight into the AI literacy, readiness and engagement of a broad cross-section of school library professionals globally.

5.2. AI Literacy of School Librarians

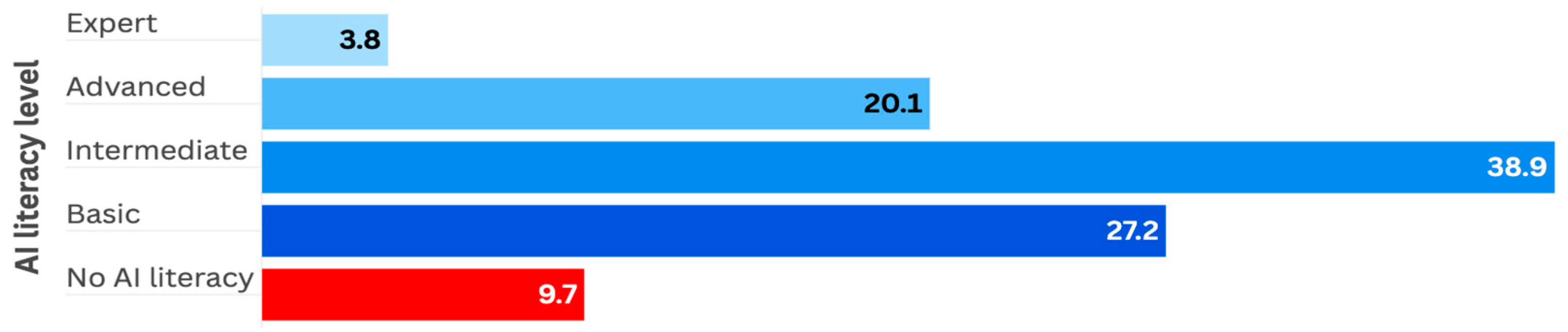

Figure 1 illustrates the self-reported AI literacy levels of school librarians, highlighting a spectrum of competency across the profession. The largest proportion of respondents (38.9%) identified as having an intermediate level of AI literacy, indicating a moderate understanding of navigating AI tools and capacity in AI literacy instruction. Over one-quarter (27.6%) reported a basic level of literacy, suggesting foundational awareness but limited application capabilities. Notably, 20.1% of school librarians considered themselves to have advanced AI literacy, reflecting strong engagement and comprehension, while only 3.8% identified as experts, pointing to a scarcity of high-level proficiency in the field. Surprisingly, 9.7% of respondents reported having no AI literacy at all. These figures suggest that while a significant portion of school librarians are beginning to engage meaningfully with AI, there remains a critical need for targeted professional development to raise overall competency and support ethical, informed integration of AI in K-12 schools' information and/or digital literacy curricula.

5.3. School Librarians' AI Literacy Based on Demographic Variables

The ANOVA test results in

Table 2 assess whether school librarians’ AI literacy levels significantly differ across various demographic variables. Of the six variables examined—location (by continent), gender, grade-level responsibility, school type, education and experience—only education demonstrated a statistically significant effect on AI literacy levels (F = 2.715, p = 0.007). This finding indicates that the level of formal education, particularly in LIS or related fields, is a critical determinant of AI literacy among school library professionals. Considering this outcome, it is noted with some trepidation that

Table 1 shows almost one-fifth of respondents do not have a formal qualification in librarianship or education.

Although the grade-level responsibility approached significance (p = 0.056), suggesting potential differences based on the grade levels served (e.g., K–8 vs. high school), it did not reach the conventional threshold. Other variables such as continent, gender, school type and years of experience showed no statistically significant differences, indicating that these factors may not substantially influence AI literacy levels in this sample. These findings emphasize the importance of formal educational qualifications in shaping school librarians’ AI readiness and highlight the need to incorporate AI literacy into pre-service and continuing LIS education to build consistent competencies across all school and library settings.

5.4. School Librarians' Conceptual and Pedagogical AI Competency

Table 3 offers insights into school librarians' conceptual and pedagogical competency in AI. A majority of respondents reported the ability to explain real-world AI applications (69.9%) and discuss ethical considerations (70.2%), highlighting a strong awareness of AI's societal role and moral implications. However, when it comes to instructional competencies, the percentages decline notably. Only 47.3% felt capable of teaching students how to use AI tools, while 45.5% indicated they could identify and discuss AI-related biases—both essential for fostering critical and ethical AI literacy and digital citizenship. Far fewer respondents could evaluate AI-powered educational tools (28.8%) or identify whether digital tools incorporate AI (31.3%), signaling a gap in technical literacy.

