1. Introduction

In the last 20 years, businesses and people have become more worried about environmental problems and how people’s actions affect the Earth. Consequently, many companies are working hard to support “green” methods and have slowly changed their rules and operations to reflect this worldwide concern for the environment [

1]. Companies are creating new goods and services, ways of making things, and ways of doing business that are meant to protect the environment from damage, pollution, and other problems. They do this because they know that it is important to do so to help businesses and society achieve a sustainable environment [

2,

3,

4]. Many contributions show that adopting green innovations doesn’t always lead to financial gains. To gain a competitive edge, especially when related to manufacturing innovations and increasing the chances of surviving [

5], firms may need to cut costs to increase their productivity, open up fresh market possibilities, promote differentiation tactics, and improve their public image. The natural resource-based approach states that to preserve competitive advantages and level off EP, businesses should keep an eye on and take advantage of green business opportunities [

6].

Nevertheless, given their unique characteristics regarding other innovations [

7,

8] creating green innovations—also referred to as environmental innovations—is not an easy task. This raises significant managerial concerns for businesses that want to significantly reduce their environmental impact. Businesses frequently need to explore new external knowledge sources in addition to their current industrial knowledge base when developing innovations. According to Cainelli et al. (2015) [

9], this type of innovation demands a wide range of resources and involves a high degree of novelty and uncertainty. Indeed, numerous studies have demonstrated the (unique) significance of collaborating with stakeholders to successfully implement environmental innovations [

10]. However, less is known about the company’s internal ability to acquire relevant knowledge flows and turn them into goods or services that address environmental concerns.

This study explores the enterprises’ capacity to learn from outside sources as a crucial precondition for the effective adoption of green innovation to fill this gap in the literature. More precisely, we concentrate on two components that make up this internal capability relationship learning, which is the capacity to share information and knowledge with supply chain partners [

11] and absorptive capacity, which means being able to use the information that stakeholders create to make new goods, services, or methods [

12].

Core skills have been identified in prior research as a crucial component of enhancing organisational performance using a variety of knowledge-based tactics to promote GI [

13]. Organizational sustainability is mostly determined by further GI [

14]. An organization’s internal and external resources and capabilities, arranged and integrated into all of its operations and tasks to prevent negative effects on the environment and organisational sustainability, might be considered its “green core competence” (GCC) [

15]. Furthermore, absorptive capability and organizational sustainability have been found to positively correlate by Shahzad et al. (2020) [

16]. Gaining a competitive edge over rivals is a crucial component of many industries worldwide. The ability to sense and adapt to changes in the external environment is a crucial component of the integration of green resources and capabilities [

17]. To attain GI, GAC could change the sheer amount of knowledge resulting from relationship learning and green core skills. According to Cao and Ali (2018) [

18], absorptive capacity is crucial since it can foster team innovation and knowledge production. Additionally, earlier research has shown that stakeholders influence organizations to spend money on organizational learning and knowledge management to reduce ecological risk, which impacts green organizational innovation [

19,

20]. Nonetheless, academic research has not yet examined the concept of GCC to improve GAC and green creativity. However, the fundamental skills as a whole were not given much attention by researchers, although they could be essential to eco-friendly product and process improvement. Due to this gap, researchers concluded that by integrating environmental issues and establishing what are known as “green core competencies,” core competencies might be included in the tourism sector. According to Prahalad and Hamel (2009) [

21], researchers have previously examined the phenomenon of core competencies as a crucial ability to attain a variety of results in many businesses. But this study looks at the effects of GCC on a different area: the tourism business. The thought is also put forward that the tourism industry needs to change with the times and create a GCC in order to reach GI and GAC.

However, the real issue of how these core competences may be applied throughout the various departments of a particular business to enhance or accomplish GI may still be faced by some hotels and restaurants. Because of this, this study also suggested GAC as a mediator that will facilitate the actual application of key skills to attain GI. According to Chen & Lin (2014) [

22], it is also thought that companies with a strong green organizational culture may find it comparatively simple to increase GI by transforming their GAC.

Furthermore, this research aims to examine the impact of GAC on CSP, considering the dual mediating roles of GI and EP, and the moderating role of GOC. Driven by this central objective, “the study intends to address the following research questions:

RQ1. How does green absorptive capacity influence corporate social performance?

RQ2. Does green innovation mediate the relationship between green absorptive capacity and corporate social performance?

RQ3. Does environmental performance mediate the relationship between green absorptive capacity and corporate social performance?

RQ4. Does green absorptive capacity positively influence green innovation and environmental performance?

RQ5. Does green organizational culture moderate the relationship between green absorptive capacity and green innovation?

This research offers several significant contributions to the field of sustainable management and green innovation:“

Firstly, the study contributes to the relatively limited literature on how GAC, as a dynamic organizational capability, drives corporate social performance through GI and EP. While absorptive capacity has been widely examined in innovation literature, its specific green dimension and its impact on CSP remain underexplored, especially in the context of developing economies.

Secondly, this research advances knowledge by empirically testing the mediating roles of GI and EP in the relationship between GAC and CSP. Previous studies have often examined these constructs in isolation, without integrating their interconnected mediating pathways. By analyzing these dual mediators simultaneously, the study adds clarity to the mechanism through which GAC enhances CSP.

Thirdly, this study introduces the moderating effect of GOC on the relationship between GAC and GI. Prior research has acknowledged the influence of culture on innovation, but has not sufficiently addressed how GOC might shape the conversion of green knowledge into green innovation outcomes. This moderating effect sheds light on contextual factors that can amplify or suppress the influence of GAC.

