1. Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, motile bacterium commonly found in natural environments such as soil and water, as well as in artificial settings including hospitals [

1]. Among the

Pseudomonas genus,

P. aeruginosa is the most clinically significant species due to its role as an opportunistic pathogen, particularly affecting immune-compromised individuals such as patients with HIV/AIDS, cancer, or severe burns. It is associated with a wide range of life-threatening infections, including bacteremia, pneumonia, meningitis, and urinary tract infections. Its ability to survive under aerobic, anaerobic, or low-oxygen conditions and its inherent resistance to multiple antibiotics make it especially challenging to treat and control [

2].

Traditional diagnostic techniques for P. aeruginosa detection are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require expensive instrumentation, limiting their application in low-resource settings. Therefore, the development of a rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective detection method is urgently needed for clinical diagnostics and infection control.

Aptamers are short single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that can bind specific targets including proteins, cells, small molecules, and metal ions with high affinity and specificity [

3]. Compared to antibodies, aptamers offer several advantages such as low immunogenicity, high chemical stability, ease of synthesis and modification, and lower production costs [

4]. The SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment) technique enables the in vitro selection of aptamers that recognize target molecules or cells with high selectivity [

5,

6,

7].

In this study, we present a simple and effective whole-cell SELEX protocol for selecting aptamers specific to P. aeruginosa. The selection process was conducted directly in Eppendorf tubes using heat-inactivated P. aeruginosa cells and a random ssDNA library. Unbound aptamers were removed through washing steps using PBS supplemented with 0.7% Tween-20, followed by centrifugation. Bound aptamers were eluted by heat denaturation and recovered for asymmetric PCR amplification and purification. Ten selection rounds were performed, including counter-selection steps using non-target bacteria in rounds 5 and 7 to enhance specificity. In the final round, enriched aptamers were cloned using the TopoTM TA cloning vector system in Escherichia coli DH5α and sequenced using M13 universal primers. Six aptamer candidates with high binding affinity and specificity toward P. aeruginosa were successfully selected and sequenced. The outcomes of this study have been legally protected under Patent Application No. 2-2025-00350.

To enable visual detection, the aptamers with the highest molecular docking scores indicating the strongest predicted interactions with the bacterial target was selected for conjugation with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) via physical adsorption to form aptamer-AuNP probes for colorimetric detection [

8]. These probes were incorporated into a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) strip. In the LFIA design, the test line (T) contains antibodies against

P. aeruginosa to capture the aptamer–AuNP–bacteria complex, while the control line (C) contains anti-mouse IgG antibodies to bind AuNP–mouse IgG conjugates from the conjugate pad. Upon sample application, capillary action drives the sample along the nitrocellulose membrane. If

P. aeruginosa is present, a red line appears at the T-line due to the accumulation of the complex. A second red line at the C-line confirms proper assay function. This aptamer-based LFIA enables visual detection of

P. aeruginosa within 15 minutes with a detection limit of 10

2 CFU/mL, offering a promising tool for rapid, point-of-care diagnostics and environmental surveillance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

All chemicals and biological reagents used in this study were of analytical grade. Taq PCR Master Mix (2×), GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder (M100), GeneRuler 25 bp DNA Ladder (M25), and 6× DNA loading dye were purchased from Thermo Scientific (USA). RedSafe Nucleic Acid Staining Solution was obtained from INtRON Biotechnology (Korea). Agarose, 10× TBE buffer, and Tween-20 were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). The Quick Gel Extraction Kit was obtained from Invitrogen (USA).

The initial single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) library and primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, USA). The sequence of the forward primer (Aptamer F-primer) was 5′-ATC CGT CAC ACC TGC TCT-3′, and the reverse primer (Aptamer R-primer) was 5′-ATA CGG GAG CCA ACA CCA-3′.

Inactivated bacterial strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (VTCC 12273) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (VTCC 12018) were kindly provided by the Institute of Microbiology and Biotechnology, Vietnam National University, Hanoi.

Mouse IgG antibodies used for comparative assays were purchased from Invitrogen (USA). Materials for lateral flow assay (LFA) strip fabrication, including nitrocellulose membranes, sample pads, conjugate pads, and absorbent pads, were obtained from Merck (Germany).

For cloning experiments, the TOPO TA Cloning® Kit and chemically competent Escherichia coli DH5α cells were purchased from Invitrogen (USA).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. SELEX Procedure

Preparation and Denaturation of Aptamer Library

A synthetic ssDNA library consisting of 91 nucleotides (5′-ATCCGTCACACCTGCTCT–(N)

55–TGGTGTTGGCTCCCGTAT-3′) was used, with a 55-nucleotide randomized central region flanked by fixed primer-binding sites. The library was diluted in 1× PBS to 100 μM, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and rapidly cooled on ice for 10 min to enable proper folding [

6].

Target Binding and Washing

Fifty microliters of the folded ssDNA library were incubated with 100 μL of heat-inactivated

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10

8 CFU/mL) at room temperature for 180 minutes under gentle agitation. After incubation, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (6,000 rpm, 5 min) and washed 3–5 times with PBS 1X containing 0.7% Tween-20. A final rinse was performed with sterile distilled water [

7].

Elution and Amplification

Bound aptamers were eluted by heating at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by centrifugation (12.000 rpm, 5 min). The supernatant containing aptamers was used as a template for PCR amplification using the following primers:

Forward: 5′-ATC CGT CAC ACC TGC TCT-3′

Reverse: 5′-ATA CGG GAG CCA ACA CCA-3′

PCR was carried out with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 10 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were verified via 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Asymmetric PCR and Iterative Selection

Asymmetric PCR (A-PCR) was performed to generate ssDNA for subsequent SELEX rounds. A total of 10 SELEX rounds were conducted, with increasing selection pressure achieved by gradually reducing incubation time (the incubation time in each successive round was reduced to two-thirds of that in the previous round, while the concentrations of both the bacterial cells and the ssDNA library were kept constant).

Counter-selection was conducted in rounds 5 and 7 using

Escherichia coli and

Klebsiella pneumoniae to eliminate non-specific aptamers [

6,

7].

2.3. Cloning and Sequence Analysis

After the final round, aptamer pools were cloned into the TOPO TA vector and transformed into chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells. Colonies were screened on LB agar containing kanamycin and X-gal. 16 Positive colonies were identified via colony PCR using universal M13 primers and sequenced by the Sanger method. Six unique aptamer sequences were selected.

2.4. Docking and Structure Modeling

The secondary structures of selected aptamers were predicted using RNAfold. Tertiary structures were modeled by RNAComposer. The 3D model of the

P. aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigen was constructed using the Glycam web server, and docking was simulated via the HDOCK platform [

9,

10,

11].

