Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Contemplative Practices: Theoretical Frameworks

1.2. Trauma and Post-Traumatic Symptoms: Recovery Pathways Through Contemplative Practices

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

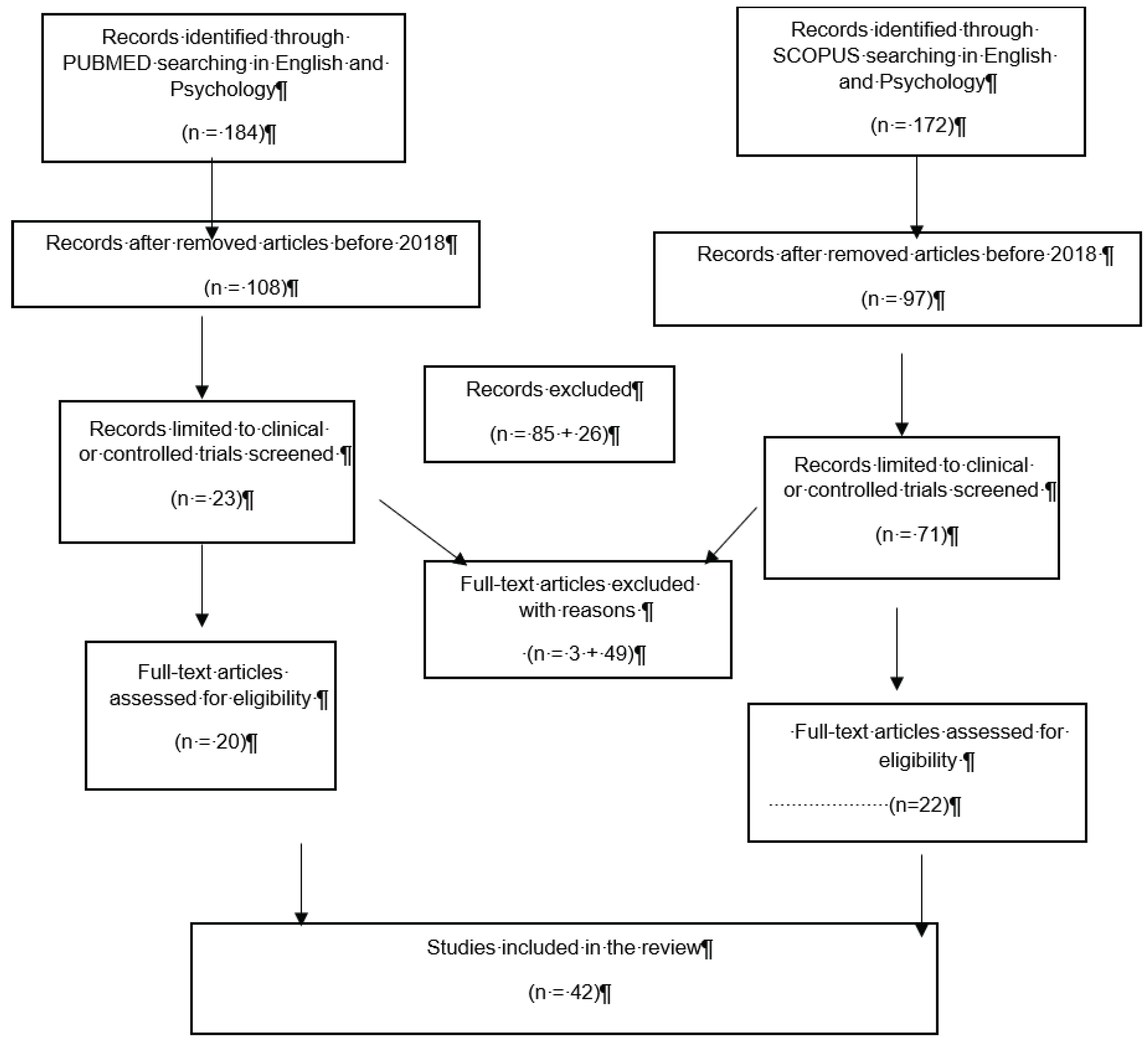

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics: Design and Samples

3.3. Type of Trauma

3.4. Type of Contemplative Practices

3.5. Primary Outcome: Measures

3.6. Secondary Outcomes: Measures

3.7. Effects of Contemplative Practices on Trauma Recovery

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Glossary

| Abbreviation | Description |

| AAOc | Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-Cancer |

| ANS | Autonomous Nervous System |

| AQoL-8D | Australian Quality of Life (8-dimension) |

| ASI | Addiction Severity Index |

| AUDIT-C | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory-II |

| BEAQ | Brief Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire; |

| BEVS | Bull’s-Eye Values Survey |

| BPM | Brief Problem Monitor |

| BRIEF | Behavioral Rating Inventory of Executive Function |

| BSI | Brief Symptom Inventory |

|

BSI-18 BSSS |

Brief Symptom Inventory Brief Sensation Seeking Scale |

| CAMS-R | Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised |

| CAPS | Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale |

| CAPS-5 | Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 |

| CARS | Concerns About Recurrence Scale |

| COPE | Coping Orientation to the Problems Experienced |

| CSQ | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| CSQ-8 | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| CTQ-SF | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale |

| DERS | Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale |

| DES | Dissociative Experiences Scale |

| DES’ | Differential Emotions Scale |

| DTS | Davidson Trauma Scale |

| EAC | Emotional Approach Coping scale |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ERQ | Emotion Regulation Questionnaire |

| ERS | Emotion Regulation Scale |

| FCS | fears of compassion scales |

| FFMQ | Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire |

| FMI | Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory |

| FSCRS | Forms of Self-Criticizing/attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale |

| GHQ-28 | General Health Questionnaire |

| HADS-A | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety subscale |

| Ham-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HEBR | Heartbeat-evoked brain response |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| HSCL | Hopkins Symptom Checklist |

| HTQ | The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire |

| IASC | Inventory of Altered Self-Capacities |

| ICG | Impedance Cardiography |

| IES | Impact of Events Scale |

| IES-R | Impact of Events Scale-Revised |

| IIP-32 | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems |

| IMR | Illness Management and Recovery |

| IPDE | International Personality Disorder Examination |

| IPVE | Intimate Partner Violence exposure |

| ISI | Insomnia Severity Index |

| K10 | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale |

| LEC-5 | Life Events Checklist |

| LKM | loving-kindness meditation |

| LKM-S | loving-kindness meditation for self-compassion |

| LSCL-R | Life Stressor Checklist Revised |

| LSI | Leisure Score Index |

| MAAS | Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale |

| MAIA | Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness |

| MBE | Mindful-Breathing Exercise |

| MINI | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| NIH PROMIS | National Institutes of Health’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| OAS | Other as Shamer Scale |

| OCSS | Overall Course Satisfaction Survey |

| OLBI | Oldenburg Burnout Inventory |

| PACS | Penn Alcohol Craving Scale |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| PBPT | Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatments |

| PCL-5 | PTSD checklist for DSM-5 |

| PCL-C | PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version |

| PCL-M | PTSD Checklist-Military Version |

| PHLMS | Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PHQ-8 | Patient Health Questionnaire Eight-item version |

| PHQ-9 | Brief Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression |

| PMLD | Postmigration Living Difficulties Scale |

| PROMIS | Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 43-item version |

| PSOM | Positive States of Mind Scales |

| PSQ | Police Stress Questionnaire |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| PSS | PTSD Symptom Scale-Self Report |

| PTSS | The Post-Traumatic Stress Scale |

| PWB | Psychological Well-Being Scale |

| Q-LES-SF | Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire–Short Form |

| RAS | Relationship Assessment Scale |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REDS | Reward-based Eating Drive Scale |

| RMSSD | Root Mean Square of Successive Differences |

| RTSQ | Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire |

| S-Ang | State Anger scale |

| SBC | Scale of Body Connection |

| SCID-I | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV |

| SCL | Skin Conductance Levels |

| SCS | Self- Compassion Scale |

| SCS-R | Social Connectedness Scale–Revised |

| SCS-S | Self- Compassion Scale- Short Form |

| SDQ-20 | Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire |

| SIDES-SR | Structured Interview for Disorders of Extreme Stress, Self- Report version |

