Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Previous Works

2. System Descriptions and Analysis

2.1. Mathematical Modelling of the Novel 4D Sprott-D System

Comparison of the Proposed 4D Hyperchaotic System with the Wei 2011 System [26].

- Incorporates an additional dimension with dynamic coupling;

- Introduces additional nonlinear and linear terms through w and εy;

- Exhibits hyperchaotic behavior due to increased degrees of freedom;

- Enables higher unpredictability and sensitivity to initial conditions.

2.2. Basic Properties of the Novel Sprott System

2.2.1. Symmetry

2.2.2. Dissipation and Existence of Attractor

2.2.3. Equilibrium Point Analysis

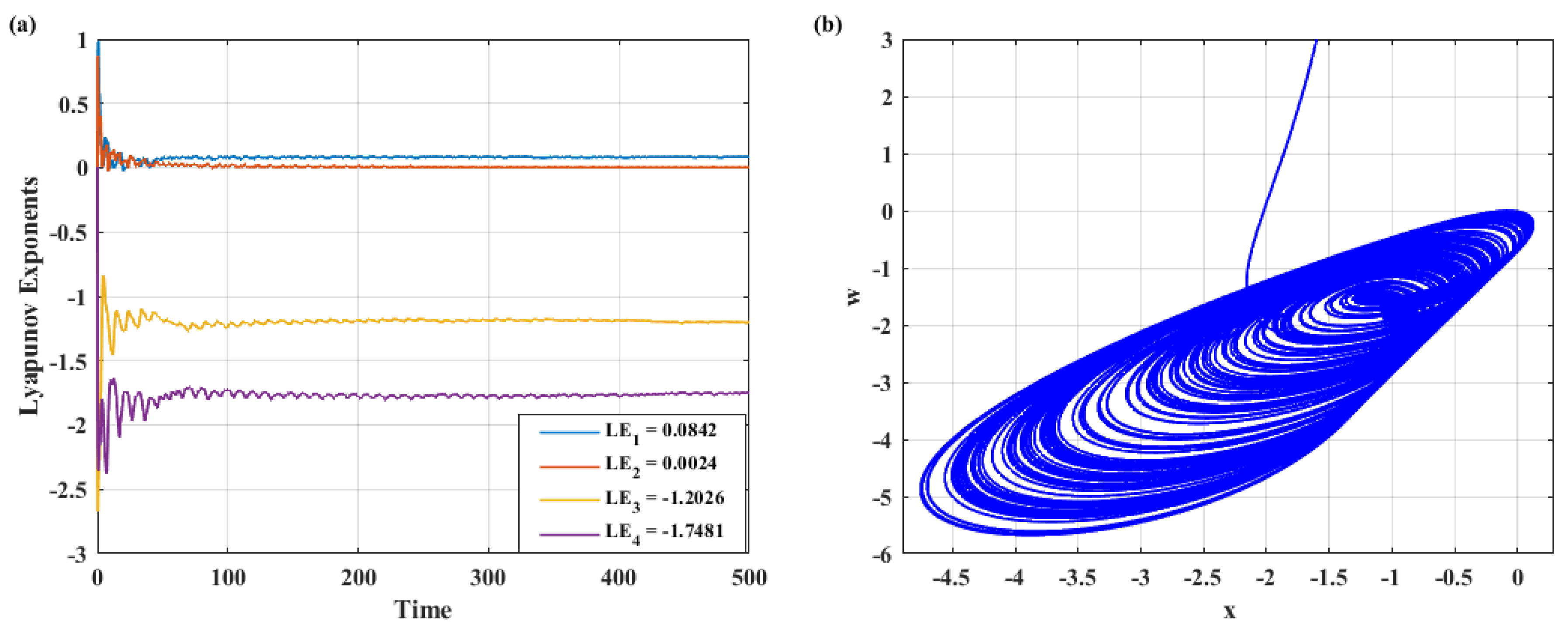

2.3. Lyapunov Exponents

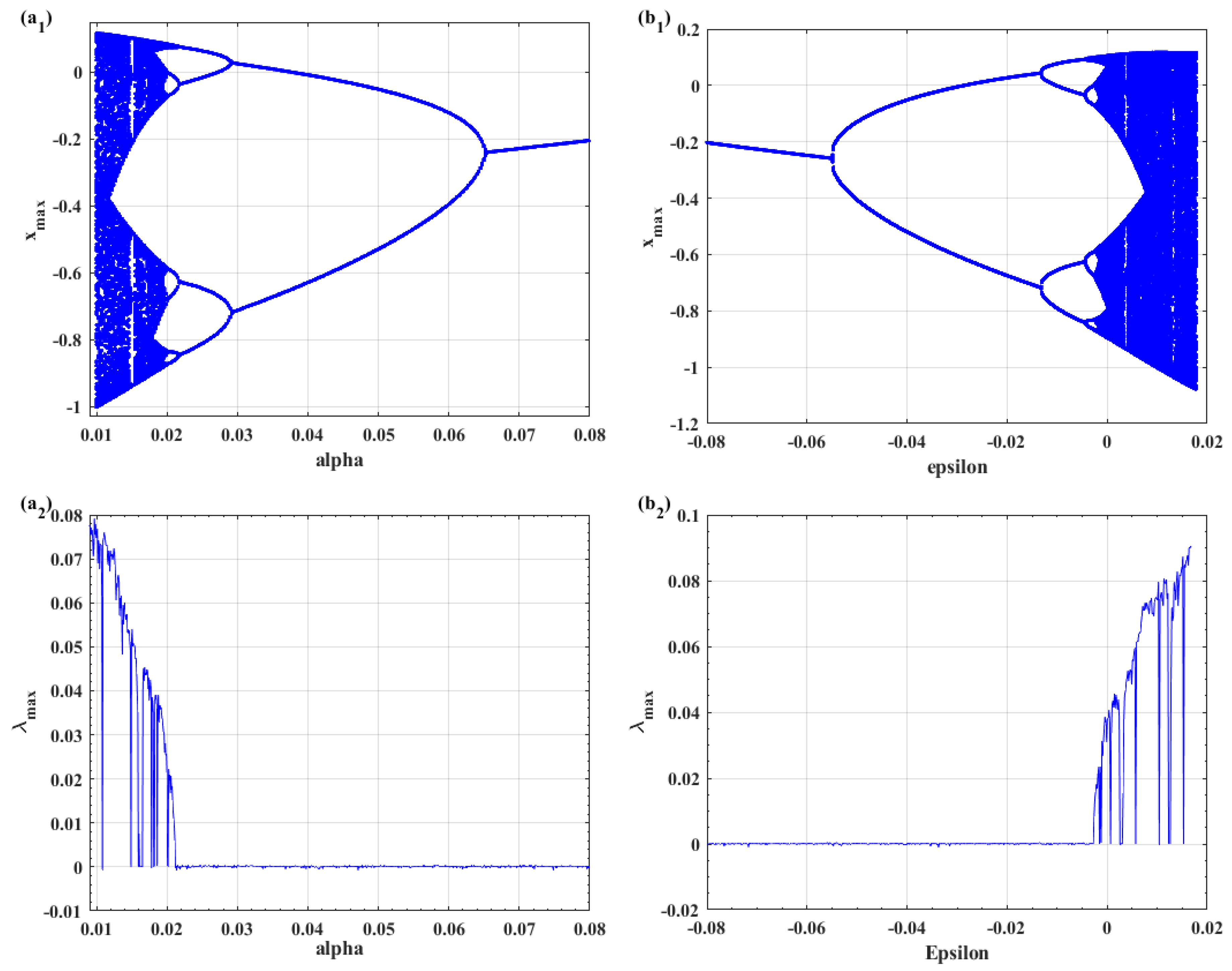