Lastly, the findings of this research have important practical implications for policymakers, sustainability professionals, and business leaders. The results offer clear insights into how companies—especially those in resource-intensive or high-impact sectors—can strengthen their environmental and social performance by improving their internal green capabilities and fostering a culture that supports sustainability. This study also supports the development of effective green policies, training initiatives, and strategic planning to promote long-term sustainable growth and environmental responsibility.

2. Literature Review/Hypothesis Formulation of the Study

2.1. Green Absorptive Capacity and Green Innovation

Environmental protection as a top priority and good environmental management in an organisation’s goods design or manufacturing procedure is called “green innovation”[

23]. The importance can be seen in how companies use a GI strategy to combine outside knowledge with their own experience. The significance of absorptive ability in GI is emphasised by this. Effectively using external as well as internal skills can help businesses come up with new ideas that are better for the environment [

24]. GI and GAC’s relationship is a key topic for study in managing the environment and sustainable development. This research says that GAC is very important for figuring out the GI for Pakistani small and medium-sized industrial businesses.

2.2. Green Absorptive Capacity and Environmental Performance

“Green absorptive capacity” is the organisational method that helps companies get, change, and use green technology knowledge from outside sources. Businesses that can absorb more information are said to be better able to use green information from outside their operations, which could lead to improved EP [

25,

26]. The body of study on the subject is very important for figuring out the connection between GAC and EP. Many studies have looked at how absorptive ability can help to promote GI and improve EP. Additionally, provide empirical data that improves understanding of the factors influencing the performance of GI. They highlight how important green absorptive capacity is, illuminating its significance in promoting green innovation. This is then thought to have a favourable effect on EP. According to this study, GAC significantly contributes to the advancement of green innovation and firm performance. This is likely to be good for the environment and the success of green innovation.

2.3. Green Innovation and Corporate Social Performance

The study examines the link between CSR practices and the advancement of “green” technologies in the context of a developing nation experiencing rapid economic expansion. The number of green patents awarded indicates a strong correlation between increased green technology innovation and improved CSR ratings. This was discovered using data from the listed firms and Rankin’s CSR Ratings of China for the years 2009 through 2017. Corporate social success is linked to new green technologies, according to the results. There is also a positive link between the number of green technology patents and the CSR rating, which is strengthened by overused extra resources [

27]. To speed up a company’s product development, many new ideas, such as changing the way managers do their jobs and putting in place modern technology and providing timely information [

28]. It has been looked at how companies that take action to protect the environment do better by using the Natural Resource-Based View as a theoretical framework. Additionally, we have tried to bring a fresh point of view to the discussion about the performance of environmental management firms by suggesting that environmental product innovation and marketing skills can work together to improve performance. Our study shows how the green image of 157 Spanish metal companies affects the nexus between environmentally friendly product innovations and the performance of the companies. It’s clear from the data that the company’s green image needs to be managed well “[

29].

2.4. Environmental Performance and Corporate Social Performance”

Environmental issues have taken centre stage in corporate social responsibility (CSR) in recent years, particularly as companies are under increasing pressure to implement sustainable practices. CSP is increasingly thought to be significantly influenced by a company’s EP, which is demonstrated by its initiatives to manage waste, cut emissions, conserve resources, and employ clean technologies. By actively protecting the environment, a business not only improves its reputation but also builds stakeholder trust, which raises its CSP overall [

30]. Strong EP firms are more likely to comply with environmental and social rules and report more transparently, both of which enhance their perceived social responsibility [

31]. Better EP is also linked to efficiency and innovation, indicating ethical corporate practices and responsible governance, two important components of CSP. According to Konar and Cohen (2001) [

32], companies that lower environmental risks through better EP are rewarded in the marketplace by gaining more investor confidence and a better reputation, two important aspects of CSP. Furthermore, Luo and Bhattacharya (2006) [

33] show that environmental responsibility boosts brand loyalty and customer happiness, both of which support CSP. Even with the growing amount of research highlighting the significance of EP, many studies continue to ignore its direct impact on CSP. This study tries to fill that gap by looking at how improved EP affects CSP in the real “world.

H4: Environmental Performance has a positive relationship with corporate social performance.

H7: Environmental Performance mediates the relationship between green absorptive capacity and corporate social performance”

2.5. Green Innovation and Environmental Performance

Organisational efforts to meet and beyond societal expectations about the natural environment, rather than only adhering to rules and regulations, are referred to as environmental performance [

34,

35]. Meeting environmental standards requires organisations to think about how their activities, goods, and use of resources impact the environment [

36]. “Prior research has demonstrated that a number of factors, including the caliber of eco-friendly products, the creation of green products and processes, and the degree to which environmentally sustainable concerns are incorporated into business operations and product design, have an impact on EP [

37,

38]. GI is known to improve EP and is associated with a robust environmental management strategy [

39], and it also improves a company’s financial and social performance by reducing waste and costs, in addition to reducing its negative environmental impact [

40]. Based on earlier studies, GI should be seen as an organization’s proactive goal and practice to enhance environmental performance in order to gain a competitive advantage, rather than as a reactive reaction to stakeholder pressures [

41]. Top managers need to find and take advantage of profitable eco-business opportunities and improve the performance of GI [

42,

43]”. Using the RBV, we forecast that a company’s usage of green processes and product innovation is essential for improving its EP and gaining the trust of stakeholders.