2.5. Synthesis and Characterization of AuNPs

Spherical AuNPs (12–15 nm) were synthesized via citrate reduction [

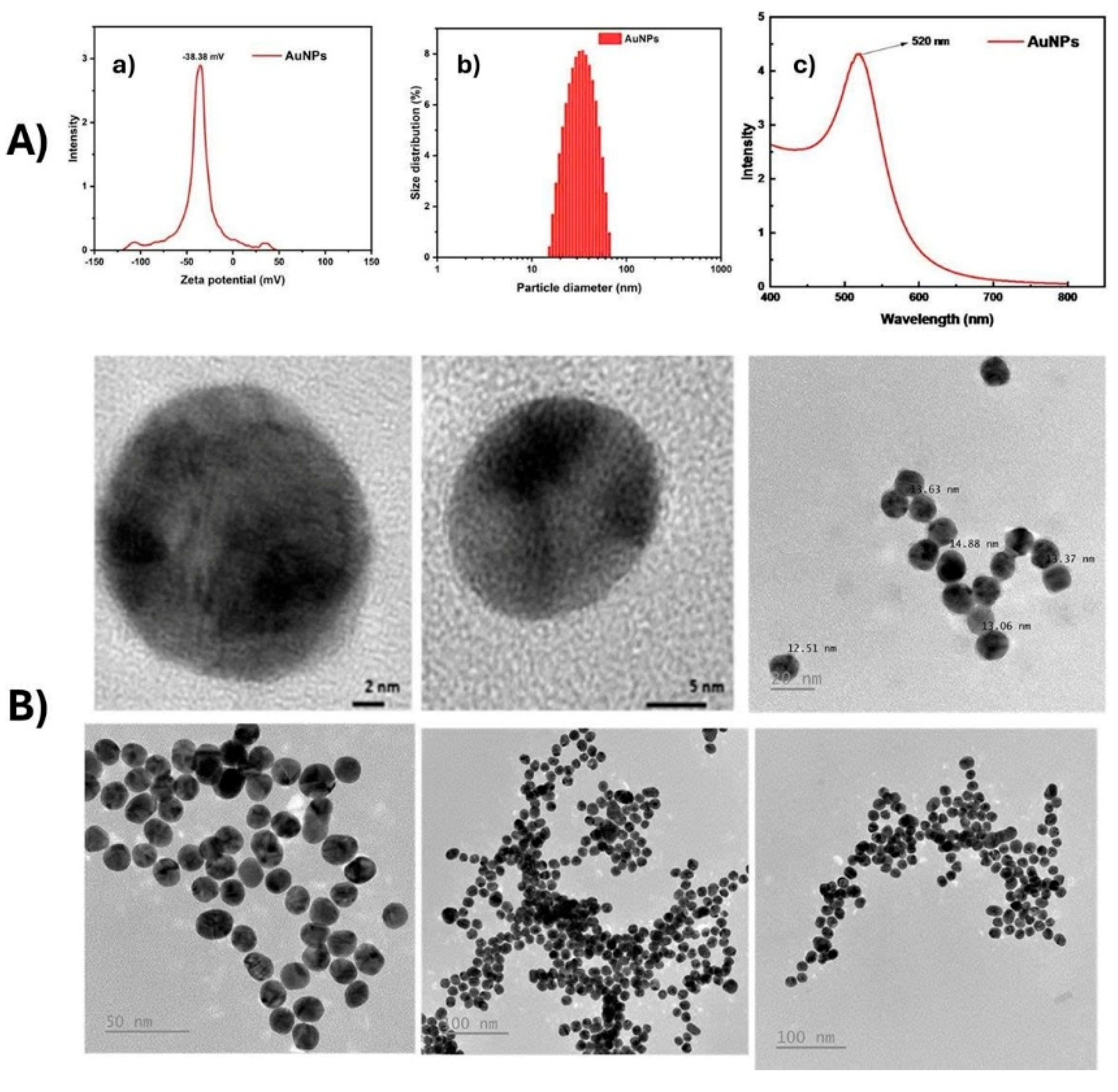

12]. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were comprehensively characterized in terms of their physicochemical properties, the zeta potential of the AuNPs to be approximately –38.38 mV, indicating high colloidal stability due to strong electrostatic repulsion among negatively charged particles (

Figure 1A(a).

Figure 1A(b) presents the particle size distribution obtained via dynamic light scattering (DLS), demonstrating a narrow and uniform size distribution, which confirms good dispersibility of the synthesized nanoparticles.

Figure 1A(c) displays the UV–Vis absorption spectrum, revealing a characteristic surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak at around 520 nm, consistent with spherical AuNPs of approximately 15–20 nm in diameter. High-resolution TEM images clearly show nearly spherical shapes and well-defined crystalline structures of individual particles. The average particle size was found to be in the range of 12–15 nm, in good agreement with the DLS results. Lower-magnification TEM images revealed well-dispersed particles with a high degree of monodispersity and no obvious aggregation, confirming the stability and high quality of the synthesized AuNPs (

Figure 1B). The gold nanoparticle synthesis protocol has been registered for patent (Application No.: 2-2024-00075).

Aptamer–AuNP Conjugation

A mixture of 1 vol of AuNPs and 0.06 vol of 2.8 mg/mL aptamer solution was incubated at 60 °C for 1 h to allow electrostatic adsorption.

IgG–AuNP Conjugation

AuNPs were modified with 0.1 mM MUA (Mercaptosuccinic acid) and activated with 0.1 M NHS and 0.2 M EDC. Goat anti-mouse IgG (1 mg/mL) was added and incubated for 1h at room temperature. BSA was used for blocking nonspecific sites.

