1. Introduction

Bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) is a highly infectious disease causing significant economic losses in the cattle industry globally [

1] Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV), the cause of BVD, is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus in the genus Pestivirus of the Flaviviridae family[

2]. The Pestivirus genus also includes the classical swine fever virus and the border disease virus [

2,

3]. Cattle of all breeds and ages are the natural hosts of BVDV, but other animals like goats, sheep, camels, pigs, and giraffes can also be infected. Infected animals show persistent diarrhea, blood or mucus in feces, mucosal ulceration, reproductive disorders, and elevated body temperature [

4]. Pregnant females infected with BVDV may experience abortion, fetal death, or give birth to persistently infected (PI) animals, which remain infected for life and continuously shed the virus, posing a significant transmission risk [

5].

Induced immunosuppression increases the risk of other diseases [

6]

. BVD reduces livestock breeding and growth efficiency, increases young animal mortality, and increases the prevalence of reproductive, respiratory, and gastrointestinal diseases[

7]

.

Bangladesh, one of the most densely populated countries in the world, is home to nearly 24 million cattle, resulting in 145 ruminants per square kilometer. The cattle industry supports approximately 15% of the country’s workforce and contributes about 3% to the agricultural GDP [

8]. Despite the known presence of BVDV in neighboring India and its potential economic impact on such a large cattle population, there has been limited research on the prevalence of BVDV in Bangladesh [

9,

10]. The reported prevalence of BVD in Bangladesh was 51.1% in both studies [

9,

10].

Bovine Viral Diarrhea is characterized by its stealthy nature, leading to prolonged transient infections and the presence of persistently infected (PI) animals, which serve as efficient reservoirs. These factors have contributed to its widespread distribution among cattle populations worldwide [

11] (Moenning and Becher, 2018). In Bangladesh, earlier research was limited to 94 serum samples collected from two districts: Chattogram and Barishal [

9,

10]. This study aims to estimate the prevalence of BVD in dairy cattle and identify the risk factors associated with the disease, covering large geographic regions and using an appropriate sample size for the first time in Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Study Population and Target Population

