Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

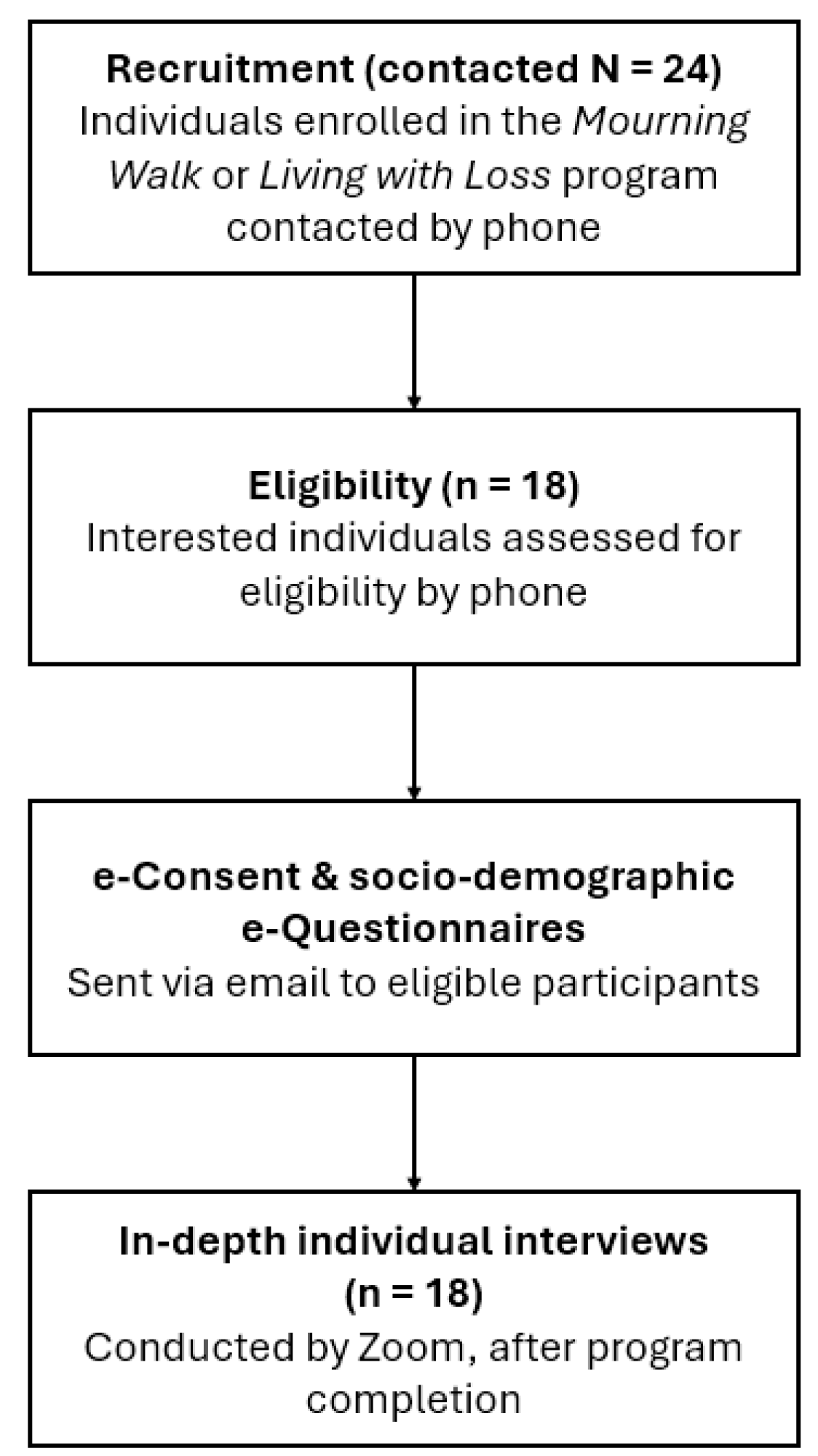

2.1. Participants, Setting, Design and Procedures

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Socio-Demographic e-Questionnaires

2.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Theme 1. Program Structure According to Grief Timeline