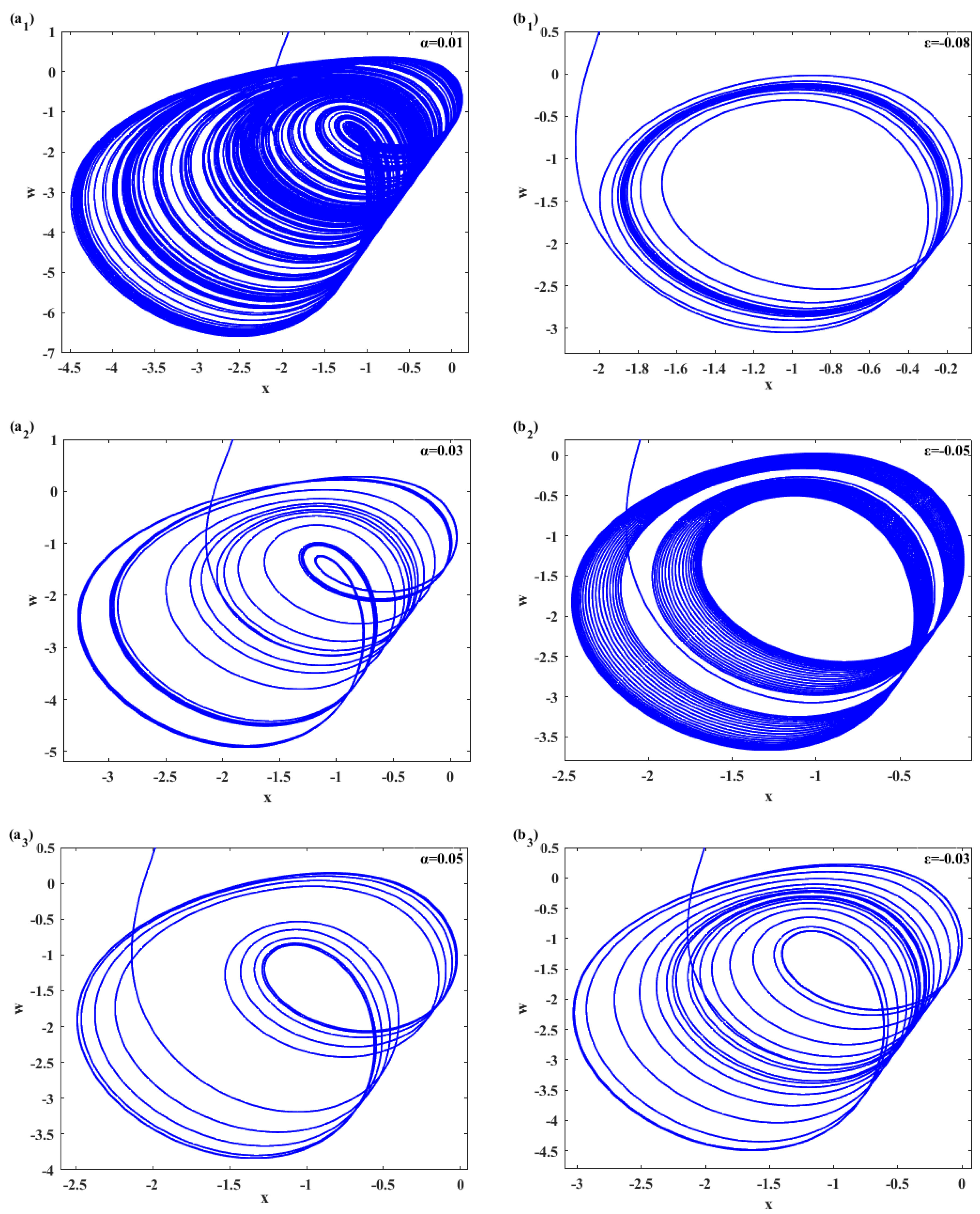

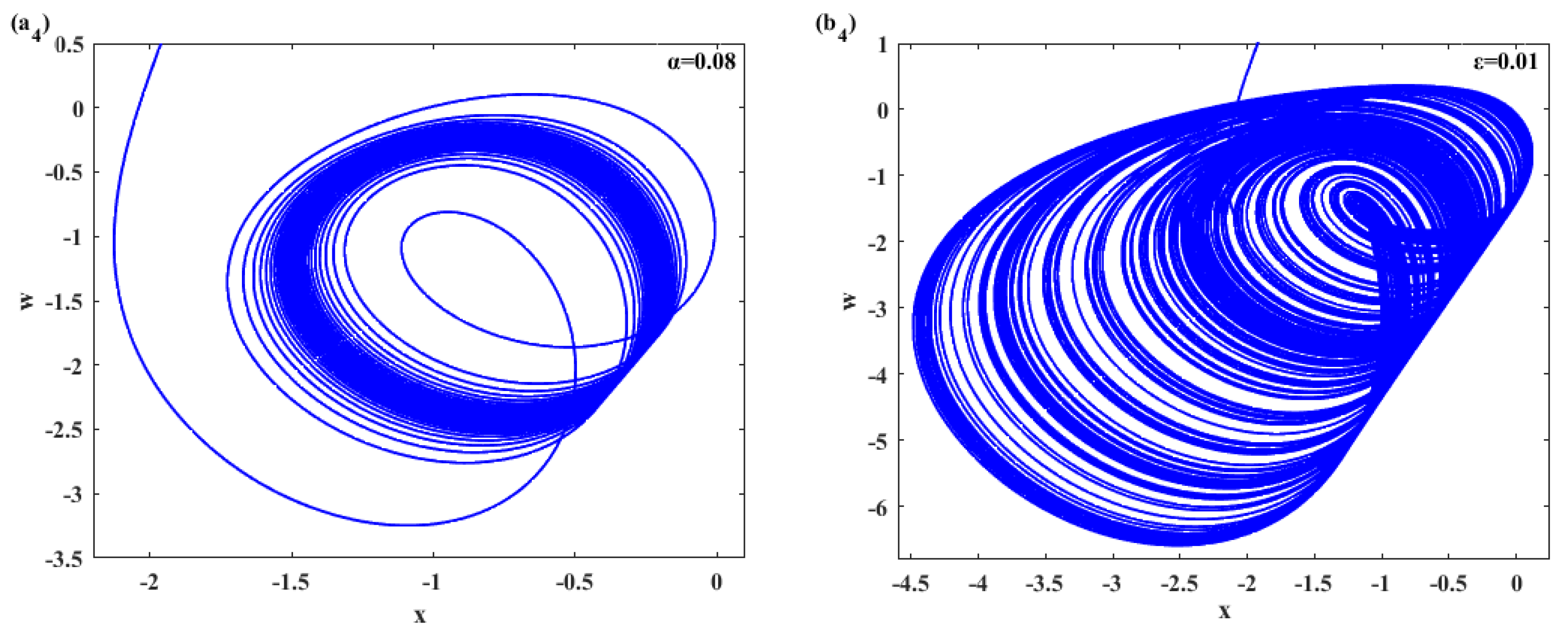

2.4. Transition to Chaos: Sensitivity of the System Towards α and ε

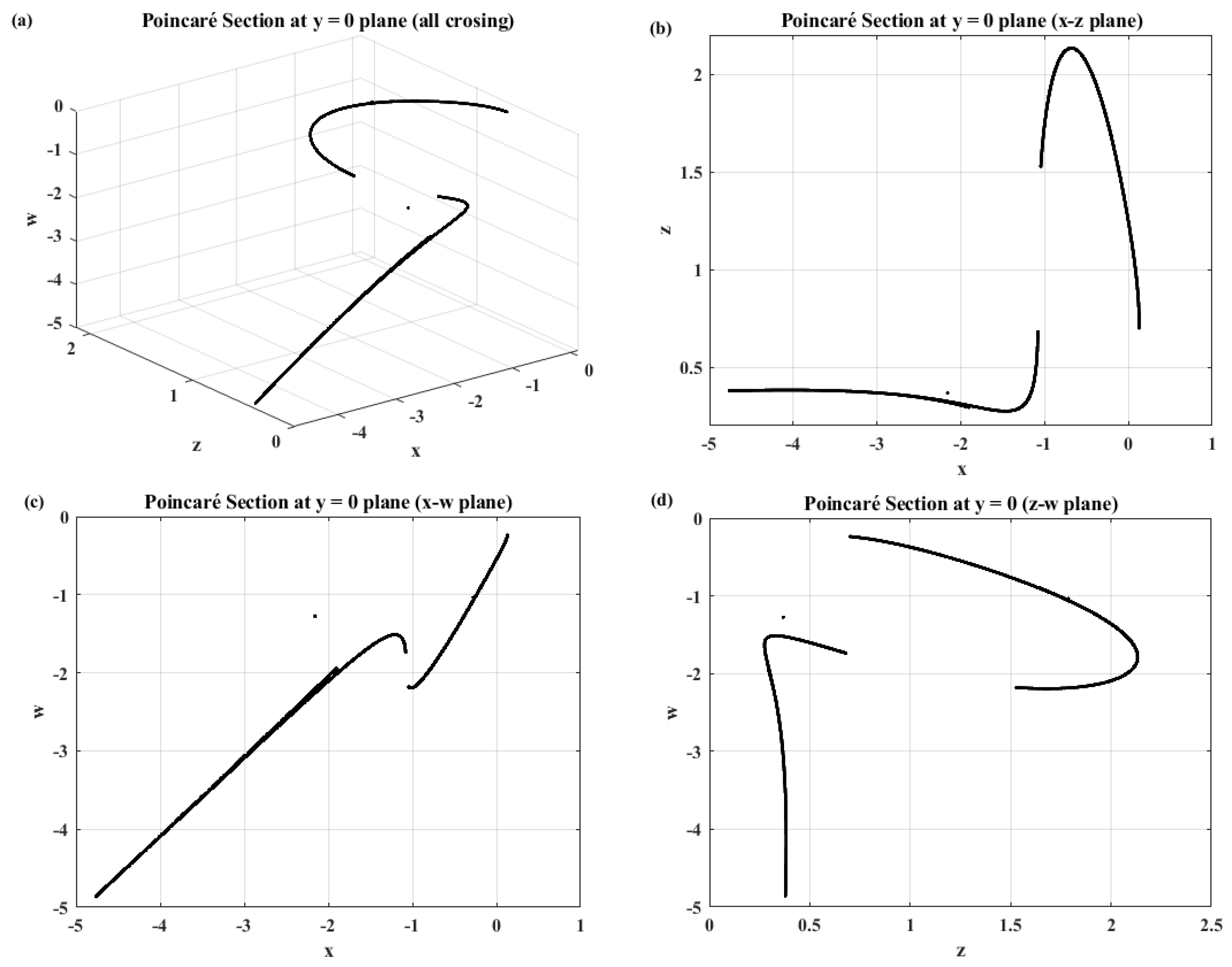

2.5. Poincaré Section of the New Sprott System

2.6. Pseudo Random Number Generation (PRNG) Algorithm

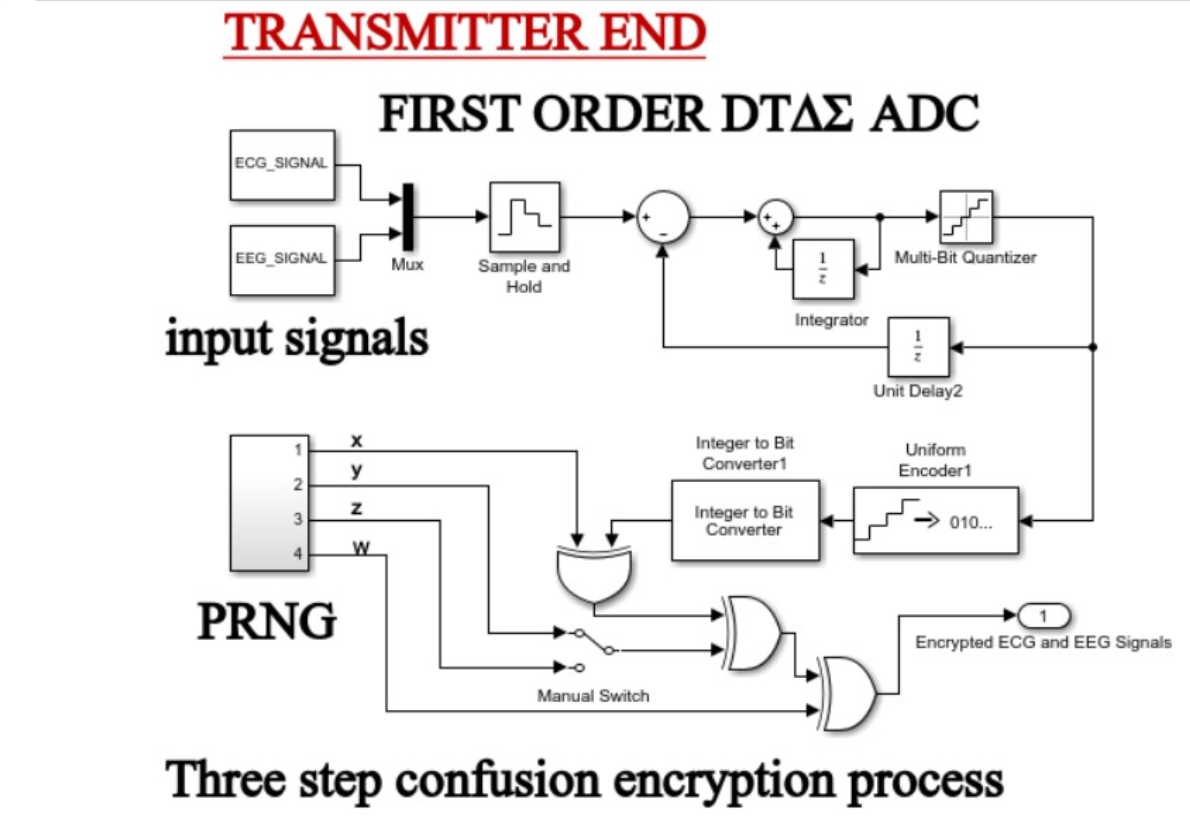

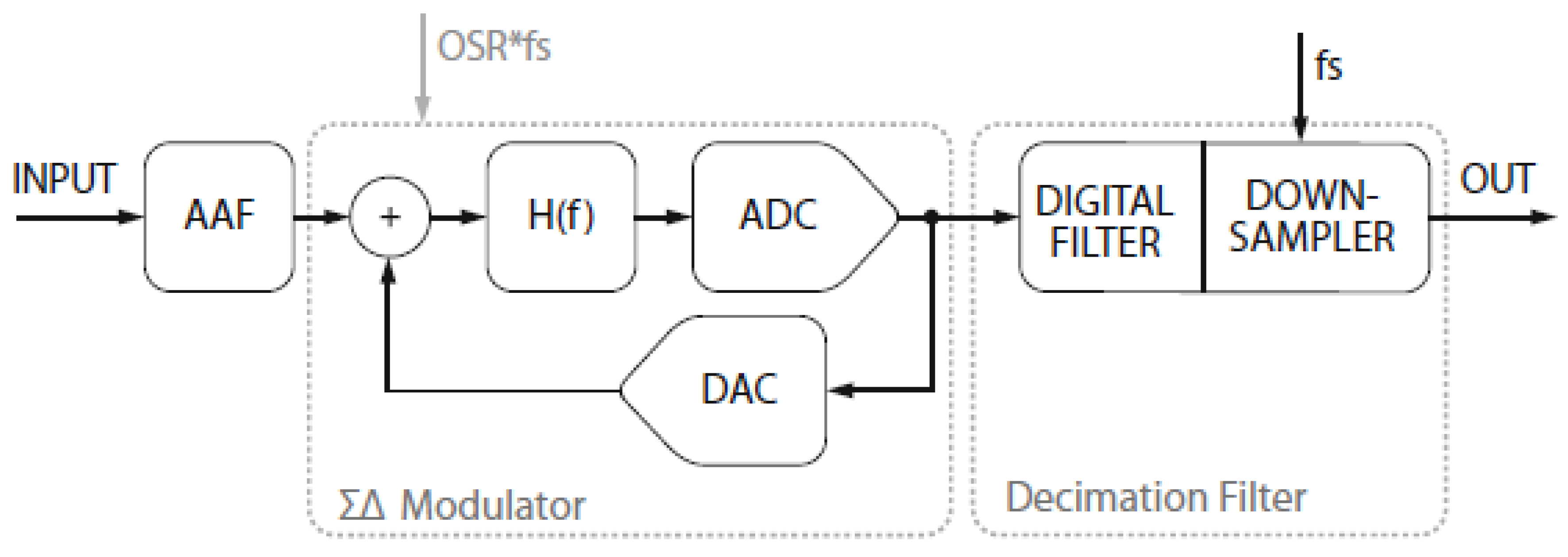

2.7. The First Order Discrete Time Delta Sigma Modulator (DTΔΣM)

