Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Food Image Recognition

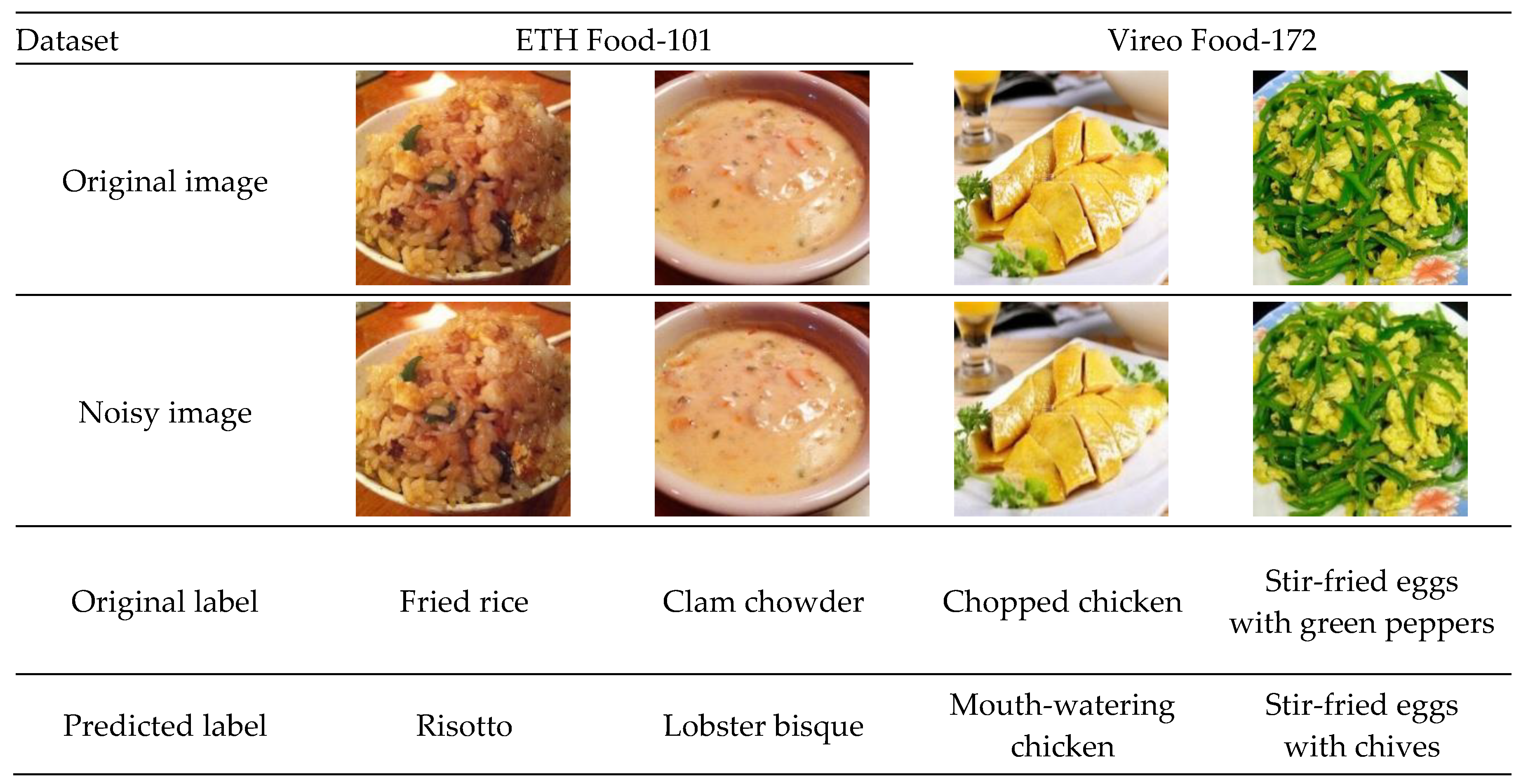

2.2. Application of Anti-Noise Technology in Image Recognition

3. Approach

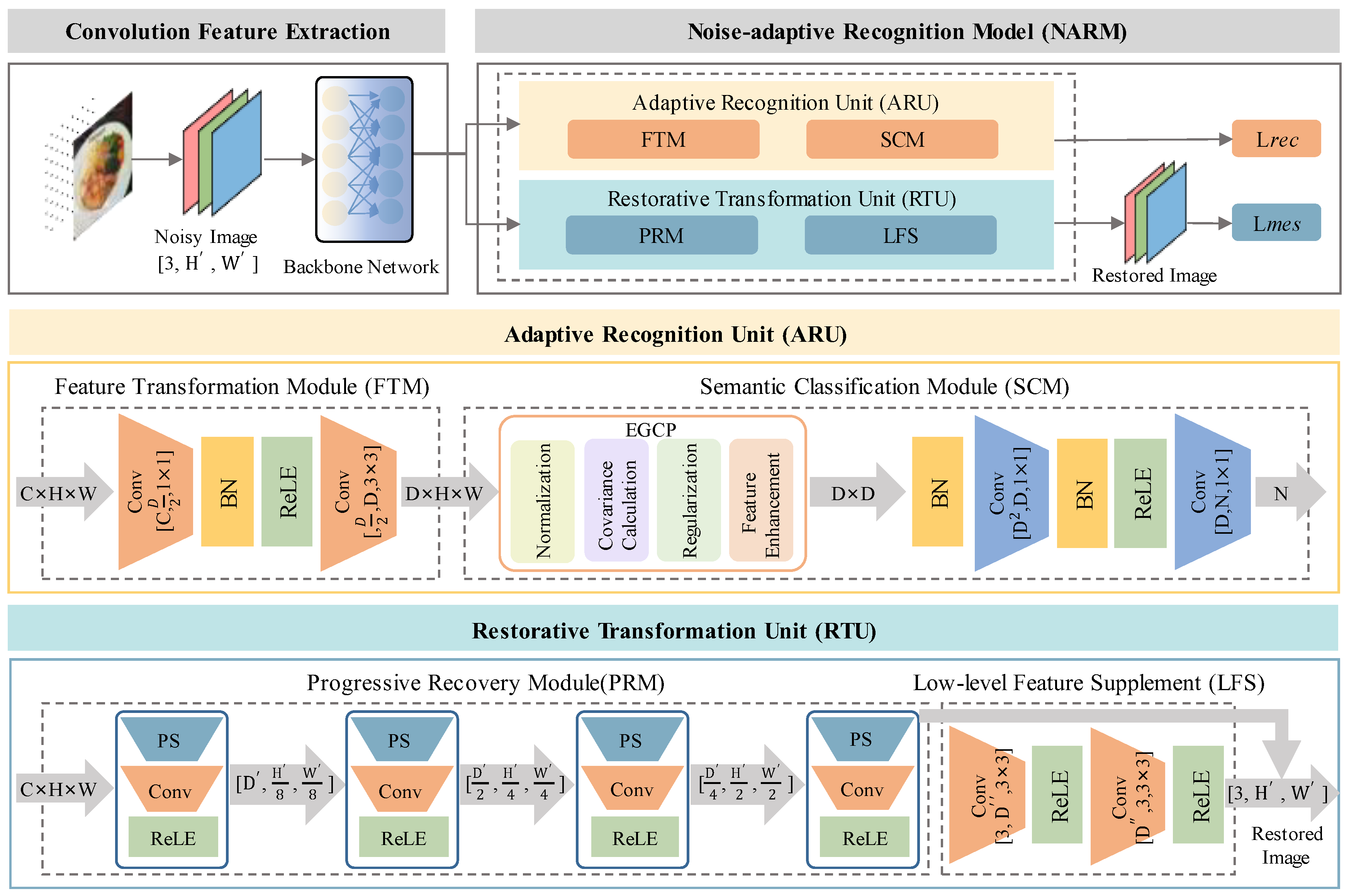

