Introduction

During the Industrial Revolution, as the world experienced profound economic, social, and technological transformations, educational models adapted to meet the demands of the time, seeking effective ways to transmit knowledge (Hobsbawm, 2010). From a simplified perspective, education can be understood as a process of growth that unfolds within the time frame of a single lesson, where the goal is to organize and structure the various elements that influence teaching from the teacher's perspective to the students. This topic was first debated nearly 30 years ago, because of the diversity of pedagogical approaches. The increased use of the internet has eliminated barriers between countries and continents, enabling people to connect and communicate with others across the globe an evolution that has had a significant and positive impact on education (Downes, 2022).

The internet has helped to overcome historical educational challenges by providing instant access to information and learning resources from anywhere in the world, allowing students and educators to benefit from diverse and up-to-date knowledge. It has also enabled international collaboration and the exchange of ideas among scholars, researchers, and students, thus contributing to the global advancement of knowledge (Harasim, 2017; Selwyn, 2014). This digital transformation has revolutionized the educational landscape by making knowledge more accessible, diverse, and collaborative—transcending barriers and facilitating adaptation to contemporary educational models (Bonk, 2009; Garrison, 2016). The COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in education, forcing institutions to innovate and adopt new teaching methods based on virtual environments, digital technologies (ICTs), and approaches such as Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), now increasingly recognized as part of educational neuroscience (Burgos et al., 2020; Hodges et al., 2020).

Teachers are now required to integrate multiple strategies to keep students engaged and focused, including the use of interactive online tools, virtual learning platforms, and neuroscience-based techniques to enhance retention and comprehension. ICTs are essential in adapting educational content to better resonate with students’ cognitive and emotional capacities (Mayer, 2002; Moreno & Mayer, 2007). The ability of most individuals to create and share videos, written lessons, and other educational content online represents a major revolution in education. It allows direct contributions to the education of children and young people who may live thousands of kilometers away. In this sense, the emergence of a global knowledge network has created vast learning opportunities regardless of geographic location, or social and economic barriers (Anderson, 2008).

Such networks enable educators and experts to share best practices and collaborate on educational projects internationally, strengthening both professional development and innovation within the field. The ability to share instructional content online has the potential to profoundly transform education by making it more accessible, inclusive, and adaptable to individual and global learning needs (Moreno & Mayer, 2007). This study explores the perceptual challenges affecting the educational process in chemistry, aiming to improve learning outcomes through the integration of ICTs into EI for teaching the subject. The proposed approach involves the use of emotionally engaging tools designed to enhance student interest and motivation toward knowledge acquisition, building upon prior studies involving the use of ICTs in chemistry education (Basurto Santos & Lescay Blanco, 2023; Castillo et al., 2013; Cataldi et al., 2009, 2010; Hurtado & Guerrero, 2020; Merino et al., 2015; Proszek & Ferreira, 2009).

The goal is to harness the enthusiasm and skill of teachers to effectively deliver this content (Grossman & Richert, 1988; Hattie, 2013). The research question to be answered by the end of this study is: Did the use of ICTs integrated with EI in chemistry instruction increase students’ interest and motivation toward acquiring new knowledge?

The teaching-learning process is a complex phenomenon involving dynamic interaction between two participants, one who teaches and one who learns. Regardless of context, education can be understood as a form of socialization in which individuals engage with a particular subject to acquire knowledge and thereby foster effective social interaction within their community (Charlot, 2008).

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

Chemistry is a science of learning that integrates teaching theory, research, explanation, and problem-solving as a core structure, often delivered through formulas and instructional materials provided by the teacher to enhance student understanding and adaptation. Effective chemistry education requires subject-specialized teachers capable of facilitating the comprehension of environmental phenomena through connections to everyday life, supported by experimental practices in the laboratory (Castillo et al., 2013). Understanding the educational phenomenon entails analyzing the concepts of education, teaching, and learning. Education is conceived as a holistic process aimed at the individual's comprehensive development. According to (Martínez-Izaguirre et al., 2018), "education is a multidimensional process encompassing cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions with the goal of forming competent and engaged citizens" (p. 103).

Teaching refers to the intentional action of the educator in facilitating the construction of knowledge. As (Gómez-Hurtado et al., 2018), state, "effective teaching involves selecting and applying pedagogical strategies that promote active and meaningful learning" (p. 56). In contrast, learning is the process through which the student acquires and modifies knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Alonso-García et al., 2019), assert that "learning is a constructive process requiring student engagement and the integration of new knowledge with existing frameworks" (p. 78).

The alignment of objectives, content, and methodology is critical for the success of the teaching-learning process. Educational objectives define the intended outcomes; content represents the knowledge to be transmitted; and methodology includes the strategies used to facilitate learning (Pérez-López & Rivera, 2017) emphasize that "coherent alignment between objectives, content, and methods is essential for achieving meaningful and lasting learning outcomes" (p. 92). Thus, educational planning must include clearly defined goals, structured content, and appropriate methodologies to ensure effective knowledge transfer from teacher to learner. Chemistry instruction allows students to appreciate the subject’s applications in both theoretical and practical contexts, developing cognitive skills and strong foundational knowledge (Pinto-Llorente et al., 2017; Sáiz-Manzanares et al., 2020).

ICTs and EI, the integration of EI into chemistry instruction can improve educational experience by promoting motivational practices that help students regulate their emotional responses while learning. EI involves the ability to identify, understand, manage, and use emotions effectively—both personally and interpersonally—resulting in positive effects on learning and personal development (Velásquez-Pérez et al., 2023). Chemistry requires not only cognitive skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving but also emotional competencies essential for effective learning. The abstract and complex nature of the subject often induces stress, frustration, and anxiety. Developing EI within this context can enhance both academic performance and student well-being. As (Hacienminoglu, 2016) notes, "implementing emotional regulation strategies in chemistry classrooms can reduce anxiety and improve academic performance" (p. 503). Techniques such as mindful breathing and positive visualization may be effective tools for managing stress during lab experiments or exams. Teachers must plan classroom activities that allow short relaxation breaks, enabling emotional regulation and stress management. Skills such as emotional self-regulation and mindfulness can be integrated into the classroom to help students remain calm and focused (Páez Cala & Castaño Castrillón, 2015).

Self-efficacy is a critical component of learning in chemistry. (Villafañe et al., 2016) state, "the development of EI can enhance students' self-efficacy in chemistry, which in turn improves motivation and persistence in the face of academic challenges" (p. 731). Strategies such as setting realistic goals and celebrating small achievements can strengthen self-efficacy—the belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific tasks. To promote motivation and self-efficacy, teachers should scaffold learning from simple to complex. Emotionally competent students are more likely to persevere, maintain a positive learning attitude, and remain resilient when facing difficulties (Lambropoulos et al., 2012).