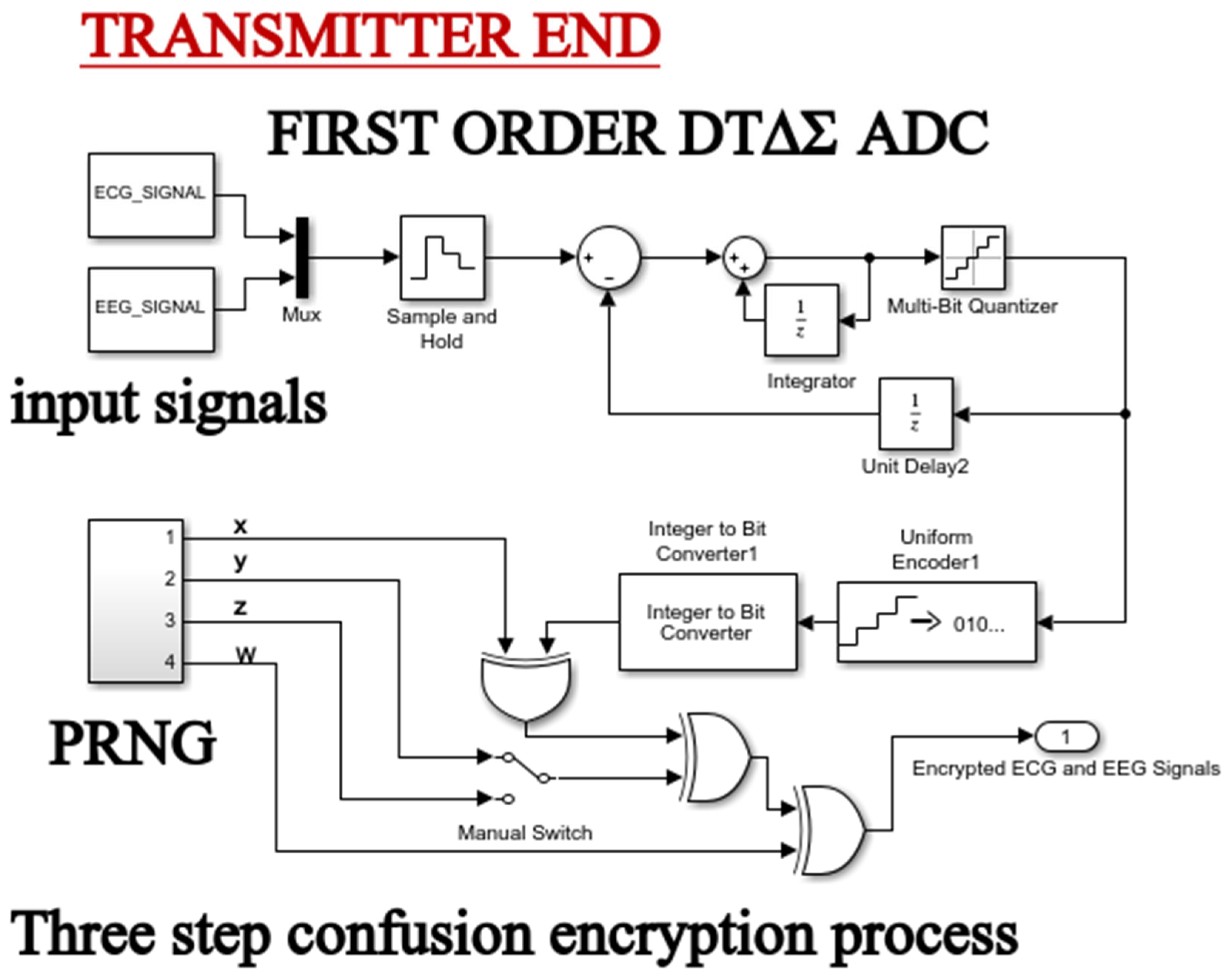

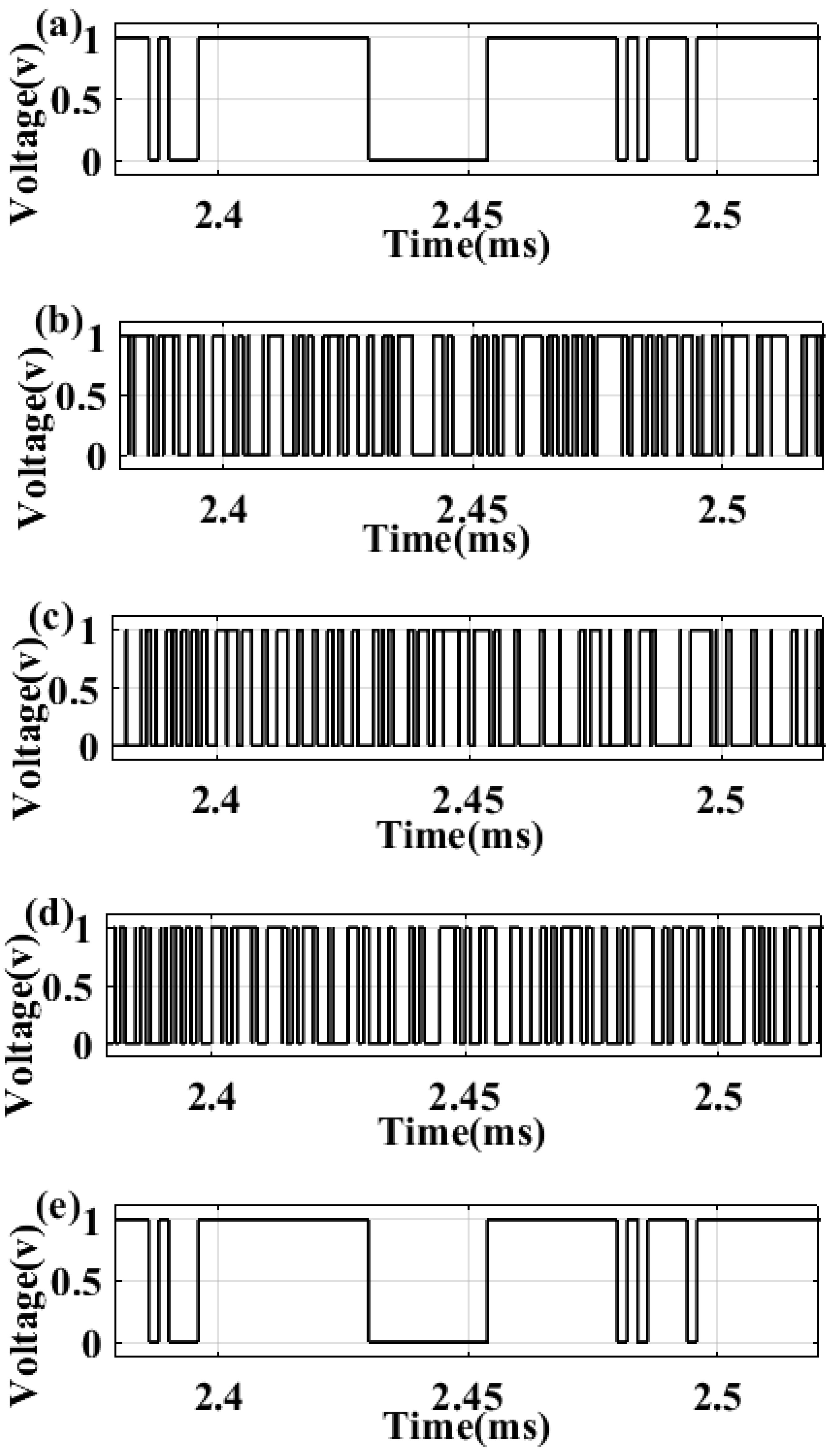

2.8. Chaos-Based Encryption Applied to the First-Order DTΔΣM System

- The encryption-decryption process

- Encryption process

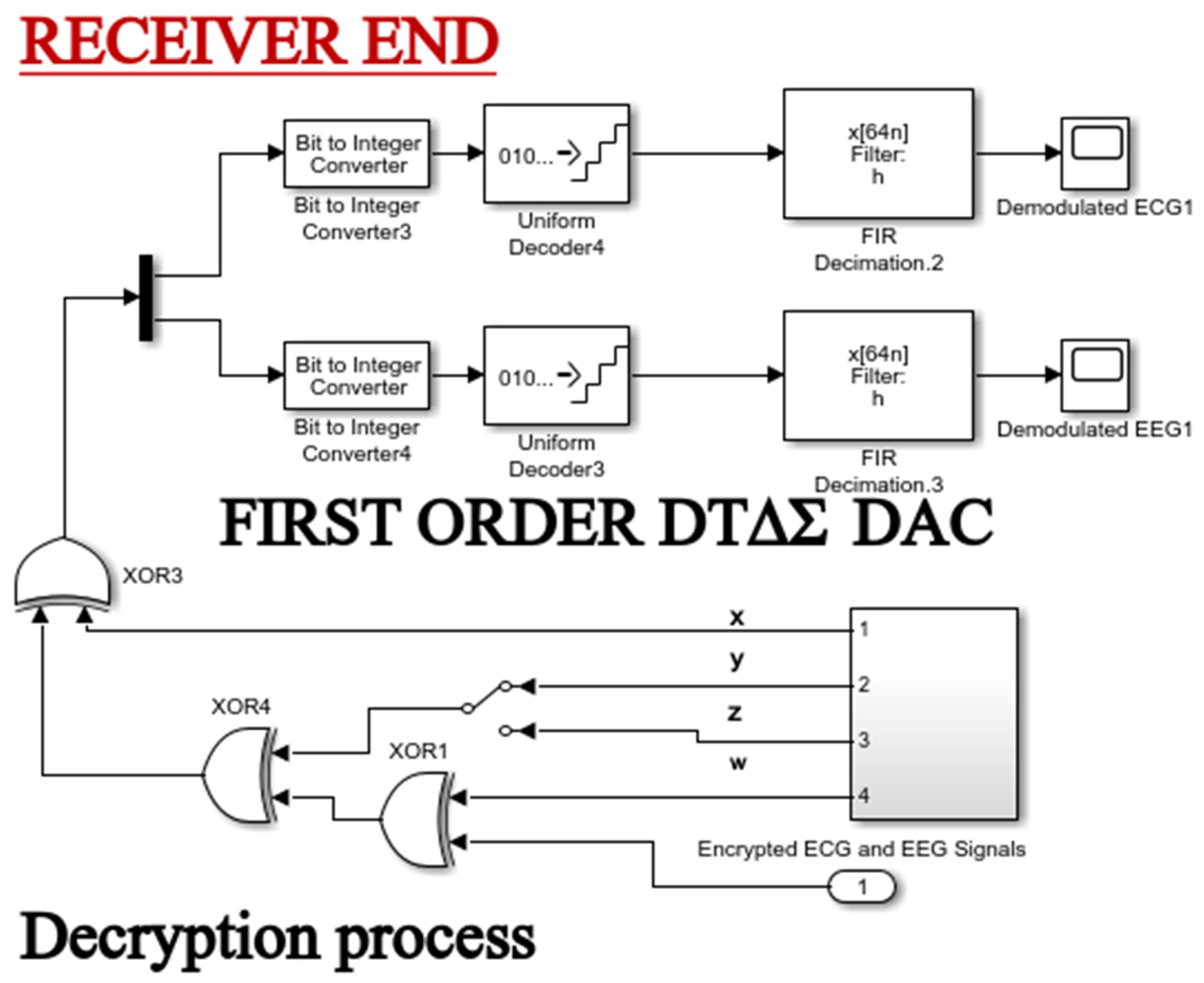

- b. Decryption process

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. NIST-800.22 Statistical Test Results