| SLESQ | Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire |

| SRET | Self-Referential Encoding Task |

| SRS | Soothing Receptivity Scale |

| SSGS | State Shame and Guilt Scale |

| SSPS | Social Safeness and Pleasure Scale |

| SSS-8 | Eight-item Somatic Symptom Scale |

| SSST | Sing-a-Song Stress Test |

| STAXI-2 | State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory–2 |

| SUD | Subjective Units of Distress Scale |

| TEI | Traumatic Events Inventory |

| TEQ | Toronto Empathy Questionnaire |

| TF | Time Frequency |

| TLFB | Timeline Follow Back |

| TM | Transcendental Meditation |

| TRIER-C | Trier Social Stress Task for Children |

| TSK-11 | Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia |

| UFOV | Useful Field of View Test |

| VAS | Visual Analogue scales |

| VLQ | Valued Living Questionnaire |

| VU-AMS | VU University Monitoring System |

| WAI-SR | Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised |

| WGO-5 | WHO-Five Well-Being Index |

| WHOQOL | World Health Organization Quality of Life, Brief Version |

| WQL-8 | Work Limitations Questionnaire-Short Form |

| WSAS | Work and Social Adjustment Scale |

References

- *Aizik-Reebs, A., Amir, I., Yuval, K., Hadash, Y., & Bernstein, A. (2022). Candidate mechanisms of action of mindfulness-based trauma recovery for refugees (MBTR-R): Self-compassion and self-criticism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(2), 107-122. [CrossRef]

- Amihai, I., & Kozhevnikov, M. (2014). Arousal vs. relaxation: A comparison of the neurophysiological and cognitive correlates of Vajrayana and Theravada meditative practices. PloS One, 9(7), e102990. [CrossRef]

- Aquinas, T. (1869). Summa theologica (Vol. 5). Guerin.

- Aquinas, T. (1975). Summa contra gentiles. Book Two: Creation. University of Notre Dame.

- *Bandy, C. L., Dillbeck, M. C., Sezibera, V., Taljaard, L., Wilks, M., Shapiro, D., de Reuck, J., & Peycke, R. (2020). Reduction of PTSD in South African University Students Using Transcendental Meditation Practice. Psychological Reports, 123(3), 725–740. [CrossRef]

- *Bellehsen, M., Stoycheva, V., Cohen, B. H., & Nidich, S. (2022). A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Transcendental Meditation as Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans. Journal of traumatic stress, 35(1), 22–31. [CrossRef]

- Bodhi, B. (2012) The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Aṅguttara Nikāya. Pāli Text Society in association with Wisdom Publications.

- Boyd, J. E., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 43(1), 7-25. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822-848. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M. M., Kassam-Adams, N., Rogers, M., Anderson, K. M., Sluys, K. P., & Richmond, T. S. (2018). Trauma Providers’ Knowledge, Views, and Practice of Trauma-Informed Care. Journal of Trauma Nursing: The Official Journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses, 25(2), 131–138. [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, L. G., Cann, A., Tedeschi, R. G., & McMillan, J. (2000). A correlational test of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, religion, and cognitive processing. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(3), 521–527. [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A., Serretti, A., & Jakobsen, J. C. (2013). Mindfulness: Top–down or bottom–up emotion regulation strategy?. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 82-96. [CrossRef]

- *Chopin, S. M., Sheerin, C. M., & Meyer, B. L. (2020). Yoga for warriors: An intervention for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(8), 888–896. [CrossRef]

- *Classen, C. C., Hughes, L., Clark, C., Hill Mohammed, B., Woods, P., & Beckett, B. (2021). A pilot RCT of a body-oriented group therapy for complex trauma survivors: an adaptation of sensorimotor psychotherapy. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 22(1), 52-68. [CrossRef]

- Conversano, C., Di Giuseppe, M., Miccoli, M., Ciacchini, R., Gemignani, A., & Orrù, G. (2020). Mindfulness, Age and Gender as Protective Factors Against Psychological Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1900. [CrossRef]

- *Cox, C. E., Hough, C. L., Jones, D. M., Ungar, A., Reagan, W., Key, M. D., ... & Porter, L. S. (2019). Effects of mindfulness training programmes delivered by a self-directed mobile app and by telephone compared with an education programme for survivors of critical illness: a pilot randomised clinical trial. Thorax, 74(1), 33-42. [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H. D., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2017). Interoception and emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 7–14. [CrossRef]

- *Davis, L. W., Schmid, A. A., Daggy, J. K., Yang, Z., O'Connor, C. E., Schalk, N., ... & Knock, H. (2020). Symptoms improve after a yoga program designed for PTSD in a randomized controlled trial with veterans and civilians. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(8), 904. [CrossRef]

- DeLoach, C. D., & Petersen, M. N. (2010). African spiritual methods of healing: The use of Candomblé in traumatic response. Journal of Pan African Studies, 3(8), 40-65.

- DeRosa, R., & Pelcovitz, D. (2009). Group treatment for chronically traumatized adolescents: Igniting SPARCS of change. In Treating traumatized children: Risk, resilience and recovery (pp. 225–239). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Duran, E., Firehammer, J., & Gonzalez, J. (2008). Liberation Psychology as the Path Toward Healing Cultural Soul Wounds. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86. [CrossRef]

- Durà-Vilà, G., Littlewood, R., & Leavey, G. (2013). Integration of sexual trauma in a religious narrative: Transformation, resolution and growth among contemplative nuns. Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(1), 21–46. [CrossRef]

- *Fishbein, J. N., Judd, C. M., Genung, S., Stanton, A. L., & Arch, J. J. (2022). Intervention and mediation effects of target processes in a randomized controlled trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for anxious cancer survivors in community oncology clinics. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 153, 104103. [CrossRef]

- Fiske, E., Martin, S., & Luetkemeyer, J. (2020). Building Nurses’ Resilience to Trauma Through Contemplative Practices. Creative Nursing, 26(4), e90–e96. [CrossRef]

- *Fortuna, L. R., Falgas-Bague, I., Ramos, Z., Porche, M. V., & Alegría, M. (2020). Development of a cognitive behavioral therapy with integrated mindfulness for Latinx immigrants with co-occurring disorders: Analysis of intermediary outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(8), 825-835. [CrossRef]

- *Gallegos, A. M., Heffner, K. L., Cerulli, C., Luck, P., McGuinness, S., & Pigeon, W. R. (2020). Effects of mindfulness training on posttraumatic stress symptoms from a community-based pilot clinical trial among survivors of intimate partner violence. Psychological Trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy, 12(8), 859-868. [CrossRef]

- Garland, E. L., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., & Wichers, M. (2015). Mindfulness training promotes upward spirals of positive affect and cognition: Multilevel and autoregressive latent trajectory modeling analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 15. [CrossRef]

- *Gerdes, S., Williams, H., & Karl, A. (2022). Psychophysiological responses to a brief self-compassion exercise in armed forces veterans. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 780319. [CrossRef]

- Germer, C.K., & Siegel, R.D. (2014). Wisdom and Compassion in Psychotherapy. Deepening Mindfulness in Clinical Practice. Guilford Press.

- Glassman, E. (1988). Development of a self-report measure of soothing receptivity [Ph.D.]. York University.

