Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

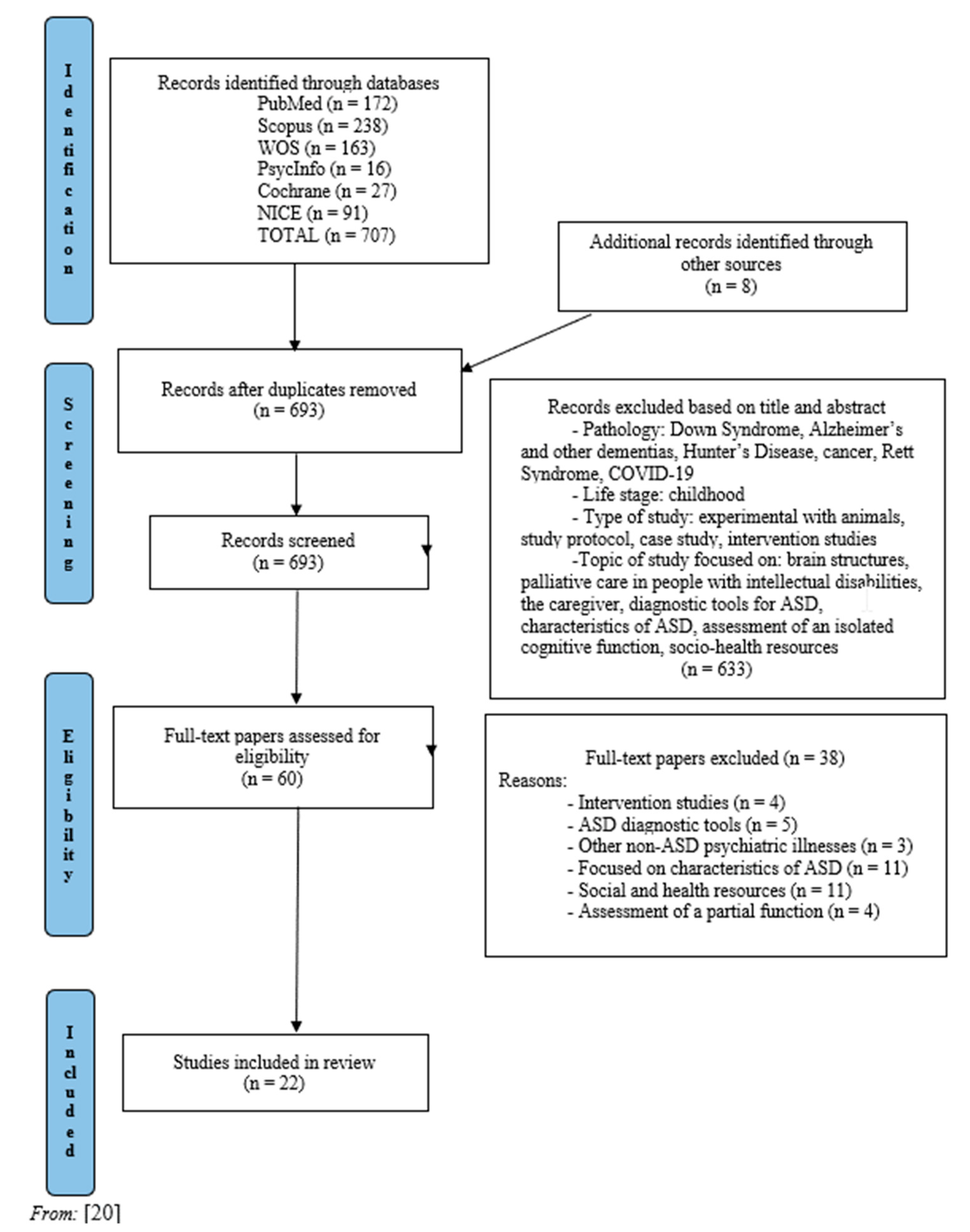

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Research Question

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Extraction

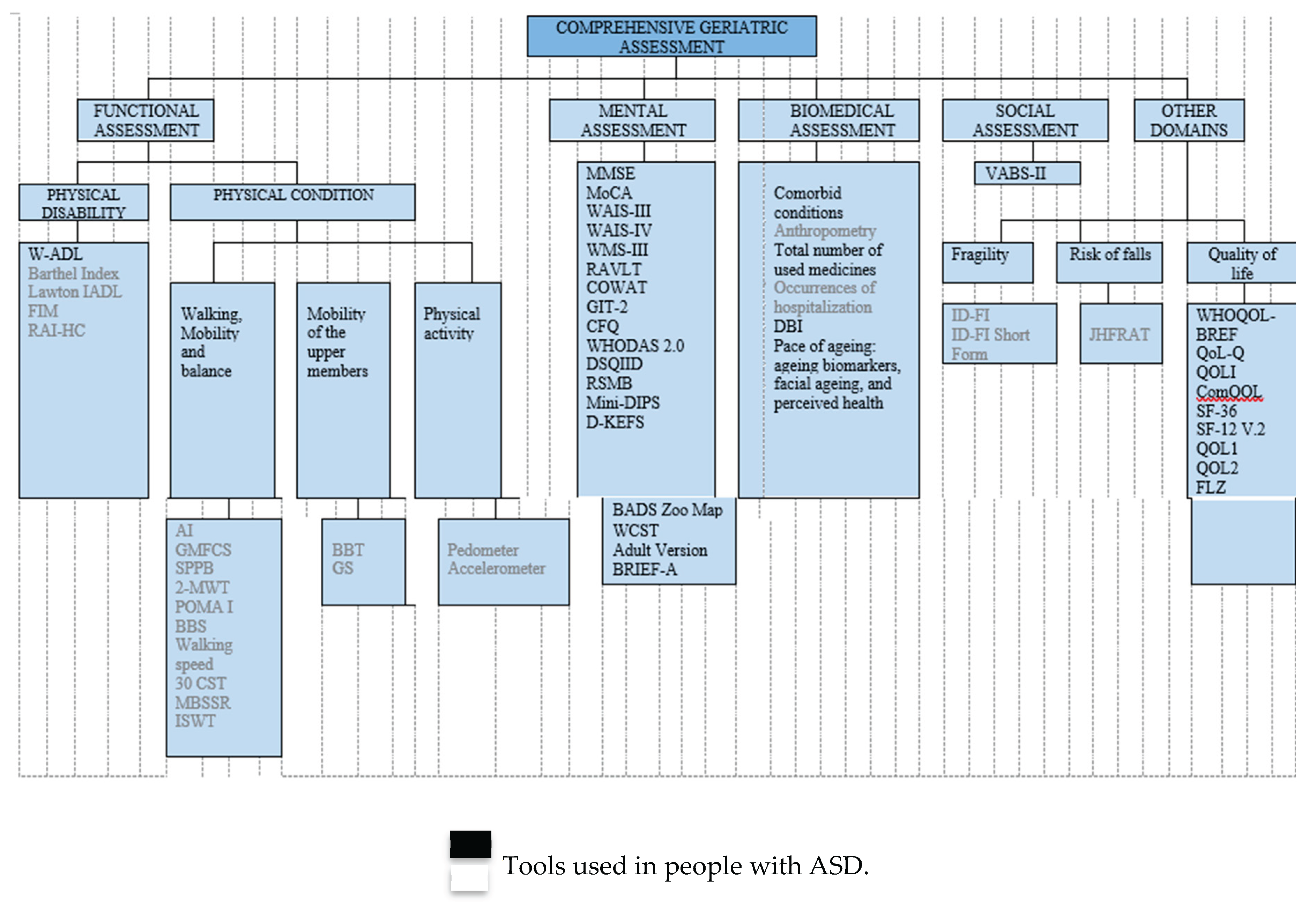

3. Results

3.1. Tools Used in People with ID Functional Assessment Tools

- -

- Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale (W-ADL), adapted for adults with developmental disabilities [25]. The W-ADL aims to measure the level of independence in performing typical daily activities including dressing, grooming, housework, meal-related activities, and activities outside the home [26].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Resident Assessment Instrument-Home Care (RAI-HC) [36]. This is a standardised assessment tool to assess the health status of long-stay home care clients, the need for care, and basic information about housing and informal caregivers [37]. The RAI-HC includes elements related to demographic characteristics, home environment, functioning, health, medications, informal support, and formal health services [38,39].

- -

- Hauser Ambulation Index (AI). This assesses the time and degree of assistance needed to walk 25 feet (independently, with a walker or wheelchair, or unable to move independently) [40].

- -

- -

- Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). It is one of the most common measures of physical performance in the ageing population [42]. The SPPB consists of three subtests: balance (standing with feet together, in semi-tandem, and tandem positions), leg strength (rising from and sitting back down in an armless chair five times as quickly as possible), and walking speed over 4 meters at a normal pace [43].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Modified Back-Saver Sit and Reach (MBSSR), for measuring flexibility. This is an extended and modified version of the sit-and-reach test with back support [47,50]. It is executed unilaterally on a Swedish bench, where a 30-centimeter measuring ruler is placed, placing the unassessed leg on the ground with a hip flexion of approximately 90º [29,32,47].

- -

- -

- -

- Grip Strength (GS) [53], for measuring the grip force of the dominant hand, typically using dynamometry. For the seated patient, the dominant arm is assessed by flexing it to 90 degrees and holding the dynamometer while performing a maximum grip for three to five seconds, followed by a recovery time of 30 seconds between three attempts, taking into account the best result [29,32,47].

- -

3.2. Mental Assessment Tools

- -

- -

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [57]. This has been designed to assess mild cognitive dysfunctions. This instrument examines the following skills: attention, concentration, executive functions (including the ability to abstract), memory, language, visuoconstructive skills, calculation, and orientation [58].

