Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

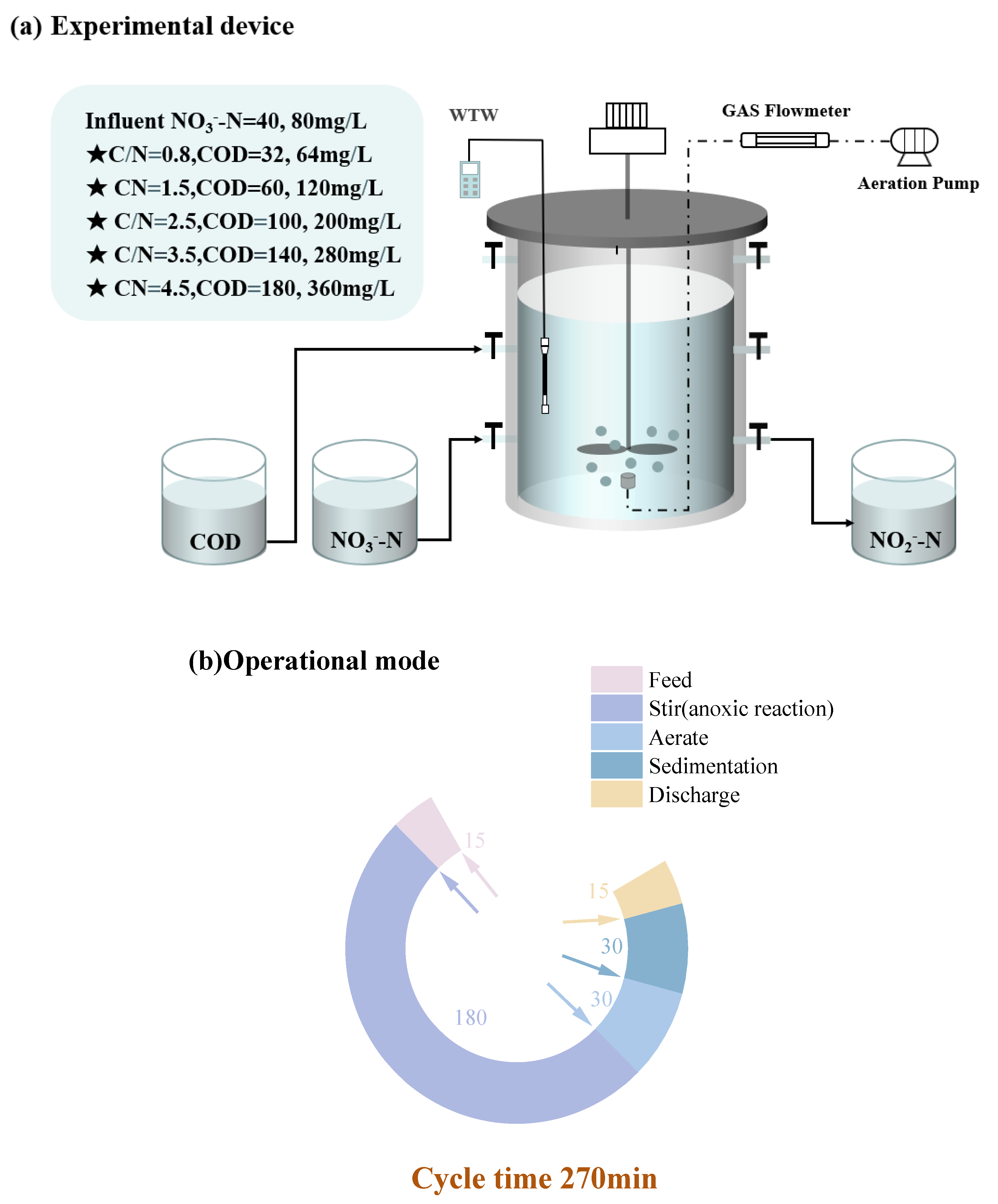

2.1. Experimental Device and Operational Mode

2.2. Seeding Sludge and Synthetic Wastewater

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. High-Throughput Sequencing