3.2.2. Theme 2. Flexibility in the Choice of Topics and Impact on Grief Experiences

3.2.3. Theme 3. Grief Support Dynamics in Relation to Group Composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molassiotis, A.; Wang, M. Understanding and Supporting Informal Cancer Caregivers. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2022, 23, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perak, K.; McDonald, F.E.J.; Conti, J.; Yao, Y.S.; Skrabal Ross, X. Family Adjustment and Resilience after a Parental Cancer Diagnosis. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, M.D.; Wilson-Genderson, M.; Siminoff, L.A. Cancer Patient and Caregiver Communication about Economic Concerns and the Effect on Patient and Caregiver Partners’ Perceptions of Family Functioning. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2024, 18, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erker, C.; Yan, K.; Zhang, L.; Bingen, K.; Flynn, K.E.; Panepinto, J. Impact of Pediatric Cancer on Family Relationships. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Roij, J.; Brom, L.; Youssef-El Soud, M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.; Raijmakers, N.J.H. Social Consequences of Advanced Cancer in Patients and Their Informal Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, T.; Chapman, M.V.; de Saxe Zerden, L.; Sharma, A.; Chen, D.-G.; Song, L. Correlates of Illness Uncertainty in Cancer Survivors and Family Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, N.C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, L.; Lu, G.; Lu, Q. Guilt among Husband Caregivers of Chinese Women with Breast Cancer: The Roles of Male Gender-Role Norm, Caregiving Burden and Coping Processes. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 2018, 27, e12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrop, E.; Morgan, F.; Byrne, A.; Nelson, A. “It Still Haunts Me Whether We Did the Right Thing”: A Qualitative Analysis of Free Text Survey Data on the Bereavement Experiences and Support Needs of Family Caregivers. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, L.; Goss, S.; Sivell, S.; Selman, L.E.; Harrop, E. “I Have Never Felt so Alone and Vulnerable” – A Qualitative Study of Bereaved People’s Experiences of End-of-Life Cancer Care during the Covid-19 Pandemic. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaqi, Q.; Riguzzi, M.; Blum, D.; Peng-Keller, S.; Lorch, A.; Naef, R. End-of-Life and Bereavement Support to Families in Cancer Care: A Cross-Sectional Survey with Bereaved Family Members. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loiselle, C.G. Now, More than Ever, Timing Is Right for Oncology Nurses to Champion, Co-Design, and Promote Value-Based and Strengths-Based Cancer Care! Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2023, 33, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Madsen, R.; Larsen, P.; Fiala Carlsen, A.M.; Marcussen, J. Nursing Care and Nurses’ Understandings of Grief and Bereavement among Patients and Families during Cancer Illness and Death – A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 62, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Carver, C.S.; Cannady, R.S. Bereaved Family Cancer Caregivers’ Unmet Needs: Measure Development and Validation. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2019, 54, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronsema, A.; Theißen, T.; Oechsle, K.; Wikert, J.; Escherich, G.; Rutkowski, S.; Bokemeyer, C.; Ullrich, A. Looking Back: Identifying Supportive Care and Unmet Needs of Parents of Children Receiving Specialist Paediatric Palliative Care from the Bereavement Perspective. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kustanti, C.Y.; Chu, H.; Kang, X.L.; Huang, T.-W.; Jen, H.-J.; Liu, D.; Shen Hsiao, S.-T.; Chou, K.-R. Prevalence of Grief Disorders in Bereaved Families of Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zordan, R.D.; Bell, M.L.; Price, M.; Remedios, C.; Lobb, E.; Hall, C.; Hudson, P. Long-Term Prevalence and Predictors of Prolonged Grief Disorder amongst Bereaved Cancer Caregivers: A Cohort Study. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.M.; Breen, L.J.; White, I.; Rumbold, B.; Kellehear, A. What Sources of Bereavement Support Are Perceived Helpful by Bereaved People and Why? Empirical Evidence for the Compassionate Communities Approach. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthal, W.G.; Roberts, K.E.; Donovan, L.A.; Breen, L.J.; Aoun, S.M.; Connor, S.R.; Rosa, W.E. Investing in Bereavement Care as a Public Health Priority. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e270–e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciatore, J.; Thieleman, K.; Fretts, R.; Jackson, L.B. What Is Good Grief Support? Exploring the Actors and Actions in Social Support after Traumatic Grief. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chan, J.S.M.; Chow, A.Y.M.; Yuen, L.P.; Chan, C.L.W. From Body to Mind and Spirit: Qigong Exercise for Bereaved Persons with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome-Like Illness. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 631410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsom, C.; Schut, H.; Stroebe, M.S.; Wilson, S.; Birrell, J.; Moerbeek, M.; Eisma, M.C. Effectiveness of Bereavement Counselling through a Community-based Organization: A Naturalistic, Controlled Trial. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, O1512–O1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenferink, L.; de Keijser, J.; Eisma, M.; Smid, G.; Boelen, P. Online Cognitive–Behavioural Therapy for Traumatically Bereaved People: Study Protocol for a Randomised Waitlist-Controlled Trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerome, H.; Smith, K.V.; Shaw, E.J.; Szydlowski, S.; Barker, C.; Pistrang, N.; Thompson, E.H. Effectiveness of a Cancer Bereavement Therapeutic Group. J. Loss Trauma 2019, 23, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthal, W.G.; Catarozoli, C.; Masterson, M.; Slivjak, E.; Schofield, E.; Roberts, K.E.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Wiener, L.; Prigerson, H.G.; Kissane, D.W.; Li, Y.; Breitbart, W. An Open Trial of Meaning-Centered Grief Therapy: Rationale and Preliminary Evaluation. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartone, P.T.; Bartone, J.V.; Violanti, J.M.; Gileno, Z.M. Peer Support Services for Bereaved Survivors: A Systematic Review. OMEGA - J. Death Dying 2019, 80, 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, A.L.; Hill, M.; Pazder, R.; Feudtner, C. Bereavement Care Interventions: A Systematic Review. BMC Palliat. Care 2004, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope & Cope | Supporting people with cancer; Hope & Cope. https://hopeandcope.ca/ (accessed 2025-03-23).