- -

- -

- Wechsler Memory Scale [WMS-III] [60,62] (Wechsler, 2003). The WMS-III is designed to assess the main aspects of memory functioning in adults aged between 16 and 89 years. It assesses episodic declarative memory—the ability to consciously store and retrieve specific aspects of information related to a particular situation or context—as well as working memory. The revised version of the WMS-III, the WMS-IV, incorporates the Brief Test for the Assessment of Cognitive Status (BCSE) as an additional test [63].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) [68]. This instrument measures the health and disability of adults over 18 years of age within a clinical or population context. It captures an individual’s level of functioning across six main life domains: comprehension and communication (cognition), movement (mobility), self-care (ability to maintain personal hygiene, dress, eat, and live independently), interpersonal interactions (social and interpersonal functioning), life activities (home, work, or school activities), and societal participation (engagement in family, social, and community activities) [69].

- -

- -

- -

- Diagnostic Interview for Mental Disorders - Short Version (Mini-DIPS) [72]. The Mini-DIPS is the short form of this structured interview, designed according to DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria, to assess current comorbidity (within 6 months) and covers the following disorders: anxiety, affective, somatisation, obsessive-compulsive, post-traumatic stress, acute stress, dissociative, and eating disorders [69].

- -

- -

- -

- -

3.3. Biomedical/Clinical Assessment Tools

- -

- Comorbid conditions. Sources include medical records, biological controls, and medical examinations. The physical examination covers cardiovascular, vascular, pulmonary, abdominal, neurological, ear, nose, and throat (ENT), skin, lymph nodes, thyroid, and assessment for orthostatic hypotension [8].

- -

- Anthropometry. This covers height, weight, and body mass index (BMI; kg m-2) [43].

- -

- -

- Hospitalisation occurrences. Hospitalisation is defined as a stay of at least one day in a standard hospital [78].

- -

- Drug Burden Index (DBI) [79]. This index is calculated using the anticholinergic load calculator (www. anticholinergicscales.es/calculate). The DBI is defined as the sum of the anticholinergic and sedative effects for each prescribed medication and is indirectly related to the use of psychotropic drugs [8].

- -

- Assessment of the pace of ageing. This includes ageing biomarkers [80,81], facial ageing, and perceived health. Nineteen biomarkers cover the main aspects of ageing: body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, glycosylated haemoglobin, leptin, mean arterial pressure, cardiorespiratory fitness, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein B100/A1 ratio, lipoprotein (a), creatinine clearance, urea nitrogen, C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, average periodontal attachment loss, and affected tooth decay or surfaces. Perceived health is assessed through self-reports, informants’ impressions, and interviewer’s impressions [7].

3.4. Social Valuation Tools

- -

3.5. Other Domains

- -

- Intellectual Disability-Frailty Index (ID-FI) and ID-FI Short Form. In the Healthy Ageing and Intellectual Disability (HA-ID) study, baseline data were collected across three subtopics: physical activity and fitness, nutrition and nutritional status, and mood and anxiety. A practical tool was developed to assess frailty in individuals with ID [78].

- -

- The Johns Hopkins Fall Risk Assessment Tool (JHFRAT) [83]. This composite scale comprises eight areas of assessment, classifying each risk factor for falls as follows: previous defining situations of risk, which include immobilisation (low risk), history of falls (high risk), history of falls during hospitalisation (high risk), and whether the patient is classified as high risk according to the protocols (high risk); age; medication; healthcare equipment; mobility; and cognition [43].

- -

- World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF) [84]. This is an abbreviated version of the original WHOQOL tool. It contains 26 items: two related to overall quality of life and satisfaction with health, and 24 grouped into four areas: physical health, psychological health, social relations, and environment [85].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Novel QoL measures (QOL1 and QOL2) [91]. This is an indirect assessment of the ‘autism-friendly environment’ and includes 5 items: staff/caregivers’ knowledge of autism, the application of structured education, the implementation of an individual treatment/training plan, the degree to which daily living/employment is appropriate to an individual’s ability, and the overall level of quality of life [85].

- -

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization, Decade of Healthy Ageing: Plan of Action 2021-2030, World Heal. Organ. (2020) 1–26. https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing.

- R.T. Sataloff, M.M. Johns, K.M. Kost, World report on ageing and health, Geneva, 2015. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- J.W. Rowe, R.L. Kahn, Successful aging, Gerontologist. 37 (1997) 433–440. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Rowe, R.L. Kahn, Human aging: usual and successful, Science 237 (1987) 143–149. [CrossRef]

- C. Lord, T. Brugha, T. Charman, J. Cusack, G. Dumas, T. Frazier, E. Jones, R. Jones, A. Pickles, M. State, J. Taylor, J. Veenstra-VanderWeele, Autism spectrum disorder, Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 6 (2020). [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM-5-TR), 5th-TR ed., Washington, 2022.