2.6. The Moderating Effect of Green Organizational Culture

A managerial team’s collective set of values, beliefs, and ideas that shape organisational behaviour and attitude towards accomplishing shared business objectives is known as organizational culture [

44]. Therefore, a GOC believes that protecting the earth is an essential component of the business. The goal statement includes it in a manner that makes everyone on the team feel responsible for preserving the environment [

45]. The way the organisation views environmental issues has changed as a result of these organizational cultural shifts, and employees are now more concerned about these issues. Managers who care more about environmental preservation will foster a GOC [

46]. Green corporate culture is a transformation agent that challenges traditional ways of thinking [

47]. Therefore, fostering a GOC can be extremely important in encouraging staff members to take environmental issues more seriously. According to Banerjee & Kashyap (2003) [

48], an organisation can benefit from the formal framework of GOC, which is founded on “eco-environmental values,” to implement environmentally friendly improvements in its operations. GOC, according to Wang, may convert a company’s pro-environment approach into GI. However, an organisation can only benefit from a green organizational culture if it can address environmental concerns. GAC is thought to improve a company’s potential to achieve green innovation [

49]. Furthermore, employees’ concerns about environmental protection are heightened by GOC. Given that research indicates that a GOC promotes team members’ attitudes and behaviours towards environmental protection, it follows that if an organisation is capable of handling environmental issues, its organizational culture would further inspire employees to protect the environment [

50]. Therefore, workers will be more concerned about environmental issues if their organisation has a greener culture. GOC values encourage businesses to include green values in their operations to create green goods, according to scholars [

51].

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

Research design tells us about the detailed framework of the investigation. Quantitative methods will be adopted to highlight the important facts and thereby present statistical relationships among the variants studied.

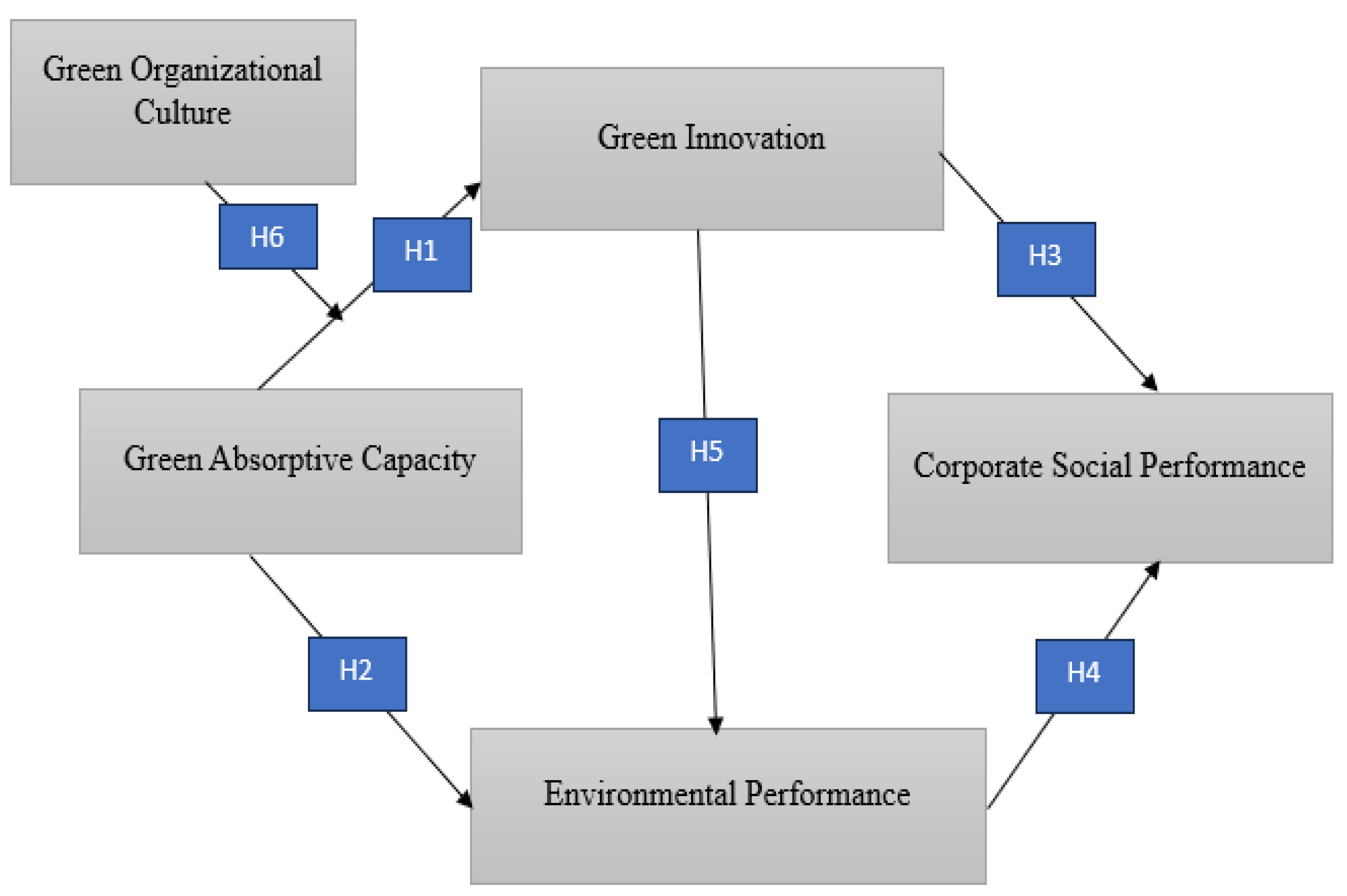

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework. Source: Author’s own

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework. Source: Author’s own

3.2. Objectives of the Study

To analyze the impact of green absorptive capacity on green innovation.

To investigate how GAC influences environmental performance.

To examine the relationship between green innovation and corporate social performance.

To explore the link between environmental performance and corporate social performance.

To assess the influence of green innovation on environmental performance.

To investigate the mediating roles of GI and EP in the relationship between GAC and CSP.

To evaluate the moderating effect of green organizational culture on the relationship between GAC and GI”.