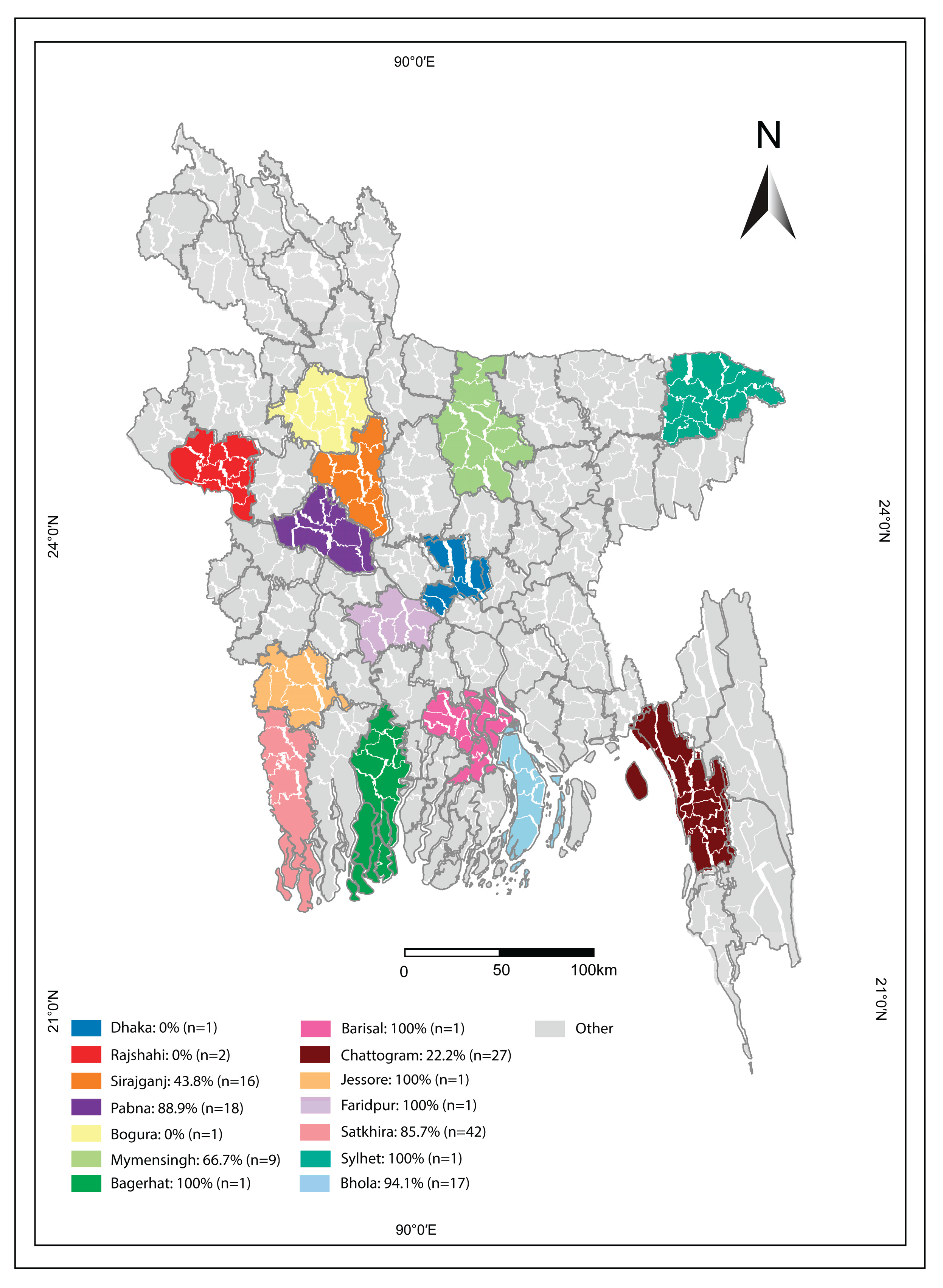

A cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2023 to December 2024, focusing on the dairy herds of Bangladesh. The study population included dairy herds from selected districts, with samples collected from 14 districts (

Figure 1). Vaccination against BVD is not currently practiced in Bangladesh. The samples were sourced from non-experimental or lab animals and were handled by registered and well-trained veterinary professionals.

2.2. Sampling Size Calculation and Sampling Protocol

The sample size for this study was determined using equation 1.

In this equation, Z is the Z-score for a 95% confidence level, which is 1.96. P represents the expected prevalence, set at 51.1% or 0.511 [

10], and d is the precision, determined to be 4% or 0.04. Based on these assumptions, the calculated sample size was 600. However, 767 samples were ultimately selected for this study. Initially, bulk milk samples from 138 conveniently sampled farms were chosen. Then, eight herds were randomly selected from the total BVD positive herds until the target sample size of 767 was reached.

2.3. Collection of Milk Samples

Approximately 40 milliliters of composite (bulk) milk from a herd were collected aseptically in a sterile Falcon tube. The same amount of fresh milk was also collected aseptically from each cow in the herd into separate sterile Falcon tubes. Each FalconThe collected milk was labeled “NS,” immediately frozen, and transported to the Department of Medicine at Bangladesh Agricultural University in an icebox. The samples were stored at -20°C until further analysis. Additionally, blood samples were collected from cattle in the dry period, approximately 5 ml in a 6 ml syringe. The syringes were immediately tilted at a 45° angle and placed in the refrigerator at 4-8°C for half an hour. After the serum separated, it was transferred to a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube, stored at -20°C, and then transported to the laboratory in an icebox, maintaining -20°C until analysis.

2.4. Herd and Cow-Level Data Collection

Herd and cow-level data on potential risk factors were collected using pretested questionnaires. Herd-level data included herd size, the number of lactating cows, heifers, and calves on the farm, the number of abortions, retention of fetal membranes, repeat breeding cases per year, daily milk yield, and the semen source for breeding purposes. Cow-level data included age, breed, physical condition, pregnancy status, history of abortion, retained fetal membrane, reproductive disorders, number of calves, lactation stage, and daily average milk yield.

2.5. Processing of Milk Samples

The milk samples were thawed at room temperature and allowed to sit until the cream separated from the lactoserum, with the cream floating on top and the lactoserum at the bottom. The lactoserum was then transferred into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes and placed in a 96-well plate (non-ELISA plate). Wells A1 and B1 contained positive controls, while C1 and D1 contained negative controls. The remaining 92 wells were filled with lactoserum to facilitate the rapid transfer of both controls and samples to the ELISA plate using a 12-channel micropipette.