- D. Mason, A. Ronald, A. Ambler, A. Caspi, R. Houts, R. Poulton, S. Ramrakha, J. Wertz, T.E. Moffitt, F. Happé, Autistic traits are associated with faster pace of aging: Evidence from the Dunedin study at age 45, Autism Res. 14 (2021) 1684–1694. [CrossRef]

- S. Miot, R. Chancel, M. Peries, S. Crepiat, S. Couderc, E. Pernon, M.C. Picot, V. Gonnier, C. Jeandel, H. Blain, A. Baghdadli, Multimorbidity patterns and subgroups among autistic adults with intellectual disability: Results from the EFAAR study, Autism. 27 (2023) 762–777. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Questions & answers on autism spectrum disorders (ASD) [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/autism-spectrum-disorders-(asd).

- L. Bishop-Fitzpatrick, E. Rubenstein, The physical and mental health of middle aged and older adults on the autism spectrum and the impact of intellectual disability, Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 63 (2019) 34–41. [CrossRef]

- S.S. Kuo, C. Van der Merwe, M.E. Fu, J.M. Carey, C.E. Talkowski, S.L. Bishop, E.B. Robinson, Developmental variability in autism across 17000 autistic individuals and 4000 siblings without an autism diagnosis: comparisons by cohort, intellectual disability, genetic etiology, and age at diagnosis, JAMA Pediatr. 176 (2022) 915–923. [CrossRef]

- L. Croen, O. Zerbo, Y. Qian, M. Massolo, S. Rich, S. Sidney, C. Kripke, The health status of adults on the autism spectrum, Autism. 19 (2015) 814–823. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Healthy ageing: adults with intellectual disabilities: summative report, World Health Organization, 2000. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/66367.

- M. Reza-Goyanes, Efectividad terapias conductuales en los trastornos del espectro autista, Plan de Calidad para el SNS del MSSSI. Unidad de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias, Agencia Laín Entralgo. Informes de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias: UETS 2011/05, Madrid, 2012. http://www.madrid.org/bvirtual/BVCM017399.pdf.

- P. Abizanda Soler, C. Cano Gutiérrez, Medicina geriátrica. Una aproximación basada en problemas, 2nd ed., Elsevier Health Sciences Spain, Barcelona, 2020.

- A. Pilotto, A. Cella, A. Pilotto, J. Daragjati, N. Veronese, C. Musacchio, A. Mello, G. Logroscino, A. Padovani, C. Prete, F. Panza, Three decades of comprehensive geriatric assessment: evidence coming from different healthcare settings and specific clinical conditions, J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18 (2017) 192.e1–192.e11. [CrossRef]

- L. Nylander, A. Axmon, P. Björne, G. Ahlström, C. Gillberg, Older adults with autism spectrum disorders in Sweden: a register study of diagnoses, psychiatric care utilization and psychotropic medication of 601 individuals, J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48 (2018) 3076–3085. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Wise, Aging in autism spectrum disorder, Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 28 (2020) 339–349. [CrossRef]

- S.D. Wright, C.A. Wright, V. D’Astous, A.M. Wadsworth, Autism aging, Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 40 (2016) 322–338. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Tricco, E. Lilliee, W. Zarin, K.K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, et al., PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation, Ann. Intern. Med. 169 (7) (2018) 467–473. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, J. Lin, D. Demner-Fushman, Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions., AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. (2006) 359–363. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1839740/.

- R. Armstrong, N. Jackson, J. Doyle, E. Waters, F. Howes, It’s in your hands: The value of handsearching in conducting systematic reviews of public health interventions, J. Public Health (Bangkok). 27 (2005) 388–391. [CrossRef]

- S. Jalali, C. Wohlin, Systematic literature studies: Database searches vs. backward snowballing, Int. Symp. Empir. Softw. Eng. Meas. (2012) 29–38. [CrossRef]

- E. Aromataris, Z. Munn, JBI Reviewer’s Manual, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Maenner, L.E. Smith, J. Hong, R. Makuch, J.S. Greenberg, M.R. Mailick, Evaluation of an activities of daily living scale for adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities, Disabil. Health J. 6 (2013) 8–17. [CrossRef]

- Y.I. Hwang, K.R. Foley, J.N. Trollor, Aging Well on the Autism Spectrum: An Examination of the Dominant Model of Successful Aging, J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50 (2020) 2326–2335. [CrossRef]

- F.I. Mahoney, D.W. Barthel, Functional evaluation: the Barthel index, Md State Med. J. 14 (1965) 61–5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14258950/.

- J.R. Maring, E. Costello, M.C. Birkmeier, M. Richards, L.M. Alexander, Validating functional measures of physical ability for aging people with intellectual developmental disability, Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 118 (2013) 124–140. [CrossRef]

- A. Oppewal, T.I.M. Hilgenkamp, R. van Wijck, J.D. Schoufour, H.M. Evenhuis, Physical fitness is predictive for a decline in daily functioning in older adults with intellectual disabilities: Results of the HA-ID study, Res. Dev. Disabil. 35 (2014) 2299–2315. [CrossRef]

- J. Schoufour, H. Evenhuis, M. Echteld, The impact of frailty on care intensity in older people with intellectual disabilities, Res. Dev. Disabil. 35 (2014) 3455–3461. [CrossRef]

- M. Lawton, E. Brody, Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities daily living, Gerontologist. 9 (1969) 179–86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5349366/.