Similarly, only 44.8% reported confidence in guiding students through ethical AI-supported research projects. The 3.7% who selected ‘none of the above’ point to a small but notable cohort lacking any meaningful AI understanding. Overall, the findings suggest that while general awareness is fairly widespread, significant gaps remain in applied and instructional AI competencies—indicating the need for structured professional development focused on ethical, technical and pedagogical dimensions of AI competencies in school libraries.

5.5. School Librarians' Consolidated AI Competency

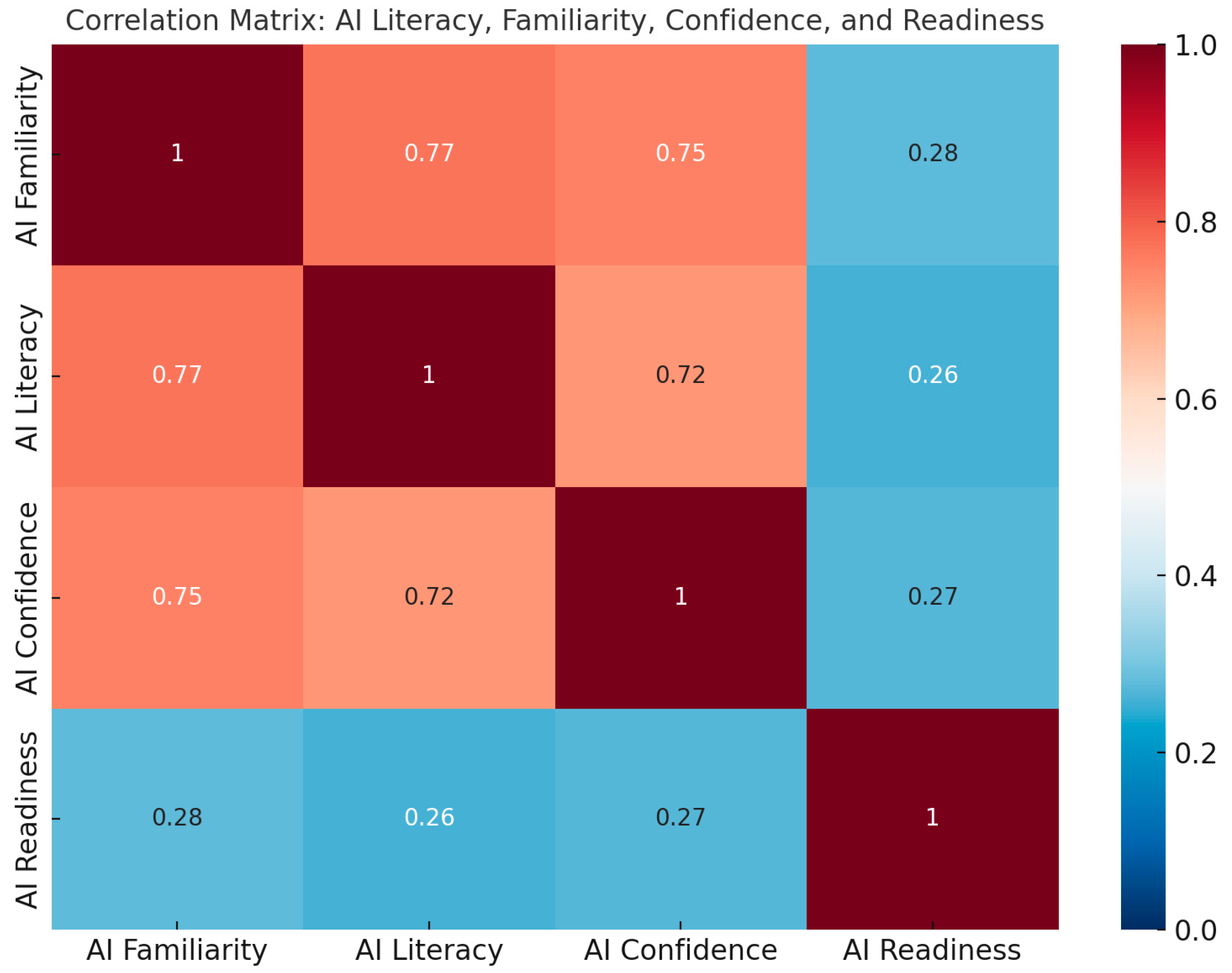

The correlation analysis illustrated in

Figure 2 revealed strong, statistically significant relationships of AI familiarity, AI literacy, AI confidence and AI readiness among school library professionals, indicating that increased exposure to AI tools is closely associated with higher conceptual understanding and confidence in using AI (r = .75 to .77, p < .01). Simply put, school librarians who are more familiar with AI tools are also more literate in AI concepts and more confident in applying AI in their roles. This aligns with Bandura’s (1977) theory of self-efficacy: repeated exposure fosters competence and assurance. These findings also support the idea that familiarity may act as a foundation for both cognitive (literacy) and affective (confidence) dimensions of AI competence. AI readiness demonstrated moderate but significant correlations with each of the other variables (r = .26 to .27, p < .01), suggesting that readiness is a multifaceted construct influenced by familiarity, knowledge and affective disposition.