2.6. Competitive Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (cELISA)

The collected milk samples were analyzed using ID.vet BVD competitive ELISA kits. The test was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, reagents were brought to room temperature (21°C ± 5°C) before use. Inversion or vortex was used for homogenization. 100 µL of positive control was added to wells A1 and B1, 100 µL of negative control was added to wells C1 and D1, and 100 µL of milk samples were added to the remaining wells. The plate was covered with sterile plastic and incubated overnight at 5°C (±3°C). The wells were emptied and washed 5 times with at least 300 µL of wash solution. Ready-to-use conjugate was added to each well and incubated at 21°C (± 5°C) for 30 minutes (± 3 minutes). The wells were washed 3 times with at least 300 µL of wash solution. Substrate solution was added to each well and incubated at 21°C (± 5°C) in the dark for 15 minutes (± 2 minutes). Stop solution was added to each well in the same order as in other steps to stop the reaction. The Optical Density (OD) value at 450nm was read in an ELISA reader.

2.7. Test Validation and Interpretation

The test was valid if the mean value of the Negative Control OD (ODNC) was greater than 0.7, and if the mean value of the Positive Control OD (ODPC) was less than 30% of the ODNC. The competition percentage (S/N%) for each sample was determined using the formula: S⁄N % = (ODsample/ODNC) x 100. A result was classified as positive if the S/N% was 65% or less, and negative if it was greater than 65%.

2.8. Data Analysis

2.8.1. Descriptive Statistics

Numeric data such as OD value, S/N%, herd size, and the number of lactating cows, heifers, and calves on the farm, along with the number of abortions, retention of fetal membranes, repeat breeding cases per year, daily milk yield at herd level, age, lactation stage, number of calves, lactation stage, and daily average milk yield, were summarized using the `summary` function in R version 4.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The prevalence of BVD and its distribution across various categories were calculated using the `tabpct` function from the `epiDisplay` package in R 4.5.1. Additionally, the prevalence of BVD at both herd and cow levels, along with its 95% confidence interval, was determined using the `prop.test` function in R version 4.5.1.

2.8.2. Identification of Risk Factors

2.8.2.1. Herd-Level Risk Factors

A herd was classified as BVD positive if its bulk milk tested positive in the indirect ELISA. Numeric continuous variables were converted to categorical variables based on quartiles and medians. Initially, a univariable logistic regression analysis was conducted with BVD status as the outcome variable and each independent variable. Variables associated with BVD status, with a P-value ≤ 0.20, were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model. Multicollinearity among the selected variables was assessed using the vif() function from the “car” package in R 4.5.1. An adjusted VIF >5 was considered the threshold for multicollinearity [

12]. Stepwise multivariable logistic regression was used for the final model selection. Confounding and interaction were also checked using established methods [

13].

2.8.2.2. Cow-Level Risk Factors

A cow was classified as BVD positive if its milk tested positive in the indirect ELISA. Numeric continuous variables such as age, lactation stage, number of calves, and milk yield were converted to categorical variables, primarily based on quartiles and occasionally on medians. Similar to herd-level factors, an univariable mixed-effects logistic regression was initially used to evaluate the association between BVD status and each independent variable, with region as a random intercept. In the univariable screening, any variables associated with BVD status with a p-value of ≤ 0.20 were selected for the multivariable model. Multicollinearity among the selected variables was assessed using the same method described in the previous section [

12]. A stepwise mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression model was used to determine the final model. Confounding and interaction were also checked using similar methods described in the previous section[

12].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Herd

This study was conducted on 138 dairy herds from 14 districts in Bangladesh (

Figure 1).

The median herd size was 23.5, with an Interquartile Range (IQR) of 13 to 70.

Among these herds, the median number of lactating cows was 12, with an IQR of 5.25 to 31.75. The median number of calves was 4, with an IQR of 1 to 20. The median number of heifers and calves was 4 (IQR: 2 to 15), and 4 (IQR: 1 to 20), respectively. Both the median number of abortions and retained fetal membranes was 2, with an IQR of 0 to 3. The median number of anestrus cases was 1, with an IQR of 0 to 2, and the median number of repeat breeding cases was 2.5, with an IQR of 1 to 5. The median milk yield was 110 kg, with an IQR of 51.25 to 250.0 kg.