3. Results and Discussion

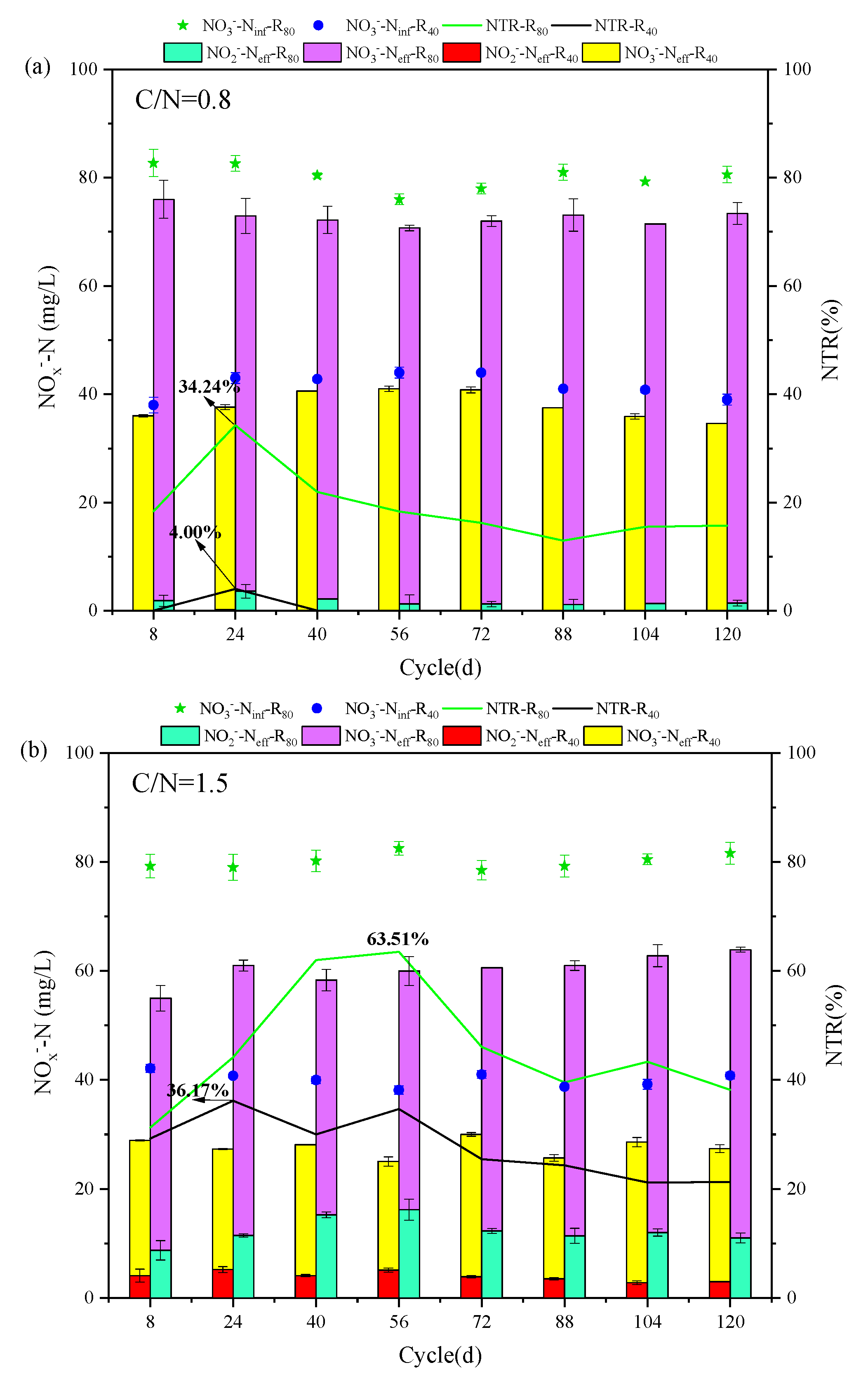

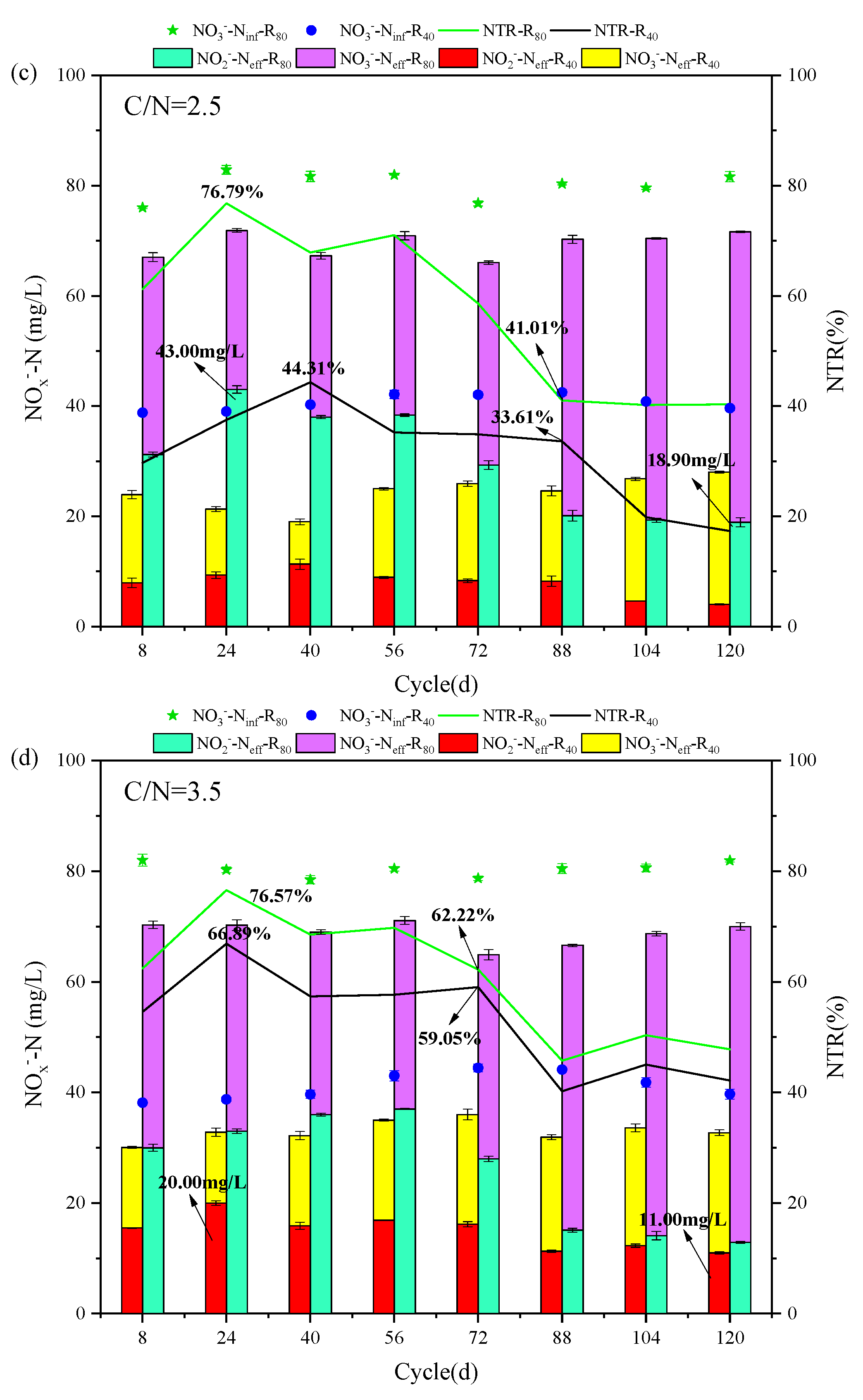

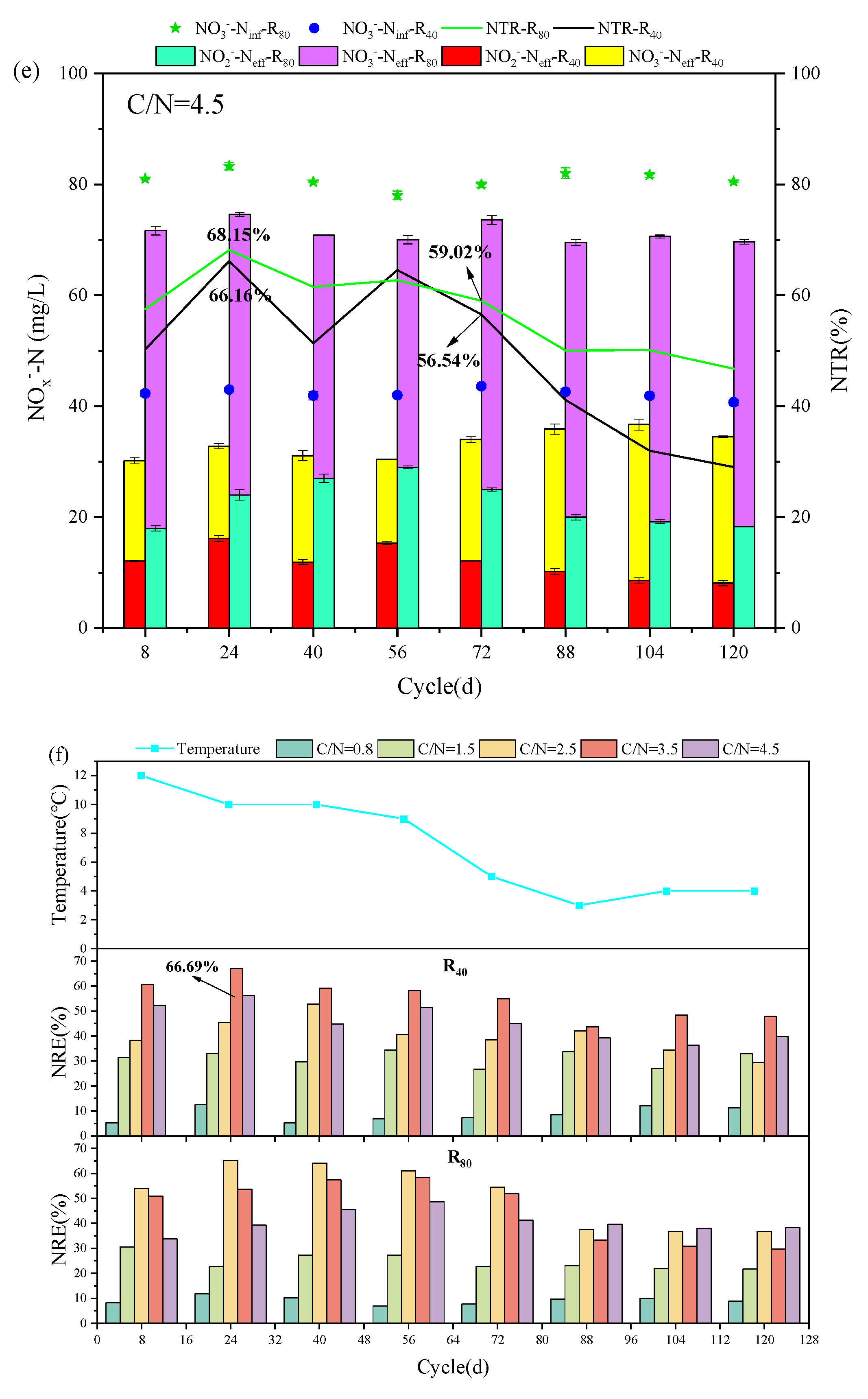

3.1. Substrate Variation and Nitrite Accumulation in the Long-Term Operation

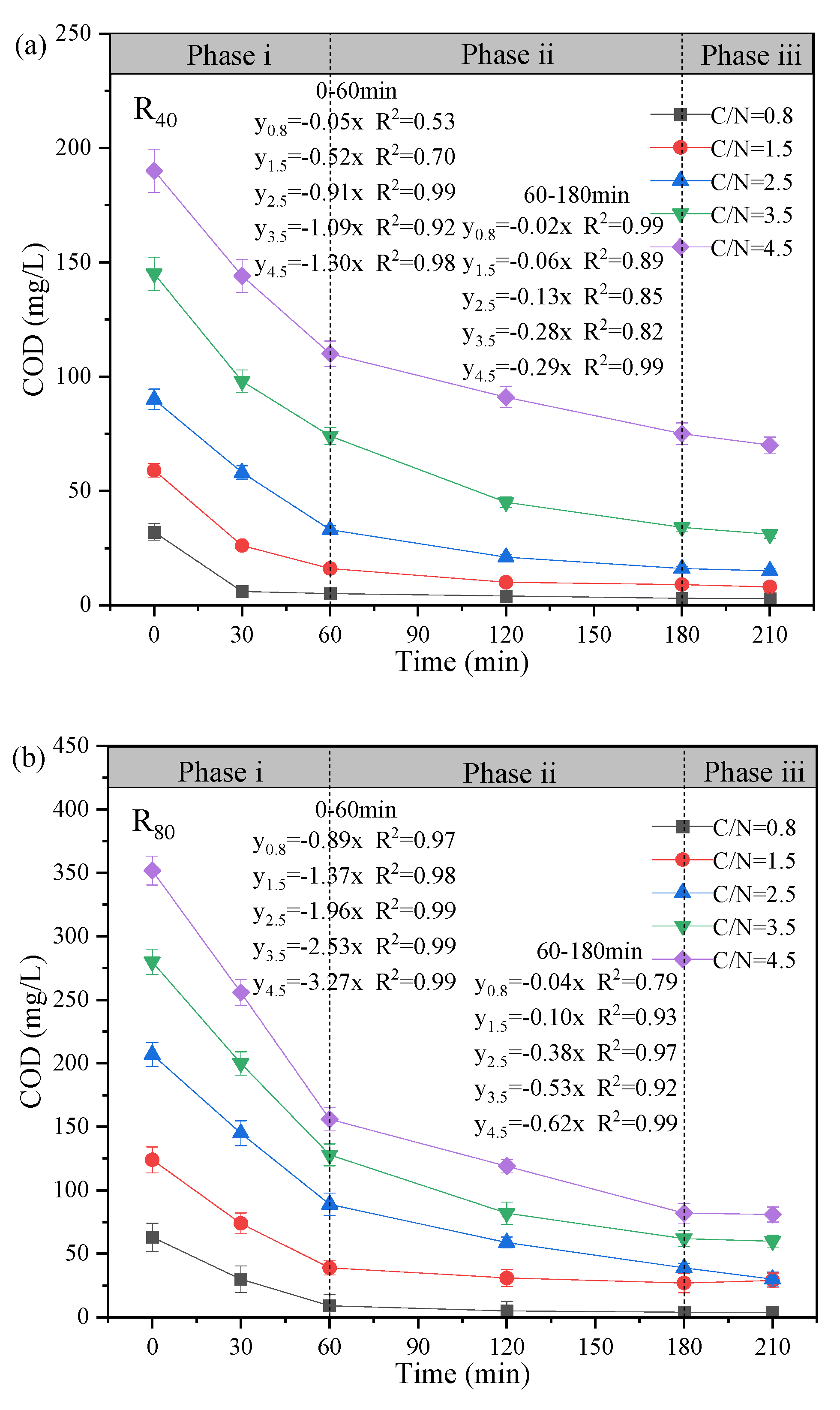

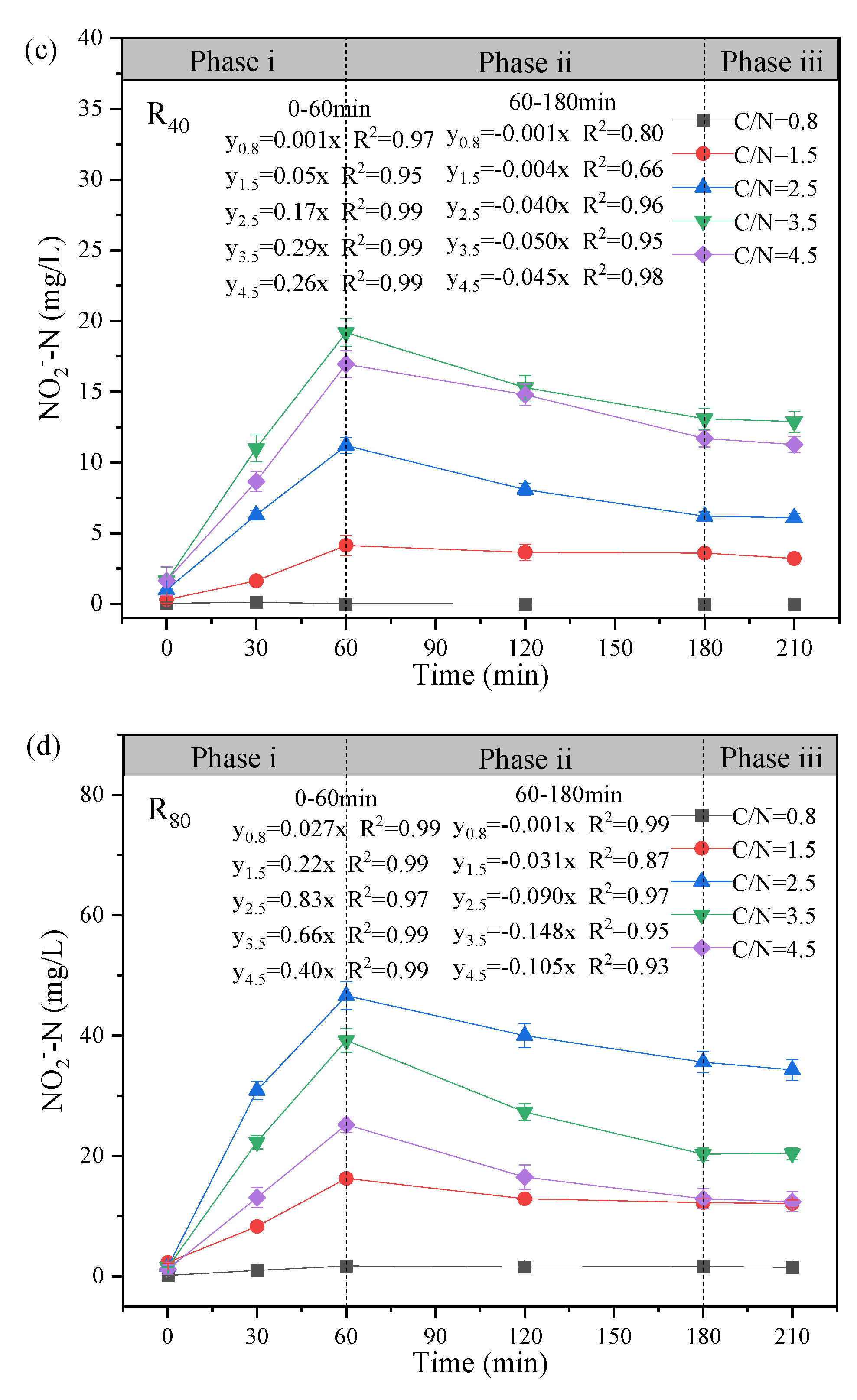

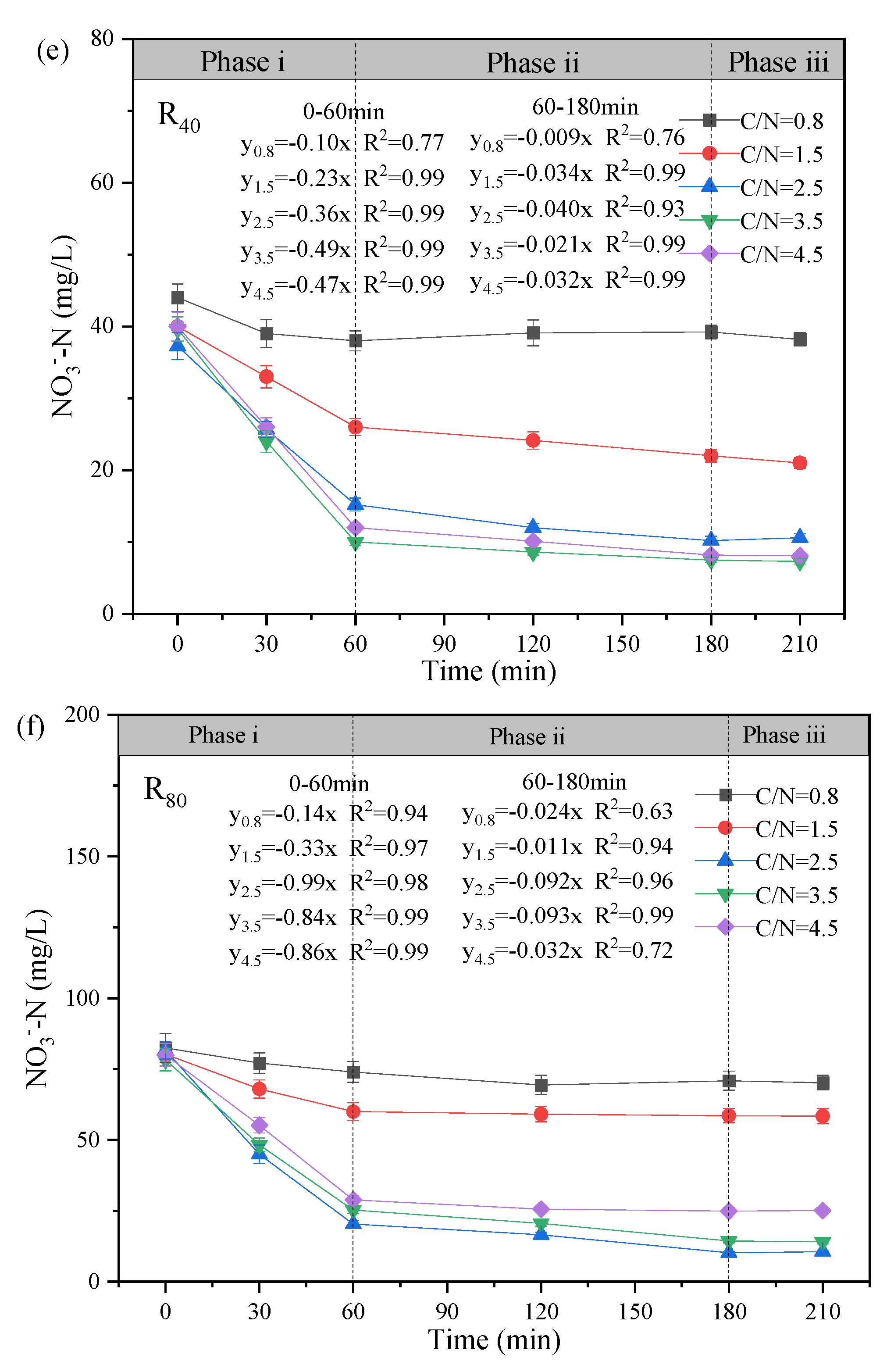

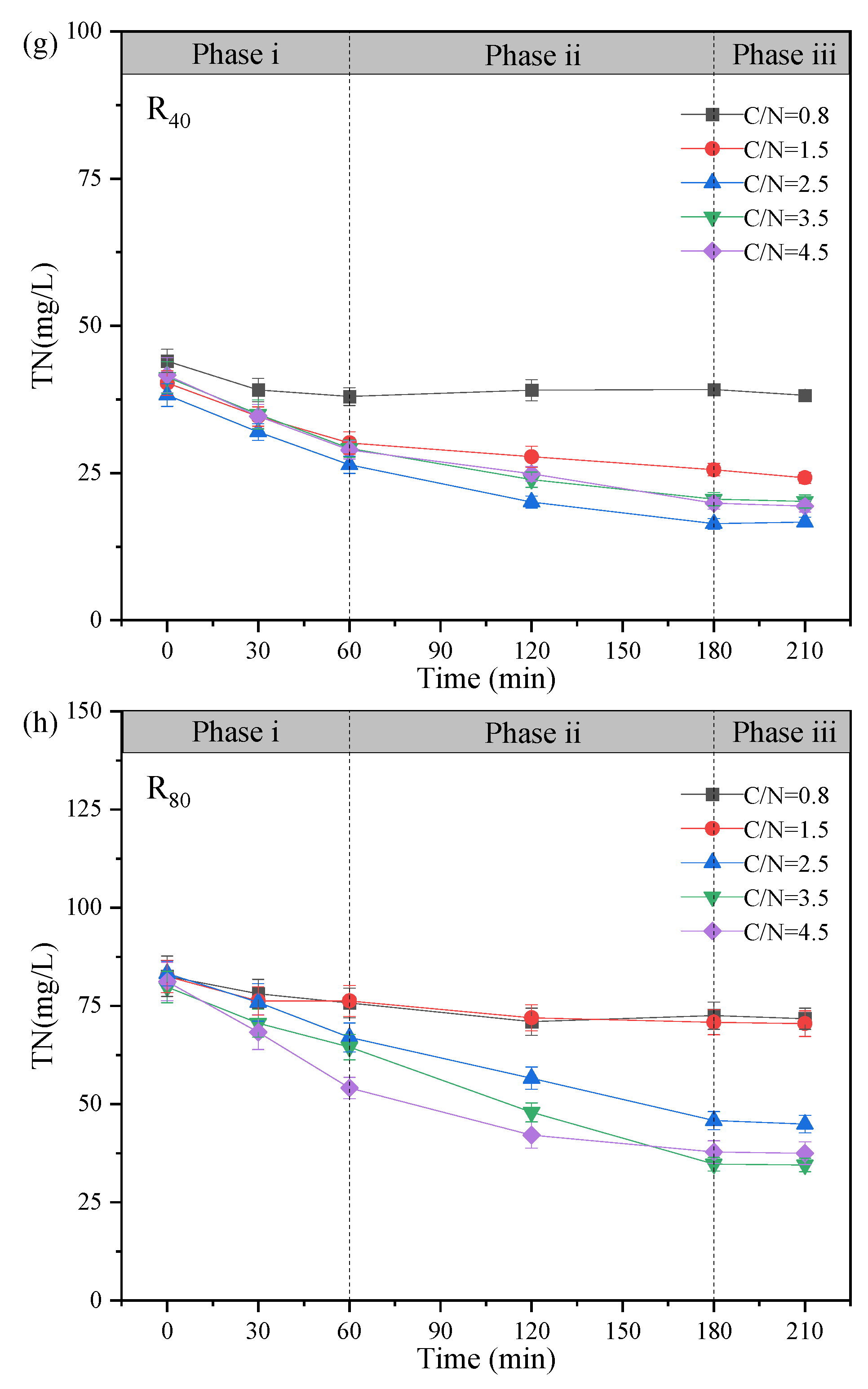

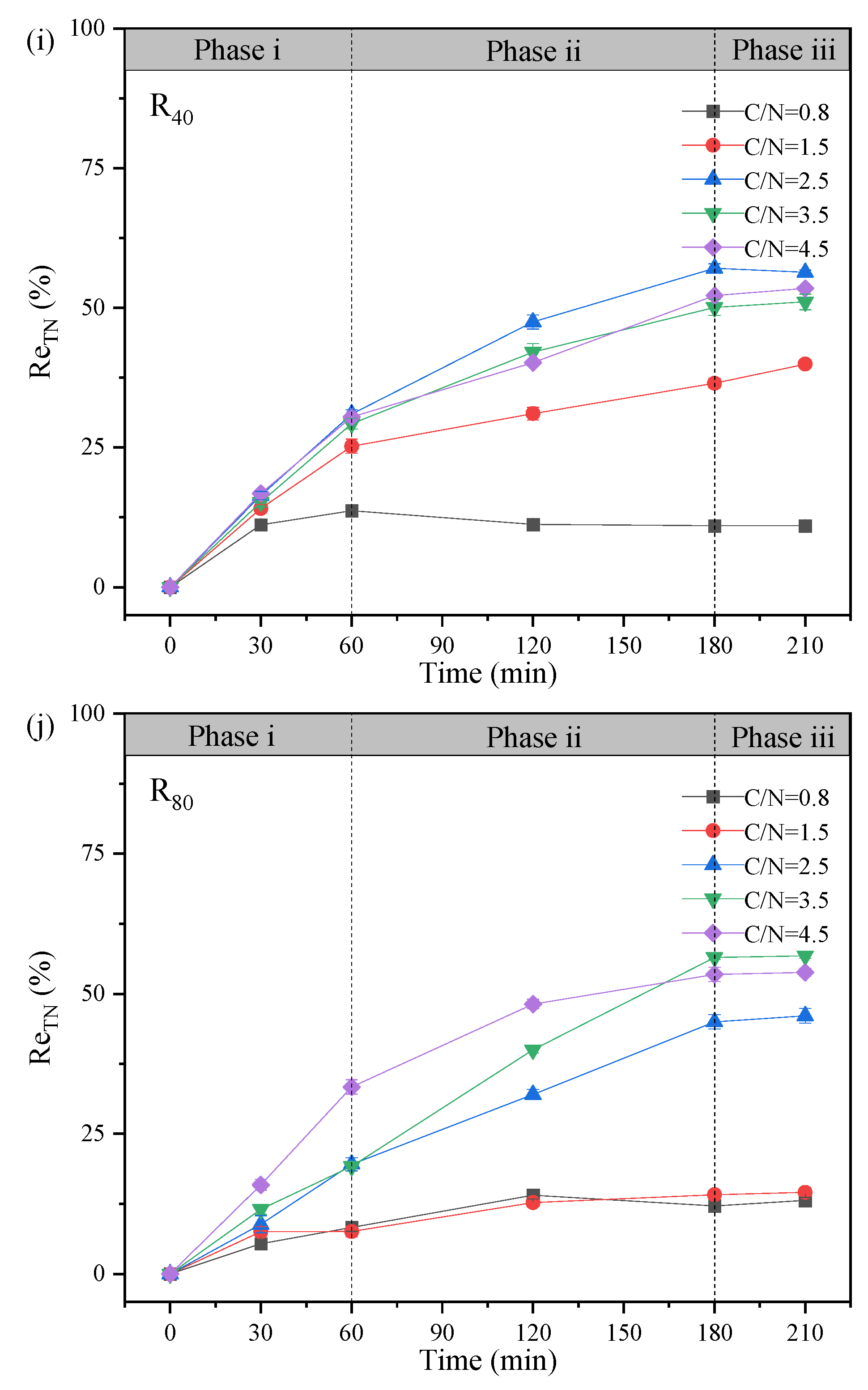

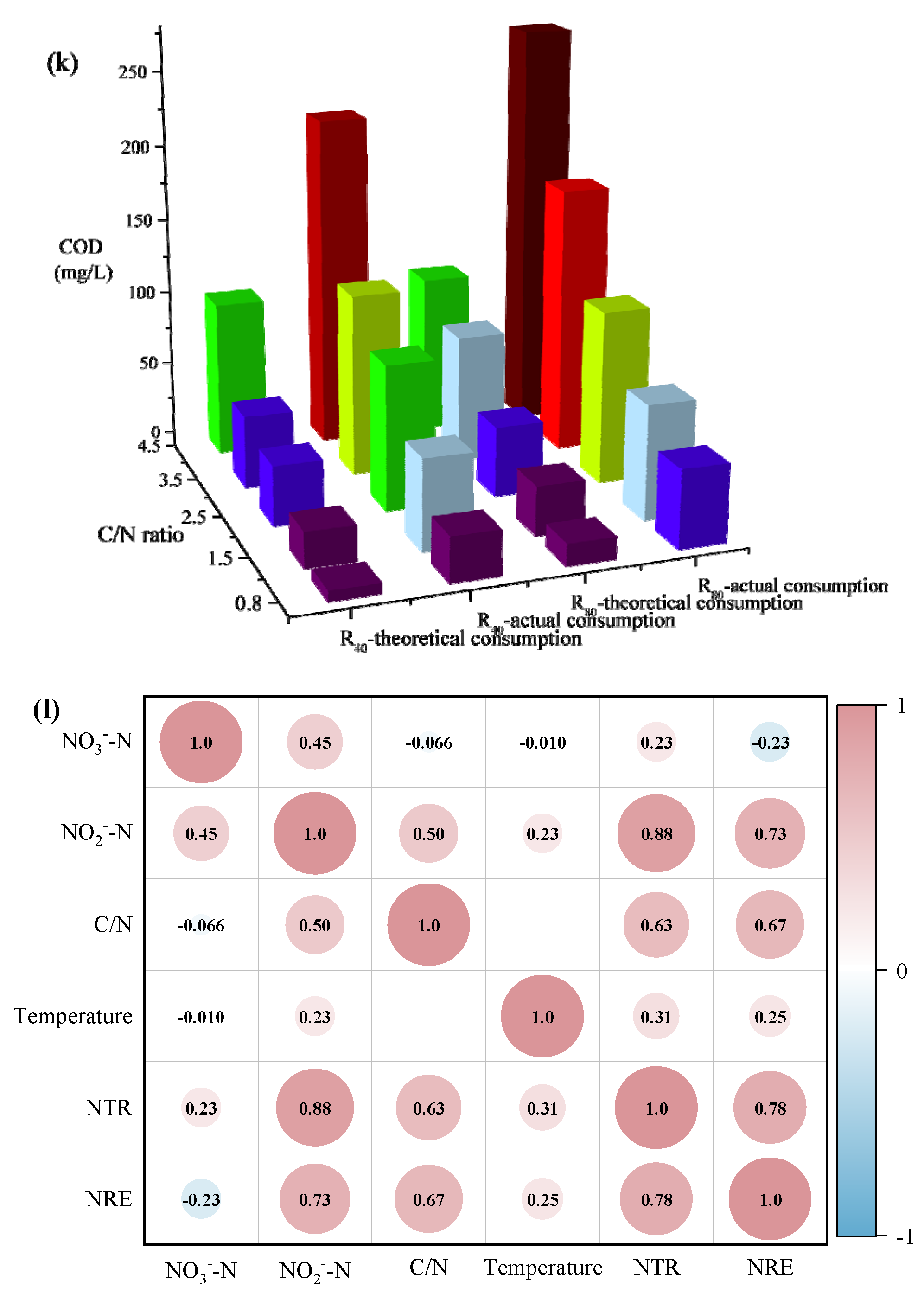

3.2. Substrate Variation and Nitrite Accumulation in the Typical Cycle

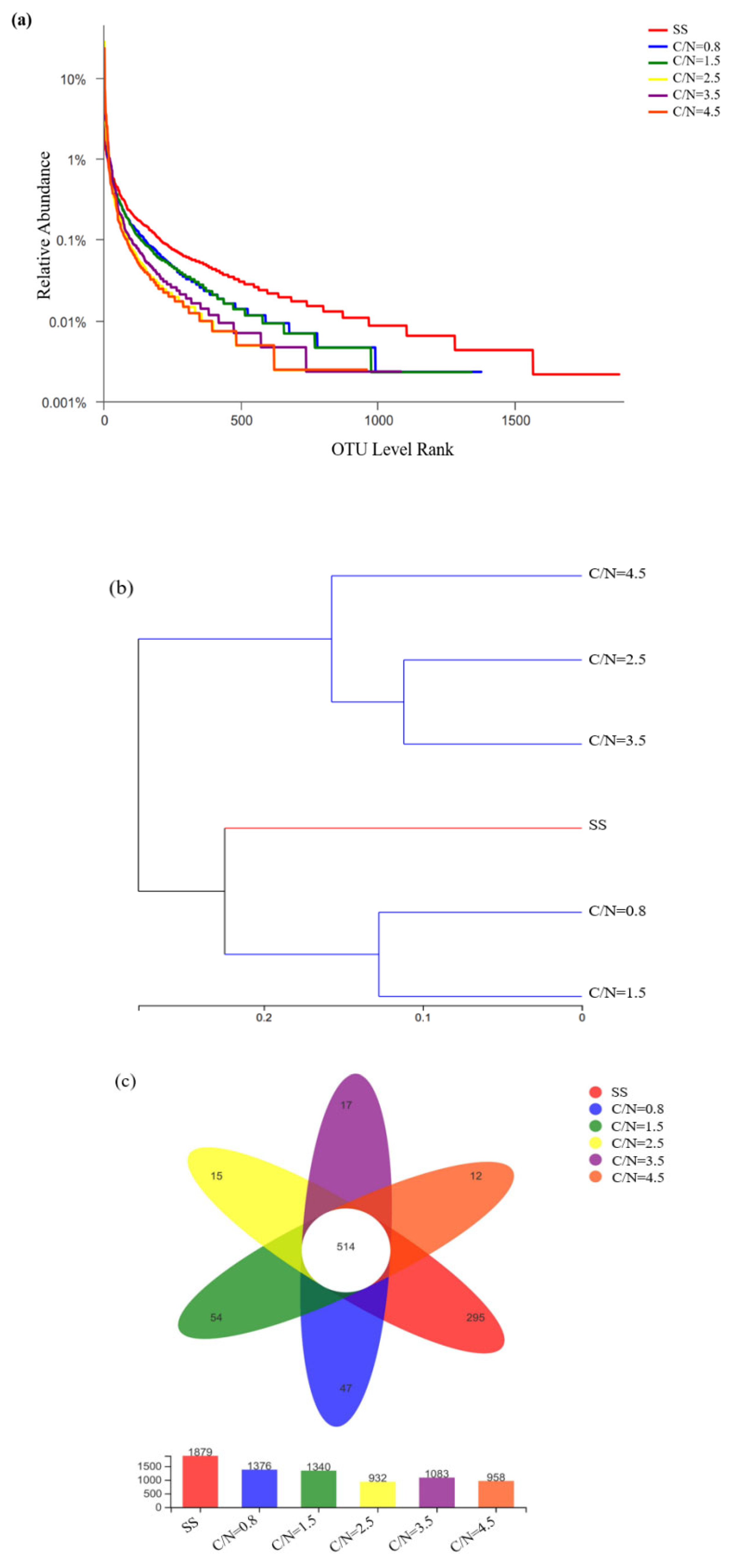

3.3. Species Diversity

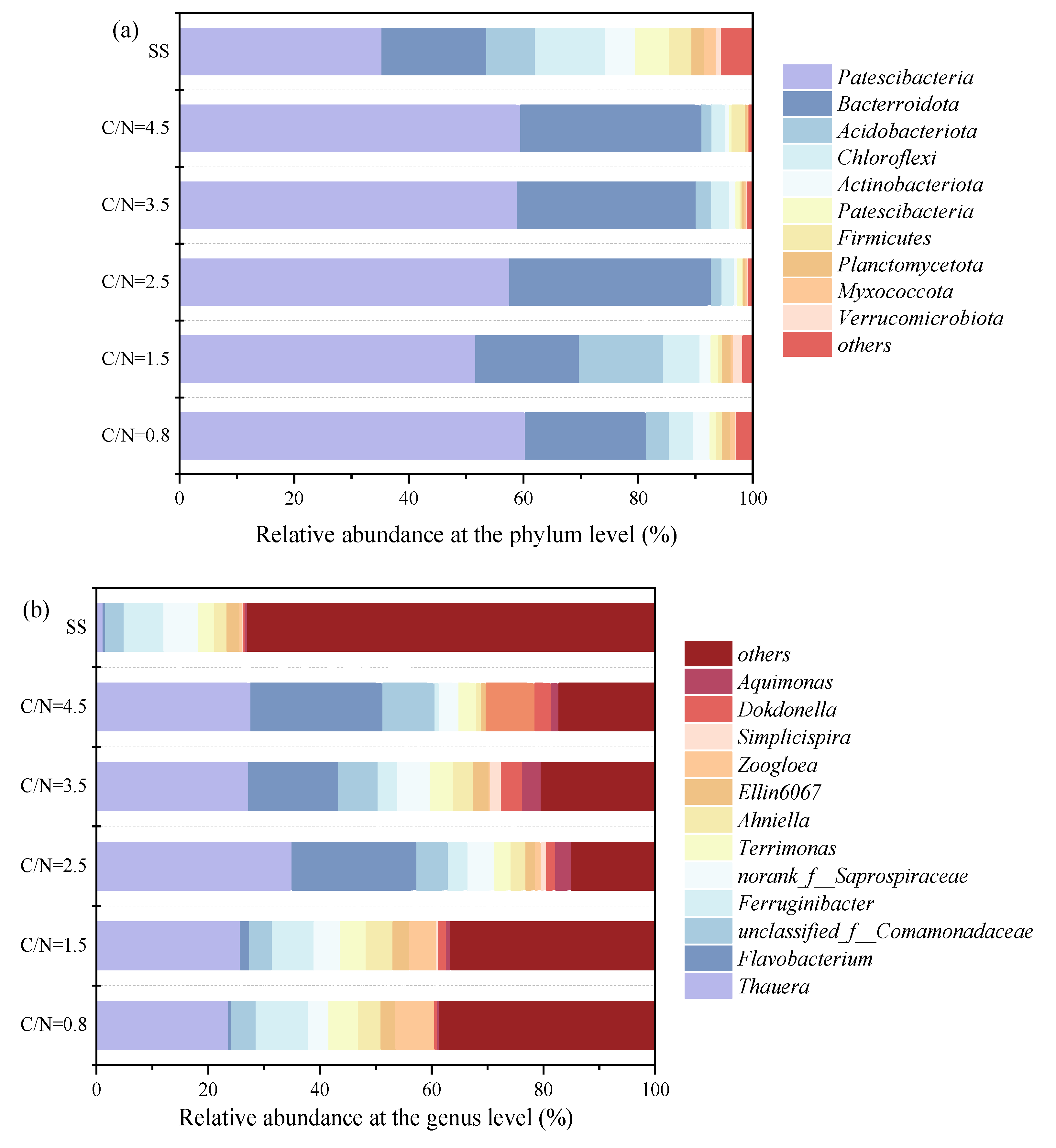

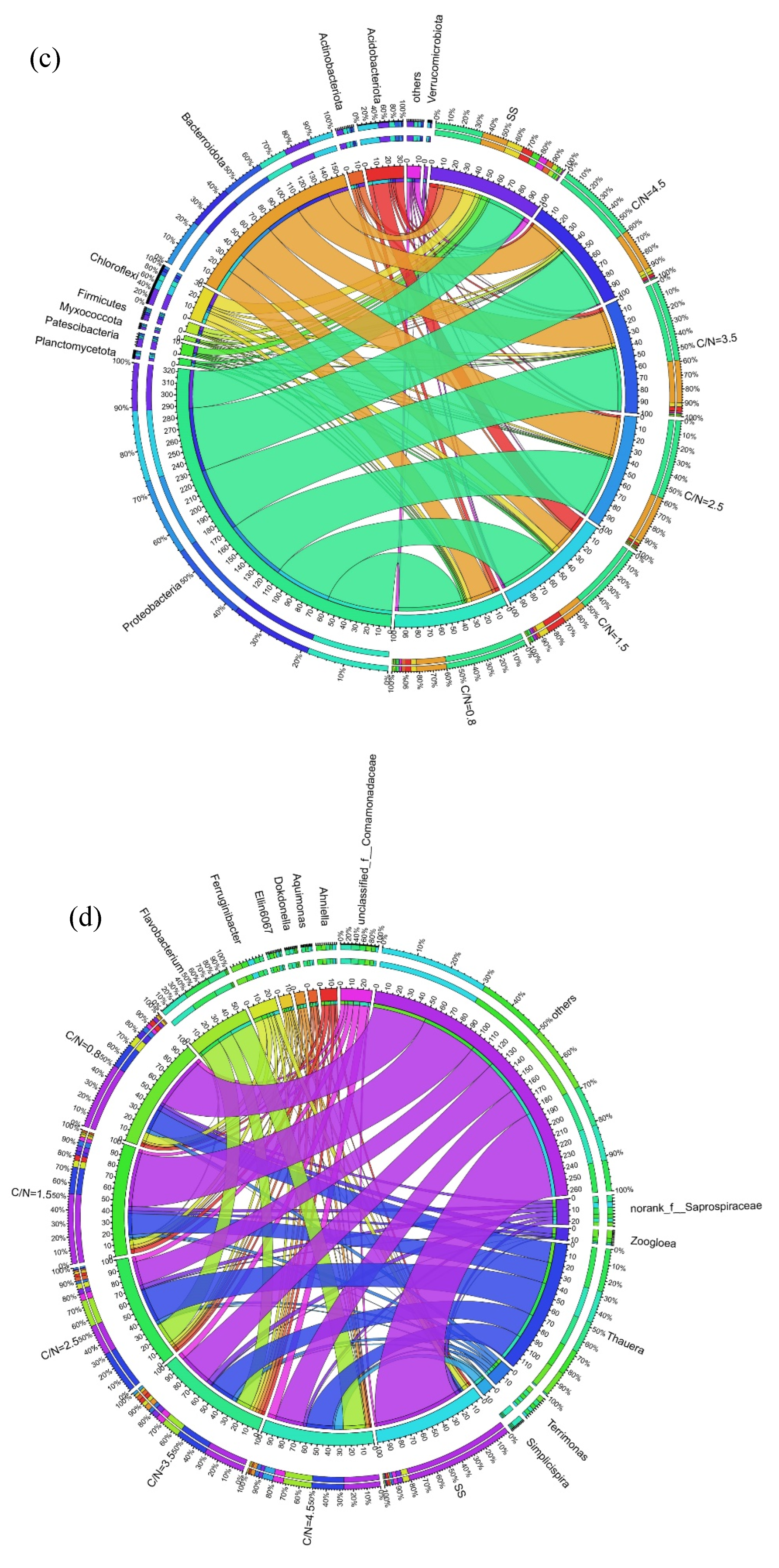

3.4. Dominant Microbial Community

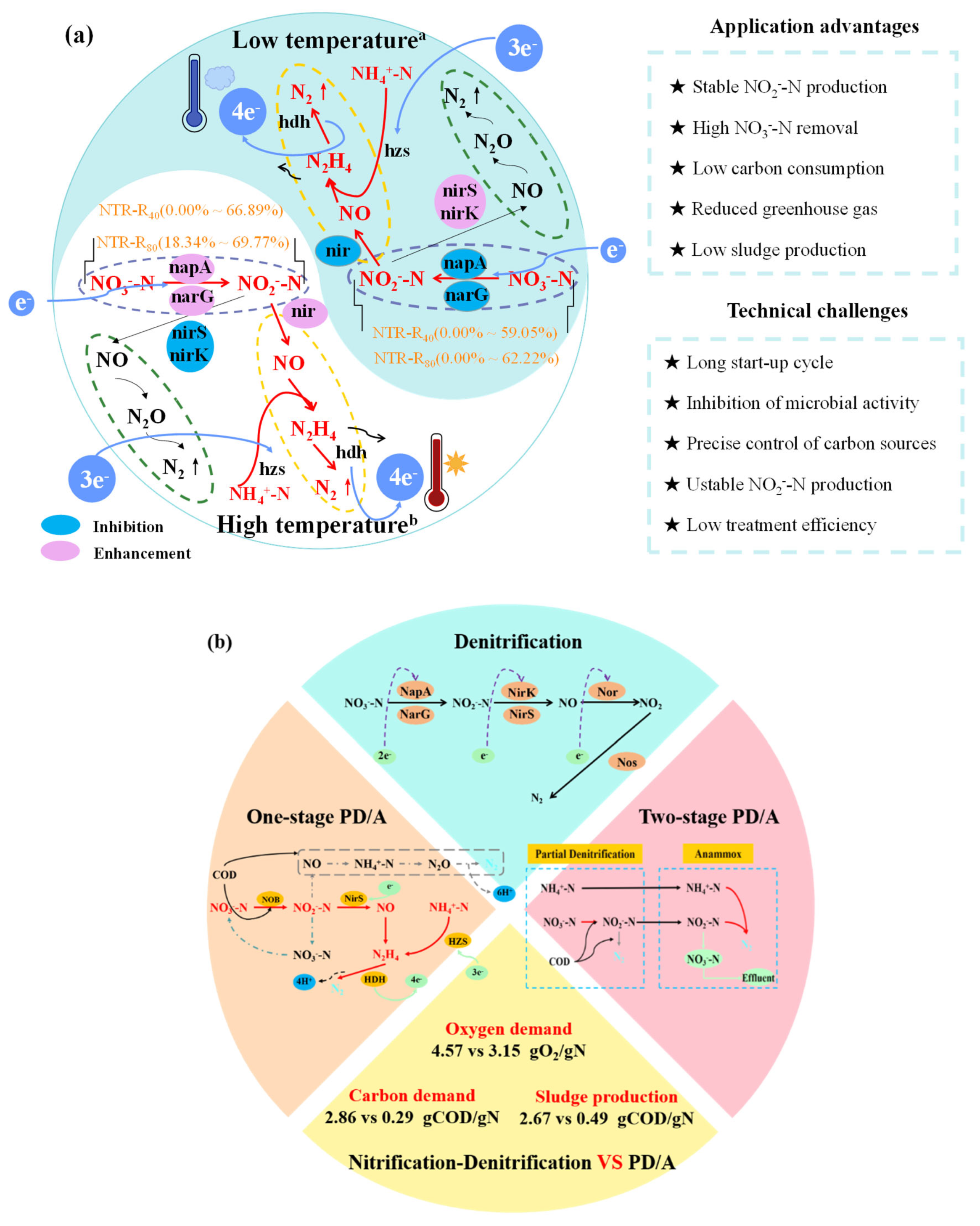

3.5. Application Feasibility of PD Related Processes

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- AWWA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Water Works Association, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Li, B.; Du, R.; Ren, N.; Peng, Y. Nitrite production in a partial denitrifying upflow sludge bed (USB) reactor equipped with gas automatic circulation (GAC). Water Research 2016, 90, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Peng, Y.; Du, R.; Zhang, H. Characterization of partial-denitrification (PD) granular sludge producing nitrite: Effect of loading rates and particle size. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 671, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, L.; Sun, S.; Li, J.; Jia, T.; Peng, Y. In situ enrichment of anammox bacteria in anoxic biofilms are possible due to the stable and long-term accumulation of nitrite during denitrification. Bioresource Technology 2020, 300, 122668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Capua, F.; Iannacone, F.; Sabba, F.; Esposito, G. Simultaneous nitrification-denitrification in biofilm systems for wastewater treatment: Key factors, potential routes, and engineered applications. Bioresource Technology 2022, 361, 127702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Cao, S.; Li, B.; Niu, M.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Performance and microbial community analysis of a novel DEAMOX based on partial-denitrification and anammox treating ammonia and nitrate wastewaters. Water Research 2017a, 108, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Cao, S.; Niu, M.; Li, B.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Performance of partial-denitrification process providing nitrite for anammox in sequencing batch reactor (SBR) and upflow sludge blanket (USB) reactor. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2017b, 122, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Du, R.; Cao, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. Combined Partial Denitrification (PD)-Anammox: A method for high nitrate wastewater treatment. Environment International 2019, 126, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Cao, S.; Wang, S.; Niu, M.; Peng, Y. Performance of partial denitrification (PD)-ANAMMOX process in simultaneously treating nitrate and low C/N domestic wastewater at low temperature. Bioresource Technology 2016a, 219, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Peng, Y.; Cao, S.; Li, B.; Wang, S.; Niu, M. Mechanisms and microbial structure of partial denitrification with high nitrite accumulation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016b, 100, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Cheng, J.; Wu, J.; He, C. Nitrogen degradation performance and microbial dynamic analysis for the efficient combination of partial denitrification and anammox (PD/A) process. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 112002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Hou, R.; Yang, P.; Qian, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Yuan, R.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B. Application of external carbon source in heterotrophic denitrification of domestic sewage: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 817, 153061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, W.; Kao, C. Mainstream partial denitrification-anammox (PD/A) for municipal sewage treatment from moderate to low temperature: Reactor performance and bacterial structure. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, S.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Y. Nitrite accumulation under constant temperature in anoxic denitrification process: The effects of carbon sources and COD/NO3-N. Bioresource Technology 2012, 114, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Huo, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Ma, B.; Zhu, R.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Performance of heterotrophic partial denitrification under feast-famine condition of electron donor: A case study using acetate as external carbon source. Bioresource Technology 2013, 133, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; Zeng, W.; Hao, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y. DNA stable isotope probing and metagenomics reveal temperature responses of sulfur-driven autotrophic partial denitrification coupled with anammox (SPDA) system. Water Research 2025, 280, 123494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.L.; Song, Q.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.Y. Simultaneous nitrification, denitrification and phosphorus removal in an aerobic granular sequencing batch reactor with mixed carbon sources: reactor performance, extracellular polymeric substances and microbial successions. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 331, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, N.L.; Bhandari, A.; Soupir, M.L.; Moorman, T.B. Woodchip Denitrification Bioreactors: Impact of Temperature and Hydraulic Retention Time on Nitrate Removal. Journal of Environmental Quality 2016, 45, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Qian, F.