- Ghiroldi, S., Scafuto, F., Montecucco, N.F. et al. Effectiveness of a School-Based Mindfulness Intervention on Children’s Internalizing and Externalizing Problems: the Gaia Project. Mindfulness 11, 2589–2603 (2020). [CrossRef]

- *Gibert, L., Coulange, M., Reynier, J. C., Le Quiniat, F., Molle, A., Bénéton, F., ... & Trousselard, M. (2022). Comparing meditative scuba diving versus multisport activities to improve post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: a pilot, randomized controlled clinical trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2031590. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S. B., Riordan, K. M., Sun, S., & Davidson, R. J. (2022). The Empirical Status of Mindfulness-Based Interventions: A Systematic Review of 44 Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 17(1), 108–130. [CrossRef]

- *Goldstein, L. A., Mehling, W. E., Metzler, T. J., Cohen, B. E., Barnes, D. E., Choucroun, G. J., Silver, A., Talbot, L. S., Maguen, S., Hlavin, J. A., Chesney, M. A., & Neylan, T. C. (2018). Veterans Group Exercise: A randomized pilot trial of an Integrative Exercise program for veterans with posttraumatic stress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 345–352. [CrossRef]

- *Grupe, D. W., McGehee, C., Smith, C., Francis, A. D., Mumford, J. A., & Davidson, R. J. (2021). Mindfulness training reduces PTSD symptoms and improves stress-related health outcomes in police officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36(1), 72–85. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, A. W., Garland, E. L., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2017). Relating dispositional mindfulness, contemplative practice, and positive reappraisal with posttraumatic cognitive coping, stress, and growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9(5), 526–536. [CrossRef]

- *Hodgdon, H. B., Anderson, F. G., Southwell, E., Hrubec, W., & Schwartz, R. (2022). Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among Survivors of Multiple Childhood Trauma: A Pilot Effectiveness Study. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 31(1), 22–43. [CrossRef]

- Hopson, D. P., & Hopson, D. S. (1999). The power of soul: Pathways to psychological and spiritual growth for African Americans. Harper Perennial.

- Ibañez, G. E., Sanchez, M., Villalba, K., & Amaro, H. (2022). Acting with awareness moderates the association between lifetime exposure to interpersonal traumatic events and craving via trauma symptoms: a moderated indirect effects model. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 287. [CrossRef]

- Jäger, W. (2003). Search for the meaning of life: Essays and reflections on the mystical experience. Liguori/Triumph.

- *Jasbi, M., Sadeghi Bahmani, D., Karami, G., Omidbeygi, M., Peyravi, M., Panahi, A., ... & Brand, S. (2018). Influence of adjuvant mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans–results from a randomized control study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(5), 431-446. [CrossRef]

- *Javidi, Z., Prior, K.N., Sloan, T.L. et al. A randomized controlled trial of self-compassion versus cognitive therapy for complex psychopathologies. Current Psychology, 42, 946–954 (2023). [CrossRef]

- *Kananian, S., Soltani, Y., Hinton, D., & Stangier, U. (2020). Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Plus Problem Management (CA-CBT+) With Afghan Refugees: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Journal of Traumatic stress, 33(6), 928–938. [CrossRef]

- *Kang, S. S., Sponheim, S. R., & Lim, K. O. (2022). Interoception underlies therapeutic effects of mindfulness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 7(8), 793-804. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, U. A., Evans, D. D., Baker, H., & Noggle Taylor, J. (2018). Determining Psychoneuroimmunologic Markers of Yoga as an Intervention for Persons Diagnosed With PTSD: A Systematic Review. Biological Research for Nursing, 20(3), 343–351. [CrossRef]

- *Killeen, T. K., Wen, C. C., Neelon, B., & Baker, N. (2023). Predictors of Treatment Completion among Women Receiving Integrated Treatment for Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use Disorders. Substance Use & Misuse, 58(4), 500-511. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H., Schneider, S. M., Kravitz, L., Mermier, C., & Burge, M. R. (2013). Mind-body practices for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 61(5), 827-834. [CrossRef]

- *Knabb, J. J., Vazquez, V. E., Pate, R. A., Lowell, J. R., Wang, K. T., De Leeuw, T. G., Dominguez, A. F., Duvall, K. S., Esperante, J., Gonzalez, Y. A., Nagel, G. L., Novasel, C. D., Pelaez, A. M., Strickland, S., & Park, J. C. (2022). Lectio divina for trauma symptoms: A two-part study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 9(4), 232–252. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A. J., Casmar, P., Hurst, S., Harrison, T., Golshan, S., Good, R., … Negi, L. (2017). Compassion meditation for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A nonrandomized study. Mindfulness, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- *Lang, A. J., Malaktaris, A. L., Casmar, P., Baca, S. A., Golshan, S., Harrison, T., & Negi, L. (2019). Compassion meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: A randomized proof of concept study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(2), 299-309. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A. J., Strauss, J. L., Bomyea, J., Bormann, J. E., Hickman, S. D., Good, R. C., & Essex, M. (2012). The theoretical and empirical basis for meditation as an intervention for PTSD. Behavior Modification, 36, 759–786. [CrossRef]

- LaVallie, C., & Sasakamoose, J. (2023). Promoting indigenous cultural responsivity in addiction treatment work: The call for neurodecolonization policy and practice. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 22(3), 477–499. [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S. W., Bush, G., Gollub, R. L., Fricchione, G. L., Khalsa, G., & Benson, H. (2000). Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation. Neuroreport, 11(7), 1581–1585. [CrossRef]

- Lazzarelli, A., Scafuto, F., Crescentini, C., Matiz, A., Orrù, G., Ciacchini, R., ... & Conversano, C. (2024). Interoceptive Ability and Emotion Regulation in Mind–Body Interventions: An Integrative Review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1107. [CrossRef]

- *Leach, M. J., & Lorenzon, H. (2024). Transcendental Meditation for women affected by domestic violence: A pilot randomised, controlled trial. Journal of Family Violence, 39(8), 1437-1446. [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K., & Britton, W. B. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PloS One, 12(5), e0176239. [CrossRef]

- Loizzo J. J. (2016). The subtle body: an interoceptive map of central nervous system function and meditative mind-brain-body integration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 78–95. [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, J. (2014). Meditation research, past, present, and future: Perspectives from the Nalanda contemplative science tradition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1307(1), 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Macy, J. (1991). Mutual causality in Buddhism and general systems theory: The dharma of natural systems. Suny Press. [CrossRef]

- *Mehling, W. E., Chesney, M. A., Metzler, T. J., Goldstein, L. A., Maguen, S., Geronimo, C., Agcaoili, G., Barnes, D. E., Hlavin, J. A., & Neylan, T. C. (2018). A 12-week integrative exercise program improves self-reported mindfulness and interoceptive awareness in war veterans with posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 554–565. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, T., Clary, L. K., Sibinga, E., Tandon, D., Musci, R., Mmari, K., ... & Ialongo, N. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of a trauma-informed school prevention program for urban youth: Rationale, design, and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 90, 105895. [CrossRef]

- *Miller, R. L., Moran, M., Shomaker, L. B., Seiter, N., Sanchez, N., Verros, M., ... & Lucas-Thompson, R. (2021). Health effects of COVID-19 for vulnerable adolescents in a randomized controlled trial. School Psychology, 36(5), 293-302. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, N. M., & Wall, D. J. (2011). African dance as healing modality throughout the diaspora: The use of ritual and movement to work through trauma. Journal of Pan African Studies, 4(6), 234-252. [CrossRef]

- *Müller-Engelmann, M., Schreiber, C., Kümmerle, S., Heidenreich, T., Stangier, U., & Steil, R. (2019). A trauma-adapted mindfulness and loving-kindness intervention for patients with PTSD after interpersonal violence: A multiple-baseline study. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1105–1123. [CrossRef]

- *Nguyen-Feng, V. N., Hodgdon, H., Emerson, D., Silverberg, R., & Clark, C. J. (2020). Moderators of treatment efficacy in a randomized controlled trial of trauma-sensitive yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy, 12(8), 836-846. [CrossRef]

- Norbu, N., & Shane, J. (1987). Il cristallo e la via della luce: Sutra, tantra e Dzog-chen. Ubaldini. [CrossRef]

- *Ong, I., Cashwell, C. S., & Downs, H. A. (2019). Trauma-sensitive yoga: A collective case study of women’s trauma recovery from intimate partner violence. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 10(1), 19–33. [CrossRef]

- *Oren-Schwartz, R., Aizik-Reebs, A., Yuval, K., Hadash, Y., & Bernstein, A. (2023). Effect of mindfulness-based trauma recovery for refugees on shame and guilt in trauma recovery among African asylum-seekers. Emotion, 23(3), 622-632. [CrossRef]