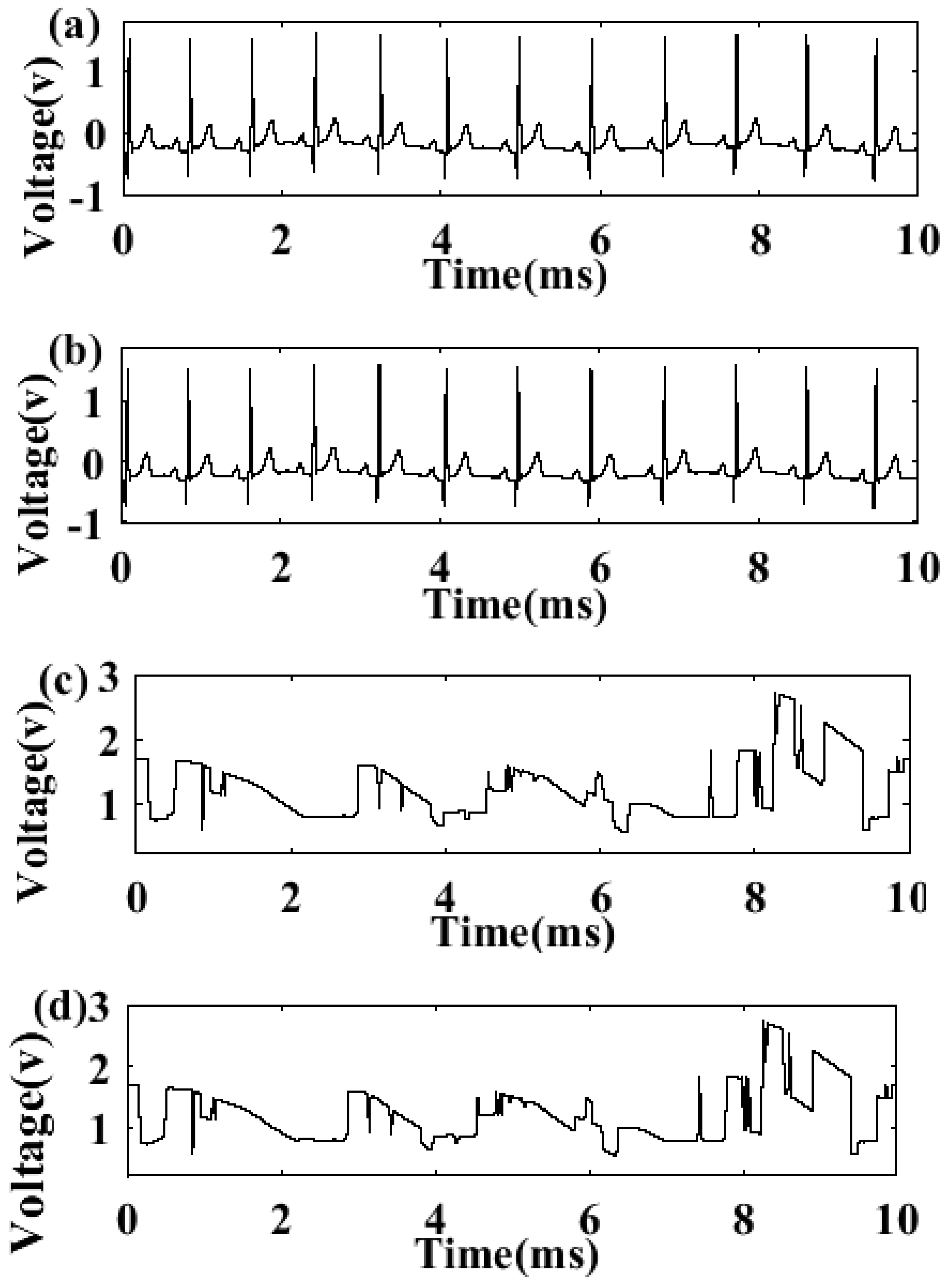

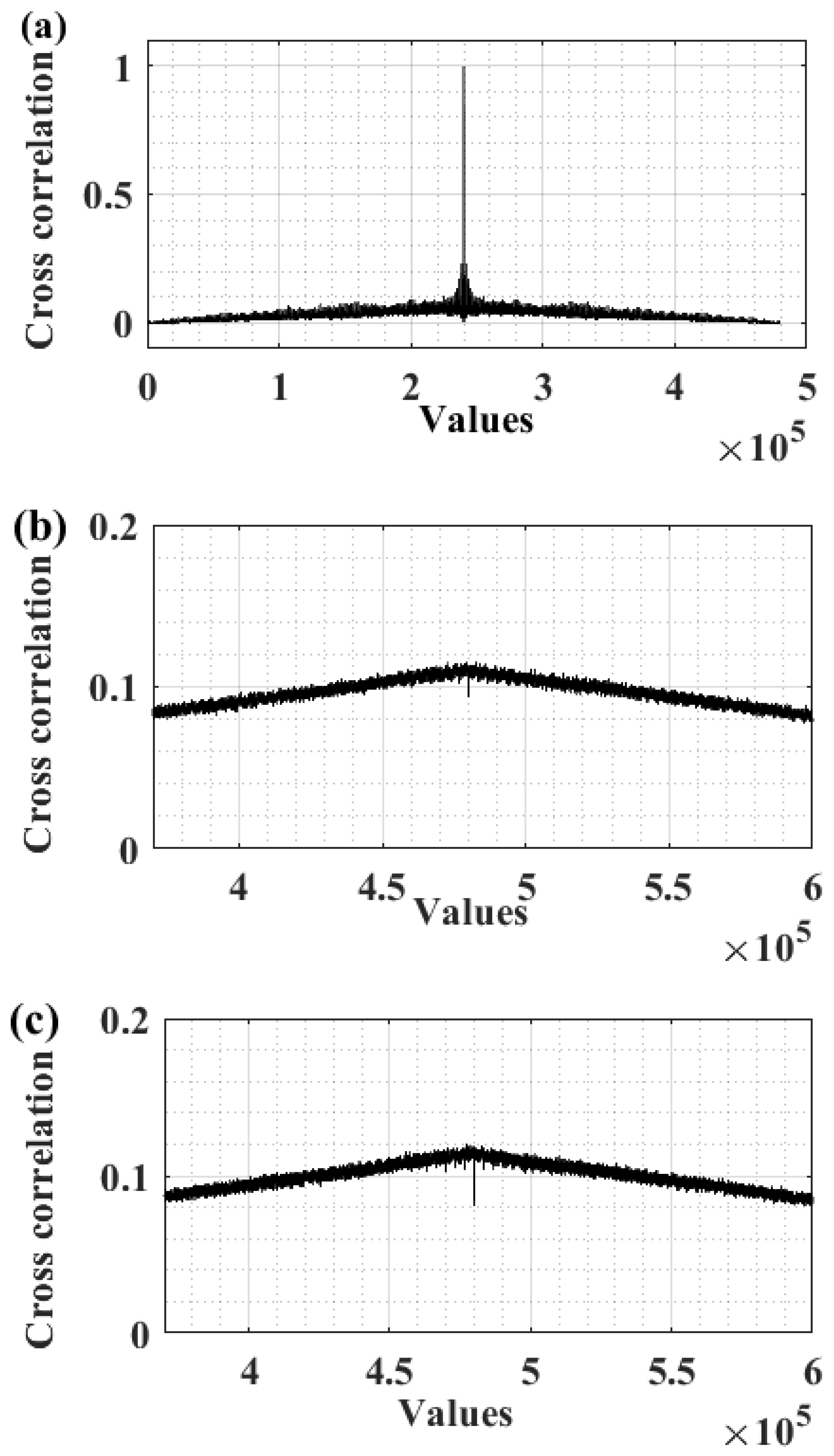

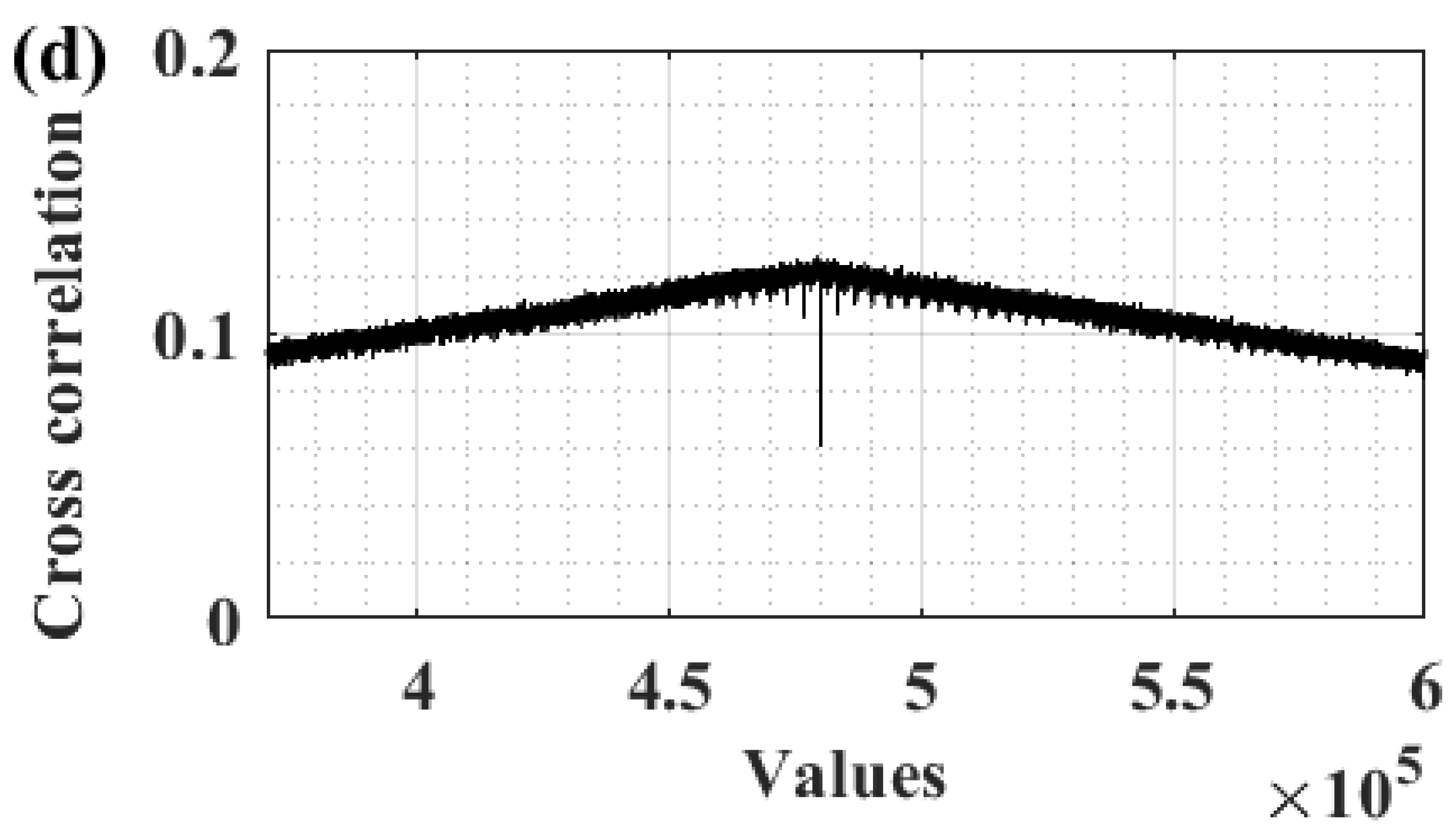

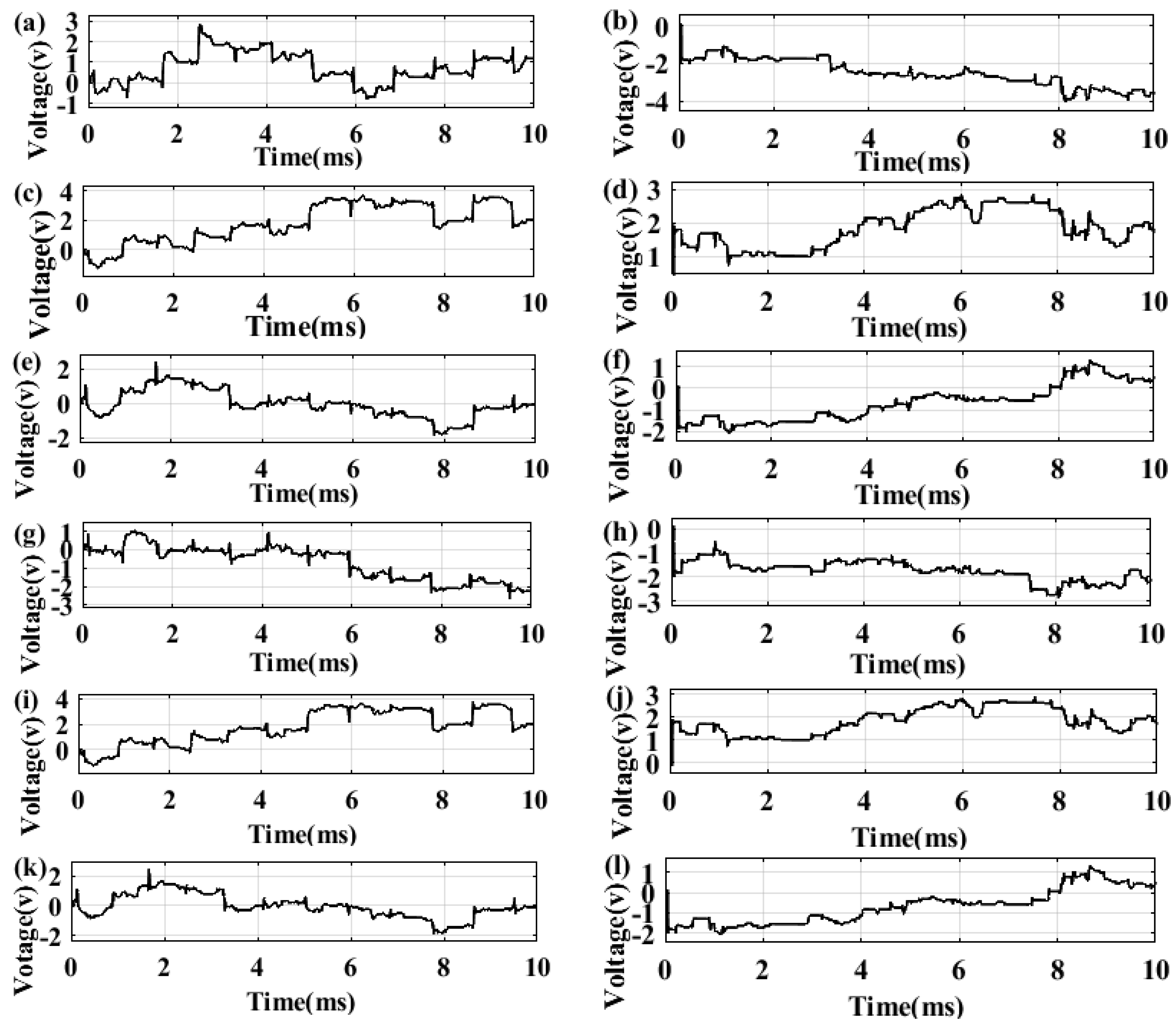

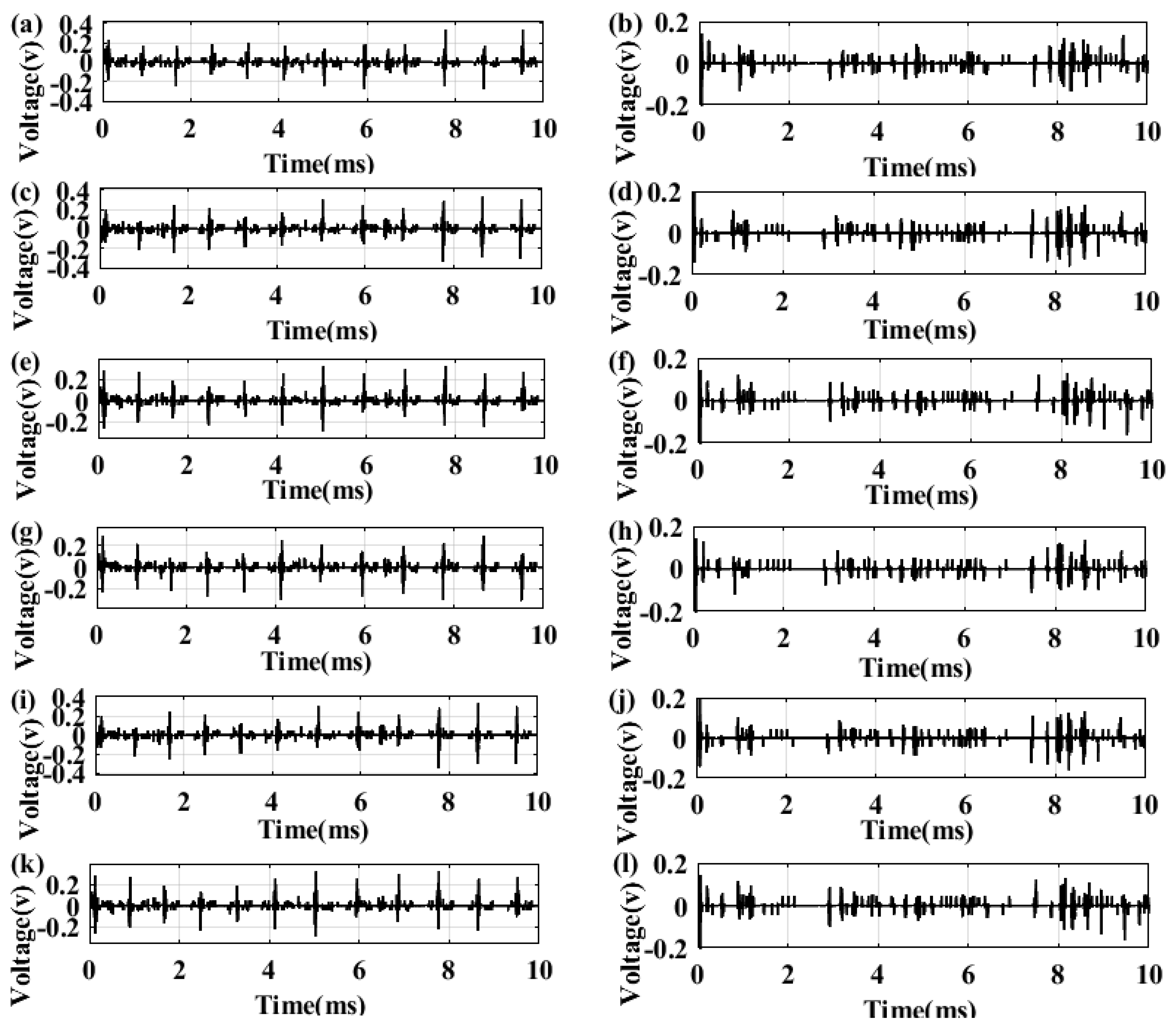

3.2. Results of the Secured First Order DTΔΣM Digital Communication Systems

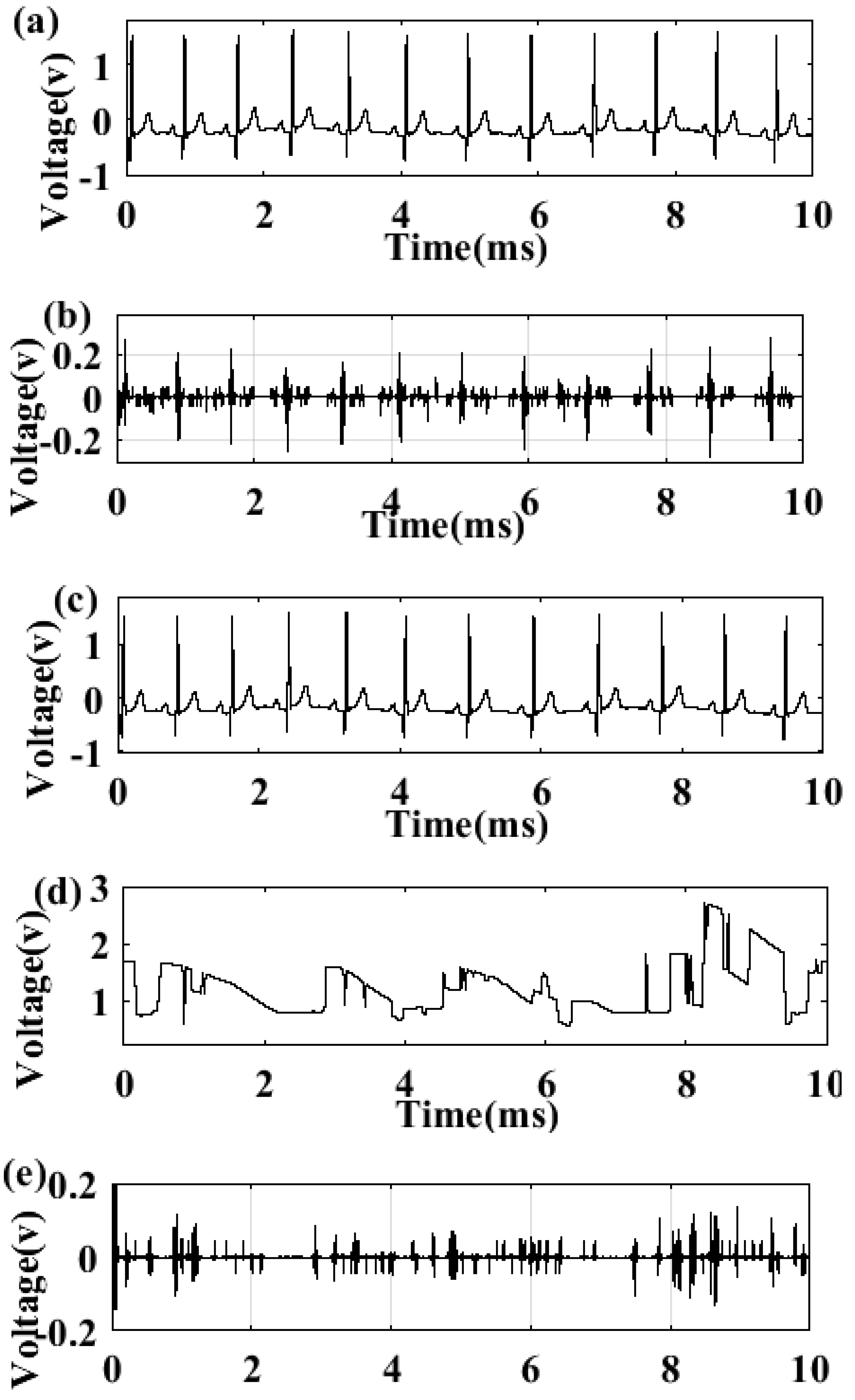

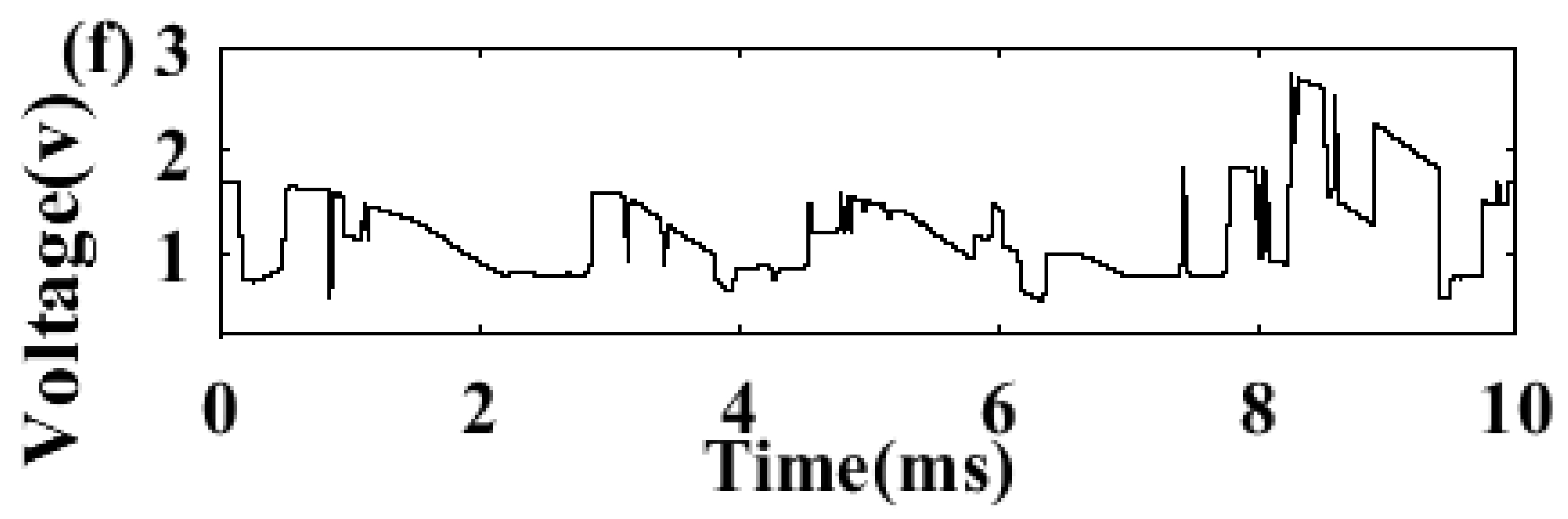

3.3. Results of the Encryption-Decryption Process

Key Analysis

- Key space

- b. Key sensitivity

4. Comparison with the Literature

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Consent to Publish declaration

Ethics and consent to participate declaration

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnaldi, I., Design of sigma-delta converters in Matlab/Simulink. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Shiu, H.-J., et al., Preserving privacy of online digital physiological signals using blind and reversible steganography. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine, 2017. 151: p. 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-K., et al., Personalized information encryption using ECG signals with chaotic functions. Information Sciences, 2012. 193: p. 125-140. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Xu, D., Li, Z., & Xu, Q, A general configuration for nonlinear circuit employing current-controlled nonlinearity: Application in Chua’s circuit. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, (2023). 177: p. 114233. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Cui, M., Yu, X., Shan, Y., & Xu, Q, Generating multi-folded hidden Chua’s attractors: Two-case study. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, (2023): p. 114242. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Xu, D., Iu, H. H. C., Wang, A., Chen, M., & Xu, Q., Dual Chua’s circuit. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers, (2023). 71(3): p. 1222-1231. [CrossRef]

- Nkandeu, Y.P.K. and A. Tiedeu, An image encryption algorithm based on substitution technique and chaos mixing. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2019. 78(8): p. 10013-10034. [CrossRef]

- Musanna, F., D. Dangwal, and S. Kumar, Novel image encryption algorithm using fractional chaos and cellular neural network. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 2022. 13(4): p. 2205-2226. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F., Shen, H., Yu, Q., Kong, X., Sharma, P. K., & Cai, S., Privacy protection of medical data based on multi-scroll memristive Hopfield neural network. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering, , (2022). 10(2): p. 845-858. [CrossRef]