- Mourning Walk; Hope & Cope. Available online: https://hopeandcope.ca/program/mourning-walk/ (accessed 2025-03-23).

- Living with Loss; Hope & Cope. Available online: https://hopeandcope.ca/program/living-with-loss/ (accessed 2025-03-23).

- Allison, K.R.; Patterson, P.; Guilbert, D.; Noke, M.; Husson, O. Logging On, Reaching Out, and Getting By: A Review of Self-Reported Psychosocial Impacts of Online Peer Support for People Impacted by Cancer. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact 2021, 5, 95:1–95:35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, G.; Beight, L.; Morris, S.E.; Wolfe, J.; Snaman, J.M. One Size Doesn’t Fit All in Early Pediatric Oncology Bereavement Support. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2022, 63, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, P.; McDonald, F.E.J.; Kelly-Dalgety, E.; Lavorgna, B.; Jones, B.L.; Sidis, A.E.; Powell, T. Development and Evaluation of the Good Grief Program for Young People Bereaved by Familial Cancer. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrop, E.; Morgan, F.; Longo, M.; Semedo, L.; Fitzgibbon, J.; Pickett, S.; Scott, H.; Seddon, K.; Sivell, S.; Nelson, A.; Byrne, A. The Impacts and Effectiveness of Support for People Bereaved through Advanced Illness: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More than Just Convenient: The Scientific Merits of Homogeneous Convenience Samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 29.0).