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Fu, J.; Wang, J. Rapid start-up and operational characteristics of partial denitrification coupled with anammox driven by innovative strategies. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 927, 172442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, G.; Hu, F.; Yang, H.; Bai, Z.; Jin, B.; Yang, X. Responses of endogenous partial denitrification process to acetate and propionate as carbon sources: Nitrite accumulation performance, microbial community dynamic changes, and metagenomic insights. Water Research 2025, 268, 122680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrba, P.; Inui, M.; Yukawa, H. Bacterial phosphotransferase system (PTS) in carbohydrate uptake and control of carbon metabolism. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2001, 92, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Králová, S. Role of fatty acids in cold adaptation of Antarctic psychrophilic Flavobacterium spp. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2017, 40, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Peng, B.; Su, C.; Massoudieh, A.; Torrents, A.; Al-Omari, A.; Murthy, S.; Wett, B.; Chandran, K.; DeBarbadillo, C. Impact of carbon source and COD/N on the concurrent operation of partial denitrification and anammox. Water Environment Research 2019, 91, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Gao, R.; Kao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, X.; Peng, Y. Improved nitrogen removal performance by enhanced denitratation/anammox as decreasing temperature for municipal wastewater treatment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2023, 190, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Kao, C.; Hou, X.; Peng, Y. Recent advances of partial anammox by controlling nitrite supply in mainstream wastewater treatment through step-feed mode. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zheng, P.; Guo, J.; Ji, J.Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.H.; Zhan, E.C.; Abbas, G. Characteristics of self-alkalization in high-rate denitrifying automatic circulation (DAC) reactor fed with methanol and sodium acetate. Bioresource Technology 2014, 154, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wan, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H. Pilot-scale application of sulfur-limestone autotrophic denitrification biofilter for municipal tailwater treatment: Performance and microbial community structure. Bioresource Technology 2020, 300, 122682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, R.; Miao, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Li, A.; Shen, H. Temperature dependence of denitrification microbial communities and functional genes in an expanded granular sludge bed reactor treating nitrate-rich wastewater. Rsc Advances 2018, 8, 42087–42094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sui, J.; Wang, C.; Li, J. Excellent anammox performance driven by stable partial denitrification when encountering seasonal decreasing temperature. Bioresource Technology 2022, 364, 128041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Oehmen, A.; Zhao, J.; Duan, H.; Yuan, Z.; Ye, L. Insights on biological phosphorus removal with partial nitrification in single sludge system via sidestream free ammonia and free nitrous acid dosing. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 895, 165174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, B.; Chenghua, L.; Luke, P.; Jeffrey, S.; Michael, B.; Kartik, C. Optimization of partial denitrification to maximize nitrite production using glycerol as an external carbon source – impact of influent COD:N ratio. Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation 2017, 2017, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, T.V.K.; Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Venugopalan, V.P.; Sai, P.M.S. Effect of C/N ratio on denitrification of high-strength nitrate wastewater in anoxic granular sludge sequencing batch reactors. Ecological Engineering 2016, 91, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Venugopalan, V.P. Denitrification of synthetic concentrated nitrate wastes by aerobic granular sludge under anoxic conditions. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Takekawa, M.; Soda, S.; Ike, M.; Furukawa, K. Temperature dependence of nitrogen removal activity by anammox bacteria enriched at low temperatures. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2017, 123, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Lou, T.; Jiang, K.; Niu, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, A. Characteristics of nutrients removal under partial denitrification initiated by different initial nitrate concentration. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 2021, 44, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Exploring and comparing the impacts of low temperature to endogenous and exogenous partial denitrification: The nitrite supply, transcription mechanism, and microbial dynamics. Bioresource Technology 2023, 370, 128568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Ma, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y. Long-term effect of pH on denitrification: High pH benefits achieving partial-denitrification. Bioresource Technology 2019, 278, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Ji, F.; Wei, J.; Fang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Cai, A.; Kuang, L. The influence mechanism of temperature on solid phase denitrification based on denitrification performance, carbon balance, and microbial analysis. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 732, 139333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strous, M.; Pelletier, E.; Mangenot, S.; Rattei, T.; Lehner, A.; Taylor, M.W.; Horn, M.; Daims, H.; Bartol-Mavel, D.; Wincker, P.; Barbe, V.; Fonknechten, N.; Vallenet, D.; Segurens, B.; Schenowitz-Truong, C.; Médigue, C.; Collingro, A.; Snel, B.; Dutilh, B.E.