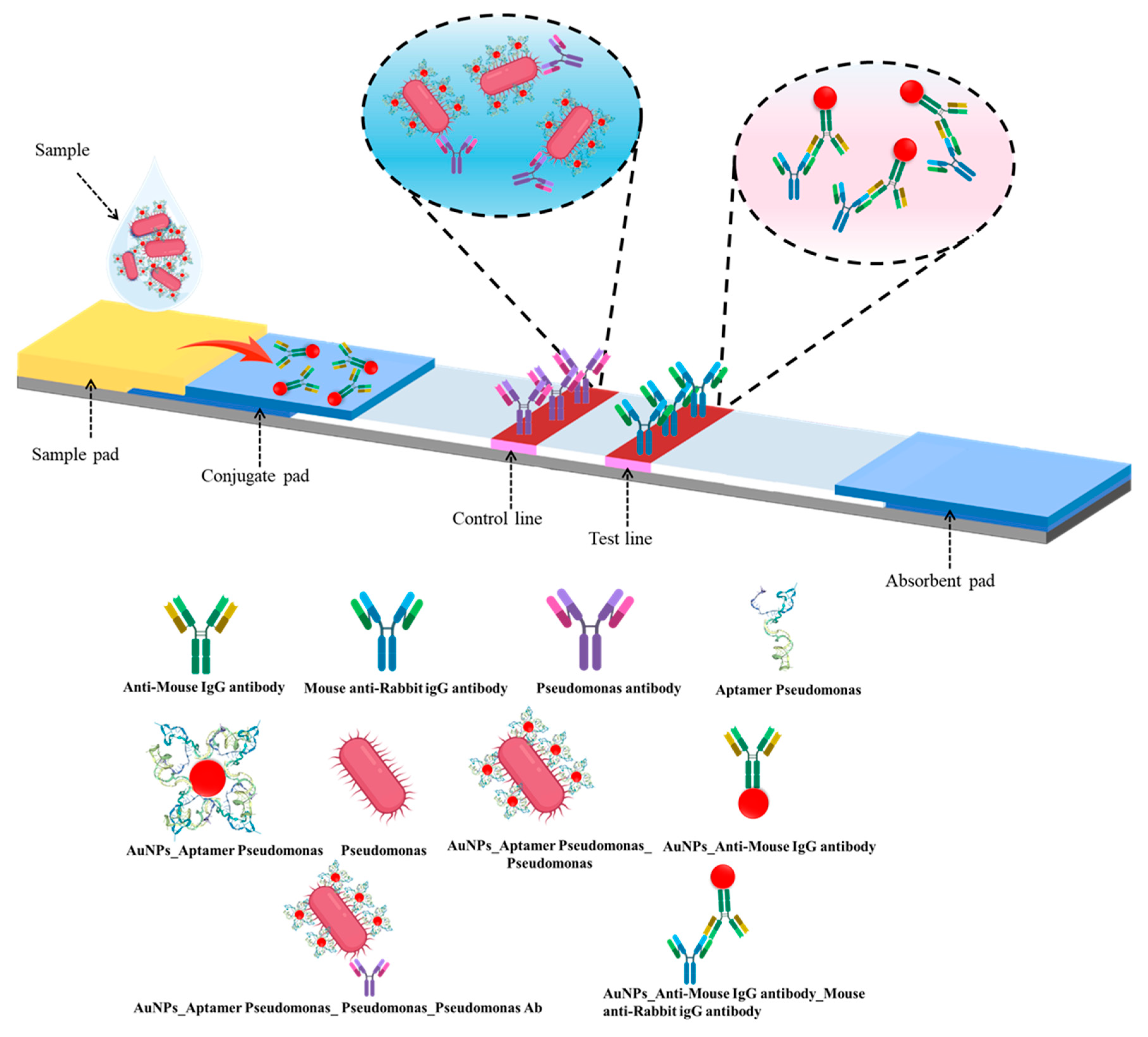

2.7. Fabrication of LFIA

The LFIA strip consisted of a sample pad, conjugate pad, nitrocellulose (NC) membrane, and absorbent pad [

13]. Pads were pretreated with 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1% BSA, 1% sucrose, 0.5% Tween-20, and 0.05% sodium azide. The NC membrane was coated with polyclonal rabbit anti-

Pseudomonas antibodies (1 mg/mL) on the test line (T) and anti-mouse IgG on the control line (C). AuNP–IgG conjugates were applied to the conjugate pad. After drying, all components were assembled, and strips were cut into 3 mm widths. In the test strip design, the conjugate pad was pre-loaded with AuNPs–Mouse IgG complexes, serving as the internal control signal. The test line (T) was immobilized with an antibody specific to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (capture antibody), enabling the capture of the AuNPs–aptamer–bacterium complex via bacterial surface antigens. The control line (C) was coated with anti-Mouse IgG antibodies to capture the AuNPs–Mouse IgG complex from the conjugate pad. Upon sample application to the sample pad, the mixture migrated along the nitrocellulose membrane by capillary action. In the presence of the target bacterium, the AuNPs–aptamer–bacterium complex was retained at the test line, resulting in the appearance of a red band at this location. Simultaneously, the AuNPs–Mouse IgG control conjugate interacted with the anti-Mouse IgG at the control line, generating a red band that confirmed the proper functioning of the assay (

Figure 2)

2.8. Sample Detection Procedure

Samples containing P. aeruginosa at concentrations ranging from 10¹ to 109 CFU/mL were mixed with AuNP–aptamer conjugates at a 1:0.03 (v/v) ratio and incubated at 60 °C for 30 minutes. The resulting mixtures were applied to the sample pad of the LFIA strip. In positive samples, a red band appeared at the test line due to accumulation of AuNP–aptamer–bacteria complexes, while a red band at the control line confirmed assay validity. Negative controls included bacteria-free samples (blank) and samples containing Escherichia coli or Klebsiella pneumonia (103 CFU/mL), which did not produce a visible test line.