- A. Oppewal, T.I.M. Hilgenkamp, R. van Wijck, J.D. Schoufour, H.M. Evenhuis, Physical fitness is predictive for a decline in the ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living in older adults with intellectual disabilities: Results of the HA-ID study, Res. Dev. Disabil. 41–42 (2015) 76–85. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Schoufour, A. Mitnitski, K. Rockwood, T.I.M. Hilgenkamp, H.M. Evenhuis, M.A. Echteld, Predicting disabilities in daily functioning in older people with intellectual disabilities using a frailty index, Res. Dev. Disabil. 35 (2014) 2267–2277. [CrossRef]

- S. Shah, F. Vanclay, B. Cooper, Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation, J. Clin. Epidemiol. 42 (1989) 703–709. [CrossRef]

- J. Linacre, A. Heinemann, B. Wright, C. Granger, B. Hamilton, The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure, Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 75 (1994) 127–32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8311667/.

- J. Morris, B. Fries, R. Bernabei, K. Steel, N. Ikegami, I. Carpenter, R. Gilgen, J. DuPasquier, J. Friters, D., Henrard, J. Hirdes, P. Belleville-Taylor, K. Berg, M. Björkgren, L. Gray, G. Hawes, G. Ljunggren, S. Nonemaker, D. Phillips, C, interRAI Home Care (HC) assessment form and user’s manual (9.1 ed.), interRAI, Washington, DC, 2009.

- A.Wagner, R. Schaffert, N. Möckli, F. Zúñiga, J. Dratva, Home care quality indicators based on the Resident Assessment Instrument-Home Care (RAI-HC): A systematic review, BMC Health Serv. Res. 20 (2020) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- K. McKenzie, H. Ouellette-Kuntz, L. Martin, Using an accumulation of deficits approach to measure frailty in a population of home care users with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An analytical descriptive study Public health, nutrition and epidemiology, BMC Geriatr. 15 (2015) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- K. McKenzie, H. Ouellette-Kuntz, L. Martin, Frailty as a predictor of institutionalization among adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 54 (2016) 123–135. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Hauser, D.M. Dawson, J.R. Lehrich, M.F. Beal, S. V. Kevy, R.D. Propper, J.A. Mills, H.L. Weiner, Intensive immunosuppression in progressive multiple sclerosis. A randomized, three-arm study of high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide, plasma exchange, and ACTH., N. Engl. J. Med. 308 (1983) 173–180. [CrossRef]

- R. Palisano, P. Rosenbaum, S. Walter, D. Russell, E. Wood, B. Galuppi, Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy, Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 39 (1997) 214–223. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Guralnik, L. Ferrucci, E.M. Simonsick, M.E. Salive, R.B. Wallace, Lower-Extremity Function in Persons over the Age of 70 Years as a Predictor of Subsequent Disability, N. Engl. J. Med. 332 (1995) 556–562. [CrossRef]

- P. Choi, T. Wei, R.W. Motl, S. Agiovlasitis, Risk factors associated with history of falls in adults with intellectual disability, Res. Dev. Disabil. 106 (2020) 103748. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Butland, J. Pang, E. Gross, A.A. Woodcock, D.M. Geddes, Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease, Br. Med. J. 284 (1982) 1607–1608. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Tinetti, Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 34 (1986) 119–126. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Tinetti, Factors associated with serious injury during falls by ambulatory nursing home residents., He Amer- Ican Geriatr. Soc. 35 (1987) 644–648. [CrossRef]

- T.I.M. Hilgenkamp, R. van Wijck, H.M. Evenhuis, Physical fitness in older people with ID-Concept and measuring instruments: A review, Res. Dev. Disabil. 31 (2010) 1027–1038. [CrossRef]

- R.W. Bohannon, Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: Reference values and determinants, Age Ageing. 26 (1997) 15–19. [CrossRef]

- R.E. Rikli, C.J. Jones, Senior fitness test manual, 2nd ed., Human kinetics, USA, 2013.

- S.S.C. Hui, P.Y. Yuen, Validity of the modified back-saver sit-and-reach test: A comparison with other protocols, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32 (2000) 1655–1659. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Singh, M.D.L. Morgan, S. Scott, D. Walters, A.E. Hardman, Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction, Thorax. 47 (1992) 1019–1024. [CrossRef]

- V. Mathiowetz, G. Volland, N. Kashman, K. Weber, Adult Norms for the Box and Block Test of Manual Dexterity, Am. J. Occup. 39 (1985) 386–391. [CrossRef]

- V. Mathiowetz, N. Kashman, G. Volland, K. Weber, M. Dowe, S. Rogers, Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 66 (1985) 69–74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3970660/.