3.3. Method

During data collection, the investigation implemented a cross-sectional methodology. The inspectors tried to get a bigger sample of data to better understand what was going on at the time. This methodology is appropriate for this empirical investigation at the organisational level. The survey questionnaire contains six components: the demographics of the selected companies (e.g., age, firm size), GAC, GI, EP, CSP and GOC. The questionnaire is designed to be reliable and valid by adhering to established scales that are appropriate for the research environment. Environmental practices measurement items were reevaluated and revised to enhance their clarity. Construct measurements were conducted using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

3.4. Data Collection

The data are obtained from a few carefully chosen companies in India. The companies were chosen for this study due to their substantial market shares in India, their eagerness to contribute data for this research, their reports’ evident interest in sustainability and their growing involvement in CSR initiatives and disclosures. Twenty companies were contacted and consented to participate in the investigation. The industries that these companies operate in include textile manufacturing, industrial services, infrastructure construction, and farm apparatus and equipment. We chose employees from the companies on purpose, like the CSR manager, the green manager, and the environmental officer, who know about the company’s green innovation strategies. Once everyone agreed, 550 questionnaires were sent at random to company employees via QR codes, emails, and phone calls. The study’s objective was briefly delineated in each questionnaire, and participants were guaranteed anonymity. The respondents were also informed that they would be able to obtain the final findings if they submitted a complete questionnaire. To increase the effectiveness of the response rate, follow-up calls and emails were implemented every two weeks following the initial mailing. 280 of the 550 questionnaires received were satisfactorily completed and approved.

3.5. Analysis Technique

The study employs a flexible data collection period and a multiple-method research approach. Correlation analysis is done to look at likely connections between variables. SmartPLS 4 program [

52] is applied to perform SEM to test the study hypotheses using variance-based PLS-SEM, which is suitable for evaluating complex multivariate data. The study covers formative predictor elements, including the attraction of businesses in developing countries.

4. Analysis and Interpretation

4.1. Data Analysis

The data collected in this study is utilized to explore the relationship between variables among employees in India. Key patterns and relationships are identified through exploratory and inferential data analysis, including the use of descriptive statistics, reliability and validity assessments, and structural equation modelling. Specifically, the analysis investigates how GI and EP mediate the relationship between GAC and CSP. Furthermore, the study examines how GOC moderates these relationships, providing deeper insights into the mechanisms that drive effective environmental and social outcomes within organisations.

Table 1.

Respondents’ Profile (n=280).

Table 1.

Respondents’ Profile (n=280).