- Poli, A., Gemignani, A., Soldani, F., & Miccoli, M. (2021). A Systematic Review of a Polyvagal Perspective on Embodied Contemplative Practices as Promoters of Cardiorespiratory Coupling and Traumatic Stress Recovery for PTSD and OCD: Research Methodologies and State of the Art. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11778. [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2001). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42(2), 123–146. [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2003). The Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic contributions to social behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 79(3), 503–513. [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. Norton & Co. [CrossRef]

- *Possemato, K., Bergen-Cico, D., Buckheit, K., Ramon, A., McKenzie, S., Smith, A. R., ... & Pigeon, W. R. (2022). Randomized clinical trial of brief primary care–based mindfulness training versus a psychoeducational group for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. The journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 84(1), 44829. [CrossRef]

- *Powers, A., Lathan, E. C., Dixon, H. D., Mekawi, Y., Hinrichs, R., Carter, S., ... & Kaslow, N. J. (2022). Primary Care-Based Mindfulness Intervention for PTSD and Depression Symptoms among Black Adults: A Pilot Feasibility and Acceptability Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychological Trauma: theory, research, practice and policy, 15(5), 858-867. [CrossRef]

- *Pradhan, B., Mitrev, L., Moaddell, R., & Wainer, I. W. (2018). d-Serine is a potential biomarker for clinical response in treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder using (R, S)-ketamine infusion and TIMBER psychotherapy: a pilot study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics, 1866(7), 831-839. [CrossRef]

- Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2009). Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(5), 364–388. [CrossRef]

- *Reinhardt, K. M., Noggle Taylor, J. J., Johnston, J., Zameer, A., Cheema, S., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2018). Kripalu Yoga for Military Veterans With PTSD: A Randomized Trial. Journal of clinical psychology, 74(1), 93–108. [CrossRef]

- Riley, K. E., & Park, C. L. (2015). How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 379–396. [CrossRef]

- *Romaniuk, M., Hampton, S., Brown, K., Fisher, G., Steindl, S. R., Kidd, C., & Kirby, J. N. (2023). Compassionate mind training for ex-service personnel with PTSD and their partners. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(3), 643–658. [CrossRef]

- Rowe-Johnson, M. K., Browning, B., & Scott, B. (2024). Effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on trauma-related symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy;17(3):668-675. [CrossRef]

- Rose, K. (2016). Yoga, meditation, and mysticism: Contemplative universals and meditative landmarks. Bloomsbury Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Ross, C. B., & Rocha Beardall, T. (2022). Promoting Empathy and Reducing Hopelessness Using Contemplative Practices. Teaching Sociology, 50(3), 256-268. [CrossRef]

- Salzberg, S. (2011). Mindfulness and Loving-Kindness. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 177–182. [CrossRef]

- Scafuto, F., Ghiroldi, S., Montecucco, N. F., De Vincenzo, F., Quinto, R. M., Presaghi, F., & Iani, L. (2024). Promoting well-being in early adolescents through mindfulness: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of adolescence, 96(1), 57–69. [CrossRef]

- Scafuto, F., Ghiroldi, S., Montecucco, N. F., Presaghi, F., & Iani, L. (2022). The Mindfulness-Based Gaia Program Reduces Internalizing Problems in High-School Adolescents: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness, 13(7), 1804–1815. [CrossRef]

- Schmalzl, L., Crane-Godreau, M. A., & Payne, P. (2014). Movement-based embodied contemplative practices: Definitions and paradigms. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 205. [CrossRef]

- *Schuurmans, A. A. T., Nijhof, K. S., Scholte, R., Popma, A., & Otten, R. (2021). Effectiveness of game-based meditation therapy on neurobiological stress systems in adolescents with posttraumatic symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Stress, 24(6), 1042–1049. [CrossRef]

- Shannahoff-Khalsa, D. (2008). Kundalini Yoga meditation techniques in the treatment of obsessive compulsive and OC spectrum disorders. In A.R., Roberts (Ed.), Social Workers’ Desk Reference, second edition, pp. 606–612. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- *Somohano, V. C., & Bowen, S. (2022). Trauma-integrated mindfulness-based relapse prevention for women with comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder: a cluster randomized controlled feasibility and acceptability trial. Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 28(9), 729-738. [CrossRef]

- *Somohano, V. C., Kaplan, J., Newman, A. G., O’Neil, M., & Lovejoy, T. (2022). Formal mindfulness practice predicts reductions in PTSD symptom severity following a mindfulness-based intervention for women with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorder. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 17(1), 51. [CrossRef]

- *Staples, J. K., Gordon, J. S., Hamilton, M., & Uddo, M. (2022). Mind-body skills groups for treatment of war-traumatized veterans: A randomized controlled study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 14(6), 1016–1025. [CrossRef]

- Sparby, T., & Sacchet, M. D. (2022). Defining meditation: foundations for an activity-based phenomenological classification system. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 795077. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V. A., Grant, J., Daneault, V., Scavone, G., Breton, E., Roffe-Vidal, S., Courtemanche, J., Lavarenne, A. S., & Beauregard, M. (2011). Impact of mindfulness on the neural responses to emotional pictures in experienced and beginner meditators. NeuroImage, 57(4), 1524–1533. [CrossRef]

- *Tibbitts, D. C., Aicher, S. A., Sugg, J., Handloser, K., Eisman, L., Booth, L. D., & Bradley, R. D. (2021). Program evaluation of trauma-informed yoga for vulnerable populations. Evaluation and Program Planning, 88, 101946. [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B. A., Stone, L., West, J., Rhodes, A., Emerson, D., Suvak, M., & Spinazzola, J. (2014). Yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(6), e559-565. [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W., Sapthiang, S., & Shonin, E. (2022). Contemplative psychology: History, key assumptions, and future directions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 99-107. [CrossRef]

- Vujanovic, A. A., Smith, L. J., Green, C., Lane, S. D., & Schmitz, J. M. (2020). Mindfulness as a predictor of cognitive-behavioral therapy outcomes in inner-city adults with posttraumatic stress and substance dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 104, 106283. [CrossRef]

- Warren, S., & Chappell Deckert, J. (2020). Contemplative Practices for Self-Care in the Social Work Classroom. Social work, 65(1), 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Watts B.V, Schnurr P.P, Mayo L., Young-Xu Y., Weeks W.B, Friedman M.J. (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 74(6):e541-50. [CrossRef]

- *Yi, L., Lian, Y., Ma, N., & Duan, N. (2022). A randomized controlled trial of the influence of yoga for women with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Translational Medicine, 20(1), 162. [CrossRef]

- *Zaccari, B., Callahan, M. L., Storzbach, D., McFarlane, N., Hudson, R., & Loftis, J. M. (2020). Yoga for veterans with PTSD: Cognitive functioning, mental health, and salivary cortisol. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(8), 913–917. [CrossRef]

- *Zalta, A. K., Pinkerton, L. M., Valdespino-Hayden, Z., Smith, D. L., Burgess, H. J., Held, P., Boley, R. A., Karnik, N. S., & Pollack, M. H. (2020). Examining Insomnia During Intensive Treatment for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Does it Improve and Does it Predict Treatment Outcomes?. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(4), 521–527. [CrossRef]

| N | Authors | Study Design | Sample Size | Type of Trauma | Type of Contemplative Practices | Duration | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oren-Schwarz, 2023 | RCT with active control | 158 Eritrean asylum-seekers (55.7% female); Mage= 31,8 (SD= 5.2) residing in high-risk urban setting in the Middle East |

Forced Displacement | Mindfulness-Compassion Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees program (MBTR-R) | 9-weekly sessions (2.5 hr for each) | HTQ; PHQ-9; SSGS; PMLD | MBTR-R, relative to waitlist control →shame (no guilt) at post-test → PTSD symptom severity (HTQ subscale) / Depression (PHQ-9) at post-test |

| 2 | Powers et al., 2023 | RCT with active control and 1-month follow-up | 42 Black adults (85% women); Age from 18 to 65; screened positive for PTSD and depression, 57,1% (55.5% of MBCT, 87.5% of WLC) |

PTSD and chronic trauma exposure to multiple events |

Adapted mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) group for trauma exposed Black adults |