The strong triad of familiarity-literacy-confidence indicates that school librarians with hands-on AI experience are better positioned to teach AI literacy. However, weak readiness correlations suggest many lack the skills to scale these efforts. For example, librarians may understand AI ethics but lack curriculum integration strategies. These findings underscore the importance of continuous, integrated professional development that simultaneously enhances school librarians’ practical exposure, conceptual literacy and confidence to foster comprehensive AI readiness in educational contexts.

5.6. School Librarians AI Engagement

The data in

Table 4 reveal that school librarians exhibit varied levels of engagement with AI tools in their professional practice. ChatGPT emerges as the most frequently used tool, with 38.4% of respondents reporting regular use, suggesting strong familiarity and confidence with conversational AI for information retrieval, content creation or instruction. Other tools such as Bing (11.2%), Perplexity AI (9.2%) and Gemini (7.4%) show moderate use, reflecting growing interest in generative search and assistant platforms. However, low usage of research-focused tools like Connected Papers, Elicit and ResearchRabbit implies limited integration of AI in academic exploration and knowledge mapping. Notably, 10.6% of librarians do not use any AI tools, which may point to gaps in digital literacy or access.

Data in

Table 5 suggests a cautious yet emerging adoption of AI tools among school librarians, accompanied by notable disparities in application. While 10.8% integrated AI into information literacy lessons and 10.6% explored AI to stay technologically updated, core library functions such as cataloging (3.4%) and usage analytics (3.1%) remain underutilized, suggesting a gap between AI’s potential and practical implementation.

The emphasis on student-facing tasks—research assistance (9.4%) and digital content creation (10.4%)—highlights librarians’ prioritization of pedagogical support over operational efficiency. However, low engagement in personalized recommendations (6.8%) and accessibility enhancements (5.3%) signals missed opportunities for inclusive, tailored services. Notably, 6.2% of respondents reported not using AI tools at all, indicating ongoing barriers, perhaps a lack of training, institutional support or awareness.

Table 6 shows that 45.2% of school librarians integrated AI literacy into their information literacy/library curriculum to some degree, though only 10.7% do so ‘extensively’ or ‘to a great deal’. A significant proportion (34.5%) engage minimally or ‘to some extent’, while 26% plan to adopt AI literacy but have not yet done so. Nearly a quarter (24.8%) do not incorporate AI literacy at all and 4.1% lack familiarity with AI tools, rejecting their use entirely. The data highlight a disparity between intent and action, with most school librarians remaining in early or inactive stages of AI literacy integration into their existing information literacy, digital literacy or library curriculum or lessons, depending upon which model each school followed.

5.7. Qualitative Insights: Challenges to Promote and/or Integrate AI Literacy (n = 121)

Based on a qualitative thematic analysis of the open-ended responses to the question about challenges in promoting AI literacy among students and colleagues, four major themes emerged from 121 valid responses:

5.7.1. Institutional and Policy Barriers

A substantial number of respondents reported systemic limitations, such as a lack of official AI policies, unclear directives and administrative resistance. Some schools have banned student use of AI or restricted access to tools due to privacy concerns or regulatory requirements.“My school district doesn't want us teaching about it until the senior admin team decides what they want to do about AI … they are still refusing to let it be taught or explored.”

Respondents also mentioned slow or inconsistent policy development, blocking of AI platforms by district IT administrators, fear of legal or ethical implications, which collectively hindered school-wide AI integration.“Our school is still figuring out its policies and procedures when it comes to AI. Without having these in place, there has been inconsistent use and messaging for and from staff.” These comments vividly illustrate why AI readiness remains stifled, despite moderate familiarity and curiosity—particularly among librarians working in public schools or regions where AI policy is underdeveloped.