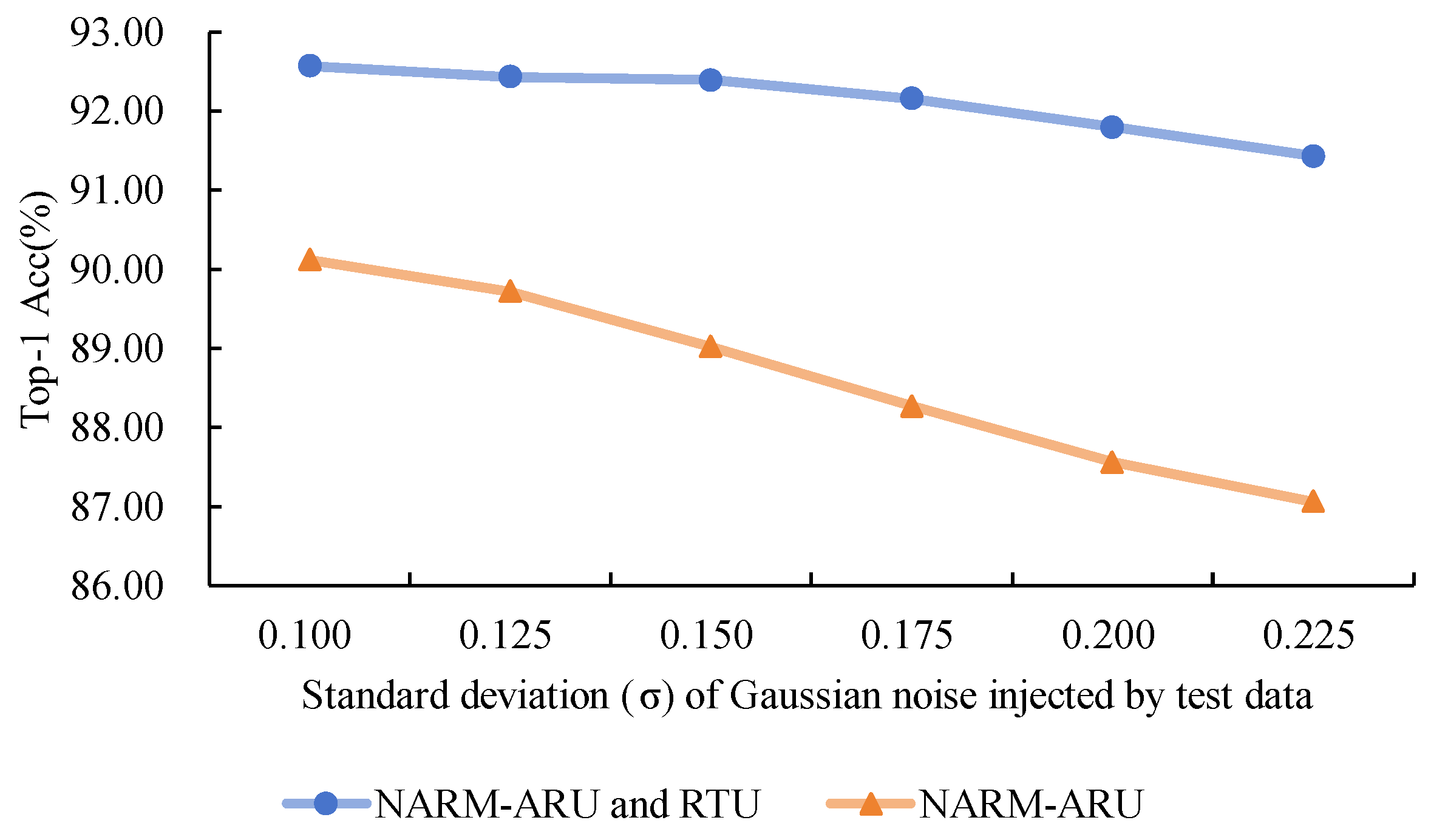

3.1. Noise Adaptive Recognition Module

3.2. Weighted Multi-Granularity Fusion

| Algorithm 1 Weighted Multi-Granularity Fusion | |

| Require: Given a dataset (where represents the total number of batches in ) | |