- Nkandeu, Y.K., et al., Image encryption using the logistic map coupled to a self-synchronizing streaming. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2022. 81(12): p. 17131-17154. [CrossRef]

- Jeatsa Kitio, G., et al., Biomedical image encryption with a novel memristive chua oscillator embedded in a microcontroller. Brazilian Journal of Physics, 2023. 53(3): p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Ayemtsa Kuete, G.P., et al., Medical image cryptosystem using a new 3-D map implemented in a microcontroller. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2024: p. 1-40. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q., and Genwen Hu., "A Nonuniform Pixel Split Encryption Scheme Integrated With Compressive Sensing and Its Application in IoMT." IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2024. 20(9). [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q., Yijin Liu, and Luigi Fortuna., Dynamical analysis and fixed-time synchronization for secure communication of hidden multiscroll memristive chaotic system. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers, 2024. 71(10). [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q., Liang Yang, and Guanrong Chen., Two-dimensional discrete memristive oscillatory hyperchaotic maps with diverse dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2024. 72(1). [CrossRef]

- Kong, X., Yu, F., Yao, W., Cai, S., Zhang, J., & Lin, H., Memristor-induced hyperchaos, multiscroll and extreme multistability in fractional-order HNN: Image encryption and FPGA implementation. . Neural Networks, (2024). 171: p. 85-103. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F., Lin, Y., Yao, W., Cai, S., Lin, H., & Li, Y. , , 106904., Multiscroll hopfield neural network with extreme multistability and its application in video encryption for IIoT. Neural Networks, (2025). 182: p. 106904. [CrossRef]