5.7.2. Educator Attitudes and Knowledge Gaps

Many school librarians described a culture of skepticism, fear or resistance among teaching colleagues.“Most staff still view AI as something the students cheat with … Teachers of Digital Technologies are more on board with using it.” According to school librarians, some educators view AI solely as a cheating tool and prefer punitive measures instead of instructional support. Others avoid the topic altogether, fearing that discussion may encourage misuse. “Many educators are in the 'gotcha' mindset … Reality is that educators need to embrace AI in their teaching and alter their age-old assignments.”

This mistrust is often compounded by a lack of training, ability to pedagogically integrate new tools/platforms, or a perception that AI literacy falls outside their teaching responsibility. This aligns with the relatively low percentages (around 13%–20%) of respondents who felt confident teaching AI or discussing its ethical implications (see

Table 3). The quantitative findings underscore that even among tech-savvy educators, AI integration remains pedagogically underdeveloped, or many teachers have not been provided with time or training to embed AI into their teaching.

5.7.3. Time, Resources and Professional Development Needs

Respondents repeatedly cited limited time, lack of instructional materials and minimal training opportunities as critical barriers. Many noted being part-time or overburdened, with little capacity to explore new tools or conduct workshops. “Time. I don't have enough time to reach all students and staff and continue to explore new AI tools.” While interest in AI literacy is growing, school librarians struggle to prioritize its integration amid competing responsibilities, staffing constraints or a lack of district-level support. “My school is not ready and has not taken the time to teach staff about AI … PD on AI would be amazing.” Similarly, another survey participant indicated, “State laws regarding student data privacy limit access to use of approved apps, staff is [are] nervous about being the first to use with students but will use AI apps personally to create lesson content.”

These responses directly align with moderate correlations observed in the quantitative data between AI familiarity and confidence (r = .749**), suggesting that professional development can help build competence, but that structural constraints may be limiting uptake.

5.7.4. Student Misuse and Ethical Dilemmas

Several school librarians highlighted the difficulty of managing academic integrity in the age of AI, with students frequently using AI tools to complete assignments with minimal oversight. “Students always overuse and misuse AI-related tools … It has been much more challenging for teachers to maintain academic integrity.” while others lamented “Despite clear explanations … middle school students copy/paste without acknowledging the AI tool.” Another participant shared “The problem with teaching ‘ethical use’ of AI is that the students who we are trying to educate SIMPLY DO NOT CARE ABOUT ETHICAL USE… []”. In addition, A third participant expressed concern, saying: “The biggest challenge is that they really just want to play with the tools, they don't fully understand the big picture or ethical concerns, which I think is critical.”

This theme complements the low self-reported ability to evaluate AI tools and guide ethical research practices (

Table 3: ~8%–13%), reinforcing a need for both pedagogical strategies and institutional support. Many educators find it difficult to detect AI-generated content, creating tension between enforcement and instruction. Others noted a lack of student understanding about responsible AI use, calling for structured digital and AI citizenship education that emphasizes critical thinking, ethical considerations and authenticity (Hossain, 2025a; Merga, 2022).

6. Discussion and Implications

This study presents one of the first large-scale, cross-continental examinations of school librarians' AI literacy, readiness and engagement with AI tools, shedding light on the evolving role of school library professionals in an increasingly AI-integrated K-12 educational landscape. The findings reveal that while many school librarians demonstrate moderate familiarity and confidence in using AI tools—especially widely accessible platforms such as ChatGPT—their readiness to implement AI in teaching remains limited. This readiness gap echoes concerns in prior literature (Huang, 2024; Chepchirchir, 2024) and reinforces the claim that technical awareness does not necessarily translate into pedagogical integration or leadership in AI literacy. As Hossain (2025b) and Oddone et al. (2024) assert, the shift from digital to AI literacy requires not only awareness but also structured professional support and leadership cultivation.

The statistically significant correlations among AI familiarity, literacy, confidence and readiness suggest a mutually reinforcing relationship, highlighting that investment in one dimension could catalyze improvements in others. However, the relatively low percentages of school librarians using AI tools for instructional planning, collaboration or student engagement suggest structural limitations such as a lack of clear policy, inadequate training and uncertainty around ethical AI use. This finding aligns with challenges identified by Su et al. (2023) and Chepchirchir (2024), including gaps in curriculum design, the absence of guidance frameworks (Hossain, 2025a) and teacher reluctance (Hutchinson, 2024). Additionally, these patterns are substantiated by qualitative data, which reveal widespread concerns about institutional resistance, time constraints, lack of professional development opportunities and the complexities of guiding students in the ethical use of AI.