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of Healthcare Interventions: An Overview of Reviews and Development of a Theoretical Framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; and Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K.; Neergaard, M.A.; Jensen, A.B.; Vedsted, P.; Bro, F.; Guldin, M.-B. Predictors of Complicated Grief and Depression in Bereaved Caregivers: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2017, 53, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrower, C.; Barrie, C.; Baxter, S.; Bloom, M.; Borja, M.C.; Butters, A.; Dudgeon, D.; Haque, A.; Lee, S.; Mahmood, I.; Mirhosseini, M.; Mirza, R.M.; Murzin, K.; Ankita, A.; Skantharajah, N.; Vadeboncoeur, C.; Wan, A.; Klinger, C.A. Interventions for Grieving and Bereaved Informal Caregivers: A Scoping Review of the Canadian Literature. J. Palliat. Care 2023, 38, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasdenteufel, M.; Quintard, B. Psychosocial Factors Affecting the Bereavement Experience of Relatives of Palliative-Stage Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilberdink, C.E.; Ghainder, K.; Dubanchet, A.; Hinton, D.; Djelantik, A.A.A.M.J.; Hall, B.J.; Bui, E. Bereavement Issues and Prolonged Grief Disorder: A Global Perspective. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Näppä, U.; Björkman-Randström, K. Experiences of Participation in Bereavement Groups from Significant Others’ Perspectives; a Qualitative Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petursdottir, A.B.; Thorsteinsson, H.S. Evaluating the Effect of Participation in Bereavement Support Groups on Perceived Mental Well-Being and Grief Reactions. OMEGA - J. Death Dying 2024, 00302228241253363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.; Pond, D.R. Do Online Support Groups for Grief Benefit the Bereaved? Systematic Review of the Quantitative and Qualitative Literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 100, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näppä, U.; Lundgren, A.-B.; Axelsson, B. The Effect of Bereavement Groups on Grief, Anxiety, and Depression - a Controlled, Prospective Intervention Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maass, U.; Hofmann, L.; Perlinger, J.; Wagner, B. Effects of Bereavement Groups–a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying; Routledge: London, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiselle, C.G.; Brown, T.L. Increasing Access to Psychosocial Oncology Services Means Becoming More Person-Centered and Situation-Responsive. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5601–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, N.; McKenzie, K.; Spence, D.; Lane, K.; Ugalde, A. The Experience of Bereaved Cancer Carers in Rural and Regional Areas: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Potential of Peer Support. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0293724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaman, J.M.; Mazzola, E.; Helton, G.; Feifer, D.; Morris, S.E.; Clark, L.; Baker, J.N.; Wolfe, J. Early Bereavement Psychosocial Outcomes in Parents of Children Who Died of Cancer With a Focus on Social Functioning. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, e527–e541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.E.; Nayak, M.M.; Block, S.D. Insights from Bereaved Family Members about End-of-Life Care and Bereavement. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarem, M.; Mohammed, S.; Swami, N.; Pope, A.; Kevork, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Rodin, G.; Hannon, B.; Zimmermann, C. Experiences and Expectations of Bereavement Contact among Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, K.; Swami, N.; Pope, A.; Earle, C.C.; Krzyzanowska, M.K.; Nissim, R.; Hales, S.; Rodin, G.; Hannon, B.; Zimmermann, C. Caregiver Bereavement Outcomes in Advanced Cancer: Associations with Quality of Death and Patient Age. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Post-program interview questions | |

|---|---|

|

Is there anything you liked about (the program)? |

|

How easy or difficult was it to participate in (the program)? |

|

To what extent do you think (the program) made a difference in the lives of people attending it? |

|

Is there anything in particular that you personally had to give up or sacrifice to participate in (the program)? |

|

Do you have a clear understanding of the objectives of the program you were enrolled in? |

|

In your opinion, how confident are you that you were able to perform the tasks required by (the program)? |

|

To what extent do you think (the program) was a good fit with your own values or beliefs? |

| Participant characteristics | N = 18 (Total sample) | % (Total sample) | n = 11 (Living with Loss) | n = 8 (Mourning Walk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Biological sex Female Male |

16 2 |

88.9 11.1 |

9 2 |

7 0 |

|

Age (years)* 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 80-89 |

1 0 1 5 7 3 |

5.6 0 5.6 27.8 38.9 16.7 |

1 0 0 3 4 3 |

0 0 1 2 3 0 |

|

Marital status Widowed Separated/divorced Single (or never married) |

15 1 2 |

83.3 5.6 11.1 |

9 0 2 |

6 1 0 |

|

Ethnicity White (Canadian/European) Latin American Southeast Asian |

15 2 1 |

83.3 11.1 5.6 |

9 1 1 |

6 1 0 |

|

Currently Living with Someone Yes No |

0 18 |

0 100 |

0 11 |

0 7 |

|

Dependents None |

18 |

100 |

11 |

7 |

|

Level of Education completed Undergraduate Graduate High school Technical or vocational school or pre-university degree |

6 5 3 4 |

33.3 27.8 16.7 22.2 |

4 2 3 2 |

2 3 0 2 |

|

Work status Retired Full-time ( > 30 hours/week) Part-time ( < 30 hours/week) Self-employed Disability/sick leave |

12 1 1 2 2 |

66.6 5.6 5.6 11.1 11.1 |

7 1 0 2 1 |

5 0 1 0 1 |

|

Relationship to Deceased Spouse Parent Child |

14 1 3 |

77.8 5.6 16.6 |

8 1 2 |

6 0 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).