8-weekly sessions (1,5 hr for each) | TEI; PHQ-9; CAPS-5; MINI for screening; CSQ-8; PBPT | Good feasibility (75% completers) Good Acceptability: high levels of satisfaction (CSQ-8) and several perceived benefits regarding physical, emotional state and interpersonal relationships; The most frequently reported barriers (PBPT): participation restrictions, stigma, lack of motivation, no availability of services, emotional concerns, misfit of therapy to needs, time constraints, and negative evaluation. |

| 3 | Killeen et al., 2023 | RCT with active control Integrative Coping Skills (ICS) | 90 Women (53,3% non-completers); Age from 18 to 65 |

PTSD-Substance Use Disorder (SUD) | Trauma adapted mindfulness-based relapse prevention (TA-MBRP) | 8 weekly sessions | Rate of Retention in the treatment; PSS; FFMQ; MINI; CAPS-5; TLFB; DERS | 48 women met the definition of non-completers (attending < 75% sessions); ↓ Lowest rate of completion among unemployed women in the ICS control group, with low FFMQ; ↑ Higher rate of completion in women in TA-MBRP group with low PSS and high FFMQ; ↓ Both the TA-MBRP and ICS groups had low probability of completion for those with high-PSS scores. |

| 4 | Aizik-Reebs et al., 2022 | RCT with waitlist and 5 weeks follow-up | 158 Eritrean asylum-seekers (46% female); Mage=31.8 (SD=5.2); in an urban post displacement setting. |

Traumatized and chronically stressed; Forced Displacement |

Mindfulness-Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees Program (MBTR-R) |

9-weekly sessions (2.5 hr for each) | HTQ; PHQ-9; SRET | ↓Posttest change in self-criticism (endorsement and drift rate) ↔Posttest change in drift rates to self-compassion stimuli ↑ Posttest increase in self-compassion (endorsement) Type of treatment (MBTR-R; Waitlist) →change of self-criticism (at post-test) → PTSD symptoms (HTQ) and depression (PHQ-9); Type of treatment (MBTR-R; Waitlist) →change of self-compassion (at post-test) → PTSD symptoms (HTQ), but not depression (PHQ-9) |

| 5 | Yi. et al., 2022 | RCT with active controlk | 94 women; Mage= 40.8 (SD= 13,2), Most drivers with almost two months since MVA |

PTSD from Motor vehicle Accident (MVA) | Kripalu Yoga | 6 sessions (45 min for each) for 12 weeks | IES-R; DASS-21 | ↓IES-R at post-test ↓Subscales Intrusion and Avoidance ↔Subscale Hyperarousal ↔IES-R at 3-month follow-up ↓DASS-21 at post-test and 3-month follow-up and Tot score˂Control ↓Subscales Depression and Anxiety ↔Subscale Stress |

| 6 | Kang, Sponheim & Lim, 2022 | RCT with active control (Present-centered group therapy) | 98 veterans with PTSD symptoms (PCL) (14,3% women); Mage= 58.6 (SD= 10.4) |

PTSD from combat | Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | 8 weekly sessions | PCL-5; CAPS; PHQ-9; PHQ-15 EEG recorded with BioSemi Active Two EEG system in resting-meditation-resting procedure ECG Flanker cognitive task (as attentional task) Spectral power of theta and alpha frequency oscillations of the spontaneous EEG and the TF; HEBR |

↓ PCL-5 ↑ spontaneous alpha power (8–13 Hz) in the posterior electrode cluster but ↔ in the follow-up analysis ↑task-related frontal theta power (4–7 Hz in 140–220 ms after stimulus) ↑ frontal theta heartbeat-evoked brain responses (HEBR) (3–5 Hz and 265–336 ms after R peak). ↓ CAPS ↓ PHQ Type of treatment (MBSR, Control)→ frontal theta heartbeat evoked brain responses→ PCL-5 |

| 7 | Somohano & Bowen, 2022 | Single cluster-randomized repeated measures design | 83 women with PTSD symptoms and substance abuse disorder (SUD) (30% ethnic minority); Mage= 36.1 (SD= 7.9) |

PTSD-SUD | Mindfulness, trauma-focused and gender responsive Program (Ti-MBRP) |

4 weekly sessions (one hr for each) | For PTSD symptom severity in primary care settings: BSSS; PACS; Acceptability: homework compliance and course satisfaction; self-reported duration of formal practices and frequency of informal practices Feasibility: recruitment, enrolment, and retention. Satisfaction: OCSS |

↓Craving (PACS) and PTSD symptoms (BSSS) in both conditions over the 12-month follow-up period and effect sizes similar to other PTSD-SUD interventions ↑Larger effect of Craving and PTSD in both programs after 1-month ↓MBRP had lower BSSS at post-test and 1-month follow-up in comparison with TI-MBRP; TI-MBRP acceptability: homework practice was as expected (in both conditions), retention was below the target but 60%; attrition was higher (64%) at post-test and 1-month follow-up in Ti-MBRP than in MBRP. High satisfaction (OCSS). |

| 8 | Somohano et al., 2022 | Pilot RCT with follow-up | 23 women; Mage= 36.1 (SD= 7.9); most users of methamphetamines, with PTSD symptoms and substance abuse disorder (SUD) |

PTSD-SUD | Mindfulness- based relapse prevention (MBRP) program |

8 sessions (one hour for each) in a 4-week period | PCL-5; PACS; self-reported minutes of daily meditation practice, and self-reported frequency of daily engagement in mindfulness skills to everyday activities | Higher duration (i.e., minutes per practice) of formal mindfulness practice → lower PTSD Symptoms (avoidance, arousal, reactivity, negative cognitions and mood in PCL-5) at 6-month follow-up; ↔Informal practice did not predict any outcomes. ↔Formal and informal practice did not predict reduction in intrusion symptoms (PCL-5) and craving at 6-month follow-up. |

| 9 | Gibert et al., 2022 | RCT with active control | 34 people (Dive Group=17); (32,4% women); Mage= 36 (SD= 6,9) |

PTSD from Paris terroristic attack of 2015 | Scuba diving with mindfulness exercises (the Bathysmed protocol) | 6 days with 10 dives | PCL-5; FMI | ↔PCL-5 at post-test but: ↓Subscale Intrusion symptoms (PCL-5) at post-test and 1-month follow-up; ↑ Mindfulness (FMI) at Post-test; Large effect size Cohen’s d at 1-month follow-up; ↔ PCL-5 and FMI at 3-month follow-up |

| 10 | Possemato et al., 2022 | RCT with active control and follow-up | 55 primary care veterans | PTSD from Combat | Primary Care Brief Mindfulness Training (PCBMT) | 4 weeks | PCL-5; PHQ-9; Health responsibility; Stress management; Not feeling dominated by symptoms | ↓ PTSD symptoms at post-test ↓Depression at 16-24 months follow-up ↑Health responsibility ↑Stress Management, not feeling dominated by symptoms. |

| 11 | Classen et al., 2020 | RCT with waitlist and follow-up | 32 women; Mage =43.5(SD= 10) Eligible if they had previous group experience |

Childhood trauma, complex PTSD symptoms. | Trauma and the Body Group (TBG) | 20-session program (hr for each): | CTQ-SF; LSCL-R; SBC; BAI; SRS; PCL-5; SDQ-20); DES; BDI-II; PHLMS; IIP-32 | ↑Body awareness subscale (SBC) ↔ Body dissociation subscale (SBC) ↓ Anxiety (BAI) ↑Soothing receptivity (SRS) ↔ PCL-5; SDQ-20; DES; PHLMS; IIP-32 ↓ BDI-II |

| 12 | Gallegos et al., 2020 | RCT with active control and follow-up | 29 women (65% in MBSR group); Mage 42.7 (SD=13.1); 50% Black, most unemployed and applying for order of protection |

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Survivors | MBSR | 8 weekly sessions | IPVE; LEC-5; PCL-5; DERS; UFOV; RMSSD between normal heartbeats during a 5-min rest period and a sub-sequent trauma imagery task | No statistical power to test between-group differences; Time effects in MBSR group: Improvement but ↔ divided and selective attention (UFOV) ↔ HRV by RMSSD but increase ↓DERS ↓PCL-5 at post-test and follow-up. Decrease for 50% of the total of participants. |

| 13 | Nguyen-Feng et al., 2020 | RCT | 64 women | PTSD and childhood interpersonal trauma histories |

Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) |

1 hr weekly for 10 weeks |

SLESQ; CAPS; DTS; BDI-II; DES; IASC | TCTSY was most efficacious for those with fewer adult-onset interpersonal traumas. Within this subgroup, TCTSY was more effective in reducing PTSD than the active control condition. clinician-rated PTSD, selfreported PTSD, and emotional control problems, although effects were relatively small to moderate. The efficacy of the intervention conditions was less predictable among those with a history of greater adult-onset interpersonal trauma. |

| 14 | Davis et al., 2020 | RCT with 7 months follow-up | 209 participants (91.4% veterans; 66% male; 61.7% White) who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD Mage= 50.6 (SD= 12.9) |

PTSD (59,3% Combat-related index trauma) | Holistic Yoga Program (HYP); Wellness Lifestyle Program (WLP) | 16 weekly interventions | CAPS-5; PCL-5; | ↓PCL-5; CAPS-5 |

| 15 | Fortuna et al., 2020 | RCT with active control and follow-up |

341 Ispanic migrants (24% US and 76% Spain) (172 assigned to IIDEA); Age from 18 to 70 |

Dual diagnosis of Substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and chronic stress | IIDEA (Intervention for dual problems and early action) (CBT + Mindfulness). | Training of clinicians (Two days) who conducted 10-session IIDEA trial (1 hour weekly sessions) | Qualitative report on what was useful of the intervention (content analysis); WAI-SR; IMR; MAAS; ASI; Lite and urine test results; HSCL-20; GAD-7; PCL-10; PHQ-9 | Intermediary variables: ↑WAI-SR (alliance), MAAS and IMR (from a medium to small effect size) also at 6-month follow-up; Outcomes: ↓ Urine test and substance use ASI; PCL-10; GAD; PHQ-9; HSCL-20 (results shown in Alegria et al., 2019). Qualitative results: participants found more useful being listened without judgement, learning relaxation and emotional regulation techniques, gaining a sense of self-control, and managing the double diagnosis. |

| 16 | Lang et al., 2019 | Pilot RCT | 28 Veterans; Mage=49.6 (SD=16.2) |

PTSD from Combat | Cognitively-based Compassion Training (CBCT). | 10 weekly sessions (1 hr for each) | CAPS-5; PCL-5; PHQ-9; BSI-18; STAXI-2; Sleep-Related Disturbance Measures from NIH PROMIS; AUDIT-C; SCS-R; SCS; PHLMS; TEQ; RTSQ; DES’ |

↑ Social connectedness (SCS-R) ↓PCL-5, PHQ-9, CAPS-5 (subscale Hyperarousal), large effect size in hyperarousal, reexperiencing, negative alterations in cognitions Medium effect size in empathy, mindful awareness, anxiety, rumination Large effect size in depression ↔ Differential Emotion Scale (DES): Positive and Negative Emotions ↔Alcool Consumption and all the other variables |

| 17 | Cox et al., 2019 | Pilot RCT with follow-up | 80 allocated to mobile/telephone mindfulness (77,5%) or education (22,5%); 56,2% men; Mage= 49.5; admitted for a surgical or trauma diagnosis (69%) |

Post discharge of critical illness | Mobile and telephone mindfulness program (awareness of breathing; body systems; emotion and mindful acceptance, and awareness of sound) |

4 weekly sessions (hr for each) | System Usability Scale; CSQ; Rate of completion of the program; PTSS; GAD-7; PHQ-9; CAMS-R; Brief COPE; qualitative data: Report and rate the severity of perceived stressors, open-ended feedback on the app group | Higher drop-out and less CSQ in Mobile program ↓Similar decrease between Mobile and Telephone Mindfulness in PHQ-9, GAD-7; PTSS at 3 months follow-up; ↓Education program had a similar impact of Mindfulness Program on PTSS but less impact than others on PHQ-9 and GAD-7 at 3-months follow-up; ↔CAMS-R and Brief-COPE |

| 18 | Miller et al., 2019 | RCT with active control and follow-up | 35 adolescents; Mage= 12.9 (SD= 1,8); (37% female) 32 parents; Mage= 44.7 (SD= 9,8); (80% female) |

40% reported clinical levels of PTSD symptoms, related but not specific to COVID-19 Pandemic | Mentoring + mindfulness program (Learning to Breathe, L2B) | 4 mindfulness sessions (30 minutes each) in 12 weeks | Internalizing subscale of BPM; Child PTSD Symptom Scale on distressing events; PROMIS Sleep-Related Disturbance—SF, PROMIS Pediatric Physical Activity-SF; (REDS); (BRIEF), DERS-SF; FFMQ-SF | ↓ Child PTSD symptoms ↓Emotional impulsivity (DERS-SF) ↓Difficult in engaging in goal-directed behavior (DERS-SF) ↔Remaining variables |

| 19 | Jasbi et al., 2018 | RCT with active control (Citalopram + social meetings) | 48 male veterans; Mage=53 (SD=2,5) |

PTSD from combat | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) + Citalopram | 8 weekly sessions (60-70 minutes each) | PCL-5; DASS | ↓ PCL-5 (Re-experiencing the events, Avoidance, Negative mood and cognition, Hyperarousal) ↓ DASS (Depression, Anxiety, Stress) |

| 20 | Pradhan et al., 2018 | Pilot RCT with active control and follow-up | 20 subjects (60% female) with PTDS resistant to treatment as usual Age 30-60 |

Mostly physical sexual and emotional abuse | TIMBER (trauma Interventions using Mindfulness Based Extinction and Reconsolidation) combined with a single sub-anesthetic dose of ketamine. | 12 sessions (9 after the relapse of Ketamine or placebo) weekly 1 hr | PCL; CAPS; Ham-D; BAI; MoCA | ↑Duration of response in TIMBER-K (compared to TIMBER-Placebo): in average 34 days with no or minimal PTSD symptoms (PCL, CAPS) (twice longer than the remission with Mindfulness Therapy alone and 5-fold longer than Ket therapy alone); ↓PCL and CAPS at the relapse were lower than the pre-test; ↔the average DSR (Serine) Plasma Concentration was lower than basal DSR (but not significant) ↔Positive correlation but not significant between DSR and PTSD severity |

| 21 | Romaniuk et al., 2023 |

Uncontrolled Clinical Trial with 3-month follow-up | 12 couples (50% male); Mage= 61.90 (SD= 11.09) for the males Mage=61.33 (SD= 8.65) for the females; Ex-service personnel of Defence Force with PTSD and their female partners. |

PTSD from combat | Compassioned Mind Training (CMT) compared to Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) based on psychoeducational skills. | 12 biweekly group sessions 2 hr each) | FCS, FSCRS, OAS, SSPS, Depressive experiences questionnaire—Self-criticism subscale, PCL-5, DASS-21, Q-LES-Q-SF, RAS, Post-program feedback questionnaire. | ↓ fear of compassion (FCS) towards others and self from pre-test to follow-up ↓ feelings of self-inadequacy (FSCRS) from pre-test to follow-up ↓ levels of external shame (OAS) at follow-up ↓ PCL-5 in the ex-service personnel ↓ Anxiety (DASS-21) at follow-up. ↓ Stress (DASS-21) at follow-up. ↔ PCL-5 in the partner group ↔ Depression (DASS-21) ↑ social safeness (SSPS) at follow-up ↑ Quality of life and satisfaction (Q-LES-Q-SF) at post-test but not at follow-up ↑ Relationship satisfaction (RAS) at post-test but not at follow-up |

| 22 | Leach & Lorenzon, 2023 | RCT with active control (facilitated group support) and two month-follow-up | 42 women; Mage 47.8 (SD= 12.3); Most unemployed/retired (57.1%) and had experienced domestic violence more than 12 months ago (64.3%). |