- Mboupda Pone, J.R., et al., Passive–active integrators chaotic oscillator with anti-parallel diodes: Analysis and its chaos-based encryption application to protect electrocardiogram signals. Analog Integrated Circuits and Signal Processing, 2020. 103(1): p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Algarni, A.D., et al., Encryption of ECG signals for telemedicine applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2021. 80: p. 10679-10703. [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Escobar, M.Á., et al., Biosignal encryption algorithm based on Ushio chaotic map for e-health. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2023. 82(15): p. 23373-23399. [CrossRef]

- Wen, D., et al., The EEG signals encryption algorithm with K-sine-transform-based coupling chaotic system. Information Sciences, 2023. 622: p. 962-984. [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Escobar, D., Cruz-Hernández, C., López-Gutiérrez, R.M. and Murillo-Escobar, M.A., Chaotic encryption of real-time ECG signal in embedded system for secure telemedicine. Integration, 2023. 89: p. 261-270. [CrossRef]

- Banmene Lontsi, B.D., Gideon Pagnol Ayemtsa Kuete, and Justin Roger Mboupda Pone. , "On the Telemedicine Microcontroller-Based ECG Security Using a Novel 4Wings-4D Chaotic Oscillator (N4W4DCO).". IET Circuits, Devices & Systems, 2024. 1 (2024): p. 27 pages. [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C., Simple chaotic systems and circuits. American Journal of Physics, 2000. 68(8): p. 758-763.

- Chen, G. and X. Dong, From chaos to order: methodologies, perspectives and applications. Vol. 24. 1998: World Scientific.

- Wei, Z., Dynamical behaviors of a chaotic system with no equilibria. Physics Letters A, 2011. 376(2): p. 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. and T. Ueta, Chaos in circuits and systems. Vol. 11. 2002: World Scientific.

- Hilborn, R.C., Chaos and nonlinear dynamics: an introduction for scientists and engineers. 2000: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Kaplan, J.L. and J.A. Yorke, Chaotic behavior of multidimensional difference equations, in Functional Differential Equations and Approximation of Fixed Points: Proceedings, Bonn, July 1978. 2006, Springer. p. 204-227.

- Strogatz, S.H., Nonlinear dynamics and chaos with student solutions manual. (No Title), 2018. [CrossRef]

- Leonov, G., N. Kuznetsov, and V. Vagaitsev, Hidden attractor in smooth Chua systems. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 2012. 241(18): p. 1482-1486. [CrossRef]

- Azar, A.T. and S. Vaidyanathan, Advances in chaos theory and intelligent control. Vol. 337. 2016: Springer.