3.1.2. Cow

A total of 767 cow milk samples were tested from eight BVD positive herds across Bangladesh. The median age of the cows was 5.6 years (IQR: 4-8 years), with a median of 2 calves per cow (IQR: 1-3). The median lactation stage was 5 months (IQR: 3-8 months), and the median body weight was 360 kg (IQR: 280-400 kg). The median milk yield was 8.8 kg (IQR: 6.10-12.0 kg).

3.2. Herd and Cow-Level BVD Prevalence

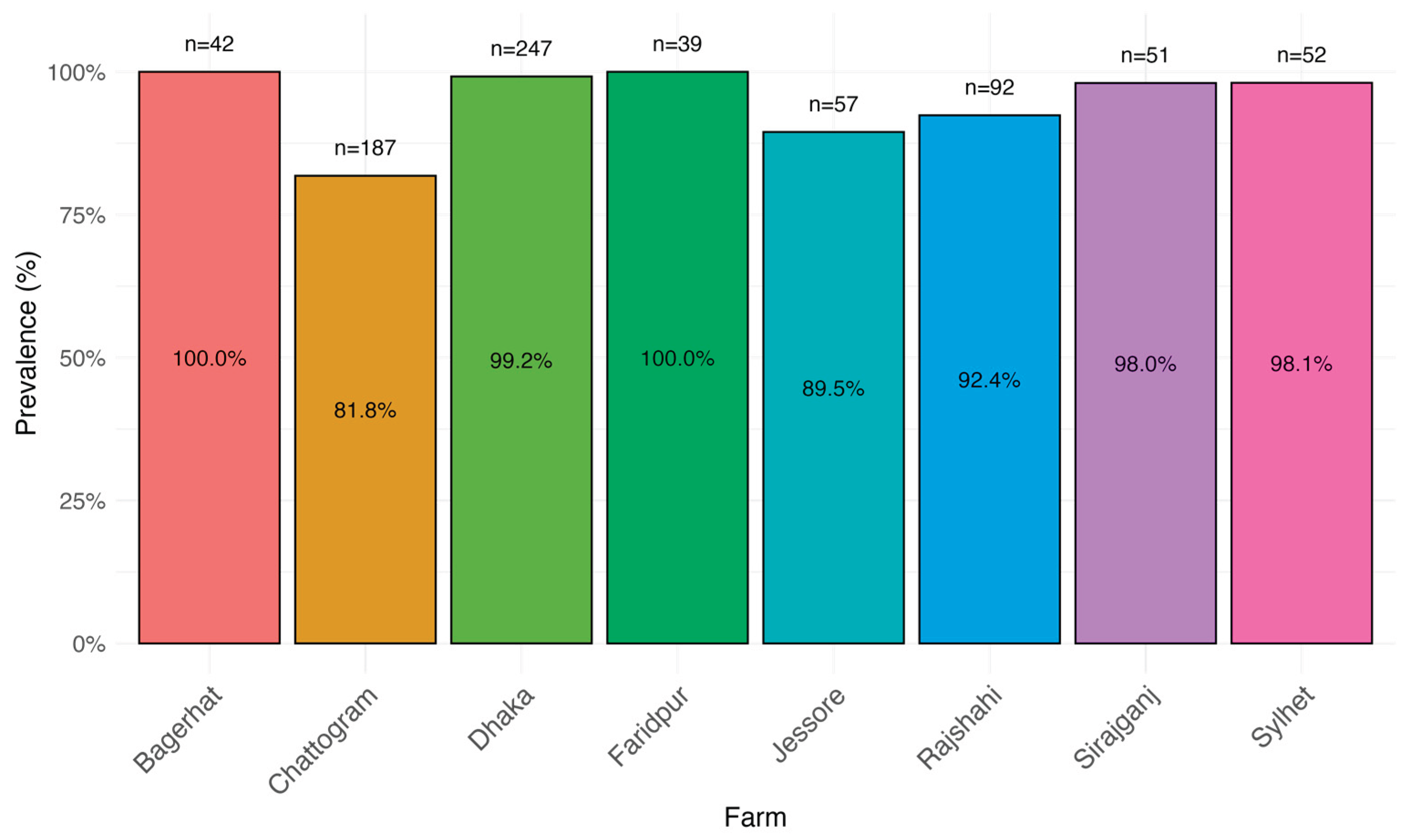

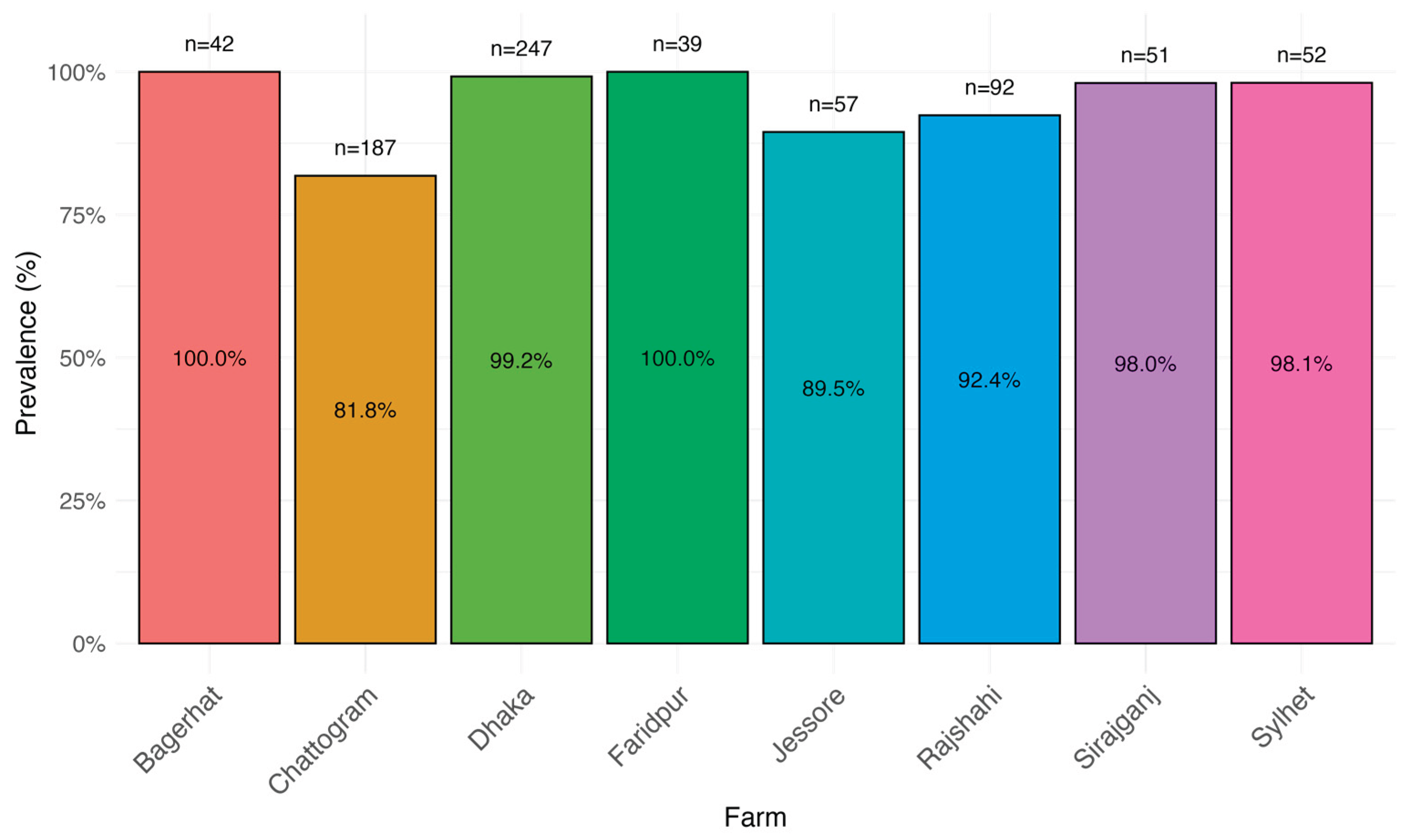

The overall prevalence of BVD at the herd level was 72.5% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 64.1-79.6). Among herds that tested positive for BVD, the cow-level prevalence was 93.3% (95% CI: 91.3-94.9%). The within herd prevalence among positive herds varied from 81.8% to 100% (Figure 2)

3.3. Risk Factors

3.3.1. Herd

In the univariable screening, herd size, the number of lactating cows, and semen source were associated with BVD at a p-value of 0.20 or less and were included in the multivariable logistic regression model (