The integration of ICTs into the development of EI within chemistry education provides an innovative response to pedagogical challenges. Chemistry, as a cognitively demanding and emotionally complex subject, benefits significantly from teaching strategies that support collaboration, emotional regulation, and student engagement. Collaborative work in laboratories is a core component of chemistry learning. EI plays a vital role in group performance by enhancing communication and conflict resolution (Cleophas et al., 2023; Sandi-Urena et al., 2012).

Teachers should foster emotionally supportive learning environments that encourage empathy and interpersonal development, reinforcing resilience in the face of academic difficulties (Bhurtun et al., 2011; Ramsami & King, 2020). Reflective practices, such as personal journals and group discussions, can help students identify and manage their emotions related to complex chemistry topics. Project-based learning offers meaningful opportunities to merge emotional and cognitive development. When chemistry projects incorporate EI components, students show improvements in motivation, teamwork, and self-regulation (Aivaloglou & Hermans, 2019). Emotionally charged settings such as lab assessments, regulation techniques like mindfulness and deep breathing can significantly reduce stress and anxiety (Muñoz-Osuna et al., 2016).

Communication is another area, especially in laboratory environments. Developing emotional communication skills supports collaborative work, improves the quality of scientific dialogue, and strengthens students’ confidence in presenting results (Lambropoulos et al., 2012). Creating emotionally safe classrooms allows students to express concerns, increasing engagement and enjoyment in chemistry learning (Ritchie & Tobin, 2018). Digital tools enhance emotional engagement in chemistry through immersive technologies and interactive learning environments. ICTs enable synchronous and asynchronous interaction through web platforms (Basurto Santos & Lescay Blanco, 2023), and support soft skill development such as empathy, emotional self-awareness, and emotional regulation (Hernandez, 2017).

Virtual simulations and augmented reality (AR) allow students to visualize molecular structures and reaction mechanisms in ways not possible in traditional settings, increasing conceptual understanding and emotional involvement (Díaz et al., 2018; Merino et al., 2015). Gamification elements, such as ChemCaper and Alchemie, increase student engagement by integrating academic content with motivational game mechanics. These tools promote emotional growth by enhancing collaboration, communication, and feedback (Pérez-López & Rivera, 2017; Mendoza-Zambrano et al., 2023). Educational games and virtual simulations are especially effective for reducing anxiety and enhancing student satisfaction through safe experimentation (Proszek & Ferreira, 2009).

Collaborative learning platforms like Moodle and Google Classroom support teamwork and collective EI by enabling students to co-construct knowledge and manage group dynamics (Cabero-Almenara & Llorente-Cejudo, 2020a; Hurtado & Guerrero, 2020). Self-assessment tools such as Kahoot and Quizzes help students reflect on their learning progress while encouraging emotional self-regulation (Gros Salvat & Cano García, 2021; Pinto-Llorente et al., 2017).

Online forums and blogs provide platforms for emotional expression and peer support. These tools facilitate critical reflection and collective knowledge building in a low-pressure environment (García-Peñalvo et al., 2011; Ornelas Gutiérrez, 2007). Videoconferencing and virtual debates also promote empathy, active listening, and shared reasoning in chemistry discussions (Montenegro & Nodarse, 2017). Finally, digital portfolios and journals promote metacognitive reflection and emotional awareness. These tools provide long-term documentation of academic and personal growth, reinforcing self-regulation and motivation in chemistry learners (Abadal et al., 2017).

2. METHODS

This study employed a mixed-methods approach with a descriptive and diagnostic scope to explore the integration of ICTs and EI in university-level chemistry instruction. The objective was to assess the current state of pedagogical practices, emotional competencies, and student motivation, and to analyze the impact of an EI, ICT-based intervention on the teaching-learning process.

Phase 1: Diagnostic assessment of university chemistry teachers structured questionnaire to collect data on their knowledge, attitudes, and training regarding ICT use and the application of EI strategies in their teaching practice.

Phase 2: Diagnostic assessment of students (pre-intervention) with a survey to explore their awareness of EI, the perceived emotional climate of the classroom, and the frequency and effectiveness of ICT use in chemistry instruction to identify emotional and motivational states before the application of strategies.

Phase 3: Student satisfaction survey (post-intervention) after the implementation of a chemistry lesson that integrated ICT tools and EI-based strategies. This survey evaluated perceptions of motivation, emotional engagement, clarity of concepts, and effectiveness of the teaching strategies used.

2.1. Sample

Participants, a total of 7 university chemistry teachers participated in Phase 1. For Phases 2 and 3, the sample consisted of 172 undergraduate chemistry students enrolled in general and basic chemistry courses at a higher education institution with voluntary participation.

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

Instruments, three instruments were used for data collection: a teacher questionnaire, including Likert-type and open-ended items, designed to evaluate ICT integration, emotional teaching strategies, and perceived training needs. A student diagnostic survey, applied prior to the intervention, focused on perceptions of EI, frequency of ICT uses in chemistry, and classroom climate. A post-class student satisfaction survey, which assessed the impact of the EI, ICT-based chemistry lesson on student engagement, motivation, and content understanding.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data Analysis, quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages) and visualized through bar charts. The results provided insights into the initial diagnostic status of both teachers and students and enabled a comparative interpretation of the impact after the class intervention. Qualitative comments from the open-ended items were also reviewed thematically to enrich the interpretation of the quantitative findings.