- Pham, V.-T., et al., From Wang–Chen system with only one stable equilibrium to a new chaotic system without equilibrium. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, 2017. 27(06): p. 1750097. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., A novel simple no-equilibrium chaotic system with complex hidden dynamics. International Journal of Dynamics and Control, 2018. 6: p. 1465-1476. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q., C. Wang, and L. Yang, Four-wing hidden attractors with one stable equilibrium point. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, 2020. 30(06): p. 2050086. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P. and B. Roy, Multistability and hidden chaotic attractors in a new simple 4-D chaotic system with chaotic 2-torus behaviour. International Journal of Dynamics and Control, 2018. 6: p. 529-538. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P. and B. Roy, Coexistence of asymmetric hidden chaotic attractors in a new simple 4-D chaotic system with curve of equilibria. Optik, 2017. 145: p. 209-217. [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzawi, M.A.A.-h.a.F.S., A 4D hyperchaotic Sprott S system with multistability and hidden attractors. Journal of Physics: ConferenceSeries, 2021. 1879(3): p. 032031. . [CrossRef]

- Gong, L., R. Wu, and N. Zhou, A new 4D chaotic system with coexisting hidden chaotic attractors. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, 2020. 30(10): p. 2050142. [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzawi, S.F. and M.A. Al-Hayali, Coexisting of self-excited and hidden attractors in a new 4D hyperchaotic Sprott-S system with a single equilibrium point. Archives of Control Sciences, 2022. 32. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. and J.C. Sprott, Coexisting hidden attractors in a 4-D simplified Lorenz system. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, 2014. 24(03): p. 1450034. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, S.C., E.O. Ochola, and Y. Sun, A hyperchaotic system without equilibrium. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2012. (69)1: p. 531–537. [CrossRef]

- S. Dadras, H.R.M., G. Qi, and Z.L. Wang, Four-wing hyperchaotic attractor generated from a new 4D system with one equilibrium and its fractional-order form. . Nonlinear Dynamics 2012. 67(2): p. 1161–1173. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, G.C., and Y. Li, Dynamic analysis and control of a new hyperchaotic finance system. . Nonlinear Dynamics, (2012). 67(3): p. 2171–2182. [CrossRef]

- P. Prakash, K.R., I. Koyuncu, J.P. Singh, M. Alcin, B.K. Roy, and M. Tuna, A novel simple 4-D hyperchaotic system with a saddlepoint Index-2 equilibrium point and multistability: Design and FPGA-based applications. Circuits, Systems, and Signal Processing, (2020). 39(9): p. 4259–4280. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F., et al., Dynamic analysis and FPGA implementation of a new, simple 5D memristive hyperchaotic Sprott-C system. Mathematics, 2023. 11(3): p. 701. [CrossRef]

- Rossler, O., An equation for hyperchaos. Physics Letters A, 1979. 71(2-3): p. 155-157. [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C., Chaos and time-series analysis. 2003: Oxford university press.

- Awrejcewicz, J., Bifurcation and chaos: theory and applications. 2012: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Wolf, A., et al., Determining Lyapunov exponents from a time series. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 1985. 16(3): p. 285-317. [CrossRef]

- Ott, E., Grebogi, C., & Yorke, J.A., Controlling chaos. Physical Review Letters, 1990. 64(11): p. 1196. [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C., A new class of chaotic circuit. Physics Letters A, 2000. 266: p. 19–23. [CrossRef]

- Kocarev, L.P., U.,, General approach for chaotic synchronization with applications to communication. Phys. Rev. Lett., 1995. 74(25): p. 5028. [CrossRef]

- Alligood, K.T., T.D. Sauer, and J.A. Yorke, One-dimensional maps. Chaos: An Introduction to Dynamical Systems, 1996: p. 1-42.

- Kaya Turgay, A true random number generator based on a Chua and RO-PUF: design, implementation and statistical analysis. Analog Integrated Circuits and Signal Processing, 2019. 102(2): p. 415-426. [CrossRef]

- Candy, J.C. and G.C. Temes, Oversampling delta-sigma data converters: theory, design, and simulation. 1991: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kester, w., Data conversion handbook. 2005: Newnes.

- Pohlmann, K.C., Principles of digital audio. 2000: McGraw-Hill Professional.

- Oppenheim, A.V., Discrete-time signal processing. 1999: Pearson Education India.

- Schreier, R., and Gabor C. Temes. , Understanding delta-sigma data converters. . Piscataway, NJ: IEEE press,, 2005. Vol. 74.

- Kligfield, P., Gettes, L.S., Bailey, J.J., Childers, R., Deal, B.J., Hancock, E.W., Van Herpen, G., Kors, J.A., Macfarlane, P., Mirvis, D.M. and Pahlm, O.,, Recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part I: the electrocardiogram and its technology: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology. the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation,, 2007. 115(10): p. pp.1306-1324. [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.W., Hancock, E.W. and Gettes, L.S., , Recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part II: Electrocardiography diagnostic statement list: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology. the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation, 2007. 115(10): p. pp.1325-1332. [CrossRef]

- Rijnbeek, P.R., Jan A. Kors, and Maarten Witsenburg., "Minimum bandwidth requirements for recording of pediatric electrocardiograms.". Circulation 2001. 104.25(2001): p. 3087-3090. [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, M.E., Rijnbeek, P.R., Niemeijer, M.N., Hofman, A., Van Herpen, G., Bots, M.L., Hillege, H., Swenne, C.A., Eijgelsheim, M., Stricker, B.H. and Kors, J.A.,. ,, Normal values of corrected heart-rate variability in 10-second electrocardiograms for all ages. Frontiers in physiology, 2018. 9: p. p.424. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.B.S.P., Biomedical Signal Processing. Vol. 2. 2019: Compression and Automatic Recognition.

- Pal, S., and Madhuchhanda Mitra. , "Increasing the accuracy of ECG based biometric analysis by data modelling." in Measurement 2012. p. 1927-1932.

- Gotman, J., Automatic recognition of epileptic seizures in the EEG. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology, 1982. 54.5 (1982): p. 530-540. [CrossRef]

- Nuwer, M.R., Comi, G., Emerson, R., Fuglsang-Frederiksen, A., Guérit, J.M., Hinrichs, H., Ikeda, A., Luccas, F.J.C. and Rappelsburger, P., , IFCN standards for digital recording of clinical EEG. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology, 1998. 106(3): p. 259-261. [CrossRef]

- Borges, V.S., Nepomuceno, E.G., Duque, C.A. and Butusov, D.N., Some remarks about entropy of digital filtered signals. Entropy, 2020. . 22(3): p. p.365. [CrossRef]

| No |

Behavior of System |

No. of Positive LEs |

Nature of Equilibria |

Attractor Behavior |

No of Terms |

No. of Nonlinear Terms |

Reference |

| 1 | Chaotic | 1 | no equilibria | hidden | 9 | 2 | 2017 [33] |

| 2 | Chaotic | 1 | no equilibria | hidden | 8 | 1 | 2018 [34] |

| 3 | Chaotic | 1 | Stable | hidden | 10 | 3 | 2020 [35] |

| 4 | Chaotic | 1 | no equilibria | hidden | 8 | 1 | 2017 [36] |

| 5 | Chaotic | 1 | curve of points | hidden | 8 | 1 | 2017 [37] |

| 6 | Chaotic | 1 | no equilibria | hidden | 8 | 2 | 2021 [38] |

| 7 | Chaotic | 1 | infinite equilibria | hidden | 7 | 2 | 2020 [39] |

| 8 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | stable/unstable | self-excited | 9 | 2 | 2022 [40] |

| 9 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | no equilibria | hidden | 7 | 2 | 2014 [41] |

| 10 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | no equilibria | hidden | 7 | 5 | 2012 [42] |

| 11 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | unstable point | Self-excited | 9 | 4 | 2012 [43] |

| 12 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | three equilibria | Self-excited | 11 | 3 | 2012 [44] |

| 13 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | unstable point | Self-excited | 9 | 2 | 2020 [45] |

| 14 | Hyperchaotic | 2 | no equilibria | hiddden | 11 | 2 | this work |

| Tests type | P value | Result |

| Frequency (monobit) test | 0.578210854772423 | Success |

| Frequency test within a block | 0.111423028947461 | Success |

| Runs test | 0.632430089580616 | Success |

| Test for the longest run of ones in a block | 0.908448608148175 | Success |

| Binary Matrix Rank Test | 0.968582507884855 | Success |

| Discrete Fourier Transform | 0.274824796911087 | Success |

| Non overlapping Template Matching Test | 0.507703387782452 | Success |

| Overlapping Template Matching Test | 0.25669821913924 | Success |

| Maurer's "Universal Statistical" Test | 0.487893879474829 | Success |

| Linear Complexity Test | 0.558529628886096 | Success |

| The Serial Test | 0.8436652966348 | Success |

| Approximate Entropy Test | 0.510914962117407 | Success |

| Cumulative Sums Test | 0.207047692439126 | Success |

| Random Excursions Test | 0.783496150475357 | Success |

| Random Excursions Variant Test | 0.907743035768127 | Success |

|

Proposed Scheme |

Ref. 2020 [13] |

Ref. 2021 [15] |

Ref. 2022 [18] |

Ref. 2023 [19] |

Ref. 2024 [20] |

|

| Acquisition method | ||||||

|

Real-time signal acquisition |

-- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ | ✓ |

| Data Base | Ref. [20] | MIT-BIH | -- | MIT-BIH | -- | AD8232 ECG sensor |

| Chaotic map | ||||||

| Name | New 4D Sprott-D system | AES | 2-D chaotic Baker map | 3-DES | Badola map | Novel 4Wings-4D Chaotic Oscillator (N4W4DCO) |

| Dimension | 4D | 3D | 2D | - | 2D | 4D |

| Microcontroller implementation | ✓ | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ |

| Security analysis | ||||||

|

Encryption key space analysis |

✓ | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ |

|

Encryption key sensitivity |

✓ | -- | -- | -- | ✓ | ✓ |

| Histogram | -- | -- | ✓ | -- | -- | ✓ |

| Correlation | ✓ | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ |

| Noise robustness | -- | ✓ | -- | --- | -- | - |

| NIST 800-22 | ✓ | ✓ | -- | -- | ✓ | ✓ |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Embedded system | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ | ✓ |

| Simulation | ||||||

| MATLAB Simulink | ✓ | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ |

| Transmission mode | ||||||

| Encoding-decoding | ✓ | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).