| Classification |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Gender |

|

|

| Male |

110 |

39.3 |

| Female |

170 |

60.7 |

| Total |

280 |

100.0 |

| Firm Age |

|

|

| Less than 20 years |

60 |

21.4 |

| 20-50 years |

100 |

35.7 |

| More than 50 years |

120 |

42.9 |

| Total |

280 |

100.0 |

| Firm Size |

|

|

| Less than 1000 |

45 |

16.1 |

| 1000-5000 |

110 |

39.3 |

| More than 5000 |

125 |

44.6 |

| Total |

280 |

100.0” |

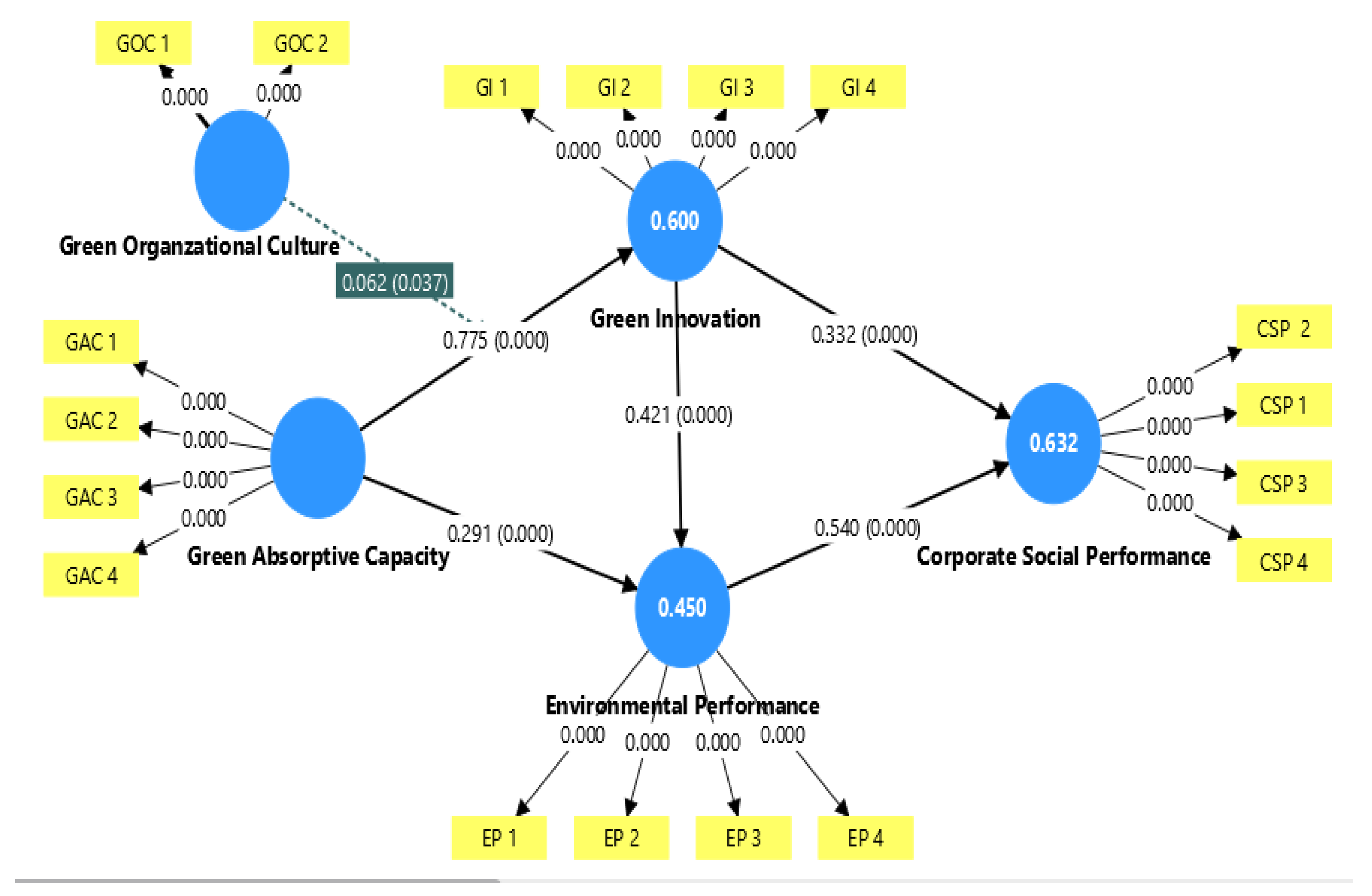

Figure 2.

Model Result. Source: SmartPLS4.0

Figure 2.

Model Result. Source: SmartPLS4.0

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the constructs used in the study, including mean, standard deviation, excess kurtosis, skewness, and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor). The results indicate generally positive responses across all variables, with mean scores ranging from 3.18 to 3.92. Constructs related to CSP, EP, GAC, and GI show moderate to high levels of agreement, suggesting that respondents recognize and support green practices and performance indicators within their organisations. Notably, CSP3 (Mean = 3.918) and CSP4 (Mean = 3.904) received higher ratings, reflecting strong perceptions of corporate social initiatives.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

| |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Excess kurtosis |

Skewness |

VIF |

| CSP 2 |

3.754 |

1.011 |

0.207 |

-0.763 |

3.678 |

| CSP 1 |

3.539 |

1.247 |

-0.775 |

-0.540 |

1.267 |

| CSP 3 |

3.918 |

1.078 |

-0.286 |

-0.765 |

4.750 |

| CSP 4 |

3.904 |

1.076 |

0.060 |

-0.861 |

4.586 |

| EP 1 |

3.582 |

1.242 |

-0.764 |

-0.549 |

4.971 |

| EP 2 |

3.596 |

1.145 |

-0.743 |

-0.453 |

4.239 |

| EP 3 |

3.650 |

1.213 |

-0.813 |

-0.511 |

4.031 |

| EP 4 |

3.489 |

1.192 |

-0.553 |

-0.572 |

4.283 |

| GAC 1 |

3.904 |

1.032 |

-0.578 |

-0.589 |

2.311 |

| GAC 2 |

3.864 |

1.054 |

-0.145 |

-0.739 |

2.269 |

| GAC 3 |

3.836 |

1.022 |

-0.123 |

-0.756 |

2.306 |

| GAC 4 |

3.704 |

1.181 |

-0.664 |

-0.612 |

1.398 |

| GI 1 |

3.714 |

1.179 |

-0.691 |

-0.613 |

3.187 |

| GI 2 |

3.750 |

1.144 |

-0.323 |

-0.721 |

3.329 |

| GI 3 |

3.754 |

1.153 |

-0.464 |

-0.717 |

4.524 |

| GI 4 |

3.686 |

1.178 |

-0.507 |

-0.649 |

4.480 |

| GOC 1 |

3.179 |

0.980 |

-1.073 |

0.024 |

1.558 |

| GOC 2 |

3.439 |

0.834 |

0.135 |

-0.047 |

1.558” |

The standard deviations are relatively consistent, indicating moderate variability in responses. Skewness values across most items are negative, suggesting a left-skewed distribution where respondents generally selected higher agreement levels. Kurtosis values, mostly close to zero or negative, suggest a relatively normal distribution of responses with no significant outliers. Meanwhile, the VIF values are below the threshold of 5 for most items, indicating acceptable multicollinearity levels, although a few constructs like CSP3 (VIF = 4.750) and EP1 (VIF = 4.971) approach the upper limit, suggesting a need for cautious interpretation. Overall, the data indicate a strong positive outlook toward green capabilities and their outcomes, supporting the validity of further inferential analysis in the study.

4.2. Internal Consistency and Validity

The PLS-Algorithm test was used to execute the measurement model analysis. The reliability and validity test was used to see if the measurement model was good.

Table 3 shows the results of the reliability and validity tests. We used Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR) ratings to check how reliable the measurement constructs. The values for construct CA should be higher than 0.70, and for CR, they should be higher than 0.80. So, the CA values ranged from 0.749 to 0.945, and the CR values ranged from 0.873 to 0.960. This indicates that all CA and CR values met the acceptable reliability thresholds suggested by [

53], confirming the internal consistency of the constructs. We also used the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values to assess construct validity. The AVE values for most constructs are above the minimum benchmark of 0.50, which confirms adequate convergent validity. All constructs achieved acceptable AVE scores, ranging from 0.671 to 0.858, demonstrating that the items adequately represent their respective constructs.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s α, Composite reliability and Average variance extracted.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s α, Composite reliability and Average variance extracted.

| |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Composite reliability (rho_a) |

Composite reliability (rho_c) |

Average variance extracted (AVE) |

| CSP |

0.873 |

0.888 |

0.911 |

0.720 |

| EP |

0.945 |

0.945 |

0.960 |

0.858 |

| GAC |

0.841 |

0.869 |

0.891 |

0.671 |

| GI |

0.938 |

0.938 |

0.956 |

0.843 |

| GOC |

0.749 |

1.139 |

0.873 |

0.777”” |

Table 3 demonstrates strong reliability and validity for all constructs. CA and CR values exceed the acceptable threshold of 0.70, indicating high internal consistency, especially for EP (0.945) and GI (0.938). All constructs also show good convergent validity, with AVE values above 0.50, most notably EP (0.858) and GI (0.843). Although GOC shows a high rhoₐ value (1.139), the overall results confirm that the measurement model is both reliable and valid for further analysis.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

The discriminant validity test attempts to find out how unique the measure is and whether it’s just a reflection of different factors [

54]. Multiple dimensions of a construct should show different parts of the same build. A few common ways are used to check for discriminant validity. A popular way to check for discriminant validity is with AVE, which stands for “average variance extracted.” This is what the Fornell-Larcker criterion says: There should be more connections between that construct and other constructs than the square root of the AVE for all of them.