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; van der Drift, C.; Cirpus, I.; van de Pas-Schoonen, K.T.; Harhangi, H.R.; van Niftrik, L.; Schmid, M.; Keltjens, J.; van de Vossenberg, J.; Kartal, B.; Meier, H.; Frishman, D.; Huynen, M.A.; Mewes, H.W.; Weissenbach, J.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Wagner, M.; Le Paslier, D. Deciphering the evolution and metabolism of an anammox bacterium from a community genome. Nature 2006, 440, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S. Nitrite Accumulation during the Denitrification Process in SBR for the Treatment of Pre-treated Landfill Leachate. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2009, 17, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, P.Y.; Paula, C.T.; Borges, A.d.V.; Shibata, A.E.; Grangeiro, L.C.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z. A critical review of the mainstream anammox-based processes in warm climate regions: Potential, performance, and control strategies. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 113691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, I.S.; Medhi, K. Nitrification and denitrification processes for mitigation of nitrous oxide from waste water treatment plants for biovalorization: Challenges and opportunities. Bioresource Technology 2019, 282, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yan, Y.; Song, C.; Pan, M.; Wang, Y. The microbial community structure change of an anaerobic ammonia oxidation reactor in response to decreasing temperatures. Environmental science and pollution research international 2018, 25, 35330–35341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, H. Nitrogen removal performance of anammox immobilized fillers in response to seasonal temperature variations and different operating modes: Substrate utilization and microbial community analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 829, 154574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Bai, X.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Xu, Y.; Xiong, H.; Xie, X.; Tian, X.; Li, J. Two-stage partial nitrification-denitrification and anammox process for nitrogen removal in vacuum collected toilet wastewater at ambient temperature. Environmental Research 2024, 262, 119917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S.; Dai, X.H.; Chai, X.L. Effect of different carbon sources on denitrification performance, microbial community structure and denitrification genes. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 634, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Ni, J.; Ma, T.; Li, C. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification at low temperature by a newly isolated bacterium, Acinetobacter sp. HA2. Bioresource Technology 2013, 139, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Deng, H.-p; Sheng, X.