3. RESULTS

The diagnostic phase applied to university chemistry professors

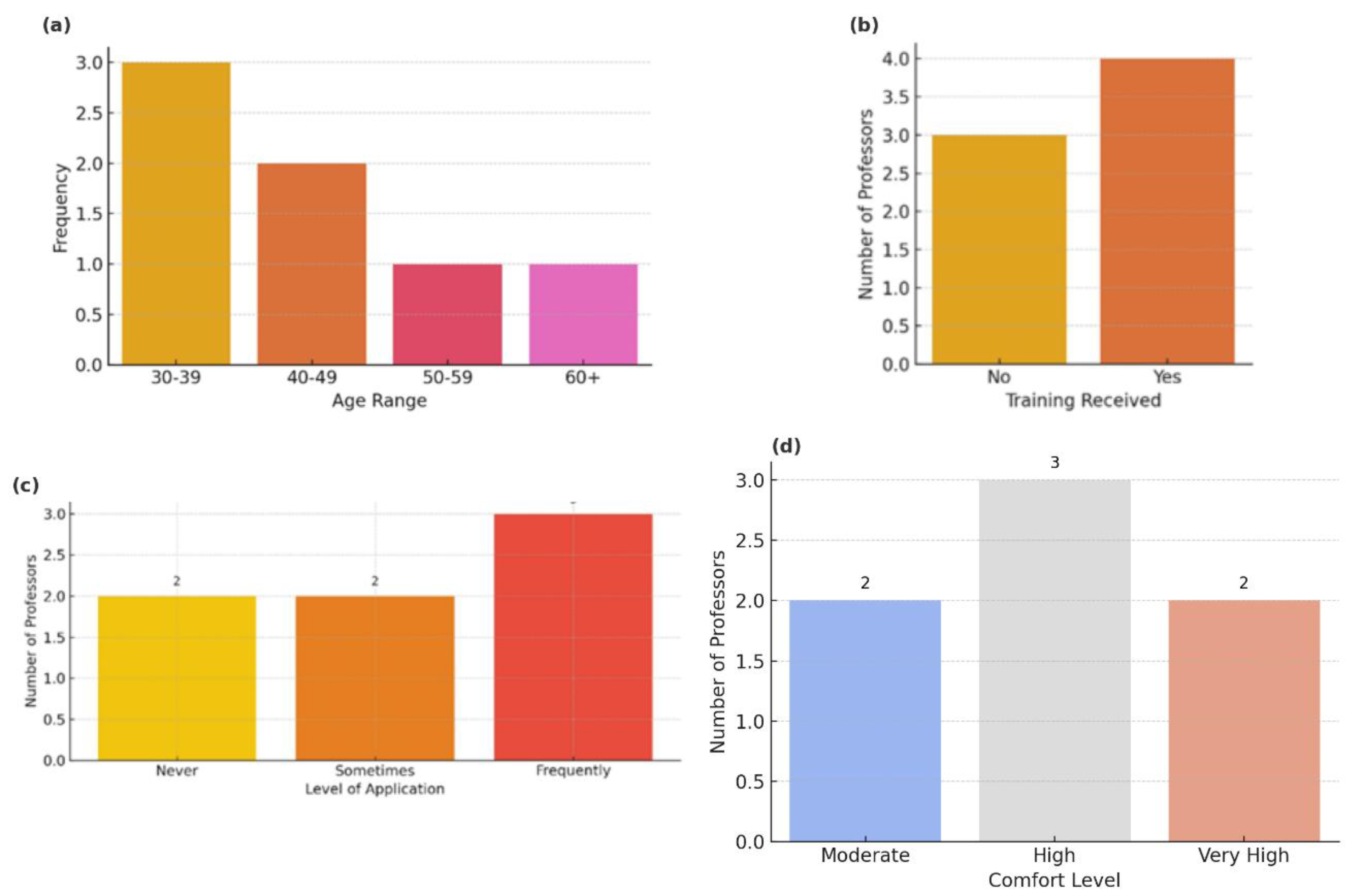

Figure 1 presents a combined visualization of diagnostic indicators related to university chemistry professors’ demographic and pedagogical profiles.

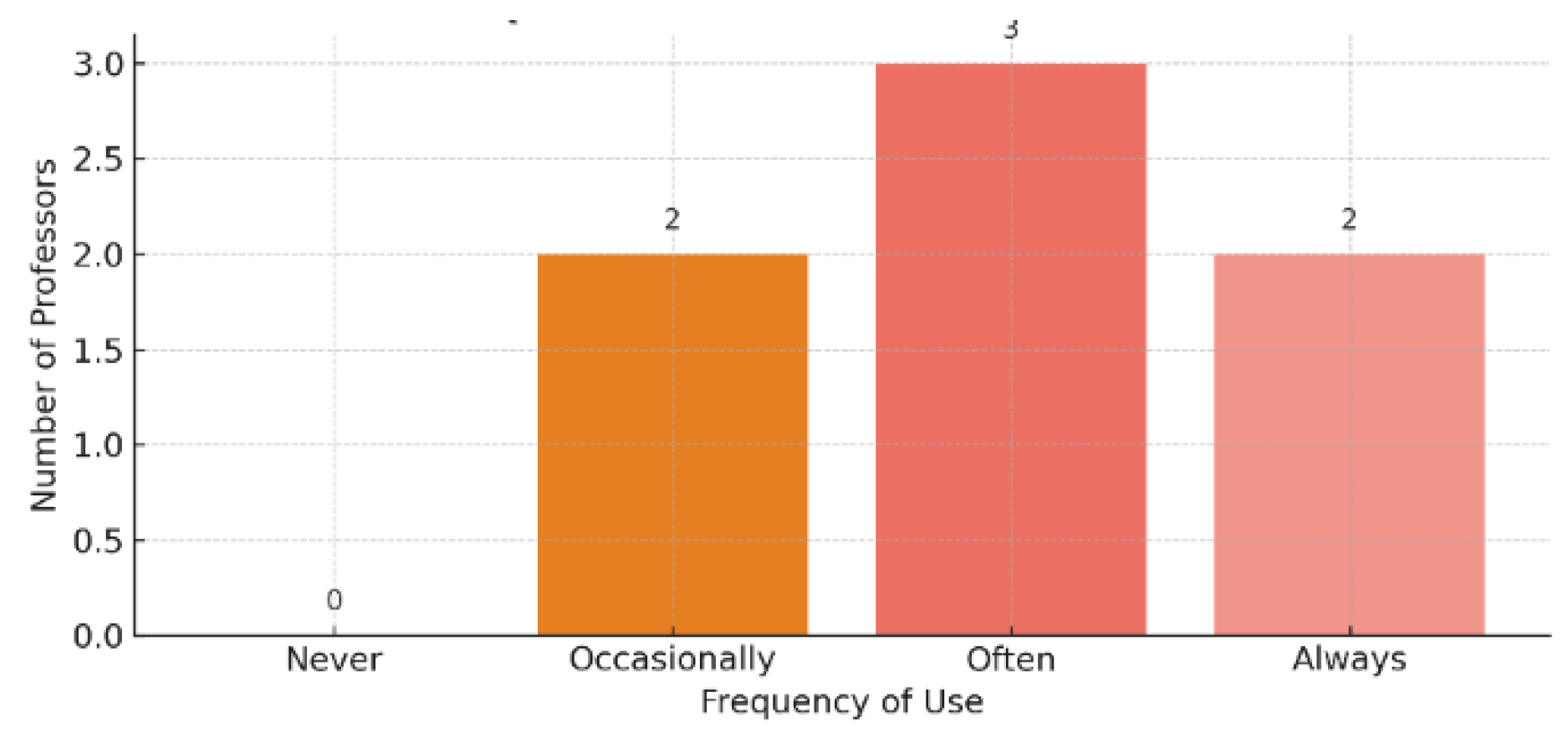

Figure 2 shows the frequency with which professors use ICTs in their chemistry classes, allowing for the identification of the level of technological integration in the teaching-learning processes within this discipline.

Subfigure (a) displays the age distribution of participating professors, which provides contextual insight into their generational exposure to digital technologies and emotional pedagogy. Subfigure (b) illustrates the training received on ICTs and EI, highlighting heterogeneous levels of preparedness to implement emotionally responsive and digitally mediated strategies. Subfigure (c) reveals the frequency with which professors incorporate EI strategies into their teaching practice, showing that only a minority apply such approaches regularly. Lastly, subfigure (d) shows professors’ comfort level with ICTs, indicating moderate to high confidence in using digital tools, yet suggesting that familiarity does not always translate into pedagogical innovation. These findings underscore the necessity for targeted professional development programs that integrate emotional competencies with digital pedagogy to enhance the teaching.