Table 4 Fornell-Larcker criterion results confirm adequate discriminant validity among the constructs. Each construct’s square root of AVE is higher than its correlations with other constructs. For example, CSP has a square root of AVE of .849, which is greater than its correlations with EP (.754), GAC (.840), and GI (.680). Similarly, GOC shows low correlations with other constructs and a high AVE square root (.881), confirming it is distinct. Overall, the constructs exhibit good discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

Table 4.

Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

| |

CSP |

EP |

GAC |

GI |

GOC |

| CSP |

0.849 |

|

|

|

|

| EP |

0.754 |

0.926 |

|

|

|

| GAC |

0.840 |

0.614 |

0.819 |

|

|

| GI |

0.680 |

0.644 |

0.770 |

0.918 |

|

| GOC |

0.079 |

0.162 |

0.098 |

0.134 |

0.881” |

Table 5.

Path coefficient.

Table 5.

Path coefficient.

| |

Original sample (O) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T statistics (|O/STDEV|) |

P values |

Decision |

| EP -> CSP |

0.540 |

0.543 |

0.045 |

11.931 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| GAC -> EP |

0.291 |

0.295 |

0.070 |

4.171 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| GAC -> GI |

0.775 |

0.776 |

0.023 |

33.587 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| GI -> CSP |

0.332 |

0.331 |

0.055 |

6.019 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| GI -> EP |

0.421 |

0.416 |

0.081 |

5.198 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| GOC x GAC -> GI |

0.062 |

0.057 |

0.030 |

2.089 |

0.037 |

Supported”” |

Table 6.

Specific Indirect Effect.

Table 6.

Specific Indirect Effect.

| |

Original sample (O) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T statistics (|O/STDEV|) |

P values |

Decision |

| GAC -> EP -> CSP |

0.157 |

0.161 |

0.045 |

3.519 |

0.000 |

Supported |

| GAC -> GI -> CSP |

0.257 |

0.258 |

0.048 |

5.388 |

0.000 |

Supported” |

The path from EP to CSP shows a strong and statistically significant positive relationship (O = 0.540, t = 11.931, p < 0.001), suggesting that improvements in environmental performance contribute significantly to a firm’s sustainability outcomes. GAC is positively associated with both EP (O = .291, t = 4.171, p < 0.001) and GI (O = 0.775, t = 33.587, p < 0.001), indicating that effective environmental accounting practices and regulatory compliance significantly foster innovation and performance in environmental dimensions.

Further, GI shows a positive and significant influence on both CSP (O = 0.332, t = 6.019, p < 0.001) and EP (O = .421, t = 5.198, p < 0.001), highlighting its dual role in enhancing sustainability performance and environmental outcomes. All p-values are less than 0.001, confirming that the hypothesized relationships are statistically significant at a 1% significance level. These findings support the structural model and underline the critical mediating role of environmental and innovation-related practices in achieving corporate sustainability.

To examine mediation, indirect effects are tested using bootstrapping procedures. Results indicate that GI significantly mediates the relationship between GAC and CSP (β = 0.257, p < 0.000), as does EP (β = .157, p < 0.000), supporting H6 and H7. Both mediation effects are complementary, as the direct and indirect effects move in the same direction.

Finally, the moderation effect of GOC is analyzed to test H8. The interaction term GOC × GAC had a significant positive effect on GI (β = .062, p = .037), indicating that GOC strengthens the relationship between GAC and GI. Thus, H8 is also supported, demonstrating that a strong green organizational culture enhances the firm’s ability to convert absorptive capacity into innovation outcomes.

5. Discussion

The results confirm that GAC has a significant positive influence on both GI and EP, thereby validating H1 and H2. This supports earlier research by Qu et al. (2022) [

24] and Du & Wang (2022) [

25], who emphasized that the ability to acquire, assimilate, and apply external green knowledge enables firms to develop innovative and sustainable solutions. The strong path coefficient (0.775) between GAC and GI especially reinforces the view that green absorptive capabilities are essential in fostering innovation that aligns with environmental goals. Furthermore, GAC’s effect on EP (0.291) suggests that organizations with a higher capacity to absorb and use green knowledge are better equipped to implement practices that improve their environmental footprint, in line with the findings of Marrucci et al. (2022) [

26].

Additionally, GI significantly influences both EP and CSP, which supports H3 and H5, indicating the mediating role GI plays in the relationship between GAC and broader organizational outcomes. This echoes the work of Xie (2022) [

27] and Amores-Salvadó & Navas-López (2014) [

29], who identified that firms with stronger GI efforts tend to perform better socially and environmentally. The empirical evidence also aligns with [

32] assertion that companies adopting GI not only reduce environmental risk but also enhance their social responsibility profiles. The mediated effects—GAC → GI → CSP (0.257) and GAC → EP → CSP (0.157)—further validate H6 and H7, establishing GI and EP as crucial conduits through which GAC enhances social performance.