3. Results and Discussion

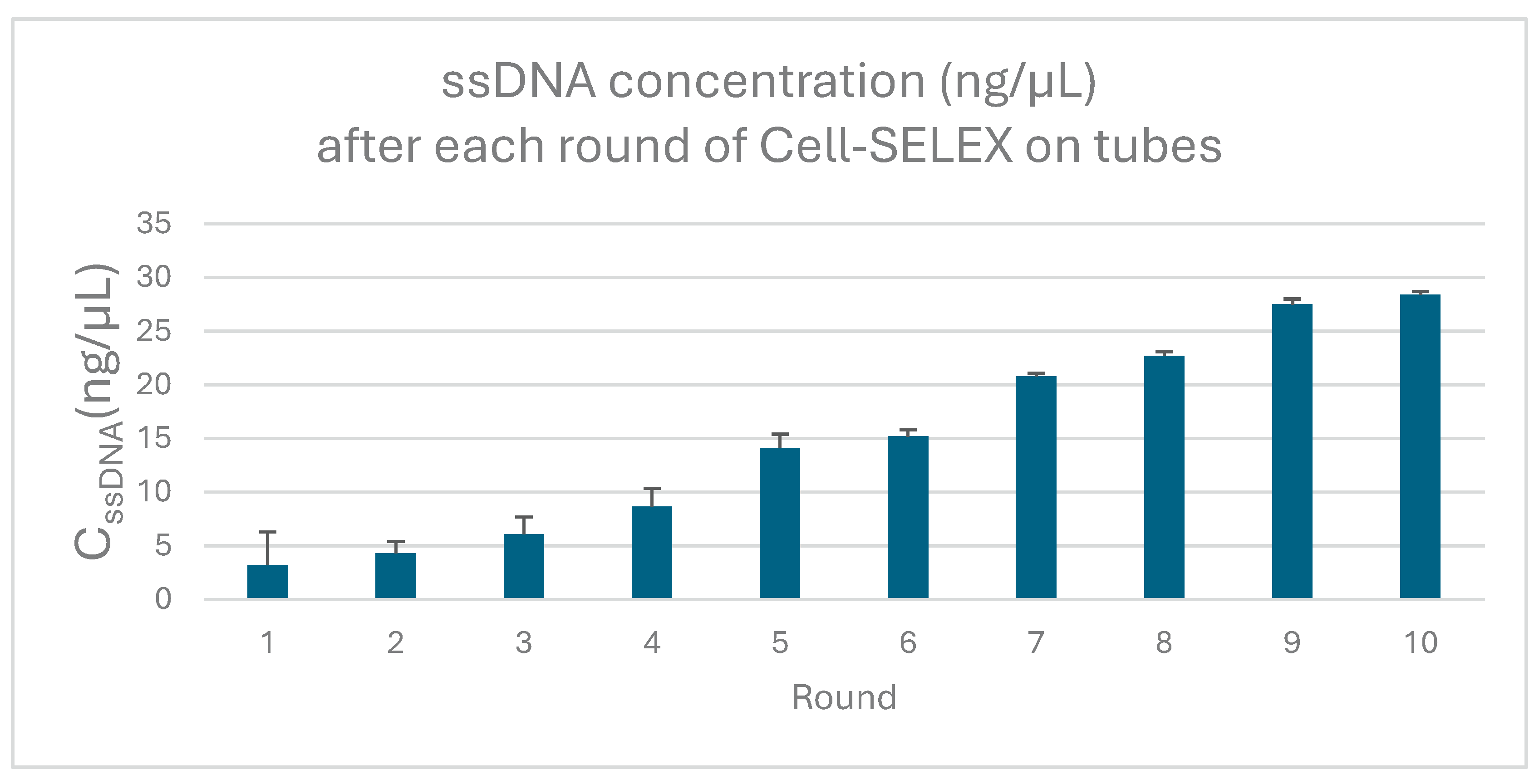

3.1. Aptamer Enrichment and Characterization

The concentration of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) recovered after each round of SELEX increased gradually, indicating an enrichment of sequences with higher binding affinity to

P. aeruginosa. (

Figure 3).

After ten rounds of whole-cell SELEX and counter-selection with Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae to eliminate non-specific binders, the enriched aptamer pool was cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning® Kit. Sixteen white colonies were selected and subjected to plasmid extraction and Sanger sequencing using universal M13 primers. Sequence analysis revealed that six aptamer sequences were predominant, suggesting a convergence towards specific binding motifs.

These six representative sequences were further analyzed for secondary structure (via Mfold) [

9,

14] and molecular docking affinity (via HDOCK) [

11,

15] with the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) region on the surface of

P. aeruginosa. Details of the aptamer selection process including docking scores, 2D/3D structure models, and docking interaction images are provided in the

Table 1.

MFE (Minimum Free Energy (ΔG)): refers to the lowest predicted free energy value. The MFE model represents a two-dimensional (2D) secondary structure of the aptamer, generated by maximizing the number of complementary base pairings to achieve the minimum free energy.

Frequency: indicates the percentage of a particular aptamer conformation present in the environment. For instance, the MFE conformation of aptamer T1 appears with a frequency of 24.98%, meaning that approximately 25 out of every 100 aptamer molecules adopt this structure at any given time.

Diversity score: is calculated based on the entropy distribution of each aptamer sequence. Higher entropy values reflect greater structural instability and consequently higher diversity. This score represents the overall structural variability of all predicted conformations associated with a single aptamer sequence.

Docking score: represents the binding energy loss when the aptamer interacts with the LPS molecule [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Among the six selected aptamers, aptamer T1 was the most frequently occurring sequence (identified in 4 out of 16 colonies). It also exhibited exhibited the highest MFE conformation frequency and the lowest diversity score among all candidates. Notably, T1 also achieved the most favorable docking score when interacting with the LPS of

P. aeruginosa, highlighting its strong potential as a biological recognition probe. Moreover, T1 sequences predominantly formed classical stem-loop structures—motifs commonly associated with enhanced target affinity and structural stability [

17], therefore, aptamer T1 was selected for further evaluation of its ability to bind gold nanoparticles and recognize

Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

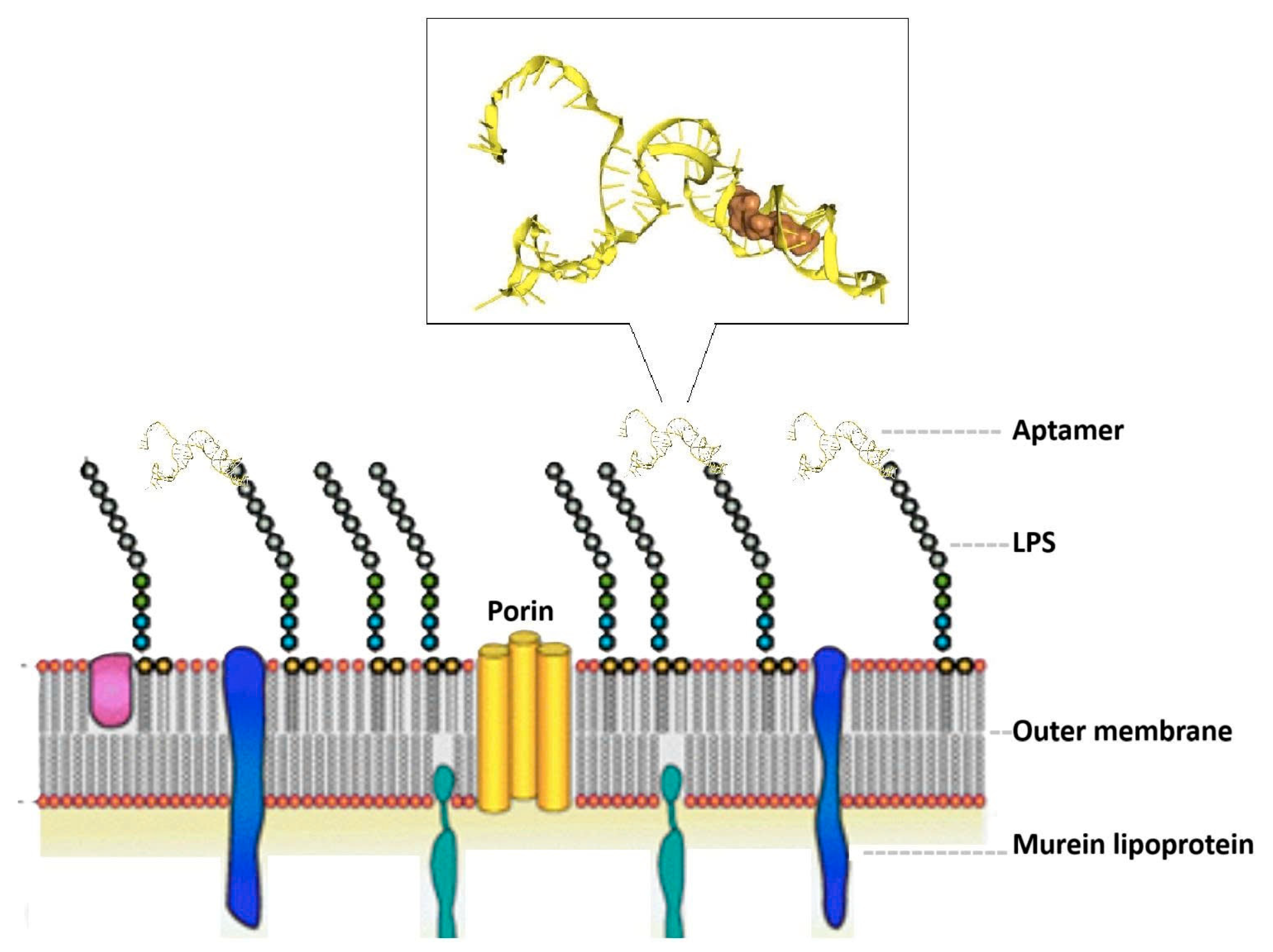

The docking interaction models of aptamers T1 with the LPS target is shown in

Figure 4.

3.2. Aptamer–AuNP Conjugation and Optimization

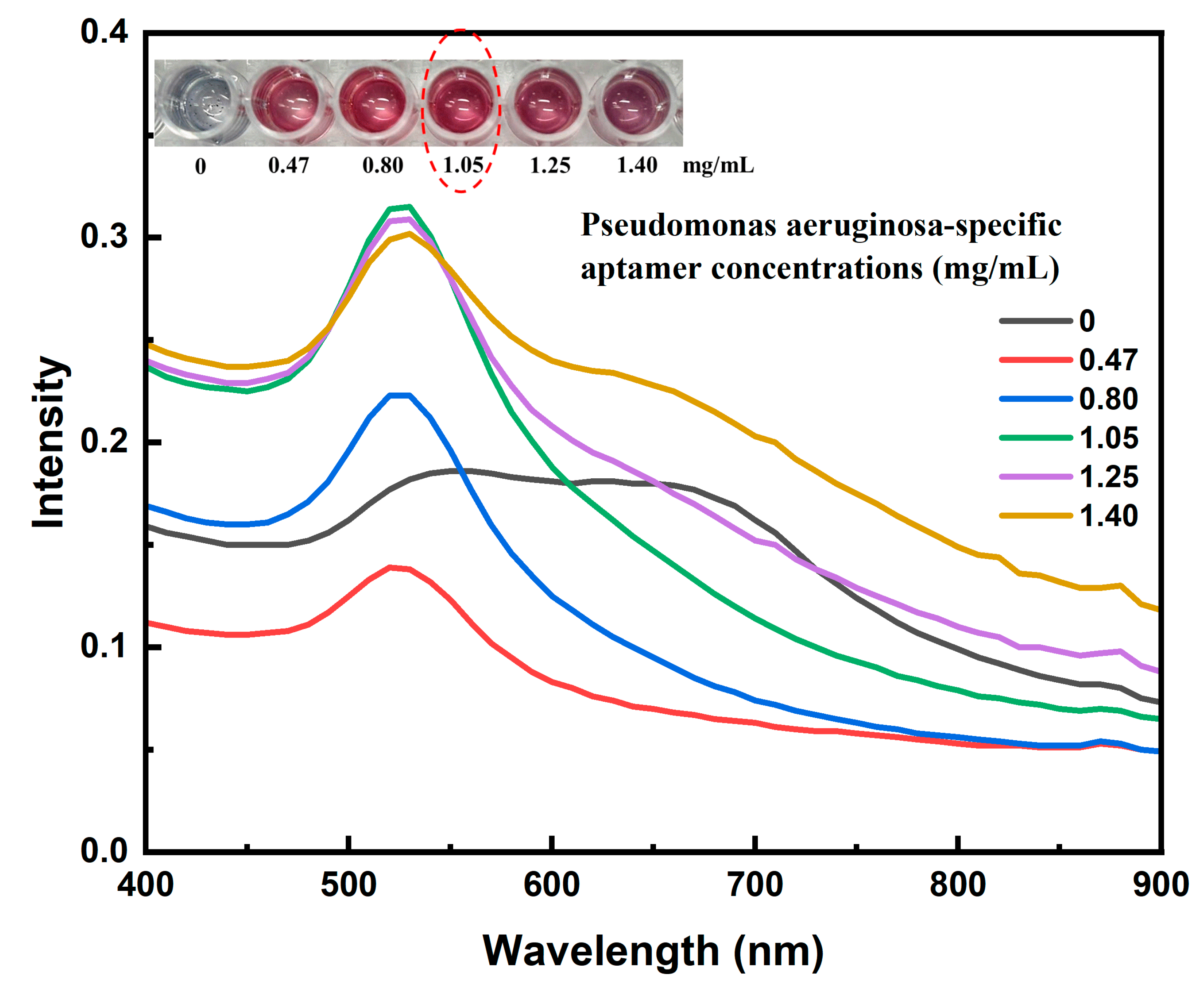

Optimizing the concentration of aptamer is a critical step to ensure efficient conjugation with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) via physical adsorption, while also enhancing the stability of the nanoparticle system under high-ionic-strength conditions – a common requirement in lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) applications.

In this study, the conjugation and stabilization capacity of the AuNPs–aptamer complex were evaluated by incubating AuNPs with various volumes (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 µL) of an aptamer stock solution (2.8 mg/mL), corresponding to final concentrations of 0, 0.47, 0.80, 1.05, 1.25, and 1.40 mg/mL, respectively. The mixtures were incubated in borate buffer (pH 9) at 60 °C for 1 hour. Subsequently, 10 µL of 10% NaCl solution was added to each mixture to assess salt-induced aggregation – an indirect indicator of surface coverage and nanoparticle stability.

Visual observations indicated that at low aptamer concentrations (≤ 0.80 mg/mL), the color of the solution changed from the characteristic ruby red of stable AuNPs to gray or pale purple upon salt addition, indicating aggregation due to insufficient aptamer coverage. UV–Vis spectra confirmed this, showing a significant decrease or red-shift in the plasmon peak near ~520 nm. In contrast, at higher aptamer concentrations (≥ 1.05 mg/mL), the solution retained its red color, and the UV–Vis spectra maintained a strong plasmon resonance peak between 520–525 nm, indicating stable, non-aggregated nanoparticles. Notably, increasing the aptamer concentration beyond 1.05 mg/mL did not significantly enhance stability, suggesting surface saturation of the AuNPs.