Table 1). No multicollinearity was detected among these independent variables. In the final multivariable logistic regression model, herd size and semen source were identified as herd-level risk factors. Herds with more than 70 cows had 31.95 times higher odds of BVD (95% CI: 4.9-208.43) compared to herds with 13 to 23 cows. Compared to the reference semen source, BVD prevalence was significantly higher in the third (Odds Ratio (OR): 24.47, 95% CI: 4.09-146.53), fifth (OR: 8.99, 95% CI: 2.23-36.32), and eighth (OR: 23.55, 95% CI: 3.8-146.04) semen sources (

Table 2).

A total of 138 herds were examined from 14 different districts of Bangladesh. Herds from three specific districts tested negative for BVD. In the districts where BVD was detected, the prevalence varied significantly, with positivity rates among herds varying from 22.2% to 100% (Figure 2).

3.3.2. Cow

In the univariable screening, age, breed, physical condition, number of calves, and milk yield was associated BVD at P-value ≤02.0 (

Table 3).

No multicollinearity was detected among the explanatory variables. In the final mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression model, age, physical condition, and milk yield were identified as risk factors for BVD at the cow level (

Table 4). The odds of BVD were 4.53 times higher (95% CI: 1.90-10.77) in cows older than 8 years compared to those aged up to 4 years. Cows with a thin physical condition had 13.02 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.67-10.77) of BVD compared to those with a normal physical condition. Additionally, cows producing more than 8.8 kg of milk daily had a significantly lower prevalence of BVD (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.17-0.98) compared to those producing 8.8 kg or less of milk daily (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study described the prevalence and risk factors of BVD covering large geographic areas for the first time in Bangladesh. Bovine Viral Diarrhea seems to be highly endemic among herds and animals in Bangladesh. This study underscores the importance of addressing BVD through enhanced biosecurity measures, particularly in larger operations, and emphasizes the need for strict semen screening to prevent further spread. Good nutrition, management, targeted monitoring of vulnerable herds and animals, customized vaccination, and extension programs are essential for reducing BVD transmission, improving herd productivity, and mitigating the economic impact on Bangladesh’s dairy sector.

The herd-level prevalence of BVD was notably high, indicating a significant presence of the disease within the studied population. Nearly three-quarters of the herds are affected, suggesting widespread exposure or transmission within the region. No previous studies in Bangladesh have reported the herd-level prevalence of BVD, making it challenging to compare with the findings of this study. The within-herd prevalence among positive herds was also very high, ranging from 81.8% to 100%. It is reported that about 70-90% of BVD infections are subclinical, as observed in this study [

14]. In contrast, the overall herd-level prevalence of BVD in Tamil Nadu, India, was reported to be 27.17%, varying from 7.14% to 64.28% [

14]. The within-herd prevalence of BVD among positive herds varied from 2.40% to 32.00%. The prevalence of BVD may vary due to multiple reasons, such as the test method to detect antigen or antibodies, the presence of vaccination programs, biosecurity practices, and maintaining breeding bulls free from BVD, as BVD is a semen-borne disease [

15]. Vaccination against BVD is not yet practiced in Bangladesh, and biosecurity practices in dairy herds are very poor [

16]. Additionally, breeding bulls in Bangladesh are not tested for their BVD status. All of these factors may be responsible for the high level of BVD in dairy cows in the studied regions. This high prevalence underscores the need for robust control measures, enhanced biosecurity practices, and possibly improved vaccination strategies to mitigate the spread of BVD in the affected herds.

Herds with more than 70 cows had significantly higher prevalence of BVD in comparison to herds with 13 to 23 cows. Firstly, larger herds often lead to increased animal-to-animal contact, facilitating the rapid spread of infectious diseases like BVD. The density and frequency of interactions among cows create an environment conducive to virus transmission. Additionally, managing biosecurity measures effectively becomes more challenging as herd size increases, potentially leading to lapses that favor disease outbreaks. Secondly, larger herds may have more frequent introductions of new animals, which can introduce BVD if proper quarantine and health checks are not strictly enforced.