| 1: | for epoch = 1 to num_of_epochs do |

| 2: | for (input, target) in do |

| 3: | for n = 1 to S do |

| 4: | |

| 5: | # NARM |

| 6: | |

| 7: | BACKWARD() |

| 8: | end for |

| 9: | # WMF |

| 10: | |

| 12: | |

| 13: | BACKWARD() |

| 14: | end for |

| 15: | end for |

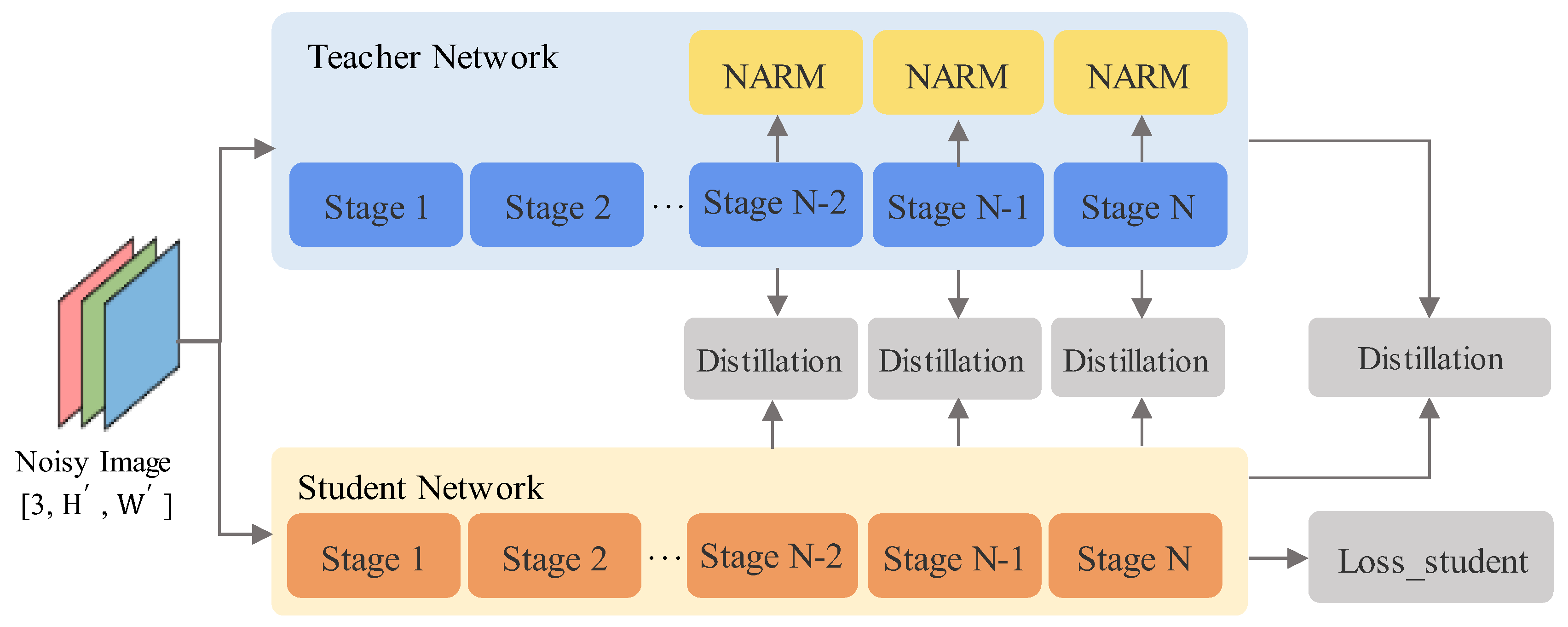

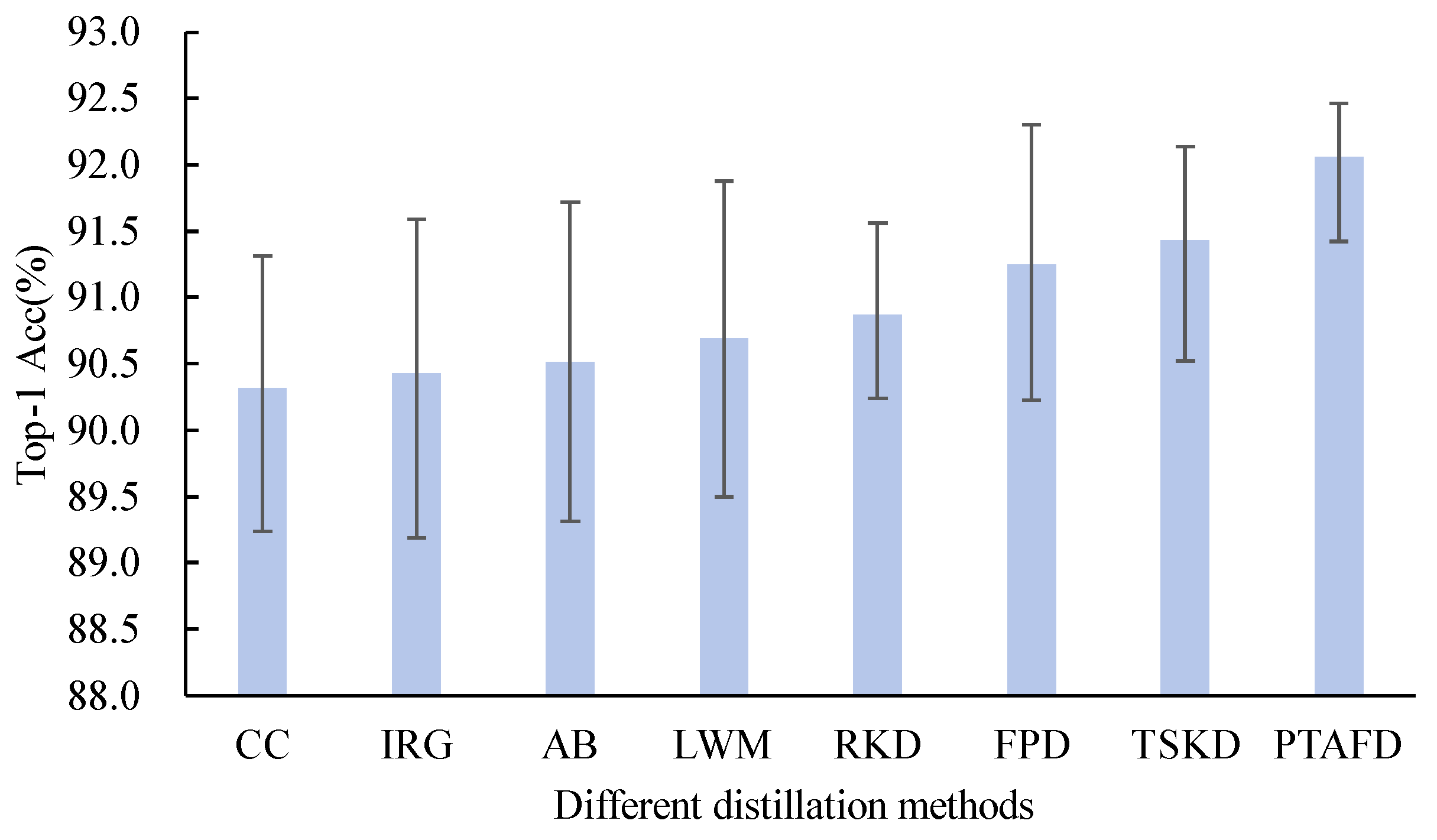

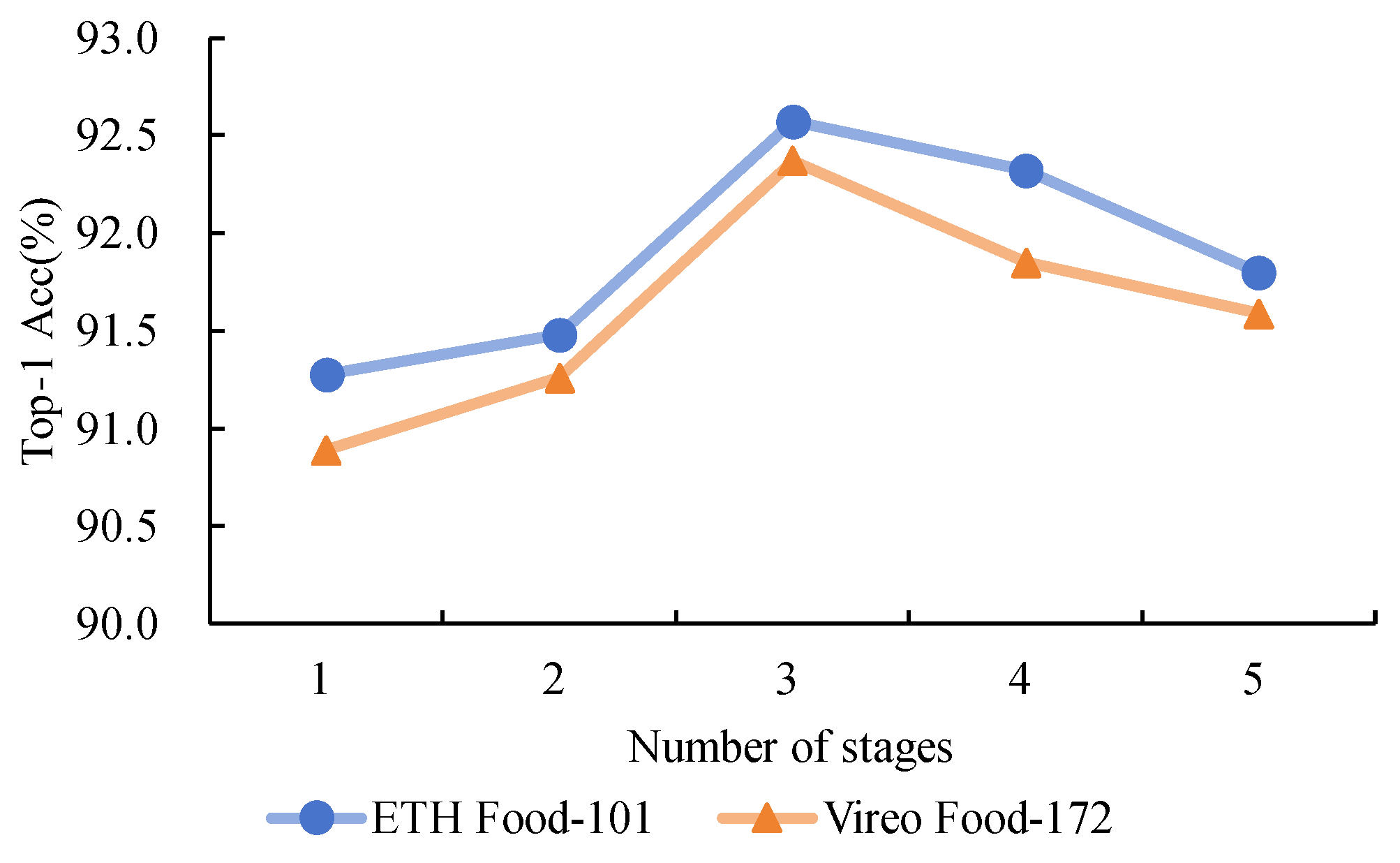

3.3. Progressive Temperature-Aware Feature Distillation