Therefore, a final concentration of 1.05 mg/mL was selected as the optimal condition for subsequent conjugation processes. The use of borate buffer at pH 9 and incubation at 60 °C likely promoted efficient physical adsorption of aptamers onto the AuNP surface, leading to a more uniform and stable coating. This optimization not only ensures effective aptamer loading but also enhances the sensitivity and long-term stability of the biosensor system, particularly in microbial diagnostics such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa detection (

Figure 5).

3.3. Performance of the Hybrid LFIA Strip

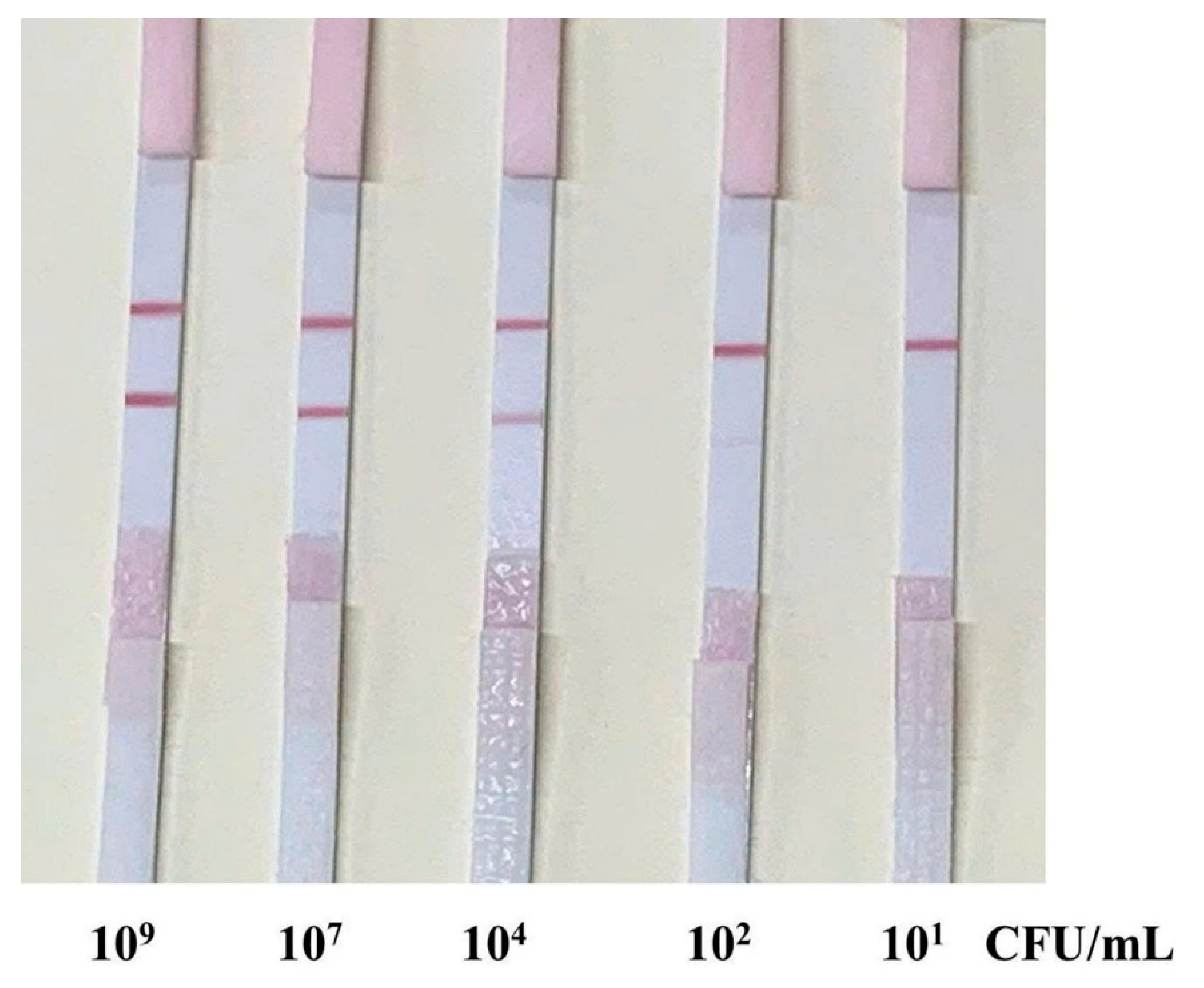

The performance of the developed LFIA strip using aptamer T1 was evaluated by testing its ability to detect Pseudomonas aeruginosa in spiked samples (samples containing varying concentrations of P. aeruginosa (from 10¹ to 109 CFU/mL)). The AuNPs–aptamer T1 conjugate was mixed with each sample and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes to facilitate target recognition and complex formation (AuNP–aptamer–bacteria). The mixture was then applied to the sample pad of the test strip, and results were observed after 10 -15 minutes.

In positive samples containing

P. aeruginosa (from 10

1 to 10⁹ CFU/mL), both the C and T lines were observed, with the intensity of the T line varying depending on bacterial concentration (

Figure 6). At high concentrations (10⁹–10⁷ CFU/mL), the T line was clearly visible and sharp, indicating effective capture of the AuNP–aptamer–bacteria complex at the test zone. As the bacterial concentration decreased to 10⁵–10² CFU/mL, the T line became gradually fainter but remained visually detectable. At 10¹ CFU/mL, the T line was barely visible or undetectable to the naked eye, suggesting a visual detection limit of approximately 10²–10³ CFU/mL (

Figure 6).