Importantly, the ANOVA results indicate that formal education, particularly qualifications in LIS, is the only demographic factor that significantly influences AI literacy. This underscores the need to embed AI competencies—both technical and ethical—into LIS education and ongoing professional development programs. Thematic analysis also revealed that librarians are often expected to lead AI-related conversations and initiatives without institutional backing, resulting in professional frustration and uneven adoption. As one respondent reflected, "I offer lessons but not everyone takes me up on that offer … admin does not allow time for me to teach the teachers." Ultimately, the findings affirm the role of school librarians—not just as resource facilitators—but as ethical AI stewards in K-12 education. However, this vision will remain aspirational unless supported by robust institutional mandates, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and targeted professional learning ecosystems.

The incorporation of learning domains into the research design offers a valuable lens through which to interpret the findings. AI Familiarity and Literacy (cognitive domain), AI Tool Usage (behavioral), Instructional Readiness (affective), and Instructional Practice (psychomotor and behavioral) reflect interdependent yet unevenly developed areas of AI preparedness among school librarians. The statistically significant correlations between AI familiarity, literacy and confidence suggest a strong interrelationship between cognitive and affective domains, supporting Bandura’s (1977) self-efficacy theory. However, the weaker link between these domains and actual instructional practice indicates a bottleneck in the psychomotor domain—where knowledge and motivation are not yet translating into regular pedagogical integration.

Moreover, ethical concerns (“Will I/student use AI responsibly?”) surfaced as a distinct barrier, decoupling technical confidence from implementation intent. We therefore recommend extending self-efficacy models to include an “ethical efficacy” dimension—capturing confidence in applying AI responsibly—to more accurately predict which educators will move from experimentation to sustained, value-aligned adoption. This nuance is especially critical in the context of AI’s ethical risks, including misinformation, privacy and bias.

The qualitative findings reinforce these conclusions. Institutional barriers, lack of policies and time constraints obstruct behavioral and psychomotor application; educator mistrust and fear inhibit affective engagement; and inconsistent training affects cognitive growth. These intersecting barriers point to the need for systemic solutions. First, system-level policy reform (governments, LIS institutions, education departments and library organizations) is required to mainstream AI literacy into professional standards for school librarians. Global and national library associations and education departments must advocate for integrating AI competencies into job descriptions, professional evaluation metrics and school-level expectations. Second, institutional investment in targeted professional development is essential. This includes not just access to tools, but opportunities for critical reflection, scenario-based training and ethical case studies tailored to the school library context.