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset

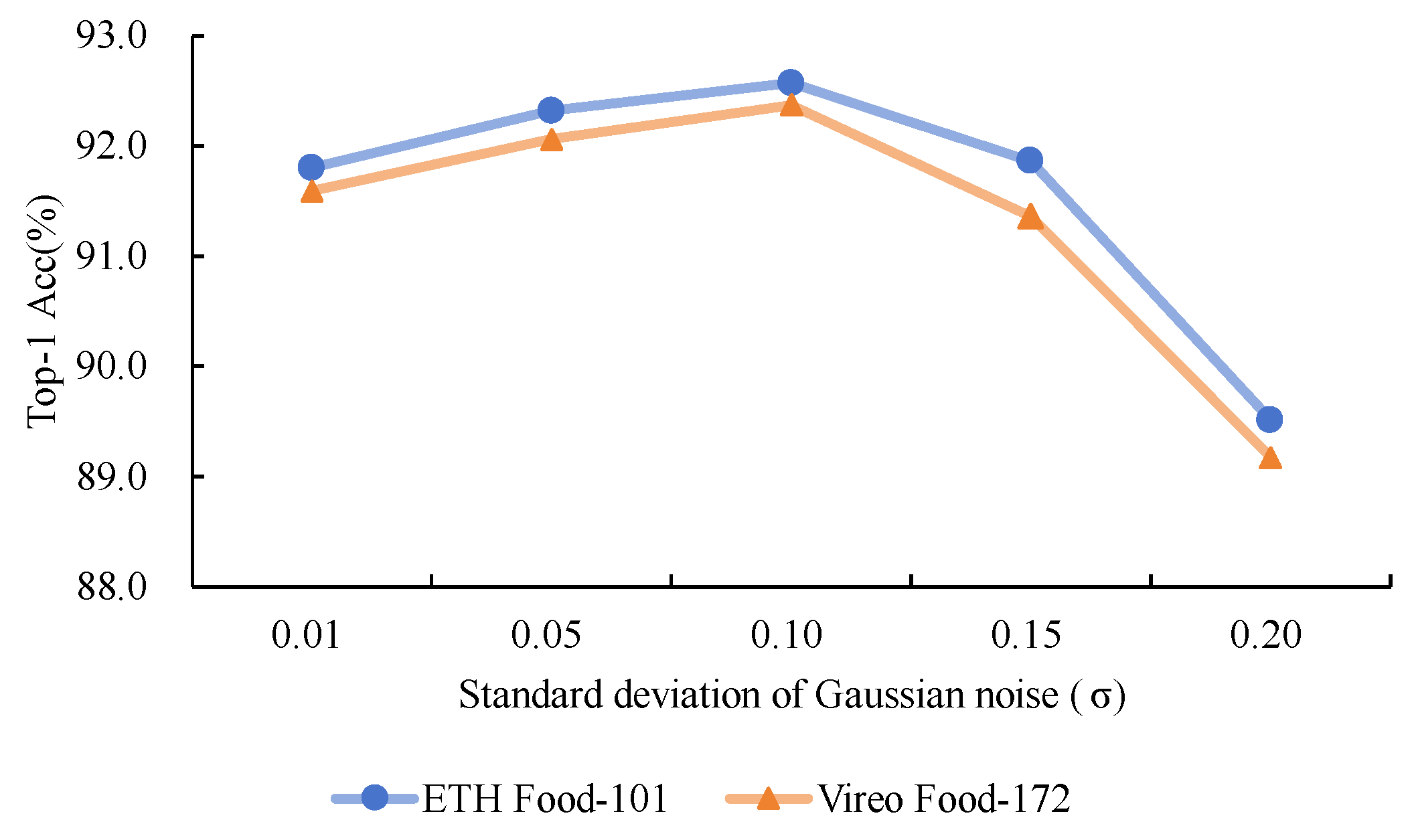

4.2. Experimental Settings

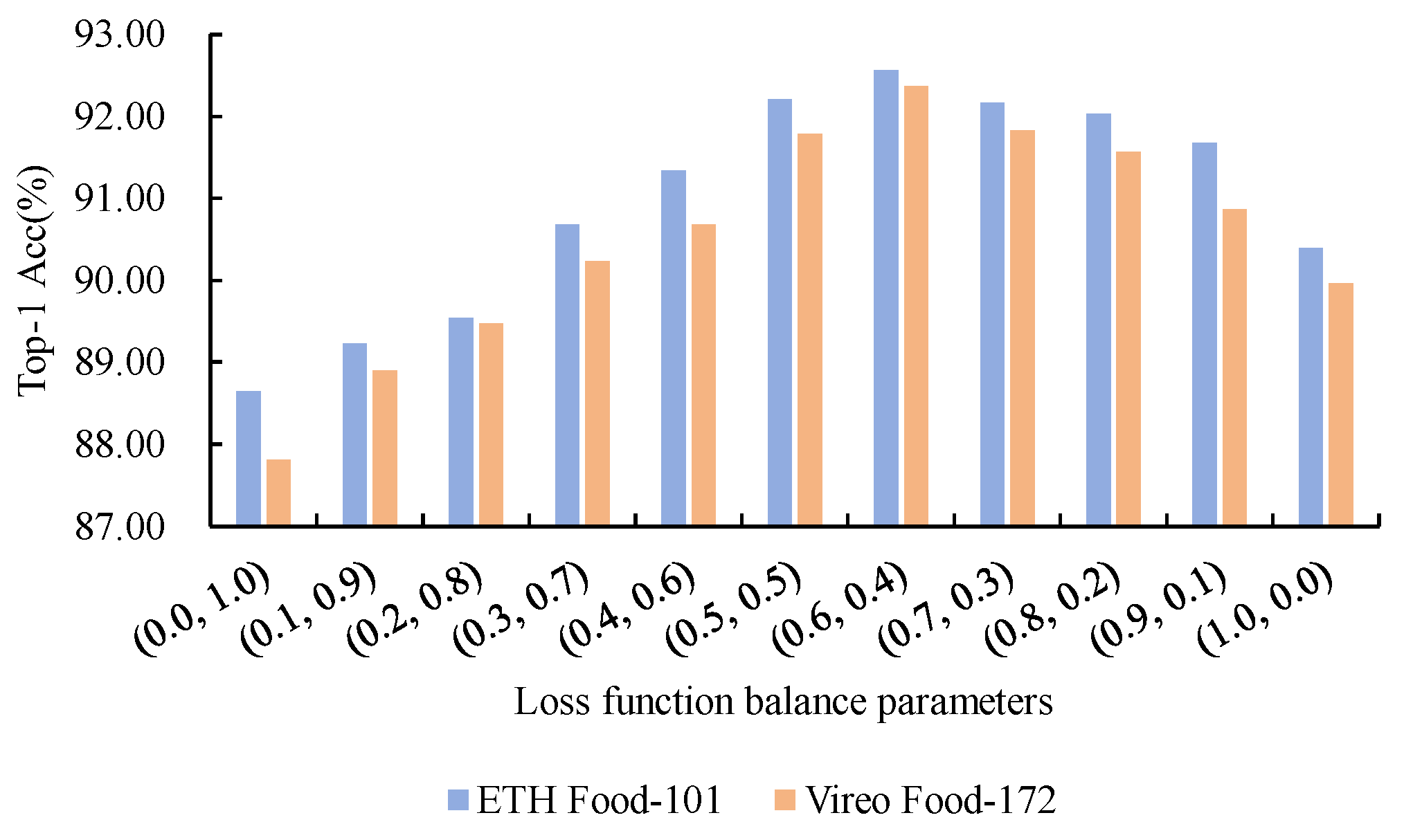

4.3. Comparison with Baselines

4.4. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Zhao, R. Wang, M. Liu, L. Bai, Y. Sun, Application of machine vision in food computing: A review. Food Chemistry 463, 141238 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., Deep learning in food category recognition. Information Fusion 98, 101859 (2023). [CrossRef]

- W. Min, S. Jiang, L. Liu, Y. Rui, R. Jain, A Survey on Food Computing. ACM Comput. Surv. 52, Article 92 (2019). [CrossRef]

- D. Allegra, S. Battiato, A. Ortis, S. Urso, R. Polosa, A review on food recognition technology for health applications. Health Psychol Res 8, 9297 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rostami, N. Nagesh, A. Rahmani, R. Jain, paper presented at the Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop on Multimedia Assisted Dietary Management, Lisboa, Portugal, 2022.

- A. Rostami, V. Pandey, N. Nag, V. Wang, R. Jain, paper presented at the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 2020.

- Ishino, Y. Yamakata, H. Karasawa, K. Aizawa, RecipeLog: Recipe Authoring App for Accurate Food Recording. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, (2021).