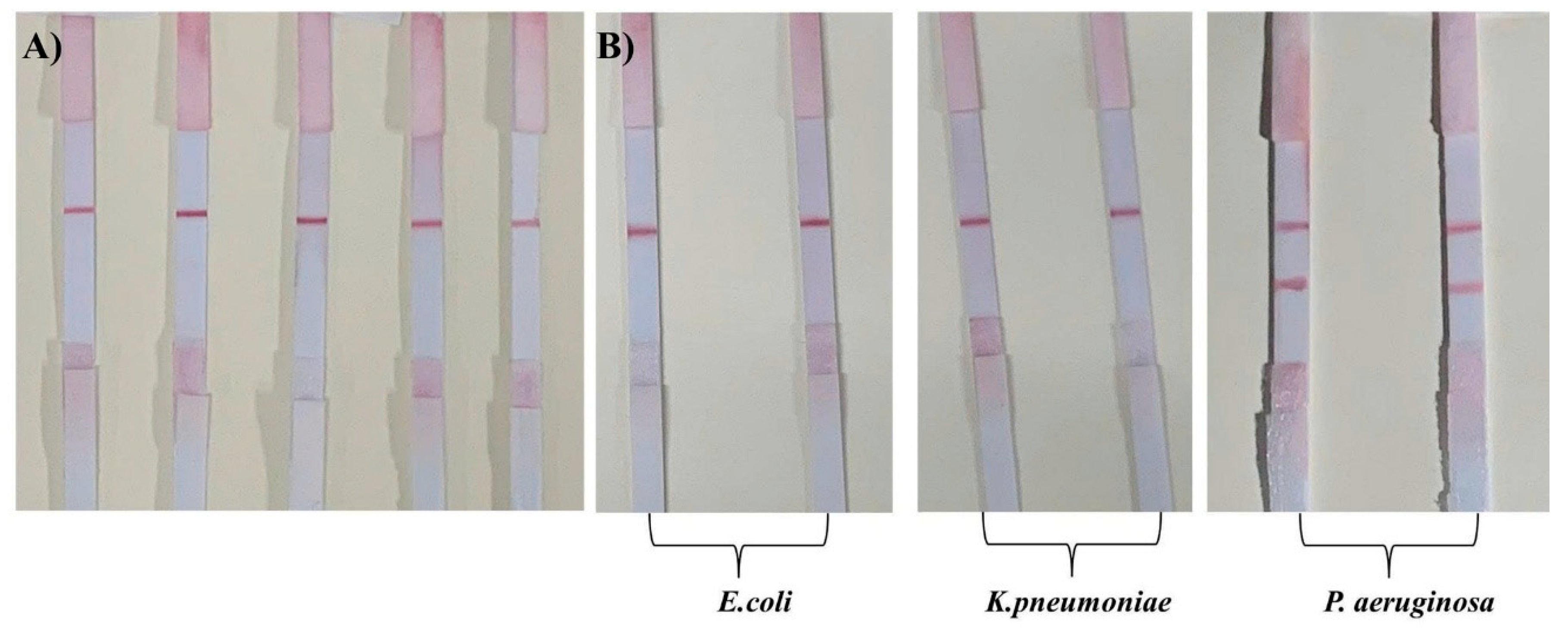

3.4. Specificity Evaluation

Negative samples including: bacteria-free (blank),

E.coli 10

3 CFU/mL,

K. pneumoniae 10

3 CFU/mL samples and positive samples containing

P. aeruginosa 10

3 CFU/mL were prepared. In negative samples, with the samples do not contain bacteria, only the control line (C line) appeared, while the test line (T line) was absent (

Figure 7A). This result confirms the absence of false-positive signals, indicating that the aptamer did not exhibit nonspecific interactions with sample matrix components, and that the AuNPs were not retained nonspecifically at the test line. This high selectivity is essential for reliable use in real-world diagnostic settings.

When tested with samples containing

E. coli,

K. pneumoniae, and

P. aeruginosa at the same concentration of 10³ CFU/mL, only the test strip for

P. aeruginosa sample showed two distinct bands at both test (T) line and control (C) lines, whereas the strips for

E. coli and

K. pneumoniae displayed only a single band at the control line, with no visible band at the test line (

Figure 7B)

These findings demonstrate that the selected aptamer T1 exhibited strong binding specificity to P. aeruginosa, functioning effectively both in solution and within the LFIA format. The ability of the aptamer to specifically capture the target bacteria and facilitate signal generation on the test strip provides a strong foundation for further development of aptamer-based rapid diagnostic platforms targeting bacterial pathogens.

3.5. Advantages and Perspectives of Aptamer-Based LFIA

The concept that nucleic acids can function as ligands and regulate the activity of target proteins originated from studies on HIV. HIV encodes small RNA molecules that bind to intracellular proteins, facilitating viral replication or suppressing host antiviral responses. In a pioneering study, Sullenger et al. (1990) demonstrated that an RNA aptamer designed to bind viral proteins could inhibit HIV replication by competitively interacting with the trans-activating response (TAR) element [

20]. This marked a turning point in biomedical research, highlighting the potential of aptamers as versatile molecular tools with broad applications in diagnostics and therapeutics.

Aptamers offer several advantages over traditional antibodies, including high chemical stability, ease of chemical synthesis, low immunogenicity, and the ability to undergo structural modifications to enhance bioavailability. Aptamers can bind specifically and tightly to a wide range of targets, such as proteins, cells, and small molecules, making them powerful tools for molecular recognition and biomedical applications [

21]

In diagnostics, aptamers have been widely employed in biosensors to detect disease-associated biomarkers, including those related to cancer, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular disorders. Aptamer-based biosensors have shown strong potential for detecting pathogens or toxins in clinical specimens [

7]. Therapeutically, aptamers function similarly to antibodies. Pegaptanib (Macugen), the first aptamer approved by the U.S. FDA, is used for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Aptamers are also being investigated as inhibitors of cancer-related and autoimmune-associated proteins [

22]. Additionally, aptamers play an important role in molecular biology assays, protein purification, and studies of molecular interactions within cells [

16].

Due to their high specificity, chemical robustness, reusability, and ability to penetrate tissues effectively, aptamers are highly promising for the development of cost-effective, sensitive, and specific bioanalytical platforms. Traditional aptamer selection methods often rely on purified proteins or peptides as targets, which may not accurately represent the native conformation of surface molecules on intact cells or bacteria. As a result, selected aptamers may fail to recognize the natural structure of the targets. To address this limitation, Song et al. (2017) introduced the toggle-cell SELEX method, which involves alternating target species during selection rounds to generate aptamers with broader recognition profiles [

7].

Building on this concept, our study implemented a modified SELEX protocol using inactivated whole bacterial cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa incubated directly with the aptamer library in Eppendorf tubes. This approach reduced procedural complexity, improved safety, and allowed a higher number of bacterial cells to be screened compared to traditional microtiter plate-based protocols. Whole-cell selection enhances the likelihood of obtaining aptamers with strong affinity and specificity for the native surface of P. aeruginosa. To further improve selectivity, counter-selection against Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae was performed during the 5th and 7th rounds, eliminating non-specific aptamers.

After 10 rounds of selection, six aptamers with high binding affinity to P. aeruginosa were identified. Molecular docking analysis revealed that aptamers T1 and T4 exhibited stable secondary structures and superior binding performance. These two aptamers were integrated into a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) system, replacing the conventional detection antibody. The detection mechanism involves the formation of an AuNP–aptamer complex via physical adsorption, which binds to the target bacteria if present in the sample. This complex is captured at the test line (T) by immobilized capture antibodies, producing a red signal due to the intrinsic color of gold nanoparticles.

Experimental results demonstrated T1 aptamers specifically detected P. aeruginosa with a detection limit of 10² CFU/mL within 15 minutes. The developed LFIA strip offers multiple advantages, including rapid response time, low cost, ease of use, and no need for specialized equipment. Moreover, the dry-storage capability at room temperature makes this platform highly suitable for point-of-care testing (POCT), especially in resource-limited settings.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully established an improved whole-cell SELEX protocol utilizing inactivated Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells, combined with in silico evaluation based on thermodynamic stability and molecular docking analysis. Six high-affinity aptamers were identified, among which T1 and T4 demonstrated superior structural stability and binding performance. These aptamers were effectively conjugated to gold nanoparticles and incorporated into a hybrid lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA), replacing conventional detection antibodies. The resulting platform enabled rapid, visual detection of P. aeruginosa with high specificity and a detection limit as low as 10² CFU/mL, without the need for specialized instrumentation.