The initial diagnostic evaluation to students

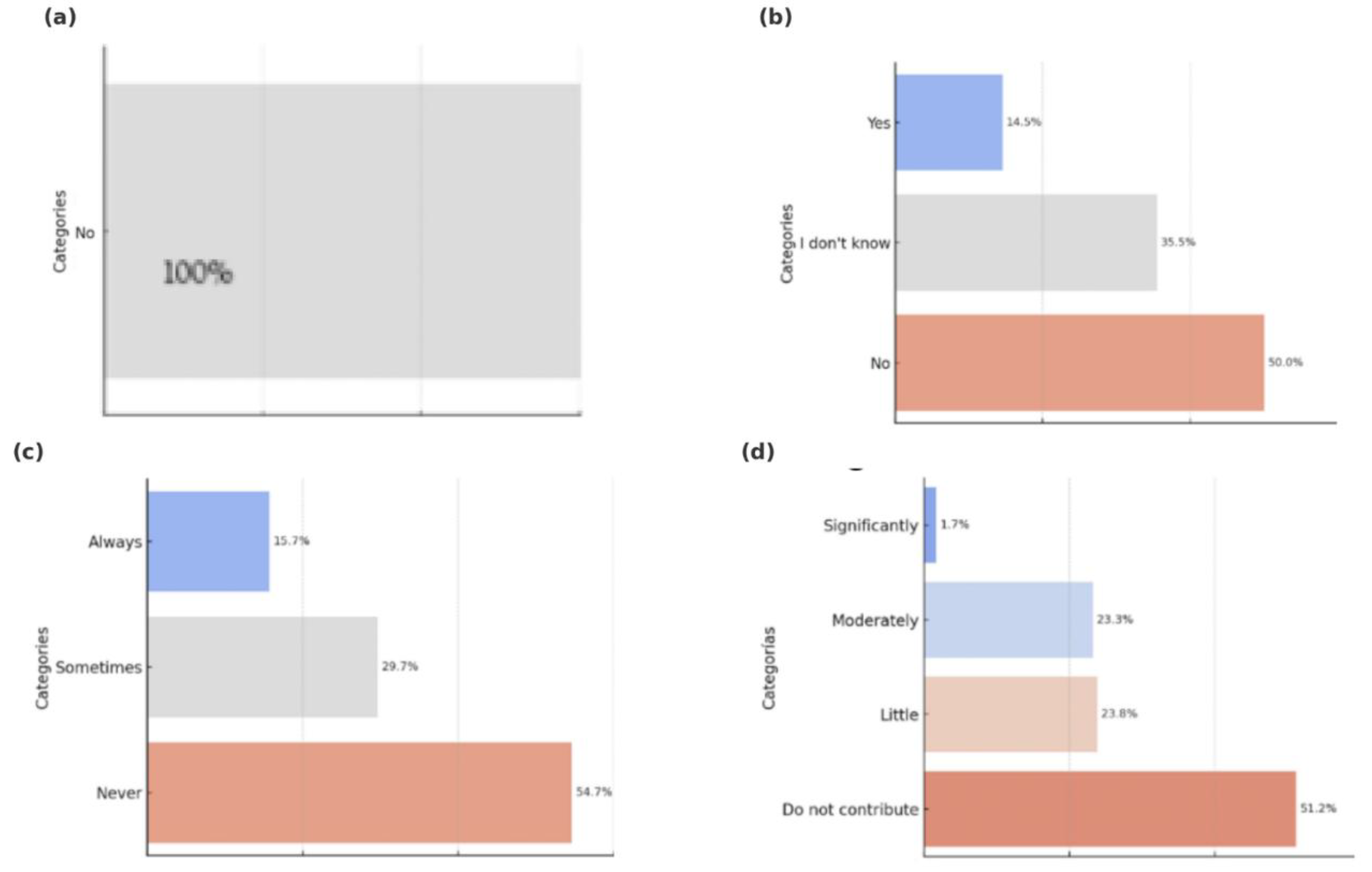

Figure 3 presents student responses regarding emotional intelligence (EI) and the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in chemistry classes. In subfigure (a), all students reported being unfamiliar with the concept of EI. Subfigure (b) shows that only a small percentage believed their professors were trained to implement ICT-based emotional strategies. Subfigure (c) indicates that most students perceived little to no use of ICTs in their chemistry classes. Finally, subfigure (d) displays students’ perceptions of the contribution of ICTs to emotional development, with most responses indicating a low or null perceived impact.