Traumatic experience of domestic violence | Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique | 9 individual and group sessions (1–2 hr each): tot 12 h in 8 weeks | AQoL8D, DASS-21, PCL-5, subjective experience was assessed through open-ended questions in the data collection form and trial exit form. | ↓ DASS-21 depression, anxiety and stress severity scores ↓ PCL-5 Total Symptom Severity Score ↑ AQoL-8D utility score, superdomain scores and domain scores (except for pain and senses domain scores) ADVERSE EFFECTS Twelve mild adverse events reported by six participants (i.e. nausea, headache, irritability, weight gain). Two participants self-reported a severe adverse event that they believed was related to the intervention (i.e. cold-sore, body feeling heavy). |

| 23 | Javidi et al., 2023 | RCT with active control, Cognitive Therapy and Behavioral therapy (BT) | 82 participants with a diagnosis of depressive disorder or PTSD; Mage= 40.3 years (SD= 12.0); The dominant level of education was secondary school (45.2%), while 35.5% were students and 30.6% employed |

PTSD for non specified traumatic experiences | Self-Compassion Therapy combined with Behavioural Therapy (BT) | 12 session program of individualised CBT-based treatment for depressive disorders and PTSD | SCS, K10, PHQ9; PCL-C; WSAS. | ↑ SCS ↓ K10 ↓ PHQ9 ↓ PCL-C ↓ WSAS |

| 24 | Knabb et al., 2022 |

RCT with control group (Loving Kindness Meditation) | 26 participants belonging to Christian religion; Mage= 42,8 (SD=12,80 ); | Exposure to crime related events, physical and sexual experiences and general disasters | Christian Meditative Intervention (Lectio Divina) | 2 weeks | Christian Contentment Scale; Christian Gratitude Scale; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; Trauma Symptom Checlist-40 | ↓ PTSD symptoms ↔ Positive affect (small effect size) ↔ Christian contentment ↔ Christian gratitude ↔ Anxiety, depression, stress (medium effect size) |

| 25 | Fishbein et al., 2022 |

RCT with active control (MEUC, Minimally enhanced usual care) | 134 (88% female); Mage= 56.24 (SD=11.58). |

Cancer survivors | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) | 10 sessions | Mediators: SCS; BEAQ; BEVS; VLQ; EAC. Outcomes: HADS; IES-R; CARS. |

↓ Bull’s eye Values BEVS (improvement) ↔VLQ ACT →SCS, EAC→IES-R ACT→SCS, EAC, BEVS→ CARS and General Anxiety HADS-A (marginal mediation) ↑SCS ↑ EAC |

| 26 | Bellehsen et al., 2022 |

RCT with active control (Treatment as Usual) and 3-month follow-up | 40 veterans (85% male); Mage=51.6 (SD= 11.4); Non caucasian (42.5%). |

PTSD from Combat (60%), sexual trauma (15%)Life-threatening illness/serious injury (15%), other (5%) | Transcendental Meditation (TM) | 16 sessions over 12 weeks (1 hr each). |

CAPS-5; PCL-5; BDI-II; BAI; S-Anger subscale of STAXI-2; Q-LES-Q-SF; ISI. | ↓PCL-5; BDI-II; BAI; ISI; ↓50% TM group reduced CAPS-5 and 50.0% no longer met the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis after 3 months ↔S-anger ↔Q-LES/ Q-SF |

| 27 | Gerdes et al., 2022 |

Uncontrolled Clinical Trial | 56 veterans (92.9% male); Mage= 52.1 (SD= 12.9). |

PTSD from Physical injury on deployment (48.2%) and from combat (32.1%) | Listening to the compassion meditation (LKM-S) | 1 session audio-taped (1.5 h) |

HR and HRV from ECG; SCL; ERQ; PCL-5; PHQ-9; VAS. |

↓ self-reported hyperarousal state ↓ SCL, meaning a reduction in sympathetic arousal ↔HRV response was not different from 0, meaning that did not increase parasympathetic activation (no as expected an increase) ↔ Social Connectedness State self-compassion at both pre and post time points were associated with PCL-5, trait self-compassion (SCS) and emotion suppression (ERQ) ↑HR response (physiological arousal) (not as expected a decrease) ↑HR response to directing compassion towards the self ↑ self-compassion state at the end of LKM |

| 28 | Hodgdon et al., 2022 |

Uncontrolled Pilot Clinical Trial with 1 month follow-up | 17 participants (76% women); Mage=46; range 28-58 76% exposed to two types of trauma prior to the age of 18; and current diagnosis of PTSD on the CAPS and clinical depression. |

PTSD from Multiple Childhood Trauma with sexual (65%), psychological (65%) and physical (59%) abuse |

Internal Family System therapy (IFS) | 16 individual sessions (1,5 hr) | DTS; CAPS; BDI; SIDES-SR; SCS; MAIA. | ↓CAPS at post-test and 1-month follow-up At 1-month follow up, 92% of participants no longer met criteria for PTSD ↓DTS at post-test and 1-month follow-up ↓ BDI at post-test and 1-month follow-up ↓SIDES total score at the 1-month follow up ↔Somatization ↔SCS ↑ Large effect size on Trusting and medium effect sizes on Attention Regulation, Self-Regulation and Body Listening ↑Not-Distracting subscale of MAIA just at 1-month follow-up ↔ No significant time effect for other subscales of MAIA |

| 29 | Staples et al., 2022 |

RCT with active control (standard treatment) and 2-month follow-up | 108 veterans (96% male); Mage 55.97 (SD=11,7). |

PTSD from combat; | MBSG (mind-body skills group) | 10 weeks | PCL- M; STAXI-2; PSQI; PHQ-9. |

↓ Hyperarousal and avoidance ↓ PTSD symptoms ↓ Anger and sleep disturbance ↔ Depression, anxiety, post traumatic growth and health related quality of life |

| 30 | Tibbitts et al., 2021 |

Retrospective pre-post approach | 152 students (59% woman), community of colour (44 %); 73% ≥ 21 years; 51% attended trauma-informed yoga classes in the corrections and reentry sector, 21% in the substance use treatment and recovery, 28% in community and mental health sectors. |

Not revealed | Trauma-informed yoga | From 2 to 10 Yoga Classes | Survey instrument: Not standardized questionnaire developed ad hoc informed by the framework of self-regulation to evaluate: self-regulation, perceived emotional and physical wellbeing. | ↓Reported decreased feeling pain or negative emotional states ↑Use of self-regulation skills was uniformly higher. ↑Reported increased awareness of physical sensations (e.g. breathing and muscle movement) ↑Students in the corrections and reentry sector had the largest benefit after beginning yoga. Adverse effects: For negative emotional states, only few students reported feeling upset, anxious, or stressed after class. Fewer respondents from substance use treatment retrospectively reported feeling upset and anxious or stressed before yoga class. This group showed the least amount of change in self-regulation skills |

| 31 | Grupe et al., 2021 |

RCT with 5 month follow-up | 30 police officers; Mage= 38,4 (SD= 7,7). |

Occupational stress | Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | 8 sessions in 8 weeks |

PSQ; OLBI with separate subscales for exhaustion and disengagement; PSQI; PCL-C); PROMIS; WLQ-8); PWB; PANAS; Creactive protein, diastolic/systolic blood pressure, resting pulse rate, skin conductance; Breath Count task. | ↓PSQ Operational stress and moderated by gender and years of police experience: younger men showed greater decline in stress also at follow-up; ↓ PCL at post-test and at 5-month follow-up; ↓ Exhaustion subscale of OLBI ↓PROMIS anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms; ↓PANAS Negative affect; ↔PROMIS subscales of pain interference; pain intensity, or physical functioning ↔ Disengagement subscale of OLBI ↔PANAS positive affect; ↔ Physical parameters ↑ Sleep quality PSQI ↑PWB; |

| 32 | Kananian et al., 2020 |

RCT with waitlist and 12-weeks and 1-year follow-up | 24 male; Mage= 22.1 (SD=3.6); refugees diagnosed with DSM-5 PTSD, major depressive disorder, and anxiety disorder; with elementary school degree. |