Importantly, the methodology described here offers broad adaptability for future applications. The use of whole-cell SELEX allows aptamer selection directly against intact microbial cells, circumventing the need for purified antigens and enabling the recognition of native surface epitopes. Moreover, the hybrid LFIA format, which combines aptamer detection with antibody-based capture, provides a robust and flexible architecture that can be easily tailored to other bacterial or viral targets simply by replacing the aptamer component.

Given their chemical stability, low production cost, and high specificity, aptamers hold strong potential as alternatives to antibodies in diagnostic assays. The platform developed in this study serves as a proof-of-concept for a new generation of aptamer-based diagnostics that are rapid, scalable, and suitable for point-of-care use, especially in resource-limited settings. Future research may extend this approach to clinically and epidemiologically important pathogens such as Salmonella spp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, contributing to enhanced infectious disease surveillance, outbreak preparedness, and global health response.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Vietnam Ministry of Science and Technology under grant number 03.M04.2023.

References

- Balcht Aldona & Smith Raymond. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Infections and Treatment. Informa Health Care 1994. 83–84. ISBN 0-8247-9210-6.

- Archana Vishwakarma, Yogesan Meganathan & Mohandass Ramya. Aptamer-based assay for rapid detection, surveillance,

and screening of pathogenic Leptospira in water samples, Scientific Reports 2023, 13:13379. [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A.D. , Szostak J.W., In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alariqi R., Almansoob S., Senan A. M., Raj,A. K., Shah R., Shrewastwa M. K., & Kumal, J. P. P., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related antibiotic resistance genes as indicators for wastewater treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10(9). [CrossRef]

- Gold Larry, “SELEX: How It Happened and Where It will Go”. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2015, 81 (5–6): 140–143. [CrossRef]

- Craig Tuerk, Gold Larry, Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment: RNA Ligands to Bacteriophage T4 DNA Polymerase. Science 1990, (249), N0 4968: 505-510. [CrossRef]

- Min Young Song, Dung Nguyen, Seok Won Hong, Byoung Chan Kim, Broadly reactive aptamers targeting bacteria belonging to different genera using a sequential toggle cell-SELEX, Scientific reports 2017, (7), 43641. [CrossRef]

- Li R. S.; Liu H.; Chen B. B.; Zhang H. Z.; Huang C. Z.; Wang J., Stable gold nanoparticles as a novel peroxidase mimic for colorimetric detection of cysteine. Analytical Methods, 2016, 8 (11), 2494–2501. [CrossRef]

- Kerpedjiev P., Hammer S., Hofacker I.L., Forna (force-directed RNA): Simple and effective online RNA secondary structure diagrams. Bioinformatics 2015, 31(20): 3377-9). [CrossRef]

- Iman Jeddi, Leonor Saiz, Three-dimensional modeling of single stranded DNA hairpins for aptamer-based biosensors. Scientific Report 2017, (7), 1178. [CrossRef]

- Yumeng Yan, Huanyu Tao, Jiahua He & Sheng-You Huang, The HDOCK server for integrated protein–protein docking, Nature Protocol 2020, 15, 1829–1852.

- The HDOCK server: http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.

- Thu Thao Pham Thien-Kim Le Nguyen, T. T Huyen, Nam Luyen Van, Tin Phan Nguy, Dai Lam Tran, Lien Truong T N, Staining-Enhanced Peroxidase-Mimicking Gold Nanoparticles in NanoELISA for Highly Sensitive Detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae. ACS omega 2023, 8.51, 8.51,49211–49217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulelah A Alrashoudi, Hamed I Albalawi, Ali H Aldoukhi, Manola Moretti, Panayiotis Bilalis, Malak Abedalthagafi, Charlotte A E Hauser, Fabrication of a Lateral Flow Assay for Rapid In-Field Detection of COVID-19 Antibodies Using Additive Manufacturing Printing Technologies, International Journal of Bioprinting 2021, 7(4), 399. [CrossRef]

- Ronny Lorenz, Stephan H. Bernhart, Christian Höner zu Siederdissen, Hakim Tafer, Christoph Flamm, Peter F. Stadler, and Ivo L. Hofacker, ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms for Molecular Biology 2021, 6(1), 26. [CrossRef]

- Rudi Liu, Dr. Jiuxing Li, Prof. Dr. Bruno J. Salena, Prof. Dr. Yingfu Li (2024). Aptamer and DNAzyme Based Colorimetric Biosensors for Pathogen Detection. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, Volume 64, Issue 4. [CrossRef]

- Xuan Ding, Chao Xu, Bin Zheng, Hanyang Yu and Peng Zheng (2024). Molecular Mechanism of Interaction between DNA Aptamer and Receptor-Binding Domain of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Variants Revealed by Steered Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Molecules, 29, 2215. [CrossRef]

- Hong Li Zhang, Cong Lv, Zi Hua Li, Song Jiang, Dan Cai, Shao Song Liu, Ting Wang, Kun He Zhang, Analysis of aptamer-target binding and molecular mechanisms by thermofluorimetric analysis and molecular dynamics simulation, Frontiers in Chemistry 2023, 11:1144347. [CrossRef]

- Alexander Eisold, Dirk Labudde, Detailed Analysis of 17β-Estradiol-Aptamer Interactions: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study, Molecules 2018: 23(7), 1690. [CrossRef]

- Alan Fernando Rodríguez Serrano I-Ming Hsing, Prediction of Aptamer-Small-Molecule Interactions Using Metastable States from Multiple Independent Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2022, 62(19), 4799-4809. [CrossRef]

- Sullenger A.B, Gallardo H.F., Ungers G.E., Gilboa E., Overexpression of TAR sequences renders cells resistant to human immunodeficiency virus replication. Cell 1990, 63 (3) 601-608). [CrossRef]

- Kolm, C., Cervenka, I., Aschl, U.J. et al. DNA aptamers against bacterial cells can be efficiently selected by a SELEX process using state-of-the art qPCR and ultra-deep sequencing. Scientific Repots 2020, 10, 20917. [CrossRef]

- Duong Tuan Bao, Do Thi Hoang Kim, Hyun Park, Bui Thi Cuc et al., Rapid Detection of Avian Influenza Virus by Fluorescent Diagnostic Assay using an Epitope-Derived Peptide. Theranostics 2017. 10; 7(7): 1835-1846. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).