- W. Wang et al., A review on vision-based analysis for automatic dietary assessment. Trends in Food Science & Technology 122, 223-237 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. F. Vasiloglou et al., Multimedia Data-Based Mobile Applications for Dietary Assessment. J Diabetes Sci Technol 17, 1056-1065 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Yamakata, A. Ishino, A. Sunto, S. Amano, K. Aizawa, paper presented at the Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 2022.

- K. Nakamoto, S. Amano, H. Karasawa, Y. Yamakata, K. Aizawa, paper presented at the Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Multimedia for Cooking, Eating, and related APPlications, Lisboa, Portugal, 2022.

- Y. Zhu, X. Zhao, C. Zhao, J. Wang, H. Lu, Food det: Detecting foods in refrigerator with supervised transformer network. Neurocomputing 379, 162-171 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M. S. I. Mazumder, E. K. Saha, S. T. Razzaque, S. Chowdhury, paper presented at the Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing Advancements, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020.

- E. Aguilar, B. Remeseiro, M. Bolaños, P. Radeva, Grab, Pay, and Eat: Semantic Food Detection for Smart Restaurants. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 20, 3266-3275 (2018). [CrossRef]

- D. Peng et al., Defects recognition of pine nuts using hyperspectral imaging and deep learning approaches. Microchemical Journal 201, 110521 (2024). [CrossRef]

- G. Sheng et al., A Lightweight Hybrid Model with Location-Preserving ViT for Efficient Food Recognition. Nutrients. 2024 (10.3390/nu16020200). [CrossRef]

- H. Wang et al., Nutritional composition analysis in food images: an innovative Swin Transformer approach. Front Nutr 11, 1454466 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. S. Alahmari, M. R. Gardner, T. Salem, Attention guided approach for food type and state recognition. Food and Bioproducts Processing 145, 1-10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. E. Sreedharan, G. N. Sundar, D. Narmadha, NutriFoodNet: A High-Accuracy Convolutional Neural Network for Automated Food Image Recognition and Nutrient Estimation. Traitement du Signal 41, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, C. Shen, A. Van Den Hengel, Wider or deeper: Revisiting the resnet model for visual recognition. Pattern recognition 90, 119-133 (2019).

- L. Bossard, M. Guillaumin, L. Van Gool, in Computer Vision – ECCV 2014, D. Fleet, T. Pajdla, B. Schiele, T. Tuytelaars, Eds. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2014), pp. 446-461.

- Chen, C.-w. Ngo, paper presented at the Proceedings of the 24th ACM international conference on Multimedia, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- M. Wong, L. M. Po, K. W. Cheung, in 2007 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing. (2007), vol. 6, pp. VI - 365-VI - 368.

- Bosch, F. Zhu, N. Khanna, C. J. Boushey, E. J. Delp, in 2011 19th European Signal Processing Conference. (2011), pp. 764-768.

- Y. He, C. Xu, N. Khanna, C. J. Boushey, E. J. Delp, in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). (2014), pp. 2744-2748.

- D. G. Lowe, Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. International Journal of Computer Vision 60, 91-110 (2004). [CrossRef]

- P. F. Felzenszwalb, Representation and detection of deformable shapes. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 27, 208-220 (2005).

- S. Yang, M. Chen, D. Pomerleau, R. Sukthankar, in 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. (2010), pp. 2249-2256.

- H. Hoashi, T. Joutou, K. Yanai, in 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia. (2010), pp. 296-301.

- Shah, H. Bhavsar, Depth-restricted convolutional neural network—a model for Gujarati food image classification. The Visual Computer 40, 1931-1946 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y.-C. Liu, D. D. Onthoni, S. Mohapatra, D. Irianti, P. K. Sahoo, Deep-Learning-Assisted Multi-Dish Food Recognition Application for Dietary Intake Reporting. Electronics. 2022 (10.3390/electronics11101626). [CrossRef]

- Wang et al., Application of Convolutional Neural Network-Based Detection Methods in Fresh Fruit Production: A Comprehensive Review. Front Plant Sci 13, 868745 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. Dabov, A. Foi, V. Katkovnik, K. Egiazarian, Image Denoising by Sparse 3-D Transform-Domain Collaborative Filtering. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 16, 2080-2095 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Dong, D. Zhang, G. Shi, Two-stage image denoising by principal component analysis with local pixel grouping. Pattern Recognition 43, 1531-1549 (2010). [CrossRef]

- J. Liang et al., in 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW). (2021), pp. 1833-1844.

- J. Ho, A. Jain, P. Abbeel, Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 6840-6851 (2020).

- G. Xu et al., ASQ-FastBM3D: An Adaptive Denoising Framework for Defending Adversarial Attacks in Machine Learning Enabled Systems. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 72, 317-328 (2023). [CrossRef]

- R. Kundu, A. Chakrabarti, P. Lenka, A Novel Technique for Image Denoising using Non-local Means and Genetic Algorithm. National Academy Science Letters 45, 61-67 (2022). [CrossRef]

- P. McAllister, H. Zheng, R. Bond, A. Moorhead, Combining deep residual neural network features with supervised machine learning algorithms to classify diverse food image datasets. Computers in Biology and Medicine 95, 217-233 (2018). [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, J. Wu, Y. Yang, Wi-HSNN: A subnetwork-based encoding structure for dimension reduction and food classification via harnessing multi-CNN model high-level features. Neurocomputing 414, 57-66 (2020). [CrossRef]

- G. Huang, Z. Liu, L. V. D. Maaten, K. Q. Weinberger, in 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2017), pp. 2261-2269.