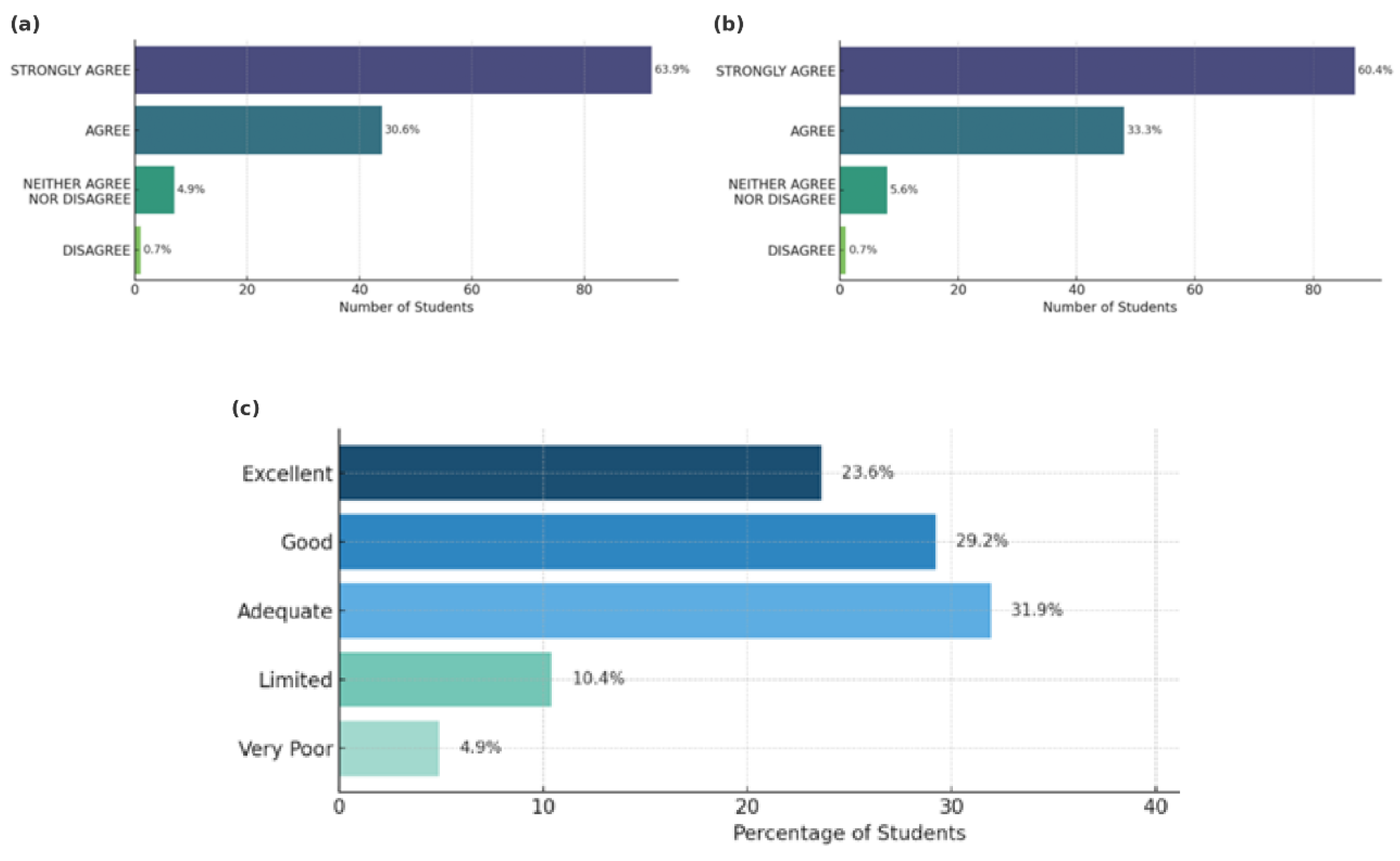

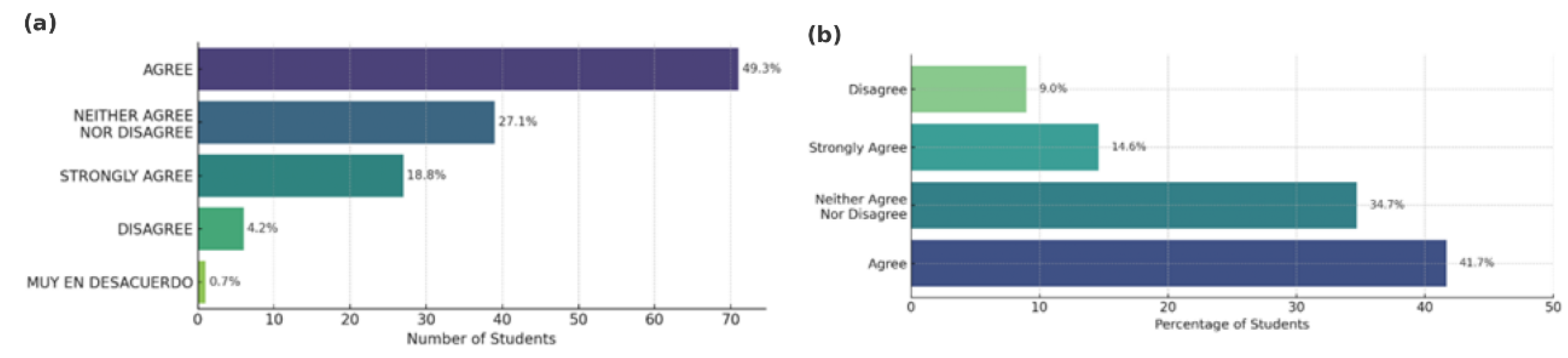

Figure 4 presents student responses following the intervention. Subfigure (a) shows the reported desire to learn all subjects with motivation. Subfigure (b) displays students’ perceptions of the impact of a motivating methodology on their class attendance. Subfigure (c) presents student ratings of classroom activities that integrated ICT and emotional strategies.

The post-implementation evaluation of motivation

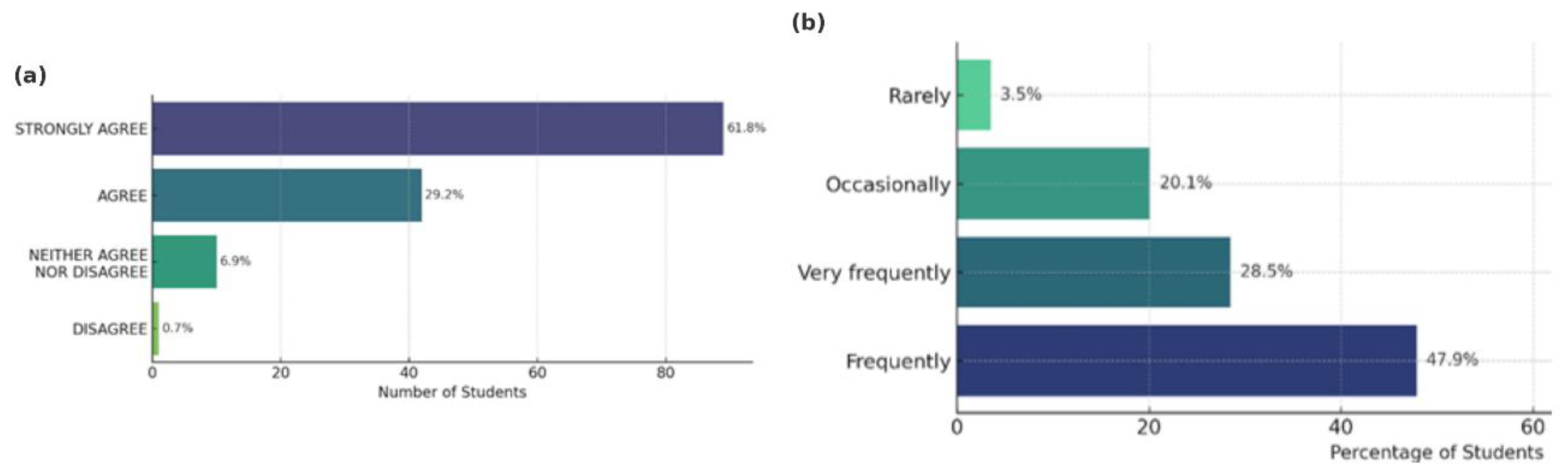

Figure 5 presents student responses related to engagement during the intervention. Subfigure (a) displays students’ perceived concentration level during classes that incorporated ICT and emotional strategies. Subfigure (b) shows their perception of the teacher’s ability to maintain curiosity and interest throughout the session.