The study found a significant association between semen source and herd-level BVD. Three semen sources showed a significantly higher prevalence of BVD compared to the reference semen source. BVD is recognized as a semen-borne disease [

17]. Consequently, the Animal Diseases Rule of Bangladesh.[

18] recommends that all breeding bulls should be free from six semen-borne diseases: brucellosis, tuberculosis, BVD, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, campylobacteriosis, and trichomoniasis. Despite these recommendations, breeding bulls in both government and private bull stations are currently tested only for brucellosis and tuberculosis. Although breeding bulls were not tested in this study, we hypothesize that frozen semen could be a significant source of BVD transmission in Bangladesh.

The BVD prevalence was significantly higher in cows over eight years old compared to those aged up to 4 years. This result aligns with findings from other studies [

19,

20,

21]. This may be attributed to the extended lifespan of adult cattle, which increases their exposure to the virus and the likelihood of infection.

Cows with a thin physical condition had significantly higher prevalence of BVD comparison to those with a normal physical condition. Similar findings have also been reported from other authors [

10,

22]. As previously noted, it is challenging to establish a causal relationship from a cross-sectional study, which can be interpreted in various ways. However, poor body condition may be associated with a compromised immune system, making these cows more vulnerable to BVD infection. The weakened immune defenses in undernourished or stressed animals could allow the virus to enter and replicate more easily, resulting in a higher incidence of the disease.

The study revealed a negative correlation between BVD and milk yield, indicating that cows producing less milk (up to 8 kg) exhibit a significantly higher prevalence of BVD compared to those producing more milk (> 8 kg). This finding from a cross-sectional study cannot establish a causal relationship between BVD infection and milk yield. However, it’s well-documented that BVD-infected cows produce less milk than non-infected ones. This suggests a consistent pattern indicating BVD negatively impacts milk production [

23].

5. Conclusions

Bovine Viral Diarrhea is highly endemic among herds and animals in Bangladesh. Future surveillance should include regular screening of bulk milk samples from larger herds. Artificial insemination should use semen from BVD-free bulls. Cows with thin body condition and low milk production should be prioritized in individual cow surveillance. Emphasizing good nutrition, management, and targeted monitoring of vulnerable herds and animals, along with customized vaccination and extension programs, is essential for reducing BVD transmission, improving herd productivity, and mitigating the economic impact on Bangladesh’s dairy sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The herd and cow-level data used in this study have been provided as supplementary material S1 and S2, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AKMAR and MSR; methodology, MSMS, MSA, MNI, BJA and SI; software, MSMS, MSA, MNI, BJA, AKMAR; validation, MMI, BJA, and SI; formal analysis, MSA, MNI, BJA, MMI, and SI.; investigation, MSMS, MSA; resources, AKMAR, MSR; data curation, SI; writing—original draft preparation, MSMS, MSA, MNI; writing—review and editing, AKMAR, MSR, MMI; visualization, MNI, AKMAR; supervision, AKMAR; project administration, AKMAR, MSR; funding acquisition, AKMAR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Livestock and Dairy Development Project, grant number 2022/7/LDDP

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Welfare and Experimentation Ethical Committee (AWEEC) of Bangladesh Agricultural University (AWEEC/BAU/2022/07)

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results were provided as supplementary file A and B.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the dairy farmers for their participation int his and providing milk samples and data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LDDP |

Livestock and Dairy Development Project |

| ELISA |

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| BVD |

Bovine Viral Diarrhea |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| OD |

Optical Density |

| S/N |

Sample to Negative Ratio |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Wang, Y.; Pang, F. Diagnosis of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus: An Overview of Currently Available Methods. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; King, A.M.Q.; Harrach, B.; Harrison, R.L.; Knowles, N.J.; Kropinski, A.M.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.H.; Mushegian, A.R.; et al. Changes to Taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature Ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2017). Arch Virol 2017, 162, 2505–2538. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Meyers, G.; Bukh, J.; Gould, E.A.; Monath, T.; Scott Muerhoff, A.; Pletnev, A.; Rico-Hesse, R.; Stapleton, J.T.; Simmonds, P.; et al. Proposed Revision to the Taxonomy of the Genus Pestivirus, Family Flaviviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 98, 2106–2112. [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.; Hasanaj, A.; Deblon, C.; Gisbert, P.; Garigliany, M.-M. Genetic Diversity of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus in Cattle in France between 2018 and 2020. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- The Epidemiology and Control of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus in Tropical Indonesian Cattle Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/11/2/215 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Duan, H.; Ma, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, A.; Li, Z.; Xiao, S. A Novel Intracellularly Expressed NS5B-Specific Nanobody Suppresses Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Replication. Veterinary Microbiology 2020, 240, 108449. [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz, I.; Cerviño, M.; Martínez, S.; Fouz, R.; Diéguez, F.J. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) Infection: Effect on Reproductive Performance and Milk Yield in Dairy Herds. The Veterinary Journal 2021, 277, 105747. [CrossRef]