- M.F. Folstein, S.E. Folstein, P. McHugh, ‘Mini-mental state’ A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician, J. Psychiatr. Researc. 12 (1975) 189–198. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Lever, H.M. Geurts, Age-related differences in cognition across the adult lifespan in autism spectrum disorder, Autism Res. 9 (2016) 666–676. [CrossRef]

- C. Torenvliet, A.P. Groenman, T.A. Radhoe, J.A. Agelink van Rentergem, W.J. Van der Putten, H.M. Geurts, A longitudinal study on cognitive aging in autism, Psychiatry Res. 321 (2023) 115063. [CrossRef]

- Z.S. Nasreddine, N.A. Phillips, V. Bédirian, S. Charbonneau, V. Whitehead, I. Collin, J.L. Cummings, H. Chertkow, The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53 (2005) 695–699. [CrossRef]

- I.Z. Groot, A.G. Lever, P.C. Koolschijn, H.M. Geurts, Brief Report: Using Cognitive Screeners in Autistic Adults, J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51 (2021) 3374–3379. [CrossRef]

- D. Wechsler, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS- III), Psychological Corporation., San Antonio, TX, 1997.

- D. Wechsler, Wechsler adult intelligence scale – Fourth edition (WAIS-IV), Pearson Prentice Hall, San Antonio TX, 2003.

- H.M. Geurts, S.E. Pol, J. Lobbestael, C.J.P. Simons, Executive functioning in 60+ autistic males: The discrepancy between experienced challenges and cognitive performance, J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50 (2020) 1380–1390. [CrossRef]

- D. Wechsler, Wechsler memory scale (WMS-III), Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX, 1997.

- C. Torenvliet, A.P. Groenman, T.A. Radhoe, J.A. Agelink van Rentergem, W.J. Van der Putten, H.M. Geurts, Parallel age-related cognitive effects in autism: A cross-sectional replication study, Autism Res. 15 (2022) 507–518. [CrossRef]

- A.Rey, L’examen clinique en Psychologie (The Clinical Psychological Examination), Pressee Universitaires de France, Paris, 1964.

- A.L. Benton, Differential behavioral effects in frontal lobe disease, Neuropsychologia. 6 (1968) 53–60. [CrossRef]

- F. Luteijn, D.P.H. Barelds, Groningen Intelligence Test 2 (GIT-2): Manual, Amsterdam: Pearson Assessment, 2004.

- D.E. Broadbent, P.F. Cooper, P. FitzGerald, K.R. Parkes, The cognitive failures questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates, Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 21 (1982) 1–16. [CrossRef]

- T.B. Üstün, S. Chatterji, N. Kostanjsek, J. Rehm, C. Kennedy, J. Epping-Jordan, S. Saxena, M. von Korff, C. Pull, Developing the world health organization disability assessment schedule 2.0, Bull. World Health Organ. 88 (2010) 815–823. [CrossRef]

- L. Schmidt, J. Kirchner, S. Strunz, J. Broźus, K. Ritter, S. Roepke, I. Dziobek, Psychosocial Functioning and Life Satisfaction in Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder Without Intellectual Impairment, J. Clin. Psychol. 71 (2015) 1259–1268. [CrossRef]

- S. Deb, M. Hare, L. Prior, S. Bhaumik, Dementia screening questionnaire for individuals with intellectual disabilities, Br. J. Psychiatry. 190 (2007) 440–444. [CrossRef]

- S. Reiss, Reiss screen for maladaptive behavior, IDS Publishing Corporation, McLean: USA, 1987.

- J. Margraf, Mini-DIPS - Diagnostisches Kurz-Interview bei psychischen Störungen (Diagnostic Interview for Mental Disorders - Short Version), Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 1994.

- D.C. Delis, E. Kaplan, J.H. Kramer, Delis-Kaplan executive function system (D–KEFS) [Database record], APA PsycTests. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1037/t15082-000.

- B.A. Wilson, N. Alderman, P.W. Burgess, H.C. Emslie, J.J. Evans, The Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome, Thames Valley Test Company, Flempton, Bury St Edmunds, 1996.

- B.A. Wilson, J.J. Evans, H. Emslie, N. Alderman, P. Burgess, The development of an ecologically valid test for assessing patients with a dysexecutive syndrome, Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 8 (1998) 213–228. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Grant, E. Berg, A behavioral analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card-sorting problem, J. Exp. Psychol. 38 (1948) 404–411. [CrossRef]

- R.M. Roth, P.K. Isquith, G. Gioia, BRIEF-A: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Adult Version: Profesional Manual, PAR., Odessa (Florida), 2005.