Multiple trauma pre-post displacement | Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy (CA-CBT) | 12 sessions in 6 weeks (1.30 hr for each) | GHQ-28; PCL-5; PHQ-9; SSS-8; WHOQOL-BREF; ERS. | ↓ PHQ-9; SSS-8; ↔PCL-5 ↑WHOQOL-BREF ↑ERS ↑GHQ-28 at both follow-up; At 1-year follow-up main effects were maintained |

| 33 | Schuurmans et al., 2021 |

RCT versus TAU | 77 adolescents (59.7% male); Mage= 15.25 (SD = 1.79). |

PTSD from non-intentional multiple traumatic events (e.g. neglect, domestic violence, emotional abuse, interpersonal traumatic events) | MUSE (game-based meditation intervention) | 6 weeks: 2 times a week for 15-20 minutes | Basal ANS activity using ECG and ICG by VU-AMS. Basal HPA axis activity using hC levels pg/mg hair. TRIER-C combined with SSST. |

↓ Basal activity of SNS (Sympathetic Nervous System) ↔ Reactivity of SNS and PNS (Parasympathetic Nervous System) to acute stress ↑ HPA (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis) reactivity to acute stress |

| 34 | Chopin et al., 2020 |

RCT versus control | 87 (61% male); Mage 51.41 (SD 11.32); 69 % African Americans; 49 completers (56,3%). |

PTSD with comorbid chronic pain | Hatha Yoga | 10 cohorts (2 to 8 weeks): 90 minutes for each class | PCL-5; PROMIS; Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8; TSK-11. | ↓ PTSD symptoms, kinesiophobia, depression and anxiety Follow-up results: ↔ Intrusion and avoidance symptoms ↑ Social role functioning PROMIS |

| 35 | Zalta et al., 2020 | RCT with 10 assessments | 165 veterans (64,2% male); Mage= 40.8 (SD= 9.57); most white; most who served After 9/11; most retired; with PTSD. |

Combat (67.9%), military sexual trauma (32.1%) and additional childhood trauma history (61.6%) | Intensive treatment program (ITP) | 3-week: 14 individual sessions of CPT, 13 sessions of group VPT, 13 session group mindfulness adapted from MBSR and 12 sessions of yoga | ISI; PCL-5-18; PHQ-8. | ↓ ISI in just 23.4%; ↓ PCL-5-18; PHQ-8 (already shown in Zalta et al., 2018) ↔ baseline ISI did not predict PCL-5 and PHQ-8 across all time points but larger improvements in ISI was associated with greater improvement in PCL-5 and PHQ |

| 36 | Bandy et al., 2020 |

Uncontrolled Pilot Clinical Study | 116 (61,2% women); Mage= 20.6 (SD= 2.75); South African students in experimental group with PTSD (PCL-C >44); 61 (70,5% women) in the waiting list: 34 participants also met DSM-IV criteria in a clinician’s diagnosis. |

Several among natural disasters, severe accidents, sexual and criminal victimization and combat experiences | Transcendental Meditation (TM) | 4 consecutive days (1.30 hr daily), and weekly follow-up meetings and home practices | PCL-C; Trauma history Questionnaire; BDI. | ↓PCL-C in experimental group after 15, 60 and 105 days of practice. In this point, PCL-C was not symptomatic anymore. ↓BDI at both 60 and 105 days ↓ BDI Depression and PTSD were highly correlated and decreased together through the practice; Regular TM practice predicted ↓PCL-C especially during the first 15 days of practice |

| 37 | Zaccari et al., 2020 |

Uncontrolled Clinical Trial | 27 veterans; final sample (N = 17), 41% endorsed military sexual trauma (85% of women and 10% of men). Of participants who completed postintervention assessment (male n = 10 and female n = 7), 11 attended eight or more classes, four attended five to seven classes, and two attended three classes. |

PTSD from combat | Yoga protocol | 10 weeks | Response Inhibition; PTSD symptoms; depression; sleep disorder; quality of life; neurocognitive complaints. Cognitive functioning, self-report measures of mental health symptoms, and salivary cortisol were measured within two weeks prior to beginning and following completion. |

↑ Life satisfaction ↓ depression, cortisol ↔ cognitive performance |

| 38 | Muller-Engelmann et al., 2019 |

RCT with multiple weekly assessments until 8 weeks follow-up |

14 (78,6% women); Mage=41.14 (SD= 12.30); PTSD patients; 92.9% fulfilled the criteria for comorbid affective or anxiety disorders. |

Interpersonal violence Childhood sexual or physical abuse; Physical violence in adulthood |

Trauma-adapted intervention from loving-kindness meditation and MBSR | 8 individual sessions (1.30 hr for each) | CAPS-5; SCID-I; IPDE; LEC-5; DTS; BSI; BDI-II; WHO-5; FFMQ; SCS; MBE. | ↓CAPS-5 at follow-up (especially on avoidance) (9 out of 12 did not meet PTSD criteria); ↓DTS at post-test and follow-up; ↓BDI-II at follow-up; ↓ self-criticism at follow-up ↔BSI medium effect sizes ↑mindfulness skills of nonjudging and acting with awareness ↑ attention to breath in MBE at follow-up ↑self-compassion at follow-up ↑WHO-5 (75%): half of them at post-test |

| 39 | Ong et al., 2019 |

Collective case study design | 3 women; Age from 26 to 52; PTSD who have left the abusive relationship for at least 6 months. |

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) | Trauma-sensitive Yoga (TSY) | 8 group sessions in 8 weeks (1 hr for each) | CAPS-5; SUD; pre- and post-TSY scaling question worksheet observations on how they made meaning of their recovery; semistructured interviews. | ↓CAPS-5 (but one for floor effect): reduced number and severity Enhanced physiological, intrapsychic functioning, emotional benefits, enhanced perceptions of self and others, shift in time perspective, interpersonal relationships, self-care, spiritual benefits and positive coping strategies. |

| 40 | Mehling et al., 2018 |

RCT with waitlist and multiple assessment (4,8,12 weeks) | 47 (81% male); Mage =46.8; from 24 to 69 war veterans with PTSD and from racial or ethnic minority (60%). |

PTSD from Combat | Integrative exercise (IE) | 36 sessions in 12 weeks (50 min for each) | FFMQ; MAIA; PSOM; CAPS-5; WHOQOL. | ↓CAPS-5 (average reduction of 31 points) ↑FFMQ Non reactivity, Observing ↑ MAIA Emotional Awareness, Self-Regulation, Body Listening; ↑PSOM total, Focused Attention, Restful Repose PSOM and FFMQ Non-Reactivity → CAPS Hyperarousal subscale/ Psychological WHOQOL (partial mediation) |

| 41 | Goldstein et al., 2018 |

RCT with waitlist and multiple assessment (4,8,12 weeks) | 47 (81% male); Mage= 46.8 (SD= 14.9); war veterans with PTSD, mostly and from racial or ethnic minority (60%). |

PTSD from Combat | Integrative exercise (IE) | 36 sessions in 12 weeks (1 hour for each) | SCID-I; CAPS-5; WHOQOL-BREF; Feasibility and Acceptability Questionnaire; Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire. | ↓CAPS-5 Tot. 31 point reduction at post-test ↓Subscale of hyperarousal ↑ LSI (more physical activity) ↑WHOQOL-BREF greater improvement in the psychological domain but a smaller improvement in the physical domain greater number of sessions attended was associated with an improvement in physical quality of life and psychological quality of life High levels of satisfaction |

| 42 | Reinhardt et al., 2018 | RCT with waitlist | 51 (11.8 % female); Mage= 47.76 (SD= 13.77); (out of 74 participants screened). |

PTSD from Combat | Kripalu Yoga Program | 20 sessions in 10 weeks (1.30 hr for each) | PTSD Checklist (PCL-C and M); CAPS-5; IES-R. | CAPS-5 up to moderate PTSD symptoms at post-test in Yoga group but ↔ between differences in CAPS, PCL-M and IES ↓ large effect PCL-M (correlated with PCL-C), self-reported PTSD symptoms were reduced in the yoga group (below the cutoff) while marginally increased in the control group, 51% drop out (higher in the Yoga Group), Self-selectors (from Waitlist) improved more than Randomized Veterans in CAPS and PCL. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).