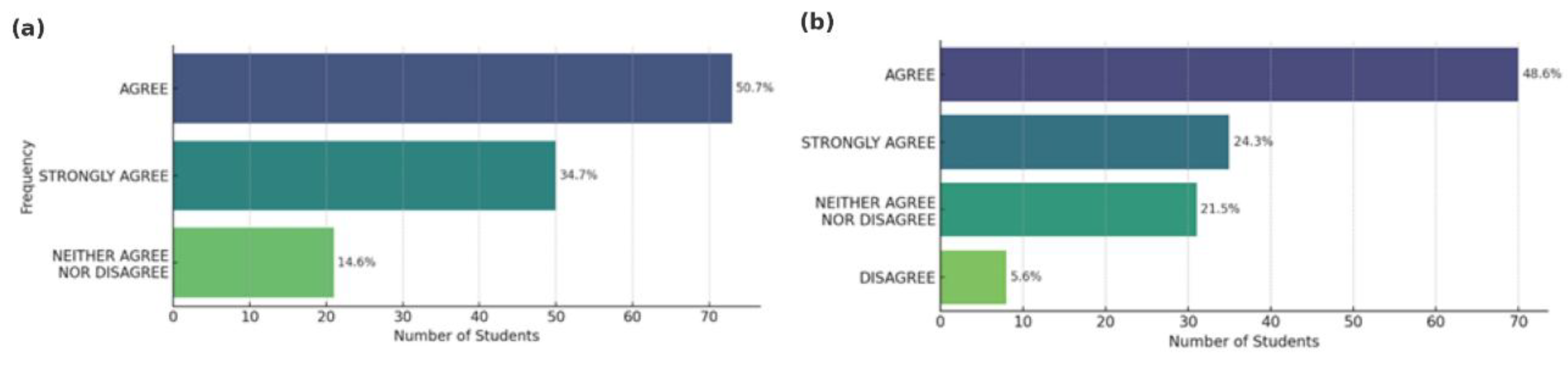

Figure 6 presents student perceptions regarding the emotional and motivational aspects of the intervention. Subfigure (a) shows their views on how mood influences learning outcomes. Subfigure (b) displays their perception of whether the applied methodology stimulated their curiosity during class.

Figure 7 presents student responses related to motivation in the chemistry learning environment. Subfigure (a) shows their perception of how teacher motivation influences the learning process. Subfigure (b) reflects students’ self-reported motivation to study chemistry following the implementation of ICT- and EI-based strategies

4. DISCUSSION

The diagnostic phase applied to university chemistry professors

A significant portion of the faculty had received some training in the use of ICTs and EI strategies; there remains a clear lack of systematic integration of both approaches in their teaching practices. Of the seven instructors surveyed, four reported having ICT knowledge and using digital tools frequently or regularly in their classes. This finding aligns with the study by Cabero-Almenara & Llorente-Cejudo, (2020), who reported an increasing level of digital proficiency among university faculty, especially following the expansion of hybrid and virtual learning environments in the post-pandemic era. However, as (Area-Moreira, 2018) warns, technical knowledge does not necessarily translate into pedagogical innovation unless accompanied by a reflective and intentional instructional design.

Regarding comfort levels with ICTs, most professors reported feeling moderately to highly confident using these tools, consistent with the findings of (Ramírez-Montoya & García-Peñalvo, 2019), who highlight the progressive development of digital self-efficacy among educators. Nevertheless, the use observed in this study was largely instrumental or technical rather than pedagogical or emotionally driven. This reinforces the position of (Gisbert & Esteve, 2016), who emphasize the importance of moving beyond functional usage towards transformative and emotionally responsive integration of digital technologies.

The integration of EI into the classroom remains limited. Only three professors reported applying emotional strategies regularly, indicating a lack of implementation of EI in the context of science teaching. This outcome echoes (Bisquerra, 2011), who asserts that teacher training programs have yet to fully incorporate emotional competencies as part of their curricula. Similarly, (Martínez-Izaguirre et al., 2018) points out that while many educators acknowledge the importance of EI for student well-being and academic performance, they often lack concrete strategies to implement it effectively.

Moreover, four out of the seven professors surveyed indicated that they had not received any specific training in using ICTs to support emotional development. This corroborates the observations of (Salinas et al., 2022), who argue that teacher training programs rarely address the emotional dimension as an integral component of technological literacy. Consequently, there is a clear demand for workshops, courses, and didactic resources that intentionally integrate ICTs with emotional development.

Unlike broader studies with generalizable samples, this research focuses on a small group of chemistry professors, offering a nuanced perspective on a discipline where emotional dimensions have traditionally been marginalized. In line with (Pozo et al., 2020), integrating EI into science can enhance motivation, academic persistence, and meaningful learning. Therefore, this diagnostic phase provides a solid foundation for the design of future pedagogical interventions that blend emotional strategies with technological innovation. While the findings confirm prior research regarding the widespread adoption of ICTs in higher education, significant gaps remain in their emotional and pedagogical application. This represents a strategic opportunity to strengthen teacher training programs, particularly in science fields such as chemistry, where EI, when combined with digital tools, can serve as a powerful mediator of the learning process.

The initial diagnostic evaluation to students

A critical finding was that 100% of the students reported being unfamiliar with the concept of EI, indicating a complete lack of exposure to academic success—particularly in cognitively demanding subjects such as chemistry. This result aligns with the foundational work of (Goleman, 1995) and (Bisquerra, 2011), who assert that EI plays a vital role in motivation, stress regulation, and openness to learning.

Further insights from the diagnostic phase suggest a notable disconnect between students and emotionally aware pedagogical practices. When asked about their perception of whether teachers were trained in using ICTs to support emotional strategies, 50% responded negatively, and 35.5% indicated uncertainty. Only 14.5% believed their professors were adequately trained. This scenario reflects not only a lack of formal teacher training but also a general invisibility of emotionally oriented educational practices. Similar observations were made by (Ramírez-Montoya & García-Peñalvo, 2019), who emphasized the need for continuous teacher development in digital and emotional competencies.

The analysis also revealed a low frequency of ICT integration in chemistry classes. Over half of the students (54.7%) reported that ICTs were "never" used in class, while 29.7% stated they were used "occasionally," and only 15.7% indicated consistent usage. These figures point to a limited application of digital tools, which contrasts with international standards and best practices for technology-enhanced science education. Studies such as those by (Cabero-Almenara & Llorente-Cejudo, 2020b) advocate for the regular implementation of platforms, simulations, and virtual laboratories to enhance scientific learning. From this perspective, the reported frequency of ICT use in the present study is clearly insufficient.

Student perceptions regarding the potential of ICTs to contribute to emotional development further reinforce this concern. Over half (51.2%) of respondents believe that ICTs do not contribute to the development of EI, while 23.8% say they contribute “little” and 23.3% “moderately.” Only a marginal 1.7% perceived a “significant” contribution. These responses suggest that when digital tools are used, they are rarely accompanied by pedagogical approaches that intentionally address students' emotional engagement—highlighting a missed opportunity for more meaningful learning.

Taken together, the data presents a clear picture of disconnection: between the integration of ICTs and emotional development, between instructional strategies and student needs, and between institutional practices and 21st-century educational goals. The findings point to four issues: (1) a general lack of emotional knowledge among students; (2) insufficient teacher training and application of emotionally focused pedagogy; (3) infrequent and superficial use of digital tools in chemistry instruction; and (4) a widespread perception that ICTs, as currently implemented, have no emotional or motivational impact.