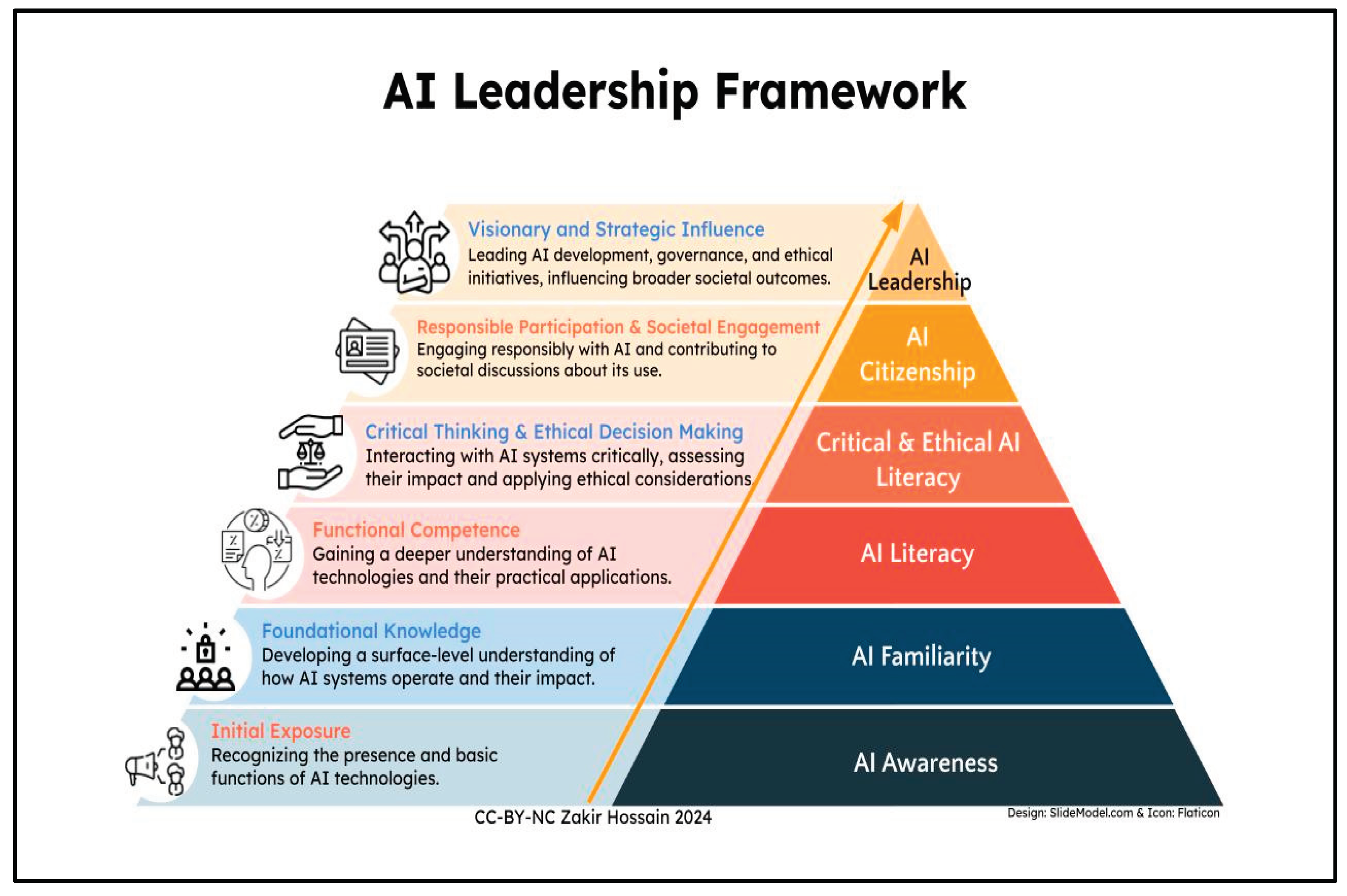

To this end, we propose the adoption of the AI Leadership Framework (Hossain, 2025b), which —though only recommended here—maps well onto these learning domains, guiding progression from foundational awareness to professional autonomy in AI use. We propose its adoption as a conceptual and practical guide to scaffold professional learning, institutional policy and librarian-led AI instruction.

Figure 3

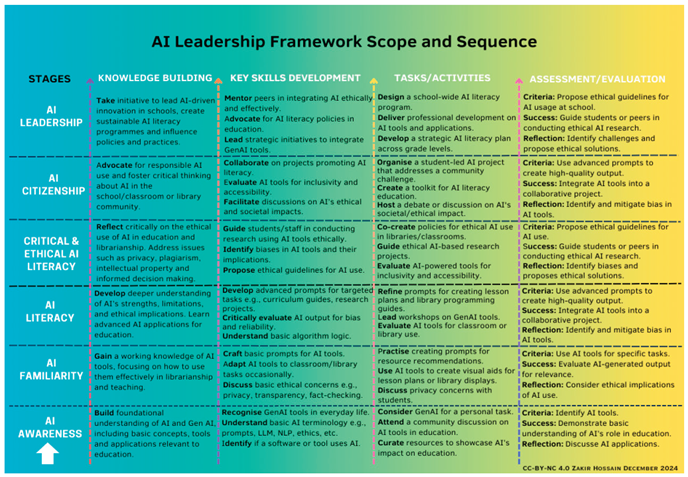

The framework emphasizes using a scope-and-sequence framework (see

Table 6) to professional learning that addresses foundational familiarity, ethical literacy, instructional integration and AI-driven innovation. It is designed to equip school librarians and teacher librarians not just as competent users but as critical AI leaders who can support student learning, guide teachers and contribute to school-wide AI integration.

Table 7

7. Conclusions

This study provides timely and critical insights into the global landscape of school librarians’ AI literacy and professional engagement with AI technologies. Drawing on the perspectives of 319 school library professionals from over 50 countries, the findings illuminate both strengths and areas for growth in the professions and preparedness to navigate the evolving demands of AI in K–12 education. While many respondents demonstrated moderate familiarity and literacy, their pedagogical integration of AI and instructional confidence and readiness remains inconsistent—highlighting the need for more structured, accessible and context-specific support. Although this study does not formally validate the AI Leadership Framework, it recommends it as a promising guide for shaping school librarians’ professional growth.

This study, however, has several limitations. Firstly, as independent researchers, we did not have IRB oversight, although we strictly adhered to the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. Secondly, the use of self-reported data may reflect subjective perceptions rather than actual competencies, and the non-random, purposive sampling limits the generalizability of results. Additionally, regional disparities in response rates may under-represent the experiences of school librarians in lower-resourced or non-English-speaking contexts. Future studies could adopt longitudinal designs and more balanced geographical representation to measure changes in AI literacy over time, incorporate direct assessments of AI competencies and explore institutional and policy-level factors influencing AI adoption in school libraries. Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable foundation for research, policy and practice—highlighting the urgent need to equip school library professionals with the tools, knowledge and confidence required to lead AI literacy efforts in their communities.