- Haider, N.; Rahman, M.S.; Khan, S.U.; Mikolon, A.; Gurley, E.S.; Osmani, M.G.; Shanta, I.S.; Paul, S.K.; Macfarlane-Berry, L.; Islam, A.; et al. Identification and Epidemiology of a Rare HoBi-Like Pestivirus Strain in Bangladesh. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2014, 61, 193–198. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.A.; Ahasan, A.S.M.L.; Islam, K.; Islam, Md.Z.; Mahmood, A.; Islam, A.; Islam, K.M.F.; Ahad, A. Seroprevalence of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus in Crossbred Dairy Cattle in Bangladesh. Vet World 2017, 10, 906–913. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.R.; Afrin, F.; Saha, S.S.; Jhontu, S.; Asgar, M.A. Prevalence and Haematological Parameters for Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (BVD) in South Bengal Areas in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Veterinarian 2015, 32, 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Control of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/7/1/29 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Hasan, A.; Ahmmed, M.T.; Prapti, B.B.R.; Rahman, A.; Islam, T.; Chouhan, C.S.; Rahman, A.K.M.A.; Siddique, M.P. First Report of MDR Virulent Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Apparently Healthy Japanese Quail (Coturnix Japonica) in Bangladesh. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0316667. [CrossRef]

- Bovine Tuberculosis Prevalence and Risk Factors in Selected Districts of Bangladesh | PLOS One Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0241717 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Kumar, S.K.; Palanivel, K.M.; Sukumar, K.; Ronald, B.S.M.; Selvaraju, G.; Ponnudurai, G. Herd-Level Risk Factors for Bovine Viral Diarrhea Infection in Cattle of Tamil Nadu. Trop Anim Health Prod 2018, 50, 793–799. [CrossRef]

- Givens, M.D. Control of Semen-Borne Pathogens. In Bovine Reproduction; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2021; pp. 1011–1018 ISBN 978-1-119-60248-4.

- Bushra, A.; Rokon-Uz-Zaman, Md.; Rahman, A.S.; Runa, M.A.; Tasnuva, S.; Peya, S.S.; Parvin, Mst.S.; Islam, Md.T. Biosecurity, Health and Disease Management Practices among the Dairy Farms in Five Districts of Bangladesh. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2024, 225, 106142. [CrossRef]

- Codes and Manuals. WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health.

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Animal Disease Rules, 2008 2008.

- Demil, E.; Fentie, T.; Vidal, G.; Jackson, W.; Lane, J.; Mekonnen, S.A.; Smith, W. Prevalence of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Antibodies and Risk Factors in Dairy Cattle in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2021, 191, 105363. [CrossRef]

- Antos, A.; Rola, J.; Bednarski, M.; Krzysiak, M.K.; Kęsik-Maliszewska, J.; Larska, M. Is Contamination of Bovine-Sourced Material with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Still a Problem in Countries with Ongoing Eradication Campaigns? Annals of Animal Science 2021, 21, 173–192. [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, K.; Sibhat, B.; Ayelet, G.; Skjerve, E.; Gebremedhin, E.Z.; Asmare, K. Seroprevalence and Factors Associated with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) Infection in Dairy Cattle in Three Milksheds in Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod 2018, 50, 1821–1827. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M.K.; Palomares, R.A.; White, B.J.; Engelken, T.J.; Brock, K.V. Prevalence of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) Persistently Infected Calves in Auction Markets from the Southeastern United States; Association between Body Weight and BVDV-Positive Diagnosis. The Professional Animal Scientist 2017, 33, 426–431. [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Steeneveld, W.; van der Voort, M.; van Schaik, G.; Vernooij, J.C.M.; van Duijn, L.; Veldhuis, A.M.B.; Hogeveen, H. The Effect of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Introduction on Milk Production of Dutch Dairy Herds. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 2074–2086. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).