- J.D. Schoufour, M. Echteld, L. Bastiaanse, H. Evenhuis, The use of a frailty index to predict adverse health outcomes (falls, fractures, hospitalization, medication use, comorbid conditions) in people with intellectual disabilities, Res. Dev. Disabil. 38 (2015) 39–47. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Byrne, C. Walsh, C. Cahir, C. Ryan, D.J. Williams, K. Bennett, Anticholinergic and sedative drug burden in community-dwelling older people: A national database study, BMJ Open. 8 (2018) 1–8. [CrossRef]

- D.W. Belsky, A. Caspi, R. Houts, H.J. Cohen, D.L. Corcoran, A. Danese, H. Harrington, S. Israel, M.E. Levine, J.D. Schaefer, K. Sugden, B. Williams, A.I. Yashin, R. Poulton, T.E. Moffitt, Quantification of biological aging in young adults, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (2015) E4104–E4110. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Elliott, A. Caspi, R.M. Houts, A. Ambler, J.M. Broadbent, R.J. Hancox, H. Harrington, S. Hogan, R. Keenan, A. Knodt, J.H. Leung, T.R. Melzer, S.C. Purdy, S. Ramrakha, L.S.Richmond-Rakerd, A. Righarts, K. Sugden, W.M. Thomson, P.R. Thorne, B.S. Williams, G. Wilson, A.R. Hariri, R. Poulton, T.E. Moffitt. Disparities in the pace of biological aging among midlife adults of the same chronological age have implications for future frailty risk and policy, Nat. Aging. 1 (2021) 295–308. [CrossRef]

- S. Sparrow, D. Balla, D. Cichetti, The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Interview edition, Expanded form, American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, 1984.

- S.S. Poe, M. Cvach, P.B. Dawson, H. Straus, E.E. Hill, The Johns Hopkins fall risk assessment tool: Postimplementation evaluation, J. Nurs. Care Qual. 22 (2007) 293–298. [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group, Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment, Psychol. Med. 28 (1998) 551–558. [CrossRef]

- M. Ayres, J.R. Parr, J. Rodgers, D. Mason, L. Avery, D. Flynn, A systematic review of quality of life of adults on the autism spectrum, Autism. 22 (2018) 774–783. [CrossRef]

- R.L. Schalock, K.D. Keith, Quality of Life Questionnaire (QOL.Q) [Database record], APA PsycTests Database Rec. (1993). [CrossRef]

- M.B. Frisch, J. Cornell, M. Villanueva, P.F. Retzlaff, Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory. A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment, Psychol. Assess. 4 (1992) 92–101. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Cummins, Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale - Intellectual/Cognitive Disability fifth edition (ComQol-I5), 1997. http://sid.usal.es/idocs/F5/EVA66/ComQol_I5.pdf.

- J.E. Ware, C.D. Sherbourne, The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), Med. Care. 30 (1992) 473–483. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1593914/.

- S. Schmidt, G. Vilagut, O. Garin, O. Cunillera, R. Tresserras, P. Brugulat, A. Mompart, A. Medina, M. Ferrer, J. Alonso, Reference guidelines for the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 based on the Catalan general population, Med Clin. 139 (2012) 613–25. [CrossRef]

- E. Billstedt, I.C. Gillberg, C. Gillberg, Aspects of quality of life in adults diagnosed with autism in childhood: A population-based study, Autism. 15 (2011) 7–20. [CrossRef]

- J. Fahrenberg, M. Myrtek, J. Schumacher, E. Brähler, Fragebogen zur Lebenszufriedenheit (FLZ) Handanweisungen.Life Satisfaction Questionnaire, Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2000.

- J.D. Schoufour, A. Mitnitski, K. Rockwood, H.M. Evenhuis, M.A. Echteld, Predicting 3-year survival in older people with intellectual disabilities using a frailty index, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 63 (2015) 531–536. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Schoufour, A. Oppewal, M.C. van Maurik, T.I.M. Hilgenkamp, R.G. Elbers, D.A.M. Maes-Festen, Development and validation of a shortened and practical frailty index for people with intellectual disabilities, J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 66 (2022) 240–249. [CrossRef]

| INCLUSION |

| Studies including ageing/elderly people with ASD with or without ID |

| EXCLUSION |

| Pathology: Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s and other dementias, Hunter’s disease, cancer, Rett syndrome, COVID-19 |

| Life stage: childhood stage |

| Type of study: experimental with animals, study protocol, case study, intervention studies |

| Topic of study: brain structures, palliative care in people with intellectual disabilities, caregivers, diagnostic tools and characteristics of ASD, assessment of isolated cognitive function, socio-health resources |

| Author (year)/country | Study design | Assessment | Participants and range years or mean age | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayres et al. (2018) /UK | Systematic review | -WHOQOL-BREF -QoL-Q -QOLI -ComQOL -SF-36 -SF-12 v.2 -QOL1 and QOL2 |

N=959 18-83 years |

No comprehensive, autism spectrum disorder–specific quality of life measurement tools have been validated. |

| Choi et al. (2020) /Southeast of the United States | Cohort study | -Anthropometrics -JHFRAT -SF-36 -SPPB -Accelerometer |

N=80 43±13 years |

Adults with ID who experience falls are more likely to need support with ADLs, be older, and have arthritis, rheumatism, and walking problems than adults with ID who do not experience falls. |

| Geurts et al (2000) /Netherlands | Cross-sectional | -WAIS IV -D-KEFS -BADS Zoo Map -WCST -Adult BRIEF-A |