In conclusion, the findings reveal both notable progress and persistent disparities in AI readiness across regions and institutional contexts. Without coordinated action among LIS schools, professional associations and K-12 systems, AI literacy will remain uneven, further entrenching digital divides. As stewards of information and champions of ethical technology use, school librarians must be strategically empowered to lead the next generation of AI-ready learners. A unified advocacy effort—calling for mandatory AI competency standards, securing dedicated professional learning funds and forging policy partnerships—can underpin the mandates and resources school library professionals need to guide students safely, responsibly and innovatively into an AI-enhanced digital future.

References

- Adewojo, A.A.; Amzat, O.B.; Abiola, H.S. AI-powered libraries: enhancing user experience and efficiency in Nigerian knowledge repositories. Libr. Hi Tech News 2025, 42, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI in Education. (2023). AI’s role in the education revolution: discover, engage, transform. Ai-In-Education.co.uk. https://www.ai-in-education.co.uk/.

- Ali, M.Y.; Richardson, J. AI literacy guidelines and policies for academic libraries: A scoping review. IFLA J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All European Academies (ALLEA). (2023). The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. https://allea.org/code-of-conduct/.

- Bauld, A. (2023, August 21). Librarians Can Play a Key Role Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Schools. School Library Journal. https://www.slj.com/story/Librarians-Can-Play-a-Key-Role-Implementing-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Schools.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://educational-innovation.sydney.edu.au/news/pdfs/Bandura%201977.pdf.

- Cheng, X.; Sun, J.; Zarifis, A. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in educational technology research and practice. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepchirchir, S. (2024). Integrating Artificial Intelligence Literacy in Library and Information Science Training in Kenyan Academic Institutions. Karatina University Institutional Repository. https://karuspace.karu.ac.ke/handle/20.500.12092/3201.

- Cox, A. (2023). Developing a library strategic response to Artificial Intelligence. IFLA. https://www.ifla.org/g/ai/developing-a-library-strategic-response-to-artificial-intelligenc.

- Crabtree, M. (2023, August 8). What is AI Literacy? A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners. DataCamp. https://www.datacamp.com/blog/what-is-ai-literacy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-beginners.

- Creswell, J. W. , & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications. https://www.ucg.ac.me/skladiste/blog_609332/objava_105202/fajlovi/Creswell.pdf.

- Department of Education. (2024). Australian Framework for Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Schools. Department of Education, Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/schooling/resources/australian-framework-generative-artificial-intelligence-ai-schools.

- European Commission. (2024, April 23). AI Act. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai.

- Goodchild, L. , Mulligan, A., & Mensell, N. (2024). Insights: librarian attitudes toward AI. Elsevier. https://elsevier.widen.net/s/2jcbgwxsnn/librarian_key_findings_attiutudes_to_ai_report_2024. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gültekin, V.; Kavak, A. An assessment of artificial intelligence anxieties of academic librarians in Türkiye. J. Acad. Libr. 2025, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, F.; Breazeal, C. Establishing AI Literacy before Adopting AI. Sci. Teach. 2024, 91, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, M.; Bewersdorff, A.; Nerdel, C. What do university students know about Artificial Intelligence? Development and validation of an AI literacy test. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z. (2020). Connecting policy to practice: How do literature, standards and guidelines inform our understanding of the role of school library professionals in cultivating an academic integrity culture?. Synergy, 18(1). http://slav.vic.edu.au/index.php/Synergy/article/view/373.

- Hossain, Z. (2023). Unlocking tomorrow's potential by integrating AI literacy into school curriculum: ICS initiatives and future directions. Connections-The ICS School Magazine 2(33), 16-19. https://issuu.com/inter-community-school-zurich/docs/ics_autumn_connections_2023/1. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, Z.; Çelik, Ö.; Hertel, C. Academic integrity and copyright literacy policy and instruction in K-12 schools: a global study from the perspective of school library professionals. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2024, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z. School librarians developing AI literacy for an AI-driven future: leveraging the AI Citizenship Framework with scope and sequence. Libr. Hi Tech News 2025, 42, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z. (2025b). AI Leadership Framework: Advancing Australian school library professionals’ AI literacy and leadership competence. Connection, 132(1). 1-5. https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-132/ai-leadership-framework-advancing-australian-school-library-professionals-ai-literacy-and-leadership-competence/.