-m; Pan, Y.; Li, X. Effect of C/N Ratio on Nitrite Accumulation During Denitrification Process. Huanjing Kexue 2013, 34, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Hao, S.; Wang, Y.; Lan, S.; Dou, Q.; Peng, Y. Rapid start-up strategy of partial denitrification and microbially driven mechanism of nitrite accumulation mediated by dissolved organic matter. Bioresource Technology 2021a, 340, 125663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhou, J.Z.; Ju, F. Active predation, phylogenetic diversity, and global prevalence of myxobacteria in wastewater treatment plants. Isme Journal 2023a, 17, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, J.; Liu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, C.; Liu, Y.; He, C.; Wu, J. Nitrite accumulation and microbial behavior by seeding denitrifying phosphorus removal sludge for partial denitrification (PD): The effect of COD/NO3− ratio. Bioresource Technology 2021b, 323, 124524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; You, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, X. Nitrite production mechanism and microbial evolution characteristic influenced by pH during partial denitrification (PD) process. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023b, 11, 111451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Fan, Y.; Gu, X.; Wu, J. Response of nitrite accumulation, sludge characteristic and microbial transition to carbon source during the partial denitrification (PD) process. Science of The Total Environment 2023c, 894, 165043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, M.; Fan, Y.; Ji, J.; Wu, J. Combined effects of carbon source and C/N ratio on the partial denitrification performance: Nitrite accumulation, denitrification kinetic and microbial transition. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 113343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tan, Y.; Fan, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Ge, L.; Wu, J. Nitrite accumulation, denitrification kinetic and microbial evolution in the partial denitrification process: The combined effects of carbon source and nitrate concentration. Bioresource Technology 2022, 361, 127604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tan, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, L. Insights into nitrite accumulation and microbial structure in partial denitrification (PD) process by the combining regulation of C/N ratio and nitrate concentration. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023d, 11, 109891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; He, C.; Wu, J. Bioaugmentation of low C/N ratio wastewater: Effect of acetate and propionate on nutrient removal, substrate transformation, and microbial community behavior. Bioresource Technology 2020, 306, 122465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Luo, M.; Dong, H.; Fang, L.; Wang, W.; Feng, L.; Yu, Q. Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures. Green Processing and Synthesis 2021, 10, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Systems | C/N | Influent NO3--N (mg/L) |