These results support the urgent need for comprehensive educational interventions that not only promote digital literacy among teachers but also integrate EI into teaching strategies. Professional development programs must equip educators with the skills to design emotionally engaging and technologically enhanced classroom experiences. Only by bridging the gap between technical and emotional competencies can we create motivating, participatory, and transformative learning environments in science education.

To assess the impact of integrating ICTs with an EI approach in the learning of chemistry, didactic intervention was designed and implemented using the Talents educational platform. This digital tool enabled the development of interactive and emotionally engaging activities focused on the topic of hydrocarbons, a fundamental component of the chemistry curriculum. The intervention incorporated EI-based strategies such as collaborative work, emotional self-regulation, and personal reflection, aiming to enhance student motivation, engagement, and conceptual understanding. The combination of scientific content, participatory dynamics, and digital resources fostered a more active, personalized, and emotionally responsive learning environment.

The post-implementation evaluation of motivation

Revealed limited familiarity with EI and low integration of ICTs in chemistry classes, a set of emotionally focused strategies supported by digital tools was implemented using the Talents platform and interactive activities on hydrocarbon topics.

More than 60% of the students expressed a desire to learn all subjects with greater motivation, and 60.4% stated that a motivating methodology would increase their class attendance. Furthermore, over 80% rated the sessions as adequate, good, or excellent in terms of the use of ICTs and emotionally engaging practices, confirming the effectiveness of the intervention.

Cognitive-emotional engagement improved notably: 49.3% of students reported higher concentration, and 67.3% recognized that the teacher’s emotional state significantly influenced their learning. Curiosity also increased, with 47.9% indicating that the applied methodology frequently sparked their interest and 28.5% noting that it did so very frequently. Importantly, 48.6% of students agreed that their motivation for studying chemistry increased through the combined use of ICTs and EI strategies. These findings align with Cabero-Almenara et al. (2020), who highlighted the capacity of digital tools to improve sustained attention and encourage active participation in higher education. Similarly, emphasized the power of emotional strategies—such as empathy and the creation of positive classroom climates—to facilitate cognitive and emotional readiness in challenging subjects like chemistry (Pozo et al., 2020).

The data also revealed that the students believed that the applied teaching methodology enhanced their curiosity. This reflects the role of inquiry-based learning, which, as suggested by (Bruner, 1999) and (Biggs et al., 2022), is to fostering critical thinking and conceptual understanding. The integration of virtual labs, simulations, and gamified elements described by (Moya et al., 2022). Evaluation of the teaching sessions revealed that 72% rated the approach as good or excellent, reflecting strong student satisfaction with the integration of technology and emotional development. These results reinforce the arguments of (Gisbert & Esteve, 2016) argue that true educational innovation requires connecting technological tools with affective dimensions. Similarly, (Castaño-Muñoz et al., 2018) found that combining ICTs with EI promotes flexible, student-centered, and emotionally supportive learning environments.

Students confirmed that the teacher’s emotional state influenced their learning experience. This reinforces findings by (Goleman, 1995) and (Bisquerra, 2011), who note that emotions mediate attention, memory, and motivation—critical elements for academic achievement. Additionally, respondents observed that their teachers displayed a consistently positive and motivating attitude, positioning educators as emotional role models in the classroom. As (Martínez et al., 2021) suggests, teacher emotional disposition directly shapes students’ emotional responses and promotes a positive climate for learning. This study offers relevant contributions from the field of exact sciences, where emotional components have traditionally received less attention. The positive student feedback highlights that integrating ICTs with EI in chemistry is not only feasible but pedagogically enriching. It also supports research such as that of (Ramírez-Montoya & García-Peñalvo, 2019), who advocate for hybrid teaching models where technology serves both cognitive and emotional development.

In summary, the use of ICTs combined with EI significantly improved concentration, motivation, curiosity, and emotional well-being in students. These variables—traditionally studied in isolation—should be regarded as synergistic components of the teaching-learning process, particularly in university-level science education where academic success depends as much on emotional engagement as on content mastery.

Authors' Contribution

Conceptualization A.V.; data curation A.V.; formal analysis A.V. and M.R.M.; investigation A.V. and M.R.M.; methodology A.V. and M.R.M.; supervision A.V.; M.R.M. and J.G.; validation A.V.; M.R.M. and J.G.; visualization A.V.; M.R.M. and J.G.; writing – original draft A.V.; writing – review and editing A.V.; M.R.M. and J.G.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the UTN and thank the professors and students who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Abadal, E.; Abad García, M.F.; Anglada i de Ferrer, L.M.; Borrego, À.; Borrego, H.; Claudio González, M.G.; Delgado López-Cózar, E.; Guallar, J.; López-Borrull, A.; Melero Melero, R.; et al. (2017). Revistas científicas: Situación actual y retos de futuro. En Col·lecció Biblioteca Universitària—eBooks—(Publicacions i Edicions UB). Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona. https://diposit.ub.

- Aivaloglou, E.; Hermans, F. Early Programming Education and Career Orientation: The Effects of Gender, Self-Efficacy, Motivation and Stereotypes. Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education 2019, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-García, S.; Aznar-Díaz, I.; Cáceres-Reche, M.-P.; Trujillo-Torres, J.-M.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.-M. Systematic Review of Good Teaching Practices with ICT in Spanish Higher Education. Trends and Challenges for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T. The Theory and Practice of Online Learning; Athabasca University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Area-Moreira, M. Educación y tecnologías: Las TIC como instrumentos de innovación didáctica; Ediciones Morata., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto Santos, R.D.; Lescay Blanco, D.M. Estrategia didáctica basadas en el uso de tic para la enseñanza-aprendizaje de la química. Polo del Conocimiento: Revista científico - profesional 2023, 8, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bhurtun, C.; Jahmeerbacus, I.; Jeewooth, C. Short term load forecasting in Mauritius using Neural Network, 2011.

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C.; Kennedy, G. Teaching for Quality Learning at University 5e, 2022.

- Bisquerra, R. Educar las emociones en la escuela; Graó, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bonk, C.J. The World is Open: How Web Technology Is Revolutionizing Education. 2009, 3371–3380. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/31963/.

- Bruner, J. La educación, puerta de la cultura; Visor, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos, D.; Ahmed, T.; Tabaco, A. Recommendations for Mandatory Online Assessment in Higher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic; SpringerLink, 2020; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-7869-4_6.

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Llorente-Cejudo, C. Covid-19: Transformación radical de la digitalización en las instituciones universitarias. Campus Virtuales 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Llorente-Cejudo, C. El dominio digital del profesorado universitario: Competencias y necesidades formativas. Educación XXI 2020, 23, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Muñoz, J.; Duart, J.M.; Sancho-Vinuesa, T. La inteligencia emocional como factor de éxito en entornos de aprendizaje en línea. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 2018, 21, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Ramírez, M.; Gónzalez, M. El aprendizaje significativo de la química: Condiciones para lograrlo. Universidad del Zulia 2013, 19, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi, Z.; Chiarenza, D.; Dominighini, C.; Donnamaría, M.C.; Lage, F.J. TICs en la enseñanza de la química 2010. Available online: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/19621.