The direct and significant influence of EP on CSP (H4) affirms the theoretical propositions of [

30,

31] who emphasized that sound environmental practices improve transparency, governance, and stakeholder trust—hallmarks of strong social performance. The statistical support for this link (T = 11.931, p = 0.000) underscores the idea that environmentally responsible firms are perceived as socially responsible as well.

Finally, the moderating role of GOC between GAC and GI (H8) was statistically supported (p = 0.037), reinforcing earlier theoretical claims by Chen et al. (2012) [

50] and Leonidou et al. (2015) [

51]. A strong GOC amplifies the effectiveness of GAC by cultivating values, beliefs, and behaviours that prioritize sustainability. This cultural orientation helps translate green capabilities into actual innovation outcomes, validating that organizational culture is not just a backdrop but an active enabler of green transformation.

6. Practical Implications of the Study

The findings of this study provide meaningful insights for both corporate practitioners and policymakers. The evidence suggests that enhancing Green Absorptive Capacity and fostering Green Innovation significantly improve a firm’s Environmental and Corporate Sustainability Performance. Therefore, companies should invest in developing internal capabilities to acquire, assimilate, and apply environmental knowledge effectively. Human Resource and CSR departments should collaborate to design targeted training programs, environmental awareness campaigns, and sustainability-oriented team structures.

Additionally, fostering a supportive green organizational culture can act as a catalyst for innovation and performance improvement. Managers should prioritise embedding environmental values into the organisational ethos, encouraging cross-functional collaboration, and allocating resources to sustainable initiatives. Policymakers can support this transformation by providing incentives for sustainable innovation and creating regulatory environments that reward environmental performance. The integration of green strategies into core business operations not only improves firm performance but also strengthens stakeholder trust and long-term competitiveness.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several drawbacks despite its contributions. Firstly, the sample is restricted to 20 companies within India, operating in specific sectors such as textile manufacturing, industrial services, infrastructure construction, and farm equipment. The results can’t be used in other industries or countries because they only looked at a small part of the world and one industry at a time. Second, even if self-reported surveys are carefully made and sent out, they may still lead to response biases like common method variance or social desirability bias. Cross-sectional data collection makes it even harder to find causal links or look at how green innovation strategies affect a company’s long-term sustainability success.

Future research should consider adopting a longitudinal approach to better understand the temporal dynamics between GAC, GI, EP, and Corporate Sustainability. Expanding the sample to include companies from diverse geographical regions and industries will enhance the external validity of the results. Moreover, integrating qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews or case studies can offer richer contextual insights into organisational green practices and sustainability challenges. Future studies may also examine moderating variables such as regulatory frameworks, market competition, or technological readiness to better understand external influences on green innovation outcomes.

8. Conclusions

This study provides strong empirical evidence on the interconnectedness of GAC,GI, EP and CSP. It highlights the pivotal role of environmental capabilities in shaping organizational sustainability strategies. The results indicate that GAC significantly enhances both GI and EP, suggesting that firms that actively acquire, assimilate, and apply green knowledge are better positioned to drive innovation and achieve environmental improvements.

Furthermore, GI emerges as a key driver influencing both EP and CSP, demonstrating its dual contribution to innovation and overall performance. Organizations that integrate green processes and product innovations not only manage environmental concerns more effectively but also enhance their social responsibility profile. In the same vein, EP shows a direct and positive impact on CSP, reinforcing the idea that sustainable environmental practices contribute to improved stakeholder trust and corporate image.

The mediation analysis confirms that GI and EP serve as critical pathways linking GAC to CSP. These indirect effects emphasize that the development and application of green capabilities lead to broader organizational outcomes when coupled with innovation and performance improvements. The findings also underscore the importance of GOC as a moderator. A strong GOC strengthens the positive relationship between GAC and GI by embedding environmental values and behaviors into the organizational framework.

From a practical perspective, the study encourages firms, particularly in emerging economies, to prioritize the development of green capabilities, promote a culture of environmental innovation, and align their strategic goals with sustainability principles. Additionally, policymakers are urged to support these efforts through targeted initiatives and policy measures that foster green knowledge adoption, environmental innovation, and sustainability-driven performance at the industry level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, H.S.; visualization, supervision, validation and funding acquisition, S.C. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from governmental, private, or nonprofit funding organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since this study does not involve human or animal subjects, ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank my family, colleagues, and friends for their invaluable guidance and support throughout this research. Their insights and encouragement were instrumental in shaping this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Abbreviations

| GAC |

Green Absorptive Capacity |

| CSP |

Corporate Social Performance |

| EP |

Environmental Performance |

| GI |

Green Innovation |

| GOC |

Green Organizational Culture |

| GCC |

Green Core Competence |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| CSR |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