Influent COD (mg/L) |

NTRA (%) |

NREA (%) |

Other parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R40 | 0.8 | 40±1 | 32±8 | 0.50 | 8.63 | Operation cycle: 270 min Cycle: 120 VSS: 2500±100 mg/L SRT: 25 d Temperature: 10 - 5 ℃ |

| 1.5 | 40±2 | 60±7 | 27.79 | 31.10 | ||

| 2.5 | 40±1 | 100±5 | 31.54 | 40.15 | ||

| 3.5 | 40±1 | 140±9 | 52.87 | 54.96 | ||

| 4.5 | 40±2 | 180±8 | 48.87 | 45.67 | ||

| R80 | 0.8 | 80±1 | 64±6 | 19.15 | 9.16 | |

| 1.5 | 80±2 | 120±7 | 46.00 | 24.68 | ||

| 2.5 | 80±1 | 200±6 | 57.12 | 51.19 | ||

| 3.5 | 80±1 | 280±8 | 60.42 | 55.75 | ||

| 4.5 | 80±2 | 360±9 | 56.98 | 40.55 |

| Samples | Sequence | OTUs | ACE | Chao | Shannon | Simpson | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | 50347 | 1879 | 2084 | 2052 | 6.09 | 0.006 | 0.993 |

| C/N=0.8 | 60472 | 1376 | 1752 | 1727 | 4.88 | 0.040 | 0.991 |

| C/N=1.5 | 49551 | 1340 | 1693 | 1666 | 4.87 | 0.038 | 0.992 |

| C/N=2.5 | 46142 | 932 | 1296 | 1276 | 3.81 | 0.095 | 0.992 |

| C/N=3.5 | 50825 | 1083 | 1469 | 1445 | 4.29 | 0.057 | 0.992 |

| C/N=4.5 | 44032 | 958 | 1564 | 1370 | 3.84 | 0.076 | 0.992 |

| Reactors | Working volume (L) | Carbon source | C/N ratio | Influent NO3--N (mg/L) |

Temperature (℃) |

NTR (%) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBR | 10 | Acetate | 2.5 | 41.6 | 22±2 | 71.7 | (Gong et al., 2013a) |

| SBR | 5 | Acetate | 2.5 | 30 - 400 | 23.6 - 28.8 | 83.3 | (Du et al., 2017b) |

| SBR | 5 | Acetate | 3.0 | 25 | 16 - 28 | ~80 | (Du et al., 2016c) |

| SBR | 5 | Acetate | 3.0 | 50 | 10.6 - 18.3 | 57.5 | (Du et al., 2016b) |

| SBR | 12 | Glycerol | 2.5 - 2.8 | 100 | 20 - 23 | 72.5, C/N=2.6 | (Matthew et al., 2017) |

| SBR | 10 | Acetate | 2.5 - 4.5 | 80 | 3 - 12 | 76.79, C/N=2.5 75.57, C/N=3.5 68.15, C/N=4.5 |

This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).