- Cataldi, Z.; Donnamaría, M.C.; Lage, F.J. Didáctica de la química y TICs: Laboratorios virtuales, modelos y simulaciones como agentes de motivación y de cambio conceptual, 2009. Available online: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/18979.

- Charlot, B. La relación con el saber, formación de maestros y profesores, educación y globalización; Ediciones Trilce, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cleophas, M.D.G.; Marques, M.S.; Barbosa, M.C. Self-perceived competences by future chemistry teachers in Brazil. Anais Da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2022, 95, e20221057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, I.A.; Rodríguez, J.M.R.; García, A.M.R. La tecnología móvil de Realidad Virtual en educación: Una revisión del estado de la literatura científica en España. EDMETIC 2018, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, S. Connectivism. Asian Journal of Distance Education 2022, 17, 1. Available online: https://asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/623.

- García-Peñalvo, F.; Conde, M.; Forment, M.; Casany, M. Opening Learning Management Systems to Personal Learning Environments. JUCS - Journal of Universal Computer Science 2011, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R. El aprendizaje electrónico en el siglo XXI: Un marco de trabajo comunitario de investigación y práctica, 3rd ed.; Routledge, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, M.; Esteve, F. Competencia digital docente: Desarrollo de un marco de referencia para la formación del profesorado. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED) 2016, 50, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ; Bantam Books, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Hurtado, I.; González-Falcón, I.; Coronel, J.M. Perceptions of secondary school principals on management of cultural diversity in Spain. The challenge of educational leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 2018, 46, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros Salvat, B.; Cano García, E. Procesos de feedback para fomentar la autorregulación con soporte tecnológico en la educación superior: Revisión sistemática. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 2021, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.L.; Richert, A.E. Unacknowledged knowledge growth: A re-examination of the effects of teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education 1988, 4, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacienminoglu, E. Elementary School Students attitude toward Science and related variables 2016, 11, 32–52. [CrossRef]

- Harasim, L. Teoría del aprendizaje y tecnologías en línea, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. El aprendizaje visible y la ciencia de cómo aprendemos, 1st ed.; Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R. Impacto de las TIC en la educación: Retos y Perspectivas. Propósitos y Representaciones 2017, 5, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobsbawm, E. Age Of Revolution: 1789-1848; Hachette, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning, 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10919/104648.

- Hurtado, C.; Guerrero, L. (2020). ColaboQuim: Una aplicación para apoyar el aprendizaje colaborativo en química, 1–9.

- Lambropoulos, N.; Faulkner, X.; Culwin, F. Supporting social awareness in collaborative e-learning. British Journal of Educational Technology 2012, 43, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.H.P.; Leal, D.A.A.; Vila, G.R.B. El modelo instruccional ASSURE como herramienta para el aprendizaje autónomo en tiempos de crisis. Revista Conrado 2021, 17, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Izaguirre, M.; Eulate, C.Y.-Á. de; Villardón-Galleg, L. Autoevaluación y reflexión docente para la mejora de la competencia profesional del profesorado en la sociedad del conocimiento. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED) 2018, 56, 56. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/red/article/view/321621. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Multimedia learning. En Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Academic Press, 2002; Volume 41, pp. 85–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, C.; Pino, S.; Meyer, E.; Garrido, J.M.; Gallardo, F. Realidad aumentada para el diseño de secuencias de enseñanza-aprendizaje en química. Educación Química 2015, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, S.L.; Nodarse, F.A.F. La educación a distancia en entornos virtuales de enseñanza aprendizaje. Reflexiones didácticas. Atenas 2017, 3, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, R.; Mayer, R. Interactive Multimodal Learning Environments | Educational Psychology Review. 2007, 19, 309-326.

- Moya, J.; Cordero, A.; Fernández, R. Uso de TIC en la enseñanza de ciencias exactas: Una experiencia con laboratorios virtuales y gamificación. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnología en Educación y Educación en Tecnología 2022, 30, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Osuna, F.O.; Medina-Rivilla, A.; Guillén-Lúgigo, M. Jerarquización de competencias genéricas basadas en las percepciones de docentes universitarios. Educación química 2016, 27, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas Gutiérrez, D. El uso del Foro de Discusión Virtual en la enseñanza. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 2007, 44, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez Cala, M.L.; Castaño Castrillón, J.J. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Psicología desde el Caribe 2015, 32, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López, I.; Rivera, E. (2017). Formar docentes, formar personas: Análisis de los aprendizajes logrados por estudiantes universitarios desde una experiencia de gamificación | Signo y Pensamiento. Available online: https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/signoypensamiento/article/view/19545. [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Llorente, A.M.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.C.; García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Casillas-Martín, S. Students’ perceptions and attitudes towards asynchronous technological tools in blended-learning training to improve grammatical competence in English as a second language. Computers in Human Behavior 2017, 72, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, J.I.; del Pérez Echeverría, M.P.; Cabellos, B. Las emociones en la enseñanza de las ciencias: Una revisión desde la psicología educativa. Infancia y Aprendizaje 2020, 43, 281–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proszek, R.; Ferreira, M. Enseñanza de la Química en Ambientes Virtuales: Blogs. Formación universitaria 2009, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Autoeficacia digital docente en escenarios de innovación educativa con tecnología. Educación y Tecnología 2019, 20, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsami, P.; King, R. (2020). Neural Network Frameworks for Electricity Forecasting in Mauritius and Rodrigues Islands. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9543176.

- Ritchie, S.M.; Tobin, K. Eventful Learning, Brill, 2018. Available online: https://brill.com/display/title/38958.

- Sáiz-Manzanares, M.C.; Escolar-Llamazares, M.-C.; Arnaiz González, Á. Effectiveness of Blended Learning in Nursing Education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, J.; De Benito, B.; Lizana, M. La formación docente en TIC e inteligencia emocional: Un enfoque necesario para la educación superior. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa 2022, 82, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandi-Urena, S.; Cooper, M.; Stevens, R. Effect of Cooperative Problem-Based Lab Instruction on Metacognition and Problem-Solving Skills. Journal of Chemical Education 2012, 89, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. La tecnología digital y la universidad contemporánea: Grados de digitalización, 1st ed.; Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez-Pérez, Y.; Rose-Parra, C.; Oquendo-González, E.J.; Cervera-Manjarrez, N. Inteligencia emocional, motivación y desarrollo cognitivo en estudiantes. Cienciamatria. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Humanidades, Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología 2023, 9, 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafañe, S.M.; Xu, X.; Raker, J.R. Self-efficacy and academic performance in first-semester organic chemistry: Testing a model of reciprocal causation. Chemistry Education Research and Practice 2016, 17, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).