- J. Hu, L. Shen, G. Sun, in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. (2018), pp. 7132-7141.

- J. Qiu, F. P.-W. Lo, Y. Sun, S. Wang, B. P. L. Lo, in British Machine Vision Conference. (2019).

- Y. Chen, Y. Bai, W. Zhang, T. Mei, in 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2019), pp. 5152-5161.

- R. Du et al., in Computer Vision – ECCV 2020, A. Vedaldi, H. Bischof, T. Brox, J.-M. Frahm, Eds. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020), pp. 153-168.

- T. Hu, H. Qi, Q. Huang, Y. Lu, See better before looking closer: Weakly supervised data augmentation network for fine-grained visual classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.09891, (2019).

- Z. Yang et al., in Computer Vision – ECCV 2018, V. Ferrari, M. Hebert, C. Sminchisescu, Y. Weiss, Eds. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018), pp. 438-454.

- W. Min et al., Large Scale Visual Food Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 45, 9932-9949 (2023).

- W. Min et al., paper presented at the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 2020.

- Z. Liu et al., in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. (2021), pp. 10012-10022.

- Z. Xia, X. Pan, S. Song, L. E. Li, G. Huang, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. (2022), pp. 4794-4803.

- Z. Wang et al., Ingredient-Guided Region Discovery and Relationship Modeling for Food Category-Ingredient Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 31, 5214-5226 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, W. Min, S. Jiang, Y. Rui, Convolution-Enhanced Bi-Branch Adaptive Transformer With Cross-Task Interaction for Food Category and Ingredient Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 33, 2572-2586 (2024). [CrossRef]

- W. Park, D. Kim, Y. Lu, M. Cho, in 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2019), pp. 3962-3971.

- Peng et al., Correlation Congruence for Knowledge Distillation. 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 5006-5015 (2019).

- Y. Liu et al., in 2019 IEEE/CV activation boundaries formed F Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2019), pp. 7089-7097.

- Heo, M. Lee, S. Yun, J. Y. Choi, in Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence. (2019), vol. 33, pp. 3779-3787.

- P. Dhar, R. V. Singh, K. C. Peng, Z. Wu, R. Chellappa, in 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2019), pp. 5133-5141.

- Q. Wang et al., paper presented at the Neural Information Processing: 29th International Conference, ICONIP 2022, Virtual Event, November 22–26, 2022, Proceedings, Part I, New Delhi, India, 2023.

- Xu et al., Teacher-student collaborative knowledge distillation for image classification. Applied Intelligence 53, 1997-2009 (2023). [CrossRef]

| Method | Backbone | ETH Food-101 | Vireo Food-172 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top-1 acc | Top-5 acc | Top-1 acc | Top-5 acc | ||

| ResNet152+SVM-RBF [39] | ResNet152 | 64.98 | - | - | - |

| FS_UAMS[40] | Inceptionv3 | - | - | 89.26 | - |

| ResNet50[20] | ResNet50 | 87.42 | 97.40 | - | - |

| DenseNet161[41] | DenseNet161 | - | - | 86.98 | 97.31 |

| SENet-154[42] | ResNeXt-50 | 88.68 | 97.62 | 88.78 | 97.76 |

| PAR-Net[43] | ResNet101 | 89.30 | - | 89.60 | - |

| DCL[44] | ResNet50 | 88.90 | 97.82 | - | - |

| PMG[45] | ResNet50 | 86.93 | 97.21 | - | - |

| WS-DAN[46] | Inceptionv3 | 88.90 | 98.11 | - | - |

| NTS-NET[47] | ResNet50 | 89.40 | 97.80 | - | - |

| PRENet[48] | ResNet50 | 89.91 | 98.04 | - | - |

| PRENet[48] | SENet154 | 90.74 | 98.48 | - | - |

| SGLANet[49] | SENet154 | 89.69 | 98.01 | 90.30 | 98.03 |

| Swin-B[50] | Transformer | 89.78 | 97.98 | 89.15 | 98.02 |

| DAT[51] | Transformer | 90.04 | 98.12 | 89.25 | 98.12 |

| EHFR-Net[16] | Transformer | 90.70 | - | 90.30 | - |

| IVRDRM[52] | ResNet-101 | 92.36 | 98.68 | 93.33 | 99.15 |

| SICL(CBiAFormer-T)[53] | Swin-T | 91.11 | 98.63 | 90.70 | 98.05 |

| SICL(CBiAFormer-B)[53] | Swin-B | 92.40 | 98.87 | 91.58 | 98.75 |

| Our method | ResNet50 | 92.57 | 98.70 | 92.37 | 98.55 |

| ETH Food-101 | Vireo Food-172 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p1 | p2 | p3 | Top-1 | p1 | p2 | p3 | Top-1 | |

| SFF | 86.43 | 87.23 | 86.79 | 87.86 | 82.87 | 86.12 | 85.72 | 86.63 |

| SFF+NARM(no EGCP) | 87.73 | 88.36 | 88.97 | 90.31 | 86.58 | 87.65 | 88.67 | 89.72 |

| SFF+NARM | 89.25 | 90.80 | 91.23 | 92.19 | 88.23 | 89.82 | 91.10 | 91.88 |

| SFF+NARM+WMF | 89.77 | 91.27 | 92.03 | 92.57 | 88.69 | 90.03 | 91.59 | 92.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).