| CA |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

| CR |

Composite Reliability |

| AVE |

Average Variance Extracted |

References

- Chang, C.H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. Journal of business ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A. Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment. Academy of management Journal 1998, 41, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Valls, M.; Cespedes-Lorente, J.; Moreno-Garcia, J. Green practices and organizational design as sources of strategic flexibility and performance. Business Strategy and the Environment 2016, 25, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Management decision 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive environmental strategies: when does it pay to be green? California management review 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Rehman, S.U.; Giovando, G.; Alam, G.M. The role of environmental management accounting and environmental knowledge management practices influence on environmental performance: mediated-moderated model. Journal of Knowledge Management 2023, 27, 896–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J. Determinants of environmental innovation—New evidence from German panel data sources. Research policy 2008, 37, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, V.; Grandinetti, R. Knowledge strategies for environmental innovations: the case of Italian manufacturing firms. Journal of knowledge management 2013, 17, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainelli, G.; De Marchi, V.; Grandinetti, R. Does the development of environmental innovation require different resources? Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 94, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzucchi, A.; Montresor, S. Forms of knowledge and eco-innovation modes: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Ecological Economics 2017, 131, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Rodríguez, A.L.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal, A.G.; Ortega-Gutiérrez, J. Knowledge management, relational learning, and the effectiveness of innovation outcomes. The Service Industries Journal 2013, 33, 1294–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative science quarterly 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shujahat, M.; Sousa, M.J.; Hussain, S.; Nawaz, F.; Wang, M.; Umer, M. Translating the impact of knowledge management processes into knowledge-based innovation: The neglected and mediating role of knowledge-worker productivity. Journal of business research 2019, 94, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Sağsan, M. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. Journal of business ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Ur Rehman, S.; Zafar, A.U.; Ding, X.; Abbas, J. Impact of knowledge absorptive capacity on corporate sustainability with mediating role of CSR: Analysis from the Asian context. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2020, 63, 148–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ali, A. Enhancing team creative performance through social media and transactive memory system. International Journal of Information Management 2018, 39, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, E.D.; Blackhurst, J.; Pan, M.; Crum, M. Examining the role of stakeholder pressure and knowledge management on supply chain risk and demand responsiveness. The International Journal of Logistics Management 2014, 25, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Li, Y.H. Green innovation and performance: The view of organizational capability and social reciprocity. Journal of business ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. (2009). The core competence of the corporation. In Knowledge and strategy (pp. 41–59). Routledge.

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Long, Y.; Li, C. Research on the impact mechanism of heterogeneous environmental regulation on enterprise green technology innovation. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 322, 116127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Khan, A.; Yahya, S.; Zafar, A.U.; Shahzad, M. Green core competencies to prompt green absorptive capacity and bolster green innovation: the moderating role of organization’s green culture. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2022, 65, 536–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, H. Green innovation sustainability: how green market orientation and absorptive capacity matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrucci, L.; Iannone, F.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Antecedents of absorptive capacity in the development of circular economy business models of small and medium enterprises. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 31, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. The relationship between firms’ corporate social performance and green technology innovation: The moderating role of slack resources. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 949146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettlie, J.E.; Reza, E.M. Organizational integration and process innovation. Academy of management journal 1992, 35, 795–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores-Salvadó, J.; Martín-de Castro, G.; Navas-López, J.E. Green corporate image: Moderating the connection between environmental product innovation and firm performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 83, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, organizations and society 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Do environmental management systems improve business performance in an international setting? Journal of International Management 2008, 14, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, S.; Cohen, M.A. Does the market value environmental performance? Review of economics and statistics 2001, 83, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of marketing 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y. Does the natural-resource-based view of the firm apply in an emerging economy? A survey of foreign invested enterprises in China. Journal of management studies 2005, 42, 625–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, G.; Jin, J.; Li, J.; Paillé, P. Linking market orientation and environmental performance: The influence of environmental strategy, employee’s environmental involvement, and environmental product quality. Journal of Business Ethics 2015, 127, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ali, S.S. Exploring the relationship between leadership, operational practices, institutional pressures and environmental performance: A framework for green supply chain. International journal of production economics 2015, 160, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, F.L.; Semensato, B.I.; Prioste, D.B.; Winandy, E.J.L.; Bution, J.L.; Couto, M.H.G. . & Massaini, S.A. Innovation in the main Brazilian business sectors: characteristics, types and comparison of innovation. Journal of Knowledge Management 2018, 23, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Jolley, G.J.; Handfield, R. Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: complements for sustainability? Business strategy and the environment 2008, 17, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D. The effects of customer benefit and regulation on environmental product innovation.: Empirical evidence from appliance manufacturers in Germany. Ecological economics 2009, 68, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.H.; Chen, J.S.; Chen, P.C. Effects of green innovation on environmental and corporate performance: A stakeholder perspective. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4997–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, J.; Meissner, D.; Roud, V. Open innovation and company culture: Internal openness makes the difference. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2017, 119, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Rowley, C.; McLean, G.N.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.X. Top management support, green training and organization’s environmental performance: the electric power sector in Vietnam. Asia Pacific Business Review 2024, 30, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Moawad, N.F.; Saraih, U.N.; Abedelwahed, N.A.A.; Shah, N. Going green with the green market and green innovation: building the connection between green entrepreneurship and sustainable development. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 1484–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Tuna, M. Reinforcing competitive advantage through green organizational culture and green innovation. The service industries journal 2018, 38, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, S.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Hung, S.T.; Chang, C.W.; Huang, C.W. Improving green product development performance from green vision and organizational culture perspectives. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2020, 27, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Jan, F.A.; Ahmad, M.S. Green employee empowerment: a systematic literature review on state-of-art in green human resource management. Quality & Quantity 2016, 50, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage: The mediating role of green innovation. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2019, 30, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate environmentalism: Antecedents and influence of industry type. Journal of marketing 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, Y.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, C.W. Enhancing green absorptive capacity, green dynamic capacities and green service innovation to improve firm performance: An analysis of structural equation modeling (SEM). Sustainability 2015, 7, 15674–15692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Wu, F.S. Origins of green innovations: the differences between proactive and reactive green innovations. Management Decision 2012, 50, 368–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Christodoulides, P.; Spyropoulou, S.; Katsikeas, C.S. Environmentally friendly export business strategy: Its determinants and effects on competitive advantage and performance. International Business Review 2015, 24, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Da Silva, D.; Bido, D. Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Bido, D.; da Silva, D.; Ringle, C.(2014). Structural Equation Modeling with the Smartpls. Brazilian Journal Of Marketing 2015, 13. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.P.; Churchill Jr, G.A. Relationships among research design choices and psychometric properties of rating scales: A meta-analysis. Journal of marketing research 1986, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).