- Huang, Y.-H. Exploring the implementation of artificial intelligence applications among academic libraries in Taiwan. Libr. Hi Tech 2024, 42, 885–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, E. Navigating tomorrow's classroom. J. Inf. Lit. 2024, 18, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFLA. (2020). IFLA statement on libraries and artificial intelligence. IFLA.org (IFLA FAIFE Committee on Freedom of Access to Information and Freedom of Expression). https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/1646.

- Kalbande, D.; Suradkar, P.; Chavan, S.; Verma, M.K.; Yuvaraj, M. Artificial Intelligence Integration in Academic Libraries: Perspectives of LIS Professionals in India. Ser. Libr. 2024, 85, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanchi, P. , & Khazanchi, R. (2025). Role of Stakeholders in Improving AI Competencies in K-12 Classrooms. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 736-742). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/225589/.

- Limna, P. , Jakwatanatham, S., Siripipattanakul, S., Kaewpuang, P., & Sriboonruang, P. (2022). A review of artificial intelligence (AI) in education during the digital era. Advance Knowledge for Executives, 1(1), 1-9. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4160798.

- Luckin, R.; Cukurova, M.; Kent, C.; du Boulay, B. Empowering educators to be AI-ready. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, A. (2025, May 5). UAE Makes AI Classes Mandatory from Kindergarten—The World Needs to Follow. Unite.AI. https://www.unite.ai/uae-makes-ai-classes-mandatory-from-kindergarten-the-world-needs-to-follow/.

- Merga, M.K. School Libraries Supporting Literacy and Wellbeing; Facet Publishing: London, United Kingdom, 2022; Available online: https://www.facetpublishing.co.uk/resources/pdfs/chapters/9781783305841.pdf.

- Milberg, T. (2024, April 28). The future of learning: AI is revolutionizing education 4.0. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/04/future-learning-ai-revolutionizing-education-4-0/.

- Northeastern University & GALLUP. (2019). Facing the future: U.S., U.K. Northeastern University & GALLUP. (2019). Facing the future: U.S., U.K. and Canadian citizens call for a unified skills strategy for the AI age. https://uwm.edu/csi/wp-content/uploads/sites/450/2020/10/Facing_the_Future_US_UK_and_Canadian_citizens_call_for_a_unified_skills_strategy_for_the_AI_age.pdf.

- OECD.AI. (2021). National AI policies & strategies. OECD.AI. https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/overview.

- OECD. (2025). PISA 2029 Media and Artificial Intelligence Literacy. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/about/projects/pisa-2029-media-and-artificial-intelligence-literacy.

- Oddone, K.; Garrison, K.; Gagen-Spriggs, K. Navigating Generative AI: The Teacher Librarian's Role in Cultivating Ethical and Critical Practices. J. Aust. Libr. Inf. Assoc. 2024, 73, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Softlink Education. (2024, ). Australian libraries share: the impact of AI on school libraries. Softlinkint.com. https://www.softlinkint.com/blog/australian-school-libraries-share-the-impact-of-ai-on-school-libraries/.

- Stebbins, R.A. Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences; Sage Publications: 2001; Volume 48. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L. (2025). Exploratory Research: Definition, How To Conduct & Examples. ATLAS.ti. https://atlasti.com/research-hub/exploratory-research.

- Su, J.; Ng, D.T.K.; Chu, S.K.W. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Literacy in Early Childhood Education: The Challenges and Opportunities. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2022). K-12 AI curricula: a mapping of government-endorsed AI curricula. UNESDOC Digital Library. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380602.

- UNESCO. (2023a). Education in the age of artificial intelligence. UNESCO. https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/education-age-artificial-intelligence.

- UNESCO. (2023b). International forum on AI and education: steering AI to empower teachers and transform teaching. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386162/PDF/386162eng.pdf.

- Voulgari, I. , Stouraitis, E., Camilleri, V. and Karpouzis, K. (2022). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Education and Literacy: Teacher Training for Primary and Secondary Education Teachers. In: Handbook of Research on Integrating ICTs in STEAM Education, IGI Global, 1-21. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-education-and-literacy/304839.

- Walter, Y. Embracing the future of Artificial Intelligence in the classroom: the relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. (2024). Impact. AI: Democratizing AI through K-12 Artificial Intelligence Education (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)). https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/153676.

- Yi, K.; Turner, R.; Syn, S.Y.; Williams, M.; Hardin, A.; Long, T. A Feasibility Study of AI-Generated Resources for K-12 Information Literacy. Proc. ALISE Annu. Conf. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).