N=101 60-85 years |

Subjective measures offer valuable insight into everyday executive functioning and the experienced problems in an ASC population. |

| Groot et al. (2020) /Netherlands | Case-control | -MMSE-NL -MoCA-NL |

N=100 30-73 years |

There is no difference in performance between people with and without an ASC on the MMSE-NL or MoCA-NL. |

| Hilgenkamp et al. (2010) /Netherlands | Systematic review | -BBT -BBS -POMA I -Walking speed -GS -30 CST -MBSSR -ISWT |

Older adults (age is not specified) | The following are proposed for measuring physical fitness: BBT, reaction time test, BBS, walking speed, GS, 30 CST, MBSSR, and ISWT. |

| Hwang et al. (2020) /Australia | Cross-sectional | -W-ADL -SF-12 -WHODAS 2.0 |

N=152 40-79 years |

Significantly less autistic adults were ‘maintaining physical and cognitive functioning’ and ‘actively engaging with life’ in comparison to controls. The current dominant model of ‘ageing well’ is limited for examining autistic individuals. |

| Lever and Geurts (2016) /Netherlands | Cross-sectional | -WAIS III -MMSE -WMS-III -RAVLT -COWAT -GIT-2 -CFQ |

N=236 20-79 years |

Age-related differences characteristic of typical ageing are reduced or parallel, but not increased, in individuals with ASD. |

| Maring et al. (2013)/ USA | Systematic review and pilot study | -Barthel Index -FIM -POMA I -2-MWT |

N=30 >50 years |

The measures are strongly associated and successfully distinguished between participants with an adverse health event in the previous year. |

| Mason et al. (2020) /New Zealand | Cohort design | -Pace of ageing: ageing biomarkers, facial ageing, perceived health | N=915 3-45 years |

They found that higher autistic traits were associated with poorer physical health and a faster pace of ageing. |

| McKenzie (2016) /Ontario Canada | Cohort design | RAI-HC | N=3034 18-99 years |

Frail individuals had greater rates of admission than non-frail individuals. The FI predicts institutionalisation. |

| McKenzie et al. (2015) /Ontario, Canada | Cohort study | -RAI-HC | N=7.863 18-99 years |

Using the FI to identify frailty in adults with IDD is feasible and may be incorporated into existing home care assessments. |

| Miot et al. (2023) /France | Cohort design | -VABS-II -Total number of medications -DBI -Comorbidities -DSQIID -RSMB |

N=63 25-59 years |

Spectrum disorder + intellectual disability individuals can be identified based on their multimorbidity and potentially different ageing trajectories. |

| Oppewal et al. (2014) /Netherlands | Cohort design | -BBT -BBS -Walking speed -GS -30 CST -MBSSR -ISWT |

N=602 >50 years |

Physical fitness significantly predicts a decline in daily functioning in older adults with ID. |

| Oppewal et al. (2015) /Netherlands | Cohort design | -BBT -BBS -Walking speed -GS -30 CST -MBSSR -ISWT -Lawton IADL |

N=601 >50 years |

Physical fitness is found to be an important aspect for IADL. |

| Schmidt et al. (2015) /Germany | Cross-sectional | -Mini-DIPS -WHODAS 2.0 -FLZ |

N=87 Age: mean =31 |

Adults on the autism spectrum without intellectual impairment experience significant functional impairments in social domains, but they are relatively competent in daily living skills. |

| Schoufour et al. (2022) /Netherlands | Longitudinal and case series | -ID-FI -ID-FI Short Form |

N=982 >50 years |

A practical tool to assess the frailty status of people with ID is introduced. |

| Schoufour, Echteld, et al. (2015) /Netherlands | Cohort design | -Occurrences of hospitalisation -Total number of used medicines -Comorbid conditions -ID-FI |

N=982 >50 years |

The FI was related to an increased risk of higher medication use and several comorbid conditions, although not to falls, fractures, and hospitalisation. |

| Schoufour, Evenhuis, et al. (2014) / Netherlands | Cohort design | -Barthel Index -Lawton IADL -ID-FI |

N=676 >50 years |

Increased care during the follow-up was related to a high frailty index score at baseline. |

| Schoufour, Mitnitski, et al. (2014) / Netherlands | Cohort design | -Barthel Index -Lawton IADL -AI -GMFCS -ID-FI -Pedometer |

N=703 >50 years |

The FI demonstrated the highest predictive value for individuals with high baseline mobility or independence in IADLs. |

| Schoufour, Mitnitski, et al. (2015) /Netherlands | Cohort design | -ID-FI | N=982 >50 years |

The predictive validity of the FI was strongly associated with 3-year mortality. |

| Torenvliet et al. (2021) /Netherlands | Cohort design | -RAVLT -WMS-III -COWAT -GIT-2 -CFQ |

N=176 30-89 years |

Previously observed difficulties in Theory of Mind and verbal fluency, which appear to persist into older age, were replicated. |

| Torenvliet et al. (2023) /Netherlands | Cohort design | -CFQ -WAIS III/IV -MMSE |

N = 464 24-85 years |

Autistic individuals diagnosed in adulthood, without intellectual disability, do not seem at risk for accelerated cognitive decline. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).